Abstract

Geographic accessibility has been linked to gambling behavior, but little is known about whether the perception of gambling availability in both offline and online venues is prospectively associated with adolescent gambling behavior. Further, relatively few studies have analyzed the interaction between environmental and individual factors in explaining adolescent gambling and problem gambling. This prospective study examined the association between perceived gambling availability, gambling frequency, and problem gambling among 554 adolescents aged 13–17 years (mean = 15.1, female 47.4%) and explored the moderating role of self-efficacy to control gambling in these associations. Participants completed assessments of perceived gambling availability and gambling self-efficacy at baseline. Gambling frequency and problem gambling were measured at follow-up. Two separate hierarchical regression models were applied to analyze the relationship of perceived gambling availability with gambling behavior and the moderating role of gambling self-efficacy. Results showed that a greater perception of gambling availability was associated with a higher gambling frequency and more problem gambling in adolescents. The impact of perceived gambling availability on gambling frequency and problem gambling was lower among participants with moderate gambling self-efficacy in comparison with participants with low gambling self-efficacy. In those adolescents with high self-efficacy to control gambling, perceived gambling availability was not associated either with gambling frequency or problem gambling. These results suggest the usefulness of implementing regulatory policies aimed at reducing gambling availability in adolescents, and the design of preventative interventions aimed at enhancing self-efficacy to control gambling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the last decade, gambling has become a common form of entertainment and social interaction, particularly among adolescents and young people (Molinaro et al., 2018). In Europe, 11–33% of adolescents aged 15–16 years old reported gambling in the last 12 months, with 1.4% classified as problematic gamblers (ESPAD Group, 2020), defined as having difficulties in limiting money and/or time spent on gambling that result in significant harm for the gambler and/or people in his/her immediate social environment (Neal et al., 2005).

Interventions and policy responses to gambling behavior and problem gambling among adolescents should target the contributing factors. Previous studies (e.g., Bonamis, 2019; Kato & Goto, 2018; Williams et al., 2012) have consistently shown the role of gambling availability as a determinant of gambling behavior. The fact that gambling behavior in a society is closely associated with the degree of gambling availability and is supported by the availability theory (Bruun et al., 1975; Stockwell & Gruenewald, 2003). According to this theoretical framework, the greater the availability of gambling in a society, the higher the average of gambling use and gambling-related problems.

Gambling availability has been conceptualized in terms of both geographic gambling accessibility and perceived gambling availability. The former implies that people within the same community are equally influenced by the physical presence of nearby gambling facilities (Abdi et al., 2015; Kang et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2011). Perceived gambling availability refers to individual’s subjective estimation about the opportunities to access to gambling facilities (Wechsler et al., 2002) and has been suggested as a better determinant of gambling behavior in comparison to geographic gambling availability (Ofori Dei et al., 2020).

Online gambling facilitates access to gambling even in areas where there are no gambling venues (Griffiths & Barnes, 2008; Wood et al., 2007), and there is evidence that problem gambling prevalence rates are significantly higher among people who gamble online in comparison with those who gamble offline (Chóliz et al., 2021; Griffiths, et al., 2009;). However, to our knowledge, only one previous study (Botella-Guijarro et al., 2020) has examined the relationship of perceived online gambling availability and gambling frequency. Furthermore, as far as we know, the study by Botella-Guijarro et al. (2020) is the only one that has employed a longitudinal approach to analyze the relationships between gambling availability and gambling behavior.

In the field of gambling, self-efficacy is referred as the belief of an individual about his/her ability to resist an opportunity to gamble in a given situation (Casey et al., 2008). It has been shown that adolescents with high self-efficacy to control gambling behavior tend to gamble less frequently (León-Jariego et al., 2020) and show fewer gambling-related problems (St-Pierre et al., 2015). According to the Bandura’s Theory of Self-efficacy (1977), although environmental factors (e.g., gambling availability) impact people’s behaviors, the role of individual factors (e.g., self-efficacy) must be also taken into account. Consistently with this postulates, self-efficacy has shown to moderate the impact of environmental factors on problem gambling. For example, Quinn et al. (2019) found that the impact of gambling advertising on problem gambling was lower among individuals with high self-efficacy to control gambling in comparison with those with low self-efficacy. Therefore, it could be expected that gambling self-efficacy ameliorates the impact of perceived gambling availability on adolescent gambling behavior. However, as far as we are aware, no previous studies have analyzed the moderating role of gambling self-efficacy on these relationships.

