Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study is to estimate the price of retribution.

Methods

Based on administrative data on all sentences in the Netherlands in 2012 and recidivism from 2012 to 2018, we first investigate whether community service orders are more effective in reducing recidivism than short-term imprisonment using an instrumental variable approach. Next, we compute the cost savings that could be obtained by replacing short-term prison sanctions with equivalent community service orders.

Results

We find that short-term prison sanctions lead to an increase in recidivism and an increase in the costs of sanctioning. We find that Dutch society pays about 400 million euros per year for retribution. This is about 21,000 euros per sanctioned offense per year and about 45 euros per taxpayer per year in the Netherlands. This is most likely a lower bound.

Conclusions

Our study reveals the willingness to pay for retribution as implied by judicial choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A vast amount of literature has analyzed the consequences of different types of punishment on recidivism. Much of this literature focuses on monetarily expensive types of punishment in the form of custodial sentences compared to the relatively monetarily inexpensive types of punishment of non-custodial sentences (e.g., Durlauf & Nagin, 2011; Nagin et al., 2009; Tonry, 2011). Prior analyses of the effect of custodial sentences on recidivism have shown mixed results, although consensus leans towards a weak criminogenic effect of prison sentences compared to non-custodial alternatives. For meta-analyses of earlier studies, we refer to Jonson, (2010), Loeffler and Nagin, (2022), Petrich et al., (2021), Smith et al., (2002), and Villettaz et al., (2015). The few recent studies that find crime-preventative effects of imprisonment are typically conducted in settings that emphasize rehabilitative programming, such as Norway and Sweden (Bhuller et al., 2020; Hjalmarsson & Lindquist, 2022) or in juvenile settings (Eren & Mocan, 2021).

Whereas studies included in existing meta-analyses have primarily used regression analyses or matching techniques (see Bales & Piquero, 2012; Loughran et al., 2009; Meade et al., 2012; Mears et al., 2016; Nieuwbeerta et al., 2009; Ramakers et al., 2014; Rydberg & Clark, 2016; Snodgrass et al., 2011; Wermink et al., 2010, 2017), more recent evidence follows Kling, (2006) and analyzes the effect of imprisonment on recidivism using instrumental variables (IV) techniques (Andersen, 2019; Bhuller et al., 2020; Dobbie et al., 2018; Ertefaie et al., 2018; Harding et al., 2017, 2019; Loeffler, 2013; Mueller-Smith, 2015; Stam et al., 2023; Wermink et al., 2023). These studies exploit the randomness in the selection of judges in criminal cases. The main advantage of using IV with random assignment instruments over regression and matching analyses is that the method overcomes the problem of endogeneity between recidivism and punishment, while it is less sensitive to offenders’ unobserved characteristics, i.e., omitted variables (Angrist, 2006). This is an important advantage because prior regression and matching studies were typically only able to control for a limited set of observed confounders (Nagin et al., 2009; Wermink et al., 2023). For a detailed account of the history and applications of IV methods, see Angrist and Krueger, (2001) and Angrist and Pischke, (2009). For an overview of IV in criminological research, we refer to Bushway and Apel, (2010) and Wermink et al., (2023).

Prison sentences are generally found to be highly monetarily expensive for society (e.g., Abrams, 2012; Gifford, 2019; Greenberg, 1990; Haynes & Larsen, 1984; Henrichson & Delaney, 2012; McLaughlin et al., 2016).,Footnote 1 In this study, we build upon analyses that identify the costs of crime and punishment to society (Ehrlich, 1982; Waldfogel, 1993) and develop a framework in which the willingness to pay for short-term prison sentences and community service orders is used to determine the price of retribution. In particular, we develop a framework in which judicial decisions regarding sentencing represent society’s preferences to pay for retribution. The approach employed by Wermink et al. (2023) is used to identify the effectiveness of short-term prison sentences and community service orders in reducing recidivism. This is an important input for analyzing the willingness to pay for prison sentences and community service orders, especially since the general deterrence and incapacitation effects of short-term sentences are likely to be small in the Netherlands (WODC, 2008 and Wermink et al., 2010, 2013, respectively).Footnote 2,Footnote 3 Identifying the costs associated with short-term prison sentences and community service orders completes the picture of willingness to pay. Based on this framework, we can estimate the price that society actually pays for retribution by means of short-term prison sentences—the price paid for imprisoning offenders beyond its crime-reducing effect.

Retribution is an important issue in judges’ verdicts, but—to our knowledge—has never been priced before. This is a significant gap given that prior work identifies cost-benefit analysis as the key to understanding whether interventions provide economic benefit and whether it is worthwhile to implement them on a large scale (Weisburd et al., 2017). Prior studies have mainly identified the price of (different types of) crime to society (e.g., Anderson, 1999; Brand & Price, 2000; Cohen, 2005; Dolan et al., 2005; Gibbons, 2004), the price of incarceration to society (e.g., Abrams, 2012; Gifford, 2019; Greenberg, 1990; Haynes & Larsen, 1984; Henrichson & Delaney, 2012; McLaughlin et al., 2016), or even people’s willingness to pay for reductions in crime (e.g., Baker et al., 2013; Bishop & Murphy, 2011; Brenig & Proeger, 2018; Cohen, 2015; Cohen et al., 2004; Lynch & Rasmussen, 2001; Nagin et al., 2006). Without exception, these studies indicate that imprisonment is relatively expensive to society and people are willing to spend a non-negligible amount of money to reduce crime. However, no study has analyzed societies’ price paid for retribution. Therefore, this study is the first-ever attempt to attach a price to retribution. To do so, we develop a framework in which administrative data on recidivism can be used to identify society’s willingness to pay for retribution through judicial choices in sentencing.

So far, the willingness to pay for retribution has only been studied using stated preference analyses of respondents. These respondents should give a representative picture of citizens’ willingness to pay for retribution. Jones and Weatherburn, (2011) show that Australians are indifferent between rehabilitation and imprisonment, which suggests a low willingness to pay for retribution and a high potential to reduce the costs of imprisonment. The only evidence for the Netherlands comes from a vignette study (Ruiter et al., 2011). Unlike Jones and Weatherburn, (2011), they show that information about the costs of sanctioning has no influence on whether the unconditional prison sentence and community service are considered appropriate punishments (Ruiter et al., 2011). More than 64% of the Dutch respondents also state that the costs of sanctioning should not play a role in determining a sentence. An important difference between the two studies, however, is that the vignettes of Ruiter et al., (2011) speak of “costs” in a general sense, while the vignettes of Jones and Weatherburn, (2011) talk about taxpayers’ money that respondents themselves have to pay more.

This paper makes two substantial contributions to the literature. We are the first to analyze how much society pays for retribution based on administrative information from short-term prison sentences and their effects on recidivism. Using our estimated causal effects of short-term prison sentences on recidivism and the identified net costs of these sentences, we determine the price of retribution using a series of simulation exercises using different scenarios. Unlike most studies asking people’s willingness to pay for a “good/service” by using a stated preferences approach in surveys, like Jones and Weatherburn, (2011) in the case of imprisonment versus rehabilitation, we identify society’s price paid in a framework using revealed preference information (i.e., actual judicial choices). The main advantage of our revealed preferences approach over a stated preferences approach, next to issues regarding the national representativeness of survey samples,Footnote 4 is that surveys may not always elicit people’s actual behavior. Also, the actual price paid may be different than the amount mentioned in the willingness to pay. Since our analysis is based on actual judicial choices, our results reflect the actual price society pays for retribution. This is not necessarily identical to what individuals are actually willing to pay, including taxpayers, policymakers, and sentencers. We discuss this further in the concluding section.

A second contribution of this paper, compared to prior studies that estimate the causal effect of short-term prison sentences on recidivism, is extending the analysis by estimating the effect of imprisonment on different types of crimes. More particularly, violent, property, and other crimes are studied separately. This extension allows us to study the effects of short-term imprisonment in more detail which is relevant as the rational nature of violent crimes, property crimes, and other crimes may vary considerably (Winter, 2020). Also, society’s price paid for retribution may vary between crime types.

