Abstract

The Early and Middle Neolithic (3500–2300 [Before Current Era] BCE) Pitted Ware Culture (PWC) was a critical component of the historical trajectory of Scandinavia’s maritime history. The hunter-gatherer societies of the PWC were highly adapted to maritime environments, and they fished, hunted, travelled, and traded across great distances over water. Exactly what boat types they used, however, is still an open question. Understanding the maritime technologies used by the PWC is a critical research area as they had an important impact on subsequent maritime adaptations in Scandinavian prehistory. Unfortunately, finding intact boats from Neolithic contexts is extremely difficult. Here, we present indirect evidence for the use of skin boats by PWC people as a first step towards building a dialog on the types of boats that would have been used during this period. We argue that multiple lines of evidence suggest that skin boats were widely used for every-day activities and long-distance voyages by PWC peoples and will discuss the implications of possible complex boat use by Neolithic peoples for our understanding of early Scandinavian maritime societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ten years ago, Håkon Glørstad (2013a) posed the question “Where are the missing boats?” and discussed the postglacial colonization along the Norwegian coast northwards. He demonstrates that, in taking our archaeological evidence seriously, despite its fragmentary nature, archaeologists can make meaningful contributions to our understanding of human societies and their history. In this case, a significant amount of maritime transport and seafaring throughout the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic including the very early pioneering period can be inferred by looking at artifact distribution and site location, and also by incorporating comparative material produced by ethnography. While not all discussants were in favour of Glørstad’s interpretation that logboats were the major driver of this migration, most were confident that seafaring technologies could be addressed using indirect evidence and acknowledged the idea that some arguments could be made from the absence of certain evidence.

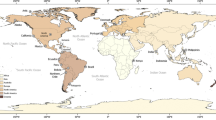

For the Pitted Ware Culture (PWC) of the Early and Middle Neolithic (3500–2300 BCE) in the Baltic region including Kattegatt and Skagerrak (Fig. 1), we are in a similar situation. As is well-published, we know that PWC groups strongly depended on exploiting the maritime sphere which makes it all but certain that they had a highly developed maritime technology. Intact examples of seagoing boats that can be connected to the PWC, however, remain extremely elusive. This is a common problem in ancient maritime archaeology as the succeeding Bronze Age is also plagued by the same conundrum. Researchers are convinced that at this later time plank-built boats were used on a massive scale (Ling 2014; Bengtsson 2015), and still, apart from some logboats (Kastholm 2008, 2015) and a bark boat (von Arbin and Lindberg 2017) no advanced vessel has ever been found. Solid knowledge about boat technology through direct finds only begins with the Iron Age and the discovery of the Pre-Roman Iron Age Hjortspring boat as well as other Iron Age vessels (Randsborg 1995; Crumlin-Pedersen and Olsen 2002; Crumlin-Pedersen 2003).

Map of the important sites mentioned in the text. Map adjusted to sea levels around 3000 BC with the grey line indicating current sea levels. Sites: 1. Hjortspring, Denmark; 2. Verup, Denmark; 3. Hagestad, Sweden; 4. Kainsbakke, Denmark; 5. Kirial Bro, Denmark; 6. Kattegat; 7. Byslätt, Sweden; 8. Kvillehed, Sweden; 9. Huseby Klev, Sweden; 10. Skagerak; 11. Solbakken, Sweden; 12. Kjølberg, Norway; 13. Alvastra, Sweden; 14. Köpingsvik, Sweden; 15. Norrköping (City Hall), Sweden; 16. Åby, Sweden; 17. Fagervik, Sweden; 18. Šventoji, Lithuania; 19. Stora Förvar, Sweden; 20. Stora Karlsö, Sweden; 21. Lilla Karlsö, Sweden; 22. Ajvide, Gotland, Sweden; 23. Hemmor, Gotland, Sweden; 24. Visby, Gotland, Sweden; 25. Ire, Gotland, Sweden; 26. Västerbjers, Gotland, Sweden; 27. Jettböle, Åland, Finland; 28. Tråsättra, Sweden; 29. Bollbacken, Sweden; 30. Västerbyn, Sweden; 31. Ovanåker, Sweden; 32. Västeräng Gävle, Sweden; 33. Sävholm, Sweden; 34. Ragunda, Sweden; 35. Hampnäs, Sweden; 36. Grundsuna, Sweden; 37. Nova Zalavruga, White Sea, Russia; 38. Lethosjärvi, Finland; 39. Alta, Norway; 40. Skjåvika, Norway

For the PWC, it would be easy and intuitively straightforward to simply take ethnographic parallel hunter-fisher-gatherer societies as analogies and assume that Neolithic populations had the same maritime capabilities (Rönnby 2007). However, if we want to gain specific knowledge about local groups and how they used and adapted to the environments they were presented with, then a simple comparative study is not sufficient. We need to analyse other material and see between the cracks that are left by our fragmentary archaeological record. In the following, we will present evidence that may point to the use of different boat technologies. We will ask whether PWC groups utilised seals in the production of sealskin boats. We believe that our analysis will show that skin boats were the most likely watercraft used by PWC people and that considerable direct and indirect evidence exists to back up this proposal.

Previous Research on the Pitted Ware Culture

For more than a millennium, during the Neolithic, the Nordic sphere underwent a highly interesting phase as a culturally very diverse region. After the first farmers of the Funnel Beaker Culture (FBC) tradition established themselves around 4000 BC, a new cultural formation, the Pitted Ware Culture (PWC), appeared circa (ca.) 3500 calibrated (cal) BC (Iversen et al. 2021) (Fig. 2). These hunter-gatherers were named after their ceramics which were decorated with deep pits distributed around the circumference of the vessels (Larsson 2009). However, the most curious feature of the PWC groups was that they were hunter-gatherers with a strong specialization in hunting seals and fishing within a socio-economic setting in which farming was well established for more than five centuries. As such, the PWC was unique in Europe and initially interpreted as a development of FBC society that returned to Mesolithic lifeways (Malmer 2002). However, the Ancient DNA (aDNA) revolution demonstrated that this was not the case and that the PWC was made up of migrating groups from the East (Malmström et al. 2009; Skoglund et al. 2014; Coutinho et al. 2020). After the turn of the millennium around 2800 BC new arrivals belonging to the Corded Ware Culture (CWC) migrated into the Nordic sphere from the south-eastern steppes while the last remnants of the FBC were also still present (Haak et al. 2015; Iversen 2015).

Settlements of the PWC were often fairly limited in size with an average of 25–30 individuals and generally located close to the seashore in sheltered bays that were often clustered in archipelagos (Rönnby 2007; Artursson et al. 2023). There are exceptions to this “rule”, with the settlement of Alvastra, probably being the most famous, which demands a more detailed discussion to demonstrate that even such inland sites depended heavily on boat technology. Compared to the few and relatively simple huts, Alvastra was a huge and complex construction with a considerable mix of PWC and FBC elements like pottery, flint and stone artifacts. Whatever Alvastra was, it was certainly an exceptional place with evidence for mobility and the arrival of many innovations and foreign objects. Anders Browall posits that the people of Alvastra were not passively waiting for these things to arrive, but instead undertook journeys by boat to the outside world with natural anchorages being available north and south of the Omberg hill (Browall 2020).

Provenance studies using modern scientific methods have also indicated that the PWC conducted long distance voyages by sea. Although most PWC ceramics and clay figurines were produced locally, clay sourcing studies show that some were exchanged between distant regions, requiring them to be carried over water to island settlements (Brorsson et al. 2018; Artursson et al. 2023). Strontium isotope studies also show that animals including bears, deer, and cattle were transported across the Kattegat, requiring travel by boat (Price et al. 2021). In the Baltic Sea region, analysis of strontium isotopes from 48 PWC individuals from Västerbjers on Gotland showed that around 9% may have had non-local origins (Ahlström and Price 2021). A similar study using laser ablation strontium analysis on both human and canine teeth from the PWC site of Jettböle in Åland showed that a dog had been transported all the way from Gotland to Åland (Boethius et al. 2024). This would have required an open ocean voyage of considerable distance between Åland, Gotland, and possibly mainland Sweden.

Furthermore, the different stone materials found at PWC settlements and cemeteries clearly indicates the existence of long-distance contacts in the Baltic Sea region. Contacts from the PWC groups in Eastern Middle Sweden to the north, south and east are visible with porphyrite likely imported from the islands of Åland in the east, flint imported from southern Sweden and Denmark, and slate probably originating from Jämtland in the northwestern part of Sweden (Artursson et al. 2023, 116–122). This shows that long-distance networks were in play, supplying raw materials that were not available locally. How this was organised is yet unknown, but judging from ethnohistorical and anthropological studies, it was probably based on a combination of alliances, inter-marriage networks, and long-distance sea voyages. Together, these studies suggest that PWC used boats to travel considerable distances over the sea. The question, therefore, is what type of boats were used and what their capacities may have been.

