Abstract

Internet technology has facilitated the use of a wide variety of different activities and applications in online contexts. Despite a large amount of research regarding these activities including online social networking, online gaming, online shopping, online sex, and online gambling, very little is known regarding online eating shows called ‘mukbang’ (i.e. a portmanteau of the South Korean words for ‘eating’ [‘meokneun’] and ‘broadcast’ [‘bangsong’] that refers to online broadcasts where individuals eat food and interact with the viewers). The present study carried out a scoping review of the academic and non-academic literature (i.e. peer-reviewed publications, academic theses, and the print media) in order to examine the psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers and consequences of mukbang watching. A total of 11 academic outputs from different disciplinary fields (mainly peer-reviewed papers) and 20 articles from national UK newspapers were identified following an extensive literature search. Results from the scoping review indicated that viewers use mukbang watching for social reasons, sexual reasons, entertainment, eating reasons, and/or as an escapist compensatory strategy. Furthermore, mukbang watching appears to have both beneficial consequences (e.g., diminishing feelings of loneliness and social isolation, constructing a virtual social community,) and non-beneficial consequences (e.g., altering food preferences, eating habits, and table manners, promoting disordered eating, potential excess, and ‘addiction’). Implications of the study and directions for future research are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The internet can be a mediating tool for individuals to engage in specific behaviours online (Griffiths 1999). Developments in internet technologies have brought a variety of online applications into individuals’ lives (e.g., gaming, gambling, sex, shopping, social networking), leading to many different forms of gratifications obtained from these activities (Montag et al. 2015). Consequently, internet use motives of individuals have become increasingly varied and specific over time to a degree that even the most particular applications (e.g., YouTube, Instagram) have been shown to harbour a variety of features that result in the compensation of unique individual needs (Balakrishnan and Griffiths 2017; Kırcaburun and Griffiths 2018).

Recent newspaper coverage has indicated that there has been a growing phenomenon of individuals using internet applications for engaging in a unique online activity, watching mukbang (McCarthy 2017). Mukbang is a portmanteau of the South Korean words ‘eating’ (‘meokneun’) and ‘broadcast’ (‘bangsong’) and refers to online eating shows where a mukbanger or broadcast jokey (the individual in the broadcast) eats large portions of food on camera while interacting with viewers (McCarthy 2017). Even though mukbang first started in South Korea a decade ago, it has now reached increasing popularity in a number of other countries and where hundreds of thousands access the internet every day in order to watch mukbang videos (Hawthorne 2019). Mukbang’s popularity greatly increased across many regions worldwide after being introduced to western countries in 2015 when a popular American YouTube broadcaster uploaded a video commenting on South Korean mukbang videos (McCarthy 2017). However, despite this rising popularity of mukbang, very little attention has been given to this phenomenon among scholars. Consequently, empirical studies are warranted to identify psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers and possible consequences of mukbang watching.

Previous studies have applied several theoretical frameworks to investigate the use of different online applications. The compensatory internet use model (CIUM) (Kardefelt-Winther 2014) is one such model that attempted to explain psychological characteristics of engaging in online activity. According to the CIUM, it is posited that individuals use the internet in order to compensate unattained offline needs via specific online activities (Kardefelt-Winther 2014). Empirical literature has documented a wide range of compensatory strategies that facilitate the use of different online activities. For instance, self-presentation, belongingness, social gratifications, recreation, and information are motives that have been associated with social media use (Chen 2015; Seidman 2013). Online gaming motivations include social reasons, escapism, competition, coping reasons, skill development, fantasy, and recreation (Ballabio et al. 2017; Demetrovics et al. 2011). Furthermore, online pornography consumers use the internet to compensate their needs for sexual arousal, physical pleasure, a sense of excitement, and avoiding uncomfortable emotions (Brown et al. 2017).

However, for a minority of users, compensating different needs via online usage can lead to negative consequences (Kardefelt-Winther 2014). According to coping style theory, maladaptive coping exacerbates negative emotions and mitigates positive emotions and wellbeing (Folkman and Lazarus 1988; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). For a minority of individuals, empirical research has identified several negative outcomes of online pornography use, social media use, online gambling, and online gaming including elevated depression, higher anxiety, increased negative mood, lower self-esteem, sleeping problems, suicide ideations, increased alcohol/substance abuse, lower social integration, and higher conduct problems (Kuss and Griffiths 2012a; Owens et al. 2012; Sherlock and Wagstaff 2019; Wenzel et al. 2009).

Despite a large amount of research concerning the reasons and consequences of the use of online activities (e.g., online social networking, online gaming, online shopping, online sex, and online gambling), very little attention has been given to mukbang watching among psychologists. Therefore, the present study aimed to scope the literature in order to identify existing publications that have empirically investigated and/or theoretically examined the mukbang phenomenon and conceptualized the psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers and possible consequences of mukbang watching.

Methods

The present study carried out a scoping review. A scoping review comprises an attempt to survey the literature on a specific topic in order to identify key concepts, available evidence, and gaps in the research with regard to the chosen topic irrespective of the source material or quality of the source (Pham et al. 2014). A scoping review was conducted because of its different facilitations including the (i) ability to examine the extent and nature of the existing research on a particular topic, (ii) opportunity to summarize and disseminate research findings, and (iii) ability to determine research gaps in the literature (Daudt et al. 2013). The methodological framework for conducting a scoping study described by Arksey and O’Makkey (2005) was used in the present study. Consequently, five stages were included: (i) identifying the research question; (ii) identifying relevant studies; (iii) study selection; (iv) charting the data; and (v) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. In line with the principles of scoping reviews (Kavanagh et al. 2005), the present paper aimed to make a preliminary assessment of the potential scope of the available research literature without attempting to control for the quality or source of the data. Sources of material used in the present review were both academic and non-academic (e.g., print media).

Research Questions

The present study conducted a scoping review to find answers to the following questions: ‘What are the psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers?’ and ‘What are the psychological consequences of mukbang watching?’

Information Sources and Inclusion Criteria

Initially, all scientific literature including published papers, conference presentations, commentaries, content analyses, critical reviews, literature reviews, case reports, dissertations, and empirical studies that have examined mukbang phenomenon was searched for. To be included in the present study, the publications had to have (i) addressed topics related to psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers and (ii) been written in English language. Several electronic databases were used for this review including, but not limited to, Academic Search Elite, PsychArticles, PsychInfo, Science Direct, and Scopus via using the research team’s Library One Search electronic search engine. Furthermore, Google Scholar was used as a secondary source search engine. A snowballing method was also used to identify relevant publications from scientific literature via examining the reference lists of found studies. In the second step, non-academic ‘grey’ literature was reviewed via examining the national newspapers in the UK (Wikipedia 2019) as information sources. The search terms used were ‘mukbang’ (and its alternative spellings such as ‘mokbang’, ‘meokbang’, and ‘mŏkpang’), and ‘eating broadcast’.

Results

Academic Literature

After scoping the academic literature, 1053 publications were identified. First, publications written in foreign language (n = 124) were removed. Second, based on the title and abstract, studies that were duplicates and/or irrelevant to the present study’s aims (n = 915) were excluded. Once irrelevant and duplicate publications were removed using manual searching, 14 records remained. Of these, and as a result of full-text examination, one Master’s thesis was removed due to its irrelevance to the present study’s aims. A further 20 non-academic articles in British newspapers were also identified (see Fig. 1). Two of the outputs were theoretical and 11 of them were empirical publications providing both theoretical discussions and empirical findings concerning the mukbang phenomenon (see Table 1). The scoping review of academic outputs showed several common themes including social use of mukbang, sexual use of mukbang, entertainment use of mukbang, escapist use of mukbang, ‘vicarious eating’ use of mukbang, and consequences of mukbang watching.