The majority of gambling research has focused on adolescent problem gambling because of its negative consequences (e.g., Livazović & Bojčić, 2019). Nevertheless, given the strong association between early adolescent gambling and problem gambling in adulthood (Bradley & James, 2020; King et al., 2020), examining the environmental and personal factors related to gambling frequency in adolescents could be useful for preventing gambling-related problems in adulthood.

Considering the previous, further research on the prospective influence of perceived offline and online gambling availability on gambling behavior is needed. Such information could be useful for guiding the design of regulatory policies that reduce adolescents’ access to gambling. Moreover, examining individual factors (e.g., self-efficacy) that could reduce the influence of perceived availability could be useful to improve the effectiveness of gambling-related preventive interventions. Thus, we aimed to (i) prospectively analyze the association between perceived gambling availability and both gambling frequency and problem gambling in a sample of adolescents and (ii) examine whether these associations were moderated by gambling self-efficacy.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We recruited a sample of 869 adolescents (mean age 15.18 years [SD = 1.17], 52.6% males) attending four public high schools in the province of Huelva (Spain). Huelva is a province located in the southwestern of Spain, with a total of 92 public high schools and an estimation of roughly 31,000 students (INE, 2021). The sample was selected based on geographic and social representativeness. Two schools were located in the city of Huelva, one high school on the coast and one in a rural area.

Information was collected by administering questionnaires at two time points: baseline (February 2018–May 2018) and follow-up (1 year later). At both baseline and follow-up, two psychologists administered the questionnaires collectively in classrooms. All participants were informed about the study conditions and the anonymous and voluntary nature of their participation. Written informed consent of parents and participants was obtained before the inclusion of the participants in the study. To match the baseline and follow-up questionnaires, a self-generated code was assigned to each participant. From the initial 869 participants, 554 adolescents completed the follow-up questionnaire, which constituted the final sample of this study.

In order to analyze differences between those adolescents who participated in the follow-up and those who did not, chi-square statistic was used for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U test was applied in case of lack of normality of data for continuous variables. Non-statistically significant differences were found between those adolescents who participated in the follow-up and those who did not in terms of age (Mann–Whitney U = 84,142.5; z = − 0.909, p = 0.363), gender (χ2 = 0.646, p = 0.422), perceived gambling availability (Mann–Whitney U = 75,749.5; z = − 0.553, p = 0.580), gambling self-efficacy (Mann–Whitney U = 50,310; z = − 0.974, p = 0.330), and problem gambling (Mann–Whitney U = 83,612; z = − 1.773, p = 0.076). Nevertheless, non-participants reported receiving more weekly pocket money (Mann–Whitney U = 64,732; z = − 2.957, p = 0.003) and a higher gambling frequency (Mann–Whitney U = 77,229; z = − 3.452, p = 0.001).

The protocol for this research study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Huelva.

Instruments

Sociodemographics

We collected information on the gender and age of the participants, and an open-ended response format was used to assess the amount of weekly pocket money they receive.

Perceived Gambling Availability in Adolescents at Baseline

This was measured using the accessibility subscale of the Early Detection of Gambling Abuse Risk among Adolescent questionnaire (EDGAR; Lloret et al., 2018). This instrument is composed of six items, two of which are reverse-scored, rated on a 5-point Likert Scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Four of these items refer to the respondent’s knowledge and perceived availability of online gambling (e.g., “I know websites where I could gamble”) and gambling products in offline venues (e.g., “It is difficult to find offline venues where to gamble”), and the final two items include measures of perceived permissiveness to gamble during adolescence (e.g., “It would be easy to gamble as a minor”). Responses are summed to obtain a measure of availability, with higher scores representing higher perception of perceived gambling availability. The Cronbach’s alpha value in the present study was 0.71.

