Abstract

The current progressive increase in urbanisation is a contributing factor to the alarming rate of decrease in biodiversity worldwide, so it is critical to propose new solutions that bring nature, and their associated benefits, back to cities. Urban ponds and pondscapes are potential Nature-based Solutions that play a crucial role in the conservation and promotion of biodiversity, as well as providing other ecosystem services. Therefore, it is important to understand people's perception of the contribution that these ponds/pondscapes make in their daily lives. The aim of this study was to assess public perception of the value of the multiple ecosystem services, here referred to as Nature's Contributions to People (NCPs), provided by urban ponds with a focus on biodiversity. To achieve it, we conducted a face-to-face questionnaire survey among 331 visitors of urban parks and nature reserves in a medium-sized European city (Geneva, Switzerland). The results show that people highly value the different contributions provided by urban ponds, and that contact with nature is the main motivation for visiting urban pondscapes. Their positive view about the provided NCPs and also their acknowledgement of an improved quality of life suggest a public acceptance of these ponds. We also found that gender and income do not influence public perception of the contributions provided by urban pondscapes. Additionally, the biodiversity of urban ponds was highly appreciated, but there was a knowledge gap relating to biodiversity conservation, as both native and exotic species were valued equally. In conclusion, ponds are Nature-based Solutions that are very well adapted and accepted in cities, and in the future they should be part of the greening (and blueing) of urban planning to conserve and enhance freshwater biodiversity whilst also providing NCPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Currently, more than half the world’s population lives in cities, and this number is expected to increase to two-thirds by 2050 (UN DESA 2018). This global trend coupled with greater densification in cities and thus a greater need to improve the quality of life of their inhabitants. Associated with climate change, the increasing urbanisation has affected ecosystem dynamics, leading to a change in land use, an impact on freshwater availability, and a decline in biodiversity, resulting in a reduction in the human quality of life (McKinney 2006; Wilby and Perry 2006). The decline in biodiversity results in a significant decrease in ecosystem services and people’s quality of life, has a negative impact on the food and materials supply chain and access to water (Chapin III et al. 2000; Díaz et al. 2006). Additionally, this leads to an increase in diseases and epidemics, vulnerability to natural disasters, among other issues that further jeopardise human life on earth (Schmeller et al. 2020).

Cities can support biodiversity conservation and ensure the survival of endangered species. This can be achieved by increasing and raising awareness of green and blue spaces, restoring native species of flora and fauna, and creating biodiversity-friendly habitats within urban spaces (Botkin and Beveridge 1997; Beninde et al. 2015; Shaffer 2018). It is therefore extremely important to manage cities for both human well-being and biodiversity in an optimal way. One of the innovative solutions proposed during the last two decades to bring nature into cities is the creation of ponds. These small waterbodies have well-known functions of preventing flooding by stormwater runoff and also to bring an aesthetic and educational value to urban landscapes (parcs, gardens). The networks of ponds (i.e., pondscapes) can also potentially have a crucial role in the conservation and promotion of biodiversity and ecosystem services in urban areas (Bastien et al. 2012; Oertli and Parris 2019).

A pond is an inland freshwater body with a surface area of 1 m2 to 5 hectares and a maximum depth of 8 m. It supports environmental connectivity and biodiversity (Oertli et al. 2005; Persson 2012). A large proportion of existing ponds are today linked to human activities and are artificial (Oertli 2018). A pondscape is a network of ponds connected biologically, i.e. with exchanges of plant or animal species, and their surrounding matrix (see also Boothby 1997). Constructed ponds or pondscapes, particularly in cities, represent Nature-based Solutions (NBS) (Cuenca-Cambronero et al. 2023; Oertli et al. 2023) as they are “solutions that are inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience” (Dumitru and Wendling 2021). Indeed, urban ponds and other artificial ponds, offer collectively a diversity of Nature's Contributions to People (NCPs) or Ecosystem Services (ES), including a habitat for biodiversity (Cuenca-Cambronero et al. 2023). Since the term ES has been mainly used in an economic perspective, the nomenclature NCPs was created to be more inclusive from social sciences perspective (Díaz et al. 2018). For clarification, we will use the term NCPs in this paper.

Biodiversity appears to be well-represented in ponds in cities despite the multiple urban anthropic pressures, such as pollution, lack of connectivity and mismanagement (Hassall 2014; Oertli and Parris 2019). Several case-studies have highlighted the importance of promoting diversity in urban ponds, for example for dragonflies (Goertzen and Suhling 2013; Simaika et al. 2016). They have found that urban ponds enhance people's experience of green space because dragonflies are appreciated for their colour and high visibility. Ngiam et al. (2017) highlighted in London (UK) the socio-ecological relationship between humans, ponds, and dragonflies. Other investigations have shown that vegetation characteristics and abundance can affect public preference for urban wetlands in Victoria (Australia), Minnesota (USA), and Sapporo (Japan) (Asakawa et al. 2004; Nassauer 2004; Dobbie 2013).

The interaction of population with urban nature has been extensively described by several studies (Nordh et al. 2011; Paul and Nagendra 2017). For instance, enquiries made among citizens evidence that nature in cities (e.g., parks, urban forests, stream corridors) is linked to physical and psychological experiences, aesthetics, recreation and leisure, human well-being and health (Matsuoka and Kaplan 2008). Recreational use, participation, nature and landscape, sanitary maintenance, and water safety were among important factors identified by the public (Asakawa et al. 2004). Urban ponds seem also to benefit of a generally positive view from citizens, related mostly to their aesthetic aspect, as evidenced by several social surveys (Hassall 2014). Additionally, these ponds contribute to nature-culture interactions, adding local distinctiveness, therefore being involved in people's sense of place and neighbourhoods’ identity (Gledhill et al. 2005).

