Abstract

Background

Physical fitness status is a key aspect of health and, consequently, it is important to create and adopt appropriate interventions to maintain or improve it, and assess it using valid measures. While in other testing contexts, standard operating procedures (SOPs) are commonly and widely adopted, in physical fitness testing, a variety of unstandardized testing protocols are proposed.

Aims

The topic of this review was to evaluate the existing literature on SOPs in physical fitness assessment and to provide guidelines on how SOPs could be created and adopted.

Method

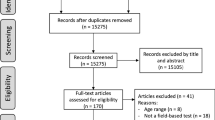

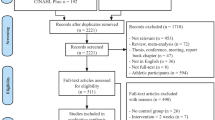

The electronic databases PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus were screened and original, peer-reviewed studies that included SOPs, related to physical fitness, were recorded.

Results

After the inclusion and exclusion criteria screening, a total of six studies were included and these were critically and narratively analyzed.

Conclusions

Standard operating procedures are rarely adopted in the field of physical fitness and a step by step guide has been provided in this manuscript. In the future, it is suggested to follow protocols as a routine, because this is the only way to generalize and contextualize findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) [1] states that Governments should promote and protect people’s health via a properly designed health promotion program, as it is cheaper compared to medical intervention or treatment, hence limiting healthcare costs [2, 3]. Unfortunately, in the past years, a rise in overweight and obese children has been observed [4], increasing both, cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors [5]. Furthermore, by 2050, it is anticipated that at least one in five people will be over 60 years old [6], thus programs to guarantee a “Healthy Ageing” are required [6].

Recently, an increasing number of valid and useful fitness disciplines and high-intensity protocols have been suggested as interventions [7]. In addition, the American College of Sports Medicine [8] proposed intervention guidelines to improve health. In parallel, protocols for the evaluation of physical fitness (PF), which is composed of health- and skill-related attributes [9], have also evolved. These protocols are especially focalized on health-related components (cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength, flexibility, and body composition), because they have important positive effects on the human body [7]. Field-testing protocols based on fitness evaluation batteries adopted for children and adolescents, such as the AVENA study [10], the FITNESSGRAM [11], the HELENA study [12], and the ASSO project [13] also exist. Furthermore, laboratory test for cardiorespiratory [14, 15], muscle strength [16], and flexibility [16] components are valid and widely adopted. Also, field test for cardiorespiratory [17,18,19], muscle strength [20], and flexibility [21, 22] were proposed. Unfortunately, these studies tend to use variations in testing procedures and none of them adopted Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) even if in the literature, the use of SOPs, is suggested [23, 24].

Standard Operating Procedures are documents that provide details of a process to allow the correct repetition of all steps [23, 24], they are adopted in many disciplines [23] in which standardization is required, such as nuclear power plants, aviation, offshore oil industry, hospital emergency care, and emergency response services [25], in an ergonomic environment [26], or in the management and recommendation for diagnosis and treatment of pathologies [27]. Using SOPs in the research field would allow for better comparison between studies and the creation of normative data. Moreover, the use of SOPs makes studies safer, preventing misconduct, mistreatment or potential legal or ethical issues, especially in children [28]. The knowledge of the “what” and the “how” aspects is fundamental for the success and the safety of the activities [25].

The extensive use of SOPs and their importance in many fields could be a practical and feasible approach also in the PF environment to create a common direction in research and in everyday life. For this reason, the objective of this review was to evaluate what exists in the PF literature related to SOPs and to provide guidelines on SOPs creation and use.

Methods

Electronic databases PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus were screened to collect studies for this review. The following keywords groups were matched with the Boolean operator “AND” (i.e. standard operating procedure AND sport):

-

Group 1: standard operating procedure, standard operating procedures; SOP.

-

Group 2: sport; fitness, physical activity; physical performance, physical education, sport evaluation, sport test, fitness evaluation; fitness test.

The studies were included if they were related to Sport Sciences field and if SOPs were included in their evaluation. No limitations on the age of the participants or related to physical, cognitive or mental disorders were adopted. Concerning the intervention, manuscripts were included only if the topic was related to physical fitness. No limitation on the comparators and outcomes were adopted. Only studies original and peer-reviewed were included. Abstracts, opinion articles, citations, scientific conference abstracts, books or book reviews, statements, editorials, letters, and commentaries were excluded.

Results

Six studies adopted or created SOPs in PF assessment. Half of these studies included are guidelines for populations related to a medical environment, such as people with inflammatory arthritis [29] or with chronic respiratory disease [30, 31].

The SOPs adopted in two studies [30, 31] are for the 6-min walk test, the incremental shuttle walks test and the endurance walk. To our knowledge, only one study, represented by two publications, explicitly adopted SOPs in the context of PF testing. This study was a multi-country gender-sensitized, health and lifestyle program targeting physical activity, sedentary time and dietary behaviors in men [32, 33]. The studies [32, 33] stated that SOPs were created to ensure quality and consistency during the data collection and analysis across the participating countries [32, 33].

