Abstract

Proportions of specialist and generalist primary parasitoids have been described by the resource breadth and the trade-off hypothesis. These alternative hypotheses predict either decreased or increased, respectively, parasitism rate of shared aphid species by specialist parasitoids. We tested both hypotheses and the confounding effects of landscape structure and agricultural intensification (AI) using extensive samplings of aphids and their parasitoids in Polish agricultural landscapes. Abundances, species composition of aphids, primary parasitoids, and parasitism rate of aphids by specialists and generalist parasitoids were analysed. Contrary to our expectations we found equally decreased parasitism rates by both types of primary parasitoids at higher aphid densities and thus proportion of specialists to generalists did not change with increasing host density. In line with the resource breadth hypothesis, specialist parasitoids had always lower abundances and parasitism rates than generalist parasitoids. Landscape diversity and agricultural intensification did not influence the host-parasitoid population dynamics. We speculate that these contrasting results could be caused by the additional density effects of secondary parasitoids. We conclude that simplistic two-trophic-level population models are not able to fully describe the complex dynamics of trophic networks. We also argue that agricultural intensification has lower effects on abundance and effectiveness of parasitoids than predicted by respective predator–prey models and empirical studies performed in controlled and artificial conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aphids are important pests in agriculture and much effort has been made to reduce their negative impact on crop plants (Hassan 1994; Landis et al. 2000). One of the most diverse group of aphid enemies are primary parasitoids that have a high potential in limiting aphid numbers, especially under controlled conditions e.g. greenhouses (Yang et al. 2014). Many ecological factors have been shown to influence primary parasitoid effectiveness (e.g. predation, secondary parasitism, alternative prey). The host range of parasitoids (the degree of parasitoid host specialisation) may also affect parasitization rate (Monmany and Aide 2009; Rossinelli and Bacher 2015). For instance, at low densities of the target host (e.g. cereal aphids) the ability of generalist parasitoids to switch to other hosts might strongly reduce the parasitism rate of target aphid species allowing aphid populations to recover (Chow and Mackauer 1991).

Within primary parasitoids various degrees of host specialization can be found (Stilmant et al. 2008). Respective proportions of specialist and generalist parasitoids within a focal community have been described by two alternative hypotheses. Both hypotheses assume differences between generalists and specialists in efficiency of using shared hosts. According to the trade-off hypothesis the high performance of parasitoids on specific hosts comes to the cost of narrow host range (Poulin 1998). Therefore abundances and parasitism rates by specialist parasitoids will be higher in comparison to their generalist counterparts. The alternative resource breadth hypothesis assumes that generalists and specialists are equally efficient in exploiting shared hosts resulting in a predominance of generalist parasitoids due to the larger prey base that generalists can utilize (Gaston et al. 1997; Krasnov et al. 2004). However, recent tests of these contrasting hypotheses returned mixed results without giving a strong and cogent evidence in favour of one of these two views (Jaenike 1990; Scheirs et al. 2005; Agosta and Klemens 2009; Forister et al. 2012). In this respect, it does matter what type of parasitoid is the most effective in reducing pest numbers and which environmental factors favour this process.

Different proportions of specialist and generalist parasitoids stem from differences in the mode of parasitoid searching (Campan and Benrey 2004) and their ability to compete for the host (Brodeur and Rosenheim 2000; Sampaio et al. 2006). Apart from these factors, the landscape structure and agricultural intensification (AI) also trigger differences in abundance of these two types of parasitoids (Tscharntke et al. 2007).

High agricultural intensification is associated with environmental disturbances. It makes agro-ecosystems less stable in comparison to natural and semi-natural habitats (Kennedy and Storer 2000). According to quantitative modelling of Richmond et al. (2005), generalists prevail and contribute most to ecosystem functioning in unstable environments, while specialists excel under constant or slowly changing environmental conditions. Therefore the ratio of specialists to generalists may depend on the degree of ecosystem stability and may be different in various types of habitats. Hence, various regimes of agricultural intensification and landscape structure are potentially important and should be considered in testing of both hypotheses.