Highlighting the cultural values offered by wetlands, which are high near residential areas, is important to encourage the creation of wetlands in cities (Pedersen et al. 2019). Social participation is an extremely important tool to be used in the management and creation of urban ponds as it helps to accept, conserve, design and improve them for the benefit of more people (Jones 1999; Lamond and Everett 2019). Such social engagement is also reported in a survey in three public parks in Geneva (Meilland 2018). It highlighted the benefits of ponds for visitors' well-being, biodiversity and aesthetics, and encouraged the creation of new, more natural-looking ponds in the city.

However, past investigations also show that there is still a need for more information with regards to understanding how people perceive and accept the values of the NCPs offered by the urban pondscape. Specifically, there are open questions remaining: (i) How are the NCPs, and especially the biodiversity, provided by urban ponds perceived by visitors? (ii) Do the public feel an improvement in their quality of life through the presence of an urban pond? (iii) Is there a difference in the public perception of the NCPs provided by urban ponds compared to more natural ponds (e.g., rural pondscape)? (iv) Do gender or income have any influence on visitors’ perception of an urban pondscape?

These questions constitute the aim of this study which was carried out in Geneva (Switzerland), a medium-sized European city. We conducted a face-to-face questionnaire survey among 331 visitors of three urban parks and of two rural natural reserves.

Material and methods

Study sites

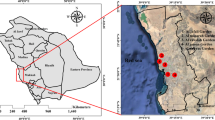

The study was conducted in western Switzerland, Canton of Geneva, which include an urban area and a rural area hosting more than 200 ponds (Oertli et al. 2018). The urban area is the city of Geneva, capital of the Canton of Geneva, with an area of 16 km2 and a population of over 204,000 inhabitants, it is the second largest and the second most populous city in Switzerland. About 75% of the city is composed of building and transportation areas, and about 19% are wooded and recreational areas (FSO 2020). Due to the high density of buildings, urban ponds are mostly small in surface area (mean surface area of about 100 m2).

The survey was carried out in three urban parks - Parc des Franchises, Jardin de la Paix, and Parc Bertrand - and in two rural nature reserves - Moulin-de-Vert and Bois des Mouilles – (Fig. 1 and Table 1). These urban parks and rural nature reserves were chosen because they have at least one pond, they are well known to the public and therefore receive significant numbers of visitors. The natural ponds differ from the urban ponds in their naturalness, as (i) they are located in a rural or peri-urban environment, with a low degree of urbanisation in a 2 km radius (i.e. < 13% or < 26% of impervious surfaces for the urban and peri-urban areas, respectively), and (ii) the ponds and their buffer area lack artificial structures (no concrete surfaces).

Canton of Geneva (black region in the upper left map of Switzerland) and the location of the three public urban parks in the urban pondscape (urban environment) and two rural nature reserves in the rural pondscape (peri-urban and rural environments) where social surveys were conducted. The pictures of each location are identified by numbers from 1 to 5 at the bottom of the figure. The urbanisation gradient is represented from urban to rural areas (shown by different colours), characterised by the proportion of impervious surface in a 2 km radius (< 13%, 13 to 26%, 27 to 39%, > 39%, for rural, peri-urban, sub-urban and urban areas, respectively)

Data collection and analysis

The data used in this study were collected from face-to-face interviews through a questionnaire survey of visitors of the urban parks and the nature reserves. The surveys were collected during the peak visitor months of June to August 2022 between 09:00 and 18:00 on days with good weather conditions, giving a total of 31 collection days and 331 interviews. The research was conducted by the same person (by the first author of this paper), with visitors randomly chosen in the proximity of ponds. Before starting the interview, the research description, confidentiality and assurance of anonymity were provided verbally.

The questionnaire consisted of 14 easy-to-understand questions (13 closed questions and one optional open question) to be completed within 10 min (see Appendix A). The questions were formulated to assess the perception of the population of the ecosystem values offered by Swiss urban ponds. The questionnaire was divided into four sections, addressing questions on: (i) frequency of visits to ponds and motivations of visitors, (ii) assessment of contributions provided by ponds (NCPs), (iii) pond features and facilities, and (iv) interviewee profile (some sociodemographic factors). For the questionnaire, we identified a list of 10 NCPs from the 18 NCPs proposed in the IPBES report 2019 (Díaz et al. 2019), that were selected for their relevance in our study. These 10 NCPs were renamed, slightly adapted or divided into sub-categories to reflect the local context and to make them easier for respondents to understand (see Table 2). For clarity, the 12 categories of NCPs as named in the third column of Table 2 will be used throughout the paper. The 12 NCPs were listed in question number 6 of the questionnaire (see Appendix A) and set to be measured on a 5-point Likert scale. In the analysis of question 6 “I don't know” answers were not considered. It is important to highlight that certain pond-related disservices, such as mosquitoes, frog noise, and child safety concerns, were reported by citizens in some areas of the Canton of Geneva, however they did not concern the studied ponds.

Questions 6, 3, 7 and 8 of the questionnaire (Table 3) were analysed to investigate whether the public identifies biodiversity as an important NCP offered by urban ponds. However, for question 8, in the choice of answers, we didn’t make a difference between native and exotic species to prevent bias.

Question 5 and 6 (Table 3) were used to investigate whether urban ponds provide an improvement in people's quality of life and to explore their public acceptance through NCPs assessment.

Question 6 (Table 3) was explored to investigate whether there was a difference in public perception of the NCPs provided by urban and rural pond landscapes (hypothesised to be lower for urban ponds). The rural pondscape (comprises the two nature reserves in the peri-urban and rural environments) with 43 interviewees, while 288 in the urban pondscape (comprises the three parks in the urban environment), was underrepresented and was used for comparison purposes in this study.

Questions number 6, 5 and 7 (Table 3) were used to discover whether gender (female and male) or income (low and high) has any influence on the public perception of the NCPs provided by the urban pondscape.

The completed questionnaires were manually entered into a LimeSurvey database (http://www.limesurvey.org) that we developed for this study. The data analysis was carried out with Microsoft Excel (Excel®) for descriptive statistics, and with Minitab statistical software (MINITAB®) for inferential statistics using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with subsequent Tukey’s post-hoc, T, χ2 and 1-Proportion tests.

