Abstract

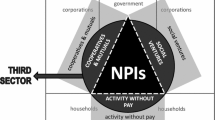

This study draws an economic model of the growth of nonprofit organizations by analyzing the behaviors of three major actors—nonprofit organizations, private donors, and governments—in making decisions on the allocation of limited resources for nonprofit services. Since decisions made by each actor affect resource allocation, it is important to understand what drives these decisions. The model was tested using an unbalanced, 463 panel dataset collected from 28 OECD countries over a 23-year period. The results indicated that macro- and micro-economic trends and government policies framed the decision premises of the three major actors, which led them to leverage the supply and demand for goods and services and, in turn, determined how they allocated limited resources for nonprofit services. This result implies that understanding the interdependencies of all sectors of the economy is critical to comprehending the size and development of the nonprofit sector. Effective management of micro-economic policies and macro-economic stability is necessary. More important, however, is understanding how a decision in one part of the economy will have intended and unintended effects on the nonprofit sector.

Résumé

Cette étude s’inspire d’un modèle économique de développement des organisations à but non lucratif en analysant les comportements des trois principaux acteurs — organisations à but non lucratif, donateurs privés et organismes publics — pour la prise de décisions concernant l’affectation des ressources limitées des services à but non lucratif. Étant donné que les décisions prises par chaque acteur ont une incidence sur cette affectation, il est important de comprendre ce qui motive ces décisions. Le modèle a été testé à l’aide d’un ensemble de 463 panels non compensés recueillis dans 28 pays de l’OCDE sur une période de 23 ans. Les résultats indiquent que les tendances macro et microéconomiques et les politiques gouvernementales orientaient les lieux de décision des trois acteurs principaux, ce qui les amenait à tirer parti de l’offre et de la demande pour les biens et les services et, partant, déterminait comment ils affectaient les ressources limitées aux services à but non lucratif. Ce résultat signifie que la compréhension de l’interdépendance de tous les secteurs de l’économie est essentielle pour comprendre la taille et le développement du secteur à but non lucratif. Une gestion efficace des politiques microéconomiques et de la stabilité macroéconomique est nécessaire. Mais il est encore plus important de comprendre comment une décision prise dans une partie de l’économie va avoir des effets intentionnels et non intentionnels sur le secteur à but non lucratif.

Zusammenfassung

Diese Studie entwirft ein Wirtschaftsmodell zum Wachstum gemeinnütziger Organisationen, indem die Verhaltensweisen dreier wichtiger Akteure - gemeinnützige Organisationen, private Spender und Regierungen - bei der Entscheidungsfindung zur Verteilung begrenzter Ressourcen für gemeinnützige Dienstleistungen analysiert werden. Da sich die Entscheidungen eines jeden Akteurs auf die Ressourcenverteilung auswirken, ist es wichtig zu verstehen, was diese Entscheidungen lenkt. Das Modell wurde mittels 463 unbalancierter Paneldaten getestet, die aus 28 OECD-Ländern über einen Zeitraum von 23 Jahren erfasst wurden. Die Ergebnisse wiesen darauf hin, dass makro- und mikroökonomische Trends sowie die Regierungspolitik die Entscheidungsprämissen der drei Hauptakteure bestimmten, unter Berücksichtigung derer sie das Angebot an und die Nachfrage nach Waren und Dienstleistungen wirksam einsetzten und die begrenzten Ressourcen für gemeinnützige Dienstleistungen verteilten. Dieses Ergebnis impliziert, dass das Verständnis der Wechselbeziehungen zwischen allen Wirtschaftssektoren wichtig ist, um die Größe und Entwicklung des gemeinnützigen Sektors zu erfassen. Das effektive Management mikroökonomischer Richtlinien und makroöknomischer Stabilität ist notwendig. Noch wichtiger ist es jedoch zu verstehen, dass eine Entscheidung in einem Wirtschaftsbereich beabsichtigte und unbeabsichtigte Folgen für den gemeinnützigen Sektor hat.

