Abstract

Regeneration of northern conifer forests is commonly performed by reforestation with genetically improved materials obtained from long-term breeding programs focused on productivity and timber quality. Sanitary threats can, however, compromise the realization of the expected genetic gain. Including pest resistance traits in the breeding programs may contribute to a sustainable protection. Here we quantified the variation in different components of resistance of Norway spruce to its main pest, the pine weevil Hylobius abietis. We followed insect damage in two large progeny trials (52 open-pollinated families with 100–200 individuals per family and trial) naturally infested by the pine weevil. Pine weevils damaged between 17 and 48% of the planted seedlings depending on the trial and year, and mortality due to weevil damage was up to 11.4%. The results indicate significant genetic variation in resistance to the pine weevil, and importantly, the variation was highly consistent across trials irrespective of contrasting incidence levels. Individual heritability estimates for the different components of seedling resistance were consistently low, but family heritabilities were moderate (0.53 to 0.81). While forward selections and breeding for higher resistance seem not feasible, backwards selections of the best parent trees emerge as a putative alternative to reduce weevil damage. A positive genetic correlation between early growth potential and probability of being attacked by the weevil was also observed, but the relationship was weak and appeared only in one of the trials. Overall, results presented here open the door to a new attractive way for reducing damage caused by this harmful pest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regeneration of northern conifer forests in Europe and America is increasingly performed by means of reforestation with genetically improved material on areas previously opened by clear-cuts (Nilsson et al. 2010). After decades of intensive selection, testing, and breeding in long-term breeding programs, high-quality genetic materials with superior volume growth and wood properties are now available and massively used for forest regeneration (Lindgren et al. 2008). Sanitary threats can, however, compromise the realization of the expected genetic gain. One of these sanitary threats is the pine weevil Hylobius abietis (L.), which can cause extremely high mortality rates during the first years after planting in recent clear-cuts (Långström and Day 2004). The damage is caused by the adult insects, which feed on the phloem and bark of conifer seedlings, causing pronounced wounds that can girdle the stem and kill the seedling (Day et al. 2004). In order to maintain survival rates at acceptable levels, plant protection measures are commonly mandatory (Nordlander et al. 2011; Örlander and Nilsson 1999; Petersson and Örlander 2003).

As a consequence of increasing concerns regarding the use of insecticides, vast efforts have been dedicated during the last decades to find efficient methods to minimize the impact of pine weevils in conifer plantations (Nordlander et al. 2011). Although no definitive treatment is available, acceptable levels of seedling survival are now achieved by combining silvicultural methods (e.g., soil scarification, retention of shelter trees, delayed plantation) that minimize the pine weevil pressure on the planted seedlings (Nordlander et al. 2011; Örlander and Nilsson 1999; Petersson and Örlander 2003), with direct protection of the seedlings with physical barriers in the form of coatings on the stem (Nordlander et al. 2009; Petersson et al. 2004). These prophylactic measures are, however, relatively expensive to apply. The need for alternative methods to reduce damage by this pest remains high, motivating research initiatives focused on, e.g., the use of chemical elicitors to improve seedling resistance (Fedderwitz et al. 2016; Zas et al. 2014) or biological control of the pine weevil by nematodes (Williams et al. 2013).

An option that has received little attention is improving resistance through selection and breeding (Telford et al. 2015). Conifers harbor a wide array of physical and chemical defenses that deter, impede, and reduce the damage caused by insect herbivores (Franceschi et al. 2005; Mumm and Hilker 2006). These defenses, among which resin-based defenses are the most characteristic, are widely recognized as quantitative traits with concentration-dependent effects on effective resistance (Phillips and Croteau 1999), and typically show large additive genetic variation (Rosner and Hannrup 2004; Sampedro et al. 2010; Westbrook et al. 2015). Plant lineages may also differ in the nutrient content of their tissues (Moreira et al. 2012) and even in the volatile compounds they emit (Blanch et al. 2012), which may affect the attraction, preference, and damage caused by herbivores. As a consequence, resistance to specific insect pests usually shows large within-population genetic variation (Moreira et al. 2013; Mottet et al. 2015; Yanchuk et al. 2008; Zas et al. 2005), and this variation can be exploited in breeding programs for improving tree resistance. Using conventional selection and breeding, for example, has allowed the deployment of Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis [Bong.] Carr) genetic materials resistant to the white pine weevil Pissodes strobi (Peck), contributing to the return of this species as a choice for planting in British Columbia (Alfaro et al. 2013).

Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) is one of the dominant forest tree species in Northern Europe, and also one of the most severely impacted by the pine weevil (Wallertz et al. 2014). Surprisingly, despite the huge effort for improving growth and timber properties that has been done in this species across multiple countries (Jansson et al. 2013), to our best knowledge, no single attempt has been done to explore whether resistance of Norway spruce to the pine weevil is genetically variable and can be enhanced by conventional selection and breeding. Results from breeding programs in Eastern Canada has revealed large genetic variation in Norway spruce in resistance traits against another weevil (the white pine weevil P. strobi), with most of this variation being additive (Mottet et al. 2015). Despite the lack of information on genetic variation in resistance to the pine weevil for northern conifer species, significant additive variation in resistance has been reported in Mediterranean pines of Southern Europe, such as the native Pinus pinaster Aiton (Zas et al. 2005) and the exotic Pinus radiata D. Don (Zas et al. 2008). Since Norway spruce is a species characterized by high genetic diversity and low population differentiation (Jansson et al. 2013), it seems reasonable to expect a significant intraspecific variation in resistance to H. abietis.

An important point is the potential trade-off between insect resistance and other traits of interest. Resistance to herbivores in conifer trees relies mainly on carbon-based compounds that are synthesized and accumulated in every tissue in high concentrations (Franceschi et al. 2005). Producing these defenses requires, thus, large amounts of carbon resources, resulting in potential conflicts with other plant functions such as growth (Sampedro 2014; Villari et al. 2014). Whenever these physiological trade-offs have any genetic basis, improving resistance through selection and breeding could negatively impact growth, and vice versa. Previous results on Mediterranean pine trees reveal that this could be the case with resistance to the pine weevil (Zas et al. 2005, 2008). Genetic correlations between resistance to P. strobi and growth of Norway spruce were, however, either not significant or positive (Mottet et al. 2015). The emergence of these trade-offs seems thus to be context dependent (Sampedro et al. 2011). Defining the extent to which resistance to pine weevil and growth are correlated is crucial to understand if selecting and breeding for improved resistance may reduce achieved genetic gains in growth and timber properties but also to understand if breeding for growth has led to increased susceptibility to this important pest (Zas et al. 2005).

