Abstract

Purpose

The presence of organic matter in cohesive sediment results in the formation of clay-organic flocs, which eventually impart complex rheological behavior including shear-thinning, viscoelasticity, thixotropy and two-step yielding to mud. In this study, the influence of microbial degradation of sediment organic matter on the rheological properties of mud samples, having similar densities, was examined.

Materials and methods

Mud samples were collected from three different locations in the Port of Hamburg, Germany, displaying varying organic matter content. The rheological analysis of fresh and degraded mud samples was performed with the help of several tests including stress ramp-up tests, amplitude sweep tests, frequency sweep tests, time-dependent tests, and structural recovery tests.

Results and discussion

The results showed a significant decrease in rheological properties including yield stresses, complex modulus, etc. for degraded mud samples as compared to the fresh mud samples. The slopes of the line, correlating the change (degraded − fresh) in the above-mentioned rheological properties as a function of the same rheological property of the fresh mud, varied within the range of −0.28 to −0.49. The structural recovery tests displayed a better recovery (i.e., stronger system) in mud after the pre-shearing step for the degraded mud samples as compared to the fresh mud samples. The effect of degradation time on the rheological properties of mud samples showed two critical time periods (3 days and 150 days) after which a significant change in rheological properties of mud samples was observed.

Conclusions

This study provided a useful understanding about the influence of organic matter degradation on the rheological properties of mud, which can be used to optimize sediment management strategies in ports and waterways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Cohesive sediments (mud) typically consist of varying amounts of clay, silt, fine sand, and organic matter. Organic matter (OM) in water–sediment systems originates from (i) natural sources including plant litter, eroded topsoils, pelagic and planktonic biomass, or (ii) anthropogenic sources such as surface runoff and urban sewage, as listed in Zander et al. (2020). Organic matter can be either suspended in the water phase, either as pure organic matter or bound to fine and still suspended mineral particles, or is bound to the already settled sediment. In suspensions, organic matter can interact with clay particles either by creating bridges between the particles or by charge neutralization (Lagaly and Dékány 2013), forming a flocculated system. Extensive research has been conducted on the measurements of floc size and settling rates in the laboratory for fine-grained sediments or sand/mud mixtures (Spearman and Manning 2017; Deng et al. 2019, 2021; Chassagne and Safar 2020; Chassagne 2021; Chassagne et al. 2021). The presence of these clay-organic flocs typically results in a complex rheological fingerprint of mud, including shear thinning, viscoelasticity, thixotropic behavior and two-step yielding (Coussot 1997; Van Kessel and Blom 1998; Shakeel et al. 2020d, b). For instance, a significant increase in rheological properties (i.e., yield stresses, moduli, thixotropy, etc.) was observed for mud samples having higher organic matter content, which may be attributed to the formation of stronger and higher number of clay-organic flocs (Shakeel et al. 2019).

Under anaerobic conditions, the microbial degradation of sediment organic matter results in the formation of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). These greenhouse gases are either released through the water column or remain entrapped in the mud layers. Entrapped gas bubbles are found to affect the density of mud and to be responsible for delayed consolidation. Given the role of clay-organic flocs for the rheological and cohesive properties of mud (Tolhurst et al. 2002; Wurpts and Torn 2005; Malarkey et al. 2015; Schindler et al. 2015; Parsons et al. 2016; Shakeel et al. 2019), it is hypothesized that the degradation of organic matter can significantly influence the rheological fingerprint of mud (as it weakens the mud). For the investigation area, Zander et al. (unpublished data) have shown that the organic matter present in the sediment can be separated into differently degradable pools based on their degradation kinetics and corresponding half-lives. However, a systematic analysis of the hypothesized effect of organic matter degradation on rheological properties is still missing.

Therefore, the following research questions are addressed in this study: is there any significant influence of degradation of organic matter on the rheological properties of fine-grained sediments? Is this effect of organic matter degradation similar for different rheological properties (such as yield stress and moduli)? What is the effect of degradation time on the rheological properties of mud? To this end, the rheological properties of freshly sampled and thereafter further microbially degraded mud of similar densities, collected from three different locations of the Port of Hamburg, Germany, were analyzed. Rheological tests included stress ramp-up tests, amplitude sweep tests, frequency sweep tests, time-dependent tests, and structural recovery tests. In the first part of study, the rheological analysis of fresh samples and samples degraded for 250 days was compared, while in the second part, the effect of degradation time on the rheological properties was studied.

