Abstract

Gamification has been discussed as a standout approach to improve user experience, with different studies showing that users can have different preferences over game elements according to their user types. However, relatively less is known how different kinds of users may react to different types of gamification. Therefore, in this study (\(N=331\)) we investigate how user orientation (Achiever, Disruptor, Free Spirit, Philanthropist, Player, and Socializer) is associated with the preference for and perceived sense of accomplishment from different gamification designs. Beyond singular associations between the user orientation and the gamification designs, the findings indicate no comprehensive and consistent patterns of associations. From the six user orientations, five presented significant associations: Socializer orientation was positively associated with Social, Fictional, and Personal designs, while negatively associated with Performance design; Player orientation was positively associated with Social (Accomplishment), Personal, and Ecological designs, while negatively associated with the Social design (Preference); Disruptor orientation was positively associated with Social design; Achiever orientation was positively associated with Performance and Social designs; and Free Spirit orientation was negatively associated with Social design. Based on the results, we provide recommendations on how to personalize gamified systems and set further research trajectories on personalized gamification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Gamification has been widely used in recent years to increase users’ motivation in different areas, such as health (Johnson et al. 2016), virtual reality (Hassan et al. 2020), and education (Barata et al. 2013; Turan et al. 2016; Araya et al. 2019). According to Koivisto and Hamari (2019), the education/learning context is the most common in studies about gamification, and most have reported positive results. One goal of the use of gamification in education is to lead students to desired psychological outcomes (e.g., engagement, motivation, fun, or autonomy (Majuri et al. 2018)); however, some studies have also reported that gamification can have negative effects on students’ behavior (Hanus and Fox 2015; Toda et al. 2017; Bai et al. 2020).

One of the main hypotheses for these negative effects is that people have different player types (i.e., different characteristics and preferences over game elements (Nacke et al. 2014)), which leads to different perceptions regarding the gamification design (Lavoué et al. 2018; Hallifax et al. 2019b; Oliveira et al. 2020), that can positively or negatively be affected by some of the game’s elements (Oliveira and Bittencourt 2019b). At the same time, most of the gamified systems are developed in a way called “one size fits all”, which means that the users’ preferences are ignored and normally the designers create a universal gamified environment to suit all users (Tondello et al. 2017b; Oliveira et al. 2018), thus possibly negatively affecting their experience (Tondello et al. 2017b; Lavoué et al. 2018; Rodrigues et al. 2019).

Although in the past few years researchers have conducted some studies about personalized gamification (Hallifax et al. 2019a; Klock et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2020), they have not reached a consensus about which game elements would be the most suitable for each player/user type, have used a small number of game elements, or have analyzed the relation of user types and game elements individually (Hallifax et al. 2019b; Klock et al. 2020). The relation of user types and sets of game elements demonstrated in the study conducted by Tondello et al. (2016) showed that the user types could be related with sets of game elements, rather than individual game elements. When we consider the way that the game elements are selected, most of the studies about personalized gamification select the game elements deliberately or by using literature reviews, which can bring some limitations (e.g., the use and random naming of game elements that are correlated, or the exclusion of a game element that would be suitable for the context) (Klock et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2020). Thus, one gap in the personalized gamification of gamified systems is studies about the preference for gamification designs (sets of game elements grouped according to their characteristics or purpose) for each user type and if they are positively affected by these gamification designs.

We tackled this challenge through a study with 331 participants, where we (1) identified their user types, (2) analyzed their preferences regarding different gamification designs (represented in storyboards), (3) measured the participants’ preference and perceived sense of accomplishment in each gamification design, and (4) analyzed the participants’ preference and perceived sense of accomplishment according to their user orientations, thus advancing toward answering the question: How are user types associated with preference and perceived sense of accomplishment in different gamification designs? Our results allow us to move toward evidence-based gamification design, generating new insights for gamification designers to create more effective gamified systems according to the users’ preferences and experiences. We also provided a series of validated storyboards to represent the design concept of personalized gamified educational system.

This article is structured as follows: In Sect. 2, we present the study background, including an overview of player/user typologies, the gamification taxonomy used to select game elements, the gameful experience and why we measured one of its dimensions, and the main related work. Following on, we describe in Sect. 3 how the study was conducted, the construction and validation of the storyboards to represent the gamification designs, the survey’s construction and application, and the main characteristics of the participants. In Sect. 4, we present and discuss the data collected and our statistical results. We also present the limitations of our study, as well as recommendations for future studies. Finally, in Sect. 5 we present the final remarks of our study.

2 Background

This section presents our study background (i.e., player/user types, gamification taxonomies, and gameful experience), as well as the main related works.

2.1 Player/user types

Throughout the years, researchers have worked on how certain characteristics may affect the user’s engagement while using a gamified system (Ferro et al. 2013) and how people can be grouped into player types (Yee 2006; Nacke et al. 2011). One of the first player type models was presented by Bartle (1996), which proposed a classification of four player types: (1) Achiever; (2) Explorer; (3) Killer; and (4) Socializer. Based on Bartle’s player types, Yee (2006) proposed an empirical model of player motivations, based on data collected from 3000 Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs). In his analysis, Yee revealed ten motivation sub-components (Advancement, Mechanics, Competition, Socializing, Relationship, Teamwork, Discovery, Role-Playing, Customization, and Escapism), which he grouped into three overarching components (Achievement, Immersion and Social).

Another player type model that has been used in researches is the BrainHex Model (Nacke et al. 2011), which was based on neurobiological findings and has seven player types: (1) Seeker; (2) Survivor; (3) Daredevil; (4) Mastermind; (5) Conqueror; (6) Socializer; and (7) Achiever. According to Nacke et al. (2011), each player type from the BrainHex model should be understood not as a psychometric type, but rather as an archetype that typifies a particular player experience.

To create a model designed specifically for gamification, Marczewski (2015) proposed the Gamification User Types Hexad, with six user types motivated by intrinsic or extrinsic motivational factors. The user type division in intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is based on the self-determination theory (SDT) that says that people are intrinsically motivated when the activity supports three basic human psychological needs (competence, autonomy and relatedness), or extrinsically motivated when the reason for doing something is not an interest in the activity itself (Deci and Ryan 1985). According to Diamond et al. (2015) and Tondello et al. (2016), the user types motivated by intrinsic motivations are the (1) Socializers; (2) Free Spirits; (3) Achievers; and (4) Philanthropists, while (5) Players are motivated by extrinsic motivations. The (6) Disruptors are not a user type derived from SDT, but from the observation of user behavior within online systems (Tondello et al. 2019).

