Abstract

Aims

Regular exercise is considered a cornerstone in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). It improves glucose control and cardiovascular risk factors, contributes to weight loss, and also improves general well-being, likely playing a role in the prevention of chronic complications of diabetes. However, compliance to exercise recommendations is generally inadequate in subjects with T2DM. Walking is the most ancestral form of physical activity in humans, easily applicable in daily life. It may represent, in many patients, a first simple step towards lifestyle changes. Nevertheless, while most diabetic patients do not engage in any weekly walking, exercise guidelines do not generally detail how to improve its use. The aims of this document are to conduct a systematic review of available literature on walking as a therapeutic tool for people with T2DM, and to provide practical, evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding its utilization in these subjects.

Data synthesis

Analysis of available RCTs proved that regular walking training, especially when supervised, improves glucose control in subjects with T2DM, with favorable effects also on cardiorespiratory fitness, body weight, and blood pressure. Moreover, some recent studies have shown that even short bouts of walking, used for breaking prolonged sitting, can ameliorate glucose profiles in diabetic patients with sedentary behavior.

Conclusions

There is sufficient evidence to recognize that walking is a useful therapeutic tool for people with T2DM. This document discusses theoretical and practical issues for improving its use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Physical activity is unanimously considered a cornerstone in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1,2,3]. It improves blood glucose and cardiovascular risk factors, contributes to weight loss, and improves general well-being, likely playing a role in the prevention of chronic diabetes complications. A meta-analysis of structured exercise interventions, consisting of aerobic training, resistance training, or both for at least 12 weeks, concluded that regular exercise may lower HbA1C by an average of 0.67% in diabetic subjects, as compared with standard care, even in the absence of a significant reduction in BMI [4]. Interestingly, both aerobic and resistance exercise may improve metabolic features and body composition, also reducing liver fat content, in people with T2DM [5, 6], although combined exercise may have greater effects on blood glucose [7, 8]. It is noteworthy that both physical inactivity and increased sedentary time have been recognized as distinct and independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease, T2DM, and all-cause mortality [9, 10].

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that most adults with diabetes accumulate at least 150 min of moderate to-vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week, spread over at least three days per week, avoiding more than two consecutive days without activity. However, shorter durations (at least 75 min per week) of vigorous intensity or interval training may be sufficient and can be prescribed in these patients, especially in younger and more physically fit individuals. In addition, adults with diabetes should engage in two-to-three sessions per week of resistance exercise, on nonconsecutive days. Yoga and tai chi may be included in exercise programs, as an alternative to the traditional exercise training. Flexibility and balance exercises are also recommended for older subjects with diabetes, to improve joint mobility and reduce falls. Finally, all adults with T2DM should decrease the amount of time spent in sedentary behavior, interrupting prolonged sitting with short bouts of light activity about every 30 min, for blood glucose and general health benefits. This latter recommendation is intended to be additional to, and not a replacement for, increased structured exercise [11].

However, physical activity is largely underused in diabetic patients, who typically show lower values of energy expenditure, number of steps, and overall physical activity volume, as compared to non-diabetic subjects [12, 13]. Indeed, data from the 1999–2002 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that the vast majority of T2DM patients are physically inactive, with only 28.2% of them achieving the recommended levels of physical activity [14]. More recently, in another large nationwide survey which included almost 500,000 individuals with a weighted prevalence of diabetes of 9.8%, carried out by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the proportion of diabetic subjects meeting the ADA recommendations was 41.1% for aerobic exercise, and just 12.4% for resistance exercise [15]. These figures in people with diabetes were substantially lower than the corresponding values in non-diabetic individuals (51.5% and 21%, respectively). In diabetic subjects, the demographic and clinical characteristics associated with physical inactivity included sex (female), low education level, living in economically poorer areas, and a BMI corresponding to overweight/obesity. In addition, the proportion of subjects meeting aerobic exercise recommendations was significantly lower in Black, non-Hispanic people, as compared with White people, and in the 55–64 years age group, as compared with subjects over 65. Conversely, among factors associated with a low adherence to resistance exercise recommendations, there were a lack of previous education in diabetes management, insulin use, and low frequency of home blood glucose testing [15]. Interestingly, while in the general population of developed countries, sedentary time — i.e., the time spent sitting or engaged in activities with very low energy expenditure during waking hours — was estimated to be approximately 6–7 h/day [16], in a cohort of T2DM patients, it was as high as 11 h/day [17].

A number of reasons may contribute to these findings, including cultural and socioeconomic factors, individual physical limitations, fear of hypoglycemia (in patients receiving insulin or some insulin secretagogues), physicians’ inadequate knowledge of exercise prescription principles and their scarce perception of the importance of lifestyle measures as compared with pharmacological tools, and also poor support for exercise programs from the health care systems. Low walkability and lack of physical activity facilities may be additional issues, especially in large urban areas [18]. However, there is also evidence that subjects with T2DM may have a disease-specific impairment of physical performance, as compared with age- and BMI-matched non-diabetic people. Individuals with diabetes often report physical fatigue as a cause of physical activity limitation [19]. Accordingly, it has been estimated that mean maximal aerobic capacity in typical T2DM patients may be as low as 22 ml/kg min, corresponding to a maximal exercise intensity of 6.4 MET [20]. Moreover, in these subjects, glycation of musculoskeletal structures, driven by chronic hyperglycemia, may cause stiffening of the tendons, contributing to increased energy expenditure and limited exercise capacity [21]. Spontaneous, unsupervised physical activity may, therefore, occur at a lower intensity in diabetic patients, as compared with non-diabetic subjects [22], with a potential reduction in the expected beneficial effects of exercise.

A number of subjective and objective barriers may thus limit physical activity in patients with diabetes. In this regard, well-organized, structured counseling is required to develop appropriate individual strategies able to improve lifestyle and increase physical activity [23]. The results of some real-life long-term studies [24, 25] have supported the efficacy of structured and tailored lifestyle interventions in these subjects. However, in the Look AHEAD Trial, in which intensive lifestyle intervention was compared with standard care in a large cohort of obese people with T2DM, physical fitness substantially increased after 1 year, but the improvement in physical capacity was then progressively lost, suggesting early reduction in the adherence to physical activity counseling [26].

Walking is the most ancestral form of physical activity, easily applicable in daily life. It may represent, in many patients, a first simple step towards lifestyle changes. Interestingly, a recent study in postmenopausal women at high risk for T2DM proved that both standing and walking acutely reduce post-prandial glucose, insulin, and non-esterified fatty acid response, as compared with prolonged sitting [27], indicating that standing up and walking may be sufficient to improve the metabolic profile in sedentary people. However, 54.6% of patients with T2DM have reported that they did not engage in any weekly walking [28]. Moreover, amount, duration, intensity, and other characteristics of walking are generally not detailed by exercise guidelines. The aim of this document was to review available literature on walking as a therapeutic tool for people with T2DM, and to provide practical, evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding its use in these patients.

Materials and methods

In 2019, the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID), the Italian Association of Medical Diabetologists (AMD), and the Italian Society of Motor and Sports Sciences (SISMES) deemed necessary an improvement in the use of walking for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in subjects with type 2 diabetes, and appointed a six-member Task Force to develop evidence-based practice guidelines on this topic. The Task Force followed the approach suggested by the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) group, regarding the development of evidence-based guidelines [29].

The Task Force used the best available research evidence to draw up the recommendations, covering evidence quality, feasibility, acceptability, cost, implementation, and finally recommendation strength, balancing benefits, and harms.

The review protocol has been registered on the Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42020171515).

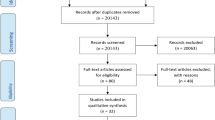

This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Supplemental Table 1).