Profile of interviewees

In total, 331 voluntary visitors were interviewed, 288 in the urban pondscape and 43 in the rural pondscape. The age of visitors, from 18 upwards, was divided into five groups. The group between 35 to 49 years old represented the largest sample, 29%, followed by the 25–34 age group (21%), the 18–24 group (18%), the group over 65 years old (17%), and the 50–65 group (15%). The gender of the interviewees was very homogenous with about 50% being female and 50% male. With regards to income, about 21% of the interviewees declared themselves to be low income, 41% medium income, 25% high income, and 13% did not want to say. With regards to the place of residence of the 288 visitors to the urban parks, 53% live near the urban park (up to 2 km from the urban park) and 47% further away (more than 2 km from the urban park). A table with details on the interviewees profile is presented in the Appendix B.

Results

How are the NCPs, and especially the biodiversity, provided by urban ponds perceived by visitors?

To find out whether the public identifies biodiversity as an important NCP offered by urban ponds, we analysed the responses to questions 6, 3, 8, and 7 of the questionnaire (see Table 3) among 288 visitors in three urban public parks.

Among 12 NCPs, interviewees identified biodiversity as the most important NCP offered by urban ponds (Fig. 2). The NCP “biodiversity” had the highest mean score (4.39 in a maximum scale of 5), however, there was no significant statistical difference with the five following best scored NCPs: “learning & inspiration”, “aesthetic”, “maintenance of options”, “pollination”, and “refreshing" (Tukey's ANOVA test; p > 0.05). The NCPs identified with the lowest importance were “fire prevention” and “flood prevention”, with mean scores of 3.41 and 3.47, significantly lower than most of the other scores (p < 0.05). See Appendix C for the detailed results of the statistical tests.

Public perception of the importance of 12 NCPs provided by Geneva's urban pondscape, represented by the mean score (± CI 95%), according to 288 interviewees. Five-point scale ranging from 1 = “not important at all” to 5 = “extremely important”. ANOVA (p < 0.05). The grouping according to Tukey’s post-hoc test (differences with p > 0.05) is indicated by the letters A to G (means not sharing any letter are significantly different)

The main motivation that leads interviewees to visit urban parks is “contact with nature”, followed by “leisure”, “landscape/aesthetics”, and “the local biodiversity of flora and fauna” (Fig. 3). We also investigated whether the place of residence, near the urban park or further away, influences the motivations to visit the urban pondscape. The top three motivations remain the same, with the fourth motivation being "the local biodiversity of flora and fauna” for people who live in the region and “facilities available on site” for people who do not live in the region. We can also conclude from these results that “landscape/aesthetics”, “the local biodiversity of flora and fauna”, “practicing sport”, and “the pond” are more important for people who live in the region than for those who do not (significant differences; χ2: p = 0.0011; 1-Prop Test: p < 0.01; i.e., Appendix C).

Motivation of interviewees for visiting Geneva's urban pondscape (n = 288 interviewees). The number of answers is divided into two groups based on the location where interviewees live: within the region of urban parks (n = 152) and outside this region (n = 136), with information on potential significant differences (χ2: p = 0.011; 1-Prop Test: *for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01 and ns for p > 0.05; see Appendix C). Note that each person could choose up to 4 reasons from the list

Concerning the role of urban ponds for the conservation and protection of threatened biodiversity in Switzerland, all visitors expressed a certain level of importance (none was 0%), with the importance qualified as high or very high for 79% of the interviewees (Fig. 4).

The 5 features most appreciated in urban ponds by the 288 interviewees are, in decreasing order of importance, “presence of frogs”, “presence of ducks and other water birds”, “trees and associated shading”, “presence of dragonflies”, and “presence of fishes” (Fig. 5). All these ponds’ features are directly linked to biodiversity, with four of them connected to aquatic biodiversity. Among amphibians, a group typical of ponds, the presence of toads was clearly not appreciated (7%) contrarily to frogs (49%). The frogs that were present in these urban ponds, and were appreciated, were mainly represented by Pelophylax sp., an invasive non-indigenous group of species. Toads were represented by Bufo bufo, a native species, listed as vulnerable on the Swiss red list.

Do the public feel an improvement in their quality of life through the presence of an urban pond?

To investigate if the presence of an urban pond leads to an improvement in people's quality of life, we analysed the answers to question 5 of the questionnaire (see Table 3) for 288 visitors in three urban public parks in the city of Geneva.

The clear majority of interviewees (71.2% of the total number) expressed that urban ponds make a high or very high positive contribution to their quality of life (Fig. 6). The people who live near the park hosting the pond were much more sensitive to this point and provided the majority (64%) of responses expressing a “very high” benefit (significant difference with the people leaving further away; 1-Prop Test: p = 0.006).

Contribution of an urban pond to the quality of life of 288 interviewees. The number of answers is divided into two groups based on where interviewees live: within the region of urban parks (n = 152) and outside this region (n = 136), with information on potential significant differences (χ2: p = 0.012; 1-Prop Test: *for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01 and ns for p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C)

Is there a difference in the public perception of the NCPs provided by urban ponds compared to more natural ponds?

To find out if there is a difference in the public perception of NCPs provided by urban and rural pondscapes, we compared the results of question 6 of the questionnaire (see Table 3) conducted among interviewees in three urban public parks (n = 288) with the results collected in two rural nature reserves (n = 43).

Interviewees mostly did not express a difference in the importance of a given NCP provided by urban ponds, compared with the same NCP provided by more natural (rural) ponds. For 10 of the 12 considered NCPs, there was no statistical difference (T-test: p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C) (Fig. 7). Interviewees identified a difference (p < 0.05) only for the two NCPs “flood” and “fire prevention”, considered as less important in the urban area. Nevertheless, considering all 12 NCPs, the scores attributed to each of them were always higher for natural ponds. Globally, a higher score is attributed to rural ponds (mean = 4.20), if compared with urban ponds (mean = 4.02).

