Abstract

Objectives

To systematically review the effect of social identity and social contexts on the association between procedural justice and legitimacy in policing.

Methods

A meta-analysis synthesising data from 123 studies (N = 200,966) addressing the relationship between procedural justice and legitimacy in policing. Random effects univariate and two-stage structural equation modelling meta-analyses were performed.

Results

Both procedural justice and social identity are found to be significantly correlated with police legitimacy. Moreover, social identity significantly mediates, but does not moderate, the association between procedural justice and legitimacy. People of younger age and from more developed countries tend to correlate procedural justice stronger with police legitimacy.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that social identity is an important antecedent of legitimacy and a critical factor in the dynamics of procedural fairness in policing. It also shows that the extent to which procedural justice and legitimacy are correlated varies across social groups and contexts. The theoretical implications of our findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Procedural justice theory (PJT) has become a dominant paradigm in contemporary police research. Among other things, compared to the classic crime control model of deterrence, enhancing legitimacy via procedural justice is argued to be more cost-effective and sustainable in terms of encouraging law-abiding behaviours, as it relies on an internalised sense of obligation among those being policed (Tyler, 1990). The theory proposes that individuals are more likely to perceive authorities as legitimate and trustworthy when they feel they are treated in a fair and respectful manner by those authorities. Normative compliance is thus promoted by procedurally fair policing, as the public tends to be more cooperative and compliant with laws when they have strong legitimacy beliefs (Tyler, 2001).

Another central argument in PJT is that procedurally fair actions by authorities send important identity-related signals to citizens and communicate shared values and norms (Bradford, 2016; Schaap & Saarikkomäki, 2022; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003a; Tyler & Blader, 2003). A sense of shared values and social similarity, in turn, promotes legitimacy. An understanding of the psychology of social identity is therefore vital if we are to properly elucidate the relationship between perceptions and experiences of procedural (in)justice and police legitimacy (Bradford, 2014; Bradford et al., 2015; Murphy et al., 2022). Yet, despite a recently increasing body of procedural justice research focussing on social identity, within policing contexts at least, the role of social identity processes in procedural justice theory remains under-specified. To address this lacuna, and properly position social identity within theories of police legitimacy, this review tests three social identity-based models of procedural justice, and three constructs of social identity (which are described below), as well as the role of contextual factors in how individuals relate procedural justice and legitimacy in the context of policing.

Procedural justice theory in policing

PJT is premised on a collection of empirical and theoretical studies focussing on understanding how process fairness shapes perceptions of authorities. While its origins can be traced back to early work by Thibaut and Walker (1975) on procedural justice effects in the perceived fairness of decision-making in criminal trials, PJT has since been studied in a wide variety of social contexts (Blader & Tyler, 2015; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014), such as workplace (e.g. Feldman & Tyler, 2012; Hegtvedt et al., 2022), family (e.g. Brubacher et al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2018), and school (e.g. Brasof & Peterson, 2018). While research on procedural justice and legitimacy in work organisations and court procedures has received strong support, these ideas have perhaps particularly been applied to policing (Tyler, 2017).

In criminal justice research, procedural justice is the perception that legal institutions, such as the police and courts, are fair and just during the process of law enforcement (Tyler, 1990). Advocacy for a procedural justice approach in the criminal justice system has been strongly influenced by Tyler’s (1990) seminal work on procedural justice and public compliance. Building upon his own work, Tyler developed a model of process-based regulation which illustrated the psychological path from procedural justice perceptions to long-term acceptance of and cooperation with authorities (Tyler, 2003). The model suggests that the quality of decision-making and interpersonal treatment which the public experiences in their encounters with authorities are the two key antecedents of their assessments of processes and procedures (Tyler & Blader, 2000). Assessments of the quality of decision-making focus upon authorities’ neutrality and lack of bias in making their judgements and decisions during encounters with those they govern. People prioritise the idea that authorities should rely on objective information and not personal biases and prejudices. Moreover, when authorities make decisions based consistently on rules and regulations and provide opportunities for people to present their evidence and explanation, the process of decision-making is more likely to be perceived as being fair. Assessments of the quality of treatment address ‘interactional’ experiences of the public in their encounters with authorities. It is proposed that people want to be treated with respect and dignity, as this signals the authorities’ recognition of their status and value in their social group (Tyler, 2003).

While this model can, as noted, be applied to many social and institutional relationships marked by power imbalances, our focus here is on police-citizen relations. According to PJT, during police encounters, people tend to believe that officers should explain and justify their actions and treat people with respect and dignity. A large empirical literature suggests that when people perceive a good quality of decision-making and interpersonal treatment in their encounters with the police, they are more likely to perceive them as legitimate and are thus more willing to cooperate and comply with their directives (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003a). Although this process-based regulation model maps out how police procedural fairness can ultimately lead to cooperative behavioural outcomes, our interest in this paper is the link between procedural justice perceptions and legitimacy judgements.

In a recent review on the state of legitimacy scholarship, Hamm et al. (2022) proposed a concentric diagram to capture the five fundamental theoretical propositions of legitimacy from the existing literature. At the core of the diagram is the ‘dialogue of legitimacy’, proposed by Bottoms and Tankebe (2012), in which legitimacy is positioned ‘as always dialogic and relational in character’ (p.129). On this account, police legitimacy is not a given but is something that emerges from active ongoing interactional processes through which the police, as power holders, make claims on their right to power, and those claims are responded to by the policed, usually as subordinates within that relationship (Jackson & Bradford, 2022). Hamm and colleagues’ proposition is premised on a specific reading of the account of legitimacy offered by procedural justice theory, which stresses the interactional and relational dynamics between police and people that underpin legitimacy. In other words, each interaction between the police and the public takes place within a negotiated power relationship that can either be accepted or resisted by citizens.

Within the procedural justice literature, there is a broad consensus that legitimacy, from the perspective of those subject to police power, is ‘a psychological property of authorities which leads those governed by them to perceive their power as acceptable and justified’ (Hamm et al., 2022; Martin & Bradford, 2021; Tyler, 2006). While this conceptualisation of legitimacy relies on an empirical account drawn primarily from social psychology and is heavily influenced by Easton’s (1965) approach to ‘diffuse’ support (Tyler, 1990), contemporary policing research also takes advantage of the normative approaches adopted by political philosophers in conceptualising legitimacy. Following Tankebe’s (2008) approach to Beetham’s (1991) three-component model in the study of police legitimacy, Jackson and Bradford (2010) specified three criteria to determine police legitimacy: obligation to obey, normative alignment, and legality.

‘Obligation to obey’ concerns the expressed consent from the public—whether people feel a moral duty to follow police officers’ instructions even if they disagree with their content and/or those decisions go against their self-interest. ‘Normative alignment’ assesses the moral foundations of policing by measuring the degree to which people feel that they share similar moral values and judgements with the police (in other studies, trust and confidence in the police are held to imply broadly the same sense of value alignment). Lastly, ‘legality’ concerns people’s perceptions of police behaviours—do they believe that police actions are legally valid and justifiable? However, it has been suggested that perceived lawfulness, or legality, cannot capture individuals’ experiences in everyday experiences of the police as people rarely rely on the law when they evaluate police behaviour (Meares et al., 2015; Worden & McLean, 2018). Perhaps as a result, in recent policing studies, police legitimacy has generally been conceptualised and measured as either (a) obligation to obey the police and the normative alignment with the police (e.g. Bradford, et al., 2017a, b; Huq et al., 2017; Kyprianides et al., 2022; Trinkner et al., 2018) or (b) as general trust and confidence in the police, sometimes with or/and sometimes without obligation to obey (e.g. Li, 2018; Murphy, 2013; Wolfe & McLean, 2021).

