Abstract

This research explores the relationships between the dark triad, motivational dynamics, and entrepreneurial intentions, as well as the moderating effect of the country on these relationships. Using a cross-sectional design, the study utilizes a sample of 701 new entrepreneurs from Turkey (n = 368) and Kosovo (n = 333). The findings indicate that narcissism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions. Additionally, psychopathy and Machiavellianism negatively impact motivational dynamics, while narcissism has a positive effect. Furthermore, the positive effects of motivational dynamics on entrepreneurial intentions have been confirmed. Mediation analysis reveals that individual motivations partially mediate the relationship between the dark triad and entrepreneurial intentions. Finally, the research results show that the country plays a moderating role in the relationships between narcissism and entrepreneurial intentions, personal attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions, psychopathy, and perceived behavioral control, and the need for achievement and narcissism with personal attitudes. Our study provides theoretical contributions as well as policy and managerial implications in the emerging field of entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

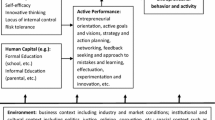

Entrepreneurship is the main engine of a country's socio-economic development and ability to compete (Aparicio et al., 2016). Entrepreneurial behavior is the primary mechanism that enhances countries' economic development and competitiveness (Kara et al., 2024). Consequently, the growing attention of scholars to the factors driving entrepreneurship has led to the emergence of entrepreneurial intentions literature within entrepreneurship (Liñán & Fayolle, 2015). Intentions are considered the antecedents of individual behavior, acting as the driving forces that lead to entrepreneurial behavior (Cai et al., 2021; González-Serrano et al., 2018). Entrepreneurial intentions (EI) are the focused cognitive structures that direct an individual's attention and experience toward planned entrepreneurial behavior (Do & Dadvari, 2017; Obschonka et al., 2017). These phenomena have led scholars to examine the relationship between motivational dynamics and EI (Bağış et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2018).

Previous research on the entrepreneurial intentions of nascent entrepreneurs has generally focused on motivational dynamics and has rarely examined the dark side of personality (the dark triad, sadism, neuroticism, and negative emotions) and their positive effects (Klotz & Neubaum, 2016; Kraus et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016). These studies have produced mixed results and have not examined dark personality traits and motivational dynamics together (Brownell et al., 2021; Hoang et al., 2022; Kraus et al., 2018; Miller, 2015). Moreover, the impact of the dark triad and motivational dynamics on the entrepreneurial intentions of nascent entrepreneurs has not been adequately studied in different cultural and economic contexts (Grijalva & Newman, 2015; Harms et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). For this reason, scholars have emphasized the importance of investigating the effects of the dark triad and motivational dynamics on the entrepreneurial intentions of nascent entrepreneurs and have increased calls for research on this subject (Asenkerschbaumer et al., 2024; Cai et al., 2021; Kraus et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2018). Based on the deficiencies of past research, firstly, we argue that dark triad personality traits may positively affect entrepreneurial intentions. Secondly, we acknowledge that the dark triad and motivational dynamics impact entrepreneurial intentions differently in countries with different cultural characteristics.

In this context, we examine the relationship between the dark triad, motivational dynamics, and entrepreneurial intentions by presenting evidence from two countries (Türkiye and Kosovo). Our study used Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and Narcissism as dark triad personality traits (Kraus et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019). We also considered personal attitudes (PA), perceived behavioral control (PBC) (Ajzen, 1991), and need for achievement (NFA) (McClelland, 1961) variables as motivational dynamics or individual motives. Our study presents findings from countries at different institutional and economic development levels based on the dark triad, the theory of planned behavior, and the need for achievement approaches.

This research explores the relationships between the dark triad, motivational dynamics, and entrepreneurial intentions, as well as the moderating effect of the country on these relationships. Within this framework, the contribution of the study is threefold: Firstly, we contribute to the nascent entrepreneurs' literature by empirically testing the relationships between the dark triad and individual motives, relying on the dark triad literature, the theory of planned behavior, and need for achievement theories (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Kraus et al., 2018, 2020; Wu et al., 2019). In this way, we aim to show the influence of the dark triad and motivational dynamics on entrepreneurial intentions, as revealed jointly. Secondly, past research has employed self-efficacy (Wu et al., 2019) and opportunity recognition (Caniëls & Motylska-Kuźma, 2023; Hoang et al., 2022) as mediators between the dark triad and entrepreneurial intentions. Our study uses PA, PBC, and NFA as mediating variables, thus contributing to the literature. Thirdly, we provide evidence that the country can moderate the relationship between the dark triad and entrepreneurial intentions in Türkiye and Kosovo, which have different cultural characteristics and are at varying levels of institutional and economic development. In this way, our study responds to calls to examine individuals from different cultural backgrounds in the dark triad and entrepreneurship relationship (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Wu et al., 2019).

The structure of this paper is as follows: the next section presents the theoretical background and builds the hypotheses of this study. The third section covers the methodology, followed by the findings in the fourth section. The final section includes the discussion, policy implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical background

Dark triad

The dark triad personality traits consist of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism dimensions. Narcissistic personality traits are characterized by egocentrism, arrogance, and a sense of superiority (Brownell et al., 2024). Psychopathy is a personality trait characterized by low empathy, impulsivity, persistent antisocial behavior, and a lack of guilt (Schimmenti et al., 2019). Machiavellianism refers to individuals who use and manipulate others for their purposes (Laouiti et al., 2024). These personality traits are generally viewed negatively concerning motivational dynamics and entrepreneurial intentions (Brownell et al., 2021; Do & Dadvari, 2017). However, some studies have revealed that dark triad personality traits affect these variables positively (Baldegger et al., 2017; Burger et al., 2024). Based on these discussions, we argue that dark triad personality traits will affect motivational dynamics and entrepreneurial intentions.

Theory of planned behavior

The theory of planned behavior posits that an individual's intention to perform a specific behavior is driven by individual motivations (Ajzen, 1991, 2001). The theory comprises three dimensions: personal attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Kautonen et al., 2013). Personal attitudes refer to an individual's disposition towards a behavior. Subjective norms are defined as the perceived social pressure an individual feels. Perceived behavioral control pertains to an individual's perceptions of their confidence and self-control (Al Halbusi et al., 2023; Bueckmann-Diegoli et al., 2021; González-Serrano et al., 2018; Karan et al., 2024). Research has shown that subjective norms positively influence entrepreneurial intentions (Ephrem et al., 2019; Farrukh et al., 2019), while others argue that this relationship is weak or non-existent (Al-Mamary et al., 2020; Lopes et al., 2020). Considering these conflicting findings, our research did not examine subjective norms. Consequently, in this study, we conceptualize the personal attitudes and perceived behavioral control dimensions of the theory of planned behavior as individual motivations or motivational dynamics. We argue that motivational dynamics are influenced by dark triad personality traits, affect entrepreneurial intentions, and mediate the relationship between dark triad personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions.

Need for achievement theory

The need for achievement theory refers to an individual's motivation and psychological strength to reach specific goals during an action or behavior (McClelland, 1961; Wu et al., 2007). This need helps individuals become more psychologically motivated to perform an action or behavior, and those with a high need for achievement have a strong determination to accomplish complex tasks (Bağış et al., 2023). Key characteristics include motivation, desire to achieve goals, and willingness to feel responsible for success (Wiramihardja et al., 2022). This research conceptualizes the need for achievement as individual motivations or motivational dynamics. We posit that the need for achievement is influenced by dark triad personality traits, affects entrepreneurial intentions, and mediates the relationship between dark triad personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis development

Psychopathy-machiavellianism and entrepreneurial intentions

Scholars are debating whether the psychopathy and Machiavellianism dimensions should be measured separately or as a single variable regarding the dark triad. Many studies have failed to report the interrelationships among the three constructs of the dark triad (Glenn & Sellbom, 2015; Miller et al., 2017). Therefore, our research develops hypotheses based on two-factor studies (Glenn & Sellbom, 2015; Miller et al., 2017) and examines psychopathy and Machiavellianism as a single-factor structure.