Stone Age Seafaring

Although finds of Neolithic boats from Scandinavia are extremely rare, there are a number of archaeological, ethnographic, and ethnohistorical parallels that can be used to fill in the gaps of our understanding of the possible types of watercraft that could have been used by Stone Age societies in the Nordic region. Throughout the world, ancient people using stone technologies have built elaborate and sophisticated watercraft that were capable of long-distance, open-ocean voyages. Middle Palaeolithic tool assemblages on the island of Crete indicate that even Neanderthals may have taken to the sea in watercraft (Strasser et al. 2011; Ferentinos et al. 2012). Indirect evidence of ancient seafaring can also be found in the early peopling of Australia around 65,000 years ago, which would have required crossing distances of up to 100 kms of open sea (Clarkson et al. 2017; Bird et al. 2019). By the late Pleistocene, human populations in the Americas were able to navigate icy waters between glacial refugia to reach coastal regions of Pacific North America (Erlandson et al. 2008, 2011; Davis and Madsen 2020). From these examples it is clear that ancient humans navigated open seas from very early times and had developed sophisticated watercraft by at least the Middle Palaeolithic; long before we are likely to find remains of such craft in the archaeological record.

One of the most common types of boats used by Stone Age cultures throughout the world is the dugout canoe or logboat. The oldest archaeologically identified boat find, from Pesse in the Netherlands, is a 3 m-long dugout canoe dated to 10,000 BP which was likely used to navigate lakes and estuary waters (Lanting 1997). In historic and ethnographic times, numerous examples of dugout canoes can be found from maritime cultures throughout the world. These range from small examples similar to the Pesse canoe, to massive over 18 m-long war-canoes found on the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America (Ames 2002; Moss 2008). Dugout canoes were built by hollowing out the interior of large logs, either with stone adzes or through the use of fire (Ling et al. 2020). Even where boats are not preserved in the archaeological record, these techniques would produce tools and firing pits that could potentially be identified (Ling et al. 2024). The range in size of dugout canoes correlates with a range of functions. While smaller dugouts were not very seaworthy craft, large Haida canoes were capable of open-sea and long-distance voyages (Moss 2008). In ancient Scandinavia, a wooden paddle from Västerbyn in Dalarna, dated to 9000 BP, suggests a very old date for the use of boats. The oldest intact logboats found in Scandinavia come from Denmark, where they were known from the late Mesolithic Ertebølle Culture and onwards (Christensen 1990; Kastholm 2014). Resin imprints from potential logboats at the site of Husby Klev also provide evidence of possible boat use from the Early and Middle Mesolithic (Nordqvist 2005).

There was considerable variability in the seaworthiness of dugout canoes depending on their length, width, and construction characteristics. Large expanded-side boats such as those used by the Haida in North America could carry large crews and were capable of long-distance voyages in the open ocean (Moss 2008). Likewise, massive canoes such as those found at the Marmotta lake in Italy were likely seaworthy craft (Gibaja et al. 2024). Marmotta 1, for example is 10.43 m long, 1.15 m wide, and, 65 cm deep (Gibaja et al. 2024). Experimental reproduction of the Marmotta 1 canoe showed it to be highly seaworthy, capable of open ocean voyages in the Mediterranean and even the Atlantic (Tichỳ 2016; Gibaja et al. 2024). Extremely large dugout canoes carrying many dozens of paddlers were also used for open ocean trade in ancient Mesoamerica (Fitzpatrick 2013), On the other hand, ethnohistoric data from Pacific North America suggests that smaller dugouts with widths of less than one meter were considered more dangerous than other boat types due to the risk of rolling over in rough seas and were mostly used on lakes or rivers (Hudson et al. 1978; Hudson and Blackburn 1979; McGrail 2002). Most Neolithic dugouts from Scandinavia are fairly small in size, suggesting nearshore use. Extremely large boats such as the 11 m long and 1.5 m-wide Bronze Age log boat from Kvillehed near Gothenburg (Kastholm 2014, pp. 157–158), however, may have served as war canoes or trading vessels. The fact that most Neolithic log boats from Scandinavia have been found in inland lakes and bogs (Christensen 1990) also suggests they may have not been often used at sea.

In the Baltic Sea region, tests designed to evaluate the possibility of dugout use on the open sea were undertaken within the Gotland’s Stone Age project by Sven Österholm (1997, 2002) during the 1980’s. Based on a relatively wide mixture of pictorial evidence from the Scandinavian Bronze Age and, more recently, Hawaiian rock art, historical parallels including ancient Egypt, and ethnographic evidence for canoes, two boats with outriggers were produced. The first (Alkraku) was a log boat made from a Tilia and the second (Alkraku II) used a Poplar tree for the base. It was a simple outrigger construction with two planks added as raised sides and a gunwale built in a clinker technique. Alkraku completed two short journeys across open the sea of two (Lilla Karlsö) and four nautical miles (Stora Karlsö) with two paddlers in relatively high seas without problems, reaching speeds of up to 3 knots. The larger Alkraku II was used for a longer sea journey of about 100 kms, crossing from the island of Gotland to the Swedish mainland using both paddles and sails. This crossing was made in relatively high seas and with strong winds. These experiments showed that dugouts could potentially be seaworthy when combined with outriggers, but it is notable that no clear archaeological or historical evidence for outrigger use exists in Europe (c.f. Von Arbin and Lindberg 2017).

Boats made from reed bundles are also a widespread and certainly very ancient form of watercraft. In Pacific North America, small boats shaped from three to five bundles of reeds are ethnohistorically documented as being commonly used for near-shore fishing, the navigation of estuaries, and occasional open ocean voyages under good conditions (Hudson et al. 1978; Hudson and Blackburn 1979). Similar reed boats are still used today in Pacific South America by fishers in coastal areas and freshwater lakes (Prieto 2016). Larger reed boats, such as those used in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, were capable of longer-voyages in the open sea, especially if waterproofed with tar (McGrail 2002). Unfortunately, reed boats are highly perishable and are highly unlikely to be received archaeologically. Tools used to cut reeds, however, might be possible to identify in the archaeological record, especially with the help of use-ware analysis for example on flint sickles of which thousands exist in Scandinavia and around the Baltic Sea from the Mesolithic through to the Late Bronze Age (Högberg 2004; Meeks et al. 1982; Slah 2013).

Composite boats made from combinations of dugouts, reed bundles, and planks are another critical category of ancient boats that are often overlooked in the archaeological literature. By combining a dugout log hull with reed or plank sides, ancient mariners and boat engineers could design very seaworthy craft. An excellent example of a boat of this type comes from Cedros Island off the Pacific Coast of Mexico where indigenous islanders built such boats (Des Lauriers 2005). Although these composite boats were able to navigate rougher seas than simple dugouts or reed craft, a major drawback is their relatively slower speed. Some log boats from Scandinavia have drill holes lining their sides that could have been used to fasten reed bundles or to otherwise construct composite craft (for example, the Verup boat from Denmark dated to 2100 BCE). Alternately, these holes could have been used to attach skins or textiles to protect paddlers and cargo from waves. Log canoes with outriggers could also be considered as a form of composite craft. Outriggers give great stability to boats and were common in ethnohistoric times in the Pacific but are entirely unknown in ancient or historical Europe.

Skin boats are another type of highly seaworthy watercraft that was used by many different cultures throughout the world. Skin boats were especially common in Arctic environments such as Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia, but were also commonly used in historic times across much of North America and in parts of Europe such as Ireland and Britany (Adney and Chapelle 2007; Anichtchenko 2012, 2016; Luukkanen and Fitzhugh 2020). In Europe, the currach was a similar boat used during historic times in Ireland and Brittany. It has also been suggested on mainly theoretical grounds that skin boats were used in Scandinavia during the Early Mesolithic (Bang-Andersen 2013; Wikell and Pettersson 2013), but both direct and indirect evidence is scarce (Schmitt 2013, 2015). Glørstad (2013b) has pointed to a lack of evidence for skin boat use during the Mesolithic as a reason to focus instead on logboats as likely sea-going vessels. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to comment on debates regarding boat use in the Mesolithic, a major goal of our following discussion is to compile the available evidence, both direct and indirect, for the possible use of skin boats by Neolithic peoples.

