Abstract

Nonprofit organizations are critical actors in the Sustainable Development Goals as they provide a wide range of social services to the community and contribute to creating a sustainable future. They must compete for funding or government contracts by showing high social performance. Among the top factors influencing social performance is capacity, and it has received considerable attention in public and nonprofit literature. Capacity refers to the resources, capabilities, and practices required to perform their functions to achieve the social mission and high social performance. However, studies concerning capacity linked with social performance remain controversial. Understanding the linkage between capacity and social performance is relevant to funders, board directors, and management as it helps them enhance organizational performance. This research aims to assess the flow of knowledge in the study field and make recommendations for future research. The study focuses on capacity of nonprofits and thoroughly reviews the literature using complementary bibliometric analysis: co-occurrence analysis of keywords, sources, and authors and bibliographic coupling analysis of documents. We conduct a systematic analysis of peer-reviewed journal articles published between 1955 and 2022. Seven significant themes emerge among the most prominent researchers: (1) the link between capacity and social performance; (2) dimensions of capacity; (3) human resource capacity linked with social performance: (4) financial capacity linked with social performance; (5) capacity building linked with social performance; (6) collaboration and capacity; and (7) factors affecting capacity–social performance. The literature on nonprofits is determined to have inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between capacity and social performance. Research on various factors influencing capacity–social performance relationships is also scarce. This article highlights major principles in the discipline and identifies significant theoretical gaps in the body of knowledge. It also outlines the conceptual foundation for the study and makes recommendations for further research. From a managerial standpoint, the study sheds light on whether capacity is linked to higher performance levels and provides policymakers with guidelines on the implications of capacity building and collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, nonprofit organizations (from hereinafter referred to as nonprofits) have become significant players in social service providers worldwide. Nonprofits offer a wide range of services that the government and private sector cannot provide to the community. They play a role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in solving global issues to have a sustainable future (Svensson et al. 2018; World Health Organization (WHO) 2015) by providing social services that benefit their members or the community (Bromley and Meyer 2017; Brown et al. 2019; Shier and Handy 2015).

Conversely, nonprofits providing social services and solving social issues are in a vulnerable position in terms of sustainability due to their reliance on stakeholders, including donors, funders, and government agencies. They have to compete to get funds or government contracts by achieving high social performance (Hackler and Saxton 2007; Miller 2018). Social performance is an achievement in creating desired social value and target social mission. Social missions, such as aiding with the development of new programs and activities that address unmet needs (Bryan. 2017), developing public awareness and education to improve the community’s socio-cultural perceptions (Brown et al. 2019), and promoting health and peace (Millar and Doherty 2016; Sobeck and Agius 2007) provide benefit to the community. Thus, nonprofits need to provide a high level of social performance to gain funds, grants, or donations.

Nonprofits are demanded to achieve a high level of social performance to compete for funding or government contracts (Becker et al. 2020; Lall 2017). However, prior research has identified several factors that influence social performance, such as management practices (Amirkhanyan et al. 2014; Kim and Peng 2018), board directors’ characteristics (Dula et al. 2020), government support, leadership (Igalla et al. 2020), and organizational capacity (Gazley et al. 2010; Svensson and Hambrick 2016). Nonetheless, organizational capacity has become at the top of many factors influencing social performance (Cornforth and Mordaunt 2011; Daniel and Moulton 2017).

The capacity is nonprofits’ resources, capabilities, and practices required to generate outputs and produce results. The nonprofit literature on capacity emphasizes operational activities, including basic organizational infrastructure, as a defining capacity for goal attainment. In this perspective, the capacity is dedicated to the programs, services, and operations, such as volunteers, information resources, and collaboration with other players in the same fields (Bryan 2019; Misener and Doherty 2009). Capacity, as an enabler, includes program activities that enable the achievement of the mission and objectives (Despard 2017), information and program evaluation system (Minzner et al. 2014), and collaboration process (Campbell and Lambright 2017). In other words, capacity can serve as a possible precursor to accomplishing organizations’ objectives (Boyne 2003).

Capacity is required to generate outputs and produce results. In addition, according to resource-based and resource dependence theories, capacity refers to an organization’s resources, capabilities, and practices that enable it to acquire resources and the environmental factors that assist or hinder the acquisition of vital resources. A nonprofit needs to interact with other organizations in its surroundings to provide it with the necessary resources (Balestrini et al. 2021). To illustrate, nonprofits engage in transactions with other organizations and key stakeholders in their larger community, and organizations can raise funds, collaborate, and improve their reputation. Thus, capacity refers to the resources, capabilities, and practices required to perform their functions to achieve high social performance.

The literature has discussed the various concepts of capacity. Some studies have applied a resource-based theory in explaining the importance of capacity (Cheah et al. 2019b; Jain and Dhir 2021; Lee and Chandra 2020). Most scholars have discussed that capacity is multidimensional; however no consensus on the dimensions has been made (Christensen and Gazley 2008; Millar and Doherty 2021; Stuhlinger and Hersberger-Langloh 2021). The discrepancies are due to broad definitions, and the typical descriptions of capacity are resources and capabilities. First, capacity refers to the resources required for operational support to accomplish its functions (Bryan et al. 2021; Christensen and Gazley 2008; Shumate et al. 2017). Second, capacity refers to the capabilities to absorb and mobilize resources that specifically develop organizational capability (Bryan 2019; Jain and Dhir 2021; Zeimers et al. 2020).

Since late 2000, studies have examined the relationship of nonprofit capacity (hereinafter referred to as capacity) with social performance. The existing paper attempts to answer how capacity influences nonprofit performance (Hackler and Saxton 2007; Misener and Doherty 2009). For example, Hackler and Saxton (2007) examined the capacity’s focus on infrastructure and management capacities in using information technology to enhance social performance. They found the relationship between capacity and social performance, and the most vital capacity is management capabilities in planning and implementing information technology and training staff. The same findings were reported by Misener and Doherty (2009) after analyzing the effect of capacity on social performance in nonprofit community sports, in which management capabilities are a strength for the organizations. However, several studies have found that the effect of capacity on social performance depends on the size and the age of the nonprofit (Andersson et al. 2016; Kim and Peng 2018).

Notwithstanding, the perspicacity into the relationship between capacity and social performance is still sparse, and the results remain conflicting (Shier and Handy 2015). The difficulty in assessing this link demonstrates that the literature on the effect of capacity on social performance is not unanimous. The first difficulty is some problems in the concept and measurement of capacity and social performance. Second, in the debate concerning capacity and social performance, the literature less considers the interconnection among all dimensions in the organization: input–process–output-outcome. Moreover, the influence of capacity on social performance can be explained by other factors, such as the size and age of nonprofits (Guo 2007). Finally, a gap exists in the understanding of the capacity building outcome in enhancing social performance.

By using bibliometric and content analysis, Christensen and Gazley (2008) reported that no single discipline has optimized the variables, factors, and units of study available in measuring capacity. However, they used data of 2005 Thomson/Institute for Scientific Information, Web of Knowledge Journal Citation Report and focused only on the capacity at the managerial/ administrative level. In a recent bibliometric study, Lu et al. (2019) focused on the financial capacity relationship with financial performance. Walter (2020) examined the literature using scoping review, focusing on the capacity of the rural nonprofits in the USA. Likewise, a systematic literature review on capacity by Gazley and Guo (2020), specifically on collaboration, indicated a significant relationship between capacity and collaboration. The authors suggested greater emphasis on determining whether and when collaborative behavior is motivated by capacity. Nonetheless, we could not uncover precise data on organizational capacity and thus could not identify what type of capacity has the most significant relationship with collaboration and social performance. As a result, understanding the relationship between capacity and social performance is still vague.