The aim of this paper was to explore whether the current Norway spruce breeding population of southern Sweden harbor enough genetic variation in resistance to the pine weevil to allow for reducing the impact of the pest through selection and breeding. Specifically, we aimed (i) to estimate genetic parameters (heritability, genetic correlations, genotype by environment interaction) of different quantitative components of seedling resistance to the pine weevil (probability of attack, amount of damage, and seedling mortality) and (ii) to explore possible negative genetic correlations between growth and resistance. We explored these questions using data collected in two large open-pollinated progeny trials established on recently clear-cut areas that were naturally infested by the pine weevil. The trials were designed with an unusually large number of individuals per family (up to 200) in order to allow enough weevil damage and to improve the accuracy of the genetic analyses. Spatial analyses of the weevil damage incidence allowed for accounting for any spatial aggregation beyond the experimental design.

Material and methods

Plant material

The seed material for trial 1 was selected from the South Swedish breeding population based on superior vigor, height, and diameter growth in previous field genetic trials. Fifty-two genotypes were selected among parent clones recommended for harsh sites with spring frost problems in south Sweden (seed zone 7) (Karlsson and Rosvall 1993). The selected mother trees were open wind pollinated, and thus, seed lots were half-sib families. The seeding was conducted in March 2012, and to obtain large enough seedlings, they were kept in the greenhouse until the end of September, then moved outside to get hardy for the winter. No insecticide was applied. In November, seedlings were labeled and packed in cardboard boxes following a randomized block design with 200 blocks and one replication per block. The seedlings were stored in − 4 °C during the winter.

For the second trial (trial 2), 24 out of the original 52 half-sib families were selected to include the entire range of variation in susceptibility to damage based on the early results of trial 1. The seeding was done in March 2014. The cultivation was as for trial 1, except that the seedlings were taken out from the greenhouse in late June. Seedlings were labeled and arranged in a randomized block design with 100 blocks and one replication per block.

The size of the planted seedlings differed considerably between the two trials. Seedling height at planting was 22.85 ± 0.76 and 31.60 ± 1.06 cm in trial 1 and trial 2, respectively, with basal stem diameter of 2.65 ± 0.06 and 3.64 ± 0.09 mm (mean ± SE; N = 25 seedlings per family).

Progeny trials

The progeny trials were established in two adjacent clear-cuts (6.8 and 6.1 ha, with 350 m in between) at Älvkarleby, 75 km N of Uppsala, Sweden (see details in Table S1), on a uniform sandy soil, almost flat at 20–22 m a.s.l. The whole area was formerly dominated by Scots pine with some Norway spruce, and was harvested in February 2012 and April 2014 for trials 1 and 2, respectively. Planting of the trials was conducted on 10–14 May 2013 (trial 1) and 27–28 April 2015 (trial 2), that is, approximately 1 year after the harvesting for both trials. According to general knowledge of the life cycle and seasonal activity of the pine weevil (Nordlander et al. 2017), feeding damage in the trials was expected from the time of planting in spring until October the same season and also in spring the following year.

Both trials followed a randomized block design with 200 blocks in trial 1 and 100 blocks in trial 2. Blocks were established along main transects within the clear-cuts (Fig. S1) and were formed by single tree plots, with one seedling per family planted in random order in rows with approximately 0.6 m spacing between seedlings. In trial 1, the 52 seedlings in a block were distributed along four parallel rows with 1.2-m spacing, whereas in trial 2 the 24 seedlings were planted in two parallel rows with 0.6-m spacing. In total, about 10,400 seedlings were established in trial 1 and 2400 in trial 2.

Because pine weevil feeding on seedlings is strongly influenced by soil conditions around the seedlings (e.g., Petersson et al. 2005), we strived to plant the seedlings uniformly in relation to soil preparation within each of the two trials. In trial 1, we aimed for an intermediate level of pine weevil pressure, and therefore seedlings were planted just along the border between mineral soil and humus, created by shallow soil preparation with an excavator. Since the rate of attacks was relatively slow in trial 1, trial 2 was planted directly in the shallow tracks made by the caterpillar treads of an excavator (almost without any exposed mineral soil) to increase weevil pressure.

Assessments

Assessments of damage caused by pine weevil and seedling height were made for all experimental seedlings. In trial 1, weevil damage was assessed in the autumn after one season (year 1) and also in late June the following season (year 2); i.e., at a time when a large proportion of the weevils should have just left the clear-cut during spring migration (Nordlander et al. 2017). Inspection on 20 August and 18 September confirmed that only little additional damage occurred after June (unpublished data). Trial 2 was assessed in the autumn after one season (year 1); the attack rate was then similar as recorded in year 2 in trial 1. Weevil damage was assessed visually by carefully inspecting the seedlings down to the base of the stem. Estimates of debarked area were repeatedly calibrated by comparisons with drawings of accurately measured areas. For the final inventory on year 2 in trial 1, data from the previous inventory was used during the inspection to facilitate estimation of additional damage during the second season. A binary variable—damaged or not by the pine weevil—was also introduced to calculate the “probability of being damaged”. Additionally, we recorded as binary variables whether the weevil wounding completely girdled the stem and whether the spruce seedlings survived or not to the weevil damage. Seedlings dead due to other causes than the pine weevil damage (less than 2% in trial 1 and less than 4% in trial 2) were excluded from the analyses. Seedling total height at the end of the first growing season (year 1) was also measured in the two trials.