Psychopathic individuals exhibit a lack of empathy, boldness, and selfishness; they are often seen as charming and attractive. Such individuals tend to have high entrepreneurial intentions (Cai et al., 2021; McLarty et al., 2021) because they are driven to improve themselves when they aspire to become entrepreneurs. There are several reasons why individuals with psychopathic personality traits have higher entrepreneurial intentions. Their emotional insensitivity (Carter et al., 2024), motivation to promote themselves, their image, and their wealth (Kramer et al., 2011), their lack of risk aversion, ability to concentrate and perform well in uncertain situations, and their attractiveness as leaders (Wu et al., 2019) contribute to their pursuit of personal gain through entrepreneurship (McLarty et al., 2023). Additionally, according to Tucker and colleagues (2016), psychopaths can discover, evaluate, and exploit opportunities. These individuals are characterized by their motivation and active search abilities when discovering opportunities. They do not share information with others, giving them an advantage in analyzing opportunities and assessing whether they are exploitable or profitable. When evaluating these opportunities, these individuals can focus and allocate their efforts and utilize strategic human resources (McLarty et al., 2023). Furthermore, individuals with this personality trait can use others for their benefit (Tucker et al., 2016). Therefore, their ability to exploit opportunities for personal gain leads to higher entrepreneurial intentions (Laouiti et al., 2024).

The characteristics of Machiavellian individuals include cunning, immorality, opportunism, political maneuvering, deceitfulness, and lack of conscience (McLarty et al., 2021). Despite these traits, Machiavellianism is important for new entrepreneurs (Schippers et al., 2019) and positively influences entrepreneurial intentions (McLarty et al., 2023). An entrepreneurial career can attract them because it provides wealth and power and helps them control others to satisfy their egos (Hmieleski & Lerner, 2016). There are several reasons why Machiavellianism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions. First, these individuals exert more effort to achieve their goals because they can manipulate others and motivate those around them to succeed (Klotz & Neubaum, 2016). Second, starting a business requires recognizing opportunities, forming alliances, and acquiring resources crucial for entrepreneurial success. The ability to evaluate opportunities with strategic and calculated characteristics, strategic thinking, and opportunistic orientations is essential for business success (Tucker et al., 2016). Individuals with high Machiavellian personalities can maximize the resources at their disposal, make decisions about opportunities, and reduce uncertainty. They have high entrepreneurial intentions as they analyze situations according to personal goals, pursue opportunities, and are described as strategic and calculated (Tucker et al., 2016). Therefore, their ability to take shortcuts to achieve their goals, focusing on wealth and power, leads to success, especially in uncertain entrepreneurial environments (Wu et al., 2019). Based on these discussions, we posit that Psychopathy/Machiavellianism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions and propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 1: Psychopathy/Machiavellianism (Psycho/Mach) positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

Narcissism and entrepreneurial intentions

Research suggests that narcissism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions (Baldegger et al., 2017; Burger et al., 2024) and is associated with various traits that explain why these individuals are more inclined to become entrepreneurs. First, starting a new business is a risk-taking process that requires new entrepreneurs to make risky decisions. Therefore, risk propensity is an essential determinant of entrepreneurial intention (Botha & Sibeko, 2024; Li et al., 2023). Narcissistic individuals are likely to engage in entrepreneurial ventures if they believe they will benefit from risk-taking behaviors (Foster et al., 2009). Some studies have found that in uncertain business environments, individuals with narcissistic personality traits perform better and exhibit entrepreneurial intentions due to their risk-taking abilities (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Gao & Huang, 2022).

The image of being an entrepreneur motivates individuals with narcissistic personality traits to seek self-promotion, prestige, wealth, and adventure (Meddeb et al., 2024). Thus, becoming an entrepreneur can be considered a significant career choice for narcissists (Mathieu & St-Jean, 2013). For instance, the study by Hmieleski and Lerner (2016) suggests that narcissism is positively related to productive entrepreneurial motivations due to the desires for attention, admiration, and the creation of social and productive value. Confidence in their ability to succeed is a significant reason why narcissists have entrepreneurial intentions. New entrepreneurs characterized by narcissistic traits often become leaders and achieve considerable success (Lee et al., 2023). Being an entrepreneur also allows them to exploit others, showcase themselves, and attract attention with their achievements. Based on these discussions, we posit that narcissism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions and propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 2: Narcissism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

Dark triad and motivational dynamics

Research on the impact of dark triad personality traits on motivational dynamics has yielded inconsistent findings. Studies report that psychopathy and Machiavellianism have more negative effects on motivational dynamics compared to narcissism. This is because individuals with psychopathic and Machiavellian traits tend to focus on personal gain at the expense of others and business ethics (Sayal & Singh, 2020). This likely negatively reflects on their motivational dynamics. Consequently, individuals with these personality traits may exhibit antisocial behaviors and struggle to adapt to the entrepreneurial environment over time, adversely affecting their motivation (Brownell et al., 2021). Machiavellianism, characterized by an individual's ability to manipulate others, can lead to negative attitudes toward others, self-centeredness, and disregard for the social interests and expectations of others (McLarty et al., 2021). Additionally, individuals with psycho-Mach personality traits may face difficulties in self-regulation within a dynamic entrepreneurial environment. Based on these discussions, we posit that psychopathic and Machiavellian personality traits negatively influence motivational dynamics and develop the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 3a: Psychopathy/Machiavellianism negatively influences personal attitudes.

-

Hypothesis 3b: Psychopathy/Machiavellianism negatively influences perceived control behavior.

-

Hypothesis 3c: Psychopathy/Machiavellianism negatively influences the need for achievement.

Research on narcissism suggests that this personality trait has a more positive impact on individual motivations compared to psychopathy and Machiavellianism (Hmieleski & Lerner, 2016). This may be related to narcissists' need for admiration, desire to pursue an entrepreneurial career, and propensity to take risks (Foster et al., 2009). Indeed, since narcissists are motivated by a desire for success to promote themselves within their social environment, these personality traits are more likely to influence individual motivations positively (Kramer et al., 2011). Based on these distinct differences, we argue that narcissism positively affects individual motivations compared to psychopathy and Machiavellianism and propose the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 4a: Narcissism positively influences personal attitudes.

-

Hypothesis 4b: Narcissism positively influences perceived control behavior.

-

Hypothesis 4c: Narcissism positively influences the need for achievement.

Motivational dynamics and entrepreneurial intentions

Motivational dynamics are the fundamental mechanisms underlying individuals' behaviors and are likely to influence entrepreneurial intentions. Indeed, research shows that personal attitudes positively affect entrepreneurial intentions (Bueckmann-Diegoli et al., 2021; González-Serrano et al., 2018; Romero-Colmenares & Reyes-Rodríguez, 2022). This relates to new entrepreneurs' attitudes toward becoming entrepreneurs and includes emotional and evaluative thoughts based on the appeal and advantages of an entrepreneurial career (Liñán & Chen, 2009). Therefore, personal attitudes are associated with entrepreneurs' beliefs that affect their intentions to start a new venture (Laukkanen, 2023). Similarly, perceived behavioral control is linked to individuals' ability to perceive the challenges of becoming an entrepreneur, feel competent in becoming a successful entrepreneur, and have a sense of control (Liñán & Chen, 2009). Studies show that perceived behavioral control positively influences entrepreneurial intentions (Romero-Colmenares & Reyes-Rodriguez, 2022). Moreover, the need for achievement is a significant driving factor for individuals concerning complex tasks (Bağış et al., 2023). The need for success and achievement is the primary motivation for starting a business (Ibidunni et al., 2020). Research shows a strong relationship between the need for achievement and entrepreneurial intentions (EI) (Akhtar et al., 2020; Bağış et al., 2023; Karimi et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021). Based on these findings, we posit that motivational dynamics positively influence entrepreneurial intentions and propose the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 5: Personal attitudes positively influence entrepreneurial intentions.