2 Experimental methods

Mud samples were collected from three locations — Köhlfleet Hafen (KH), Rethe (RT) and Reiherstieg Vorhafen (RV) (Fig. S1; Table S1; see Supplementary information) — of the Port of Hamburg, Germany, using a 1-m core sampler. Based on previous studies (Zander et al. 2020; Shakeel et al. 2021a), these locations were selected to cover a range of organic matter contents (Table S1). Directly after sampling, the core was divided into sublayers such as fluid mud, pre-consolidated and consolidated sediments, based on their visual strength and consistency. However, in this study, only pre-consolidated sediment (PS) (i.e., similar densities) was considered for rheological analysis. The sediment properties along with the rheological properties of other mud layers are reported in Zander et al. (2022).

2.1 Water content and bulk density

The dry density (\({\rho }_{s}\)) of the mud samples was measured using a gas pycnometer (ISO 17892–3:2015) and found to be within the range of 2375–2534 kg m−3. The bulk density \(\rho\) of the mud samples was then estimated by determining the content of water/solids after drying at 105 °C for 24 h (ISO 11465:1993). The change in excess bulk density (\(\rho -{\rho }_{w}\)), obtained by the difference between excess bulk density of degraded and fresh mud samples is plotted as a function of excess bulk density of fresh samples, where \({\rho }_{w}\) is the density of water (Fig. S2). It is seen that the change in bulk density incurred during the long-term (250 days) incubation to degrade organic matter was lower than 5% of its original value. It was, therefore, assumed that changes in rheological properties between fresh and degraded samples were not related to the change in density or water content.

2.2 Degradation of organic matter

For the analysis of organic matter degradation under anaerobic conditions (typically prevailing in the investigated sediments; Zander et al. 2020), 200 g of fresh mud was placed into 500 ml air tight glass bottles. The headspace above the sample was flushed with N2 to establish anaerobic conditions and incubated at 36 °C in the absence of light for 250 days. All the samples were incubated in triplicate. Anaerobic carbon release was calculated from the increase in headspace pressure in combination with gas chromatographic analyses of headspace composition. The share of CO2-C dissolved in the aqueous phase was calculated using the CO2 concentration and the pressure in the bottle headspace and the temperature-corrected solubility of CO2 in water as given by Henry’s constant (Sander 2015). Further details are reported in Zander et al. (2022).

2.3 Impact of degradation time on rheological properties

In addition to the fixed degradation time of 250 days, the influence of varying degradation time on the rheological properties of mud was studied by parallel incubation of mud samples obtained from location RT, under the same conditions as mentioned before. After designated time intervals (i.e., 3, 7, 10 days, etc.), sample aliquots were sacrificed for the analysis of physical and rheological properties.

2.4 Rheological characterization

The rheological analysis of both fresh and degraded mud samples was performed using a HAAKE MARS I rheometer (Thermo Scientific, Germany) with Couette geometry (gap width = 1 mm). The mud samples were gently homogenized before each rheological experiment. After inserting the geometry into the sample, a waiting time of 3–5 min was adopted before the start of the experiment, in order to minimize the disturbances created by the bob while attaining the required measurement gap (i.e., between the bottom of the bob and the cup). The rheological experiments were performed at 20 °C, maintained by a Peltier controller system. In order to check the repeatability, all the experiments were performed in duplicate and the repeatability error was less than 2%.

Different types of rheological tests were performed to analyze the effect of organic matter degradation on the rheological properties of mud. Stress ramp-up tests were performed by linearly increasing the stress at a rate of 1 Pa. s−1, until the shear rate reached 300 s−1 (Shakeel et al. 2020b). The corresponding rotation of the geometry was measured, which eventually provided the shear rate and apparent viscosity. The amplitude sweep test was carried out at a frequency of 1 Hz by applying an oscillatory stress, instead of a steady stress. The storage (\({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)) and loss (\({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)) moduli (Shakeel et al. 2020d) were obtained as a function of oscillatory amplitude. The frequency sweep test was performed within the linear viscoelastic (LVE) regime, from 0.1 to 100 Hz. The LVE regime was determined from the amplitude sweep tests (i.e., the regime where moduli were almost constant as a function of amplitude). The outcome of frequency sweep tests was obtained in the form of storage and loss moduli as a function of frequency, which was then converted into complex modulus (\({G}^{*}\)) and phase angle (\(\delta\)).