Social Use

One of the most noted aspects of the mukbang phenomenon was its role in social facilitation. Schwegler-Castañer (2018) described the cases of three female mukbangers (one Singaporean, one South Korean, and one American) and discussed mukbang from a feminist studies perspective. According to her, mukbang videos had the potential to counteract loneliness and isolation by connecting and sharing a similar interest with a virtual community. In a review study about digital commensality (i.e. the practice of eating together), Spence et al. (2019) argued how mukbang could be used to psychologically facilitate commensality in order to cope with eating alone. Their main concern was that there had been few empirical studies on how mukbang watching might affect viewers. They also questioned whether mukbang could provide similar benefits for an individual’s mental health that were related to physically dining together with others. Despite the scarcity of research on psychological predictors and consequences of mukbang phenomenon, they concluded that watching mukbang while dining could potentially provide viewers a sense of digital commensality (Spence et al. 2019), and which could foster feelings of affective connection with other individuals.

Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015) examined the interaction of South Korean culture and mukbang phenomenon by reviewing newspaper coverage concerning mukbangers. They concluded that mukbang watching enabled viewers to communicate with thousands of individuals from home while watching someone eat. Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015) argued that similar to Western citizens, South Koreans across all age groups were increasingly suffering from living alone and being lonely in single-person households, and this elevated social isolation led them to watching mukbang as a means to have eating partners and feeling emotionally connected to others.

According to Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015), the emotional connection and empathy felt towards mukbangers are also important contributors in watching mukbang. For instance, one leading mukbanger facilitated this aforementioned connection among his male audience members via eating food in army training outfits in a room decorated with different army paraphernalia (e.g., toy rifles, battle figures) that reminded viewers of nostalgic memories of their service as a soldier. Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015) also argued that mukbang provided a harmonious set-up where individuals got together as one society and associated with one another on shared interests. Positive remarks about the mukbanger and food advanced higher feelings of community and positive emotions among those who watched mukbang (Hakimey and Yazdanifard 2015).

Some academic outputs have analysed mukbang-related content (e.g., mukbangers, mukbang videos, viewer comments). Choe (2019) conducted a content analysis study analysing and reviewing 67 mukbang video clips of a male South Korean mukbanger. She examined the mukbang phenomenon in South Korean culture from a sociolinguistic perspective. Choe (2019) emphasized that eating together was considered a crucial aspect of South Korean culture that individuals go beyond sharing a table to as far as eating from the same bowls. According to Choe (2019), one important facilitation of mukbang was the fulfilment of an aspiration to eat with a company. Choe (2019) theorized that as isolated eating was increasingly commonplace in many regions of the world as well as in South Korea, mukbang provided a sense of social unity for those physically eating alone. Watching mukbang made viewers feel emotionally connected as if they were dining with someone (Choe 2019). Moreover, mukbang watching enabled a sense of co-presence among viewers via commenting with each other to eat food together while watching their favourite mukbanger (Choe 2019). She also emphasized the role of mukbangers in providing a sense of collaborative eating via engaging in different eating actions participated by viewers, consequently resulting in an elevated connection between the mukbanger and viewers. According to Choe (2019), through food and eating, mukbang watchers were associated to each other by a feeling of co-presence that overcame physical distance.

In another content analysis study, Donnar (2017) focused on the cases of four South Korean mukbangers and analysed their content of their videos to discuss the concept of ‘food porn’ among most attractive female mukbangers. Donnar emphasized that watching mukbang can facilitate subjective closeness and a sense of community and help overcome loneliness and alienation for those who live alone and seek companionship and a dinner partner. Hong and Park (2018) analysed South Korean mukbang videos broadcast on Afreeca TV in order to discuss mukbang’s features and implications for contemporary South Korean society. They initially went through 30 active mukbanger profiles. They argued that viewers watched mukbang as a ‘meal mate’ (p. 118) in order to avoid eating alone and alleviate loneliness. Individuals usually watched mukbang around mealtime or late-night snack time. Hong and Park (2018) theorized that mukbang fulfilled physical and sentimental hunger of single-person households by providing simple recipes or tips for eating alone and by creating a sense of social bonding and belongingness with mukbangers and other viewers.

Woo (2018) conducted a content analysis study to examine South Korean mukbang from a digital communication and advertising perspective. Her research suggested that mukbang’s popularity in South Korea was mostly associated with viewers’ attempt to overcome their loneliness via simulating the act of eating with friends or family by making connections with mukbangers. Gillespie (2019) analysed 36 mukbang videos from a total of nine female mukbangers from USA, Canada, and South Korea who had a large number of subscribers and used rhetorical criticism from a feminist approach to argue that mukbang viewers reacted to mukbang videos in order to find out mukbang’s effect on hegemonic thinness culture. Gillespie (2019) claimed that mukbang viewers enjoyed seeing women eating messily, being noisy, demonstrating pleasure, and eating too much even though they saw these behaviours as transgressive acts. According to Gillespie (2019), female viewers were particularly drawn to mukbang because they feel connected to other females who were eating very large portions of unhealthy food messily and open to public.

Bruno and Chung (2017) carried out a case study where they interviewed three South Korean mukbangers and a shop owner to examine the factors that draw viewers to watching mukbang. They also collected data from viewers’ chat logs, images of mukbangers’ personal broadcasting homepages, and information found on the AfreecaTV homepage. Bruno and Chung (2017) argued that the main beneficiaries of vicarious pleasures provided by mukbang were individuals who eat alone but desire a social presence. They claimed that one possible motivation of mukbang viewers was that they were forming a kind of viewing community via interacting and communicating with each other on a common interest, which promoted elevated feelings of pleasure and belonging. Participants perceived mukbang as a free space where they could share a vicarious pleasure.

Bruno and Chung (2017) theorized that even though all viewers did not know one another, they could feel the presence of other viewers through the chat screen or comments and likes. The chat screen influenced the quality and popularity of mukbang and the emotional mood of the viewers. Live chat during and after eating could sometimes be more important than eating itself for some viewers. Content analysis revealed that approximately 10% of viewers stayed logged in when the eating had finished to chat about different topics relating to their daily lives. Bruno and Chung (2017) pointed out that these chat interactions developed empathic relationships between mukbanger and viewers as well as between viewers. Viewers also felt attracted to mukbangers’ effort to create a social presence in mukbang videos via showing their personal side, reacting to viewers’ comments, pausing eating, and thanking the viewers who sent gifts. Similarly, Song (2018) content analysed the chats among the viewers and South Korean mukbangers and argued that viewers grew fond of and felt connected to the mukbangers as a result of live interaction.

However, Bruno and Chung (2017) emphasized that social presence and interaction among viewers might also become uncontrolled. For instance, some viewers had become so connected to each other that they started using specific mukbang channels just to communicate with each other (Bruno and Chung 2017). Some viewers insulted mukbangers for their appearance and the amount of food they consumed (Song 2018). Others spread rumours about the mukbangers they watched in order to damage their reputation and relationships with others. Bruno and Chung (2017) noted that even though most viewers commented with positive and constructive remarks, some insulted or criticized mukbangers or the food. These were important because positive or negative audience reactions affected other audiences’ reactions to and interactions with the mukbang content.

Sexual Use

Another aspect of mukbang was its sexual use. Schwegler-Castañer (2018) argued that mukbang might be comprehended as fetishizing women eating. She emphasized the self-portrayal of women eating huge amounts of harmful food showing the ‘shameful appetite’ (p. 784) that women conceal which was susceptible to sexualizing women’s bodies. She also pointed out the potential sexual objectification of female body and reinforcement of the normative values regarding thinness and consumerism.