Spatial analyses

Analyzing genetic variation in insect resistance upon data collected in a genetic trial naturally infested by the pest requires testing whether the incidence of the insect is homogeneously distributed along the experimental area or, at least, whether it follows spatial patterns that the experimental design is able to account for. If not, the requisite of independence of the observations is violated and the analysis could fail to differentiate true genetic variation from spatial or micro-environmental effects. To discern the spatial pattern of the pine weevil damage incidence within each trial, we used a procedure similar to that described in Zas et al. (2006). Coordinates of each seedling were estimated based on the GPS coordinates of each plot and the relative position of each seedling within each plot. We first computed the semivariograms of the residuals of weevil damage after adjusting for genetic effects (see mixed models described below) to explore for spatial dependence at small scale, i.e., within blocks. Residuals were obtained by means of a one-way ANOVA with the family as the unique fixed factor. Semivariograms represent the variance among positions as a function of the distance separating them (Cressie 1993). Flat semivariograms denote spatial randomness whereas semivariograms in which the semivariance tends to increase with distance indicates spatial dependence of the data. The shape of the semivariogram reflects the spatial structure (Cressie 1993). We also explored the spatial trends at large scales constructing the semivariograms of block means and kriging estimation of the spatial patterns. Variography and kriging were conducted using the SAS system.

Statistical analyses

Growth (seedling height) and damage (debarked area) data from each trial was first analyzed independently by means of a mixed model with blocks as a fixed factor and the open-pollinated family as a random factor. The mixed models were fitted using the MIXED procedure of the SAS system, and variance components were estimated by the REML method. The significance of the family factor was tested by likelihood ratio tests in which we compared the log-likelihood of the models including and excluding this random factor. The differences in two times the log-likelihood of the models including and excluding the random factor are distributed as a one-tailed chi-square with one degree of freedom.

Binary data (probability of being damaged, stem girdling, and mortality caused by the weevil) were analyzed using generalized linear models assuming a binary distribution and a logit link function. Mixed logistic models assume an underlying continuous distribution of phenotypes with a polygenic base that results in two possible observed outcomes (yes/no). Working on the liability scale allows the estimation of genetic parameters for the dichotomous variable and the direct comparison of estimates across traits and experiments (Aparicio et al. 2012). These statistical models were equivalent to the mixed models described above and were fitted with the GLIMMIX procedure of the SAS system.

Individual (h i 2) and family (h f 2) heritabilities were estimated upon the corresponding estimated variance components, assuming families as true half-sibs (i.e., additive variance equal to four times the family variance):

where \( {\sigma}_f^2 \) and \( {\sigma}_e^2 \) are the family and residual variance estimates, respectively, and n is the average number of plants per family in the corresponding trial. In the case of the binary variables, the residual variance was assumed to be 2/3·π = 3.28987 (i.e., the variance on the underlying scale for the logit link).

Joint analyses, combining the data of the 24 common families in the two progeny trials were also carried out, assuming trial and block within trial as fixed factors and family and the family by trial interaction as random factors. Assuming that the weevil incidence in trial 1 during the first year was too low, we combined for these analyses data from trial 2 with cumulative damage at the end of the second growing season in trial 1. A full model with an unstructured family covariance structure (G matrix) was first fitted. In order to explore and interpret the G × E interaction, different reduced models constraining different elements of the family covariance structure were then fitted and compared to the corresponding full model (de la Mata and Zas 2010). Two main sources of interaction were tested: heterogeneity of family variance across trials (i.e., comparing the full model with a reduced model in which a common family variance is assumed for the two trials) and deviations from perfect correlations between trials (i.e., comparing the full model with a reduced model in which the genetic correlation between trials is constrained to be 1). Hypothesis testing regarding the sources of G × E interaction were done by comparing the restricted log-likelihood (RLL) of the constrained and unconstrained model. Under the null hypothesis that the full model is not different from the reduced model, the log-likelihood ratio LLR = −2·(RLLreduced model − RLLfull model) is approximately distributed as a χ 2 with degrees of freedom equal to the differences between the number of covariance parameters of the full and reduced models (Fry 2004).

Best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) were estimated from the single-site analyses for each family and trial, and used for genetic gain estimations based on family selections of different intensities. Genetic gain for a selection of the best j families (ΔG j ) was estimated as

where S j is the estimated selection differential for the best j families (with j varying from 1 to half of the number of families tested in the trial) and μ is the overall mean in that trial.

Genetic correlations among traits were estimated for each trial separately using the Pearson correlations among family BLUPs for each trait and trial.

Results

Weevil damage

In trial 1, 17.7% of the experimental seedlings were wounded by the pine weevils after the first season (year 1 assessment), with an average debarked area in attacked seedlings of 0.79 ± 0.02 cm2. Damage during the second season (year 2 assessment) was higher, 48.0% of the seedlings were wounded, and mean debarked area in attacked seedlings was 0.51 ± 0.01 cm2. Feeding scars caused stem girdling in 4.4 and 8.3% of the experimental seedlings and killed 4.5 and 8.4% of them, in years 1 and 2, respectively. No phenotypic relationship was observed between weevil damage during the first and second years. In trial 2, where damage assessment was made only for the first growing season, 48.0% of the experimental seedlings were wounded by the weevils, and the average debarked area in attacked seedlings was 1.16 ± 0.04 cm2. Weevil damage caused stem girdling in 10.3% of the plants, and mortality due to weevil damage was 11.4%.

Spatial structure

Weevil incidence was not randomly distributed within the two field trials as revealed by the semivariograms for the block means of the debarked area (Fig. S1). In both cases, the semivariance clearly diminished at short distances, and the spherical model fitted well to the observed semivariogram (r 2 = 0.87, p < 0.001 and r 2 = 0.76, p < 0.001 for trial 1 and trial 2, respectively) (Fig. S1). Accordingly, important deviations from spatial randomness were obtained for the other traits related to weevil damage (Table S2). The intensity of the spatial dependence ranged between 38.6 and 76.2% of the overall variation depending on the considered trait. Despite the strong spatial structure of the weevil damage incidence, the scale of the spatial dependence (which varied between 38.9 and 85.7 m, Table S2) was by far greater than the size of the blocks of the experimental designs (around 4 × 8 m in trial 1 and 1 × 7 m in trial 2), and thus, the impact of the spatial structure on the statistical analyses was minimal. This was confirmed by the flat semivariogram at short distances for the residuals of the debarked area after adjusting for family effects (Fig. 1).