Public perception of the 12 NCPs provided respectively by urban and rural pondscapes in the Canton of Geneva, represented by the mean values of the score (five-point scale ranging from 1 = “not important at all” to 5 = “extremely important”). The number of interviewees of urban and natural pondscapes are 288 and 43, respectively (T-test: *for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and ns for p > 0.05; See Appendix C)

Does gender or income have any influence on perception of pondscape?

In order to find out if gender (female and male) or income (low and high) has any influence on the public perception of NCPs provided by urban pondscape, we separated the answers collected in three public parks in the urban area of Geneva (n = 288 interviewees) by genders (145 males, 143 females). We also extracted the two most contrasted classes of income (61 low-income, 71 high-income).

Gender

The perceptions of the importance of each of the 12 NCPs provided by the urban pondscape were all statistically similar for female and male (T-test: p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C) (Fig. 8). Nevertheless, if all 12 NCPs are considered globally, females attributed a higher score to all NCPs (mean = 4.18) compared to males (mean = 3.87).

Public perception according to gender of 12 NCPs provided by Geneva's urban pondscape, mean values and standard deviations. Five-point scale ranging from 1 = “not important at all” to 5 = “extremely important”. The sample sizes of females and males are 143 and 145, respectively. There are no statistical differences for all 12 pairs of answers (T-test: p > 0.05)

With regards to the perception of the urban pond's contribution to quality of life by gender, 73% of the female and 70% of the male groups agreed that the contribution was high or very high (no significant differences; χ2: p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C).

Concerning the role of urban ponds for the protection of threatened biodiversity in Switzerland according to gender, a higher proportion of females (85%) ranked the importance as high or very high, compared to males (73%) (no significant differences; χ2: p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C).

Income

Considering the different income levels, the perceptions of each of the 12 NCPs provided by the urban pondscape were statistically similar (T-test: p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C) (Fig. 9).

Public perception, according to high and low income, of the 12 NCPs provided by Geneva's urban pondscape, mean values and standard deviations. Five-point scale ranging from 1 = “not important at all” to 5 = “extremely important”. The number of interviewees of high and low incomes are 71 and 61, respectively. There are no statistical differences for all 12 couples of answers (T-test: p > 0.05)

In context of the contribution of these urban ponds towards the quality of life, according to income, 76% high-income and 69% low-income groups agreed the contribution qualified as high or very high (no significant differences; χ2: p > 0.05; i.e., Appendix C).

On the role of urban ponds for the protection of threatened biodiversity in Switzerland, both income categories (86% high-income and 77% low-income) expressed high or very high importance to the issue. No statistically significant differences were found (χ2: p > 0.05; See Appendix C).

Discussion

Perception of the benefits offered by an urban pond

In this study, the citizens recognise and value the multiple benefits that urban ponds offer. Indeed, when scoring (from 1 to 5) the 12 NCPs, the 288 interviewees always rated them above average (3.41 was the lowest score). This is in agreement with other studies where people acknowledged the benefits provided by urban ponds and wetlands (Manuel 2003; Nassauer 2004; Scholte et al. 2016; Ngiam et al. 2017). Furthermore, the presence of an urban pond was found in our study to contribute positively to people’s perceived quality of life. People living in the region of the urban pond were particularly sensitive to this point and they perceived an even greater contribution to their quality of life (80%) than people who live further away (61%).

The positive assessment of the public about the NCPs provided by urban ponds, as well as their acknowledgement of an improved quality of life, suggest a public acceptance of these ponds. This is important, as the creation of ponds as NBS requires the public acceptance of these spaces for their long-term success (Giordano et al. 2020; Anderson and Renaud 2021). Additionally, it can be seen as an incentive for the development of public policies and programs to ensure the preservation and restoration of urban ponds.

The question of acceptance also relates to the freedom to roam as a right of public access to wilderness. In an urban context, wilderness is not relevant because nature is seen historically as something to be tamed and conquered. But pond creation and access to ponds is fully in tune with the right to the city (Lefebvre 1967), as a proposal to reclaim the city as a co-created space. Therefore, the restoration and creation of urban ponds merits special attention by allowing the provision of NCPs as connection of people to nature as well as other contributions (habitats for biodiversity, small thermal effect in climate-responsive design practice (Jacobs et al. 2020), aesthetic appeal).

Improving the social acceptance of new ponds in urban areas presupposes taking into account the diversity of people that live in cities. Indeed, our study has shown that 47% of visitors live outside the urban park area. The unbalanced spatial distribution of urban parks could result in different perceptions between visitors and local residents, and possibly requires a public planning strategy and zoning that distribute ponds spatially, including in the most deprived areas of cities.

The high contribution of ponds to quality of life as perceived by people living in the park region demonstrates that the proximity of these natural areas has a significant impact. This is undoubtedly due to the greater possibility of contact with these blue spaces (leading to a higher frequency of connection with nature, psychological benefits, recreational opportunities, etc.). However, it is important to mention that this difference in perceived quality of life between people living near and far from the studied urban pond does not necessarily mean that the pond is the only contributing factor. Other factors, such as maintenance of the park, easy access and other green habitats present in the park may play an important role in the general perception of quality of life.

Urban ponds are valuable spaces that can be used as tools to improve the quality of life of people in cities and to promote environmental sustainability. The highly positive recognised value of urban ponds in this study is a strong encouragement for the continued preservation, enhancement, and integration of urban ponds into the framework of urban planning and design, further strengthening their status as valuable assets for present and future generations.

