Abstract

Throughout history, expeditionists and explorers have discovered foreign countries and new worlds, markedly influencing the lives of succeeding generations. However, as multinational enterprises have come to drive globalisation, the existence of entrepreneurial individuals without the resources of large corporations is a relatively recent phenomenon. Although research on migrant entrepreneurs demonstrates the positive impact that foreign entrepreneurial activity can have on job creation and innovation, a clear perspective on entrepreneurs from developed economies venturing abroad is lacking. The study aggregates evidence from 33 articles to establish a unifying framework that describes the foreign entrepreneurial process originating in developed economies. The framework proposes categorising foreign entrepreneurial activity according to social and economic dimensions and introduces four archetypes of foreign entrepreneurs, helping us understand the dynamics of the institutional context and the motivations for venturing into foreign environments. Finally, the study discusses the implications for foreign entrepreneurs and considers future research avenues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Data from the United States and Germany suggests that foreign entrepreneurial activity accounts for as much as 20% of all venture creation (Center for American Entrepreneurship, 2017; Kollmann et al., 2020) and, therefore, plays an essential role in a country's entrepreneurial activities. For example, in Silicon Valley in the 1990s, approximately a quarter of the technology firms were co-founded by entrepreneurs with a migration background, contributing significantly to job growth, wealth creation and innovation power (Saxenian, 2000, 2002). The possible long-term effects of entrepreneurship initiated by migrants become evident when looking at the 500 most valuable American companies. Every fifth company was founded or co-founded by first- or second-generation immigrants (Center for American Entrepreneurship, 2017). Some of these entrepreneurs were migrants out of necessity, while some came from other developed economies to pursue an opportunity in the larger American market.

Much prior literature about foreign entrepreneurial activity emphasized ethnic entrepreneurship (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990; Basu, 2006; Waldinger et al., 1990; Zhou, 2004) or migrant entrepreneurship (Baycan-Levent & Nijkamp, 2009). Most of these entrepreneurs come from less developed countries, travelling to Europe and North America to pursue their dreams of a better life and a prosperous future (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2022). However, having difficulties entering local labour markets leaves them with no choice but to become entrepreneurially active out of necessity (Acs et al., 2008; Chrysostome, 2010).

Nevertheless, not all foreign entrepreneurs move from less developed to more developed economies. Instead, entrepreneurial movements occur in various contexts and directions (Elo, 2016; Elo et al., 2018). Scholarship on foreigners from developed economies venturing "against the tide" (e.g. Elo et al., 2019:96) has emerged, and several conspicuous start-ups founded by entrepreneurs who moved "between" developed economies (e.g. Carson & Carson, 2018; De Cock et al., 2021; March-Chordà et al., 2021) evolved (Appendix 1). These global entrepreneurs from developed countries exploit international opportunities in developed, emerging and developing nations.

Starting a business in a foreign institutional environment adds uncertainty to the venture. Entrepreneurs who take the step of venturing abroad are likely to be distinguished from those entrepreneurs in their home country. Some are "elite diasporans with developed skills and numerous alternatives for their career and livelihood" (Elo, 2016, p. 123). This specific type of entrepreneurial activity's antecedents, conditions and aims differ from the factors involved in venturing, for example, to developed countries out of necessity (Acs et al., 2008).

However, the systematic knowledge about the phenomenon is vague. Individual entrepreneurs from developed countries have not received much attention, especially not as much as the firm-level perspective of internationalizing new businesses (Dillon et al., 2020). Moreover, the multiplicity of terms within the research field of foreign venturing hampers the evolution of the academic discussion on entrepreneurs from developed economies venturing abroad and limits the theoretical exploration of the phenomenon. For example, Almor and Yeheskel (2013) called them sojourning entrepreneurs, Ngoma (2016) simply referred to foreign entrepreneurs, and Selmer et al. (2018) and Vance et al. (2016, 2017) coined the term expat-preneurs. Moreover, some studies have allocated the phenomenon to the ethnic realm (Lassalle et al., 2020; Shin, 2014; Thomas & Ong, 2015). Sometimes, the concepts and terms overlap, while at other times, they do not, leading scholars to debate the terms' applicability to real-world situations (Gruenhagen et al., 2020).

Thus, this study aims to answer the following research question: What drives foreign entrepreneurial activity from developed economies to other developed, emerging or developing economies and with what consequences? Employing a systematic and rigorous review of the existing literature suits the research goal of developing an omnibus perspective (Whetten, 1989) on the phenomenon. More specifically, we identified, analyzed and synthesized 33 studies providing evidence on entrepreneurs from developed economies venturing abroad.

The study provides one of the first general overviews of the foreign entrepreneurial process from developed countries to other developed, emerging or developing economies. This overview offers three significant contributions to the current literature. First, the study introduces a unifying framework for the foreign entrepreneurial process that includes the evidence from the 33 analyzed articles. Second, the article suggests exciting future research avenues that can contribute to closing the knowledge gap on the phenomenon. Hence, the academic discussion on the entrepreneurial movement from developed countries to other developed, emerging or developing economies will benefit from systematic access to international entrepreneurship research. Finally, the study proposes categorizing foreign entrepreneurial activity based on social and economic dimensions that measure the created impact. In sum, the article contributes to developing strategies to increase the impact that entrepreneurs can have on host countries. Furthermore, our proposed analytical framework is applicable independently of the different terms applied in prior research and offers necessary insights regarding foreign entrepreneurial activity.

Review methodology

We employed a three-phase systematic literature review process (planning, conducting and reporting) (Tranfield et al., 2003) to examine the current state of knowledge. In the planning phase, the authors screened the existing literature by conducting several search rounds to identify relevant keywords, terms and articles about entrepreneurs from developed countries venturing abroad. Details of the conducting phase are presented below, along with the reporting of the findings. The review incorporated recommendations for systematic literature reviews in business and management research (Fisch & Block, 2018) and aimed to provide utmost transparency about each step undertaken (Kraus et al., 2020; Kuckertz & Block, 2021). Therefore, we followed suggestions from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021).

Search term development

The developed search term was based on the context-intervention-mechanisms-outcomes (CIMO) framework (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). However, applying all four steps of CIMO would have narrowed down the search too much, not allowing us to answer the research question of what drives foreign entrepreneurial activity from developed economies to other developed, emerging or developing economies and with what consequences. Therefore, the search covered both the context and the interventions while purposefully neglecting the mechanisms and outcomes. The first part of the search string approached entrepreneurship as the context of the search. The second part represented internationalisation as an intervention affecting entrepreneurship. However, the search term could not display the direction of the intervention; that is, to originate from developed economies. Therefore, we used a broad spectrum of keywords to represent the international movement describing the intervention. Table 1 provides information on each search term. The final search string was as follows:

("entrepreneu*" OR "founder" OR "founder-manager" OR "startup" OR "start-up" OR "start up" OR "venture") AND ("born global" OR "born-global" OR "foreign*" OR "international" OR "transnational" OR "trans-national" OR "expat*" OR "sojourn*" OR "ethnic" OR "diaspora*" OR "*migrant")

Article selection

We used the scientific database Scopus for article identification, as Scopus covers a broad spectrum of academic literature and is one of the most comprehensive academic databases (Gusenbauer & Haddaway, 2020). The search string was adjusted to the database search requirements. The initial search included the fields title, abstract and keywords, resulting in 30,106 articles before we applied inclusion and exclusion criteria. In line with previous reviews of international entrepreneurship scholarship (Peiris et al., 2012), the initial search included many different research fields. Therefore, it is plausible that the search was not limited to business-related fields but was situated at a broad analytic level to gain cross-disciplinary insights and examine several perspectives on the topic (Tranfield et al., 2003). Although this procedure produces many initial results, it limits the risk of overlooking relevant articles. Next, we iteratively applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, narrowing down the results to the final number.

