Abstract

Financial inclusion, which means the promotion of an affordable, timely and adequate access to a wide range of regulated financial products and services, as well as its use by all the segments of the society, is a high potential tool that may contribute to the development of the rural environment, while its absence could in turn cause a major harm. The availability of a sufficient level of financial literacy, which can be defined as the ability to understand financial concepts and risks, as well as the motivation and trust to use it when making financial decisions, is frequently deemed to be a need to reach financial inclusion by the academic literature. Financial literacy is, in turn, influenced by different variables, such as the degree of rural or urban predominance, the level of education and the available income in the household. This paper analyses the impact of such factors on financial literacy. The degree of financial literacy tends to be lower in rural environments, with limited incomes and poorer educational backgrounds, which creates a vicious circle that potentially worsens the situation of what has been called the empty Spain. Considering the importance of financial literacy to reach financial inclusion, we remark the potential of digital transformation as a valuable tool to break this negative trend in the less populated Spanish regions, and so, a cornerstone for the regenerative development of the Spanish rural areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

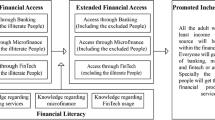

Financial inclusion (FI), defined as the economic state in which no individual is denied access to basic financial services for efficiency reasons (Mialou et al., 2017), is a notable concern for the main bodies that regulate the international economy. For example, the G-20 underlines the strategic importance of financial inclusion of older people and the challenges that lie ahead in order to achieve it (GPFI, 2020). According to the World Bank, about 1.7 billion adults were unbanked and lacked a basic transaction account at the end of 2017 due to issues such as affordability, costs, difficulty in accessing institutions, lack of financial literacy or distrust of existing financial service providers (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

The benefits of FI are broad, as Burgess and Pande (2005) point out: it reduces income inequality and poverty, facilitates better financial decisions about household finances, increases the level of savings, fosters productive investment and women's empowerment, and is the engine of economic growth. Financial exclusion, on the other hand, can lead to a poverty trap and greater inequality (Beck et al., 2007). This problem affects not only developing countries, but also disadvantaged regions and groups in developed countries (Demirgüç-Kunt & Klapper, 2013).

One of the prerequisites for accessing these products and services is financial literacy, which "measures how well an individual can understand and use information related to personal finance" (Huston, 2010: 306). According to Van Rooij et al. (2011), the problem of the lack of financial literacy mainly affects people who are less educated, older, or female. Ethnic and regional differences are also factors to be taken into account (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011). The identification of the population groups with the lowest level of financial competence is a necessary starting point for the design of programmes aimed at understanding financial products, which could then be extended to all sectors of the population, and especially to rural areas and the most vulnerable groups. In this way, we will be able to assess the importance of financial literacy in achieving inclusion and, consequently, alleviating the disadvantages faced by the modern-day Emptied Spain.

The digital transformation of the financial industry could be a solution. We are currently witnessing a sharp rise in the presence of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in our daily lives. The financial industry is not an exception, experiencing a dramatic change in both the supply side (new products, agents and services) and the demand side (consumer behaviour). Digital access to financial services can boost the financial inclusion of the most vulnerable (Liu et al., 2021), generating what has been called digital financial inclusion (DFI) (Gallego-Losada et al., 2023). Therefore, DFI could be critical to overcome obstacles of cost, distance and transparency to satisfy the financial needs of traditionally excluded collectives (Kulkarni & Gosh, 2021).

This article discusses the role of financial literacy as a means to achieve inclusion. In order to meet this goal, differences in financial literacy are studied according to the predominance of rural areas, gross income, or education received. For this purpose, data from the latest Survey on Financial Competencies (ECF by its Spanish name) published by the Bank of Spain is used. Finally, the transformative potential of the adoption of ICTs in the financial industry is presented as the most powerful tool to change this dynamic, breaking the vicious circle of financial exclusion.

Therefore, the main goal of this research is to analyse the separate and joint influence of the level of education, the availability of incomes and the residence in a rural area of a developed country on the degree of financial literacy of an individual. It will be proposed that these variables act together reinforcing each other, leading to a financial literacy divide between urban areas, where many people have greater incomes and can access higher levels of training, and rural regions, creating a vicious cycle where the rural predominance of a region conditions negatively the financial inclusion of its population.

This is one of the first works of its kind to be performed in developed countries: the vast majority of studies which analyse differences in financial inclusion and financial literacy, and their influence on regional development, have been carried out in developing nations. Consequently, this study boards a research gap in the academic literature, providing an appropriate starting point for proposals to promote FI in rural areas of developed countries.

The paper is organised as follows. First, FI is defined and the importance of this objective for the improvement of individual and social welfare is analysed. Second, this research defines financial literacy and highlights its essential role in promoting FI, putting forward different hypotheses on the factors that can condition financial literacy and, through it, FI. In the following section, the methodology of the empirical study is presented, followed by the results and their discussion. The paper closes with conclusions highlighting the potential of digital tools to foster FI.

Financial inclusion

Financial inclusion is now a major concern for some of the main bodies that regulate the international economy. According to the World Bank (2014), FI refers to the proportion of households and firms using financial services. The International Monetary Fund defines it as the use of and access to financial services at an affordable price for the most vulnerable segments of society (Sahay et al., 2015). From an academic perspective, FI has been defined as the economic state in which no individual is denied access to basic financial services for efficiency reasons (Mialou et al., 2017).