The Hexad has been chosen for our study since it is considered the most appropriate user typology for tailoring gamification (Hallifax et al. 2019b), it does not classify the user in one specific user type (users are classified in more than one user type, with a principal tendency followed by others in some degree (Tondello et al. 2016)), and the model is empirically validated (Tondello et al. 2019), was created especially for gamification (Marczewski 2015), and has been successfully used in other recent studies (Orji et al. 2018; Lopez and Tucker 2019; Mora et al. 2019; Hallifax et al. 2020).

2.2 Gamification taxonomy

Even though there are several gamification frameworks (Azouz and Lefdaoui 2018), only a few of them are developed for the educational context (Toda et al. 2019). To help designers, teachers and instructors select and understand how game elements can be used in the educational context; Toda et al. (2019) created a gamification taxonomy composed of twenty-one game elements that could be used in gamified educational environments, organizing them in five dimensions. The Performance/Measurement dimension is related to the environment response and has the elements Point, Progression, Level, Stats, and Acknowledgement. The Ecological dimension is related to the environment that the gamification is implemented in, and is formed by the elements Chance, Imposed Choice, Economy, Rarity, and Time Pressure. The Social dimension is related to the interactions between the learners presented in the environment and has the elements Competition, Cooperation, Reputation, and Social Pressure. The Personal dimension is related to the learner that is using the environment and has the elements Sensation, Objective, Puzzle, Novelty, and Renovation. Finally, the Fictional dimension is the mixed dimension that is related to the user and the environment and has the elements Narrative and Storytelling.

As far as we know, this taxonomy is the only one that has been developed and validated for the educational context, explaining a considerable number of game elements, and grouped them into dimensions. Considering that the deliberate selection of game elements can lead to the use of different game elements with the same goal (Rodrigues et al. 2020), we decided to use Toda’s taxonomy to select the game elements for the storyboards’ design for this study.

2.3 Gameful experience

The success of gamification depends of the gameful experienceFootnote 1 the service creates in the user (Eppmann et al. 2018). Also, new generations seem to be more susceptible to having gameful experiences (Högberg et al. 2019), showing that its measurement can be an important part of the future design of gamified environments.

Högberg et al. (2019) presented a validated instrument for measuring the gameful experience users can have while using a system or a service. They also identified seven dimensions that describe the gameful experience: Accomplishment, Challenge, Competition, Guided, Immersion, Playfulness, and Social experiences. The instrument is formed of 56 questions and can be used for adaptive gamification and user-modeling research in gamification contexts.

The accomplishment dimension is defined as experiencing the demand for successful performance, goal achievement and progress (Högberg et al. 2019). Users can be motivated to complete a goal or task for the pleasure of feeling accomplished, as there is a specific type of intrinsic motivation that leans toward accomplishment (Vallerand et al. 1992; Barkoukis et al. 2008). In our study, we focused on the measurement of this dimension because it can reflect the users’ engagement and can be considered as a long-term experience that extends beyond the use of the service, which can be essential to achieving the goal of gamification (Högberg et al. 2019).

2.4 Related work

Different studies have been conducted to relate users with game elements considering gamification in general, and also in specific domains (Koivisto and Hamari 2019). Moreover, the personalization of gamification has been the object of some literature reviews conducted over recent years (Hallifax et al. 2019a; Klock et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2020). We used these literature reviews to conduct a snowballing review to find studies that have looked at how player/user typologies can be related to game elements in the educational context. In this section, we briefly discuss some of these recent studies.

Using the BrainHex typology, Monterrat et al. (2017) proposed a model and an adaptation process to gamify learning environments to increase learners’ motivation. They tested the adaptation process with 59 middle school students, where they showed that different player types have different preferences and perceptions for game elements. They also showed that increasing the game elements in an environment also increases the perceived complexity of the environment for the students. Lavoué et al. (2018) conducted an experiment with 266 participants, and according to their player types, they adapted the gamification features that were displayed in the interface of an online learning environment. Their results showed that the participants with the adapted features and counter-adapted features had similar values in their enjoyment, although the adapted features improved the participation of learners who used the environment for more time, and reduced the learners’ level of amotivation when compared to counter-adaptive gamification. Oliveira and Bittencourt (2019a) conducted an empirical experiment with 121 elementary students to identify the students’ preferences for game elements according to their BrainHex player type. Corroborating the results of Monterrat et al. (2017), they also identified that students had different preferences for the game elements according to their player type. They further suggested a guideline to design or adapt gamified educational environments based on the BrainHex player type and ten game elements. Daghestani et al. (2020) used gamification, classification, and adaptation techniques to study the impact of gamification on students’ engagement and learning. From three different groups of students (control group, gamified group, and adaptive-gamification group), they showed that the students who used an adaptive-gamified system presented a better performance than the students who used the gamified system, and that the gamification and adaptive-gamification had a positive effect on students engagement. The adaptive-gamified system was tailored based on ten game elements and BrainHex player types.

One of the first studies to use Hexad to explore the user type was conducted by Gil et al. (2015). Their study used an initial version of the Hexad (with four user types: Achievers, Socializers, Explorers, and Philanthropists) to correlate the user types with 19 game elements and 21 students’ actions in an e-learning environment. They conducted a user study with students from a 1st-year course of Computer Science, where the students could freely choose their actions in the e-learning environment. Their results showed that for all of the user types except Explorer, the students’ actions and game elements were related to the correspondent user types. Tondello et al. (2016) analyzed the correlation between the Hexad user types and 32 game elements, based on the preference of students from the University of Waterloo. Using the Hexad suggestion (Marczewski 2015), they also grouped the 32 game elements into six sets (one for each user type), analyzing the correlation with the correspondent user type. They found positive correlations between almost all the Hexad user types and the proposed game elements, except the Philanthropists. Based on their results, they created a new association table, suggesting a set of game elements for each Hexad user type. Hallifax et al. (2020) conducted a study with students from high schools, tailoring six game elements with their Hexad user types and the initial motivation user model. Considering the results of tailoring gamification based only on the Hexad user types, they found that students were more engaged in the learning task when they used game elements tailored for their user types. Furthermore, this higher level of engagement was associated with lower student performances, and their results showed that an adaptation based only on player types had no effect on learner motivation to learn Mathematics.

