Abstract

In this article, we review recent archival research articles (98 studies) on the impact of corporate governance on restatements, enforcement activities and fraud as corporate financial misconduct. Applying an agency-theoretical view, we mainly differentiate between four levels of corporate governance (group, individual, firm, and institutional level). We find that financial restatements on the one hand and the group and individual level of corporate governance on the other hand are dominant in our literature review. Enforcement actions and fraud events as misconduct proxies, and the firm and institutional level of corporate governance are of lower relevance yet. The following review highlights that many studies on corporate governance find inconclusive results on firms’ financial misconduct. But there are indications that board expertise and especially gender diversity in the top management decreases firms’ financial misconduct. We know very little about the impact of non-shareholder stakeholders’ monitoring role on misconduct yet. In discussing potential future research, we emphasize the need for a more detailed analysis of misconduct proxies, recognition of moderator and especially mediator variables, especially in the interplay of the board of directors and external auditors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In light of prominent financial scandals (e.g., Enron, Worldcom, Wirecard), a proper financial reporting quality is crucial for stakeholder trust. Firm’s financial misconduct can lead to massive negative consequences for capital providers, employees, customers, suppliers and the whole economy. During the last years, many controversial discussions arise which mechanisms may prevent or even discover unethical and opportunistic behavior of firms. In view of this relevance, this systematic literature review focusses on archival research on the relationship between corporate governance and firms’ financial misconduct. In line with Amiram et al. (2018), we define firms’ financial misconduct as violations of national and/or international accounting and related business law regulations and standards. Thus, we make a clear distinction between earnings management and firms’ financial misconduct.Footnote 1 We are aware of the fact that discretionary accruals and related proxies for earnings management may be significant predictors of firms’ financial misconduct (Amiram et al. 2018), leading to a “grey zone” between earnings management and violations of accounting standards. While the US-American literature does not clearly separate between earnings management and violations, the Continental European accounting literature mainly stresses that earnings management is in line with the respective law and standards (e.g., Hirschler 2021). We refer to this assumption, exclude studies on the link between corporate governance and earnings management and refer to prior literature reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., Garcia-Meca and Sanchez-Ballesta 2009; Lin and Hwang 2010).

Referring to the corporate governance framework by Jain and Jamali (2016), we separate our corporate governance variables into four levels: group, individual, firm, and institutional level. We identify financial restatements, fraud events and enforcement activities as three main categories of firms’ financial misconduct, representing a major threat for capital markets (Brody et al. 2012; Hammersley 2011). We are aware of the fact that restatements are not necessarily the result of fraud, as unintentional errors may also result into restatements. Firms’ financial scandals lead to decreased trust between corporations, gatekeepers, market participants, and other stakeholder groups, because firms may go bankrupt or may have extreme financial problems if these scandals go public (Brody et al. 2012). There is empirical evidence that negative financial consequences, e.g., major losses in firm valuation, and increased capital costs, or higher executive turnover will follow (Habib et al. 2020). We note the famous Enron scandal and the insolvency of Wirecard, one of the former “DAX 30” fintech group companies in Germany, as prominent examples for a big loss in capital market trust. Many national and international legislators, e.g., the European Commission and the British Government, currently discuss future corporate governance regulations, e.g., whistleblowing systems or risk management tools.

According to the famous fraud triangle by Cressey (1953),Footnote 2 the possibility of firms’ misconduct is based on three conditions. First, incentives and pressures must be existent to commit misconduct. Second, there must be an attitude or a rationalization committing misconduct. Third, there must be any circumstance which provides an incentive or an opportunity for misconduct. Incentives or opportunities may be caused by ineffective monitoring of top management, complex organizational structures or ineffective controls due to a lack of monitoring of controls or circumvention of controls. In line with agency theory, internal and external corporate governance as monitoring mechanisms should decrease executives’ opportunities for financial misconduct. In a traditional sense, corporate governance “deals with the ways in which suppliers of finance to corporations assure themselves on getting a return on their investment” (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). As we also like to integrate other stakeholder groups, we refer to the corporate governance definition as “the combination of mechanisms which ensure that the management […] runs the firm for the benefit of one or several stakeholders” (Goergen and Renneboog 2006). We use this broad definition of corporate governance, because we believe that the fate of a firm not only depends on the relations between management and shareholders, but also on the relation between management and other stakeholders who provide non-financial resources to the firm (Freeman 1984).

In our literature review, based on 98 studies, we analyze whether corporate governance variables on four different levels (group, individual, firm, and institutional level) are linked with the probability of firms’ financial misconduct. With regard to the group level as the dominant category in our literature review, we separate between (1) board composition, (2) board compensation, (3) audit committees and the internal audit function as monitoring institutions. The individual level of corporate governance refers to specific characteristics of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and/or the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) in view of their major impact on financial reporting quality. The firm level of corporate governance can be divided into ownership structure and monitoring by other stakeholders. Last but not least, our review also includes legal enforcement as part of the institutional level of corporate governance. We exclude the external auditor as a main determinant of the prevention of financial misconduct in view of the massive research activity on this topic and other specific literature reviews on that topic (e.g., Hogan et al. 2008; Trompeter et al. 2014). During the last decade, various studies have been conducted to measure the impact of corporate governance on firms’ financial misconduct, showing heterogeneous results (Habib et al. 2020). Financial restatements can be classified as the most important variable of firms’ financial misconduct in prior research (e.g., Karpoff et al. 2017). This can be easily explained by methodological reasons. Empirical-quantitative research requires an adequate number of observations and comparable proxies. As financial restatements are a common practice in business life and several databases exist (e.g., audit analytics), researchers like to choose financial restatements as a proxy of financial misconduct (Hasnan et al. 2013). The other two categories, enforcement activities and fraud evens, are of lower relevance in empirical-quantitative research yet (e.g., Hasnan et al. 2013). This can be explained by the lower practical relevance of fraud events and enforcement activities and the lower validity of databases which decreases the number of observations for the researchers.

Our goal is to examine the overall relationship between corporate governance and firms’ financial misconduct in prior studies. Thus, to gain an adequate level of comparability within the included studies, we only include archival studies as dominant research method in this research topic. Moreover, as archival research related to our research strength heavily relies on the US-American capital market and is mainly influenced by the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 (DeFond and Zhang 2014), we only include post-SOX-studies (starting with the business year 2006). Corporate governance was massively changed by the SOX as a reaction of the Enron scandal (DeFond and Zhang 2014). The increased regulations on audit committee provisions, internal control audits, inspections of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) and proscription of non audit services have a main impact of corporate governance quality and their impact on financial restatements, enforcement actions and fraud. Thus, research designs pre and post SOX are not comparable. Including both domestic and foreign issuers on the US-American capital market, the before mentioned corporate governance regulations had to be fulfilled for the business year 2006 for the first time. As a consequence, we only include research designs that include at least the business year 2006. After the passing of the SOX) of 2002, several countries implemented similar regulations, so that the SOX is likely to be an international catalyst for a global corporate governance reform initiative during the last two decades.