Resumen

El presente estudio dibuja un modelo económico del crecimiento de las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro mediante el análisis de los comportamientos de tres actores importantes - organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro, donantes privados y gobiernos - en la toma de decisiones sobre la asignación de recursos limitados para servicios sin ánimo de lucro. Dado que las decisiones tomadas por cada actor afectan a la asignación de recursos, es importante comprender qué impulsa estas decisiones. El modelo fue puesto a prueba utilizando un conjunto de datos de un panel desequilibrado de 463 recopilado en 28 países de la OCDE a lo largo de un período de 23 años. Los resultados indicaron que las tendencias macro- y microeconómicas y las políticas gubernamentales enmarcaban las premisas decisorias de los tres importantes actores, que les llevaban a aprovechar la oferta y la demanda de bienes y servicios y, a su vez, determinaba cómo asignaban recursos limitados para servicios sin ánimo de lucro. Este resultado implica que la comprensión de las interdependencias de todos los sectores de la economía es fundamental para comprender el tamaño y desarrollo del sector de las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro. Es necesaria una gestión efectiva de las políticas microeconómicas y de la estabilidad macroeconómica. Sin embargo, es más importante comprender cómo una decisión en una parte de la economía tendrá efectos previstos e imprevistos en el sector de las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro.

摘要

本研究通过分析三种主要活动主体(即非营利性组织、私人捐赠者与政府)针对非营利性服务配置有限资源的决策行为,建立一个非营利性组织的增长经济模型。由于每一活动主体的决策都影响资源配置,所以,理解这些决策的动因非常重要。 我们使用一个非平衡、463组数据组对该模型进行测试;该数据组采集自28个经济合作与发展组织(OECD)国家,数据的时间跨度长达23年。结果显示,宏观与微观经济趋势与政府政策限定了三大活动主体的决策前提,导致他们反过来利用产品与服务的供求确定如何为非营利性服务配置有限资源。这一结果暗示,理解所有经济部门的相互依赖性,对于理解非营利性部门的规模与发展至关重要。对微观经济政策与宏观经济稳定性的有效管理是必要的。然而,更为重要的是理解经济体某一部分的决策是如何对非营利性部门产生预期与预期之外的影响的。

ملخص

تعتمد هذه الدراسة على النموذج الاقتصادي لنمو المنظمات الغير هادفة للربح عن طريق تحليل سلوكيات لثلاثة جهات فاعلة - منظمات غير ربحية رئيسية ، جهات مانحة خاصة، والحكومات في إتخاذ القرارات بشأن تخصيص الموارد المحدودة للخدمات الغير ربحية. حيث أن القرارات التي يتخذها كل طرف تؤثر على تخصيص الموارد، فمن المهم أن نفهم ما يدفع هذه القرارات. تم إختبار هذا النموذج بإستخدام غير متوازن، 463 لوحة بيانات تم جمعها من 28 دول منظمة التعاون الاقتصادي (OECD) على مدى فترة 23 عاما. أشارت النتائج إلى أن الإقتصاد الكلي والإقتصاد الجزئي الإقتصادي الاتجاهات والسياسات الحكومية تضع إطار في حدود قرار الجهات الفاعلة الرئيسية الثلاثة، الذي يدفعهم إلى الإستفادة من العرض والطلب على السلع والخدمات، بالتالي، تحديد الكيفية التي تخصص موارد محدودة لخدمات غير ربحية. هذه النتيجة تعني أن فهم ترابط جميع قطاعات الإقتصاد أمر بالغ الأهمية لفهم حجم وتطوير القطاع الغير ربحي. الإدارة الفعالة لسياسات الإقتصاد الجزئي وإستقرار الإقتصاد الكلي أمر ضروري. الأهم من ذلك، مع ذلك، فهم كيف يمكن لقرار في جزء واحد من الإقتصاد سوف يكون له آثارمقصودة و غير مقصودة على القطاع الغير ربحي.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Not every country shows the same percentage of giving patterns among private donors. For example, most of the private giving (60 %) in South Korea comes from corporations, not from individuals.

Although Eq. 3 is created using individual donor behavior, we still took the corporate income tax rate into account in the equation because corporate giving is a part of total donations and because the corporate income tax rate affects a corporation’s decision to make philanthropic contributions in a way similar to how the personal income tax rate affects an individual’s decision to make philanthropic contributions. In Eq. 5, either personal or corporate income tax can serve as a variable affecting a private donor’s decision to give.

Different countries offer different types of tax incentives for charitable contributions. For example, in the United States, tax payers receive a deduction from their taxable income. The ceiling for these deductions is very high, up to 50 % of their taxable income. In Germany, tax relief is capped at only 20 % of taxable income. The French system uses a non-refundable tax credit. Countries also differ in how they manage tax incentives for charitable giving in terms of the registration and reporting requirements (Fack and Landais 2012). Despite the national differences, tax incentives through adjusting income tax rates are important tools for charitable giving and for nonprofit development.