In response to the research gap, this article aims to synthesize and analyze all existing studies, reconcile the observed inconsistencies in the literature, and discover topics on capacity. Therefore, we conduct a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis to understand the main context and the landscape of capacity. The nature of bibliometric analysis helps frame the following research questions: How was research concerning capacity evolved so far? Which sources published capacity studies? Who are the most prominent authors? Is it possible to identify a cluster of themes? Which theme of capacity needs further studies?

Our comprehensive evaluation of the literature, which included 1006 articles, gives an overview of the present level of knowledge on the subject. Subsequently, bibliometric methods identify the most influential authors and publications and their relationships and thematic groups. Research concerning capacity shows that studies on capacity began before 2000 but have gained momentum since 2006. In 2006, scholars discussed capacity building, leadership development, and community capacity. Since then, it has been growing every year. The top five most influential journals on capacity are Voluntas, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, Nonprofits Management and Leadership, Sustainability (Switzerland), and Evaluation and Program Planning.

In addition, a citation analysis identifies which papers have the most significant influence throughout various periods. Our study further reveals that developed countries, such as the USA, the UK, and Canada, are the most widely analyzed regions, and publications in the USA are the most cited and have (high) impact factors. Mapping reveals that the capacity field is growing, confirming Svensson et al. (2018). We also discover that researchers have shifted their attention from macro (social services contract performance) to the micro-level.

The thematic groups based on bibliographic coupling confirm a variety of disciplines involved in the field, including environment, economics, sociology, finance, and management. Some common themes emerge among the most prominent researchers, and we identify five thematic areas: (a) the link between capacity and social performance, (b) dimensions of capacity, (c) human resource capacity linked with social performance, (d) financial capacity linked with social performance, (e) capacity building and evaluation capacity, (f) collaboration and capacity, (g) factors affecting capacity–social performance, and (h) cluster evolution.

This study makes three contributions. First, we help scholars comprehend the topic as a whole, locate relevant papers, and uncover parallels and variances among distinctive types, the size of the nonprofits, and the country. Second, this study is the first attempt to organize and summarize the current body of evidence concerning the influence of capacity on social performance. On the basis of the content analysis, the study’s findings contribute to the existing body of knowledge on organizational capacity in nonprofits by describing the knowledge structure of the research topic and suggesting clusters of the most significant research directions. We offer new insight into capacity dimensions in different conditions to help the management and policymakers. Lastly, we identify research gaps and suggest future research directions to fill these gaps.

2 Method

This section follows the bibliometric analysis for business and management research guidelines by Block et al. (2020) and Block and Fisch (2020).

2.1 Methods and steps for conducting a literature review

We conduct a systematic literature review in finding studies on capacity. A bibliographic analysis is one type of systematic literature review, and it is widely applied for summarizing social science research (Block and Fisch 2020; Block and Kuckertz 2018). Given that journal articles are recognized as validated knowledge (Azam et al. 2021; Millar and Doherty 2016), we look for journal articles on organizational capacity and nonprofits. The process of searching for literature is divided into three phases: (1) phase 1 identification of article sources (stage 1, 2, 3), (2) defining and filtering of articles (stage 4) inclusion and exclusion criteria), (3) article recognition and retrieval (stage 5, 6). The seven-stage entails the process of coding, analyzing, and reporting the findings. Figure 1 depicts the strategy and steps used to conduct our systematic literature search.

2.2 Identification of article sources

We used those keywords in Table 1 to search from the Title–Keywords–Abstract in the Scopus database. For instance, Gazley and Guo (2020), Doherty et al. (2020), and Shumate et al. (2017) used “nonprofit.” In contrast, Hutton et al. (2021) employed “nonprofits” in their abstract and, similar to AbouAssi et al. (2019), used the term “nonprofits” in the titles of their articles. We used five keyword combinations from relevant articles (Table 1). In addition, capacity is linked to social performance as an input, output, and outcome related to the management system (Christensen and Gazley 2008). Therefore, the study attempts to examine capacity in business, management, and accounting fields for better understanding and richer information.

We selected Scopus for our literature search. Scopus is a comprehensive abstract and reference database for peer-reviewed literature (Böckel et al. 2021) as it consists of approximately 1.8 million cited references, 84 million records, 17.6 million authors, and 7000 publishers in diverse fields of knowledge. This research analyzes all sorts of articles that have been issued in the Scopus database. Using Scopus databases, we searched for articles containing combinations of the keywords mentioned in Table 1.

After searching for any combination of terms in the title, abstract, or keywords, this exhaustive search approach identified 5823 articles between 1955 and June 2022.

2.3 Screening and selection of articles

We defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the fourth phase (refer to Table 2). We ran a screening procedure on 541 articles to remove unnecessary or irrelevant databases based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Block and Fisch 2020).

We focused on peer-reviewed English articles published in journals. We excluded books, book chapters, review articles, conference papers, and editorial conferences, which are of limited use to our study (Block et al. 2017). All articles whose title, abstract, or keywords did not mention keywords in Table 1 were eliminated from our search results.

Next, we manually reviewed the abstracts of the remaining 2192 articles to ensure that the studies accurately concerned the capacity and nonprofits. Finally, we identified 1148 articles that were irrelevant to the study. Hence, 1006 articles from 1968 to 2022 met the current study’s criteria and were selected for further investigation.

2.4 Bibliometric analysis

The bibliographic analysis is used to visualize the intellectual structure of data. It includes author names, article titles, article keywords, article abstracts, journal names, and article publication years (Block and Fisch 2020). The bibliometric analysis aims to analyze and visualize the structure of the research field by categorizing the items (articles, keywords, authors, and journals). Hence, bibliometric analysis is beneficial to those who want to learn about a research field’s evolution.

We used bibliometric analysis to find the evolution of the literature on capacity. We conducted it in two steps. First, we provided a descriptive overview of the literature on capacity based on data from the Scopus database (1006 articles). Second, we used two bibliometric techniques for occurrence: keyword and co-citation analyses (Simao et al. 2021). According to the fundamental premise of keyword research, an author’s keywords or words used in papers’ abstracts can sufficiently reflect the substance of an article. We used this technique to discover thematic clusters. Citation analysis was conducted to determine the most influential articles, authors, and journals (Zupic and Čater 2015), and an examination of co-citation counts was used to determine how closely related two documents are to each other (Small 1973). We used 1006 articles from the Scopus database, and we conducted a co-citation analysis using VOSviewer, a program commonly employed in bibliometric studies, to determine the networks of relationships between researchers and journals (Zupic and Čater 2015). We conducted frequency counts on the articles in the identified clusters to select suitable thematic labels for analysis for interpretation purposes.

3 Descriptive analysis

This section provides an overview of descriptive research on capacity. We present how articles have evolved through time, and the most influential publications (based on citation) are highlighted. Furthermore, we find the most influential articles and the most often analyzed capacity.

3.1 Articles by years

This section answer question: How has research concerning capacity evolved so far? The analysis of the article's trend shows the capacity field's evolution. Figure 2 illustrates the annual article count to track the field’s development. According to the data, research on nonprofits and their capacity is a considerably modest topic between 1968 and 2005 (90 articles). Approximately 4% of the articles related to capacity were published before 2000. Around 5% of the articles were published during 2000–2005, and 14% were published during 2006–2010. Approximately 23% and 39% of nonprofits’ capacity articles in the Scopus dataset were published from 2011 to 2015 and 2016 to 2020, respectively. In 2021 and 2022, the number of publications on the capacity increased by 16% in two years.

Since 2006, constant rise in the study on capacity with small volatility. As illustrated in Fig. 2, 136 articles were published between 2006 and 2010. Even though there was a decreased number of articles in 2008 (11 articles), 14 articles in 2012, and eight articles in 2018, the research on nonprofits' capacity articles increased by 23% in five years (2018–2022). Furthermore, 109 articles were published in 2021, making 2021 the most productive year.

