Abstract

This study evaluated factors affecting the completion of blended-eLearning courses for health workers and their effect on stigma. The two courses covered the screening and management of harmful alcohol, tobacco, and other substance consumption in a lower-middle-income country setting. The courses included reading, self-reflection exercises, and skills practice on communication and stigma. The Anti-Stigma Intervention-Stigma Evaluation Survey was modified to measure stigma related to alcohol, tobacco, or other substances. Changes in stigma score pre- and post-training period were assessed using paired t-tests. Of the 123 health workers who registered, 99 completed the pre- and post-training surveys, including 56 who completed the course and 43 who did not. Stigma levels decreased significantly after the training period, especially for those who completed the courses. These findings indicate that blended-eLearning courses can contribute to stigma reduction and are an effective way to deliver continuing education, including in a lower-middle-income country setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Substance use disorders (SUDs), including alcohol (AUD), tobacco (TUD), and other substance use disorders (OSUD), are often stigmatized, and people affected by them are disproportionately marginalized in society (Bielenberg et al., 2021; Keyes et al., 2010; Kilian et al., 2021; Ritson, 1999; Room, 2005). Health workers, decision-makers, and members of the public often view these conditions as self-inflicted and undeserving of their attention or time (Lindberg et al., 2006; Ritson, 1999; Room, 2005; van Boekel et al., 2013). Treatment for AUD ranks low among public priorities (Lipozencić, 2006), with a prevalent opinion that funding for treatments of AUD should be redirected toward more “worthy” causes (Kilian et al., 2021; Schomerus et al., 2011). As such, related stigma decreases the priority given to addressing SUDs and contributes to the lack of implementation of effective interventions compared to other conditions with similar disease burdens (Desjarlais, 1995). Furthermore, individuals affected by stigma from the public, s, and those in a position of power, combined with their internalized self-stigma, are less willing and less able to seek treatment (Bayer, 2008), resulting in unnecessary suffering and higher disease burden (Room, 2005). This is of concern considering that the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other substances use rank as second, ninth, and 14th highest causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide, with increases in age-standardized DALY rate of 24.3% for tobacco and 37.1% for alcohol from 1990 and 2019 (Murray et al., 2020). The burden is also very significant in Sub-Saharan Africa (Lim et al., 2012; World Health Organization, 2010). This means that even in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), tobacco, alcohol, and other substance use contribute significantly to the disease burden. This situation calls for more research to understand and address stigma, specifically the stigma associated with the consumption of each type of substance, and stigma in LMICs, the object of much less research.

Levels of stigma towards those using psychoactive substances is frequently worst than towards those with other conditions, even more than toward those with various other mental illnesses. For example, the desire for “social distance” from persons with AUD is often higher than those with mental illnesses such as depression or schizophrenia (Kilian et al., 2021; Schomerus et al., 2011). Stigma toward those using illicit drugs is also frequently more substantial (Ahern et al., 2007; Cunningham et al., 1994; Kilian et al., 2021; Room, 2005). Crisp et al. (2000) found that individuals with drug dependence were ranked the highest for “danger to others, unpredictable, hard to talk to, and having themselves to blame,” while it was less so for those with alcohol dependence. However, several studies found similar levels of stigma toward those with various illicit substances’ dependencies and those with alcohol dependency and less stigma toward those with tobacco dependency (Cunningham et al., 1994; Kilian et al., 2021).

Even if tobacco users suffer from less stigma, it remains relevant. Tobacco use is increasing in many LMICs to the extent that by 2030, 80% of the deaths worldwide caused by tobacco are expected to occur in LMICs (Nichter et al., 2010). Meanwhile, tobacco use in high-income countries (HIC) has decreased dramatically in the last century; concomitant with an increasingly negative public perception of smokers since the 1940s (Chapman and Freeman, 2008; Graham, 2012), a phenomenon deemed in part to be “policy-induced stigma” (Bayer, 2008), as policies promoting non-smoking can contribute to hostility toward smokers (Chapman and Freeman, 2008). Concerns have been raised that this might have negative consequences socially but that tobacco control policies can legitimately involve generating a degree of stigma if they achieve their objective of protecting people’s health in total (Bayer & Stuber, 2006; Burgess et al., 2009). This raises the question of the potential impact of similar tobacco policies in LMICs and if something can be done so that people suffering from TUD would be seen as worthy of receiving effective treatment.

There is increasing interest and action to reduce health-related stigma. However, greater efforts are geared toward mental illnesses other than SUD (Livingston et al., 2012). The literature describes three main strategies to decrease stigma: education, contact, and protest (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Schomerus et al., 2011). Protest attempts to correct inaccurate and hostile representations of mental illness as a way to challenge associated stigma (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). Education strategy consists of the provision of information to enhance the understanding of mental illnesses (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). It can reduce stigma in general (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Patel, 2007). SUD-related social stigma, or the attitude of the general population, seems most effectively changed through communication strategies, including positive stories and motivational interviewing. Furthermore, the effects of educational approaches can be enhanced by contact-based methods (Livingston et al., 2012), such as providing contact with people suffering from mental illnesses, which appears to be successful in reducing stigma, including among health workers (Kassam et al., 2012; Patten et al., 2012; Penn & Couture, 2002).

Since health workers represent a part of formal structures of society, stigma from health workers is frequently categorized as structural stigma. Effective strategies to decrease structural stigma include the use of reflective techniques, structured education combined with clinical experience, and acceptance and commitment techniques (Livingston et al., 2012). However, overall, a systematic review of interventions to impact stigma toward those with SUD indicates that few of these interventions have been proven effective, and even fewer have been scaled up (Livingston et al., 2012). This points toward the need to further develop and evaluate new and easily scalable strategies to decrease stigma toward those with SUD.

