Abstract

This paper detects valuable research findings at the intersection of socioemotional wealth and strategic decision-making processes. While socioemotional wealth is a key construct in research on family firms, strategic management represents a foundational approach to strategic management processes. The systematic literature review identifies from an extensive sample, a final set of 169 journal articles using a multistep methodology. We perform an in-depth content analysis that highlights the overlap between socioemotional wealth and strategic management. One field of strategic management, namely Analysis & Forecast, offers particular potential for further research. Hence, we create construct clarity by developing five aggregated categories. These categories act as dimensions of an integrative framework with strategic analysis activities. The literature review leads to the conclusion that in previous research, each socioemotional wealth dimension influences every analysis activity but one at a time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Family businesses account for 70–90% of all corporations worldwide (Zellweger 2017) and affect economies tremendously (Pieper et al. 2022). However, there is neither a uniform definition (Cano-Rubio et al. 2017) nor any formal criteria for determining the nature of family businesses. Hence, a distinction requires qualitative considerations (Heider 2017; Simon 2012), whereas the degree and instruments of family control and their influence on businesses are crucial. In addition to financial (economic) motives, familial (noneconomic) motives play a central role in the target system of a family business. Moreover, financial and nonfinancial goals can be contradictory (Astrachan and Jaskiewicz 2008) and lead to a decision-making dilemma. In particular, family businesses make economic decisions following their rationality (Certo et al. 2008; Tversky and Kahnemann 1981). These family goals have strong emotional importance as the boundaries between family and business become blurred (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011).

Nonfinancial goals shape strategic decisions in family businesses (Debicki et al. 2016; Felden et al. 2019; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011). Nonfinancial considerations, such as business relationships, family values, or other emotional motives (De Massis et al. 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011; Kotlar et al. 2018; Neumann 2017; Zellweger et al. 2019), influence strategic management in a family business (Felden et al. 2019; Hungenberg 2014; Whittington et al. 2020). “Socioemotional Wealth” (abbreviated as SEW) describes the nonfinancial goals of family businesses (Zellweger 2017) and is considered the most important theoretical development for family businesses in recent years (Brigham and Payne 2019; Nordqvist et al. 2015). SEW is widely known as the key driver of strategic decisions (Bertschi-Michel et al. 2022; Calabrò et al. 2018; Newbert and Craig 2017).

However, it is difficult to determine the point at which nonfinancial goals influence strategic management. Apart from the identification of overlaps between SEW and strategic management, there is a lack of clarity (Brigham and Payne 2019; Swab et al. 2020). Elements or dimensions are difficult to capture precisely. Consequently, there are still no tangible links between the dimensions of SEW and strategic activities.

This study provides a way to understand how the prevalence of SEW dimensions unfolds in the strategic management process. We address one overarching research issue with three associated research questions. This issue refers to the interrelationships between SEW and the strategic management process. Our corresponding research questions are as follows:

-

1.

Which phase of the strategic management process holds particular research potential?

-

2.

How can we create a greater orientation in overlapping areas?

-

3.

What are the specific relationships that exist between SEW and strategic activities in the field of Analysis and Forecast?

We answer the first research question through a systematic mapping of the research, which identifies particular knowledge gaps (Fisch and Block 2018). We draw on the constructs of three different SEW dimensions (Debicki et al. 2016) and five separate phases of strategic management (Berrone et al. 2012; Welge et al. 2017) to reveal areas of particular research potential. We answer the second research question by creating construct clarity that reduces the vagueness and ambiguity of SEW and strategic management. Through content analysis of pertinent literature, we examine the relationship between the two underlying constructs. The consolidation of codes into categories creates a structured overview of the fields examined. This structuring aid creates a novel and unique map of research. We address the third research question by disclosing the relationships between SEW and individual activities within the scope of strategic management. A conceptual framework illustrates the relationships and leads us to findings on how SEW priorities are linked to strategic activities.

The conceptual novelty and uniqueness of an integrative synthesis (Locke and Golden-Biddle 1997; Neubaum and Micelotta 2021; Weiss and Kanbach 2022) of SEW and strategic management contributes to an enhanced understanding of the characteristic decision-making (Thakur and Sinha 2020). Moreover, research-enhancing synthesis (Kraus et al. 2021; Webster and Watson 2002) identifies isolated knowledge silos. Our investigation leads to the conclusion that the strategic management phase of Analysis & Forecast receives the lowest academic attention so far.

This limited academic attention provides a promising field of investigation about the interaction of nonfinancial priorities with Analysis & Forecast. This study contributes to construct clarity (Brigham and Payne 2019; Suddaby 2010) by creating a categorization (Fisch and Block 2018) that extends our understanding of the relationships (Rheay and Whetten 2011; Short 2009) between SEW and strategic analyses.

Family firms are embedded in their macro-environmental settings (Bansal and Song 2016). Therefore, macro-environmental analysis is an essential component of strategic management (David and David 2017; Fahey and Narayanan 1986; Kail 2010). To make the conceptual connection between the two spheres of SEW and strategic management tangible, we shift our perspective to specific activities. To delve deeper into the issue of Analysis & Forecast, we create a unique conceptual framework between SEW and the macro-environmental analysis. We identify novel relationships (Reay and Whetten 2011; Weiss and Kanbach 2022) between SEW and tasks within the macro-environmental analysis process. In particular, we recognize connections between the categories of each of the SEW dimensions and activities within the process of macro-environmental analysis. This, in turn, provides tangible touchpoints for researchers and practitioners on which to focus their investigations.

Our article has the following structure. First, we outline the main elements of the strategic management process and SEW and integrate them into a conceptual matrix. Second, we describe the search method and coding procedure employed in our study. Third, we present the descriptive results within the conceptual matrix and the categorical findings derived from our content analysis. A synopsis of the categories’ content illustrates the particular relationships between SEW and the strategic management phase of Analysis & Forecast. Fourth, we developed a framework that identifies touchpoints between SEW and the activities of the macro-environmental analysis. Fifth, we conclude with a discussion of our findings, questions for future research, implications, and limitations of our study.

2 Theoretical frameworks

2.1 Strategic management process

The strategic management process analyses the formulation, development, and implementation of a strategy as a cognitive decision-making process in an organization (Chaffee 1985; Langley 1999; Nordqvist et al. 2015). It illustrates the procedural steps from strategy to action in an idealized way (Gagnè 2018). The strategic management process is a conceptual approach that disregards emotional aspects. However, the central premise of pure rationality without any emotions in decision-making has been widely criticized (Mintzberg 1978; Shiller 2019; Simon 2012; Thakur and Sinha 2020).

Several scholars view the holistic topic of strategic management as a wide-ranging process (Chaffee 1985; Soundararajan et al. 2018; Thomas 1984; Welch and Paavilainen-Mäntymäki 2014; Welge et al. 2017). The construct of an iterative strategic management process systemizes tasks (Grégoire et al. 2015; Hengst et al. 2020; Welge et al. 2017) within a firm. Thus, a processual view of strategy is a promising perspective for family businesses (Härtel et al. 2020). Since it has been cited close to two thousand times in Google Scholar by 2023, the widely accepted conceptualization by Welge et al. (2017) creates a structure and enables a synthesis with SEW. We select this framework for several reasons. A higher degree of fragmentation compared with other frameworks allows for a better delineation of phases. Additionally, this framework straightforwardly defines activities in strategic management. It clarifies the overarching construct and supports the content analysis of the literature. Furthermore, the framework enables us to set a focus in our research on concepts that are pertinent to our study.

The following phases describe the generic strategic management process:

-

Target Planning - This describes corporate policy, its guiding principles (including mission and vision), and other normative management tasks (Hungenberg 2014).