Donnar (2017) concluded that slim and attractive female mukbangers were usually surrounded by overweight male fans and viewers. According to Donnar, mukbang had a sexual aspect with its facilitation of a sexualized gaze to attractive mukbangers while they were in a somewhat private and vulnerable state (i.e. eating). It was concluded that viewers reacted with divergent feelings to these sexual and eating sensations provided by mukbang videos, including pleasure, desire, longing, envy, horror, disgust, and shame.

Only a few cross-sectional studies have examined mukbang phenomenon. In a self-report cross-cultural study, Pereira et al. (2019) surveyed 114 Asian and 129 Caucasian participants to examine why online consumers watch mukbang. Path analysis showed that host attractiveness was positively related to attitudes towards mukbang in both samples. According to Pereira et al. (2019), even though the study only examined physical attractiveness of the mukbanger, there were well-known mukbangers with high sociability and likeability (rather than physical beauty) who gathered large numbers of viewers. Nevertheless, this study emphasized the importance of physical attraction towards mukbangers among viewers. One of the limitations of this study was that the sample comprised both those who watched mukbang and those who did not know anything about mukbang (Pereira et al. 2019).

Entertainment Use

Individuals who watch mukbang also seek entertainment. Choe (2019) concluded that viewers extracted different gratifications from watching mukbangs, including the enjoyment of the eating sounds that the mukbanger made (e.g., slurping, chewing). Woo (2018) suggested that viewers obtained pleasure from different sensations including listening to eating and cooking sounds such as chewing noises, preparing foods, and sounds from opening up food packages (Woo 2018). Woo claimed that these sounds provided an autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) experience by causing static-like, tingling sensations along the skin and triggering a sense of happiness and relief. Woo argued that these sounds increased viewers’ feeling of telepresence.

Schwegler-Castañer (2018) theorized that the edited non-simultaneous interaction between the viewers and mukbangers also provided an alluring viewing experience for the audience. However, for others, mukbang could become an experience of ASMR where the viewers were more keen on the sounds produced by the act of eating than the consumption itself. She also noted the potential entertainment gratifications of mukbang that help viewers achieve sensory satisfaction and amusement through sharing others’ eating experiences.

Escapist Use

Some studies have theorized that viewers use mukbang watching as an escape from reality. Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015) concluded that individuals watched mukbang for different motivations and reasons. Some of the viewers wanted to observe someone eat different foods because of their inability to access a wide variety of different foods (e.g., because they were hospital patients). Another reason for South Koreans were drawn to mukbang was to alleviate stress. Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015) speculated that South Koreans alleviated their stress from their fast-paced and hypercompetitive way of life by watching someone eat. According to Bruno and Chung (2017), viewers tried to escape from a sense of guilt and stress of being fat by watching mukbang (Bruno and Chung 2017). In addition, adolescents who were bored or hungry late in the evening and youngsters who would like to order food but could not because their parents were at home, enjoyed mukbang as an escape from unpleasant reality.

Eating Use

One of the key compensations provided by mukbang watching was vicarious eating. Hakimey and Yazdanifard (2015) emphasized that individuals watched mukbang to have the experience of eating vicariously through mukbangers because they were on diets. Choe (2019) also posited this theory by arguing that viewers extracted different gratifications from watching mukbangs, including having excitement for the eaten food and satisfaction of watching mukbangers conspicuously consume the food they crave while they were on a diet. Choe (2019) further asserted that mukbangers helped satisfy food cravings of the viewers by giving them a vicarious pleasure of eating. According to her, viewers had a vicarious satisfaction of eating from mukbang via obtaining visual and audio stimulation.

As a result of her analyses, Donnar (2017) argued that, considering the mouth-watering scenery of the act of eating (e.g., ‘orgasmic first bite’ [p. 123] and continuous pleasure cues given by mukbangers throughout the video), mukbang was akin to ‘food porn’ rather than food images or food-related television shows. Donnar claimed that interactions between mukbangers and fans (e.g., responding to fan requests as they eat, talking while eating) were making mukbang similar to webcam porn. Some dieting female viewers watched mukbang as a satisfaction of their fetishistic desires for vicarious consumption while avoiding actual eating. Bruno (2016) analysed several South Korean television shows that involved eating. According to her, when watching someone eat on camera, viewers felt as if they were eating and they could ‘almost taste the food and the consequent feeling of satiety’ (p. 159).

Gillespie (2019) argued that magical eating fantasy (i.e., the idea of eating as much as desired without suffering the consequences) was one of the most important motivations that drove individuals to watch mukbang. According to Gillespie (2019), watching mukbang provided viewers satisfaction via the sensation of binge eating themselves. Some viewers used mukbangers as a proxy for eating by creating a reality where they were becoming the mukbangers by proxy as a way of fulfilling their fantasies of eating (Gillespie 2019).

Furthermore, Bruno and Chung (2017) concluded that some viewers did not care about the mukbangers and saw them as prostitutes who eat/consume whatever viewers demand in exchange for money. They theorized that the main beneficiaries of vicarious pleasures provided by mukbang were individuals who were on a diet. They also argued that mukbang was a complex phenomenon that shared some common features with food porn and food voyeurism. They claimed that viewers got vicarious satisfaction from watching the food being eaten, in which part of the viewers’ vicarious pleasure came from the eating performance of the mukbanger. They also theorized that it was very important for some of the viewers that mukbanger ate the food they selected and desired. Viewers’ vicarious pleasure demanded a large quantity of unhealthy food to be consumed. Making loud sounds while eating and showing the food in an appetizing way on camera attracted the viewers, especially the ones who were on a diet. Most of these viewers watched to see the food not to see mukbanger’s face. Viewers wanted the mukbanger to eat it with hearty and keen enjoyment to satisfy themselves.

In an American study on how mukbang could affect viewers, Tu and Fishbach (2017) conducted several experiments that examined the vicarious satiation phenomenon by observing how watching others consume specific foods affected viewers’ desires towards those particular foods. The first experiment indicated that viewers who watched someone else eat a pizza desired less pizza than before watching the video. The second experiment demonstrated that viewers who watched someone eat M&Ms (a brand of candy) postponed consumption of M&Ms and chose to eat another product after watching the video. The third experiment showed that this lessening effect was present only among those observers who watched someone that shared their political view eats the candy (Tu and Fishbach 2017). As a result of the three experiments, Tu and Fishbach (2017) concluded that individuals could experience vicarious satiation when they observed others’ consumption as their own.

Consequences of Mukbang Watching

Papers identified in the present scoping review also found that mukbang watching can lead to potential desired and undesired consequences for the viewers. For instance, Spence et al. (2019) theorized that one of the potentially harmful aspects of mukbang might be that individuals’ consumption norms could easily be affected by others’ consumption. They argued that individuals were susceptible to consuming more than they normally would if they see another individual consuming a large high-calorie meal because of social comparison or mimicry. They theorized that watching mukbang videos where mukbangers eat very large portions of food might easily leads mukbang viewers to higher than normal consumption. Donnar (2017) claimed that mukbang could promote problematic eating and food practices among both mukbangers and viewers for those who were already experiencing different eating problems. She claimed the mukbang phenomenon damaged South Koreans’ relationship with food and hunger by normalizing conspicuous consumption and consumption of different foods that were not historically welcome in South Korea such as western fast food. She argued that elevated consumption promoted by mukbang could further contribute to the problems that South Korean society was already going through including growing obesity, food disorders, and real-life social isolation (Donnar 2017).

