Abstract

In recent years, there has been an increasing concern about non-governmental development organisations’ (NGDOs) sustainability especially in countries including Ghana that have transitioned into lower-middle-income status. The effect has been donor withdrawal and funding cuts for NGDOs. This presents opportunities and challenges for NGDOs in their attempt to mobilise alternative funding routes in ensuring their sustainability. Drawing on secondary literature and semi-structured interviews with fifty-seven respondents from national NGDOs, government, donors and corporate organisations, this article documents and expands our understanding of the different typologies of philanthropic institutions in Ghana as potential alternative funding routes for NGDOs. It finds that a weak enabling environment including the absence of a regulatory framework and fiscal incentives for domestic resource mobilisation stands to affect the potential of philanthropic institutions as alternative funding routes for NGDOs’ sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last few years, many developing countries have experienced sustained economic growth by transitioning into lower-middle-income status. On November 5, 2010, Ghana attained the status of a lower-middle-income country (LMIC) after the rebasing of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by sixty-nine per cent. This resulted in a GDP per capita from US $800 to US $1363 (Jerven and Duncan 2012; Moss and Majerowicz 2012; Jerven 2016). Directly associated with Ghana’s attainment of a LMIC status is the creation of a ‘new development aid landscape’ characterised by withdrawal and cuts in donor support for government and non-governmental development organisations (NGDOs).Footnote 1

The implication of this changing aid landscape is that some traditional development partners are in the process of exiting to other strategically important countries. Denmark, for example, scaled up its commercial cooperation while development cooperation was downscaled since 2010 and will exist from all official development assistance (ODA) cooperation by 2020 due to Ghana’s LMIC status (OECD 2016a: 105). Currently, Ghana’s health sector is underfinanced as many development partners like Denmark that have been supporting the sector since 1994 have withdrawn their funding to the sector (DANIDA 2015). The predictability of commitment-based budgeting in 2015 saw a marginal decline, and this affected the level of support given to civil society organisations (CSOs) including NGDOs (OECD 2016a). Moreover, in October 2016, the UK joined the European Union to announce its withdrawal of budgetary and programme support for Ghana with wider implications for the activities of NGDOs.Footnote 2 ODA relative to other development flows has declined over the years. For example, net ODA declined from US $2.1 billion to US $1.1 billion between 2009 and 2014 (OECD 2017). Ghana’s attainment of LMIC status changes aid modalities and the onus for providing essential social services therefore lies with the Government of Ghana. The expectation is that Ghana should be able to make significant contributions in fighting its own poverty. Although poverty levels declined by 23.2 percentage points (i.e. from 51.7 to 28.5% between 1991 and 2005), about 24.2% of the population still lives below the absolute poverty line of GH¢1314 in 2012/2013 (GSS 2014). The progress towards poverty reduction is regionalised in character leading to increasing levels of inequality and polarisation across and within regions (Clementi et al. 2016; Abdulai 2017).

For this reason, NGDOs are needed to play significant roles in complementing service delivery in areas such as health care and education to communities where government support is not reachable. This complementary role could help in reducing poverty and hunger and the provision of equitable access to education. For NGDOs to continue to play these crucial roles, there is the need for them to become sustainable in order to continue the provision of needed services to intended beneficiaries. However, the changing aid landscape stands to affect the effectiveness and sustainability of NGDOs in achieving these important roles (Arhin 2016). The effect of this is an increasing agitation among NGDOs about their sustainability especially in an environment where alternative funding is perceived to be limited in scope or non-existent. This is forcing NGDOs to reposition themselves to ensure their sustainability by mobilising alternative resources. However, tapping these resources especially domestic funding base and local constituency has implications for NGDOs’ operations and sustainability.

Against this backdrop, wider discussion of NGDOs sustainability has gained traction in recent years (see Hayman 2016; Hailey and Salway 2016; Fowler 2016a). In Ghana, sustainability is becoming a common word among donors, NGDO employees and development practitioners. For example, donors use sustainability as a criterion for funding projects. At the same time, individual NGDOs and the sector as a whole are called to be sustainable following the withdrawal of donor funding in recent years (Kumi 2016; Arhin 2016). The dwindling donor support and withdrawal raise concern about the sustainability NGDOs who are highly dependent on foreign donors for survival. Informed by the increasing concern for NGDOs’ sustainability, the recent years have seen some commentators arguing for the need for alternative routes (Hailey and Salway 2016). While the discussion of alternative routes to NGDOs’ sustainability is emerging, little attention has been paid to African gifting and philanthropic institutions as potential alternative funding routes.Footnote 3 Despite the increasing attention given to African philanthropy in the literature in recent years (e.g. Moyo and Ramsamy 2014; Aina and Moyo 2013; Fowler 2016c), empirical research on African philanthropy at the country-level in Ghana remains limited. To this end, the central research question of this article is: what are the different typologies of philanthropic institutions existing in Ghana that serve as alternative funding routes for NGDOs?

This article focuses specifically on documenting and analysing the Ghanaian philanthropic landscape given that discussion of African philanthropy is under researched. Doing so will help in understanding whether there is a distinctive Ghanaian philanthropy or generic philanthropy that have some Ghanaian characteristics in it. Moreover, relatively little research has been conducted on the role of African gifting as alternative funding for NGDOs at the sub-regional and national level. For this reason, there is lack of information and understanding into the peculiarities of philanthropic activities. This article seeks to fill the existing knowledge gap in order to understand the dynamics, typologies of philanthropic institutions, their complexities, and the challenges that stand to affect philanthropic institutions as alternative funding routes for Ghanaian NGDOs. Knowledge on these issues has broader academic, development and policy implications for Ghana and other developing countries in general.

The article is organised as follows. Section two presents an overview of philanthropic aid inflows and their funding for NGDOs. This is followed by a discussion of the research methodology in section three. Section four focuses on the research findings by critically examining the philanthropic landscape in Ghana. This is followed by a discussion of the research findings in section six. The last section concludes.

Philanthropic Institutions’ and Development Finance

The engagement of philanthropic institutions in development is far from new. For example, the Ford Foundation was instrumental in the Green Revolution in agriculture while the Rockefeller Foundation helped in the establishment of the League of Nations Health Organisation and the World Health Organisation (Youde 2013; Nally and Taylor 2015). For this reason, organised philanthropic funding has been a major source of development finance over the years especially for the non-profit industry of which NGDOs are major constituents. According to Development Initiatives (2013:41) in 2011, international giving by private and corporate foundations was about US $1.7 billion and US $8.2 billion, respectively, while partnerships between NGDOs and foundations was estimated at US $3.9 billion. Similarly, the Foundation Centre reports that between 2002 and 2012, United States (US) foundation funding for Africa increased by 400% from US $288.8 million to about US $1.5 billion with the Gates Foundation being the highest contributor (Foundation Centre 2015:5–6).

Interestingly, most of the funding for Africa went to organisations headquartered outside Africa. For example, in 2012, 12 out of the 15 top recipients were located outside (e.g. The World Health Organisation received about US $133.6 million) while just one-quarter of the total funding (US $1.5 billion) went directly to organisations located in Africa. This reflects the wider trend in development finance where a greater proportion of funding is given to Northern-based organisation. It is a demonstration of the increasing resource inequality between Northern and Southern-based organisations which results in a situation of ‘squeezing out’ where Northern-based organisations overshadow their southern counterparts in relation to funding opportunities. Data on philanthropic flows to NGDOs are relatively scant especially in Africa where giving is not properly recorded. Moreover, given the perceived lack of progressive philanthropic culture, the vast literature is quick to downplay the importance of indigenous giving and vertical philanthropy to African NGDOs (see Aina and Moyo 2013). This notwithstanding, philanthropic institutions such as the Ford Foundation, TrustAfrica and the African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF) have been supporting the growth and development of NGDOs in the areas of capacity building and governance for many years. For example, TrustAfrica disbursed grants of about US $20.5 million between 2006 and 2013 (TrustAfrica 2016). Given the recent withdrawal and cuts in external donor funding and support for NGDOs, philanthropic institutions could become alternative source of funding for NGDOs struggling to ensure their survival. For this reason, understanding the scope of the philanthropic landscape in Ghana is crucial for NGDOs’ sustainability. In what follows, I discuss the research methodology.