A few studies have shown that eLearning or blended-eLearning (a combination of eLearning with in-person components) can effectively reduce stigma toward mental illnesses or the use of a variety of substances (Finkelstein & Lapshin, 2007; Griffiths et al., 2004; Kilian et al., 2021). Therefore, providing eLearning on SUD could be an innovative and likely scalable solution to decrease SUD stigma. eLearning is defined as “learning that is supported by information and communication technologies (ICT)” (Bari et al., 2018) p. 98, which can avail the trainee of the most current information in a self-directed and self-paced manner (Ai & Laffey, 2007). eLearning can occur anywhere where the necessary tools are available, minimizing expensive travel or time away from work or other obligations, that are amplified by traditional in-person teaching methods. eLearning is deemed an important strategy for training health workers, especially considering the increasing availability of information technology (internet, computer, smartphones) even in LMICs (Bahia & Suardi, 2019; Dagys et al., 2015; Kebaetse et al., 2014; Marrinan et al., 2015; Sissine et al., 2014; The World Bank, 2020; Ballew et al., 2013). eLearning could be particularly attractive to LMICs, which have very limited human resources to deliver health services and an enormous need for training to address various prevalent health conditions not previously treated in the majority of their population.

The Africa Mental Health Research and Training Foundation (AMHRTF) and NextGenU.org conceptualized a blended-eLearning capacity-building initiative to train health workers to screen and manage risky levels of substance use in primary care. An associated comprehensive mixed-methods research program evaluated the impact of the training on health workers and patients’ outcomes: the computer-based drug and alcohol Training and Assessment in Kenya (eDATA-K), under which this study is nested. Other eDATA-K studies are published elsewhere (Clair et al., 2022a; Clair et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2019, 2022b; Hsiang-Te Tsuei et al., 2017).

This study tests the impact of the blended-eLearning clinical courses on health workers’ stigma toward various SUD. This study also examines the impact on stigma of an additional contact component for a subset of health workers who participated in the e-DATA-K randomized control trials (RCTs). Participating in the RCTs generated an intense period of direct interactions between health workers and people at moderate to high risk from alcohol use.

Methodology

Design and Setting

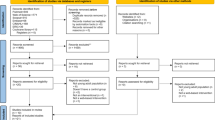

This observational study assesses changes in stigma levels in course completers and non-completers among health workers in facilities where substance use courses were offered. Stigma levels were measured immediately pre- and post-training. Stigma was also measured post-participation in randomized controlled trials for course completers who engaged in the RCTs. The Kenya Medical Research Institute Ethics Review Committee and the University of British Columbia Ethics Review Board granted scientific and ethical approval for the study. From July 2014 to December 2015, the study was carried out in 11 public healthcare facilities in two rural counties of Kenya, and 3 private ones in the greater Nairobi area. These sites were selected for eDATA-K because of willingness to participate in the program of research, offering typical primary care services, considered likely to have stable and sufficient staffing for the duration of the study, and having access to electricity. The various district health management teams, county government health officials, and relevant facility management personnel provided administrative approval and support as needed. A computer and internet access were provided in the public facilities, while neither was provided to the private facilities, as they were deemed to have adequate computer and internet access already. One private and three public facilities were unable to participate in the RCT phase due to a lack of course completers or workload.

Participants and Procedure

The courses were offered to any interested health worker in the community clinics and the hospital outpatient departments. Health worker participants were selected if they worked in one of the eDATA-K facilities, agreed to take the relevant course in their own time without receiving financial compensation for taking the course (unlike typical training offered in LMICs), were fluent in English (the language used in the course and the surveys), and consented to participate in the study. Participants filled out the questionnaires before starting the course (T1) and within a week after course completion (T2). Course completers were defined as those who had completed all the training modules, while non-completers were defined as trainees who logged in but did not complete all modules. A subset of those, who had completed the training and participated in the RCTs, filled out the questionnaires again at the end of the RCTs (T3), approximately 6 to 9 months after training completion.

Intervention

The training followed evidence-based recommendations for online and health worker education (Ballew et al., 2013; Nyarango, 1991) to impart key competencies outlined in the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) (World Health Organization, 2010), and WHO Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and in its linked brief intervention manuals (Humeniuk and H.-E. S., Ali RL, Poznyak V, Monteiro MG., 2010). The readings included extracts from these and other high-quality online resources. Two courses were created. The Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Substance Use Screening targeted lay health workers such as receptionists, community health workers, and other support staff, and was met to take approximately 13 h. The Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Substance Use Disorders in Primary Care course was for primary care clinicians such as nurses, clinical officers, and physicians, and was met to take approximately 17 h. Both courses share the introductory module (1), the stigma and human rights related to SUD (2), and the one addressing communication with people seeking care, their caregivers and family (6). In the screening course for the lay health workers, module 3 covers screening techniques focusing on the ASSIST, module 4 covers an overview of effective intervention and other information related to SUD, and module 5 covers urgent situations and comorbidities needing clinical care by health professionals for them to seek help and refer. In the primary care course for physicians and nurses, module 3 covers interventions to address SUD, module 4 covers the specific tools related to brief intervention in more detail, focusing on the ASSIST, and module 5 covers comorbidities, complications, and how to support general well-being, as well as guidelines on monitoring and follow-up.

