Abstract

Despite the presence of the term ‘entrepreneurial role model’ (ERM) in the discourse on entrepreneurship, existing empirical evidence on the effects of role models is rather limited. By investigating 86 published journal articles, we provide a structured overview of the academic research on role models’ effects on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. We reveal that prior research focuses particularly on different types of role models (by whom), at which stage of life (when) and in which context the exposure to role models occurs. We use these research areas to structure our review. By expanding the understanding of the current state of ERM research, we reveal research gaps and provide future research recommendations. Our work could help policy makers and educators consider the different types of role models, the sociocultural context and the life cycle stage of the participants in structuring their entrepreneurship education programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is an extensive discussion among researchers and practitioners about why some individuals start their own business while others do not (e.g., Zapkau et al. 2017; Baron 2004; Shane and Venkataraman 2000). However, to date, no clear answer to this question exists. When asked why they started their own business, entrepreneurs often answer that ‘others’ significantly influenced their decision. These ‘others’ are usually entrepreneurs of different types and with different characteristics, such as renowned individuals, previous colleagues, or relatives. Such people can be understood as role models (Bosma et al. 2012). There is a consensus among researchers that observing role models empowers individuals to discover and learn specific skills and gain the knowledge required to be an entrepreneur (Scherer et al. 1989b; Scott and Twomey 1988; Scherer et al. 1989a; Lent et al. 1994; Bosma et al. 2012). However, although prior studies acknowledge the significance of role models for potential entrepreneurs, there is no common understanding of the effect of role models on entrepreneurship, and research in this area is rather fragmented (Bosma et al. 2012; Van Auken et al. 2006). The purpose of our literature review is to provide a structured overview of previous research on role models in the entrepreneurship context. In particular, we focus on the research areas investigating different types of role models, in which context and at which stage of an individual’s life are entrepreneurial intentions and behavior most affected. Our aim is to investigate these research areas by providing a systematic review of the literature. Thus, we took into account the fragmented characteristic of this field of investigation, which is based on various types of role models, outcome variables, methodologies and contexts.

Our study contributes to the role model and entrepreneurship literature in different ways and provides implications for policy makers and educators. First, our study contributes to the ERM literature by providing a structured overview of prior findings on ERMs (e.g., Scherer et al. 1989a; Van Auken et al. 2006; BarNir et al. 2011; Mungai and Velamuri 2011), identifying gaps and proposing future research directions. Second, we contribute to the entrepreneurship literature (e.g., Bosma et al. 2012; Carr and Sequeira 2007; Lindquist et al. 2015) by demonstrating that entrepreneurial intentions and behavior are affected by exposure to role models and that this effect depends on by whom, when and in which context this exposure occurs. Lastly, we contribute to the entrepreneurial education literature (e.g., Du Toit and Muofhe 2011; Walter and Block 2016; Souitaris et al. 2007; Nowiński and Haddoud 2019) by highlighting that the integration of role models in entrepreneurial education programs could foster entrepreneurial intentions and behavior (Block et al. 2013). Policy makers and educators can benefit from this structured knowledge of ERMs to effectively integrate role models in entrepreneurial education programs.

The present research systemically reviews 86 journal articles published from the topic’s first emergence in 1988 to the end of March 2019. In the following section, we highlight the methods used to identify the studies included in our review. In Sect. 3, we present our categorization scheme and provide an overview of the ERM research area and the main effects of role models on entrepreneurship. These findings are summarized in Sect. 4, and future research areas are identified. Section 5 summarizes our study.

2 Methodology

Studies on role models’ effects on entrepreneurship have noticeably increased over the past few years. However, research contexts and findings on ERMs are not homogenous, and the literature is fragmented. To analyze the literature on ERMs and to appropriately explore and structure our findings, we used a structured approach (Webster and Watson 2002). Based on recommendations by Fisch and Block (2018) and in line with best practices (Short 2009), we used Web of Science, Google Scholar, and related databases to identify studies on role model influences on entrepreneurship. First, we searched for the relevant publications by using the keywords ‘entrepreneurial role model’ and matching words such as ‘parents’, ‘peers’, ‘family’, ‘positive’, ‘gender’, ‘negative’, ‘successful’, ‘unsuccessful’, ‘entrepreneurial examples’, ‘nonfamily’, ‘mentors’, ‘teachers’, ‘educators’, ‘similar’ ‘intentions’, ‘behavior’ and ‘social learning’ in their titles, keywords or abstracts. In a second step, we used backward and forward searches based on the articles’ citations and reviewed these findings (Levy and Ellis 2006).

Overall, the search yielded 563 papers.Footnote 1 We decided to include only peer reviewed journal articles, as they are considered validated knowledge (Podsakoff et al. 2005). We did not specify or narrow down our research to higher-impact journals and included articles from all journals that met the selection criteria. However, we excluded books, book chapters, reports and conference papers due to missing or inconsistent peer review processes (Jones et al. 2011). We further limited our review to English-language journals, as they have an extensively higher impact factor than non-English journals (Mueller et al. 2006). After following these steps, 189 articles remained in our sample. We read the abstracts of all 189 papers to ensure that the articles deal with the influence of role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior and their antecedents such as entrepreneurial attitudes (Robinson et al. 1991; Kolvereid 1996) and related constructs such as entrepreneurial interest (McClelland 1965; Schmitt-Rodermund 2004), entrepreneurial motivation (Segal et al. 2005; Shane et al. 2003) and entrepreneurial career preference (Scherer et al. 1989a). When in doubt about the exact contribution of a paper to our research question, we reviewed the entire paper. We identified several papers focusing on the effects of role models on entrepreneurial aspirations (Capelleras et al. 2019), entrepreneurial potential (e.g., Galloway and Kelly 2009; Krueger and Brazeal 1994), entrepreneurial fear of failure (Wyrwich et al. 2016, 2018), entrepreneurial awareness and mindset (Robinson et al. 2016), and on self-efficacy (e.g., Dempsey and Jennings 2014). However, we decided to exclude these papers from our review, as the focus of our research is on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. We also eliminated papers in which role models were not the main focus or the type of role model was undefined. During this process, an additional 103 papers were excluded.

In total, 86 published journal articles remained for inclusion in our review, of which 76 are quantitative, 8 are qualitative, and 2 are conceptual in nature. The studies are from a variety of disciplines, including business and economics (e.g., Dohse and Walter 2012; Minniti 2005), psychology (e.g., BarNir et al. 2011; Obschonka et al. 2011), sociology (e.g., Sørensen 2007), and education research (e.g., Rosique-Blasco et al. 2016; Schwarz et al. 2009; Fellnhofer 2018).

3 Results of the literature review

3.1 Distribution of published articles

3.1.1 Distribution of articles by year of publication

The distribution of articles included in this review by year of publication is shown in Fig. 1. This graph highlights that the number of publications investigating ERM effects in the context of entrepreneurial intentions and behavior has significantly increased over the years.

3.1.2 Distribution of articles by journals

Table 1 highlights the distribution of articles included in this review by journal. Articles related to role model effects in entrepreneurship are distributed across 56 journals. For the sake of clarity, we only included journals with more than one publication in our research area (ordered by number of articles published; journals that published the same number of articles are in alphabetical order). Of these, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice covers 8.1% and Small Business Economics 6.9% of the total number of articles investigated. Table 1 provides a list of journals that published two or more articles on entrepreneurial role models during this time period.

3.1.3 Contextual distribution of the articles

In terms of geographic distribution, the majority of articles included research conducted in the U.S. and Spain. The other articles mostly investigated European countries (mainly Germany, Sweden and Austria). A few studies conducted their research in Australia, Asian countries, New Zealand and South Africa. Fifteen studies used multicountry data—particularly data from different European countries and the U.S.—with the goal of identifying cross-cultural differences.

3.1.4 Dependent variables

We focused on papers using entrepreneurial intentions and behavior and included related constructs such as activities, attitudes, interest, motivation, career preference, entry, success, self-employment and new venture creation as outcome variables. The most commonly investigated dependent outcome is entrepreneurial intentions, which has been argued to be a strong predictor of actual behavior (Ajzen 1991). Forty-five papers focused on intentions, as they are often easier to measure than actual behavior (52%). The second most frequently examined outcome variable is behavioral outcomes (36%), which focus on such behavioral outcomes as entrepreneurial activity, entrepreneurial success, venture creation, self-employment transmission or self-employment and entrepreneurship transmission. A small number of papers (12%) investigated entrepreneurial attitude (3 papers), interest (3 papers), career preference (3 papers) and motivation (1 paper), which can be understood as precursors of intention and are therefore included in our review. Figure 2 summarizes the dependent variables investigated.