One of the classic examples of a skin boat is the Inuit Umiak (Fig. 3), which was made from seal skins sewn over a frame of wood or bone and waterproofed with seal oil (Adney and Chapelle 2007; Anichtchenko 2016). Umiaks were often around 10 m in length and could carry up to 15 passengers. Occasionally, especially large craft of up to 18 m were built (Adney and Chapelle 2007). A lightweight boat, the Umiak was capable of long-distance voyages and was especially adapted to arctic terrain due to its ability to be easily lifted from the water and carried over ice. It has been observed that they can cover 60–160 km (km) assuming 10 h(h) of rowing per day and that they could do so for 3–5 days before they need to be dried (Anichtchenko 2016). This means that, on average, seafarers could have covered 490 km in a journey that includes some, but calculable, risk which would have been enough to cross the open waters of the Baltic Sea (see Alvå 2024). Since Umiaks were used by maritime hunter-fishers which are in terms of their domestic economy and access to seal skins very similar to our case of the PWC, we use the Umiak as our main point of comparison. The culture of the Inuit people who used and continue to use Umiaks are low density maritime fisher foragers living in an arctic environment. These characteristics match what we know about the PWC and make Umiaks an especially suitable form of maritime technology from which to draw inferences about potential ancient Scandinavian sewn boats.

Bark boats were comparable to skin boats in that they were built of sewn bark spread over a wooden frame. Bark boats were commonly used in both North America and Eurasia during ethnohistoric times and were highly effective vessels (Adney and Chapelle 2007; Luukkanen and Fitzhugh 2020). A spectacular find of a bark boat dated to the Bronze Age was excavated in the river Viskan outside of Gothenburg and proves that boats of this type were used in Scandinavian prehistory (von Arbin and Lindberg 2017). Exactly how early this tradition may have been projected into the past in Scandinavia is difficult to know since extreme circumstances are required for bark to be preserved in the archaeological record. Made entirely from perishable materials and lacking an associated faunal record, bark boats face even greater preservation problems than skin boats. This paper focuses primarily on skin boats, but we acknowledge that bark boats may also have been used in the Neolithic and are a worthy and challenging subject for future research.

Sewn plank boats were one of the most complex boat types built by people during the Stone Ages around the world. By sewing planks together into the shape of a boat, ancient mariners were able to construct highly sophisticated watercraft without the use of metal nails. Building such boats required wood planks, cordage to sew them together, and copious amounts of tar to waterproof the seams between the planks. Stone axes, adzes and reamers could be used to split planks and drill holes as evidenced by the advanced plank boats built by non-metal using cultures in the Pacific (Hudson et al. 1978). Sewn plank boats were built by traditional societies throughout the world including in Japan, North America, Polynesia, India, South America, and Europe (Hudson et al. 1978; Westerdahl 1985; Ohtsuka 1999; Gamble 2002; Fauvelle 2011, 2014; Fauvelle and Montenegro 2024; Fauvelle et al. 2024). In Scandinavia, the early Iron Age Hjortspring boat is believed to be a representative of the type of sewn plank boat used by ancient mariners during the Bronze Age due to its similarity to the south Scandinavian rock art (Crumlin-Pedersen and Trakadas 2003). A find of a plank-built boat fragment in Hampnäs, northern Sweden was C14 dated to the fourth century BCE giving testament to the use of this boat type on the Scandinavian peninsula in ancient prehistory (Ramqvist 2010). Similar boats were also used by Sami people in historic and modern times (Westerdahl 1985). Currently, however, no evidence has survived that such sophisticated craft were built during the Nordic Neolithic.

Intact finds of boats dating to prehistoric times are extremely rare. Although exceptional finds such as the Hjortspring boat or the Byslätt canoe point to the varied and complex use of watercraft by prehistoric Scandinavians, we cannot expect that all boat types used in the region will be identified in the archaeological record. Because of this, it is critically important that we complement archaeological information on ancient watercraft with evidence drawn from ethnographic analogies. In the case of the PWC, we argue that the Inuit use of the Umiak is the closest cultural, environmental, and technological parallel that we can use to construct testable hypotheses. Not only are skin boats especially suited to the kinds of environmental conditions faced by PWC groups, they can also be constructed with the tools we know were available to the PWC, thus making them capable of the kinds of voyages we suspect they engaged in, and used materials (seal skins and seal oil) that we know the PWC had in abundance. To support this hypothesis, we will present a range of direct and indirect forms of evidence to build the case for the use of skin boats by the PWC.

Evidence of Skin Boats Use by the Pitted Ware Culture

Apart from a few logboats, no intact finds of other boat types from the Neolithic currently exist in Scandinavia. However, this absence of evidence should not be taken as evidence of absence. If we look at the archaeological data with the construction and use of watercraft in mind, many lines of direct and indirect evidence exist that point to the use of skin boats by PWC groups. These lines of evidence include potential boat fragments, depictions of skin boats in rock art, tool assemblages, as well as the subsistence economy and the resources it produced. While in isolation none of this would be enough to support our argument, we maintain that combining these lines of evidence makes for a compelling case for the use of skin boats.

Direct Evidence I–Boat Fragments

There are some indications that skin boats may have been used in northern Europe as early as Palaeolithic times. Retrofitted reindeer antlers from northern Germany, originally associated with the Ahrensburg Culture but now dated to the late Mesolithic, have been interpreted as potential frames for skin boats (Tromnau 1987; Lanting 1997; Hallgren 2008; Fletcher 2015). In support of the possible use of skin boats during the Palaeolithic and Early Mesolithic, several scholars have pointed out that current evidence for the use of paddles seems to predate the earliest recovered log boats by several thousand years (Lanting 1997; Smith 2002). This is also the case in Scandinavia, where the oldest direct evidence of boat use in Sweden comes from the Åkermyren paddle which was C14 dated to between 7040 and 6650 BCE, predating Sweden’s oldest intact log boats by thousands of years (Fig. 4). It should be noted, however, that possible indirect evidence of boat repair in the form of pine pitch imprints has been found at the Mesolithic site of Husby Klev, potentially predating the Åkermyren paddle (Nordqvist 2005). As dugout and skin boats are each better suited to different uses, it seems likely that dugouts would not replace the use of skin boats, but rather that each type of boat would continue to be used.

There are four finds from northern Sweden that may represent direct evidence of Neolithic skin boat use. All these finds were collected in the early twentieth century and were originally interpreted as either sled or sleigh skis (Berg 1934). Recent re-evaluations, however, have pointed to their rounded bottoms, lack of wear consistent with use on snow or ice, and regularly spaced lashing holes as evidence that they might instead be the keels of skin boat frames (Marnell 1996; Jansson 2004). Two of these finds have been C14 dated to the Neolithic with the Ragunda find dated to between 3634 and 2914 BCE and the Grundsuna find dated to between 3367 and 3096 BCE. Two other finds, from Ovanåker and Sävholm were pollen dated to either the Neolithic or the Bronze Age. A lack of associated finds makes it unclear whether these artefacts were used by PWC Groups, but should they represent skin boat keels, then it is a clear indication that skin boat technology was contemporary with the PWC and could have been used to make journeys across the Baltic.

Sleighs and watercraft share many design characteristics that make them difficult to distinguish. We agree with Marnell (1996) and Jansson (2004), however, that at least the Ragunda, Grundsunda, and Sävholm finds have characteristics that indicate that they could have come from skin boats (Fig. 5). Most notably, the bottoms of these three objects are rounded, which would be impractical for sliding across snow and ice yet is of no hindrance for a watercraft. Several are also slightly curved along their whole length in a way which would seem impractical for a sleigh blade. This is notably not the case for the example from Ovanåker, which is much flatter than the other examples and seems the most likely of the four to have been from a sleigh. Unfortunately, without finding a more intact example it may be impossible to definitively prove that these artifacts are in fact boat keels. When combined with the other lines of evidence presented in this paper, however, we believe a compelling case can be made that these are skin boat fragments and represent direct evidence of skin boat use in the Baltic region during the Neolithic.

Direct Evidence II–Rock Art

In the following, we will focus on the so-called northern Scandinavian rock art tradition and the evidence for boat technology that can be found in these carvings and rock paintings. To effectively sample this vast corpus, the panels of the Alta (Finnmark, Norway) world heritage area have been chosen for analysis with some other sites across Scandinavia serving as points of comparison. Rock art from the Alta represents some of the most extensive material from this period and rock art tradition, making it an excellent source for a comparative study of seafaring practices during the Nordic Neolithic. While the northern rock art tradition began before the PWC was present in the Baltic Sea, it is partially contemporary with the PWC. Most of this tradition was located in areas neighbouring the PWC territory, yet some sites such as Tumlehed in Västra Götaland (Schulz Paulsson et al. 2019) have a PWC component while others like Nämforsen had easy maritime access to the Baltic Sea coast and was close to contemporary PWC groups (Larsson and Broström 2018). The slate discovered in the settlement in Tråsättra (Uppland) may provide proof of such contact between PWC and rock carving groups because it could have come from Ångermanland where Nämforsen is located (Artursson et al. 2023).