Each trainee was assigned a mentor (a trained psychologist, physician, or clinical officer) since previous studies showed that mentor support increased the effectiveness of training primary care workers in Kenya (Nyarango, 1991). Furthermore, peer interactions have enhanced skill acquisition in medical settings (Goldsmith et al., 2006; Waddell & Dunn, 2005). Therefore, the training included peer and mentored activities such as reflections, discussion forums, and role-plays, as per some of the best practices to address stigma through education (Livingston et al., 2012).

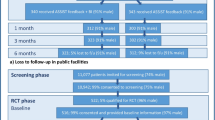

The period of intense interactions for course completers in RCT facilities included support staff screening 22,327 people, identifying 1230 with risky levels of alcohol use, and providing them with their ASSIST screening results. Of those with risky levels of alcohol use, 595 were randomized to receive a brief intervention by the primary care clinician.

Measures and Data Analysis

This study adapted the Anti-Stigma Intervention survey (ASI) (Lillie et al., 2014) to assess SUD stigma scores independently in course completers and non-completers. This survey measures three dimensions of stigma toward individuals with mental illness in three subscales: stigmatizing attitudes (Attitude), social acceptance/social distance (Social Distance), and Social Responsibility (Lillie et al., 2014). It contains 20 self-report items scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with reverse scoring of some answers for higher scores to consistently indicate greater stigma (Lillie et al., 2014). The ASI was adapted for this study by repeating each question three times, replacing “mental illness” sequentially with “alcohol use disorder,” “tobacco use disorder,” or “other substance use disorder.” Stigma toward people with substance use disorder was assessed separately for each substance. A survey collecting demographic information was included.

The data were double entered and analyzed using IBM SPSS® version 21 or higher. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests (for expected n of < 5) were performed to determine statistically significant relationships between demographic variables and course completion. After assessing that all relevant assumptions were met, a point biserial test (similar to a Pearson correlation) was used for the association of demographic variables and course completion with baseline stigma. Pearson’s correlation test assessed associations between age and the baseline stigma scores. If a participant’s demographic variable was unknown, that participant was excluded from that specific demographic variable analysis, except for age, where we use the mean age of those subcategories.

Total ASI full scale and subscales stigma scores were calculated by summing the relevant items and reversing the score when appropriate. If a respondent had more than 30% of the items missing for a given scale, the respondent was excluded from the analysis. If less than 30% of the responses were missing, they were imputed. Valid mean substitution (VMS) was the most robust imputation method for the nature of missing data in the dataset. Using the last observation carried forward often results in bias (Carpenter & Kenward, 2007), while VMS is appropriate if both the percentage of missing participants and of missing data are low (Dodeen, 2003). Internal consistency of the scales and subscales was measured via Cronbach’s alpha (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). The effect size of stigma levels change was assessed through Cohen’s d (Fritz et al., 2012). The statistical significance of mean stigma score differences between each time point was calculated using paired t-tests. The differences were calculated separately for course completers and non-completers. Changes in item-by-item stigma scores were analyzed by reducing the number of categories from five to three and testing the statistical significance with the Friedman test for non-parametric data.

A sample size of 48 trainees was estimated as needed for 80% power of finding a statistically significant mean change of a similar magnitude (3.2 points) as found in a prior study using the original ASI survey geared toward mental illnesses (Ahn et al., 2014; Lillie et al., 2014). As we could not assume a normal distribution, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the significance of the change in stigma score for each ASI question. All statistical analyses were carried out with a statistical significance threshold of p = 0.05. This study can be considered exploratory as it uses a modified ASI stigma scale conceived for mental illness stigma in general, with the ASI only used in a HIC. Item-by-item responses illustrate the response pattern to various specific attitudes and behaviors linked to stigma. Therefore, we do not adjust p values for repeated measures, an approach supported by the literature (Althouse, 2016; Armstrong, 2014; Gelman et al., 2012; Greenland, 2021; Lillie et al., 2014; Parker & Weir, 2020; Rubin, 2017, 2021; Savitz & Olshan, 1995).

Results

Course Completion, Baseline Stigma, and Demographic Characteristics

Of the 123 health workers who registered for the course, 99 health workers completed both the pre- and post-training period survey, with 56 completing the training and 43 who did not. However, some respondents did not fill the stigma survey portion of the questionnaire. Of the stigma surveys, 13 AUD, 10 TUD, and 12 OSUD had all or more than 30% of the data point missing, with most missing all answers. Therefore, the retention is 84.8%, 83.8%, and 84.8%, respectively. Of those who completed the course, 39 (69.6%) remained involved and completed the questionnaires at the post-RCT stage. Only 1.2% of the answers were missing and imputed among those included. Table 1 summarizes the respondents’ demographic characteristics, with 39 primary care clinicians and 60 support staff.

For AUD, primary care clinicians had lower baseline stigma scores than support staff (R2 = 0.202, p = 0.047). Similarly, those with a diploma or a degree had lower stigma scores for AUD than those with a certificate or secondary education (R2 = − 0.262, p = 0.01), with significant collinearity between the type of health worker and education level (χ2 = 5, p ≤ 0.001). For TUD and OSUD, none of the demographic factors was associated with baseline stigma levels. Course completion was not associated with baseline stigma. But some demographic characteristics influenced course completion. Health workers of outpatient hospital departments were significantly more likely to complete the course than those of a community clinic, odds ratio of 9.53 (95%CI: 3.45, 26.32; p ≤ 0.001), while owning a computer increased the odds by 2.84 (1.14,7.14; p = 0.02). However, those characteristics were not associated with baseline stigma and had no significant collinearity.

