Abstract

Purpose

Cases of iron intoxication are not very often encountered in toxicology practice, and most of those reported concern accidental intoxications with iron supplements in young children. The paper presents a rare case of a suicide by intoxication in an adult woman who ingested a solution of iron (III) chloride.

Methods

A forensic was at the Department of Forensic Medicine, PMU in Szczecin. Toxicology tests of blood sampled from the deceased were performed using a 644 CIBA CORNING ion selective analyzer and proprietary reagent kits. Histopathological was with the use of the standard staining protocol (hematoxylin and eosin) and staining specific for iron (Prussian blue).

Results

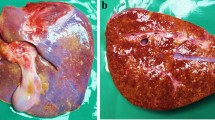

Autopsy revealed a distinct yellow discolouration and thrombotic necrosis of the oral mucosa and almost the whole gastrointestinal tract, as well as similar changes in the adjacent internal organs. Considerably high levels of iron and chloride ions were detected in specimens of internal organs preserved during autopsy. Histopathological analysis performed with the use of staining specific for iron (Prussian blue) also confirmed the presence of iron in the examined tissues, especially in the intestines and liver.

Conclusions

Considering the above findings, it was concluded in the forensic report that the death of the woman was caused by the ingestion of iron chloride. The reported case of fatal intoxication is one of the few described in the literature, and its course implies that in the case of initially diagnosed intoxication with corrosive compounds, the possibility of using metal-containing poison should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. In addition to routine toxicological tests performed in fatal cases we also draw attention to the possibility of using specific staining protocols for microscopic specimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past, both chronic and acute metal intoxication were more common. At that time, toxic metals were also used to commit crimes. In the late nineteenth century, poisoners could no longer evade justice because of advances in basic sciences and the rapid development of diagnostic toxicology. Currently, iron is the main metal of interest to clinical toxicologists. It is an essential element and it is widely supplemented in diets due to its frequent deficiencies. In everyday practice toxicologists basically focus on pharmaceutical products containing iron, and cases of intoxication are almost exclusively reported in children [1]. Intoxications with iron in other circumstances are very rare and usually not discussed in monographs on toxicology. The case of intoxication with a non-pharmaceutical iron compound that we report here was unusual and worth presenting in detail.

Case summary

The body of a woman, 47 years old, was found in her private apartment. The body lay on the floor, which was stained with yellow liquid. Yellowish discolouration was also noted on the skin around the mouth of the deceased and on her clothing (Figs. 1, 2). The deceased had a history of psychiatric treatment for paranoid schizophrenia, the deterioration of her mental state and planned further hospitalization, as well as previous multiple suicide attempts (e.g., drug overdose in combination with the ingestion of sodium hypochlorite NaOCl—Domestos, ingestion of the electrolyte paste from R20 batteries, cutting veins, etc.), a suicide attempt was suspected from the very beginning.

The intoxication was most likely caused by iron (III) chloride used by the husband of the deceased for etching a laminate, because he found this substance missing. A forensic autopsy performed at the Department of Forensic Medicine, PMU in Szczecin few days after death revealed distinct yellow discolouration and thrombotic necrosis of the oral mucosa and almost the entire gastrointestinal tract (including the colon), as well as the discolouration of the adjacent internal organs (including the heart, lungs, diaphragm, and liver). There was no gastric content noted during forensic autopsy. Our suspicion was that gastric content had been totally absorbed via the wall of the gastrointestinal tract and structures of the adjacent organs. Toxicology tests of blood sampled from the deceased were negative for ethyl alcohol and exogeneous non-volatile organic compounds. Considerably high levels of iron and chloride ions were detected in specimens of internal organs preserved during autopsy, which confirmed intoxication with iron (III) chloride (Table 1).

These tests were carried out using a 644 CIBA CORNING ion selective analyzer and proprietary reagent kits. Histopathological analysis performed with the use of the standard staining protocol (haematoxylin and eosin) and staining specific for iron (Prussian blue) also confirmed the presence of iron in the examined tissues, especially in the intestines and liver (Figs. 3, 4). To underline the severity of changes identified in the internal organs of the deceased, it is important to realize that slides of the normal liver stained with Prussian blue will not present positive reaction (blue color) at all. Even in cases of the pathological processes with accumulation of iron (as hemosiderin) in the liver positive reaction with Prussian blue, only for part of hepatocytes is noted [2]. In a forensic report including information gathered during investigation, findings from autopsy and additional tests, it was concluded that the direct cause of death of the woman was oral intoxication with iron (III) chloride followed by acute cardiorespiratory failure.