Psychological underpinnings of procedural justice theory

Within the procedural justice literature, there has long been a concern with the question of why and when are people willing to accept decisions made by authorities when those decisions cut against their objective and subjective self-interest. Early political science accounts such as social exchange theory suggested that individuals are self-interested, rational, and calculated in exchanging their resources in order to maximise their chances of survival and success in social systems (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Within this theoretical climate, Thibaut and Walker (1975, 1978) explored how perceived procedural justice in criminal proceedings could enhance disputants’ willingness to accept decisions made by the authorities even when those decisions were not favourable to them. Based on the self-interest account, Thibaut and Walker’s (1975) control model of procedural justice argues that people care about procedural justice because they desire fair—and thus potentially favourable—outcomes. Given an embedded power relationship with the authority, disputants seek the opportunity to have their ‘voice’ in the criminal justice procedures so as to maximise the likelihood of reaching a fair outcome by allowing the authority to make decisions based on the evidence presented by different parties. This implies that procedural justice matters to people because it provides them with indirect control over their outcomes, where greater control indicates a greater chance of achieving the subjectively ‘right’ outcome.

Noting that the self-interest model has shortcomings in terms of explaining the apparent importance in fairness judgements of non-instrumental procedural factors such as polite and dignified treatment, Lind and Tyler (1988) proposed the Group Value Model (GVM), one of the earliest attempts articulating the relational value of procedural justice. Based on the group identification process, the GVM argues that people care about how authorities treat them because this provides information about their relationship with the authority. With the assumption, widely shared with early theories of social identification, that group membership is an important source of self-esteem and identity for individuals (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), on this account, procedural justice matters because people desire to be included and accepted by social groups that they perceive to be important.

In PJT, the police are often positioned as ‘proto-typical group representatives’ (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003b), who generally symbolise nations or communities (Bradford et al., 2014a), such that police officers and citizens are conceptualised as authorities and subordinates within a shared social group. With the assumption that individuals tend to value feedback from in-group authorities more than out-group authorities (Smith et al., 1998), the GVM proposes that police procedural justice matters more to those with stronger identification with the social group or the group of/represented by the police. According to this model, social identity is thus a positive moderator of the effect of procedural justice perception on legitimacy.

Subsequent to the GVM, Tyler and colleagues developed the Group Engagement Model (GEM). With an acknowledgment on the cognitive and evaluative components of social identity (Blader & Tyler, 2009), the GEM proposes that the positive identity-relevant information conveyed by procedural justice has the capability to shape the individuals’ social identification with the group embodied and/or represented by the police (Tyler & Blader, 2003). Strengthened social identification with the group then, in turn, encourages positive legitimacy judgements, since people are motivated to support the authorities of groups marked by appropriate—just—social relationships (Bradford et al., 2017a, b; Turner & Reynolds, 2010). Accordingly, since social identity thus serves as a mediator to ‘explain’ the effect of procedural justice on legitimacy, the GEM is also referred to as the ‘social identity mediation hypothesis’ by Tyler and Blader (2003).

A third and relatively less discussed model of procedural justice is the Uncertainty Management Model (UMM) proposed by van den Bos and Lind (2002). Although the UMM also addresses the value of procedural justice based on the social identification process, it argues for a different motivational underpinning of the process based on the subjective uncertainty reduction model of motivation (Hogg, 2001). Under this model, the social identification process is driven by people’s need to reduce their sense of uncertainty—they want to affirm a social identity to resolve their sense of uncertainty in contexts that are new, unfamiliar, or unsettling. Those who feel uneasy about their relationship with authorities, or in other words have a weak identification with the authority, and/or who are uncertain about what to expect from authorities, want more information about the authority’s trustworthiness before they decide how to react to an outcome that they received from the authority (van den Bos & Lind, 2002). While positive identification with the authority can provide such reassurance, it is hypothesised that procedural justice matters more to those who are less certain about their relationship with the police (i.e. having weaker social identification with the police). Social identity is a negative moderator of the association between procedural justice and legitimacy on this account. Such negative moderation hypothesis is also shared by the perspective of system justification theory, in which individuals from the minority or low-status group are inclined to accept the status quo (including seeing system and the police legitimate) due to their need for order and stability (Blount-Hill, 2019).

These three social identity-based models have different claims on the effect of social identity on how procedural justice correlates to legitimacy. Our first objective is to review evidence from existing studies to assess how well these models are supported empirically. With the increasing numbers of studies looking into social identity in their articulation of procedural justice and legitimacy, it is necessary to evaluate these models when we advance the theorization of the social identification process in PJT.

Social identity thus plays a vital role in explaining why procedural justice matters. Arguably, though, the concept of social identity current in the (policing) PJT literature is out of kilter with current thinking within the field of social psychology, where social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorisation theory (SCT) (Turner et al., 1987)—the ‘social identity approach’ (Reicher et al., 2010)—constitute highly influential theories of group processes and intergroup relations. Social identity theorists seek to understand and explain how intergroup dynamics and social identification processes influence individual’s perception, attitudes, and behaviours across various social contexts (Hornsey, 2008). Putting this into the context of policing, Reicher (1984, 1987, 1996) and other contemporary crowd psychologists have sought to understand how social identity plays a role in transforming participants’ cognition, relation, and emotion in crowd events such as protests and riots (Drury & Reicher, 2020). When category distinctions are salient, individuals tend to shift from their personal identity to the ‘social identity’, which derives from the social categories that they belong to, enabling them to see and think the social world through the lens of the group (Stott & Radburn, 2020). As a result, group values and norms come to serve as the basis for the cognition and behaviour of members, including their perception of police legitimacy (Stott et al., 2017). Most relevant for current purposes, the social identity approach problematises the idea that police represent an over-arching or dominant identity category towards which people simply orient themselves. Instead, ‘the police’ are positioned as one of many categories that may be relevant to people within a particular context, and it is the extent to which people identify with the police that is important in transforming perceptions of procedural justice into legitimacy. This account has started to gain traction in PJT research and is included in the current review.

Operationalization of social identity in studies of procedural justice and legitimacy

There are three primary ways in which social identity is conceptualised and operationalised (or the kinds of social groups measured) in existing policing studies, each of which subtly shifts the underlying model. The most common and traditional approach derives from the perspective of the GEM, that the police are regarded as a ‘proto-typical group representative’ (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003b) or a symbol representing nations, communities, or neighbourhoods (Bradford et al., 2014b). Based on this assumption, social identity is operationalised as an individuals’ level of identification with a superordinate group (a higher-level social group that includes lower-level social groups as subgroups) represented by the police, which is commonly taken as one’s nations and communities, as well as the notion of the ‘law-abiding citizens’ (e.g. Murphy & Cherney, 2018; Tyler & Jackson, 2014). This approach heavily relies on the assumption that police officers are seen to act as pre-defined ‘moral arbiters’. Since the prototypicality of police in representing the moral values of a nation or community is generally assumed without testing in most studies, this could be problematic when it is applied to situations where people do not see police as representative of these superordinate categories. For example, police might be perceived by protestors as hostile outsiders who attack their community rather than being prototypical representatives of it (Radburn & Stott, 2019).

