Abstract

The generation of boat and ship imagery in the form of graffiti has long precedents internationally. Such imagery carries with it a range of context-dependant associations and meanings. This paper presents a collection of previously undescribed graffiti from the north coast of Ireland which demonstrates features and behaviours which parallel those witnessed in a wide range of chronological situations elsewhere, while retaining context-specific resonances. The twelve graffiti depict a variety of eighteenth–nineteenth century sailing craft and one anchor. In addition, a series of names or initials provide a sense not only of authorship and identification with maritime communities but also the performative and thereby provocative nature of graffiti. This paper argues that the wider socio-economic changes taking place within these coastal communities provides a basis for understanding the resonance of such imagery across this period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The generation of boat and ship imagery is an international phenomenon and broad in scope, both in terms of the variety of vessels depicted and in chronological, material and functional terms (see e.g., Ballard et al. 2004; Vanhulle 2018; Nakas 2021; Pollard and Bita 2017; Lace et al. 2019; Hansen 1968). As both object and symbol, since the Medieval period, the ship has been depicted in art and literature to signify social groups and institutions, as well as personal catharsis, transformation and mortality (e.g., Classen 2013; Blumenberg 1997; Manguin 1986; Murray and Murray 1996; Munch Thye 1995). Their image on diverse archaeological media also connoted authority, commerce, memory, and a range of religious meanings from petitionary to penitent. The study of ship iconography has evolved in both method and interpretation from a tool to understand shipbuilding traditions and techniques to a broader concern with landscape and seascape, social commentary and folk perspectives (see e.g., Villain-Gandossi 1994; Friel 2011; Flatman 2004). As a folk expression, graffiti have often been regarded as within the domain of the ‘ordinary’ person’s spontaneous response to their situation and environment, in contrast to the trained artisan under the commission of a patron (e.g., Le Bon 1995). As such, graffiti have the ability to be both a personal statement and a more general reflection of contemporary conditions and in addition to the prosaic, they are an important means of capturing subversive sentiments or the experiences of the relatively powerless (Keegan 2014; Westerdahl 2013; Turner 2006; Bucherie 1992). Consequently, they have often been characterized as potentially deviant, a pejorative view of graffiti that persists today. While scholars working on graffiti acknowledge this tendency, they nevertheless continue to employ the term without acceptance of its negative connotations. Beyond the content of text or imagery, the creation of graffiti as a performative act has emphasized the relationship between the graffito, the author and contemporary audience; indeed this relationship is perpetuated by those involved in its ongoing interpretation (Baird and Taylor 2010).

Representations of boats and ships have a long history in Ireland, with a number of drawings, carvings and models appearing in multiple contexts. Notable examples of the latter include the Iron-Age Broighter hoard vessel and Viking Dublin’s wooden boats (Farrell et al. 1975; Christensen 1988). Carvings on stone include formal depictions on monuments or memorials, such as High Crosses (Harbison 1992) and tombs (e.g. Gillespie and Ó Comáin 2005). While informal examples of ship graffiti are also notably associated with ecclesiastical sites, they can additionally be found on secular monuments (see e.g., Brady and Corlett 2004; McCormick and Kastholm 2017; Breen 2012). Later examples of secular graffiti demonstrate a diversity of styles and themes. Kelleher et al. (2019) described a group of 14 craft at Derrynane, Co. Kerry. They were etched into the plasterwork of a summer house owned by the notable early 19th-century politician Daniel O’Connell. The ships depicted constitute a range of vessels in terms of size and function (single-masted fishing boats to three-masted ships). These examples were notable for their maritime action scenes, of fishing and wrecking, their range of artistic styles and the accompanying names or initials.