Capacity has become a core topic for social responsibility studies and third-sector research discussions. In the field, more attention has been paid to capacity in the sustainability and performance of nonprofits. As shown in Fig. 2, the number of articles in the literature on capacity increased beginning in 2006, after the UK policy report published in 2002 concerning the need for intervention from the UK government to enhance capacity (Cairns et al. 2005) and changing in nonprofit governance (Gazley and Nicholson-Crotty 2018). In comparison with the UK, the research on nonprofits in the USA was due to the rapid growth of nonprofits (Carman 2009; Svensson et al. 2018), increase in serving immigrants (Christensen and Ebrahim 2006), and post-natural disasters (i.e. D’Agostino and Kloby 2011; Simo and Bies 2007). From 2006 to 2011, articles discussed capacity building, leadership development, and community capacity. Since then, studies on financial capacity (Clausen 2021; Park and Matki 2021) have been growing.

Recently, more attention has been paid to various factors affecting capacity, such as organizational size (Millar and Doherty 2016; Svensson et al. 2018), type of service (Bauer et al. 2020; Brown et al. 2016), and nonprofit characteristics (Bauer et al. 2020; Singh and Mthuli 2021) and socioeconomic context (Badawi & Abdullah, 2022; Masson, 2015). Moreover, there exists increasing interest in the issues of the best practice for capacity building (Walters 2021), learning capacity (Gagnon et al. 2018; Hindasah and Nuryakin 2020), and collaboration capacity as a tool to obtain better performance and sustainability (Bauer et al. 2020; Fu et al. 2021; Kim and Peng 2018).

3.2 Most influential sources

This section answers the question: Which sources published studies on capacity? Table 3 lists the journals that have published three or more capacity-related articles. The final sample of this study includes 1006 articles from 195 publications. More than 30% of the 1006 articles were published in the publications listed in Table 3. Impact Factor, SCImago Journal Rank, and total citations of the identified journals are also shown in Table 3. From the table, Voluntas is the most productive journal with 49 published articles, followed by the Nonprofits and Voluntary Sector Quarterly; Nonprofits Management and Leadership; Sustainability (Switzerland); Evaluation and Program Planning; and Marine Policy with 40, 28, and 21 published articles, respectively. All the top three journals are impact factor journals: Sport Management Review, Land Use Policy, and Environmental Science and Policy.

The impact factor indicates the publication’s quality and the number of citations earned by articles in the journal (Block et al. 2020). According to 2021 Impact Factors, Sport Management Review (impact factor: 6.577), Land Use Policy (impact factor: 6.189), and Environmental Science and Policy (impact factor: 5.581) were among the top 20 journals with the highest impact factor in 2021. Only 3 of the top 20 journals were not listed in impact factor journals. Overall, 754 articles (75%) were published in impact factor journals in the entire dataset (1,006 articles). Scopus CiteScore can be used instead of the 2021 impact Factors to reach a close conclusion as follows. Environmental Science and Policy had the highest cite score (10.1), followed by Land Use Policy (9.9) and Sport Management Review (8.3).

The citations received by articles published in the top 20 journals are shown in Table 3. The current study used the Harzing and Perish program to calculate the total citation. According to Table 3, the articles published in the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly (citation = 1,260), Voluntas (citataion = 843), Nonprofit Management and Leadership (636), Sport Management Review (citation = 431), and Evaluation and Program Planning (citation = 351). Voluntas and Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly are considered the most prominent and influential journals in the discipline of nonprofits. American papers dominate in Table 3. A closer look at the aims and scope of each journal in the table reveals that the publications that primarily accept empirical articles have a higher share. Another essential point is the limited journal focus concerning the relationship between capacity and social performance. This statement is supported by Table 3, particularly the article in Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership, and Governance by Shier and Handy (2015).

3.3 Author profile

This section answers the research question: Who are the most prominent authors? Our sample’s 1006 articles were written by 160 authors. Table 4 lists the top ten current authors. Fu, J.S. from Rutgers University, USA, is the most active author in terms of contribution in the number of articles published, which are seven articles with 63 citations. However, Doherty, A. from the University of Western Ontario, Canada, contributed six articles with 284 citations. She was the highest cited author among the top ten authors. Doherty’s most cited article is “A case study of organizational capacity in nonprofits community sport,” with 165 citations published in the Journal of Sport Management in 2009. Another most cited article by Doherty is “Understanding capacity through the processes and outcomes of inter-organizational relationships in nonprofits community sport organizations,” published in Sport Management Review in 2003. One of these works is a case study, whereas the others are empirical articles. Hence, empirical research can contribute to developing the nonprofit research field. Scholars on capacity will also benefit considerably from Doherty’s study. Furthermore, the most active authors prior to 2012 were Burda, D (1992 to 2012) and Greene, J (1987–1997), both of whom have no new articles since then.

Furthermore, we found that out of 1006 articles, 695 (69%) are multiple authorship. The percentage might signify that the authors have a yearning and culture to collaborate in this aspect. The possible explanation for multiple authorship can be more of an absolute necessity than a choice. A researcher might find it challenging to conduct a study alone on the capacity field if his theoretical and methodological skills are limited. Moreover, researchers are more likely to collaborate with others if they have difficulty obtaining the data they need.

Different disciplines of study will focus on different contexts and dimensions of capacity. Based on the analysis of the authors’ profiles, the top five authors of nonprofit sports studies are Doherty, Breuer, Wicker, Misener, and Svensson. For capacity, authors in the human service and social service fields are Carman, Fu, Jaskyte, AbouAssi, Cooper, and Shumate.

3.4 Summary

In this section, we present the results of the descriptive analysis in identifying the evolution of the capacity field by examining the trend of published articles by years, the most influential sources, and the author’s profile.

The published articles show that capacity research began before 2000 and increased significantly from 2006 onwards. Since 2006, the number of scholars discussing capacity building, leadership development, and community capacity has been increasing yearly. More attention has been paid to various factors affecting capacity in the recent trend, such as human resources, funds, and nonprofit characteristics. Furthermore, interest in the issues of the best practices for capacity building, capacity outcome, management capacity, process management capacity, and collaboration and partnerships has been increasing.

The most influential journals on capacity based on 2021 Impact Factors, CiteScore 2021, and citations are the Public Administration Review, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Sport Management Review, Land Use Policy, Environmental Science and Policy, Climate Risk Management, and Marine Policy. However, the most active journals in publishing capacity are Nonprofits Management and Leadership, Voluntas, Sustainability (Switzerland, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, and Evaluation and Program Planning.

4 Bibliometric analysis

The results of the applied bibliometric analysis are described in this section. We aim to identify and corroborate the thematic cluster by revealing the most frequently used keywords (subtopics) and commonly cited studies (journals). This section answers the research question: Is it possible to identify a cluster of themes? Later, we disclose their networks in the literature on capacity. Therefore, we use four bibliometric techniques: (i) co-occurrence analysis of keywords, (ii) co-citation analysis by sources, (iii) co-citation by authors, and (iv) bibliographic coupling. All relevant bibliographical data for this study were obtained from the Scopus database, and the bibliographic software that we use was VOSviewer.

4.1 Co-occurrence analysis of keywords

Co-occurrence analysis of keywords identifies commonly used (key)words, assesses their association, and reveals patterns and trends in a research field (Simao et al. 2021). It is a technique for determining the relationships between concepts (words or subjects) in a document’s title, keywords, or abstracts. Furthermore, a co-occurrence analysis of keywords can also consolidate and organize current information on the topic and suggest potential study streams for future research (Zupic and Čater 2015). We used keywords instead of titles and abstracts because keywords can fully represent a study’s topic.