The northern Scandinavian rock carvers were maritime hunter-gatherers, making them socio-economically similar to the PWC. Their images clearly show this, for example at the site of Tumlehed where panels contain images of boats, elk, and fish, indicating hunting and fishing (Schulz Paulsson et al. 2019). Similar activities have been associated with the PWC. Thus, a close examination of these images can provide critical information of local pre-existing and contemporary nautical technology that may have influenced and, since the northern tradition outlasts the Middle Neolithic, subsequently also have been influenced by PWC boat technology. Northern rock art vessels have previously been interpreted as Umiaks (Lindqvist 1983; Helskog 2014; Gjerde 2015, 2021) which is why we restrict our comparison mainly to these boats and ethnographic logboats. The purpose of our re-investigation is to highlight the potential for new lines of evidence suggestive of Neolithic skin boat use.

The rock art corpus of Alta comprises of 6000 engraved images spread over 100 panels that were located along the prehistoric coast (Tansem 2020). These panels contain animals including marine creatures such as whales, seals, and fish, as well as a considerable number of boats of various sizes (Gjerde 2010). The panels which are assumed to have been originally located close to the ancient coast are dated primarily using shoreline displacement as the land uplift was relatively steady in this area (Tansem 2020). Their age is assigned based on their distance from the modern shoreline (Helskog 2014; Tansem 2022). Many especially large panels, however, are thought to contain carvings from multiple time periods.

Older carvings at Alta have been dated to 5000–3000 BC. This includes panels at Hjemmeluft where different vessels were depicted with elk-headed stems at the bow (Fig. 6). Crew on these boats were depicted in the shape of vertical strokes or anthropomorphs (Helskog 2014). The profile view of the many rock art boats has a close resemblance to ethnographic Umiaks (Lindqvist 1983; Helskog 2014; Gjerde 2015, 2021). The activities depicted in association with these boats also parallels known uses for Umiaks, including depictions of whaling, seal hunting and the transport of groups of people (Fig. 6). It is worth noting that some of the anthropomorphs are standing below the gunwale of the boats, but their bodies are nevertheless visible. This may have been a way of depicting people standing inside backlit skin boats which is an attribute of Umiaks made from seal skin. Another supporting argument that these vessels represent skin boats is their reduced wood requirements, because wood would have been in short supply or unavailable near Alta (Van de Noort 2012; Helskog 2014; Bjerck 2017; Gjerde 2021). Based on these arguments, we agree with earlier interpretations of these vessels as skin boats (Lindqvist 1983; Helskog 2014; Gjerde 2015, 2021).

Two-dimensional images are a naturally limited medium and it is therefore prudent to compare the rock art from Alta with Inuit depictions of Umiaks made on ivory tools. Several carvings from Alta depict boats with harpoons resting on the elk-headed stems. Interestingly, the ethnographic data shows that stems on Inuit Umiaks were sometimes equipped with a forked harpoon rest made of ivory that could give the impression of ears on animal heads (Hoffman 1897, p. 798 plate 29). That these were in fact used for harpooning is showcased by Inuit harpoon hunting depictions of Umiaks which closely resemble the Alta carvings (Fig. 6). Based on these similarities it is possible that the elk heads on the Alta carvings might also represent harpoon rests. The placement of the anthropomorphs on some Inuit images is in line with the way Umiaks have been crewed with harpooners mostly in the front of the vessel (Anichtchenko 2016). Based on these comparisons between the rock art from Alta and Inuit carvings, it might also be possible that some of the Alta art depicts whale hunting scenes.

A device made from bone discovered in Skjåvika (Finnmark, Norway) may indicate that the elk heads depicted on the Alta carvings could also have potentially been used as harpoon rests or fishing line guides (Gjessing 1938). Technical details on this artifact made Gjessing (1938, Fig. 4, 182–184) assume that it could have been fixed to the side of a skin or plank-built boat. Should it have been attached to one end of the boat it would appear like ears, and thus, give the boat an animal-like appearance when viewed in profile. The device could also have guided a line fixed to a harpoon. Usually, animal heads depicted in rock art are interpreted as an ornament connected to local cosmology where elks may have been seen as liminal agents that could travel between the terrestrial and the maritime world because they are capable swimmers (Westerdahl 2005). However, the ethnographic and archaeological record discussed here indicates that they could have served also a practical function as harpoon rests which may point to a double function.

To further examine the possibility that the boats depicted at Alta and elsewhere could have been Umiak-like skin boats, we conducted a typological comparison of carvings based on size ratios measured on the inner extremes of the vessels (see further Alvå 2024). This method was successfully deployed to interpret the construction of later vessels by Richard Bradley (2008) who calculated length to height ratios of stone ship settings. Here we have applied the same method to the Alta carvings in order to identify potential differences between different categories of vessels.

Overall, the length-height-ratio can be used to separate rock art boats into different types. The majority of the boats have an inner length to height ratio below 5:1 which may classify them as relatively compact boats. This is lower than the illustration of a regular Inuit Umiak ratio which is 8:1. However, these stout boats could still be skin boats due to having a translucent hull (Fig. 6). They could also be representations of small skin boats similar to the North American coracles used in Missouri or the Curragh used in the British Isles (Bradley 2008; Steinke 2017). Interestingly, these robust vessels seem to have performed the same activities as their larger counterparts. It is reported that historic European coracles were used to brave the open seas of the Atlantic Ocean and could have been used for whaling and seal hunting (Bardi and Perissi 2021; Hornell 2014).

The making of Scandinavian rock art required a compromise between richness of detail, for example in realistic animal depiction or the mimicking of landscape features, and the clarity of expression to keep images and scenes readable for the observer (Helskog 2014; Horn 2022). This sometimes influences the way in which things were depicted with some features being exaggerated while others were more abstract, and the size scales between different images. As a result, the ratios of boats could be off because certain details may be exaggerated or simplified, for example the height of the hull to allow space to represent details on it or the crew inside (Ling 2014). It may be possible to observe a similar phenomenon on the depictions of Umiaks with some being represented more compact than the photographic evidence of their real-world counterparts. The range of the length-height ratio of Umiak depictions varies significantly and their average is 6:1 lower than that of real Umiaks (8:1) (material in Hoffman 1897; cf. Alvå 2024). This average is much closer to the 5:1 of the compact boat type defined for the northern Scandinavian rock art and allows for the possibility that they could depict seaworthy skin boats of types similar to either coracles or Umiaks. The notion that some of these rock art boats were in fact representations of Umiaks is supported by examples of more elongated boats like on the panel Ole Pedersen 11A with a ratio of 7,5:1 which is crewed by seven anthropomorphs, with the individual at the front being equipped with a harpoon for whaling (Fig. 6).

On the large Kåfjord panel are 12 boats with an average ratio of 6:1 which places them within the range of ethnographic Umiak depictions (Hoffman 1897). These vessels seem to carry a large soft edged object which could be cargo. Further depictions of cargo being transported can be seen on the panel Bergheim 6 which features a very elongated vessel (11–9:1) carrying two reindeer which exceeds the size of an average Umiak (Fig. 7). This ratio is closer to that of log boats with an average of 10,7:1. Before excluding the interpretation of a skin boat as the vessel type, other construction details need to be considered. Its hull may be interpreted as translucent, and it is being used in transportation of goods, a function which is ethnographically similar to that of Umiaks (Anichtchenko 2012). This suggests that this vessel could be a large Umiak, although the possibility that it represents a log boat cannot be ruled out.

To sum up, the measured ratios and ethnographic comparison including indigenous artistic images indicate that there could be two types of skin boats depicted among the carvings in the Alta rock art area. It is clear that depictions like rock art and ivory carving are a difficult material to investigate and compare to each other because both went through several culturally specific filters. However, we found enough similarities in the depictions, like ratios, translucent hulls, and depicted cultural uses, to suggest that one or two different types of skin boats, as well as log boats, were well-established maritime technologies during the Middle Neolithic rooted in earlier times. Contemporaneity, proximity, and perhaps contact make it likely that the PWC on the coasts of Kattegat, Skagerak, and the western coast of the Baltic Sea were not only aware of this but utilized similar vessel types. Especially the skin vessels could have been used to regularly transverse the open sea, maritime transport of larger cargoes, and longer hunting expeditions of large prey.