The time-dependent properties were obtained by performing the shear rate ramp up and ramp down experiment as follows: (i) shear rate ramp-up from 0 to 100 s−1 for 50 s, (ii) constant shear rate of 100 s−1 for 50 s, and (iii) shear rate ramp-down from 100 to 0 s−1 for 50 s. In addition to the time-dependent experiment, a structural recovery test was carried out by using a three step protocol given in Shakeel et al. (2020c). In short, the first step provides the moduli of the mud sample (\({G}_{0}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)) before pre-shearing, by performing a small amplitude oscillatory time sweep experiment. The second step involves the application of a high shear rate (300 s−1 for 500 s) to completely disturb the sample. The last step allows the sample to recover its structure by again performing a small amplitude oscillatory time sweep experiment for 500 s and recording the moduli as a function of time (\({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Stress ramp-up tests

In order to investigate the influence of organic matter degradation on the yield stress of mud, stress ramp-up tests were performed. Figure S3 shows the behavior of apparent viscosity as a function of shear stress for fresh mud samples and mud samples that had been degraded for 250 days. A two-step yielding behavior was clearly identified from the two declines in viscosity. A similar two-step yielding behavior, in stress/shear rate sweep tests, has been previously reported for fine-grained sediments (Nie et al. 2020; Shakeel et al. 2020d).

Shakeel et al. (2021b) attributed the two-step yielding in mud samples to the (i) formation of interconnected network of flocs (first viscosity plateau), (ii) breakage of network of flocs (first viscosity decline), (iii) formation of cylinder/roll-like structures (second viscosity plateau), and (iv) collapse of reorganized flocs (second viscosity decline). The yield stress values, corresponding to the viscosity declines, were defined as the points of intersection of the extrapolated slopes of viscosity over stress before and after the decline (Fig. S3). The first yield point was denominated as static yield stress (\({\tau }_{s}\)) while the second decline was referred to as fluidic yield stress (\({\tau }_{f}\)). The example given in Fig. S3 shows that degraded mud had lower yield stress values than the fresh mud. This may be attributed to the presence of organic matter resulting in a stronger structure (i.e., higher yield stresses) of mud (Shakeel et al. 2019). The degradation/removal of this organic matter leads to a weaker system with lower yield stress values. A decrease in yield stress values by chemically removing the organic matter content was also reported in literature for fine-grained sediments (Fass and Wartel 2006).

In order to further quantify the effect of organic matter degradation on the yield stress of mud samples from different locations, the change in static and fluidic yield stresses (degraded − fresh) was plotted as a function of yield stress of fresh samples in Fig. 1. A decrease in yield stress values is observed as a consequence of the degradation of organic matter, for all the investigated locations. Moreover, this decrease in yield stresses was found to be strongly correlated to the yield stress values of the original, freshly sampled mud, i.e., the higher the original yield stress, the higher its reduction as a result of organic matter degradation (resulting in a negative slope). This shows that the effect of organic matter degradation on the yield stresses was more pronounced for the mud samples having higher yield stress values before degradation. The higher yield stress values of mud samples are typically associated to either higher density or higher organic matter content (Van Kessel and Blom 1998; Soltanpour and Samsami 2011; Xu and Huhe 2016; Shakeel et al. 2019, 2020d). In order to compare the effect of organic matter degradation on different rheological properties (i.e., yield stress, moduli, structural recovery, etc.), the following empirical equation was used to fit the experimental data of change in rheological property (degraded − fresh) as a function of the same rheological property before degradation, for all the locations:

a Change in static yield stress (degraded – fresh) as a function of static yield stress of fresh mud sample from different locations, and b change in fluidic yield stress (degraded – fresh) as a function of fluidic yield stress of fresh mud sample from different locations. The dashed line represents the value where the degraded and fresh mud samples have same yield stresses. The solid line represents the empirical fitting using Eq. (1)

where \(a\) and \(b\) represent the intercept and slope of the line, respectively. For instance, the values of \(a\) and \(b\) were observed to be 0.99 and −0.37 for static yield stress and 1.73 and −0.28 for fluidic yield stress. The values of the slope clearly indicate that the yield stresses (static and fluidic) were reduced by almost 1/3 of its original value due to the degradation of organic matter. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the main objective of using this simple linear relation (Eq. (1)) is just to obtain a trend (particularly the slope of the line) for the change in rheological properties after degradation as a function of rheological properties of fresh sample, instead of giving a predictive correlation. However, the values of intercept (parameter \(a\)) are also provided for each rheological property, which can be useful for future studies.