Inclusion criteria

First, we only considered peer-reviewed English-language articles published in scientific journals to guarantee the quality of the included articles (Kraus et al., 2020). We did not include book chapters, conference papers, monographs and doctoral theses. Second, the review included articles published between 2010 and 2022. Over a decade, institutional environments change significantly in developing and emerging countries (Robinson & Acemoglu, 2012); in fact, even a country’s developmental status may change. However, covering 12 years in the search was likely to reveal relevant articles for the review. Third, the search was limited to research fields that belong to the social sciences, excluding all articles from fields belonging to the natural sciences. Lastly, applying a quality cut-off for the journal ranks ensured that the articles came from journals contributing to scientific debates (Paul & Rosado-Serrano, 2019). Therefore, journals with an explicit focus on the research area of international entrepreneurship served as a quality reference. After scoping the journals, we decided to apply a quality cut-off equal to the Scopus CiteScore of 3.0. This procedure included one-third of the journals from the Business, Management, and Accounting research field (Scopus, 2022), limiting the review to articles that contribute to ongoing scientific conversations and ensuring the inclusion of the most influential target-field journals. The procedure resulted in an initial sample of 2,368 articles.

Exclusion criteria

Most of the identified 2,368 articles belonged to international business, entrepreneurship and international marketing research areas. This confirmed that the search string and inclusion criteria functioned properly, thus allowing us to identify an ample number of articles for review. We screened the identified articles by first reading the titles and abstracts and excluding irrelevant studies (Booth et al., 2021) by applying the exclusion criteria described below.

First, the object of analysis was entrepreneurs at the individual level. Therefore, articles investigating the firm level – for example, as in the case of the internationalisation of a new venture– were excluded. Second, only studies that clearly emphasised foreign entrepreneurs instead of local entrepreneurs fit the research goal. Third, we excluded all studies investigating entrepreneurs from non-developed economies. However, it was difficult to categorise countries accurately according to their development level, given that.

“there is no established convention for the designation of “developed” and “developing” countries or areas in the United Nations system. In common practice, Japan in Asia, Canada and the United States in northern America, Australia and New Zealand in Oceania, and Europe are considered “developed” regions.” (United Nations, 2003; see also Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2006)

This definition by the United Nations dates back to 2003. It shows that no clear indicators for such categorisation exist. Therefore, we decided to rely on two parameters instead of a single source. First, the Inequality-Adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) considers “very high human development nations” to have an IHDI equal to or higher than 0.8 (United Nations, 2020). Taking life expectancy, years of schooling and gross national income per capita into account, the IHDI is an adequate measurement of a country’s stage of development. Second, the high-income-nations list provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2022) was useful in classifying nations’ development (Karanikolos et al., 2016). Comparing IHDI and the list, most of the countries overlap. However, some highly developed IHDI countries are not part of the OECD’s list. Therefore, we introduced the United Nations Human Development Index (United Nations, 2020) value of over 0.85 as the third criterion and triangulated the list by excluding nations that did not fulfil at least two of the three criteria. Table 2 provides information on countries meeting the following criteria:

Screening the titles and abstracts, the lead author sorted the articles into two groups according to their relevance or irrelevance to the review. Articles deemed uncertain after reading the title and abstract were added to the third group of articles that require further analysis. Next, a research assistant used a sub-sample of 200 randomly chosen abstracts to triangulate the applicability of the research team’s exclusion criteria. Most of the articles were classified identically after reading the title and abstract. However, the articles whose classification was ambiguous were added to the group considered to require further analysis. The authors read all articles that were identified to be included or classified to be ambiguous entirely to not exclude any relevant articles. Therefore, the exclusion criteria were suitable for initially sorting out the abstracts. The final decision between inclusion and exclusion in the review was made only after thoroughly reading the articles that were ambiguous or identified to be relevant after the abstract screening. Thus, although some articles fulfilled the initial criterion of dealing with foreigners venturing abroad, we excluded the articles that did not add value to the review – for example, articles that investigated entrepreneurial activities in the past centuries (e.g. Lopes et al., 2018; Sifneos, 2010). However, each exclusion from the review was discussed extensively to avoid overlooking relevant articles.

This procedure resulted in the final sample of 33 articles. Figure 1 summarises the search and selection procedure following the recommended PRISMA-process (Page et al., 2021; Stovold et al., 2014); the amplified PRISMA checklist is in Appendix 2.

Analysis

Booth et al. (2021, p. 73) recommended using analysis software for qualitative literature synthesis. We used MAXQDA 2020 (version 20.0.1b) to analyse and code the articles. Furthermore, we employed a data extraction sheet (Booth et al., 2021) to collect relevant information. Table 3 provides key information from the data extraction sheet and the reviewed articles, including the methodologies, research question, entrepreneurs’ countries of origin and residence, and a summary of each reviewed article. When reading, analysing and coding the identified articles, the research team considered the following research question: What drives foreign entrepreneurial activity from developed economies to other developed, emerging or developing economies and with what consequences?

Results

Descriptive results

We used the bibliographic data from the selected articles (n = 33) to run a bibliographic coupling network analysis using the VOSviewer software (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010). The VOSviewer software applies an algorithm that visualizes similarities on a distance-based approach (Van Eck & Waltman, 2014) and has proven a reliable tool for bibliometric coupling analysis (Cobo et al., 2011). The algorithm places items according to their relatedness. Closely related items are nearer to one another; an increasing distance implies weaker relations between the nodes (Waltman et al., 2010). The strongest related items within the network are placed in the centre, while weaker connections are somewhat at the edge.

Figure 2 displays the journal map based on bibliographic couplings of the 33 articles' sources (Appendix 3 contains bibliographic summary statistics; Appendix 4 shows the document map including the citation count of the studies). The selected articles were published in various fields and journals, indicating a cross-sectoral audience. Each circle represents one of the journals; the size indicates the number of published articles (increasing size with an increasing number of articles). The colour scheme allocates the journals to a cluster (see Table 4) following the VOSviewer integrated clustering method based on association strengths' relatedness (Waltman et al., 2010) with a resolution of 1.0. Table 4 provides the journal source, their allocated cluster, and the number of articles. Most journals were business related and focused on entrepreneurship.

The Journal of International Entrepreneurship (red), International Business Review (green), and also the Journal of Enterprising Communities (blue) built three major clusters and published most about foreign entrepreneurs from developed countries. The analysis further shows that journals with an international (entrepreneurship & business) focus published most content on foreign entrepreneurship originating from developed countries. One article published in Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice (Hudnut & DeTienne, 2010; see Cluster 5) has no linkages with the other articles and, therefore, is distanced from the connected journal map.

International entrepreneurship research entails intersections with various research disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, international business and economics, to name a few (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005). Furthermore, most studies describe the phenomenon of foreigners venturing abroad and provide little theoretical explanation for the determinants, antecedents, and consequences typically discussed in superordinate management journals. The theories developed in the Western context do not necessarily apply to emerging and developing countries (Wright et al., 2005). Therefore, familiarising oneself with the phenomenon and then applying, testing and developing theories is plausible.

However, the small number of quantitative studies and the lack of theoretical explanatory power indicate that access to entrepreneurs from developed countries venturing abroad is limited. Not reaching a critical mass of entrepreneurs operating in comparable environments leads to a lack of quantifiable results, which, in turn, results in the inability to test theories. Consequently, the theoretical lens is not sharpened, scholars do not apply the same theories to explain the phenomenon more deeply, and there are no ongoing discussions on an agreed set of issues or theories within or across journals.

Figure 3 displays the methodological designs of the reviewed articles. Many authors have applied qualitative research designs (24), drawing mainly on case studies. Accordingly, interviews were the most common primary data source. At the same time, only a minority of the studies collected and investigated quantitative data (4) (Connelly, 2010; Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė et al., 2021; Selmer et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2011), and few conceptual studies (4) (Chrysostome, 2010; Ensign & Robinson, 2011; Nkongolo-Bakenda & Chrysostome, 2013; Tucker & Croom, 2021) contributed to developing the understanding of the field and its boundaries.