Small-scale (within blocks, 0–15 m) spatial variation of weevil damage incidence in trial 1. The figure shows the empirical semivariogram of the residuals of weevil damage (debarked area at year 1) after adjusting for genetic and block effects using mixed models. The flat semivariogram denotes spatial randomness at the scale of the size of the blocks in the experimental design (8 m long), that is, spatial homogeneity within blocks

On the other hand, the spatial dependence of seedling height was only relevant in trial 1 (Table S2). Spatial dependence for seedling height in this trial was similar in intensity but notably shorter in scale than that for weevil incidence (Table S2).

Genetic variation

Norway spruce families strongly differed in height growth with consistently large individual and family heritability estimates in both trials (Table 1).

The families also varied in their susceptibility to the pine weevil in the two trials, but the significance of the family variance for the different components of seedling resistance largely varied depending on the trial (Table 1). In trial 1, the probability of being damaged by the weevil varied significantly among spruce families both 1 and 2 years after planting, but there were not significant differences among spruce families in the amount of damage (Table 1). Those differences were translated into significant variation among spruce families in their ability to survive weevil damage (Table 1). Family mortality due to pine weevil feeding after two growing periods varied between 3 and 20%. On the contrary, in trial 2, the amount of damage significantly varied among spruce families, but the family variance for the probability of being damaged by the weevil was only marginally significantly different from zero, as was that for survival to weevil damage (Table 1).

Individual heritability estimates were consistently low for all components of weevil resistance and all trial-year combinations (Table 1). Family heritability estimates were, however, notably higher, especially for the case of survival to the pine weevil damage, which varied from 0.53 to 0.81 depending on the trial and year (Table 1).

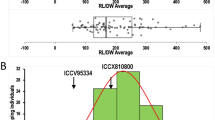

Genotype × environment interaction

The genotype × environment interaction (G × E) was highly significant for all the assessed traits except for survival to weevil damage (Table 2). The sources of the G × E interaction strongly differed, however, for growth and weevil resistance traits. While in the case of seedling height the main source of the interaction was the departure from perfect correlation (reflecting a crossover interaction with strong family rank changes between the two trials), for the different components of weevil resistance the main source of the interaction was the heterogeneity of family variances between the trials (Table 2). No significant deviations from perfect correlations between the trials were detected for any trait related to weevil resistance (Table 2), suggesting a high correspondence of family ranks between trials for all components of resistance to the pine weevils. In contrast, we found no significant family correlation in height growth across trials (Fig. 2).

Genetic gain

Could the relatively large family heritability estimates make it possible to reduce the impact of weevil damage by planting less susceptible families on more risky sites? Figure 3 shows the estimated genetic gains for debarked area and for mortality caused by the pine weevil for different intensities of family selection in the two trials. Accordingly with the low family heritability estimates, the genetic gains for debarked area were very low in trial 1 and only moderate in trial 2. Selecting the 50% of the families with the lowest weevil damage in trial 2 resulted in an expected reduction of the average weevil damage of about 8% (Fig. 3). The genetic gain for survival was, however, notably higher and consistent for the two test trials, reaching values of up to nearly a 50% reduction of seedling mortality for the highest selection intensities (Fig. 3).

Genetic correlation among traits

A positive genetic correlation between seedling growth and damage by the pine weevil was found in trial 1, where a low but significant Pearson correlation was observed between the family best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) for seedling height and those for the probability of being damaged by the weevil during the two first growing seasons (Table 3). No relevant significant correlation was observed for any other traits, nor in the other trial (Table 3).

Discussion

Breeding for resistance is a powerful tool for fighting against native biotic threats, a main and speedily progressing problem associated to global change (Telford et al. 2015). Here, we explored the potential for breeding Norway spruce for resistance against the most important pest for the regeneration of managed conifer forests in Northern Europe, the pine weevil H. abietis (Långström and Day 2004). To this end, we explored the genetic variation in the susceptibility to the insect among open pollinated families selected from the Norway spruce breeding population of southern Sweden, analyzing the incidence of the insect in two progeny trials naturally infested by the pest. The results indicate significant genetic variation in resistance to the pine weevil, and importantly, the variation was highly consistent across trials irrespective of contrasting weevil incidence levels. Overall, the results suggest that backward selections of the best parent trees emerge as a putative alternative to reduce weevil damage. We also found evidence of a positive genetic correlation between early growth potential and probability of being attacked by the weevil in one of the two trials.

Significant genetic variation in different components of resistance

The results indicated significant genetic variation among the tested open-pollinated Norway spruce families in resistance to the pine weevil in the two trials, although different components of weevil resistance were responsible of this variation in the two trials. In trial 1, where the overall weevil damage incidence was relatively low, genetic variation was observed for the probability of being damaged but not for the amount of damage that seedlings suffered. The probability of being damaged (i.e., a binary variable reflecting whether the seedling is attacked or not by the weevils) can be interpreted as the result of the attractiveness of the seedlings to the insects (Nordlander 1991). When the weevil pressure is low, weevils seem to choose to attack specific spruce variants, but the weevil pressure may have been too low to allow detection of differences in debarked area among families. Genetic variation in key volatile terpenes or other seedling emitted odors involved in pine weevil attraction, such as α-pinene (Björklund et al. 2005; Nordlander et al. 1986) which is typically large in temperate and boreal conifers (e.g., Sampedro et al. 2010), might explain this variation in the probability of being damaged (Kennedy et al. 2006; Tomlin et al. 1997). On the contrary, when weevil pressure was high, such as in trial 2, the amount of debarked area differed significantly among spruce families, while variation for the probability of being damaged was notably lower. These results suggest that at high weevil pressures there is low opportunity for weevils to initially choose the best hosts, but the variation in seedling resistance traits is finally reflected in variation in the amount of damage that the weevils inflicted. Genetic variation in the debarked area may be related to genetic variation in chemical (e.g., terpene and phenolic content and profile in the bark and cortex) and/or physical defenses (e.g., bark thickness and hardness and cortex resin canals) against this herbivore, which are known to show large within-population genetic variation in different conifer species (Moreira et al. 2013; Moreira et al. 2015), including Norway spruce (Axelsson et al. 2015; Danielsson et al. 2011; Rosner and Hannrup 2004).