At baseline, Cronbach alpha levels are very similar across AUD, TUD, and OSUD (Table 2). They are all above 0.7 for the Social Responsibility subscale, between 0.62 and 0.65 for the full scale, and below 0.4 for the Attitude and the Social Distance subscales.

Changes in Stigma Levels

In the analysis comparing stigma scores before and after the training, statistically significant reductions in stigma toward people with AUD, TUD, and OSUD were observed more often among course completers than non-completers, 10 scales/subscales vs. 7, as can be seen in Table 2, which presents the imputed data. The pattern was very similar in original and imputed data, with only minor variations. As per Fig. 1 and Table 2, in course completers, full-scale stigma levels decreased statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.001) by 10.6% for AUD (large effect size), 12.8% for TUD (medium effect size), and 9.6% for OSUD (large effect size). Among non-completers, the reductions were significant only for TUD and OSUD (medium effect size), with scores decreasing by 8.9% p = 0.018 and 9.4%, p = 0.006. For subscales by substance, course completers experienced a significant decrease in stigma score for all AUD subscales (small to large effect size). In contrast, it decreased significantly only for the Social Distance subscale among non-completers (medium effect size). For TUD, all significant decreases represented medium effect sizes. The Social Distance scores decreased significantly for both completer and non-completers. Non-completers’ TUD Attitude score also decreased significantly. For OSUD, the score significantly reduced for almost all subscales for completers and non-completers (medium to large effect sizes), except for Social Responsibility, which was not reduced for non-completers.

The item-by-item analysis (Table 3) reveals a decrease in stigma in most items of the Attitude subscale for course completers for AUD and OSUD, with few changes for non-completers. However, for Q1, which uses the phrasing of “snapping out of” their problematic substance use, the stigma score increased for OSUD and TUD for completers. For Q3, there was a significant stigma score decrease for course completers, indicating that more agree that effective treatments exist for people with AUD, TUD, or OSUD. Q3 scores did not change for non-completers, meaning there was no change in belief related to effective treatments. The item with the lowest level of stigmatizing attitude was about people with AUD, TUD, or OSUD being treated unfairly. It remained unchanged.

The pattern is less consistent for the Social Distance and Social Responsibility subscales. Still, stigma decreased for Q10 of the Social Distance subscale, indicating a decrease in desire for distanciation toward physicians who had been treated for AUD, TUD, or OSUD. The reduction was regardless of completion status. Also, after the course, the course completers minded less if someone with any of the SUD would sit next to them, while it changed only for TUD for non-completers (Q7). There were more statistically significant changes in stigma among course completers than non-completers across all substances and subscales (23 vs 13).

For course completers who participated in the RCTs (n = 39), per Table 4, the overall pattern from before the courses to after the RCTs is very similar to pre- to post-courses, with significant decreases in stigma for all full scales and most subscales. Between the completion of the training and the end of the RCTs, there was a significant re-increase in stigma in the Attitude subscale for OSUD, with no other discernible significant changes in full scales or subscales of any substance.

Discussion

We found that course completers experienced significant decreases in stigma for AUD, TUD, and OSUD, with 80% in the medium to large effect size ranges. While there were statistically significant changes in non-completers, the percent changes were generally smaller and for less scale/subscales, especially for AUD. Our study is one of the first on blended-eLearning in LMIC and its impact on health workers’ stigma toward AUD, TUD, or OSUD, filling an important gap in the literature (Kilian et al., 2021). Our findings are consistent with previous literature in suggesting that structured training following anti-stigma best practices combined with mentorship and reflective exercises for practicing health workers can contribute to reducing SUD stigma (Finkelstein & Lapshin, 2007; Griffiths & Christensen, 2007; Griffiths et al., 2004; Lillie et al., 2014; Patten et al., 2012). In addition, our courses covered communications and motivational interviewing while emphasizing the potential for recovery. Those are also considered important components of effective SUD stigma interventions (Bielenberg et al., 2021; Knaak et al., 2014).

Our study supports prior findings that eLearning courses can be completed by a majority of interested health workers (57%) in an LMIC setting when they have access to the Internet and a computer in the clinic, even without financial incentives (Dagys et al., 2015; Kebaetse et al., 2014; Marrinan et al., 2015; Sissine et al., 2014; Nyarango, 1991).

Also, our study found that baseline stigma was not associated with course completion, suggesting the level of stigma before the course began did not influence perseverance in completing the course, an encouraging finding for extrapolating these data to other populations. However, rates of course completion could be improved by better access to computers (as computer ownership was associated with course completion), and it might be easier to complete the course in hospital outpatient departments than in community clinics, with field observation suggesting it might be because of better computer access in hospitals than in community clinics, as well as workload distribution and perhaps even internet reliability.

In our subset of health workers, a higher education level or being a clinician (correlated with education level) was associated with lower AUD stigma at baseline. Other studies carried out in HICs found a similar association between education and mental health stigma in general (Corrigan & Watson, 2007; Papadopoulos et al., 2002; Song et al., 2005). However, we did not find that association for TUD or OSUD, suggesting the association might not be as consistent across substances or in LMICs. These novel findings in an LMIC context might indicate that education is not as important a predictor of stigma as in HIC contexts or toward SUDs compared to mental illnesses in general. The lack of association with age and gender for all substances is congruent with prior studies finding mixed associations with stigma for mental illnesses or SUDs (Corrigan & Watson, 2007; Hartini et al., 2018; Papadopoulos et al., 2002; Song et al., 2005).