Based on administrative data on all sentences imposed in the Netherlands in 2012 and subsequent recidivism in the period 2012–2018, our analysis makes visible how much society indirectly pays for imposing short-term prison sentences over community service orders only. A sanction policy that includes both community service orders and short-term prison sanctions is more expensive than a sanction policy that would include only community service orders. As imprisonment can be considered the more severe sanction of the two (Lappi-Seppala, 2019; Sloan & Miller, 1990), this cost increase can be considered the price judges are willing to pay for retribution.

A framework for pricing retribution

Policy choices may be evaluated using a social welfare function. Essentially, such a function specifies how the welfare of individuals leads to social welfare, that is, the welfare of all citizens together. An optimal policy entails the selection of policy instruments that leads to maximum social welfare. In his seminal paper on crime and punishment, Becker, (1968) applied this line of reasoning to law enforcement. This led to the idea of optimal law enforcement. Since crime and law enforcement generate costs for society, maximizing social welfare is equivalent to minimizing social losses. Hence, Becker used a social loss function. Becker assumes that the social loss is equal to the total loss in real income from offenses, convictions, and punishments. Optimal law enforcement minimizes social loss due to criminal behavior and law enforcement (convictions and punishments). A key element in Becker’s theory is that law enforcement may have a deterrent effect. Increasing the certainty and severity of punishment is expected to increase deterrence, leading to a decrease in the costs of criminal behavior. Yet, both an increase in the probability of punishment and an increase in the severity of punishment lead to an increase in enforcement costs. An optimal enforcement policy minimizes the sum of these costs.Footnote 5

Becker’s approach is, however, missing an important element: retribution. Retribution is based on “just desert,” the idea that punishment should fit the crime (“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”). If citizens have a preference for retribution, this should be included in the social welfare function. Otherwise, Becker’s approach would be a poor guide for policy-makers (Van Velthoven & Van Wijck, 2016). Deterrence and retribution may be conflicting goals. That is, there may be a trade-off between these goals. From a deterrence perspective, optimal law enforcement would lead to the minimization of the costs of crime and law enforcement. Opting for a retributive approach, however, may imply opting for an approach that does not minimize the costs of crime and law enforcement (cf. Ehrlich, 1982; Waldfogel, 1993). This cost increase reflects the price policy-makers are willing to pay for retribution. Clearly, policymakers’ willingness to pay is not necessarily identical to taxpayers’ willingness to pay. We will reflect on this in the concluding section.

The idea of a potential trade-off between deterrence and retribution is related to the discussion of “purposes of punishment,” especially general deterrence, specific deterrence, incapacitation, and retribution. Research suggests that general deterrence and incapacitation can be assumed to play a very limited role in the Netherlands (Wermink et al., 2010, 2013; WODC, 2008), which may be especially true for the type of short-term prison sentences under scrutiny here, so we are left with specific deterrence. Note that thinking in terms of deterrence implies an ex ante perspective; it is about influencing future behavior. Thinking in terms of retribution implies an ex post perspective; it is about a just response to criminal acts.

We consider two types of sanctions: imprisonment and community service orders. Imprisonment is generally assumed to be a more punitive type of sanction (Lappi-Seppala, 2019; Sloan & Miller, 1990). For the Netherlands, this assumption is formalized by articles 61 and 9 of the Dutch Penal Code, which rank order the different sanction types available to Dutch judges based on their assumed severity and in which imprisonment is ranked above community service. Furthermore, according to Article 22b of the Dutch Penal Code, community service orders are excluded as a sentencing option for certain serious crimes. Apparently, the Dutch legislator considers prison sanctions to better fit these serious crimes, as prison sanctions are conceived to be the more serious type of sanction. More generally, retributive considerations may lead to a preference for imprisonment, even if this leads to an increase in the costs of sanctioning. This cost increase would be the price of retribution.

We consider two types of costs related to sanctions: fixed costs of the sanction and daily costs of the sanction. We focus on the difference in costs that depends on the judgment of the judge. The costs preceding the judgment can be considered sunk costs. If a judge opts for a specific sanction, this will determine the costs that originate from the execution of this sanction. Hence, we focus on the difference in costs following the judgments and take the preceding costs as given.

Average sanctioning costs in the case of a prison sentence (subscript p, from “prison”) depend on the number of days of imprisonment Dp, the costs of a day of imprisonment Cp, the fixed costs of an imprisonment sanction Kp, and on qp recidivism after short-term imprisonmentFootnote 6:

Average sanctioning costs in case of a community service order (subscript c, from “community service”) depend on the number of days of community service Dc, the costs of a day community service Cc, the fixed costs of a community service order Kc, and on qc recidivism after community service:

The cost increase that is caused by using short-term prison sentences rather than community service orders can be considered the price of retribution. In practice, we observe both short-term prison sentences and community service orders. Let the number of short-term prison sentences (community service orders) be Vp (Vc). Assuming ACp > ACc in Vp cases, an “expensive” sanction is used. Hence, the cost increase that can be considered the price of retribution is equal to:

Apparently, this cost increase is considered acceptable in order to meet preferences for retribution. In order to compute the price of retribution, we consider the following hypothetical question: what is the cost saving that would be obtained if we replace all short-term prison sanctions (up to 6 months) with community service orders? To answer that question, we first consider the relation between Dp and Dc, that is: how many days of community service are equivalent to 1 day of imprisonment?

Define

Where m represents a conversion key to make prison sentences comparable to community service orders.

A second factor to consider is the difference between the costs of a day of imprisonment Cp and the costs of a day of community service Cc. Data on these costs are presented in Table 4. The third factor to consider is the difference between recidivism after short-term prison sanctions qp and recidivism after community service orders qc.

Define

If β1 > 0, this would imply that the costs of prison sentences increase relative to the costs of community service orders. It is, of course, an empirical question of what the size of β1 is. Together with Eqs. 1–5, β1 allows us to rewrite Eq. 3 in:

In Eq. 6, the term (1 + qp) × (Dp × Cp + Kp) are the costs of short-term prison sentences in cases where only prison sentences are used. The term (1 + qp − β1) × (m × Dp × Cc + Kc) are the costs of community service orders in cases where only community service orders are used rather than short-term prison sentences, taking into account differences in recidivism. β1 and qp take into account the possible differences in recidivism between community service orders and short-term prison sentences in the price of retribution. In this paper, we take Eq. 6 as our central equation to calculate the price of retribution and approximate this price by estimating and assuming logical values for the parameters in Eq. 6. We do this for the total number of crimes as well as for property, violent, and “other” crimes separately.Footnote 7 In the case of the total number of crimes, β1 refers to all registered crimes, including those for which the nature of the crime is not specified.

The Dutch context

The Netherlands is a country measuring 41,543 km2, which is home to a little over 17 million inhabitants. The Netherlands is governed by a uniform criminal procedure and national criminal law and is divided into 11 district courts, 4 courts of appeal, and 1 Supreme Court. Most cases start at a district court, with the location where the crime was committed determining the particular district. The district court generally consists of a subdistrict sector, a criminal law sector, a civil/family law sector, and an administrative law sector. The subdistrict judge is a single sitting judge who deals with minor offenses and typically delivers an oral judgment immediately after the hearing. The judges of the criminal law sector deal with all criminal cases that do not come before the subdistrict judge. These cases can be heard by a single judge or in full-bench panels with three judges. Single-sitting judges enjoy broad discretionary powers in deciding both the type and length of the sentence and may impose penalties of up to one year’s imprisonment. The full-bench panels typically deal with more complex cases and cases in which the prosecution demands a sentence of more than one year’s imprisonment. Each year, over 80% of the cases dealt with by the criminal law sector of the district court, are heard by a single sitting judge (Vink, 2020). Cases are assigned at random to single sitting judges within the district court based on the work schedule, or “zittingsrooster” via an automated process. Two days prior to the court date, the judge’s assignment is made public and thereby definitive, barring serious issues beyond personal control.