Field studies investigating the proportion of specialists to generalists are scarce (Straub et al. 2011; Rossinelli and Bacher 2015), and studies examining these two hypotheses in relation to landscape structure and AI basically do not exist.

In biocontrol programmes it is important to know which of these two types of parasitoids cause higher mortality on aphids and consequently performs better. The present work tries to answer the question, whether aphid abundance, landscape structure, and agricultural intensification affected the abundance of specialist and generalist primary parasitoids. Based on the resource breadth hypothesis (equal efficiency in exploiting cereal aphids) we predicted that generalist parasitoids will prevail and exert the stronger pressure on less intensively managed fields (less disturbed ecosystems) located in complex landscape, since such a landscape maintains larger populations of parasitoids with broader host range.

Materials and methods

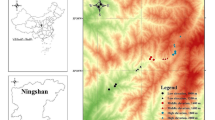

In 2008 we studied four fields with high agricultural intensification (high AI fields) and four with low AI. These fields were selected from a regional pool according to number of management events (e.g. tillage), cereal yield, and the percentage of surrounding arable land. In 2009 we studied five different fields of each category, but subsequently ruled out one field from the analyses due to inappropriate management. In consequence eight and nine winter wheat [Triticum aestivum (L.)] fields in Central Poland were surveyed in 2008 and 2009, respectively (study design of the AGRIPOPES project, see Geiger et al. 2010a, b). Fields were above one hectare in area and located at least one kilometre apart. They were distributed within a square of about 30 × 30 km to minimize differences in the regional species pools among study farms.

As recommended by Thies et al. (2003), we quantified landscape structure as the proportion of individual habitat types (grassland, forest, arable land) within a circle of 500 m radius (area of about 78.5 ha included) going from the middle of each study field. The Shannon index of habitat types was calculated as a metric of landscape diversity. Abundances and species composition of aphids were estimated from five sampling points per field along a transect going from the edge to the centre of each field. At each point we sampled 20 randomly chosen winter wheat shoots resulting in a total of 100 tillers per field during each visit.

Abundances and species composition of aphid parasitoids were assessed from aphid mummies, collected at random in the whole field during 2-h surveys. Mummies were taken to the laboratory and kept individually in small vials. After emergence, adult parasitoids were identified to species level. We did not consider secondary parasitoids. Samples of both living aphids and those mummified by primary parasitoids were collected three and nine times in the season in 2008 and 2009, respectively, leading to a total of 105 samples.

We estimated the parasitism rate λ by specialist and generalist parasitoids as the ratio of the numbers of a given type of mummies (aphids mummified by specialist or generalist parasitoids) to the all mummies (aphids parasitized by both types of primary parasitoids) collected during 2-h surveys during each visit plus living aphids that were recorded on 100 tillers of winter wheat. We used the difference \(\Delta {\uplambda} = {\uplambda }_{\text{specialists}} {-}{\uplambda}_{\text{generalists}}\) to quantify the proportions of both types. Additionally we checked the preferences of specialist and generalist primary parasitoids for particular aphid species, counting aphids parasitized by the focal parasitoid species. We tested for differences between the expected and the observed counts in different parasitoid categories (specialists vs generalists, and Aphidius vs Ephedrus vs Praon) using the χ2-statistic.

We related abundances of generalist and specialist parasitoids and their aphid parasitism rate (dependent variables) to agricultural intensification (categorical predictor), and landscape diversity, percentage of arable land, aphids abundances, and the parasitism rate by the opposite category parasitoids (specialists and generalists) (metric predictors) using general linear modelling with Gaussian error structure and log-link functions. Due to the non-linear relationships squared parasitism rates entered the models as additional covariate. To assess the strength of influence of the predictors on the dependent variables we used partial η2 values. Errors refer always to standard errors.