3.2 Amplitude sweep tests

In addition to the yield stress of mud samples, the solid–liquid transition (a crossover between \({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\) and \({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)) was studied by performing oscillatory amplitude sweep tests. A preliminary analysis was performed to select a suitable frequency for amplitude sweep tests (data not shown), which was found to be 1 Hz for all the selected mud samples. Figure 2a presents the storage and loss moduli as a function of oscillatory amplitude for fresh mud sample and mud sample degraded for 250 days. A linear viscoelastic (LVE) regime was identified from an almost independent behavior of moduli at smaller amplitudes, which also provided essential information to perform frequency sweep tests within LVE regime. Apart from LVE regime, the solid–liquid transition was estimated from the crossover between \({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\) and \({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\) and the corresponding amplitude was stated as crossover amplitude.

a Storage (filled symbols) and loss (empty symbols) moduli as a function of oscillatory amplitude for fresh mud sample and mud sample degraded for 250 days, collected from KH location. The circles represent the crossover amplitude. b change in crossover amplitude (degraded – fresh) as a function of crossover amplitude of fresh mud sample from different locations. The dashed line represents the value where the degraded and fresh mud samples have same crossover amplitude. The solid line represents the empirical fitting using Eq. (1)

Figure 2a clearly depicts a decrease in crossover stress by the degradation of organic matter, which is in accordance with the yield stress analysis. Change in crossover amplitude (degraded − fresh) is plotted as a function of crossover amplitude of fresh mud sample for different locations (see Fig. 2b). The results again show the significant effect of organic matter degradation on the crossover amplitude for the mud samples having higher crossover amplitude before degradation. This experimental data was also fitted with Eq. 1 and the values of \(a\) and \(b\) were found to be 0.49 and −0.35, respectively.

3.3 Frequency sweep tests

In order to analyze the strength of mud samples before and after degradation of organic matter, frequency sweep tests were performed within LVE regime (i.e., without affecting their structure) from 0.1 to 100 Hz. The outcome of frequency sweep tests is shown in terms of complex modulus and phase angle as a function of frequency for fresh mud sample and mud sample degraded for 250 days, see Fig. S4a and S4b. Both fresh and degraded mud samples showed solid-like character, i.e., an almost independence of complex modulus on frequency and significantly smaller values of phase angle (Lupi et al. 2016). In literature, a similar solid-like behavior of mud samples has been reported in frequency sweep tests (Van Kessel and Blom 1998; Soltanpour and Samsami 2011; Xu and Huhe 2016; Shakeel et al. 2020a). However, a weaker system (with lower complex modulus and higher phase angle values) was observed after the degradation of organic matter as compared to the fresh mud sample. The experimental data at higher frequencies was removed (for some samples) due to the inertial effects caused by the rheometer head.

The values of complex modulus and phase angle at 1 Hz were selected to investigate the effect of organic matter degradation on the strength of mud samples from different locations. Figure 3a shows the correlation between the change in complex modulus (degraded − fresh) and the values of complex modulus of fresh mud samples from different locations. A decrease in complex modulus was observed due to the degradation of organic matter, which became more pronounced for the fresh samples having higher complex modulus, which may again be linked to the higher density of the samples. The empirical fitting of the experimental data of complex modulus using Eq. (1) resulted in the values of 92.9 and −0.49 for \(a\) and \(b\), respectively. The correlation between the change in phase angle (degraded − fresh) and the values of phase angle of fresh mud samples, for different locations, was not very prominent (Fig. 3b). However, the degraded samples exhibited slightly higher values of the phase angle as compared to the fresh mud samples (i.e., positive values of change in phase angle), which indicated a weaker system, as already observed from other results.

a Change in complex modulus (degraded – fresh) at 1 Hz as a function of complex modulus at 1 Hz of fresh mud sample from different locations. The solid line represents the empirical fitting using Eq. (1), b change in phase angle (degraded – fresh) at 1 Hz as a function of phase angle at 1 Hz of fresh mud sample from different locations. The dashed line represents the value where the degraded and fresh mud samples have same complex modulus or phase angle at 1 Hz