Most studies have focused on entrepreneurial activities between developed countries (15), followed by a developed-to-less-developed perspective (10). By contrast, only one study investigated developed-to-least-developed countries. The most frequent countries of residency (CoR) were China and the US. However, it was surprising that little to no research focused on emerging economies, such as India (none), or fast-developing countries in Africa (only 1 study). One could imagine that these environments offer many possibilities to entrepreneurial foreigners from developed countries in terms of social development (Rivera-Santos et al., 2015; Tucker & Croom, 2021) and economic opportunities, especially within Africa (Heidenreich et al., 2015). Therefore, the minimal emphasis on Africa, the demographically fastest-growing continent with great economic potential, was unexpected. Table 5 shows the movements from the entrepreneurs’ country of origin (CoO) to their CoR.

Towards a unifying framework

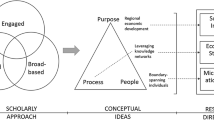

The guiding research question of what drives foreign entrepreneurial activity from developed economies and with what consequences was complex and multi-faceted. Unsurprisingly, the relevant articles were heterogeneous. Based on the reviewed articles, Fig. 4 synthesises the evidence into one overarching framework that furthers our understanding of the phenomenon. The following paragraphs will discuss the elements of the framework and how they affect the foreign entrepreneurial journey.

Starting with contextual effects, the framework shows that external and internal factors, namely the entrepreneur’s context and the country’s context, play a significant role (e.g. Chrysostome, 2010; Lassalle & Scott, 2018) throughout the entrepreneurial process. Contextual factors matter in entrepreneurship (Welter, 2011). Therefore, the context impacts how entrepreneurs discover opportunities, how they embed themselves in a foreign society and what the impacts of their endeavours are. Next, the framework emphasises the antecedent circumstances and motivations of foreign entrepreneurs (e.g. Carson & Carson, 2018; Chandra et al., 2015; Knight, 2015) that trigger the entrepreneurial process abroad and explains how these factors translate into embeddedness in the host country (e.g. Lassalle & McElwee, 2016; Storti, 2014). Finally, the framework analyses how entrepreneurs impact host countries (e.g. Goxe et al., 2022; McHenry & Welch, 2018).

The framework was constructed after the first round of analysis and helped arrange the articles into an overarching structure. The framework’s elements were underpinned by the findings from the analysis of the articles. Therefore, we went back and forth between the literature and the framework.

Influential factors

It is well known that entrepreneurship is strongly shaped and influenced by the context in which it is practised (Welter, 2011). Therefore, adapting to external circumstances, particularly to the spatial context, cultural context and institutional framework, is critical for foreign entrepreneurs (e.g. Elo, 2016). Furthermore, foreign entrepreneurs’ personal circumstances impact the entrepreneurial journey abroad (e.g. McHenry & Welch, 2018). Our framework focuses on two overarching contextual dimensions. First, it addresses entrepreneurs’ personal dimension. Drawing on Whetten’s (1989) work, the personal dimension, or the who dimension, is important. Therefore, the entrepreneurs’ family status, prior experiences, and networks and skills matter. Second, the country context, or the where dimension, addresses various aspects of the host country, such as culture, institutional framework, and market opportunities (Welter, 2011; Whetten, 1989).

Personal context

Scholars have shown little consistency in applying theoretical frameworks to describe the personal contexts of foreign entrepreneurs. For example, Drori et al. (2009) and Goxe et al. (2022) drew on Bourdieu (1990) work on the different forms of personal capital and cultural fields. When an entrepreneur operates in a cross-cultural setting, his fields should adapt to the new “global economic field” (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 229). Regardless of the underlying theoretical lens, integration in the host-country context facilitates or complicates entrepreneurial work depending on entrepreneurs’ skills and resources, affecting their overall entrepreneurial activities on many levels.

Entrepreneurs’ resources, such as financial capital, managerial skills, network ties (Chrysostome, 2010) and prior experiences abroad, influence their capacity to recognise opportunities (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018), the partners with whom the entrepreneurs interact (Ngoma, 2016) and how they embed themselves within the host country (Gurău et al., 2020). Furthermore, the personal characteristics involved in adapting to new environments and expanding one’s resources, such as having a growth-oriented mindset, increase the likelihood of succeeding in the venture. By adopting a “dual resource system,” entrepreneurs first draw on their skills and resources before actively seeking to increase their resource endowments throughout the CoR society (Gurău et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the entrepreneurs’ personal context affects their embeddedness in various ways. For example, having local family ties eases movement within local institutional environments (McHenry & Welch, 2018). Loose contacts with host country nationals and difficulties accessing host country institutions lead to foreign entrepreneurs operating in co-ethnic niches (Lassalle & Scott, 2018). Establishing networks with other foreign entrepreneurs is helpful and easier to accomplish than attaining access to locals (Carson & Carson, 2018). Such networks help balance the lack of knowledge and difficulties in interacting with local institutions (Lassalle & McElwee, 2016). However, to achieve greater impact, entering local or global mainstream markets is essential (Ensign & Robinson, 2011; Lassalle et al., 2020).

Moreover, the personal context is not limited to entrepreneurs’ resources; rather, it affects various dimensions of their lives and the whole entrepreneurial journey. For example, the desire to live in a particular place is one motivation that drives some entrepreneurs from developed countries to venture abroad (e.g. Carson & Carson, 2018; Eimermann & Kordel, 2018). Therefore, personal factors can initiate entrepreneurial activity in a foreign country (e.g. McHenry & Welch, 2018; Selmer et al., 2018) or restrain an entrepreneur from being fully embedded within a foreign context as “mixed marriages and generational status influence the willingness to migrate to a new location” (Elo et al., 2019, p. 99).

Country context

The country context influences the entrepreneurial journey in several ways (Welter, 2011). The institutional environment affects entrepreneurs and the founding of their companies (North, 1990). Entrepreneurs who venture into foreign CoRs operate in spatial dimensions different from those of their CoOs. Institutional support and familiarity with the institutional environment are limited (Lassalle & McElwee, 2016), while institutional voids lead to restrictions and denied access, whether due to cultural distance or limited market knowledge (Marshall, 2011) – these issues are known as liabilities of foreignness (Hymer, 1976; Zaheer, 1995).

Although coming from developed countries and, on average, enjoying good education (e.g. Almor & Yeheskel, 2013; Carson & Carson, 2018; Goxe et al., 2022; Gurău et al., 2020; Selmer et al., 2018; Thomas & Ong, 2015), foreign entrepreneurs face challenges related to the local institutional settings of their CoRs. Therefore, it makes little difference whether they operate in another developed country (e.g. Eimermann & Kordel, 2018; Thomas & Ong, 2015) or in an emerging market (e.g. Elo, 2016) where institutional voids are expected (Wright et al., 2005). When venturing abroad, the starting point is to understand the emotions of local people (Elo, 2016). The entrepreneurs' limited knowledge about the host country's institutional environment increases the risk of failing the business (Heidenreich et al., 2015)..

However, the uncertainty of the environment encourages some entrepreneurs (Elo et al., 2019) to venture abroad and strengthens the co-ethnic networks of those who dare to do so (Shin, 2014; Yang et al., 2011). Thus, the host country’s institutional environment affects all steps along the entrepreneurial journey, starting from opportunity creation and entrepreneur embeddedness, and determines the social and economic impact that an entrepreneur can create.

Motivation

Knight (2015) underscored the complexity of founding a startup and suggested that the clear difference between necessity-driven and opportunity-driven (Block & Wagner, 2010) motives may sometimes be misleading. Nevertheless, the literature often associates migrant entrepreneurs moving from less-developed to more-developed countries with necessity-driven entrepreneurship (Chrysostome, 2010), compared to entrepreneurs from developed countries, who are said to act based on opportunity (Acs et al., 2008).