The relative relevance of the different components of weevil resistance (i.e., attractiveness vs. obstacles for weevil feeding) might have important consequences for the efficiency and durability of improving resistance through breeding (Namkoong 1991). If pine weevil preferences predominate, resistant genetic variants may be attacked when planted alone without more attractive neighboring seedlings (Barbosa et al. 2009). However, as the pine weevil is a polyphagous herbivore that has many alternative food sources—such as roots and branches of mature trees (Örlander et al. 2000; Wallertz et al. 2006)—it is unlikely that the pressure on less attractive seedlings would increase significantly if they were planted without more attractive neighboring seedlings. If, on the other hand, resistance is mainly due to chemical or physical resistance traits, an increased pressure on weevil populations to evolve countermeasures can emerge by planting just resistant material (Brown 2015). Again, the polyphagous behavior of the pine weevil can dilute this undesired effect.

Why was the genetic variation in resistance not larger?

The observed variation in resistance to the pine weevil in Norway spruce was significant but lower than for pine species against the pine weevil (Zas et al. 2008; Zas et al. 2005) and for Norway spruce against other weevil species (Mottet et al. 2015). Particularly relevant is the variation in resistance of Norway spruce to the white pine weevil P. strobi, a serious pest native to North America, where it causes important damage to the introduced Norway spruce. Evaluation of genetic trials in Eastern Canada has revealed large additive variation in Norway spruce to this insect (Mottet et al. 2015). Norway spruce is exotic in Canada and has not co-lived naturally with the white pine weevil, so the observed variation is likely a by-product of variation in resistance traits to other native pests with which the Norway spruce have co-evolved. Therefore, we expected larger intraspecific variation also to native weevils such as H. abietis than we recorded.

Several non-exclusive factors can explain the relatively low genetic variation in resistance. First, breeding for productivity could have truncated the remaining variability in other functional traits such as resistance to pest and pathogens (Androsiuk et al. 2012). Previous studies in pine trees have shown that even a single selection event on productivity traits can introduce measurable changes in other life functions (Santos-del-Blanco et al. 2015). We do not know if this could be the case for our Norway spruce population, but there is ample evidence that this breeding populations retain high neutral genetic variation that covers most of the existing natural variation (Androsiuk et al. 2012). Moreover, Norway spruce breeding populations are in general known to harbor substantial genetic variation to different pests and pathogens (Axelsson et al. 2015; Karlsson and Swedjemark 2006; Skrøppa et al. 2015; Swedjemark and Karlsson 2014) so reduced diversity due to recurrent unidirectional selection and breeding seems unlikely to be the reason for the low variability in resistance to pine weevil.

Secondly, the low variation in resistance to the pine weevil could be related to the particular breeding population. Variability in any trait can drastically vary across different populations depending on their genetic background (Conner and Hartl 2004). Moreover, variation in resistance could be restricted to single spots or populations. For instance, genetic variation in Sitka spruce resistance against the white pine weevil in British Columbia has been found in just one single provenance, with the remaining populations being uniformly highly susceptible (Alfaro et al. 2013). Therefore, the relatively low (52) number of tested families may have been too low to capture the full range of genetic variation. Studies on populations from natural stands and/or in other breeding materials with different genetic backgrounds would be necessary to see if this is the case.

Third, the levels of damage in the trials were probably too low for optimal detection of genetic variation, as indicated by the fact that genetic variation in the debarked area was only observed in trial 2 where the damage was greater. Debarked area observed in our study was slightly lower than those commonly occurring in recent clear-cuts in Southern Sweden (Örlander and Nilsson 1999). Further studies should confirm whether variation in resistance to the pine weevil may be increasingly expressed when the pine weevil pressure is greater.

No genotype by environment interaction

Despite the low genetic variation, the high correspondence between the results of the two trials facilitates selection or breeding initiatives to improve resistance. Low to moderate G × E interaction was also observed for growth traits in Norway spruce in southern Sweden (Berlin et al. 2015). Contrastingly, results presented here indicated reduced genetic correlation across trials for growth traits. Although the two trials were located in virtually the same site, several environmental factors differed considerably between the two trials. Firstly, the seedlings of trial 2 were much taller when planted (in average 32 vs. 23 cm), and therefore had a less suitable root/shoot ratio. Secondly, the two trials were planted in different years (2013 and 2015) with quite different weather conditions; for instance, early spring (until April) was unusually cool in 2013 but thereafter it was warmer from May to July in 2013 than in 2015. Additionally, seedling growth rate at so early stages may be confounded or at least highly influenced by both nursery conditions and maternal seed effects (Herman and Sultan 2011). The extremely high heritability estimates observed for height growth suggests that this may be the case. It could be, thus, expected that the relevance of the G × E interaction for height growth is reduced as trees get older.

Nevertheless, the extremely low G × E interaction for the traits related to weevil resistance, at least regarding cross-over interactions across trials, is important and indicates that the relative differences among families in their resistance to the pine weevil are independent of the abiotic and biotic environment. No relevant family rank changes are thus expected in relation to weevil resistance when planted under the common high pine weevil pressures. On the other hand, differences in family variances across sites suggest that the higher the weevil pressure, the higher the relative relevance of the family variance component.

In previous related studies analyzing whether the genetic variation in resistance to pests depends on the environmental conditions, the genotype by environment interaction also appeared to be of low relevance. For example, Mottet et al. (2015) found high type B genetic correlations among test sites in resistance of Norway spruce to P. strobi. Furthermore, genetic resistance of Maritime pine and Radiata pine families to the pine weevil varied little among different fertilization treatments irrespective of their high incidence in both seedling growth and weevil damage (Zas et al. 2008; Zas et al. 2005).