The sources searched were PubMed, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The search was restricted to articles in English, in the period from January 1, 1966 to February 29, 2020. The preliminary search strategy utilized terms related to exercise, physical activity, or walking, type 2 diabetes, and randomized-controlled trials or clinical trials. Available systematic reviews and meta-analyses were also searched to find additional studies. Two reviewers selected studies for inclusion in the systematic review, whereas any disagreement was resolved through assessment by all the review team members.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they conformed to the following criteria: (a) subjects with type 2 diabetes; (b) participation in a structured walking program; (c) comparison with a non-exercise control group receiving standard care; (d) adoption of a randomized, controlled design; (e) length of intervention at least 8 weeks; (f) availability of data regarding the primary outcome—changes in glycemic control as assessed by HbA1c, and/or the secondary outcomes—changes in fasting or OGTT glucose or glucose daily profiles measured by continuous glucose monitoring, changes in BMI or body fat, blood pressure, serum lipids, physical performance, or other relevant clinical endpoints (well-being/quality of life, insulin resistance, other cardiovascular risk markers, antidiabetic therapy, diabetes chronic complications). Studies were excluded if: (a) data included subjects with pre-diabetes or other types of diabetes; (b) walking intervention was combined with other types of exercise, (c) intervention consisted only of advising an increase in daily walking steps; (d) exercise was combined with changes in diet; (e) controls received another type of exercise intervention; (f) only posters or abstracts were available.

Initial screen of studies was based on titles and abstracts of publications; when studies were potentially eligible or information was insufficient or unclear, full-text articles were examined. Among 1872 screened papers, 28 were eligible for inclusion. For each included paper, data regarding study authors and publication year, characteristics of recruited subjects (including sample size, mean age, baseline BMI, and HbA1c), intervention length and characteristics (including walking modality and intensity, weekly frequency of sessions, and duration of each session), supervision status, adherence, dropout rate, and outcomes (including at least one of the followings: differences in mean changes of glucose control parameters, body composition, physical performance and other relevant issues, such as well-being, serum lipids, blood pressure, insulin resistance, inflammatory markers, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, antidiabetic therapy, and chronic complications of diabetes), were extracted and collected. Two reviewers extracted data, which were recorded in an excel spreadsheet. Any disagreement was resolved through assessment by the review team members. The methodological quality of eligible studies was estimated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [30], which includes random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting (Supplemental Table 2).

The quality of the evidence was categorized according to the number and design of studies addressing the outcome, assessment of the quality of the studies, relevant statistical data, and significance of the endpoints. A graphical description of the strength of a recommendation and of the quality of the underlying evidence was adopted: for strong recommendations, the words “we recommend” and the number 1 were used, whereas for weak recommendations, the words “we suggest” and the number 2 were used. Slashed circles indicated the quality of the evidence. In this regard, ØOOO indicated very-low-quality evidence; ØØOO, low quality; ØØØO, moderate quality; and ØØØØ, high quality. In general, the Task Force believes that subjects receiving care according to the strong recommendations will derive, on average, more benefits than drawbacks. Weak recommendations require more careful attention to the specific circumstances and a subject’s preferences before deciding the best choice.

Linked to each recommendation is a brief description of the values that members of the task force considered in making the recommendation, and, where indicated, technical comments that facilitate the implementation of recommendations. These were often derived from the nonsystematic remarks of the panelists and should, therefore, be considered suggestions only.

All Task Force members had previously declared any potential conflicts of interest. Conflicts of interest were defined by payment in any amount from private commercial entities in the form of consulting fees, salary, ownership interest, grants, research support, payments for participation in speakers’ bureaus or advisory boards, or any other financial benefits.

The Task Force received no external funding or remuneration from other entities, while the three scientific Societies provided all the support for this document.

The recommendations and suggestions made by the Task Force were approved by the three funding Societies before the final document was submitted for publication.

Evidence supporting walking as a therapy for type 2 diabetes

Evidence of the beneficial effects of walking in subjects with type 2 diabetes, based on findings of appropriately designed RCTs, is limited. The vast majority of available studies are small and short term. Moreover, lifestyle intervention often includes changes in diet, which strongly hamper the interpretation of the effect of exercise per se in many studies. Nevertheless, several papers have consistently suggested the beneficial effects of walking for people with diabetes. In this regard, the Task Force identified a systematic review and meta-analysis that addressed the effects of walking on glucose controls and other cardiovascular risk factors, such as body weight, blood pressure, and serum lipids, in subjects with T2DM [31]. Inclusion criteria in this analysis were RCTs that examined the effects of structured walking programs vs non-exercise/standard care in patients with T2DM, in the absence of any dietary interventions or combination with other types of exercise, and with a duration of at least 8 weeks. Eighteen studies, involving 20 RCTs and 866 participants, were included. The results of this meta-analysis supported the conclusion that walking is effective in decreasing HbA1c, by an average of 0.50% (95% CI 0.70–0.21%), in diabetic patients, and that it may also reduce body mass index, by 0.91 kg/m2 (95% CI, 1.22–0.59 kg/m2) and diastolic blood pressure, by 1.97 mmHg (95% CI 3.94–0.00 mmHg). However, evidence was insufficient as regards the effects on systolic blood pressure and serum lipid profile. In the meta-analysis, a predefined subgroup analysis showed that a statistically significant improvement in HbA1c, by an average of 0.58% (95% CI 0.93–0.23), was seen especially when intervention was supervised, whereas the change did not reach statistical significance in non-supervised studies. Univariate meta-regression analysis showed that none of the several examined covariates, such as age, BMI, sex, duration of diabetes, length of intervention, and walking frequency or volume was a significant modifier of HbA1c improvement. The authors reported that when individually removing each trial, results were unchanged. As regards the effect of walking on BMI, mean weighted reduction was statistically significant but clinically small, in accordance with the evidence that substantial weight loss requires multidimensional interventions.

These findings were updated by the Task Force, by including the results of these studies in terms of physical performance and other relevant endpoints, and by extending the literature search up to February 22, 2019. A similar analysis was thereafter carried out into the effects of walking as a strategy for interrupting prolonged sitting.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics, and Table 2 summarizes the main findings of studies included in the meta-analysis, and in the additional studies identified in the updated analysis of the literature [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. However, one paper included in the original meta-analysis was excluded in this revision, due to a dietary intervention that was combined with non-supervised walking [59].

The conclusions of the meta-analysis were confirmed by the findings in our update. The assessment of other clinical aspects of diabetes was limited. The duration and design of available studies make it quite difficult to ascertain if training may have any effects on the chronic complication of diabetes. Only a small study, split into different publications, reported changes in several functional aspects of diabetic neuropathy [36,37,38,39]. Sparse findings in these RCTs suggested favorable effects of structured walking on oxidative stress, endothelial function, and subclinical chronic inflammation, which are considered key mechanisms in the increased cardiovascular risk associated with diabetes. Changes after intervention in insulin resistance, a fundamental aspect in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and its complications, were investigated by several studies, but results were inconsistent. Most of these analyses relied on surrogate indices of insulin resistance, especially the HOMA-IR index, and several of them did not show any clear improvement in this parameter. Neither were any significant changes reported in three studies that investigated this issue by using the insulin tolerance test [45, 46, 48]. However, a study that measured insulin sensitivity by the hyperglycemic clamp, and also investigated insulin signaling in skeletal muscle biopsies, reported a significant improvement in insulin action at both whole-body and cellular level [44].

Some reports also suggested an amelioration of general well-being and a reduction in the need for pharmacological therapy in these patients.