-

Analysis & Forecast - Internal corporate analyses, specifically strengths, and weaknesses, as well as external environment analyses (i.e., opportunities and threats), lead to prognoses and strategic foresight.

-

Formulation & Evaluation - It encompasses different levels of the strategy subject (i.e., the firm, the business unit, or the functional unit). It determines the deliberate direction (i.e., growth, stabilization, or shrinking) and evaluates it in a firm’s context.

-

Implementation - This phase considers plans and executions of mid- and short-term projects, as well as the short-term preparation of functional units and budgets.

-

Control - It continuously monitors the previous phases or steps in the strategic management process, serves as a steering and review mechanism, and creates governance structures. Figure 1 visualizes the strategic management process phases and briefly names the related items, as described by Welge et al. (2017).

Strategic management process phases and corresponding items (own representation based on Welge et al. 2017)

Family businesses have a principally high degree of centralization of decision-making (Felden et al. 2019), and the traditional separation between strategy content and strategy process is evaporating in family businesses (Nordqvist et al. 2015). That is, strategy development and its implementation are often taken care of by one or more family members at the same time. This approach creates a contextual understanding of the field of family business research and its applicability to businesses (Daspit et al. 2017). However, this does not mean that there are no contextual differences. For example, the influence of SEW on strategic targets (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011) and the role of emotions (Felden et al. 2019) in implementation is very pronounced in the strategic management of family businesses.

Particularly in family businesses, strategic management plays an important role (Jiang et al. 2018; Bammens et al. 2011). Various frameworks highlight the unique characteristics of family businesses in strategic goal settings (Chrisman et al. 2003; Williams et al. 2019). Much of the work about family business goals revolves around family-centered, nonfinancial goals. Chrisman et al. (2012) found a link between family involvement and the pursuit of nonfinancial goals (e.g., social status, family harmony, or identity). Some nonfinancial goals may enhance the financial well-being of an organization; others may undermine the financial goals of that organization. Therefore, it is of strategic importance for family businesses to understand the trade-offs between financial and nonfinancial goals (Daspit et al. 2017; Williams et al. 2019). For example, should a family member be favored in management succession? While this could maintain the management control of the family, it could also lead to inappropriate candidate selection. The traditional approach to the strategic management process does not address these conflicting goals.

2.2 Socioemotional wealth

SEW is defined as the nonfinancial emotional needs of a family’s individuals influencing the management of a firm (Debicki et al. 2016; Firfiray and Gómez-Mejía 2021; Jiang et al. 2018). As an umbrella construct (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011; Jiang et al. 2018; Memili and Dibrell 2019), SEW is widely considered the key driver of strategic decisions (Calabrò et al. 2018; Newbert and Craig 2017) and is seen as a key differentiator between family firms and nonfamily firms (Gómez-Mejía and Herrero 2022). Additionally, it is a major reason for the heterogeneity of a family firm because of the individual importance placed on SEW (Berrone et al. 2012; Boellis et al. 2016; McLarty and Holt 2019; Newbert and Craig 2017; Zellweger 2017). However, SEW is not a monolithic construct (Calabrò et al. 2018) and is composed of different dimensions (Vandekerkhof et al. 2018). Thus, a major difficulty of the construct is its broad spectrum and multidimensionality (Brinkerink and Bammens 2018; Thakur and Sinha 2020).

The construct of SEW explains why family firms behave uniquely (Firfiray and Gómez-Mejía 2021) and how owners gain SEW from several resources (Kalm and Gómez-Mejía 2016). This conceptual explanation is one of the most important developments within the past few decades (Brigham and Payne 2019), having resulted in far more than 1000 publications (Felden et al. 2019). “No matter which industry or continent, SEW always affects any family firm’s behavior one could think of and is their driving force” (Gómez-Mejía, Inaugural Lecture Jönköping University 24.09.2021).

In particular, as family firms are subject to the controlling family (Sluhan 2018) and their strong emotional priorities (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011), SEW preservation is considered their main reference point (Brigham and Payne 2019). Family members’ well-being, reputation (Block 2010), and traditional beliefs are examples. SEW theoretically dissects these decision drivers, such as family values (Xu et al. 2020; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011) or the social context of ownership (Belenzon et al. 2016). It is important to note that SEW is not only positive for the company. SEW offers a variety of benefits, such as added value for human resources (Chrisman and Holt 2016) or an increase in financial performance (Davila et al. 2022; Naldi et al. 2013). However, it can also be disadvantageous because it may result in higher borrowing costs (Naldi et al. 2013) or shareholder expropriation (Calabrò et al. 2021).

To directly measure SEW and make it more tangible, different scales have been developed. One approach to structure assumptions toward SEW defines five specific dimensions called “FIBER” (Berrone et al. 2012). While Hauck et al. (2016) developed a revised and shortened version called the “REI” scale, Debicki et al. (2016) proposed a scale called the “SEW importance” (SEWi) scale.

This article structures SEW as an accumulation of the three SEWi dimensions for different reasons. First, because of the reduced number of items inquired about, the shortness of the scale facilitates better practicability (Debicki et al. 2016). Second, the SEWi scale considers the subjective focus for nonfinancial goals instead of using proxies such as family ownership or management control. Such proxies insufficiently reflect the heterogeneity of family firms because they merely describe the apparent control structure. They neglect the individual influence of a controlling family and their individuals (McLarty and Holt 2019). Third, the broad dimensions of the SEWi scale arguably play a role in the decision-making of family firms. However, research has found some dimensions of the FIBER scale to be insignificant (Gerken et al. 2022).

The SEWi scale has three dimensions. First, a family firm is a vehicle of a family’s identity and the importance it attaches to SEW. Hence, Family Prominence within the community is a variable referring to the family’s value of image and reputation. This dimension illustrates the way the family portrays itself to the public through the firm. Second, the importance of SEW illustrates the desire for Family Continuity. Long-term orientation and the maintenance of unity substantially influence family firm behavior. Apart from the business dynasty and familial succession, overall, the family firm’s operational sustainability is also a part of this dimension. Third, business operations need to fulfill Family Enrichment. Hence, the well-being, harmony, and needs of the family members must be satisfied (McLarty and Holt 2019). This dimension addresses the feelings of belonging, financial stability, and happiness of relatives active in the family firm. In summary, Family Prominence, Family Continuity, and Family Enrichment define the SEWi dimensions. Figure 2 visualizes the SEWi dimensions and briefly names the related items, as presented by Debicki et al. (2016).

SEWi dimensions and corresponding items (own representation based on Debicki et al. 2016)

2.3 Integration of socioemotional wealth and the strategic management process

Our theoretical synthesis of the two theoretical frameworks of SEW and the strategic management process integrates a unique conceptualization, which allows for a new perspective on the literature. Despite SEW being a dynamic topic throughout previous years, it has not benefited from a comprehensive review in the context of strategic management (Torraco 2016).

Both spheres consider the company as a whole and are not limited to individual subareas. On the one hand, the strategic management process has links to many activities in a family business (Daspit et al. 2017; Felden et al. 2019) and offers a view of strategy in practice (Prashantham and Healy 2022). This theory approach represents a generic model that is suitable for fusion with another theoretical construct (Thomas 1984). Because of the model’s generality, we avoid cognitive bias through overspecialization. On the other hand, SEW describes a holistic view of nonfinancial goals in family firms (Zellweger 2017). While essential for the family firm’s management (Brigham and Payne 2019), it influences nearly every division of the company. Consequently, due to their holistic perspectives, these two encompassing approaches might have touchpoints with each other.