On the northern coasts of Ireland, a range of formal and informal depictions survive (Fig. 1). These include the early Medieval remains of the High Cross at Camus (LDY007:022), which features a depiction of Noah’s Ark, and a later Medieval highland galley (or bìrlinn) inside the gatehouse at Dunluce Castle (ANT002:003). A more recent example is the ‘Bishop in a boat’ depiction near Carndonagh, which has been added to a slab featuring prehistoric cup marks (DG011-065001). According to local folklore the ecclesiastical figure depicted standing in the crudely etched boat is Bishop of Derry, John McColgan (1702–65), and the carving memorializes the bishop’s escape from the authorities during the suppression of Catholicism under the Penal Laws (The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1116, 90–1).

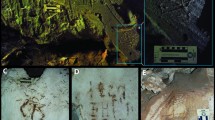

The most notable collection of post-medieval ship graffiti is that located on the Antrim coast and described during the course of the Rathlin Island maritime survey (Forsythe and McConkey 2012). The survey, which took place from 2003 to 2007, was primarily an attempt to identify and systematically describe all coastal and underwater archaeology associated with the island. It comprised field recording, remote sensing (aerial, terrestrial and underwater) and a limited program of test excavation to elucidate new findings. Sponsored by the Northern Ireland government, it built on the productive findings of previous archaeological work in the maritime landscape across Ireland (see McErlean et al. 2002; McErlean and Crothers 2007; O’Sullivan 2001, 2005). One of the challenges facing maritime archaeologists is determining the extent and boundaries of the maritime cultural landscape in coastal districts (see e.g. Westerdahl 1992). The relatively small size of the island environment mitigates this difficulty as it can be considered a maritime landscape in its entirety. Consequently, during the course of the project the survey’s scope was broadened to a re-examination of all the island’s archaeology. This comprised revisiting and reinterpreting previously documented sites, as well as fieldwalking and the interrogation of new sources of information (e.g. aerial photographs) to detect undiscovered sites. As well as enriching the archaeological record of the island generally, this decision was immediately justified by the discovery of further indisputably maritime sites, such as ship graffiti. The majority of these were known by contemporary islanders. Discovered by chance, members of the community had become enthused and even competitive about finding new examples while going about their daily work or walking for leisure. The examples of ship graffiti were found on outcrops of bedrock, field walls and blocks of stone used in dwellings. While islanders might have been aware of historical ownership or leasing of relevant holdings and buildings there was no specific folklore attached to these images and they were considered to be idle distractions on the part of those responsible for their creation. Closer inspection however revealed the imagery to be both carefully rendered and specific to their source. A range of vessels was depicted including a three-masted full-rigged ship, three schooners and a cutter or sloop and thus, vessels capable of transatlantic journeys as well as inshore transport and cargo craft (Forsythe and Breen 2012). It was clear that some had been added to and, in some cases, initials or a name had been carved adjacent to the image. From their form and context, they were dated to the eighteenth–nineteenth century with one addition as late as the early twentieth century. The publication of the Rathlin survey aroused further interest in these types of sites locally and further discoveries of ship graffiti were subsequently made. One of the more recent Rathlin discoveries, a double-masted vessel, possibly representing a brig is included in the list below (Table 1). Its gunwale features a series of vertical lines reminiscent of the full-rigged ship mentioned above (MRA003:150), however other features, such as the wave detail, are closer to elements in the collection on the opposing mainland coast. The 10 vessels and one anchor which appear near the town of Ballintoy, together with the 11 vessels on Rathlin Island represent the most numerous concentration of post-medieval ship graffiti in Ireland. This paper presents the previously undescribed examples of ship graffiti and their physical, geographical and social contexts in relation to wider developments taking place in Ireland. National and international developments inevitably impact perspectives and materiality at the local level, and they can inform interpretation of morphology and function. The period from the 1790s through the nineteenth century was one of significant social and political changes including population expansion and emigration, economic growth and recession. Underlying these developments was tension over the way Ireland was governed which saw expression in rebellion, political agitation, land dispute and the emergence of a range of non-violent strategies of resistance to authority such as boycotts. The defining event of the period was the tragedy of the Great Famine (1845–49) which saw crop collapse exacerbated by British economic and social policy as well as population pressure. The result was a loss of over two million people through starvation and emigration.