Indirect Evidence

In addition to direct evidence from boat fragments and depictions of boats, the use of skin boats can be inferred from several lines of indirect evidence. For example, we can make a good case for the use of relatively light, but highly seaworthy craft similar to the Umiak from analysing how PWC settlements are connected across a broad seascape of islands and coasts. Iversen and colleagues published a revised chronology of radiocarbon dated PWC settlement sites (Iversen et al. 2021). In total, they presented 110 which we took as a good sample to study the general location of PWC settlement sites in the landscape. This left 103 locations which were georeferenced and visualized on a map with shorelines calculated for ca. 3000 BC in ArcGIS Pro. Afterwards, twelve additional sites were added for which good archaeozoological analyses existed. These were not only located in Sweden but also Finland and Estonia. For each site of the 115 sites, a viewshed analysis was conducted assuming an average height of 1.6 m (m) for a human standing and observing their surroundings. The maximum viewing distance was set to 5 km which is roughly the limit of human sight on a clear day.

The results demonstrated that the vast majority of sites were located openly in the seascape on small islands directly at the beach and along the mainland coast with some in the innter parts of fjords and bays, but still very close to the beach. One prominent example that was recently published is Tråsättra where excavations showed at least six huts that were situated only a few meters away from the shore (Artursson et al. 2023). The viewshed analysis showed that most sites with few exceptions (e.g. Hagestad) had an excellent view over long stretches of coastline in fjords (e.g. Solbakken, Fagervik), bays (e.g. Västeräng Gävle, Åby, Köpingsvik), straights (e.g. Kjølberg, Kainsbakke, Bollbacken) or the open sea (e.g. Tråsättra, Stora Förvar, Visby, Jettböle). Some sites were further inland like Alvastra close to lake Vättern (Browall 1986, 2011, 2016). While the settlement itself was some distance from the lakeshore, it had a good view of the bay south of the Omberg.

Indirect Evidence I–Subsistence Economy

The location of the settlements generally being close to water is tightly linked to the PWC subsistence economy which was highly varied depending on location including signs of possible animal husbandry especially in the south-east (Makarewicz 2023; Pleuger and Makarewicz 2020). Especially on Gotland there are boars, a substantial component of hunted land animals which seem to have carried some significance for the population buried in Västerbjers as well as the inhabitants of the settlements, especially Hemmor and Visby (Molnar 2010; Martinsson-Wallin 2008; Janzon 1974). However, the most frequently hunted animals according to bone assemblages were seals and fish (Eriksson 2004; Storå 2000; 2001; Olson 2008) and together with birds, fish are most likely underrepresented, because of the structure and smallness of their bones which makes them more susceptible to decay (See Artursson et al. 2023; Storå 2002). Even in locations like Västerbjers and elsewhere, where pig bone predominated (Ekman 1974), fish was indeed the dominant nutritional source which was shown through isotopic evidence (Ahlström and Price 2021; Lidén 1996). That means settlements overlooked hunting and fishing grounds so that crews going out often could be observed by those staying at home. Vice versa, the settlements would be visible from many locations at sea, and on longer journeys, long before arrival.

The two most common species of fish were Gadus morhua and Trachinus draco.Footnote 1 While these fish prefer the littoral zone there is good reason to assume that canoes were necessary to fish them as G. morhua preferred depths of 150–200 m (max. 0–600 m). During the day they form schools and swim higher with juveniles preferring even shallower waters (Wilmot 2005). Clark (1946) interprets the presence of G. morhua as direct evidence for fishing from boats. T. draco on the other hand has a much shallower range preferring 1–30 m (max. 1–150 m). Being nocturnal, this species stays buried in the ground during the day and begins to swim freely during the night which may imply that they were fished at night. There is another reason to use a canoe when fishing T. draco. Their dorsal fins carry a potent venom that can be injected into an unlucky person stepping on them. This venom, while rarely deadly, is reported to be excruciatingly painful causing local pain, abdominal pain, inflammation, nausea, necrosis, vomiting and an inflammation that can cause oedema at the wound. Systemic envenomation can lead to increased heart rates, heart failure, and respiratory distress (Gorman et al. 2020).

While fish were perhaps the most important resource in terms of absolute numbers for most PWC groups, a substantial portion of the bone material in settlement sites comes from seals (summarized in Storå 2002). The three recurring seal species at PWC sites were harp seal (Phoca groenlandica), ringed seal (Phoca hispida), and grey seal (Halichoerus grypus). The behaviour of seals predicates that they were hunted by boat as they prefer to congregate while staying further from the shore on reefs, small islands, and floating ice. While clubbing may have been accomplished by wading into the shallow water, hunting with nets and harpooning also occurred, they were likely carried out from boats (Zagorska 2000). Especially the harp seal, which is the dominant species in Ajvide (Gotland), may have been hunted further out from the coast (Storå 2002). A metric comparison of seal femora (Rowley-Conwy and Storå 1997) indicated seasonal hunting mainly during late winter and early spring on their breeding grounds on the ice, but harp seals may also have been hunted during later times in the year. Mostly, sub-adult seals were hunted with some adults being present. The reason may be that young seals do not enter the water to flee before their first moult, approximately four weeks after their birth. Also, depending on species, adult individuals weigh between 70 and 300 kg (kg). Even at birth harp seals weigh 8–9 kg on average fattening up in four weeks to gain an average 33 kg. This clearly requires transporting them to the settlements by boat. Direct archaeological evidence for harpooning seals from boats was discovered in 1907 in an excavation during the building of Norrköpings city hall. The skeleton of a young P. hispida was discovered in direct association with a bone harpoon in the clay of a former seabed (Clark 1946). The harpoon point is intact. Perhaps the line attachment broke and the unlucky hunter lost their prey which still died and then sunk to the ground with the harpoon. Two similar finds have been made in western Finland associated with two Comb Ware sites (Clark 1946).

Indirect Evidence II–Seal Fauna

In an analysis of the bones from PWC sites on Åland, Jan Storå (2000) writes that seal bones were in general not very suitable to be used as a raw material for tools. In line with this, it is sometimes claimed that PWC hunters and gatherers mainly exploited seals for oil production in addition to hides and meat (Svizzero 2015). However, some evidence suggests that not all remaining parts of seals went to waste. In Ajvide, femora and fibula were transported because they are underrepresented in the deposition layers (Storå 2002) and seal teeth are present in large numbers in burials (Burenhult and Brandt 2002). According to Schnittger and Rydh (1940) more than 14% of the awls discovered at Stora Förvar were made from seal fibulae. This may also have been the case at Ire on Gotland as a bone pendant from burial 4 was probably made from a seal fibula (Janzon 1974). This would be precisely a part of the seal skeleton that was not discarded but transported from Ajvide. Many of the harpoons were produced from hollow bones like femora, but unfortunately, the species are undefined. Many large awls and other bone tools are known from sites on Gotland and elsewhere (Stenberger et al. 1943; Janzon 1974), but unfortunately, the animal species was rarely identified. From other sites in the eastern Baltic Sea region, namely Estonia, we know that awls were crafted out of seal bone (Luik et al. 2013). The roughly contemporary site of Šventoji in Western Lithuania has produced a large number of tools manufactured from seal tibia that may have been used mainly for hide scraping according to use wear analysis (Osipowicz et al. 2019).

This leads us to seal skins that may have been a major reason to hunt seals apart from nutrition and to extract oil, a subject to which we will return. Unfortunately, the odds of seal skins being preserved until today are very low and no finds have been reported for the time and geographical area considered in this paper. However, ethnographic reports demonstrate that Inuit have used seal skin traditionally for a wide range of purposes including for clothing, tents, and dog harnesses (Mathiassen 1928). Crucially, they also used these skins to build boats. Clark makes the interesting suggestion that the awls discovered on many Neolithic sites across the Baltic may have been used to perforate seal skins presumably to sow them (Clark 1946). In addition to making up the exterior covering, seal skin could have been used for other functions on boats. It has been reported that seal skin thongs were used by people in Scotland to fix ploughs to their horses instead of ropes, which means they may be sturdy enough to fix seal skins on wooden frames to build a boat (Martin 1934; via Clark 1946). Seal sinew could also have been used. A Curragh from Donegal in Ireland was originally covered with seal skins, indicating the potential use of seal skins in boat production (Evans 1943).

In summary, seal was an all-purpose prey item for PWC communities of which most parts could be put to important uses. These uses were likely varied and fulfilled important roles in the domestic and political economy. This extends to the potential abundance of seal skin for which one important ethnographical use was for skin boats (Anichtchenko 2016). Combined with the evidence for the contemporary knowledge of skin boats, it is a possibility with a good likelihood that PWC communities also used seal skins for this purpose.