Results

In total, we found three species of aphids (Sitobion avenae (F.), Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) and Metopolophium dirhodum (Walker) with S. avenae being most frequent (Table 1). Aphids were parasitized by two species of specialist parasitoids: Aphidius rhopalosiphi (DeStefani-Perez) and A. uzbekistanicus (Luzhetski), and four species of generalists: Ephedrus plagiator (Nees), Praon abjectum (Haliday), P. volucre (Haliday), Aphidius ervi (Haliday). We also recorded Aphelinus flavipes (Forster) and Aphidius avenae Haliday. However, these species were difficult to categorize in regard to host range (generalist vs. specialist). Aphidius avenae is considered as moderate specialist, while the genus of Aphelinus consists of several complexes of cryptic species, which were reported as generalist (Stiling 2004) or as specialist species (Ortiz-Martínez et al. 2013). Therefore we ruled them out from analyses, especially that they were recorded in very low numbers (Table 1).

Neither landscape diversity nor percentage of arable land did detectably influence parasitism rates by specialist and generalist parasitoids (Table 2) and their abundances (equivalent results as for parasitism rates, not shown). Total abundances of aphids and parasitoids were highly variable during the two study years (Table 1). Aphid abundances did not differ significantly (P(t1,104) > 0.15) between the low (163 ± 24 ind.) and the high AI sites (111 ± 18 ind.). Similarly, the proportions of specialist and generalist parasitoids as quantified by Δλ did not significantly depend on AI (Fig. 1a; Table 2). AI alone explained only about 3% of the variability in Δλ, and at most 3% of variability in parasitism rates (Table 2). Lower AI consistently increased abundances of generalist and specialist parasitoids (Fig. 1a). At higher AI, parasitism rates of specialists increased and those of generalists decreased (Fig. 1b), making total parasitism rate of aphids λ independent of agricultural intensification (λ(high AI) = 0.69; λ(low AI) = 0.67). Rates of parasitism by generalist species were highest at intermediate parasitism by the specialist species (Fig. 2). Further, the proportions of both groups changed in dependence on host number (Fig. 3). Parasitism rates of aphids by specialists (Fig. 3a) and generalists (Fig. 3b) at both levels of agricultural intensification decreased with increasing host density. Proportions of both groups were highly variable at low and less variable at high aphid abundances (Fig. 3c). These effects were observed at both, high and low levels of AI. We did not find significant differences between both types of parasitoids in host association (3 × 2 contingency table P(χ2) > 0.1). Generally, the generalist species of parasitoids reached on all plots higher abundances (Table 1; Fig. 1a) and parasitism rates (Fig. 1b) than their specialist counterparts.

The average abundances (a) and parasitism rates of aphids λ (b) by specialist (dark grey bars) and generalist parasitoids (light grey bars), and the difference between both type of parasitoids Δλ (white bars) on plots with high and low agricultural intensification (high AI, low AI). Error bars denote one standard error

Parasitism rate of aphids λ by specialist (a) and generalist parasitoids (b) decreased with increasing aphid abundance (total counts). The respective difference Δλ between both type of parasitoids (c) was independent of aphid abundance. Open dots low AI, black dots high AI. Regression lines in a and b drawn from all data points

Discussion

Based on the general assumption that the type of land use differently influences host aphid density and their parasitism by specialist and generalist parasitoids (Monmany and Aide 2009), we predicted an association of generalist parasitoids with low AI and the more complex landscape. In line with the resource breadth hypothesis, we expected that less disturbed cereal fields and a diverse environment will promote generalist parasitoids and enhance the respective parasitism rate. Our results corroborates this hypothesis showing that generalists were always more numerous and had a higher aphid parasitism rate than specialists. However, we did not find any effect of environmental factors on parasitism rates. Similar results were obtained by Macfadyen et al. (2009), who also found a prevalence of the generalist parasitoid Ephedrus plagiator, irrespective of agricultural intensification. Gagic et al. (2012, 2014) reported generalists to be associated with low AI early in the season while later being abundant regardless of the AI regime.