Adherence to protocols and the risk of dropout are key issues in evaluating the potential role of any strategies of physical activity. However, adherence was reported only in a minority of these RCTs, with different results (60–98%). Dropouts also varied, between 0 and 27%. Limited available information makes it difficult to analyze factors underlying these differences, which may include the selection of patients, motivation strategies, and logistic aspects.

Several of these papers also reported on different functional aspects, in particular changes in cardiorespiratory fitness, as measured by maximal or submaximal exercise tests. In most studies, cardiorespiratory fitness proved to be significantly increased after training (Table 2). Conversely, only a few studies investigated changes in muscular strength, with inconsistent findings.

The intensity of exercise varied among studies. In most protocols, it was moderate, in accordance with standard recommendations of international guidelines. An interesting small study assessed the effect of exercise at maximal fat oxidation, as determined in each individual by indirect calorimetry during a graded exercise test [55]. The corresponding intensity was mild–moderate, with a mean value of 37% of maximal aerobic capacity. However, total and visceral fat, fructosamine (as a short-term index of glucose control), OGTT glucose, serum lipids, and surrogate indices of insulin resistance significantly improved after 3 months of intervention.

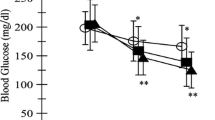

Some recent studies examined the effects of interval walking, which is an easily applicable form of high-intensity interval training. Karstoft et al., in a comprehensive study, compared the effects of continuous walking, at about 70% of maximal energy expenditure, with those of energy expenditure-matched interval walking and reported the results of a 4-month intervention in two distinct papers [43, 44]. In this study, as compared with changes in a non-exercise control group, the glucose daily profile, recorded by continuous glucose monitoring, and total and visceral fat, measured by MRI, decreased, whereas insulin sensitivity, measured by the hyperglycemic glucose clamp, and VO2 peak increased in the interval-walking group. Conversely, all these changes did not reach statistical significance in the continuous walking group.

Besides the medium-term differences between interval walking and continuous walking training, Karstoft et al. also compared some short-term effects of this protocol in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, glucose kinetics in the 4 h following a standardized mixed meal with glucose isotopic tracers, as well as glucose profiles in the 32 h following this test, were better after a single interval-walking session than after a continuous walking session [60]. Moreover, glucose effectiveness, measured during a hyperglycemic clamp, increased after 2 weeks of interval walking, but not continuous walking, before any improvement in insulin sensitivity had occurred [61]. This change was associated with reductions in mean and maximum glucose levels in the 24 h glucose monitoring, suggesting that the increase in glucose effectiveness may represent an additional mechanism by which exercise training improves glycemic control in subjects with T2DM. The same group also assessed whether repeated cycles of 1 min fast and 1 min slow walking may have different effects on post-prandial blood glucose, as compared with cycles of 3 min fast and 3 min slow walking, of equivalent whole duration and intensity [62]. However, both protocols of interval walking elicited similar improvements, as compared with a non-exercise day.

Another interesting paper compared continuous walking and interval walking, with progressively increasing but similar energy expenditure values between groups, vs a non-exercise control group [49]. In this study, after 12 weeks, body fat, leg strength, and estimated insulin sensitivity similarly improved in both exercise groups. However, VO2 peak and both endothelial and microvascular function improved to a greater extent in the interval-walking group, whereas HbA1c and indices of oxidative stress improved in the interval-walking group only.

More recently, another two studies investigated the effects of interval walking. In these protocols, which did not include a non-exercise group, results were compared with those of an active control group, in one case assigned to generic non-supervised brisk walking [63], in the other to a greater volume of a specified program of home-based continuous walking [64]. In the former study, HbA1c, BMI, and 6-min walk test distance showed similar improvements, vs baseline values, in both groups, whereas arterial stiffness significantly improved in the interval-walking group only. In the latter study, in which interval walking was supervised in the first 12 weeks and then home-based for 1 year, only effects on oxidative stress and inflammatory markers were reported, which were not statistically significant.

The efficacy of nordic walking, a technique that can potentially elicit higher metabolic and cardiovascular demands than natural walking, by engaging both legs and upper body, has been investigated by a couple of RCTs in diabetic patients [40, 41]. These studies were unable to show clear metabolic improvement. However, neither protocol was designed to obtain vigorous cardiovascular stimulation. In addition, these studies did not include a natural walking control group.

A few studies evaluated the efficacy of training when organized in supervised walking groups. These studies reported improved glucose control, either in the whole cohort [35] or in subjects with at least 50% adherence [52].

Other studies investigated the effects of the prescription of non-structured walking, using pedometers and targeting the absolute value of at least 10,000 steps per day vs standard care [65], or an increase of at least 3000 steps per day over baseline vs generic advice to engage in 30–60 min per day of any physical activity [66]. Both studies reported a statistically significant and clinically meaningful reduction of HbA1c in the walking groups vs controls, although only a small percentage of subjects had achieved the step goals (6–26%).

Finally, several short-term studies have investigated whether the timing of walking, in relation to meals, may be an important issue. Reynolds et al., in a randomized crossover trial, reported that post-prandial glucose, measured by continuous glucose monitoring for 1 week, was significantly lower when patients walked 10 min immediately after each main meal than 30 min on a single daily occasion, for 2 weeks. In this study, the improvement was greater after the evening meal, with a higher content of carbohydrates and generally characterized by more sedentary behavior [67]. A recent systematic review has investigated the relationship between exercise timing, relative to meal ingestion, and glucose control in patients with T2DM. This review concluded that there is some evidence from RCTs that exercise performed 30 min after meals may cause a greater improvement of glucose profiles in diabetic subjects. However, information is limited [68].

The conclusion that supervised walking is more effective than an unsupervised approach in these subjects is consistent with findings, showing that supervised exercise training was better than home-based exercise training in improving the quality of life and body composition, over 12 weeks, in women with T2DM [69]. However, in this study, home-based exercise therapy was also associated with a significant improvement in blood glucose, body composition, and serum lipids.

Walking has also been proposed as a simple stratagem for interrupting sedentary behavior. Prolonged sitting has major adverse effects on several health aspects, which are only partially reversed by regular structured exercise [70]. However, the interruption of prolonged sitting by short bouts of light physical activity may favorably affect these alterations. In this regard, some short-term studies have shown that short bouts of light walking, typically for 3 min every 30 min, reduced glucose and insulin levels and blood pressure, and improved post-prandial plasma lipidome and endothelial dysfunction in subjects with type 2 diabetes, as compared with values during continuous sitting [71,72,73,74,75]. Interestingly, the reduction of blood glucose was still observed in these patients the following morning [76]. No long-term RCTs are available on this issue, and they are urgently needed.

Assessment in diabetic patients undergoing walking prescription

A.Medical assessment Physical activity is beneficial and generally safe, but does carry some potential health risks in people with diabetes, including musculoskeletal injury, acute cardiovascular complications, and either hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Preliminary screening before starting any physical activity programs in subjects with diabetes mellitus should thus include a general medical examination, with a specific attention to symptoms and signs of chronic complications (cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, retinopathy, and/or neuropathy), and assessment of metabolic control [11]. In particular, when moderate-to-vigorous and/or prolonged walking programs are scheduled, it is imperative to assess the presence of osteoarticular alterations and micro- or macro-vascular complications. In this condition, medical clearance from a health care professional should be obtained before starting the training. This may require an exercise stress test or, in selected patients, more complex and invasive procedures, when cardiovascular disease is suspected and/or high-intensity exercise is programmed.

However, it has been suggested that standard recommendations may be too cautious in asymptomatic people already receiving appropriate diabetes care, in whom low–moderate-intensity exercise, such as brisk walking, is prescribed. Indeed, this approach can cause excessive physician referrals, hampering exercise participation. Moreover, while available screening tests have a low performance in identifying those patients at increased risk, the clinical benefits of a systematic search for silent ischemia in these patients, beyond standard care, remain unproven [77, 78].