Gambling Self-Efficacy at Baseline

We used the Gambling Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (GSEQ; May et al., 2003) in its Spanish version (Winfree et al., 2013) to assess the adolescents’ perceived efficacy to control gambling in 16 situations. Responses are measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). Higher scores are indicative of higher levels of perceived self-efficacy to control gambling behavior. The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.98.

Gambling Frequency in the Last 12 Months at Follow-up

Six types of gambling activities were analyzed (sports bets, fruit/slot machines, roulettes, poker, scratch-cards or lotteries, and bingo), including both online and offline gambling (1 = never, 2 = less than monthly, 3 = monthly, 4 = weekly, and 5 = daily). An overall index of gambling frequency in the last 12 months (range: 12–60) was calculated by summing the scores across all gambling activities.

Problem Gambling Behavior at Follow-up

This was measured using the South Oaks Gambling Screen-Revised for Adolescents (SOGS-RA; Winters et al., 1993) it its Spanish version (Secades & Villa, 1998). The SOGS-RA includes 12 items (response options: “yes” = 1 or “no” = 0) which explore negative feelings and behaviors associated with gambling consequences. SOGS-RA scores provide three categories: (a) non-gambler or non-problematic gambler (scores ≤ 1); (b) at-risk gambler (scores 2–3); and (c) problematic gambler (scores ≥ 4). For the purpose of this study, responses were summed into a single measure ranging from 0 (non-problem gambling) to 12 (greater problem gambling). The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.72.

Analysis Plan

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted to characterize the sample and to examine the relationships between the study variables. We then conducted separate hierarchical linear regression analyses to test the utility of perceived gambling availability and the moderating role of gambling self-efficacy in explaining gambling frequency (model 1) and problem gambling (model 2). Previous research has shown that gender, age, and disposable income are associated with adolescent gambling behavior (Escario & Wilkinson, 2020). Thus, these variables were included as covariates in both regression models, as was the high school of origin. For each model, independent variables were entered in the following order: in step 1, we included gender, age, weekly pocket money received, and school of origin; in steps 2 and 3, the main effects of gambling self-efficacy and perceived gambling availability were entered, respectively; and in step 4, we entered the two-way interaction between the main effects (i.e., perceived gambling availability × gambling self-efficacy). Using PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017), simple slope post hoc analyses were conducted to explore significant interactions and determine the strength of the association between perceived gambling availability and both dependent variables at low (1 SD below the mean), moderate (sample mean) and high values (1 SD above the mean) of gambling self-efficacy. Significant transition points were examined using the Johnson-Neyman technique, which indicates values of the moderator for which the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variables transitions from significant to non-significant. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS v.25.

Results

More than a half of the participants (52.6%) were male, with a mean age of 15.1 years (SD = 1.2). Of the sample, 52.9% reported not gambling during the last 12 months at follow-up, 34.5% indicated they had gambled less than monthly, 9.4% gambled monthly, and 3.2% gambled weekly or more. According to the SOGS-RA, 91.2% of the participants were classified as non-problem gamblers, while the remaining participants were classified as at-risk gamblers (6.5%) or problem gamblers (2.3%).

As shown in Table 1, perceived gambling availability was positively correlated with gambling frequency and problem gambling, but not with gambling self-efficacy. Conversely, gambling self-efficacy was negatively correlated with gambling frequency and problem gambling. In addition, gambling frequency and problem gambling were strongly correlated.

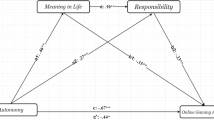

Table 2 displays the results of the two separate hierarchical regression models to explain gambling frequency and problem gambling. In the first hierarchical regression model, after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and self-efficacy, increases in perceived gambling availability at baseline were associated with increases in gambling frequency at follow-up (β = 0.19, p < 0.001). In addition, as shown in Table 2, the interaction term of perceived gambling availability and gambling self-efficacy was significant (β = − 0.10, p = 0.023). Simple slope post hoc analyses indicated that perceived gambling availability predicted gambling frequency when gambling self-efficacy was low (b = 0.85, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001) and moderate (b = 0.56, SE = 0.14, p < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 1, perceived gambling availability was more positively related to gambling frequency when gambling self-efficacy was low than when it was moderate. In contrast, when gambling self-efficacy was high, the relationship between perceived gambling availability and gambling frequency was not significant (b = 0.30, SE = 0.17, p = 0.085).