FI has beneficial effects in terms of individual and social welfare (Demirgüç-Kunt & Levine, 2009). According to Burgess and Pande (2005), greater access to formal financial services reduces income inequality and poverty (Honohan, 2008; Park & Mercado, 2018), facilitates better financial decisions about household finances (Mani et al., 2013), increases the level of savings (Aportela, 1999; Ashraf et al., 2010), fosters productive investment (Dupas & Robinson, 2009) and women's empowerment (Ashraf et al., 2010), and is the engine of economic growth (Pradhan & Sahoo, 2021; Sethi & Acharya, 2018). FI is deeply connected to poverty reduction (Chao et al., 2021; Neaime & Gaysset, 2018). In addition, FI is an effective mechanism for increasing well-being in old age (Nam & Loibl, 2021).

Full FI means providing all households with access to a range of financial services, including payment, savings, credit, insurance, as well as sufficient support to help clients make good decisions for themselves (Goland et al., 2010). Conversely, if households or individuals are deprived of access to or enjoyment of the benefits of such financial products and services, they are in a situation of financial exclusion (Kumar & Mishra, 2011). Financial exclusion can lead to a poverty trap and greater inequality (Beck et al., 2007). Moreover, this problem affects not only developing countries, but also disadvantaged regions and groups in developed countries (Demirgüç-Kunt & Klapper, 2013).

One of the first instruments used to promote FI was microcredit or microfinance. According to Morduch (1999), microcredits are defined as small loans granted to people in a situation of economic exclusion. Despite their peak, they have been heavily criticised for their speculative nature (very high interest rates). This formula has evolved into FI, which is not limited to obtaining a credit within a certain time frame, but a broader strategy to underpin financial services as a tool for economic and social development.

Financial exclusion is attributed to various factors related to the supply and demand of financial services. According to Schuetz and Venkatesh (2020), the main obstacles to achieving FI are a lack of geographic access, high costs of using products and services (interest rates, fees), unavailability of suitable products to applicants (credit history) and a lack of financial literacy.

On the supply side, the financial sector is concentrated where there is greater access to ICT infrastructure to receive these services (Lashitew et al., 2019; Pradhan et al., 2018), as well as at higher income levels, covering only certain segments of the population (Adetunji & David-West, 2019; Zhang & Posso, 2019). However, financial services are generally inaccessible to lower-income, social or ethnic groups (Hannig & Jansen, 2010). On the other hand, the analysis of the demand side deals with the consumption of these services, considering the regularity and frequency of their use over time (Claessens, 2006) according to socio-economic characteristics (income, education, race, etc.). In this sense, low income is often seen as a barrier to access and use of certain financial products, which are displaced by less sophisticated ones.

On the other hand, people with less education often do not know how to take advantage of the benefits of managing and using financial services, and may make inappropriate decisions about their savings, debt and investments that can be detrimental to their own and their family’s well-being. Collins et al. (2009) have identified as a primary objective of FI the provision of financial capabilities and skills to poor and vulnerable people in order to improve the management of their portfolios, which means to increase their financial literacy. In this sense, the relatively low level of education in rural areas could hinder the use of financial services, weakening the positive effects of FI (Ardic et al., 2011; Cole et al., 2011), and increase inequalities or gaps between rural and urban areas (Young, 2013).

Access to formal financial services is a critical factor behind the financial exclusion of rural regions of the population. For geographical reasons, coverage of these services is often lower in rural than in urban areas (Allen et al., 2016). According to the World Bank, around 1.7 billion adults still remain unbanked in the world, i.e. they do not have an account at a financial institution or through a mobile money provider (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). In this regard, Lyons and Kass-Hanna (2019) found that financially vulnerable people were less likely to have access to financial services. The ability to have a bank account is the first step towards greater FI, because it enables people to use broader financial services (Patwardhan et al., 2018). Financial access through banking allows rural regions to save money to protect themselves against everyday risks, promote their economic activities, and anticipate future financial needs (Sun, 2018; Sinha et al., 2018).

Another relevant element to foster FI is the design of a regulatory framework that promotes the construction of an independent and competitive financial system, thus reducing transaction costs through innovation and competition, while protecting and taking into account the needs of the excluded (Honohan & Beck, 2007). Financial institutions, both formal and informal, are responsible for providing financial services to financially excluded individuals (Hussain et al., 2018; Zulkhibri, 2016). In this sense, governments and supranational organisations have a responsibility to promote FI through the development of an adequate set of public policies in order to alleviate economic inequality.

Finally, the digital transformation of the financial industry could solve different unbalances at the same time, providing rural regions with remote access, overcoming efficiency barriers and making many financial opportunities accessible to the vulnerable collectives (Ozili, 2018).

Financial literacy and its role in financial inclusion

As noted above, authors such as Collins et al. (2009) indicate that financial literacy is the main determinant of individual FI. Financial literacy, “measures how well an individual is able to understand and use information related to personal finance” (Huston, 2010: 306). According to the OECD (2015), financial education is defined as “the process by which financial investors and consumers improve their understanding of financial products, concepts and risks and, through information, instruction and/or objective advice, develop the skills and confidence to become more aware of financial risks and opportunities, to make informed decisions, to know where to turn for help, and to take other effective actions to improve their financial well-being”. Financial literacy also means having the right knowledge to make the correct decisions when choosing financial products and services.