Careful consideration of multiple factors and sound clinical judgment, based on individual medical history and physical examination, should estimate the risk of acute complications and identify the physical activities that should be avoided or limited. Indeed, individual clinical features, level of habitual physical activity, and intensity of planned exercise programs are key aspects that should be considered and guide a tailored medical screening, in particular as regards the assessment of exercise-related cardiovascular risk [79].

Current therapy is another relevant issue, as beta-blockers can affect the assessment of exercise intensity, and several antidiabetic medications, in particular insulin, sulphonylureas, and glinides, may interact with exercise, increasing risk of hypoglycemia during and after exercise sessions. Exercise-induced hypoglycemia is uncommon in people with type 2 diabetes, but it is possible and can be underestimated in subjects using insulin or insulin secretagogues. In particular, exercise-induced nocturnal hypoglycemia is a major concern. Hypoglycemic events occur typically within 6–15 h post-exercise, although risk can extend up to 48 h. In these subjects, blood glucose self-monitoring is helpful and should be considered. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring systems are now also available, although use in subjects with type 2 diabetes is still limited and performance may be lower when glucose levels change quickly, as frequently may occur during exercise. The risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia may be minimized through reductions of insulin or secretagogue drug dose before and after training.

The presence of peripheral neuropathy requires proper foot care, to prevent and to detect alterations in the early stages, before ulceration occurs. These patients must be instructed to examine their feet daily, and to detect and treat blisters, sores, or ulcers. However, in the presence of any foot deformity, physical activity programs should preferably focus on non weight-bearing activities, to avoid undue plantar pressure.

Vigorous aerobic exercise must be avoided in anyone with severe non proliferative or unstable proliferative diabetic retinopathy, as well as in those with severe autonomic neuropathy.

B. Functional assessment Evaluation of walking capacity is of paramount importance in clinical settings, as it identifies possible individual impairments and assists in guiding therapeutic interventions. Traditionally, walking capacity assessment encompasses either short-distance measures of walking speed or timed measures of walking distance. Walking speed (e.g., the 10-m walk test) is usually regarded as a proxy for lower limb function and has been linked to several functional and health indicators [80, 81]. Conversely, walking distance is a more general indicator of overall physical performance and mobility, used in both healthy adults [82] and individuals with T2DM [83]. Walking distance is generally assessed by the 6-min walk test, which has been validated in diabetic subjects [83] and predicts their functional ability to walk [84]. This test entails measurement of distance walked over a time span of 6 min and is preferably performed indoors, along a ~ 30 m in length, flat, straight, enclosed corridor with a hard surface. The length of the corridor is marked every 3 m and the turnaround points are indicated. A practice test is not needed in most circumstances, but can be considered [85]. In healthy adults, the median 6-min walk test distance was 580 m for men and 500 m for women [86]; these values, however, may vary according to the examined population and the technical characteristics of the test. Interestingly, the 6-min walk test was found to be predictive of cardiorespiratory status and particularly heart rate (HR) at individual ventilatory threshold in obese adults. These findings suggest that it may also be useful for prescribing optimal walking ‘doses’, when gold standard methods (e.g., gas-exchange analysis) are unavailable [87].

Walking prescription

Walking is the activity of choice for most diabetic patients [88], while being effective in promoting weight loss and maintenance, and in improving glycemic control [31]. However, to obtain valuable benefits from a walking-based exercise training, adequate amounts of walking should be performed. Diabetic patients should engage in a minimum of 30 min/day of physical activity, undertaken at moderate or greater intensity. This activity should ideally last at least 10 min and be spread throughout the week [1]. For most individuals with type 2 diabetes engaging in a walking-based exercise training, the sustainable intensity between 40 and 59% heart rate reserve (HRR, calculated as a percentage of maximum heart rate minus resting heart rate), corresponding to a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) of 11–13 on a 6–20 scale [89] (Table 3) should be encouraged, even if lower intensities should be initially prescribed for very deconditioned patients. Unfortunately, exercise intensity is rarely prescribed on an individual basis, although some studies have recently argued for the use of tailored approaches, with a particular emphasis on the individual ventilatory threshold [90, 91], to improve cardiorespiratory fitness and promote weight loss and maintenance. Further studies are still required to confirm that the individual ventilatory threshold may be an appropriate guide in prescribing exercise intensity in these patients.

As the exercise program progresses and the individual is able to better tolerate the walking session, higher intensity bouts, above the 60%HRR, could be prescribed [1, 92]. Blood glucose control may be further improved at higher exercise intensities [93], and exercise protocols alternating between periods of vigorous activity (i.e., > 60%HRR) and periods of rest or recovery, termed “high-intensity interval training” (HIIT), can be considered. Hence, individuals with T2DM may consider raising the intensity to elicit higher levels of physical exertion. Patients who wish to perform HIIT should be clinically stable, have been participating at least in regular moderate-intensity exercise, and should be supervised at least initially. The risks with advanced disease are unclear, and continuous, moderate-intensity exercise may be safer.

However, prescription of vigorous-intensity activities may be a contributing factor to non-adherence to exercise programs. Considerable evidence exists that people are more likely to adhere to low-intensity activities than high-intensity activities [94, 95]. Thus, physicians are not encouraged to “push up” all of their diabetic patients, to avoid risking exercise dropout. Also for this reason, tailored intervention is required.

It must be considered that most subjects with type 2 diabetes [96] withdraw from exercise programs before physiological gains occur, and the reasons for the low rates of exercise adherence are still uncertain. Some authors have proposed that this phenomenon might be mediated by the amount of pleasure that individuals experience during exercise [97]. In this regard, some studies have reported that subjects’ preferred walking intensities are more pleasurable than strictly prescribed walking intensities for most sedentary adults, resulting in better exercise adherence [98, 99]. However, self-paced protocols, where individuals are encouraged to choose their walking speed, must be reinforced by physicians to ensure a more positive affective response during exercise, which in turn may prevent dropout. Interestingly, self-paced protocols may also promote fitness and health benefits and minimize or possibly prevent weight gain [100]. Additionally, self-paced walking performed in naturalistic settings may elicit more pleasurable feelings than self-paced walking performed in a clinical setting [101]. Thus, physicians should focus not only on physiological but also on behavioral prescriptions to ensure exercise adherence in diabetic patients.

Some diabetic patients have pre-existing clinical conditions that could prevent certain modes of activities such as walking. These conditions are often related to pain induced by diabetic neuropathy and, in some cases, gait and/or balance disturbances that may be chronic [102]. In this scenario, activities, such as stationary cycling, recumbent cycling, or water activities, should be selected.

Walking session management

Walking prescription must include, as any other exercise bout, some important advice regarding the approach to movement and environmental conditions:

-

Warm up: before the beginning of a walking session, some stretching exercises for both upper and lower limbs are useful as preparation for appropriate joint range movements;

-

Shoes and clothing: the choice of shoes and clothing for walking must be appropriate for both comfort and safety, suited to the terrain, and season;

-

Extreme conditions: there are no specific limitations for walking in diabetic patients. General health considerations relating to extreme temperatures, especially when associated to wind or humidity, are also valid for these patients. However, additional caution is necessary for subjects presenting cardiovascular impairments. High or low temperatures produce an increase in metabolic requirements at a certain walking intensity, and a general reduction of speed and distance should be suggested.