In the second hierarchical regression model, after controlling for sociodemographics and self-efficacy, perceived gambling availability at baseline (β = 0.14, p = 0.006) was related to problem gambling at follow-up. Further, the effect of the interaction term was significant (β = − 0.13, p = 0.005; see Table 2). Similar to model 1, the simple slope post hoc analyses in model 2 revealed that when gambling self-efficacy was low (b = 0.31, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001) and moderate (b = 0.17, SE = 0.05, p = 0.003), perceived gambling availability was associated with problem gambling. This relationship was stronger when gambling self-efficacy was low as opposed to moderate (Fig. 2). When gambling self-efficacy was high, perceived gambling availability was not related to adolescent problem gambling (b = 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = 0.545).

Although the moderating role of gambling self-efficacy was significant in both models, the Johnson-Neyman procedure revealed two different transition points in which the relationships between perceived gambling availability, and each of the two dependent variables became non-significant. In particular, a non-significant relationship was found between perceived gambling availability and gambling frequency among those who scored 4.87 or more on gambling self-efficacy (29.3% of the sample), while a non-significant relationship with problem gambling was found in adolescents with scores of 4.32 or more (53.1% of the sample).

Discussion

Previous studies have associated both perceived gambling availability (Botella-Guijarro et al., 2020; Gavriel-Fried et al., 2021; Ofori Dei et al., 2020; Wickwire et al., 2007) and gambling self-efficacy (León-Jariego et al., 2020; St-Pierre et al., 2015) with adolescent gambling behavior. To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively analyze the relationship of a measure of gambling availability in both offline and online venues with gambling frequency and problem gambling. The current study is also the first to analyze the moderating role of gambling self-efficacy in these previously proposed relationships. Our findings suggests that perceived gambling availability is longitudinally associated with gambling frequency and adolescent problem gambling, and gambling self-efficacy moderates these relationships, so that when gambling self-efficacy increases, the effect of perceived gambling availability on adolescent gambling behavior decreases and even disappears.

Consistent with the findings of previous studies that assess perceived gambling availability in both offline and online venues (Botella-Guijarro et al., 2020) and with those that only measured perceived availability of offline facilities (Gavriel-Fried et al., 2021; Wickwire, et al., 2007), our results suggest that perceived availability is a risk factor for gambling frequency. It has been demonstrated that the first gambling experiences usually occur offline (Kang et al., 2020; Törrönen et al., 2020). This could explain why our results are consistent with previous studies showing an association between perceived gambling availability and gambling frequency, regardless of whether these studies measure online (Botella-Guijarro et al., 2020) and/or offline gambling (Wickwire et al., 2007). However, with regard to problem gambling, our results are inconsistent with those of Wickwire et al. (2007), who did not find a relationship between perceived gambling availability and gambling-related problems. This discrepancy could be related to the fact that these authors did not use a measure of gambling availability that includes online gambling, as in the case of our study. Taking into consideration that the prevalence of problem gambling is higher among online gamblers compared with offline gamblers (Griffiths et al., 2009; Wood & Williams, 2009), our results highlight the importance of considering the perception of online gambling availability.

The relationship found between perceived gambling availability and adolescent gambling behavior in this study suggests the need for effective policies aimed at preventing gambling-related harms. Given that frequent gambling during adolescence is associated with the development of gambling disorder in adulthood (Slutske et al., 2014), our findings suggest that policy initiatives that limit gambling opportunities (in offline and online venues) and reinforce restricted access to gambling may be useful in reducing gambling frequency and, consequently, future gambling-related problems. Moreover, our results also suggest that these measures could help to prevent problem gambling during adolescence. Internationally, some governments have moved in this direction, showing how limiting gambling opportunities is effective in reducing gambling and associated problems. For example, the Norwegian government imposed a ban on electronic gaming machines, which resulted in a reduction of gambling prevalence, gambling frequency, and gambling problems (Lund, 2009). Similarly, Nova Scotia removed approximately 30% of their video lottery terminals and observed a substantial reduction in expenditure and gambling time (Corporate Research Associates Inc. & Nova Scotia Gaming Corporation, 2006). In the case of online gambling, multiple regulatory initiatives (e.g., blocking financial transactions and unregulated gambling sites, and the prohibition of certain types of online gambling) have been suggested to be related to the declining number of online gamblers (Gainsbury, 2012; Holliday, 2010).