We did not confirm the assumed relationship between the performance of generalist/specialist parasitoids and the rate of environmental fluctuations. Richmond et al. (2005) showed that generalists tolerate suboptimal conditions and prevail under highly variable environment. Associating the environmental conditions with host availability, we expected that specialist parasitoids should benefit from situations when there is access to one specific host (cereal aphids) that is abundant, whereas generalists should have an advantage when such host is rare or unpredictable (Rossinelli and Bacher 2015). Instead, we found decreased parasitism by both types of primary parasitoids with increasing aphid numbers possibly reflecting a “spreading of mortality risk” strategy of primary parasitoids attacked by secondary parasitoids (Fig. 3a, b). If the death rate of primary parasitoid larvae increases with the clutch size of living and parasitized aphids due to secondary parasitism, it pays for primary parasitoids to escape from such a colony rather than to increase the number of ovipositions (Mackauer and Völkl 1993). This decrease was independent of host specialization resulting in equal proportions of parasitism by specialist and generalist parasitoids at higher densities of cereal aphids (Fig. 3c). In this respect, Thies et al. (2005) pointed to trade-offs between higher aphid mortality due to parasitism and simultaneously increased colonization in complex landscapes resulting in decreased parasitism rates at high host density. Consequently, we argue that a higher parasitism rate of aphids should be expected at lower aphid density.

In general, the AI and landscape effects we tested for, were weak and at the lower level of statistical detectability. However, we could not assess possible long-term effects on parasitoid community structure and abundance. In fact, we did not find strong evidence that agricultural intensification has a negative impact on biological control potential of parasitoids. Parasitism rates recorded on intensively and extensively managed fields were similar and not linked to our metrics of landscape complexity (Table 2). This is in opposite to results of some authors, who showed that the deterioration of biocontrol potential were primarily mediated by agricultural practices such as pesticide application (Jonsson et al. (2012) and simplification of landscape (Macfadyen et al. 2009; Thies et al. 2011; Veres et al. 2013; Rusch et al. 2016). In this respect, the important factor in the evaluation of landscape effects might be initial complexity of landscape structure. Jonsson et al. (2010) and Tscharntke et al. (2012) favoured bell shaped parasitism rate-complexity relationships with the consequence that we should expect detectable parasitoid biocontrol effects only at intermediate levels of landscape complexity. We note that agricultural intensification in Poland was comparably low during the last 20 years. Even the most intensively managed fields were less exploited than average fields in western Europe (Wretenberg 2006). Hence, the weak effects of AI and landscape structure on the observed pattern of parasitism rate might be due to the overall low degrees of AI and respective effects might have been masked by the lack of sufficiently homogenous conditions (Macfadyen et al. 2009; Jonsson et al. 2015). Probably for the same reasons Menalled et al. (2003) did not find any relationship between landscape structure and species richness.

These contradictions may also result from the complexity of ecological processes that involve multiple biotic-abiotic and biotic–biotic interactions, which are difficult to examine and control in the field. In this respect Schellhorn et al. (2015) stressed the importance of the spatial and temporal variability of aphids and their natural enemies for the final outcome of pest control. Host availability in previous seasons determine the rate of aphid parasitism in subsequent years (Holt and Lawton 1994). Our study also revealed significant year by year differences in community structure and dominance of aphids and their primary parasitoids (Tables 1, 2). Such a variability has already been reported by many authors without identification of the underlying factors (Askew and Shaw 1986; Jones and Weinzierl 1997; Thies et al. 2005; Gagic et al. 2014). Possibly the observed high species turnover is linked to environmental stress connected with AI (Warwick and Clarke 1993; Carpenter and Brock 2006) secondary parasitoid impact (Sullivan 1972), or climatic factors affecting the immigration, colonization, and development of aphids and their parasitoids (Pankanin-Franczyk and Ceryngier 1995; Pankanin-Franczyk and Sobota 1998; Langer and Hance 2004; Schellhorn et al. 2014; Hawro et al. 2015).