We stress a growing amount of literature reviews on firms’ financial misconduct in general (e.g., Sievers and Sofilkanitsch 2019a, b) and on related misconduct measures (e.g., Karpoff et al. 2017; Sellers et al. 2020). We identify two meta-analysis on the impact of corporate governance on financial restatements (Habib et al. 2020) and on the link between board independence and corporate misconduct (Neville et al. 2019). We see a major research gap on conducting a literature review on prior corporate governance research in view of the following reasons: First, archival corporate governance research has been increased during the last decade and show heterogeneous results, leading to first meta-analyses (Habib et al. 2020; Neville et al. 2019). Prior meta-analyses have used different methods, variables, and moderators, stressing the need to the structure the main research strengths by a narrative literature review. As meta-analyses and structured literature reviews represent separate research methods with different aims, there is a need for a literature review on the respective topic in line with prior meta-analyses. Second, in line with agency theory, it is questionable whether corporate governance is really linked with reduced firm’s financial misconduct. We thus like to analyze whether corporate governance represents a monitoring tool to decrease information asymmetry between management and shareholders and increase financial reporting quality and which specific variables contribute to this link. In contrast to Habib et al. (2021), we do not only concentrate on financial restatements and we do not include external audit proxies. We also refer to a corporate governance framework with a clear structure of corporate governance levels in contrast to Habib et al. (2021). In contrast to Neville et al. (2019), we are not only interested in the impact of board independence on corporate misconduct. Moreover, as meta-analyses have different goals in comparison to structured literature reviews, focusing on narrative results and tendencies of prior research instead of statistical correlations, we make a main contribution to prior meta-analyses on related topics. Our aim is not to test statistical correlations but to identify major tendencies of prior research, stress the variety of included proxies and deduce fruitful recommendations for future research designs.

Referring to existing literature reviews on our research topic, prior analyses did not restrict their sample on financial misconduct, but also include other measures of financial reporting quality as earnings management (e.g., Ploeckinger et al. 2016) or other determinants of financial misreporting (e.g., Sievers and Sofilkanitsch 2019a, b; Tutino and Merlo 2019a, b). Other researchers restrict their analysis on selective corporate governance variables and restatements (e.g., Street and Hermanson 2019). As we already noted, we like to conduct a different strategy.

As a consequence, we make main contributions to prior literature reviews on that topic. First, we rely on archival research (post-SOX years) on the impact of corporate governance on various proxies of firm’s financial misconduct in view of the massive impact of the SOX on corporate governance and the dominant use of the US-American capital market in our sample. Second, we clearly differentiate between four levels of corporate governance for the first time on the one hand due to a corporate governance framework, and three categories of misconduct (restatements, enforcement activities, and fraud events) on the other hand. With the help of this structure, we list and compare the various corporate governance variables and deduct limitations and recommendations for future research.

Our review of 98 archival studies stresses major gaps in recent corporate governance research and highlights key challenges that researchers face in their research designs. First, our review stresses that financial restatements as misconduct proxy and the group and individual level of corporate governance represent the most important categories in our literature review. Enforcement and fraud events, and the firm and institutional level of corporate governance are of lower relevance yet. Our review also highlights that many studies on corporate governance variables find inconclusive results on firms’ financial misconduct. But there are indications that expertise and especially gender diversity (on the board, on audit committees and female CEOs) decrease firms’ financial misconduct. However, we know very little about the impact of other non-shareholding stakeholders as a monitoring tool on misconduct. Second, in discussing potential future research, we emphasize the need for a more detailed analysis of restatements proxies, recognition of moderator and especially mediator variables, and increased inclusion of interactions between audit committees and external auditors.

Our analysis is structured as follows: First, we present an agency-theoretical foundation and our research framework, stressing our corporate governance framework and related determinants of firms’ financial misconduct and the three main categories of misconduct (Sect. 2). Next, we present the key results of our literature review, whereas we differentiate between several characteristics of internal and external corporate governance (Sect. 3). Our analysis continues with a discussion of our results and research recommendations (Sect. 4). Section 5 provides a conclusion to our analysis.

2 Agency-theoretical framework of included corporate governance and misconduct variables

2.1 Corporate governance measures

The link between corporate governance and firms’ financial misconduct can be motivated by various theories (e.g., stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory, resource-based view; see Habib et al. 2021). As the majority of included studies in this literature review referred to agency theory (Ross 1973; Jensen and Meckling 1976), we also use this theoretical approach. Based on the separation of ownership and control, Jensen and Meckling (1976) characterize the overarching problem of information asymmetries between management and shareholders, resulting in moral hazards and self-serving actions. To decrease those agency conflicts, there is a need to implement strong monitoring mechanisms by the board of directors and its shareholders. Information asymmetries arise in the financial reporting documents, as financial reporting quality may be reduced by errors and fraud, leading to restatements, enforcement activities and fraud events, which may go public. The real economic performance of the firm is not obvious in these situations and impair the information function of the shareholders. Effective corporate governance should put pressure on top managements to prevent or at least reduce firms’ financial misconduct, leading to fewer restatements, enforcement actions or fraud events (Jensen and Meckling 1976). Corporate governance can be classified as a monitoring tool in line with shareholders’ interests of ethical management behaviour. We expect that increased corporate governance quality is linked with better financial reporting quality and thus lower probability of firms’ financial misconduct.

In the following, we present the structure of our corporate governance variables. As there are many different corporate governance frameworks in the literature (e.g., Cohen et al. 2004), we rely on the framework by Jain and Jamali (2016) who differentiate four levels of corporate governance. (1) The group level of corporate governance mainly relates to the board as a mechanism for monitoring managers to avoid agency conflicts (Jain and Jamali 2016). Board structure (e.g., independence), social capital and resource network and demography are main proxies in this context. In our literature review, we distinguish between three main categories of the group level: board composition, board compensation and audit committees and the internal audit function. (2) The individual level of corporate governance addresses demographic or socio-psychological characteristics of specific members of the top management. The CEO and the CFO represent the two most important persons who are included in prior empirical corporate governance research. Thus, we include CEO and/or CFO characteristics, e.g., narcissism, or tenure, in this level. (3) The firm level of corporate governance mainly concentrates on ownership structure (e.g., blockholding, ownership concentration; Jain and Jamali 2016). During the last years, also other stakeholders monitor the board of directors, e.g., financial analysts or rating agencies. Thus, we separate between ownership structure and monitoring by other stakeholders. (4) Last but not least, the institutional level of corporate governance includes formal institutions, e.g., political, legal, and financial systems, as well as information institutions, e.g., socially valued beliefs and norms (Jain and Jamali 2016).

2.2 Group level

The group level of corporate governance is mainly linked to the composition of the board, its committees and the internal audit function. Main board variables include board independence, expertise, gender diversity, networks and social ties and may lead to increased quality of financial reporting. Management should act in line with shareholders’ interests in preventing financial misconduct. The board of directors, at the apex of internal control systems, advise and monitor the management (executive directors) and has to duty to hire, fire, and to compensate the senior management (Gillan and Starks 2000; Shleifer and Visny 1997). Agency theory assumes that proper board composition and compensation leads to increased validity of financial reporting and ethical behaviour (Jensen and Meckling 1976). Based on agency theory, in our literature review, we assume that effective board composition will have a negative impact of the occurrence of firms’ financial misconduct.

Next to board composition, we introduce the audit committee as a central monitoring authority of the management, as well as of the internal and external auditor, and it informally shares information with all three corporate governance bodies (Pomeroy and Thornton 2008). The major role of audit committees is even higher in one-tier-systems in comparison to two-tier-system, as the audit committee represents the only institution in the one-tier-system which monitors the executive directors. Thus, even though the management prepares the financial reports, the audit committee has a significant shared responsibility for the achievement of adequate quality, for instance through the financial audit (Ghafran and O’Sullivan 2013). The audit committee also performs important monitoring activities in relation to external auditor independence which may also be compromised by non-audit services, or by generating adequate internal audit resources (Velte 2017). These activities may result in decreased information asymmetry and conflict of interests between executives and shareholders, leading to better firm reputation and firm valuation. Based on corporate governance regulations after the Enron scandal in the USA, independence from the management and financial expertise are strengthened to ensure appropriate monitoring (Velte and Stiglbauer 2011). But also other kinds of expertise, gender, and network are currently discussed. As a result, audit committee effectiveness should be connected with decreased restatements, enforcement actions and fraud events. In line with the audit committee, the internal audit function also represents a key monitoring institution within the firm. As internal auditors also advise the top management members, independence is a crucial factor (Ege 2015). As internal auditors should closely cooperate with audit committees and the external auditor, we assume that increased internal audit will lead to reduced financial misconduct (Ege 2015).