We used VOSviewer to conduct a co-occurrence analysis of keywords in our sample of 1006. Figure 3 illustrates the results of co-occurrence analysis of keywords in determining the relationships between concepts (words or subjects) in a document’s title, keywords, or abstract. We set the minimum threshold at five appearances; thus, a keyword had to be mentioned at least five times to be included in our analysis. A total of 101 items out of 2722 keywords had at least five appearances in our sample of 1,006 articles. However, we excluded “country,” “nonprofit,” “nongovernmental,” and “NGOs” from the 101 keywords to obtain the exact keywords regarding capacity. In total, only 68 items were included in our thematic analysis. We identified six clusters from the occurrence analysis of keywords. The most frequently used keyword is “capacity building,” which appears 48 times, followed by “governance”, which appears 31 times. Figure 3 illustrates the relatively moderate link strength between Group I (Nonprofits Management and Performance) and Group IV (Capacity Building).

We then conducted a co-occurrence analysis of keywords to find the thematic groups and identified eight groups. The result and keyword appearances in each group are summarized in Table 5. The groups are as follows: (I) Nonprofits management and performance; (II) Collaboration & Capacity Development; (III) Climate change and Dynamic Capacity; (IV) Capacity-Building; (V) Health & Education; (VI) Social Vulnerability; (VII) Governance & Innovation; and (VIII) Sustainable Development. The top five keywords are “human(s),” “capacity building,” “stakeholders,” “organizational capacity,” and “collaborations.” Looking at the keywords may be helpful in understanding where capacity knowledge is the highest. The highest keywords are in Group III (Capacity Building and Evaluation Capacity). Hence, human is the primary dimension in capacity studies (Misener and Doherty 2009; Swierzy et al. 2018a). Thus, the groups provide information on the significant capacity topics scholars have discussed.

4.2 Co-citation analysis

We also examined the journal and author co-citations to identify the intellectual structure of the field, which is used to find subject similarities between journal and author co-citations. Co-citation analysis refers to the frequency with which two studies, authors, or journals are mentioned in the same work (Small 1973). Based on this approach, co-citation data can identify groups of journals and authors using VOSviewer software.

4.2.1 Co-citation analysis at the source level

We determined that a journal had to be cited at least 50 times by the papers in our sample. A total of 52 journals met this criterion, as shown in Table 6 and Fig. 4. Six groups can be identified by analyzing the co-citation patterns.

Group I (in red) is the largest group and includes 13 journals, and of these journals, World Development and Development in Practice are the most cited ones. We labeled this group as Global Development, Science & Disaster as most journals are about global development research and theory, sustainable development, and science studies. Group II (in green) contains 11 journals. Academy of Management Journal and Administrative Science Quarterly are the most cited journals in this group. We labelled this group Organization, Management, and Ethical. Group III (in blue) includes five journals, and of these journals, Public Administration Review is the most cited one, followed by Journal of Public Administration. We labelled this group Public Administration & Policy. Group IV (in purple) contains four journals, such as Sport Management and Voluntas; this group is labeled Sport Management. Group V (in Yellow) includes the most-cited journal at the source level, the Nonprofits and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. We labelled this group Third Sector and Nonprofits. Group VI (in light blue) contains four journals. American Journal of Evaluation is the most cited journal in this group. We labeled this group the Evaluation and Program.

On the basis of the analysis, capacity topics are discussed in studies on management and strategy, public administration, sports, program evaluation, business ethics, and the third sector.

4.2.2 Co-citation analysis at the author level

Regarding the methodology underlying Sect. 4.2, the purpose of assessing co-citation analysis authors is to classify authors and create groups of fundamental research. We set that an author’s article had to be cited at least 30 times to be considered for inclusion in our study, and authors 86 authors from 46,117 met this criterion. A co-citation analysis identified four distinct groups (Fig. 5 and Table 7). The thicker the lines connecting authors is, the stronger the link between the authors in our data collection will be. Circles near the center of the citation network are more powerful, whereas circles further out are less powerful (Block et al. 2020). Our results show that Salamon, Doherty, Breuer, Gazley, Guo, Bryson, Carman, and Cousin are the most cited authors.

Figure 5 presents the analysis of co-citation analysis at the source level. Group I (in red) is labeled as Nonprofits and Public Administration. The most cited authors are Salamon, Guo, Gazley, Saxton, and Powell. Salamon is a prominent author in nonprofit studies as he received the highest co-citation. Several authors used Salamon’s definition of nonprofit such as Carman and Fredericks (2010), Shumate et al. (2017), and Von Schnurbein et al. (2018). The most frequent theories adopted in capacity are resource dependence theory, resource-based theory, institutional theory, agency theory, and stewardship theory. However, resource-based and resource dependence theories are typical in capacity studies (Brown et al. 2016; Bryan 2019; Choi et al. 2021). Group II (in green), labeled as Capacity Building & Partnership. The Group discusses partnership, health care, health system, and participation. The most cited authors in this group are Edwards, Hulme, and Lewis. Edwards, Hulme, and Banks (2015) claimed that NGOs can achieve their social objectives by strengthening their capabilities such as knowledge and operational ability.

Group III (in blue) contains authors discussing Public Affair and management, and performance. We labeled this group as Climate change and Governance. This group discussed on effectiveness, social innovation, conservation agriculture, organization performance, and capacity. Next, Group IV (in yellow), the group discusses capacity dimensions and subdimensions, such as human capacity, financial capacity, infrastructure, and board directors. The most cited authors in sports nonprofits are Doherty, Breuer, Wicker, and Misener. Misener and Doherty (2009) confirmed the importance of human resources, planning capacity, and development capacity in nonprofits, especially in sports nonprofits.

Lastly, Group V (in purple) has only five authors, and this group has two main focuses: evaluation capacity and research methodology; it is labeled as Evaluation and Methodology. Carman and Fredericks (2010) highlighted the barriers in evaluating capacity due to a lack of essential resources (examples: funds, people, and time), a limitation of evaluation expertise, and a lack of support for evaluation from the board of directors, staff, management, and donors. Hence, this study endeavors to gain more evidence in the literature, and capacity topics are discussed in management and strategy, public administration, sports studies, program evaluation, business ethics, and third sector studies.

4.3 Current trend analysis

This section uses bibliographic coupling to answer the research question: Which capacity theme needs further studies? In bibliographic coupling, two articles, A and B, quote the same article, C. It links papers mentioning comparable publications and analyzes documents as a unit. We set the cut-off point (the number of citations) in VOSviewer into 2, and out of 1006 documents, 848 documents met the requirement. Following chapters (4.3.1 to 4.3.7) review of the identified articles, eight clusters of emerging patterns were identified.

4.3.1 Link between capacity and social performance

This cluster focuses on the link between capacity and social performance. Social performance is an organization’s achievement in creating desired social values and achieving the social mission (Baruch and Ramalho 2006; Lee and Nowell 2015; Yang and Northcott 2019). The nonprofit social objective is to fulfil its social service, and commonly the government awards a contract to a nonprofit in the form of a contract (Van Slyke 2007). Social performance is essential for nonprofit survival and legitimacy (Daniel and Moulton 2017; Ebrahim 2003; Shier and Handy 2015). The nonprofit sector is increasingly concerned about enhancing its social performance by strengthening its capacity (Cornforth and Mordaunt 2011).

Various measurements for social performance are available, such as customer and beneficiary satisfaction (Baruch and Ramalho 2006; Kaplan 2001; Lee and Nowell 2015), the quality of services (Despard 2017; Lee. and Clerkin 2017a), social problems (Epstein and Yuthas 2010; Miles et al. 2014; Yang 2020), reputation (Shumate et al. 2017; Van Slyke 2007), fulfilment of the social mission (Battilana and Dorado 2010; Lall 2017), and action taken (Cuckston 2021). Among the modes that measure nonprofit performance is goal attainment theory, and it hints that capacity is needed for organizations to achieve their mission. Several authors who have attempted to study the relationship between capacity and nonprofit performance are Barman and Macindoe (2012), Bryan (2019), and Lee and Nowell (2015). However, they found mixed findings on the relationship between capacity and performance. Bryan (2019) asserted that capacity plays a role in achieving multidimensional organizational performance by looking at how performance is measured.