Ballintoy (Magheraboy)

A series of comparable ship carvings to those on Rathlin can be found near Ballintoy, a small town on the opposite north Antrim coast. Magheraboy townland is located one mile from Ballintoy Harbour and is most well-known from an archaeological perspective for a passage tomb (ANT004:012) known as the ‘Druid Stone’ (Mogey 1941). The townland also features a fine, three-storey Georgian rectory now occupied by the Rev Patrick Barton. Forty acres of land was donated by Alexander Stewart to the rectors of Ballintoy in 1788 and the Rev Robert Traill completed the house by 1791, naming it Mount Druid after the megalithic tomb (Brett 1996, 121). The first Ordnance Survey map of the townland (1832) shows the house with yard and four buildings to the rear—at least one of these was used as stables (Fig. 2). The walls enclosing the grounds had also been built, but according to the OS memoirs (1835) there was ‘no planting about the house’ (Day et al 1994, 15). The enclosed property includes the line of a laneway that provides access to the house, and which continues to the rear of the property inland toward Ballinlea. This was the main routeway between the coast road and the Lagavara Road before a new Ballinlea Road was built in the mid-nineteenth century. By the time the first edition map was revised in 1855, gardens had been laid out to the south west of the outbuildings at Mount Druid and the original route had been consigned to a laneway no longer used by general traffic. The focus of interest is the exterior face of the north–south enclosing wall overlooking the old Ballinlea Road to the rear of the property, which features a series of ship graffiti and one anchor etched into the predominantly basalt stone. The ship carvings on the north–south wall appear most prominently toward the northern end of the wall, but individual examples are located along its length. Inspection of the wall reveals it has been amended over time—it was originally constructed using basalt boulders and lime mortar (phase 1) in the eighteenth century. This phase contains a number of the ship carvings (see Table 1) and the date 1824. The upper courses of the northern end had been reconstructed at a later date, most likely the mid-nineteenth century (phase 2). This area also contains a number of ship carvings, including the dates 1881 and the latest date of 1918. Finally, part of the middle section of the wall has been reconstructed using recent cement pointing (phase 3), however no graffiti appear on this section (Fig. 3).

Like the Rathlin examples, the local community was aware of the graffiti and pointed archaeologists to the assemblage as one of comparable significance. The site required multiple visits to take account of the effects of weather and in particular light, as being in an outdoor location their visibility was affected by sun and shadow. In many cases the imagery was thinly incised and details could be hard to discern, especially when accompanied by background ‘noise’ in the form of natural striations or older attempts at geometric shapes or drawings. Repeat visits were useful to establish the basic assemblage and then search for more examples as conditions allowed; it also helped to see and photograph ambiguous text under different conditions and improve clarity. Interpretation and identification of individual vessels (Table 1) is based on a combination of characteristics such as hull shape, but primarily mast and sail plan. While it is possible to suggest vessel typologies, it is important to acknowledge both the restrictions of the media (e.g., scale and quality of the stone surface) and that some graffiti may be incomplete. As a result, some vessels remain ambiguous. Similarly, interpretation of text has been aided by the relatively unique (in an Irish context) survival of census documents and substitutes for this area. These provide a potential link to the local community that produced many of the graffiti, especially after the road was relegated to a laneway traversed by increasingly few travellers. Ultimately context, whether the physical media, form of vessels or broader socio-economic conditions is key to the interpretation of graffiti and its significance to the community that created it.