Methodology

This article is based on primary data and secondary literature. For primary data, qualitative research was adopted because of the need to have an in-depth understanding into how philanthropic institutions could serve as alternative funding routes for NGDOs. Data were collected through in-depth interviews with forty-two national NGDO leaders mainly executive directors and programme managers working in health, education and agriculture sectors in three regions of Ghana (Upper West, Northern and Greater Accra). In addition, fifteen key informant interviews [4 donor agencies (two bilateral and two INGOs), 2 grant-making foundations, 2 corporate foundations and 7 informants with extensive knowledge of the NGDO and government sector in Ghana] were conducted. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews which took place in respondents’ offices. The use of semi-structured interviews provided deeper understanding of how NGDO leaders mobilise resources from the different philanthropic institutions and the requirements for seeking such resources. Data collection took place between August 2015 and July 2016. All interviews were conducted in English and tape-recorded with the consent of respondents. Recorded interviews were transcribed and analysed using NVivo 10. Thematic analysis was used where main themes (parent nodes) and sub-themes (child nodes) emerging from the data were identified. The process of coding was iterative making the data analysis to be recursive rather than a linear approach which involves movements back and forth with the data and the emerging themes. This article also drew on traditional review of scholarly literature on philanthropic institutions specifically through journal articles, books, working and conference papers.

In the next section, I present the research findings and discussion by examining the different typologies of philanthropic institutions in Ghana. This section is divided into two parts. The first explores the typologies of horizontal and vertical philanthropy. A discussion of the research findings and challenges that confronts the potential role of philanthropic institutions and lessons learnt for advancing philanthropy in Ghana are presented in part two.

Key Findings

Ghana’s Philanthropic Landscape

In recent years, Ghana is witnessing a growth in its local philanthropic activities. This is not to suggest that philanthropy is a new practice in the country. Indeed, local philanthropy has been part of the country’s historical context where people give their gifts, labour and time to support one another making indigenous philanthropy to exist over centuries. However, the recent years have seen a growing emphasis on the ‘old and new’ forms of philanthropy in the country. For this reason, Ghana’s philanthropic landscape is more inclusive and large in scope as it contains a mixture of indigenous (horizontal) and institutionalised (vertical) philanthropy. Examples of indigenous philanthropic culture in Ghana include individual donations and religious giving in addition to volunteerism. It is important to mention while recognising that the discussion of African philanthropy is highly contested, the focus of the findings and discussion in this article is to understand the typologies of Ghanaian philanthropy and how NGDOs are mobilising them to support their activities and long-term sustainability.

Individual and Religious Giving

An important aspect of Ghanaian philanthropic landscape relates to individual and religious giving. Twenty-three respondents explained that Ghanaians had a rich culture of giving to support the needy in communities. For example, the Executive Director of a medium-sized NGDO explained:

Looking at the work we do in social protection, we stand tall to make simple appeal for funds to individuals in our project implementing communities. We have individuals who support us with money, foodstuff, used clothing and logistics to help the aged in our society (Interview, 25th April 2016, Tamale)

Another NGDO leader spoke about how his organisation mobilised individual giving to support his organisational activities and programmes by stating that:

Our funding also comes from individuals. Sometimes, we write proposals to wealthy individuals about the problems that exist in our society. So these individuals often give us donations to undertake activities in our communities. Apart from cash, they also give us donations like clothing to give to the needy in the society (Interview, 1st April 2016, Wa).

The above statements suggest that NGDO leaders considered individual giving (in-kind and in-cash) as an important aspect of Ghanaian philanthropic landscape. This indicates that in Ghanaian societies, people tend to see the welfare of their neighbours as their responsibility by showing concern in promoting the wellbeing of others. For this reason, acts of giving, sharing and reciprocal relationships are deeply embedded in Ghanaian social values. Moreover, according to ten respondents, individual giving was largely influenced by the need for social network, reciprocity and mutual assistance where social relations and norms of reciprocity or counter-obligation are valued in society. One Executive Director of an NGDO that supports marginalised and vulnerable women and children explained that individual giving was used as an avenue to mitigate deprivation in society where marginalised people are assisted to become part of the wider society which helps in promoting inclusivity. He stated as follows:

These days, we run the shelter based on donations of individuals. So we put the money in the resource mobilisation fund and then we use it to pay school fees, cater for their feeding and psychological needs and even resettling a client. People give us support because they want us to provide a decent life for the vulnerable (Interview, 3rd March 2016, Accra).

Giving in Ghanaian society was also considered as an initiator and stabiliser of social relationships. For this reason, individual giving was more towards extended family members and neighbours rather than donating directly to an organisation. This was a recurrent theme among respondents. For example, twenty-five respondents explained that individuals preferred giving to friends and family members rather than supporting NGDOs directly as illustrated by the following quotations:

People don’t have that spirit of giving directly to NGOs. And even those who benefit from NGOs’ programme, they don’t have the giving back attitude. It’s quiet difficult because individuals giving directly to NGOs is not part of us. People do not see the need to give to third parties like NGOs.

The lack of perceived philanthropic culture for supporting NGDOs was attributed to the informal nature of giving among Ghanaians. For example, the Fund Raising Manager of a philanthropic institution explained that the nature of giving among Ghanaians was largely informal and unorganised. According to the respondent, individual giving largely took the form of informal institutionalised affinity networks. For this reason, it was difficult for NGDOs to tap into individual donations as part of their domestic resource mobilisation strategies. She stated as follows:

Is not that Ghanaians are not philanthropists who do not give. The issue is that our giving is different. We have not yet organised our giving. So because of that we are perceived as people who do not give. We pay for our cousin’s school fees, support extended family members and the needy but they are not in an organised way. So our giving is informal (Interview, 16th May 2016, Accra).

Interestingly, twenty-eight NGDO respondents explained that they had not made any conscious efforts to quantify the contributions of individual giving to their annual budget. Moreover, these respondents felt that although poverty levels in Ghana had reduced significantly over the years, a number of people were still living in poverty. For this reason, they were more concerned about meeting their immediate needs rather than giving funds to support the activities of NGDOs. A key informant shared this sentiment by stating that:

Concerning individual giving to NGOs, those opportunities are limited. In Ghana, people are earning peanuts and are pre-occupied with their own survival so the idea of benevolence or giving is not there because people don’t have the resources. I don’t see opportunities like individual giving to NGOs in Ghana, maybe in the future but not now (Interview, 18th April 2016, Tamale).

Another important aspect of philanthropy relates to faith-based giving. Religions including Christianity and Islam advocate for individual giving to support the needy in society. For this reason, some Christians are always encouraged to give through annual pledges or by paying tithes where members give 10% of their income to support the church. Informed by this idea of helping the poor and seeking spiritual blessings, some churches in Ghana have established development agencies including the Assemblies of God Relief Agency, the Association of Church-based Development NGDOs and the Wesleyan Aid for Northern Ghana. For the Islamic religion, charity is an outward expression of faith. Through Islamic practices and endowments such as Zakat, Muslims give to support the activities of civil society and the general society. As part of Islamic tenets, individuals are mandated to contribute 2.5% of their annual income to support the needy.