Our matrix illustrates these intersections and brings both research streams together. This creates a link between the strongly emotional perspective of SEW (Felden et al. 2019) and the supposedly objective perspective of the strategic management process (Hungenberg 2014). The matrix approach lays the foundation for deconstructing publications into their essential findings. Thus, it provides the first step of a critical analysis of the literature, identifying incomplete research (Torraco 2016). Figure 3 visualizes the intersections between the two theoretical spheres and captures how SEW and the strategic management process are intertwined (King et al. 2022). The dimensions of SEW might not show an obvious relationship with the phases of the strategic management process but rather have complex ways of influencing corporate strategy (Hsueh et al. 2023). While some influencing factors affect the entire strategic management process (Felden et al. 2019; Williams et al. 2018; Zellweger 2017), we find distinctions between different areas and topics from the holistic analysis in terms of popularity, weight, or applicability.

3 Methodology

3.1 Search methods

A systematic literature review builds a reliable basis for processing advanced considerations of interdisciplinary fields in theory (Devers et al. 2020; Palmatier et al. 2018; Snyder 2019; Swab et al. 2020; Tranfield et al. 2003; Webster and Watson 2002). Hence, we proceeded through a list of stages of a systematic review (Aguinis et al. 2018; Boote and Beile 2005; Fisch and Block 2018; Tranfield et al. 2003; Xiao and Watson 2019). We examined publications on SEW and strategic management by performing three search approaches simultaneously. While the database search made use of extensive scientific content, we manually performed an additional journal search. Finally, a snowball search rounded off the procedure.

The three search components of Socioemotional Wealth, Strategic Management, and Family Business were the central elements of this research, leading to 24 search terms by formulating synonyms or closely related topics (e.g., “family firm” or “family business”, and “strategic management process” or “strategic leadership”, and “socioemotional wealth” or “non-financial performance”). A Boolean search (“AND”) resulted in the combination of one search component with each of the 24 terms. Consequently, we developed 72 search strings (see Appendix 1).

The databases used were EBSCO, one of the largest sources for bibliometric studies (Linder and Foss 2018), and ABI/INFORM by ProQuest, providing key journals from scholarly publishers worldwide. Furthermore, we employed Web of Science by Clarivate Analytics, which contains a great number of qualitatively selected journals, as well as EconBiz by Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, a noncommercial specialized library sponsored by the German Research Foundation. The search criteria were the year of publication (i.e., from 2007 [as the date of the conceptualization of SEW] until the end of 2022), English as the language of the publications, and publication in a peer-reviewed journal. After the exclusion of duplicates, we sorted all publications by the impact factor of their journals: CiteScore by Elsevier. We chose this approach because, despite academic controversy (Vogel et al. 2017), publication rankings do play an important role as indicators of scientific work (Frey and Rost 2010; Williams et al. 2019).

Moreover, to obtain a representative and unbiased sample of research publications, this review included a manual journal search. After we had gathered a diverse range of opinions on pertinent journals (Memili and Dibrell 2019; Rovelli et al. 2021; De Massis et al. 2012; Siebels and Zu Knyphausen-Aufseß 2012) and had reviewed their CiteScore, we selected the peer-reviewed journals for our study. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice (ETP), Family Business Review, and Journal of Business Venturing were judged as promising outlets. Additionally, we reviewed two top-ranked strategic management journals, Management Science and Strategic Management Journal, in this search step. In addition, we included Management Review Quarterly as a highly relevant journal that specializes in systematic narrative literature reviews.

Simultaneously with the search steps described, we continuously studied cited articles from peer-reviewed journals and other academic publications. Ergo, a backward-oriented literature scan via citations resulted in further publications for analysis. In addition, a forward-oriented review approach created another way to discover relevant literature. Using Publon’s Web of Science database, we identified publications based on their citations from a previously defined starter set.

3.2 Consolidation of search results

The consolidation of the three different searches resulted in an overall sample of 486 publications. An assessment of each publication via the bibliographic metric of CiteScore by Elsevier, as well as its currency, resulted in a condensed review sample of 169 publications. The author performed the entire review process with the close support of an academic supervisor. Several rounds of discussion led to the preparation of new discussion points and iterative adjustments. Figure 4 illustrates the entire search method concisely.

3.3 Coding procedure

A thematic and interpretative analysis approach fits the textual heterogeneity of the studies and the context of ambiguous constructs (Suddaby et al. 2017). Furthermore, an exploration of qualitative and quantitative data increased the validity of the explanations of the phenomena (Ody-Brasier and Vermeulen 2020). Therefore, this review collected data via random sampling and a subsequent qualitative relevance assessment. Such a combination of an in-depth analysis with systematic cataloging of quantitative data (Langley 1999) systemized the perspective on the thematic overlaps of SEW and strategic management. In doing so, we deconstructed the publications into basic ideas and core findings.

Turning to the systematic process of content analysis, the conceptualization of the analysis process was inspired by Mayring’s (2015) sequential steps. This paper followed a structured procedure (Neuhaus et al. 2022; Saldaña 2009), and one author performed the coding process. First, we coded text passages using the SEWi (Debicki et al. 2016) and strategic management process (Welge et al. 2017) frameworks. These frameworks enabled a categorical assignment to codes. At the same time, frequent consultations with an academic scholar ensured logical consistency and scientific rigor. Finally, we performed intra-coder reliability. Figure 5 illustrates these steps.

The text excerpts of the key findings were first-level codes of the corresponding dimension respectively phase. That is, each matrix field (see Fig. 3) illustrated an interface between the two constructs and represented a category. For example, value definitions (for the strategic management process phase of Target Planning) and their community impact (for the SEW dimension of Family Prominence) created an identifiable category. We summarized the categories in a superimposed theme: the respective relevant strategic management process phase. The careful allocation of each key idea within the sample resulted in different quantity distributions for each article. While some articles showed only marginal or even no match with the conceptual matrix, seminal articles registered various key ideas.

To ensure the quality standards (Auerbach and Silverstein 2003) of the content analysis with respect to appropriate reliability (Mayring 2015), we performed an intra-coder reliability check. With a sufficient time gap between the two coding procedures (Lacy et al. 2015), we randomly selected 45 data points within the sample, which led to a code congruency of 95.6%. This consistency is in line with other family business studies (Swab et al. 2020). Moreover, we held stakeholder checks (Thomas 2006) to discuss the codes iteratively with a family business expert during regular discussions. We provided the list of codes and their interpretation to an independent scholar for review. Thus, the codes were reflected and their interpretations verified. Additionally, two academic conferences provided possibilities to review and discuss the codes with further scholars in breakout sessions, as well as presentation feedback. Codes and their argumentation for content contexts in the strategic management process were challenged on several occasions.

We performed an iterative process of content analysis in accordance with Mayring (2015) to derive a uniting category system. This category system put the theme of Analysis & Forecast in an empirical context with SEW.

We focus on macro-environmental analysis in the further content analysis. It is concerned with the external forces that are typically categorized into the social, economic, technological, political, and regulatory environments (Ginter and Duncan 1990). One example of a macro-environmental analysis is a normative process framework. It defined the four key recursive activities of Scanning, Monitoring, Forecasting, and Assessing (Fahey and Narayanan 1986; Ginter and Duncan 1990). To assign the codes to the four activities of the macro-environmental analysis, we followed a uniform set of rules based on Fahey and Narayanan (1986). First, we viewed the single code in the context of its representative publication. We then made argumentative considerations to reason the assignments of the codes and assigned the code to an activity within the normative framework of Fahey and Narayanan (1986).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive analysis

Combining, decomposing, and integrating two theoretical constructs leads to richness, theoretical clarity, and generality (Langley 1999; Mele et al. 2015). Hence, the synthesis performed in this paper creates new learnings (Kraus et al. 2021) by weaving together the ideas of SEW and the strategic management process from the literature into a distinctive framework. Combining these two ideas, we develop a matrix. The three rows represent the SEWi dimensions, and the columns represent the strategic management process phases (see Fig. 6). This approach visualizes different dimensions (Langley 1999) and facilitates an easy grasp of content analysis. Nevertheless, the selection of adjacent fields within the matrix is neither exact nor exclusive. The arrangement rather illustrates intuitive subject clouds or groupings with overlapping fringes. Presuming the equal relevance of all SEW dimensions and strategic management process phases, the least researched fields may point to potential research gaps.