3.4 Time-dependent and structural recovery tests

The time-dependent behavior of fresh and degraded mud samples was analyzed by performing shear rate controlled ramp-up and ramp-down experiments from 0 to 100 s−1. The time-dependent character is either observed in the form of clockwise hysteresis loop or counterclockwise hysteresis loop. The former is typically attributed to the faster structural breakdown in ramp-up step as compared to the structural buildup in ramp-down step while the latter is usually linked to the faster structural reformation in the ramp-down step as compared to the other phenomenon (Barnes 1997; Mewis and Wagner 2009). The outcome of shear rate ramp-up and ramp-down experiments show the existence of a typical clockwise loop at higher shear rates for both fresh mud sample and mud sample degraded for 250 days (Fig. 4a). However, at lower shear rates, a counterclockwise loop is observed, which may be attributed to a shear thickening phenomenon or the structural reorganization due to the shearing action (Shakeel et al. 2020b, d). A similar combination of clockwise and counterclockwise loops as a function of shear rate has been reported in literature for fine-grained sediments (Yang et al. 2014).

a Shear stress as a function of shear rate obtained by performing shear rate controlled ramp-up and ramp-down experiments for fresh mud sample and mud sample degraded for 250 days, collected from KH location. The direction of arrows represents the ramp-up or ramp-down curve. The filled region represents the hysteresis area, b change in hysteresis area (degraded – fresh) as a function of hysteresis area of fresh mud sample from different locations. The dashed line represents the value where the degraded and fresh mud samples have same hysteresis area. The solid line represents the empirical fitting using Eq. (1)

Furthermore, the values of shear stress as a function of shear rate was significantly lower for the degraded mud sample as compared to the fresh mud sample, which is again in line with the previous results. The hysteresis area between the clockwise loop (i.e., typical thixotropic character) of the ramp-up and ramp down curves was estimated in order to investigate the effect of organic matter degradation on the time-dependent properties of mud samples. The change in hysteresis area (degraded − fresh) as a function of the values of hysteresis area of fresh mud samples, for different locations, is presented in Fig. 4b. A similar influence of organic matter degradation was observed on hysteresis area, as already observed for other rheological properties including yield stresses, moduli, etc. The empirical fitting of Eq. (1) for time-dependency data resulted in the values of 39.84 and −0.29 for \(a\) and \(b\), respectively. It is interesting to note that the value of parameter \(b\) (i.e., slope) is quite similar, within the range of -0.28 to −0.49, for different rheological properties. This behavior suggests that the overall influence of organic matter degradation is quite similar on different rheological properties, i.e., the extent of decrease in rheological properties as a function of organic matter degradation is similar. This similar effect on different rheological properties is linked to the fact that these properties represent either the structure of mud samples at “rest” or the destruction of structure from an undisturbed state.

In addition to the time-dependent properties of fresh and degraded mud samples, the structural recovery after intensive pre-shearing was investigated using a three-step protocol explained in Sec. 2. The normalized time dependent storage modulus (\({G}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}/{G}_{0}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)) as a function of time for fresh mud sample and mud sample degraded for 250 days is presented in Fig. S5. The oscillations in the storage modulus behavior, as a function of time, may be associated to the higher elasticity of the samples (Goudoulas and Germann 2016; Shakeel et al. 2020c). The results show higher normalized modulus values, at any particular time, for the degraded mud samples as compared to the fresh mud samples.

In order to further quantify the structural recovery behavior of fresh and degraded mud samples, a simple stretched exponential function, adapted from Mobuchon et al. (2009), was used to fit the experimental data of third step of structural recovery protocol, written as follows:

where \({G}_{\infty }^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\) and \({t}_{r}\) represent the two most important parameters related to the structural recovery behavior of mud samples (Shakeel et al. 2020c). The change in normalized equilibrium storage modulus, \({G}_{\infty }^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}/{G}_{0}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\) (degraded − fresh) as a function of the values of normalized equilibrium storage modulus of fresh mud samples is plotted in Fig. 5a for different locations. It can be seen that the values of normalized equilibrium storage modulus (\({G}_{\infty }^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}/{G}_{0}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)) are higher for the degraded mud samples (i.e., positive values of change in normalized equilibrium storage modulus) than for the fresh mud samples. This may be attributed to the fact that the degradation of organic matter result in a weaker system, behaving as a purely mineral suspension without the bridging effect provided by organic matter, which eventually has a better structural recovery (i.e., higher values of modulus, higher strength) after pre-shearing. A similar enhanced structural recovery was observed in literature for mud samples having lower organic matter content as compared to the samples having higher organic matter content (Shakeel et al. 2020c).