Even though our gamification designs demonstrated instructional content in gamified education, we did not limit the educational level of the respondents as most of the related works did (Gil et al. 2015; Tondello et al. 2016; Monterrat et al. 2017; Oliveira and Bittencourt 2019a; Daghestani et al. 2020; Hallifax et al. 2020). Also, while all of the studies featured in our related works selected the game elements based on other studies (Monterrat et al. 2017; Lavoué et al. 2018; Daghestani et al. 2020), most used in literature (Oliveira and Bittencourt 2019a; Hallifax et al. 2020), or in the suggestion of the user typology (Gil et al. 2015; Tondello et al. 2016), we selected the game elements based on a gamification taxonomy created specifically for educational environments. Except for the study conducted by Tondello et al. (2016), all of the studies only evaluated the correlation of the user types with the game elements individually. Thus, as far as we know, our study is the first to conduct an empirical study evaluating respondent preference regarding different gamification designs (a group of strategically organized game elements) in educational settings, considering a gamification-based user typology, a validated taxonomy for the education domain, and also a dimension of the gameful experience. In Table 1, we present a comparison between the related works.

3 Study design

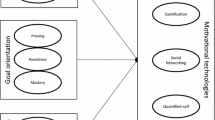

Our study aimed to identify whether the user orientations affect the preference and perceived sense of accomplishment for gamification designs in gamified systems. Thus our research question is: “How are user orientations (Philanthropist, Achiever, Socializer, Free Spirit, Player and Disruptor) associated with preference and perceived sense of accomplishment in different gamification designs (Fictional, Personal, Performance, Social and Ecological)?”. To answer our research question, we organized our study in five different steps: (1) storyboards design; (2) survey design; (3) pilot study; (4) survey application; and (5) data analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the study design.

3.1 Materials and method

Before designing our survey, we needed to decide how to present the dimensions of the gamification taxonomy in a way that the respondents could imagine how their implementation would be in a real gamified system. As recommended in recent literature in the field of human-computer interaction (HCI), a good strategy is the use of storyboards (Orji et al. 2014; Altmeyer et al. 2019, 2020; Yassaee et al. 2019). Storyboards are a graphical depiction of a narrative (Truong et al. 2006) that can be used in HCI and design to illustrate interfaces and contexts of use, thus offering designers a possibility as a prototyping technique. The use of storyboards can help users perceive and interpret proposed functionalities (Truong et al. 2006), and also help to direct the respondents’ focus (Yassaee et al. 2019). Given the benefits storyboards offer to collect user reactions to the system elements (Truong et al. 2006), that they can help with the collection of data from people with different backgrounds since they provide a visual language that facilitates user understanding (Orji et al. 2018), and that other recent gamification studies have used storyboards (Altmeyer et al. 2019; Yassaee et al. 2019; Altmeyer et al. 2020), we decided to implement five storyboards to represent each of the five dimensions proposed in Toda’s taxonomy (Toda et al. 2019).

To design the storyboardsFootnote 2, we followed the recommendations of Truong et al. (2006), which have been successfully used in recent similar studies (e.g., Orji et al. (2017); Altmeyer et al. (2019); Brenes et al. (2019)). Truong et al. (2006) determined five attributes to design a storyboard: i) Level of detail; ii) Inclusion of text; iii) Inclusion of people and emotions; iv) Number of frames; and v) Portrayal of time. Thus, we created five storyboards with six frames each, representing a fictional learning environment without defining a specific curricular component. All of the 21 game elements of Toda’s taxonomy (Toda et al. 2019) were used in the storyboards according to their dimension. Also, considering the own organization of the taxonomy to avoid overlapping, each one of the 21 game elements was represented only in one storyboard.

To ensure the storyboards quality, after the storyboards’ design, they were evaluated by three gamification experts with extensive experience in evaluating this type of technology. Two experts had six years’ experience in researching gamification, and one had nine years. To conduct the evaluation, we used a Likert scale (Likert 1932) that went from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), asking the experts about the storyboards. They had to answer the following questions: (1) “Does this storyboard represent the dimension?”; and (2)“How can we improve this storyboard?”. This last was an open question, so they could give their impressions about the storyboard and tell us how to improve it.

Our main goal in this evaluation was to guarantee that the storyboards correctly represented the five dimensions proposed by Toda et al. (2019). In their evaluation, only one storyboard got an evaluation of 1 (totally disagree) in relation to the question “Does this storyboard represent the dimension?” by one of the experts. In the other storyboards, all of them evaluated as 5 (totally agree) or 4 (partially agree) for the same question. Then, we updated the storyboards according to their feedback to the question “How can we improve this storyboard?”: the gamification experts pointed out some game elements that were present in more than one storyboard, that the use of some figures could cause a negative feeling about a prize, and offered views on how we could improve the use of the game element Competition. The storyboards and their textual description can be seen in the Appendix.

After the evaluation and improvement in the storyboards, we designed the survey. The survey was composed of 71 questions organized in three different sections. (1) Demographic information: gender, age, education degree, and gaming habits. (2) User type identification: we used the Gamification User Types Hexad (Tondello et al. 2016), thus the respondents were asked to rate how well the 24-item scale proposed by Tondello et al. (2016) represented them. We used a 7-point Likert scale (Likert 1932), the questions were presented in a random order, and respondents could not identify the corresponding type (as recommended by Tondello et al. (2016)). Inspired by other studies (Orji et al. 2018; Hallifax et al. 2019b; Oliveira et al. 2020), in this part of the survey we used an “attention-check” question: “I like to be with my friends, but this question is just to evaluate your attention. Please, mark the option number 3, to let us know that you are paying attention”. This question was to ensure that the respondents were paying attention in the survey and reading all the items.

Finally, the last section was the (3) sense of accomplishment and preference measurement. In this step, we used the sub-scale proposed by Högberg et al. (2019) to measure the perceived sense of accomplishment for each gamification design. Following Högberg et al. (2019) recommendations, the respondents were asked to rate on a 7-point Likert scale (Likert 1932) how well each of the eight statements of the Accomplishment dimension represented their feelings about each gamification design. Besides the measurement of the perceived sense of accomplishment, the last question of the survey was “Which storyboard is your favorite?”. Thus, we were able to compare the perceived sense of accomplishment with the respondent’s preference for the gamification designs.

Before launching the survey, as recommended by Connelly (2008), we conducted a pilot study to assess whether the survey was being correctly understood by the respondents, as well as to assess whether the number of questions was adequate. This pilot group answered the survey before the survey application, with the question “Is this survey large?” added at the end of the survey. The pilot study was conducted with a small sample composed by 10 participants, where 80% answered that the survey wasn’t large so we decided to not take away any questions from it.