More importantly, respondents explained that individuals perform sadaqa (i.e. voluntary giving). The assumption here is that there is a spiritual blessing attached to giving or helping the poor and needy in society. Islamic philanthropic individuals give to charitable cause through the establishment of foundations. In Ghana, prominent among them include the Imam Hasayn Foundation.

Although some religious institutions in Ghana engage in philanthropic acts, many are more interested in encouraging their congregants to give directly to them. A respondent explained that this phenomenon has led to a situation where ‘people do not see the value in giving beyond faith-based organisations like churches or mosques. They always believe that once you give in the church or the mosque, God will bless you’ (Interview, 12th June 2016, Accra). Another respondent stated as follows: ‘I am a Muslim, I do a lot of charity, I prefer to go to the mosque and give it to the Imam or to support in the building of mosque and getting mats for the mosque’ (Interview, 4th March, 2016, Tamale). This inclination to give to religious bodies rather than supporting the poor and needy was attributed in part to the orientation of many faith-based organisations. A key informant explained in recent years, there is more emphasis on ‘yiedea asempa’-prosperity gospel especially in Charismatic Christian circles. This tends to focus on profits and wealth accumulation by church leaders and their followers rather than supporting the needy congregants or those outside the church as illustrated by the following quotation:

The Ghanaian attitude is not well developed and it has to do with the church teachings or faith-based organisations orientation. It is mostly tilted towards self-gain. They preach give me because I am preaching but not give to your brothers because they are in need. So until we have that attitudinal change, we will still be donating to the church but the impact will not be felt in the communities (Interview, 5th January 2016, Accra).

Volunteerism as Philanthropy

Volunteer support was a crucial resource for twenty-six NGDOs in this study. Twenty NGDO respondents explained that they mobilised both community and international volunteers to undertake their activities. According to respondents, their increasing engagement with volunteers was a way of ensuring their organisational and project sustainability. The withdrawal of donor support and the projectised nature of funding made it difficult for NGDOs to hire and retain experienced staff especially when projects ended. For this reason, many small and medium-sized NGDOs, only a few core staff including administrative directors and project managers were retained in the absence of core funding. By doing so, they relied mostly on the services of volunteers. The support of volunteers was considered as the lifeblood for NGDOs’ organisational and project sustainability. The importance of volunteers was emphasised by the Executive Director of an NGDO who stated as follows:

In the absence of funding, some of the things you would have relied on paid staff, you find a way of diplomatically passing some of those tasks to community members who would do it as voluntary work (Interview, 28th October 2015, Accra).

Another Executive Director added:

Due to the presence of our community surveillance volunteers, even when the NGO is not physically present in the communities, our presence are always felt. When we are not there, the community volunteers still carry on with the advocacy work in their various communities (Interview, 26th March 2016, Tamale).

Despite the important roles played by volunteers, twenty respondents expressed concern about their inability to motivate them which often led to dwindling and limited commitment levels. Thus, volunteer unreliability was a major concern raised by respondents because it affected organisational planning, mission accomplishment in additional to organisational survival. Volunteer unreliability was attributed largely to the absence of core funding and NGDOs’ failure to raise the needed funds for their activities. The challenge of maintaining volunteers was summed up by one Executive Director whose project staff often volunteered at the end of their projects. She maintained that:

You know in Ghana, people don’t volunteer and even if they decide to volunteer, they will ask you to pay money. There are some people who have financial issues and because of that they can’t continue to volunteer with the organisation (Interview, 14th April 2016, Wa).

A common concern raised by thirty-five NGDO respondents was their inability to meet the expectation of potential volunteers. They explained that although volunteers saw their engagement with NGDOs as avenue for getting into the job market, they expected or demanded financial rewards or incentives. The lack of monetary and non-monetary incentive packages served as an important hindrance for most NGDOs in their attempt to engage with volunteers. Respondents explained that volunteering in formal institutions like NGDOs was used as a survival strategy for people especially graduates seeking employment. For this reason, NGDOs who were unable to pay such incentives explained that they avoided having direct engagement with volunteers. The Executive Director of a small NGDO in the health sector explained this as follows:

About fifty-five trained volunteers on our reproductive health programme are currently not on periodic community outreach because when they go, they are entitled to their allowances. Because the funding is project-based, we now don’t have the funds for them because the project has ended. So we don’t engage them on regular basis. This is affecting our impact in the communities and it speaks directly to our own sustainability. When you are project-dependent and you have no funds of your own, your own sustainability is always at stake (Interview, 4th May 2016, Accra).

Respondents explained that in Ghana, people had little understanding about volunteerism and this accounted for the underdevelopment and low level of volunteer engagement among NGDOs. This was also because many NGDOs had no clear-cut policies for engaging the services of volunteers. For this reason, relational incentives for most volunteers were largely absent. For this reason, respondents explained that it calls for more education and awareness creation on how best NGDOs could engage meaningfully with volunteers as potential alternative resource mobilisation route in ensuring their long-term sustainability.

Diaspora Remittances and Foreign Development Philanthropy

Another important source of philanthropic activities relates to remittances. A common concern raised by more than half of respondents was the absence of comprehensive data on remittances towards philanthropic activities. Respondents explained that this was due in part to the diverse nature of the philanthropic sector, the absence of a central government agency to track the inflows of diaspora funding in addition to the non-disclosure of information on remittances especially in-kind donations. A key informant in the NGDO sector explained the difficulty involved in getting information on remittances to NGDO by stating that:

Currently there is no information on remittances to NGOs because they don’t disclose them. Although NGOs are taking advantage of our numbers in the diaspora, we don’t know how much they are getting from them. I think it is also because of the absence of a national regulatory body for the NGO sector (Interview 12th May 2016, Accra).

Notwithstanding the non-disclosure of information, five respondents reported that they had received in-kind and in-cash donations from the diaspora. For example, the Executive Director of an NGDO in the Northern Region explained that his organisation received both financial and non-financial support from Ghanaians based in the UK and the Netherlands as illustrated by the following quotation:

We also have donations from some Ghanaians in Netherlands who sent us some computers and printers. There is another Ghanaian in the UK who has decided to adopt some of the schools we are supporting and sponsor them. She also supports our local initiatives for the aged, the women at the witch camps and the children on our programmes (Interview, 25th November 2015, Tamale).

According to twelve respondents, diaspora philanthropists used their expertise through the provision of skilled personnel and networks in improving upon social development in their communities in areas like health and education. Moreover, they provided access to funding opportunities through recommendations and networks as noted by one respondent ‘a woman in the UK has linked us to some individuals abroad who sometimes support our work but it is not regular’ (Interview 3rd November 2015, Accra). The statement demonstrates the importance of personal contacts and the ad hoc nature of support from the diaspora. A recurrent theme was that although diaspora philanthropy could serve as potential alternative resource mobilisation route, NGDOs had paid little attention to this as part of their funding strategies. For this reason, diaspora philanthropy remains an untapped resource for NGDOs. During interviews, twenty-seven NGDO leaders and key informants raise questions about how to unearth this potential resource. For example, a key informant pointed out that:

Another thing NGOs should do is to take advantage of our numbers in the diaspora. If you look at remittances, there is a huge amount of money that comes through such channel. So NGOs need to ask themselves, how do we create mechanisms and take advantage of the diaspora to contribute to development through their money, technical skills and networks? (Interview, 12th May 2016, Accra).