As a third category of the group level of corporate governance, incentive-based board compensation is a classic tool for overcoming conflicts of interest between management and investors (Lynch and William 2012). While it is recognized that executive compensation should comprise a balanced mix of fixed and performance-related components, long-term incentives have played a key role since the financial crisis in 2008/09. But management compensation arrangements are heterogeneous from an international perspective and no consensus has been found (Campbell et al. 2015). Executive compensation systems should differ from non-executives’ payments in order to decrease conflict of interests between those two parties (Jensen and Murphy 1990). Thus, many firms rely on non-executive compensation packages comprising only fixed components for non-executives, e.g., audit committee members. In line with compensation structure, the amount of board compensation is a major challenge in corporate governance research (Jensen and Murphy 1990). “Excessive” compensation and the non-existence of pay-for-performance-sensitivity of remuneration contracts increase shareholders’ concerns. This can be explained by decreased payouts for shareholders, if management compensation increases while firm performance decreases (Jensen and Meckling 1976). Thus, reliance on short-term financial goals in compensation contracts and excessive payment will lead to increased firms’ financial misconduct. Top managers may hide their unsuccessful strategies by book-related increases in short-term financial performance while the real business transactions are not linked to this increase. Information asymmetries will be higher because financial reporting quality is reduced and shareholders cannot analyze the real economic profit. Thus, we assume that short-term compensation and excessive compensation for executives will be connected with increased firms’ financial misconduct.

2.3 Individual level

The individual level of corporate governance is directly linked with upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason 1984) as the relevance of individual top management characteristics and incentives, especially the chief executive and the chief financial officer (CEO; CFO) can be easily motivated by this theory. Cognitive characteristics and individual values dominate the decision of top management members with a major influence on the second tier managers and other employees. As the measurement of psychological influencing factors is difficult in business practice, Hambrick and Mason (1984) recommended to primarily rely on demographic characteristics, e.g. age, gender. Two key factors have been deducted in several modifications of classical upper echelons: (1) extent of managerial discretion and executive job demands (Hambrick 2007). In this literature review, we assume that upper echelons theory explains the impact of CEO/CFO incentives and characteristics on firms’ financial misconduct. We rely on the assumption that the influence of a CEO/CFO is intensive within a top management team and within the firm in order to influence (un)ethical reporting strategies significantly. In this context, upper echelons theory assumes that not group-related determinants within the board of directors, but the central role of the CEO/CFO itself may be the crucial factor in influencing financial misconduct.

2.4 Firm level

With regard to the residual claim of principals’ stocks and the assumption of homogeneous shareholders’ preferences (Fama and Jensen 1983), dispersed ownership leads to the delegation of the management to executives as agents by investors as principals. Information asymmetry between managers and investors results in moral hazards and self-serving actions because of conflicts of interests between both parties (Harris and Bromiley 2007). To decrease those agency conflicts, investors will implement monitoring mechanisms, e.g., say on pay votings on management compensation. Ownership structure as a key category of firm level of corporate governance can be divided into different characteristics, e.g., institutional ownership, family ownership, state ownership, and foreign ownership, with a dominance of prior research on institutional ownership. In contrast to private investors, institutional investors are companies or organizations that invest money on behalf of other people or organizations. Main examples are mutual funds, pensions, and insurance companies. Institutional investors buy and sell significant amount of stocks, bonds, or other securities. Many institutional investors fulfil an active monitoring function within the corporate governance system due to their main shareholder influence, strategic goals and their increased financial experience and expertise. Thus, institutional ownership should lead to reduced firms’ financial misconduct. Similar associations can be transferred to family, state, and foreign ownership as active monitors.

In line with shareholders, other related stakeholders can fulfil a major monitoring function. Financial analysts are of major relevance of shareholders as they may impose discipline on misbehaving managers and help align the interest of managers with that of the shareholders (Shi et al. 2017). They should improve management incentives to provide credible and transparent financial reporting and a more ethical behavior (Habib et al. 2020). In line with external auditors, financial analysts fulfil a gatekeeper function for the capital market, e.g., by their rating results on firms and investment recommendations (Bradley et al. 2017). Finally, according to classical agency theory, information asymmetries and conflicts of interests are restricted to shareholders as the principals. However, the goals of other stakeholders may be also relevant in corporate governance, leading to sustainable corporate governance (Amis et al. 2020). In view of this theoretical extension, other stakeholder groups, e.g., customers, suppliers, or the whole society may also put pressure on the management to decrease firms’ financial misconduct.

2.5 Institutional level

In our literature review, we mainly rely on legal factors or formal institutions as a key component of the institutional level of corporate governance. As a reaction to financial scandals during the last decades, many regulators implemented enforcement institutions to monitor the reliability of financial accounting in line with external auditors (Gunny and Zhang 2013). Based on our agency theoretical foundation, major information asymmetries and conflicts of interests may even exist after the recognition of audit committees and external auditors. An independent oversight body that controls the audits of public companies may also strengthen top management incentives to create a sound financial reporting in line with the law (Johnson et al. 2018). We already noted that prior archival research on corporate governance mainly focused on the US capital market. As a reaction to the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002, the US government introduced the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). The PCAOB oversees the audits of public companies and other issues in order to protect the interests of shareholders and further the public interest in the preparation of informative, accurate and independent audit reports (Gunny and Zhang 2013). The PCAOB legislations are supervised by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The PCAOB periodically issues inspection reports of registered public accountants. PCAOB inspections should not only incentive audit firms, but also support their related clients (e.g., audit committees) to monitor external audit quality. Thus, we assume that stricter oversight rules will strengthen corporate governance quality, leading to a prevention or reduction of firms’ financial misconduct.

The included corporate governance variables in this literature review are presented in Table 1, illustrating the complexity of research.

2.6 Restatements, enforcement activities and fraud

We already mentioned that we differentiate between three main categories of firms’ financial misconduct: (1) restatements; (2) enforcement activities and (3) fraud events. We also noticed that we exclude earnings management proxies in order to guarantee a greater comparability of the results. Firms’ restatements of financial statements represent the most important measure of firms’ financial misconduct in archival research (Karpoff et al. 2017) due to methodological reasons. Sievers and Sofilkanitsch (2019a, b) define restatements as firms` acknowledgement of former reporting failures and correction of intentional and/or unintentional misreporting. Financial restatements can be a consequence of errors, frauds, or GAAP misapplications. Thus, restatements can be fraud-related or not. However, most restatements (approximately 98%) are linked to unintentional misreporting, e.g., “mistakes” or “clerical errors”, in contrast to “fraud” or “manipulation” cases (Chen et al. 2014). Literature assumes restatements to be the most readily available indicator of low financial reporting and audit quality (Christensen et al. 2019). The majority of studies included in our literature review interpret financial restatements as an inverse measure of financial reporting quality. However, restatements also depend on a successful detection by monitors and announcement of past reporting. Restatements may also indicate strict corporate governance activities in the past (Srinivasan et al. 2015). Executives who are confronted with increased monitoring pressure, e.g., by audit committees, are more likely to agree with correcting prior financial statements (Pyzoha 2015). However, restatements are mainly perceived and applied as a proxy for low corporate governance quality because restatements are often linked with initial undetected misreporting rather than to a subsequent successful detection of misreporting. US-American studies heavily use two major databases for restatement selection: the databases by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and by Audit Analytics (AA) (Karpoff et al. 2017).