-

Hypothesis 6: Perceived behavior control positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

-

Hypothesis 7: The need for achievement positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

Mediation of motivational dynamics

Understanding the effects of the dark triad on entrepreneurial intentions requires examining the individual motivations underlying the decision to become an entrepreneur (Do & Dadvari, 2017). Indeed, a study conducted in Turkey and Kosovo by Bağış et al. (2023) found that personal attitudes and perceived behavioral control mediate the relationship between the need for achievement and entrepreneurial intentions. Similarly, another study by Bağış et al. (2024) concluded that personal attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and the need for achievement mediate the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurial intentions. These findings suggest that motivational dynamics may mediate the relationship between the dark triad and entrepreneurial intentions. The literature on this topic indicates that entrepreneurial self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between narcissism and entrepreneurial intentions (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Gao & Huang, 2022). However, the conflicting findings of Wang et al. (2016) indicate that individual motivations, such as self-efficacy, may not mediate this relationship, possibly due to the inherently negative aspects of narcissistic traits. Given the international context of our study, which encompasses countries at different stages of institutional and economic development, we propose that personal attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and the need for achievement may mediate the relationship between dark triad traits and entrepreneurial intentions, and we develop the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 8: Personal attitudes, perceived behavior control, and need for achievement mediate the influences of Psych/ Mach on entrepreneurial intentions.

-

Hypothesis 9: Personal attitudes, perceived behavior control, and need for achievement mediate the influences of narcissism on entrepreneurial intentions.

The moderating role of country

Despite the burgeoning body of literature on the dark triad and entrepreneurial intention, there is a gap in the literature regarding the moderating role that countries play in the impact of the dark triad on entrepreneurial intentions. Aiming to contribute solidly to the literature, our study selected two culturally, institutionally, and economically different countries: Türkiye and Kosovo. There are several reasons for choosing these two countries. Firstly, scholars acknowledge the importance of context when analyzing the dark triad, as it may impact personality traits (Klotz & Neubaum, 2016; Miller, 2015, 2016). Scholars have called for more empirical studies to compare countries regarding the dark triad and the EI relationship (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Hoang et al., 2022). Considering the gap in the literature on cross-country comparisons, we examine the country as a moderating variable, a missing point in the entrepreneurship-dark triad research (Brownell et al., 2021).

Secondly, Türkiye and Kosovo differ significantly in terms of culture, making it interesting to investigate whether there are differences in the moderating role that the country may play. Based on Hofstede’s (1980) classification of cultural dimensions, Türkiye and Kosovo differ. Türkiye falls into categories of individualism, femininity, and high uncertainty avoidance, whereas Kosovo is characterized by individualism, masculinity, low uncertainty avoidance, and collectivism (Karagüzel & Bağış, 2021). Previous studies have shown differences in cultural settings, the dark triad personality traits, and entrepreneurial intentions (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021), including the impact of culture on entrepreneurial intentions (Bogatyreva et al., 2019), and the distinct characteristics of intentions across cultures (García-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Kara & Dheer, 2023). Cultural values influence entrepreneurial intentions, including motives, beliefs, and behaviors (Shinnar et al., 2012), thus moderating and leading from intention to actual behavior (Bogatyreva et al., 2019). Cultural settings can explain this. Therefore, by using the country as a moderating variable (González-Serrano et al., 2018, 2021), we argue that we can explain the differences between Türkiye and Kosovo. Additionally, it is essential to emphasize that we do not consider culture as a variable but rather the difference between the two countries in terms of culture.

Thirdly, there are significant differences between Türkiye and Kosovo in terms of institutional and economic development levels. Scholars maintain that dark triad personality traits vary due to differences in cultural, institutional, and socioeconomic well-being (Johnson, 2020; Jonason et al., 2019). Societies that are less developed, less peaceful, more corrupt, and more sex-asymmetrical tend to have more narcissistic individuals. As societies become more advanced, they tend to control Machiavellian individuals and their antisocial behavior, refining their long-term forms of manipulation (Jonason et al., 2020). Another study shows that perceptions of competitiveness are mediated by a country's differences based on the dark triad of personality traits (Jonason et al., 2019). This becomes more evident in countries experiencing institutional voids, where the ability of individuals to fill these voids is crucial for their entrepreneurial ventures (Klotz & Neubaum, 2016; Miller, 2015, 2016).

Türkiye is an upper-middle-income economy with stable institutional settings and consistent economic growth. This is due to the advancement of the policy framework supporting SME innovation through programs for innovation and research (OECD, 2022). Despite economic turmoil and, in some cases, tensions derived from geopolitics, the entrepreneurial ability of the economy has been notable in coping with challenges (OECD, 2021b). Thanks to inter-institutional coordination and advanced environmental policies over the last few years, Türkiye has been a leader in supporting SMEs' green transition (OECD, 2022). However, Türkiye's entrepreneurial culture has not reached the expected levels compared to other developing and developed countries to transition from an efficiency-oriented to an innovation-oriented economy (Ozaralli & Rivenburg, 2016). Türkiye has a more significant number of SMEs per inhabitant than Kosovo, which has a lower average in the Western Balkans and Türkiye (OECD, 2022). Türkiye's Small and Medium Enterprises Development Organisation (KOSGEB) has efficiently monitored SME programs. The entrepreneurial ecosystem has been strengthened thanks to various training programs on green and digitalization for different types of entrepreneurs, including social entrepreneurs. Furthermore, the policy framework regarding SMEs is well-developed thanks to the large scale of support programs, the cooperation between KOSGEB and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TUBITAK), and their investments in research and development (OECD, 2022). In addition, financial support for SMEs and start-ups includes loan interest subsidy programs led by KOSGEB (OECD, 2024).

The institutional environment in Kosovo is characterized by uncertainty for entrepreneurs due to the pitfalls of institutional reforms and the inconsistency of implementing mechanisms (Coşkun et al., 2022; Kryeziu & Coşkun, 2018). Kosovo is a lower-middle-income country and is the second smallest in the Western Balkans after Montenegro (OECD et al., 2019b). It is a transition economy that has shifted from a planned economy to a market economy. Unlike other transition economies, Kosovo's institutions were built from scratch, leading to a deficiency in institutional settings (Kryeziu & Coşkun, 2018; Kryeziu et al., 2022). Institutions in transition economies are characterized by unclear rules and the government's inability to establish efficient enforcement mechanisms (Krasniqi & Desai, 2017). In the context of this study, entrepreneurship in these countries faces barriers primarily due to the uncertainty derived from institutional settings. As a result, this reflects negatively on entrepreneurial efforts (Coşkun et al., 2022; Kryeziu et al., 2022). Compared to other Western Balkan countries, Kosovo is ranked lowest in knowledge, experience, entrepreneurial learning, and intentions to start businesses (Lajqi et al., 2019). This is related to weak policy settings or weak or absent mechanisms to support entrepreneurs in tackling barriers, encouraging innovation and technologies, and improving entrepreneurial knowledge and skills through training to increase the number of entrepreneurs (OECD/ETF/EU/EBRD, 2019a; OECD, 2021a; Government of Kosovo, 2022). Based on the distinct characteristics of Türkiye and Kosovo and the literature review, we propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 10: The country has a moderating effect on the dark triad–entrepreneurial intentions relationship.