In addition to the boats, further stones feature various carved lines and dates—1852 and 1881 or 1884. In some places initials have been carved in proximity to the ships that may denote those responsible—RD, MED, JH, PB and RN (Table 2). The tendency to add dates and names to imagery has been associated with increased literacy levels from the later eighteenth century and this is similarly the case for the Irish education system after the 1830s (Giles and Giles 2010, 49). The names Daniel MKay (sic), Roger / May, Nancy and James also appear on the wall. A cursory examination of surviving 19th-century census records and Griffith’s Valuation (1861–2) for townlands between the site and the harbour or inland / adjacent to the road reveal a number of possible identifications for these individuals. Peggy Black of Magherboy and John Heaney of Ballintoy appear in the 1803 census; while Daniel Macay (sic) of Lemnaghbeg and Patrick Blae of Ballintoy are recorded in the 1851 census. Griffith’s Valuation notes Patrick Black of Maghernahar and Robert Dyatt of Knocknagarvan. The early twentieth century census includes Bob Donegan of Ballintoy, Maggie Donnelly of Magheraboy, Maggie Donaghy and Mary Donegan of Ballintoy in 1911. Whether these individuals are responsible for the ship carvings is speculative at this stage, and not all initials can be reconciled with historical records. Furthermore, multiple names appear in historical documents across the century that could correspond to the inscribed names or initials (Nancy and James are particularly common). Although these underscore the perils of attempting identification, they at least demonstrate that there is no reason to look beyond the locality for the artists. While those initials inscribed directly beside the ships have the strongest case for authorship, Vessel A (which features two sets of initials) demonstrates this is not straightforward in all cases. In this case the initials ‘RD’ are set above the ship, with ‘MED 1918’ underneath the vessel. The siting of RD is consistent with its position in relation to vessels C and J, and so MED is likely a later addition. Furthermore, in this case the word ‘TITANIC’ has been added across the foremast, the only example of text intruding on the imagery in this collection. Given the date of construction and loss of the famous Belfast-made liner, this must be a late addition for which ‘MED’ may be responsible (see Figs. 4 and 5).

Discussion

The primacy of contextual examination remains key to interpreting graffiti, whether comprised of imagery, text, or a combination of both. Consideration of an archaeological site within a broader physical landscape, seascape of settlement, infrastructure (maritime and terrestrial) and industry with distinct geological characteristics provides a geographical basis for understanding the imagery. Equally, chronological, historical and socio-economic processes acting on multiple scales allows for the more accurate identification of the community associated with such graffiti and provides a sense of the conditions under which it was created and might have functioned.

Although superficially crude, the graffiti are a reflection of the types of vessels plying their trade inshore and in Atlantic waters in the post-medieval period. Some sense of the variety of craft in the area is provided by Thomas Baynes’ drawing of Carrick-a-Rede, which was published in Ireland Illustrated (Wright 1831). No fewer than eight vessels appear in the scene, taken from a viewpoint east of Ballintoy north-west toward Rathlin and the Atlantic. In the foreground are small inshore boats tending the salmon fishery, while in the middle distance two cutters or sloops sail through Rathlin Sound. Finally, on the Atlantic horizon are two three-masted vessels. This range of craft is apparent in the graffiti of both Rathlin and Magheraboy. They include ocean-going ships engaged in long distance trade (barques and schooners), fast boats typically employed by naval or revenue services (cutters), and smaller freighters involved in inshore trade (smaller schooners were the work horse of the nineteenth century Irish coastal trade). The variety in scale and function of the boats depicted is due to their location on the North American shipping route for vessels leaving Belfast, Liverpool and Glasgow. They also represent vessels relevant to the locality, including those required for servicing industries such as the chalk and limestone quarries; as well as regulation in the form of the coastguard that was based at Ballintoy from the 1830s. As well as monitoring legitimate interests such as those above, the coastguard would also have been charged with checking the smuggling operations which were rife between north Antrim and Scotland in the 18th and early nineteenth centuries.