Notably, metabolic and biomechanical requirements of walking are highly dependent on several factors. Studies on human locomotion have suggested that spontaneous walking speed corresponds to that minimizing energy expenditure per unit of space traveled. The cost of locomotion begins to increase both above and below this speed [103]. Another factor that has significant influence on the cost of locomotion, and, therefore, on physical exertion, is gradient, with a walking uphill or downhill slope greater than ± 10% requiring more energy than walking on the flat [104, 105]. Changes in speed or incline also affect biomechanical parameters of walking. In particular, walking faster or downhill was seen to increase the ground reaction forces and the loading rate at heel strike with respect to walking on the flat.

The condition of the terrain may also influence the cost of locomotion; for example, walking on either sand [106] or snow [107] increases the cost of locomotion with respect to walking on a hard surface, to an extent that largely depends on the specific conditions. Similarly, walking in water results in a significant increase of energy expenditure, which depends on water depth [108].

Deliberate modification of walking patterns can be of interest in physical activity programs. The use of walking poles, called Nordic Walking when performed following a specific pattern involving the diagonal use of poles suggested by INWA (International Nordic Walking Association), typically increases the cost of locomotion by 20–25% with respect to conventional walking [109, 110]. This increase is, however, largely affected by the proficiency of the technique adopted [111] and may further increase when people improve their skill [110]. Walking with poles is becoming more and more popular not only for its superior energy expenditure with respect to the conventional walking, but also because of the lower perception of effort [110]. From both a muscular and biomechanical point of view, walking with poles engages the upper body musculature, especially targeting arm joint extensors, and despite there being no agreement on the effect of joint loading, it may also improve the dynamic balance of locomotion [112]. Physical activity programs based on Nordic Walking were found to improve exercise capacity, functional status, quality-of-life cardiorespiratory outcomes, and lipid profile, also reducing body weight and chronic pain [113, 114]. On the other hand, the effects on muscle strength are less clear [113, 114].

It should be noted that although walking is a natural motor pattern in humans, walking on a treadmill or using poles requires suitable learning, to obtain the best results and to avoid injuries. This is even more relevant in patients suffering from a long period (i.e., months/years) of inactivity or muscle weakness, in older people or in those with severe obesity. A first period, lasting 2–4 weeks, including appropriate training and a positive educational approach will lead to a better walking pattern, fully adapted to the different terrain situation or to the correct use of a motorized treadmill. However, when Nordic walking is considered, the need for training becomes even more important and the teacher qualification is of particular importance. In this case, the learning period should last from 12 to 16 sessions, depending on the patient’s personal attitude and motivation [111].

The correct walking or Nordic walking techniques also affect the energy cost of locomotion [115], which, in many cases, can limit the total distance covered by the patient during an exercise session, but also her/his quality of life, when reduced walking capacity hinders social relationships.

Monitoring of walking

Monitoring the level of effort and the functional response during walking is essential to assessing the effectiveness of prescribed exercise, and to preventing or minimizing the potential side effects. Functional body reaction, mechanical work, and perceived intensity are the three domains that should be taken into consideration. The involvement of the cardiovascular system can be easily evaluated through HR, which is the most effective parameter available to monitor continuously the amount of effort. Wearable HR monitors have been developed in the last decades and they are now precise, reliable and relatively cheap. Several models are currently available and many of them can integrate different parameters (e.g., body movements and environment data) with HR, or can offer elaborations of the recorded HR values (HR zones, variability, etc.). While a simple HR monitor can be sufficient to assess the level of cardiac involvement, the possibility of recording several walking sessions is a valuable additional function, which allows the patient to quantify the global amount of exercise performed in a given period.

Interestingly, recent technologies are also able to measure and record several aspects of the body movement, including speed, distance, and walking route. Step counting with a pedometer or more accurate evaluations of body acceleration are widely used to measure the amount of walking [116]. In particular, a very accurate record of the walking route can be obtained using GPS technology, recently integrated in the more advanced HR monitors. This function gives a detailed analysis of outdoor activities, including walking, although it is still quite expensive and usually exceeds monitoring requirements in most patients.

The perception of effort as a methodology to assess the intensity of the exercise performed has been well known since the beginning of exercise physiology studies, and it was substantially developed by Gunnar Borg in the late 1970s [117]. It has become very popular in the last few years as a simple and cheap system to monitor training in different settings. The use of ratings of perceived effort has been validated also in diabetic subjects with autonomic neuropathy [118], and is considered a valid tool for monitoring walking in subjects with type 2 diabetes, integrated with HR or even alone, when HR recording is difficult or unreliable.

Regular aerobic exercise produces favorable long-term cardiovascular adaptations in diabetic patients. However, our knowledge about the acute effect of exercise on blood pressure in these subjects is limited, and results are inconsistent. A recent study showed that walking at moderate speed acutely induces a small increase in blood pressure, followed by a rapid reduction in resting pressure and stiffness after the exercise session [119]. Nevertheless, an exaggerated blood pressure response has been described in subjects with metabolic syndrome, which were characterized by insulin resistance and altered autonomic regulation [120]. This suggests the need to pay a special attention to the blood pressure response during the walking sessions, especially in obese and hypertensive patients.

Special conditions

Patients with T2DM may have comorbid conditions, requiring a special attention in tailoring walking prescription [79, 121]. In particular, many diabetic individuals are obese and/or are at high risk for or have CVD or heart failure. In particular, the vast majority of T2DM individuals are overweight or obese and many of them have severe obesity. Nevertheless, also for these subjects, lifestyle changes are fundamental, aiming to accomplish both glucose control and weight reduction. The younger obese patients may respond better to physical training, probably due to the greater muscle strength. However, while for obese subjects with T2DM of any age, walking is a feasible form of exercise, some specific advice should also be considered, such as reducing speed, avoiding positive or negative slopes exceeding 5%, introducing appropriate recovery after each 15 min of exercise. Interestingly, in these patients, Nordic walking could often be a more efficient type of walking, because, if using a correct technique, it produces a larger amount of energy expenditure and a lower charge on the lower limb joints, for a similar amount of time spent in exercise.

Patients with T2DM have rates of heart failure, angina pectoris, re-infarction disability, and sudden cardiac death that are at least twice those observed in non-diabetic patients [122]. However, these risks do not represent an absolute restriction for walking, as this activity represents the easiest type of exercise for these patients [121]. Nevertheless, patients with coronary heart disease or heart failure must perform properly designed and supervised exercise training [123, 124].

Elevated body mass is linked to both diabetes and incident heart failure. The greater the elevation in body mass, the greater the risk, the worse the clinical outcomes and often the more severe the associated symptoms and signs, such as exertional dyspnea and ankle edema. Indeed, these clinical features are more marked in obese patients with heart failure, and represent an indication to restrict walking speed and duration, in comparison to the standard prescription. In these cases, accurate monitoring of heart rate response can also represent a safety tool, to avoid or reduce potential adverse events during effort.

Although regular physical activity improves metabolic abnormalities in obese patients with diabetes, it remains to be established whether exercise training is able to reduce the cardiovascular risk in these subjects. The Look AHEAD trial did not show significant reductions in cardiovascular disease incidence in adults with T2DM assigned to an intensive lifestyle intervention, as compared with those assigned to standard care [26]. However, a post hoc analysis of these data suggested an association between the magnitude of weight loss and incidence of cardiovascular disease [125]. Moreover, in this post hoc analysis, achieving an increase of at least two metabolic equivalents in fitness was associated with a significant reduction in the secondary outcome of the study, which was a composite of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease, total mortality, carotid or peripheral vascular disease, and hospitalization for congestive heart failure [125].

Panel conclusions: final statements and recommendations

(Symbols indicate the strength of a statement and the quality of the underlying evidence, as described in the Methods).

-

1.

Walking improves glucose control in people with T2DM and should be recommended, as a form of aerobic exercise training, in most diabetic individuals.