From the turn of the century onward, the Netherlands experienced a decline in the prison population, dropping from 94 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants in 2005 to 68 in 2012 and 54 in 2015 (Aebi et al., 2019). These numbers are considered low compared to other European countries. The flow of prisoners entering the Dutch system each year (274, 233, and 254 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2005, 2012, and 2015, respectively) is, however, high compared to the rest of Europe. This is explained by the relatively short duration of the average prison sentence in the Netherlands, which is between 3 and 4 months (Aebi et al., 2019; Linckens & De Looff, 2013). During short periods of confinement, Dutch prisoners are not able to participate in Penitentiary Programs aimed at successful reintegration into society after release. Moreover, in contrast to those serving longer punishments, prisoners serving sentences under 12 months spend a larger part of the day inside their cell (approximately 18 hours), have no opportunities to leave prison to gain work experience, and upon release mostly receive no guidance and supervision from probation officers (RSJ, 2021). Given these limited opportunities for rehabilitation and reintegration, the crime-preventative effects of particularly short-term imprisonment may be limited or nonexistent in the Netherlands.

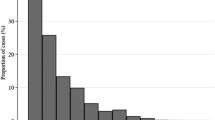

Apart from imprisonment, the main criminal sanctions employed in the Netherlands include fines and community service orders. Community service orders have a maximum duration of 240 hours and can be imposed either independently or combined with either a fine or a prison sentence of up to 6 months. In the Netherlands, suspects sentenced to community service have to perform unsalaried work under the supervision of the probation office. Figure 1 depicts the sanctions imposed by the three major sanction types for the years 2000–2016, both in absolute numbers (left pane) and percentages (right pane). The figure shows that whereas unconditional imprisonment was the most prevalent sanction up to 2007, from 2008 onwards the number of imposed community services topped the number of imposed prison sentences. By 2012, the share of community service orders out of all the main sanctions imposed had more than doubled compared to 2000. Despite a sharp increase in the relative importance of community service orders, unconditional imprisonment remains the Netherlands’ second-most common governmental response to crime.

Data and methods

Our task in this study is to estimate the price of retribution from the estimated causal effects of short-term imprisonment on recidivism. We analyze data from the “Life after Release Study” (LRS), which includes individual-level data from Dutch criminal courts (Wermink & Blokland, 2019). These data were made available by the Research and Documentation Centre (Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum (WODC)) of the Netherlands Ministry of Justice and Security, and contain information on every criminal case disposed of by a single sitting judge in 2012. As mentioned, single-sitting judges in the Netherlands may impose prison sentences of up to 1 year. Judge information was then merged into these court records by the Public Prosecutor’s office, yielding a dataset pertaining to 47,505 individuals with criminal cases, of which 7313 were sentenced to prison and 18,653 received up to 240 hours of community service, and of which the ruling judge was known. Here, imprisonment refers to all unconditional custodial sanctions that resulted in placement in a residential setting, and community service includes programs through which convicted offenders are placed in unpaid positions with non-profit or tax-supported agencies to perform work or service.Footnote 8 For each offender, the entire registered criminal career from the minimum age of criminal responsibility to the calendar year 2019 was compiled from all cases registered by the police at the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In these data, cases that resulted in acquittals or dismissals owing to insufficient evidence were excluded, thereby only including those offenses that were disposed of by a conviction.

From the original sample, we impose several restrictions. Because separate courts and sentences are available for juveniles, and both community service and imprisonment are quite rare among elderly suspects, we excluded all suspects who were younger than 18 and older than 50 (N = 2470). Moreover, community service was introduced to replace prison sentences of up to six months, and, as stated in the Penal Code, no community service order can replace longer prison terms. Because of concerns that offenders with long prison sentences might differ from those sentenced to community service to such a degree that no credible counterfactual can be obtained, we excluded all 162 individuals in the data sentenced to more than six months imprisonment. Finally, six cases with data quality problems were removed. The foregoing restrictions resulted in an analysis sample of 22,793 individuals, representing 89.4% of the original sample. Of these 22,793 individuals, 16,764 received a community service order and 6029 a prison sentence (with a maximum length of 6 months).

The data allow us to analyze different types of offenses. In this paper, we separate property crimes, violent crimes, and a remaining other category. The level of detail of the data is such that we observe combinatory offenses. Cases were classified as ‘other’ when data on offense type was available and when the offense type could not be classified as violent or property, and ‘unknown’ when data on offense type was not available. The data include information on five groups of confounding variables that are known to influence judicial decision-making or recidivism after punishment or both. First, the seriousness of the criminal conduct is captured by the overall severity of the offense based on the statutory maximum penalty and the total number of criminal charges. Second, previous research consistently demonstrates that the type of offense is highly consequential for case processing, and the data include various offense types that cover a range of violent, property, and drug offenses (e.g., Van Wingerden et al., 2016). Third, socio-demographics are captured by information about age, country of origin, and sex. Fourth, district court information is available, which is important given that the setting for the current study is the criminal divisions of all district courts in the Netherlands, and sentences may vary among district courts (Johnson, 2006). Fifth, all previous punishments are known in the data. Descriptive information on the variables included in our analyses is presented in Table 1. This extra information is used to additionally control for selection effects in our instrumental variable analyses and to prevent interference from feedback effects from previous punishments.

In sum, this is a rich, yet surprisingly underutilized data source as it contains detailed information on important confounding variables, judge identifier information, and full criminal careers of a full nationwide population, thus providing a rare opportunity to examine the causal effects of imprisonment versus community service orders.

Estimating the causal effect of imprisonment on recidivism

In this section, we explain how to estimate β1 from Eq. 6. Our 2SLS strategy exploits the variation between judges in the propensity to impose a short-term prison sentence to statistically isolate the influence of short-term imprisonment on criminal behavior after release (Angrist, 2006; Angrist & Krueger, 2001; Angrist & Pischke, 2009). Following Dahl et al. (2014), Dobbie et al. (2018), Bhuller et al. (2020), and Wermink et al. (2023), we use a judge stringency measure as an instrument. Here, we define a judge’s stringency as the share of imprisonment sanctions imposed by that judge in all other cases apart from the one being considered. Using the stringency measure avoids issues associated with many weak instruments when using judge dummies (Angrist & Krueger, 1991; Chao & Swanson, 2005; Davies et al., 2014; Hansen & Kozbur, 2014).

Hence, we estimate the following equations by Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS)

Here, y yields recidivism and Prison a binary variable indicating whether someone received a prison sentence (Prison = 1) or a community service order (Prison = 0). X’ is a vector of control variables including age, gender, country of origin, criminal history, type and severity of the crime, and court district (see Table 1 for details on these variables). Z denotes the stringency of judge j assigned to the defendant i’s case.

The error terms ε and ν are iid ~ N(0,σ) and allowed to be arbitrarily correlated.Footnote 9 In the empirical analysis, we also differentiate y by three types of measures indicating either violent, property, or other crimes. Hence, we estimate β1 for the total effect of prison sentences on recidivism and for violent, property, and other crimes separately.

The first step prior to the IV analysis is testing the underlying assumptions of the model, in our case the random assignment of cases to judges and the variation of judges in sentencing preference.Footnote 10 A randomization test in which each observed covariate was regressed on the set of dummy variables for the assigned judges confirmed that the punitivity of a judge is indeed largely uncorrelated with the defendant and case characteristics that could affect recidivism, which implies that assignment of cases to judges seems to be as good as random (see Table 10 in Appendix). Nevertheless, we control for these observables in all instrumental variable models. Figure 3 in the Appendix further shows that there is a widespread in a judge’s tendency to incarcerate, with probabilities of imprisonment ranging between 0 and 1.

The second step prior to the IV analysis focuses on the exclusion restriction, and on the actual relevance of the instrument using F-tests over the first stages of the IV models. The assumption of instrument exogeneity means that recidivism may only be influenced by the sentence handed down by the court. We consider that our approach complies with this assumption because we could not identify other mechanisms through which the random assignment of a judge may affect reoffending other than through the imposed sentence (also see Wermink et al., 2023). The instrument is sufficiently strong as the F-statistic (F = 1223.60) belonging to the excluded instrument is well over the recently renewed rule-of-thumb of F > 104.7 for sufficiently strong instruments by Lee et al., (2020). This means that our instrument complies with the “relevance” assumption.