Hong and Park (2018) identified and discussed different effects of mukbang watching upon South Korean viewers. They claimed mukbang videos affected viewers’ food selection in a way that the food consumed in mukbangs (e.g., fast food, junk food) were sometimes different from South Korea’s traditional foods and mukbangers influenced viewers’ perceptions of these foods by urging viewers to enjoy instant meals, frozen food, and poor nourishing foods that were spicy and oily with a high caloric content. Second, Hong and Park claimed that mukbang videos affected viewers’ table manners because mukbangers usually exhibit bad eating and table manners by snatching or scooping food, and eating it up carelessly while conversing with their viewers with their mouths full. They also emphasized their eating sounds in order to stimulate viewers’ senses in which all these behaviours contributed to disruption of traditional eating manners and habits that viewers had.

According to Hong and Park, mukbang videos also affect viewers’ perception of food consumption and thinness because mukbangers who were very thin and slim consumed very large portions of food and did not gain weight. This manipulated viewers’ psychology to question their efforts to stay fit. Furthermore, Bruno and Chung (2017) emphasized that mukbang influenced social and cultural food behaviour by altering viewers’ food and brand preferences because mukbangers could make viewers salivate over the meal being eaten by the mukbanger. The authors claimed this influence could lead to decrease in homemade food production and an increase in fast food consumption.

Newspaper Literature

As noted earlier, scoping reviews do not discriminate between the source of the material or the quality of the source material. As there are so few academic studies examining mukbang, a review of print media was also undertaken by searching for mukbang stories in national UK newspapers (the country where the present authors are based). Following this search, 858 records were identified. Once duplicate and irrelevant articles had been removed using manual searching, 24 stories remained. Of these, 20 articles discussed mukbang and were relevant to the study’s aims. These articles proposed some different aspects concerning the mukbang phenomenon. You (2018) focused on Chinese mukbangers who ate different shapes and colours of ice in front of the camera. According to You, viewers’ attention could be drawn via demonstrating extreme behaviours. For instance, the Chinese government banned seductive banana eating broadcasts in order to decrease what they perceived as inappropriate and erotic online content. Hicks (2019) reported a Chinese male mukbanger who was known to eat weird and repulsive things in order to attract more viewers (e.g., mealworms, centipedes, geckos). He had already 15,000 followers watching his live streams in a social media platform called DouYu (Hicks 2019).

In another article, McFadyen (2015) reported that 5.5 million viewers had watched a mukbang video in which a South Korean female mukbanger sucked on a raw chicken. McFadyen pointed out that viewers wanted to watch the mukbanger’s other bizarre on-camera behaviours (e.g., making the chicken dance, cracking eggs on her forehead and mixing them with her bare hands). Boyd (2019) reported a story about a female mukbanger who tried to eat a newly discovered penis-shaped clam while it was alive in one of her eating broadcasts. Ritschel (2019) reported that thousands of viewers had watched a female Chinese mukbanger who attempted to eat a live octopus on camera. Finally, Gander (2016) reported the cases of viewers who were interested in watching videos that involved a mukbanger eating 10,000 calories.

In addition to bizarre and extreme mukbang behaviours, some newspaper articles have reported stories about different uses of mukbang watching among viewers. According to these stories, one of the prominent motivations of mukbang was its social use. Moran (2019) reported on how mukbang had become popular in South Korea as well as other countries including Australia and UK via giving examples of famous mukbangers from these countries. According to Jeff Yang, an Asian-American cultural critic, mukbang’s popularity was related to the increasing isolation of modern life because mukbang provided social settings to the viewers where they can interact with mukbangers. Lavelle (2018) discussed mukbang watching from a loneliness perspective by drawing attention to the growing number of single-person households in the UK. Lavelle interviewed two individuals (Alice Stride, a spokeswoman for the Campaign to End Loneliness, and Ben Edwards, self-confidence expert and relationship coach) and concluded that mukbang might bring viewers who have been living alone for a long time great comfort.

Greatrex (2016) interviewed a British mukbanger about eating and mukbang viewers. According to this mukbanger, who was also watching other individual’s mukbang videos, mukbang helped lonely individuals feel like they were eating with someone else (Greatrex 2016). Bloom (2013) published an article about mukbang by making reference to a South Korean female mukbanger. Here, mukbang helped make eating alone a little less miserable. Malm (2014) carried out an informal content analysis on videos of a female mukbanger from South Korea and her comments about mukbang videos and viewers. One of the main motivations given for mukbang watching was to alleviate loneliness by getting a sense of community when eating.

Stanton (2015) interviewed a young South Korean mukbanger and examined his videos. According to her, the popularity of mukbang phenomenon was that many South Koreans live alone and gives strong social value to eating. The interaction with the mukbangers in comments and live chats was a factor that drew viewers to mukbang. It was claimed that some viewers went so far as to prefer dining in their bedrooms watching their favourite mukbangers instead of eating with their parents. Bryant (2016) examined mukbang phenomenon from both a mukbanger and viewer perspective by examining mukbang videos and comments. It was reported that hundreds of thousands of Americans connected with other lone diners from their home by watching mukbang videos where an individual binge eats junk food in front of the camera.

Tran (2019) emphasized that the mukbang phenomenon was helping viewers alleviate social isolation that arise from living, cooking, and eating alone. An Associated Press (2019) article featured a story about mukbang viewers and mukbangers. It noted that eating was a social activity that connects individuals through meals. According to the story, viewers were drawn to the intimate social environment created by mukbangers by chatting while eating.

According to the British print media, another important aspect of mukbang is that individuals can vicariously eat by watching mukbang. In fact, one of the main motivations for mukbang watching was the vicarious pleasure of eating (Malm 2014). According to Bloom (2013), mukbang can be referred to as ‘dinner porn’ where mukbangers gorge on food for money. Pettit (2019) reported how watching mukbang influenced viewers by quoting viewers’ thoughts about mukbang. According to Pettit, viewers ate via the mukbanger by fantasizing about the food while watching mukbang. Furthermore, Pettit emphasized that specific preference of food played a crucial role in deciding which mukbang videos to watch. An article by the Associated Press (2019) on mukbang emphasized that viewers who were on a diet watched mukbang to gain a virtual satisfaction whenever they felt like eating junk food. It was also mentioned that some mukbangers avoided speaking in their videos which drew focus to the crunching and slurping sounds in order to give viewers more pleasure. Bryant (2016) pointed out that viewers hated mukbang videos if the mukbanger was not enjoying the food and did not finish all the food.

Grant (2015) examined mukbang videos and mukbangers’ interviews to gain understanding of the mukbang phenomenon and how it affected viewers. She concluded that viewers benefited from watching mukbang by satisfying themselves by eating vicariously through mukbangers. According to a British mukbanger, who was also watching other individuals’ mukbang videos, mukbang helped those who were on a diet to have vicarious satisfaction of eating and those who had eating disorders (Greatrex 2016).

The extant newspaper articles identified that mukbang was also being watched for entertainment and escape from reality. For instance, according to You (2018), millions of Chinese viewers watched these videos for the pleasure of hearing the crunching sound. Mukbang videos apparently helped viewers relieve stress and to have pleasure and happiness (Pettit 2019). The Associated Press (2019) article emphasized that watching others eat with so much enjoyment was fun, soothing, and an escape from reality. Tran (2019) also argued that the viewers used food and mukbang as an escape from real life.

Despite a number of academic papers on the sexual use of mukbang, there was only one newspaper article argued that some individuals used mukbang for sexual motivations. Sanghani (2014) focused on the sexual side of mukbang by examining mukbangers and their videos. It was reported that some men paid good money to watch ‘PG-rated dinner porn shows’ where slim young women ate an incredible amount of food for money. Sanghani argued that most of the viewers of attractive female mukbangers were men and this was because they were more interested in the women who ate the food than the food itself. According to Sanghani, mukbang was unhealthy because men paid to watch women and it was increasing the obsession with women’s bodies.