Policy initiatives involving governmental regulation of gambling such as limiting gambling availability are likely to have a wider impact and produce greater benefits compared with educational approaches based on individual factors (Miller et al., 2014, 2015). Our findings support the development of gambling regulatory policies aimed at restricting gambling accessibility. In addition, the perceived gambling availability that is frequently promoted in gambling advertisements (Hanss et al., 2015) should be addressed. Recommendations include the removal of all gambling marketing on media accessed by youths, banning the advertisements of gambling sponsors in sports and prohibiting advertising content and features that attract youths to gambling (Monaghan et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2018).

Gambling-related behaviors are not only explained by environmental factors, but also by the interaction of these with individual factors (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; Hilbrecht et al., 2020). Our findings make a contribution in this regard and are in line with Banduras’s (1977, 1986) self-efficacy theory, suggesting that even in the presence of environmental cues that encourage gambling, abstinence from gambling is highly dependent on personal efficacy expectations of gambling avoidance. Thus, in our study, as gambling self-efficacy increases, the effect of perceived gambling availability in gambling behavior decreases and even disappears among those adolescents who perceive high self-efficacy to refuse gambling. In a similar vein, a recent cross-sectional study (Quinn et al., 2019) found that gambling self-efficacy is a protective factor against environmental cues such as gambling advertising.

Prevention programs should include strategies to enhance efficacy beliefs to resist environmental cues that trigger gambling behavior. Several mechanisms such as vicarious experiences (e.g., observing how others manage and control their gambling), mastery experiences (e.g., reflecting on past experiences of successful behavior regulation, role-playing), and verbal persuasion (e.g., encouragement from others) have been proposed as practical methods of developing self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986; Clark, 2009; Karatay & Gürarslan Baş, 2017).

Moreover, we found that the relationship between perceived gambling and both gambling frequency and problem gambling turned non-significant at different levels of gambling self-efficacy. In our sample, gambling self-efficacy was shown to protect a higher percentage of adolescents from having gambling problems than from gambling more frequently. Thus, although high levels of gambling self-efficacy could nullify the influence of perceived gambling availability on gambling frequency, it could be even more effective in interventions aimed at reducing gambling-related problems in adolescents.

The major strengths of this study include the use of a measure that assessed adolescents’ perceived gambling availability in both offline and online venues, the longitudinal design, and the analysis of the moderating role of gambling self-efficacy. However, some limitations need to be considered when interpreting our results. First, the non-probabilistic sampling procedure used in the present study limits the generalizability of our findings. To minimize this limitation, the four high schools in our study were selected from different socioeconomic areas. Second, in our study, those adolescents who did not complete follow-up measures reported more frequent gambling and received more weekly pocket money than those who completed them. This limits the generalizability of our results to those adolescents who gamble more frequently and those with more disposal money. Moreover, this limitation introduces selection biases and poses threat to internal validity of the results obtained. Third, self-report data are vulnerable to the effects of recall and social desirability bias, which could have an impact on the validity of our findings.

Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Research

Our findings support the predictive utility of gambling availability for gambling frequency and problem gambling in adolescents. This suggests that reducing gambling opportunities and advertisements and reinforcing restrictions of access to gambling may reduce gambling behavior and its related harms. Moreover, our findings contribute towards understanding how individual characteristics and risky environments interact to explain early gambling behavior. The fact that perceived gambling availability is moderated by self-efficacy highlights the need for preventative educational interventions that enhance efficacy beliefs to reduce the effect of the perception of gambling opportunities on gambling-related behaviors and harms. Strategies aimed at preventing adolescent gambling may have implications for the well-being of both harmed gamblers and their family and relatives (Li et al., 2021; Tulloch et al., 2021).