Indirect Evidence III–Tool Types

Stone scrapers are one of the most common tool types found at PWC, suggesting that hide processing was a major activity (Rasmussen 2020). The recent publication of the PWC settlements on Djursland of Kainsbakke and Kirial Bro confirm this with scrapers being by far the most numerous tools apart from flint flakes (Wincentz 2020). Other stone tools may also have been involved in hide processing. Experiments and use-wear studies indicated that large flint crushing stones may have been used to abrade hides (Rasmussen 2020). Tools such as blades could also have played a role in hide preparation, although they could have been used for other purposes, as well. Interestingly, use-wear analysis on stone material from the settlement in Tråsättra found that while some scrapers were used on soft materials, others may have been used on wood perhaps in debarking. The same was found for some of the knives. An awl was found to be used on soft material which could have been hides, or perhaps meat or plants. One of the tools interpreted as a drill was equally used on soft materials which could indicate that it served a similar function as the awl (Knutsson and Knutson 2020). All of these potential uses would be consistent with constructing skin boats, although other potential activities could have left similar patterns.

Seal bone tools have also been used for hide processing (Osipowicz et al. 2019). Although the hides are not preserved any longer, we can perhaps infer that some of them came from the seals that provided the bone for the scrapers. Another indication from seal bone tool use may similarly indicate that seal skin was processed with them. A very conspicuous find in Gotland’s Middle Neolithic burials are large bone awls which were made mostly from boar, but in some cases of seal bone (Stenberger et al. 1943; Janzon 1974, 56). That seal skins were used is perhaps indicated by the find of a seal claw that was discovered in burial 6 in Ire on Gotland. Janzon (1974, 22) speculates that this claw indicates the presence of a seal hide in this burial. We can hypothesise that not only the bones of seals were utilized, but that the awls may have been used to pierce and sew seal skins. The awls are probably too large for clothing and more suitable for more substantial seams perhaps like those on tents and skin boats.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that the PWC material culture comprises flint sickles (Andersson et al. 2016; Rasmussen 2020). These sickles could of course have been used for a variety of purposes. However, reed and other plant cutting seems to have predominated (Andersson et al. 2016). This material was likely used for a wide array of different purposes, including perhaps for reed boats like the ones known ethnohistorically and archaeologically, but also for rope and string which may have been used to sew and tighten skin boats.

Indirect Evidence IV–Seal Oil

A final line of indirect evidence comes from the massive amounts of processed seal oil that was present at PWC sites. Seal oil residue has been found through residue analysis on numerous PWC ceramic sherds and was likely an important trade good in exchanges with BAC and FBC people. Several PWC sites also have seal oil features where large amounts of spilled seal fat created lenses of dark and fatty soil. Seal oil would have been used for many purposes within Neolithic society including for food, as lamp oil to create light, and for combustion. Another possible use, however, would have been to waterproof the sealskins that would have been used to make any potential skin boats. Copious amounts of seal oil would have been needed not only to construct skin boats, but also to maintain them as skins would have needed to be re-oiled as often as every four days (Schmitt 2013). It is possible, therefore, that the well documented production of massive amounts of seal oil by PWC groups may have been driven by boat building needs.

A famous example of one such large seal oil feature was found at the site of Ajvide on Gotland. Here a thick lens of dark, black, greasy soil smelling strongly of seal oil was found covering an area some 220 square meters in size (Burenhult and Brandt 2002; Österholm 2002). Due to the feature’s location inside of the Ajvide cemetery it has traditionally been interpreted as a ritual site and possible “seal altar”. We suggest that an alternative interpretation, however, could be as a work area for the waterproofing of seal skin boats. Waterproofing activities would have required large amounts of oil, much of which would have been spilled into the surrounding soil creating archaeological signatures similar to that found at Ajvide. Marine mammal fats have also been identified from the interiors of PWC ceramics (Isaksson 2009), possibly suggesting the storage of oils for the purposes of treating skins. Inuit seafarers also stored oil in seal skins (Anichtchenko 2016), further complicating the identification of oil storage from the archaeological record.

Some pitch imprints might also give evidence that the technology needed to build sewn boats was present in Scandinavia at a very early date. At the Early Mesolithic site of Huseby Klev in Bohuslän several pitch fragments have been found that show clear imprints from wooden planks sewn together (Nordqvist 2005). This shows that the use of pitch to waterproof seams has great antiquity in the Nordic region. The Huseby Klev pitch fragments have been interpreted as coming from frames for steam expanded dugout boats due to a lack of other known boat types from the time period (Nordqvist 2005). We suggest, however, that an alternate possibility could be waterproofing large wood frames for an Umiak like skin boat. In any case, it clearly shows that the concept of sewing together materials to construct boats existed in Scandinavia already during the Early Mesolithic, suggesting that the use of skin boats by Neolithic people would not have been an especially radical deviation from already existing technologies.

Discussion

Our approach to understanding the seafaring technologies of the PWC was to ask what types of boats would have been needed to carry out the activities visible in the archaeological record. Throughout this paper we have focussed on the question of whether evidence exists for the use of skin boats by the PWC. However, faced with the scarcity of intact boat finds for the Middle Neolithic, we were forced to look to indirect and fragmentary evidence to understand what types of maritime technology were used by the PWC. We discussed the location of settlements and the subsistence economy as strong indicators of a maritime lifestyle that was not confined to only near-shore activity. That was supported by long distance contacts, for example, between Gotland and Åland. The “Inuit of the Baltic” (Eriksson 2004, 154) set out to sea regularly, and at least occasionally organized long-distance and open-ocean voyages (Price et al. 2021; Boethius et al. 2024).

Comparisons to ethnographically known maritime cultures around the world indicate that while dugout craft are highly capable for near-shore voyages, they are dangerous when used for longer trips in the open sea (Fauvelle and Montenegro 2024). As we know that PWC people undertook such voyages, it seems highly likely that they used more advanced craft than simple logboats for these trips. Based on our comparison with the ethnographic and anthropological record, we have suggested that skin boats similar to those used by the Inuit are the most likely candidates for open-ocean watercraft technology used by the PWC. With this we were able to open our interpretive lens to examine diverse categories of evidence including the re-interpretation of some potential fragments of skin boats from Ragunda, Grundsunda, and Sävholm that have previously been interpreted as blades for sleighs (Marnell 1996; Jansson 2004), but that could rather have been the keels for skin boat frames due to their rounded bottom and lack of use-wear. Taken together we demonstrate that several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that skin boats were used by the PWC in tandem with other boat technology. However, considering the fragmentary nature of this evidence we do not propose to definitively prove the use of any specific boat type by Middle Neolithic peoples.

Some of the best evidence of the use of skin boats by ancient Scandinavians comes from possible depictions of these boats in rock art. Rock carvings at the site of Alta in Norway dating to between 5000 and 3000 BCE contain numerous boats depicting elk heads, which have been suggested as possible skin boats (Lindqvist 1983; Helskog 2014; Gjerde 2015, 2021). To this we added an analysis of the length to width ratios of these boat depictions and compared them with ethnographically known vessels. We found that the dimensions of the Alta boat carvings correlate with ethnographic Umiaks and especially depictions of these vessels, providing additional evidence that these carvings might depict skin boats. Of course, this work needs to be expanded in the future to provide a comprehensive overview of the types of vessels that have been depicted. However, together with the other evidence presented in this paper, this provides a strong indication that skin boats were used by ancient Scandinavians.

Indirect evidence comes from the faunal assemblage of the PWC which indicates a highly marine diet, as well as artifact assemblages that include the needed tools for building and maintaining sewn boats. Pitch imprints from Huseby Klev also show evidence of planks being sewn together to construct composite boats during Mesolithic times (Nordqvist 2005). While we do not know exactly what type of boats were being used at Huseby Klev, these pitch finds show that the prerequisite concepts for sewn boat technology already existed during the late Mesolithic. When combined with evidence of abundant skin processing, potential rock art depictions, possible boat frame fragments, and strong ethnographic parallels from similar societies around the world, the case for the use of skin boats by PWC peoples becomes too compelling to ignore. In addition, considering the sheer number of hunted seals, seal skin processing, and the utilisation of seal oil, we propose that seal products played an essential role in building boats and that the majority may even have been seal skin boats.