Results

The causal effect of short-term prison sentences on recidivism

In Table 2, we present the estimation results for β1 in Eq. 8, which is an important input for the framework of calculating the price of retribution in Eq. 6. We separate β1 by total crimes, property, violence, and other types of crimes. Furthermore, we separate β1 by a range of 1, 3, and 5 years in which recidivism can have taken place. Additionally, we show the mean absolute recidivism after community service (qc, i.e., control mean) and prison (qp, i.e., complier mean).

For the sum of crimes, we find that, compared to a community service order, a short-term prison sanction leads to an average of 0.80 additional registered crimes in the year following the sanction. This effect increases to 1.13 considering 3 years after the sanction and 1.12 considering 5 years after the sanction. Hence, our results suggest that in the Netherlands, short-term prison sentences lead to significantly more recidivism than community service orders. These estimates are robust to a large variety of heterogeneity checks, including LIML estimators and monotonicity assumptions (see Wermink et al. (2023) for an elaborate overview of tests and robustness checks using the same data and method).

The results for the sum of crimes are consistent when we only consider property crimes. For property crimes, we find that, compared to a community service order, a prison sanction leads to an average of 0.56 more crimes in the year after the sanction. This effect increases to 0.79 considering three years after the sanction and 0.98 considering 5 years after the sanction. For crimes other than property and violent crime, we find that a prison sanction increases recidivism by 0.12 on average in the year after the sanction compared to a community service order. This increases to 0.19 considering three years after the sanction and 0.11 considering 5 years after the sanction. For violent crimes, we find no significant difference in recidivism between prison sentences and community service orders. Most likely, this is a result of the nature of violent crimes, which are generally considered to be governed by less rational decisions than property crimes (Felson, 2009). Our results suggest that the effect on the total number of crimes is mainly driven by property crimes and, to a lesser extent by, violent crimes.Footnote 11Footnote 12

Parameters of sanctions and recidivism

In Table 3, we present the values of the key parameters of Eq. 6 regarding Dp (i.e., average days of imprisonment), qp (i.e., average number of recidivism after imprisonment), Vp (i.e., total sanctions), and m (i.e., factor to translate days of prison sanction to days of community service sanction). In addition to our WODC data, we need one external source to complete Table 3 and the total number of sanctions per year in our framework. Vink, (2020, Table 6.9) provides data on short-term prison sanctions (up to 6 months). Our WODC data provide information on the share of short-term sanctions related to property crime, violence, and other crimes in 2012. Combining these sources, Table 3 provides information on the number of short-term prison sanctions for different types of crime in 2012.

In our baseline scenario, scenario 1, we further take into account the direct costs associated with imprisonment and community service orders. The direct costs of imprisonment and community service orders per sanction are taken from the financial report of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Justice and Security (MvJV., 2018). In the first place, a judgment leads to fixed costs. The execution of a judgment requires that participants in the criminal justice system receive the information they need to enforce the sentence in the right form and on time. The coordinating role is performed by the Central Judicial Collection Agency (Centraal Justitieel Incassobureau (CJIB)). This agency is an agency of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. The budget of the agency depends on the price of services and the number of services supplied to the Ministry. The price of the coordination of prison sanctions (66.97) is substantially higher than the price of the coordination of community service sanctions (34.75) in 2012.Footnote 13 In the second place, a judgment leads to variable costs. The daily costs of prison sentences are based on calculations from the Custodial Institutions Agency (Dienst Justitiële Inrichtingen (DJI)), which report 259 euros per day for imprisonment.Footnote 14 The daily costs of a community service order are priced at 72.56 euros per day.Footnote 15 These costs involve the direct costs of the sentence related to personnel, goods, and services per day of the sentence.

Compared to our baseline scenario, we add reintegration costs to our analysis in scenario 2. Following De Koning et al., (2016), who take 2012 as a year of analysis, we assume that reintegration is only necessary for those with a prison sentence. Those with a community service order are assumed to be sufficiently connected with society during their sentence such that they do not need a reintegration trajectory. De Koning et al., (2016) calculate the costs of two trajectories: (1) a simpler and cheaper trajectory and (2) a more complicated and more expensive trajectory.Footnote 16 We use these costs in scenario 2a (cheap alternative) and scenario 2b (expensive alternative). The cheap alternative costs 2247 euros per prisoner per year (De Koning et al., 2016). The expensive alternative costs 5271 euros (De Koning et al., 2016). We convert these costs to the daily costs of a prison sentence and assume that the costs increase linearly with days spent in incarceration. Therefore, we add 2247/365 = 6.16 euros and 5271/365 = 14.44 euros to Cp in scenarios 2a and 2b, respectively. We argue that Scenario 2b is not very likely to hold for our subsample of crimes with a maximum prison sentence of six months.

Compared to scenario 2, we add social insurance costs to our analysis in scenario 3. Ramakers et al., (2014) and Verweij et al., (2022) show that those who receive a prison sentence often face a hard time finding a paid job after their release from prison. More specifically, Verweij et al., (2022) show that about 56% of ex-prisoners receive social insurance benefits in the first 3 years following release. Only about 16% report paid employment. As the mean length of the prison sanction these individuals received was 145 and its median length was 46 days, the percentages reported by Verweij et al., (2022) appear to hold for short prison sentences of up to 6 months that we selected in our study. The corresponding author of the Verweij et al., (2022) study indeed confirmed that the vast majority (82%) of the ex-prisoners included in their study were sentenced to prison sentences of up to 6 months. Those with a community service order are assumed to be less scarred during their sentence, such that they do not need a period of social insurance after completing their sentence. Following De Koning et al., (2016), we assume that those who have completed their prison sentence and cannot find a job receive social assistance benefits. This means they receive a gross income of 1336.42 per month for every month they are not working (welfare benefits as of 1 January 2012).Footnote 17 We present different scenarios for different unemployment durations after incarceration. In scenario 3a, we assume that the average time between completing a prison sentence and finding work is three months. In scenarios 3b and 3c, we assume that this is one year and three years, respectively. In Scenario 3a, we add 3*1336.42 = 4009.26 to the fixed costs of prison sentences Kp. In scenario 3b, we add 12*1336.42 = 16,037.04 to the fixed costs of prison sentences. In scenario 3c, we assume a time discount rate of 2% in order to discount future years to the costs of one year and add 16,037.04 +(16,037.04/1.02)+(16,037.04/(1.02^2)) = 47,173.93 to the fixed costs of prison sentences.

We do not take into account any costs involved with uncompleted community services in any of our scenarios. In principle, every hour of community service that is not provided by the offender is converted into four hours of incarceration. In practice, less than one in every five cases of community service remains unfinished (Van der Heide et al., 2004). However, in most cases, the remaining hours are not converted into incarceration, as the judge may find this punishment disproportional. Neither do we take into account any positive effects of community services in our scenarios, as the extent to which offenders provide a productive task to society is arguable. In many cases, they provide a productive task, but this comes at the cost of other regular workers (who are close to receiving the minimum wage), such as municipal landscapers and kitchen employees in nursing homes.

Table 4 shows an interesting pattern in light of our framework for pricing retribution. Assuming m = 1, scenario 1 shows that \(\frac{\left({D}_p\times {C}_p+{K}_p\right)}{\left(m\times {D}_p\times {C}_c+{K}_c\right)}\sim\)5.75, i.e., the costs of prison sentences are about five times as high as those of community service orders without taking into account the differential effect on recidivism. Therefore, short-term prison sentences should lead to substantial reductions in recidivism (β1 < 0) for the price of retribution to be close to zero (Pr~0).

Simulated price of retribution

In this section, we use all aforementioned parameters and plug these into Eq. 6 to calculate the price of retribution. In Table 5, we present the differential costs of short-term imprisonment and community service orders for the baseline scenario. We report the results for total crime as well as deconstructions of property, violence, and other crimes. The table shows the different parameters assumed based on descriptive statistics (Vp, qp, Dp), estimation results (β1), and external sources (m, Kp, Cp, Kc, Cc,). We present the outcome of the simulation by Pr, which is the difference between the total costs of community service orders and short-term imprisonment, and Pr/Vp, which is the difference between total costs of community service orders and short-term imprisonment by a number of crimes.