Methodology

Survey design and pilot study

Our study measures the direct and mediated relationships between psychopathy-Machiavellianism (psycho-mach), narcissism, and PA, PBC, NFA, and EI. We employed three scales with proven validity, reliability, and high factor loadings to measure these variables and carried out the analysis based on the following steps. First, we employed Jonason and Webster's (2010) dark triad scale, used in previous studies (Miller et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019) to measure three main personality traits: psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism. Each dimension on the scale consists of four items, making 12 items on the scale.

Entrepreneurial intentions were measured based on Liñan and Chen's (2009) scale. The EI scale consists of four dimensions: PA (five items), SN (three items), PBC (six items), and EI (six items), for a total of 20 items. In this study, we used this scale's PA, PBC, and EI dimensions. Finally, Mhango's (2006) scale, designed to test the entrepreneurial career intentions of higher education nascent entrepreneurs, was suitable for measuring the NFA and consists of six items. For the measurement of each item in the questionnaire, a seven-point Likert-type scale was used, ranging from 1 to 7, with "1" meaning "strongly disagree" and "7" meaning "strongly agree."

After analyzing the scales, we translated them into Turkish (in the context of Türkiye) and Albanian (in the context of Kosovo). We then conducted a pilot study with 40 randomly selected participants. The purpose of the pilot phase was to assess the understandability of the questions and the difficulty of completing the questionnaire. During the pilot phase, the participants had no difficulty answering the items in the pretest questionnaire. After the pilot phase, we began gathering data.

Sample

The data source of this study were nascent entrepreneurs from Türkiye and Kosovo. Our study selected Türkiye and Kosovo, which are culturally and institutionally different, to provide more meaningful comparisons on the impact of the dark triad on entrepreneurial intentions. Both countries are geographically different; hence, the personality traits in both countries may be different (Rentfrow et al., 2015). Likewise, the differences in culture, institutions, and the level of economic development of both countries—Kosovo is in a transitional economy, whereas Türkiye is in a developing economy—suggest that the two countries have very different characteristics.

Many studies emphasize the challenge of identifying nascent entrepreneurs (Altinay et al., 2021; Stroe et al., 2018) due to the lack of registered information about nascent entrepreneurs (Honig & Samuelsson, 2012). Entrepreneurship projects, business plan preparation (Dana et al., 2023; Ross & Byrd, 2011), entrepreneurship training, and crowdfunding (Zhao et al., 2023) meetings on entrepreneurship are important platforms to support these entrepreneurs. These organizations provide access to valuable data sources for young and nascent entrepreneurs willing to dedicate resources to entrepreneurial activity (Ross & Byrd, 2011). In this study, nascent entrepreneurs are divided into two groups. The first group consists of individuals who previously or currently own a business, including those already engaged in entrepreneurial activity. The second group includes individuals at the idea stage of starting a venture, those beginning to dedicate effort and resources to start a business, those who attend entrepreneurial crowdfunding meetings, prepare entrepreneurial projects or business plans, and online freelancers. The first group accounts for 43.79% of our sample, while the second group accounts for 56.21%. The sample in our research is considered purposeful and appropriate as it includes individuals who continue their entrepreneurial activities and are determined to continue.

Data collection

Two different research groups in Türkiye and Kosovo carried out data collection. Before the data collection, researchers were trained to inform the participants that their participation was voluntary and anonymous by applicable laws to protect the data. After the data were collected, the first step was to exclude questionnaires that had the same response for all items or were incomplete. Consequently, 32 questionnaires from Türkiye and 20 from Kosovo were excluded from the analyses. The final sample comprises 368 valid questionnaires from Türkiye and 333 from Kosovo. To analyze the data, we conducted frequency and difference analyses (t-test and ANOVA), explanatory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and moderator and mediating analyses for 701 questionnaires from both countries. We used SPSS 25, AMOS, SmartPLS 3, and the Hayes Process SPSS plugin software for the analysis.

Reliability and validity

The reliability analysis shows that the Cronbach's alpha coefficients of the items (eight items above 0.60) are greater than 0.70 (see Table 2). Cronbach's alpha coefficients indicate that the scale has good psychometric properties and meets the requirements of reliable internal consistency (Wu et al., 2019). A factor loading greater than 0.70 in factor analysis indicates that about half of the variance of items can be attributed to the constructs. These results signify construct validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In this study, the factor loadings of the items were above 0.70, except for eight items (see Table 2), which confirms the close relationship between the items and constructs, and validates that the survey meets the requirements of construct validity. Consequently, the overall reliability and validity of the survey meet the criteria necessary for advanced data analysis. As a result, the reliability and validity of the overall questionnaire meet the criteria for further data analysis.

Findings

Table 1 contains the demographic statistics and shows that 65.9 percent of the participants are women. The average age of the participants is 21.09 years, and 74.8 percent live in urban areas. Respondents' families consist of a maximum of five members (25.9 percent), and in terms of income, they are in the middle-income category. 57.9 percent of participants knew an entrepreneur, and 43.79 percent of the sample owned or currently owned a business.

Differences analysis

We employed a t-test to examine the differences in participants' EI perceptions between the two countries. Findings show that participants' perceptions of EI differ significantly between the two countries (t = -3.244, p < 0.001). These findings indicate statistically significant differences between Türkiye and Kosovo since the significance value is less than 0.05 and the t-value is greater than 1.96. The average EI perception in Türkiye differs statistically from the average in Kosovo. Perceptions of entrepreneurial intention do not vary according to age (F = 1.449, p > 0.077); although this value is evaluated cautiously, it indicates a difference at the 10% significance level. Further, we conducted a t-test to analyze the change in perceptions regarding EI based on gender. Findings show that there is no significant difference according to gender (F = 3.02, p > 0.01) and level of education (p > 0.05), and knowing an entrepreneur does not affect the EI to become an entrepreneur (p = 0.716). However, we found significant differences in EI perceptions based on whether participants reside in rural or urban areas (p < 0.007) and the number of individuals living with family (p = 0.729).

Explanatory factor analysis

Table 2 shows the findings from the explanatory factor analysis (EFA). The KMO coefficient of 0.945 indicates the adequacy of the sample size in this study, and the Bartlett Test of Sphericity analysis has a p-value of 0.000, which is less than 0.01. These results show that the data assume multiple normal distributions (Hair et al., 2006) and that factor analysis is viable.

We used principal component analysis and varimax rotation methods to analyze the scale's factor structure. The analysis results confirm the two-factor result (psychopathy and Machiavellianism combined with narcissism) (Miller et al., 2017). The findings shown in Table 2 indicate that the items are grouped under six factors after rotation, with factor loadings varying between 0.582 and 0.919. Values above 0.45 in the factor load coefficient explain the relationship between the items and the factor to which they belong and are accepted as good criteria for item selection (Hair et al., 2006).

Considering the distribution of eigenvalues and explained variances in the factor analysis, it is shown that psycho-Mach (14.21) has the highest eigenvalue. The eigenvalues of the other factors, from highest to lowest, are PBC (7.414), PA (2.378), EI (1.841), Narcissism, and NFA (1.257). Psycho-Mach explains 23.32 percent of the variance, which is the highest value compared to other factors. Other variables in the explained variance rates, from highest to lowest, are PBC (13.61 percent), PA (13.45 percent), EI (12.08 percent), NFA (9.987 percent), and Narcissism (8.391 percent). Table 2 shows that the total explained variance regarding EI is 80.83 percent.