Future research should examine the interaction between other contextual and individual factors that could predict adolescent gambling behavior. Moreover, given the increase in online gambling in recent years (Gambling Commission, 2018), it is suggested that future research studies on gambling availability include a measure of gambling availability in both offline and online venues. Finally, future research examining the determinants of the perception of gambling availability could help to inform the design of preventative interventions aimed at reducing gambling behavior.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abdi, T. A., Ruiter, R. A., & Adal, T. A. (2015). Personal, social and environmental risk factors of problematic gambling among high school adolescents in Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9410-9

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x

Bonamis, A. E. (2019). Exploring the relationship between individual gambling behaviour and accessibility to gambling venues in New Zealand (Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology).

Botella-Guijarro, Á., Lloret-Irles, D., Segura-Heras, J. V., Cabrera-Perona, V., & Moriano, J. A. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of gambling predictors among adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9266.

Bradley, A., & James, R. J. (2020). Defining the key issues discussed by problematic gamblers on web-based forums: A data-driven approach. International Gambling Studies, 1-15https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2020.1801793

Bruun, K., Edwards, G., Lumio, M., Mäkelä, K., Pan, L., Popham, R.E., Room, R., Skog, O. -J., Sulkunen, P., Osterberg, E., Schmidt, W. (1975). Alcohol control policies in public health perspective. Helsinki: Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies.

Casey, L. M., Oei, T. P., Melville, K. M., Bourke, E., & Newcombe, P. A. (2008). Measuring self-efficacy in gambling: The gambling refusal self-efficacy questionnaire. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24(2), 229–246.

Chóliz, M., Marcos, M., & Lázaro-Mateo, J. (2021). The risk of online gambling: A study of gambling disorder prevalence rates in Spain. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(2), 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00067-4

Clark, R. (2009). Accelerating expertise with scenario-based learning: A learning blueprint. American Society for Training and Development.

Corporate Research Associates Inc. & Nova Scotia Gaming Corporation. (2006). Video lottery program changes impact analysis. Halifax, NS: Corporate Research Associates.

Escario, J. J., & Wilkinson, A. V. (2020). Exploring predictors of online gambling in a nationally representative sample of Spanish adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.002

ESPAD Group. (2020). ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. Publications Office of the European Union.

Gainsbury, S. (2012). Policy and regulatory options. Internet Gambling (pp. 27–62). Springer.

Gambling Commission (2018) Annual report. Retrieved from https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/ survey-data/Gambling-participation-in-2018-behaviour-awareness-and-attitudes.pdf.

Gavriel-Fried, B., Delfabbro, P., Ricijas, N., Hundric, D. D., & Derevensky, J. L. (2021). Cross-national comparisons of the prevalence of gambling, problem gambling in young people and the role of accessibility in higher risk gambling: A study of Australia, Canada, Croatia and Israel. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02017-7

Griffiths, M. D., & Barnes, A. (2008). Internet gambling: An online empirical study among student gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(2), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-007-9083-7

Griffiths, M., Wardle, J., Orford, J., Sproston, K., & Erens, B. (2009). Socio-demographic correlates of internet gambling: Findings from the 2007 British Gambling Prevalence Survey. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 199–202. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0196

Hanss, D., Mentzoni, R. A., Griffiths, M. D., & Pallesen, S. (2015). The impact of gambling advertising: Problem gamblers report stronger impacts on involvement, knowledge, and awareness than recreational gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000062

Hayes, A. F. (2017). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford press.

Hilbrecht, M., Baxter, D., Abbott, M., Binde, P., Clark, L., Hodgins, D. C., Manitowabi, D., Quilty, L., SpÅngberg, J., Volberg, R., Walker, D., & Williams, R. J. (2020). The conceptual framework of harmful gambling: A revised framework for understanding gambling harm. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00024

Holliday, S. (2010). Global interactive gambling universe: H2 market forecast/sector update. H2 Gambling Capital. Retrieved from http://www.h2gc.com/news.php?article=H2+Gambling+Capital+Presentations+May+2010

INE (2021). Enseñanzas no universitarias. Alumnado matriculado Curso 2019–2020. Resultados detallados. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available at: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano/estadisticas/no-universitaria/alumnado/matriculado/2019-2020-rd.html Accessed 1st Dec, 2021.