In recent years, transnationalisation has emerged as an important feature of the Ghanaian philanthropic landscape. Respondents explained that transnationalisation occurs when foreign philanthropists are installed as developmental chiefs and queen mothers especially in traditional rural communities. These individuals are normally given the title of nkosuo hene or nkosuo ohemaa (i.e. development chief/developmental queen mother). These foreign development philanthropists (FDPs) are appointed based on their philanthropic gestures and ability to promote development. Although this philanthropy is vertical, it tends to be fluid in nature. In vertical philanthropy, donors give out of altruistic values without any reciprocity. However, for FDPs, beneficiary communities reciprocate by giving them titles, recognitions and connections in their communities. The phenomena of FDPs in Ghana brings rich empirical evidence of the intersections between horizontal and vertical philanthropy that has been absent in the literature on African philanthropy.

Community Philanthropy

Community philanthropy has gained much prominence in both academic and policy discourses in recent years as more high-net worth and middle-class individuals continue to increase in many developing countries. These individuals are beginning to fund home-grown philanthropic activities. However, two key informants and eleven NGDO leaders explained that in Ghana, the concept of community philanthropy is not well developed as illustrated by the following quotation:

Community-based philanthropy is a very weak area especially in Ghana and West Africa in general. It is stronger in South Africa. I think that for Ghana, it’s an area where there is no policy framework so it doesn’t give the enabling environment for people to develop those kinds of foundations (Interview, 23rd March 2016, Tamale).

Although community philanthropy is not well developed in Ghana, the Akuapem Community Foundation (ACF) is a classic example. ACF serves the people of the Akuapem Traditional Area and beyond. This foundation was established in 2001 with the objective of building an endowment fund to provide grant making and implement projects as well as offering leadership to communities.Footnote 4 Community foundations are funded from many sources including community members, government agencies and corporate organisations. This blurs the definition and meaning of community philanthropy and also. Demonstrates the difficulty involved in translating the western notion of community philanthropy into the Ghanaian context. The definition of community foundation as grant-making public charities is not useful because community foundations in Ghana mobilise resources to perform both grant-making and operating roles. By doing so, they tap into local resources as a way of promoting empowerment by strengthening the voice and participation of citizens. This ensures horizontal accountability because community members are actively engaged in the decision-making processes and management of the foundation.

African Grants-Making Institutions (AGMIs)

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in AGMIs. The rationale for their establishment is to ensure the promotion of indigenous philanthropy in addressing ‘dependency syndrome’ problems underlying Africa’s development experience. In addition, their establishment is on the basis of providing sustainable alternative support to NGDOs highly dependent on donor funding. The assumption is that having institutions with African roots will help in mobilising the needed resources to support NGDOs. Informed by this assumption, many external private foundations (EPFs) advocated for and supported the establishment of these so-called AGMIs making them the creation and pawns of foreign foundations. An example is TrustAfrica established by the Ford Foundation. This notwithstanding, there are others that were created by some Africans through their investment. An example is the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

In Ghana, AGMIs like TrustAfrica provide funding to CSOs including NGDOs (Table 1). Some Ghanaian foundations also support NGDOs. However, a striking observation was that a number of local foundations had turned themselves into ‘quasi-NGDOs’ who implemented projects directly rather than focusing on grants-making. This masks difference in understanding the true nature of foundations operating in the country. The legal status of many Ghanaian foundations seems quite unclear.

It is difficult to separate NGDOs claiming the self-identity of foundations from those providing grants. Foundations in Ghana remain ‘black boxes’ due to the absence of an appropriate organisational typology.

As alluded to above, AGMIs were mainly set up to mobilise domestic resources for development. However, many still rely on foreign donors for funding because of their inability to raise the much-needed domestic resources which presents a sustainability challenge. In an interview with representatives of AGMIs in Ghana, two respondents reported that their endowment funds were not yielding any better returns. For this reason, they were in doubt of their own sustainability due to their inability to mobilise domestic resources. A representative of an AGMI explained their challenges as follows:

We have an endowment fund and this endowment is not growing. The building is part of our endowment fund, we are renting the other building which is also part of the endowment fund but how much does it bring is a year? It’s simply not working. Most of our monies come from the global fund (Interview, 22nd February 2016).

During interview, respondents indicated that they had attempted to mobilise financial and non-financial resources from the private sector in Ghana. This included negotiating with telecommunication companies to use their platforms to raise funds but this has proved futile. Speaking about their inability to mobilise domestic resources, one respondent stated as follows:

In Ghana, we really haven’t been able to raise much funds. We have a few individual donors who every month give us GH₵ 50.00 here and things like that. But apart from that, we haven’t really raised much funds (Interview, 2nd February 2016, Accra).

Respondents indicated their inability to mobilise domestic resources is due in part to the high transaction costs associated with the transfer of funds. They maintain that telecommunication companies make it very difficult for individuals to give towards supporting AGMIs because they are largely motivated by profit. One respondent lamented about the high transaction costs by stating that:

We have approached many corporate organisations, within Ghana but it has been unsuccessful. We approached the telecommunication companies just to make giving easy where they can create short codes for people to transfer money. But what they are charging, at the end of the day, your investment will just go waste. These institutions don’t even make giving pleasant. The whole environment has made it very difficult to mobilise funds within Africa. We have spoken about this on various platforms that African governments should make policies to make giving cheaper but we have not achieved much results (Interview, 15th May 2016, Accra).

Domestic resource mobilisation for AGMIs is limited which compels them to depend heavily on their foreign counterparts for financial resources. This reinforces elements of dependency for which AGMIs were established to address. Moreover, their over reliance on donor funding reduces the number of NGDOs and CSOs that AGMIs could support. One Grants Manager of an AGMI iterated such concern by stating that:

We are just able to meet the demands of about 30-35% of our applicants because we don’t have money. Is an issue of funding. We can’t give what we don’t have. We don’t have independent funds of our own. We also raise money to be able to give grants. Most of our money comes from the global north (Interview, 2nd February 2016 Accra).

The above statement raises questions about the legitimacy of AGMIs dependent on donor funding for their operations. The way local constituents perceive AGMIs served as a major determinant of giving. During interviews, two representatives of AGMIs reported that they had relatively little engagement with their local constituents including the private sector. This indicates the sheer difficulties facing AGMIs in their attempt to mobilise domestic resources. The inability of AGMIs to mobilise domestic resource was also because of their structure of operation. They had adopted western notions of philanthropic giving in their attempt to seek funding which does not fit perfectly into the Ghanaian context. During interviews, a recurrent theme was the neglect of indigenous giving mechanisms as part of their resource mobilisation strategies. Another important factor that limits AGMIs’ ability to mobilise domestic resources was the absence of an enabling environment that allows individuals to make donations. For example, one Fundraising Specialist of an AGMI explained:

There is an absence of a policy framework for giving in Ghana. So it doesn’t give that enabling environment that incentivises people to give to us. So the whole environment has made it very difficult to mobilise funds within Africa or even domestically in Ghana. So the lack of a legal framework or policy environment is one of the major reasons why giving is still the way it is in Ghana (Interview, 16th May 2016, Accra).

Respondents explained that the prevalent political economy within a particular country is a key determining factor for the creation of an enabling environment that encourages giving. In the case of Ghana, it was reported by respondents that the existing taxation laws and other instruments tend to disincentivise individual and corporate giving.

Institutionalised Philanthropic Foundations

Institutionalised foundations remain the biggest constituents of Ghana’s philanthropic landscape with much emphasis on external private foundations (EPFs). This forms part of vertical philanthropy where wealthy individuals and well-endowed institutions give out of altruism to support the ‘poor’ without any expectation of reciprocity. Grant-making organisations mobilise resources from a single source and distribute them to other charitable organisations. EPFs have played important roles in Ghana’s development by supporting national NGDOs. Their funding serves as important lifeblood for the survival of many national NGDOs.