However, some entrepreneurs from developed countries venturing abroad do so out of necessity as well. For example, McHenry and Welch (2018, p. 5) found that the need to remain in the host country is a sufficient motivation for setting up a company. Unsurprisingly, the need to stay in a specific place depends on social connections, such as family ties in the CoR, which influence entrepreneurial decisions (Elo et al., 2019, p. 101). Indeed, foreigners’ “personal circumstances and social relationships often support the [founding] decision” (Selmer et al., 2018, p. 141). Moreover, entry barriers to the local labour market arise independently of individuals’ education (Knight, 2015) and apply to foreigners from developed countries as well. Challenges such as language barriers (Thomas & Ong, 2015) paired with differing salary expectations (McHenry & Welch, 2018) or job dissatisfaction issues (Storti, 2014) drive foreigners towards entrepreneurial activity. Therefore, although the particular motive for venturing abroad differs among individuals, for some entrepreneurs, the motivation for founding a business has to do with satisfying the need to stay in the CoR.

The decision to pursue a particular lifestyle is somewhere between chasing an opportunity and acting entrepreneurially out of necessity (Eimermann & Kordel, 2018; Carson & Carson, 2018). The question arises regarding which end of the continuum these entrepreneurs belong to. On the one hand, being unable to live a desired way of life in the CoO creates the pressure to move abroad. On the other hand, such entrepreneurs can identify and pursue opportunities allowing this kind of a move. Carson and Carson (2018, p. 236) claimed that “lifestyle factors and the search for a better and more balanced quality of life” drive foreign entrepreneurship. Therefore, venturing abroad is an opportunity for those who can afford it. The risks for foreigners from developed countries are certainly lower than those for individuals from less-developed countries, who often have few opportunities after migrating to a more-developed economy (Chrysostome, 2010). The motive of craving for a new start due to being dissatisfied with life in the CoO (e.g. the case of the “fallen Icaruses” in Goxe et al., 2022) seems closer to pursuing opportunities than being a last resort.

Most of the reviewed articles described opportunities to be a significant driver for foreigners from developed countries venturing abroad. However, entrepreneurs do not always discover opportunities in advance. There are two kinds of entrepreneurs: those who already know the opportunities available in a CoR and those who actively seek opportunities abroad (Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė et al., 2021). When identifying opportunities, a new environment and society surround foreigners staying in CoRs. Embeddedness in networks affects opportunity discovery and enactment (Engelen, 2001). Like ethnic entrepreneurs (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990), many foreign entrepreneurs first move within co-ethnic communities (e.g. Lassalle & McElwee, 2016; Yang et al., 2011). As a result, they seize co-ethnic opportunities that do not exist in their CoOs (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018). Such opportunities target co-ethnics on-site or leverage products and processes from entrepreneurs’ CoOs (Storti, 2014). Therefore, regarding the pursuit of ethnic opportunities, foreign entrepreneurs from developed countries show similar motivations to those encountered in the migrant entrepreneurship literature (e.g. Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990; Kloosterman, 2010).

However, most studies have emphasised market opportunities (e.g. Heidenreich et al., 2015) and location-specific aspects as active drivers of foreign venturing. Favourable institutional conditions attract entrepreneurs (e.g. Elo et al., 2019; March-Chordà et al., 2021). For example, European entrepreneurs looking to start high-tech startups seek opportunities in foreign markets that offer attractive entrepreneurial ecosystems – for example, as can be found in Silicon Valley (March-Chordà et al., 2021). Therefore, they leverage foreign markets and geographies to obtain a competitive advantage (De Cock et al., 2021) and purposefully draw on resources suitable for exploiting foreign market opportunities (Almor & Yeheskel, 2013; March-Chordà et al., 2021).

Moreover, institutional voids create opportunities for those eager to take on the challenge of working in an institutionally unstable environment (Elo et al., 2019). Contrary to the logic that a weak institutional environment harms entrepreneurship (Robinson & Acemoglu, 2012; Wright et al., 2005), institutional voids can also be beneficial (Ensign & Robinson, 2011). Unstable and challenging environmental factors create unique opportunities for those who dare to found a startup in these environments (e.g. Heidenreich et al., 2015). Therefore, such institutional environments allow entrepreneurs to leverage skills, networks and resources to obtain an advantage in pursuing opportunities (Abd Hamid & Everett, 2021; McHenry & Welch, 2018).

In sum, the motivational drivers of foreign entrepreneurs originating from developed countries are external factors that depend on the country context (e.g. Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė et al., 2021) paired with internal aspects related to entrepreneurs’ personal contexts. However, opportunity-driven pull factors outweigh push factors, which primarily stem from the desire or need to stay in the CoR. Nevertheless, independently of the motivational drivers, entrepreneurial opportunities influence foreign entrepreneurs’ embeddedness in CoRs (e.g. Hudnut & DeTienne, 2010).

Embeddedness

Studies of migrant entrepreneurs in advanced economies show that opportunity structures and the embeddedness of foreign entrepreneurs are closely related factors (Kloosterman & Rath, 2010; Waldinger et al., 1990). Considering the entrepreneur as an agent and the environment as the social context, ergo the structures the entrepreneurs are moving in (Giddens, 1979), embeddedness abroad depends on two factors. First, an entrepreneurs’ inner attitudes determine how they integrate into CoRs – that is, with whom they associate and how they understand the new local environment. Second, the social structures and mechanisms related to the entrepreneurial process (Jack & Anderson, 2002) ease or complicate the integration process and impact the embeddedness of entrepreneurs.

Embeddedness is dynamic and develops “progressively, through multiple and sequential professional experiences in the host country” (Gurău et al., 2020, p. 10). For example, prior stays and expatriate assignments (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018; Selmer et al., 2018) in the CoR provide entrepreneurs with networks and cultural experiences. Our framework identifies four levels of embeddedness in a CoR. The first level involves the entrepreneurs’ community (Goxe et al., 2022), a familiar cultural space that offers access to networks and resources. It serves as the first step in embedding oneself within a CoR (Lassalle et al., 2020). The second level refers to the co-ethnic society within the CoR, which functions as an enabler and a catalyst for foreign venturing (e.g. Abd Hamid & Everett, 2021; Eimermann & Kordel, 2018; Shin, 2014). The third level addresses the host-country society. Entrepreneurs have to embed themselves into the host-country society to overcome institutional challenges (McHenry & Welch, 2018) and enter mainstream markets (Ensign & Robinson, 2011). Finally, only after entering mainstream markets, a global expansion seems possible (De Cock et al., 2021).

Overall, entrepreneurs’ motivations for entering foreign societies matter. Entrepreneurs’ reasons for staying in particular countries influence their degree of embeddedness. As outlined before, some foreigners become entrepreneurs out of the necessity to stay in a CoR. Conversely, those who pursue opportunities have no intention of staying in a CoR permanently but establish ventures to exploit opportunities (Almor & Yeheskel, 2013; McHenry & Welch, 2018).

Entrepreneurs can move across the levels to become more deeply embedded in a CoR (Lassalle et al., 2020) – for example, by grasping local business habits (Ngoma, 2016). At first, many foreign entrepreneurs rely on their co-national communities for support and easier access to resources (Ensign & Robinson, 2011; Thomas & Ong, 2015). Then, entrepreneurs start developing co-ethnic networks and strengthening social ties (Knight, 2015) with host-country nationals to eventually enter mainstream markets (Ensign & Robinson, 2011).