Kang, K., Ha, Y. K., & Bang, H. L. (2020). Gambling subgroups among Korean out-of-school adolescents. Child Health Nursing Research, 26(3), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2020.26.3.385

Kang, K., Ok, J. S., Kim, H., & Lee, K. S. (2019). The gambling factors related with the level of adolescent problem gambler. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122110

Karatay, G., & Gürarslan Baş, N. (2017). Effects of role-playing scenarios on the self-efficacy of students in resisting against substance addiction: A pilot study. Inquiry, 54, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958017720624

Kato, H., & Goto, R. (2018). Geographical accessibility to gambling venues and pathological gambling: An econometric analysis of pachinko parlours in Japan. International Gambling Studies, 18(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2017.1383503

King, S. M., Wasberg, S. M. H., & Wollmuth, A. K. (2020). Gambling problems, risk factors, community knowledge, and impact in a US Lao immigrant and refugee community sample. Public Health, 184, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.019

León-Jariego, J. C., Parrado-Gonzalez, A., & Ojea-Rodriguez, F. J. (2020). Behavioral intention to gamble among adolescents: Differences between gamblers and non-gamblers—Prevention recommendations. Journal of Gambling Studies, 36(2), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09904-6

Li, L. Z., Bian, J. Y., & Wang, S. (2021). Moving beyond family: Unequal burden across mental health patients’ social networks. Quality of Life Research, 1–7.

Livazović, G., & Bojčić, K. (2019). Problem gambling in adolescents: What are the psychological, social and financial consequences? BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 308. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2293-2

Lloret, D. Cabrera-Perona, V., & Núñez, R. (2018, noviembre). Early detection of gambling abuse risk among adolescents. Validation of Edgar_A Scale. IV International Congress of Clinical and Health Psychology on Children and Adolescents, Palma de Mallorca.

Lund, I. (2009). Gambling behaviour and the prevalence of gambling problems in adult EGM gamblers when EGMs are banned. A natural experiment. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9127-y

May, R. K., Whelan, J. P., Steenbergh, T. A., & Meyers, A. W. (2003). The gambling self-efficacy questionnaire: An initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19(4), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026379125116

Miller, H. E., Thomas, S. L., Robinson, P., & Daube, M. (2014). How the causes, consequences and solutions for problem gambling are reported in Australian newspapers: A qualitative content analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38(6), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12251

Miller, H. E., Thomas, S. L., Smith, K. M., & Robinson, P. (2015). Surveillance, responsibility and control: An analysis of government and industry discourses about “problem” and “responsible” gambling. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1094060

Molinaro, S., Benedetti, E., Scalese, M., Bastiani, L., Fortunato, L., Cerrai, S., Canale, N., Chomynova, P., Elekes, Z., Feijão, F., Fotiou, A., Kokkevi, A., Kraus, L., Rupšienė, L., Monshouwer, K., Nociar, A., Strizek, J., & Lazar, T. U. (2018). Prevalence of youth gambling and potential infuence of substance use and other risk factors across 33 European countries: First results from the 2015 ESPAD study. Addiction, 113(10), 1862–1873. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14275

Moore, S. M., Thomas, A. C., Kyrios, M., Bates, G., & Meredyth, D. (2011). Gambling accessibility: A scale to measure gambler preferences. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(1), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9203-3

Neal, P., Delfabbro, P. H., & O’Neill, M. (2005). Problem gambling and harm: Towards a national definition. Final report. Gambling Research Australia, Melbourne. https://www.gamblingresearch.org.au/publications/problem-gambling-and-harm-towards-national-definition. Accessed 1st Dec 2021.