Building upon empirical findings from studies on policing crowd events (e.g. Stott et al., 2008), a different approach is to measure social identity via relational identification with the police (e.g. Kyprianides et al., 2021; Radburn et al., 2018). Here, the assumption is that police do not simply represent a superordinate social category, but they are seen as a distinct and possibly separate group by those being policed. From the perspective of those engaging with police, identification with the police can be activated and enhanced by the experience of procedural justice; or it can be damaged or undermined by the experience of procedure injustice. Relational identification is thus measuring the extent to which police are positioned as an in- or out-group, based on the judgement of their behaviours. Given that measuring relational identification with the police is argued to be more context specific, and that superordinate categories may be less salient to individuals during encounters with police, there have been moves towards adopting relational identification measures in recent procedural justice studies (Kyprianides et al., 2022; Murphy, 2023; Radburn et al., 2018).

Dichotomous social categorisation is a third approach to conceptualising social identity. Rather than measuring identification with assumed shared social categories or the social group of police with a continuous scale, a small number of studies (e.g. Blount-Hill, 2020; Saulnier & Sivasubramaniam, 2021) consider respondents’ perceptions of their relationship with the police in terms of whether police are perceived as the in-group authority or a (dominant) outgroup. Given that social identity is a complex and fluid concept to be studied, some rarer approaches to social identity are recognised but cannot be included in this review.

The second objective of our review is to evaluate these different approaches to measuring social identity in PJT research. In particular, we consider which if any is the stronger predictor of police legitimacy.

The effect of procedural justice on legitimacy: the (in)variance claim

Much existing research has considered the impact of contextual factors aside from social identity on the relationship between procedural justice and legitimacy in policing. Thus far, it is not clear whether the relationship between procedural justice and legitimacy is consistent or ‘invariant’ (Wolfe et al., 2016). While some studies suggest that age, gender, and ethnicity may moderate the procedural justice to legitimacy pathway (Fine et al., 2020; Kahn & Martin, 2016; Sargeant et al., 2014; Sun & Wu, 2022; Tyler & Huo, 2002), others indicate that this association does not vary across demographic categories such as ethnicity, gender, education, age, income, or ideology (Huo, 2003; Tyler, 1994, 2000, 2004; Wolfe et al., 2016). In order to address this ‘invariance thesis’, the last objective of this review is to test the effects of contextual factors on the correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy.

We consider here whether the socio-demographic characteristics of research subjects—age, gender, and ethnicity—moderate the association between procedural justice and legitimacy. We also explore the potential impact of social context, focussing on two aspects of the wider societal context within which police-public relationships are formed. Given that the majority of PJT studies have been conducted in Western democracies, the generalizability of PJT across cultures and societies is under-explored. For instance, the effect of procedural justice was tested in South Africa and Ghana by Bradford et al., (2014a) and Tankebe (2008), respectively, to address its applicability in ‘less cohesive’ and post-colonial societies. Both concluded that procedural justice could be less influential in these countries than judgements about other aspects of police behaviour, such as effectiveness. Procedural justice could be outweighed by security concerns in less developed countries. Moreover, since procedural justice is a critical element in models of democratic policing (Muntingh et al., 2021) and procedural justice perceptions are thought to be influenced by legal socialisation (Trinkner & Tyler, 2016), people from countries with different levels of democracy might have different ‘baseline’ or underlying perceptions of police procedural justice and legitimacy (and indeed of the relationship between the two).

Systematic review on procedural justice policing

Previous systematic reviews of procedural justice-based policing have demonstrated that procedural justice can enhance police legitimacy (Mazerolle et al., 2013), encourage law compliance (Walters & Bolger, 2019), and promote collective efficacy (Yesberg et al., 2023). Our study builds upon and extends this prior work in a number of ways. First, given the extent of research activity in this area, there is a need to update earlier findings. While our study is certainly similar to the systematic review done by Walters and Bolger (2019), we add evidence from at least 54 samples published since their review (we also limit our attention only to policing, rather than the wider criminal justice system, on the basis that this enables more focussed consideration). Second, and more importantly, previous review studies have not considered why procedural justice links to legitimacy, nor provided a systematic review addressing the role of social identity in PJT. Third, there has been no systematic review exploring the invariance thesis (although see Sun and Wu 2022).

The purpose of this study is thus three-fold. First, we consider which if any of the three social identity models outlined above (GVM, GEM, and UMM) are best placed to explain the link between procedural justice and legitimacy. An iterative set of hypotheses guide this effort. As an initial matter, given that the links between procedural justice and legitimacy, and between social identity and legitimacy, are well established in the literature, we hypothesise that procedural justice positively correlates with legitimacy (H1) and that social identity positively correlates with legitimacy (H2).

It is important to recognise, though, that procedural justice perceptions and social identification can shape legitimacy judgements independently. On one hand, procedural justice does not only carry identity-relevant information, but it also carries instrumental value, as suggested by Thibaut and Walker’s (1975) control model, and can affect one’s emotionality during the encounter (Brown et al., 2022). On the other hand, social identity can encourage group-related attitudes without the presence of procedural justice. Other factors in police encounters, such as bounded authority (Trinkner et al., 2018) and community contacts (St. Louis & Greene, 2020), can also convey identity-relevant signals to those being policed. Thus, it is hypothesised that procedural justice will predict legitimacy while controlling for social identity (H3) and that social identity will predict legitimacy while controlling for procedural justice (H4). Finally, to address the salience of the different social identity models, we hypothesise that the interaction between procedural justice and social identity has a significant association with legitimacy (H5)—i.e. that social identity moderates the association between procedural justice and legitimacy, as proposed by the GVM and UMM—and that social identity mediates the link between procedural justice and legitimacy (H6), as proposed by the GEM.

The second objective of this review is to address the shift of measurement of social identity in PJT studies. Measuring social identity as identification with a superordinate group and as relational identification with the police are based on two rather different sets of assumptions, and we expect to see a difference in the strength of the correlation between social identity and legitimacy between studies adopting different measures.

The third and last objective of this review is to address the (in)variant effect of procedural justice on legitimacy. As mentioned in our literature review, there is still an ongoing debate on the (in)variant effect of procedural justice on legitimacy. To test the effect of contextual factors, a few commonly reported demographics and ratings about the countries in which the studies were carried out were included in our analysis.

Methodology

Selection criteria and search strategy

There are three criteria to select relevant studies for the current study. First of all, since Tyler’s (1990) Chicago study is generally regarded as a foundation for researching PJT in the criminal justice setting, this study thus looks for studies published in/after 1990. Secondly, as this study is interested in the relationship between procedural justice, social identity, and legitimacy, only studies reporting correlations, or other convertible estimates, between any two of these variables are included. Lastly, the focus of this study is on the police-public relationship: only studies with a focus on policing are included. Based on these criteria, four groups of search terms are created: (1) (police OR policing OR “law enforcement”), (2) (“procedural just*” OR “procedural fair*”); (3) (identity OR identification), and (4) (legitimate OR legitimacy). Since we are only interested in policing studies, the first group was combined with two of the remaining three groups to form three searches that were conducted on Abstract/Title/Keywords across three academic research databases commonly used in social science, psychology, and criminology: Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest. To reduce publication bias, grey literature, such as unpublished theses, is included.