Comparing perceptions of urban ponds and more natural ponds

Overall, we observed that the interviewees thought urban ponds were of slight lower value than rural ponds. Nevertheless, if considered individually, a similar importance was recognised for most of the NCPs (10 from 12) delivered by both types of ponds. Interviewees identified that ponds in rural pondscapes were more important for the regulation of flooding and fire events than urban ponds. This is in line with the fact that rural ponds were clearly larger in terms of surface area: they have therefore a higher capacity for buffering water runoff during storm events, and also the water can be used by firefighters to extinguish forest fires. The perception of a slightly lower value of the urban ponds compared to the rural ponds is without doubt also linked to many particular features characterising urban ponds: artificial structures (e.g., artificial substrate and shorelines, barriers around the pond, fountain, public benches), a lower surface area, and the high public attendance (Oertli and Parris 2019). It is worth noting that as urban pondscapes are important areas adapted for human use, some environmental factors in these areas can be easily controlled and modified with good management.

The importance of urban ponds for biodiversity as highlighted by public perception

The public interviewed in the Canton of Geneva was aware of the importance of urban ponds for biodiversity, as this NCP was identified as the most important NCP provided by ponds. Furthermore, a high level of importance for the conservation and protection of threatened biodiversity was recognised. Notably, 79% of interviewees who expressed their opinion scored the importance of biodiversity as high or very high of urban ponds for the preservation of threatened biodiversity in Switzerland. The fact that "landscape/aesthetics”, and "the local biodiversity of flora and fauna” were among the main motivators that leads interviewees to visit the urban pondscapes studied further provides evidence that visitors have a high awareness of the importance of the ponds and pondscapes for biodiversity.

The challenge of conciliating pond ecological quality with users’ perceptions (Hassall et al. 2016; Martin et al. 2016) is important for site managers. The fact that the interviewees were aware of the pond’s importance given to biodiversity conservation, indicates a positive perception, and therefore an opportunity to strengthen public perception of the importance of these spaces as key areas to preserve biodiversity in the urban environment. It could be a motivating factor for the local community to become more engaged in the preservation and conservation of these ecosystems (Sterrett et al. 2019), creating plans and strategies to preserve and restore these natural spaces within cities, and taking part in environment education program by understanding the threats and cause of extinction of some species (Jarić et al. 2020).

The contact with nature was emphasised by the respondents, showing the necessity to integrate green and blue spaces in urban environments to reverse the ongoing trend towards dissociation between people and nature (Soga and Gaston 2016), and improving the inhabitants’ quality of life. Thus, it reflects the basic human need (Seymour 2016; Baxter and Pelletier 2019) to be connected with nature because of the physical and mental health benefits resulting from it. This is supported by several previous studies (Hart 2019; Vandergert et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021) which show that contact with nature provides an opportunity to divert negative emotions, increase attention span and reduce the effects of stress. The maintenance or the improvement in quality of life supposes that people have access to ponds and find the most propitious conditions in terms of aesthetic preference (Dobbie 2013; Hayden et al. 2015; Arnberger et al. 2021), refreshing space in summer and the range of facilities required for visitors (Parker and Simpson 2018; Liu and Xiao 2021).

To promote pond conservation and raising awareness about their biodiversity, it may be helpful to identify flagship species (Sousa et al. 2016). Urban ponds were here essentially appreciated for the aquatic biodiversity observed by the interviewees. Aquatic wildlife was cited as a priority, in particular the presence of frogs, water birds, dragonflies, and fish. It should be noted that most interviewees valued biodiversity and at the same time enjoyed the presence of exotic species (such as the introduced fishes, ducks, and frogs) or even invasive species (mostly Pelophylax frogs) that may in fact constitute one of the main threats to native biodiversity (e.g., to other amphibian species, dragonflies or plants). From this result, it is possible to infer that the public has little to no knowledge about the national or international strategies for biodiversity conservation. Due to this lack of information, the public itself is prone to continue accepting or even encouraging exotic species, which are generally very colourful (e.g., mandarin duck, gold fishes, exotic water lilies) and draw public attention. Previous studies have already highlighted this gap in biodiversity knowledge, with people generally having also poor biodiversity identification skills (Dallimer et al. 2012).

This low level of knowledge on biodiversity conservation among interviewees raises questions concerning strategies for the conservation of ponds (Hill et al. 2018). The perception of what makes an ‘attractive’ and ‘natural’ pond varies among the study population (Hoyle et al. 2019), their backgrounds, their location and their level of knowledge. Human preferences can therefore represent an obstacle to the implementation of pond restoration, depending on its objective. This brings to the fore the need to reconcile the local expectations with the scientific requirements of pond restoration (Oertli et al. 2010). A potential solution would be to improve the multifunctionality of the ponds or to promote ponds with diverse uses in a same pondscape. Multifunctional ponds are indeed extremely important for biodiversity in the urban environment (Hassall 2014; Oertli and Parris 2019). They can prevent flooding, contribute to carbon storage, microclimate, water purification and provide opportunities for recreation, learning and inspiration for people (Alikhani et al. 2021; Krivtsov et al. 2022). The creation and restoration of urban ponds in line with local expectations and scientific requirements is a political decision that could change the functioning of ponds, the habitats for species, the relation between ponds and visitors and the current trade-offs in pond management (Faith and Walker 2002; Hambäck et al. 2023) with potential conflicts (land use, rampant urbanisation, waste water etc.). Therefore, it is crucial to have an efficient management of urban ponds to provide ongoing benefits to the population and biodiversity (Shrestha et al. 2021). This requires information on the different NCPs and individual preferences of the local community to provide a comprehensive overview to underpin recommendations to decision-makers.

Influence of proximity of residence on the motivation to visit the urban park

The influence of people's proximity of residence on the motivation to visit urban parks is an important aspect to be considered in the creation and planning of these spaces. According to our results, people who live close to the park seem to value more the biodiversity of flora and fauna, the practice of sports and the presence of a pond compared to those who live further away. Based on this observation, the creation of a pond in a new or in an existing urban park (currently without a pond) can be an effective strategy that ensures accessibility for all neighbourhoods and promotes an urban environment that is more inclusive and aligned with the motivations of residents. Urban ponds offer multiple benefits including opportunities for outdoor activities, enriched biodiversity, and environmental improvements such as microclimate regulation and water filtration, fostering a more diverse ecosystem in the urban park and in the surrounding region. However, it is essential that the development of new urban parks and the presence of ponds is done with careful consideration of ecological, safety and sustainability dimensions. It is important to involve experts in urban planning, environmental conservation and public participation to ensure these parks meet community needs and desires (including caveat and reduction of disservices) while preserving and protecting natural resources. In this way, the creation of new urban parks with ponds can offer significant benefits for the well-being of people and the conservation of the environment.