Financial literacy improves individuals’ understanding of different financial products and concepts. Financial education involves relying on formal financial methods to make sound financial decisions (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011; Lusardi, 2015). Individuals with low levels of financial literacy are more likely to make mistakes and be victims of fraud (Engels et al., 2020).

Moreover, financial literacy is not only critical for individuals, but affects different collectives and the society as a whole. In this sense, in a globalised and increasingly digital world, financial literacy is a source of positive externalities for inclusive growth (Lusardi, 2015). Academia and international organisations agree in recognising financial literacy as a decisive tool to reduce the social and financial gap in the population (Grohmann et al., 2018; Kodongo, 2018; Koomson et al., 2019). In this way, financial literacy is not only of individual benefit, but it is also the cornerstone for achieving FI.

A bibliometric analysis of academic studies published over the last twenty years shows that a large part of the population lacks financial literacy when dealing with their personal finances and planning for retirement. In the current context, in the midst of technological transformation, with a clear increase in life expectancy, and where work is a scarce commodity, the involvement of individuals in the management of their personal finances becomes critical (Gallego-Losada et al., 2022).

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has led to an economic crisis in which many individuals have become aware of the importance of having the necessary skills to manage unexpected adverse situations. In general, economic crises are associated with high interest rates and fees, and default credits, so a high degree of financial literacy means having elements of resilience that lead to a reduction in the estimated recovery time of the economic situation (Lusardi & Tufano, 2015). In this sense, according to Sahay et al. (2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has been an ideal moment for FI to be accelerated and enhanced through increased financial literacy and digital transformation.

The following hypotheses will be addressed in our study, where the lack of financial literacy is associated with age, socio-economic status, level of education and the degree of rurality of the environment (Lusardi, 2008).

Several authors (Cucinelli et al., 2019) conclude that not only socio-economic and socio-demographic conditions, but also the regional and/or rural context influence the degree of financial literacy. A study in public high schools in Indiana (USA) showed that financial literacy is higher in urban areas than in rural ones (Valentine & Khayum, 2005). Azeez and Banu (2021), in turn, found out that the degree of financial literacy of the inhabitants of rural areas of India is consistently lower than in urban ones. Murendo and Mutsonziwa (2017), in a study carried out in Zimbabwe, reached the same conclusion: Individuals residing in rural areas exhibit lower financial literacy compared to their urban counterparts, so financial services interventions should specifically target rural communities to enhance financial literacy. Faulkner et al. (2019) remark that the proximity to urban areas influences severely the degree of financial literacy in Ireland. Finally, Santoso et al. (2016), found out that people living in rural areas exhibit lower levels of financial literacy compared to those dwelling in urban zones.

Thus, we put forward the following hypothesis:

-

H1. The level of financial literacy will be lower in regions where rural areas are more predominant.

The level of disposable income and wealth has often been associated with the degree of financial literacy in the academic literature. In this way, Santini et al. (2019) and Campbell (2006) point out that people with lower incomes often have, at the same time, a lack of financial literacy. Monticone (2010) found out that wealth has a positive, but relatively small, effect on the level of financial literacy. Lusardi and Tufano (2015) argue that financial literacy related to debt and loans increases strongly with available incomes. Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) stated that, though financial illiteracy is widespread in the population, it particularly impacts some vulnerable collectives, including low-income households. Using the data collected by the OECD/INFE survey, Atkinson and Messy (2012) stated that low incomes are associated with low financial literacy levels.

This leads us to propose the following hypothesis:

-

H2. People with higher levels of income and wealth have a higher level of financial literacy.

Another factor that has been directly linked to financial literacy is the level of education. Santini et al. (2019) state that people who have not been able to access higher levels of education will frequently lack financial literacy. Following Campbell (2006), individuals who are less educated are less likely to refinance their mortgages in times of falling interest rates, due to a lack of capacity to do so. The study of Santoso et al. (2016) reveals that there is a strong correlation between lower degrees of financial knowledge and inclusion and lower levels of education, frequently associated with the eldest. Klaper and Lusardi (2020) stated that women, poor adults and less educated people may fall in a financial knowledge divide not only in developing countries, but also in developed ones.

Therefore, we can formulate the following hypothesis.

-

H3. People with higher levels of education have a higher level of financial literacy.

Commonly, people affected by one matter of exclusion are often simultaneously affected by other causes (Koku, 2015). Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) remarked that financial illiteracy may create a divide, especially affecting people who gather different exclusion factors, such as low incomes and low educational attainments. Thus, factors such as education and income levels determine financial exclusion in rural areas within developed countries, making individuals more vulnerable in accessing financial services (Fernández-Olit et al., 2019). Morgan and Trinh (2019), when analysing the determinants of financial literacy in Cambodia and Vietnam, stated that educational level, income, age, and occupational status are the most important ones. Henchoz (2016) states that financial illiteracy is normally concentrated on specific collectives, including the less educated, the people who live in rural areas and the most vulnerable citizens. Loke et al. (2022) found that socio-demographic factors such as age, education and income, as well as the specific region where the participant in the survey dwells, influence the degree of financial literacy. Finally, Ansar et al. (2023) state that unbanked people and financially illiterate tend to belong to some collectives: poor adults, lees educated people and those living in rural areas.

This leads us to formulate a final hypothesis.

-

H4. The effects of income level, level of education, and residence in a rural area reinforce each other, leading to greater financial exclusion in rural areas with lower levels of education and income.