Regarding the negative consequences of mukbang watching, Park (2018) reported that South Korea’s government was planning a crackdown on mukbang videos in order to inhibit rising obesity rates. According to Park, the obesity rate in South Korea had risen from 31.7% in 2007 to 34.8% in 2016. The article pointed out that the government was going to develop guidelines for mukbang videos to improve eating behaviour and to monitor these shows as part of a wider anti-obesity programme. Park reported mixed reactions to government’s decision on mukbang. Mukbangers opposed this plan because they believed these measures would destroy individuals’ happiness while making little difference to individuals’ health. On the other hand, after witnessing their children challenging themselves to eat as much as the mukbang broadcaster, some parents who have young children have defended government’s plan because they believed mukbang could negatively influence teenagers (Park 2018). Another article supported these concerns by arguing that watching mukbang might be dangerous especially for younger viewers through modelling bad behaviour (e.g., binge eating) and perceiving it socially acceptable (Associated Press 2019).

Shipman (2019) drew attention to possible dangers and detrimental effects of mukbang watching by sharing quotes from interviews of two health experts (Uxshely Chotai, founder of the Food Psychology Clinic, UK, and Dr. Naveed Sattar, Professor of Metabolic Medicine at the University of Glasgow, UK). According to these authorities, glorifying binge eating such as mukbang was similar to binge drinking and promoted the idea that bingeing on food was something to be proud of. Shipman mentioned a British mukbanger (Adam Moran) who has devoured huge quantities of food in his videos that was being watched by millions of individuals. In one video, he ate more than 10,000 calories-worth of Lidl products in one sitting. The article reported that, according to another health expert, since individuals eat with their eyes, seeing someone bingeing on these unhealthy foods could trigger a response in the viewers because it might cause viewers perceive bingeing as a normal behaviour. Malm (2014) claimed that mukbang watching could even turn into an addictive behaviour for lonely individuals because they could communicate with thousands of people at home via mukbang. Obtaining social gratifications and compensating unattained offline social needs using a specific online activity could promote addictive use of that activity among a small minority (Kardefelt-Winther 2014).

Discussion

The present review is a first attempt to scope the literature from the lens of psychology and associated disciplines and present information on what has been theorized and discussed concerning the psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers and possible consequences of mukbang watching. One of the most important aspects of mukbang viewing was that individuals appeared to use mukbang to compensate for their unattained real-life social needs. Almost all existing theoretical studies argued that viewers obtained social gratifications from mukbang watching. This was mainly lonely individuals using mukbang to alleviate their social isolation by interacting with a virtual community of a shared interest and developing higher feelings of belongingness. This is in line with the existing literature regarding other online activities which suggest that individuals engage in online activities which facilitate social interaction (Stafford et al. 2004). For instance, individuals use social media sites to maintain their existing social relationships, meeting new individuals, and socializing (Horzum 2016).

Online gaming platforms provide the opportunity to create strong friendships and emotional relationships because players have the ability to express themselves in ways they might not feel comfortable doing in real life (Cole and Griffiths 2007). Online gambling has also been found to be affected by social facilitation whereby feeling others’ presence while gambling increased gamblers’ arousal (Cole et al. 2011). Furthermore, some studies emphasize the prominent role of mukbanger–viewer connection on mukbang watching. The interaction and emotional relationship established between the mukbanger and viewer appears to facilitate viewers to watch mukbang for social compensation. This is also in line with previous studies showing that emotional connection between the broadcaster and viewers make online videos electronic forms of intimacy that allows broadcasters to create richer social relationships with their audience (Liu et al. 2013; Rosen 2012).

Another aspect of mukbang watching was its alleged sexual uses. Mukbang watching was theorized to sexualize women’s bodies in a way that viewers were more focused on the mukbanger than the food being eaten (Donnar 2017; Schwegler-Castañer 2018). One of the very few cross-cultural studies regarding mukbang phenomenon found that physical attractiveness of the mukbanger was positively related to viewers’ attitude towards mukbang (Pereira et al. 2019). This relationship may indicate that mukbang has the potential to be a sexual activity for some viewers because sexual arousal is moderately correlated with the watched person’s physical attractiveness among both men and women (Sigre-Leirós et al. 2016). Although, existing studies mostly mentioned sexualization of female bodies, male mukbangers could also have been watched for sexual gratification. Extant literature supports the notion that both men and women engage in unusual sexual fantasies (Joyal et al. 2015). In fact, some individuals may combine sexual and eating gratifications and form a unique type of fantasy (i.e., feederism). In one study, men and women from general population who were shown neutral and feeding still images while listening to audio recordings of neutral and feeding stories subjectively rated feeding stimuli as more sexually arousing than neutral stimuli (Terry et al. 2012).

Additionally, a minority of both men and women from homosexual and heterosexual communities have reported gaining weight for sexual pleasure of their partners (Prohaska 2013). Those who gain sexual arousal from making their partners obese (i.e. ‘feeders’) may compensate this particular need via fantasizing about feeding someone to a state of morbid obesity that would result in immobility (Prohaska 2014). From this point of view, mukbang could also facilitate sexual compensation for feeders (i.e., person who feeds the feedee for sexual arousal) through presenting excessive eating on camera. In fact, feeders could go as far as viewing live mukbang shows where they can instruct mukbangers what and how much to eat, simulating the act of feeding someone via mukbang. Nevertheless, given that men and women equally fantasize about fetishes (Yule et al. 2017), watching others eat may serve as a sexual fetish for some individuals.

Another aspect of mukbang watching was its entertainment uses. The reviewed papers and articles emphasized that the sounds produced during mukbang may provide an autonomous sensory meridian response experience for some of the viewers that may lead to happiness and relief and have entertainment value (Choe 2019; Pettit 2019; Woo 2018). In this scenario, viewers become more interested in the sounds produced by the act of eating than the consumption itself (Schwegler-Castañer 2018). This observation that mukbang is being watched for entertainment purposes concurs with the studies from other online activity use literature. For instance, individuals engaged in social media use for entertainment purposes (Horzum 2016). Similarly, the online gaming literature has identified recreation as one of the motives that drives individuals to engage gaming (Demetrovics et al. 2011). Some youngsters consider pornography watching as entertaining and watch pornography for entertainment in order to cope with their boredom (Rothman et al. 2015). Mukbang also harbours entertaining elements with different mukbangers who demonstrate a variety of different behaviours. For instance, some mukbangers can entertain in their videos by giving themselves food challenges (e.g., finishing a specific amount of food in a very short period of time), while others may entertain their viewers by engaging in bizarre and unpredictable behaviours, showing odd and extreme eating styles (Hong and Park 2018).

Another aspect of mukbang watching was its use as an escape from reality. The extant literature has theorized that individuals with a desire to escape and watch mukbang videos include those who (i) were hospital patients, (ii) have fast-paced and hyper competitive ways of life, (iii) have a sense of guilt and stress about being fat, and/or (iv) are bored (Bruno and Chung 2017; Hakimey and Yazdanifard 2015). This is in line with the notion that one of the fundamental functions of online activities is their uses as an escape from reality to deal with unpleasant situations (Bessiere et al. 2008). For instance, adults spend excessive time on online gaming to escape from negative emotions such as nervousness, sadness, and anger (Kim et al. 2017a, b). College students have used social media sites (e.g., Facebook) to get away from real-world worries and problems (Kwon et al. 2013). Escape serves as the central reason for gambling even though it does not solve gamblers’ long-term problems (Wood and Griffiths 2007). Mukbang watching can also provide viewers the sought after escape mechanism from real world with its different social, sexual, and entertainment features, especially those videos where the mukbanger talks and interacts about their daily life, and which might detract viewers from their own real-life problems and unpleasant reality (Hong and Park 2018).