Our study’s greater impact on AUD stigma is consistent with a central focus of the training and the RCTs. Similarly, Puskar et al. (2013) found a more substantial decrease in stigma related to the main topic of their educational intervention. If the eDATA-K module on stigma was very general and did not focus on a particular substance group, the courses focused more on treatment for AUD than OSUD, and so did the patient interactions.

As we found some significant changes among non-completers, although, for fewer substances and fewer items than among course completers, and with smaller effect sizes, this finding of an impact even on those who receive only a partial dose merits discussion. Most of the non-completers did finish at least one of the modules or participated in the peer and mentor activities of the course. Perhaps partial exposure to the training and being in an environment where more attention is given to SUD, with other staff also discussing these issues more openly, could have contributed to changes in health workers’ SUD stigma, even if they did not complete the course. Part of the changes could also be due to a social desirability bias, which could be expressed more after the training, especially considering that both completers and non-completers shared the same clinical settings. Even pre-course levels might have been influenced by social desirability. It is noteworthy that both course completers and non-completers were exposed to people in higher management positions expressing support for expanding access to treatment for SUD and encouraging health workers to take the online courses and participate in the study. Therefore, the health workers might not be representative of those in other contexts or settings.

Despite our study being sufficiently powered only to detect differences between the pre- and post-training period in full scales, the magnitude of change in the subscales, and even in individual survey items, was sufficient to observe some significant changes, especially in the AUD Attitude subscale. It was the Social Responsibility subscale that showed the least change in our study. This might also be due to cultural factors. Some questions related to donating time or funds, joining protests, or signing petitions might not be culturally normative or easy to achieve in an LMIC context.

Interestingly, our results showed a slight increase in agreement post-training with the Attitude subscale statement that people with AUD could “snap out” of it if they wanted to. The original ASI survey demarks an increase in agreement to that statement as an increase in stigma. This might be a valid interpretation in our study, meaning that the training increased that type of stigmatizing attitude. However, in the context of eDATA-K, that interpretation might not tell the whole story. We suspect that a more accurate interpretation is that trainees now feel more confident that people can change their behaviors even if they suffer from a SUD, while before, they would have thought that most people who suffer from a SUD would not be able to change, making it harder for them to “snap out of it.” In other words, we believe that the training increased the health workers’ confidence in the substance user’s ability to change their substance use patterns, alongside health workers’ increased self-efficacy, consistent with answers to other survey items and supported by other studies part of the eDATA-k program of research (Clair et al., in press; Clair et al., 2019, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2016b, 2016c; Hsiang-Te Tsuei et al., 2017).

Measurement of AUD, TUD, and OSUD stigma via the modified ASI might lack internal consistency. The full scale falls close to the acceptable level of a Cronbach alpha of about 0.70. The Social Responsibility subscale is consistently above that threshold (Taber, 2018). But, the Attitude and Social Distance subscales have particularly low Cronbach alpha’s, indicating a need for caution in interpretation. Regardless, Cronbach alpha’s are not without issues, and factor analyses can help further assess the internal consistency and validity of scales and subscales (Taber, 2018). Further research is needed to validate stigma scales for specific substances and for the multitude of dimensions of stigma, even if validated vignetter evaluations or scales for self-stigma among those using substances exist (Brown, 2011; Smith et al., 2016).

Nonetheless, the results of this study, using a modified version of the ASI, are similar to other eDATA-K results using the Opening Minds Scale for Health Care Providers (OMS-HC) to measure stigma in health professionals (Clair et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2019). The OMS-HC was originally designed to measure health workers’ stigma toward mental health patients (Kassam et al., 2012) and was also modified to ask about SUD. While the ASI was altered in a similar manner to ask about SUD rather than mental illnesses, it was geared to the general population and not health workers. With the OMS-HC, there was no change in stigma levels of those who did not complete the courses, with significant changes in course completers, but only for TUD and OSUD (Clair et al., 2016a, 2019), suggesting different sensitivities of those different scales to measure changes in various stigma components. The fact that both scales showed a decrease in stigma for some substances for course completers and fewer/less or no changes for non-completers supports the interpretation that stigma levels changed more comprehensively in course completers than in non-completers, and that blended-eLearning courses can impact stigma. However, further study on both of these instruments’ validity and comparability for measuring stigma associated with various SUD in the general population versus a health worker population would be worthwhile, especially in varied cultures and in LMIC contexts.

Systematic reviews identified multiple studies where contact-based education interventions were associated with decreased stigma (Corrigan et al., 2012; Livingston et al., 2012). However, we did not find a further decrease in stigma toward those with AUD, TUD, or OSUD after the period of intense exposure to people affected by a risky level of use of those substances during the RCT phase. This suggests that the exercise of practicing the screening and BI on their patients, even during the training, without a mentor or teacher organizing a specific contact with someone with any of the SUD (as is usually done in contact-based stigma intervention), resulted in enough contact to maximize the reduction in stigma as measured by the ASI, alongside the reflection and other components of the course. Furthermore, some recent studies cast doubt on the added effectiveness of in-person contact-based interventions compared to others and that online contact can also be effective (Jorm, 2020; Imperato et al., 2021). Alternatively, the ASI might not have the sensitivity to measure a further decrease in stigma in the Kenyan context, as our program of research, especially our qualitative findings (Clair et al., 2022a, 2022b), supports a further decrease in stigma during that period (Clair et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2019). Findings for eDATA-K suggest that there was not only a further reduction in stigma but that the stigma reduction, alongside increased self-efficacy, promoted large changes in behaviors in health workers, as well as being noted by the RCT participants (Clair et al., 2022b) and that those stigma changes promoted the continuation of the services after the end of the RCT (Clair et al., 2022a, 2022b). Those qualitative findings raise the question of the validity of the adjusted ASI stigma scale in measuring changes in stigma and stigmatizing behaviors in health workers in an LMIC context.