3.2 Entrepreneurial role model research areas

Individual preferences to engage in a particular kind of behavior are constantly influenced by the ideas and behavior of others, their expressions of identity and their displayed images (Ajzen 1991; Akerlof and Kranton 2000). These influences also affect people’s career choices (Krumboltz et al. 1976; Krueger Jr. et al. 2000; Douglas and Shepherd 2002). Researchers have argued that this behavior increases with the observational learning proficiency of the individual (Scott and Twomey 1988; Scherer et al. 1989b; Lent et al. 1994). Hackett and Betz (1981) find that by observing others, individuals learn how to make career decisions and act accordingly. This positive effect of observing others has also been found in the context of entrepreneurial intentions and behavior (e.g., Krueger Jr et al. 2000; Kuratko et al. 1997; Scherer et al. 1989a; Dalton and Holdaway 1989; Carroll and Mosakowski 1987; Scott and Twomey 1988; Bandura 1982). These ‘others’ can be understood as role models capable of influencing and shaping the behavior of the observer. More precisely, it has been argued that exposure to role models has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions by providing specific guidance and support or by creating an environment that triggers entrepreneurial behavior (BarNir et al. 2011).

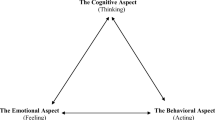

In addition, it has been found that role models can influence both the outcome expectancy and self-efficacy of the individual, which can encourage following a specific career path, such as becoming an entrepreneur (Lent et al. 1994; Nauta et al. 1998). Zapkau et al. (2017) investigated how prior entrepreneurial exposure influences entrepreneurial behavior. To find answers to this research question, the authors examined the results of 69 quantitative-empirical papers and classified them into four categories: process, individual, environment and organization. The effect of entrepreneurial role models is only part of their research question. In contrast to this study, we focus on the question of the effects of ERMs on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior, as research findings on ERM effects are rather fragmented and no consensus among researchers exists. The aim of our systematic literature review is to illustrate a concept-centric (Fisch and Block 2018), comprehensive overview of the current knowledge in a structured manner. Figure 3 illustrates the framework we used to summarize the existing research on role models in entrepreneurship.

Research in the first research stream focuses on ERMs’ existence in different contexts (26 papers, 30.2%). Papers in this group investigate three main areas: environment and culture, entrepreneurship programs and social context and stereotyping. The second research stream focuses on the types of role models (53 papers, 61.7%). In this category, articles investigate the effects of five different types of role models: family, similar models and peers, educators and mentors, successful versus unsuccessful models and unrelated models. The third category belongs to the stage of life where the exposure to role models occurred (when). In this research stream, articles focus on early role models in childhood and adolescence or they compare life cycle stages (7 papers, 8.1%).Footnote 2 The detailed distribution of articles classified by this framework is shown in Table 2.

3.2.1 Literature with a focus on the context (26 papers)

The entrepreneurial behavior of individuals is influenced not only by personal characteristics but also by the environment (Shane et al. 2003). Mitchell and Krumboltz (1984) propose that role models are an important contextual factor in building career intentions and making career choices. Role model literature focusing on contextual factors such as sociocultural aspects is concerned with the fact that the presence of entrepreneurs is one of the main factors promoting the creation of new ventures (Gnyawali and Fogel 1994; Bergmann and Sternberg 2007; Fornahl 2003; Sternberg 2009). A larger number of ERMs in a certain area can (unintentionally) inspire people to become entrepreneurs (Minniti 2005). More specifically, Dohse and Walter (2012) highlight that role models promote the transfer of explicit knowledge and provide ‘know-how’ and ‘know-who’ that influences entrepreneurial intentions. This influence can cultivate entrepreneurial intentions and encourage entrepreneurial actions because it provides access to information and resources and legitimizes entrepreneurial behavior (Davidsson and Wiklund 1997; Mueller 2006).

The majority of papers in this group focus solely on entrepreneurial intentions or their determinants (e.g., Toledano and Urbano 2008; Liñán and Chen 2009; Schmutzler et al. 2018; Dohse and Walter 2012). However, a few papers focus on such entrepreneurial behavior as entrepreneurial activities or venture creation (e.g., Noguera et al. 2013; Driga et al. 2009; Contín-Pilart and Larraza-Kintana 2015). This research stream can be divided into three categories: ‘environment and culture’ ‘entrepreneurship programs’ and ‘social context and stereotyping’.

3.2.1.1 Environment and culture (15 papers)

Entrepreneurial behavior is influenced at the microlevel by people’s access to individual resources and personal characteristics (e.g., Bhagavatula et al. 2010; Davidsson and Honig 2003; Shane et al. 2003) but also at the macrolevel by the environmental factors and institutions that encompass it (e.g., Autio and Acs 2010; Terjesen and Hessels 2009; Vaillant and Lafuente 2007; Shane et al. 2003). Papers in this category focus on the environment and culture that influence and support individuals in their entrepreneurial aspirations. More specifically, these papers are concerned with the influence of ERMs on entrepreneurial activities at the country and regional levels (Wyrwich et al. 2016).

De Clercq et al. (2013) examine the connection between people’s access to resources and their probability of being self-employed. They highlight that the context of a country influences both human capital (i.e., knowledge, skills and experience) and social capital, such as exposure to entrepreneurial role models (Arenius and Minnit 2005), and their effect on entrepreneurial intentions. Individuals receive situational and individual cues from their environment and translate perceived opportunities into venture creation.

Prior research found that sociocultural factors have an important impact on entrepreneurial intentions (Cullen et al. 2014; Autio et al. 2013) and that they are one of the most consequential causes of entrepreneurial behavior (Arenius and Minniti 2005; Koellinger et al. 2007). Living close to successful entrepreneurs not only has a positive effect on the likelihood that people start their own business, but also creates an entrepreneurial culture that generates knowledge and local acknowledgment for the community (Andersson and Larsson 2014; Dohse and Walter 2012).

To summarize, if entrepreneurs and observers live within the same geographical area, this effect has been found to be more pronounced (Wyrwich et al. 2018). The literature has shown that the existence of entrepreneurs in a region accelerates the development of the area’s venture creation (Andersson and Larsson 2014; Mueller 2006). It seems that the example of others ‘who have made it’ and their story has an inspiring effect and encourages others to create their own ventures. In addition, a high regional start-up enthusiasm appears to signal that a region is a suitable breeding ground for young ventures, which encourages potential entrepreneurs (Dohse and Walter 2012). This local atmosphere could facilitate entrepreneurial intentions, promote new entrepreneurial activities and help create an entrepreneurial network (Davidsson and Wiklund 1997; Mueller 2006).

The findings of the papers in this category explain some of the differences in entrepreneurial activity in different environments (e.g., Andersson and Larsson 2014; De Clercq et al. 2013; Dohse and Walter 2012; Schmutzler et al. 2018). Recommendations for public policy interventions are suggested by emphasizing the necessity to approve entrepreneurial surroundings to augment entrepreneurial behavior (Liñán et al. 2011). However, most of these studies depend on cross-sectional data that do not allow causality to be deduced or the common method bias to be eliminated (e.g., Lafuente et al. 2007; Driga et al. 2009; Contín-Pilart and Larraza-Kintana 2015). Table 3 summarizes the papers in this group.

3.2.1.2 Entrepreneurship programs (5 papers)

Papers in this group analyze the presence of role models in different entrepreneurial education programs and their influence on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. The existence of role models at universities has been shown to increase students’ tendency to pursue entrepreneurial attitudes (Fellnhofer and Puumalainen 2017; Mueller 2011) or to choose entrepreneurship as a career (Du Toit and Muofhe 2011; Rahman and Day 2014).

Research in this group not only emphasizes the positive effect of ERMs on the entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of students but also on increasing the awareness of entrepreneurship. Toledano and Urbano (2008) show that the evolution of an entrepreneurial aptitude among students is profoundly dependent on the existence of ERMs. Thus, they demand that ERMs be included in educational programs and that the advantages of self-employment be emphasized. This demand is also highlighted by Scott and Twomey (1988), who show that by providing students with contacts to ERMs, they can be stimulated to pursue business opportunities. In line with this idea, Block et al. (2017) argue that new types of entrepreneurial education initiatives are necessary to boost entrepreneurial intentions. Hence, bringing successful entrepreneurs (role models) to university courses or stimulating communication with local entrepreneurs could have a significant influence on entrepreneurial behavior (Toledano and Urbano 2008; Mueller 2011). The results of ERM research in entrepreneurship programs are summarized in Table 4.