a Change in normalized equilibrium storage modulus, \({G}_{\infty }^{^{\prime}}/{G}_{0}^{^{\prime}}\) (degraded – fresh) as a function of normalized equilibrium storage modulus, \({G}_{\infty }^{^{\prime}}/{G}_{0}^{^{\prime}}\) of fresh mud sample from different locations, and b change in characteristic time, \({t}_{r}\) (degraded – fresh) as a function of characteristic time, \({t}_{r}\) of fresh mud sample from different locations. The dashed line represents the value where the degraded and fresh mud samples have same normalized equilibrium storage modulus or characteristic time. The solid line represents the empirical fitting using Eq. (1)

Furthermore, Fig. 5b shows a strong correlation between the change in characteristic time, \({t}_{r}\) (degraded − fresh) and the values of characteristic time of fresh mud samples, for different locations, as already observed for other rheological properties. In this case, the values of the fitting parameters, \(a\) and \(b\), were observed to be 206.7 and −1.06, respectively. It is clear that the slope (\(b\)) of the fitting line (Eq. (1)) of the change of characteristic time over characteristic time found for the fresh sample is significantly different from the values of slope for the change of other investigated rheological properties. This could be attributed to the fact that other rheological properties (i.e., yield stresses, moduli, etc.) represented the strength of mud samples before any disturbance while the characteristic time showed the recovery behavior of structure/strength in mud after complete structural breakdown.

Moreover, it is interesting to note that below a certain characteristic time for the fresh mud sample (i.e., ~ 200 s), the value for characteristic time of degraded mud samples was higher than for the fresh samples while above this critical value of time, the characteristic time of degraded mud samples showed a decrease as compared to the fresh mud samples. This behavior may again be linked to the variable density of the mud samples, in addition to the organic matter degradation.

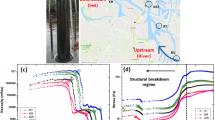

3.5 Effect of degradation time

The rheological analysis of degraded mud, discussed so far, was performed for the samples degraded for 250 days. The change in different rheological properties is plotted as a function of degradation time, see Fig. 6. For instance, the change in yield stresses (static and fluidic), crossover amplitude and complex modulus (degraded − fresh) as a function of degradation time showed two critical values of degradation time after which the change in rheological properties was quite significant (Fig. 6a, b). Initially, after 3 days of degradation, a significant decrease in above mentioned rheological properties was observed, which became more or less constant until 150 days, and after that a further decrease in rheological properties was evident. This behavior may be attributed to the presence of differently degradable organic matter pools which have also been identified by analysis of degradation kinetics (Zander et al. unpublished data), which dominated degradation at different incubation time. Further detailed analysis of the influence of short term degradation on the rheological properties of mud samples is reported in Zander et al. (2022).

a Change in static yield stress (SYS), fluidic yield stress (FYS) and crossover amplitude (COA) as a function of degradation time, b change in complex modulus at 1 Hz as a function of degradation time, c change in normalized equilibrium storage modulus, \({G}_{\infty }^{^{\prime}}/{G}_{0}^{^{\prime}}\) as a function of degradation time, and d change in characteristic time, \({t}_{r}\) as a function of degradation time for the mud sample collected from RT location. The dashed line represents the value where the degraded and fresh mud samples have same rheological property. The solid line is a guide for the eye

The extent of structural recovery after pre-shearing, represented by the normalized equilibrium storage modulus (\({G}_{\infty }^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}/{G}_{0}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}\)), was higher for the degraded mud sample as compared to the fresh mud sample, for more or less all the investigated degradation time intervals (Fig. 6c). This behavior again suggested the better structural recovery in degraded mud due to the weaker system that upon degradation of bridging organic matter behaves like a purely mineral system, even after 3 days of degradation. The change in characteristic time (\({t}_{r}\)), however, displayed a significant increase as a function of degradation time (Fig. 6d). This may be attributed to the fact that the characteristic recovery time of fresh mud sample was lower than 200 s, which resulted in longer characteristic time of degraded mud sample, as already explained in Fig. 5b.

In this study, the influence of organic matter degradation on the rheological properties of mud was investigated by keeping the density of the mud constant, before and after degradation (by adding/removing water and by homogenizing to avoid dewatering). However, under in-situ conditions, settling and consolidation typically occur in different mud layers of varying density, in addition to organic matter degradation. Therefore, it would be interesting to analyze the combined effect of organic matter degradation and settling/consolidation phenomenon on the rheological properties of mud.