Another important aspect of mukbang watching is its use as a form of vicarious eating. Both academic papers and newspaper articles have theorized that some viewers who are on diets, who love food, and who want to obtain satisfaction from watching the consumption of a wide range of different food watch mukbang videos (Bruno and Chung 2017; Donnar 2017; Hakimey and Yazdanifard 2015). Watching mukbang appears to help such individuals satisfy food cravings, experience the feeling of binge eating themselves, and have a vicarious satiation via visual and audio stimulation (Choe 2019; Gillespie 2019). This is in line with the extant literature. For instance, viewers have been reported to achieve vicarious satisfaction from viewing fetish-themed pornography movies (Brennan 2017). Vicarious viewing serves as a compensation of acts that an individual would never perform in real life and/or as a fulfilment of known experiences regarding the watched act via triggering a memory (Brennan 2017). Similarly, gaming has also been reported to be preferred as a leisure activity because it provides vicarious satisfaction of making the impossible appear possible (Lee et al. 2016). Moreover, feeling vicarious satisfaction is an important motive in watching reality television programmes (Kim et al. 2017a). Consequently, the review of the existing literature suggests that mukbang watching is another online activity that could be used to fulfil virtual satisfaction and compensation.

Several studies have theorized that mukbang watching might have negative consequences for the viewers including (i) increased consumption of food because of social comparison or mimicry; (ii) alteration of viewers’ perception of food consumption and thinness, eating, health, table manners, and eating manners because of modelling of bad behaviours; and (iii) obesity and different eating disorders because of glorifying binge eating (Bruno and Chung 2017; Donnar 2017; Hong and Park 2018; Park 2018; Shipman 2019; Spence et al. 2019). On the other hand, mukbang watching might promote positive effects for viewers including alleviation of social isolation via creating a sense of belongingness to a community, subjective closeness for those who seek companionship and a dinner partner, and fulfilment of physical and sentimental hunger for those who are on a diet and/or live in single-person households (Donnar 2017; Hong and Park 2018).

These theoretical assumptions on potential consequences of mukbang found in the present review concur with the existing studies that have investigated consequences of other online activities. For instance, in a systematic review of the effects of online gaming, game players were reported to experience enjoyment, feeling of achievement, friendship, and a sense of community as a result of gaming (Sublette and Mullan 2012). Gambling has been positively related to undesired interpersonal, psychosocial, and financial consequences among adolescents (Ricijas et al. 2016). Some of the negative consequences of internet pornography consumption were diminishing sexual interest towards potential real-life partners, having an abnormal sexual response, decreased social integration, and elevated conduct problems (Owens et al. 2012; Pizzol et al. 2016; Rothman et al. 2015).

Even though several studies have addressed a range of positive and negative consequences of mukbang watching, there was only one newspaper article that argued that mukbang watching could turn into a problematic (i.e. addictive) behaviour for some of its users due to its social facilitation features. Indeed, obtaining social gratifications and compensating unattained offline social needs using a specific online activity could promote addictive use of that activity (Kardefelt-Winther 2014). For instance, meeting new individuals and socializing via social media sites has been positively associated with problematic social media use (Kircaburun et al. 2018). Those who formed virtual friendships and relationships in gaming platforms have higher rates of online gaming addiction than those who did not (Kuss and Griffiths 2012b). Similarly, both forming intimate connections with mukbangers and constructing social relationships with other mukbang viewers might promote repeated use of mukbang videos for social gratifications and, in turn, lead to problematic mukbang watching.

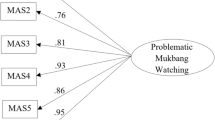

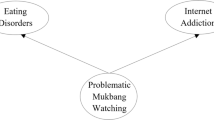

Although the reviewed publications did not directly discuss or theorize about addictive mukbang watching, in addition to social uses of mukbang, there are several gratifications obtained from mukbang watching (e.g., sexual, entertainment, escapist, and vicarious eating) that could turn normal mukbang watching into problematic mukbang watching. For instance, those individuals who perceive mukbang as a sexual fantasy could become problematic mukbang viewers because fantasizing motives are strong predictors of addictive use of online sexual activities (Wéry and Billieux 2016). Using social media for entertainment has been positively associated with problematic social media use (Kircaburun et al. 2018), which may indicate that those who can entertain themselves via watching mukbang could become problematic mukbang viewers. Escape is one of the key motivations that can turn some non-problematic activities such as gambling, gaming, and pornography use into problematic behaviours in attempts to create positive mood modification (Király et al. 2015; Kor et al. 2014; Wood and Griffiths 2007), indicating that those who successfully escape their unpleasant reality via watching mukbang could become problematic mukbang viewers. Finally, those who frequently diet and have different eating disorders may also become excessive mukbang watchers in an attempt to compensate actual eating via having the satisfaction of vicarious pleasure of eating by watching others binge eat.

Limitations and Conclusions

Thorough and transparent mapping methods of evidence found in a specific area are key strengths of scoping studies. The technical challenges involving time and the dynamic nature of the research area being investigated should be taken into account (Davis et al. 2009). From this point of view, the first limitation of the present scoping study was that some of the data were collected from newspaper articles. This limitation raises concerns regarding the quality of data collected. Second, some of the studies identified and reviewed in the present study were purely theoretical and not based on anything empirical. This reliance on theoretical arguments makes some of the discussions in the review somewhat speculative.

Nevertheless, the present scoping study is the first to review the extant literature theoretically discussing or empirically examining the psychological characteristics of mukbang viewers and consequences of mukbang watching from a psychological (and related disciplines) perspective. Even though individuals have been watching mukbang for over a decade, very little is known about this behaviour. Consequently, the present review contributes to very scarce literature and appears to indicate that mukbang viewers are those who seek social, sexual, entertainment, escapist, and/or eating compensations. Furthermore, mukbang watching may promote both positive consequences (e.g., alleviation of loneliness and social isolation) and negative consequences (e.g., disordered eating and problematic mukbang watching). Future studies should empirically examine the theoretical assumptions posited in the present review. Increasing the knowledge of this phenomenon may be important in minimizing its negative consequences. Based on the present review’s findings, problematic use of mukbang watching might facilitate symptoms of problematic sexual behaviours, internet addiction, and eating disorders. From this perspective, successful treatment strategies used to reduce these problems may also be used to cope with problematic mukbang watching. For instance, one study using a positive psychology intervention reported a decrease on the internet addiction rate of 71% in an experiment group compared to control group (Khazaei et al. 2017). Furthermore, specific forms of cognitive–behavioural therapy have been effective for several eating disorder presentations both in the short-term and long-term (Brownley et al. 2016). Similarly, group cognitive–behavioural therapy that has been successfully used to reduce compulsive sexual behaviours (Sadiza et al. 2011) could perhaps also be used for problematic mukbang watching.

References

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32.

Associated Press. (2019). Meet South Korea’s binge eating YouTube stars: Thousands watch videos of young men and women consuming colossal amounts of food as bizarre ‘mukbang’ trend hits the U.S. Daily Mail, October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7534875/Binge-eating-videos-big-audience-weight-loss.html.

Balakrishnan, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6, 364–377.

Ballabio, M., Griffiths, M. D., Urbán, R., Quartiroli, A., Demetrovics, Z., & Király, O. (2017). Do gaming motives mediate between psychiatric symptoms and problematic gaming? An empirical survey study. Addiction Research and Theory, 25, 397–408.