The 28 OECD countries analyzed in this study are Austria (23), Belgium (23), Canada (19), the Czech Republic (12), Denmark (23), Finland (13), France (23), Germany (21), Greece (13), Hungary (11), Ireland (12), Israel (7), Italy (15), Japan (21), Luxembourg (15), Mexico (5), Netherlands (22), Norway (23), Poland (11), Portugal (18), South Korea (12), Slovakia (10), Slovenia (8), Spain (15), Sweden (23), Switzerland (21), the United Kingdom (23), and the United States (21). The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of data points collected from each country.

Over the 23-year period, the NPISH expenditure increased at the slowest pace in Italy, with an average of .37 % of annual growth, and a range of 0.3–0.4 %. In contrast, the United Kingdom showed the highest rate of growth during the same period, with a range of 2.5 to 3.3 %, and an average NPISH expenditure of 2.9 %. The United States recorded the largest percentage of change, with a range of 1 to 2.1 %, more than double what it spent 23 years ago.

NPISH data do not represent all nonprofits (HR Council for the Nonprofit Sector 2010). The SNA classifies nonprofit institutions into five different sectors, of which the NPISH sector is the only sector that has “nonprofit” in its title. The other four sectors are (1) the non-financial corporations sector, which includes nonprofits that receive most of their revenue from the sales of non-financial services, such as universities or hospitals; (2) the financial corporations sector, which includes some nonprofits, such as microfinance organizations, which are principally engaged in financial transactions; (3) the government sector, which includes government-sponsored nonprofits; and (4) the household sector, which includes nonprofits that rely solely on volunteer inputs (United Nations Statistic Division 2013).

It is difficult to identify what percentage of nonprofits the NPISH measure covers for each country because the exact total number of nonprofits in each country is unknown; therefore, it is impossible to calculate the percentage of NPISH of the total nonprofits. In Canada, NPISH makes up approximately 22 % of the nonprofit sector by GDP (HR Council for the Nonprofit Sector 2010). However, other countries should have a different percentage of NPISH of the total nonprofits, in part because the types of work NPISH performs differ significantly in different countries. NPISH typically includes organizations or services, such as churches and religious societies, recreational services, education and research centers, and health services (Mead et al. 2003), but in Canada, NPISH data excludes universities while data in England include them (Office for National Statistics 2014). A significant portion of NPISH includes organizations that provide health and social services, but it excludes those that make profits for their owners and charge market rates for their services. In health care, for example, NPISH data include community health services but exclude hospitals. Social services include food banks and counseling services but exclude day care services that charge market rates.

The NPISH revenues may also include delayed payments from government, one-time capital costs, dividends, interest and investment income, or other revenues not associated with providing services.

The following equation was used to arrive at 94.5 %: \(\text{NPISH} = - \text{0}\text{.04163} \times \text{UrbanPOP}^{\text{2}} + \text{0}\text{.07864} \times \text{UrbanPOP} + \text{C}\)

References

Abrams, B. A., & Schmitz, M. D. (1978). The crowding-out effect of governmental transfers on private charitable contributions. Public Choice, 33, 30–39.

Anheier, H. K. (2013). The Nonprofits of 2025(10th Anniversary Essays). Stanford Social Innovation Review 18–19.

Anheier, H. K. (2014). Nonprofit organizations: Theory, management, and policy (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Ashburn, R. (2011). INSIGHT-Mild inflation, low interest rates could help economy. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/usa-debt-inflation-idUSN1E7711UC20110802.

Barns, R. (2006). The Importance of Inflation and GDP. Retrieved from www.investopedia.com/articles/06/gdpinflation.asp#ixzz3rdglEuFh.

Berger, P. L., & Neuhaus, R. J. (1977). To empower people: the role of mediating structures in public policy. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Brooks, A. C. (2003). Do government subsidies to nonprofit crowd out donations or donors? Public Finance Review, 31(2), 166–179.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (2013). http://www.bea.gov/. Retrieved 4, April, 2014. The U.S. Department of Commerce.

Dighe, Atul. (2002). Demographic and technological imperatives. In L. M. Salamon (Ed.), The state of nonprofit America (pp. 499–516). Washington, DC: Brookings.

Douglas, James. (1987). Political theories of nonprofit organizations. In W. W. Powell (Ed.), The nonprofit sector: a research handbook (pp. 43–54). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fack, Gabrielle, & Landais, Camille. (2012). Charitable giving and tax policy: a historical and comparative perspective. Paris: Paris School of Economics.