3.2.1.3 Social context and stereotyping (6 papers)

Social context and ‘occupation stereotypes’ affect an individual’s career inclinations (Forsman and Barth 2017; Cundiff et al. 2013); therefore, individuals tend to involve themselves in ‘gender appropriate’ careers (BarNir et al. 2011). In these contexts, not surprisingly, women have less interest in ‘male-oriented’ careers (Johnson et al. 2008; Forsman and Barth 2017). Entrepreneurship has been argued to be a male-dominated area, which offers more chances for men (Ahl and Marlow 2012; Marlow 2002), and women experience more barriers, such as receiving financial support, to starting their own business (Akehurst et al. 2012). Although research shows these barriers to be different across countries (Engle et al. 2011), overall it has been found that women seem to have lower entrepreneurial intentions (Santos et al. 2016; Shinnar et al. 2012; Hundt and Sternberg 2016; Joensuu-Salo et al. 2015). Consequently, several scholars have argued that women have fewer entrepreneurial role models and less social support to become entrepreneurs than their male counterparts (Noguera et al. 2013; Dyer and Handler 1994). These studies suggest that providing women with early-age entrepreneurship education is the key to increasing their entrepreneurial intentions and to reducing the negative effects of stereotyping (Entrialgo and Iglesias 2018). To stimulate the entrepreneurial intentions and behavior of young women, Kickul et al. (2008) propose including female role models in women’s educational environment (e.g., as guest speakers). In line with this idea, more female role models for women are needed to promote women’s self-employment (Karimi et al. 2014; Noguera et al. 2013; Karimi et al. 2013). Prior research on social context and stereotyping is summarized in Table 5.

3.2.2 Literature with a focus on the types of role models (by whom) (53 papers)

Previous research has identified different types of role models (e.g., Chlosta et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2016; Austin and Nauta 2016; Falck et al. 2012) and shown that exposure to them reduces the ambiguity and concerns associated with entrepreneurship (Minniti 2005). Consequently, it is argued that not only the existence of role models is consequential but also the achievements of an entrepreneurial career conveyed by those role models (Davidsson 1995; Scherer et al. 1989a). For example, several findings emphasize that exposure to a successful ERM has a favorable impact on entrepreneurial behavior (e.g., Boissin et al. 2011; Boyd and Vozikis 1994; Brunel et al. 2017). This exposure has been argued to increase entrepreneurial intentions to start new businesses by facilitating information concerning attainable opportunities, by providing particular guidance and help, or by creating encouraging surroundings that foster entrepreneurial outcomes (BarNir et al. 2011). Prior literature has identified different types of role models and exposure to them, arguing that this exposure is positively related to entrepreneurial behavior. Most of the research in this group focuses on entrepreneurial intentions (e.g., Bosma et al. 2012; Geldhof et al. 2014; Laspita et al. 2012) and its antecedent entrepreneurial attitude (Fellnhofer 2017a, 2018) and related constructs, such as entrepreneurial interest (Matthews and Moser 1996; Wang and Wong 2004) and entrepreneurial career preference (Scherer et al. 1989a, 1991a). Only a small number of papers analyzed the impact on behavioral outcomes such as self-employment (Chlosta et al. 2012; Hoffmann et al. 2015) or venture creation activities (Hickie 2011). We identified 53 papers in total with a focus on the type of role model. Papers in this research stream can be divided into five subcategories: ‘Family’, ‘similar models and peers’, ‘educators and mentors’, ‘successful versus unsuccessful models’ and ‘unrelated models’.

3.2.2.1 Family (30 papers)

Parents are early role models for children in acquiring social values, habits and attitudes (Scherer et al. 1991b) and can act as negative or positive models for entrepreneurship (Morales-Alonso et al. 2016; Pablo-Lerchundi et al. 2015). Prior research suggests that having entrepreneurial parents affects the likelihood of entrepreneurial intentions (e.g., Geldhof et al. 2014; Chlosta et al. 2012; Wang and Wong 2004; Laspita et al. 2012; Saeed et al. 2014; Criaco et al. 2017; Andersson and Hammarstedt 2011; Niittykangas and Tervo 2005; Zapkau et al. 2015).

Hickie (2011) finds that entrepreneurial parents can constitute an advantage in developing relevant human capital but can also provide access to the values, knowledge and support of someone with experience. In addition, the presence of a parental entrepreneurial role model has been found to be associated with higher education and training ambitions, task self-efficacy, and an inclination toward entrepreneurial careers (Scherer et al. 1989b). This impact is independent of the parents’ existing social and economic conditions (Wyrwich 2015). Moreover, Mungai and Velamuri (2011) emphasize that parental impact is more prominent when the child is a young adult (18–21 years) compared to adolescence (12–17 years) or childhood (8–11 years). Furthermore, it has been revealed that individuals who take over businesses from their parents typically do engage in this transition at the beginning of their career (Blumberg and Pfann 2016).

In sum, researchers agree that self-employed parents strongly influence their children as ERMs, but it is not yet clear which factors moderate the link between parental entrepreneurship and their offspring’s entrepreneurial intentions (e.g., Geldhof et al. 2014; Schröder et al. 2011). Table 6 summarizes the research in this subcategory.

3.2.2.2 Similar models and peers (9 papers)

It has been found that opportunity recognition is enhanced by the perceived similarity between the individual and the ERM in terms of personal characteristics, skills, age, gender, and field of expertise (Wheeler et al. 2005; Wohlford et al. 2004), as well as values and ambitions (Filstad 2004). The observer is more likely to show imitative behavior when the perceived similarity is considerably high (Wilson et al. 2009; Scott 2009). According to Bosma et al. (2012), entrepreneurs and their role models have a propensity to imitate each other in relation to characteristics and attributes that simplify role identification, i.e., gender, sector and nationality. Following this line of reasoning, Bandura and Walters (1977), Bandura (1986) suggests that learning experiences are probably associated with escalating factors that affect the decision to start a business because of similarities between a role model and an observer in terms of specific characteristics such as gender. In line with this idea, Heckert et al. (2002) demonstrate that individuals are more likely to predicate their career prospects on information supplied from people with the same gender or the same ethnicity (Urbano et al. 2011). Consequently, previous studies showed the father as being the most influential role model for male offspring and the mother as being the most important role model for female offspring (Hoffmann et al. 2015; Lindquist et al. 2015). However, some researchers found that having a same-sex entrepreneurial role model is not inevitably associated with having stronger entrepreneurial intentions (Austin and Nauta 2016) and that sometimes women are even more likely to choose male role models (Wohlford et al. 2004). Considering the different research designs, methodologies and the contexts in which those studies have been conducted can provide some explanations for these mixed results.

On the other hand, since entrepreneurial behavior results from an individual’s socialization process, peers can have a strong influence on the entrepreneurial intentions of an individual (Falck et al. 2012; Kacperczyk 2013). Our review of the literature showed that researchers discuss two different kinds of peers in particular: school peers and coworkers. It has been found that employees are more likely to become self-employed if a colleague had previous self-employment experiences (Nanda and Sørensen 2010). Individuals learn from ‘established colleagues’ as ‘multiple contingent role models’ in organizational socialization processes (Filstad 2004). Furthermore, it has been shown that self-employment is an approved career possibility. Therefore, an individual’s fear of entrepreneurial failure diminishes when observing the role model (Wyrwich et al. 2016). Based on these findings, it has been argued that innovative behavior among employees can be transferred by training that motivates innovative behavior among their colleagues by performing as ERMs (Miao et al. 2018) and by creating an entrepreneurial culture (Huyghe and Knockaert 2015). The second identified peer group in this setting is school peers (Falck et al. 2012). Although prior research stresses the importance of early childhood experiences on cognitive and noncognitive capabilities (Heckman 2006; Cunha and Heckman 2007), only one paper investigates this relationship and discovers that having an entrepreneurial peer group at an early age (15 years old) can have a positive influence on an individual’s entrepreneurial intention (Falck et al. 2012). Table 7 summarizes the research in this subcategory.