However, some entrepreneurs intentionally adhere to chosen communities (e.g. Goxe et al., 2022) – for instance, those from their CoOs (e.g. Abd Hamid & Everett, 2021) – and do not embed themselves locally. Therefore, the movement from the self-centred to the global level does not apply to all foreigners. Carson and Carson (2018) found that such so-called “international enclaves” purposefully exclude themselves from the local society and move somewhere between their co-national communities and co-ethnic societies, disregarding local interests. Surprisingly, not all co-ethnic entrepreneurs trust their communities, even though relying on networks and resources is a common practice (Lassalle & McElwee, 2016).

One clear difference between migrant entrepreneurs going to developed countries and entrepreneurs coming from developed countries is the desire to immigrate and settle in the host country in the long term. The necessity-driven entrepreneurs described above desire to stay in the host country temporarily but do not have permanent plans to do so (Elo et al., 2019). Similarly, lifestyle entrepreneurs are susceptible to lifestyle changes and may pursue other lifestyles in other countries in the future. Therefore, the urge to assimilate into a CoR and to establish firm ties with the local society is limited (Eimermann & Kordel, 2018). For foreigners from developed countries, it seems uncertain whether it is worth taking the arduous path of integrating into a foreign environment when the stay duration in the CoR is limited.

There is no doubt that deep local roots are a prerequisite for fully leveraging local resources and building a company capable of operating in local mainstream markets and potentially achieving global reach. A strong bond with the host country strengthens entrepreneurial capacity and should, therefore, be envisaged from early on (Selmer et al., 2018). Moreover, companies targeting local customers (Tucker & Croom, 2021) – for instance, through social entrepreneurship – need to fully integrate into the CoR. Otherwise, fully understanding the foreign market is difficult (Hudnut & DeTienne, 2010). In fact, foreignness can become a strength, as it can help an entrepreneur leverage the foreign community’s resources and networks in the CoR and the CoO. Logically, the social and economic impact of the entrepreneur on the host country also depends on the degree of embeddedness. The larger the target market, the greater the economic and social impact that an entrepreneur can create.

Impact

Entrepreneurship is an essential pillar of the economy that creates economic and social impacts (Schumpeter & Backhaus, 2003). However, the type of business and its embeddedness in a local society can make all the difference between a niche business and a company with tremendous growth potential (Saxenian, 2007). Moreover, embeddedness varies depending on entrepreneurs’ intentions of becoming locally embedded (e.g. Goxe et al., 2022), the chosen level of embeddedness (Lassalle et al., 2020) and the ability to become embedded (e.g. Abd Hamid & Everett, 2021; Lassalle & McElwee, 2016). Therefore, our framework categorises entrepreneurs venturing abroad into four archetypes along a continuum from low to high social and economic impacts (see Fig. 4). These four archetypes of international entrepreneurs are xenophile social entrepreneur, glocalised lifestyle entrepreneur, glocalised opportunity seeker and international opportunity seeker.

The social impact of foreign entrepreneurship depends on their integration and embeddedness in local structures. It seems improbable that an entrepreneur with little to no contact with local customers or employees could significantly impact society. Nevertheless, such an entrepreneur can generate a robust economic impact. In particular, entrepreneurs who engage with limited communities or adopt international business models can create sustainably profitable businesses that indirectly benefit host countries by bringing in scarce resources (Almor & Yeheskel, 2013). Naturally, the associated foreign entrepreneurial investments and the resulting impacts are low compared to those of multinational enterprises at least initially (Almor & Yeheskel, 2013). However, the future potential of some of these ventures is promising (De Cock et al., 2021). Looking at the foreign entrepreneurial impact in advanced economies (Kloosterman & Rath, 2001, 2010), specifically in the case of Silicon Valley (Saxenian, 2007), the belief in foreign entrepreneurship and its potential economic dimensions is well-grounded. Therefore, robust economic impact can later on promote social impact.

Xenophile social entrepreneurs

Tucker and Croom (2021) examined the phenomenon of venturing for foreigners, specifically the xenophile aspect of entrepreneurship. Foreigners venturing abroad for social reasons with a low economic impact fit this idea. One could also argue that social entrepreneurship addressing social problems are included in this archetype. However, engaging in social entrepreneurship in a foreign CoR is a phenomenon that emphasises operating a social business for other people coming from another CoO. Therefore, xenophile entrepreneurs from developed countries are less motivated by pursuing opportunities that increase their economic gains and more motivated by social impacts for the underprivileged (Marshall, 2011).

Glocalised lifestyle entrepreneur

In contrast to entrepreneurs who act based on social motivation, glocalised lifestyle entrepreneurs are not particularly successful in economic terms, nor do they contribute to improving social structures (Carson & Carson, 2018). The scope of their entrepreneurial activity hardly reaches beyond their extended community (Eimermann & Kordel, 2018). For this archetype, entrepreneurship is arguably more of a means to an end, with no grand intentions. Instead of becoming entrepreneurs out of necessity, the persons belonging to this archetype pursue entrepreneurship to lead their preferred lifestyles in the host country. (McHenry & Welch, 2018).

Glocalised opportunity seeker

Glocalised opportunity seekers are firmly anchored in their CoRs and purposefully realise entrepreneurial opportunities. These entrepreneurs operate beyond their communities and co-ethnic networks (e.g. Dillon et al., 2020; Goxe et al., 2022; Selmer et al., 2018). Many such foreign entrepreneurs have work experience as expatriates (e.g. Connelly, 2010; McHenry & Welch, 2018; Selmer et al., 2018) and have professional social networks in their CoOs and CoRs (Ngoma, 2016). Therefore, they combine the strength of using the resources of both the CoO and the CoR to mitigate the challenges associated with venturing abroad (e.g. Gurău et al., 2020). However, these entrepreneurs do not achieve a deep enough local anchoring to run established large companies with unique international selling points or to seize the next significant opportunity (e.g. Almor & Yeheskel, 2013). Nevertheless, they are economically prosperous and make a non-negligible contribution to economic development.

International opportunity seeker

International opportunity seekers proactively go to host countries to take advantage of existing structures and to make the best possible use of entrepreneurial opportunities (De Cock et al., 2021; March-Chordà et al., 2021). These entrepreneurs combine resources from their home countries with those from the host country and orient themselves globally from the very beginning of the venture. Therefore, their local embeddedness is deep, and their economic contributions have enormous potential (Saxenian et al., 2002).

Table 6 further illustrates the different archetypes of foreign entrepreneurs from developed countries by providing vignettes derived from the article data.

Discussion

Our study explored, at the individual level, what drives foreign entrepreneurial activity from developed economies to other developed, emerging or developing economies and with what consequences. After systematically reviewing the literature, we introduced a unifying framework for the foreign entrepreneurial journey, which includes contextual influences, motivations for venturing abroad, embeddedness in CoRs, and the resulting social and economic impacts.

Motivation, embeddedness and impact condition one another

Throughout the entrepreneurial journey, the institutional environment in a CoR influences entrepreneurial activities by facilitating or restricting them. Therefore, the country context is highly significant when investigating foreign entrepreneurial activities (Welter, 2011; Wright et al., 2005). However, the entrepreneurial journey is complex and can only be properly understood by also considering the entrepreneur’s personal context. Prior studies have indicated that migrant entrepreneurs who emigrate to developed countries mainly venture out of necessity (Block & Wagner, 2010; Chrysostome, 2010) – for example, due to the inability to enter the local labour market (Zhou, 2004). Foreign entrepreneurs from developed countries, in turn, are much more driven by their personal abilities and desires (e.g. Almor & Yeheskel, 2013; Goxe et al., 2022); therefore, they can be described as “opportunity immigrant entrepreneurs” rather than “necessity immigrant entrepreneurs” (Chrysostome, 2010, p. 139). As a result, such entrepreneurs usually do not intend to stay permanently in a CoR. Instead, they want to pursue specific opportunities or stay for personal reasons, often based on familiar motivations (McHenry & Welch, 2018). Thus, the personal context determines how such entrepreneurs embed themselves in CoRs and, eventually, what impacts they create.