Ofori Dei, S. M., Christensen, D. R., Awosoga, O., Lee, B. K., & Jackson, A. C. (2020). The effects of perceived gambling availability on problem gambling severity. Journal of Gambling Studies, 36, 1065–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09930-9

Quinn, C. A., Archibald, K., Nykiel, L., Pocuca, N., Hides, L., Allan, J., & Moloney, G. (2019). Does self-efficacy moderate the effect of gambling advertising on problem gambling behaviors? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(5), 503–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000485

Secades, R., & Villa, A. (1998). El juego patológico. Prevención, evaluación y tratamiento en la adolescencia [Pathological gambling: Prevention, assessment, and treatment in adolescence]. Madrid, Spain: Pirámide.

Slutske, W. S., Deutsch, A. R., Richmond-Rakerd, L. S., Chernyavskiy, P., Statham, D. J., & Martin, N. G. (2014). Test of a potential causal influence of earlier age of gambling initiation on gambling involvement and disorder: A multilevel discordant twin design. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(4), 1177–1189.

St-Pierre, R. A., Derevensky, J. L., Temcheff, C. E., & Gupta, R. (2015). Adolescent gambling and problem gambling: Examination of an extended theory of planned behaviour. International Gambling Studies, 15(3), 506–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2015.1079640

Stockwell, T., & Gruenewald, P. J. (2003). Controls on the physical availability of alcohol. In: Heather, N., Stockwell, T. (Eds.), The essential handbook of treatment and prevention of alcohol problems. Wiley and sons, Chichester.

Monaghan, S., Derevensky, J., & Sklar, A. (2008). Impact of gambling advertisements and marketing on children and adolescents: Policy recommendations to minimise harm. Journal of Gambling Issues, 22, 252–274. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2008.22.7

Thomas, S., Pitt, H., Bestman, A., Randle, M., McCarthy, S., & Daube, M. (2018). The determinants of gambling normalisation: causes, consequences and public health responses. Victoria, Australia: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. Retrieved from https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/the-determinants-of-gambling-normalisation-causes-consequences-and-publichealth-responses-349/. Accessed March 2021.

Törrönen, J., Samuelsson, E., & Gunnarsson, M. (2020). Online gambling venues as relational actors in addiction: Applying the actor-network approach to life stories of online gamblers. International Journal of Drug Policy, 85, 102928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102928

Tulloch, C., Browne, M., Hing, N., Rockloff, M., & Hilbrecht, M. (2021). How gambling harms the wellbeing of family and others: A review. International Gambling Studies, 1–19.

Wechsler, H., Lee, J. E., Hall, J., Wagenaar, A. C., & Lee, H. (2002). Secondhand effects of student alcohol use reported by neighbors of colleges: The role of alcohol outlets. Social Science & Medicine, 55(3), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00259-3

Wickwire, E. M., Whelan, J. P., West, R., Meyers, A., McCausland, C., & Leullen, J. (2007). Perceived availability, risks, and benefits of gambling among college students. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23(4), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-007-9057-5

Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Winfree, W. R., Meyers, A. W., & Whelan, J. P. (2013). Validation of a Spanish adaptation of the gambling self-efficacy questionnaire. International Gambling Studies, 13(2), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2013.808683

Winters, K. C., Stinchfield, R. D., & Fulkerson, J. (1993). Toward the development of an adolescent gambling problem severity scale. Journal of Gambling Studies, 9(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01019925

Wood, R. T., Williams, R. J., & Lawton, P. K. (2007). Why do Internet gamblers prefer online versus land-based venues? Some preliminary findings and implications. Journal of Gambling Issues, 20, 235–252.

Wood, R., & Williams, R. (2009). Internet gambling: Prevalence, patterns, problems and policy options. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Final Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the University of Huelva/CBUA agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

APG, FFC, and JCLJ conceived and designed the study. APG drafted the initial manuscript and conducted initial analyses. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, data analyses, writing, editing, and approval of the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Huelva (N° 2018000100001203).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

The author declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parrado-González, A., Fernández-Calderón, F. & León-Jariego, J.C. Perceived Gambling Availability and Adolescent Gambling Behavior: the Moderating Role of Self-Efficacy. Int J Ment Health Addiction 21, 2737–2750 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00749-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00749-y