A major shortcoming of many studies relating land use intensification and community composition regards the temporal dynamics as these studies used short-term data only. This reduced number of replicates makes the identification of the factors and processes that trigger the long-term dynamics of aphid and parasitoid population structure challenging (Chaplin-Kramer et al. 2011). Future investigations on aphid–parasitoid dynamics in agricultural landscapes need to involve longer time scales (Menalled et al. 2003; Gagic et al. 2012, 2014).

References

Agosta SJ, Klemens JA (2009) Resource specialization in a phytophagous insect: no evidence for genetically based performance trade-offs across hosts in the field or laboratory. J Evol Biol 22:907–912

Askew RR, Shaw MR (1986) Parasitoid communities: their size, structure, and development. In: Waage J, Greathead D (eds) Insect parasitoid. Academic Press, London, pp 225–264

Brodeur J, Rosenheim JA (2000) Intraguild interactions in aphid parasitoids. Entomol Exp Appl 97:93–108

Campan E, Benrey B (2004) Behavior and performance of a specialist and a generalist parasitoid of bruchids on wild and cultivated beans. Biol Control 30:220–228

Carpenter SR, Brock WA (2006) Rising variance: a leading indicator of ecological transition. Ecol Lett 9:311–318

Chaplin-Kramer R, O’Rourke ME, Blitzer EJ, Kremen C (2011) A meta-analysis of crop pest and natural enemy response to landscape complexity. Ecol Lett 14:922–932

Chow A, Mackauer M (1991) Patterns of host selection by four species of aphidiid (Hymenoptera) parasitoids: influence of host switching. Ecol Entomol 16:403–410

Forister ML, Dyer LA, Singer M, Stireman JO III, Lill JT (2012) Revisiting the evolution of ecological specialization, with emphasis on insect–plant interactions. Ecology 93:981–991

Gagic V, Hänke S, Thies C, Scherber C, Tomanović Ž, Tscharntke T (2012) Agricultural intensification and cereal aphid–parasitoid–hyperparasitoid food webs: network complexity, temporal variability and parasitism rates. Oecologia 170:1099–1109

Gagic V, Hänke S, Thies C, Tscharntke T (2014) Community variability in aphid parasitoids versus predators in response to agricultural intensification. Insect Conserv Diver 7:103–112

Gaston KJ, Blackburn TM, Lawton JH (1997) Interspecific abundance–range size relationships: an appraisal of mechanisms. J Anim Ecol 66:579–601

Geiger F, Bengtsson J, Berendse F, Weisser WW, Emmerson M, Morales MB, Ceryngier P, Liira J, Tscharntke T, Winqvist C, Eggers S, Bommarco R, Part T, Bretagnolle V, Plantegenest M, Clement LW, Dennis C, Palmer C, Onate JJ, Guerrero I, Hawro V, Aavik T, Thies C, Flohre A, Hanke S, Fischer C, Inchausti P (2010a) Persistent negative effects of pesticides on biodiversity and biological control potential on European farmland. Basic Appl Ecol 11:97–105

Geiger F, de Snoo GR, Berendse F, Guerrero I, Morales MB, Onate JJ, Eggers S, Part T, Bommarco R, Bengtsson J, Clement LW, Weisser WW, Olszewski A, Ceryngier P, Hawro V, Inchausti P, Fischer C, Flohre A, Thies C, Tscharntke T (2010b) Landscape composition influences farm management effects on farmland birds in winter: a panEuropean approach. Agric Ecosyst Environ 139:571–577

Hassan SA (1994) Strategies to select Trichogramma species for use in biological control. In: Wajnberg E, Hassan SA (eds) Biological control with egg parasitoids. CAB International, Berkshire, pp 55–71

Hawro V, Ceryngier P, Tscharntke T, Thies C, Gagic V, Bengtsson J, Bommarco R, Winqvist C, Weisser WW, Clement LW, Japoshvili G, Ulrich W (2015) Landscape complexity is not a major trigger of species richness and food web structure of European cereal aphid parasitoids. Biocontrol 60:451–461

Holt RA, Lawton JH (1994) The ecological consequences of shared natural enemies. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 25:495–520