To perform the Structural Equation Model, the data should show a normal distribution in analyses based on variance and covariance. The critical value of multivariate kurtosis, which must be less than 10, indicates whether the data are typically distributed (Ryu, 2011). The analysis undertaken in AMOS obtained a value above the critical threshold. Consequently, confirmatory factor analysis was employed using SmartPLS software due to the multigroup analysis (comparing data from Türkiye and Kosovo) and the essential value of multivariate kurtosis.

Assessment of the measurement model

The reliability and validity of the constructs are essential in the measurement model. We calculated Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values to test the reliability of internal consistency. The minimum cut-off point for all factors is 0.6 (Hair et al., 2017), indicating that the constructs have robust internal consistency reliability for each sub-dimension. Table 3 shows that all structures for each dimension have factor loadings higher than the average variance extracted (AVE) and the minimum shear value. The Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) was also calculated to assess discriminant validity. The calculated confidence interval of HTMT statistics was lower than the threshold value of 0.9 for all factorial sub-dimensions (Nunkoo et al., 2020). The results indicate sufficient convergent and discriminant validity for each considered sub-dimension.

Table 3 shows the CR and AVE values. All external loading values were above the 0.7 thresholds, while the AVE and CR scores were above the 0.50 and 0.70 cut-off points, respectively. These ratios indicate that the measurement model is internally consistent (Hair et al., 2019). The AVE and CR values confirm the convergent validity of the measurement model. Since the measurement results for all dimensions in Table 3 are above the threshold values, the scale formed by these variables is considered structurally reliable and valid. The rho_A in Table 3 is a coefficient calculated to determine whether data consistency is above 70 percent, indicating that the factor items are reliable (Santoso et al., 2020). The AVE's square root must be greater than the correlation between constructs to assess discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 3 shows diagonally correlations between the AVE's structures and their square roots.

Table 4 shows a negative and weak relationship between Psycho-Mach and EI and a positive and weak relationship between Narcissism and EI. The results also show a moderately positive correlation between the PA, PBC, and NFA dimensions and EI. All correlation values are significant at p < 0.05 (at a 1% significance level).

Discriminant validity was assessed using the HTMT ratio, which states the ratio of the study's HTMT correlations of all variables to the geometric means of the monotrait-heteromethod correlations of items of the same variable (Henseler et al., 2015). Scholars maintain that the HTMT value should be below 0.90 and not above 0.85 (Kline, 2011) for concepts far from each other regarding content. HTMT values are given in Table 5. The results show that the specified criteria are met. Thus, there is discriminant validity between constructs.

Common method bias (CMB)

Data are generated using survey expressions, and there is a possibility of widespread method bias in surveys. Harman's single-factor test was used to detect the presence of CMB in this study (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Analysis results with SPSS version 25 show that the first factor explains 23.32 percent of the total variance. This ratio is below 40 percent, indicating that no single factor could explain most of the variance. Therefore, CMB did not significantly affect this study (Lindell & Whitney, 2001).

Structural model

We analyzed the structural model using SmartPLS 3 (Hair et al., 2017). The R2 values are as follows: PA (0.236), PBC (0.110), NFA (0.497), and EI (0.642). The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) is an essential indicator for measuring the fit criteria of the SmartPLS model. The SRMR of the proposed model is 0.09 (< 0.1), indicating that the model has an acceptable fit (Hair et al., 2017). The bootstrap repetition size was 5000 (Streukens & Leroi-Werelds, 2016), and we checked the VIF values to detect possible multicollinearity problems in the model. Hair et al. (2019) stated that the structural model's VIF values of exogenous variables should be less than 5. Since the VIF values in the constructed structural model were less than 5, it was evident that there was no multicollinearity issue in the model.

Coefficient values were measured using the t-value (Hair et al., 2017). Commonly used critical values for bidirectional tests are 1.96 (p = 5 percent) and 2.57 (p = 1 percent). The model is also within the recommended limit for t-values. PLS does not produce goodness-of-fit indices as in covariance-based structural equations. Henseler et al. (2016) suggest using the SRMR value as the appropriate model fit criterion for PLS models. In the multi-group analysis, the SRMR for Türkiye is 0.072, while the SRMR for Kosovo is 0.067. The most common method used to explain structural models is the coefficient of determination (R2). R2 is the correlation between actual and predicted square values (Sarstedt et al., 2011). The R2 coefficients were also checked for effect sizes in the study. In this context, the results of the hypothesis tests are given in Table 6 and Fig. 1 (Results for the Combined Sample). The results show that Psycho/Mach does not significantly affect EI. Therefore, except for the H1 hypothesis, all hypotheses are supported (p < 0.05).

The structural models in Figs. 1 and 2 show the significance of factor loadings based on t-values. At the 95% significance level, t-values higher than 1.96 in absolute value are significant. The value shown outside the parentheses is the beta coefficient in the arrows drawn for the relationships between the dimensions. The value shown in parentheses is the p-value. The significance level for the p-value is less than 0.05.

Mediating analysis

To understand the indirect effects in this study, it is necessary to understand the direct impact first. The p-value of the direct effect of Psycho/Mach on EI is greater than 0.05. Confidence interval levels of total impact and indirect effect values are significant. PBC (β = 0.251, [0.1768, 0.3333]) and NFA (β = -0.3725, [-0.4647, -0.2845]) play a full mediation role according to the results. The mediating role of PBC in the effect of Psycho/Mach on EI is significant at the confidence interval levels. Findings show that NFA has a mediating role in the impact of Psycho/Mach on EI. However, our findings indicate that PA (β = -0.0412, [-0.106, 0.0162]) does not mediate the relationship between Psycho/Mach and EI. H8 was partially supported (see Table 7).

Table 7 shows the regression results and indicates that narcissism significantly affects EI (β = 0.075, SE = 0.028, 95% CI [0.021, 0.13]). Findings also show that PBC has a mediating role in the effect of narcissism on EI (β = 0.1244, 95% CI [0.0462, 0.2046]). However, PA (β = -0.0152, 95% CI [-0.0729, 0.0436]) and NFA (β = -0.0326, 95% CI [-0.1192, 0.0559]) do not have mediating roles in the effect of narcissism on EI. Since the confidence intervals contain both positive and negative values, it has been determined that there is no statistically significant mediating effect. In summary, H9 was partially supported.

Multi-group analysis

Sarstedt et al. (2011) defined multigroup analysis (MGA) as investigating group-specific effects. They examined how the variable determined by this analysis affects the direction and strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The logic of MGA is based on evaluating the differences between the path coefficients of these groups by dividing the categorical variable (such as gender, experience, and age) into two subgroups. Significant differences between the path coefficients of the two groups are interpreted as moderator effects (Barroso et al., 2018).

Assessment of measurement invariance

Before performing the partial least squares multigroup analysis (PLS-MGA) to identify potential similarities and differences between the path coefficients of the subpopulations under consideration, measurement invariance was tested. In SmartPLS, composites are tested using the measurement invariance of composite models (MICOM) procedure, which includes measurement invariance, configuration invariance, composition invariance, and equality of composite mean values and variances. These three steps consist of complete measurement invariance (combining data from different groups), but completing the first two steps is sufficient to run PLS-MGA (Henseler et al., 2016). Evaluation of structural invariance involves evaluating measurement models for all groups to check whether the same number of indicators and the exact variance-based model estimates are used and whether all indicators are treated equally among the specified groups (Henseler et al., 2016). Finally, configuration invariance was established as the analysis and evaluation of the measurement models (reliability and validity) for all groups were completed in the previous subsection.