3.2 Participants

The final survey was released on March 26, 2020, and was spread by social networks and e-mail. The survey was open for thirty-eight days and we received 366 answers, which 331 were valid according to our attention-check question. The respondents participated voluntarily, since we did not offer any kind of remuneration or gifts to the respondents. The study sample size is adequate under different aspects considering this type of study. According to the definitions of Bentler and Chou (1987) and Hair et al. (1998), it is necessary to have at least five participants for each construct measured (our study had seven constructs). Loehlin (1998) suggests a minimum sample of 100 participants for studies of this nature. Table 2 presents the demographic information of the respondents.

Table 3 summarizes the participants’ distribution by the dominant user types (i.e., the strongest tendency of the participants), the average scores, and the standard deviation for each Hexad user type. Resembling the HEXAD results of Marczewski (2020), our research identified that Philanthropist is the most common dominant user type and Disruptor is the least common dominant user type. Comparing the female and male scores in each Hexad user orientations (i.e., the tendencies of the participants), it is possible to identify that the male scores were higher than female scores in all of the Hexad user orientations.

4 Results

To ensure the instrument validation for our study, we first analyzed the data normality (using the Shapiro–Wilk test as recommended by Wohlin et al. (2012)), which showed that our data followed a non-normal distribution. Then, we measured the internal reliability for each Hexad sub-scale (user types in the survey), as well as for the perceived sense of accomplishment evaluation in each storyboard. Overall, the reliability was acceptable (\(\alpha\) \(\ge\) 0.70, RHO A \(\ge\) 0.70, CR \(\ge\) 0.70, AVE \(\ge\) 0.50) for all storyboards and user orientations, except for the Disruptors. We also measured the discriminant validity finding acceptable values, considering that the square root of the variables’ AVE value was larger than the correlations that the variable had with the other variables, and all of the variables presented correlations between them below 0.85. The reliability results are shown in Table 4, and the discriminant validity is shown in Table 5.

To answer our research question and measure the effects of the personalized gamification designs in terms of sense of accomplishment and preference, following other recent studies in personalized gamification (Orji et al. 2018; Hallifax et al. 2019b; Stuart et al. 2020), we employed the Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) analysis to identify the relation between the Hexad user types with the gamification designs (sense of accomplishment and preference), since it is a reliable method for estimate cause-effect relationship models with latent variables (Hair Jr et al. 2016). To perform the statistical analysis in our study, we used SPSS 26 software. To conduct the PLS-PM, we used SmartPLSFootnote 3 software, that provides a graphical interface to calculate PLS-PM (Wong 2013). Our complete dataset can also be found in the complementary files.

Table 6 presents the preference and perceived sense of accomplishment averages in general and by gender. It is possible to identify that the Performance gamification design is the most chosen in terms of preference and perceived sense of accomplishment.

The research model of our study is shown in Fig. 2. The results indicate that the Achiever orientation is positively associated with perceived sense of accomplishment from the Performance (\(\beta\) = 0.295***), and Social (\(\beta\) = 0.238*) designs. The Player orientation is positively associated with perceived sense of accomplishment from Ecological (\(\beta\) = 0.162*) and Social (\(\beta\) = 0.161*) designs; positively associated with preference from Personal (\(\beta\) = 0.165**) design; and negatively associated with preference from Social (\(\beta = - 0.148\)*) design. The Free Spirit orientation is only negatively associated with preference from Social (\(\beta\) = 0.150*) design. The Socializer orientation is positively associated with perceived sense of accomplishment from Fictional (\(\beta\) = 0.307***), Personal (\(\beta\) = 0.154*) and Social (\(\beta\) = 0.309***) designs; positively associated with preference from Social (\(\beta\) = 0.370***) design; and negative associated with preference from Performance (\(\beta = - 0.165\)*) design. The Disruptor orientation is positively associated with preference from Social (\(\beta\) = 0.150*) design. The Philanthropists orientation did not present any association. All of the relations are shown in Table 7.

4.1 Discussion

The goal of this study was to understand the relationship between user orientations (Achiever, Disruptor, Free Spirit, Philanthropist, Player, and Socializer) and gamification designs (Fictional, Personal, Performance, Ecological, and Social). Overall, we identified different positive and negative associations between five of the six user orientations with the gamification designs. However, we identified that there is no consistent pattern of associations.

In terms of the user type distribution, our results (see Table 3) are similar to the results of Marczewski (2020), with Philanthropist as the most common dominant user type and Disruptor as the least common dominant user type. Also, our results are similar to the results found by Tondello et al. (2019), where they identified that Philanthropist and Achiever are the prevalent user orientations and Disruptor was the one that scored lower. According to Tondello et al. (2019), women tend to score higher than men in all the user orientations with intrinsic motivations (i.e., Philanthropist, Socializer, Free Spirit, and Achiever), and even though in our results men scored higher than women in all the user orientations, the difference was smaller in the Philanthropist, Socializer, Free Spirit, and Achiever orientations (i.e., the user orientations that are motivated intrinsically).

Starting to answer our research question, considering the effects of personalized gamification designs on user orientations’ sense of accomplishment and preference (see Table 7), similar with the results found by Hallifax et al. (2019b) and Tondello et al. (2016), our results showed that Philanthropists did not present a significant association with any gamification design. Moreover, our results showed that Philanthropists presented a negative association with the Fictional gamification design in terms of perceived sense of accomplishment and preference, the only design that did not present the “assistant” that explained what the student would do in that gamification design. Since the Philanthropists are motivated by interaction with others (Tondello et al. 2016), we believe the lack of the “assistant” presence can be understood by Philanthropists as a lack of interaction.

Analyzing our results in comparison with other studies (Tondello et al. 2016, 2017a), we believe that Achievers had a strong significant association with the Performance and Social gamification designs in the perceived sense of accomplishment measurement, especially because these two designs showed game elements and situations that could lead the user to feeling achievement and to demonstrate competence, which intrinsically motivates this user type (Tondello et al. 2016). We believe that when implemented in a gamified system, the Performance (game elements: Level, Point, Progression, Stats, and Acknowledgement) and Social (game elements: Social Pressure, Competition, Social Status, and Cooperation) gamification designs would probably lead the Achievers to have a feeling of advancement in their skills, and thus motivate them.