Methodology

In order to test the hypotheses, data from the Spanish Survey of Financial Competencies, conducted in 2016 for the last time, have been used. According to the Bank of Spain, this survey “is a joint initiative of the Bank of Spain and the National Securities Market Commission within the framework of the Financial Education Plan and included in the National Statistical Plan” (Bover et al., 2019). The same website highlights that “the Survey of Financial Competencies is part of an international project, coordinated by the OECD’s International Financial Education Network (INFE), which allows us to compare the financial skills of the Spanish population with those of a wide range of countries”. OECD-INFE survey is the most frequent data source used when analysing the degree of financial literacy, its determinants and its consequences. The studies based on this data have been widely cited by the academic literature (Atkinson & Messy, 2012; Cupák et al., 2018; Morgan & Trihn, 2019; De Beckker et al., 2020).

The content of the survey is quite broad and, in addition to assessing the financial literacy of respondents, by means of a questionnaire similar to that used in other OECD countries, it also assesses other aspects relating to the use of financial products and services, the saving and spending capacity of the households surveyed and whether they have fallen in financial fraud. The survey also includes different ranking questions. The micro-data from this study allowed us to find out, for each of the respondents, their level of financial literacy, along with their age, income, and education. Unfortunately, although the province is asked, only the Autonomous Community of residence is made public.

Regarding financial literacy, questions about investment situations, financing, or the use of financial products—most of which are multiple-choice ones—are used to assess this construct. The questionnaire also includes some questions aimed at assessing respondents’ reading comprehension and their ability to understand graphics. Financial literacy questions evaluate different aspects, such as calculation ability, economic general knowledge, the value of money along the time (considering both compound interest rates and inflation), risk diversification, profitability… For the purposes of this research, only questions about economics and finance have been considered, with one point awarded for those answered correctly and zero points in any other case. Each respondent could reach a maximum score of 14.

As regards the respondent’s highest level of education, shown in Table 1, the categories included in the survey, from lower primary studies to PhD, are similar to those used by the National Statistics Institute of Spain in other surveys. This table also includes gross annual household income, for which different ranges have been established, which show some differences compared with other national surveys, in order to harmonize them with the ones used in other OECD countries.

Traditionally, the assessment of the degree of rurality of a region has been carried out using methodologies based on the population density of the areas analysed. These methodologies have been revised and refined over time in order to design a common framework for the OECD.

As Rosell Foxá and Viladomiu Canela (2020) point out, a rural municipality was traditionally considered to be one with less than 150 inhabitants/km2, while a rural region was one in which rural municipalities predominated, and an urban region was one with less than 15% of rural municipalities. This type of classification has been criticized because, as Amorós i Ros and Vilafranca (2004) state, perhaps it would be more appropriate to use a broader set of indicators which, in addition to population density, would take into account other variables, such as population growth, ageing and predominance of agricultural activity.

In 2017 Eurostat modified its methodology to use 1 km2 grid cells as a starting point, taking into account both population density (urban cells are those with more than 300 inhabitants/Km2) and proximity to highly populated cells. Depending on the predominance of one or the other kind of cells, each unit at LAU2 level in Eurostat terminology (corresponding to municipalities in Spain) has been classified as city (higher population density), town or suburb (intermediate level) and rural area (lower density). Based on the predominance of one or another kind of municipality in a region, Eurostat offers a classification of the rural predominance of European regions at NUTS-3 level, which, in Spain, corresponds to the provinces and islands, considering three levels: 1, urban regions (less than 20% of their population lives in rural cells); 2, intermediate regions; and 3, rural-dominated regions (more than 50% of their population living in rural cells).

As we have indicated, the Survey of Financial Competencies does not offer the classification by province in the microdata, but includes a field relating to the Autonomous Community. Therefore, based on the classification of NUTS-3 regions offered by Eurostat, and following the classification criteria of the OECD, the degree of rurality of the Spanish Autonomous Communities has been assessed, calculating the average of the OECD classification of the different provinces included in each Spanish region, achieving the results shown in Table 2. As can be seen, the most common situation is an intermediate level, with both urban predominance and rural predominance being less frequent.

Results and discussion

The first proposed hypothesis considers that the level of financial literacy will be lower in regions where rural areas are more predominant, due to the factors mentioned above, including proximity to financial resources. Table 3 shows the average values of financial literacy obtained in the three different types of regions, where differences are observed in favour of those with a greater urban predominance compared with those with a greater degree of rurality.

In order to verify this hypothesis, a one-factor ANOVA analysis (the level of rural predominance of the region analysed) was carried out. In this variable, the significance of Levene’s statistic is greater than 0.05, so we can accept the hypothesis of equality of variances and, consequently, use the ANOVA test. The results of this test, shown in Table 4, highlight how the difference in the level of financial literacy between the regions is significant, which allows us to verify the first hypothesis. Although the differences between the three groups can be considered statistically significant, an additional Scheffe test shows how the distances are especially relevant between urban-dominated regions (1) and rural-dominated regions (3), which reinforces the result obtained, according with the dominant theory.

The second hypothesis deals with the influence of income level on the degree of financial literacy. The descriptive statistics in Table 5 show how, using an intuitive approximation, the difference exists and is apparently noteworthy between each of the ranges and the next one, which points to the existence of the differences stated in the hypothesis.