The basic idea of the matrix approach is, first, to identify relevant publications based on a systematic literature review. Subsequently, we assign the codes to the individual intersections or matrix fields. The content analysis produces an extensive list of text excerpts discussing core ideas or key findings. Each matrix field refers to the intersection of a SEWi dimension and a strategic management process phase. The allocation of all identified findings to a matrix field results in a remarkable quantity distribution. Each circle in Fig. 6 represents a code assigned to the applicable matrix field. Different shadings of the circles help the reader differentiate between the three SEWi dimensions. The percentage figures represent the share of each dimension or phase in the final sample. In this way, we can identify the strategic management process phase that is least discussed in the literature. Figure 6 provides an overview of the allocated codes within the conceptual matrix and their quantity distribution.

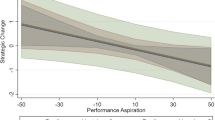

On evaluating the resultant quantity distribution, we make a remarkable finding. The percentages on the right side of the matrix show that the number of codes is evenly spread between the three SEWi dimensions. Consequently, all SEWi dimensions demonstrate a relationship with the strategic management process. However, the percentages below the matrix show the unbalanced distribution of codes between the different strategic management process phases. The strategic management process phases of Target Planning (29%) and Formulation & Evaluation (35%) demonstrate an intense discussion in research. The strategic management process phases of Analysis & Forecast (10%), Implementation (13%), and Control (13%) show reduced academic attention.

Therefore, we assume that the three least discussed phases may have special potential for research gaps. The least discussed phase in the reviewed literature is the Analysis & Forecast phase. This finding matches the longstanding calls of scholars for a broader knowledge of corporate analyses (Ansoff 1975; Fahey and Narayanan 1986; Ginter and Duncan 1990). We select the phase of Analysis & Forecast for further investigation and justify this by the following points. Organizations depend on their environment and internal capabilities (Whittington et al. 2020) to understand their strategic position. Otherwise, the survival of the business is at stake (Aldrich and Pfeffer 1976). Particularly, the external environment is key for the family business it operates in (Daspit et al. 2017; Mack et al. 2016; Nordqvist et al. 2015). Thus, there is a pertinent need for research to examine further how family businesses react to external threats and opportunities (Bertschi-Michel et al. 2022). In the current highly uncertain and complex environment, the vulnerability of family businesses to external threats has increased (Wimmer 2023). For this reason, we will focus our investigation on the phase of Analysis & Forecast.

4.2 Categorical findings

Within the Analysis & Forecast phase, we find five overarching categories assigned to the three SEWi dimensions. Not surprisingly, Social Capital plays a noticeable role in the relationship-relevant dimension of Family Prominence. Nevertheless, the analytical focus employed—specifically internal vs. external views—is also a well-discussed category in this dimension. Family Firm Control is an evident category of the SEWi dimension of Family Continuity. Internal Attributes of the family firm, such as the personalities of members of the management or heterogeneous inheritance rules, are relevant components in this dimension. In contrast to the two previous dimensions, we identify only one category in the dimension of Family Enrichment, labeled Goal Orientation. In this context, the harmonization of family interests with other stakeholders of the family firm is at the center of attention. Figure 7 summarizes the affiliation of the categories to the SEWi dimension.

The quantity distribution among the three different SEWi dimensions and the entire strategic management process is evenly distributed (see Fig. 6). We note the same in only the Analysis & Forecast phase, which also illustrates the balanced importance of SEW. However, our content analysis results in the finding that about half of the codes refer to an environmental issue (i.e., about every second code mentions either explicitly an external issue [e.g., the national context of the family firm] or a resource, which is the product of external relations [e.g., reputation or legitimacy]). The other half of the identified codes mainly addresses family characteristics, such as kin ties, dynastic motives, or bifurcation bias. We focus on the examination of external analysis because it is an essential part of strategic management (Aldrich and Pfeffer 1976; Chrisman et al. 2003; Dyer and Whetten 2006) in family businesses. In addition to environmental forces influencing the performance of a firm (Bates 1985; Furrer et al. 2008), activities within an external environmental analysis are part of effective strategic management (Mackay and Burt 2014).

The following sections outline the key aspects of each category. Using the process for content analysis (Marying 2015), we have formed a category system to achieve a structure of the research field. Hence, we leave the abstraction level of the categories again to inform the reader about the relevant contents in a condensed form. The content discussion of the codes provides pragmatic examples of how interrelationships between SEW and Analysis & Forecast occur.

4.3 Synopsis of findings in the literature

The following section provides a synopsis of the findings identified by the content analysis. This illustrates how specific aspects of the SEWi dimension of Family Prominence stimulate the strategic phase of Analysis & Forecast.

The SEWi dimension of Family Prominence refers to relational features and the accumulation of Social Capital. Social Capital is a resource that results from social relationships (Brigham and Payne 2019) and is of high value for family firms (Chrisman et al. 2008). It is a vital element of Family Prominence (Debicki et al. 2016). The findings show that Social Capital has structural, cognitive, and relational components (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). These components have both positive and negative effects.

On the one hand, family firms may achieve a higher economic performance if family members had an education abroad with a diverse network (Han et al. 2019). In addition, an information advantage provided by political connections may result in the assessment of relations as a strategic asset (Dinh and Calabrò 2018). While the relationships of top management may be a source of business opportunities, these relationships are an indicator of the trend of network building (Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano 2018). The identification of such a trend and its reflection in forecast models might be characteristic of the Analysis & Forecast phase. The general reference to the advantages of social capital, as by Cruz et al. (2012), implies an assessment and a simultaneous analysis of such advantages.

On the other hand, Dean et al. (2019) described the hegemonic logic leading to discriminatory behavior against women. They reasoned this on the identified trend that women have a reduced network because of a lack of resources. Dinh and Calabrò (2018) argued that an emphasis on relational value can cause corruption. While this point may seem plausible, it is observable only in an external context. Furthermore, we need to analyze internal weaknesses and dependencies. A higher amount of social capital increases the difficulties for nonfamily members in entering a firm because they may not have access to relational sources (Herrero 2018). Another example is the reliance of a family firm on the government’s orientation (Duran et al. 2017).

The Analytical Focus (i.e., the investigative lens being set) leads the way in which a firm examines its environment. For example, the type and degree of embeddedness can be such a focus. Cultural aspects such as historical events (Pierce and Snyder 2020) or long-established law regimes (Caiazza et al. 2019) mediate it. A rural setting positively affects local embeddedness (Zellweger et al. 2019), but opportunities from embeddedness depend on the actual country and culture (Reuber et al. 2017). Another example is a manager’s emphasis on external analysis (the macro-environment) instead of internal aspects (Köseoglu et al. 2020) or entrepreneurial assessments of external factors (Williams et al. 2020).

Table 1 illustrates the related codes and their associated subcategories and categories of the SEWi dimension in a summarized form.

The following section provides a summary of the results of our content analysis. It illustrates how various perspectives from the SEWi dimension of Family Continuity shape the strategic phase of Analysis & Forecast.