Gamm, G., & Putnam, R. D. (1999). The growth of voluntary Associations in America, 1840–1940. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 29, 511–557.

Green, W. H. (2008). Econometric Analysis (6th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Grønbjerg, K. A., & Paarlberg, Laurie. (2001). Community variations in the size and scope of the nonprofit sector: theory and preliminary findings. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 30(4), 684–706.

Hansmann, H. (1980). The role of nonprofit enterprise. The Yale Law Journal, 89(5), 835–901.

Hansmann, H. (1981). Nonprofit enterprise in the performing arts. Bell Journal of Economics, 12(2), 341–361.

Hansmann, H. (1985). The effect of tax exemption and other factors on competition between nonprofit and for-profit enterprise. Yale University, Program on Non-profit Organizations Working Paper No. 65.

Hansmann, H. (1987). Economic theories of nonprofit organization. In W. W. Powell (Ed.), The nonprofit sector: a research handbook (pp. 27–42). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Henriksen, L. S., Smith, S. R., & Zimmer, A. (2012). At the eve of convergence? Transformations of social service provision in Denmark, Germany, and the United States. Vountas, 23, 458–501.

HR Council for the Nonprofit Sector. (2010). Employment trends in Non Profit Institutions Serving Households: Nonprofit health and welfare organizations. Retrieved from www.hrcouncil.ca/documents/LMI_NPISH_healthandwelfare.pdf.

James, E. (1987). The nonprofit sector in comparative perspective. In W. W. Powell (Ed.), The nonprofit sector: a research handbook (pp. 397–415). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kim, S. E., & Kim, Y. H. (2015). Measuring the growth of the nonprofit sector: A longitudinal analysis. Public Administration Review, 75(2), 242–251.

Lecy, J. D., & Van Slyke, D. M. (2013). Nonprofit sector growth and density: testing theories of government support. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(1), 189–214.

Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University. (2015). Giving USA 2015: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2014. Chicago, IL: Giving USA Foundation.

Malatesta, D., & Smith, C. R. (2014). Lessons from resource dependence theory for contemporary public and nonprofit management. Public Administration Review, 74(1), 14–25.

Matsunaga, Y., & Yamauchi, Naoto. (2004). Is the Government Failure Theory Still Relevant? a panel analysis using US state level data. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 75, 227–263.

Matsunaga, Y., Yamauchi, N., & Okuyama, N. (2012). What determines the size of the nonprofit sector: a cross-country analysis of the government failure theory. Voluntas, 21(2), 180–201.

Mead, C. I., McCully, C. P., & Reinsdorf, M. B. (2003). Income and outlays of households and of nonprofit institutions serving households. Washington DC: Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Murphy, T. B. (2000). Financial and psychological determinants of donor’s capacity to give. New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising, 2000(29), 33–49.

Newhouse, J. P. (1970). Toward a theory of nonprofit institutions: an economic model of a hospital. American Economic Review, 60(1), 64–74.

Nikolova, M. (2015). Government funding of private voluntary organizations: is there a crowding-out effect? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(3), 487–509.

Oberfield, Z. (2014). Accounting for time: comparing temporal and atemporal analyses of the business case for Diversity management. Public Administration Review, 74(6), 777–789.

Office for National Statistics. (2014). Changes to national accounts: review of the non-profit institutions serving household sector. United Kingdom.

Pennings, J. M. (1982). Organizational birth frequencies: an empirical investigation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 120–144.

Pevcin, P. (2012a). Analysis of cross-country differences in the nonprofit sector size. Prague Economic Papers, 2, 186–204.

Pevcin, P. (2012b). Demand and supply side view on the factors affecting size of nonprofit economy. Economic Research, 25(1), 140–162.

Popielarz, P. A., and McPherson J. M. (2001). On the edge or in between: niche position, niche overlap, and the duration of voluntary association membership. In J. Steven Ott (ed.). The nature of the nonprofit sector (pp. 258–266). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Renz, L. (2003). An overview of revenue streams for nonprofit arts organizations. Grantmakers in the arts reader: Vol. 14, No. 2, http://www.giarts.org/article/overview-revenue-streams-nonprofit-arts-organizations.

Reynolds, R. (2013). Why people give: understanding donor motivation. Retrieved from www.nonprofit-knowhow.com/blog/donor-motivation-why-do-people-give.