4 Conclusions

The presence of organic matter in cohesive sediments results in the formation of clay-organic flocs, which eventually leads to complex rheological behavior including shear-thinning, viscoelasticity, thixotropy and two-step yielding to mud. However, this organic matter undergoes microbial degradation under in-situ conditions and produces CO2 and CH4. Apart from producing greenhouse gases, organic matter degradation can significantly affect the rheological properties of mud by diminishing organic bridges between mineral particles and hence changing the clay-organic floc structures. Therefore, in this study, the influence of organic matter degradation on the rheological properties of mud samples, having similar densities, was examined. The mud samples were collected from three different locations of the Port of Hamburg, Germany, in order to have varying organic matter content. The rheological analysis of fresh and degraded mud samples was performed with the help of several tests including stress ramp-up tests, amplitude sweep tests, frequency sweep tests, time-dependent tests and structural recovery tests.

The results show a significant decrease in rheological properties including yield stresses (static and fluidic), crossover amplitude, complex modulus and hysteresis area for degraded mud samples as compared to the fresh mud samples. The slopes (\(b\)) of the lines, correlating the change (degraded − fresh) in above-mentioned rheological properties as a function of the same rheological property of the fresh mud, are quite similar and vary within the range of −0.28 to −0.49. This behavior shows that the influence of organic matter degradation is similar for all the rheological properties representing the strength of mud samples. Moreover, the fact that organic matter degradation results in a decrease in rheological properties of mud is an indirect proof of a concept that the organic matter interacts (either by bridging or charge neutralization) with the clay particles to form clay-organic flocs. The structural recovery tests displayed a higher extent of recovery in mud after pre-shearing for the degraded mud than for the fresh mud, which suggests the existence of a pure clay-dominated, OM-depleted system after organic matter degradation.

The behavior of the characteristic recovery time (\({t}_{r}\)) shows that below a certain value for fresh mud sample (i.e., ~ 200 s), the characteristic time of degraded mud samples is higher than the fresh samples while above this critical value of time, the characteristic time of degraded mud samples show a decrease as compared to the fresh mud samples. The effect of degradation time on the rheological properties of mud samples display two critical time periods (3 days and 150 days) after which a significant change in rheological properties of mud samples is observed, which may be attributed to the presence of two differently degradable pools of organic matter in the considered mud sample. This study provided a useful understanding about the influence of organic matter degradation on the rheological properties of mud, which can be used to optimize the sediment management strategies in ports and waterways.

References

Barnes HA (1997) Thixotropy—a review. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech 70:1–33

Chassagne C, Safar Z (2020) Modelling flocculation: towards an integration in large-scale sediment transport models. Marine Geol 430:106361

Chassagne C (2021) A simple model to study the flocculation of suspensions over time. Chem Engin Res Design 172:302–311

Chassagne C, Safar Z, Deng Z, He Q, Manning AJ (2021) Flocculation in Estuaries: Modeling, Laboratory and In-situ Studies. In Sediment Transport-Recent Advances. Intech Open

Coussot P (1997) Mudflow Rheology and Dynamics. CRC Press, Rotterdam, p 272

Deng Z, He Q, Safar Z, Chassagne C (2019) The role of algae in fine sediment flocculation: in-situ and laboratory measurements. Marine Geol 413:71–84

Deng Z, He Q, Chassagne C, Wang ZB (2021) Seasonal variation of floc population influenced by the presence of algae in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary. Marine Geol 440:106600

Fass RW, Wartel SI (2006) Rheological properties of sediment suspensions from Eckernforde and Kieler Forde Bays, Western Baltic Sea. Int J Sediment Res 21:24–41

Goudoulas TB, Germann N (2016) Viscoelastic properties of polyacrylamide solutions from creep ringing data. J Rheol 60:491–502

ISO (11465:1993) Soil quality — Determination of dry matter and water content on a mass basis — Gravimetric method

ISO (17892–3:2015) Geotechnical investigation and testing — Laboratory testing of soil — Part 3: Determination of particle density

Lagaly G, Dékány I (2013) Chapter 8 - Colloid Clay Science. In: Bergaya F, Lagaly G (Eds), Developments in Clay Science. Elsevier 243–345

Lupi FR, Shakeel A, Greco V, Rossi CO, Baldino N, Gabriele D (2016) A rheological and microstructural characterisation of bigels for cosmetic and pharmaceutical uses. Materials Sci Eng: C 69:358–365

Malarkey J, Baas JH, Hope JA, Aspden RJ, Parsons DR, Peakall J, Paterson DM, Schindler RJ, Ye L, Lichtman ID, Bass SJ, Davies AG, Manning AJ, Thorne PD (2015) The pervasive role of biological cohesion in bedform development. Nat Comm 6:6257