At first, personal motivation seems to be the starting point of the entrepreneurial journey, determining the efforts undertaken for deeper embeddedness in a CoR, which further influences the impact that an entrepreneur can have. However, the relationship between motivation, embeddedness and impact is linear and direct. In other words, it is not simply motivation and embeddedness that condition the impacts that entrepreneurs can produce; instead, all three aspects determine and condition one another. Figure 5 outlines the interrelations of the three aspects.

Entrepreneurs’ desired impact creation requires a certain depth of embeddedness in a CoR (Ensign & Robinson, 2011). Furthermore, a clearly stated impact goal affects the entrepreneurial motivation – for instance, when venturing for social reasons (Marshall, 2011; Tucker & Croom, 2021). Moreover, motivation and embeddedness partly account for the differences between entrepreneurs from developed and developing economies. For example, when the intention to stay in a CoR is time-bound, the motivation to make efforts to become locally embedded likely is lower (Elo et al., 2019), which prevents entrepreneurs from reaching their full impact potential (Goxe et al., 2022).

Furthermore, embeddedness affects entrepreneurial motivation. For instance, deeply embedded foreigners with staying motives can choose the entrepreneurial path to remain in a CoR (McHenry & Welch, 2018). There is a connection between the impact and the motivation. The motivation to achieve a desired impact leads to perseverance in achieving the set target. Therefore, motivation indirectly affects the efforts entrepreneurs are willing to make to reach their impact goals. For example, it is possible increase one’s local embeddedness to increase one’s resources (Knight, 2015; Lassalle et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding the threefold relation of motivation, embeddedness and impact is essential for comprehending foreign entrepreneurs.

Categorising foreign entrepreneurs according to their impact

As mentioned initially, there are many categories and terms of foreigners venturing abroad: sojourners (Almor & Yeheskel, 2013), expat-preneurs (Selmer et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2016) and lifestyle entrepreneurs (Carson & Carson, 2018), to name a few. Further, more compelling research fields have evolved, such as diaspora entrepreneurship (Elo, 2016), transnational entrepreneurship (Drori et al., 2009), ethnic entrepreneurship (Aldrich & Waldinger, 1990) and migrant entrepreneurship (Baycan-Levent & Nijkamp, 2009). However, we do not sort the entrepreneurs according to their ethnicity or call them migrants because their intentions to stay in a CoR are unclear. Furthermore, some operate transnational businesses (e.g. Heidenreich et al., 2015; Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018), while others work at the local level (e.g. Carson & Carson, 2018). In addition, their entrepreneurial motivations and intentions differ, as some entrepreneurs start as expatriates in a CoR; others, however, actively seek opportunities in emerging economies and act as sojourners or move to markets where they see the highest potential (Almor & Yeheskel, 2013; Chrysostome, 2010; Gurău et al., 2020).

Therefore, coming back to the “South to North” analogy of entrepreneurs travelling to more-developed economies (Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė et al., 2021), entrepreneurs from developed economies are globally oriented entrepreneurs who seek to exploit international opportunities where they encounter them. Arguably, they are “elite diasporans with developed skills and numerous alternatives for their career and livelihood” (Elo, 2016, p. 123). Although their entrepreneurial motivations and personal contexts differ, one might argue that such foreign entrepreneurs from developed countries, on average, also operate within the institutional arena they are familiar with, for example, they engage with co-ethnics and the expat community (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018). They actively extend their social capital by mobilising networks and resources when needed (Goxe et al., 2022; Ngoma, 2016). Thus, their resources enable them to use the dynamics of embeddedness to their advantage, differently from necessity-driven immigrant entrepreneurs (Chrysostome, 2010).

Nonetheless, foreigners from developed countries venturing abroad practice entrepreneurship and, thus, benefit economic growth and overall prosperity of the host country (Robinson & Acemoglu, 2012). Furthermore, “brain circulation” (Saxenian, 2007) significantly drives innovation, technology transfer and economic development. Therefore, the introduced framework has proposed categorising entrepreneurs according to their impact on CoRs by looking at social and economic dimensions. Furthermore, clustering entrepreneurs according to their impact improves our shared understanding of the motivations and outcomes of foreign entrepreneurship.

Policymakers benefit from furthering foreign entrepreneurship

Brain circulation positively impacts the development of innovation and entrepreneurial landscapes (Filatotchev et al., 2011; Saxenian, 2007). Venturing abroad can be associated with positively contributing to a host country, regardless of whether it is a developed or less-developed economy. Moreover, the experience and knowledge acquired in a CoR likely benefit the CoO at a particular stage – for example, when entrepreneurs return to their CoOs (Gruenhagen et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2008). As a result of venturing abroad, entrepreneurs bring back the human and social capital and the networks (Light et al., 2017) they acquired or developed in the CoRs. Drori et al. (2009, p. 1006) called them “scientists and engineers returning to their home countries to start up a new venture.” Looking at the characteristics of international opportunity seekers, it is likely that such entrepreneurial individuals contribute to both their CoOs and CoRs. Therefore, governments in CoRs and CoOs should support foreign entrepreneurship to maximise its social and economic benefits.

Implications for foreign entrepreneurs

Founding and operating a company is a demanding and long-term endeavour, even more so when venturing into a foreign country with unfamiliar institutional dimensions (Welter, 2011). Entrepreneurs’ personal contexts and life situations impact the whole entrepreneurial journey, and entrepreneurs have to act upon the identified opportunities deliberately. Therefore, entrepreneurs should be aware of the opportunities available to their businesses. For example, if the goal is to pursue a desired lifestyle (Carson & Carson, 2018), the company is more of a means to an end.

However, if the aim is to achieve a social goal, such as minimising the social grievances of the host population (Tucker & Croom, 2021), close cooperation with local institutions is necessary to either use them or change them for the better (Bruton et al., 2010). For example, international opportunity seekers bring their globally acquired resources and thus seize opportunities in the best possible way; glocalised lifestyle entrepreneurs, however, prioritise their desired ways of living. Therefore, to minimise uncertainty, entrepreneurs must define their goals for venturing abroad early on and be clear regarding the motivations and consequences.

Our study has shown that the degree of embeddedness within local society affects the economic and social impact that an entrepreneur eventually creates. Thus, vision-driven entrepreneurs aiming to enter mainstream markets must increase their social and cultural capital (Bourdieu, 2005; Goxe et al., 2022) to avoid being limited to niche markets (Ensign & Robinson, 2011). Active participation in and interaction with the CoR society is essential (Lassalle & Scott, 2018). Moreover, entrepreneurs can turn their foreignness into an advantage by drawing on a dual habitus (Goxe et al., 2022; Gurău et al., 2020) to overcome institutional voids (Drori et al., 2009).

Limitations and future research agenda

Some limitations of our study point to interesting opportunities for future research. Furthermore, reviewing the literature systematically helps identify research gaps that need to be bridged in the near future.

First, the review has provided an overarching look at entrepreneurs from developed countries. However, it was beyond our scope to analyse each component of the introduced framework in significant detail. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to investigate, for example, how the dynamics of embeddedness unfold for foreign entrepreneurs from developed countries compared to foreign entrepreneurs from less-developed countries venturing abroad. Furthermore, the study did not include geographical comparisons. The framework is general but lacks a focus on country-specific aspects, such as cultural distance or country-specific characteristics. Thus, investigating foreign entrepreneurship in regional areas and identifying area-specific attributes would open up future research avenues that would, in turn, help us understand the phenomenon of foreign entrepreneurship better while deriving more specific practical implications.

Second, theoretical saturation is far from being reached, and the theoretical lens needs further sharpening. Very few articles included in our review draw on a theoretical framework. As the articles adopt different overarching definitions of foreign entrepreneurship, such as ethnic entrepreneurship (e.g. Yang et al., 2011), no unifying principle is apparent. Therefore, the field would benefit from theoretical explanations based on the introduced framework to understand what drives foreign entrepreneurship and with what consequences. Explanations of the motivations and consequences shed light on how foreign entrepreneurial activity could be steered towards more significant social and economic impacts.