Since Players are motivated by extrinsic rewards (Tondello et al. 2016), we believe that the significant associations with the Ecological gamification design were related to the game elements of Rarity and Economy. Orji et al. (2018) found that Players tend to be motivated by Competition and Cooperation, which can explain the positive significant association with the Social gamification design in terms of perceived sense of accomplishment. At the same time, Players presented a slight and negative significant association with the Social gamification design in terms of preference. Thus, even though the Social gamification design brought a sense of accomplishment to the Players, this gamification design was not preferred by them. Players also presented a positive significant association with the Personal gamification design, probably because the game element Puzzle (Challenge), related to this user type in other studies (Tondello et al. 2017a, 2016).

Free Spirits only presented one significant association with the Social gamification design; however, it was negative. Also, this user orientation was the one that presented more negative associations, since we were able to identify that Free Spirits presented negative non-significant associations with all of the gamification designs. Considering preference, this user orientation presented negative non-significant associations with Fictional gamification design, and considering perceived sense of accomplishment, negative non-significant associations with Personal, Performance, Ecological, and Social gamification designs. This was unexpected considering that we presented game elements in this study that were related to this user type in previous studies (e.g. Puzzle (Tondello et al. 2017a, 2016) and Level (Tondello et al. 2017a)).

Socializers were the user orientation that presented more significant associations, including a strong significant association with the Social gamification design. The game elements presented in the Social gamification design are important to ensure interactions between the users (Toda et al. 2019) and can be related directly with the Socializers that are intrinsically motivated by relatedness (Tondello et al. 2019). We understand that the Social gamification design, when implemented in a gamified system, could guide the Socializers into relatedness, which would motivate them. The game elements of the Social gamification design (game elements: Social Pressure, Competition, Social Status, and Cooperation) have already been individually associated with Socializers in previous studies (Tondello et al. 2016; Marczewski 2017; Tondello et al. 2017a). Probably, the strong significant association with the Fictional gamification design occurred because the game element Narrative is related to the user’s interaction with the system (Toda et al. 2019), and the slight significant association with the Personal gamification design because of the game element Puzzle (Challenge), that has been related with this user orientation before (Tondello et al. 2016). They also presented a slight and negative significant association with the Performance gamification design, probably because of the game elements showing progress in this gamification design, considering that similar results were found by Hallifax et al. (2019b).

We believe Disruptors presented a significant association with the Social gamification design, especially because of the game element Competition. Tondello et al. (2016) identified that competition is a game element that can be related with this user orientation, and Orji et al. (2018) showed that competition would motivate people with high disruptor tendencies. Also, the Social gamification design is the one that shows interactions with other students, and Disruptors need interactions to influence other users to try to change the system (Marczewski 2015). Hence, this can be another reason for this significant association.

Our results also presented some non-significant associations between the user orientations and the gamification designs that indicate some possibilities. As aforementioned, the Philanthropists presented a non-significant association with the Fictional gamification design. We believe that designers should guarantee that, especially when the gamified system does not present interactions with other users, they have at least a figure to simulate interaction (e.g., animated pedagogical agents or an “assistant” from the system). Considering the non-significant associations, Players presented a positive association in terms of perceived sense of accomplishment with Performance and Personal gamification designs. Since this user orientation also presented a significant association with the Personal gamification design in terms of preference, we understand that the implementation of this design would be a good option to increase the motivation of this user type. The association with the Performance gamification design could be explained by the use of the game elements Level and Point, related to this user type before (Tondello et al. 2016, 2017a). Therefore, the implementation of this design to Players also could be a good option to increase the sense of accomplishment in these users. The Disruptors presented a negative association with the Ecological, Personal, and Fictional gamification designs. The Personal and Fictional designs represented how the system would work; therefore, this could be seen by the Disruptors as the boundaries of the system. The game element Time Pressure, represented by a clock in the Ecological design, could also be seen by the Disruptors as a limitation of their actions. Since they are motivated by change (Tondello et al. 2016), we understand these designs could be understood by Disruptors as limiting, which could explain these negative associations.

Our results show that the perceived sense of accomplishment measurement has more homogeneous results than the preference measurement (see Table 6). This demonstrates that only measuring the preference for game elements might not be sufficient to understand the effects of the game elements in user experience. For instance, some user orientations presented a significant association with a gamification design in terms of perceived sense of accomplishment, but this not has happened in terms of preference with the same gamification design. Considering that the feeling of accomplishment drives the user to complete tasks or goals and reflects the user’s engagement (Högberg et al. 2019), we believe the user orientations that presented a significant association with a gamification design in terms of perceived sense of accomplishment can present better progress when using gamified systems that have that set of game elements.

When we do not consider the user orientation, the game elements of the Performance and Social gamification designs can be used for all users, since these two designs showed a predominance in the preference and perceived sense of accomplishment results (see Table 6). Thus, gamified systems must present the group of game elements that create interactions between the users, and the group of game elements that provide feedback to them.

Our results corroborate other studies (Mora et al. 2019; Hallifax et al. 2019b; Tondello et al. 2017a) showing that users have different preferences based on their user orientations. Considering only preference by user orientation, the Social gamification design is strongly related with Socializers and can also be used with Disruptors, while the Personal gamification design can be indicated for Players. Furthermore, the user orientation is a factor that affects how the users perceived their sense of accomplishment. Considering the perceived sense of accomplishment and the user orientations, the Social and Performance gamification designs are the most related to Achievers, and Socializers seems to be strongly affected by the Social and Fictional gamification designs. Philanthropists seem not to be affected by the game elements represented in this study, and Free Spirits might not be positively affected by most of the game elements.

According to our results, it is possible to select the most appropriate gamification designs for each system user, according to their Hexad user type and based on two different approaches (preference and/or perceived sense of accomplishment). This can help designers to personalize gamification, and therefore positively affect the users. To personalize gamified environments for people with higher Achiever tendencies, designers should focus on implementing the game elements from the Performance and Social gamification designs, since our results indicated a significant association in terms of perceived sense of accomplishment. The game elements from the Ecological and Personal gamification designs should be avoided since they presented a negative non-significant association. For people with higher Disruptor tendencies, designers should focus on implement the game elements from the Social gamification design, especially the game element Competition. Considering the non-significant associations this user orientation presented, if the gamified environment is based on the preference for game elements, it is important to avoid or use with caution the game elements from the Ecological, Personal, and Fictional gamification designs.