1 ØØØO

This recommendation is supported by the results of a meta-analysis, including many small, short-term RCTs, and some recent additional studies, showing clinically significant improvement of HbA1c. The effect on insulin resistance is less clear. Walking does not require expertise and logistic support, can be performed in different places, and is easily applicable in daily life in most patients.

-

2.

Walking can be suggested for the therapy of several alterations associated with T2DM.

2 ØØOO

Regular walking favors slight reductions of body weight and blood pressure. However, substantial weight loss requires multidimensional interventions, with specific attention to diet. A few RCTs also suggested an amelioration of general well-being and a reduction in the need for pharmacological therapy in these patients.

-

3.

Walking improves functional capacity of subjects with T2DM.

1 ØØOO

In most RCTs cardiorespiratory fitness proved to be significantly increased after walking training. Conversely, information on changes in muscular strength is limited, with inconsistent findings.

-

4.

Walking could have favorable effects on chronic complications of diabetes.

2 ØOOO

Limited information indicates improvement of several alterations involved in the increased cardiovascular risk associated with diabetes. Moreover, a small study reported favorable changes in several functional aspects of diabetic neuropathy, although the presence of this condition requires specific attention, monitoring of patients, and may also limit walking activities.

-

5.

Supervised walking training is preferable, whenever possible, in diabetic patients.

1 ØØØO

Evidence of efficacy is more consistent in protocols based on supervised walking. This may be linked to the observation that diabetic patients may walk spontaneously at lower velocity than non-diabetic people, likely due to impaired exercise capacity.

-

6.

Unsupervised walking may also be effective in these patients, especially when combined with motivational strategies.

2 ØØOO

Findings on the effects of unsupervised interventions on long-term blood glucose control are less clear. However, motivational strategies may improve adherence and beneficial effects of exercise.

-

7.

Interval training can be prescribed in diabetic subjects, especially in younger and more physically fit individuals.

1 ØØOO

Interval training, alternating either 1 min fast and 1 min slow or 3 min fast and 3 min slow walking, can improve several clinical features, including glucose control and cardiorespiratory fitness, to a greater extent than continuous walking. It represents a valuable alternative to continuous training in subjects who do not show specific contraindications.

-

8.

Nordic walking may have additional advantages as compared with walking in these subjects.

2 ØOOO

Nordic walking may elicit higher metabolic and cardiovascular demands than natural walking, by engaging both legs and upper body. However, evidence-based information on the effects of this training in diabetic people is still very limited.

-

9.

Walking surface and slope affect cost of locomotion and should be carefully considered in exercise prescription.

1 ØØØO

Walking on sand or snow, or in water, induces a significant increase of energy expenditure as compared with walking on a hard surface. Similarly, walking uphill or downhill slope increases energy expenditure as compared with walking on flat. Changes in speed or incline also affect biomechanical parameters of walking. These may be relevant aspects when prescribing exercise in many diabetic patients.

-

10.

Timing of walking could be considered in exercise prescription.

2 ØØOO

Limited information suggests that walking may lower post-prandial increases of blood glucose and glucose variability to a greater extent when exercise is performed just before or after meals. This may also affect interaction between exercise and some antidiabetic medications.

-

11.

Short bouts of walking for breaking prolonged sedentary time have favorable effect of blood glucose profiles in diabetic people and should be recommended, whenever possible, in all sedentary individuals, besides exercise prescription.

1 ØØOO

A few RCTs consistently showed improved blood glucose profiles after interruption of prolonged sitting in T2DM, e.g., 3 min every 30 min, and this effect was maintained for several hours. However, evidence is still short term.

-

12.

Prescription of walking in T2DM patients should be preceded by a tailored medical and functional assessment.

1 ØØØØ

Assessment of risks and functional capacity is mandatory before exercise prescription. Medical clearance from a health care professional should be obtained before starting the training, with specific attention to chronic diabetes complications and therapy. However, an exercise stress test is not generally required in asymptomatic people receiving appropriate diabetes care, in whom moderate-intensity exercise, such as brisk walking, is prescribed. The 6-min walk test may be used for assessing and monitoring walking capacity.

References

Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, Riddell MC, Dunstan DW, Dempsey PC et al (2016) Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 39:2065–2079

Zanuso S, Jimenez A, Pugliese G, Corigliano G, Balducci S (2010) Exercise for the management of type 2 diabetes: a review of the evidence. Acta Diabetol 47:15–22

Balducci S, Sacchetti M, Haxhi J, Orlando G, D'Errico V, Fallucca S et al (2014) Physical exercise as therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 30(Suppl 1):13–23

Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Zucatti AT, Azevedo MJ et al (2011) Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 305:1790–1799

Bacchi E, Negri C, Zanolin ME, Milanese C, Faccioli N, Trombetta M et al (2012) Metabolic effects of aerobic training and resistance training in type 2 diabetic subjects: a randomized controlled trial (the RAED2 study). Diabetes Care 35:676–682

Bacchi E, Negri C, Targher G, Faccioli N, Lanza M, Zoppini G et al (2013) Both resistance training and aerobic training reduce hepatic fat content in type 2 diabetic subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (the RAED2 Randomized Trial). Hepatology 58:1287–1295

Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boulé NG, Wells GA, Prud'homme D, Fortier M et al (2007) Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 147:357–369

Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S, Johannsen N, Johnson W, Kramer K et al (2010) Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 304:2253–2262

Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ et al (2012) Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 55:2895–2905

Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS et al (2015) Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 162:123–132

American Diabetes Association (2020) Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 43(Supplement 1):S48–S65

Fagour C, Gonzalez C, Pezzino S, Florenty S, Rosette-Narece M, Gin H et al (2013) Low physical activity in patients with type 2 diabetes: the role of obesity. Diabetes Metab 39:85–87

Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Ghushchyan V, Sullivan PW (2007) Physical activity in US adults with diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes. Diabetes Care 30:203–209

Resnick HE, Foster GL, Bardsley J, Ratner RE (2006) Achievement of American Diabetes Association clinical practice recommendations among US adults with diabetes, 1999–2002: the National Health and Nutritio Examination Survey. Diabetes Care 29:531–537

Mu L, Cohen AJ, Mukamal KJ (2014) Resistance and aerobic exercise among adults with diabetes in the US. Diabetes Care 37:e175–176

Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, Hagströmer M, Craig CL, Bull FC et al (2011) The descriptive epidemiology of sitting. A 20-country comparison using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Am J Prev Med 41:228–235

Balducci S, D'Errico V, Haxhi J, Sacchetti M, Orlando G, Cardelli P et al (2017) Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study 2 (IDES_2) Investigators. Level and correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional analysis of the Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study_2. PLoS ONE 12(3):e0173337

Hajna S, Ross NA, Joseph L, Harper S, Dasgupta K (2016) Neighbourhood walkability and daily steps in adults with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0151544

Regensteiner JG, Sippel JM, McFarling E, Wolfel EE, Hiatt WR (1995) Effects of non-insulin-dependent diabetes on oxygen consumption during treadmill exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 127:661–667

Boulé NG, Kenny GP, Haddad E, Wells GA, Sigal RJ (2003) Meta-analysis of the effect of structured exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 46:1071–1081

Petrovic M, Deschamps K, Verschueren SM, Bowling FL, Maganaris CN, Boulton AJM et al (2016) Is the metabolic cost of walking higher in people with diabetes? J Appl Physiol 120:55–62

Johnson ST, Tudor-Locke C, McCargar LJ, Bell RC (2005) Measuring habitual walking speed of people with type 2 diabetes: are they meeting recommendations? Diabetes Care 28:1503–1504

Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Laitinen JH (2009) Barriers to regular exercise among adults at high risk or diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Promot Int 24:416–427

Di Loreto C, Fanelli C, Lucidi P, Murdolo G, De Cicco A, Parlanti N et al (2005) Make your diabetic patients walk: long-term impact of different amounts of physical activity on type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:1295–1302

Balducci S, D'Errico V, Haxhi J, Sacchetti M, Orlando G, Cardelli P, Italian Diabetes, and Exercise Study 2(IDES-2) Investigators et al (2019) Effect of a behavioral intervention strategy on sustained change in physical activity and sedentary behavior in patients with type 2 diabetes: the IDES_2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321:880–890

Look AHEAD Research Group, Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M et al (2013) Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 369:145–154

Henson J, Davies MJ, Bodicoat DH, Edwardson CL, Gill JM, Stensel DJ et al (2016) Breaking up prolonged sitting with standing or walking attenuates the postprandial metabolic response in postmenopausal women: a randomized acute study. Diabetes Care 39:130–138

Hays LM, Clark DO (1999) Correlates of physical activity in a sample of older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 22:706–712

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, GRADE Working Group et al (2004) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 328(7454):1490

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Sterne JA, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group, and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group (2011) Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, London

Qiu S, Cai X, Schumann U, Velders M, Sun Z, Steinacker JM (2014) Impact of walking on glycemic control and other cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9(10):e109767

Abd El-Kader SM, Al-Jiffri OH, Al-Shreef FM (2015) Aerobic exercises alleviate symptoms of fatigue related to inflammatory cytokines in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Afr Health Sci 15:1142–1148

Akbarinia A, Kargarfard M, Naderi M (2018) Aerobic training improves platelet function in type 2 diabetic patients: role of microRNA-130a and GPIIb. Acta Diabetol 55:893–899

Arora E, Shenoy S, Sandhu JS (2009) Effects of resistance training on metabolic profile of adults with type 2 diabetes. Indian J Med Res 129:515–519

Belli T, Ribeiro LFP, Ackermann MA, Baldissera V, Gobatto CA, da Silva RG (2011) Effects of 12-week overground walking training at ventilatory threshold velocity in type 2 diabetic women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 93:337–343

Dixit S, Maiya AG, Shastry BA (2014) Effect of aerobic exercise on peripheral nerve functions of population with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes: a single blind, parallel group randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Complicat 28:332–339

Dixit S, Maiya A, Shastry BA, Guddattu V (2016) Analysis of postural control during quiet standing in a population with diabetic peripheral neuropathy undergoing moderate intensity aerobic exercise training: a single blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 95:516–524

Dixit S, Maiya A, Shastry BA (2017) Effect of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on glycosylated haemoglobin among elderly patients with type 2 diabetes and peripheral neuropathy. Indian J Med Res 145:129–132

Dixit S, Maiya A, Shastry BA (2019) Effects of aerobic exercise on vibration perception threshold in type 2 diabetic peripheral neuropathy population using 3-sites method: single-blind randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med 25:36–41

Fritz T, Caidahl K, Krook A, Lundström P, Mashili F, Osler M et al (2013) Effects of Nordic walking on cardiovascular risk factors in overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes, impaired or normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 29:25–32

Gram B, Christensen R, Christiansen C, Gram J (2010) Effects of nordic walking and exercise in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med 20:355–361

Kaplan RM, Wilson DK, Hartwell SL, Merino KL, Wallace JP (1985) Prospective evaluation of HDL cholesterol changes after diet and physical conditioning programs for patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 8:343–348

Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, Nielsen JS, Thomsen C, Pedersen BK et al (2013) The effects of free-living interval-walking training on glycemic control, body composition, and physical fitness in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 36:228–236

Karstoft K, Winding K, Knudsen SH, James NG, Scheel MM, Olesen J et al (2014) Mechanisms behind the superior effects of interval vs continuous training on glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 57:2081–2093

Koo BK, Han KA, Ahn HJ, Jung JY, Kim HC, Min KW (2010) The effects of total energy expenditure from all levels of physical activity vs physical activity energy expenditure from moderate-to-vigorous activity on visceral fat and insulin sensitivity in obese type 2 diabetic women. Diabet Med 27:1088–1092

Ku YH, Han KA, Ahn H, Kwon H, Koo BK, Kim HC et al (2010) Resistance exercise did not alter intramuscular adipose tissue but reduced retinol-binding protein-4 concentration in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Int Med Res 38:782–791

Kurban S, Mehmetoglu I, Yerlikaya HF, Gonen S, Erdem S (2011) Effect of chronic regular exercise on serum ischemia-modified albumin levels and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Res 36:116–123

Kwon HR, Min KW, Ahn HJ, Seok HG, Koo BK, Kim HC et al (2010) Effects of aerobic exercise on abdominal fat, thigh muscle mass and muscle strength in type 2 diabetic subject. Korean Diabetes J 34:23–31

Mitranun W, Deerochanawong C, Tanaka H, Suksom D (2014) Continuous vs interval training on glycemic control and macro- and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports 24:e69–76

Moghadasi M, Mohebbi H, Rahmani-Nia F, Hassan-Nia S, Noroozi H (2013) Effects of short-term lifestyle activity modification on adiponectin mRNA expression and plasma concentrations. Eur J Sport Sci 13:378–385

Motahari-Tabari N, Ahmad Shirvani M, Shirzad-E-Ahoodashty M, Yousefi-Abdolmaleki E, Teimourzadeh M (2014) The effect of 8 weeks aerobic exercise on insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Glob J Health Sci 7:115–121

Negri C, Bacchi E, Morgante S, Soave D, Marques A, Menghini E et al (2010) Supervised walking groups to increase physical activity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 33:2333–2335

Shenoy S, Guglani R, Sandhu JS (2010) Effectiveness of an aerobic walking program using heart rate monitor and pedometer on the parameters of diabetes control in Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes 4:41–45

Sung K, Bae S (2012) Effects of a regular walking exercise program on behavioral and biochemical aspects in elderly people with type II diabetes. Nurs Health Sci 14:438–445

Tan S, Du P, Zhao W, Pang J, Wang J (2018) Exercise training at maximal fat oxidation intensity for older women with type 2 diabetes. Int J Sports Med 39:374–381

Ur Rehman SS, Karimi H, Gillani SA, Ahmad S (2017) Effects of supervised structured aerobic exercise training programme on level of Exertion, dyspnoea, VO2 max and Body Mass Index in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pak Med Assoc 67:1670–1673

Karimi H, Rehman SSU, Gillani SA (2017) Effects of supervised structured aerobic exercise training program on interleukin-6, nitric oxide synthase-1, and cyclooxygenase-2 in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 27:352–355

van Rooijen AJ, Rheeder P, Eales CJ, Becker PJ (2004) Effect of exercise versus relaxation on haemoglobin A(1C) in Black females with type 2 diabetes mellitus. QJM 97:343–351

Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Goldhaber-Fiebert SN, Tristan ML, Nathan DM (2003) Randomized controlled community-based nutrition and exercise intervention improves glycemia and cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetic patients in rural Costa Rica. Diabetes Care 26:24–29

Karstoft K, Christensen CS, Pedersen BK, Solomon TP (2014) The acute effects of interval- vs continuous-walking exercise on glycemic control in subjects with type 2 diabetes: a crossover, controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:3334–3342

Karstoft K, Clark MA, Jakobsen I, Knudsen SH, van Hall G, Pedersen BK et al (2017) Glucose effectiveness, but not insulin sensitivity, is improved after short-term interval training in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a controlled, randomised, crossover trial. Diabetologia 60:2432–2442