Saidel, J. R. (1991). Resource interdependence: the relationship between public agencies and nonprofit organizations. Public Administration Review, 51(6), 543–553.

Salamon, L.M., Sokolowski S.W., and Anheier H. K. (2000). Social origins of civil society: an overview. Working papers of the Johns Hopkins comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no. 38. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.

Salamon, L. M. (2012). The state of nonprofit America (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Brookings.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1995). Partners in public service: government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1997). The civil society sector. Society, 34, 60–65.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1998). Social origin of civil society: explaining the nonprofit sector cross-nationally. Voluntas, 9(3), 213–248.

Salamon, L.M., Sokolowski, W. (2001). Volunteering in cross-national perspective: evidence from 24 countries. The John Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies Working Paper No. 40.

Salamon, L. M., Wojciech, S. S., & Associates. (2004). Global civil society: dimensions of the nonprofit sector (Vol. II). Bloomfield: Kumarian Press.

Saxton, G. D., & Benson, M. A. (2005). Social capital and the growth of the nonprofit sector. Social Science Quarterly, 86(1), 16–35.

Schiff, J. (1984). Government output, government grants and charitable donations. Department of Economics, Tulane University.

Schiff, J. and Weisbrod, B. A. (1986). Government social welfare spending and the private nonprofit sector: crowding out and more. Unpublished manuscript. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Seibel, W. (1990). Government/third sector relationships in a comparative perspective: the cases of france and West Germany. Voluntas, 1, 42–61.

Skocpol, T., Ganz, M., & Munson, Z. (2000). A nation of organizers: the Institutional origins of civic voluntarism in the United States. American Political Science Review, 94(3), 527–546.

Stanzler, C., Radday, A., & Nabi, P. (2013). Informed giving: information donors want and how nonprofits can provide it. Boston, MA: Root Cause.

Stevens, J. B. (1993). The economics of collective choice. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Torres-Reyna, O. (2007). Panel data analysis fixed and random effects using stata. Available from http://www.princeton.edu/~otorres/Panel101.pdf, Princeton University.

United Nations Statistic Division. (2013). The system of national accounts. Retrieved from www.unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/sna.asp.

Van Slyke, D. M., & Brooks, A. C. (2005). Why do people give? New evidence and strategies for nonprofit manager. American Review of Public Administration, 35(3), 199–222.

Varian, H. R. (1992). Microeconomic analysis (3rd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1988). The nonprofit economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1997). The future of the nonprofit sector: its entwining with private enterprise and government. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 16(4), 541–555.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2013). Introductory econometrics: a modern approach (5th ed.). Independence, KY: Cengage Learning.

Worth, M. J. (2014). Nonprofit management: principles and practice (Vol. 3). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Young, D. R. (2000). Alternative models of government-nonprofit sector relations: theoretical and international perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 149–172.

Young, D. R., & Salamon, L. M. (2002). Commercialization, social ventures, and for-profit competition. In L. M. Salamon (Ed.), The state of nonprofit America (pp. 423–446). Washington, DC: Brookings.

Young, D. R., & Steinberg, R. (1995). Economics for nonprofit managers. New York: Foundation Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-2016).

Appendix

Appendix

The results of partial derivatives were derived from the economic optimization model, in which nonprofits try to maximize productions under cost restrictions. Below is the Lagrangian function, merging (Eq. 1) and (Eq. 2) listed on p. 7. The production efficiency condition—that the marginal rate of technical substitution is equal to the relative unit costs—is derived from partial derivatives of the Lagrangian function:

The factor demand functions, L* and K*, were drawn from the efficiency condition and cost restrictions. Next, we ended up with the following service supply function by inserting the factor demand functions into the production function:

The service supply function can vary depending on prices (P), subsidies (S), and donations (D) per unit services. The partial differentiation of prices, subsidies, and donations per unit services was positive because the quantity of nonprofit services increases as they get more money:

Similarly, the partial differentiation of wage was negative, because more wages mean more costs.

However, the effects of both the interest rate and the labor income share on the quantity of nonprofit services were mixed. First, an increase in interest rate means rising costs of nonprofit services, but nonprofits can simultaneously earn assets. Second, while an increase in the labor income share can save costs when the wage growth is slower than that of the interest rate, costs can increase when the reverse is true.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y.H., Kim, S.E. Testing an Economic Model of Nonprofit Growth: Analyzing the Behaviors and Decisions of Nonprofit Organizations, Private Donors, and Governments. Voluntas 27, 2937–2961 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9709-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9709-0