In contrast to financial restatements, the presence of fraud charges under regulatory enforcement actions (e.g., Karpoff et al. 2017) is also relevant to measure firms’ financial misconduct. In the USA, since 1982, the SEC has issued Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAER) during or at the conclusion of an investigation against a company, an auditor, or an officer for alleged accounting and/or auditing misconduct. The data is provided by the Center for Financial Reporting and Management (CFRM) at the University of Berkeley (Karpoff et al. 2017). Similar databases including enforcement actions also exist for other regimes, e.g., the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). Finally, there is also a possibility to approximate financial fraud risks by financial statement anomalies that can result from income manipulation or other types of fraudulent activities. Beneish (1999) established an “M-score” and included eight indicators, e.g., sales in receivable index or depreciation index.

Our research framework and the main variables are presented in Fig. 1.

3 Research on the link between corporate governance and firm’s financial misconduct

3.1 Sample selection and content analysis

We stress an increased heterogeneity in empirical research on the link between corporate governance and firms’ financial misconduct due to collected data, study designs, theoretical foundations, and analytical models. We relied on established processes for this structured literature review (Denyer and Tranfiels 2009). Relevant studies were scanned by (inter)national databases (EBSCO Business Source Complete, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and SSRN). We used the terms “restatement”, “fraud”, “manipulation”, “error”, “irregularity”, “revision”, “misconduct”, “misreporting” and “misstatements” and combined these terms with “corporate governance”, “board composition”, “compensation”, “audit committees”, “board network”, “board expertise”, “board experience”, “ownership structure”, “ownership”, “enforcement”, and related terms. We also include relevant keywords for stakeholder groups, e.g., “customers”, “suppliers”, “financial analysts”, “media”. The goal of our literature review is to gain an appropriate level of comparability within the included studies. Thus, only archival research as the most important research method on this topic is included. We did not include analytical, experimental and qualitative papers. As already noted, we did not include studies on the impact of the external auditor (as independent variable) on firms’ financial misconduct. Research on the link between external auditors and firms’ financial misconduct has massively increased during the last years and justifies a separate review. We stress that some researchers already conducted literature reviews on external auditors’ role (e.g., Hogan et al. 2008; Trompeter et al. 2014). This may explain our exclusion strategy. However, we include external auditor factors as possible moderator or mediator variables of corporate governance proxies. We also noted in the introduction that we exclude earnings management as main proxy of financial reporting quality in our literature review in view of the following reasons. First, as we like to increase the comparability of our included studies, we only focus on those studies, which clearly have a link on firms’ financial misconduct as violations of recent accounting standards and related regulations. Second, as prior research also focusses on literature reviews or meta-analyses between corporate governance and earnings management (e.g., Garcia-Meca and Sanchez-Ballesta 2009), we like to contribute to the literature and stressing useful research recommendations for this specific topic. Earnings management includes legal options to influence the financial reporting for specific firm goals, e.g., profit maximization. Possible examples are the voting right according to IAS 16 to conduct a revaluation of property, plant and equipment (fair value accounting) in comparison to historical cost accounting. As investors and other stakeholders will be informed about these accounting practices in the notes, it is easier for them to analyze the real profit situation within the firm. Violations of the accounting standards, e.g., a full fair value accounting of property, plant and equipment according to the German commercial law, cannot be clearly analyzed by the stakeholders, leading to massive information asymmetries. While we stress a dominant research activity on the US capital market, this review does not include a limitation on a special regime. Prior studies also analyze the non-US environment, mainly Asian regimes. After the passing of the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002, several countries implemented similar regulations, so that the SOX is likely to be an international catalyst for a global corporate governance reform initiative during the last two decades. We only include empirical studies whose sample covers the period after the commencement of the SOX 2002, and which use multivariate statistics. Including both domestic and foreign issuers on the US-American capital market, the corporate governance regulations of the SOX had to be fulfilled for the business year 2006 for the first time. As a consequence, we only include research designs that include at least the business year 2006. Apart from the increased complexity of the findings, leading to a temporal limitation of the studies, the increased regulatory density makes a comparison between US-based studies before and after the SOX impossible. Given that research is predominantly focused on the US capital market, the temporal limitation is adequate. A total of 132 studies have been identified. For quality assurance reasons, only the contributions published in international journals with double-blind review have been included. This resulted in a sample reduction by 34 papers to a final sample of 98 studies.

Included studies were coded with regard to the selected auditor-related (sub-)determinants of firms’ financial misconduct, and were matched to our research framework. Significant findings and their indicators were reported as vote-counting technique (Light and Smith 1971).

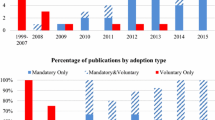

Table 2 provides an overview of the papers per publication year (Panel A), region (Panel B), journal (Panel C), independent variable (Panel D) and dependent variabe (Panel E). Panel A reported a steady increase in studies over the last few years. The years 2018 and 2019 were most important year due to the amount of included studies (16/17 studies). Most of the included studies addressed the US-American setting (59 studies) in comparison to other settings. With one exception, we do not indicate any cross-country settings. Panel C illustrates a great heterogeneity of the journal publications, regarding discipline and quality. Most papers have been published in Accounting and Finance journals (70 studies). The best-known publication outlets are for example, Journal of Business Ethics (11 studies), Contemporary Accounting Research (9 studies), Journal of Accounting and Economics (5 studies), Journal of Business Finance and Accounting (5 studies), and The Accounting Review (5 studies). Panel D stresses a great research focus on the group level (56 studies) and individual level (30) of corporate governance. Panel E indicates that financial restatement studies are most important in our literature review (50), while enforcement actions and fraud events are of lower relevance yet.

3.2 Group level

3.2.1 Board composition

Board independence Prior research results stressed a heterogeneous relationship between board independence and financial misconduct from an international perspective. Some researchers found a negative relationship between board independence and restatements (Baber et al. 2012), enforcement actions (Romano and Guerrini 2012), and fraud (Razali and Arshad 2014; Khoufi and Khoufi 2018). Verriest et al. (2013) stated a positive impact of board independence on restatements, relying on a European setting. However, most included studies in this literature review did not report any significant impact on restatements (Hasnan et al. 2020), enforcement actions (Ghafoor et al. 2019; Hasnan et al. 2013; Inya et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2017) and fraud events (Shan et al. 2013; Tan et al. 2017).

Board expertise Research on board expertise is linked with heterogeneity of included proxies. Managerial ability (Demerjian et al. 2013), executive skills (Rubin and Segal 2019), foreign independent directors (Du et al. 2017), academic experience of executives (Ma et al. 2019) are negatively related to restatements. Ma et al. (2019) also stressed a moderator effect of inefficient external monitoring on that link. Inya et al. (2018) documented a negative influence of independent directors with more experience and longer tenure on enforcement actions. Moreover, based on a Canadian sample, independent directors who reside close to a firm’s headquarter reduce the probability of restatements, but US directors increase it. According to Du et al. (2017), the negative link is only existent in non-state owned firms. Razali and Arshad (2014) documented that international board experience decreases fraud risk. Xiang and Zhou (2020) found that academic independent directors decrease commission of fraud and increase fraud detection, moderated by accounting and legal background of the board members. We also note contrary research results, as board experience and expertise may lead to increased financial misconduct. Background homogeneity of executives (Zhang 2017) and board functioning (Verriest et al. 2013) are linked with increased restatements. Foreign independent directors (Masulis et al. 2012) are connected with higher restatements due to irregularities, but not with other restatements. Moreover, there are indications that founders on the board (Hasnan et al. 2013) and malays director on the board (Nasir et al. 2019) increase enforcement actions. Few studies concentrate on board gender diversity and reported a negative impact on restatements (Wahid 2019), enforcement actions (Ghafoor et al. 2019), and fraud events (Capezio and Mavisakalyan 2016; Cumming et al., 2015; Marzuki et al. 2019). In this context, Wahid (2019) included board connections as a mediator and found significant results.