For people with higher Player tendencies, designers can focus on the game elements from the Personal and Ecological gamification designs. Since Players presented negative (preference) and positive (sense of accomplishment) significant associations with the Social gamification design, designers can give to these users the possibility to choose if they want to interact with the game elements from this gamification design. For people with higher Socializer tendencies, designers should focus on implementing the game elements from the Social gamification design, since this user type presented a significant association with this gamification design in both approaches (preference and sense of accomplishment). The game elements from the Personal and Fictional gamification designs can also be implemented to increase the experience for this user type. Game elements from the Performance gamification design should be avoided.

Since Free Spirits only presented a negative significant association with the Social gamification design, we indicate that the game elements from this gamification design should be avoided or used with caution. Considering the negative and non-significant associations this user type presented with the other gamification designs, we understand that designers could give users with high Free Spirit tendencies, a possibility to disable the game elements or to freely choose which game element each user would interact with. The Philanthropists did not present any significant association, therefore, designers can use the non-significant associations presented in our results to personalize gamified environments to this user type or also implement the possibility to disable the game elements or to freely choose which game element each user would interact with. Furthermore, we indicate that the system should provide interaction with other users or at least with the system itself, through an “assistant”. In Table 8, we summarize these recommendations of which gamification designs can be used to personalize gamified systems based on the significant associations we found (see Table 7).

4.2 Limitations

Some limitations have emerged during the study and they need to be considered. Although the internal reliability for the Disruptors was below the acceptable threshold, we were able to identify that for this user orientation, there exists a kind of predominance: all of the Disruptors, except one, presented only this user orientation as the dominant user type, and we were not able to find any study that has reported similar results. As another observation, the use of gamification designs can bring different results from the use of a real gamified system. Our design focused on representing different phases a gamified system would have, thus, they were a design concept of a gamified system. While storyboards represent the “ideal” scenario to evaluate a design idea, the implementation brings other design decisions (Orji et al. 2014), which could influence the users’ response. Also, two of the storyboards did not represent the moment the student would answer questions in the system, considering they were designed to show how a student would create a profile and also the moment that the student would know the system. Some respondents could see this as a gap, which could subsequently influence their responses in the survey.

We have sought to mitigate some of the foreseeable limitations during the conduct of the study. To mitigate the possibility that the storyboards do not represent the dimensions proposed by Toda et al. (2019), we validated the storyboards with three gamification experts before using them in the survey. The size of the survey could have led people to answer without paying attention, and to mitigate this threat, we used an “attention-check” question in the survey and eliminated the responses that did not pass this validation. As a final action, since the Hexad scale proposed by Tondello et al. (2019) and the Gameful Experience Questionnaire proposed by Högberg et al. (2019) were not empirically validated in Brazilian Portuguese, we conducted a statistical analysis to validate the answers obtained in our study to mitigate this threat.

4.3 Recommendations for future studies

Based on the results obtained in our study, as well as the limitations our study raised, it is possible to propose a series of new studies to deepen this research domain. Initially, our study focused on answering research questions in the field of education (i.e., using storyboards representing a gamified setting). At the same time, the effects of gamification may vary according to the field of application (e.g., marketing, health, addictions, and others). Thus, we believe that future studies should be conducted in different areas (i.e., replicating our study in different domains) expanding our results by using specific gamification designs suited to the context.

Almost all the respondents were older than 15 years, which can prevent the results’ generalization for younger people. We believe that future studies should focus on people under 15 years old, analyzing if the age can change the preference and perceived sense of accomplishment, thus expanding our results. Since most of the respondents had reported that they play games (67%), an interesting perspective future studies should focus on is whether the gaming habit affects the preference and perceived sense of accomplishment in gamified systems.

In our study, we chose to conduct an exploratory study which allowed us to have a broad view of the subject, without exercising control over our subjects. However, now that our results provide us with an overview of the subject, further studies must deepen the results through experimental studies in controlled environments, for example, directly comparing two gamification designs (personalized vs. non-personalized) in terms of user experiences. Therefore, we recommend that future studies should conduct experiments comparing the effects of personalized with non-personalized gamification designs in the user types.

In our study, we measured one dimension of the gameful experience (i.e., Accomplishment), and according to Högberg et al. (2019), the dimension of Immersion also seems to reflect user’s engagement. Thus, future studies can be carried out to measure this dimension. This decision to look at the Accomplishment dimension of the gameful experience was important to obtain a reliable result for a specific dimension of the gameful experience. Now that we have these results, it may be necessary to assess the effects on other gameful experience dimensions (e.g., Challenge, Competition, and Playfulness). Thus, we recommend that future studies should investigate other gameful experience dimensions.

Our results have allowed us to identify different significant (positive and negative) relationships between different user orientations and gamification designs. This means that future studies on the personalization of gamification can use these results as a basis for personalizing gamified environments. At the same time, it is also important to investigate whether the results obtained in this study are maintained in ecological environments (i.e., real gamified systems). Thus, we recommend that future studies can implement the gamification designs proposed and validated in our study in gamified systems, and evaluate the effects of different versions of the system on the users’ experience during the system usage.

Also based on the results obtained in our study, it is possible to understand which gamification designs are more or less effective concerning the users’ sense of accomplishment. This can be useful, for example, to enable gamified system designers to personalize the gamification in a way that positively affects users. To make this task easier for designers, we recommend that future research may propose recommender systems (Resnick and Varian 1997) to suggest the most suitable gamification design for each user according to their Hexad user type.

5 Concluding remarks

In this study, we presented how the six Hexad user orientations are related with five different gamification designs. To avoid the use of only the game elements that are considered the most used in research (e.g., points and badges), the game elements used in these designs were chosen from an empirically validated gamification taxonomy that groups twenty-one game elements in five dimensions. We used validated storyboards to show these dimensions to the respondents, in order to help people visualize how each dimension could be represented in a gamified system, instead of only asking about the preference for a particular dimension. Furthermore, we compared the preference with the perceived sense of accomplishment (a dimension of the gameful experience). Our results corroborate other research in identifying that the game elements presented in the Performance (Point, Progression, Level, Stats, and Acknowledgment) gamification design can be considered most adequate for all users, and that the Hexad user orientations have different preferences concerning gamification designs. Also, our results showed that the game elements presented in the Fictional (Narrative and Storytelling) and Personal (Objective, Puzzle, Novelty, Sensation and Renovation) gamification designs were the least preferred by the respondents. Our findings showed how some gamification designs can be used according to the user orientation, helping designers to design personalized gamified systems. For future studies, we intend to focus on the measurement of the other dimensions of the gameful experience, and how users that present more than one dominant user type are affected by the gamification designs.