A review article [34] investigated vertical jumps in physically active adolescents. This article aimed to study if there was a protocol commonly adopted and, if there was none, to review the common aspects between the protocols revised. There was not a protocol commonly adopted and SOPs were created for the countermovement jump and the squat jump tests [34]. A summary of guidelines for SOPs creation and use is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Discussion

In the PF literature, SOPs are rarely adopted, consequently, from the studies included, guidelines related to SOPs are summarized in Fig. 1 and will be discussed. The focus of this review is on the procedure followed by the authors to create SOPs rather than SOPs themselves. Mainly from the procedure of Holland and colleagues [30, 31], but also considering the other studies that adopted SOPs in PF [29, 32,33,34] a three steps process as guidelines to create SOPs has been suggested. The first step should be a creation of a multinational and multidisciplinary team of experts in the field to consider different possible aspects. Indeed, health promotion is a complex and multifaceted concept with implications on physical, mental and social well-being [1]. The second step consists in the performance of a review of the literature to analyze what other authors adopted and how they proceeded, during this phase, the task force should identify the most common procedure or create SOPs (see step 3) [30, 31, 34]. Important aspects of this step are how the protocol could affect performance, but also its reliability (obtaining the same results if the test is repeated), its validity (the correspondence between the test and the purpose for which it was created), and its feasibility (how easy it is to implement) [16, 35,36,37]. These aspects have to be considered especially in field tests that usually are less reliable than laboratory tests [38]. A potential learning effect has to be counted, because when a task is repeated, there is an improvement in performance efficacy [39, 40]. Furthermore, it would be useful to evaluate the relationship between test performance and clinical outcomes, with an in-depth analysis of the protocol characteristics and the scientific literature related to the topic.

The third step is the creation of SOPs and the aspects to consider are the protocol, the equipment and the measurements adopted, as well as testing location [30, 31, 34]. A standardized procedure before data collection, from the participant preparation and baseline assessments to the preparation of the investigators (with appropriate training about the instructions to give to participants and the behaviors to adopt) [30, 31, 34], is required not only in clinical studies but also in systematic reviews and meta-analysis for which it is suggested to register the procedure before the study [41,42,43]. During the test is important for administrators to know what to do and how, and also to know the indications for stopping a test. Furthermore, following a procedure helps ill-informed and inexperienced researchers to avoid problems related to possible risks [28]. Immediately after, recovery management needs to be documented (active or passive) as well as the time between the tests due to its influence on the performance [44, 45]. Finally, it is crucial to standardize the data management process, especially if a multidisciplinary and multinational team is involved and if the work is managed remotely. It would be ideal to try the procedure several times to reduce the difference between theory and practice.

One important limitation of SOPs is whether the protocol is personalized according to participants’ characteristics. Indeed, if a specific population such as elite athletes, or people with disabilities is studied, the test could be task-specific or accessible to that population. Using a protocol in high-level athletes created for sedentary people does not helps coaches and athletes to know the limits. Otherwise, in the health promotion context, according to us, it is fundamental to follow SOPs.

Limitations of this review include the few Sport Sciences studies found that explicitly mentioned using SOPs, making it impossible to write a systematic review and meta-analysis. Future studies should start to create or follow SOPs in Sport Sciences field, especially for PF field tests.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the creation of SOPs in the PF field, especially in a health promotion context, is necessary and these procedures standardized should be systematically adopted in future investigations. Only in this way, it will be possible to generalize easily the findings and contextualize the results with the existing literature.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PF:

-

Physical fitness

- SOPs:

-

Standard operating procedures

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO (1946) Costitution of the World Health Organization. https://wwwwhoint/about/who-we-are/constitution

Galloway RD (2003) Health promotion: causes, beliefs and measurements. Clin Med Res 1(3):249–258. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.1.3.249

Fries JF, Harrington H, Edwards R, Kent LA, Richardson N (1994) Randomized controlled trial of cost reductions from a health education program: the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS) study. Am J Health Promot 8(3):216–223. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-8.3.216

Dollman J, Norton K, Norton L (2005) Evidence for secular trends in children’s physical activity behaviour. Br J Sports Med 39(12):892–897. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2004.016675 (discussion 897)

Gong CD, Wu QL, Chen Z, Zhang D, Zhao ZY, Peng YM (2013) Glycolipid metabolic status of overweight/obese adolescents aged 9- to 15-year-old and the BMI-SDS/BMI cut-off value of predicting dyslipidemiain boys, Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 12:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-12-129