Jaenike J (1990) Host specialization in phytophagous insects. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 21:243–273

Jones CJ, Weinzierl RA (1997) Geographical and temporal variation in pteromalid (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) parasitism of stable fly and house fly (Diptera: Muscidae) pupae collected from Illinois cattle feedlots. Environ Entomol 206:421–432

Jonsson M, Wratten SD, Landis DA, Tompkins JML, Cullen R (2010) Habitat manipulation to mitigate the impacts of invasive arthropod pests. Biol Invasions 12:2933–2945

Jonsson M, Buckley HL, Case BS, Wratten SD, Hale RJ, Didham RK (2012) Agricultural intensification drives landscape-context effects on host–parasitoid interactions in agroecosystems. J Appl Ecol 49:706–714

Jonsson M, Straub CS, Didham RK, Buckley HL, Case BS, Hale RJ, Claudio Gratton C, Wratten SD (2015) Experimental evidence that the effectiveness of conservation biological control depends on landscape complexity. J Appl Ecol 52:1274–1282

Kennedy GG, Storer NP (2000) Life systems of polyphagous arthropod pests in temporally unstable cropping systems. Annu Rev Entomol 45:467–493

Krasnov BR, Poulin R, Shenbrot GI, Mouillot D, Khokhlova IS (2004) Ectoparasitic “Jacks-of-All-Trades”: relationship between abundance and host specificity in fleas (Siphonaptera) parasitic on small mammals. Am Nat 164:506–516

Landis DA, Wratten SD, Gurr GM (2000) Habitat management to conserve natural enemies of arthropod pests in agriculture. Annu Rev Entomol 45:175–201

Langer A, Hance T (2004) Enhancing parasitism of wheat aphids through apparent competition: a tool for biological control. Agric Ecosyst Environ 102:205–212

Macfadyen S, Gibson R, Raso L, Sint D, Traugott M, Memmott J (2009) Parasitoid control of aphids in organic and conventional farming systems. Agric Ecosyst Environ 133:14–18

Mackauer M, Völkl W (1993) Regulation of aphid populations by aphidiid wasps: does parasitoid foraging behaviour or hyperparasitism limit impact? Oecologia 94:339–350

Menalled FD, Costamagna AC, Marino PC, Landis DA (2003) Temporal variation in the response of parasitoids to agricultural landscape structure. Agric Ecosyst Environ 96:29–35

Monmany AC, Aide TM (2009) Landscape and community drivers of herbivore parasitism in Northwest Argentina. Agric Ecosyst Environ 134:148–152

Ortiz-Martínez SA, Ramírez CC, Lavandero B (2013) Host acceptance behavior of the parasitoid Aphelinus mali and its aphid-host Eriosoma lanigerum on two Rosaceae plant species. J Pest Sci 86:659–667

Pankanin-Franczyk M, Ceryngier P (1995) Cereal aphids, their parasitoids and coccinellids on oats in central Poland. J Appl Entomol 119:107–111

Pankanin-Franczyk M, Sobota G (1998) Relationships between primary and secondary parasitoids of cereal aphids. J Appl Entomol 122:389–395

Poulin R (1998) Large-scale patterns of host use by parasites of freshwater fishes. Ecol Lett 1:118–128

Richmond CE, Breitburg DL, Rose KA (2005) The role of environmental generalist species in ecosystem function. Ecol Model 188:279–295

Rossinelli S, Bacher S (2015) Higher establishment success in specialized parasitoids: support for the existence of trade-offs in the evolution of specialization. Funct Ecol 29:277–284

Rusch A, Chaplin-Kramer R, Gardiner MM, Hawro V, Holland J, Landis D, Thies C, Tscharntke T, Weisser WW, Winqvist C, Woltz M, Bommarco R (2016) Agricultural landscape simplification reduces natural pest control: a quantitative synthesis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 221:198–204