The proximity of the graffiti to Ballintoy harbour and Rathlin naturally raises the possibility that those directly engaged in marine activities were responsible for it. Boat-building in the locality was primarily focused on fishing craft, such as salmon cobles and drontheims. The latter was an open, two-masted boat whose name, a corruption of Trondheim, betrays its early eighteenth century Norwegian origins. There was a long-standing tradition of fishermen crossing to Rathlin and overnighting in the caves that dot it’s coastline. The caves were modified to incorporate spaces for sleeping and cooking and some embayments on the island were named for mainland fishing families (Forsythe and McConkey 2012). However, despite this conspicuous interaction there is little to suggest that the graffiti from Rathlin and Magheraboy were created by the same hands. Although they sometimes depict the same types of vessels, there are a number of key stylistic differences. The Rathlin vessels present only their starboard profiles, and their hulls are inclined to be more rounded than the Magheraboy examples. They also include features absent from the Magheraboy carvings, such as rudders and lying at anchor in one case. Only one includes the waterline that is common in the Magheraboy images and this site also includes the artistic embellishment of wavelets shown by vessels B and J. While names and initials do appear in two of the Rathlin examples, they are located within the hull of the ship, rather than adjacent to the depictions as at Magheraboy. Moreover, it is notable that none of the typical fishing boats of the area are clearly included among the vessels in either location. The two smaller boats that do appear in Rathlin and Magheraboy have two masts, but it would be expected that their sail plan would be more accurate. In regions where boats in use by the fishing community do appear they are accurately and creatively reproduced, for example the Yorkshire fishing coble in St Oswald’s church in England (Buglass 2021, 35). Thus the omission of such fishing boats would indicate their ubiquity and therefore disregard, or more likely that fishermen were not responsible for the graffiti. Beyond aesthetics, geography is a key consideration–neither the Magheraboy nor the Rathlin examples are located on the coastline. This can be attributed in part to practical limitations. The geology of the coastal areas associated with fishing is chalk, an unsuitable medium for carved imagery; while the hinterland and clifftops are basalt which provides a more amenable surface (particularly columnar basalt.) The locations of some of the Rathlin vessels suggested they might have been created by members of the island community charged with looking after livestock on upland pasture. This does not imply a strict dichotomy between farming and fishing as coastal communities frequently had interests in both. The Magheraboy vessels are located on the routeway from Ballintoy Harbour inland to the townland of Ballinlea, passing other small settlements on the way. These settlements were dominated by farmers and labourers, but in some cases occupations such as sailors, carpenters and masons also appear on the census documents. These communities would have travelled into Ballintoy for work and a variety of goods and services, for example obtaining chalk/lime from the coastal quarries to improve the soil quality of their fields. As such they were familiar with the movements of coastal shipping and harbour activity. Like many of the Rathlin series the Ballintoy depictions are out of sight of the sea, so those responsible would have to commit the lines of hulls and rigging arrangements to memory before reproducing them, requiring a more considered study than mere casual acquaintance would permit. This is not without parallel elsewhere and speaks to an intimate familiarity with the sea on the part of maritime societies (e.g. Demesticha et al. 2017; Turner 2006; Christensen 1995). Their competent execution in stone may have been a means of demonstrating knowledge of the vessels and an invitation to others to better it in an on-going performative cycle (see e.g. Giles and Giles 2010, 50). It is not hard to imagine the majestic impression some of the largest moving structures in existence would have made on those witnessing their passage and consequently their motivation to capture them.

The phenomena of graffiti being sited on routeways by individuals engaged in work is well documented in the ancient and medieval world (see e.g. Mairs 2010; Christensen 1995). These public sites invite a response and become loci for repetition of form and text, thus perpetuating performance in the form of interaction and competition. Such interactions include examples of textual graffiti referring and responding to each other, and imagery being clustered while respecting each other (see e.g. Baird and Taylor 2010). Competition has been interpreted as attempts to improve upon former imagery or create graffiti in difficult to reach places. Some authors have also noted a tendency to ‘tag’ art that has parallels with modern graffiti (Mairs 2010). At Magheraboy there is some clustering toward the north end of the wall, but individual examples are spread along its length. Individual stones do display signs of being worked on before a vessel is completed, but once accomplished there is no overwriting of imagery, with the exception of Vessel A. The carved initials that appear (e.g. ‘PB’) may provide evidence of competition or tagging as some individuals appear in numerous locations and in direct association with the ship carvings (most notably ‘RD’). ‘RD’ appears in a consistent position in relation to the craft, despite a variation in both the way the initials are carved and the type and style of vessel depicted.