Gender and income effects on visitors’ perception of urban pondscape

In contrast to other studies that showed that social factors can influence the perception and use of public spaces (de la Barrera et al. 2016; Schüle et al. 2017), no relationship was found in this study between the gender and income social factors and the perception of the contributions provided by urban ponds. Our results then suggest that people of different genders and incomes have a similar positive perception of the contributions provided by urban ponds. Male and female both stressed the importance of the NCPs provided by urban ponds, and especially biodiversity. The consensus among gender and incomes is important in ensuring that these spaces are accessible and valued by a variety of individuals. It can be seen as an opportunity to create blue and green spaces that promote equity and inclusion for all individuals regardless of their socio-economic background. It is worth noting that further studies regarding these socio-demographic factors are needed to grasp if pond are attractive to the local community as they increase the value of a particular area, contributing to the phenomena of gentrification (Anguelovski et al. 2022).

Conclusion

For an increasingly urbanised society and a busy urban environment, integrating and promoting blues spaces, such as ponds, is a way to minimise the effects of strong urban pressure on the environment and biodiversity, while improving the quality of life of the population. This can lead to more sustainable cities and greater connections of people with nature.

As demonstrated in our study, public perceptions of urban ponds can provide interesting insights into the role of these small water bodies, their importance and public preferences. There is evidence that urban ponds are widely valued by the citizens because of their benefits for quality of life and the provided NCPs, as well as being important spaces for contact with nature. The biodiversity represented in these ponds is also highly valued by the public, who expressed their importance for the conservation and protection of threatened species. However, there was a clear gap in public knowledge about the conservation of biodiversity, with the presence of exotic and often invasive species being accepted and even welcomed. This stresses the importance of environmental education, and urban ponds could constitute an important tool (knowledge of species, understanding of the functioning of an ecosystem, and of the impairment through urban pressure). It is important to understand people's perception of the contributions of urban ponds in order to accept, conserve, design, manage and improve them for the benefit of more people, thus contributing to their sense of belonging and quality of life. In light of this, conservation and maintenance actions should be taken to ensure that these urban ponds continue to play a key role in biodiversity conservation, improving people's lives, and inclusiveness. Furthermore, it is important to promote public awareness about biodiversity conservation and the benefits of urban ponds.

In conclusion, ponds are Nature-based Solutions very well adapted and accepted in cities, and they should in the future be part of the greening (and blueing) in urban planning to conserve and enhance freshwater biodiversity whilst also providing NCPs.

For future research on this topic, it is suggested: (i) to examine more thoroughly the drivers of the quality of life related to urban ponds, and to highlight their specificity among other elements of the urban blue and green infrastructure, (ii) to carry out an in-depth study of socio-demographic factors explaining the acceptance of urban ponds, considering the level of education and employment status, with the finality to encourage more inclusion, equity and diversity, and (iii) to address the public perception of the “disservices” offered by urban ponds (e.g., unwanted species such as mosquitoes, safety aspects for children).

Data availability

Data are available in the master thesis by Vasco (2023) and also on request.

References

Alikhani S, Nummi P, Ojala A (2021) Urban wetlands: A review on ecological and cultural values. Water 13(22):3301. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13223301

Anderson CC, Renaud FG (2021) A review of public acceptance of nature-based solutions: The ‘why’, ‘when’, and ‘how’of success for disaster risk reduction measures. Ambio 50:1552–1573

Anguelovski I, Connolly JJ, Cole H, Garcia-Lamarca M, Triguero-Mas M, Baró F, Martin N, Conesa D, Shokry G, Del Pulgar CP (2022) Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat Commun 13:3816

Arnberger A, Eder R, Preiner S, Hein T, Nopp-Mayr U (2021) Landscape preferences of visitors to the Danube Floodplains National Park, Vienna. Water 13(16):2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13162178

Asakawa S, Yoshida K, Yabe K (2004) Perceptions of urban stream corridors within the greenway system of Sapporo, Japan. Landsc Urban Plan 68:167–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(03)00158-0

Bastien NRP, Arthur S, McLoughlin MJ (2012) Valuing amenity: Public perceptions of sustainable drainage systems ponds. Water Environ 26:19–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-6593.2011.00259.x

Baxter DE, Pelletier LG (2019) Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Can Psychol 60:21

Beninde J, Veith M, Hochkirch A (2015) Biodiversity in cities needs space: a meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol Lett 18:581–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12427

Boothby J (1997) Pond conservation: towards a delineation of pondscape. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 7:127–132

Botkin DB, Beveridge CE (1997) Cities as environments. Urban Ecosyst 1:3–19

Chapin FS III, Zavaleta ES, Eviner VT, Naylor RL, Vitousek PM, Reynolds HL, Hooper DU, Lavorel S, Sala OE, Hobbie SE, Mack MC, Díaz S (2000) Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 405:234–242. https://doi.org/10.1038/35012241

Cuenca-Cambronero M, Blicharska M, Perrin JA, Davidson TA, Oertli B, Lago M, Beklioglu M, Meerhoff M, Arim M, Teixeira J (2023) Challenges and opportunities in the use of ponds and pondscapes as Nature-based Solutions. Hydrobiologia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-023-05149-y

Dallimer M, Irvine KN, Skinner AM, Davies ZG, Rouquette JR, Maltby LL, Warren PH, Armsworth PR, Gaston KJ (2012) Biodiversity and the feel-good factor: understanding associations between self-reported human well-being and species richness. Bioscience 62:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.9

de la Barrera F, Reyes-Paecke S, Harris J, Bascuñán D, Farías JM (2016) People’s perception influences on the use of green spaces in socio-economically differentiated neighborhoods. Urban For Urban Green 20:254–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.09.007