Positive association between growth potential and susceptibility

A low but positive genetic correlation between growth and susceptibility was found in trial 1, where those families showing the greater early growth (height after 1 growing season) were those sustaining the higher probability of attack. Such a genetic association could be interpreted as evidence of undesired side effects of breeding for lineages with increased productivity. A positive genetic correlation between early growth potential and field mortality due to the pine weevil has been reported for the breeding population of other conifer species (Zas et al. 2008; Zas et al. 2005). Plant resources are limited and cannot be allocated simultaneously to several functions, and these physiological conflicts may emerge as trade-offs among alternative life functions, a common pattern in nature that may impede breeding for both functions simultaneously (Agrawal et al. 2010). However, probability of being attacked should be interpreted with caution as a proxy of overall resistance and mortality, whereas early growth as evaluated here may not be a good proxy of genetic growth potential across the rotation age. Probability of attack depends on multiple factors, including plant characteristics affecting the complex process of target selection by the weevils (Björklund et al. 2005), and insect population levels. Initial attraction may be driven directly by plant size and diameter, that is, by resource availability, but also by appearance (e.g., by volatile bouquet), and food quality (i.e., nutrient content and seedling defensive phenotype). On the other hand, intensity of damage in attacked seedlings would depend on the ability of plants for mounting quick and effective induced defenses, and survival would be affected by traits related with tolerance, the ability of suffering a level of damage without effects on fitness. All these components of resistance have been recognized as genetically variable traits in conifers, and more importantly likely showing co-variation among them (Blanch et al. 2012; Moreira et al. 2015; Sampedro et al. 2010; Sampedro et al. 2011). For example, the white pine weevil is more attracted to vigorous trees of interior spruce, but at the same time, faster growing families have higher levels of genetic resistance (King et al. 1997).

On the other hand, growth assessment at very early ages, such is the case here, may be not a good predictor of later growth at mature ages. Age-age genetic correlations with these early measurements are likely low, as growth assessments soon after planting may be highly affected by many confounding factors, including post-planting stress (e.g., Climent et al. 2008) and maternal effects (e.g., Bischoff and Mueller-Schaerer 2010). Additionally, compromises between growth and defense can drastically vary across tree lifespan (de la Mata et al. 2017). The observed growth-resistance relationship should thus be interpreted with care, and further research is required for clarifying whether early resistance to the pine weevil is related or not with mature genetic growth rates and whether intensive breeding for productivity could finally lead to an overall decrease in resistance against this harmful pest.

Implications for breeding

Judging from the low individual heritability estimates, breeding for higher pine weevil resistance in this population seems not feasible. However, an interesting and easy to apply practice that emerges from the results of this paper is to remove the most susceptible families from the spruce breeding program or to use the families with a higher resistance where there is need to enhance the protective countermeasures against pine weevil damage. Both the moderate family heritability estimates and the extremely low genotype by environment interaction resulted in consistent and considerable genetic gains upon this selection strategy. Moreover, since the pine weevil is such a major problem, relatively minor differences in resistance could be important (Wainhouse 2004), not the least in combination with other damage-suppressing methods (Nordlander et al. 2011). Furthermore, segregating from the current deployment population, one subset of families with higher resistance to the pine weevil is straightforward to apply without any important economic and logistic investments. Based on the results of this study, genetic gains upon this strategy can be moderate, easily reaching 10–20% of reduction in mortality due to weevil damage. However, as discussed before, genetic gain can likely be much larger under higher weevil pressures and in other spruce populations.

Conclusions

Results from this study show that Norway spruce shows small but significant genetic variation in resistance to the pine weevil, a major pest for this species. Selecting the most resistant families within Norway spruce breeding populations emerge as an operative, easy, and efficient measure to enhance current measures to reduce weevil damage to acceptable levels. Further research should explore whether these results are confirmed among different Norway spruce populations, look for additional sources of resistance in other spruce provenances, and address how abiotic and biotic environmental conditions influence the effective resistance, including evaluations under high weevil pressure.

References

Agrawal AA, Conner JK, Rasmann S (2010) Tradeoffs and negative correlations in evolutionary ecology. In: Bell MA, Eanes WF, Futuyma DJ, Levinton JS (eds) Evolution after Darwin: the first 150 years. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, pp 242–268

Alfaro RI, King JN, vanAkker L (2013) Delivering Sitka spruce with resistance against white pine weevil in British Columbia, Canada. For Chron 89:235–245

Androsiuk P, Shimono A, Westin J, Lindgren D, Fries A, Wang XR (2012) Genetic status of Norway spruce (Picea abies) breeding populations for northern Sweden. Silvae Genetica 62:127–136

Aparicio A, Zuki S, Pastorino M, Martinez-Meier A, Gallo L (2012) Heritable variation in the survival of seedlings from Patagonian cypress marginal xeric populations coping with drought and extreme cold. Tree Genet Genomes 8:801–810

Axelsson EP, Iason GR, Julkunen-Tiitto R, Witham TG (2015) Host genetics and environment drive divergent responses of two resource sharing gall-formers on Norway spruce: a common garden analysis. PLoS One 10:e0142257

Barbosa P, Hines J, Kaplan I, Martinson H, Szczepaniec A, Szendrei Z (2009) Associational resistance and associational susceptibility: having right or wrong neighbors. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:1–20

Berlin M, Jansson G, Högberg K-A (2015) Genotype by environment interactions in the southern Sweden breeding population of Picea abies using new climatic indices. Scand J For Res 30:112–121

Bischoff A, Mueller-Schaerer H (2010) Testing population differentiation in plant species—how important are environmental maternal effects. Oikos 119:445–454

Björklund N, Nordlander G, Bylund H (2005) Olfactory and visual stimuli used in orientation to conifer seedlings by the pine weevil, Hylobius abietis. Physiol Entomol 30:225–231

Blanch JS, Sampedro L, Llusia J, Moreira X, Zas R, Peñuelas J (2012) Effects of phosphorus availability and genetic variation of leaf terpene contents and emission rates in Pinus pinaster seedlings susceptible and resistant to the pine weevil Hylobius abietis. Plant Biol 14:66–72

Brown JKL (2015) Durable resistance of crops to disease: a Darwinian perspective. Annu Rev Phytopathol 53:513–539

Climent J, Alonso J, Gil L (2008) Root restriction hindered early allometric differentiation between seedlings of two provenances of Canary Island Pine. Silvae Genetica 57:187–193

Conner JK, Hartl DL (2004) A primer of ecological genetics. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland

Cressie NAC (1993) Statistics for spatial data. Wiley, New York

Danielsson M et al (2011) Chemical and transcriptional responses of Norway spruce genotypes with different susceptibility to Heterobasidion spp. infection. BMC Plant Biol 11:e154