If PWC people did use skin boats, the question remains as to why the technology may not have survived into the period of recorded history. The most likely answer is that sewn skin boats were replaced by sewn plank boats during the Bronze Age. Sewn plank boats were already being used in Egypt by 2500 BCE and were in use in Britian by around 2000 BCE (Lipke 1985; Wright 2014). Considering the evidence of strong interaction between Scandinavia and both the Mediterranean world and the British Isles during the Bronze Age (Ling et al. 2014), it is highly likely that sewn plank boat technology arrived in Scandinavia soon after the end of the Neolithic. As the concept of sewing together materials to make boats was not new to the region, i.e. the Huseby Klev pitch fragments, sewn plank technology likely spread rapidly, perhaps replacing any skin boats that were in use. Potential evidence for this transition can be found in ratios of seal oil to pine pitch on ceramic vessels, with seal oil (used to waterproof skin boats) dominating during the Neolithic and pitch (required to waterproof plank boats) becoming more common in the Bronze Age (Isaksson 2009, p. 138). However, some evidence exists that skin boats may not have died out completely during the Bronze Age with evidence for the possibility that horse skin boats may have been utilised (Horn et al. 2024). Sewn plank-built boats continued to be used in Scandinavia well into modern times (Westerdahl 1985), showing the longevity of sewn boat technology in the Nordic region.

Conclusions

In this paper we have provided a framework for analysing ancient boat technology when faced with a lack of intact boat finds in the vein of Glørstad (2013a). By drawing broadly from multiple lines of evidence we have built a case for the use of (seal) skin boats by the PWC of the Middle Neolithic in Scandinavia. We believe that a combination of evidence from fragmentary wood finds, rock art depictions, tool types, tar imprints, and ethnographic comparison show that skin boats are the most likely candidate for the type of watercraft used when PWC voyaged into the open ocean. We argue that skin boats likely complemented other boat types, such as dugout canoes, that would have been used for river, fjord, and near-shore activities. Toward the end of the Neolithic, sewn skin boats would have been replaced by sewn plank boats; a technology that persisted in the region until modern times.

Maritime archaeology in Stone Age contexts presents a considerable interpretive challenge as organic artifacts such as boats rarely last for thousands of years in high-energy environments such as coasts and beaches. While we may never be able to “prove” that skin boats were used by Neolithic people in ancient Scandinavia, we hope that the approach presented here provides compelling evidence of their probable use. Hopefully, future investigations will continue to shed light on Neolithic boat technology in Scandinavia, either through the discovery of more boat fragments or through new scientific methods such as agent-based digital voyage modelling. By combining diverse lines of evidence, we can continue to expand our understanding of the maritime technologies of one of Scandinavia’s first seafaring societies.

Data Availability

This manuscript does not report data generation or analysis.

Notes

Information from https://www.fishbase.se/.

References

Adney ET, Chapelle HI (2007) Bark canoes and skin boats of North America. Skyhorse Publishing Inc, New York

Ahlström T, Price TD (2021) Mobile or stationary? An analysis of strontium and carbon isotopes from Västerbjers, Gotland, Sweden. J Archaeol Sci Rep 36:102902

Alvå J (2024) Maritime encounters in the Neolithic. A study of pitted ware maritime technology using rock art. MA thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg

Ames KM (2002) Going by boat: the forager-collector continuum at sea. In: Fitzhugh B, Habu J (eds) Beyond foraging and collecting: evolutionary change in hunter-gatherer settlement systems. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, pp 19–52

Andersson M, Artursson M, Brink K (2016) Early neolithic landscape and society in Southwest Scania–new results and perspectives. J Neolit Archaeol 18:23–114. https://doi.org/10.12766/JNA.V18I0.118

Anichtchenko E (2012) Open skin boats of the Aleutians, Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound. Études/inuit/studies 36:157–181

Anichtchenko E (2016) Open passage ethno-archaeology of skin boats and indigeneous maritime mobility of North-American Arctic. PhD Thesis, University of Southampton

Artursson M, Björck N, Lindberg K-F (2023) Seal hunters, fishermen and sea-voyagers: late middle neolithic (2600–2400 cal BC) maritime hunter-gatherers in the Baltic Sea archipelago at Tråsättra, Sweden. J Neolit Archaeol 2023:89–147

Bang-Andersen S (2013) Missing boats–or lacking thoughts? Nor Archaeol Rev 46:81–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2013.777099

Bardi U, Perissi I (2021) The empty sea: the future of the blue economy. Springer, Cham

Bengtsson B (2015) Sailing rock art boats: a reassessment of seafaring abilities in bronze age Scandinavia and the introduction of the sail in the north. PhD Thesis, University of Southampton

Berg G (1934) En 5000-årig släde från Ragunda. Jämten 77

Bird MI, Condie SA, O’Connor S et al (2019) Early human settlement of Sahul was not an accident. Sci Rep 9:8220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42946-9

Bjerck HB (2017) Settlements and seafaring: reflections on the integration of boats and settlements among marine foragers in Early Mesolithic Norway and the Yámana of Tierra del Fuego. J Isl Coast Archaeol 12:276–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2016.1190425

Boethius A, Storå J, Gustavsson R, Kielman-Schmitt M (2024) Mobility among the stone age island foragers of Jettböle, Åland, investigated through high-resolution strontium isotope ratio analysis. Quat Sci Rev 328:108548

Bradley R (2008) Ship settings and boat crews in the Bronze Age of Scandinavia

Brorsson T, Blank M, Fridén IB (2018) Mobility and exchange in the middle neolithic: provenance studies of pitted ware and funnel beaker pottery from Jutland, Denmark and the west coast of Sweden. J Archaeol Sci Rep 20:662–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.06.004

Browall H (1986) Alvastra pålbyggnad.: Social och ekonomisk bas. Theses and papers in North European 15. Kungliga Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, Stockholm

Browall H (2011) Alvastra pålbyggnad: 1909–1930 års utgrävningar. KVHAA:s Handlingar, Antikvariska serien 48. Kungliga Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, Stockholm

Browall H (2016) Alvastra pålbyggnad: 1976–1980 års utgrävningar. Västra schaktet. KVHAA:s Handlingar, Antikvariska serien 52. Kungliga Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, Stockholm

Browall H (2020) Stenålder vid Tåkern. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien

Burenhult G, Brandt B (2002) The grave-field at Ajvide. Remote Sens 2:31–167

Christensen C (1990) Stone Age dug-out boats in Denmark: occurrence, age, form and reconstruction. Exp Reconstr Environ Archaeol 119–141

Clark JGD (1946) Seal-hunting in the stone age of North-Western Europe: a study in economic prehistory. Proc Prehist Soc 12:12–48

Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B et al (2017) Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago. Nature 547:306–310

Coutinho A, Günther T, Munters AR et al (2020) The Neolithic Pitted Ware culture foragers were culturally but not genetically influenced by the Battle Axe culture herders. Am J Phys Anthropol 172:638–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24079

Crumlin-Pedersen O, Olsen O (2002) The Skuldelev Ships 1. Ships Boats North 4

Crumlin-Pedersen O, Trakadas A (2003) Hjortspring: a pre-Roman Iron-Age warship in context. Viking Ship Museum, Oslo

Crumlin-Pedersen O (2003) The Hjortspring boat in a ship-archaeological context. In: Hjortspring: a pre-roman iron-age warship in context, Viking Ship Museum, Roskilde, pp 209–232

Davis LG, Madsen DB (2020) The coastal migration theory: formulation and testable hypotheses. Quat Sci Rev 249:106605

Des Lauriers MR (2005) The watercraft of isla cedros, baja California: variability and capabilities of indigenous seafaring technology along the Pacific coast of North America. Am Antiq 70:342–360

Ekman J (1974) Djurbensmaterialet från stenålderslokalen Ire, Hangvar sn, Gotland. GO Janzon Gotlands Mellanneolitiska Gravar Stud North-Eur Archaeol 6:212–246

Eriksson G (2004) Part-time farmers or hard-core sealers? Västerbjers studied by means of stable isotope analysis. J Anthropol Archaeol 23(2):135–162

Erlandson J, Moss M, Des Lauriers MR (2008) Life on the edge: early maritime cultures of the Pacific Coast of North America. Quat Sci Rev 27:2232–2245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.08.014

Erlandson JM, Rick TC, Braje TJ et al (2011) Paleoindian seafaring, maritime technologies, and coastal foraging on California’s channel Islands. Science 331:1181–1185. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201477

Evans E (1943) Irish heritage: the landscape, the people and their work. Geogr Rev 33:173

Fauvelle M (2011) Mobile mounds: asymmetrical exchange and the role of the tomol in the development of chumash complexity. Calif Archaeol 3:141–158