Data availability

Original dataset available as supplementary material.

Notes

In this study, we used the definition proposed by Landers et al. (2019): “A psychological state where the user perceives non-trivial achievable goals created externally, is motivated to pursue them under an arbitrary set of behavioral rules, and evaluates that motivation as voluntary”.

The storyboards were designed at: https://www.storyboardthat.com/.

References

Altmeyer, M., Lessel, P., Muller, L., Krüger, A.: Combining behavior change intentions and user types to select suitable gamification elements for persuasive fitness systems. In: International conference on persuasive technology, Springer, pp 337–349 (2019)

Altmeyer, M., Schubhan, M., Lessel, P., Muller, L., Krüger, A.: Using hexad user types to select suitable gamification elements to encourage healthy eating. In: Extended abstracts of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems extended abstracts, pp 1–8 (2020)

Araya, R., Arias Ortiz, E., Bottan, N.L., Cristia, J.: Does gamification in education work? Experimental evidence from chile. Tech. rep., IDB Working Paper Series (2019)

Azouz, O., Lefdaoui, Y.: Gamification design frameworks: a systematic mapping study. In: 2018 6th International conference on multimedia computing and systems (ICMCS), IEEE, pp 1–9 (2018)

Bai, S., Hew, K.F., Huang, B.: Is gamification “bullshit”? evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Edu. Res. Rev. p 100322 (2020)

Barata, G., Gama, S., Jorge, J., Gonçalves, D.: Engaging engineering students with gamification. In: 2013 5th International conference on games and virtual worlds for serious applications (VS-GAMES), IEEE, pp 1–8 (2013)

Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Grouios, G., Sideridis, G.: The assessment of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and amotivation: validity and reliability of the Greek version of the academic motivation scale. Assess. Edu. Princ. Policy Pract. 15(1), 39–55 (2008)

Bartle, R.: Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: players who suit muds. https://mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm, Accessed: 2021-01-06 (1996)

Bentler, P.M., Chou, C.P.: Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 16(1), 78–117 (1987)

Brenes, A., Marín-Raventós, G., López, G.: Improving packaging design using virtual reality in the market research process. In: Multidisciplinary digital publishing institute proceedings 31, p 12 (2019)

Connelly, L.M.: Pilot studies. Medsurg Nurs. 17(6), 411 (2008)

Daghestani, L.F., Ibrahim, L.F., Al-Towirgi, R.S., Salman, H.A.: Adapting gamified learning systems using educational data mining techniques. Comput. Appl. Eng. Edu. 28(3), 568–589 (2020)

Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M.: Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. In: Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior, Springer, pp 11–40 (1985)

Diamond, L., Tondello, G.F., Marczewski, A., Nacke, L.E., Tscheligi, M.: The hexad gamification user types questionnaire: background and development process. In: Workshop on personalization in serious and persuasive games and gamified interactions (2015)

Eppmann, R., Bekk, M., Klein, K.: Gameful experience in gamification: construction and validation of a gameful experience scale [gamex]. J. Interact. Mark. 43, 98–115 (2018)

Ferro, L.S., Walz, S.P., Greuter, S.: Towards personalised, gamified systems: an investigation into game design, personality and player typologies. In: Proceedings of The 9th Australasian conference on interactive entertainment: matters of life and death, pp 1–6 (2013)

Gil, B., Cantador, I., Marczewski, A.: Validating gamification mechanics and player types in an e-learning environment. In: Design for teaching and learning in a networked world, Springer, pp 568–572 (2015)

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., et al.: Multivariate Data Analysis, vol. 5. Prentice hall Upper Saddle River, NJ (1998)

Hair, J.F., Jr., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., Sarstedt, M.: A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications, Thousand Oaks (2016)

Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J.C., Lavoué, E.: Adaptive gamification in education: a literature review of current trends and developments. In: European conference on technology enhanced learning, Springer, pp 294–307 (2019)

Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J.C., Lavoué, G., Lavoué, E.: Factors to consider for tailored gamification. In: Proceedings of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play, ACM, pp 559–572 (2019)

Hallifax, S., Lavoué, E., Serna, A.: To tailor or not to tailor gamification? an analysis of the impact of tailored game elements on learners’ behaviours and motivation. In: International conference on artificial intelligence in education, Springer, pp 216–227 (2020)

Hanus, M.D., Fox, J.: Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: a longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Comput. Edu. 80, 152–161 (2015)

Hassan, L., Jylhä, H., Sjöblom, M., Hamari ,J.: Flow in vr: A study on the relationships between preconditions, experience and continued use. In: Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii international conference on system sciences (2020)

Högberg, J., Hamari, J., Wästlund, E.: Gameful experience questionnaire (gamefulquest): an instrument for measuring the perceived gamefulness of system use. User Model. User-Adap. Inter. 29(3), 619–660 (2019)

Johnson, D., Deterding, S., Kuhn, K.A., Staneva, A., Stoyanov, S., Hides, L.: Gamification for health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv. 6, 89–106 (2016)

Klock, A.C.T., Gasparini, I., Pimenta, M.S., Hamari, J.: Tailored gamification: a review of literature. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 144, 102495 (2020)

Koivisto, J., Hamari, J.: The rise of motivational information systems: a review of gamification research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 45, 191–210 (2019)

Landers, R.N., Tondello, G.F., Kappen, D.L., Collmus, A.B., Mekler, E.D., Nacke, L.E.: Defining gameful experience as a psychological state caused by gameplay: replacing the term gamefulness with three distinct constructs. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 127, 81–94 (2019)

Lavoué, E., Monterrat, B., Desmarais, M., George, S.: Adaptive gamification for learning environments. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 12(1), 16–28 (2018)

Likert, R.: A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. (1932)

Loehlin, J.C.: Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, NY (1998)

Lopez, C.E., Tucker, C.S.: The effects of player type on performance: a gamification case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 91, 333–345 (2019)

Majuri, J., Koivisto, J., Hamari, J.: Gamification of education and learning: A review of empirical literature. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international GamiFIN conference, GamiFIN 2018, CEUR-WS (2018)

Marczewski, A.: Even ninja monkeys like to play. CreateSpace Indep Publish Platform, Charleston, Chapter User Types pp 69–84 (2015)