Bessiere, K., Kiesler, S., Kraut, R., & Boneva, B. S. (2008). Effects of internet use and social resources on changes in depression. Information, Community & Society, 11, 47–70.

Bloom, D. (2013). South Korea ‘dinner porn’ craze sweeps internet as people live-stream themselves gorging on food... and get paid for it, Daily Mail, December 21, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2527235/South-Korea-dinner-porn-craze-sweeps-internet-people-live-stream-gorging-food-paid-it.html.

Boyd, M. (2019). Woman tastes bizarre newly discovered penis-shaped clam and her reaction is hilarious. Daily Mirror, May 17, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/weird-news/woman-eats-newly-discovered-phallic-16158634.

Brennan, J. (2017). Public-sex: viewer discourse on Deerborn’s ‘homemade’ gay porn. Psychology & Sexuality, 8, 55–68.

Brown, C. C., Durtschi, J. A., Carroll, J. S., & Willoughby, B. J. (2017). Understanding and predicting classes of college students who use pornography. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 114–121.

Brownley, K. A., Berkman, N. D., Peat, C. M., Lohr, K. N., Cullen, K. E., Bann, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2016). Binge-eating disorder in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165, 409–420.

Bruno, A. (2016). Food as object and subject in Korean media. Korean Cultural Studies, 31, 131–165.

Bruno, A. L., & Chung, S. (2017). Mŏkpang: Pay me and I’ll show you how much I can eat for your pleasure. Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema, 9, 155–171.

Bryant, M. (2016). Who said that dinner for one had to be lonely! Men and women share videos of themselves binge eating online—to the delight of thousands—as bizarre South Korean ‘mukbang’ trend hits US. Daily Mail, November 8, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-3914642/Who-said-dinner-one-lonely-Men-women-share-videos-binge-eating-online-delight-THOUSANDS-bizarre-South-Korean-mukbang-trend-hits-US.html.

Chen, G. M. (2015). Why do women bloggers use social media? Recreation and information motivations outweigh engagement motivations. New Media & Society, 17, 24–40.

Choe, H. (2019). Eating together multimodally: Collaborative eating in mukbang, a Korean livestream of eating. Language in Society, 48, 171–208.

Cole, H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). Social interactions in massively multiplayer online role-playing gamers. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10, 575–583.

Cole, T., Barrett, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Social facilitation in online and offline gambling: A pilot study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9, 240–247.

Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, e48.

Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 1386–1400.

Demetrovics, Z., Urbán, R., Nagygyörgy, K., Farkas, J., Zilahy, D., Mervó, B., Reindl, A., Ágoston, C., Kertész, A., & Harmath, E. (2011). Why do you play? The development of the motives for online gaming questionnaire (MOGQ). Behavior Research Methods, 43, 814–825.

Donnar, G. (2017). ‘Food porn’ or intimate sociality: Committed celebrity and cultural performances of overeating in meokbang. Celebrity Studies, 8, 122–127.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 466–475.

Gander, K. (2016). 10,000 calorie challenge: The YouTubers eating piles of food to impress their fans. The Independent, October 17, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/youtube-10000-calorie-challenge-furious-pete-rob-lipsett-a7365041.html.

Gillespie, S. L. (2019). Watching women eat: a critique of magical eating and mukbang videos (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved 16 October, 2019, from: https://scholarworks.unr.edu/bitstream/handle/11714/6027/Gillespie_unr_0139M_12971.pdf?sequence=1.

Grant, B. (2015). Meet South Korea’s binge eating TV stars: Thousands of ‘lonely’ viewers tune in to watch young women gorge on enough food to feed a family in one sitting. Daily Mail, October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3280245/Meet-South-Korea-s-binge-eating-TV-stars-Thousands-mukbang-viewers-tune-watch-young-women-eat-food-feed-family-one-sitting.html.

Greatrex, C. (2016). Britain’s first ‘mukbang’ star reveals how she binge eats KFC and Five Guys on camera and stays healthy. Daily Mirror, July 26, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/real-life-stories/britains-first-mukbang-star-reveals-8491536.

Griffiths, M. (1999). Internet addiction: Fact or fiction? The Psychologist, 12, 246–250.

Hakimey, H., & Yazdanifard, R. (2015). The review of Mokbang (broadcast eating) phenomena and its relations with South Korean culture and society. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics, 2, 443–455.

Hawthorne, E. (2019). Mukbang: Could the obsession with watching people eat be a money spinner for brands? Retrieved 21 October, 2019, from: https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/marketing/mukbang-could-the-obsession-with-watching-people-eat-be-a-money-spinner-for-brands/596698.article.

Hicks, A. (2019). Vlogger dies live-streaming himself eating poisonous centipedes and lizards. Daily Mirror, July 24, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/man-35-dies-live-streaming-18763663.

Hong, S., & Park, S. (2018). Internet mukbang (foodcasting) in South Korea. In I. Eleá & L. Mikos (Eds.), Young and creative: digital technologies empowering children in everyday life (pp. 111–125). Göteborg: Nordicom.

Horzum, M. B. (2016). Examining the relationship to gender and personality on the purpose of Facebook usage of Turkish university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 319–328.

Joyal, C. C., Cossette, A., & Lapierre, V. (2015). What exactly is an unusual sexual fantasy? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 328–340.

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354.

Kavanagh, J., Trouton, A., Oakley, A., & Harden, A. (2005). A scoping review of the evidence for incentive schemes to encourage positive health and other social behaviors in young people. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education.

Khazaei, F., Khazaei, O., & Ghanbari-H, B. (2017). Positive psychology interventions for internet addiction treatment. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 304–311.

Kim, J. S., Hart, R. J., & An, H. J. (2017a). The effect of reality program viewing motivation on outdoor recreation behavioral intention: Focusing on the Korean travel reality program “Dad! Where are we going?”. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 31, 33–43.

Kim, D. J., Kim, K., Lee, H. W., Hong, J. P., Cho, M. J., Fava, M., Mischoulon, D., Heo, J. Y., & Jeon, H. J. (2017b). Internet game addiction, depression, and escape from negative emotions in adulthood: A nationwide community sample of Korea. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205, 568–573.

Király, O., Urbán, R., Griffiths, M. D., Ágoston, C., Nagygyörgy, K., Kökönyei, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). The mediating effect of gaming motivation between psychiatric symptoms and problematic online gaming: An online survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e88.

Kırcaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram addiction and the big five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7, 158–170.

Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6.

Kor, A., Zilcha-Mano, S., Fogel, Y. A., Mikulincer, M., Reid, R. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). Psychometric development of the problematic pornography use scale. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 861–868.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012a). Internet gambling behavior. In Z. Yan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of cyber behavior (pp. 735–753). Hershey: IGI Global.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012b). Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10, 278–296.

Kwon, M. W., D’Angelo, J., & McLeod, D. M. (2013). Facebook use and social capital: to bond, to bridge, or to escape. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 33, 35–43.

Lavelle, D. (2018). Mukbang: Is loneliness behind the craze for watching other people eating? The Guardian, November 5, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.theguardian.com/food/shortcuts/2018/nov/05/mukbang-is-loneliness-behind-the-craze-for-watching-other-people-eating.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lee, H. R., Jeong, E. J., & Kim, J. W. (2016). Role of internal health belief, catharsis seeking, and self-efficacy in game players’ aggression. In 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) (pp. 3791-3800). IEEE.

Liu, L. S., Huh, J., Neogi, T., Inkpen, K., & Pratt, W. (2013, April). Health vlogger-viewer interaction in chronic illness management. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 49-58). ACM.