The search results were then exported for further screening. After eliminating duplicated studies, 1635 studies were included in the title/abstract screening, of which 642 were subsequently included in the full-text screening. Studies were excluded if their focus of research is not procedural justice policing (‘topic’), not using quantitative research methods (‘methods’), or not measuring at least 2 variables that our study is interested in (‘measures’). Updated searches were performed in October 2022 (four months after the initial search). With additional studies from update searches, 123 studies and 159 samples were included in data extraction and analysis (see Fig. 1).

Data extraction and analysis

After screening, appropriate data were extracted from the included studies for further analysis (see Table 4 in the Appendix). While zero-order correlations were prioritised, other available statistics were extracted and converted into correlations for the studies that do not report bivariate correlations between variables. For instance, standardised beta weights were imputed into correlation coefficients r by using Peterson and Brown’s (2005) method. Together with sample size, Fisher’s z transformation of correlations then could be performed. To deal with missing data, authors were contacted with a request to provide the missing data. In total, we have correlations between procedural justice and legitimacy from 152 samples, the correlations between social identity and legitimacy from 22 samples, the correlations between procedural justice and legitimacy from 26 samples, and the correlations between the interaction item (between procedural justice and legitimacy) and legitimacy from 11 samples. As considerable between-study heterogeneity is anticipated, random effect models were used to pool effect sizes. The heterogeneity variance τ2 was calculated with the restricted maximum likelihood estimator (Viechtbauer, 2005), while the confidence interval around the pooled effect was computed with Knapp-Hartung adjustments (Knapp & Hartung, 2003).

To perform moderator analyses, corresponding data were extracted. The mean age, proportion of males, and ethnic minority proportion of every sample have been recorded to test the effect of these demographics. For democracy and social development level, the latest ratings of the Democracy Index (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021) and the Human Development Index (United Nations Development Programme, 2022) of the countries in which the studies were conducted were extracted. Furthermore, to address the effect of how social identity was measured, the studies were coded into (a) in- vs out-group identification, (b) social identification with the superordinate group, or (c) relational identification with the police for their measure of social identity.

The analysis was conducted in R mainly with the packages ‘meta’, ‘metaSEM’, and ‘dmetar’. Three random effects meta-analyses were conducted to test our first, second, and fifth hypotheses. Based on the assumption that procedural justice perception and social identification are contextual and situational, the random effect model, rather than the fixed effect model, is thus preferred to be used, as considerable between-study heterogeneity is expected in this meta-analysis (Harrer et al., 2021). Univariate effect sizes for correlations between procedural justice (PJ) and legitimacy (Legit) and between social identity (SI) and Legit are pooled from included studies. To assess the effect of interaction between PJ and SI, the correlations between the interaction item (PJ × SI) and Legit were pooled from included studies. For each random effects meta-analysis, heterogeneity (which measures the between-study differences) was assessed with the Q and I2 (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). Influence diagnostics (a test to identify and the cases that cause considerable changes in the fitted model) based on leave-one-out analysis are performed to minimise the effect caused by outliers and influential cases (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010), while Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill procedure (a method to estimate effect size from unpublished studies) is used to address the potential publication bias.

Apart from random effects meta-analysis, random effects two-stage structural equation modelling was adopted to test H3, H4, and H6. Using a structural equation modelling approach in the meta-analysis, the two-stage analysis first pools the correlation matrices from included studies and then treats the pooled correlation matrix as if an observed correlation matrix to fit structural equation models. This approach allows us to perform meta-analysis within the more flexible framework offered by structural equation modelling (Cheung, 2015). Our analysis involves two models: (1) a multivariate model with PJ and SI as independent variables and Legit as the dependent variable and (2) a mediation model with SI as a mediator of the relationship between PJ and Legit. Lastly, to address the possible effect of contextual factors, meta-regression (testing the effect of moderator variables on effect sizes) and subgroup analysis (testing between-group difference in effect sizes based on the subgroups from our moderator variables) were conducted for continuous and categorical variables respectively.

Results

There are 159 samples from 123 studies (N = 200,966) being included in the present meta-analysis (see Table 5 in the Appendix for the summary). While the majority of included studies (k = 152) measure police procedural justice and legitimacy, 22 samples measure social identity and legitimacy, and 19 samples reported all three correlations of interest (PJ-Legit, SI-Legit, and PJ-SI). Table 1 summarises the results of the random effect meta-analysis on the correlations of PJ-Legit, SI-Legit, and PJ × SI-Legit. First, the results show that both pooled correlations between PJ and Legit, and between SI and Legit are significant, with mean effect sizes of 0.407 (p < 0.0001) and 0.392 (p < 0.0001), respectively. There is also strong evidence of heterogeneity (Q statistic and I2) in both analyses. Based on the influence diagnostics (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010), findings from Jackson et al., (2022a) and Jackson et al., (2022b) are regarded as influential cases in the meta-analysis of the correlation between PJ and Legit, while Bradford, et al., (2014b) is the influential case in that of the correlation between SI and Legit. After the removal of influential cases, the mean effect sizes of both PJ–Legit and SI–Legit correlation were 0.397 (p < 0.0001) and 0.358 (p < 0.0001), respectively, which are slightly lower than the results without the elimination of influential cases yet remain strongly significant. To address potential publication bias, Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill method was used, and the adjusted results, for both PJ–Legit and SI–Legit correlation regardless of removal of influential cases, were similarly lower than before adjustment but still significant. Overall, the associations between both procedural justice and social identity and legitimacy are significant, regardless of the adjustments from the trim and fill method and the removal of influential cases.

To control the effect of procedural justice and social identity against each other, both effect sizes of PJ and SI were imputed into a multivariate model. By conducting two-stage structural equation modelling with the R package ‘metaSEM’, a multiple regression model with PJ and SI as the independent variables was estimated. The results show that the partial effects of PJ and SI on Legit are 0.287 and 0.267 (95% CI [0.230, 0.337] and [0.175, 0.355]), respectively. The correlation between PJ and SI was 0.356 (95% CI [0.258, 0.454]). The effects of procedural justice perception and social identity on legitimacy judgement were similar and significant.

After testing the effect of PJ and SI in univariate and multivariate models, a random-effect meta-analysis is performed for the effect of interaction between PJ and SI (PJ × SI) on Legit (see Table 1) (i.e. the identity moderation hypothesis). The results suggest that the pooled PJ × SI–Legit correlation tends to be negative but insignificant, regardless of the influential cases removal. Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill method suggests that no studies are to be added to adjust for the potential publication bias. The correlation between PJ × SI and Legit is found to be insignificant.

To test the identity meditation hypothesis, effect sizes of PJ-Legit, SI-Legit, and PJ-SI are taken into a random effect two-stage structural equation modelling meta-analysis with the R package ‘metaSEM’. Since most studies only measure or report the PJ-Legit correlation, only matrices from those reporting all three correlations (k = 19, N = 26,169) were positive definite and thus included. The results show that all three paths (PJ-Legit, SI-Legit, and PJ-SI) are significant with the effect sizes of 0.430, 0.250, and 0.311 (95% CI [0.307, 0.551], [0.143, 0.351], and [0.214, 0.407]), respectively, whereas the indirect effect was also significant with estimate of 0.078 (95% CI [0.048, 0.115]). Moreover, the mediation model fits the data closely, with χ226,169 < 0.001 (p < 0.001), RMSEA < 0.001, and CFI ≈ 1.0.