Sampaio M, Bueno VHP, Soglia MCM, De Conti BF, Rodrigues SMM (2006) Larval competition between Aphidius colemani and Lysiphlebus testaceipes after multiparasitism of the host Aphis gossypii. Bull Insectol 59:147–151

Scheirs J, Jordaens K, De Bruyn L (2005) Have genetic trade-offs in host use been overlooked in arthropods? Evol Ecol 19:551–561

Schellhorn NA, Bianchi FJJA, Hsu CL (2014) Movement of entomophagous arthropods in agricultural landscapes: links to pest suppression. Annu Rev Entomol 59:559–581

Schellhorn NA, Parry HR, Macfadyen S, Wang Y, Zalucki MP (2015) Connecting scales: achieving in-field pest control from area wide and landscape ecology studies. Insect Sci 22:35–51

Stiling P (2004) Biological control not on target. Biol Invasions 6:151–159

Stilmant D, Van Bellinghen C, Hance T, Boivin G (2008) Host specialization in habitat specialists and generalists. Oecologia 156:905–912

Straub CS, Ives AR, Gratton C (2011) Evidence for a trade-off between host-range breadth and host-use efficiency in aphid parasitoids. Am Nat 177:389–395

Sullivan DJ (1972) Comparative behavior and competition between two aphid hyperparasites: Alloxysta victrix and Asaphes californicus (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae; Pteromalidae). Environ Entomol 1:234–244

Thies C, Dewenter IS, Tscharntke T (2003) Effects of landscape context on herbivory and parasitism at different spatial scales. Oikos 101:18–25

Thies C, Roschewitz I, Tscharntke T (2005) The landscape context of cereal aphid–parasitoid interactions. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 272:203–210

Thies C, Haenke S, Scherber C, Bengtsson J, Bommarco R, Clement LW, Ceryngier P, Dennis C, Emmerson M, Gagic V, Hawro V, Liira J, Weisser WW, Winqvist C, Tscharntke T (2011) The relationship between agricultural intensification and biological control: experimental tests across Europe. Ecol Appl 21:2187–2196

Tscharntke T, Bommarco R, Clough Y, Crist TO, Kleijn D, Rand TA, Tylianakis JM, Van Nouhuys S, Vidal S (2007) Conservation biological control and enemy diversity on a landscape scale. Biol Control 43:294–309

Tscharntke T, Tylianakis JM, Rand TA, Didham RK, Fahrig L, Batary P, Bengtsson J, Clough Y, Crist TO, Dormann CF, Ewers RM, Fründ J, Holt RD, Holzschuh A, Klein AM, Kleijn D, Kremen C, Landis DA, Laurance W, Lindenmayer D, Scherber C, Sodhi N, Steffan-Dewenter I, Thies C, van der Putten WH, Ewers RM (2012) Landscape moderation of biodiversity patterns and processes-eight hypotheses. Biol Rev 87:661–685

Veres A, Petit S, Conord C, Lavigne C (2013) Does landscape composition affect pest abundance and their control by natural enemies? A review. Agric Ecosyst Environ 166:110–117

Warwick RM, Clarke KR (1993) Increased variability as a symptom of stress in marine communities. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 172:215–226

Wretenberg J (2006) The decline of farmland birds in Sweden. Doctoral thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala

Yang NW, Zang LS, Wang S, Guo JY, Xu HX, Zhang F, Wan FH (2014) Biological pest management by predators and parasitoids in the greenhouse vegetables in China. Biol Control 68:92–102

Acknowledgements

The study was part of the AGRIPOPES project (AGRIcultural POlicy-induced landscaPe changes: effects on biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; http://agripopes.net), funded through the European Science Foundation (EUROCORES programme), in collaboration with the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. We would like to thank Željko Tomanowić for helping with identification of some Aphidius individuals. We would like also to express our special thanks to anonymous reviewers for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hawro, V., Ceryngier, P., Kowalska, A. et al. Landscape structure and agricultural intensification are weak predictors of host range and parasitism rate of cereal aphids. Ecol Res 32, 109–115 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-016-1419-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-016-1419-y