Composition invariance was examined using a permutation analysis with 5000 resamples via SmartPLS 3 software to ensure homogeneity of composite scores across the considered subpopulations (Henseler et al., 2016). The compositional invariance correlation for MICOM was close to 1 and within the 95% confidence interval. Therefore, compositional invariance was established across all subpopulation groups. Then, partial measurement invariance was obtained by establishing configuration and composition invariance, the minimum required to conduct the PLS-MGA.

Evaluation of PLS-MGA results

To verify the moderating effect of the country variable on the factors affecting entrepreneurial intention, we compared the path coefficients obtained after running the model for each country separately (García-Rodríguez et al., 2015). The structural model was evaluated for each subpopulation based on linearity assessment, coefficient of determination (R2), and path coefficient significance (β). Before calculating R2 and β, checking for multicollinearity problems is essential (Hair et al., 2017). Total linearity variance inflation factors (VIFs) were evaluated to do this. The VIF values obtained for Psycho/Mach, Narcissism, PA, PBC, NFA, and EI are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2 shows that Psycho/Mach did not have a significant effect on EI for Türkiye and Kosovo (Türkiye p > 0.201; Kosovo = p > 0.093). One of the interesting results is that while narcissism affects EI significantly in the combined model in Fig. 1, the effect of narcissism on EI is eliminated in the results for Türkiye in Fig. 2 (p > 0.932). In Kosovo, on the other hand, it is seen that narcissism has a significant effect on EI (p > 0.000).

Figure 2 shows that Psycho/Mach did not significantly affect EI for Türkiye and Kosovo (Türkiye: p > 0.201; Kosovo: p > 0.093). One of the interesting results is that while narcissism affects EI significantly in the combined model in Fig. 1, the effect of narcissism on EI is eliminated in the results for Türkiye in Fig. 2 (p > 0.932). In Kosovo, on the other hand, narcissism has a significant effect on EI (p < 0.000).

After evaluating the measurement and structural model, a non-parametric test, Henseler et al.'s (2016) PLS-MGA, was used to assess the similarities and differences between the groups' path coefficients. In this method, if the p-value is less than 0.05 or greater than 0.95, there is a significant 5% difference between the two sub-dimensions in specific path coefficients. The result of the PLS-MGA p-values in Table 8 shows a critical group difference in five of the sub-dimensions. According to the Bootstrap MGA results of the structural equation model in Table 8, the country variable is a moderator for the following modes of influence: Narcissism to EI, PA to EI, Psycho/Mach to PBC, Psycho/Mach to NFA, and Narcissism to PA. The effect from Psycho/Mach to NFA was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The moderator effect analysis shows differences between countries in the relationships between these variables, supporting H10. Therefore, the results show that the country variable moderated in only five effect pathways for all variables.

Conclusion and implications

Theoretical implications

The primary aim of this study was to examine the impact of dark triad personality traits, such as psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism, on entrepreneurial intentions. It also aimed to explore the mediating role of PA, PBC, and NFA in the relationship between dark triad traits and entrepreneurial intentions, as well as the moderating role of the country. We included a sample of 701 nascent entrepreneurs from Turkey (n = 368) and Kosovo (n = 333), which are at different levels of development and have distinct cultural settings.

Our research makes three theoretical contributions to the literature. Firstly, we found that only narcissism positively influences entrepreneurial intentions when compared to psychopathy and Machiavellianism. These findings align with previous studies on the impact of narcissism on entrepreneurial intentions (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Crysel et al., 2013; Foster et al., 2009; Gao & Huang, 2022; Hmieleski & Lerner, 2016; Mathieu & St-Jean, 2013) and do not support other studies showing that other personality traits (e.g., Machiavellianism and psychopathy) affect entrepreneurial intentions (Brownell et al., 2021; Do & Dadvari, 2017; McLarty et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2019). The results related to narcissism indicate the need for further examination of the effects of dark triad personality traits on entrepreneurial intentions (Hoang et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019). Therefore, our findings emphasize the importance of a psychological perspective in entrepreneurship research (DeNisi & Alexander, 2017; De Pillis & Reardon, 2007; Zhao et al., 2010).

There could be possible explanations for our findings related to psychopathy and Machiavellianism. Individuals with psychopathy, characterized by a lack of empathy, and Machiavellianism, characterized by manipulation, may not possess the necessary traits to have entrepreneurial intentions (Hmieleski & Lerner, 2016). As shown in previous studies, this does not mean that individuals with these personality traits lack the intention to pursue an entrepreneurial career or become entrepreneurs (e.g., Brownell et al., 2021; Kramer et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2019). These findings highlight the importance of examining the impact of education and interventions to prevent these individuals from failing (DeNisi & Alexander, 2017) and to increase the likelihood of turning their entrepreneurial intentions and aspirations into actual entrepreneurial actions.

Our findings also support the hypotheses regarding the negative impact of psychopathic and Machiavellian personality traits on motivational dynamics (PA, PBC, NFA). Our results are consistent with previous research findings (Brownell et al., 2021; Sayal & Singh, 2020). Additionally, our findings regarding the positive effects of narcissism on motivational dynamics are supported as well. We corroborate the results of past studies on this relationship (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Foster et al., 2009; Gao & Huang, 2022; Hmieleski & Lerner, 2016; Hoang et al., 2022; Kramer et al., 2011). These results indicate that the dark triad personality traits significantly influence individuals' motivational orientations on a psychological basis.

Moreover, we found that motivational dynamics positively influence entrepreneurial intentions. In this context, we confirm the results of previous research on PA (Bueckmann-Diegoli et al., 2021; González-Serrano et al., 2018; Romero-Colmenares & Reyes-Rodríguez, 2022), PBC (Romero-Colmenares & Reyes-Rodriguez, 2022), and NFA (Akhtar et al., 2020; Bağış et al., 2023; Ibidunni et al., 2020; Karimi et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021). In this regard, we contributed to the importance of the unifying effect of the dark triad, the theory of planned behavior, and the need for achievement theories in entrepreneurship research. These results confirm the combined influence of the dark triad and motivational dynamics on entrepreneurial intentions.

Secondly, our findings indicate that PA, PBC, and NFA partially mediate the relationship between psychopathy/Machiavellianism and entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, the results show that only PBC mediates the relationship between narcissism and entrepreneurial intentions, partially supporting our hypothesis. These findings extend previous studies that used limited individual motivation variables, such as self-efficacy, as mediators (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Gao & Huang, 2022; Mathieu & St-Jean, 2013; Wu et al., 2019). Therefore, we recommend including more individual motivation variables in future research. Additionally, we call for examining which individual motivations best explain the relationship between the dark triad and entrepreneurial intentions and the transition from intentions to actual entrepreneurial behavior.

Finally, regarding the moderating role of the country, our findings indicate that narcissism has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions in both countries (combined sample). By analyzing the impact of personality traits and individual motivations on entrepreneurial intentions in Türkiye and Kosovo, these findings contribute to the emerging yet limited research on dark triad personality traits in the field of entrepreneurship within different institutional contexts (Klotz & Neubaum, 2016; Miller, 2015, 2016).