Board networks In line with board expertise, we note a variety of board network variables in this literature review. Board interlocks to misstating firms (Omer et al. 2020), and political connections to Republican candidates (Notbohm 2019) are related to decreased restatements. According to Kuang and Lee (2017), external social connectedness of independent directors is related to fewer fraud detection given occurrence of fraud, but not to fraud existence. Correia (2014) found a negative impact of political connections of executives through contributions and lobbying on enforcement actions. The author included the following moderator variables and documented a significant effect: recipients as the high-ranking members of the committees with the highest control over the SEC and long-term repeated relationship with the firm, lobbying firms with connections to the SEC or direct lobbying. Kong et al. (2019) also stressed that politically connected independent directors with local, central or both backgrounds are related with fewer enforcement actions. In contrast to these results, board interlocks (Jiang and Zhao 2020) also increase enforcement activities. Moreover, we note some insignificant links between political connections and enforcement actions (Ghafoor et al. 2019; Hasnan et al. 2013), and between multiple directorships and restatements (Hasnan et al. 2020).

Board size Khoufi and Khoufi (2018) represents the only study with a negative impact of board size on fraud events. Other included studies did not find any significant influence of board size on restatements (Hasnan et al. 2020), enforcement activities (Romano and Guerrini 2012), and fraud (Razali and Arshad 2014; Salleh and Othman 2016; Shan et al. 2013; Tan et al. 2017). This is in line with prior research on board size on other dependent variables, e.g., firm performance, stressing the heterogeneous character of this corporate governance proxy.

Board meeting frequency We note just two studies on the link between board meeting frequency and financial misconduct. While Salleh and Othman (2016) stressed a decreased amount of fraud events, Shan et al. (2013) reported an opposite link.

Board age Xu et al. (2018) concentrated on board age and found a negative impact on enforcement actions in China. This link was weakened by CEO-board directional age difference as moderating variable.

3.2.2 Audit committees

Audit committee independence Few studies have included independence of audit committee members in their research design. Two papers indicated a negative impact of independent members on restatements (Lary and Taylor 2012), and enforcement activities (Romano and Guerrini 2012). Another two studies could not find any significant impact on fraud (Khoufi and Khoufi 2018; Marzuki et al. 2019). Tan and Young (2015) compared “little r” restatements and big ones and found that board independence leads to more little financial restatements.

Audit committee expertise Most included studies on audit committees rely on the expertise of its members, especially on accounting or financial expertise. Das et al. (2020) found a negative link between accounting expertise on the audit committee and restatements. Cohen et al. (2014) documented that the combination of accounting and industry expertise leads to lower restatements in comparison to single accounting expertise on the audit committee. Lary and Taylor (2012) also found a negative impact of combined financial and industry expertise on restatements. Financial expertise (Khoufi and Khoufi 2018) and audit committee effectiveness (Razali and Arshad 2014) are also related to fewer fraud events. In contrast to this, Albrecht et al. (2018) stressed an increased influence of accounting expertise on restatements, moderated by excess compensation and earnings management. According to Lisic et al. (2019), the positive link between accounting expertise and restatements is moderated by adverse internal control audit opinions. Verriest et al. (2013) documented a positive impact of audit committee effectiveness on restatements. However, prior studies also stressed insignificant relationships between financial expertise and restatements (Hasnan et al. 2020), financial expertise and fraud (Marzuki et al. 2019), independent financial experts and enforcement actions (Inya et al. 2018), and supervisory expertise and restatements (Cohen et al. 2014). In contrast to the aforementioned studies, Ashraf et al. (2020), in a recent study, analyzed the impact of digital expertise on the audit committee on material restatements and found a negative relationship. In view of the great challenges of digital transformation and their huge impact on accounting practice, this kind of expertise will be mainly relevant in the future. With regard to gender diversity, Oradi and Izadi (2020) documented a negative impact on restatements, moderated by independent female financial experts on the audit committee. Analyzing audit committee cultural diversity, Felix et al. (2021) found a negative impact on restatements. This link was more pronounced by firms operating in complex environments and CEO power. Pathak et al. (2021) separated between relations- and task-oriented on the one hand and between fraud-related and error-related restatements on the other hand. Relations-oriented diversity leads to lower fraud-related restatements while task-oriented diversity and error-related restatements are negatively related.

Audit committee networks In line with included studies on the board network, we identify some researchers who concentrated on audit committee networks. Audit committee members who are connected with firms that disclosed a restatement within the prior three years or with material internal control weaknesses cause lower restatements (Cheng et al. 2019). Similar links can be stated for audit committee connectedness through director networks (Omer et al. 2020). In contrast to this, co-opted audit committees (Cassell et al. 2018) and independent audit committee multiple-directorships (Sharma and Iselin 2012, based on post SOX-periods) are connected with increased restatements.

Audit committee size, tenure and meeting frequency Gao and Huang (2018) analyzed audit committees with an odd number of directors and found that the negative effect on restatements was moderated by audit committee members with heterogeneous options, less equity ownership, smaller size, and entrenched management. With regard to tenure-diverse audit committees, Li and Wahid (2018) also documented a negative impact on restatements. However, audit committee diligence (Lary and Taylor 2012) and meeting frequency (Marzuki et al. 2019) were not related to restatements and fraud. Jia et al. (2009) analyzed the Chinese two-tier system and found a positive impact of supervisory board size and meetings on enforcement actions.

Audit committee presence Audit committee presence (Yang et al. 2017; Romano and Guerrini 2012) did not influence enforcement actions.

3.2.3 Internal audit function

In line with the audit committee, the internal audit function represents a key monitoring institution within the firm in order to prevent firms’ financial misconduct. Ege (2015) found that the quality of the internal audit function decreases fraud or other intentional misconduct actions. Moreover, Zeng et al. (2021) documented that internal audit executive’s supervisory ability leads to lower fraud.

3.2.4 Board compensation

Two studies reported a negative link between executive compensation (Hasnan and Hussain 2020), pay disparities (Zhang et al. 2018), and restatements. Zhang et al. (2018) also stressed a moderator effect of state ownership, CEO turnover, and internal incoming CEOs. Armstrong et al. (2013) reported that ‘vega’ is positively related to both restatements and enforcement actions. According to Hass et al. (2016), managers’ pay to performance sensitivity from stockholdings increase enforcement actions. However, some researchers indicated an insignificant impact of board compensation on financial misconduct, based on managerial ownership (Tan et al. 2017), and stock ownership by supervisory boards (Yang et al. 2017). Few studies also included clawback provisions as recent opportunity of incentive-based management compensation systems. Firm-initiated clawback provisions (Chan et al. 2012; Fung et al. 2015), and clawback provision strength (Erkens et al. 2018) reduce restatements and fraud events. Fung et al. (2015) also reported that the negative link was weakened by insider sales.

3.3 Individual level

3.3.1 CEO/CFO expertise

In line with board (audit committee) composition and board compensation, an increased number of studies included individual characteristics of top management team members with a clear focus on the CEO. CEO expertise represents one of the most important corporate governance variables in this context with various individual proxies. CEOs as ex-military members lead to lower enforcement actions, moderated by CEO non-duality model and board independence (Koch-Bayram and Wernicke 2018). Huang et al. (2012) also found that CEO age reduces enforcement actions. In contrast to this, some researchers stressed a positive impact of executive expertise on firm’s financial misconduct. CEO tenure increases misconduct, weakened by large and independent boards (Altunbas et al. 2018). CEO and CFO outside directorships and network ties to auditors lead to higher restatements, moderated by network on the local level (Yu et al. 2020). Two studies also found a negative impact of CFO gender on fraud events in China (Liao et al. 2019; Luo et al. 2020). In more detail, Liao et al. (2019) stated that this link is moderated by gender mixed boards and less powerful CEO and CFO directorships. According to Luo et al. (2020), the link was moderated by the level of education and external job opportunities.