Díaz S, Fargione J, Chapin FS III, Tilman D (2006) Biodiversity loss threatens human well-being. PLoS Biol 4(8):e277. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040277

Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López B, Watson RT, Molnár Z, Hill R, Chan KM, Baste IA, Brauman KA (2018) Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 359:270–272

Díaz SM, Settele J, Brondízio E, Ngo H, Guèze M, Agard J, Arneth A, Balvanera P, Brauman K, Butchart S (2019) The global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services: Summary for policy makers. Intergovern Scie-Policy Platform Biodivers Ecosyst Serv

Dobbie MF (2013) Public aesthetic preferences to inform sustainable wetland management in Victoria, Australia. Landsc Urban Plan 120:178–189

Dumitru A, Wendling L (2021) Evaluating the impact of nature-based solutions: A handbook for practitioners. Eur Comm EC

Faith DP, Walker PA (2002) The role of trade-offs in biodiversity conservation planning: linking local management, regional planning and global conservation efforts. J Biosci 27(4):393

FSO (2020) Geneva: City statistics portraits 2021. Federal Statistical Office (FSO) - Section Environment, Sustainable Development, Territory. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/cross-sectional-topics/city-statistics/city-portraits/geneva.html. Accessed 14 Dec 2022

Giordano R, Pluchinotta I, Pagano A, Scrieciu A, Nanu F (2020) Enhancing nature-based solutions acceptance through stakeholders’ engagement in co-benefits identification and trade-offs analysis. Sci Total Environ 713:136552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136552

Gledhill DG, James P, Davies DH (2005) Urban pond: a landscape of multiple meanings. University of Salford

Goertzen D, Suhling F (2013) Promoting dragonfly diversity in cities: major determinants and implications for urban pond design. J Insect Conserv 17:399–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-012-9522-z

Hambäck PA, Dawson L, Geranmayeh P, Jarsjö J, Kačergytė I, Peacock M, Collentine D, Destouni G, Futter M, Hugelius G, Hedman S, Jonsson S, Klatt BK, Lindström A, Nilsson JE, Pärt T, Schneider LD, Strand JA, Urrutia-Cordero P, Åhlén D, Åhlén I, Blicharska M (2023) Tradeoffs and synergies in wetland multifunctionality: A scaling issue. Sci Total Environ 862:160746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160746

Hart J (2019) Blue Space: How being near water benefits health. Altern Complement Ther 25:208–210. https://doi.org/10.1089/act.2019.29228.jha

Hassall C (2014) The ecology and biodiversity of urban ponds. Wires Water 1(2):187–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1014

Hassall C, Hill M, Gledhill D (2016) The ecology and management of urban pondscapes. Urban Landsc Ecol. Routledge 147–165

Hayden L, Cadenasso ML, Haver D, Oki LR (2015) Residential landscape aesthetics and water conservation best management practices: Homeowner perceptions and preferences. Landsc Urban Plan 144:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.08.003

Hill MJ, Hassall C, Oertli B, Fahrig L, Robson BJ, Biggs J, Samways MJ, Usio N, Takamura N, Krishnaswamy J, Wood PJ (2018) New policy directions for global pond conservation. Conserv Lett 11:e12447. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12447

Hoyle H, Jorgensen A, Hitchmough JD (2019) What determines how we see nature? Perceptions of naturalness in designed urban green spaces. People Nat 1:167–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.19

Jacobs C, Klok L, Bruse M, Cortesão J, Lenzholzer S, Kluck J (2020) Are urban water bodies really cooling? Urban Clim 32:100607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100607

Jarić I, Bellard C, Courchamp F, Kalinkat G, Meinard Y, Roberts DL, Correia RA (2020) Societal attention toward extinction threats: a comparison between climate change and biological invasions. Sci Rep 10:11085

Jones S (1999) Participation and community at the landscape scale. Landsc J 18(1):65–78. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.18.1.65

Krivtsov V, Forbes H, Birkinshaw S, Olive V, Chamberlain D, Buckman J, Yahr R, Arthur S, Christie D, Monteiro Y, Diekonigin C (2022) Ecosystem services provided by urban ponds and green spaces: a detailed study of a semi-natural site with global importance for research. Blue-Green Syst 4:1–23. https://doi.org/10.2166/bgs.2022.021

Lamond J, Everett G (2019) Sustainable blue-green infrastructure: A social practice approach to understanding community preferences and stewardship. Landsc Urban Plan 191:103639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103639

Lefebvre H (1967) Le droit à la ville. L’homme et la Société 6:29–35

Liu R, Xiao J (2021) Factors Affecting Users’ Satisfaction with urban parks through online comments data: Evidence from Shenzhen, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010253

Manuel PM (2003) Cultural perceptions of small urban wetlands: Cases from the Halifax regional municipality, Nova Scotia, Canada. Wetlands 23:921–940. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2003)023[0921:CPOSUW]2.0.CO;2

Martin JL, Maris V, Simberloff DS (2016) The need to respect nature and its limits challenges society and conservation science. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:6105–6112

Matsuoka RH, Kaplan R (2008) People needs in the urban landscape: Analysis of landscape and urban planning contributions. Landsc Urban Plan 84:7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.09.009

McKinney ML (2006) Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol Cons 127:247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.005

Meilland M (2018) Évaluation sociale des plans d’eau des parcs publics urbains. Rapport de stage de fin de 3ème année, ISARA-Lyon et HEPIA-Genève

Nassauer JI (2004) Monitoring the success of metropolitan wetland restorations: Cultural sustainability and ecological function. Wetlands 24:756. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2004)024[0756:MTSOMW]2.0.CO;2

Ngiam R, Lim W, Matilda Collins C (2017) A balancing act in urban social-ecology: Human appreciation, ponds and dragonflies. Urban Ecosyst 20:743–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0635-0