Malm, S. (2014). South Korean woman known as The Diva makes £5,600 a month streaming herself eating online for three hours a day (yet manages to stay chopstick thin). Daily Mail, January 28, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2547254/South-Korean-woman-known-The-Diva-makes-9-400-month-streaming-eating-online-three-hours-day-manages-stay-chopstick-thin.html.

McCarthy, A. (2017). This Korean food phenomenon is changing the internet. Eater, April 19. Retrieved 21 October, 2019, from: https://www.eater.com/2017/4/19/15349568/mukbang-videos-korean-youtube.

McFadyen, S. (2015). Finger lickin’ not so good! ‘Food porn’ YouTube star sucks on a raw chicken in stomach-churning clip. Daily Mirror, December 29, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/weird-news/finger-lickin-not-good-food-7086495.

Montag, C., Bey, K., Sha, P., Li, M., Chen, Y. F., Liu, W. Y., Zhu, Y. K., Li, C. B., Markett, S., Keiper, J., & Reuter, M. (2015). Is it meaningful to distinguish between generalized and specific internet addiction? Evidence from a cross-cultural study from Germany, Sweden, Taiwan and China. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 7, 20–26.

Moran, M. (2019). Mukbang is ‘sexy turn-on’ online trend where fans watch women eat huge takeaways. Daily Star, April 8, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailystar.co.uk/real-life/mukbang-eating-video-korea-australia-17109890.

Owens, E. W., Behun, R. J., Manning, J. C., & Reid, R. C. (2012). The impact of internet pornography on adolescents: A review of the research. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19, 99–122.

Park, K. (2018). South Korea to clamp down on binge-eating trend amid obesity fears. Daily Telegraph, October 25, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/10/25/south-korea-clamp-binge-eating-trend-amid-obesity-fears/.

Pereira, B., Sung, B., & Lee, S. (2019). I like watching other people eat: A cross-cultural analysis of the antecedents of attitudes towards Mukbang. Australasian Marketing Journal, 27, 78–90.

Pettit, H. (2019). Bizarre ‘mukbang’ YouTube trend sees women scoff 20,000-calorie McDonalds meals earning them millions—and is branded ‘sexy turn on’ by some fans, The Sun, April 7, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.thesun.co.uk/tech/8801045/mukbang-youtube-trend-women-earn-millions/.

Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5, 371–385.

Pizzol, D., Bertoldo, A., & Foresta, C. (2016). Adolescents and web porn: A new era of sexuality. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 28, 169–173.

Prohaska, A. (2013). Feederism: Transgressive behavior or same old patriarchal sex. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 1, 104–112.

Prohaska, A. (2014). Help me get fat! Feederism as communal deviance on the internet. Deviant Behavior, 35, 263–274.

Ricijas, N., Hundric, D. D., & Huic, A. (2016). Predictors of adverse gambling related consequences among adolescent boys. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 168–176.

Ritschel, C. (2019). Vlogger attacked by octopus as she tries to eat it during live-stream. The Independent, May 8, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/octopus-eat-alive-attack-face-girl-vlogger-live-stream-video-a8904911.html.

Rosen, C. (2012). Electronic intimacy. The Wilson Quarterly, 36, 48–51.

Rothman, E. F., Kaczmarsky, C., Burke, N., Jansen, E., & Baughman, A. (2015). “Without porn… I wouldn’t know half the things I know now”: A qualitative study of pornography use among a sample of urban, low-income, black and Hispanic youth. Journal of Sex Research, 52, 736–746.

Sadiza, J., Varma, R., Jena, S. P. K., & Singh, T. B. (2011). Group cognitive behaviour therapy in the management of compulsive sex behaviour. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 6, 309–325.

Sanghani, R. (2014). Watching girls binge-eat on camera takes the biscuit, Daily Telegraph, January 20, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/10583917/Sexual-fetish-much-Watching-girls-binge-eat-on-camera-takes-the-biscuit.html.

Schwegler-Castañer, A. (2018). At the intersection of thinness and overconsumption: the ambivalence of munching, crunching, and slurping on camera. Feminist Media Studies, 18, 782–785.

Seidman, G. (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 402–407.

Sherlock, M., & Wagstaff, D. L. (2019). Exploring the relationship between frequency of Instagram use, exposure to idealized images, and psychological well-being in women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8, 482–490.

Shipman, A. (2019). YouTube trend for extreme food challenges encourages binge eating, warn psychologists. Daily Telegraph, September 8, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/09/08/youtube-trend-extreme-food-challenges-encourages-binge-eating/.

Sigre-Leirós, V., Carvalho, J., & Nobre, P. J. (2016). The Sexual Thoughts Questionnaire: Psychometric evaluation of a measure to assess self-reported thoughts during exposure to erotica using sexually functional individuals. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13, 876–884.

Song, H. (2018). The making of microcelebrity: AfreecaTV and the younger generation in neoliberal South Korea. Social Media+ Society, 4, 1–10.

Spence, C., Mancini, M., & Huisman, G. (2019). Digital commensality: Eating and drinking in the company of technology. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, e2252.

Stafford, T. F., Stafford, M. R., & Schkade, L. L. (2004). Determining uses and gratifications for the internet. Decision Sciences, 35, 259–288.

Stanton, J. (2015). The skinny Korean 14-year-old who makes £1,000 a night by gorging on fast food on webcam—while thousands of fans watch. Daily Mail, August 19, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3203221/Skinny-Korean-14-wanted-company-ate-dinner-makes-1-000-night-gorging-fast-food-webcam-thousands-fans-watch.html.

Sublette, V. A., & Mullan, B. (2012). Consequences of play: A systematic review of the effects of online gaming. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10, 3–23.

Terry, L. L., Suschinsky, K. D., Lalumiere, M. L., & Vasey, P. L. (2012). Feederism: An exaggeration of a normative mate selection preference? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 249–260.

Tran, C. (2019). ‘Food turns me on’: how young women are earning a fortune by eating giant plates of takeaway on camera as part of a bizarre social media fad. Daily Mail, April 8, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-6897147/Mukbang-women-share-videos-gorging-food-feed-family-one-sitting.html.

Tu, Y., & Fishbach, A. (2017). The social path to satiation: Satisfying desire vicariously via other’s consumption. In Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research (ACR), Duluth, Minnesota. Retrieved 16 October, 2019, from http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v45/acr_vol45_1024547.pdf.

Wenzel, H. G., Bakken, I. J., Johansson, A., Götestam, K. G., & Øren, A. (2009). Excessive computer game playing among Norwegian adults: Self-reported consequences of playing and association with mental health problems. Psychological Reports, 105, 1237–1247.

Wéry, A., & Billieux, J. (2016). Online sexual activities: An exploratory study of problematic and non-problematic usage patterns in a sample of men. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 257–266.

Wikipedia (2019). List of newspapers in the United Kingdom. Retrieved 18 October, 2019, from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_newspapers_in_the_United_Kingdom.

Woo, S. (2018). Mukbang is changing digital communications. Anthropology Newsletter, 59, 90–94.

Wood, R. T., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). A qualitative investigation of problem gambling as an escape-based coping strategy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80, 107–125.

You, T. (2018). Bizarre trend sees Chinese vloggers flocking to broadcast themselves eating ice as millions of people tune in just to hear the crunch. Daily Mail, February 8, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5367391/Eating-crunchy-ice-new-social-media-trend-China.html.

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2017). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals: An in-depth exploration. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 311–328.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any interests that could constitute a real, potential, or apparent conflict of interest with respect to their involvement in the publication. The authors also declare that they do not have any financial or other relations (e.g., directorship, consultancy, or speaker fee) with companies, trade associations, unions or groups (including civic associations and public interest groups) that may gain or lose financially from the results or conclusions in the study. Sources of funding are acknowledged.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article