Discussion

Currently, acute intoxication with iron is most frequently reported in young children and is caused by the ingestion of tablets rich in iron (> 20 mg Fe/kg b.w.). This type of intoxication is most frequently described in the literature. The most common symptoms of poisoning with products containing iron include vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and in severe cases hypotension, metabolic acidosis, fluctuations in blood glucose levels, dehydration, coagulopathies, liver and kidney injury, as well as injuries to the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system [1]. Of course, victims also suffer damage to the gastrointestinal tract, which is due to the direct corrosive effect of iron compounds on the gastrointestinal mucosa [3, 4]. Treatment of iron poisoning is generally limited to gastric lavage, in some cases combined with the infusion of deferoxamine, but more aggressive therapies are also possible [5, 6]. Tablets ingested in large number by patients can be removed surgically [7, 8]. Iron intoxication has also been reported in pregnant women taking iron supplements [9]. Other intoxications, especially in adults, are rare and are caused by accidental or deliberate ingestion of substances containing iron. A very small number of case reports on poisoning caused by non-pharmaceutical iron chloride have been published, and some of them concern fatal cases [10,11,12]. There have also been reports of a transdermal toxic effect of iron originating from tattoo ink [13]. The fatal intoxication with iron chloride reported here resulted in severe corrosive damage to the walls of the gastrointestinal tract and the internal organs, and additionally a significant quantity of iron ions migrated to the blood, and then to many internal organs, which was confirmed by toxicology tests. Anhydrous iron (III) chloride undergoes hydrolysis to give a strongly acidic (with pH approximately 1–2) characteristically yellow liquid [14]. And it was an immediate cause of the thrombotic necrosis noted during the autopsy. Due to the fatal nature of intoxication and the time that elapsed between the death and autopsy, the potential post-mortem migration of iron via the damaged walls of the gastrointestinal tract to the adjacent organs, as indicated by autopsy findings and histopathology tests, should be taken into consideration. The reported case of fatal intoxication with iron chloride is one of the few described in the literature, and its course implies that in initially diagnosed intoxication with corrosive compounds, the possibility of the use of metal-containing poison should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. In addition to routine toxicological tests done in fatal cases, we also draw attention to the possibility of using specific staining protocols for microscopic specimens.

References

Banner W, Tong T (1986) Iron poisoning. Pediatr Clin N Am 33(2):393–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3955(16)35010-6

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2005) Robbins and Cotram pathologic basis of disease, 7th edn. Elsevier Saunders, pp 908–910 (ISBN 0-8089-2302-1)

Majdanik S, Sokala T, Potocka-Banaś B (2011) Zatrucie żelazem u małego dziecka jako poważny problem toksykologiczny - opis przypadku. J Elem 16:31

Chang D, Bruns D, Spyker D, Apesos J, Edlich R (1988) Fatal transcutaneous iron intoxication. J Burn Care Rehabil 9:385–388. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004630-198807000-00013

Cheney K, Gumbiner C, Benson B, Tenenbein M (1995) Survival after a severe iron poisoning treated with intermittent infusion of deferoxamine. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 33:61–66. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563659509020217

Fircanis S, Shields R, Castillo J, Mega A, Schiffman F (2012) The girl with the iron tattoo. Virulence 3:599–600. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.22122

Juurlink D, Tenenbein M, Koren G, Redelmeier D (2003) Iron poisoning in young children: Association with the birth of a sibling. Can Med Assoc J CMAJ 168:1539–1542

Sane M, Malukani K, Kulkarni R, Varun A (2018) Fatal iron toxicity in an adult: clinical profile and review. Indian J Crit Care Med 22:801–803. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_188_18

Lacoste H, Goyert G, Goldman L, Wright D, Schwartz D (1992) Acute iron intoxication in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol 80:500–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(93)90211-e

Pestaner J, Ishak K, Mullick F, Centeno J (1999) Ferrous sulfate toxicity: a review of autopsy findings. Biol Trace Elem Res 69:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02783871

Knott L, Miller R (1978) Acute iron intoxication with intestinal infarction. J Pediatr Surg 13:720–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3468(78)80120-1

Chen M, Lin J, Liaw S, Bullard M (1993) Acute iron intoxication: a case report with ferric chloride ingestion. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi Taipei 52:269–272

Sipahi T, Karakurt C, Bakirtas A, Tavil B (2002) Acute iron ingestion. Indian J Pediatr 69:947–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02726009

Housecroft CE, Sharpe AG (2012) Inorganic chemistry, 4th edn. PEARSON Prentice Hall, pp 618–619 (ISBN 978-0-273-74275-3)

Acknowledgements

We are most thankful for the District Court Goleniów, Dworcowa 2, 72100, Goleniów, (Poland) that has approved publication of this case report.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; data curation; resources. BP-B: project administration; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft. SG: formal analysis; writing—review and editing; validation. KB: formal analysis, resources; project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Prosecutor of District Court Goleniów (Poland) granted permission to access the case file and to publish the case.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Majdanik, S., Potocka-Banaś, B., Glowinski, S. et al. Suicide by intoxication with iron (III) chloride. Forensic Toxicol 39, 513–517 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-021-00579-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-021-00579-6