Another theory is the resource-based theory, which indicates that organizational resources refer to capacity and operation that contribute to organizational performance (Barney et al. 2011; Wernerfelt 1984). It stipulates that capacity is an essential element in staying competitive and will lead to higher performance (Barney 1991; Barney and Clark 2007). Thus, capacity can be considered a determinant of social performance to achieve a social mission. In this study, capacity refers to an organization’s abilities, systems and processes, and practices to achieve its social mission (Despard 2017; Fu and Shumate 2020; Shumate et al. 2017).

Existing studies have argued that capacity influences social performance, which is measured in terms of input, process, output, outcome (Amirkhanyan et al. 2018; Gazley et al. 2010; Lee and Clerkin 2017a), effectiveness, and efficiency (Bryan 2019; Misener and Doherty 2013; Pinheiro et al. 2021). At the same time, capacity needs to build (Bryan 2019; Christensen and Gazley 2008; Kim and Peng 2018), and capacity building may incur costs, such as training and professional staff (Cheah et al. 2019a; Mitchell and Berlan 2018). Building the capacity will be related to financial spending, reducing funds allocated to beneficiaries (Battilana et al. 2013; Cheah et al. 2019b). A study found that smaller nonprofits might have financial and time constraints to build their capacity (Kim and Peng 2018; Langmann et al. 2021).

Moreover, studies have suggested that capacity directly influences social performance (Fu and Lai 2021; Igalla et al. 2020). Nevertheless, capacity and social performance indicators, such as customer satisfaction and quality of service, may have a strong relationship (Lee and Nowell 2015), and the growing demand for nonprofit social services, including small nonprofits, signal the need to expand their capacity (Kim and Peng 2018). In other words, capacity must be built to meet the needs and demands of stakeholders. However, capacity building incurs costs or investments, such as new knowledge, infrastructure, and hired professional staff (Miller 2018; Stuhlinger and Hersberger-Langloh 2021; Zahra and George 2002). In addition, the changes in government tools, such as vouchers, evaluation, and accountability tools, also incur costs in strengthening their capacity (Fang et al. 2020; Wei 2020). Therefore, a possibility exists that capacity influences social performance after some cost or investment. This discovery also demonstrates that the relationship between capacity and social performance fluctuates, which provides new insight.

Conversely, following and fulfilling the social contract by implementing government tools will help improve the nonprofits’ social performance indicator, namely, customer satisfaction (Kim 2010; Willems et al. 2016). Another social performance indicator is the number of beneficiaries reached by the nonprofit in the evaluation tools (Lall 2017). As the government uses the indicator as a monitoring mechanism, a nonprofit may focus on distributing and collecting vouchers. As the government is satisfied with the nonprofit’s performance, it will increase the chances of receiving grants (Kim et al. 2019a; Mitchell and Berlan 2016). These findings may help explain the level of social performance objective achievement.

Studies on capacity are at the infant stage for boundary-spinning research, such as collaboration capacity. for developed countries, such as the USA and Germany. We identified the capacity development and building pattern in developed countries (Bryan et al. 2021; Cuckston 2021; Doherty et al. 2020; Hanlon et al. 2019; Millar and Doherty 2021; Svensson et al. 2017, 2020). Furthermore, the most prominent authors in capacity have focused on sports management, sustainability, and development. Some of the authors have attempted to explain the sports nonprofits organization problems by examining resources and capabilities (Andersson 2011; Doherty et al. 2020; Millar and Doherty 2021; Misener and Doherty 2009; Svensson et al. 2017, 2020; Svensson and Hambrick 2016; Swierzy et al. 2018b; Wicker and Breuer 2013).

Although understanding the relationship between capacity and social performance indicators is critical for management, funders, and governments, attempts to answer how capacity influences nonprofit social performance have been unsuccessful. Insights into the relationship between capacity and the social performance of nonprofits are lacking and contradictory. Moreover, a significant gap exists in understanding how the ability to measure capacity affects nonprofit social performance in developing countries.

4.3.2 Dimensions of capacity

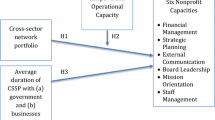

This cluster synthesizes articles concerning the measurement of capacity that affects their performance. The concept of capacity is broad and multidimensional. From the resource-based perspective, capacity is an input, process, and output, which indicates that capacity is organizational resources (Barney 1991; Christensen and Gazley 2008; Sobeck and Agius 2007). Capacity is an organization’s ability to perform its objective, with the ability to gather resources playing the critical part; thus, capacity is an organization’s capabilities (Brown. 2016; Bryan. 2019; Daniel and Moulton 2017). Resource dependency theory posits the pivotal role of obtaining adequate resources from the environment to enhance an organization’s ability to achieve its mission (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). Thus, capacity is how nonprofits provide services to achieve their social performance, and capacity is multidimensional (Bryan 2019). We identified capacity dimensions and subdimensions, as shown in Fig. 6. Capacity has two main dimensions, resources and capabilities, and six subdimensions.

Capacity is organization resources that refer to the input. The first and most prevalent capacity dimensions are human and financial resources. Human resource capacity refers to the board directors, executives, staff, and volunteers (Gazley and Nicholson-Crotty 2018; Moldavanova and Wright 2020; Stuhlinger and Hersberger-Langloh 2021). Human resources can be measured using the numbers of paid staff or volunteers (Carman 2009; Wicker and Breuer 2013) or using attitudes, competency, expertise, capabilities, and leadership (Cairns et al. 2005; Wicker and Breuer 2011). Another type of resource is financial resources, which can be measured using the size of the budget, financial reserve, amount of funds, and cash by looking at financial data (Christensen and Gazley 2008; Feiler and Breuer 2021; Swierzy et al. 2018a). Some studies have used a management perspective to measure financial capacity, such as the sufficient amount of funds (Brown et al. 2016; Sowa et al. 2004). Another dimension of the capacity of organization resources is infrastructure.

Several authors have referred to infrastructural capacity as technical capacity (Lee and Clerkin 2017b). Infrastructural capacity reflects the information technology, communication system, and physical infrastructure for achieving the nonprofit mission (Hall et al. 2003; Lee and Clerkin 2017b). For sports nonprofits, infrastructure capacity refers to the facilities to provide sports programs (Swierzy et al. 2018a). Sports nonprofits are expected to have a facility and need to maintain to be in good condition. The quality and the quantity of the facilities are linked to the volunteers performing their responsibilities (Misener and Doherty 2009). Others have indicated that infrastructural capacity refers to organizational structure, information technology, and communication systems. Information technology and communication systems are needed for daily operations to capture and analyze data and keep track of the programs (Christensen and Gazley 2008; Lee and Ng 2020). In recent case study by Riegel and Mumford (2022) has revealed that physical capacity constraints hinder nonprofits' access to the legislative process. Hence, infrastructural capacity is a facility, technology, and system for an organization in performing its task to achieve its objective. From this view, capacity, as an organizational resource, is required to fulfil the organization’s objectives.