3.2.2.3 Educators and mentors (2 papers)

The two papers in this group investigate the effect and role of educators and mentors in entrepreneurship education programs (Diegoli and Gutierrez 2018; Eesley and Wang 2017). Diegoli and Gutierrez (2018) examined the effect of an educator with previous entrepreneurial involvement. The authors find that when the educator has entrepreneurial experience, he has a greater impact on a specific group of students’ entrepreneurial intentions (i.e., students with converging learning styles). However, they conclude that it is impossible to determine if an educator’s specific characteristic or experience affects students’ entrepreneurial intentions; hence, students’ individual needs should be considered.

The second paper in this group (Eesley and Wang 2017) is a recent randomized field experiment that investigates the impact of mentors (entrepreneurs and nonentrepreneurs) on entrepreneurial behavior. Their results show that although entrepreneurial mentors had greater social influence compared to nonentrepreneurs, these mentors had an even greater impact on students with no family-related entrepreneurial history. They argue that having an entrepreneurial parent or peers with entrepreneurial experience is not possible for everyone, but that educational programs can foster entrepreneurial development by creating connections between individuals and entrepreneurial mentors. Table 8 summarizes the research in this subcategory.

3.2.2.4 Successful versus unsuccessful models (7 papers)

The literature has identified that successful and failed entrepreneurs are related to entrepreneurial intentions and emphasizes that individuals’ impression of their role model’s entrepreneurial outcomes should be observed (Boissin et al. 2011). It has been demonstrated that although successful role models create a higher perceived entrepreneurial feasibility (Krueger and Brazeal 1994) and that observing failed models can increase fear of failure (Boissin et al. 2011), exposure to unsuccessful entrepreneurs nevertheless increases entrepreneurial intentions (Chen et al. 2016). However, Scherer et al. (1989a) argue that people with ‘low-performing’ role models show entrepreneurial interest, but argue that their self-efficacy is lower than that of individuals exposed to ‘high-performing’ role models. In other words, individuals with successful role models enjoy a greater amount of self-efficacy (Boyd and Vozikis 1994) and have lower fear of failure (Wyrwich et al. 2018) due to their role models.

Gibson (2004) and Buunk and Gibson (2007) found that making ‘upward or downward comparisons’ with different types of role models has positive effects on entrepreneurial intentions (Brunel et al. 2017). In line with social comparison theory, they find that individuals usually make an ‘upward comparison’ with the model and believe they will be at least as successful as the model they observed. They find that exposure to either failed or successful entrepreneurs has a positive impact on individuals’ entrepreneurial intention (Brunel et al. 2017). Additionally, it is assumed that exposure to negative or ‘low-performing’ models creates a practical and rational view for observers and helps them to learn from the mistakes of others (Scherer et al. 1989a). Consequently, it is suggested that despite the usefulness of both successful and failed models in entrepreneurship education (Schwarz et al. 2009; Brunel et al. 2017), arranging exposure to successful entrepreneurs at early ages (elementary or secondary schools) is likely to increase entrepreneurial intentions, particularly in those groups of children without entrepreneurial parents (Scherer et al. 1989b). Table 9 summarizes the research in this subcategory.

3.2.2.5 Unrelated models (5 papers)

Few papers thus far have examined the effect of unrelated role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. One type of ‘unrelated role model’ can be found through narratives and storytelling about entrepreneurship. Fellnhofer (2017a) argues that although there has been a discussion among researchers about entrepreneurship education and its effects, the nondeniable effect of the opportunities provided by multimedia storytelling and narratives has been completely ignored. In this regard, the author conducted a quasi-experiment to compare the effects of real company cases with videos (Fellnhofer 2018). Results highlight that entrepreneurial feasibility is higher for groups who watched videos. In addition, Laviolette et al. (2012) show that observing a fictional role model—‘entrepreneurs’ testimonials and narratives’—positively influences entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions. They find that as long as role models provide the possibility for an individual to identify with them, they can stimulate a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship and increase entrepreneurial activities. They demonstrate that narratives positively affect attitudes toward entrepreneurship and individuals’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions. Moreover, the authors find that stories about successful fictional role models had greater effects compared to stories of unsuccessful ‘real-life’ role models. Therefore, it has been suggested that telling stories about entrepreneurs be used in entrepreneurship education programs to influence entrepreneurial intentions (Fellnhofer 2017b; Laviolette et al. 2012). In this respect, Radu and Loué (2008) suggest that using social media could create a greater impact if it exposes young generations to more similar idealistic (and realistic) role models instead of heroic role models that could fulfill social and/or family requirements. They find that if the narrative entrepreneur is more realistic, the observer will be more involved and consequently the effects are greater. Table 10 summarizes research in this subcategory.

3.2.3 Literature with a focus on the stage of life of the exposure (when) (7 papers)

Although there has been significant research on ERMs and their positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior, previous studies have largely ignored the evaluation of role models’ impacts on different stages of an individual’s life to determine whether these effects are stronger at certain ages (Mungai and Velamuri 2011). A large number of studies conclude that having entrepreneurial parents creates a greater chance of choosing an entrepreneurial career (e.g., Criaco et al. 2017; Kennedy et al. 2003; Scherer et al. 1991a, b; Scott and Twomey 1988). However, most of these studies examine the effects of parental role models in adulthood while at university (e.g., Díaz-García and Jiménez-Moreno 2010; Pruett et al. 2009; Pablo-Lerchundi et al. 2015; Dohse and Walter 2012). This research approach does not allow differentiating at which life stages the effects of the role models were particularly formative. Only a few papers investigate role models’ effects in early ages during adolescence (e.g., Obschonka et al. 2011; Rosique-Blasco et al. 2016) or differentiate between stages of life (Lafuente and Vaillant 2013). Considering the differences among role model influences over different age ranges (Lafuente and Vaillant 2013), we categorized papers in this group into childhood and adolescence and comparison of life cycle stages.

3.2.3.1 Childhood and adolescence (5 papers)

Only a small number of papers identified the impact of ERMs at early ages (e.g., Obschonka et al. 2011; Rosique-Blasco et al. 2016). Two of these papers evaluate role model effects on adolescents from 14 to 15 years old (Obschonka et al. 2011; Rosique-Blasco et al. 2016) and one examines the impact of entrepreneurial parents on late adolescents averaging 18 years of age (Schröder et al. 2011). All three studies find a significant influence of role models on career choice intentions or entrepreneurial success.

The other two studies in this subcategory use longitudinal data and investigate ERMs’ effects on entrepreneurial behavior (Sørensen 2007; Schoon and Duckworth 2012). Schoon and Duckworth (2012) show that having an entrepreneurial father had the greatest effect on male offspring, but for females, parents’ socioeconomic status had the greatest impact. In line with this finding, Sørensen (2007) shows that although ERMs had a significant influence on both male and female offspring, the effect was greater for males. Moreover, they conclude that having entrepreneurial parents during adolescence can positively shape an offspring’s inclination toward entrepreneurship. Considering the importance of having an entrepreneurial role model in general (Bosma et al. 2012) and during early ages in particular (Rosique-Blasco et al. 2016), it is suggested that entrepreneurial career intentions can be promoted by observing entrepreneurs during childhood and adolescence. In this regard, early entrepreneurship education programs could be a potential ‘seedbed’ for using ERMs to develop early entrepreneurial career intentions. Table 11 summarizes the research in this subcategory.

3.2.3.2 Comparison of life cycle stages (2 papers)

Most of the research on ERMs focuses on either their impact in various contexts or on the different types of role models but does not differentiate among the effects of role models across different life stages (Mungai and Velamuri 2011). Only two papers investigate this research question. Lafuente and Vaillant (2013) examine role models’ effects on entrepreneurial behavior at different stages of an individuals’ life (18–45 years old) and find that entrepreneurial role models had greater effects on younger adults and the smallest effect on older individuals (Lafuente and Vaillant 2013). The second paper, by Mungai and Velamuri (2011), examines role models’ impact during three different stages of life (late childhood, adolescence and young adulthood). Young adulthood in this research was defined as being between 18 and 21 years. The authors find that the effect of ERMs is greater when the observer is a young adult. Since there are only two papers in this group and they had different target sample ages, no clear picture can be obtained from their findings. This limitation illustrates an important gap in the literature. Table 12 summarizes the research in this subcategory.