In order to test the second hypothesis, a mean difference test has been performed. However, in this case, the significance of Levene’s statistic, lower than 0.05, did not allow us to accept equality of variances, so instead of the ANOVA test we opted to use robust tests of equality of means, the Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests. As expected, the results (Table 6) show that the differences according to income level are significant, so we can accept the second hypothesis.

The third hypothesis puts forward the influence of the level of education on the degree of financial literacy. Table 7 shows the descriptive statistics, which again reveal the existence of the differences discussed. In fact, we can affirm that this variable generates the most striking differences, with the most outstanding cut-off point being those who have a level of education higher than the compulsory level, which currently stands at the Junior High in Spain.

As happened with the second hypothesis, a test of the difference of means between the groups was performed. The significance of Levene’s statistic is again lower than 0.05, so we cannot accept equality of variances, and we must use robust tests of equality of means instead of the ANOVA test. The results (Table 8) show that the differences according to educational level are significant, so we can accept the third hypothesis.

Finally, to test the fourth hypothesis, we carried out a K-means cluster analysis, classifying respondents according to three variables: level of education, level of gross income, and population density in the region. After testing with different numbers of clusters, the most significant differences occur when taking only two groups, as shown in Table 9. The former is characterised by lower population densities (and therefore more rural environments), as well as lower levels of income and education. The second group corresponds to respondents with higher levels of education and income who live in heavily urban regions (844.53 inhabitants per square kilometre on average).

As can be seen (Table 9), the second group shows a higher average level of financial literacy, with a statistically significant difference at 1%. Thus, the fourth and last hypothesis is also fulfilled, so that these factors reinforce each other.

As we have confirmed, the results allow us to verify the four initial hypotheses of the study: the degree of rurality of the environment, the level of income, and the level of education have a significant influence on people’s financial literacy. Moreover, as also discussed, these variables are mutually reinforcing.

Thus, it is relatively common for people living in predominantly rural environments, in what has been called emptied Spain, to have a lower level of education, which force them to work in lower paid jobs. However, in many cases this does not lead to an apparent loss of purchasing power, as prices in these areas are usually lower than in urban areas. Nevertheless, as we have seen, these people will have a lower degree of financial literacy, resulting in a certain level of financial exclusion.

Conclusions

A society with low levels of FI is undoubtedly an unfair society. Despite the bluntness of this statement, as highlighted in the introduction to this paper, a very large part of the world’s population, and even the inhabitants of developed countries, are not guaranteed the access to financial products and services that we often take for granted in the big cities of the OECD nations. Moreover, a society with low levels of FI is also inefficient, less productive than it should be. As has also been pointed out, FI is a basis for the economic growth of regions and countries, contributing decisively to their development. Thus, understanding the determinants of FI should be a priority for supranational bodies, governments, society and academics.

Some of the factors that have been identified as decisive in achieving FI are the access to financial products and services appropriate to the needs of potential users at an affordable cost. In addition to these, financial literacy plays a decisive role. A person who does not have the necessary skills to understand how a particular financial product (such as a loan) works will tend not to use it, and if s/he does, s/he could be victim of a scam.

There are a number of factors that condition an individual’s financial literacy. As we have seen, income level, educational level, and residence in a predominantly rural environment are associated with lower financial literacy. As has also been indicated, this situation may not, in the very short term, lead to a reduction in purchasing power. However, the consequences in the medium and long term can be negative and, in turn, lead to increased poverty in that environment.

The less financially literate, as we have remarked, have access to fewer financial products and services, which implies a certain degree of exclusion. In addition, they are likely to make poorer financial decisions, which may harm their availability of additional incomes both now (excessive indebtedness, forcing high interest payments) and in the future (inadequate retirement planning). This in turn can lead to a vicious circle, in which the rural environment suffers a deterioration due to the lower disposable incomes of the people who live there.

This study makes a substantial contribution to the state of the art of the academic literature, pioneering the joint analysis of different sociodemographic variables (including the degree of rurality) on the level of financial literacy in developed countries, drawing a picture of a financial literacy divide between urban areas, with an overall higher degree of incomes, education and financial literacy, and rural zones. There is a need for authorities to face this problem, which can be directly related with SDG#4 (quality education) and SDG#10 (reduce inequalities), putting into practice policies and measures that can help to overcome this challenge in what is frequently called the emptied Spain. These actions should not be based only on an individual level, but should rather consider the regional context where less financially literate people live.

Limitations and further research lines

Probably the main limitation of this study stems from the data source used. While the Survey of Financial Competencies is the main dataset on financial literacy available in Spain, and in general in OECD countries, with which it is harmonized, some of the data available is not as complete as could be desirable. In this way, the gross income of each household is established in steps, some of them covering a range of more than 15,000€, which could influence the results of the analysis.

However, the main obstacle is the lack of availability of data on financial literacy at the level of provinces, since the classification of regions according to rural/urban predominance is established at NUTS-3 level, which in Spain is equivalent to provinces or islands. Therefore, we have adapted the Eurostat assessment on the basis of the data available from the Spanish National Statistics Institute. This adaptation, while not inadequate, could reduce the accuracy of the results obtained: we have the perception that, with more precise data, the gap in financial literacy between urban and rural-dominated regions would have been more pronounced.

Another shortcoming of the 2016 edition of the Spanish Survey of Financial Competencies is the lack of specific questions on digital financial literacy. In the current environment, where many financial products and services are increasingly accessed through digital tools, it seems very relevant, and even necessary, to assess respondents’ skills in the use of this channels.