Next, capacity is organization capabilities. First, management capacity is the ability to manage internal organizations and enhance organizational performance (Despard 2017). Management capacity is an ability to create and deploy organizational resources and operational aspects to improve social performance (Brown 2005; Hall et al. 2003). Moreover, management’s ability to operate effectively through applying processes, practices, acquired knowledge, planning, and supporting structures is needed to perform their mission and objectives (Hall et al. 2003; Svensson and Hambrick 2016), as well as the ability to establish relationships and network with members, clients, funding agencies, the government, partners, the media, the general public, and corporations. The nonprofit must have management capacity such as negotiation ability to negotiate with various stakeholders such as the public and government (Oliveira & Hersperger, 2018). Other management capacity dimensions are the ability to create long-term planning and strategic plans (Bryan et al. 2021; Misener and Doherty 2009). Moreover, Berrett (2022) found that. A growth in management capacity expenses (salaries, professional fees, marketing, and system) mediates a positive relationship between the overhead ratio and the success of nonprofits. However, capacity in management is staff, financial, and project management (Ebrahimi et al. 2021), which are interchangeable. Thus, management capacity is the management’s ability and capability to plan, manage, and implement resources and activities to achieve the social mission.

The next dimension of capacity is dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities are defined as an organization’s ability to integrate, build, and restructure internal and external skills in response to quickly changing conditions (Teece 2007; Zahra and George 2002). Dynamic capabilities have three components: absorptive, adaptive, and innovative capacities. Absorptive capacity refers to the capacity of organizations to discover and utilize external knowledge and has a link with social performance. It finds a significant relationship with inter-organizational learning and organizational performance in short- and long-term projects (Biedenbach and Müller 2012) through human capital (Choi et al. 2021). However, costs are incurred in gaining knowledge, which leads to performance differences among nonprofits (Zahra and George 2002).

In a study of the relationships between the sources of innovation and the performance of Chinese nonprofits, Chen et al. (2017) found that the absorptive capacity (working attitude) mediates the relationships between innovative sources and performance, including social performance. Compared to Chen et al. (2017), Unceta et al. (2017), found that nonprofits in Spain require a certain level of absorptive capacity to absorb, transform, and utilize external knowledge using internal knowledge, and to integrate with the governance mechanisms for social innovation projects. Furthermore, the nonprofit absorptive capacity helps to produce and maintain information is will enhance the achievement of social performance (Dobson and Turnbull 2022; Ludvig et al. 2018). By contrast, Choi et al. (2021) found that prior social experience (dimension of absorptive capacity) has a positive connection with social performance.

Another component of dynamic capabilities is adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity refers to the capacity to monitor, analyze, and adapt to internal and external changes; this capacity requires technical ability in tandem with culture, which involves environmental change (such as risk), market opportunities (Banjongprasert, 2022; Biedenbach and Müller 2012; Bryan et al. 2021; Pinheiro et al. 2021) and marine conservation (Cadman et al., 2020). Empirical evidence indicates that adaptability improves performance with technological advances, and one can get less adaptive capacity through collaboration (Biedenbach and Müller 2012). Several researchers have argued that one way to embrace the changes is in adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity is the company’s ability to respond to environmental changes. Fu and Shumate (2020) described adaptive capacity as a culture in which nonprofits share ideals and supportive culture and its ability to settle disagreements and work collaboratively to solve challenges. They found that nonprofits in China have lower adaptive capacity than in the USA. The measurement probably conjures up notions of a flat organization, which will contradict Chinese hierarchical culture.

Concerning environmental issues, a previous study claimed that nonprofits require the adaptive capacity to enhance the governance of the environment. Adaptation capacity is needed to increase the effectiveness of actors’ operations and deal with change. Components of adaptive capability include learning and evaluation, coordination and collaboration, responsiveness and restructuring, and accountability (Banjongprasert 2022). However, the nonprofits lack capabilities in policy development and decision-making that make them less effective in environmental governance (Petersson 2022).

The last dynamic capability is innovative capacity, which refers to improving or replacing existing services or products (Jaskyte 2017; Zeimers et al. 2020). Nonprofits are expected to have the innovative capacity as contractors of government social contracts (Osborne and Flynn 1997) and embrace the economic situation (Doherty et al. 2020). Moreover, most of the studies on the social entrepreneurship orientation of nonprofits (such as social enterprises) indicate that innovative capacity affects social performance (Miles et al. 2014; Pinheiro et al. 2021).

In conclusion, we argue that capacity is complex, and any attempt to find a consensus on capacity dimensions has been unsuccessful. One could raise a question; do different social objectives require different capacities? Thus, insights into the relationship between capacity and the social performance of nonprofits are scattered, resulting in an incomplete picture that requires additional research.

4.3.3 Human resource capacity linked with social performance

This cluster synthesizes articles indicating the dimensions and challenges concerning capacity that affect organizations’ performance. Capacity refers to organizations’ abilities, systems and processes, and practices to achieve its social mission (Despard 2017; Fu and Shumate 2020; Shumate et al. 2017). Human resources are people whose management can plan and execute its deployment strategy and effectively manage training and development for professionalism (Lee 2020). Previous studies have asserted that volunteers are the most crucial human resource to nonprofits, and their capacity is vital in achieving organizational social missions (Hall et al. 2003). Volunteers’ capacity refers to the number of volunteers, including team leaders and supporting staff (Brown et al. 2016; Bryan 2019; Christensen and Gazley 2008). Contradicting evidence by Vandermeerschen et al. (2017) showed that human resources are not the main capacity for a member type of nonprofit in achieving its objective to serve the community. Nevertheless, nonprofit management must integrate professional management methods by tailoring their approaches to meet volunteers’ unique requirements.

Various research studies have highlighted the importance of tailoring human resource management that fit volunteers’ capacity needs, such as effective recruiting and selection, training and development, and recognition of volunteers (Akingbola 2006; Carvalho and Sampaio 2017; Swierzy et al. 2018a). The more recent approach is the Volunteer Stewardship Framework for managing and administering volunteers (Brudney et al. 2019). Although these studies demonstrated the critical role of human resource practices in determining volunteers’ capacity, a more comprehensive understanding of all management procedures affecting volunteers’ ability is required to enhance this capacity effectively. De Clerck et al. (2021) used the Competing Values Framework to identify and categorize critical management practices in nonprofit volunteers’ capacity. The researchers found that management processes (human relations model, rational goal model, internal process model, and open system model) positively influence volunteers’ capacity. Management processes (human relations model, rational goal model, internal process model, and open system model) are strongly associated with volunteers’ capacity. The authors indicated that management in nonprofits must focus on all four management processes in the Competing Values Framework to maximize their volunteers’ capacity rather than only specific human resource procedures.

Human resource practice with sufficient staff and volunteers is vital to staying competitive and achieving high social performance. Human resources are essential to nonprofits, as governments rely upon their assistance with a wide variety of public issues, including those that arise during and soon after a disaster. For example, in the UK, the Salvation Army worked with the government to assist the most vulnerable citizens during the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak (Waardenburg 2021). In providing assistance and social services, nonprofits need an adequate number of people (Carman 2009; Wicker and Breuer 2013) with positive attitudes, expertise, abilities, and a sense of trust and shared ideals to conduct the activities and programs and run operations successfully in achieving their social missions (Hong et al. 2022; Misener and Doherty 2009). This idea is confirmed by Svensson and Hambrick (2016), who examined the capacity of nonprofit sports organizations in East Africa. The authors found that human capital is crucial to social performance in small sports organizations. However, numerous nonprofits experience challenges extending their volunteers’ capacity, affecting the performance of their social services (Carnochan et al. 2014; De Clerck et al. 2021; Miller 2018).

Along with extending the volunteers’ capacity, nonprofits face challenges concerning human resource professionalism, such as competency and skill, and difficulty attracting volunteers, staff, and board members (Bryan 2017; Misener and Doherty 2009). Researchers have indicated that nonprofits need more professional staff and volunteers (De Clerck et al. 2021; Misener and Doherty 2009). By contrast, for sports nonprofits, professionalism is a process of being a professional where the youth starts as a member of the sports club. They can become qualified and professional coaches with talent development (Waardenburg 2021). However, the problem arises in recruiting and keeping members. For example, sports nonprofits face challenges attracting and retaining adult and junior members, female board members, and volunteer engagement to achieve their social mission (Wicker and Breuer 2013) and recruit active members (Waardenburg 2021).