4 Summary, open research questions and limitations

In this study, we conducted a systematic review of the current literature on role model effects in an entrepreneurship context. We developed a framework for categorizing the various research topics of the 86 papers on ERMs investigated in our study. We differentiate among three main research streams: in which context/where, by whom and when the exposure to ERMs occurs. The first category, in which context/where, can be subdivided into research on environment and culture, entrepreneurship programs, and social context and stereotyping. Prior research investigating different types of ERMs (by whom) and their different impact on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior can be divided into research about family, similar role models and peers, educators and mentors, successful versus unsuccessful role models and unrelated models. The third research stream is focused on the stage of life at which exposure to ERMs occurs (when) and can be categorized in two groups: childhood and adolescence and comparison of life cycle stages.

Our review highlights that ERMs’ emergence and their effects vary among different environments. Regions with a high degree of entrepreneurial activities create more ERMs and consequently further increase entrepreneurial activity. Observing others increases the feasibility of starting a business and motivates more people to do so. In addition, prior research suggests that entrepreneurship programs are important for entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. Furthermore, it has been shown that social context and stereotyping have a significant effect on entrepreneurial activity.

Furthermore, we shed light on the different types of ERMs and their role as an important influencing factor in starting a business. Prior research suggests that the type of role model (by whom) has various effects on observers’ entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. In addition, the relationship between the ERM and the individual affects the attitude toward entrepreneurship. In particular, the type of role model (i.e., similar models and peers, as well as their success) can have a significant influence on an individual’s entrepreneurial intention and behavior.

Altogether, the results of our literature review reveal that it matters in which context, by whom, how and when the exposure to role models occurs. Based on these findings, we identify different research gaps and propose ideas for future research.

4.1 Research questions focusing on the context/where

-

Does exposure to ERMs have different effects in various cultural contexts? How does this affect entrepreneurial intentions and behavior?

Research on the effects of ERMs on individuals in different cultural environments remains scarce. This is, however, an important research area (Wyrwich et al. 2016; Engle et al. 2011; Reavley and Lituchy 2008) because culture comprises mutual values, beliefs, and anticipated behaviors (Hofstede 1980). It also includes comparable patterns of thoughts, feelings and activities (Hofstede et al. 2005). Consequently, the behavior of individuals is affected by their cultural values and social norms. This effect is also true in terms of entrepreneurial behavior (Krueger et al. 2013). For example, research examining women entrepreneurs in different cultures highlights that women’s social status varies significantly among cultures (Reavley and Lituchy 2008; Ramadani et al. 2013; Lee 1996), which directly affects their intention to start a business (Schoon and Duckworth 2012).

We propose to intensify future research in two ways. First, we suggest investigating the effect of ERMs in different countries with different sociocultural systems and, second, investigating the effect of ERMs on entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors in these different environments. Answering these research questions can help better understand how ERMs work in different countries with different sociocultural systems. Furthermore, knowledge about this relationship can also provide a better understanding of how ERMs affect individuals with different cultural backgrounds.

-

Does exposure to ERMs have different effects in various social contexts with different stereotypes? How do stereotypes affect entrepreneurial intentions and behavior?

Gender stereotypes are individuals’ common knowledge and perceptions, which are identified as being aspects and characteristics of each gender (Powell and Graves 2003). Previous studies reveal that social context and stereotypes affect individuals’ occupational choice (Johnson et al. 2008). Moreover, stereotypes have greater effects on female entrepreneurial career intentions (Engle et al. 2011). BarNir et al. (2011) found that role models affect female entrepreneurial self-efficacy more than they affect male entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

Individuals socialize and are affected by stereotypes in their culture (Gupta et al. 2009). Entrepreneurship is known as a male-dominated area and critical challenges have been identified for women (Hamilton 2013; Ogbor 2000). Women’s behavior is closely linked to their surrounding institutions and to women’s position in society (e.g., BarNir et al. 2011; Díaz-García and Jiménez-Moreno 2010; Koellinger et al. 2013; Minniti and Nardone 2007). Thus, the presence of role models can possibly abate gender stereotypes (Fagenson and Marcus 1991; Rivera et al. 2007). Hence, future research could investigate which social stereotypes affect entrepreneurial intentions and behavior, and how they do so. Moreover, one could examine how these stereotypes affect the relationship between ERMs and entrepreneurial intentions and behavior in different contexts.

4.2 Research questions focusing on types of role models (by whom)

-

How does the entrepreneurial orientation of ERMs affect individuals’ entrepreneurial intentions and behavior?

From the literature, we know that there are various types of ERMs (e.g., Bosma et al. 2012; Laviolette et al. 2012; Boissin et al. 2011) and that these different types of role models affect entrepreneurial intentions and behavior differently (e.g., Schoon and Duckworth 2012; Eesley and Wang 2017; Nanda and Sørensen 2010).

However, prior studies do not allow us to draw clear conclusions regarding the question of which types of ERMs have the strongest effect on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior (Davidsson 1995; Scherer et al. 1989a). In particular, they do not take the entrepreneurial orientation of the ERMs into account. Hence, it would be very revealing to investigate whether ERMs with different entrepreneurial orientations have different effects on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. For example, it would be interesting to investigate whether individuals react differently to social or profit-oriented ERMs.

-

Does similarity (e.g., gender, race, and nationality) between individuals and their role models affect entrepreneurial intentions and behavior? Do children and adolescents react differently than do adults to similar role models?

Previous studies show that role models are more effective when individuals and role models share the same gender or racial group (e.g., Marx et al. 2009; Lockwood 2006; Marx and Goff 2005). This finding is explained by the fact that similar role models inspire the belief that individuals can overcome uncertainties and risks associated with a specific task (Marx et al. 2005; Lockwood and Kunda 1997). For example, prior research suggests that direct exposure to female ERMs can strengthen the entrepreneurial self-efficacy of women (Dempsey and Jennings 2014). Hence, a deeper knowledge of the similarity effect of ERMs can help identify fitting role models and integrate this knowledge into entrepreneurship programs, such as mentoring and coaching, to facilitate entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. Furthermore, it would be interesting to see if this effect depends on the individual’s age.

-

What are ERMs’ effects on the individuals’ actual entrepreneurial behavior?

Our literature review reveals that past studies mainly used cross-sectional research designs (e.g., Lafuente et al. 2007; Díaz-García and Jiménez-Moreno 2010; Karimi et al. 2014; Lafuente and Vaillant 2013; Criaco et al. 2017; Laspita et al. 2012). Although this design fits the datasets and surveys used, it does not allow to assess longer-term effects and actual entrepreneurial behavior (e.g., Fellnhofer 2018; Huyghe and Knockaert 2015; Laviolette et al. 2012; Du Toit and Muofhe 2011). Longitudinal data could help close this gap and not only measure entrepreneurial intentions but also investigate actual behavior (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Karimi et al. 2014).

4.3 Research questions focusing on when the exposure occurs

-

How can exposure to ERMs in entrepreneurship programs for children and adolescents affect their entrepreneurial attitude?

Prior research has found that the integration of role models into educational programs has a positive effect on entrepreneurial career intentions (Scott and Twomey 1988) and that this effect is even stronger in unfavorable environments (Walter and Block 2016) such as those with a bureaucratic legal system (Lim et al. 2010) or low property rights (McMullen et al. 2008). However, our literature review reveals that there is, to the best of our knowledge, no research on ERMs’ effects on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions in early entrepreneurship education (primary and secondary schools). Most studies tend to focus on adults (Fellnhofer and Puumalainen 2017) in higher education, such as university students (e.g., Du Toit and Muofhe 2011; Mueller 2011; Toledano and Urbano 2008; Rahman and Day 2014). None of the studies investigate younger ages, even though the importance of early childhood programs to adult behavior has been acknowledged in many disciplines, such as research on labor markets (e.g., Heckman et al. 2013), cognitive and social development (Camilli et al. 2010) and career choice intentions (Schröder et al. 2011). However, Obschonka et al. (2011) provide the first insights into this relationship in the entrepreneurship context and argue that childhood and adolescent experiences are important for later venture creation. Hence, future research focusing on early entrepreneurship education could improve our understanding of these interdependencies.