The SEWi dimension of Family Continuity refers specifically to the maintenance of a family’s unity, values, and dynasty. However, only the controlling role of a family (Swab et al. 2020) can ensure this and is always unique, as every family is unique in itself. External trends for organizational change (Müller and Kunisch 2018) and the institutional environment (Miroshnychenko et al. 2021; Pindado and Requejo 2015) moderate the positive and negative effects of family control. The legitimacy of a family firm, considered the right to exercise control, creates a competitive advantage by determining financial performance (Berrone et al. 2020). Furthermore, the findings by Duran et al. (2017) illustrate the general reluctance on the part of family firms toward internationalization as long as the target country’s governmental ideology influences family control. We cluster these aspects into the category of Family Firm Control.

The idiosyncrasy of family firms becomes apparent through the multiple and ambiguous roles played by family members. The call for further research on the heterogeneity of family firms emphasizes this. The uniqueness starts at the top of the corporate hierarchy with the chief executive officer’s (CEO’s) age and its correlation to his or her preference for continuity over growth (Belenzon et al. 2019). Nevertheless, evenly distributed knowledge at the team level facilitates improved decision-making and information processing (De Mol et al. 2015). Additionally, the type of internal cohesiveness in the family (Arregle et al. 2019) and the support of the incumbents for their successors (Carr et al. 2016) determine the individual situation of inheritance and succession. The emphasis on varying goal outcomes, such as enduring relationships, reliable governance, or efficient operations (Williams et al. 2018), is a result of these attributes. The effect of marriage on wealth preservation for future generations (Belenzon et al. 2016) is a factor in the unique goal orientation of a family firm. We group these particularities into the category of Internal Attributes.

Table 2 illustrates the related codes and their associated subcategories and categories of the SEWi dimension Family Continuity in a summarized form.

This section shows how specific aspects of the SEWi dimension of Family Enrichment influence the strategic phase of Analysis & Forecast.

The SEWi dimension of Family Enrichment refers to the family’s needs in—and harmony between—all family members. This applies regardless of whether or not family members are active in businesses. Common interests and aligned trajectories for future strategies are essential in this context. A fundamental issue is the weighting of family and business interests (Gómez-Mejía and Herrero 2022). While formal and informal institutional settings are considered (Berrone et al. 2020), close kin ties carry positive behavioral aspects, such as better coordination and cooperation. However, they may also create risks of nepotism, less diversity, and spillovers from personal conflicts (Ertug et al. 2020). Furthermore, harmony and psychological safety reduce the negative effects of disagreements (Vandekerkhof et al. 2018). Gentry et al. (2016) observed an overall risk aversion in family firms. In addition, the discussion of factors for success and failure is considered an element of Goal Orientation. The way of re-entry into a business (Williams et al. 2020), the employment of assets (González-Rodríguez et al. 2018), and the role of emotion stocks during poor performance can decisively influence a family firm’s performance. Although the SEW dimension of Family Continuity above refers to the role of governmental ideologies, political beliefs also influence the dimension of Family Enrichment under the category of Goal Orientation. For example, Duran et al. (2017) found reduced risk aversion on the part of family firms in the case of aligned governmental ideologies. Moreover, the conviction that it is less complicated to create common trajectories than to change an existing corporate culture may lead to an overall preference for greenfield investments over acquisitions (Boellis et al. 2016).

Table 3 illustrates the related codes with their associated subcategories and categories of the SEWi dimension Family Enrichment in a summarized form.

4.4 Interim results

A thorough content analysis of the reviewed studies creates a category system that improves construct clarity. In conclusion, we relate all three SEWi dimensions to five categories (see Fig. 7). These relationships between SEWi dimensions and categories facilitate the identification of cross-construct links. For example, the information advantage provided by political connections (Dinh and Calabrò 2018) may result in the assessment of personal contacts as a strategic asset. This type of Social Capital category can be linked well to the SEWi dimension of Family Prominence. Overall, we identify such relationships among all codes, which are bundled in categories and linked to the SEWi dimensions.

Our five categories create a greater orientation in the overlapping fields of SEW and Analysis & Forecast, but we aim to identify specific relationships between SEW and single activities within this phase of the strategic management process. By reviewing the single codes in detail, close to half of the identified codes refer to external aspects. These codes refer to topics such as external stakeholder management (e.g., Berrone et al. 2020; Vandekerkhof et al. 2018), social embeddedness (e.g., Dinh and Calabrò 2018; Duran et al. 2017; Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano 2018; Zellweger et al. 2019), or economic constituents (Caiazza et al. 2019; Köseoglu et al. 2020; Pierce and Snyder 2020; Williams et al. 2020). Still, the relevance of external issues is not recognizable from the categories. In particular, the external environment holds crucial factors for the performance and continued existence of the family business (Aldrich and Pfeffer 1976; Daspit et al. 2017; Mack et al. 2016; Nordqvist et al. 2015). Therefore, in the next section, we develop a framework that decisively illuminates the relationships between SEW and environmental analysis.

4.5 Framework findings

Figure 8 illustrates the framework that has been created, consisting of SEW dimensions, related categories, and the macro-environmental analysis process (Fahey and Narayanan 1986). It refers to the codes identified in the literature review, groups them into categories, and relates them to the activities of the macro-environmental analysis. While the previous sections explain the mapping rules, Fig. 8 explains the content connections. The links are dashed lines in the following figure and illustrate the connections between the categories per SEWi dimension and each activity of analysis. The gray-shaded fields highlight potential missing links in the research literature.

The dimension of Family Prominence includes the categories of Social Capital and Analytical Focus. Social Capital is essentially concerned with the advantages and disadvantages of social relationships. The analytical activity of Scanning focuses on the identification of trends. Hence, the impact of personal characteristics such as education (Han et al. 2019), gender (Dean et al. 2019), or family membership (Herrero 2018) on Scanning are identified as trends. Two aspects of our analysis affect Monitoring. First, indicators of Social Capital such as reliance (Duran et al. 2017) and relationships of the top management team (Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano 2018) are considered. Second, the historical development of trends, such as the potential of Social Capital for corruption (Dinh and Calabrò 2018) or the maintenance of human resource stability (Duran et al. 2017), is an essential observation in Monitoring. Assessing refers to the evaluation of the benefits and utilities of relationships. Political relationships are considered a strategic issue (Dinh and Calabrò 2018), but nonfinancial benefits related to Social Capital can also be assessed more broadly (Cruz et al. 2012). We divide the identified category Analytical Focus into embeddedness mediated by cultural aspects and the internal vs. relational perspectives of analysis. The Scanning activity deals here with suggestions to focus on the external analysis of managers (Köseoglu et al. 2020) and the entrepreneur’s subjective perception of external success factors, as in Williams et al. (2020). Our analysis identifies contact points of Monitoring with the institutional strength as an indicator of the concentration of ownership (Pierce and Snyder 2020). However, national culture is also identified as an indicator of tendencies toward competition or collaboration (Caiazza et al. 2019). Looking at the whole dimension of Family Prominence, we see that three activities of macro-environmental analysis have points of contact. Only the activity of Forecasting does not register any connection with the prominence of the family.

The dimension of Family Continuity covers the categories of Family Firm Control and Internal Attributes. Family Firm Control relates to the involvement in a firm’s management or the possible exercise of power. The analytical activity of Forecasting alone shows a connection to the category of Family Firm Control, but this is in many ways. Müller and Kunisch (2018) viewed projections on internal and external matters as key performance drivers that ultimately influence a family’s control over its business. However, Pindado and Requejo (2015) saw the institutional environment of family firms as decisive for their control. For Family Firm Control in conjunction with the prevailing culture, Berrone et al. (2020) saw legitimacy as a significant factor for Forecasting, while Duran et al. (2017) analyzed internationalization in the context of Forecasting. Since the category of Internal Attributes refers to the individual characteristics within a family firm, we distinguish between the characteristics of the top management team, family-specific inheritance rules, and subjective risk preferences. The activity of Scanning refers, in this context, to the identification of firm-internal characteristics. While we identify the age of the CEO (Belenzon et al. 2019) or the social skills of board members (De Mol et al. 2015) as relevant, the identification of trends toward more egalitarian inheritance rules (Arregle et al. 2019) and debt capital in connection with risk management are also important (Belenzon et al. 2016). We find the Forecasting activity in the discussion of underlying forces for family presence in a family firm (Williams et al. 2018). The more important corporate goals are for a family’s projections, the more present the family is in the day-to-day business of the company. Carr et al. (2016) related elements of inheritance to the activity of Assessing. They identified potential problems in the inheritance of nonfinancial assets, such as reputation. Looking at the entire dimension of Family Continuity, we identify links to all analytical activities but one; only the activity of Monitoring is excluded in view of this dimension.