Marczewski, A.: The periodic table of gamification elements. https://www.gamified.uk/2017/04/03/periodic-table-gamification-elements/, accessed: 2020-08-05 (2017)

Marczewski, A.: User types hexad test results. https://gamified.uk/UserTypeTest2016/user-type-test-results, accessed: 2020-04-05 (2020)

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., George, S.: Adaptation of gaming features for motivating learners. Simulat. Gaming 48(5), 625–656 (2017)

Mora, A., Tondello, G.F., Calvet, L., González, C., Arnedo-Moreno, J., Nacke, L.E.: The quest for a better tailoring of gameful design: An analysis of player type preferences. In: Proceedings of the XX international conference on human computer interaction, pp 1–8 (2019)

Nacke, L.E., Bateman, C., Mandryk, R.L.: Brainhex: preliminary results from a neurobiological gamer typology survey. In: International conference on entertainment computing, Springer, pp 288–293 (2011)

Nacke, L.E., Bateman, C., Mandryk, R.L.: Brainhex: a neurobiological gamer typology survey. Entertain. Comput. 5(1), 55–62 (2014)

Oliveira, W., Bittencourt, I.I.: Selecting the most suitable gamification elements for each situation. In: Tailored gamification to educational technologies, Springer, pp 55–69 (2019)

Oliveira, W., Bittencourt, I.I.: Tailored gamification to educational technologies (2019)

Oliveira W, Bittencourt II, Vassileva, J.: Design of tailored gamified educational systems based on gamer types. In: Proceedings of the workshops of the Brazilian conference on computers in education. 7, p 42 (2018)

Oliveira, W., Toda, A., Palomino, P., Shi, L., Isotani, S., Bittencourt, I.I., Vassileva, J.: Does tailoring gamified educational systems matter? the impact on students’ flow experience. In: hawaii international conference on system sciences, 20 (2020)

Orji, R., Vassileva, J., Mandryk, R.L.: Modeling the efficacy of persuasive strategies for different gamer types in serious games for health. User Model. User-Adap. Inter. 24(5), 453–498 (2014)

Orji, R., Mandryk, R.L., Vassileva, J.: Improving the efficacy of games for change using personalization models. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 24(5), 1–22 (2017)

Orji, R., Tondello, G.F., Nacke, L.E.: Personalizing persuasive strategies in gameful systems to gamification user types. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, pp 1–14 (2018)

Resnick, P., Varian, H.R.: Recommender systems. Commun. ACM 40(3), 56–58 (1997)

Rodrigues, L., Oliveira, W., Toda, A., Palomino, P., Isotani, S.: Thinking inside the box: How to tailor gamified educational systems based on learning activities types. In: Brazilian symposium on computers in education (Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação-SBIE) 30, p 823 (2019)

Rodrigues, L., Toda, A.M., Palomino, P.T., Oliveira, W., Isotani, S.: Personalized gamification: A literature review of outcomes, experiments, and approaches. In: Eighth international conference on technological ecosystems for enhancing multiculturality, association for computing machinery, p 699-706 (2020)

Stuart, H., Lavoué, E., Serna, A.: To tailor or not to tailor gamification? an analysis of the impact of tailored game elements on learners’ behaviours and motivation. In: 21th International conference on artificial intelligence in education (2020)

Toda, A.M., Valle, P.H., Isotani, S.: The dark side of gamification: An overview of negative effects of gamification in education. In: Researcher links workshop: higher education for all, Springer, pp 143–156 (2017)

Toda, A.M., Klock, A.C., Oliveira, W., Palomino, P.T., Rodrigues, L., Shi, L., Bittencourt, I., Gasparini, I., Isotani, S., Cristea, A.I.: Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing gamification taxonomy. Smart Learn. Environ. 6(1), 16 (2019)

Tondello, G.F., Wehbe, R.R., Diamond, L., Busch, M., Marczewski, A., Nacke, L.E.: The gamification user types hexad scale. In: Proceedings of the 2016 annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play, pp 229–243 (2016)

Tondello, G.F., Mora, A., Nacke, L.E.: Elements of gameful design emerging from user preferences. In: Proceedings of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play, pp 129–142 (2017)

Tondello, G.F., Orji, R., Nacke, L.E.: Recommender systems for personalized gamification. In: Adjunct Publication of the 25th conference on user modeling, adaptation and personalization, pp 425–430 (2017)

Tondello, G.F., Mora, A., Marczewski, A., Nacke, L.E.: Empirical validation of the gamification user types hexad scale in english and spanish. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 127, 95–111 (2019)

Truong, K.N., Hayes, G.R., Abowd, G.D.: Storyboarding: an empirical determination of best practices and effective guidelines. In: Proceedings of the 6th conference on designing interactive systems, pp 12–21 (2006)

Turan, Z., Avinc, Z., Kara, K., Goktas, Y.: Gamification and education: achievements, cognitive loads, and views of students. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 11(07), 64–69 (2016)

Vallerand, R.J., Pelletier, L.G., Blais, M.R., Briere, N.M., Senecal, C., Vallieres, E.F.: The academic motivation scale: a measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 52(4), 1003–1017 (1992)

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., Höst, M., Ohlsson, M.C., Regnell, B., Wesslén, A.: Experimentation in Software Engineering. Springer, Berlin (2012)

Wong, K.K.K.: Partial least squares structural equation modeling (pls-sem) techniques using smartpls. Mark. Bull. 24(1), 1–32 (2013)

Yassaee, M., Mettler, T., Winter, R.: Principles for the design of digital occupational health systems. Inf. Organ. 29(2), 77–90 (2019)

Yee, N.: Motivations for play in online games. CyberPsychol. Behav. 9(6), 772–775 (2006)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the grant provided by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Projects: 2018/07688-1, 2020/02801-4, 2016/02765-2, and 2018/15917-0; Academy of Finland Flagship Programme under Grant No. 337653 (Forest-Human-Machine Interplay (UNITE)); and Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Funding

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ACGS took part in conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. WO involved in conceptualization, methodology, supervision, formal analysis, validation, writing—review & editing. JH participated in supervision, validation, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. LR involved in writing—review. AMT participated in writing—review. PTP took part in writing—review. SI involved in supervision, writing—review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This manuscript has not been submitted to, nor is under review at, another journal or other publishing venue. The authors have no affiliation with any organization with a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, A.C.G., Oliveira, W., Hamari, J. et al. The relationship between user types and gamification designs. User Model User-Adap Inter 31, 907–940 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-021-09300-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-021-09300-z