Twelve NGDO respondents reported receiving financial support from EPFs including Open Society Initiative for West Africa, Trull Foundation, New England Biolabs Foundation and Human Dignity Foundation. These EPFs provided bridge funding for short-term and small projects for their organisation. This helps NGDOs to sustain themselves while looking for alternative projects and funds from bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. One respondent emphasised that:

We have some small projects from philanthropic foundations like the New England Biolabs Foundation. Currently we have not received any donor funding but the small project in forestry ensures that we are able to exist as an organisation. They give us one year funding and we have to reapply when it ends (Interview, 29th October 2015, Tamale).

Interestingly, five respondents stressed that many EPFs wanted to maintain their anonymity when funding them. They did not want NGDOs to mention their names in their financial reporting. As a respondent note: ‘In fact, not until now, a foundation that supports us didn’t want anybody to know that they were supporting or funding us. So in our records, we were just putting them as anonymous donors but they provide a lot of money to support our organisation’ (Interview, 23rd March 2016, Tamale). Respondents explained that although funding from EPFs was useful in ensuring their survival especially for NGDOs operating in health and education sectors, the amount of money given was relatively small compared to funding from bilateral and multilateral donors. This notwithstanding, they maintained that given the recent withdrawal and cuts in funding and support from most bilateral and multilateral donors, the support of EPFs cannot be underestimated because they help in addressing the funding gap created by the withdrawal of many development partners.

Corporate Philanthropy

Corporate philanthropy constitutes an important feature of the emerging Ghana’s philanthropic landscape. In recent years, there is a renewed interest in corporate social responsibility (CSR) among companies in Ghana despite the absence of any clear-cut law on CSR.Footnote 5 Corporate giving is a voluntary norm and as part of CSR, multinational companies especially in telecommunication and extractive sectors had established their own corporate foundations to serve as what I call ‘NGDO wing’ implementing developmental projects (Table 2). One representative of a corporate organisation reported that they implemented their projects and programmes independent of NGDOs. He stated as follows:

We implement projects and programmes on our own. We have done over 135 projects across the entire country without passing it through any NGO. So every region that you will go, you will find our footprint in terms of the CSR. Throughout the ten regions of the country, we’ve invested over GH₵22 million (US$5.54 million) (Interview, 2nd June 2016, Accra).

The establishment of corporate foundations was used as a ‘window-dressing strategy’ for enhancing their brand. For this reason, CSR undertaken by corporate foundations was largely business driven as it enhanced corporate image. For this reason, thirty-two respondents suggested that CSR was used as marketing (e.g. product expansion) and communication strategy (e.g. reputational gains) rather than a genuine interest to promote development. This sentiment was shared by a representative from one telecommunication company who stated that:

Having a corporate foundation and engaging in CSR shows that the business is caring and so because of that people would want to patronise your products. But companies won’t come out clearly to say that okay we’re doing CSR because we just want to do good (Interview, 28th March 2016, Accra).

Interestingly, the distinction between corporate philanthropy and CSR is fluid because all activities undertaken by corporate organisations outside their operations are interpreted as corporate philanthropy. The lack of a consistent definition and the identity crisis of corporate philanthropy in Ghana is a reflection that it is in its growth phase. Institutionalised CSR was mainly undertaken by larger multinational organisations rather than local businesses in petty trading in retail and primary production. Although some local businesses provided in-kind and in-cash donations, they were mostly not recognised as CSR but rather an act of philanthropy.

One striking revelation was the relatively little engagement between corporate foundations and NGDOs. In interviews, NGDOs and corporate foundation respondents emphasised that their relationship was weak. In many instances, the relationship was often one-off where corporate organisations support some NGDOs in the form of product donation and staff volunteering rather than providing cash to support NGDOs’ long-term projects. Two corporate respondents reported that they engaged with like-minded NGDOs to promote mutual and beneficial relationships rather than dependency. Twenty NGDO respondents explained that corporate organisations were interested in sponsoring visible projects like building schools that can be ‘branded in their colours’ rather than supporting advocacy programmes and institutional processes and structures’ (Interview, 6th May, 2016). Thus, most corporate organisations were interested in cherry picking their CSR projects in communities which often had relatively little community involvement. Their CSR as reported by NGDO respondents was largely driven by their corporate interest rather than the priority of community members.

The disconnect between corporate foundations and NGDOs was attributed to the structure of corporate foundations which mostly engage in short-term and one-off community interventions. Moreover, corporate foundations, generally do not donate to NGDOs due in part to the absence of legal framework and policies that incentivises them to give to support philanthropic activities. There is no fiscal incentive such as tax exemption, tax deductibility for corporate foundations supporting the NGDO sector.

Discussion

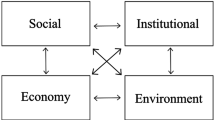

This article aimed at mapping Ghana’s philanthropic landscape by exploring the different forms of philanthropy that exists in the country. It highlights that Ghana’s philanthropic landscape is vast, fluid and dynamic comprising both vertical and horizontal philanthropy. In particular, the findings in this article demonstrate that while many low-income countries that have recently transitioned into lower-middle-income status are experiencing aid reduction and withdrawal of donor funding (e.g. Hayman and Lewis 2017; Pallas and Nguyen 2017), the role of philanthropic institutions in serving as alternative source of resource mobilisation for NGDOs remains somewhat limited. In terms of individual and religious giving, this article highlights that it is often towards family members rather than giving to formal institutions including NGDOs. As the evidence suggests, giving to and through NGDOs and wider CSOs is relatively low. This is influenced by the emphasis on familial obligation and reciprocity. In fact, individuals have a social responsibility to support their family members largely informed by the ideals of future reciprocity to themselves or even their offspring. This reflects an Akan proverb: ‘wohwe obi dehyeƐ yie a na wo nso wo deƐ reyƐ yie’ meaning if you take good care of someone’s royal personage, your royal personage will also prosper (Gyasi-Obeng 1996:531). The above statement points to the interdependency existing between individuals and their communities or family members.

For this reason, individual giving in Ghana and across Africa in general tends to have relational focus usually framed around morality where individuals have a moral responsibility to support their family members. It also reflects the wider communalistic nature of most African society where individuals developed the bound of supporting their family members through their upbringing (Wiredu 2004; Masolo 2004). As Masolo (2004:491) argues, it is the ability of an individual to perform his obligatory responsibilities to family members and community members that gives him or her ‘personhood’. For this reason, individuals prefer to give towards people who are perceived to be closer to them due to communalistic values. In this vein, motivations for giving extend beyond generosity and altruism to include moral obligations. The pressure of meeting customary obligation becomes pronounced especially for individuals with higher social status. Honouring such responsibility enhances individual’s reputation and status. This raises questions about whether individuals give to family members based on genuine philanthropic impulse, social expectation or personal interest. A similar finding of the obligatory nature of giving has been reported in South Africa (Everatt et al. 2005). More importantly, giving helps in addressing inequality in society through wealth distribution where individuals with limited resources are helped by others in their society. Philanthropy is therefore a mechanism for promoting the wellbeing of people within society where the existence of an individual is linked to others (Moyo 2011). This reflects Hyden’s (1983) observation about the economy of affection in most African societies.