The findings in the dimension of Family Enrichment address the alignment of goal preferences, success factors, and influencing factors in the course of family need satisfaction. We label this category Goal Orientation. The precise definition of the internal and external environment (González-Rodríguez et al. 2018; Shepherd 2016) is the first step in Scanning. Moreover, this analytical activity shows a link to the identification of trends (Fahey and Narayanan 1986). A trend toward a greater weighting of SEW leads to a higher emotional value (Vandekerkhof et al. 2018), and the growing influence of government ideology affects the internationalization of family firms (Duran et al. 2017). In addition, the prevalence of family firms in a country leads to strategic conformity (Berrone et al. 2020). In addition, the proximity of kinship ties is identified as an indicator of nepotism under lower solidarity (Ertug et al. 2020). The activity of Monitoring recognizes development patterns of trends. Gentry et al. (2016) did this by examining increasing family involvement and the resultant accumulation of slack resources, as well as risk aversion. Dinh and Calabrò (2018) shed light on another pattern. The increase in legal institutional functions leads to a higher union of ownership and leadership. However, the discovery of development patterns also occurs in the activity of Forecasting but across different segments. Williams et al. (2020) fulfilled this quest by identifying patterns of internal success factors across aspects of individual characteristics, management style, and marketing. In addition, Boellis et al. (2016) examined the constraints that political framework conditions could represent for projection. Looking at the whole dimension of Family Enrichment, we see that three activities of macro-environmental analysis have points of contact. The activity of Assessing does not register any connection with Family Enrichment in the existing research.

In conclusion, we found touchpoints between all SEWi dimensions and the analytical activity of Scanning. Conversely, the dimension of Family Prominence deals with all analytical activities except Forecasting. The dimension of Family Continuity, however, relates to all activities except Monitoring. Finally, the Family Enrichment dimension deals with all activities other than Assessing. Thus, we found touchpoints between each SEWi dimension and all analytical activities but one. Figure 9 illustrates the disregard of the three SEWi dimensions in relation to the framework of Fahey and Narayanan’s (1986) macro-environmental analysis process.

5 Discussion

Individual SEW dimensions cannot be considered in isolation, as environmental factors typically affect multiple dimensions simultaneously (Naldi et al. 2013). Hence, it seems pertinent for research to consider all three SEWi dimensions in a balanced manner. The equal distribution of codes across the three SEWi dimensions in our conceptual matrix supports this approach (see Fig. 6). This is particularly important because the various aspects of SEW have a significant impact on family business behavior (Brigham and Payne 2019). Imbalanced academic attention would result in a failure to address the critical aspects of SEW.

However, such a failure seems to be present when considering strategic management aspects. The literature confirms the substantial role of the external environment in family businesses (Daspit et al. 2017; Mack et al. 2016; Nordqvist et al. 2015), especially when assessing external threats and opportunities (Bertschi-Michel et al. 2022). However, we found an unbalanced distribution of the codes across the phases of the strategic management process in our conceptual matrix. This observation suggests the least academic scrutiny of the Analysis & Forecast phase. Such a contradiction highlights the idea that companies pay more attention to conducting external analyses during periods of macro-environmental turbulence (Brunelli et al. 2023). Ginter and Duncan (1990) have already argued that turbulent markets, competitive threats, and necessary investments increase the need for an appropriate macro-environmental analysis. This perspective becomes even more important, given the global economic conditions.

The SEWi dimension of Family Prominence relates to our categories of Social Capital and Analytical Focus. The literature recognizes various benefits (Cruz et al. 2012; Dinh and Calabrò et al. 2018; Han et al. 2019; Hsueh and Gomez-Solorzano 2018), as well as drawbacks (Dean et al. 2019; Dinh and Calabrò et al. 2018; Duran et al. 2017; Herrero 2018), associated with Social Capital. It is crucial to approach Social Capital objectively, without idealizing it. A primary Analytical Focus in the literature is the embeddedness of family firms in their local communities (Pierce and Snyder 2020). This is mediated by the cultural aspects and internal perspectives of the analysis. Cultural contexts and internal criteria, such as risk aversion (Gómez-Mejía and Herrero 2022) or managerial capabilities (Dayan et al. 2019), are essential for the strategic development of a family business. However, the role of the Family Prominence dimension in fostering resilience is also crucial. More specifically, Family Prominence can contribute to building trustful relationships with customers and suppliers or securing reliable employment relationships (Calabrò et al. 2021).

The SEWi dimension of Family Continuity relates to our categories of Family Firm Control and Internal Attributes. Family Continuity especially concerns the preservation of family unity and its values (Debicki et al. 2016). A critical aspect of this dimension is therefore the maintenance of Family Firm Control. However, this aspect must be approached in a nuanced way when examining the corporate governance structures of family businesses. While fewer conflicts with agents might exist, there is also the risk of insufficient representation of non-family shareholders’ interests. Moreover, some scholars consider family businesses to be self-centered and antagonistic to external stakeholders because they distrust anyone outside the family (Berrone et al. 2014). Internal Attributes, such as family values, involvement in the business, and governance structures, are important factors to consider when discussing family businesses (Daspit et al. 2021). Although family businesses exhibit a varied and diverse range of characteristics internally, it is crucial to consider how they align with the opportunities and challenges posed by the external environment (Debicki et al. 2009; Miles et al. 1978). In light of this, it is vital to acknowledge that no family business operates in isolation from the external environment (Mack et al. 2016).

We identified a relationship between the SEWi dimension of Family Enrichment and the Goal Orientation of the family. In family firms, success is subjectively perceived, relying on various individual interests and success factors. Research underlines this idea by focusing on the internal factors of the family business (Nordqvist et al. 2015). However, an outside-in perspective appears critical as well because misperceptions of the environment can be a threat to the success or even survival of the family business (Nordqvist et al. 2015).

A comprehensive evaluation of both internal and external factors is vital in determining the strategic potential of a family business (Carlock and Ward 2001). Based on our integrative framework, we identified touchpoints between the SEWi dimensions and the macro-environmental analysis activities but one. The different SEWi dimensions interact in a complex way, emphasizing the need for a holistic perspective (Hsueh et al. 2023). However, the assumption that all macro-environmental analysis activities are equally important suggests that research has not achieved a holistic view. Thus far, investigations into the connections between the pivotal SEW viewpoint (Brigham and Payne 2019) and specific actions within macro-environmental analysis remain insufficient.

6 Future research

Future research offers further areas to explore concerning the SEW dimension’s relationship with the different activities of macro-environmental analysis. Since SEW significantly guides the fundamental goals, behaviors, structures, and resources of family firms (Chrisman and Holt 2016), we need further investigation of this area. The avenues formulated for future research below will facilitate springboards for inspiration (Paul and Criado 2020).