3.3.2 CEO/CFO networks

Wu et al. (2016) reported that CEO and/or chairman political connections are linked with lower restatements. This connection was more pronounced in non-state owned firms and weak legal enforcement environment. Moreover, CEO employment, education, and other social network connections also reduce restatements (Bhandari et al. 2018). Bedard et al. (2014) stressed a negative impact of CFO inside directorship on restatements. In contrast to this, according to Khanna et al. (2015), CEO connections with top four non-CEO executives and directors through their appointment decisions are linked with increased restatements.

3.3.3 CEO power and duality

Two studies documented a positive influence of CEO power indices on restatements (Lisic et al. 2016). Lisic et al. (2016) also stated that this relationship is moderated by internal control weaknesses. CEO duality represents one of the most important proxies of CEO power. Some researchers stressed a positive influence on fraud (Khoufi and Khoufi 2018) and enforcement actions (Yang et al. 2017). Other researchers reported an insignificant impact on enforcement actions (Inya et al. 2018; Romano and Guerrini 2012) and fraud events (Salleh and Othman 2016; Shan et al. 2013; Tan et al. 2017).

3.3.4 CEO/CFO compensation

Some studies stressed a negative relationship between CEO compensation and firms’ misconduct. Conyon and He (2016) reported a negative influence of CEO equity-based compensation on fraud. CEO in-the-money-value also reduces restatements, moderated by clawback provisions (Natarajan and Zheng 2019). He (2015) found that CEO inside debt holdings cause decreased restatements. Zhou et al. (2018) stressed that CEO and CFO (equity) compensation reduces enforcement actions, while this link is weakened by delisting pressure of the firm. In contrast to these studies, according to Bao et al. (2021), CEO pay ratio and restatements are positively linked, while CEO power strengthens and CEO ability weakens this relationship. Hogan and Jonas (2016) found that CEO and CFO equity proportion increases and difference in CEO and CFO pay structure decreases restatements. However, Ghafoor et al. (2019) reported an insignificant relationship between CEO equity compensation and enforcement activities.

3.3.5 CEO/CFO hubris, overconfidence and narcissism

MacManus (2018) included CEO hubris variables and stressed that self-importance and accomplishment increase restatements. There are also indications that both CEO narcissism (Rijsenbild and Commandeur 2013) and CFO narcissism (Ham et al. 2017) imply more misconducts. Moreover, CEO overconfidence increase restatements (Presley and Abbott 2013). According to Hobson et al. (2012), vocal markers of cognitive dissonance of CEOs during earnings conference calls lead to more restatements.

3.4 Firm level

3.4.1 Ownership structure

Institutional ownership and blockholdings With regard to blockholders, prior research did not find any impact on restatements (Baber et al., 2015) and fraud (Tan et al. 2017). Ownership concentration both increases (Yang et al. 2017) or decreases (Inya et al. 2018) enforcement actions. Dou et al. (2016) analyzed the nature of blockholders and stated that hedge funds and venture capitalists reduce restatements. While Inya et al. (2018) documented a negative link between institutional ownership and enforcement activities, Baber et al. (2015) found insignificant results. Relying on the nature of institutional investors, dedicated institutional ownership increases (Shi et al. 2017) or decreases (Ghafoor et al. 2019) enforcement actions. In contrast to most studies on that research topic, Hedge and Zhou (2019) assumed a non-linear relationship in their study on investor optimism regarding firm-specific attributes. When firm-level optimism is moderate, restatements increase, but it decreases by high optimism.

Foreign ownership Few researchers on Asian regimes included foreign ownership as an external corporate governance variable. Shan et al. (2013 found a negative impact on fraud events. However, also insignificant effects on enforcement actions do exist (Hasnan et al. 2013; Inya et al. 2018).

Family ownership Asian studies also relied on family ownership. Hasnan et al. (2013) stated that family ownership leads to fewer enforcement actions, while other studies reported insignificant impact on restatements (Sue et al. 2013) and enforcement activities (Ghafoor et al. 2019).

State ownership In line with foreign and family ownership, the integration of state ownership is only relevant in Asian studies. There are indications that state ownership reduce fraud events (Shan et al. 2013; Shi et al. 2020). Shi et al. (2020) also found that CEO political background moderates this relationship.

3.4.2 Monitoring by other stakeholders

Few studies addressed financial analysts and their impact on firms’ financial misconduct. Bradley et al. (2017) found that industry expertise and monitoring effectiveness of financial analyst coverage reduce restatements. In contrast to this, according to Shi et al. (2017), analyst recommendations and enforcement actions are positively linked. If a forecast signal indicates a greater difference between analysts’ and auditors’ earnings expectations, restatements increase (Newton 2019). Same directions can be found if an analyst forecast signal indicates a greater likelihood of income increasing earnings management.

With regard to other stakeholder groups, labor union strength reduces restatements (Bryan 2017). According to Hopkins (2018), US circuit court ruling that made it easier for public corporations to defend against security class actions lead to increased restatements. This link was moderated by low stock return, ex ante risk of meritorious litigation and transient institutional ownership. While Yang et al. (2017) stated a positive link between regulatory pressure and enforcement actions, Zhang (2018) found a negative impact of public governance and enforcement actions. This relationship was strengthened by non-state ownership, weak legal environment, and poor local economies, and weakened by CEO age.

3.5 Institutional level

Our literature review only identifies legal enforcement as part of the institutional level of corporate governance. Most studies on characteristics of enforcement institutions relied on the US capital market and addressed the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) as auditor oversight body. PCAOB Part II reports of annually inspected firms (Johnson et al. 2018), initial PCAOB inspections (Khurana et al. 2020), and clients of annually PCAOB inspected firms relative to clients of triennially inspected firms (Tanyi and Litt 2017) lead to reduced restatements. Khurana et al. (2020) also reported that this relationship is less for Big four audits and more effected for triennially inspected non-big four audit firms. In contrast to these studies, PCAOB inspection reports for triennially inspected auditors and restatements are positively related, when inspection reports are seriously deficient (Gunny and Zhang 2013). Two studies also concentrated on taxation (Lennox 2016; Li and Ma 2019). Li and Ma (2019) stated that tax enforcement efforts reduce general and tax-related restatements. Lennox (2016) did not find any impact of PCAOB’s restrictions on auditors’ tax services on restatements.

3.6 Main results

Our literature review indicates that most research on corporate governance and firms’ misconduct addressed the group and individual level of corporate governance. The firm and institutional level of corporate governance were of lower attraction yet and they mainly relied on ownership structure end legal enforcement. We also stress that moderator analyses and especially mediator analyses were rarely included yet. Most empirical research also neglect non-linear relationships between corporate governance, restatements and other misconduct variables. There are clear indications that expertise on the board, on audit committees and of the CEO/CFO increase financial reporting quality. Interestingly, all included studies on gender diversity on the board, audit committees and on female CFOs lead to reduced restatements, enforcement actions and fraud. While the amount of studies on individual psychological characteristics of the CEO and CFO is rather low, there are indications that CEO hubris, overconfidence and narcissism increase misconduct. However, most included research strengths show rather heterogeneous results and raise future questions about the real impact of corporate governance on firm’s financial misconduct. We identify major research gaps and limitations of prior studies which we will focus in the next section.