While there is an increasing emphasis on the rise of high-net worth and middle-class individuals in Ghana and Africa in general (Moyo 2011; African Grantmakers Network 2013), relatively little is known about their influence on the Ghanaian philanthropic landscape. Thus, the gifting behaviour of the emerging middle class who could serve as private donors is largely under researched. This represents a gap in knowledge and therefore calls for further research into the dynamics of individual giving in Ghana in order to understand the size and scope of the philanthropic sector. In particular, understanding the dynamics associated with high-net worth individuals giving in terms of their giving preference (i.e. through circles or the establishment of individual foundation) would be particularly useful given the sensitivities associated with wealth creation.

Another important aspect of giving relates to religious giving. Ghana is a religiously active nation where about 94% of the population describe themselves as ‘religious persons’. Out of this, 71.2, 17.6 and 5.2% are Christians, Muslims and Traditionalists, respectively (GSS 2013). While there exist a substantial literature on religious giving in Africa (e.g. Weiss 2002; Everatt et al. 2005; Aina and Moyo 2013), the findings in this article suggests that in Ghana, religious giving is more concerned about donations to religious organisations like churches and mosques rather than supporting the needy. There is a greater emphasis on individualistic accumulation of wealth which affects faith-based giving and negates attempts to support the poor. Especially among Pentecostal and Charismatic Christian circles, individuals have become ‘entrepreneurial pastors’ who see their engagement in religion as mechanism for wealth creation and improving their social status of becoming ‘big men’ (Lauterbach 2017). A plausible explanation for the decline in religious giving towards the needy and NGDOs in particular is that most religious people have become more inward looking. This is also not to suggest that individuals do not give to fulfil religious obligations. For instance, Muslims give 2.5% of their income as Zakat. However, the emphasis is largely on giving to established religious institutions like churches and mosques. Weiss (2002) in his study of Islamic volunteering and communal support in Northern Ghana argues that in most non-Muslim countries, the collection and distribution of Zakat is transferred to public institutions such as mosques.

More importantly, the findings in this article indicate that religious giving in Ghana is largely non-institutionalised. The non-institutionalised nature points to important issues such as financial transparency and accountability with regard to religious giving. This often opens up space for embezzlement and misuse of funds by religious organisations especially churches where pastors are accused of stealing from individuals and church coffers to enrich themselves. This leads to what Lauterbach (2017:79–80) calls ‘fake pastors’ or ‘spiritual swindlers’. For this reason, the following important questions must therefore be asked: how do religious institutions see philanthropy and wealth distribution in Ghana? How effective are religious institutions in mobilising resources to advance philanthropic activities? While arguing that religious giving in Ghana tends to be more individualistic in nature, I also acknowledge that some religious organisations (e.g. churches and Muslim-based NGDOs) support individuals (e.g. establishing training and vocational centres) and play important roles in volunteering activities by raising awareness about important development challenges including gender violence and social justice. However, such philanthropic activities are framed normatively as their contributions to society. Nonetheless, these acts could be used as legitimisation strategies by some religious organisations to prevent their actions from being questioned. Using giving as a legitimatisation strategy becomes more pronounced in Ghana given that some religious organisations are accused of extracting money from poor church members without giving back to society.

For volunteering, the findings suggest that it goes beyond restricting it to individual engagement with formal organisations to that of informal activities such as communal labour. It is important to mention that volunteering in Ghana is multifaceted because it includes elements of formal and informal volunteering. Formal volunteering comprises of stipend volunteers such as interns and national service personnel or international volunteers who engage in voluntary activities to help NGDOs. Stipend volunteers especially national service personnel work on long-term basis as part of their one year of mandatory service which is coordinated by the national government. This form of volunteering in Ghana is common among most NGDOs because it tends to have an anti-poverty, economic development and national identity motives. Stipend volunteering is hybrid in nature because volunteers receive financial reward in the form of allowance while they engage in full-time work by helping national development (Bryer et al. 2016). On the other hand, informal volunteering is mostly non-stipend in nature but individuals engaging in voluntary activities such as taking care of the elderly or orphans in communities are mostly rewarded with material incentives. The rationale is to motivate them to continue the provision of their services.

The engagement in communal self-help projects is an important aspect of Ghanaian philanthropy which is ignored in the literature because this form of social mobilisation is not considered as volunteering. This is highly problematic as volunteer labour constitutes an important part of community development especially in rural areas of Ghana (Bougangue and Ling 2017). Moreover, given that there are multiple volunteering cultures in Ghana, it is unhelpful to pay attention to volunteering in formal institutions to the neglect of the informal forms of volunteering. The Western-oriented understanding of volunteering fails to capture the complexity of volunteering in Ghana where even the poor in society gives their time and energy to support community development. For instance, people in a village may decide to embark on volunteering as a way of promoting mutual help and reciprocity. A typical example is the use of cooperative labour popularly known as Nnoboa among some farmers and Asafo (i.e. community security groups) in traditional communities in Ghana.

Remittances are an important aspect of Ghana’s philanthropic landscape. Remittances have expanded in recent years despite the dwindling nature of ODA and continue to serve as the most important source of external resources for sub-Saharan African countries. For example, remittances are estimated to increase to about $66.2 billion in 2017. In addition, revenue volatility associated with remittances is relatively lower compared to ODA (Maimbo and Ratha 2005; AfDB 2017). This makes diaspora philanthropy an importance source of resource mobilisation and socio-economic development especially for most developing countries (Gyimah-Brempong and Asiedu 2015; Hudson Institute 2016). In terms of remittance inflow, between 2014 and 2015, Ghana received about US $1.92 billion. This figure surpassed ODA grants received for the same period which totalled about US $741.9 million (OECD 2016b). However, due to the absence of a comprehensive data on remittances towards philanthropic activities, it is difficult such inflows because official statistics do not account for informal channels within which remittances are transferred. While greater emphasis is placed on remittances in recent years as alternative source of development finance (Frimpong-Boamah et al. 2017), its potential to sustain NGDOs in the long-term remains unknown because its usage tends to focus on smoothing consumption rather than investment into organisational development and programme expansion.

Nonetheless, diaspora philanthropy has implications for NGDOs’ financing as they use their outside connections and experience in helping them to mobilise additional resources. Moreover, when diaspora philanthropy is targeted at specific NGDO projects and programmes, it can help address some of the funding gaps. Approaches such as the issuance of diaspora bonds and tapping into their knowledge base some commentators have argued could help in serving as alternative development finance (Boamah et al. 2017; Hudson Institute 2016). While such suggestions are welcoming, its implementation and effectiveness depends on institutional environment such as the creation of a favourably enabling environment that encourages diaspora philanthropy. However, at present, the creation of an enabling environment for diaspora philanthropy in Ghana remains limited. For example, according to the Hudson Institute’s Index of Philanthropic Freedom, Ghana was ranked 48th out of 64 countries with an overall score of 3.1 while Tanzania was ranked 23rd with an overall score of 3.8 (Hudson Institute 2015). The absence of a policy framework and structural support for philanthropic activities in Ghana accounted for the differences in the ranking. This points to wider challenges associated with the Ghanaian philanthropic landscape which is discussed below.

Challenges and Recommendations for the Ghanaian Philanthropic Sector

The Ghanaian philanthropic sector is confronted with obstacles including the absence of a conducive environment that encourages philanthropy, the lack of data on philanthropic activities and engagement with philanthropic institutions as development partners rather than development financiers. To begin with, there is the need for government to play a role in creating the enabling environment and policy framework for the philanthropic sector. The contributions of philanthropic institutions in serving as alternative resource mobilisation routes will largely depend on the creation of an enabling environment. However, currently this is lagging because there is no single legal framework that is specifically targeting the philanthropic sector. The resultant effect is that the sector is not properly regulated although the Department for Social Welfare (DSW) is charged with the responsibility. While there is an increasing emphasis on the mobilisation of domestic resources through philanthropy, little attention has been paid to efforts aimed at building and strengthening the capacity of institutions responsible for encouraging domestic philanthropy. At present, weak capacity of state institutions in the philanthropic sector remains an important challenge in Ghana. The relationship between institutional capacity and domestic resource mobilisation is well documented in the literature (see Nnadozie et al. 2017). Addressing this crucial challenge would provide useful insights into understanding the philanthropic sector in Ghana.