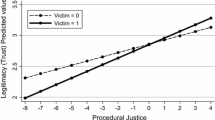

Finally, moderator analyses were conducted on the meta-analysis results of PJ–Legit and SI–Legit to test the effect of contextual factors (see Table 2). For the effect of demographic differences including age, gender, and ethnicity, the only significant result is that age significantly moderates the PJ–Legit relationship (F (1, 120) = 3.929, p = 0.050). This suggests that procedural justice may be a more important predictor of legitimacy among adolescents and young adults than older individuals. Regarding the effect of social contexts, results show that social development has a significant effect on PJ–Legit correlation (p = 0.013). People from more developed countries tend to correlate procedural justice perception to legitimacy more strongly than those from developing countries. On the other hand, none of the contextual factors in our analysis seem to moderate the correlations between social identity and legitimacy.

Table 3 summarises the results of subgroup analysis on social identity measures. The way how social identity was measured in PJT studies significantly affects the correlation between social identity and legitimacy (p = 0.011). Among all, measuring social identity as relational identification with the police provides the strongest mean effect size on SI–Legit correlation with the lowest heterogeneity (cor = 0.551, 95% CI [0.422, 0.658], I2 = 64.6%).

Discussion

Since Tyler’s (1990) ground-breaking research on procedural fairness in criminal justice settings, criminologists have been investigating how procedural justice could be used to promote police legitimacy and public compliance. Although social identity was central in developing different relational models of procedural justice in early PJT research (e.g. Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Blader, 2000; Tyler & Lind, 1992), until recently, few criminological studies have focussed on the psychological processes underpinning the link between procedural justice and legitimacy. However, given recent attention to the role of social identity (26 studies in our review addressed social identity, 21% of all included studies), this is a timely moment to consider the place of social identity in our understanding of police procedural justice and legitimacy.

This meta-analysis addressed the interplay between procedural justice, social identity, and legitimacy in policing, as well as the potential effect of contextual factors on these relationships. Our findings suggest, first, that both procedural justice and social identity are correlates of legitimacy (H1 and H2). Moreover, when entered into a multivariate model, both procedural justice and social identity positively predict legitimacy while controlling for the effect of each other. In this limited sense, procedural justice and social identity have ‘unique’ statistical effects on legitimacy (H3 and H4).

With the foundation built upon H1 to H4, the social identity moderation and mediation hypotheses were then tested. Results suggest that the correlation between the interaction between procedural justice and social identity and legitimacy is non-significant, albeit with a tendency towards the negative. This implies that the strength of identification with the social group associated with police does not moderate the association between procedural justice and legitimacy. H5 is thus rejected; our meta-analysis does not support the GVM or the UMM. This result has to be interpreted carefully, however, because the meta-analysis was conducted using only 11 samples, which are mostly from studies in the UK and Australia.

Nevertheless, social identity is found to be a significant mediator of the correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy of the police. H6 is thus supported, and we find evidence in support of the GEM. We note that the putative causal relationship between these variables—i.e. that the experience of procedural justice strengthens identification with the group, and thus legitimacy—is assumed theoretically but very rarely empirically tested. More longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to the underlying causal processes. In addition, with the majority of the 19 included studies included in the mediation analysis conducted in the UK and Australia, the generalizability of these findings could be limited.

Our second objective was to review the implications of the differences in measuring social identity across existing PJT studies. Our findings suggest that measuring social identity as relational identification with the police shows a stronger correlation with legitimacy judgements and a lower heterogeneity than the other two ways of measuring social identity. This lower heterogeneity suggests that there are fewer unaddressed contextual effects on the results, which could imply that measuring social identity as relational identification with the police is less context-dependent than the other approaches. Measuring social identity via identification with superordinate group(s) relies on the assumption that police are seen as a significant prototypal representative of the group. This tends to overlook to the fact that there are likely to be many factors shaping this identification that are not associated with police. Thus, considering relational identification with the police in the conceptualisation and operationalization of social identity in policing PJT research might be a more accurate way to assess how identity processes shape and interact with the relationship between procedural justice and legitimacy. That said, our findings do identify an association between superordinate identification and legitimacy, which may among other things say something about how police legitimacy is reproduced over time. People who identify with dominant groups in society tend to legitimise police, and this is to some extent independent of their assessments of procedural justice (Bradford, 2016).

Our last objective was to test the ‘invariance thesis’. Our results suggest that the correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy seems to be moderated by age and social development level. The correlation between the two tends to be stronger among younger people, and those from more developed countries. This does not mean that procedural justice is not important for others (e.g. older people), but it does suggest that other antecedents of legitimacy could be relatively more salient to them. Given that legal socialisation has been one of the focuses in PJT studies (e.g. Trinkner & Tyler, 2016; Trinkner et al., 2020), it is perhaps not surprising that age acts as a moderator.

By contrast, although the policing of ethnic minority communities has been a concern particularly in western countries, in part because of the historical intergroup relationship between the police and the ethnic minority communities (e.g. Boehme et al., 2022; Jackson et al., 2023; McLean, 2017), our findings show that ethnicity does not seem to moderate the association between procedural justice and legitimacy. While Sun and Wu (2022) concluded that race/ethnicity moderates the effect of procedural justice on legitimacy by reviewing US-based studies, this phenomenon might be confined in the USA, or to other contexts marked by significant (racial/ethnic) intergroup tensions. We did identify potential moderating effects from gender, or the level of democracy. In addition, no significant impact was found from our hypothesised moderators on the correlation between social identity and legitimacy. This could imply that social identity predicts legitimacy to a similar extent across people from different demographic backgrounds and social contexts. The association between social identity and legitimacy may therefore be less “context dependent” than might be imagined.

In sum, the meta-analysis seems more supportive of the invariance thesis than not. In general, the associations between procedural justice and legitimacy (and between social identity and legitimacy) do not seem to vary much across people from different demographic backgrounds and social contexts—although this is a mixed picture, and more work would be needed to expand on the limited findings presented here.

Implications

Our findings have significant implications for PJT in both theory and practice. Coherent with many previous studies, including the meta-analysis conducted by Walters and Bolger (2019), we find that procedural justice significantly correlates with legitimacy. But we also show that social identity can also be a significant antecedent of legitimacy, even taking procedural justice into account. Our analysis addresses the social identity mediation and moderation hypotheses and indicates support for the GEM. It seems that procedural justice treatment from the police can shape people’s identification with the superordinate group embodied, or the social group represented, by the police, such that, in turn, the police as in group members tend to be perceived as more legitimate.

Our second theoretical contribution concerns the conceptualisation and operationalisation of social identity in PJT. As mentioned, there has been a shift in quantifying social identity in survey studies away from simply measuring presumed shared social group towards a relational approach and measuring identification with police as a distinct social category. Our subgroup analysis considering different approaches to measuring social identity suggests that relational identification with the police seems to be a less context-dependent predictor of police legitimacy, meaning that it could be more ‘accurate’ to consider, and measure, social identity as relational identification. However, it is also the case that there is consistent evidence of associations between police procedural justice and the strength of identification with more expansove categories, such as ‘the community’, or even ‘the state’ in a broader sense (Blount-Hill & Gau, 2022). In sum, it would seem that measures of both types of identity have a role to play, and future studies concerned with the mediating role of identity should consider including both. Again, though, existing PJT studies focussing on social identity are largely from the UK and Australia; other countries were underrepresented in current findings.