Day KR, Nordlander G, Kenis M, Halldórson G (2004) General biology and life cycles of bark weevils. In: Lieutier F, Day KR, Battisti A, Grégoire J-C, Evans HF (eds) Bark and wood boring insects in living trees in Europe, a synthesis. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 331–349

Fedderwitz F, Nordlander G, Ninkovic V, Björklund N (2016) Effects of jasmonate-induced resistance in conifer plants on the feeding behaviour of a bark-chewing insect, Hylobius abietis. J Pest Sci 89:97–105

Franceschi VR, Krokene P, Christiansen E, Krekling T (2005) Anatomical and chemical defenses of conifer bark against bark beetles and other pests. New Phytol 167:353–376

Fry JD (2004) Estimation of genetic variances and covariances by restricted maximum likelihood using PROC MIXED. In: Saxton AM (ed) Genetic analysis of complex traits using SAS. SAS Institute, Cary, pp 11–34

Herman JJ, Sultan SE (2011) Adaptive transgenerational plasticity in plants: case studies, mechanisms, and implications for natural populations. Front Plant Sci 2:1–10

Jansson G, Danusevičius D, Grotehusman H, Kowalczyk J, Krajmerova D, Skrøppa T, Wolf H (2013) Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.) In: Pâques LE (ed) Forest tree breeding in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 123–176

Karlsson B, Rosvall O (1993) Breeding programmes in Sweden. Norway spruce. In: Lee SJ (ed) Progeny testing and breeding strategies, Proceedings of the Nordic group of tree breeding, October 1993. Forestry Commission, Edinburgh. Corrected reprint in: SkogForsk, Arbetsrapport nr 302, Uppsala (1995), pp 1-25

Karlsson B, Swedjemark G (2006) Genotypic varaition in natural infection frequency of Heterobasidion spp. in a Picea abies clone trial in southern Sweden. Scand J For Res 21:108–114

Kennedy S, Cameron A, Thoss V, Wilson M (2006) Role of monoterpenes in Hylobius abietis damage levels between cuttings and seedlings of Picea sitchensis. Scand J For Res 21:340–344

King JN, Yanchuk AD, Kiss GK, Alfaro RI (1997) Genetic and phenotypic relationships between weevil (Pissodes strobi) resistance and height growth in spruce populations of British Columbia. Can J For Res 27:732–739

Långström B, Day KR (2004) Damage control and management of weevil pests, especially Hylobius abietis. In: Lieutier F, Day KR, Battisti A, Gregoire JC, Evans HF (eds) Bark and wood boring insects in living trees in Europe, a synthesis. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 415–444

Lindgren D, Karlsson B, Andersson B, Perscher F (2008) Swedish seed orchards for Scots pine and Norway Spruce. Paper presented at the Seed Orchard Conference, Umeå,

de la Mata R, Zas R (2010) Transferring Atlantic maritime pine improved material to a region with marked Mediterranean influence in inland NW Spain: a likelihood-base approach on spatially adjusted field data. Eur J For Res 129:645–658

de la Mata R, Hood S, Sala A (2017) Insect outbreak shifts the direction of selection from fast to slow growth rates in the long-lived conifer Pinus ponderosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114:7391–7396

Moreira X, Zas R, Sampedro L (2012) Genetic variation and phenotypic plasticity of nutrient re-allocation and increased fine root production as putative tolerance mechanisms inducible by methyl jasmonate in pine trees. J Ecol 100:810–820

Moreira X, Zas R, Sampedro L (2013) Additive genetic variation in resistance traits of an exotic pine species: little evidence for constraints on evolution of resistance against native herbivores. Heredity 110:449–456

Moreira X, Zas R, Solla A, Sampedro L (2015) Differentiation of persistent anatomical defensive structures is costly and determined by nutrient availability and genetic growth-defence constraints. Tree Physiol 35:112–123

Mottet M-J, DeBlois J, Perron M (2015) High genetic variation and moderate to high values for genetic parameters of Picea abies resistance to Pissodes strobi. Tree Genet Genome 11:58

Mumm R, Hilker M (2006) Direct and indirect chemical defence of pine against folivorous insects. Trends Plant Sci 11:351–358

Namkoong G (1991) Maintaining genetic diversity in breeding for resistance in forest trees. Annu Rev Phytopathol 29:325–342

Nilsson U, Luoranen J, Kolström T, Örlander G, Puttonen P (2010) Reforestation with planting in northern Europe. Scand J For Res 25:283–294

Nordlander G (1991) Host finding in the pine weevil Hylobius abietis: effects of conifer volatiles and added limonene. Entomol Exp Appl 59:229–237

Nordlander G, Eidmann HH, Jacobsson U, Nordenhem H, Sjodin K (1986) Orientation of the pine weevil Hylobius abietis to underground sources of host volatiles. Entomol Exp Appl 41:91–100

Nordlander G, Nordenhem H, Hellqvist C (2009) A flexible sand coating (Conniflex) for the protection of conifer seedlings against damage by the pine weevil Hylobius abietis. Agric For Entomol 11:91–100

Nordlander G, Hellqvist C, Johansson K, Nordenhem H (2011) Regeneration of European boreal forests: effectiveness of measures against seedling mortality caused by the pine weevil Hylobius abietis. For Ecol Manag 262:2354–2363

Nordlander G, Hellqvist C, Hjelm K (2017) Replanting conifer seedlings after pine weevil emigration in spring decreases feeding damage and seedling mortality. Scand J For Res 32:60–67

Örlander G, Nilsson U (1999) Effect of reforestation methods on pine weevil (Hylobius abietis) damage and seedling survival. Scand J For Res 14:341–354

Örlander G, Nordlander G, Wallertz K, Nordenhem H (2000) Feeding in the crowns of Scots pine trees by the pine weevil Hylobius abietis. Scand J For Res 15:194–201

Petersson M, Örlander G (2003) Effectiveness of combinations of shelterwood, scarification, and feeding barriers to reduce pine weevil damage. Can J For Res 33:64–73