Some might consider it a limitation to perform item-by-item analyses, which increase the number of the statistical tests, without using a correction to decrease the probability of type 1 error. We argue that none of those item-by-item tests is used to answer the hypothesis of a decrease in stigma in health workers, meaning there is no type 1 error in relation to our main study hypothesis, and no corrections are needed (Althouse, 2016; Armstrong, 2014; Gelman et al., 2012; Greenland, 2021; Lillie et al., 2014; Parker & Weir, 2020; Rubin, 2017, 2021; Savitz & Olshan, 1995). Furthermore, the pattern of significance in the item-by-item analysis is relatively consistent both across substances and across types of completers, as well as with similar questions of the OMS-HC administered as part of eDATA-K to the same health workers (Clair et al., 2016a, 2019). In addition, the item-by-item analysis provides insight into which specific aspects of stigma were impacted, which is particularly important considering low Cronbach alphas for several scales and subscales.

Our study is limited in its ability to separate the effect of social desirability versus (a) the impact of being in an environment where more attention is being given to those with SUD in the training period and (b) partial exposure to the training (as most course non-completers viewed part of the training). Another limitation is the use of a convenience sample of health workers interested in taking the NextGenU.org courses on AUD, TUD, and OSUD in preselected facilities in areas where the leadership indicated to the health worker that there was a need to address those conditions. Therefore, the results might not apply to health workers in other contexts. Our findings, per the paucity of literature on the topic, suggest a need for more studies to understand stigmatizing attitudes and validate stigma scales for health workers in LMICs, as well as high-quality trials testing interventions considering cultural differences (Fabrega, 1991; Sapag et al., 2018). We agree with Witte et al. (2019) that there is a need for studies on substance use stigma specifically (vs. solely on general mental illnesses), including stigma on the use of substances at a level that is not considered pathological versus levels reaching the criteria for substance use disorder.

In conclusion, our study supports that blended-eLearning can promote a decrease in stigma levels in health workers in LMICs, and is a feasible way to provide AUD, TUD, and OSUD relevant education. More research is needed to further test eLearning intervention’s impact on stigma and adequate measurement of stigma in LMICs, specifically for various SUDs.

References

Ahern, J., Stuber, J., & Galea, S. (2007). Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2–3), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.014

Ahn, C., Heo, M., & Zhang, S. (2014). Sample size calculations for clustered and longitudinal outcomes in clinical research. CRC Press.

Ai, J., & Laffey, J. (2007). Web mining as a tool for understanding online learning. In (Vol. 3.2, pp. 160–169): MERLOT Journal of On-line Learning and Teaching.

Althouse, A. D. (2016). Adjust for multiple comparisons? It’s not that simple. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 101(5), 1644–1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.024

Armstrong, R. A. (2014). When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 34(5), 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131

Bahia, K., & Suardi, S. (2019). The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2019. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/GSMA-State-of-Mobile-Internet-Connectivity-Report-2019.pdf

Ballew, P., Castro, S., Claus, J., Kittur, N., Brennan, L., & Brownson, R. C. (2013). Developing web-based training for public health practitioners: What can we learn from a review of five disciplines? Health Education Research, 28, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cys098

Bari, M., Djouab, R., & Hoa, C. P. (2018). Elearning current situation and emerging challenges. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 97–109.

Bayer, R. (2008). Stigma and the ethics of public health: Not can we but should we. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.017

Bayer, R., & Stuber, J. (2006). Tobacco control, stigma, and public health: Rethinking the relations. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 47–50. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.071886

Bielenberg, J., Swisher, G., Lembke, A., & Haug, N. A. (2021). A systematic review of stigma interventions for providers who treat patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 131, 108486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108486

Brown, S. A. (2011). Standardized measures for substance use stigma. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 116(1), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.005

Burgess, D. J., Fu, S. S., & van Ryn, M. (2009). Potential unintended consequences of tobacco-control policies on mothers who smoke: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(2 Suppl), S151-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.006

Carpenter, J. R., & Kenward, M. G. (2007). Missing data in randomised controlled trials: A practical guide. In: Health Technology Assessment Methodology Programme.

Chapman, S., & Freeman, B. (2008). Markers of the denormalisation of smoking and the tobacco industry17. Tobacco Control, 17, 25–31.