These aspects, however, beyond mitigating the impact of the findings of this study, provide an interesting starting point for further research. Thus, we propose to conduct new surveys that look at both province-based and even population-based data, as well as at respondents’ digital financial literacy.

ICTs applied to the financial sector (Fintech) can dramatically change consumer behaviour and the demand for financial products and services. Some authors have shown how digitalisation can be a milestone in FI, facilitating access to many basic financial products and services for people who were previously excluded from them (Gálvez-Sánchez et al., 2021). The World Bank recognises that the new generation of financial services accessible via mobile phones and the Internet is contributing to FI. It is estimated that, among the world’s unbanked adults, nearly two-thirds (almost 1.1 billion people) have a mobile phone, opening a window of opportunity to accelerate FI through this channel. As Gomber et al. (2017) point out, DFI will enable the sustainability of financial services provided to customers at an affordable cost.

However, in order to benefit from the advances that technology offers, a sound regulatory framework and a minimum level of development of markets and financial infrastructures are still necessary (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). In this way, an effective use of digital financial services requires a certain level of both digital and financial literacy, to grant adequate decisions and prevent customers from making costly mistakes. Some authors point out that mobile apps can attract and lead people with low levels of digital financial literacy to make worse decisions (Georgios et al., 2020). Thus, improving both the provision of digital infrastructure and digital financial literacy are starting conditions for increasing FI in rural areas.

In this way, the vicious circle could be broken, generating a brand-new virtuous circle: better financially educated people with access to a wide range of products and services could increase their purchasing power, which in turn would contribute to slowing down the deterioration of the rural environment. To meet this goal, there is no doubt that some critical issues are the provision of technological and communications infrastructures and digital financial literacy, focused on the population of the so-called emptied Spain.

Therefore, the study of the influence of the different socioeconomic variables (such as wealth, studies, rurality), as well as some other ones (infrastructure availability, regulatory framework) on the level of digital financial literacy can be a very promising topic in the immediate future. This is particularly relevant given that, as we have pointed out before, the digitalisation of financial channels can be a powerful tool to avoid financial exclusion in rural areas. The impact of the phenomenon of digital nomads, which has bloomed since COVID-19 pandemic, on rural societies’ financial inclusion can also be a relevant research topic.

Finally, this paper could also be enriched by an analysis of the financial products and services accessed by respondents. It seems reasonable to think that the same variables that condition respondents’ financial literacy have an equally significant impact on their access to and use of these financial instruments.

References

Adetunji, O. M., & David-West, O. (2019). The relative impact of income and financial literacy on financial inclusion in Nigeria. Journal of International Development, 31(4), 312–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3407

Allen, F., Carletti, E., Cull, R., Qian, J., Senbet, L., & Valenzuela, P. (2016). Resolving the African Financial Development Gap: Cross-Country Comparisons and a Within-Country Study of Kenya. In S. Edwards, S. Johnson, & D. N. Weil (Eds.), African Successes (Vol. III, pp. 13–62). University of Chicago Press.

Amorós i Ros, J. A., & Vilafranca, M. P. (2004). Construcción de la ruralidad en zonas periurbanas y rurales de la provincia de Barcelona. Aplicación piloto en las comarcas interiores. In ¿Qué futuro para los espacios rurales?: [XII Coloquio de Geografía Rural, León 15–17 Septiembre 2004] (pp. 477–486). Universidad de León.

Ansar, S., Klapper, L., & Singer, D. (2023). The importance of financial education for the effective use of formal financial services. Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing, 1(1), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2023.5

Aportela, F. (1999). Effect of Financial Access on Savings by Low-Income People. Ciudad de México, Mexico: Banco de México.

Ardic, O. P., Heimann, M. & Mylenko, N. (2011). Access to financial services and the financial inclusion agenda around the world: a cross-country analysis with a new data set. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 5537. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1747440

Ashraf, N., Karlan, D., & Yin, W. (2010). Female empowerment: Impact of a commitment savings product in the Philippines. World Development, 38(3), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.05.010

Atkinson, A., & F. Messy (2012), “Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD / International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study”, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k9csfs90fr4-en

Azeez, N. A., & Banu, M. N. (2021). Rural-Urban Financial Literacy Divide in India: A Comparative Study of Kerala and Uttar Pradesh. Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 14(4), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.9734/ARJASS/2021/v14i430243

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality and the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

Bover, O., Hospido, L., & Villanueva, E. (2019). The Survey of Financial Competences (ECF): description and methods of the 2016 wave. Banco de España Occasional Paper, (1909).

Burgess, R., & Pande, R. (2005). Do Rural Banks Matter? Evidence from the Indian Social Banking Experiment. American Economic Review, 95, 780–795. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201242

Campbell, J. (2006). Household Finance. Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1553–1604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00883.x

Chao, X., Kou, G., Peng, Y., & Viedma, E. H. (2021). Large-scale group decision-making with non-cooperative behaviors and heterogeneous preferences: An application in financial inclusion. European Journal of Operational Research, 288(1), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2020.05.047

Claessens, S. (2006). Access to financial services: A review of the issues and public policy objectives. The World Bank Research Observer, 21(2), 207–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkl004

Cole, S., Sampson, T., & Zia, B. (2011). Prices or knowledge? What drives demand for financial services in emerging markets? The Journal of Finance, 66(6), 1933–1967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01696.x

Collins, D., Morduch, J., Rutherford, S., & Ruthven, O. (2009). Portfolios of the Poor. Princeton University Press.