Third, foreign entrepreneurship offers promising future research avenues that could provide a better overall understanding of foreigners from developed countries venturing abroad. Expatriates operate multinational companies globally. Therefore, it is likely that the tendency of entrepreneurs from developed countries venturing into their already familiar CoRs will increase (Selmer et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2016). Moreover, the exogen shock caused by COVID-19 (Polack et al., 2020) increased the number of people working remotely (Ozimek, 2020), encouraging lifestyle-driven employees to move to new CoRs. This extraordinary event has underlined the notion that the cross border talent movement from developed economies is increasing. Thus, lifestyle entrepreneurship will likely increase, and the possibility of qualified and well-resourced individuals becoming opportunity seekers is high. Therefore, further research on this topic is crucial.

Fourth, to achieve a global perspective on the phenomenon, researchers must close geographical gaps. For example, none of the studies examined focused on India, and only one study investigated the African context. Nevertheless, the demographic developments in both places imply that their role in future economic developments will increase. Therefore, entrepreneurship from developed countries to these significant locations has likely already begun. If so, scholars must close this knowledge gap. Moreover, entrepreneurs who have lived abroad for a long time bring back numerous experiences, approaches and innovations (Dai & Liu, 2009; Liu et al., 2010) to their developed home countries. Thus, investigating returnee entrepreneurship from less developed economies to developed economies has excellent research potential.

Fifth, a more quantifiable methodological lens is necessary to better understand the effects and relations of variables that impact foreign entrepreneurs. The populations studied have been comparably small, and it is challenging to obtain a sufficiently large sample for a quantitative study. However, only when scholars overcome this obstacle can the field test new theoretical ideas and concepts to achieve significant knowledge about variables outcomes and dependencies. Qunatifying, for example, the average social and economic impact of a foreigner venturing abroad could be used as an argument for easing institutional challenges and actively supporting foreign entrepreneurship. This hurdle can be overcome primarily through collaboration and cooperation between researchers. Therefore, it is essential to build alliances to create shared access to scarce informants in the future.

Finally, the review shows that quantitative data on the phenomenon is generally scarce. International entrepreneurship research depends on investigating cross-border movements, which leads to challenges in identifying and accessing the population (Davidsson & Wiklund, 2001). Without access to high-quality data, the research field will not be able to unfold its full potential. An accurate recording of founder identities at the national state level or any other governing institution would be a good starting point to allow for interesting future research.

Conclusion

Approximately only one out of seven people live in a developed country. Therefore, entrepreneurial individuals from developed countries with a flair for seeking opportunities can play a unique role in driving technology transfer and creating global innovations. Moreover, impactful entrepreneurial activities positively affect social structures, thus contributing to the development of the countries that entrepreneurs venture to. Our review has shown that the individual context plays an essential role in foreign entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurs who have had their education in the world's most developed countries can contribute significantly to solving the global challenges ahead. Many opportunities arise outside their economies for a variety of reasons. Opportunities are not limited to a country’s borders, nor are talented entrepreneurs. The most populous countries, such as India and China, and also emerging countries in Africa and South America will become increasingly important economically, ecologically and socially in the coming years. Research on international entrepreneurship has shown that foreign entrepreneurs can contribute greatly to a country's entrepreneurial ecosystem. Furthermore, a connected world depends on migration in various directions that guarantee a steady exchange of ideas, knowledge, and culture. The effects of several decades of globalization bring along a new generation of entrepreneurs actively seeking global opportunities.

Therefore, it is of great academic and practical interest to better understand the foreign entrepreneurial process. The academic discourse would benefit from focusing on these individuals to gain more insights into the motivations behind and conditions of the entrepreneurial process, which are essential for establishing enterprises in foreign markets. This literature review is a starting point that offers an omnibus perspective on foreign entrepreneurship and highlights directions for future research.

Availability of data and material

Available upon request.

References

*included in the systematic literature selection

* Abd Hamid, H., Everett, A. M. (2021). Migrant entrepreneurs from an advanced economy in a developing country: the case of Korean entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 219–234.

Aldrich, H. E., & Waldinger, R. (1990). Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology, 16(1), 111–135.

* Almor, T., & Yeheskel, O. (2013). Footloose and fancy-free: Sojourning entrepreneurs in China. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 7(4), 354–372.

Basu, A. (2006). Ethnic minority entrepreneurship. The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship.

Baycan-Levent, T., & Nijkamp, P. (2009). Characteristics of migrant entrepreneurship in Europe. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 21(4), 375–397.

Block, J. H., & Wagner, M. (2010). Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs in Germany: Characteristics and earning s differentials. Schmalenbach Business Review, 62(2), 154–174.

Booth, A., Sutton, A., Clowes, M., & Martyn-St James, M. (2021). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2005). The social structures of the economy. Polity.

Bruton, G., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. (2010). Institutional Theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440.

* Carson, D. A., & Carson, D. B. (2018). International lifestyle immigrants and their contributions to rural tourism innovation: Experiences from Sweden’s far north. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 230–240.

Center for American Entrepreneurship. (2017). Immigrant founders of the fortune 500., Center for American Entrepreneurship. https://startupsusa.org/fortune500/#appendix.

* Chandra, Y., Styles, C., & Wilkinson, I. F. (2015). Opportunity portfolio: Moving beyond single opportunity explanations in international entrepreneurship research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(1), 199–228.

* Chrysostome, E. (2010). The success factors of necessity immigrant entrepreneurs: in search of a model. Thunderbird International Business Review, 52(2), 137–152.

Cobo, M. J., López-Herrera, A. G., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Herrera, F. (2011). Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1382–1402.

* Connelly, B. L. (2010). Transnational entrepreneurs, worldchanging entrepreneurs, and ambassadors: a typology of the new breed of expatriates. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(1), 39–53.

Dai, O., & Liu, X. (2009). Returnee entrepreneurs and firm performance in Chinese high-technology industries. International Business Review, 18(4), 373–386.

Davidsson, P., & Wiklund, J. (2001). Levels of analysis in entrepreneurship research: Current research practice and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(4), 81–100.

* De Cock, R., Andries, P., & Clarysse, B. (2021). How founder characteristics imprint ventures’ internationalization processes: the role of international experience and cognitive beliefs. Journal of World Business, 56(3), 101163.

Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Sage Publications Ltd.

* Dillon, S. M., Glavas, C., & Mathews, S. (2020). Digitally immersive, international entrepreneurial experiences. International Business Review, 29(6), 101739.

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: an emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001–1022.

* Eimermann, M., & Kordel, S. (2018). International lifestyle migrant entrepreneurs in two new immigration destinations: Understanding their evolving mix of embeddedness. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 241–252.

* Elo, M. (2016). Typology of diaspora entrepreneurship: Case studies of Uzbekistan. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 121–155.

Elo, M., Sandberg, S., Servais, P., Basco, R., Cruz, A. D., Riddle, L., & Täube, F. (2018). Advancing the views on migrant and diaspora entrepreneurs in international entrepreneurship. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 119–133.

* Elo, M., Täube, F., & Volovelsky, E. K. (2019). Migration ‘against the tide’: Location and Jewish diaspora entrepreneurs. Regional Studies, 53(1), 95–106.

Engelen, E. (2001). ‘Breaking in’ and ‘breaking out’: a Weberian approach to entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(2), 203–223.

* Ensign, P. C., & Robinson, N. P. (2011). Entrepreneurs because they are immigrants or immigrants because they are entrepreneurs? A critical examination of the relationship between the newcomers and the establishment. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 33–53.