Clair, V., Mutiso, V., Musau, A., Mokaya, A., Frank, E., & Ndetei, D. M. (2016a). Decreasing stigma towards alcohol, tobacco and other substance use through online training [Abstract]. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(3), E17–E18. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000224

Clair, V., Mutiso, V., Musau, A., Mokaya, A., Tele, A., Frank, E., & Ndetei, D. (2016b). Health workers learned brief intervention online through NextGenU.org and deliver them effectively [Abstract]. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(3), E17. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000224

Clair, V., Mutiso, V., Musau, A., Ndetei, D., & Frank, E. (2016c). Online learning improves substance use care in Kenya: Randomized control trial results and implications [Abstract]. Annals of Global Health, 82(3), 320–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2016.04.585

Clair, V., Atkinson, K., Musau, A., Mutiso, V., Bosire, E., Isaiah, G., Ndetei, D., & Frank, E. (2022a). Implementing and sustaining brief addiction medicine interventions with the support of a quality improvement blended-elearning course: Learner experiences and meaningful outcomes in Kenya. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00781-6

Clair, V., Musau, A., Mutiso, V., Tele, A., Atkinson, K., Rossa-Roccor, V., Ndetei, D., & Frank, E. (2022b). Blended-eLearning improves alcohol use care in Kenya: Pragmatic randomized control trials results and parallel qualitative study implications. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00841-x

Clair, V., Rossa-Roccor, V., Mokaya, A. G., Mutiso, V., Musau, A., Tele, A., Ndetei, D., & Frank, E. (2019). Peer and mentor-enhanced web-based training on substance use disorders: A promising approach in low-resource settings. Psychiatric Services, 70(11), 1068–1071. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900201

Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1(1), 16–20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16946807

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2007). The stigma of psychiatric disorders and the gender, ethnicity, and education of the perceiver. Community Mental Health Journal, 43, 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-007-9084-9

Crisp, A. H., Gelder, M. G., Rix, S., Meltzer, H. I., & Rowlands, O. J. (2000). Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 4–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10945080

Cunningham, JA., Sobell, LC., Chow, VM. (1993). What’s in a label? The effects of substance types and labels on treatment considerations and stigma. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 54(6): 693–699. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8271805

Cunningham, J. A., Sobell, L. C., Freedman, J. L., & Sobell, M. B. (1994). Beliefs about the causes of substance abuse: A comparison of three drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse, 6(2), 219–226. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7804020

Dagys, K. M., Popat, A., & Aldersey, H. M. (2015). The Applicability of eLearning in Community-Based Rehabilitation. Societies, 5(4), 831–854. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5040831

Desjarlais, R. (1995). World mental health: Problems and priorities in low-income countries. Oxford University Press.

Dodeen, H. M. (2003). Effectiveness of valid mean substitution in treating missing data in attitude assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(5), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930301674

Fabrega, H. (1991). Psychiatric stigma in non-Western societies. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 32(6), 534–551. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1778081

Finkelstein, J., & Lapshin, O. (2007). Reducing depression stigma using a web-based program. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 76, 726–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.07.004

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., & Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(1), 2.

Gelman, A., Hill, J., & Yajima, M. (2012). Why we (usually) don’t have to worry about multiple comparisons. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2011.618213

Goldsmith, M., Stewart, L., & Ferguson, L. (2006). Peer learning partnership: An innovative strategy to enhance skill acquisition in nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 26(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2005.08.001

Graham, H. (2012). Smoking, stigma and social class. Journal of Social Policy., 41, 83–89.

Greenland, S. (2021). Analysis goals, error-cost sensitivity, and analysis hacking: Essential considerations in hypothesis testing and multiple comparisons. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 35(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12711

Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2007). Internet-based mental health programs: A powerful tool in the rural medical kit. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 15, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00859.x

Griffiths, K. M., Christensen, H., Jorm, A. F., Evans, K., & Groves, C. (2004). Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.185.4.342

Hartini, N., Fardana, N. A., Ariana, A. D., & Wardana, N. D. (2018). Stigma toward people with mental health problems in Indonesia. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 11, 535.

Hsiang-Te Tsuei, S., Clair, V., Mutiso, V., Musau, A., Tele, A., Frank, E., & Ndetei, D. (2017). Factors influencing lay and professional healthworkers’ self-efficacy in identification and intervention for alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use disorders in Kenya. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–16.

Humeniuk RE, H.-E. S., Ali RL, Poznyak V, Monteiro MG. (2010). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for use in primary care.

Imperato, C., Schneider, B. H., Caricati, L., Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Mancini, T. (2021). Allport meets Internet: A meta-analytical investigation of online intergroup contact and prejudice reduction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 81, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.01.006

Jorm, A. F. (2020). Effect of contact-based interventions on stigma and discrimination: A critical examination of the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 71(7), 735–737. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900587

Kassam, A., Papish, A., Modgill, G., & Patten, S. (2012). The development and psychometric properties of a new scale to measure mental illness related stigma by health care providers: The Opening Minds Scale for Health Care Providers (OMS-HC). BMC Psychiatry, 12, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-62

Kebaetse, M. B., Nkomazana, O., & Haverkamp, C. (2014). Integrating eLearning to support medical education at the New University of Botswana School of Medicine. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 12(1), 43–51.

Keyes, K. M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., McLaughlin, K. A., Link, B., Olfson, M., Grant, B. F., & Hasin, D. (2010). Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172, 1364–1372. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq304

Kilian, C., Manthey, J., Carr, S., Hanschmidt, F., Rehm, J., Speerforck, S., & Schomerus, G. (2021). Stigmatization of people with alcohol use disorders: An updated systematic review of population studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(5), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14598

Knaak, S., Modgill, G., & Patten, S. B. (2014). Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: A data synthesis of evaluative studies. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 59(10 Suppl 1), S19–S26. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901s06

Lillie, E., Koller, M., & Stuart, H. (2014). Opening minds at university: Results of a contact-based anti-stigma intervention. Mental Health Commission of Canada. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Stigma_Opening_Minds_at_University_ENG_0_1.pdf

Lim, S. S., Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Danaei, G., Shibuya, K., Adair-Rohani, H., . . . Memish, Z. A. (2012). A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 380(9859), 2224-2260. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61766-8