4.4 Limitations

The results from our review must be considered in light of some limitations. Despite our extensive efforts, the literature search may not have captured all research related to role models and entrepreneurship. First, our in-depth content analysis was based on a keyword search and is therefore limited by the search keywords we selected. To decrease this risk, we expanded our search to keywords used in the articles that we identified and conducted a backward search. Second, we only focused on peer-reviewed articles and ignored, for example, book chapters. Third, our review is limited to articles published in English. Although this procedure is accepted practice, it should be noted that non-English articles were excluded from our literature search.

5 Conclusion

We conducted a systematic review of the literature investigating the effects of ERMs on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior. Our research was motivated by the fact that although numerous studies have investigated the efficacy of ERMs, their findings are ambiguous and the literature is rather fragmented. Our aim was to structure the existing research, identify research gaps and identify areas for future research. Altogether, our study contributes to the entrepreneurship and ERM literature in various ways. First, we provide a framework and categorize the 86 publications focusing on ERMs and their effect on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior that were identified since the first publications appeared in 1988 until the end of March 2019. We identify three main research streams, differentiating among in which context, by whom and at which stage of life the exposure to role models occurs. The context (where) can be divided into 3 subcategories: ‘environment and culture’, ‘entrepreneurship programs’ and ‘social context and stereotyping’. The research on different types of role models (by whom) comprises papers focusing on family, similar models and peers, educators and mentors, successful versus unsuccessful models and unrelated models. The third research stream focuses on the stage of life at which the exposure to the ERM occurs. In this group, papers are categorized in two groups: childhood and adolescence and comparison of life cycle stages.

Our approach enabled us to identify research gaps in current ERM research. Based on these gaps, we provide future research questions that can help increase our understanding of the effects of ERMs on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior.

Second, our findings contribute to the entrepreneurship literature by demonstrating that entrepreneurial intentions and behavior are affected by exposure to role models. In particular, we find that this effect depends on by whom, when and in which context the exposure to role models occurs.

Third, by highlighting that the integration of role models in entrepreneurial education programs, particularly at early ages, could increase entrepreneurial intentions and behavior, we also contribute to the discussion of entrepreneurial education. We provide evidence from prior research showing that implementing suitable role models in entrepreneurship programs can help foster entrepreneurial activities. This knowledge is particularly relevant for policy makers and educators fostering entrepreneurial education programs, as it provides ideas about how to structure these programs and how to include ERMs effectively. In particular, policy makers and educators should consider aspects such as the stage of life, gender, peer groups, and prior experience or individual contexts while structuring and implementing entrepreneurship programs and initiatives.

Notes

The search was conducted between mid-July 2018 and mid-April 2019.

However, it should be noted that the categories are not mutually exclusive. We have assigned the papers according to their main focus.

References

Ahl H, Marlow S (2012) Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism and entrepreneurship: advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization 19(5):543–562

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211

Akehurst G, Simarro E, Mas-Tur A (2012) Women entrepreneurship in small service firms: motivations, barriers and performance. Serv Ind J 32(15):2489–2505

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ 115(3):715–753

Andersson L, Hammarstedt M (2011) Transmission of self-employment across immigrant generations: the importance of ethnic background and gender. Rev Econ Househ 9(4):555–577.*

Andersson M, Larsson JP (2014) Local entrepreneurship clusters in cities. J Econ Geogr 16(1):39–66.*

Arenius P, Minniti M (2005) Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 24(3):233–247

Austin MJ, Nauta MM (2016) Entrepreneurial role-model exposure, self-efficacy, and women’s entrepreneurial intentions. J Career Dev 43(3):260–272.*

Autio E, Acs Z (2010) Intellectual property protection and the formation of entrepreneurial growth aspirations. Strateg Entrepr J 4(3):234–251

Autio E, Pathak S, Wennberg K (2013) Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviours. J Int Bus Stud 44(4):334–362

Bandura A (1982) Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 37(2):122

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Bandura A, Walters RH (1977) Social learning theory, vol 1. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

BarNir A, Watson WE, Hutchins HM (2011) Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. J Appl Soc Psychol 41(2):270–297.*

Baron RA (2004) The cognitive perspective: a valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship’s basic “why” questions. J Bus Ventur 19(2):221–239

Bergmann H, Sternberg R (2007) The changing face of entrepreneurship in Germany. Small Bus Econ 28(2–3):205–221

Bhagavatula S, Elfring T, Van Tilburg A, Van De Bunt GG (2010) How social and human capital influence opportunity recognition and resource mobilization in India’s handloom industry. J Bus Ventur 25(3):245–260

Block JH, Hoogerheide L, Thurik R (2013) Education and entrepreneurial choice: an instrumental variables analysis. Int Small Bus J 31(1):23–33

Block JH, Fisch CO, Van Praag M (2017) The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: a review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Ind Innov 24(1):61–95

Blumberg BF, Pfann GA (2016) Roads leading to self-employment: comparing transgenerational entrepreneurs and self-made start–ups. Entrep Theory Pract 40(2):335–357

Boissin JP, Branchet B, Delanoë S, Velo V (2011) Gender’s perspective of role model influence on entrepreneurial behavioural beliefs. Int J Bus 16(2):182.*

Bosma N, Hessels J, Schutjens V, Van Praag M, Verheul I (2012) Entrepreneurship and role models. J Econ Psychol 33(2):410–424.*

Boyd NG, Vozikis GS (1994) The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep Theory Pract 18(4):63–77.*

Brunel O, Laviolette EM, Radu-Lefebvre M (2017) Role models and entrepreneurial intention: the moderating effects of experience, locus of control and self-esteem. J Enterp Cult 25(02):149–177.*

Buunk AP, Gibbons FX (2007) Social comparison: the end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 102(1):3–21

Camilli G, Vargas S, Ryan S, Barnett WS (2010) Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teach Coll Rec 112(3):579–620

Capelleras JL, Contin-Pilart I, Larraza-Kintana M, Martin-Sanchez V (2019) Entrepreneurs’ human capital and growth aspirations: the moderating role of regional entrepreneurial culture. Small Bus Econ 52(1):3–25

Caputo RK, Dolinsky A (1998) Women’s choice to pursue self-employment: the role of financial and human capital of household members. J Small Bus Manag 36(3):8.*

Carr JC, Sequeira JM (2007) Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: a theory of planned behaviour approach. J Bus Res 60(10):1090–1098

Carroll GR, Mosakowski E (1987) The career dynamics of self-employment. Adm Sci Q 32:570–589

Chen N, Ding G, Li W (2016) Do negative role models increase entrepreneurial Intentions? The moderating role of self-esteem. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 38(6):337–350.*

Chlosta S, Patzelt H, Klein SB, Dormann C (2012) Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: the moderating effect of personality. Small Bus Econ 38(1):121–138.*

Contín-Pilart I, Larraza-Kintana M (2015) Do entrepreneurial role models influence the nascent entrepreneurial activity of immigrants? J Small Bus Manag 53(4):1146–1163.*

Criaco G, Sieger P, Wennberg K, Chirico F, Minola T (2017) Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword” for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 49(4):841–864.*

Cullen JB, Johnson JL, Parboteeah KP (2014) National rates of opportunity entrepreneurship activity: insights from institutional anomie theory. Entrep Theory Pract 38(4):775–806

Cundiff JL, Vescio TK, Loken E, Lo L (2013) Do gender–science stereotypes predict science identification and science career aspirations among undergraduate science majors? Soc Psychol Educ 16(4):541–554

Cunha F, Heckman J (2007) The technology of skill formation. Am Econ Rev 97(2):31–47

Dalton G, Holdaway F (1989) Preliminary findings—entrepreneur study. Working paper, Department of Organization Behaviour, Brigham Young University

Davidsson P (1995) Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions. In: RENT IX workshop in entrepreneurship research, Piacenza, Italy, 23–24 November

Davidsson P, Honig B (2003) The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J Bus Ventur 18(3):301–331

Davidsson P, Wiklund J (1997) Values, beliefs and regional variations in new firm formation rates. J Econ Psychol 18(2–3):179–199

De Clercq D, Lim DS, Oh CH (2013) Individual-level resources and new business activity: the contingent role of institutional context. Entrep Theory Pract 37(2):303–330.*

Dempsey D, Jennings J (2014) Gender and entrepreneurial self-efficacy: a learning perspective. Int J Gender Entrep 6(1):28–49

Díaz-García MC, Jiménez-Moreno J (2010) Entrepreneurial intention: the role of gender. Int Entrep Manag J 6(3):261–283.*