Additionally, the multi-group analyses indicate that the country moderates the relationships between narcissism and entrepreneurial intentions, personal attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions, psychopathy and perceived behavioral control, and personal attitudes with the need for achievement and narcissism. These findings contribute to the literature on the debate about whether the narcissistic personality trait differs across cultures (West and East) or levels of development (Cai et al., 2021; Do & Dadvari, 2017; Mathieu & St-Jean, 2013; Wu et al., 2019). A possible explanation for these differences is that narcissistic new entrepreneurs may face uncertainty in the Kosovo sample due to the institutional context. These new entrepreneurs can be characterized as 'reluctant new entrepreneurs' driven by their employment situations and forced to start businesses. When environmental complexity is higher, it strengthens the effect of narcissism on entrepreneurial intentions (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021), and they take risks when they perceive positive outcomes from their behaviors (Foster et al., 2009). Although these findings provide a new perspective on the subject, further research is needed using the country as a moderating variable in similar institutional and cultural environments to determine whether the level of development of a country reflects personality traits (Johnson, 2020; Jonason et al., 2019). Based on these results, our study contributes to the literature by responding to calls to examine individuals from different cultural backgrounds regarding the dark triad, motivational dynamics, and entrepreneurship (Al-Ghazali & Afsar, 2021; Wu et al., 2019).

Policy and managerial implications

Based on the findings of this study, we provide several practical contributions for policymakers and managers. The first implication is for educational institutions to develop entrepreneurial intentions by considering students' dark triad personality traits and motivational dynamics. This can be done in cooperation with policymakers to design curricula for entrepreneurial education based on students' personality traits. This is important because such training would not only help prevent nascent entrepreneurs with dark triad personality traits from failing but also provide them with managerial skills to mitigate the negative effects of these traits (DeNisi & Alexander, 2017). Another policy implication for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) relates to training on transitioning from intentions to actual entrepreneurial behavior. This includes training on obtaining funds, developing business ideas, building and maintaining networks, and other skills that would accelerate the process from intention to actual entrepreneurial behavior.

Furthermore, to encourage the development of start-ups, it is important to design measures to promote and support individuals with dark triad personality traits in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) by combining the abovementioned strategies. HEIs are recommended to create an environment encouraging individuals to move from intention to action through positive synergy and coordination with successful business owners. Such a positive environment may stimulate start-up creation, change perceptions, and enhance the status of personality traits in these settings (Frank et al., 2007). Consequently, the entrepreneurial education and the environment created could mitigate the potential negative impact of dark triad personality traits and alleviate doubts about starting a business. These environments and entrepreneurial education may be crucial in raising awareness among individuals with these personality traits (McLarty et al., 2023).

The third implication relates to encouraging positive behaviors among nascent entrepreneurs with dark triad personality traits and preparing training content to modify their negative behaviors (Do & Dadvari, 2017). In this vein, governments and higher education institutions need to be cautious when allocating grants and avoid supporting "fast-life" entrepreneurs, who may not use resources wisely, resulting in fewer long-term social benefits.

The final implication is related to firm managers. The top management team should be aware of the entrepreneurial intentions of middle managers and employees with dark triad personality traits. Middle-level managers with these traits are likely to influence new investment decisions (Pradeep et al., 2024). However, the intrapreneurship of employees with such personality traits can be effective. Managers who direct these employees' entrepreneurial intentions can produce beneficial results for the firm. Therefore, the top management team should identify managers and employees with dark triad personality traits. By organizing entrepreneurship training programs, managers can motivate employees based on their personality traits and maximize their potential for entrepreneurship and innovation. Our study findings suggest that individuals with narcissistic personality traits have higher entrepreneurial intentions. Firm managers can target these individuals, increase their entrepreneurial intentions, and motivate them to start a business (Shirokova et al., 2023).

Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations. The first limitation is that it employed a cross-sectional design to examine the impact of the dark triad on entrepreneurial intentions and the mediating role of individual motives, using the country as a moderating variable. However, dark triad personality traits are complex phenomena. Our study found that only narcissism influences entrepreneurial intentions, whereas psychopathy and Machiavellianism had no impact. This impact may change over time, and cross-sectional studies do not capture these temporal changes. Therefore, we recommend that future studies use a longitudinal design to examine how perceptions of dark triad personality traits evolve. Additionally, we suggest more qualitative studies, as they may provide in-depth insights into the nature of dark triad personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions.

The second limitation is that the sample consists of nascent entrepreneurs. These findings provide limited generalizability for established entrepreneurs, as nascent entrepreneurs are in the early stages with insufficient personal and professional experience (Altinay et al., 2021). Therefore, for future research, we recommend analyzing dark triad personality traits, examining how intentions evolve into actions, and investigating the role that dark triad personality traits play during this evolution.

The third limitation of this study is that we focused only on nascent entrepreneurs' dark triad personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions. However, the entrepreneurial behavior of entrepreneurs or the transition from intentions to actual entrepreneurial actions was outside the scope of this study (Kramer et al., 2011). Although intentions are a significant predictor of entrepreneurial behavior (Hmieleski & Lerner, 2016), we recommend that future studies examine how individuals with dark triad personalities succeed in making the transition from intentions to real entrepreneurial actions. Furthermore, we suggest that future studies examine the impact of dark triad traits on nascent entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial outcomes, such as entrepreneurial success (DeNisi & Alexander, 2017).

The last limitation concerns the use of the country as a moderating variable. Our study did not include formal and informal institutional variables or their impact on nascent entrepreneurial personality traits. We recommend that future studies examine how, when, and to what extent institutional settings influence dark triad personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions. Additionally, they should explore how formal and informal institutional settings play a ‘push’ or ‘pull’ role in transitioning from intentions to actual entrepreneurial behavior and actions. We encourage scholars to include institutional environment variables in analyzing the dark triad and entrepreneurship. As our study found, although narcissism had a positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions in both countries, when we controlled for the country as a moderating variable, the effect of narcissism was higher in Kosovo compared to Turkey.

References

Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 27–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Akhtar, S., Hongyuan, T., Iqbal, S., & Ankomah, F. Y. N. (2020). Impact of Need for Achievement on Entrepreneurial Intentions; Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 10, 114–121. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1006.2020.101.114.121

Al Halbusi, H., Soto-Acosta, P., & Popa, S. (2023). Analysing e-entrepreneurial intention from the theory of planned behaviour: the role of social media use and perceived social support. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19, 1611–1642.

Al-Ghazali, B. M., & Afsar, B. (2021). Narcissism and entrepreneurial intentions: The roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and environmental complexity. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 32, 100395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2020.100395

Al-Mamary, Y. H. S., Abdulrab, M., Alwaheeb, M. A., & Alshammari, N. G. M. (2020). Factors impacting entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia: Testing an integrated model of TPB and EO. Educ&train, 62(7/8), 779–803.

Altinay, L., Madanoglu, G. K., Kromidha, E., Nurmagambetova, A., & Madanoglu, M. (2021). Mental aspects of cultural intelligence and self-creativity of nascent entrepreneurs: The mediating role of emotionality. Journal of Business Research, 131, 793–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.048

Aparicio, S., Urbano, D., & Audretsch, D. (2016). Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 102, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.04.006

Asenkerschbaumer, M., Greven, A., & Brettel, M. (2024). The role of entrepreneurial imaginativeness for implementation intentions in new venture creation. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20, 55–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00929-3

Bağış, M., Altınay, L., Kryeziu, L., et al. (2024). Institutional and individual determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: Evidence from developing and transition economies. Review of Managerial Science, 18, 883–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00626-z

Bağış, M., Kryeziu, L., Kurutkan, M. N., Krasniqi, B. A., Hernik, J., Karagüzel, E. S., Karaca, V., & Ateş, Ç. (2023). Youth entrepreneurial intentions: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 17, 769–792. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-01-2022-0005

Baldegger, U., Schroeder, S. H., & Furtner, M. R. (2017). The self-loving entrepreneur: Dual narcissism and entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 9, 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2017.088639