4 Discussion and future research recommendations

As the majority of our studies included in this literature review have addressed financial restatements and the group level of corporate governance, there is much room for recommendations for future research. First, we know relatively little about the influence of corporate governance on different kinds of restatements and other kinds of misconduct. We refer to Sievers and Sofilkanitsch (2019a, b), who recommend to differentiate between severe (intentional) and less severe (unintentional) restatements. Few researchers explicitly differentiate between the nature of restatements, e.g., IT-related (Ashraf et al. 2020) or tax-related restatements (Lennox 2016; Li and Ma, 2019). However, the recognition of multiple misconduct variables in prior research models is very rare (e.g., Armstrong et al. 2013). In view of the heterogeneous results of prior research, validity of included misconduct proxies should be increased. An interesting question relates to the development of fraud probability scores before and after financial restatements. The relationship between earnings quality and restatements before and after the restatement events should be further analyzed. Changes in the F-score (Dechow et al. 2011) and the M-score (Beneish 1999) should be included as moderator or mediator variables in future archival research. Restatements can be used as a proxy for both disclosures of prior reporting failure (restatement announcement) and misreporting (restated periods). Restatement type is also differently used in prior archival research (e.g., annual vs. quarterly, severe vs. less severe). We also note that other firm’s financial misconduct proxies are rarely used. We know relatively little about the relationship between corporate governance and fraud events in archival research. As fraud events are mainly lower in comparison to restatement cases, researchers focused on restatements and related databases (Karpoff et al. 2017).

Our methodological recommendations also relate to corporate governance-related determinants. While there is an increased amount of studies which analyze the impact of the board of directors on firms’ financial misconduct, we know very little about non-shareholding stakeholder pressure on firm’s financial misconduct. In comparison to ownership structure, prior archival research on the firm and institutional level just rely on financial analysts and enforcement institutions. However, other stakeholder groups also punish illegal financial reporting behavior of firms (e.g., media pressure). Customers may call for a boycott for unethical products and services, suppliers and business partner may change to other firms, and employees may leave the fraud firms. Thus, we like to encourage future researchers to include new innovative proxies, also related to hand-collected data selection, in order to complement our picture of external (sustainable) corporate governance as a powerful monitoring mechanism.

While prior research has also included external auditor variables as main determinants of firms’ financial misconduct, especially based on financial restatements (Hogan et al. 2008; Trompeter et al. 2014), we know very little about the interaction between external auditors and corporate governance mechanisms. External auditors mainly support the audit committee, leading to a strong cooperation between both parties. We thus recommend to connect board composition variables, e.g., independence and expertise of audit committee members, and measures of audit quality, e.g., industry expertise, audit firm size, and auditor independence proxies, and their contribution to firm’s financial misconduct. It can be assumed that audit committee effectiveness and external audit quality may be classified as complementary mechanisms to reduce financial restatements and other kinds of misreporting. In line with board composition, we know very little about the interdependencies between auditors and ownership structure on this research topic. Ownership structure, e.g., institutional ownership, may have a strong impact on both auditor characteristics and managers’ incentives to financial misconduct. Our recommendations are not only restricted on corporate governance, but are also related to country-related governance. We encourage future researchers to conduct cross-country studies and include country effects, e.g., strength of shareholder rights, enforcement strength or cultural aspects. Culture has a main impact of managers’ motivations to conduct fraud and related negative events.

5 Conclusion

This study addresses a systematic review of archival research on the impact of corporate governance on firms’ financial misconduct. Our research is based on the famous fraud triangle by Cressey (1953) and an agency-theoretical framework. Agency theory assumes that corporate governance as major monitoring tools will detect and prevent firms’ financial misconduct as corporate governance will decrease information asymmetries. During the last decades, several serious cases of top management fraud have reduced stakeholder trust in financial reporting. The Enron scandal on the US-American capital market or the insolvency of the former Wirecard group company in Germany in 2020 should be stressed in this context. Recently, (inter)national standard setters discuss potential corporate governance regulations in order to decrease the probability of firms’ financial misconduct (Habib et al. 2020), e.g., based on compliance management and whistleblowing systems. Various corporate governance items, e.g., executive and non-executive directors within the board, external auditors, shareholders, enforcement institutions, are included in this discussion.

In line with prior literature, we clearly separate between four levels of corporate governance (group, individual, firm, and institutional level) and analyze their contribution to firms’ financial misconduct in prior archival settings. In more detail, we differentiate between board composition, compensation, audit committees and internal audit function as group level of corporate governance. CEO and/or CFO characteristics represent the individual level of corporate governance. We include ownership structure and monitoring by other stakeholders as firm level of corporate governance. Legal enforcement represents the key proxy of institutional level of corporate governance. We only include post-SOX studies in view of the massive impact of the corporate governance regulations in the US-American setting as dominant regime in our literature review. The external auditor was excluded in this literature review in view of the massive research activity on this topic and prior specific literature reviews (e.g., Hogan et al. 2008; Trompeter et al. 2014). We assume that corporate governance as monitoring mechanisms will lead to lower firms’ financial misconduct in line with agency theory as a proper corporate governance will lower information asymmetries between management and shareholders and support financial reporting quality. Most of our studies included in this literature review use financial restatements as dependent variable due to methodological reasons. While we also include enforcement actions and fraud events as misconduct proxies, we exclude earnings management. We follow the assumption that earnings management is in line with respective accounting regulations and standards while firms’ financial misconduct is connected with violations of the law.

Our review of 98 archival studies indicates that many studies on corporate governance variables find inconclusive results on firms’ financial misconduct. But there are indications that gender diversity on the board, on audit committees, and female CEOs decreases firms’ financial misconduct. However, we know very little about the impact of non-shareholding stakeholders on misconduct. We also give useful recommendations for future archival research on the link between corporate governance and firms’ financial misconduct. More specifically, we encourage future researchers to increase the validity of research designs. Restatement events should be better analyzed with regard to their nature. Future studies should include a mixture of different misconduct proxies and evaluate, whether other factors moderate or mediate the link between corporate governance and restatements. Methodological concerns arise in the low attraction in moderator and especially mediator analysis. In more detail, board composition, e.g., audit committees, and ownership structure have major interdependencies with external audit quality to detect and prevent financial misconduct of the firm.

This study has main implications for regulatory bodies and business practice. Regulators should be aware of the possibilities and limitations of corporate governance variables on firms’ misconduct, especially on fraud events. Recent discussions must consider, whether monitoring or incentive-based elements are crucial to increase ethical management behavior of listed corporations. Non-executives should implement adequate management compensation systems to strengthen financial reporting quality and decrease intentional misreporting. Stricter legal rules cannot prevent firms’ financial scandals if “tone at the top” is unethical and leadership style of executive directors is questionable. Firms’ financial misconduct should be more linked to corporate social responsibility (CSR) and compliance management systems in the future.

Availability of data and material

Yes.

Notes

In our literature review, we exclude studies with a focus on earnings management as major proxy of financial reporting quality. Earnings management includes legal options to influence the financial statement and other financial reporting information from a quantitative and/or qualitative way. In contrast to this, our interpretation of firms’ financial misconduct solely deals with violations of recent (inter)national accounting standards and related regulations.