Nordh H, Alalouch C, Hartig T (2011) Assessing restorative components of small urban parks using conjoint methodology. Urban For Urban Green 10:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2010.12.003

Oertli B, Joye DA, Castella E, Juge R, Lachavanne J-B (2000) Diversité biologique et typologie écologique des étangs et petits lacs de Suisse. LEBA, Université de Genève, Genève, OFEFP

Oertli B, Biggs J, Céréghino R, Grillas P, Joly P, Lachavanne JB (2005) Conservation and monitoring of pond biodiversity: introduction. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 15:535–540. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.752

Oertli B, Céréghino R, Hull A, Miracle R (2010) Pond conservation: From science to practice. Pond conservation in Europe. Dev Hydrobiol 210:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9088-1_14

Oertli B, Ilg C (2014) MARVILLE. Mares et étangs urbains: hot-spots de biodiversité au cœur de la ville ? HEPIA, University Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland

Oertli B (2018) Freshwater biodiversity conservation: The role of artificial ponds in the 21st century. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 28:264–269

Oertli B, Boissezon A, Rosset V, Ilg C (2018) Alien aquatic plants in wetlands of a large European city (Geneva, Switzerland): from diagnosis to risk assessment. Urban Ecosyst 21:245–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-017-0719-5

Oertli B, Parris KM (2019) Review: Toward management of urban ponds for freshwater biodiversity. Ecosphere 10:e02810. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2810

Oertli B, Decrey M, Demierre E, Fahy J, Gallinelli P, Vasco F, Ilg C (2023) Ornamental ponds as Nature-based solutions to implement in cities. Sci Total Environ 888:164300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164300

Parker J, Simpson GD (2018) Visitor Satisfaction with a public green infrastructure and urban nature space in Perth, Western Australia. Land 7(4):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040159

Paul S, Nagendra H (2017) Factors influencing perceptions and use of urban nature: Surveys of park visitors in Delhi. Land 6(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6020027

Pedersen E, Weisner SEB, Johansson M (2019) Wetland areas’ direct contributions to residents’ well-being entitle them to high cultural ecosystem values. Sci Total Environ 646:1315–1326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.236

Persson J (2012) Urban lakes and ponds. Encycl Earth Sci 836–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4410-6_15

Schmeller DS, Courchamp F, Killeen G (2020) Biodiversity loss, emerging pathogens and human health risks. Biodivers Conserv 29:3095–3102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02021-6

Scholte SSK, Todorova M, van Teeffelen AJA, Verburg PH (2016) Public support for wetland restoration: What is the link with ecosystem service values? Wetlands 36:467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-016-0755-6

Schüle SA, Gabriel KMA, Bolte G (2017) Relationship between neighbourhood socioeconomic position and neighbourhood public green space availability: An environmental inequality analysis in a large German city applying generalized linear models. Int J Hyg Environ Health 220:711–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.02.006

Seymour V (2016) The human–nature relationship and its impact on health: A critical review. Front Public Health 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00260

Shaffer HB (2018) Urban biodiversity arks. Nat Sustain 1:725–727. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0193-y

Shrestha S, Devkota K, Dahal N, Neupane KR (2021) Application of recharge ponds for water management: Explaining from nature based solution perspective. Dhulikhel’s Journey Towards Water Security 142

Simaika JP, Samways MJ, Frenzel PP (2016) Artificial ponds increase local dragonfly diversity in a global biodiversity hotspot. Biodivers Conserv 25:1921–1935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1168-9

Soga M, Gaston KJ (2016) Extinction of experience: the loss of human–nature interactions. Front Ecol Environ 14:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1225

Sousa E, Quintino V, Palhas J, Rodrigues AM, Teixeira J (2016) Can environmental education actions change public attitudes? An example using the pond habitat and associated biodiversity. PLoS ONE 11:e0154440

Sterrett SC, Katz RA, Fields WR, Campbell Grant EH (2019) The contribution of road-based citizen science to the conservation of pond-breeding amphibians. J Appl Ecol 56(4):988–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13330

UN DESA (2018) 2018 revision of world urbanization prospects. United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Afairs (DESA)

Vandergert P, Georgiou P, Peachey L, Jelliman S (2021) Urban blue spaces, health, and well-being. Nat-Based Solut Water Secur 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819871-1.00013-0

Vasco F (2023) Public perception of the biodiversity and other nature’s contributions to people offered by urban ponds in Geneva, Switzerland. Master's thesis, University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland (HES-SO/HEPIA)

Wilby RL, Perry GLW (2006) Climate change, biodiversity and the urban environment: a critical review based on London, UK. Prog Phys Geogr 30(1):73–98. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309133306pp470ra

Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhai J, Wu Y, Mao A (2021) Waterscapes for promoting mental health in the general population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(22):11792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211792

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO). Many thanks to Eliane Demierre for sharing her knowledge on Geneva’s ponds. We would also like to thank Julie Fahy, Marine Decrey, Aurélie Boissezon, and Jules Hornung for field information and valuable exchanges, as well as Lucas Villard for his support in statistics. We are grateful to Pascale Nicolet (Freshwater Habitat Trust, UK) for reviewing the language and for providing insightful comment. Additionally, we appreciate the H2020 European Union -funded PONDERFUL project (Grant No. H2020-LC-CLA-2019-2), for the data provided on the two Swiss pondscapes investigated.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FV and BO designed and conceived the study, with contribution of JAP. FV collected field data, conducted statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft. FV, BO, and JAP edited subsequent drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendices

Appendix A. Survey questionnaire

Appendix B. Profile of the interviewees

Appendix C. Statistics

In the treatment of the data, the very low- and low-income categories were assumed as low income and the high and very high-income categories were assumed as high-income. Significance level α = 0.05. Means that do not share a letter are significantly different (Tukey grouping). *For p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vasco, F., Perrin, JA. & Oertli, B. Urban pondscape connecting people with nature and biodiversity in a medium-sized European city (Geneva, Switzerland). Urban Ecosyst (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01493-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01493-y