From a general perspective, the calls for qualitative or mixed-method approaches (Neuhaus et al. 2022; Williams et al. 2018) and longitudinal studies (Dean et al. 2019) are encouraging for further research. In addition, the utilization of theories from different disciplines (Pindado and Requejo 2015) and the risk of SEW’s reification (Murphy et al. 2019) appear to be promising research paths. Moreover, the differentiation of strategic actors in family firms or addressing the nonlinearity of strategic change (Müller and Kunisch 2018), as well as diversity and a team’s legitimacy (De Mol et al. 2015), provide research opportunities. Last but not least is the opportunity to consider other conceptualizations of SEW in this research context, such as the FIBER scale (Berrone et al. 2012) or the RREI scale (Gómez-Mejía and Herrero 2022).

Additionally, we like to highlight a research agenda along the sweet spots identified in the above findings. Table 4 lists several potential research questions. We group these questions by the corresponding SEWi dimension and its disregard for analytical activities (Fahey and Narayanan 1986).

Various reasons lead to the necessity to address the above research questions. The preceding content analysis in the context of this paper reveals that research has not adequately addressed the different topics related to SEW and macro-environmental analysis. Hence, we achieve novelty in research and advance theoretical knowledge. Furthermore, all the research questions offer practical implications. For example, managers could use findings from our first suggested research question to create an improved relationship network and derive techniques for best employing Social Capital for firm performance. The research questions will also contribute from a theoretical perspective. Future studies could draw on frameworks such as network theory, behavioral theory, or institutional theory to create further knowledge. This will allow precise fields of application and contribute to the development of theory in the context of family business research.

7 Implications

Owing to the specificity of SEW, family firm scholars and practitioners benefit from advanced clarity (Brigham and Payne 2019; Neubaum and Micelotta 2021; Whetten 1989). Our paper supports communication and the ability to explore phenomena with greater creativity (Suddaby 2010). The bundling of different codes into subcategories and aggregated categories facilitates the identification of cross-construct links. We examine the relationship between two underlying constructs (Bansal and Song 2016)—SEW and strategic management process—with a specific focus on Analysis & Forecast. This novel research focus illuminates the relevance of SEW (Reay and Whetten 2011) on strategic management. The consolidation of codes into (sub-)categories under the theme of Analysis & Forecast provides the reader with an overview of the fields examined. The identification of common categories allows structuring, which creates an orientation within the manifold field of research. This structuring aid creates a novel and unique map of research, which is useful for scholars, as it provides a focused, yet unbiased, view of the research construct (Clark et al. 2021). The list of codes among the different categories facilitates accessible knowledge and helps in the determination of an emphasis for future research.

Providing insights from a practical perspective is a key goal of this study. Hence, the findings in this paper shall discuss real-world problems (Nippa and Reuer 2019) and give managers inspiration for corporate practices. The issues and aspects discussed in this paper all relate to actual decision-making situations or opportunities for strategic alignment in one direction or another.

The conceptual matrix that has been developed (see Fig. 3) answers the call for useful theories from a practitioner’s point of view (Dyer 2018). This shows that strategic management and SEW have a relationship that has considerable relevance to an outside manager in a family firm. This view helps to mentally structure the comprehensive constructs of SEW and strategic management. It identifies potential emphases from a SEW perspective and the need for development in a strategic management context. Possibly, the identified research tendency toward Target Planning, in combination with Formulation & Evaluation, suits the current need of family firms for internal considerations. Otherwise, the least represented strategic management process phase of Analysis & Forecast could provide a puncture site of most development potential. Managers may examine the conceptual matrix and identify their individually promising intersections.

The integration of SEW and the strategic management process phase of Analysis & Forecast helps us further understand the underlying nonfinancial motives in a family firm. This study helps managers understand the mechanisms that influence the target orientation of certain ways of implementation (Swab et al. 2020). That SEW considerations impact each strategic management process phase in one way or another is, therefore, a central insight for stakeholders of every family firm.

In the course of construct clarity, this paper describes which aspects are SEW-relevant and how they are linked to Analysis & Forecast. This illustrates the moderating role of SEW and can be applied to one’s own firm. For instance, a successor’s education abroad often results in a larger and more diverse network. This can be a valuable resource in the future as a company manager. Moreover, it creates greater awareness of issues related to corporate social responsibility and external macro-environmental impacts (Han et al. 2019).

The integrative framework (see Fig. 8) illustrates the links in a tangible way for managers so that they receive a grid of interrelations. This will help make company-specific considerations and identify critical aspects at an early stage of macro-environmental analysis.

8 Limitations

Like every piece of research, this paper is not immune to limitations. While this investigation answers the call for scientific rigor, it is also exploratory and, naturally, not exhaustive. The literature review conducted at the outset may have overlooked some publications. However, a large initial set of papers and a multistep approach (Tranfield et al. 2003) have minimized this risk.

The SEW construct is subject to unclear dimensionality (Brinkerink and Bammens 2018; Huang et al. 2020; Thakur and Sinha 2020; Vandekerkhof et al. 2018). However, while no consensus on prevailing SEW dimensions has been found, it creates research opportunities and confusion (Newbert and Craig 2017; Ravasi and Canato 2013). The immense popularity of SEW (Mensching et al. 2014) has led to an impressive number of publications over the past few years (Swab et al. 2020). Because of this tremendous growth in the literature, there is a risk of reification (Jiang et al. 2018). In this case, a concept is objectified as something concrete, whereas the underlying human feelings and intentions are neglected.

Generally, the strategic management process should not be viewed as a sequence of actions (Buckley and Casson 2019) but as a cyclical generic process with a recursive nature (Grégoire et al. 2015; Thomas 1984). Hence, the strategic management process does not describe a linear approach consisting of successive process steps in an orderly structure. Rather, it is an abstraction of essential components of strategic management, which are all interrelated and may allow for going back and forth within this nonlinear process (Kreikebaum et al. 2018). The strategic management process is a framework that provides an orientation within the field but does not provide tangible guidelines. The boundaries between the individual process phases are blurred and fluid. Moreover, the conceptual approach is a neutral consideration of strategic management elements and disregards emotional aspects. The central premise of rationality (i.e., the actors will only focus on coherent objectives without any emotional components) has been criticized (Mintzberg 1978; Neumann 2017; Shiller 2019; Simon 2012; Thakur and Sinha 2020).

In addition, Fahey and Narayanan’s (1986) macro-environment analysis process is a framework that has no universal validity in research. Therefore, reference to these constructs is a limitation because there is no consensus on the “correct” form of these frameworks. Each family firm has its own way of viewing SEW, following a strategic management process, or performing a macro-environmental analysis. Nevertheless, these constructs appear to be a solid foundation for integrative considerations in this paper.

The number of scholars involved in this study is also a limitation because of the qualitative nature of the conceptual synthesis of the review. The conceptual matrix and inductive categorization rest upon selectiveness, as one scholar coded the core ideas within the developed pattern of two constructs. Despite a thorough methodology following Mayring (2015), the reader of this paper shall account for this limitation. However, frequent discussions with other scholars have provided a sound basis. Moreover, the methodologies and findings of this study have been challenged at research conferences. Nevertheless, although our intra-coder reliability was 95.6%, we acknowledge that there are different ways to classify research and that we are limited in our subjectivity (Swab et al. 2020).

While narrowing down to specific categories allows for an in-depth investigation, it also limits the examination to core areas. The focus on the strategic management process phase of the Analysis & Forecast does not mean that the other phases do not offer a variety of objects for further research. These fields also hold potential because the articles that have been analyzed have a specific focus and do not add up to a conclusively researched field. For instance, the consideration of external analysis does not stand in the way of an examination of internal analysis.

9 Conclusion

The many facets of SEW make it difficult to determine the touchpoints of nonfinancial goals in the strategic management of a family business. Apart from the identification of overlaps between SEW and strategic management, there is a lack of clarity and transparency (Brigham and Payne 2019; Swab et al. 2020). Thus far, no tangible links have been captured between SEW and strategic management. Consequently, this study provides a way to understand how the prevalence of the three SEWi dimensions unfolds in the strategic management process. Consequently, we propose a new understanding of this interrelationship and lay the groundwork for future research.