Barroso, N. E., Mendez, L., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2018). Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0313-6

Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., Osiyevskyy, O., & Shirokova, G. (2019). When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96, 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.034

Botha, M., & Sibeko, S. (2024). The upside of narcissism as an influential personality trait: Exploring the entrepreneurial behaviour of established entrepreneurs. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 16, 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-09-2021-0340

Brownell, K. M., McMullen, J. S., & O’Boyle, E. H. (2021). Fatal attraction: A systematic review and research agenda of the dark triad in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 36, 106106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106106

Brownell, K. M., Quinn, A., & Bolinger, M. T. (2024). The triad divided: A curvilinear mediation model linking founder Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy to new venture performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 48, 310–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587231173684

Bueckmann-Diegoli, R., García de los Salmones Sánchez, M. D., & San Martín Gutiérrez, H. (2021). The development of entrepreneurial alertness in undergraduate students. Education + Training, 63, 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2019-0042

Burger, B., Kanbach, D. K., & Kraus, S. (2024). The role of narcissism in entrepreneurial activity: A systematic literature review. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 18(2), 221–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-10-2022-0157

Cai, L., Murad, M., Ashraf, S. F., & Naz, S. (2021). Impact of dark triad personality traits on nascent entrepreneurial behavior: the mediating role of entrepreneurial intention. Frontiers of Business Research in China. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-021-00103-y

Caniëls, M. C. J., & Motylska-Kuźma, A. (2023). Entrepreneurial intention and creative performance – the role of distress tolerance. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19, 1131–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00863-4

Carter, M. Z., Cole, M. S., Bernerth, J. B., Harms, P. D., Wilhau, A., & Palmer, J. C. (2024). Rotten apples in bad barrels: Psychopathy, counterproductive work behavior, and the role of social context. Journal of Organizational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2783

Coşkun, R., Kryeziu, L., & Krasniqi, B. A. (2022). Institutions and competition: Does internationalisation provide advantages for the family firms in a transition economy? J. Entrep. Public Policy, 11, 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-01-2022-0010

Crysel, L. C., Crosier, B. S., & Webster, G. D. (2013). The Dark Triad and risk behavior. Personality & Individual Differences, 54, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.029

Dana, L. P., Crocco, E., Culasso, F., et al. (2023). Business plan competitions and nascent entrepreneurs: A systematic literature review and research agenda. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19, 863–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00838-5

De Pillis, E., & Reardon, K. K. (2007). The influence of personality traits and persuasive messages on entrepreneurial intention: A cross-cultural comparison. Career Development International, 12, 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430710756762

DeNisi, A., & Alexander, B. (2017). The dark side of entrepreneurial personality. In A. Gorkan, C.-P. Tomas, K. Bailey, & K. Tessa (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship (pp. 173–186). USA: Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118970812.ch8

Do, B. R., & Dadvari, A. (2017). The influence of the dark triad on the relationship between entrepreneurial attitude orientation and entrepreneurial intention: A study among students in Taiwan University. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22, 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.07.011

Ephrem, A. N., Namatovu, R., & Basalirwa, E. M. (2019). Perceived social norms, psychological capital and entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate students in Bukavu. Educ&train, 61(7/8), 963–983.

Farrukh, M., Lee, J. W. C., Sajid, M., & Waheed, A. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of individualism and collectivism in perspective of theory of planned behavior. Educ&train, 61(7/8), 984–1000.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Foster, J. D., Shenesey, J. W., & Goff, J. S. (2009). Why do narcissists take more risks? Testing the roles of perceived risks and benefits of risky behaviors. Personality & Individual Differences, 47, 885–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.008

Frank, H., Lueger, M., & Korunka, C. (2007). The significance of personality in business start-up intentions, start-up realization and business success. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19, 227–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701218387

Gao, S.-Y., & Huang, J. (2022). Effect of narcissistic personality on entrepreneurial intention among college students: Mediation role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 774510. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.774510

García-Rodríguez, F. J., Gil-Soto, E., Ruiz-Rosa, I., & Sene, P. M. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions in diverse development contexts: A cross-cultural comparison between Senegal and Spain. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11, 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0291-2

Glenn, A. L., & Sellbom, M. (2015). Theoretical and empirical concerns regarding the dark triad as a construct. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29, 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2014_28_162

González-Serrano, M. H., Gonzalez-Garcia, R. J., Carvalho, M. J., & Calabuig, F. (2021). Predicting entrepreneurial intentions of sports sciences students: A cross-cultural approach. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 29, 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100322

González-Serrano, M. H., Valantine, I., Hervás, J. C., Pérez-Campos, C., & Moreno, F. C. (2018). Sports university education and entrepreneurial intentions: A comparison between Spain and Lithuania. Education + Training, 60, 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2017-0205

Government of Kosovo. Economic Reform Programme 2022–2024 Kosovo. https://mf.rks-gov.net/desk/inc/media/23D2D3B1-81C1-41FE-B6C0-2D5C739A6F69.pdf. Accessed 7 Jul 2022.

Grijalva, E., & Newman, D. A. (2015). Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): Meta-analysis and consideration of collectivist culture, Big Five personality, and narcissism’s facet structure. Applied Psychology, 64, 93–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12025

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31, 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Harms, P. D., Patel, P. C., & Carnevale, J. B. (2020). Self-centered and self-employed: Gender and the relationship between narcissism and self-employment. Journal of Business Research, 121, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.028

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116, 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hmieleski, K. M., & Lerner, D. A. (2016). The dark triad and nascent entrepreneurship: An examination of unproductive versus productive entrepreneurial motives. Journal of Small Business Management, 54, 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12296

Hoang, G., Luu, T. T., Le, T. T. T., & Tran, A. K. T. (2022). Dark triad traits affecting entrepreneurial intentions: The roles of opportunity recognition and locus of control. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 17, e00310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2022.e00310

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values. Sage.

Honig, B., & Samuelsson, M. (2012). Planning and the Entrepreneur: A Longitudinal Examination of Nascent Entrepreneurs in Sweden. Journal of Small Business Management, 50, 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2012

Hu, R., Wang, L., Zhang, W., & Bin, P. (2018). Creativity, Proactive Personality, and Entrepreneurial Intention: The Role of Entrepreneurial Alertness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 951. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00951

Ibidunni, A. S., Mozie, D., & Ayeni, A. W. A. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial characteristics amongst university students: Insights for understanding entrepreneurial intentions amongst youths in a developing economy. Education + Training, 63, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2019-0204

Johnson, L. K. (2020). Narcissistic people, not narcissistic nations: Using multilevel modelling to explore narcissism across countries. Personality and Individual Differences, 163, 110079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110079

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22, 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

Jonason, P. K., Okan, C., & Özsoy, E. (2019). The dark triad traits in Australia and Turkey. Personality & Individual Differences, 149, 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.058

Jonason, P. K., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J., Sedikides, C., Campbell, W. K., Gebauer, J. E., & Yahiiaev, I. (2020). Country-level correlates of the dark triad traits in 49 countries. Journal of Personality, 88, 1252–1267. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12569

Kara, A., & Dheer, R. J. (2023). The relationship between culture and entrepreneurship: The role of Trust. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19, 1803–1833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00901-1

Kara, O., Altinay, L., Bağış, M., Kurutkan, M. N., & Vatankhah, S. (2024). Institutions and macroeconomic indicators: Entrepreneurial activities across the world. Management Decision, 62, 1238–1290. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2023-0490

Karagüzel, E. S., & Bağış, M. (2021). Relationship of the Positive Psychological Capital and Organizational Justice Perception: Comparison of Turkey and Kosovo. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int., 13, 103–114.