According to our framework for pricing retribution, we can interpret these outcomes as the total price of retribution and the total price of retribution per crime, respectively. Therefore, using our baseline scenario, we conclude that Dutch society is willing to pay close to 400 million euros per year for retribution. To interpret the size of this amount: 400 million euros per year is about a third of the total budget of the Custodial Institutions Agency in 2012. For another comparison, this is 21,424 euros per sanctioned offense per year. To make this result a bit less abstract, we translate it into an amount that is implicitly paid by the taxpayer. With about 9 million taxpayers in the Netherlands (T = 9 million), our results imply that each taxpayer pays about 45 euros per year for retribution.Footnote 18

Since both conversion rates and costs are often subject to discussion, we present the sensitivity of our estimated price of retribution (y-axis) for a range of conversion keys (x-axis) and the relative daily costs of community service to prison sentences (z-axis) in Fig. 2. Figure 2 shows that for any reasonable values of the conversion keys and relative daily costs, we find a positive price of retribution. Only in the extreme case of a conversion key equal to 1 and the daily costs of community services being about 1.6 times higher than the daily costs of prison sentences do we find a non-positive price of retribution.

There is some heterogeneity in the price of retribution among types of crimes, although they all point in the same direction. Dutch society is willing to pay about 13,500 euros per property crime per year. This is about 10,000 euros for violent crimes and about 15,500 euros for other types of crimes. In our framework, the heterogeneity between types of crimes largely stems from differences in the average recidivism rate per crime (qp) as well as differences in increased recidivism per crime following short-term prison sentences (β1). Heterogeneity in the average length of imprisonment (Dp) is relatively small, although the average sentence length for other crimes is relatively long, especially compared to that for violent crimes.

Scenario analysis

In this section, we present the simulation exercises for the different scenarios presented in Table 4. In scenario 2, we add additional costs to the daily costs of prison sanctions by arguing that each day of incarceration is associated with reintegration costs. In scenario 2a (Table 6), we assume that the costs of the reintegration trajectory are about half the costs of the reintegration trajectory in scenario 2b (Table 6), thereby following the cost estimates of reintegration by De Koning et al., (2016). In Tables 6 and 7, we show that adding these reintegration costs increases the price of retribution, but the simulated price is in the same order of magnitude as our baseline simulated price in scenario 1. In scenarios 2a and 2b, we simulate a price of retribution that is about 46 and 48 euros per taxpayer per year in the Netherlands, respectively.

In scenario 3, we add additional costs to scenario 2a by adding costs per sanction of prison sanctions, arguing that incarceration is associated with additional costs of social insurance benefits. In particular, social assistance benefits are due to difficulties in finding a job after imprisonment, thereby following the cost estimates of reintegration by De Koning et al., (2016). In scenario 3a (Table 6), we assume that there is an average of 3 months between ending a prison sentence and finding a paid job. In scenario 3b (Table 6) and scenario 3c (Table 6), we assume that this is 1 year and 3 years, respectively. In Table 6, we show that adding these social insurance costs substantially increases the price of retribution compared to our baseline simulated price in scenario 1. In scenario 3a, we simulate a price of retribution that is about 64 euros per taxpayer per year in the Netherlands. This is about 118 and 259 euros in scenarios 3b and 3c, respectively.

Presenting the different scenarios in this section is indicative of our previously described pattern: adding costs beyond the direct costs of prison sentences and community service orders increases the price of retribution. In our worst-case scenario, the price of retribution is about 5.5 times higher than in our baseline estimate. We expect the true price per taxpayer per year to be somewhere in the range of 45–259 euros.

Sensitivity analysis

Although we have just established that our baseline scenario is likely to be a lower bound for the price of retribution, it is interesting to see how vulnerable this lower bound is to statistical probabilities. Therefore, we present the statistical lower and upper bounds of our baseline scenario in this section. To calculate the statistical lower bound of our simulated price in Table 7, we take the lower bounds of the parameters shown in Table 3 based on the standard deviations of the parameters. Hence, we take the lower bounds of qp, β1, and Dp. In Table 7 (upper half), we show that the associated simulated price of retribution for this statistical lower bound is about 41 euros per taxpayer per year. Similarly, we simulate the statistical upper bound of the baseline scenario in Table 7 (lower half) and find a price of 48 euros per taxpayer per year. These results suggest that our price of 45 is relatively precisely estimated in the baseline scenario and is unlikely to be driven by statistical anomalies.

So far, we have assumed that β1 measures the effect of a sentence on the average number of registered crimes in the subsequent year. However, recidivism after a prison sentence and a community service order may continue to differ for much longer periods. To take this into account, we estimated the effect of sentencing on average recidivism 3 and 5 years after the sentence. Recidivism patterns for 3 and 5 years after receiving a sentence are very similar to those found during the first year. In Table 8, we show how our simulated price of retribution changes by using the estimates for 3 and 5 years. Since recidivism is logically higher after 3 years than after 1 and 5 years than after 3 years, we observed slightly higher prices of retribution. However, with about 69 and 86 euros per taxpayer per year in the upper and lower halves of Table 8, respectively, while higher, simulated prices are in the same order of size as our simulated baseline price in Table 5. Therefore, we conclude that our baseline simulations are not vulnerable to extending the time frame to estimate β1.

Decomposing the price of retribution: costs versus recidivism

In Table 9, we present a simulation exercise of the price of retribution with the costs assumed in scenario 1, but we assume that there is no differential effect of short-term prison sentences and community service orders on recidivism, i.e., β1 = 0. The results indicate that, even in the case of no differential effects on recidivism, the price of retribution is about 350 million euros per year. In the case where we are willing to assume that the daily costs of community service orders are the same as for prison sentences in the baseline scenario, our simulations price retribution at about 200 million euros per year.

Conversely, keeping everything else constant, we would need a β1~ − 5.5 for the price of retribution to be non-positive (Pr ≤ 0) in the baseline scenario. This means that short-term prison sentences lead to an average of at least 5.5 fewer registered crimes in the year following the sanction relative to community service orders. Though a relatively small number of studies find negative effects of imprisonment on recidivism in settings that focus on rehabilitative services, our results are in line with most prior international literature that tends to show a criminogenic or null effect of imprisonment (Loeffler & Nagin, 2022).

To conclude, based on these simulation exercises, we can safely assume that the price of retribution is positive and that it is unlikely to be driven by the estimates of β1.

Conclusion and discussion

This study is the first-ever attempt to attach a price to retribution. To do so, we developed a framework in which administrative data on recidivism can be used to identify society’s willingness to pay for retribution. Using Dutch administrative data on all sentences in 2012 and recidivism in subsequent years and estimating the causal effects of sanctioning in an Instrumental Variable framework, we find that short-term prison sentences lead to more recidivism than community service orders. Additionally, we find that the daily costs of imprisonment from the moment of the judges’ verdict are at least 3 times higher than the daily costs of community services. According to our framework, the total price paid for retribution in Dutch society is about 400 million euros per year. This is about 21,000 euros per crime per year and about 45 euros per taxpayer per year. Despite the fact that prison sentences are more expensive than community service orders and that community service orders are more effective in reducing recidivism, society pays this price for short-term prison sentences to exist.

Additional analyses show that the price of retribution is largely driven by property crimes, as the costs of property crimes form the highest share of the total costs of crimes. Our simulated price in the baseline scenario is relatively precisely estimated and is not driven by any statistical uncertainty or choice for the number of years after the sentence taken into account to find effects on recidivism. However, our framework does indicate that our baseline scenario is most likely a lower bound on the price of retribution, and our analysis finds an interesting pattern: adding indirect costs to the analysis increases the price of retribution because (1) community service orders are unlikely to be more costly than prison sentences, and (2) short-term prison sentences lead to more recidivism than community service orders. Given our different scenarios, the price of retribution in the Netherlands is likely somewhere in the range of 45–259 euros per taxpayer per year.

There is another reason why the price of retribution can be expected to be higher. Since prison sanctions lead to an increase in recidivism, there will also be an increase in the number of victims. More generally, an increase in recidivism leads to an increase in the cost of crime. Including these costs of crime would be a natural extension of our analysis.