First, this paper discovers multiple research potentials in the overarching field of SEW in the context of strategic management. The content analysis of 169 research publications reveals that all SEWi dimensions are evenly connected with aspects of strategic management. However, phases of the strategic management process such as Target Planning or Formulation & Evaluation have a salient prominence in the research community. This can be explained by the close connection between the appraisal of family business goals (Williams et al. 2018) and SEW. In contrast, the phase in the strategic management process of Analysis & Forecast receives the least attention.

Second, we create a construct clarity (Brigham and Payne 2019; Suddaby 2010) in the overlapping areas between SEWi dimensions and Analysis & Forecast. We establish five categories of SEW influence that materialize cross-construct links with the strategic management of a family business. While the category Social Capital is closely linked to Family Prominence, so is Analytical Focus. This illustrates how relationships and social structures relate to decision-making in a family business (Zellweger et al. 2019). Family Firm Control and Internal Attributes of a family business are categories linked to Family Continuity. Reasons are the necessary control to maintain unity and values in the business as well as the effect of internal idiosyncrasies on management selection or inheritance. The category Goal Orientation is linked to Family Enrichment, supporting the pursuit of common family goals to fulfill the needs of family members. Particularly, trust between family members can enhance effective decision-making (Thakur and Sinha 2020).

Third, we develop an integrative framework for these five SEW categories and their influence on the macro-environmental analysis of a family business. This is due to the embeddedness of the family business in the external environment (Bansal and Song 2016; Bates 1985; Furrer et al. 2008) and its importance for effective strategic management (Mackay and Burt 2014). Our framework illustrates that all SEWi dimensions are related to three of the four activities of macro-environmental analysis. Family Prominence shows no relation to the activity of Forecasting (i.e., no publication discusses any projections of a family’s reputation or Social Capital that might be increased or reduced by actions of the family business). Family Continuity has no described link to the activity of Monitoring. This underlines that a family’s aspiration levels and the effects of family involvement are discussed, but there are no related trends. An example is the development from a family’s active management role toward a more passive investor family. Family Enrichment exhibits no connection to the activity of Assessing (i.e., none of the findings in this SEWi dimension create strategies to tackle environmental changes, such as ensuring family needs in external crises).

Two examples of the relationships between a SEWi dimension and an activity within the macro-environmental analysis illustrate this link. As one example, we find that Social Capital is a key determinant of Family Prominence, as stakeholder relations play a core role. Attention to Social Capital and the resultant web of relationships can lead to better information. This, in turn, may be a facilitating factor in the early scanning of the external world. As another example, we assign the category of Internal Attributes to the Family Enrichment dimension. Based on the study of related literature in the category of Internal Attributes, a possible homogeneity in the top management team of family firms becomes vibrant. This, in turn, may influence the ability of a neutral assessment (De Mol et al. 2015) of environmental changes. Thus, our framework allows scholars and practitioners to leave the level of abstraction and to fill the links between a SEWi category and an analytical task with exemplary content (i.e., we are enabled to further investigate specific nonfinancial factors that influence strategic Analysis & Forecast).

The above findings increase the awareness of the stimulating effect of SEW on strategic management in family businesses, particularly in the Analysis & Forecast phase. Furthermore, this paper lays the groundwork for a better understanding of the role of nonfinancial factors during macro-environmental analysis in family businesses. This enables a family business and its management to make better-informed decisions. The identified knowledge gaps provide promising opportunities for further research along the sweet spots between Family Prominence and Forecasting, Family Continuity and Monitoring, and Family Enrichment and Assessing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Aguinis H, Ramani RS, Alabduljader N (2018) What you see is what you get? Enhancing methodological transparency in management research. Acad Manag Ann 12(1):83–110. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0011

Aldrich HE, Pfeffer J (1976) Environments of organizations. Ann Rev Sociol 2:79–105

Ansoff HI (1975) Managing strategic surprise by response to weak signals. Calif Manag Rev 18(2):21–33

Arregle JL, Hitt MA, Mari I (2019) A missing link in family firms’ internationalization research: family structures. J Int Bus Stud 50(5):809–825. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00213-z

Astrachan JH, Jaskiewicz P (2008) Emotional returns and emotional costs in privately held family businesses: advancing traditional business valuation. Fam Bus Rev 21(2):139–149

Auerbach CF, Silverstein LB (2003) Qualitative data - an introduction to coding and analysis. New York University Press, New York

Bammens Y, Voordeckers W, Van Gils A (2011) Boards of directors in family businesses: a literature review research agenda. Int J Manag Rev 13(2):134–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00289.x

Bansal P, Song CH (2016) Similar but not the same: differentiating corporate responsibility from sustainability. Acad Manag Ann 11(1):105–149. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0095

Bates CS (1985) Mapping the environment: an operational environmental analysis model. Long Range Plan 18(5):97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(85)90207-9

Belenzon S, Patacconi A, Zarutskie R (2016) Married to the firm? A large-scale investigation of the social context of ownership. Strateg Manag J 37(13):2611–2638. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2441

Belenzon S, Shamshur A, Zarutskie R (2019) CEO’s age and the performance of closely held firms. Strateg Manag J 40(6):917–944. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3003

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR (2012) Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam Bus Rev 25(3):258–279

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR (2014) Family-controlled firms and stakeholder management: a socioemotional wealth preservation perspective. In: Melin L (ed) The SAGE handbook of family business, 1st edn. Sage, London, pp 179–195

Berrone P, Duran P, Gómez-Mejía LR, Heugens PP, Kostova T, Van Essen M (2020) Impact of informal institutions on the prevalence, strategy, and performance of family firms: a meta-analysis. J Int Bus Stud 53(6):1153–1177. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00362-6

Bertschi-Michel A, Sieger P, Wittig T, Hack A (2022) Sacrifice, protect, and hope for the best: family ownership, turnaround moves, and crisis survival. Entrep Theory Pract 47(4):1132–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587221118062

Block J (2010) Family management, family ownership, and downsizing: evidence from S&P 500 firms. Fam Bus Rev 23(2):109–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/089448651002300202

Boellis A, Mariotti S, Minichilli A, Piscitello L (2016) Family involvement and firms’ establishment mode choice in foreign markets. J Int Bus Stud 47(8):929–950. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2016.23

Boote DN, Beile P (2005) Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 34(6):3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006003

Brigham KH, Payne GT (2019) Socioemotional wealth (SEW): questions on construct validity. Fam Bus Rev 32(4):326–329

Brinkerink J, Bammens Y (2018) Family influence and R&D spending in Dutch manufacturing SMEs: the role of identity and socioemotional decision considerations. J Prod Innov Manag 35(4):588–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12428

Brunelli S, Gjergji R, Lazzarotti V, Sciascia S, Visconti F (2023) Effective business model adaptations in family SMEs in response to the COVID.19 crisis. J Fam Bus Manag 13(1):101–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-02-2022-0020

Buckley P, Casson M (2019) Decision-making in international business. J Int Bus Stud 50(8):1424–1439. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00244-6

Caiazza R, Cannella AA, Phan PH, Simoni M (2019) An institutional contingency perspective of interlocking directorates. Int J Manag Rev 21(3):277–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12182

Calabrò A, Minichilli A, Amore MD, Brogi M (2018) The courage to choose! Primogeniture and leadership succession in family firms. Strateg Manag J 39(7):2014–2035. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2760

Calabrò A, Frank H, Minichilli A, Suess-Reyes J (2021) Business families in times of crisis: the backbone of family firm resilience and continuity. J Fam Bus Stategy 12(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2021.100442