There is a well-established connection between ships and ecclesiastical sites in terms of architecture and imagery, both formal and informal. This association, stretching back to the Medieval period is considered to have a ritual aspect, albeit one that evolved over the centuries from an ex-voto appeal for protection to a means of linking sacred and daily spaces (Champion 2015; Mack 2011). In an Irish context they have been regarded as representative of the ship of the church bound for heaven or traversing heavenly seas (McGaughan 1998). Ship graffiti located on the exterior wall of a rectory garden cannot be regarded in the same manner. Despite this contrast, it is notable that the incidence of church graffiti appears to increase during periods of conflict and stress, as an act of memorialization or petition to divine beneficence (Champion 2014). The social and economic stresses of mid-nineteenth century Ireland culminated in the Great Famine of 1845–49, occasioned by the failure of the potato crop, and the north coast was not immune. In a letter to her sister (8th December 1846), Catherine Harton states “…in all Ireland there is not a poorer or more neglected place than Ballintoy, and in April last I laid out 3lbs (sic) towards setting potatoes were all solely lost being as potato ground must be paid beforehand…in counting all this it left me very little and that little is done long ago” (Thompson 2021, 3). As well as starvation, emigration was the cruel consequence of famine and one that continued at high levels for the remainder of the century. Due to the scale of dislocation Ireland experienced it may be that some of the larger ships depicted had a resonance for those losing family members and were inscribed as an act of memorialization, or were an expression of aspiration to journey westward with them (Oliver and Neal 2010, 19). However, selecting a single cultural stimulus to image-making within a short (though dynamic) period is difficult to sustain without more explicit evidence. Furthermore, the variety of vessels and multi-decadal nature of the graffiti at Magheraboy demonstrate a range of ongoing encounters with maritime life and functions. It would therefore be more meaningful to consider the longer processes at work across this period, in particular the increased external contact facilitated by maritime traffic as a consequence of Ireland’s absorption into the United Kingdom (1801) and its role as an agricultural provisioner to Britain and her overseas possessions. The emergence of recognisably modern forms of capitalism and consumerism also affected communities in the region, who were in the process of transitioning from a barter economy to using currency (Forsythe 2007). Over the period, access to new materials saw physical changes to homes (e.g. roofing materials), types of fuel employed (from turf to coal) and everyday work routines that drew the community into wider networks of contact and trade. Shipping was therefore crucial not only to economic life but to the facilitation of physical changes taking place in everyday environments and encounters. The increased exchange of goods and movement of people is arguably a more consistent factor in the creation of maritime imagery across this period, bringing as it did opportunities overseas as well as changes on a more intimate, domestic level.

The choice of the ship as a symbol can clearly embody many concepts and narratives and its repeated appearance conveys at least the depth of impression made and importance of these vessels. That such imagery was added to over time is a means of reinforcing a sense of community undergoing change through a shared motif (Sapwell and Janik 2015). As such, in addition to the common tropes of subversion and competition, ship graffiti provided a conduit in which to relate shared experiences, values and aspirations.

References

Baird JA, Taylor C (2010) Ancient graffiti in context. Routledge, New York

Ballard C, Bradley R, Myhre LN, Wilson M (2004) The ship as symbol in the prehistory of Scandinavia and Southeast Asia. World Archaeol 35(3):385–403

Blumenberg H (1997) Shipwreck with spectator: paradigm of a metaphor for existence. MIT Press, Cambridge

Brady K, Corlett C (2004) Holy ships: ships on plaster at Medieval ecclesiastical sites in Ireland. Archaeol Irel 18(2):28–31

Breen C (2012) Dunluce castle: history and archaeology. Four Courts Press, Dublin

Brett CEB (1996) Buildings of county antrim. Ulster Architectural Heritage Society and the Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast

Bucherie L (1992) Graffiti et histoire des mentalitiés, Genèse d’une recherchè. Antropol Alp Ann Rep 2:41–64