Our study reveals the willingness to pay for retribution as implied by judicial choices and shows variation in the willingness to pay per offense type. An important caveat is the current study’s sole focus on special deterrence. To the extent that converting all short-term prison sentences to community service orders impacts the general deterrent effect of sanctioning, such that potential offenders are less deterred by community service than they are by short-term imprisonment, the conversion of all short-term prison sentences to community service orders may result in an increase in the overall crime level and, with it, increased costs to society. In this case, the price paid for retribution as currently defined would be an overestimation as the crime-reducing effect of imprisonment would be underestimated.Footnote 19 Although the current analysis does not allow us to directly measure potential differences in general deterrence between short-term prison sentences and community service orders, what we can do is estimate the effects of different general deterrence ratios between these two sentence types on the price of retribution. Equation 6 now assumes one prison sentence corresponds to one community service order—assuming a conversion rate of 1. Under a conversion rate of 2—assuming the general deterrent effect of community service orders is half that of short-term imprisonment—the lower boundary estimate for the price of retribution is still around 35 euros per taxpayer per year. Given prior research on general deterrence, however, a conversion rate of 2 seems unrealistically high (Nagin, 2013). In addition, the incapacitation effect of short-term prison sentences may influence the overall crime level in society because it removes the opportunity to commit crimes for the duration of the prison sentence. However, prior work shows that the incapacitation effects of short-term prison sentences in the Netherlands are negligible (Wermink et al., 2023).

In the end, the price of retribution is paid by the taxpayer. When we are willing to assume that retribution is an important factor in the court’s decision for short-term imprisonment, the question arises whether the price paid by society deviates from what taxpayers would actually be willing to pay for retribution. After all, in a democratic system, policy decisions only indirectly reflect the wishes of the population. To the extent that judicial decisions do not fully reflect citizens’ preferences, the willingness to pay measured in this study merely reflects judicial preferences. Future research on the actual willingness of citizens to pay for retribution is therefore crucial, and information about increased recidivism after prison sanctions should be provided to respondents as the price of retribution largely consists of the costs that repeat crime entails. Will citizens be willing to pay more for prison sanctions, even if this type of sanction ultimately results in more victims?

Political decision-making is a complex process in which, in addition to calculating rationality, moral and emotional considerations play a role. With our research, we hope to contribute to the political discussion about the use of short-term imprisonment as a response to crime in the Netherlands and elsewhere, by showing that moral and emotional considerations also have a (rational) price tag. Our framework allows us to estimate how high the price tag of retribution is. The question of whether this price tag is perhaps too high is a subject for further social discussion.

Data Availability

Data Availability Restrictions apply to the access of the data that support the findings of this study as these data can only be reused if permission has been granted by the Research and Documentation Centre of the Netherlands Ministry of Justice and Security (WODC). The WODC only grants data access to institutions, services and organizations that are located in countries that fall under the scope of the GDPR (the European Economic Area) or to which an adequacy decision of the European Commission applies. The authors are willing to assist. All code necessary to reproduce tables and figures in this paper will be provided.

Notes

WODC, (2008) argues that general deterrence highly depends on the probability of being caught. However, this probability is fairly small in the Netherlands (Van Velthoven, 2002). Recent empirical evidence shows that increasing this probability causes people to increase their perceived risk of sanctions (Terpstra et al., 2020).

This seems to be an issue in Jones and Weatherburn, (2011), especially as the analysis is based on a telephone interview with 1885 (taxpaying) respondents.

Specifically, Becker (1968, p. 181) formulated the following social loss function: L = D(O) + C(p, O) + bfpO. The term D(O) is the net damage to society from O offences. The term C(p, O) represents the total costs of apprehension and conviction. These costs depend on the probability of apprehension (p) and the number of offenses (O). The term bfpO represents the social loss from punishments. In this, bf is the loss per offence punished (f is the punishment per offence for those convicted and b is a coefficient greater than 1 if the punishments takes the form of imprisonment) and pO is the number of offences punished. Optimal law enforcement effectively amounts to the choice of p, f, b that minimizes L.

Note that this implies that we assume that all future offenses will be responded to by imprisonment. Likewise, in Eq. 2, we assume that all future offenses will be followed by community service. While these are rather strong assumptions, previous work on imprisonment in the Netherlands does suggest that prior prison sanctions substantially increase the likelihood of a future prison sanction even after controlling for legal characteristics (e.g., offense type and severity of the case) and extralegal characteristics (Wermink et al., 2015). The influence of a prior prison sanction is found to exceed the effects of virtually all legal characteristics and socio-demographics featured prominently in prior work, including gender and national origin.

The miscellaneous “other” category, for instance, includes: public order offences, traffic offences, and violations of the Weapons and Ammunition Act and the Opium Act.

In the dataset, there is a hierarchy used for the final sentencing decision. If there are combinations, the sentence higher in the hierarchy is selected. The hierarchy from more severe to less severe used by the WODC is the following: unconditional prison sentence, community service, conditional or suspended prison sentence, fines, and lastly other categories such as acquittals and dispositions. From this, we select unconditional prison sentences because these are the most severe and allow for analyzing “the price of retribution.” Unconditional prison sentences may be imposed in combination with other sanctions lower in the hierarchy, except for community service orders, because they serve as the comparison group in our study. In line with Mears et al. (2015), we chose community service orders as the comparison group to define a clear counterfactual scenario (the sanction that otherwise would have occurred).

Estimation results are robust to using a probit instead of a linear probability model in the first stage (not reported here, but for prove of the robustness of methods we refer to Wermink et al., 2023).

To be able to interpret the 2SLS estimates as the local treatment effect (LATE) monotonicity has to be assumed. Monotonicity implies that there are no individuals sentenced to imprisonment by judges that prefer noncustodial sanctions that would not have been sentenced to imprisonment by judges that prefer custodial sanctions, and vice versa. We tested for monotonicity as recommended by Mueller-Smith, (2015). Based on the outcomes of these tests, we conclude that monotonic issues are minor in the current data. Outcomes of the monotonicity tests are available from the authors upon request.

Additional OLS regression analyses were conducted for all outcome measures (total, property, violent, and other crimes) using a 5-year follow-up period. The results show that the imprisonment estimates are positive and significant for each outcome. The main difference with our IV estimates is that the impact of imprisonment on violent crimes is no longer non-significant but positive and significant. This increases confidence that our 2SLS estimates exhibit less bias than the OLS estimates. Finding criminogenic OLS and criminogenic or null 2SLS results is common in the current IV literature (Loeffler & Nagin, 2022).

Note that when estimating the price of retribution, we assume that the local average treatment effect (LATE) estimated by our IV models approximates the average treatment effect (ATE) in the entire population. This assumption is valid only when the proportion of non-compliers—those undergoing a different type of treatment than originally assigned—is low. As far as we can deduct from the available data, all those sentenced to short-term imprisonment did actually undergo imprisonment. Those sentenced to a community service order could, however, end up being imprisoned, for instance, when they fail to meet the conditions of their community service order. The percentage of failed community service orders in the Netherlands, however, is low—in 2012, 86% of community sentences were completed successfully (Kalidien, 2013), and those failing their community service order do not always end up in prison. Additional analyses using the probability of short-term imprisonment (i.e., the propensity score) furthermore show that the region of common support is almost 100% as for almost every value of the propensity score, there are individuals who received short-term prison sanctions but also individuals who received a non-custodial sanction. Consequently, there are no combinations of observed variables that lead to a certain sanction type. Hence, we feel confident in assuming that the LATE approximates the ATE in our case.

Table 10.3.14 in MvJV, (2018).

Table 10.3.6 in MvJV, (2018).

Ruiter et al., (2011) estimate the daily costs of prison sentences at 230 euros per day and community service orders at 65 euros per day in 2010. Hence, the daily costs of community service orders were approximately a third of the daily costs of a prison sentence in 2010. We assume that the daily price of a community service order in 2012 was the price increase in prison sentences from 2011 to 2012 * 65 = (259/232) * 65 = 72.56.

See Table 5.4 in De Koning et al., (2016). Cost trajectories mainly differ due to the use of personnel in the execution of the reintegration trajectories.