Another stream on human resources is related to the board of directors. This cluster focus on the board levels of involvement in service innovation linked to the organizations’ performance. Nonprofits work to solve social problems in their communities and constituents. The board plays a crucial role in strengthening the capacity of nonprofits. Therefore, nonprofit boards must enhance their capacity and ability (Brown 2007; Epstein and Yuthas 2010; Jaskyte 2015; Kim and Peng 2018). The demand from the government and public for greater effectiveness in nonprofit social service, which necessitates nonprofits to be innovative, is increasing (Jaskyte 2015, 2017). Service innovation, also known as innovation, is defined as introducing products, processes, new concepts, services, systems, structures, or techniques into an existing organizational practice to solve social problems (Jaskyte 2017; Shier and Handy 2015; Winand et al. 2013).

Introducing new services to meet the needs of members and the community is a form of service innovation (Winand et al. 2013). Different types of nonprofit respond to innovation differently. To illustrate, Winand et al. (2013) claimed that the traditional nonprofit style is less innovative than the competitive nonprofits. There exists a greater emphasis on service innovation in competitive nonprofits to secure funds, which drives up the demand for innovation and staff participation in decision making. The more nonprofits focus on service innovation, the more likely they are to establish networking (Daniel and Moulton 2017).

Capacity at the board director level refers to (1) competency (knowledge and expertise), (2) attitude, (3) diversity, (4) commitment and involvement, and (5) size. Findings on the boards with professional expertise and community experience are more likely to develop service innovation techniques for resolving social problems (Doherty et al. 2020; Hinna and Monteduro 2017; Jaskyte 2015). Moreover, the board attitude favoring innovation has been linked to service innovation. Winand et al. (2013) found a high regional competition level and a good attitude toward change and innovation in nonprofit sports encourage social innovation. By contrast, Lee and Clerkin (2017a, b) claimed that the boards’ attitude in executing appropriate service innovation is institutional pressure. Board directors are diverse in gender (Gazley et al. 2010; Hinna and Monteduro 2017), expertise (Gazley et al. 2010; Hinna and Monteduro 2017; Jaskyte 2015), and race (Gazley et al. 2010). The board capacity contributes to the organizational performance through service innovation.

The prior research has indicated that board diversity influences new ideas in improving service quality (Gazley et al. 2010; Miller et al. 2003). Similarly, Hinna and Monteduro (2017) suggested board diversity increases the nonprofits’ social innovation. Conversely, Jaskyte (2015) claimed that the downsides of having extremely diverse board members are on social innovation. Lastly, the board commitment and involvement in planning, acquisition, and implementation, such as information technology and social innovation decision making, will enhance organizational innovation capability (Hackler and Saxton 2007; Hinna and Monteduro 2017).

Among the board's roles is to monitor management issues, finances, and operations. The commitment of board directors to monitor management functions and tasks affects the organizations’ ability for innovation (Jaskyte 2017, 2018). For board size, Brown (2005) found that the size of the board has no relationship with the board size and the overall organizational performance. By contrast, Jaskyte (2018) indicated that small boards will effectively monitor organizational performance, especially on social innovation. The effect of the board capacity on organizational performance is considered crucial in monitoring and deciding on service innovation linked to organizational performance. Some authors have contributed to the existing capacity at the board level by concluding the board roles in social performance. However, research on the association between the capacity at the board level and social performance is still lacking.

Lastly, human resource capacity issues also exist in the individuals and communities being served. Another capacity research stream focuses on individuals and communities in terms of human resource capacity, such as indigenous and poor people (Chu and Luke 2020; Westmont 2021). For instance, Westmont (2021) explored small-scale farming operation that helps enhance indigenous people’s capacity, environment, and tourism sustainability within the tourism sector in rural Cusco, Peru. He found that indigenous people need to build capacity and empower women especially to create sustainable tourism. He indicated that the nonprofits focus on human capital, such as knowledge and skills, with the aid of technology, training, and natural resources. He asserted that NGOs need to increase people’s capacity to market their products (Westmont 2021). With a competitive advantage such as uniqueness, indigenous people can enter the niche market. These findings indicate that human resource capacity research is diverse and focuses not only on internal nonprofits per se.

Human resource capacity is crucial to nonprofits in maintaining their competitive advantage and high performance. However, there still exists a debate on the appropriate human resource practices, challenges in keeping volunteers, and developing professional volunteers. Although the influence of human resource capacity on social performance is regarded as a critical dimension in nonprofits, previous research has revealed some inconsistencies. Philip and Arrowsmith (2021) stated that although volunteers’ capacity is essential, there exists a risk of a high turnover due to various challenges affecting nonprofit performance to understand this inconsistency better. Furthermore, the main barrier to sports is the sports federations and local sports authorities (Vandermeerschen et al. 2017). As a result, nonprofits require additional capacity to mitigate the threat posed by human resource capacity. Generally, many scholars have contributed to existing capacity studies by drawing essential conclusions about the role of human resource capacity, which may differ depending on the nonprofits’ social missions.

4.3.4 Financial capacity linked with social performance

Another primary capacity is financial capacity (Epstein and Yuthas 2010; Kim and Peng 2018; Shumate et al. 2017; Svensson et al. 2017), which refers to nonprofits’ ability to raise and utilize funds effectively (Hall et al. 2003; Svensson and Hambrick 2016; Wicker and Breuer 2011). Financial capacity also refers to nonprofits’ ability to attract financial resources, and it is crucial for solving community social issues (Shumate et al. 2017).

Nonprofits need financial capacity for their social mission and fulfil the stakeholders’ demands (Feiler and Breuer 2021; Kumi 2022; Lee 2020) and are vital to their operations (Hutton et al. 2021). Some studies have found that a more stable financial capacity will increase the effort to strengthen human resource capacity (AbouAssi and Jo 2017). Nonprofits require funds for salary, maintenance facilities, and other operational expenses. However, previous studies have asserted that nonprofits in developed and developing countries face funding insecurity, which leads to resource shortages (Battilana and Dorado 2010; Wicker et al. 2015; Zhou and Ye 2019). Hence, insufficient funds have adverse effects on nonprofits’ social performance (Stuhlinger and Hersberger-Langloh 2021; Walters 2020).

The concern about nonprofit social performance has been growing, which seems to be related to financial capacity. Some studies have found that nonprofits that receive funds from the government and funders have less financial autonomy (Zeimers et al. 2020). They have to follow the contract in which the funds are allocated and spent for a specific social objective. However, the budget for building and developing capacity is limited and will increase nonprofits’ expenses (Čada et al. 2021; Cazenave and Morales 2021). The increasing cost on others than what funders or government contracts stipulated might cause the nonprofits not to be elected for future funding (Cazenave and Morales 2021). Thus, some scholars have suggested that nonprofits are involved in projects with immediate and quantifiable rewards, such as money (Stuhlinger and Hersberger-Langloh 2021), which may seem a good idea.

The risk of reducing funds or unselected for future funds might not be the most considerable challenge to some nonprofits. Among the challenges for financial capital in nonprofits are lack of funds, limited funding mechanisms, and new policies (Berner et al. 2019; Millar and Doherty 2018; Svensson and Hambrick 2016). For example, in a recent study on summer meal program, Berner et al. (2019) claimed that nonprofits face issues with the policies set by agencies, such as new regulations on background checks for recipients, which incur additional costs. By contrast, in previous studies, financial capacity and government grants do not affect nonprofit social services, such as reducing underprivileged people’s economic and sociocultural barriers (Vandermeerschen et al. 2017). In another study on higher education capacity, previous research has found that a country’s financial capacity is one of the factors for research capacity for higher education. The higher the economics of the government is, the larger the fund allocated to higher education will be (Marginson 2006). In other words, financial capacity linked to social performance is diverse.