Filatotchev, I., Liu, X., Lu, J., & Wright, M. (2011). Knowledge spillovers through human mobility across national borders: Evidence from Zhongguancun science park in China. Research Policy, 40(3), 453–462.

Fisch, C., & Block, J. (2018). Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Management Review Quarterly, 68(2), 103–106.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis (Vol. 241). University of California Press.

* Goxe, F., Mayrhofer, U., & Kuivalainen, O. (2022). Argonauts and Icaruses: Social networks and dynamics of nascent international entrepreneurs. International Business Review, 31(1), 101892.

Gruenhagen, J. H., Davidsson, P., & Sawang, S. (2020). Returnee entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review, thematic analysis, and research agenda. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 16(4), 310–392.

* Gurău, C., Dana, L. P., & Katz-Volovelsky, E. (2020). Spanning transnational boundaries in industrial markets: a study of Israeli entrepreneurs in China. Industrial Marketing Management, 89, 389–401.

Gusenbauer, M., & Haddaway, N. R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(2), 181–217.

* Heidenreich, S., Mohr, A., & Puck, J. (2015). Political strategies, entrepreneurial overconfidence and foreign direct investment in developing countries. Journal of World Business, 50(4), 793–803.

* Hudnut, P., & DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Envirofit international: a venture adventure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 785–797.

Honig, B. (2020). Exploring the intersection of transnational, ethnic, and migration entrepreneurship. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(10), 1974–1990.

Hymer, S. (1976). The international operations of national firms: a study of direct foreign investment. MIT Press.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2022). World Migration Report 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2022, from https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022

Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487.

Karanikolos, M., Heino, P., McKee, M., Stuckler, D., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2016). Effects of the global financial crisis on health in high-income OECD countries: a narrative review. International Journal of Health Services, 46(2), 208–240.

Kloosterman, R., & Rath, J. (2001). Immigrant entrepreneurs in advanced economies: Mixed embeddedness further explored. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(2), 189–201.

Kloosterman, R. C. (2010). Matching opportunities with resources: a framework for analyzing (migrant) entrepreneurship from a mixed embeddedness perspective. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(1), 25–45.

Kloosterman, R., & Rath, J. (2010). Shifting landscapes of immigrant entrepreneurship.

* Knight, J. (2015). The evolving motivations of ethnic entrepreneurs. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

Kollmann, T. (2020). Internationalität der Startup Teams., Deutscher Startup Monitor 2020. https://deutscherstartupmonitor.de/wpcontent/uploads/2020/09/dsm_2020.pdf .

Kraus, S., Breier, M., & Dasí-Rodríguez, S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(3), 1023–1042.

Kuckertz, A., & Block, J. (2021). Reviewing systematic literature reviews: Ten key questions and criteria for reviewers. Management Review Quarterly, 71(3), 519–524.

Kulchina, E. (2017). Do foreign entrepreneurs benefit their firms as managers? Strategic Management Journal, 38(8), 1588–1607.

* Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė, V., Duobienė, J., & Mihi-Ramirez, A. (2021). A comparison analysis between pre-departure and transitioned expat-preneurs. Frontiers in Psychology, 3539.

* Lassalle, P., & McElwee, G. (2016). Polish entrepreneurs in Glasgow and entrepreneurial opportunity structure. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

* Lassalle, P., & Scott, J. M. (2018). Breaking-out? A reconceptualization of the business development process through diversification: the case of Polish new migrant entrepreneurs in Glasgow. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(15), 2524–2543.

* Lassalle, P., Johanson, M., Nicholson, J. D., & Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2020). Migrant entrepreneurship and markets: the dynamic role of embeddedness in networks in the creation of opportunities. Industrial Marketing Management, 91, 523–536.

Light, I., Bhachu, P., & Karageorgis, S. (2017). Migration networks and immigrant entrepreneurship. In Immigration and entrepreneurship (pp. 25-50). Routledge

Liu, X., Lu, J., Filatotchev, I., Buck, T., & Wright, M. (2010). Returnee entrepreneurs, knowledge spillovers and innovation in high-tech firms in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1183–1197.

Lopes, T., Guimaraes, C., Saes, A., & Saraiva, L. (2018). The ‘disguised’ foreign investor: Brands, trademarks and the British expatriate entrepreneur in Brazil. Business History, 60(8), 1169–1193.

* Lundberg, H., & Rehnfors, A. (2018). Transnational entrepreneurship: Opportunity identification and venture creation. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 150–175.

* March-Chordà, I., Adame-Sánchez, C., & Yagüe-Perales, R. M. (2021). Key locational factors for immigrant entrepreneurs in top entrepreneurial ecosystems. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1049–1066.

* Marshall, R. S. (2011). Conceptualizing the international for-profit social entrepreneur. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(2), 183–198.

* McHenry, J. E., & Welch, D. E. (2018). Entrepreneurs and internationalization: a study of Western immigrants in an emerging market. International Business Review, 27(1), 93–101.

* Ngoma, T. (2016). It is not whom you know, it is how well you know them: Foreign entrepreneurs building close guanxi relationships. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 239–258.

* Nkongolo-Bakenda, J. M., & Chrysostome, E. V. (2013). Engaging diasporas as international entrepreneurs in developing countries: In search of determinants. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 30–64.

North, D. C. (1990). An introduction to institutions and institutional change. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, 3–10.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2006). Developed, developing countries. Available from https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=6326. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2022). Full member list. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/about/

Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (2005). Defining international entrepreneurship and modeling the speed of internationalization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 537–553.

Ozimek, A. (2020). The future of remote work. Available at SSRN 3638597.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 1–11.

Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual Internationalization vs Born-Global/International new venture models: a review and research agenda. International Marketing Review., 36(6), 830–858.

Peiris, I. K., Akoorie, M. E., & Sinha, P. (2012). International entrepreneurship: a critical analysis of studies in the past two decades and future directions for research. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 10(4), 279–324.

Polack, F. P., Thomas, S. J., Kitchin, N., Absalon, J., Gurtman, A., Lockhart, S., et al. (2020). Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 2603–2615. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110345

Rivera-Santos, M., Holt, D., Littlewood, D., & Kolk, A. (2015). Social entrepreneurship in SubSaharan Africa. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 72–91.

Robinson, J. A., & Acemoglu, D. (2012). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity and poverty (pp. 45–47). Profile.

Saxenian, A. (2000). Silicon Valley’s new immigrant entrepreneurs.

Saxenian, A., Motoyama, Y., & Quan, X. (2002). Local and global networks of immigrant professionals in Silicon Valley. Public Policy Institute of CA.

Saxenian, A. (2007). The new argonauts: Regional advantage in a global economy. Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J., & Backhaus, U. (2003). The theory of economic development. In Joseph Alois Schumpeter (pp. 61–116). Springer Boston, MA.

Scopus. (2022). CiteScore™ Percentile 2020. Calculated by Scopus on 02.03.2022 for Business, Management and Accounting (miscellaneous). Available from https://www.scopus.com/sourceid/145670?origin=resultslist#tabs=1

* Selmer, J., McNulty, Y., Lauring, J., & Vance, C. (2018). Who is an expat-preneur? Toward a better understanding of a key talent sector supporting international entrepreneurship. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 134–149.

Sifneos, E. (2010). Mobility, risk and adaptability of the diaspora merchants: the case of the Sifneo Frères family firm in Taganrog (Russia), Istanbul and Piraeus, 1850–1940. Historical Review, 7, 239–252.

* Shin, K. H. (2014). Korean entrepreneurs in Kansas City metropolitan area: an immigrant community under ethnic local and global intersection. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

* Storti, L. (2014). Being an entrepreneur: Emergence and structuring of two immigrant entrepreneur groups. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(7–8), 521–545.

Stovold, E., Beecher, D., Foxlee, R., & Noel-Storr, A. (2014). Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: an adapted PRISMA flow diagram. Systematic Reviews, 3(1), 1–5.