At present, philanthropic institutions only register as a trust or a company limited by guarantee with the Registrar General’s Department (RGD). The inability of government to regulate the philanthropic sector has far-reaching consequence. This includes the absence of other key enabling factors like tax exemptions. For example, corporate foundations and individuals lack incentives to give to NGDOs due to the absence of laws that encourages domestic giving. In particular, the private sector is faced with structural problems including loan accessibility, high inflation, uncertain business environment and erratic power supply. For example, according to ISSER (2015), the small- and medium-sized enterprise sector lost an average of $2.2 million due to erratic power supply in 2014. This makes it challenging for organisations struggling for survival to support corporate philanthropy. Nonetheless, establishing stronger relations with corporate organisations could serve as potential source for the mobilisation of resources but this requires an enhancement of NGDOs’ organisational capacity and skills. It also raises concern about reputation risks in NGDO-corporate relations. In encouraging domestic philanthropy, government has an important role in ensuring that the public build trust in philanthropic institutions. This will ensure that individuals can easily give to support charitable cause. In an environment where there is little transparency, giving becomes challenging.

Another concern is the need for government to recognise philanthropic institutions as development partners rather than just providers of financial resources in tackling development challenges. There is still lack of development debate on the linkage between philanthropy and national development. For example, there are no clear-cut national philanthropic policies that are aligned to any development plan despite the launching of the preparation process for Ghana’s long-term (40-year) development plan (2018–2057). I argue that Ghana’s national development policies are ‘philanthropic blind’. Thus, policy makers and development practitioners have not come to the realisation where the philanthropic sector is seen as complementary source of development finance. This could also be as a result of the lack of a comprehensive data on philanthropic sector. The lack of institutional data on philanthropy makes it difficult for development stakeholders to fully understand their potentials, opportunities, challenges and priority areas for improvement. Government agencies and philanthropic institutions need to become familiar with the philanthropic landscape by recording, comparing and making information more accessible to stakeholders because limited information does not allow for effective research and documentation.

In overcoming the above challenges, the following are suggestions that could be considered to ensure a vibrant philanthropic sector in Ghana. First, there is the need to create an enabling environment for the effective functioning of civil society. This involves the creation of policy framework and financial incentives for the philanthropic sector. At present, the legal framework tends to impose burden rather than benefits to organisations and individuals who tend to support philanthropic activities. The lack of government support through fiscal or tax incentives needs to be critically looked at. This would also require strengthening the institutional capacity of the DSW and the RGD with the requisite resources to undertake their regulatory activities.

As part of their institutional strengthening, there is the need for the creation of a registry of all CSOs including philanthropic institutions in the country. At present a directory or census of philanthropic institutions in Ghana does not exist given that no survey has been conducted on this by academics or even government agencies. The creation of a national database would help in generating empirical evidence which could inform policy decisions regarding the philanthropic sector. The promotion of a legal and favourable enabling environment would help in promoting a culture of giving which is perceived to be lacking. This would also depend largely on the relationship between government and CSOs. At present, CSOs receive modest financial support from the central government. In going forward, there is the need for the establishment of a formally constituted national body devoid of political influence that would support the philanthropic sector. The establishment of a national body for the philanthropic sector would also help in institutionalising government’s relations with the diaspora where policy frameworks could be develop to mainstream diaspora philanthropy. The mainstreaming of diaspora philanthropy and development of a vibrant networking between NGDOs and diaspora is crucial.

Conclusions and Implications

The aim of this article was to examine the forms of philanthropic institutions in Ghana that could serve as potential alternative funding routes for NGDOs. This article contributes to the limited but growing literature on philanthropy in Ghana. The article advances the argument that Ghana as a new LMIC needs to move towards a civil society that is more diversified in its sources of funding particularly domestic resources from philanthropy institutions. However, for domestic resource mobilisation to be effective, there is the need for contextual sensitive approaches that promotes philanthropic engagement. The article has highlighted that the Ghanaian philanthropic sector is diverse and contains a mixture of horizontal, vertical, old and new forms of giving. Prominent among them include volunteerism which has become an important source of human resources for NGDOs in an era of projectised funding and absence of core funding which makes it difficult for NGDOs to retain their paid staff in the absence of donor projects.

The article further highlights the complexity of faith-based and individual giving which focuses more on familial and associational relations rather than giving to NGDOs. Corporate philanthropy mostly takes the form of product donations or staff volunteering while corporate foundations serve as branding, marketing and communication tool rather than a development-enhancing tool. Although many NGDOs are dependent on donor funding, the evidence presented here suggests that the philanthropic sector could serve as potential alternative but their ability to sustain NGDOs in the short-term remains limited. For this reason, it requires NGDOs to become agile actors or adaptive agents who are able to adopt and develop new organisational skills and learning, mindset shifts and innovative strategies that will help them to take advantage of the opportunities presented by philanthropic institutions in Ghana. While arguing for financial sustainability through alternative resource mobilisation, we should not also lose sight of the non-materialistic dimension of NGDOs’ sustainability such as their transparency, accountability, governance structures and legitimacy to stakeholders.

The findings of this study have implications for the philanthropic sector. First, a well-developed philanthropic sector could benefit NGDOs and CSOs by serving as alternative source of resource mobilisation especially in an environment characterised by dwindling donor support and changing funding priorities. Given Ghana’s lower-middle-income status and government’s quest for Ghana to become an ‘aid-free’ country, the philanthropic sector would play a key role in the sustainability of NGDOs and CSOs by filling the funding gaps (GOG 2012:10–12). The findings have wider implications for other transitioned economies where external donor funding is reported to be dwindling. Second, findings of this study also highlight the difficulty involved in adopting Western understanding of philanthropy into the African context. This opens up scope for discussion in developing a conceptual framework that captures the different dimensions of philanthropy which reflects the socio-cultural context of other developing countries especially those in Africa. At present, philanthropy in the literature is largely defined based on the experiences of countries based in the Global North which often fails to capture that of African and other developing countries. This article lays the ground for future research. Future research could examine the challenges faced by NGDOs in mobilising domestic resources from the philanthropic sector especially from corporate organisations. This will help shed more insights into the emerging political economy of NGDO financing in terms of domestic resource mobilisation strategies. By doing so, further research could explore giver–recipient relationships by focusing on NGDO-corporate partnerships in terms of power relations and ethics of such partnerships. Other future research could examine the relationship between philanthropic institutions and key development stakeholders including donors, government and NGDOs.

Notes

For the purpose of this article, I focus on national NGDOs rather than international NGDOs. National NGDOs have their origin, registration status and governance structure within Ghana. They are owned and managed by Ghanaians and do not include INGOs that have acquired local registration within Ghana.

Joy Business (2016). UK joins the European Union to cut aid to Ghana. For details see http://www.myjoyonline.com/business/2016/October-7th/uk-joins-the-european-union-to-cut-aid-to-ghana.php.

I follow Fowler (2016b:4) in using African gifting as ‘resources generated by the continent and applied philanthropically for its development’. In this article, I use the term gifting because the definition of philanthropy as using private resources to advance public good does not capture the whole range of resource options including diaspora finance and horizontal gifting between people like time, money, skills and labour that can be highly targeted to individuals and not the public as such as practiced in Ghana. It is also worth noting that mainstream philanthropy constitutes one class of gifting practices and therefore care should to be taken in not equating one with each other.