Lastly, our moderator analysis addresses some contextual variance of how procedural justice and social identity correlate with legitimacy. It seems that age and social development level are significant moderators of the correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy, but gender, race/ethnicity, and level of democracy are not. The correlation between social identity and legitimacy was not moderated by any of the variables that we tested. This could imply that the effect of procedural justice on legitimacy can vary depending on background and context, whereas the link between social identity and legitimacy is more consistent. The effectiveness of police attempts to promote legitimacy via procedural justice may thus also vary by context: perhaps most obviously, it would seem that procedural justice might be particularly important for younger people.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, although PJT can be applied in other criminal justice settings, such as courtrooms and prisons, as well as the workplace and elsewhere, this study confines its scope to the context of policing, and thus, results are limited in this area. Second, while this study focuses on the relationship between procedural justice perceptions, social identity, and legitimacy judgements, future studies on social identity in PJT could usefully be extended to include behavioural measures, such as compliance and cooperation with the police.

Third, among the 159 included samples, only 11 of them reported the correlation between the procedural justice—social identity interaction and legitimacy judgements. Similarly, there are a very limited number of studies measuring social identity as in-group vs out-group and relational identification. Although it is possible to conduct a meta-analysis on a small number of studies, the estimation of between-study heterogeneity could be difficult and may result in biased effect estimates (von Hippel, 2015).

Fourth, this review only includes studies in English. More inclusive analysis could be done if studies in other languages can be included in the future. This also leads to another limitation that most studies are representative of dominant group members in English-speaking countries (i.e. white Americans, white Europeans) but not of minorities, although a few do focus on ethnic minority groups. Finally, the specific social and indeed policing situations upon which some studies focussed were not taken into account in our analysis. Results from studies on crowd policing could be quite different from those focussing on more ‘routine’ police encounters, for example because encounters in crowd events are conceptualised as inter-group contact rather than inter-personal, as in many ‘routine’ interactions with the police (Reicher et al., 2004).

Conclusion

Given its recent attention in policing PJT research, this paper offers a timely review on the effect of social identity and social contexts on the extent to which police procedural justice leads to legitimacy. By using a meta-analytical approach, this study systematically reviews published evidence of the potential effects of social identity and contextual factors on the relationship between procedural justice and legitimacy in the context of policing. Controlling for procedural justice, social identity is found to be significantly correlated with legitimacy: identification seems to be another important source of police legitimacy. Moreover, our findings support the GEM, and the idea that procedural justice perceptions shape social identification with groups, which in turn shapes legitimacy judgements. By contrast, social identity seems not to moderate the link between procedural justice and legitimacy; our findings are less supportive of the GVM and UMM of procedural justice. By testing these relational models of PJT, this paper points out that social identity can be one of the important social psychological processes mediating the relationship between the perception of procedural justice and legitimacy and therefore that our assumptions about their relations need to be revisited through further research.

The question of contextual variance in the extent to which procedural justice and social identity correlate with legitimacy was addressed via moderator analysis. Age and social development level were found to have significant impacts on the correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy, whereas the correlation between social identity and legitimacy is not affected by any hypothesised moderators. In other words, social identity may be a less context-dependent predictor of legitimacy, whereas the effect of procedural justice can vary across different social groups and settings. While the content of social identity (i.e. beliefs about what it means to be a member of a social category) and group boundaries (i.e. who is in-group or out-group) can be highly dependent on social contexts, our study indicates that future PJT research should steer towards understanding the precise context of situationally embedded interactions with police, as well as the interplay of multidimensional group identities.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate the potential importance of social identities and social contexts for understanding how and why procedural justice encourages legitimacy judgements. While Hamm et al. (2022) called for a more precise conceptualisation of legitimacy, they also placed the dialogic components of legitimacy at the core of their model. Our analysis of the available evidence suggests that social identity is an important component in the dialogue of legitimacy and that this social psychological factor interacts with context to play an important role in the interactional dynamics between police and citizens. Currently, PJT research has been dominated by survey methodology, where, inevitably, measures of identity are rather blunt and static. We suggest that PJT studies could therefore fruitfully adopt more diverse methodologies in the future so that the types of embedded group identities likely to be important for legitimacy can be conceptualised more precisely.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akinlabi, O. M. (2017). Young people, procedural justice and police legitimacy in Nigeria. POLICING & SOCIETY, 27(4), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1077836

Akinlabi, O. M. (2018). Why do Nigerians cooperate with the police? Legitimacy, procedural justice, and other contextual factors in Nigeria.

Aksu, G. (2014). Winning hearts and minds in counterterrorism through community policing and procedural justice: Evidence from Turkey (Publication Number 3629006) [Ph.D., American University]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/winning-hearts-minds-counterterrorism-through/docview/1556640161/se-2?accountid=14511

Antrobus, E., Bradford, B., Murphy, K., & Sargeant, E. (2015). Community norms, procedural justice, and the public’s perceptions of police legitimacy. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 31(2), 151–170.

Aviv, G., & Weisburd, D. (2016). Reducing the gap in perceptions of legitimacy of victims and non-victims: The importance of police performance [Article]. International Review of Victimology, 22(2), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758015627041

Baz, O., & Fernández-Molina, E. (2018). Process-based model in adolescence Analyzing police legitimacy and juvenile delinquency within a legal socialization framework. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 24(3), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-017-9357-y

Beetham, D. (1991). The legitimation of power (2nd (edition). Palgrave Macmillan.

Bello, P. O., & Matshaba, T. D. (2021). Procedural justice, police legitimacy, and performance: Perspectives of South African students [Article]. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1871243

Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T. R. (2015). Relational models of procedural justice. In R. S. Cropanzano & M. L. Ambrose (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of justice in the workplace (pp. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199981410.013.0016

Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T. R. (2009). Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extrarole behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013935

Blount-Hill, K.-L. (2019). Advancing a social identity model of system attitudes. International Annals of Criminology, 57(1–2), 114–137.

Blount-Hill, K.-L., & Gau, J. M. (2022). Future research on legitimacy and its measures. In Understanding Legitimacy in Criminal Justice: Conceptual and Measurement Challenges (pp. 93–108). Springer.

Blount-Hill, K.-L. (2020). Spheres of identity: Theorizing social categorization and the legitimacy of criminal justice officials (Publication Number 28095545) [Ph.D., City University of New York]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/spheres-identity-theorizing-social-categorization/docview/2451391438/se-2?accountid=14511

Boateng, F. D., & Darko, I. N. (2021). Perceived police legitimacy in Ghana: The role of procedural fairness and contacts with the police. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 65, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2021.100458

Boateng, F. D., Pryce, D. K., & Abess, G. (2022). Legitimacy and cooperation with the police: Examining empirical relationship using data from Africa. POLICING & SOCIETY, 32(3), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2022.2037554

Boehme, H. M., Cann, D., & Isom, D. A. (2022). Citizens’ perceptions of over-and under-policing: A look at race, ethnicity, and community characteristics. Crime & Delinquency, 68(1), 123–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128720974309

Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural justice: A dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. The journal of criminal law and criminology, 119–170.

Bradford, B. (2014). Policing and social identity: Procedural justice, inclusion and cooperation between police and public. Policing and Society, 24(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2012.724068

Bradford, B., Huq, A., Jackson, J., & Roberts, B. (2014a). What price fairness when security is at stake? Police legitimacy in South Africa. Regulation & Governance, 8(2), 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12012

Bradford, B., Murphy, K., & Jackson, J. (2014b). Officers as mirrors: Policing, procedural justice and the (re) production of social identity. British Journal of Criminology, 54(4), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2337913

Bradford, B. (2016). The dog that never quite barked: Social identity and the persistence of police legitimacy. Changing contours of criminal justice, 29.