Buglass J (2021) Feet of lead; ships of lead. Pap Inst Archaeol 30(1):26–48. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.2041-9015.1284

Champion M (2014) The Graffiti Inscriptions of St Mary’s Church, Troston. Proc Suffolk Inst Archaeol 43:235–258

Champion M (2015) Medieval ship graffiti in English churches: interpretation and function. Mar Mirror 101(3):343–350

Christensen AE (1988) Ship graffiti and models. In: Wallace PF (ed) Miscellanea 1. Series B, vol 2. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, pp 13–26

Christensen AEJ (1995) Ship graffiti. In: Crumlin-Pedersen O, Munch-Thye B (eds) The Ship as Symbol in Prehistoric and Medieval Scandinavia. Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen, pp 180–185

Classen A (2013) The symbolic and metaphorical role of ships in Medieval German literature: a maritime vehicle that transforms the protagonist. Mediaevistik 25(1):15–33

Day A, McWilliams P, Dobson N (1994) Ordnance survey memoirs of Ireland: parishes of county Antrim IX, vol 24. Institute of Irish Studies, QUB

Demesticha S, Delouca K, Trentin MG, Bakirtzis N, Neophytou A (2017) Seamen on land? a preliminary analysis of medieval ship graffiti on Cyprus. Int J Naut Archaeol 46(2):346–381

Farrell AW, Penny S, Jope EM (1975) The Broighter boat: a reassessment. Ir Archaeol Res Forum 2(2):15–28

Flatman JC (2004) The iconographic evidence for maritime activities in the Middle Ages. Curr Sci 86(9):1276–1282

Forsythe W (2007) On the edge of improvement: Rathlin Island and the modern world. Int J Hist Archaeol 11(3):221–240

Forsythe W, Breen C (2012) Ship graffiti. In: Forsythe W, McConkey R (eds) Rathlin Island: an archaeological survey of a maritime landscape. TSO, Belfast. pp 299–305

Forsythe W, McConkey R (2012) Rathlin Island: an archaeological survey of a maritime landscape. TSO, Belfast

Friel I (2011) ‘Ignorant of nautical matters’? The Mariner’s Mirror and the iconography of medieval and sixteenth-century ships. Mar Mirror 97(1):77–96

Giles K, Giles M (2010) Signs of the times: nineteenth-twentieth century graffiti in the farms of the Yorkshire Wolds. In: Oliver J, Neal T (eds) Wild signs: graffiti in archaeology and history. BAR Publishing. pp 47–59

Gillespie F, Ó Comáin M (2005) The Ó Máille memorial plaque and its heraldic achievement. In: Manning C, Gosling P, Waddell J (eds) New survey of Clare Island, vol 4. The Abbey. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin

Hansen HJ (1968) Art and the seafarer: a historical survey of the arts and crafts of sailors and shipwrights. Faber and Faber, London

Harbison P (1992) The high crosses of Ireland, an iconographical and photographic survey, vol 3. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin

Keegan P (2014) Graffiti in antiquity. Routledge, London

Kelleher C, Brady K, O’Neill C (2019) Forgotten ships and hidden scripts. Archaeol Irel 33(4):30–34

Lace MJ, Albury NA, Samson AVM, Cooper J, Rodríguez Ramos R (2019) Ship graffiti on the Islands of the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos and Puerto Rico: a comparative analysis. J Marit Archaeol 14:239–271

Le Bon L (1995) Ancient ship graffiti: symbol and context. In: Crumlin-Pedersen O, Munch-Thye B (eds) The ship as symbol in prehistoric and Medieval Scandinavia. Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen, pp 172–179

Mack J (2011) The sea: a cultural history. Reaktion Books

Mairs R (2010) Egyptian ‘inscriptions’ and Greek ‘graffiti’ at El Kanais in the Egyptian Eastern Desert. In: Baird JA, Taylor C (eds) Ancient graffiti in context. Routledge, New York, pp 169–180

Manguin P-Y (1986) Shipshape societies: boat symbolism and political systems in insular Southeast Asia. In: Marr DG, Milner AC (eds) Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th centuries. Institute of Southeast Asia Studies, and Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Singapore, pp 187–215