Moreover, in recent years, disasters have become more frequent, which has resulted in a more unstable working environment for organizations. As the key providers of services to communities, nonprofits participate in and interact with governments for the community’s wellbeing, including during disasters (Chen 2021b; Hutton et al. 2021). Regardless of their size or severity, disasters can undermine organizations’ growth and social performance. Therefore, nonprofits need to equip their resilience, which indicates companies’ capability to prepare (Fu and Lai 2021) and recover from disruption and perform (Chen 2021a, b; Hutton et al. 2021). Three types of capacity are social media communication, collaboration, and external communication essential in increasing humanitarian NGOs’ efficacy and efficiency in disaster risk sreduction operations.

By contrast, different capacities are needed in post-disaster recovery due to property damage, employee loss, and changes in the scope of their services. The most crucial capacities are financial and human resources to recover from the disaster (Chen 2021a, b). However, most nonprofits do not have a financial reserve to recover and fail to develop sound procedures for recovering from staff losses, resulting in a drop in demand for their services. Interestingly, organizational learning aids in recovery from a second disaster based on experience.

Nonprofits’ financial and human resource capacities are inextricably linked. Bryan (2019) found that the more access to financial capacity is, the more staff and the more budget will be allocated to conduct social activities the nonprofits can produce for their community. The more nonprofits’ ability to generate multiple sources of money, the more budget the nonprofit will be able to allocate to conduct social activities with more staff (Bryan 2019; Wicker and Breuer 2013). The last element of resources is tangible infrastructure, such as facilities mainly for sports nonprofits and nursery homes (Amirkhanyan et al. 2018; Wicker and Breuer 2011).

Hence, on the basis of this finding, the three levels of financial capacity are (1) nonprofit, (2) community, and (3) country, which directly influence social performance. Although the relationship between financial capacity and social performance has been identified, which level of financial capacity is most important for a social mission remains a question.

Studies have established that the capacity dimension of human and financial resources is crucial for nonprofits to achieve their missions and objectives. The nature of the capacity and organizational performance is different as differences exists across nonprofit activities and programs. For example, nonprofit sports organizations require more skilled and professional coaches and better facility management and generate revenues to achieve their missions and objectives (Doherty et al. 2014; Wicker et al. 2018). However, human service nonprofits require skilled and competent management and staff in delivering programs and maintaining human relations (Berner et al. 2019; Lee and Clerkin 2017a). For human service nonprofits, involvement with entrepreneurship has caused them to drift from their missions. Thus, there still exist questions about overcoming nonprofits’ challenges with limited resources and lack of ability. Other questions are how far the challenges affect the organizations’ performance.

4.3.5 Capacity building linked with social performance

This cluster synthesizes articles discussing capacity building related to social performance. The United Nations Development Program explained that capacity building is how organizations, societies, and individuals acquire the capabilities necessary to achieve their own development goals (UNDP 2009), and capacity building initiatives target one or more of these levels. Capacity-building programs may target specific individuals inside a nonprofit through training or leadership development activities, the organization as a whole, or the organization's programming (Bryan 2017; Kearns 2004). The benefits of capacity building are increasing the organizations’ competitive advantage, which helps distinguish them from competitors and make them more appealing to governments, funders, and society (Mason and Fiocco 2017).

A specific emphasis has been placed on defining the exact capacity needs (Svensson et al. 2017), specific initiatives to increase capacity and influence (Cornforth and Mordaunt 2011; Faulk and Stewart 2017; Minzner et al. 2014), organizational readiness in capacity building (Millar and Doherty 2016, 2018), capacity-building efforts hampered by various difficulties (Faulk and Stewart 2017), and, recently, the consequences of capacity building and the outcomes of those initiatives (Millar and Doherty 2021). Hence, understanding of effective capacity building in the current literature, primarily concerned with discrete aspects of the process, is lacking,

Nonprofits can improve their social performance through capacity-building activities, and the capacity-building efforts that address at least one of these dimensions can be found in the literature. Capacity building involves four levels: individuals, cohort groups, organizations, and communities (Bryan and Brown 2015). First, individual-level capacity-building involves a human resource capacity, such as trainings, workshops, mentoring, and professional development. Participation in capacity-building programs has increased knowledge and abilities; clarified roles, especially for the board and executive director; and increased organizational leaders’ strategic orientation (Bryan 2017; Choi et al. 2021). Empirical evidence of the influence of individual-level capacity building on social performance is lacking. Individual-level capacity building may be a moderator and interconnected with organizational level in the capacity–social performance relationship.

Next is capacity building at the group cohort level, which focuses on specific groups involved in the capacity-building program. This particular level is less discussed in the literature, possibly due to this level focusing also on human resource capacity (Bryan and Brown 2015). Group cohorts can be used in regional or sectoral approaches to capacity building. The regional strategy aims to improve public service delivery by fortifying selected nonprofits that comprise the service delivery network and enabling organizations to build a long-term learning system (Kearns 2004). However, given that most of the literature on cohort designs focuses on groups within an organization, group training may also be similar to cohort designs. Thus, group-cohort-level capacity building may enhance social performance, which is interesting to look further.

The most considerable discussion in the literature is capacity building at the organization level. Several authors have shifted focus to examine strategies for capacity building (Kearns 2004; Millar and Doherty 2018), process of capacity building (Bryan 2017; Packard 2010), the implementation process (Millar and Doherty 2016), the outcome of capacity building (Bryan 2019; Faulk and Stewart 2016), evaluation capacity building (D’Ostie-Racinea et al. 2021; Wade and Kallemeyn 2020), and readiness for capacity building (Millar and Doherty 2021). Scholars have worked to comprehend the stages of organizational capacity development. Misener and Doherty (2013) found that capacity building has improved organizations’ capacity. However, later, Millar and Doherty (2021) emphasized the importance of addressing the complexities of organizations’ immediate and long-term implications of capacity building. They raised the question of the influence of successful capacity building on the operation.

Lastly, capacity building at the community level. Many capacity building programs are targeted at the community. Few, if any, evaluations of capacity-building programs focus on them (Bryan and Brown 2015). Scholars of sustainable development have argued that a healthy nonprofit community contributes to a healthy community, leading to collective impacts. Most collective impact programs are primarily concerned with cross-sector collaboration and learning. Community-level capacity building mainly involves several organizations, such as consultants, nonprofits, and citizens (Caragata 2022; Tu 2021) and strengthening actors’ networking. However, how the outcome of the collaborative program will affect the community is unclear (Shea 2011). Bryan and Brown (2015) asserted that the cohort-group-level capacity building facilitates collaborative community learning and it could be related to program outcomes for the program's target populations (Aantjes et al. 2022). The question that arises is how the communities of practice are formed through capacity-building programs.

Existing capacity-building research is fragmented, resulting in an incomplete understanding. Organizational capacity-building research in the nonprofit sector typically focuses on specific stages of the process and one particular aspect of capacity development rather than acknowledging the interconnected complexity of the various stages of development (Millar and Doherty 2018). An investigation of the multilevel framework for capacity development in nonprofits discovered that the outcomes at each level are interconnected (Bryan and Brown 2015). Even there is an attempt to differentiate between building capacity at a different level. There is a dearth of understanding regarding successful capacity building and its contributing factors to performance (Cornforth and Mordaunt 2011; Millar and Doherty 2021). Hence, on the basis of the findings, existing capacity-building research is fragmented, resulting in an incomplete understanding of which need further study.

4.3.6 Collaboration and capacity