Brasof, M., & Peterson, K. (2018). Creating procedural justice and legitimate authority within school discipline systems through youth court. Psychology in the Schools, 55(7), 832–849. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22137

Bradford, B., Hohl, K., Jackson, J., & MacQueen, S. (2015). Obeying the rules of the road: Procedural justice, social identity, and normative compliance. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 31(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986214568833

Bradford, B., Milani, J., & Jackson, J. (2017a). Identity, legitimacy and “making sense” of police use of force. Policing, 40(3), 614–627. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0085

Bradford, B., Jackson, J., & Hough, M. (2017b). Ethnicity, group position and police legitimacy. Police-citizen relations across the world: Comparing sources and contexts of trust and legitimacy, 70–96.

Bradford, B., Yesberg, J. A., Jackson, J., & Dawson, P. (2020). Live facial recognition: Trust and legitimacy as predictors of public support for police use of new technology [Article]. BRITISH JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY, 60(6), 1502–1522. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa032

Brown, K. L., Walker, D. A., & Reisig, M. D. (2022). The effects of procedural injustice and emotionality during citizen-initiated police encounters [Article]. Journal of Experimental Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09526-w

Brown, K. L. (2019). The impact of procedural injustice during police-citizen encounters: The role of officer gender (Publication Number 13859079) [M.S., Arizona State University]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/impact-procedural-injustice-during-police-citizen/docview/2228137306/se-2?accountid=14511

Brubacher, M. R., Fondacaro, M. R., Brank, E. M., Brown, V. E., & Miller, S. A. (2009). Procedural justice in resolving family disputes: Implications for childhood bullying. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 15(3), 149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016839

Buzarovska, G., Bachanovic, O., Kalajdziev, G., Drakulevski, A. G., Misoski, B., Gogov, B., Ilic, D., & Jovanova, N. (2014). Students’ views on the police in the Republic of Macedonia. Varstvoslovje, 16(4), 435–452. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/students-views-on-police-republic-macedonia/docview/1655548710/se-2?accountid=14511.

Cavanagh, C., LaBerge, A., & Cauffman, E. (2021). Attitudes toward legal actors among dual system youth. The Journal of Social Issues, 77(2), 504–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12441

Chenane, J. L., Morabito, M. S., & Gonzales, T. I. (2022). Perceptions of police among Kenyan female immigrants in the United States. FEMINIST CRIMINOLOGY. https://doi.org/10.1177/15570851221101144

Cherney, A., & Murphy, K. (2013). Policing terrorism with procedural justice: The role of police legitimacy and law legitimacy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 46(3), 403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865813485072

Cheung, M.W.-L. (2015). metaSEM: An R package for meta-analysis using structural equation modeling. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01521

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

Van Damme, A., & Pauwels, L. (2016). Why are young adults willing to cooperate with the police and comply with traffic laws? Examining the role of attitudes toward the police and law, perceived deterrence and personal morality. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 46, 103. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/why-are-young-adults-willing-cooperate-with/docview/1824292430/se-2?accountid=14511

Dittloff, S. A. (2003). The moderating influence among Hispanic students of superordinate group identification and subgroup identification on evaluations of overall procedural justice, overall distributive justice, and overall satisfaction in assessing experiences with law enforcement agencies (Publication Number 3099690) [Ph.D., University of Nevada, Reno]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/moderating-influence-among-hispanic-students/docview/288097122/se-2?accountid=14511

Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2020). Crowds and collective behavior. In Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463.

Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life.

European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC). (2018). ESS5 - integrated file, edition 3.4 [Data set]. Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.21338/ESS5E03_4

Factor, R., Castilo, J. C., & Rattner, A. (2014). Procedural justice, minorities, and religiosity. Police Practice & Research, 15(2), 130. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/procedural-justice-minorities-religiosity/docview/1499023593/se-2?accountid=14511.

Feldman, Y., & Tyler, T. R. (2012). Mandated justice: The potential promise and possible pitfalls of mandating procedural justice in the workplace. Regulation & Governance, 6(1), 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2011.01122.x

Ferdik, F. V. (2014). The influence of strain on law enforcement legitimacy evaluations. Journal Of Criminal Justice, 42(6), 443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2014.08.004

Ferdik, F. V., Wolfe, S. E., & Blasco, N. (2014). Informal social controls, procedural justice and perceived police legitimacy: Do social bonds influence evaluations of police legitimacy? American Journal of Criminal Justice : AJCJ, 39(3), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-013-9230-6

Fine, A. D., & van Benjamin, R. (2021). Legal socialization: Understanding the obligation to obey the law. The Journal of Social Issues, 77(2), 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12440

Fine, A. D., Donley, S., Cavanagh, C., & Cauffman, E. (2020). Youth perceptions of law enforcement and worry about crime from 1976 to 2016. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(5), 564–581.

Fine, A. D., Beardslee, J., Mays, R., Frick, P. J., Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (2022). Measuring youths’ perceptions of police: Evidence from the crossroads study. PSYCHOLOGY PUBLIC POLICY AND LAW, 28(1), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000328

Gau, J. M. (2010). A longitudinal analysis of citizens’ attitudes about police. Policing-An International Journal Of Police Strategies & Management, 33(2), 236–252. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511011044867

Gau, J. M., Corsaro, N., Stewart, E. A., & Brunson, R. K. (2012). Examining macro-level impacts on procedural justice and police legitimacy. Journal Of Criminal Justice, 40(4), 333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.05.002

Granot, Y., Tyler, T. R., & Durkin, A. (2021). Legal socialization during adolescence: The emerging role of school resource officers. The Journal of Social Issues, 77(2), 414–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12446

Grant, L., & Pryce, D. K. (2020). Procedural justice, obligation to obey, and cooperation with police in a sample of Jamaican citizens. Police Practice And Research, 21(4), 368–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1644178

Hamm, J. A., Trinkner, R., & Carr, J. D. (2017). Fair process, trust, and cooperation: Moving toward an integrated framework of police legitimacy. Criminal Justice And Behavior, 44(9), 1183–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854817710058

Hamm, J. A., D’Annunzio, A. M., Bornstein, B. H., Hoetger, L., & Herian, M. N. (2019). Do body-worn cameras reduce eyewitness cooperation with the police? An experimental inquiry. Journal Of Experimental Criminology, 15(4), 685–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09356-3

Hamm, J. A., Wolfe, S. E., Cavanagh, C., & Lee, S. (2022). (Re)Organizing legitimacy theory. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 27(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12199

Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A., & Ebert, D. D. (2021). Doing meta-analysis with R: A hands-on guide. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Hegtvedt, K. A., Johnson, C., Gibson, R., Hawks, K., & Hayward, J. L. (2022). Power and procedure: Gaining legitimacy in the workplace. Social Forces, 101(1), 176–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soab103

Henry, T. K. S., & Franklin, T. W. (2019). Police legitimacy in the context of street stops: The effects of race, class, and procedural justice [Article]. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 30(3), 406–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403417708334

Hertogh, M. (2015). What moves Joe Driver? How perceptions of legitimacy shape regulatory compliance among Dutch traffic offenders. International Journal Of Law Crime And Justice, 43(2), 214–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2014.09.001

Higgins, J. P., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558.