For details, see http://akuapemcf.org/.

CSR is used as a generic term to include corporate social investment as well as the engagement of corporate organisations in social and philanthropic activities.

References

Abdulai, A. G. (2017). The political economy of regional inequality in Ghana: Do political settlements matter? The European Journal of Development Research,29(1), 213–229.

African Development Bank (AfDB). (2017). African economic outlook 2017: Entrepreneurship and Industrialisation. Retrieved August 12, 2017 from http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/outlook.

African Grantmakers Network. (2013). Sizing the field: Frameworks for a new narrative of African Philanthropy. Johannesburg: African Grantmakers Network. Retrieved March 4, 2017 from https://www.issuelab.org/resource/sizing-the-field-frameworks-for-a-new-narrative-of-african-philanthropy.html.

Aina, T. A., & Moyo, B. (Eds.). (2013). Giving to help, helping to give: The context and politics of African philanthropy. Dakar: Amalion Publishing.

Arhin, A. (2016). Advancing post-2015 sustainable development goals in a changing development landscape: Challenges of NGOs in Ghana. Development in Practice,26(5), 555–568.

Bougangue, B., & Ling, H. K. (2017). Male involvement in maternal healthcare through Community-based Health Planning and Services: the views of the men in rural Ghana. BMC Public Health,17(693), 1–10.

Bryer, T. A., Pliscoff, C., Lough, B. J., Obadare, E., & Smith, D. H. (2016). Stipended National Service Volunteering. In D. H. Smith, R. A. Stebbins, & J. Grotz (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of volunteering, civic participation, and nonprofit associations (pp. 259–274). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Clementi, F., Molini, V., & Schettino, F. (2016). All that glitters is not gold: Polarization amid poverty reduction in Ghana. Policy Research Working Paper, 7758. World Bank, Poverty and Equity Global Practice Group.

DANIDA. (2015). Danida’s involvement in the Ghanaian health sector 1994–2015: Documentation Study—Technical Report. Retrieved October 28, 2016 from http://ghana.um.dk/en/news/newsdisplaypage/?newsid=024751c2-db08-4c70-8dc1-f55519d9cd59.

Everatt, D., Habib, A., Maharaj, B., & Nyar, A. (2005). Patterns of giving in South Africa. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16(3), 275–291.

Foundation Centre. (2015). US Foundation funding for Africa (2015th ed). Retrieved August 12, 2016 from http://africagrantmakers.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/FC_KFAfrica_2015_web-version.pdf.

Fowler, A. (2016a). Non-governmental development organisations’ sustainability, partnership, and resourcing: Futuristic reflections on a problematic trialogue. Development in Practice,26(5), 569–579.

Fowler, A. (2016b). NGO-business partnership and north-south power perspectives from African philanthropy. Paper presented at the development studies association conference, September 12–14, 2016. University of Oxford.

Fowler, A. (2016c). Concepts and framework for teaching, research and outreach of African philanthropy. Retrieved December 12, 2016 from http://africanphilanthropy.issuelab.org/resource/concepts-and-framework-for-teaching-research-and-outreach-of-african-philanthropy.html.

Frimpong-Boamah, E., Osei, D., & Yeboah, T. (2017). Beyond patriotic discourse in financing the SDGs: Investment-linked diaspora revenue bonds model for sub-Saharan Africa. Development in Practice, 27(4), 555–574.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2013). 2010 population and housing census report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2014). Ghana Living Standard Survey 6. Poverty profile report. Retrieved October 15, 2016 from http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/glss6/GLSS6_Main%20Report.pdf.

Government of Ghana (GOG). (2012). Leveraging partnership for shared growth and Development. Government of Ghana-Development Partners Compact-2012–2022. Accra.

Gyasi-Obeng, S. (1996). The proverb as a mitigating and politeness strategy in Akan discourse. Anthropological Linguistics,38(3), 521–549.

Gyimah-Brempong, K., & Asiedu, E. (2015). Remittances and investment in education: Evidence from Ghana. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development,24(2), 173–200.

Hailey, J., & Salway, M. (2016). New routes to CSO sustainability: The strategic shift to social enterprise and social investment. Development in Practice,26(5), 580–591.

Hayman, R. (2016). Unpacking civil society sustainability: Looking back, broader, deeper, forward. Development in Practice,26(5), 670–680.

Hayman, R., & Lewis, S. (2017). INTRAC’s experience of working with international NGOs on aid withdrawal and exit strategies from 2011 to 2016. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9901-x.

Hyden, G. (1983). No Shortcuts to progress: African Development Management in Perspective. London: Heinemann.

Initiatives, Development. (2013). Investments to end poverty-Development Initiatives. Bristol: Development Initiatives.

Institute, Hudson. (2015). The index of philanthropic freedom 2015. Washington: Hudson Institute.

Institute, Hudson. (2016). The index of global philanthropy and remittances 2016. Washington: Hudson Institute.

ISSER. (2015). State of the Ghanaian Economy Report 2014. Accra: Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, University of Ghana.

Jerven, M. (2016). Research note: Africa by numbers: Reviewing the database approach to studying African economies. African Affairs,115(459), 342–358.

Jerven, M., & Duncan, M. E. (2012). Revising GDP estimates in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Ghana. African Statistical Journal,15, 13–24.

Joy Business. (2016). UK joins the European Union to cut aid to Ghana. Retrieved October 7, 2016 from http://www.myjoyonline.com/business/2016/October-7th/uk-joins-the-european-union-to-cut-aid-to-ghana.php.

Kumi, E. (2016). Responding to falling external aid flows: Funding mobilisation strategies of national non-governmental development organisations (NGDOs) in Ghana. A paper presented at ARNOVA conference, November 17–19, 2016. Washington.

Lauterbach, K. (2017). Christianity, wealth, and spiritual power in Ghana. Cham: Springer.

Maimbo, S. M., & Ratha, D. (2005). Remittances: Development impact and future prospects. Washington: World Bank Publications.

Masolo, D. A. (2004). Western and African communitarianism: a comparison. In K. Wiredu (Ed.), A companion to African philosophy (pp. 483–497). Malden: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

Moss, T., & Majerowicz, S. (2012). No longer poor: Ghana’s new income status and implications of graduation from IDA. Working Paper 300, Centre for Global Development. Retrieved April 26, 2016 from http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/1426321.

Moyo, B. (2011). Transformative innovations in African philanthropy. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies. Retrieved January 3, 2016 from http://www.bellagioinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Bellagio-Moyo.pdf.

Moyo, B., & Ramsamy, K. (2014). African philanthropy, pan-Africanism, and Africa’s development. Development in Practice,24(5–6), 656–671.

Nally, D., & Taylor, S. (2015). The politics of self-help: The Rockefeller Foundation, philanthropy and the ‘long’ green revolution. Political Geography,49, 51–63.

Nnadozie, E., Munthali, T. C., Nantchouang, R., & Diawara, B. (2017). Domestic resource mobilization in Africa: Capacity imperatives. In N. Biekpe, D. Cassimon, & A. W. Mullineux (Eds.), Development finance: Innovations for sustainable growth (pp. 17–49). Palgrave: Cham.

OECD. (2016a). OECD development co-operation peer reviews: Denmark 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016 from http://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/download/4316041e.pdf?expires=1489414666&id=id&accname=ocid56018429&checksum=B0CC03BF1E9B547F5D013BF9D8186F36.

OECD. (2016b). Geographical distribution of financial flows to developing countries 2016. Disbursements, commitments, country indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.