Diegoli RB, Gutierrez HSM (2018) Teachers as entrepreneurial role models the impact of a teacher’s entrepreneurial experience and student learning styles in entrepreneurial intentions. J Entrep Educ 21(1):1–11.*

Dohse D, Walter SG (2012) Knowledge context and entrepreneurial intentions among students. Small Bus Econ 39(4):877–895.*

Douglas EJ, Shepherd DA (2002) Self-employment as a career choice: attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrep Theory Pract 26(3):81–90

Driga O, Lafuente E, Vaillant Y (2009) Reasons for the relatively lower entrepreneurial activity levels of rural women in Spain. Sociol Rural 49(1):70–96.*

Du Toit WF, Muofhe NJ (2011) Entrepreneurial education’s and entrepreneurial role models’ influence on career choice. SA J Hum Resour Manag 9(1):1–15.*

Dyer WG Jr, Handler W (1994) Entrepreneurship and family business: exploring the connections. Entrep Theory Pract 19(1):71–83

Eesley C, Wang Y (2017) Social influence in career choice: evidence from a randomized field experiment on entrepreneurial mentorship. Res Pol 46(3):636–650.*

Engle RL, Schlaegel C, Delanoe S (2011) The role of social influence, culture, and gender on entrepreneurial intent. J Small Bus Entrep 24(4):471–492.*

Entrialgo M, Iglesias V (2018) Are the intentions to entrepreneurship of men and women shaped differently? The impact of entrepreneurial role-model exposure and entrepreneurship education. Entrep Res J 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2017-0013

Fagenson EA, Marcus EC (1991) Perceptions of the sex-role stereotypic characteristics of entrepreneurs: women’s evaluations. Entrep Theory Pract 15(4):33–48

Falck O, Heblich S, Luedemann E (2012) Identity and entrepreneurship: Do school peers shape entrepreneurial intentions? Small Bus Econ 39(1):39–59.*

Fellnhofer K (2017a) A framework for a teaching toolkit in entrepreneurship education. Int J Contin Eng Educ Life Long Learn 27(3):246–261.*

Fellnhofer K (2017b) The power of passion in entrepreneurship education: entrepreneurial role models encourage passion? J Entrep Educ 20(1):58.*

Fellnhofer K (2018) Narratives boost entrepreneurial attitudes: Making an entrepreneurial career attractive? Eur J Educ 53(2):218–237.*

Fellnhofer K, Puumalainen K (2017) Can role models boost entrepreneurial attitudes? Int J Entrep Innov Manag 21(3):274–290.*

Filstad C (2004) How newcomers use role models in organizational socialization. J Workplace Learn 16(7):396–409

Fisch C, Block J (2018) Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag Rev Q 68(2):103–106

Fornahl D (2003) Entrepreneurial activities in a regional context. Cooperation, networks and institutions in regional innovation systems. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 38–57

Forsman JA, Barth JM (2017) The effect of occupational gender stereotypes on men’s interest in female-dominated occupations. Sex Roles 76(7–8):460–472

Galloway L, Kelly SW (2009) Identifying entrepreneurial potential? An investigation of the identifiers and features of entrepreneurship. Int Rev Entrep 7(4):1–24

Geldhof GJ, Weiner M, Agans JP, Mueller MK, Lerner RM (2014) Understanding entrepreneurial intent in late adolescence: the role of intentional self-regulation and innovation. J Youth Adolesc 43(1):81–91.*

Gibson DE (2004) Role models in career development: new directions for theory and research. J Vocat Behav 65(1):134–156

Gnyawali DR, Fogel DS (1994) Environments for entrepreneurship development: key dimensions and research implications. Entrep Theory Pract 18(4):43–62.*

Guiso L, Pistaferri L, Schivardi F (2015) Learning entrepreneurship from other entrepreneurs? (No. w21775). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge.*

Gupta VK, Turban DB, Wasti SA, Sikdar A (2009) The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrep Theory Pract 33(2):397–417

Hackett G, Betz NE (1981) A self-efficacy approach to the career development of women. J Voc Behav 18(3):326–339

Hamilton E (2013) The discourse of entrepreneurial masculinities (and femininities). Entrep Reg Dev 25(1–2):90–99

Heckert TM, Droste HE, Adams PJ, Griffin CM, Roberts LL, Mueller MA, Wallis HA (2002) Gender differences in anticipated salary: role of salary estimates for others, job characteristics, career paths, and job inputs. Sex Roles 47(3–4):139–151

Heckman JJ (2006) Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 312(5782):1900–1902

Heckman J, Pinto R, Savelyev P (2013) Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult behaviour. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2052–2086

Hickie J (2011) The development of human capital in young entrepreneurs. Ind High Educ 25(6):469–481.*

Hoffmann A, Junge M, Malchow-Møller N (2015) Running in the family: parental role models in entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 44(1):79–104.*

Hofstede GH (1980) Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Sage, Newbury Park

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2005) Cultures and organizations: software of the mind, vol 2. Mcgraw-hill, New York

Hundt C, Sternberg R (2016) Explaining new firm creation in Europe from a spatial and time perspective: a multilevel analysis based upon data of individuals, regions and countries. Pap Reg Sci 95(2):223–257

Huyghe A, Knockaert M (2015) The influence of organizational culture and climate on entrepreneurial intentions among research scientists. J Technol Transf 40(1):138–160.*

Jaén I, Liñán F (2013) Work values in a changing economic environment: the role of entrepreneurial capital. Int J Manpow 34(8):939–960.*

Joensuu-Salo S, Varamäki E, Viljamaa A (2015) Beyond intentions—What makes a student start a firm? Educ Train 57(8/9):853–873

Johnson RD, Stone DL, Phillips TN (2008) Relations among ethnicity, gender, beliefs, attitudes, and intention to pursue a career in information technology. J Appl Soc Psychol 38(4):999–1022

Jones MV, Coviello N, Tang YK (2011) International entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): a domain ontology and thematic analysis. J Bus Ventur 26(6):632–659

Kacperczyk AJ (2013) Social influence and entrepreneurship: the effect of university peers on entrepreneurial entry. Organ Sci 24(3):664–683.*

Karimi S, Biemans HJ, Lans T, Chizari M, Mulder M, Mahdei KN (2013) Understanding role models and gender influences on entrepreneurial intentions among college students. Proc Soc Behav Sci 93:204–214

Karimi S, Biemans JA, Lans H, Chizari T, Mulder M (2014) Effects of role models and gender on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Eur J Train Dev 38(8):694–727.*

Kennedy J, Drennan J, Renfrow P, Watson B (2003) The influence of role models on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Qld Rev 10(1):37–52.*

Kickul J, Wilson F, Marlino D, Barbosa SD (2008) Are misalignments of perceptions and self-efficacy causing gender gaps in entrepreneurial intentions among our nation’s teens? J Small Bus Enterp Dev 15(2):321–335.*

Kirkwood J (2007) Igniting the entrepreneurial spirit: Is the role parents play gendered? Int J Entrep Behav Res 13(1):39–59.*

Koellinger P, Minniti M, Schade C (2007) “I think I can, I think I can”: overconfidence and entrepreneurial behaviour. J Econ Psychol 28(4):502–527

Koellinger P, Minniti M, Schade C (2013) Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 75(2):213–234

Kolvereid L (1996) Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrep Theory Pract 21(1):47–58

Krueger NF Jr, Brazeal DV (1994) Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep Theory Pract 18(3):91–104

Krueger NF, Carsrud AL (1993) Entrepreneurial intentions: applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrep Reg Dev 5(4):315–330.*

Krueger NF Jr, Reilly MD, Carsrud AL (2000) Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J Bus Ventur 15(5–6):411–432.*

Krueger N, Liñán F, Nabi G (2013) Cultural values and entrepreneurship. Entrep Reg Dev Int J 25(9–10):703–707

Krumboltz JD, Mitchell AM, Jones GB (1976) A social learning theory of career selection. Couns Psychol 6(1):71–81

Kuratko DF, Hornsby JS, Naffziger DW (1997) An examination of owner’s goals in sustaining entrepreneurship. J Small Bus Manag 35(1):24

Lafuente EM, Vaillant Y (2013) Age driven influence of role-models on entrepreneurship in a transition economy. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 20(1):181–203.*

Lafuente E, Vaillant Y, Rialp J (2007) Regional differences in the influence of role models: comparing the entrepreneurial process of rural Catalonia. Reg Stud 41(6):779–796.*