Cucinelli, D., Trivallato, P., & Zenga, M. (2019). Financial literacy: The role of the local context. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(4), 1874–1919. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12270

Cupák, A., Fessler, P., Schneebaum, A., & Silgoner, M. (2018). Decomposing gender gaps in financial literacy: New international evidence. Economics Letters, 168, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2018.04.004

De Beckker, K., De Witte, K., & Van Campenhout, G. (2020). The role of national culture in financial literacy: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(3), 912–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12306

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Klapper, L. (2013). Measuring financial inclusion: Explaining variation in use of financial services across and within countries. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2013(1), 279–340. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2013.0002

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S. & Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution, World Bank Publications.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2009). Finance and inequality: Theory and evidence. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 1(1), 287–318. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.financial.050808.114334

Dupas, P. & Robinson, J. (2009). Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Deveiopment: Evidence from a Field Experiment. NBER Working Paper Series, 14693.

Engels, C., Kumar, K., & Philip, D. (2020). Financial literacy and fraud detection. The European Journal of Finance, 26(4–5), 420–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2019.1646666

Faulkner, J. P., Murphy, E., & Scott, M. (2019). Rural household vulnerability a decade after the great financial crisis. Journal of Rural Studies, 72, 240–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.030c

Fernández-Olit, B., Martín Martín, J. M., & Porras González, E. (2019). Systematized literature review on financial inclusion and exclusion in developed countries. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38(3), 600–626. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-06-2019-0203

Gallego-Losada, M. J., Montero-Navarro, A., García-Abajo, E., & Gallego-Losada, R. (2023). Digital financial inclusion. Visualizing the academic literature. Research in International Business and Finance, 64, 101862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101862

Gallego-Losada, R., Montero-Navarro, A., Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. L., & González-Torres, T. (2022). Retirement planning and financial literacy, at the crossroads. A Bibliometric Analysis. Finance Research Letters, 44, 102109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102109

Gálvez-Sánchez, F. J., Lara-Rubio, J., Verdú-Jover, A. J., & Meseguer-Sánchez, V. (2021). Research advances on financial inclusion: a bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 13(6), 3156. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063156

Georgios, K., Evaggelos, D., & Konstantinos, K. (2020). Risk Management after Mergers and Acquisitions. Evidence from the Greek Banking System. Journal of Applied Finance and Banking, 10(3), 105–125.

GPFI Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion. (2020). GPFI. GPFI Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion. https://www.gpfi.org/

Goland, T., Bays, J., & Chaia, A. (2010). From millions to billions: Achieving full financial inclusion. McKinsey and Company.

Gomber, P., Koch, J.-A., & Siering, M. (2017). Digital Finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. Journal of Business Economics, 87(5), 537–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0852-x

Grohmann, A., Klühs, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2018). Does financial literacy improve financial inclusion? Cross country evidence. World Development, 111, 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.020

Hannig, A. & Jansen, S. (2010). Financial inclusion and financial stability. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Henchoz, C., et al. (2016). Sociological Perspective on Financial Literacy. In C. Aprea (Ed.), International Handbook of Financial Literacy. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0360-8_8

Honohan, P. (2008). Cross-country variation in household access to financial services. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(11), 2493–2500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.05.004

Honohan, P. y Beck, T. (2007). Making Finance Work for Africa. Washinton, DC, USA: The World Bank.

Hussain, J., Salia, S., & Karim, A. (2018). Is knowledge that powerful? Financial literacy and access to finance: An analysis of enterprises in the UK. Journal of Small Bussiness and Enterprise Development, 25(6), 985–1003. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-01-2018-0021

Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01170.x

Klapper, L., & Lusardi, A. (2020). Financial literacy and financial resilience: Evidence from around the world. Financial Management, 49(3), 589–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12283

Kodongo, O. (2018). Financial regulations, financial literacy, and financial inclusion: Insights from Kenya. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(12), 2851–2873. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1418318

Koku, P. S. (2015). Financial exclusion of the poor: A literature review. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(5), 654–668. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-09-2014-0134

Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., & Hadley, D. (2019). Intensifying financial inclusion through the provision of financial literacy training: A gendered perspective. Applied Economics, 52(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1645943

Kulkarni, L., & Ghosh, A. (2021). Gender disparity in the digitalization of financial services: Challenges and promises for women’s financial inclusion in India. Gender, Technology and Development, 25(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2021.1911022

Kumar, C. & Mishra, S. (2011). Banking outreach and household level access: Analyzing financial inclusion in India. In 13th Annual Conference on Money and Finance in the Indian Economy, pp. 1–33.

Lashitew, A. A., Van Tulder, R., & Liasse, Y. (2019). Mobile phones for financial inclusion: What explains the diffusion of mobile money innovations? Research Policy, 48(5), 1201–1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.12.010

Liu, Y., Luan, L., Wu, W., Zhang, Z., & Hsu, Y. (2021). Can digital financial inclusion promote China’s economic growth? International Review of Financial Analysis, 78, 101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101889

Loke, Y. J., Chin, P. N., & Hamid, F. S. (2022). Financial literacy in Malaysia, 2015–2018. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies, 59(2), 171–197. https://doi.org/10.22452/MJES.vol59no2.1

Lusardi, A. (2008). Financial Literacy: An Essential Tool for Informed Consumer Choice? National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy: Do people know the ABCs of finance? Public Understanding of Science, 24(3), 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662514564516

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10(4), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474721100045X

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. American Economic Journal: Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.1.5

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 14(4), 332–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747215000232

Lyons, A. C., & Kass-Hanna, J. (2019). Financial inclusion, financial literacy and economically vulnerable populations in the Middle East and North Africa. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 2019, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1598370

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science, 342(6163), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238041

Mialou, A., Amidzic, G., & Massara, A. (2017). Assessing countries’ financial inclusion standing - A new composite index. Journal of Banking and Financial Economics, 2(8), 105–106.