For people to receive social assistance benefits, they have to comply by the rules for active job search registered and monitored by the Dutch Work Agency (UWV).

Taking more recent costs and V’s from 2017 and assuming that q’s and β1’s are still valid in 2017, it shows that the total price of retribution is slightly smaller but still close to 400 million euros per year. For comparison, the total costs of the Custodial Institutions Agency (DJI) is about 2.3 billion euros in 2018, meaning that the price of retribution is about a sixth of the total budget of the DJI: https://www.rijksbegroting.nl/2020/voorbereiding/begroting,kst264845_23.html. Also note that in our calculation, we assume that all short detentions are replaced by equivalent community service. When calculating the price of retribution, we assume that those sentenced to prison once will be sentenced to prison again in the event of repeat offenses. To the extent that prison inmates are sentenced to community service on a repeat conviction, we overestimate the extent and actual costs of retaliation under the current policy. To put our findings into perspective, we also estimated the price of retribution under the assumption that the costs of imprisonment and community service are equal ((m x Dp x Cc +Kc) / (Dp x Cp + Kp) = 1). In that case, the price of retribution is entirely determined by the difference in observed recidivism after short-term imprisonment and community service (and the type of punishment for recidivism is no longer relevant). The price of retribution is then lower, but still positive, at 180 million euros per year.

This scenario would assume the direction of the general deterrent effect of short-term imprisonment to be the opposite of its special deterrent effect.

References

Abrams, D. S. (2012). The imprisoner’s dilemma: A cost-benefit approach to incarceration. Iowa Law Review, 98, 905–970.

Aebi, M. F., Berger-Kolopp, L., Burkhardt, C., & Tiago, M. M. (2019). Prisons in Europe 2005-2015 – Volume 1: Country profiles. Council of Europe.

Andersen, L. H. (2019). Using a natural experiment to measure the impact of swifter punishment on criminal recidivism. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 16, 289–298.

Anderson, D. (1999). The aggregate burden of crime. The Journal of Law and Economics, 42(2), 611–642.

Angrist, J. D. (2006). Instrumental variables methods in experimental criminological research: What, why and how. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2, 23–44.

Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 979–1014.

Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (2001). Instrumental variables and the search for identification: From supply and demand to natural experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 69–85.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

Baker, T., Cleary, H. M. D., Pickett, J. T., & Gertz, M. G. (2013). Crime salience and public willingness to pay for child saving and juvenile punishment. Crime & Delinquency, 62(5), 645–668.

Bales, W. D., & Piquero, A. R. (2012). Assessing the impact of imprisonment on recidivism. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 8, 71–101.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Bhuller, M., Dahl, G. B., Loken, K. V., & Mogstad, M. (2020). Incarceration, recidivism, and employment. Journal of Political Economy, 128(4), 1269–1324.

Bishop, K. C., & Murphy, A. D. (2011). Estimating the willingness to pay to avoid violent crime: A dynamic approach. American Economic Review, 101(3), 625–629.

Brand, S., & Price, R. (2000). The economic and social costs of crime. MPRA Working Paper #74968.

Brenig, M., & Proeger, T. (2018). Putting a price tag on security: Subjective well-being and willingness-to-pay for crime reduction in Europe. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 145–166.

Bushway, S. D., & Apel, R. J. (2010). Instrumental variables in criminology and criminal justice. In I. A. Piquero & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative criminology (pp. 595–612). Springer.

Chao, J. C., & Swanson, N. R. (2005). Consistent estimation with a large number of weak instruments. Econometrica, 73(5), 1673–1692.

Cohen, M. A. (2005). The Costs of Crime and Justice. Routledge.

Cohen, M. A. (2015). Willingness to pay to reduce white-collar and corporate crime. Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, 6(2), 305–324.

Cohen, M. A., Rust, R. T., Steen, S., & Tidd, S. T. (2004). Willingness to pay from crime control programs. Criminology, 42(1), 89–110.

Dahl, G. B., Kostol, A. R., & Mogstad, M. (2014). Family welfare cultures. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129, 1711–1752.

Davies, N. M., Von Hinke Kessler Scholder, S., Farbmacher, H., Burgess, S., Windmeijer, F., & Davey Smith, G. (2014). The many weak instruments problem and Mendelian randomization. Statistics in Medicine, 34(3), 454–468.

De Koning, J., Gravesteijn, J., De Hek, P., & De Vries, D. (2016). Kosten en Baten van Maatschappelijke (re-)integratie van Volwassen en Jeugdige (ex-) Gedetineerden [Costs and Benefits of Societal (re-)integration among Adult and Juvenile (ex-)prisoners]. SEOR.

Dobbie, W., Goldin, J., & Yang, C. (2018). The effects of pre-trial detention on conviction, future crime, and employment: Evidence from randomly assigned judges. American Economic Review, 108(2), 201–240.

Dolan, P., Loomes, G., Peasgood, T., & Tsuchiya, A. (2005). Estimating the intangible victim costs of violent crime. British Journal of Criminology, 45(6), 958–976.

Durlauf, S. N., & Nagin, D. S. (2011). Imprisonment and crime: Can both be reduced? Criminology & Public Policy, 10, 13–54.

Ehrlich, I. (1982). The optimum enforcement of laws and the concept of justice: A positive analysis. International Review of Law and Economics, 2, 3–27.

Eren, O., & Mocan, N. (2021). Juvenile punishment, high school graduation, and adult crime: Evidence from idiosyncratic judge harshness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 103, 34–47.

Ertefaie, A., Nguyen, A., Harding, D. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Yang, W. (2018). The instrumental variables analysis with censored data in the presence of many weak instruments: Application to the effect of being sentenced to prison on time to employment. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 12(4), 2647–2673.

Felson, R. B. (2009). Is violence natural, unnatural, or rational? The British Journal of Sociology, 60(3), 577–585.

Gibbons, S. (2004). The costs of urban property crime. The Economic Journal, 114(499), F441–F463.

Gifford, B. (2019). Prison crime and the economics of incarceration. Stanford Law Review, 71, 71–135.

Greenberg, D. F. (1990). The cost-benefit analysis of imprisonment. Social Justice, 4(42), 49–75.

Hansen, C., & Kozbur, D. (2014). Instrumental variables estimation with many weak instruments using regularized JIVE. Journal of Econometrics, 182(2), 290–308.

Harding, D. J., Morenoff, J. D., Nguyen, A. P., & Bushway, S. D. (2017). Short- and long-term effects of imprisonment on future felony convictions and prison admissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(42), 11103–11108.

Harding, D. J., Morenoff, J. D., Nguyen, A. P., Bushway, S. D., & Binswanger, I. A. (2019). A natural experiment study of the effects of imprisonment on violence in the community. Nature Human Behaviour, 3, 671–677.

Haynes, P., & Larsen, C. R. (1984). Financial consequences of incarceration and alternatives: Burglary. Crime & Delinquency, 30(4), 529–550.

Henrichson, C., & Delaney, R. (2012). The price of prisons: What incarceration costs taxpayers. Vera Institute of Justice.

Hjalmarsson, R., & Lindquist, M. J. (2022). The health effects of prison. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(4), 234–270.

Johnson, B. D. (2006). The multilevel context of criminal sentencing: Integrating judge- and county-level influences. Criminology, 44(2), 259–298.

Jones, C. G. A., & Weatherburn, D. J. (2011). Willingness to pay for rehabilitation versus punishment to reduce adult and juvenile crime. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 46(1), 9–27.

Jonson, C. L. (2010). The impact of imprisonment on reoffending: A meta-analysis. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Cincinnati.

Kalidien, S. N. (2013). Tenuitvoerlegging van sancties [Execution of sanctions]. In: S. N. Kalidien & N. E. de Heer-de Lange, Criminaliteit en rechtshandhaving 2012. pp. 153-178. : Boom Uitgevers

Kling, J. R. (2006). Incarceration length, employment, and earnings. American Economic Review, 96(3), 863–876.

Lappi-Seppala, T. (2019). Community sanctions as substitutes to imprisonment in the Nordic countries. Law and Contemporary Problems, 82(1), 17–50.