Laspita S, Breugst N, Heblich S, Patzelt H (2012) Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. J Bus Ventur 27(4):414–435.*

Laviolette EM, Radu Lefebvre M, Brunel O (2012) The impact of story bound entrepreneurial role models on self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int J Entrep Behav Res 18(6):720–742.*

Lee J (1996) The motivation of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women Manag Rev 11(2):18–29

Lent RW, Brown SD, Hackett G (1994) Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J Voc Behav 45(1):79–122

Levy Y, Ellis TJ (2006) A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research. Inf Sci J 9:181–212

Lim DS, Morse EA, Mitchell RK, Seawright KK (2010) Institutional environment and entrepreneurial cognitions: a comparative business systems perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 34(3):491–516

Liñán F, Chen YW (2009) Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep Theory Pract 33(3):593–617.*

Liñán F, Santos FJ (2007) Does social capital affect entrepreneurial intentions? Int Adv Econ Res 13(4):443–453.*

Liñán F, Urbano D, Guerrero M (2011) Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrep Reg Dev 23(3–4):187–215

Lindquist MJ, Sol J, Van Praag M (2015) Why do entrepreneurial parents have entrepreneurial children? J Labor Econ 33(2):269–296.*

Lockwood P (2006) “Someone like me can be successful”: do college students need same-gender role models? Psychol Women Q 30(1):36–46

Lockwood P, Kunda Z (1997) Superstars and me: predicting the impact of role models on the self. J Pers Soc Psychol 73:91–103

Marlow S (2002) Women and self-employment: a part of or apart from theoretical construct? Int J Entrep Innov 3(2):83–91

Marx DM, Goff PA (2005) Clearing the air: the effect of experimenter race on target’s test performance and subjective experience. Br J Soc Psychol 44(4):645–657

Marx DM, Stapel DA, Muller D (2005) We can do it: the interplay of a collective self-construal orientation and social comparisons under threat. J Pers Soc Psychol 88:432–446

Marx DM, Ko SJ, Friedman RA (2009) The “Obama effect”: how a salient role model reduces race-based performance differences. J Exp Soc Psychol 45(4):953–956

Mathews CH, Moser SB (1995) Family background and gender: implications for interest in small firm ownership. Entrep Reg Dev 7(4):365–378.*

Matthews CH, Moser SB (1996) A longitudinal investigation of the impact of family background. J Small Bus Manag 34:29–43.*

McClelland DC (1965) N achievement and entrepreneurship: a longitudinal study. J Pers Soc Psychol 1(4):389

McMullen JS, Bagby DR, Palich LE (2008) Economic freedom and the motivation to engage in entrepreneurial action. Entrep Theory Pract 32(5):875–895

Miao Q, Newman A, Schwarz G, Cooper B (2018) How leadership and public service motivation enhance innovative behaviour. Publ Adm Rev 78(1):71–81

Minniti M (2005) Entrepreneurship and network externalities. J Econ Behav Organ 57(1):1–27.*

Minniti M, Nardone C (2007) Being in someone else’s shoes: the role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 28(2–3):223–238

Mitchell LK, Krumboltz JD (1984) Social learning approach to career decision making: Krumboltz’s theory. In: Brown D, Brooks L (eds) Career choice and development. JosseyBass, San Francisco

Morales-Alonso G, Pablo-Lerchundi I, Vargas-Perez AM (2016) An empirical study on the antecedents of knowledge intensive entrepreneurship. Int J Innov Technol Manag 13(05):1640011.*

Mueller P (2006) Entrepreneurship in the region: breeding ground for nascent entrepreneurs? Small Bus Econ 27(1):41–58

Mueller S (2011) Increasing entrepreneurial intention: effective entrepreneurship course characteristics. Int J Entrep Small Bus 13(1):55–74.*

Mueller PS, Murali NS, Cha SS, Erwin PJ, Ghosh AK (2006) The association between impact factors and language of general internal medicine journals. Swiss Med Wkl 136(27–28):441

Mungai E, Velamuri SR (2011) Parental entrepreneurial role model influence on male offspring: Is it always positive and when does it occur? Entrep Theory Pract 35(2):337–357.*

Nanda R, Sørensen JB (2010) Workplace peers and entrepreneurship. Manag Sci 56(7):1116–1126.*

Nauta MM, Epperson DL, Kahn JH (1998) A multiple-groups analysis of predictors of higher level career aspirations among women in mathematics, science, and engineering majors. J Couns Psychol 45(4):483

Niittykangas H, Tervo H (2005) Spatial variations in intergenerational transmission of self-employment. Reg Stud 39(3):319–332.*

Noguera M, Alvarez C, Urbano D (2013) Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. Int Entrep Manag J 9(2):183–197.*

Nowiński W, Haddoud MY (2019) The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. J Bus Res 96:183–193.*

Obschonka M, Silbereisen RK, Schmitt-Rodermund E (2011) Successful entrepreneurship as developmental outcome: a path model from a lifespan perspective of human development. Eur Psychol 16(3):174.*

Ogbor JO (2000) Mythicizing and reification in entrepreneurial discourse: ideology-critique of entrepreneurial studies. J Manag Stud 37(5):605–635

Pablo-Lerchundi I, Morales-Alonso G, González-Tirados RM (2015) Influences of parental occupation on occupational choices and professional values. J Bus Res 68(7):1645–1649.*

Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Bachrach DG, Podsakoff NP (2005) The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strateg Manag J 26(5):473–488

Powell GN, Graves LM (2003) Women and men in management. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Pruett M, Shinnar R, Toney B, Llopis F, Fox J (2009) Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: a cross-cultural study. Int J Entrep Behav Res 15(6):571–594.*

Radu M, Loué C (2008) Motivational impact of role models as moderated by” ideal” vs.” ought self-guides” identifications. J Enterp Cult 16(04):441–465.*

Rahman H, Day J (2014) Involving the entrepreneurial role model: a possible development for entrepreneurship education. J Entrep Educ 17(2):163–171.*

Ramadani V, Gërguri S, Dana LP, Tašaminova T (2013) Women entrepreneurs in the Republic of Macedonia: waiting for directions. Int J Entrep Small Bus 19(1):95–121

Reavley MA, Lituchy TR (2008) Successful women entrepreneurs: a six-country analysis of self-reported determinants of success-more than just dollars and cents. Int J Entrep Small Bus 5(3):272.*

Rivera LM, Chen EC, Flores LY, Blumberg F, Ponterotto JG (2007) The effects of perceived barriers, role models, and acculturation on the career self-efficacy and career consideration of Hispanic women. Career Dev Q 56(1):47–61

Robinson PB, Stimpson DV, Huefner JC, Hunt HK (1991) An attitude approach to the prediction of entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 15(4):13–32

Robinson S, Neergaard H, Tanggaard L, Krueger NF (2016) New horizons in entrepreneurship education: from teacher-led to student-centered learning. Educ Train 58(7/8):661–683

Rosique-Blasco M, Madrid-Guijarro A, García-Pérez-de-Lema D (2016) Entrepreneurial skills and socio-cultural factors: an empirical analysis in secondary education students. Educ Train 58(7/8):815–831.*

Saeed S, Muffatto M, Yousafzai SY (2014) Exploring intergenerational influence on entrepreneurial intention: the mediating role of perceived desirability and perceived feasibility. Int J Entrep Innov Manag 18(2–3):134–153.*

Santos FJ, Roomi MA, Liñán F (2016) About gender differences and the social environment in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J Small Bus Manag 54(1):49–66

Scherer RF, Adams JS, Carley SS, Wiebe FA (1989a) Role model performance effects on development of entrepreneurial career preference. Entrep Theory Pract 13(3):53–72.*

Scherer R, Adams J, Wiebe F (1989b) Developing entrepreneurial behaviours: a social learning theory perspective. J Organ Change Manag 2:16–28.*

Scherer RF, Brodzinski JD, Wiebe F (1991a) Examining the relationship between personality and entrepreneurial career preference. Entrep Reg Dev 3(2):195–206.*

Scherer RF, Brodzinski JD, Goyer KA, Wiebe FA (1991b) Shaping the desire to become an entrepreneur: parent and gender influences. J Bus Entrep 3(1):47.*

Schmitt-Rodermund E (2004) Pathways to successful entrepreneurship: parenting, personality, early entrepreneurial competence, and interests. J Vocat Behav 65(3):498–518