Monticone, C. (2010). How much does wealth matter in the acquisition of financial literacy? Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01175.x

Morduch, J. (1999). The microfinance promise. Journal of Economic Literature, 37(4), 1569–1614. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.37.4.1569

Morgan, P. J., & Trinh, L. Q. (2019). Determinants and impacts of financial literacy in Cambodia and Viet Nam. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010019

Murendo, C., & Mutsonziwa, K. (2017). Financial literacy and savings decisions by adult financial consumers in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12318

Nam, Y., & Loibl, C. (2021). Financial capability and financial planning at the verge of retirement age. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(1), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09699-4

Neaime, S., & Gaysset, I. (2018). Financial inclusion and stability in MENA: Evidence from poverty and inequality. Finance Research Letters, 24, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.09.007

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2015). Improving Financial Literacy, Analysis of Issues and Policies. OECD Publishing.

Ozili, P. K. (2018). Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 18(4), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003

Park, C.-Y., & Mercado, R., Jr. (2018). Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality. The Singapore Economic Review, 63(1), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590818410059

Patwardhan, A., Singleton, K. & Schmitz, K. (2018) Financial inclusion in the digital age. Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion: 57–89.

Pradhan, R., Mallik, G., Bagchi, T. P., & Sharma, M. (2018). Information communications technology penetration and stock markets-growth nexus: From cross country panel evidence. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 24(4), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSTM.2018.093337

Pradhan, R., & Sahoo, P. P. (2021). Are there links between financial inclusion, mobile telephony, and economic growth? Evidence from Indian states. Applied Economics Letters, 28(4), 310–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2020.1752893

Rosell Foxá, J., & Viladomiu Canela, L. (2020). Indicadores estadísticos para la delimitación y caracterización de zonas rurales. Indice: Revista de Estadística y. Sociedad, 77, 29–31.

Sahay, M. R., Cihak, M., N’Diaye, P., Barajas, A., Mitra, S., Kyobe, A. J., Mooi, Y. N. & Yousefi, S. R. (2015). Financial Inclusion: Can It Meet Multiple Macroeconomic Goals? Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund.

Sahay, M. R., von Allmen, M. U. E., Lahreche, M. A., Khera, P., Ogawa, M. S., Bazarbash, M., & Beaton, M. K. (2020). The promise of fintech: Financial inclusion in the post COVID-19 era. Washinton, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund.

Santini, F. D., Ladeira, W. J., Mette, F. M., & Ponchio, M. C. (2019). The antecedents and consequences of financial literacy: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(6), 1462–1479. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-10-2018-0281

Santoso, A. B., Trinugroho, I., Nugroho, L. I., Saputro, N., & Purnama, M. Y. I. (2016). Determinants of financial literacy and financial inclusion disparity within a region: Evidence from Indonesia. Advanced Science Letters, 22(5–6), 1622–1624. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2016.6706

Schuetz, S., & Venkatesh, V. (2020). Blockchain, adoption, and financial inclusion in India: Research opportunities. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 101936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.04.009

Sethi, D., & Acharya, D. (2018). Financial inclusion and economic growth linkage: Some cross country evidence. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 10(3), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-11-2016-0073

Sinha, S., Pandey, K. R., & Madan, N. (2018). Fintech and the demand side challenge in financial inclusion. Enterprise Development & Microfinance, 29(1), 94–98.

Sun, T. (2018). Balancing innovation and risks in digital financial inclusion—experiences of ant financial services group. Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion, 2, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812282-2.00002-4

Valentine, G. P. & Khayum, M. (2005). Financial Literacy Skills of Students in Urban and Rural High Schools. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 47(1).

Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 449–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.006

World Bank. (2014). Global Financial Development Report 2014: Financial Inclusion; Washington, DC, USA: World Bank.

Young, A. (2013). Inequality, the urban–rural gap, and migration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1727–1785. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt025

Zhang, Q., & Posso, A. (2019). Thinking inside the box: A closer look at financial inclusion and household income. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(7), 1616–1631. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1380798

Zulkhibri, M. (2016). Financial inclusion, financial inclusion policy and Islamic finance. Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies, 9(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/17520843.2016.1173716

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G-L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G-L. and A.M–N.; writing—review and editing, M-J.G-L.and J-L. R-S.; visualization, M-J.G-L.and J-L. R-S.; supervision, R.G-L. and A.M–N.; methodology, J-L. R-S.; validation, M-J.G-L., J-L. R-S., A.M–N., and R.G-L.; formal analysis, J-L. R-S. and A.M–N.; resources, R.G-L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gallego-Losada, MJ., Montero-Navarro, A., Gallego-Losada, R. et al. Measuring financial divide in the rural environment. The potential role of the digital transformation of finance. Int Entrep Manag J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00992-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-024-00992-4