Hinds, L. (2007). Building police–youth relationships: The importance of procedural justice. Youth Justice, 7(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225407082510

Hinds, L., & Murphy, K. (2007). Public satisfaction with police: Using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 40(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1375/acri.40.1.27

Hogg, M. A. (2001). Self-categorization and subjective uncertainty resolution: Cognitive and motivational facets of social identity and group membership.

Hornsey, M. J. (2008). Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x

Huo, Y. J. (2003). Procedural justice and social regulation across group boundaries: Does subgroup identity undermine relationship-based governance? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(3), 336–348.

Huq, A. Z., Jackson, J., & Trinkner, R. (2017). Legitimating practices: Revisiting the predicates of police legitimacy. The British Journal of Criminology, 57(5), 1101–1122. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw037

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2021). Democracy index 2020.

Jackson, J., & Sunshine, J. (2007). Public confidence in policing - A neo-Durkheimian perspective. British Journal Of Criminology, 47(2), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azl031

Jackson, J., Huq, A. Z., Bradford, B., & Tyler, T. R. (2013). Monopolizing force? Police legitimacy and public attitudes toward the acceptability of violence [Article]. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(4), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033852

Jackson, J., Asif, M., Bradford, B., & Zakar, M. Z. (2014). Corruption and police legitimacy in Lahore, Pakistan. The British Journal of Criminology, 54(6), 1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu069

Jackson, J., Bradford, B., Giacomantonio, C., & Mugford, R. (2022a). Developing core national indicators of public attitudes towards the police in Canada. Policing & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2021.1896513

Jackson, J., Pósch, K., Oliveira, T. R., Bradford, B., Mendes, S. M., Natal, A. L., & Zanetic, A. (2022b). Fear and legitimacy in Sao Paulo, Brazil: Police– citizen relations in a high violence, high fear city. LAW & SOCIETY REVIEW, 56(1), 122–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12589

Jackson, J., McKay, T., Cheliotis, L., Bradford, B., Fine, A., & Trinkner, R. (2023). Centering race in procedural justice theory: Structural racism and the under- and overpolicing of Black communities. Law and Human Behavior, 47(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000524

Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2010). Police legitimacy: A conceptual review. Available at SSRN 1684507.

Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2022). On the nature of acquiescence to police authority: A commentary on Hamm et al.(2022). Legal and Criminological Psychology, 27(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12217

Jeleniewski, S. A. (2014). Expanding legitimacy in the procedural justice model of legal socialization: Trust, obligation to obey and right to make rules (Publication Number 3581200) [Ph.D., University of New Hampshire]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/expanding-legitimacy-procedural-justice-model/docview/1547939745/se-2?accountid=14511

Johnson, D., Maguire, E. R., & Kuhns, J. B. (2014). Public perceptions of the legitimacy of the law and legal authorities: Evidence from the Caribbean. LAW & SOCIETY REVIEW, 48(4), 947–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12102

Jorgensen, J. C. (2011). Public perceptions matter a procedural justice study examining an arrestee population (Publication Number 1496666) [M.S., Arizona State University]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/public-perceptions-matter-procedural-justice/docview/883575696/se-2?accountid=14511

Kahn, K. B., & Martin, K. D. (2016). Policing and race: Disparate treatment, perceptions, and policy responses. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10(1), 82–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12019

Karakus, O. (2017). Instrumental and normative pathways to legitimacy and public cooperation with the police in Turkey: Considering perceived neighborhood characteristics and local government performance. Justice Quarterly : JQ, 34(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2015.1095346

Kim, Y. S., Ra, K. H., & McLean, K. (2019). The generalizability of police legitimacy: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and speeding intention of South Korean drivers. Asian Journal Of Criminology, 14(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-018-9278-9

Knapp, G., & Hartung, J. (2003). Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Statistics in Medicine, 22(17), 2693–2710.

Kochel, T. R. (2017). Legitimacy judgments in neighborhood context: Antecedents in “good” vs “bad” neighborhoods. Policing, 40(3), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2016-0066

Kochel, T. R. (2018). Police legitimacy and resident cooperation in crime hotspots: Effects of victimisation risk and collective efficacy. Policing & Society, 28(3), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1174235

Kruger, D. J., Nedelec, J. L., Reischl, T. M., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2015). Life history predicts perceptions of procedural justice and crime reporting intentions [Article]. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 1(3), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-015-0021-9

Kyprianides, A., Bradford, B., Jackson, J., Yesberg, J., Stott, C., & Radburn, M. (2021). Identity, legitimacy and cooperation with police: Comparing general-population and street-population samples from London [Article]. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 27(4), 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000312

Kyprianides, A., Bradford, B., Jackson, J., Stott, C., & Posch, K. (2022). Relational and instrumental perspectives on compliance with the law among people experiencing homelessness. Law and Human Behavior.

Lawrence, T. I., McField, A., & Freeman, K. (2021). Understanding the role of race and procedural justice on the support for police body-worn cameras and reporting crime [Article]. Criminal Justice Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/07340168211022794

Lee, Y. H., & Cho, S. (2020). the significance of instrumental pathways to legitimacy and public support for policing in South Korea: Is the role of procedural fairness too small? [Article]. Crime, Law and Social Change, 73(5), 575–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09876-z

Lee, S., & Lee, J. (2021). Impact of propensity to trust on the perception of police: An integrated framework of legitimacy perspective [impact of propensity to trust]. Policing, 44(6), 1108–1122. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-03-2021-0036

Li, L. (2018). Procedural justice and police legitimacy: Untangling the effects of race/ethnicity-based situation and organizational characteristics of police agency (Publication Number 10843151) [Ph.D., University of Delaware]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/procedural-justice-police-legitimacy-untangling/docview/2131359658/se-2?accountid=14511

Lim, C. H., & Kwak, D. H. (2022). factors influencing public trust in the police in South Korea: Focus on Instrumental, expressive, and normative models. SAGE OPEN, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211068504

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Plenum.

Liu, S., & Nir, E. (2021). Do the means matter? Defense attorneys’ perceptions of procedural transgressions by police and their implication on police legitimacy. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 32(3), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403420915252

Liu, J., Wu, G., & Boateng, F. D. (2020). Does procedural fairness matter for drug abusers to stop illicit drug use? Testing the applicability of the process-based model in a Chinese context. Psychology, Crime & Law : PC & L, 26(5), 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2019.1696802

Lorenz, K. (2017). Reporting sexual assault to the police: Victim experiences and the potential for procedural justice (Publication Number 10818114) [Ph.D., University of Illinois at Chicago]. Criminal Justice Database; ProQuest Central. Ann Arbor. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/reporting-sexual-assault-police-victim/docview/2026687913/se-2?accountid=14511

Lowrey, B. V., Maguire, E. R., & Bennett, R. R. (2016). Testing the effects of procedural justice and overaccommodation in traffic stops: A randomized experiment. Criminal Justice And Behavior, 43(10), 1430–1449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816639330

Lukic, N., Bajovic, V., Ticar, B., & Eman, K. (2016). Trust in police by Serbian and Slovenian law students: A comparative perspective 1. Varstvoslovje, 18(4), 418–437.

MacQueen, S., & Bradford, B. (2013). The Scottish Community Engagement Trial (ScotCET). In Scottish Institute for Policing Research Annual Report (Vol. 18). http://www.sipr.ac.uk/downloads/SIPR_Annual_Report_13.pdf

Madon, N. S., & Murphy, K. (2021). Police bias and diminished trust in police: A role for procedural justice? Policing-An International Journal Of Police Strategies & Management, 44(6), 1031–1045. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-03-2021-0053