Petersson M, Örlander G, Nilsson U (2004) Feeding barriers to reduce damage by pine weevil (Hylobius abietis). Scand J For Res 19:48–59

Petersson M, Örlander G, Nordlander G (2005) Soil features affecting damage to conifer seedlings by the pine weevil Hylobius abietis. Forestry 78:83–92

Phillips MA, Croteau RB (1999) Resin-based defenses in conifers. Trends Plant Sci 4:184–190

Rosner S, Hannrup B (2004) Resin canal traits relevant for constitutive resistance of Norway spruce against bark beetles: environmental and genetic variability. For Ecol Manag 200:77–87

Sampedro L (2014) Physiological trade-offs in the complexity of pine tree defensive chemistry. Tree Physiol 23:191–197

Sampedro L, Moreira X, Llusia J, Peñuelas J, Zas R (2010) Genetics, phosphorus availability, and herbivore-derived induction as sources of phenotypic variation of leaf volatile terpenes in a pine species. J Exp Bot 61:4437–4447

Sampedro L, Moreira X, Zas R (2011) Costs of constitutive and herbivore-induced chemical defences in pine trees emerge only under low nutrient availability. J Ecol 99:818–827

Santos-del-Blanco L, Alia R, Gonzalez-Martinez SC, Sampedro L, Lario F, Climent J (2015) Correlated genetic effects on reproduction define a domestication syndrome in a forest tree. Evol Appl 8:403–410

Skrøppa T, Solheim H, Hietala A (2015) Variation in phloem resistance of Norway spruce clones and families to Heterobasidion parviporum and Ceratocystis polonica and its relationship to phenology and growth traits. Scand J For Res 30:103–111

Swedjemark G, Karlsson B (2014) Genotypic variation in susceptibility following artificial Heterobasidium annosum inoculation of Picea abies clones in a 17-year-ld field test. Scand J For Res 19:103–111

Telford A, Cavers S, Ennos RA, Cottrell JE (2015) Can we protect forests by harnessing variation in resistance to pest and pathogens? Forestry 88:3–12

Tomlin ES, Borden JH, Pierce HD (1997) Relationship between volatile foliar terpenes and resistance of Sitka spruce to the white pine weevil. For Sci 43:501–508

Villari C, Faccoli M, Battisti A, Bonello P, Marini L (2014) Testing phenotypic trade-offs in the chemical defence strategy of Scots pine under growth-limiting field conditions. Tree Physiol 34:919–930

Wainhouse D (2004) Hylobius abietis-host utilisation and resistance. In: Lieutier F, Day KR, Battisti A, Gregoire JC, Evans HF (eds) Bark and wood boring insects in living trees in Europe, a synthesis. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 365–379

Wallertz K, Nordlander G, Örlander G (2006) Feeding on roots in the humus layer by adult pine weevil, Hylobius abietis. Agric For Entomol 8:273–279

Wallertz K, Nordenhem H, Nordlander G (2014) Damage by the pine weevil Hylobius abietis to seedlings of two native and five introduced tree species in Sweden. Silva Fennica 48:1–14

Westbrook JW et al (2015) Discovering candidate genes that regulate resin canal number in Pinus taeda stems by integrating genetic analysis across environments, ages, and populations. New Phytol 205:627–641

Williams CD, Dillon AB, Harvey CD, Hennessy R, McNamara L, Griffin CT (2013) Control of a major pest of forestry, Hylobius abietis, with entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi using eradicant and prophylactic strategies. For Ecol Manag 305:212–222

Yanchuk AD, Murphy JC, Wallin KF (2008) Evaluation of genetic variation of attack and resistance in lodgepole pine in the early stages of a mountain pine beetle outbreak. Tree Genet Genomes 4:171–180

Zas R, Sampedro L, Prada E, Fernández-López J (2005) Genetic variation of Pinus pinaster Ait. seedlings in susceptibility to Hylobius abietis L. Ann For Sci 62:681–688

Zas R, Sampedro L, Prada E, Lombardero MJ, Fernández-López J (2006) Fertilization increases Hylobius abietis L. damage in Pinus pinaster Ait. Seedlings. For Ecol Manag 222:137–144

Zas R, Sampedro L, Moreira X, Martíns P (2008) Effect of fertilization and genetic variation on susceptibility of Pinus radiata seedlings to Hylobius abietis damage. Can J For Res 38:63–72

Zas R, Björklund N, Nordlander G, Cendán C, Hellqvist C, Sampedro L (2014) Exploiting jasmonate-induced responses for field protection of conifer seedlings against a major forest pest, Hylobius abietis. For Ecol Manag 313:212–223

Acknowledgements

Field sites were kindly provided by Bergvik Skog AB. Authors thank Henrik Nordenhem and Petter Öhrn for help with the field work and Xoaquín Moreira and two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on early drafts of the manuscript.

Funding Information

This research was part of the Parasite Resistant Tree Project funded by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Grant RBb08-0003, to GN and SJ. LS and RZ were supported by the Grant FUTURPIN AGL2015-68274-C03-02R funded by MINECO/FEDER and by the GAIN-Xunta de Galicia Grant IN607A2016/013.

Data archiving statement

Open pollinated families belong to the breeding program of Skogforsk, Sweden. Phenotype data are available in the DIGITAL. CSIC repository, http://hdl.handle.net/10261/155457.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RZ: Analyzed the data, prepared and discussed the results, and led the writing.

NB: Planned the study, conducted field work, discussed the results, and contributed to the writing.

LS: Discussed the results and contributed to the writing.

CH: Led the practical field work and handled and compiled the data.

BK: Selected and provided the genetic material, planned the study, discussed the results, and contributed to the writing.

SJ: Planned the study, provided the funding, and contributed to the writing.

GN: Planned and headed the study, provided the funding, participated in and supervised field work, discussed the results, and contributed to the writing.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by F. Isik

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Figure S1

(DOCX 282 kb).

Supplementary Table S1

(DOCX 28 kb).

Supplementary Table S2

(DOCX 29 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zas, R., Björklund, N., Sampedro, L. et al. Genetic variation in resistance of Norway spruce seedlings to damage by the pine weevil Hylobius abietis . Tree Genetics & Genomes 13, 111 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-017-1193-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-017-1193-1