Lee, D. S., McCrary, J., Moreira, M. J., & Porter, J. R. (2020). Valid t-ratio inference for IV. NBER Working Papers Series, No. 29124.

Linckens, P., & De Looff, J. (2013). Gevangeniswezen in Getal [The Prison System in Numbers]. Custodial Institutions Agency.

Loeffler, C. E. (2013). Does imprisonment alter the life course? Evidence on crime and employment from a natural experiment. Criminology, 51(1), 137–166.

Loeffler, C. E., & Nagin, D. S. (2022). The impact of incarceration on recidivism. Annual Review of Criminology, 5, 133–152.

Loughran, T. A., Mulvey, E. P., Schubert, C. A., Fagan, J., Piquero, A. R., & Losoya, S. H. (2009). Estimating a dose-response relationship between length of stay and future recidivism in serious juvenile offenders. Criminology, 47, 699–740.

Lynch, A. K., & Rasmussen, D. W. (2001). Measuring the impact of crime on house prices. Applied Economics, 33(15), 1981–1989.

McLaughlin, M., Pettus-Davis, C., Brown, D., Veeh, C., & Renn, T. (2016). The economic burden of incarceration in the U.S. In Concordance Institute for Advancing Social Justice. Working Paper No. CI072016.

Meade, B., Steiner, B., Makarios, M., & Travis, L. (2012). Estimating a dose-response relationship between time-served in prison and recidivism. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 50, 525–550.

Mears, D. P., Cochran, J. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2015). Incarceration heterogeneity and its implications for assessing the effectiveness of imprisonment on recidivism. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 26, 691–712.

Mears, D. P., Cochran, J. C., Bales, W. D., & Bhati, A. S. (2016). Recidivism and time served in prison. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 106(1), 83–124.

Mueller-Smith, M. (2015). The criminal and labor market impacts of incarceration. Unpublished Working Paper.

MvJV. (2018). Jaarverslag en slotwet Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid 2018. Tweede Kamer 35 200 VI, nr. 1, tabel 10.3.12.

Nagin, D. S. (2013). Deterrence: A review of the evidence by a criminologist for economists. Annual Review of Economics, 5, 83–105.

Nagin, D. S., Cullen, C. T., & Jonson, C. L. (2009). Imprisonment and reoffending. Crime and Justice, 38(1), 115–200.

Nagin, D. S., Piquero, A. R., Scott, E. S., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Public preferences for rehabilitation versus incarceration of juvenile offenders: Evidence from a contingent valuation survey. Criminology & Public Policy, 5(4), 627–651.

Nauta, B., Moolenaar, D. E. G. & Van Tulder, F. P. (2011). Kosten van Criminaliteit [Costs of Crime]. In S. N. Kalidien, N. E. de Heer-de Lange & M. M. van Rosmalen (Eds.), Criminaliteit en Rechtshandhaving. 2010 (pp. 241-270). : Boom Juridische uitgevers

Nieuwbeerta, P., Nagin, D. S., & Blokland, A. A. J. (2009). Assessing the impact of first-time imprisonment on offenders’ subsequent criminal career development: A matched samples comparison. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 227–257.

Owens, E. G. (2009). More time, less crime? Estimating the incapacitative effect of sentence enhancements. Journal of Law and Economics, 52, 551–579.

Petrich, D. M., Pratt, T. C., Jonson, C. L., & Cullen, F. T. (2021). Custodial sanctions and reoffending: a meta-analytic review. Crime and Justice, 50, 353–424.

Ramakers, A., Apel, R., Nieuwbeerta, P., Dirkzwager, A., & van Wilsem, J. (2014). Imprisonment length hand post-prison employment prospects. Criminology, 52(3), 399–427.

RSJ – The council for the administration of criminal justice and protection of juveniles (2021). Korte detenties nader bekeken [A closer look on short-term imprisonment]. The Hague: RSJ.

Ruiter, S., Tolsma, J., de Hoon, M., Elffers, H., & van der Laan, P. (2011). De Burger als Rechter: Een Onderzoek naar Geprefereerde Sancties voor Misdrijven in Nederland [Citizens as Judges: A Study about Preferred Punishments for Crimes in the Netherlands]. Boom Lemma.

Rydberg, J., & Clark, J. (2016). Variation in the incarceration length-recidivism dose-response relationship. Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 118–128.

Sloan, J., & Miller, J. (1990). Just deserts, the severity of punishment and judicial sentencing decisions. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 4(1), 19–38.

Smith, P., Gendreau, C., & Goggin, C. (2002). The effects of prison sentences and intermediate sanctions on recidivism: General effects and individual differences. (User Report 2002-01). Public Safety Canada.

Snodgrass, G. M., Blokland, A. A. J., Haviland, A., Nieuwbeerta, P., & Nagin, D. S. (2011). Does the time cause the crime? An examination of the relationship between time served and reoffending in the Netherlands. Criminology, 49, 1149–1194.

Stam, M. S., Wermink, H. T., Blokland, A. A. J., & Been, J. (2023 (forthcoming, accepted for publication in 2023).). The effects of imprisonment length on recidivism: A judge stringency instrumental variable approach. Journal of Experimental Criminology.

Sweeten, G., & Apel, R. J. (2007). Incapacitation: Revisiting an old question with a new method and new data. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 23, 303–326.

Terpstra, B. L., Van Velthoven, B. C. J., & Van Wijck, P. W. (2020). Do intensified police controls change perceptions of apprehension probability: A field experiment. Crime & Delinquency, 66(8), 1115–1136.

Tonry, M. (2011). Less imprisonment is no doubt a good thing: More policing is not. Criminology & Public Policy, 10, 137–152.

Van der Heide, W., Wartna, B. S. J., & Blom, M. (2004). Tenuitvoerlegging van sancties [Execution of punishments]. In A. T. J. Eggen & W. van der Heide (Eds.), Criminaliteit en Rechtshandhaving (pp. 173–210). Boom Juridische Uitgevers).

Van Velthoven, B. C. J. (2002). Pakkansen, strafmaten, en het “martmodel” van Ehrlich. Economische invalshoeken voor het criminaliteitsonderzoek [Apprehension probability, punishment, and Ehrlich’s market for offenses. Economic angels for crime research]. Justitiële Verkenningen, 28(4), 45–62.

Van Velthoven, B. C. J. (2008). Kosten-batenanalyse van criminaliteitsbeleid [Cost-benefit analysis of crime policy]. Proces, Tijdschrift Voor Strafrechtspleging, 87(4), 108–120.

Van Velthoven, B. C. J., & Van Wijck, P. W. (2016). Becker’s theory on crime and punishment, a useful guide for law enforcement policy in The Netherlands? Recht der Werkelijkheid, 37(1), 6–31.

Van Wingerden, S., Van Wilsem, J., & Johnson, B. D. (2016). Offender’s personal circumstances and punishment: Toward a more refined model for the explanation of sentencing disparities. Justice Quarterly, 33(1), 100–133.

Verweij, S., Weijters, G., Wermink, H., & Blokland, A. (2022). Post-release source of income and convictions of adult ex-prisoners. Crime & Delinquency, 6-7, 1035–1068.

Villettaz, P., Gillieron, G., & Killias, M. (2015). The effects on re-offending of custodial vs. non-custodial sanctions: An updated systematic review of the state of knowledge. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 1–92.

Vink, M. E. (2020). Berechting [Sentencing]. In R. F. Meijer, S. W. van den Braak, & R. Choenni (Eds.), Criminaliteit en Rechtshandhaving 2019: Ontwikkelingen en Samenhangen (pp. 65–72). Research and Documentation Centre.

Waldfogel, J. (1993). Criminal sentences as endogenous taxes: Are they “just” or “efficient”? The Journal of Law and Economics, 36(1), 139–151.

Weisburd, D., Farrington, D. P., & Gill, C. (2017). What works in crime prevention and rehabilitation. An assessment of systematic reviews. Criminology & Public Policy, 16(2), 415–449.

Wermink, H., Apel, R., Nieuwbeerta, P., & Blokland, A. A. J. (2013). The incapacitation effects of first-time imprisonment: A matched samples comparison. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 29, 579–600.