Lindberg, M., Vergara, C., Wild-Wesley, R., & Gruman, C. (2006). Physicians-in-training attitudes toward caring for and working with patients with alcohol and drug abuse diagnoses. Southern Medical Journal, 99(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.smj.0000197514.83606.95

Lipozencić, J. (2006). Disease Control Priorities Project (DCPP) and 2nd Global Meeting of the Inter-Academy Medical Panel (IAMP), April 2–6, 2006 Beijing, China. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat, 14(2), 135. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16859621

Livingston, J. D., Milne, T., Fang, M. L., & Amari, E. (2012). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: A systematic review. Addiction, 107, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x

Marrinan, H., Firth, S., Hipgrave, D., & Jimenez-Soto, W. (2015). Let’s take it to the clouds: The potential of educational innovations, including blended learning, for capacity building in developing countries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 4(9), 571–573.

Murray, C. J. L., Aravkin, A. Y., Zheng, P., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., . . . Lim, S. S. (2020). Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1223-1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2

Nichter, M., Greaves, L., Bloch, M., Paglia, M., Scarinci, I., Tolosa, J. E., & Novotny, T. E. (2010). Tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries: The need for social and cultural research. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 89(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016341003592552

Nyarango, P. M. (1991). Distance learning for rural medical officers in Kenya: The first pilot project. East African Medical Journal, 68(9), 741–743. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1797538

Papadopoulos, C., Leavey, G., & Vincent, C. (2002). Factors influencing stigma. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37(9), 430–434.

Parker, R. A., & Weir, C. J. (2020). Non-adjustment for multiple testing in multi-arm trials of distinct treatments: Rationale and justification. Clinical Trials, 17(5), 562–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774520941419

Patel, V. (2007). Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. British Medical Bulletin, 81–82, 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm010

Patten, S. B., Remillard, A., Phillips, L., Modgill, G., Szeto, A. C., Kassam, A., & Gardner, D. M. (2012). Effectiveness of contact-based education for reducing mental illness-related stigma in pharmacy students. BMC Medical Education, 12, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-120

Penn, D. L., & Couture, S. M. (2002). Strategies for reducing stigma toward persons with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1(1), 20–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16946808

Puskar, K., Gotham, H. J., Terhorst, L., Hagle, H., Mitchell, A. M., Braxter, B., Fioravanti, M., Kane, I., Talcott, K. S., Woomer, G. R., & Burns, H. K. (2013). Effects of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) education and training on nursing students’ attitudes toward working with patients who use alcohol and drugs. Subst Abus, 34(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2012.715621

Ritson, E. B. (1999). Alcohol, drugs and stigma. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 53(7), 549–551. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10692742

Room, R. (2005). Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230500102434

Rubin, M. (2017). Do p values lose their meaning in exploratory analyses? It depends how you define the familywise error rate. Review of General Psychology, 21(3), 269–275.

Rubin, M. (2021). When to adjust alpha during multiple testing: A consideration of disjunction, conjunction, and individual testing. Synthese, 199(3), 10969–11000.

Sapag, J. C., Sena, B. F., Bustamante, I. V., Bobbili, S. J., Velasco, P. R., Mascayano, F., Alvarado, R., & Khenti, A. (2018). Stigma towards mental illness and substance use issues in primary health care: Challenges and opportunities for Latin America. Global Public Health, 13(10), 1468–1480. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1356347

Savitz, D. A., & Olshan, A. F. (1995). Multiple comparisons and related issues in the interpretation of epidemiologic data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 142(9), 904–908. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117737

Schomerus G., L. M., Holzinger A., Matschinger H., Carta M. G., AngermeyerM. C. (2011). The stigma of alcohol dependence compared with other mental disorders: A review of population studies. Alcohol Alcohol.

Sissine, M., Segan, R., Taylor, M., Jefferson, B., Borrelli, A., Koehler, M., & Chelvayohan, M. (2014). Cost comparison model: Blended eLearning versus traditional training of community health workers. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics, 6(3), e196–e196. https://doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v6i3.5533

Smith, L. R., Earnshaw, V. A., Copenhaver, M. M., & Cunningham, C. O. (2016). Substance use stigma: Reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.019

Song, L.-Y., Chang, L.-Y., Shih, C.-Y., Lin, C.-Y., & Yang, M.-J. (2005). Community attitudes towards the mentally ill: The results of a national survey of the Taiwanese population. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 51(2), 162–176.

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53.

The World Bank. (2020). Individuals using the internet (% of population) | Data. Retrieved from https://data-worldbank-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?view=map

van Boekel, L. C., Brouwers, E. P. M., van Weeghel, J., & Garretsen, H. F. L. (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(1–2), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

Waddell, D. L., & Dunn, N. (2005). Peer coaching: The next step in staff development. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 36(2), 84–89; quiz 90–81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15835584

Witte, T. H., Wright, A., & Stinson, E. A. (2019). Factors influencing stigma toward individuals who have substance use disorders. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(7), 1115–1124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1560469

World Health Organization. (2010). mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: Scaling up care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge the financial contributions of Grand Challenges Canada, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Sciences, the Annenberg Physician Training Program in Addiction Medicine, the IMPART Addiction Research Training, and the Canada Research Chair program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Kenya Medical Research Institute Ethics Review Committee and the University of British Columbia Human Ethical Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Clair, V., Rossa-Roccor, V., Mutiso, V. et al. Blended-eLearning Impact on Health Worker Stigma Toward Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Psychoactive Substance Users. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 3438–3459 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00914-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00914-x