Fauvelle M (2014) Acorns, asphaltum, and asymmetrical exchange: invisible exports and the political economy of the Santa Barbara channel. Am Antiq 79:573–575

Fauvelle M, Sasaki S, Jordan P (2024) Maritime technologies and coastal identities: seafaring and social complexity in Indigenous California and Hokkaido. Indig Stud Cult Divers 1(2):30–52

Fauvelle M, Alvaro M (2024) Do stormy seas lead to better boats? Exploring the origins of the southern Californian plank canoe through ocean voyage modeling. J Island Coast Archaeol 1–21

Ferentinos G, Gkioni M, Geraga M, Papatheodorou G (2012) Early seafaring activity in the southern Ionian Islands, Mediterranean Sea. J Archaeol Sci 39:2167–2176

Fitzpatrick SM (2013) Seafaring capabilities in the pre-Columbian Caribbean. J Marit Archaeol 8:101–138

Fletcher P (2015) Discussions on the possible origin of Europe’s first boats-11,500 BP. Atti Della Accademia Peloritana Dei Pericolanti-Classe Di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche e Naturali 93:2

Gamble LH (2002) Archaeological evidence for the origin of the plank canoe in North America. Am Antiq 67:301–315

Gibaja JF, Mineo M, Santos FJ et al (2024) The first neolithic boats in the Mediterranean: the settlement of La Marmotta (Anguillara Sabazia, Lazio, Italy). PLoS ONE 19:e0299765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299765

Gjerde JM (2010) Rock art and landscapes: studies of Stone Age rock art from northern Fennoscandia

Gjerde JM (2015) A stone age rock art map at Nämforsen, northern Sweden. Adoranten 74

Gjerde JM (2021) The earliest boat depiction in Norther Europe: newly discovered early mesolithic rock art at Valle, Northern Norway. Oxf J Archaeol 40:136–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/ojoa.12214

Gjessing G (1938) Der Küstenwohnplatz in Skjåvika. Ein neuer Fund aus der jüngeren Steinzeit der Provinz Finmarken. Acta Archaeologica 9(3):177–204

Glørstad H (2013a) Where are the missing boats? the pioneer settlement of norway as long-term history. Nor Archaeol Rev 46:57–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2013.777095

Glørstad H (2013b) Reply to comments from Sveinung Bang-Andersen, Hein B. Bjerck, Clive Bonsall, Catriona Pickard, Peter Groom, Vicki Cummings, Berit Valentin Eriksen, Ingrid Fuglestvedt, Peter Rowley-Conwy, Roger Wikell and Mattias Pettersson. Nor Archaeol Rev 46:101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2013.777104

Gorman LM, Judge SJ, Fezai M, Jemaà M, Harris JB, Caldwell GS (2020) The venoms of the lesser (Echiichthys vipera) and greater (Trachinus draco) weever fish: a review. Toxicon X 6:100025

Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N et al (2015) Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522:207–211

Hallgren F (2008) Identitet i praktik: lokala, regionala och överregionala sociala sammanhang inom nordlig trattbägarkultur. PhD Thesis, Arkeologi

Helskog K (2014) Communicating with the world of beings: the World Heritage rock art sites in Alta. Oxbow Books, Arctic Norway

Hoffman WJ (1897) The graphic art of the Eskimos: based upon the collections in the National Museum. AMS Press, New York

Högberg A (2004) The use of flint during the south Scandinavian late bronze age: two technologies, two traditions. In: Walker EA, Wenban-Smith FF, Healy F (eds) Lithics in action: papers from the conference Lithic studies in the year 2000. Oxbow, Oxford, pp 229–242

Horn C (2022) Most deserve to be forgotten: could the Southern Scandinavian rock art memorialize heroes? In: Zubieta LF (ed) Rock art and memory in the transmission of cultural knowledge. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 125–146

Horn C, Austvoll KI, Ling J, Artursson M (2024) Nordic bronze age economies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hornell J (2014) Water transport: origins and early evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hudson T, Blackburn TC (1979) The material culture of the Chumash interaction sphere, volume I: food procurement and transportation. Ballena Press, Los Altos

Hudson T, Timbrook J, Rempe M (1978) Tomol: Chumash watercraft as described in the Ethnographic Notes of John P. Harrington. Ballena Press, Socorro

Isaksson S (2009) Vessels of change: a long-term perspective on prehistoric pottery use in southern and eastern middle Sweden based on lipid residue analyses. Curr Swed Archaeol 17:131–149

Iversen RH (2015) The transformation of Neolithic societies: an eastern Danish perspective on the 3rd millennium BC. Jutland Archaeol Soc

Iversen R, Philippsen B, Persson P (2021) Reconsidering the pitted ware chronology: a temporal fixation of the Scandinavian Neolithic hunters, fishers and gatherers. Praehistorische Z 96:44–88. https://doi.org/10.1515/pz-2020-0033

Jansson S (2004) Norrländska fynd med belysning på hällristningstid. Botnisk Kontakt 101–112

Janzon GO (1974) Gotlands mellanneolitiska gravar. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm

Kastholm OT (2008) Skibsteknologi i bronzealder og jernalder: nogle overvejelser om kontinuitet eller diskontinuitet. Fornvännen 103:165–175

Kastholm OT (2014) Stammebåde på den skandinaviska halvø før år 1

Kastholm OT (2015) Plankboat skeuomorphs in bronze age logboats: a Scandinavian perspective. Antiquity 89:1353–1372

Knutsson H, Knutsson K (2020) Slitspårsanalyser av utvalda föremål från slutundersökningen av den gropkeramiska boplatsen Tråsättra, RAÄ Österåker 553 i Österåkers sn i Uppland. In: Björck N, Artursson M, Lindberg K-F (Eds), Tråsättra. Aspekter på säljägarnas vardag och symbolik. Arkeologerna, Stockholm

Lanting JN (1997) Dates for origin and diffusion of the European logboat. Palaeohistoria 627–650

Larsson ÅM (2009) Breaking and making bodies and pots. Material and ritual practices in Sweden in the third millennium BC. AUN 40. Uppsala

Larsson TB, Broström S-G (2018) Nämforsens hällristningar: Sveriges största och äldsta hällristningsområde med 2 600 figurer. Nämforsens hällristningsmuseum, Näsåker

Lidén K (1996) A dietary perspective on Swedish hunter-gatherer and Neolithic populations. Laborativ Arkeol 9:5–23

Lindqvist C (1983) Arktiska hällristningsbåtar—spekulationer om kulturellt utbyte via kust-och inlansvattenvägar i Nordfennoscandia. Medd Från Mar Sällsk 6:2–14

Ling J (2014) Elevated rock art: towards a maritime understanding of Bronze Age rock art in northern Bohusl_n. Oxbow Books, Sweden

Ling J, Stos-Gale Z, Grandin L et al (2014) Moving metals II: provenancing Scandinavian Bronze Age artefacts by lead isotope and elemental analyses. J Archaeol Sci 41:106–132

Ling J, Chacon R, Chacon Y (2020) Rock art and nautical routes to social complexity: comparing Haida and Scandinavian Bronze Age societies. Adoranten 5–23

Ling J, Fauvelle M, Austvoll KI, Bengtsson B, Nordvall L, Horn C (2024) Where are the missing boatyards? Steaming pits as boat building sites in the Nordic Bronze Age. Praehistorische Zeitschrift. https://doi.org/10.1515/pz-2024-2005

Lipke P (1985) Retrospective on the royal ship of Cheops. In: Sewn plank boats: archaeological and ethnographic papers based on those presented to a conference at Greenwich in November, 1984, pp 19–34

Luik H, Choyke A, O’Connor S (2013) Seals, seal hunting and worked seal bones in Estonian coastal region in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. These bare bones raw mater study work osseous objects Oxbow Books Oxf 73–87

Luukkanen H, Fitzhugh WW (2020) The bark canoes and skin boats of Northern Eurasia. Smithsonian Institution, Washington

Makarewicz CA (2023) Extensive woodland pasturing supported pitted ware complex livestock management systems: multi-stable isotope evidence from a Neolithic interaction zone. J Archaeol Sci 158:105689

Malmer MP (2002) The neolithic of south Sweden: TRB, GRK, and STR. Akademibokhandelsgruppen AB

Malmström H, Gilbert MTP, Thomas MG et al (2009) Ancient DNA reveals lack of continuity between neolithic hunter-gatherers and contemporary Scandinavians. Curr Biol 19:1758–1762

Marnell Å (1996) Grundsundafyndet, en mede eller en köl. TI SPÅR 1995–96

Martin M (1934) A description of the Western Islands of Scotland. Orig. publ. London, 1703. Quotations from Stirling. A Bell, London