Jakobsen I, Solomon TP, Karstoft K (2016) The acute effects of interval-type exercise on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes subjects: importance of interval length. A controlled, counterbalanced, crossover study. PLoS ONE 11(10):e0163562

Bellia A, Iellamo F, De Carli E, Andreadi A, Padua E, Lombardo M et al (2017) Exercise individualized by TRIMPi method reduces arterial stiffness in early onset type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized controlled trial with aerobic interval training. Int J Cardiol 248:314–319

Mallard AR, Hollekim-Strand SM, Coombes JS, Ingul CB (2017) Exercise intensity, redox homeostasis and inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Sci Med Sport 20:893–898

Fayehun AF, Olowookere OO, Ogunbode AM, Adetunji AA, Esan A (2018) Walking prescription of 10 000 steps per day in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised trial in Nigerian general practice. Br J Gen Pract 68(667):e139–e145

Dasgupta K, Rosenberg E, Joseph L, Cooke AB, Trudeau L, Bacon SL, SMARTER Trial Group et al (2017) Physician step prescription and monitoring to improve ARTERial health (SMARTER): a randomized controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Obes Metab 19:695–704

Reynolds AN, Mann JI, Williams S, Venn BJ (2016) Advice to walk after meals is more effective for lowering postprandial glycaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus than advice that does not specify timing: a randomised crossover study. Diabetologia 59:2572–2578

Teo SYM, Kanaley JA, Guelfi KJ, Cook SB, Hebert JJ, Forrest MRL et al (2018) Exercise timing in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50:2387–2397

Dadgostar H, Firouzinezhad S, Ansari M, Younespour S, Mahmoudpour A, Khamseh ME (2016) Supervised group-exercise therapy versus home-based exercise therapy: their effects on quality of life and cardiovascular risk factors in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr 10:S30–S36

Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE et al (2016) Lancet physical activity series 2 Executive Committe; Lancet Sedentary Behaviour Working Group: does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 388:1302–1310

Dempsey PC, Larsen RN, Sethi P, Sacre JW, Straznicky NE, Cohen ND et al (2016) Benefits for type 2 diabetes of interrupting prolonged sitting with brief bouts of light walking or simple resistance activities. Diabetes Care 39:964–972

Dempsey PC, Sacre JW, Larsen RN, Straznicky NE, Sethi P, Cohen ND et al (2016) Interrupting prolonged sitting with brief bouts of light walking or simple resistance activities reduces resting blood pressure and plasma noradrenaline in type 2 diabetes. J Hypertens 34:2376–2382

Grace MS, Dempsey PC, Sethi P, Mundra PA, Mellett NA, Weir JM et al (2017) Breaking up prolonged sitting alters the postprandial plasma lipidomic profile of adults with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:1991–1999

Duvivier BM, Schaper NC, Hesselink MK, van Kan L, Stienen N, Winkens B et al (2017) Breaking sitting with light activities vs structured exercise: a randomised crossover study demonstrating benefits for glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 60:490–498

Duvivier BMFM, Bolijn JE, Koster A, Schalkwijk CG, Savelberg HHCM, Schaper NC (2018) Reducing sitting time versus adding exercise: differential effects on biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and metabolic risk. Sci Rep 8(1):8657

Dempsey PC, Blankenship JM, Larsen RN, Sacre JW, Sethi P, Straznicky NE et al (2017) Interrupting prolonged sitting in type 2 diabetes: nocturnal persistence of improved glycaemic control. Diabetologia 60:499–507

Lièvre MM, Moulin P, Thivolet C, Rodier M, Rigalleau V, Penfornis A, DYNAMIT investigators et al (2011) Detection of silent myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic patients with diabetes: results of a randomized trial and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of systematic screening. Trials 12:23

Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, Davey JA, Barrett EJ, Taillefer R, DIAD Investigators et al (2009) Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301:1547–1555

Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, Garber CE, Whitfield GP, Magal M et al (2015) Updating ACSM's recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Med Sci Sports Exerc 47:2473–2479

Graham JE, Ostir GV, Fisher SR, Ottenbacher KJ (2008) Assessing walking speed in clinical research: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 14:552–562

van Kan GA, Rolland Y, Andrieu S, Bauer J, Beauchet O, Bonnefoy M et al (2009) Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an international academy on nutrition and aging (Iana) task force. J Nutr Health Aging 13:881–889

Solway S, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, Thomas S (2001) A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 119:256–270

Lee MC (2018) Validity of the 6-minute walk test and step test for evaluation of cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Exerc Nutr Biochem 22:49–55

Nolen-Doerr E, Crick K, Saha C, de Groot M, Pillay Y, Shubrook JH et al (2018) Six-minute walk test as a predictive measure of exercise capacity in adults with type 2 diabetes. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 29:124–129

Miyamoto S, Nagaya N, Satoh T, Kyotani S, Sakamaki F, Fujita M et al (2000) Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161:487–492

ATS Committee on proficiency standards for clinical pulmonary function laboratories (2002) ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:111–117

Emerenziani GP, Ferrari D, Vaccaro MG, Gallotta MC, Migliaccio S, Lenzi A et al (2018) Prediction equation to estimate heart rate at individual ventilatory threshold in female and male obese adults. PLoS ONE 13:e0197255

Ford ES, Herman WH (1995) Leisure-time physical activity patterns in the US diabetic population. Findings from the 1990 National Health interview survey-health promotion and disease prevention supplement. Diabetes Care 18:27–33

American College of Sports Medicine (2014) ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Emerenziani GP, Gallotta MC, Migliaccio S, Greco EA, Marocco C, di Lazzaro L et al (2016) Differences in ventilatory threshold for exercise prescription in outpatient diabetic and sarcopenic obese subjects. Int J Endocrinol 2016:6739150

Emerenziani GP, Ferrari D, Marocco C, Greco EA, Migliaccio S, Lenzi A et al (2019) Relationship between individual ventilatory threshold and maximal fat oxidation (MFO) over different obesity classes in women. PLoS ONE 14:e0215307

Francois ME, Little JP (2015) Effectiveness and safety of high-intensity interval training in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr 28:39–44

Jelleyman C, Yates T, O'Donovan G, Gray LJ, King JA, Khunti K et al (2015) The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 16:942–961

Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Fortmann SP, Vranizan KM, Taylor CB, Solomon DS (1986) Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample. Prev Med 15:331–341

Perri MG, Anton SD, Durning PE, Ketterson TU, Sydeman SJ, Berlant NE et al (2002) Adherence to exercise prescriptions: effects of prescribing moderate versus higher levels of intensity and frequency. Health Psychol 21:452–458

Nam S, Dobrosielski DA, Stewart KJ (2012) Predictors of exercise intervention dropout in sedentary individuals with type 2 diabetes. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 32:370–378

DaSilva SG, Elsangedy HM, Krinski K, De Campos W, Buzzachera CF, Krause MP et al (2011) Effect of body mass index on affect at intensities spanning the ventilatory threshold. Percept Mot Skills 113:575–588

Ekkekakis P, Lind E (2006) Exercise does not feel the same when you are overweight: the impact of self-selected and imposed intensity on affect and exertion. Int J Obes 30:652–660

Guidetti L, Buzzachera CF, DaSilva SG, Baldari C (2010) Is exercise at a self-selected pace able to promote benefits in cardiorespiratory fitness and psychological responses? In: Azoia N, Dobreiro P (eds) Treadmill exercise and its effects on cardiovascular fitness, depression, and muscle aerobic function, 1st edn. Nova Science Publishers, New York

DaSilva SG, Guidetti L, Buzzachera CF, Elsangedy HM, Krinski K, Campos W et al (2011) Gender-based differences in substrate use during exercise at a self-selected pace. J Strength Cond Res 25:2544–2551