WHO (2015) World report on ageing and health. https://tinyurlcom/y8mxb29d

Paoli A, Bianco A (2015) What is fitness training? Definitions and implications: a systematic review article. Iran J Public Health 44(5):602–614

ACSM (1998) American college of sports medicine position stand. The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30(6):975–991. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199806000-00032

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM (1985) Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 100(2):126–131

Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, Moreno LA, Urzanqui A, Gonzalez-Gross M, Sjostrom M, Gutierrez A, Grp AS (2008) Health-related physical fitness according to chronological and biological age in adolescents. The AVENA study. J Sport Med Phys Fit 48(3):371–379

Morrow JR, Martin SB, Jackson AW (2010) Reliability and validity of the FITNESSGRAM (R): quality of teacher-collected health-related fitness surveillance data. Res Q Exercise Sport 81(3):S24–S30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2010.10599691

Ortega FB, Artero EG, Ruiz JR, Espana-Romero V, Jimenez-Pavon D, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Moreno LA, Manios Y, Beghin L, Ottevaere C, Ciarapica D, Sarri K, Dietrich S, Blair SN, Kersting M, Molnar D, Gonzalez-Gross M, Gutierrez A, Sjostrom M, Castillo MJ, Grp HS (2011) Physical fitness levels among European adolescents: the HELENA study. Brit J Sport Med 45(1):20–29. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.062679

Bianco A, Jemni M, Thomas E, Patti A, Paoli A, Ramos Roque J, Palma A, Mammina C, Tabacchi G (2015) A systematic review to determine reliability and usefulness of the field-based test batteries for the assessment of physical fitness in adolescents—the ASSO project. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 28(3):445–478. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00393

Bruce RA, McDonough JR (1969) Stress testing in screening for cardiovascular disease. Bull N Y Acad Med 45(12):1288–1305

Astrand PO (1976) Quantification of exercise capability and evaluation of physical capacity in man. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 19(1):51–67

Lamb KLB, D A, Roberts K (1988) Physical fitness and health-related fitness as indicators of a positive health state. Health Promot Int 3(2):171–182

Cooper KH (1968) A means of assessing maximal oxygen intake. Correlation between field and treadmill testing. JAMA 203(3):201–204

Leger LA, Lambert J (1982) A maximal multistage 20 m shuttle run test to predict VO2 max. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 49(1):1–12

Rikli RE, Jones CJ (2013) Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist 53(2):255–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns071

Zemkova E, Hamar D (2018) Sport-specific assessment of the effectiveness of neuromuscular training in young athletes. Front Physiol 9:264. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00264

Wells KFD, E K (1952) The sit and reach—a test of back and leg flexibility. Res Q Am Assoc Health Phys Educ Recreat 23(1):115–118

Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Max J, Noffal G (1998) The reliability and validity of a chair sit-and-reach test as a measure of hamstring flexibility in older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 69(4):338–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1998.10607708

Angiuoli SV, Gussman A, Klimke W, Cochrane G, Field D, Garrity G, Kodira CD, Kyrpides N, Madupu R, Markowitz V, Tatusova T, Thomson N, White O (2008) Toward an online repository of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for (Meta) genomic annotation. OMICS 12(2):137–141. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2008.0017

Tuck MK, Chan DW, Chia D, Godwin AK, Grizzle WE, Krueger KE, Rom W, Sanda M, Sorbara L, Stass S, Wang W, Brenner DE (2009) Standard operating procedures for serum and plasma collection: early detection research network consensus statement standard operating procedure integration working Group. J Proteome Res 8(1):113–117. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr800545q

Righi AW, Saurin TA (2015) Complex socio-technical systems: characterization and management guidelines. Appl Ergon 50:19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2015.02.003

Susihono WASMG, G (2018) Design of standard operating procedure (SOP) based at ergonomic working attitude through musculoskeletal disorders (Msd’s) complaints. MATEC Web Conf. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201821804019 (ICIEE 2018)

Bellutti Enders F, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, Constantin T, Dolezalova P, Feldman BM, Lahdenne P, Magnusson B, Nistala K, Ozen S, Pilkington C, Ravelli A, Russo R, Uziel Y, van Brussel M, van der Net J, Vastert S, Wedderburn LR, Wulffraat N, McCann LJ, van Royen-Kerkhof A (2017) Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis 76(2):329–340. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209247

Randall D, Childers-Buschle K, Anderson A, Taylor J (2015) An analysis of child protection ‘standard operating procedures for research’ in higher education institutions in the United Kingdom. BMC Med Ethics 16(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0058-0

Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, Adams J, Brodin N, Dagfinrud H, Duruoz T, Esbensen BA, Gunther KP, Hurkmans E, Juhl CB, Kennedy N, Kiltz U, Knittle K, Nurmohamed M, Pais S, Severijns G, Swinnen TW, Pitsillidou IA, Warburton L, Yankov Z, Vliet Vlieland TPM (2018) 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77(9):1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585

Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, Puhan MA, Pepin V, Saey D, McCormack MC, Carlin BW, Sciurba FC, Pitta F, Wanger J, MacIntyre N, Kaminsky DA, Culver BH, Revill SM, Hernandes NA, Andrianopoulos V, Camillo CA, Mitchell KE, Lee AL, Hill CJ, Singh SJ (2014) An official European respiratory society/American thoracic society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 44(6):1428–1446. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00150314

Holland AE, Spruit MA, Singh SJ (2015) How to carry out a field walking test in chronic respiratory disease. Breathe (Sheff) 11(2):128–139. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.021314

van de Glind I, Bunn C, Gray CM, Hunt K, Andersen E, Jelsma J, Morgan H, Pereira H, Roberts G, Rooksby J, Roynesdal O, Silva M, Sorensen M, Treweek S, van Achterberg T, van der Ploeg H, van Nassau F, Nijhuis-van der Sanden M, Wyke S (2017) The intervention process in the European Fans in Training (EuroFIT) trial: a mixed method protocol for evaluation. Trials 18(1):356. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2095-0

van Nassau F, van der Ploeg HP, Abrahamsen F, Andersen E, Anderson AS, Bosmans JE, Bunn C, Chalmers M, Clissmann C, Gill JM, Gray CM, Hunt K, Jelsma JG, La Guardia JG, Lemyre PN, Loudon DW, Macaulay L, Maxwell DJ, McConnachie A, Martin A, Mourselas N, Mutrie N, Nijhuis-van der Sanden R, O’Brien K, Pereira HV, Philpott M, Roberts GC, Rooksby J, Rost M, Roynesdal O, Sattar N, Silva MN, Sorensen M, Teixeira PJ, Treweek S, van Achterberg T, van de Glind I, van Mechelen W, Wyke S (2016) Study protocol of European Fans in Training (EuroFIT): a four-country randomised controlled trial of a lifestyle program for men delivered in elite football clubs. BMC Public Health 16:598. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3255-y

Petrigna L, Karsten B, Marcolin G, Paoli A, D’Antona G, Palma A, Bianco A (2019) A review of countermovement and squat jump testing methods in the context of public health examination in adolescence: reliability and feasibility of current testing procedures. Front Physiol 10:1384. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01384

Davis KL, Kang M, Boswell BB, DuBose KD, Altman SR, Binkley HM (2008) Validity and reliability of the medicine ball throw for kindergarten children. J Strength Cond Res 22(6):1958–1963. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181821b20

Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Myer GD (2011) Exercise deficit disorder in youth: a hidden truth. Acta Paediatr 100(11):1423–1425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02461.x (discussion 1425)

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP, American College of Sports M (2011) American college of sports medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43(7):1334–1359. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

Heyward VH (1991) Advanced fitness assessment and exercise prescription. Human Kinetics Books, Champaign, IL 3(2):1–50

Gardner EB (1967) The neurophysiological basis of motor learning. A review. Phys Ther 47(12):1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/47.12.1115

Petrigna L, Pajaujiene S, Iacona GM, Thomas E, Paoli A, Bianco A, Palma A (2020) The execution of the Grooved Pegboard test in a dual-task situation: a pilot study. Heliyon 6(8):e04678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04678

Mayo-Wilson E, Heyward J, Keyes A, Reynolds J, White S, Atri N, Alexander GC, Omar A, Ford DE, National Clinical Trials R, Results Reporting Taskforce Survey S (2018) Clinical trial registration and reporting: a survey of academic organizations in the United States. Bmc Med 16(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1042-6

ISRCTN Registry. Available online: https://www.isrctn.com/ (Accessed on 30 April 2020)

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med 3(3):e123-130

Faigenbaum AD, McFarland JE, Kelly NA, Ratamess NA, Kang J, Hoffman JR (2010) Influence of recovery time on warm-up effects in male adolescent athletes. Pediatr Exerc Sci 22(2):266–277. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.22.2.266

Sanchez-Urena B, Martinez-Guardado I, Crespo C, Timon R, Calleja-Gonzalez J, Ibanez SJ, Olcina G (2017) The use of continuous vs intermittent cold water immersion as a recovery method in basketball players after training: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Sports Med 45(2):134–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2017.1292832

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Palermo within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LP and AB developed the aim of the manuscript. The literature search and data synthesis has been performed by LP, APal and AB. The first draft of the manuscript has been written by LP and SP, reviewed and improved by AD, MG-L and APao. The final manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petrigna, L., Pajaujiene, S., Delextrat, A. et al. The importance of standard operating procedures in physical fitness assessment: a brief review. Sport Sci Health 18, 21–26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00849-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00849-1