Mewis J, Wagner NJ (2009) Thixotropy. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 147:214–227

Mobuchon C, Carreau PJ, Heuzey M-C (2009) Structural analysis of non-aqueous layered silicate suspensions subjected to shear flow. J Rheol 53:1025–1048

Nie S, Jiang Q, Cui L, Zhang C (2020) Investigation on solid-liquid transition of soft mud under steady and oscillatory shear loads. Sediment Geol 397:105570

Parsons DR, Schindler RJ, Hope JA, Malarkey J, Baas JH, Peakall J, Manning AJ, Ye L, Simmons S, Paterson DM, Aspden RJ, Bass SJ, Davies AG, Lichtman ID, Thorne PD (2016) The role of biophysical cohesion on subaqueous bed form size. Geophys Res Lett 43:1566–1573

Sander R (2015) Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos Chem Phys 15:4399–4981

Schindler RJ, Parsons DR, Ye L, Hope JA, Baas JH, Peakall J, Manning AJ, Aspden RJ, Malarkey J, Simmons S, Paterson DM, Lichtman ID, Davies AG, Thorne PD, Bass SJ (2015) Sticky stuff: redefining bedform prediction in modern and ancient environments. Geol 43:399–402

Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Chassagne C (2019) Is density enough to predict the rheology of natural sediments? Geo-Marine Lett 39:427–434

Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Chassagne C (2020a) Rheological analysis of natural and diluted mud suspensions. J Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 286:104434

Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Chassagne C (2020b) Yield stress measurements of mud sediments using different rheological methods and geometries: an evidence of two-step yielding. Marine Geol 427:10624

Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Chassagne C (2020c) Effect of pre-shearing on the steady and dynamic rheological properties of mud sediments. Mar Pet Geol 116:104338.

Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Chassagne C (2020d) Rheological analysis of mud from Port of Hamburg, Germany. J Soils Sediments 20:2553–2562

Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Talmon A, Chassagne C (2021a) Rheological analysis and rheological modelling of mud sediments: what is the best protocol for maintenance of ports and waterways? Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci 257: 107407

Shakeel A, MacIver MR, van Kan PJM, Kirichek A, Chassagne C (2021b) A rheological and microstructural study of two-step yielding in mud samples from a port area. Colloids Surf, A 624:12682

Soltanpour M, Samsami F (2011) A comparative study on the rheology and wave dissipation of kaolinite and natural Hendijan Coast mud, the Persian Gulf. Ocean Dyn 61:295–309

Spearman J, Manning AJ (2017) On the hindered settling of sand-mud suspensions. Ocean Dyn 67:465–483

Tolhurst TJ, Gust G, Paterson DM (2002) The influence of an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) on cohesive sediment stability. In: Winterwerp JC , Kranenburg C (Editors), Proceedings in Marine Science. Elsevier, pp. 409–425

Van Kessel T, Blom C (1998) Rheology of cohesive sediments: comparison between a natural and an artificial mud. J Hydraulic Res 36:591–612

Wurpts R, Torn P (2005) 15 years experience with fluid mud: definition of the nautical bottom with rheological parameters. Terra Et Aqua 99:22–32

Xu J, Huhe A (2016) Rheological study of mudflows at Lianyungang in China. Int J Sediment Res 31:71–78

Yang W, Yu G-l, Sk T, Wang H-k (2014) Rheological properties of dense natural cohesive sediments subject to shear loadings. Int J Sediment Res 29:454–470

Zander F, Heimovaara T, Gebert J (2020) Spatial variability of organic matter degradability in tidal Elbe sediments. J Soils Sediments 20:2573–2587

Zander F, Shakeel A, Kirichek A, Chassagne C, Gebert J (2022) Effect of organic matter degradation in cohesive sediment: a spatiotemporal analysis of yield stresses. J Soils Sediments (in press)

Acknowledgements

This study is carried out within the framework of the MUDNET academic network. https://www.tudelft.nl/mudnet/. The authors would like to acknowledge Deltares, The Netherlands, for the use of the HAAKE MARS I rheometer, which was made possible thanks to the Memorandum of Understanding signed between Deltares and the TU Delft.

Funding

This study is funded by the Hamburg Port Authority.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Jasmina Obhodas

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shakeel, A., Zander, F., de Klerk, JW. et al. Effect of organic matter degradation in cohesive sediment: a detailed rheological analysis. J Soils Sediments 22, 2883–2892 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-022-03156-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-022-03156-5