McCaughan M (1998) Voyagers in the vault of heaven: the phenomenon of ships in the sky in Medieval Ireland and beyond. Mater Cult Rev Rev d’hist Cult Mater 48:170–180

McCormick F, Kastholm O (2017) A viking ship graffito from Kilclief, County Down, Ireland. Int J Naut Archaeol 46(1):83–91

McErlean T, Crothers N (2007) Harnessing the tides: the early Medieval tide mills at Nendrum Monastery, Strangford Lough. TSO, Belfast

McErlean T, McConkey R, Forsythe W (2002) Strangford lough: an archaeological survey of the maritime cultural landscape. Blackstaff Press, Belfast

Mogey JM (1941) The ‘Druid Stone’, Ballintoy, Co. Antrim. Ulst J Archaeol 4(1):49–56

Munch Thye B (1995) Early Christian ship symbols. In: Crumlin-Pedersen O, Munch-Thye B (eds) The ship as symbol in prehistoric and Medieval Scandinavia. Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen, pp 186–196

Murray P, Murray L (1996) The Oxford companion to christian art and architecture. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York

Nakas I (2021) Play and purpose: between mariners, pirates and priests: an introduction to the world of ship graffiti, in Medieval Mediterranean. Pap Inst Archaeol 30(1):49–59

O’Sullivan A (2001) Foragers, farmers and fishers in a coastal landscape: an intertidal archaeological survey of the Shannon estuary. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin

O’Sullivan A (2005) Medieval Fish Traps on the Shannon Estuary, Ireland: interpreting people, place and identity in Estuarine Landscapes. J Wetl Archaeol 5(1):65–77

Oliver J, Neal T (2010) Elbow grease and time to spare: the place of tree carving. In: Oliver J, Neal T (eds) Wild signs: graffiti in archaeology and history. BAR Publishing, pp 15–22

Pollard E, Bita C (2017) Ship engravings at Kilepwa, Mida Creek, Kenya. Azania Archaeol Res Afr 52(2):173–191

Sapwell M, Janik L (2015) Making community: rock art and the creative acts of accumulation. In: Berge R, Lingaard E, Stuedal HV, Steberglokken H (eds) Ritual landscapes and borders within rock art research. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 47–58

Thompson M (2021) A Snapshot of the Famine in Ballintoy. Glynns 48:1–5

Turner G (2006) Bahamian ship graffiti. Int J Naut Archaeol 35(2):253–273

Vanhulle D (2018) Boat symbolism in predynastic and early dynastic Egypt: an ethno-archaeological approach. J Anc Egypt Interconnect 17:173–187

Villain-Gandossi C (1994) Illustrations of ships: iconography and interpretation. In: Unger RW (ed) Cogs Caravels and Galleons: the sailing ship 1000–1650. Conway Maritime, pp 169–175

Westerdahl C (1992) The maritime cultural landscape. Int J Naut Archaeol 21(1):5–14

Westerdahl C (2013) Medieval carved ship images found in Nordic churches: the poor man’s votive ships? Int J Naut Archaeol 42(2):337–347

Wright GN (1831) Ireland illustrated: from original drawings by W.H. Bartlett, G. Petrie & T.M. Baynes. Fisher, London

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Michael Cecil and Douglas Cecil on Rathlin; and Robert Corbett, Reverend Patrick Barton, Maurice McHenry, and Conor Forsythe at Ballintoy. Also Rosemary McConkey, Kieran Westley and Sandra Henry in the Centre for Maritime Archaeology. Thanks to the Northern Ireland Environment Agency for their continued support, in particular Tony Corey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The paper is single-authored (WF) and all figures were prepared by WF, with the exception of Fig. 5, a photograph taken by TC as indicated in the caption.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Forsythe, W. Post-medieval Ship Graffiti on the North Coast of Ireland. J Mari Arch 18, 255–268 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-023-09362-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-023-09362-7