References

Albrecht A, Mauldin EG, Newton NJ (2018) Do auditors recognize the potential dark side of executives’ accounting competence? Account Rev 93:1–28

Altunbasü Y, Thornton J, Uymaz Y (2018) CEO tenure and corporate misconduct: evidence from US banks. Financ Res Lett 26:1–8

Amiram D, Bozanic Z, Cox JD, Dupont Q, Karpoff JM, Sloan R (2018) Financial reporting fraud and other forms of misconduct: a multidisciplinary review of the literature. Rev Acount Stud 23:732–783

Amis J, Barney J, Mahoney JT, Wang H (2020) From the Editor. Why we need a theory of stakeholder governance. And why this is a hard problem. Acad Manag Rev 45:499–503

Armstrong CS, Larcker DF, Ormazabal G, Taylor DJ (2013) The relation between equity incentives and misreporting: the role of risk-taking incentives. J Financ Econ 109:327–350

Ashraf M, Michas PN, Russomanno D (2020) The impact of audit committee information technology expertise on the reliability and timeliness of financial reporting. Account Rev 95:23–56

Baber WR, Lihong L, Zinan Z (2012) Associations between internal and external corporate governance characteristics: implications for investigating financial accounting restatements. Account Horiz 26:219–237

Baber WR, Kang S-H, Liang L, Zhu Z (2015) External corporate governance and misreporting. Contemp Account Res 32:1413–1442

Bao MX, Cheng X, Smith D, Tanyi P (2021) CEO pay ratios and financial reporting quality. Glob Finance J 47:100506

Bedard JC, Hoitash R, Hoitash U (2014) Chief financial officers as inside directors. Contemp Account Res 31:787–817

Beneish MD (1999) The detection of earnings manipulation. Financ Anal J, September/October, 24–36.

Bhandari A, Mammadov B, Shelton A, Thevenot M (2018) It is not only what you know, it is also who you know: CEO network connections and financial reporting quality. Audit J Pract Theory 37:27–50

Bradley D, Gokkaya S, Liu X, Xie F (2017) Are all analysts created equal? Industry expertise and monitoring effectiveness of financial analysts. J Account Econ 63:179–206

Brody RG, Melendy SR, Perri FS (2012) Commentary from the American Accounting Association’s 2011 annual meeting panel on emerging issues in fraud research. Account Horiz 26:513–531

Bryan DB (2017) Organized labor, audit quality, and internal control. Adv Account 36:11–26

Campbell JL, Hansen J, Simon CA, Smith JL (2015) Audit committee stock options and financial reporting quality after the sarbanes-oxley act of 2002. Auditing 34:91–120

Capezio A, Mavisakalyan A (2016) Women in the boardroom and fraud: evidence from Australia. Aust J Manag 41:719–734

Cassell CA, Myers LA, Schmardebeck R, Zhou J (2018) The monitoring effectiveness of co-opted audit committees. Contemp Account Res 35:1732–1765

Chan LH, Chen KCW, Chen T-Y, Yu Y (2012) The effects of firm-initiated clawback provisions on earnings quality and auditor behavior. J Account Econ 54:180–196

Chen J-F, Chou Y-Y, Duh R-R, Lin Y-C (2014) Audit committee director-auditor interlocking and perceptions of earnings quality. Auditing 33:41–70

Cheng S, Felix R, Indjejikian R (2019) Spillover effects of internal control weakness disclosures: the role of audit committees and board connections. Contemp Account Res 36:934–957

Christensen BE, Neuman SS, Rice SC (2019) The loss of information associated with binary audit reports: evidence from auditors’ internal control and going concern opinions. Contemp Account Res 36:1461–1500

Cohen JR, Krishnamoorthy G, Wright A (2004) The corporate governance mosaic and financial reporting quality. J Account Lit 23:87–152

Cohen JR, Hoitash U, Krishnamoorthy G, Wright AM (2014) The effect of audit committee industry expertise on monitoring the financial reporting process. Account Rev 89:243–273

Conyon MJ, He L (2016) Executive compensation and corporate fraud in China. J Bus Ethics 134:669–691

Correia MM (2014) Political connections and SEC enforcement. J Account Econ 57:241–262

Cressey DR (1953) Other people’s money. A study of the social psychology of embezzlement. Free Press, New York

Cumming D, Leung TY, Rui O (2015) Gender diversity and securities fraud. Acad Manag J 58:1572–1593

Das S, Gong JJ, Li S (2020) The effects of accounting expertise of board committees on the short- and long-term consequences of financial restatements. J Account Audit Finance (online first)

Dechow PM, Ge W, Larson CR, Sloan RG (2011) Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemp Account Res 28:17–82

DeFond M, Zhang J (2014) A review of archival auditing research. J Account Econ 58:275–326

Demerjian PR, Lev B, Lewis MF, McVay SE (2013) Managerial ability and earnings quality. Account Rev 88:463–498

Denyer D, Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review. In: Buchanan D, Bryman A (eds) The Sage handbook of organizational research methods Sage. Sage, London, pp 671–689

Dou Y, Hope OK, Thomas WB, Zou Y (2016) Individual large shareholders, earnings management, and capital-market consequences. J Bus Financ Acc 43:872–902

Du X, Jian W, Lai S (2017) Do foreign directors mitigate earnings management? Evidence from China. Int J Account 52:142–177

Ege MS (2015) Does internal audit function quality deter management misconduct? Account Rev 90:495–527

Erkens MHR, Gan Y, Yurtoglu BB (2018) Not all clawbacks are the same: consequences of strong versus weak clawback provisions. J Account Econ 66:291–317

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Econ 26:301–325

Felix R, Pevzner M, Zhao M (2021) Cultural diversity of audit committees and firms’ financial reporting quality. Account Horiz 35:143–159

Firoozi M, Magnan M, Fortin S (2019) Does proximity to corporate headquarters enhance directors’ monitoring effectiveness? A look at financial reporting quality. Corp Govern Int Rev 27:98–119

Freeman RE (1984) Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press, New York

Fung SYK, Raman KK, Sun L, Xu L (2015) Insider sales and the effectiveness of clawback adoptions in mitigating fraud risk. J Account Public Policy 34:417–436

Gao H, Huang J (2018) The even–odd nature of audit committees and corporate earnings quality. J Acc Audit Financ 33:98–122

Garcia-Meca E, Sanchez-Ballesta JP (2009) Corporate governance and earnings management: a meta-analysis. Corp Gov 17:594–610

Ghafoor A, Zainudin R, Mahdzan NS (2019) Factors eliciting corporate fraud in emerging markets: case of firms subject to enforcement actions in Malaysia. J Bus Ethics 160:587–608

Ghafran C, O’Sullivan N (2013) The governance role of audit committees. Reviewing a decade of evidence. Int J Manag Rev 15:381–407

Gillan SL, Starks LT (2000) Corporate governance proposals and shareholder activism. J Financ Econ 57:275–305

Goergen M, Renneboog L (2006) Corporate governance and shareholder value. In: Lowe D, Leiringer R (eds) Commerical management of projects: defining the discipline. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp 100–131

Gunny KA, Zhang TC (2013) PCAOB inspection reports and audit quality. J Account Public Policy 32:136–160

Habib A, Bhuiyan MBU, Wu J (2021) Corporate governance determinants of financial restatements: a meta-analysis. Int J Account 56:2150002

Habib A, Bhuiyan MBU, Wu J (2020) Corporate governance determinants of financial restatements: a meta-analysis. Int J Account (Forthcoming)

Ham C, Lang M, Seybert N, Wang S (2017) CFO narcissism and financial reporting quality. J Account Res 55:1089–1135

Hambrick DC (2007) Upper echelons theory. Acad Manag Rev 32:334–343

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons. Acad Manag Rev 9:193–206

Hammersley JS (2011) A review of model of auditor judgments in fraud-related planning tasks. Audit J Pract Theory 30:101–128

Harris J, Bromiley P (2007) Incentives to cheat. Organ Sci 18:350–367

Hasnan S, Rahman RA, Mahenthiran S (2013) Management motive, weak governance, earnings management, and fraudulent financial reporting: Malaysian evidence. J Int Account Res 12:1–27

Hasnan S, Mohd Razali MH, Mohamed Hussain AR (2020) The effect of corporate governance and firm-specific characteristics on the incidence of financial restatement. J Financ Crime (online first)