Abstract

Urbanization can alter the composition of arthropod communities. However, little is known about how urbanization affects ecological interactions. Using experimental colonies of the black bean aphid Aphis fabae Scopoli reared on Vicia faba L, we asked if patterns of predator-prey, host-parasitoid and ant-aphid mutualisms varied along an urbanization gradient across a large town in southern England. We recorded the presence of naturally occurring predators, parasitoid wasps and mutualistic ants together with aphid abundance. We examined how biotic (green areas and plant richness) and abiotic features (impervious surfaces and distance to town center) affected (1) aphid colony size, (2) the likelihood of finding predators, mutualistic ants and aphid mummies (indicating the presence of parasitoids), and (3) how the interplay among these factors affected patterns of parasitoid attack, predator abundance, mutualistic interactions and aphid abundance. Aphid abundance was best explained by the number of mutualistic ants attending the colonies. Aphid predators responded negatively to both the proportion of impervious surfaces and to the number of mutualistic ants farming the colonies, and positively to aphid population size, whereas parasitized aphids were found in colonies with higher numbers of aphids and ants. The number of mutualistic ants attending was positively associated with aphid colony size and negatively with the number of aphid predators. Our findings suggest that for insect-natural enemy interactions, urbanization may affect some groups, while not influencing others, and that local effects (mutualists, host plant presence) will also be key determinants of how urban ecological communities are formed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urbanization is the defining feature of recent history; today over 50% (>90% in developed countries) of people live in urban environments (United Nations 2014). Urbanization is arguably the greatest anthropogenic transformation that ecological systems experience, and while most studies of urban ecology focus on changes to the diversity and abundance of species inhabiting towns and cities, attention has only started to focus on how assemblages of interacting species are formed in urban areas, and how this is affected by the intensity of urbanization (Bennett and Gratton 2012; Quispe and Fenoglio 2015; Pereira-Peixoto et al. 2016; Turrini et al. 2016). Fragmentation reduces populations of native plants (Benitez-Malvido 1998; Jules 1998; Williams et al. 2005), leads to decreased connectivity between vegetation patches and existing patches tend to be smaller (Medley et al. 1995; McKinney 2002) and therefore of reduced quality as habitat for many animal species (Bradley and Altizer 2007; Faeth et al. 2011; Turrini et al. 2016). There are also some dramatic physical changes from increased densities of roads, buildings and other sealed structures and microclimatic changes such as the urban heat island effect (Bradley and Altizer 2007; Faeth et al. 2011). Together, these changes affect the likelihood of encountering species at higher trophic levels (Faeth et al. 2005; Egerer et al. 2017). Understanding how such extreme anthropogenic habitat changes may affect patterns of ecological interactions is perhaps most tractable with arthropod model systems (McIntyre 2000; Bang and Faeth 2011), but experimental studies in urban ecosystems are scarce.

Urbanization has been shown to affect the structure of insect communities, resulting in dramatic changes in their abundance and richness (McIntyre 2000; Grimm et al. 2008; Raupp et al. 2010; Gardiner et al. 2014), most frequently leading to a loss of diversity (Kahn and Cornell 1989; Suarez et al. 1998; McKinney 2002; Shochat et al. 2004; Sadler et al. 2006; Clark et al. 2007; Magura et al. 2010; Uno et al. 2010; Bang and Faeth 2011; Bennett and Gratton 2012; Ramírez Restrepo and Halffter 2013). Few studies have considered how these changes influences the outcome of ecological interactions at multiple trophic levels (Shrewsbury and Raupp 2006; Bennett and Gratton 2012; Fenoglio et al. 2013; Pereira-Peixoto et al. 2016; Turrini et al. 2016). For example, abiotic environmental factors might interfere with biotic interactions, thereby modulating the strength of the trophic effects on food webs (Ritchie 2000; Preisser and Strong 2004; Turrini et al. 2016). Mooney et al. (2016) investigated if variation in light availability (shaded understory or open meadow) determines the abundance of the aphid Aphis helianthi feeding on the herb Ligusticum porteri. Aphid numbers were higher in open meadows than in shaded environments. This pattern was not due to the direct effects of light on aphid performance, plant quality or interactions with natural enemies, but instead was due to an indirect effect mediated by a mutualistic relationship with ants, which were more abundant in meadows. If, as expected, insects and other arthropods do respond to habitat structure, then we can predict that there will be differences not only in species assemblages, but also on trophic dynamics and species interactions as habitat configuration changes with urbanization.

If we consider that urban wildlife is subject to multiple changes in abiotic conditions simultaneously, it is not surprising that predicting the consequences of such changes for trophic processes and for direct and indirect species interactions is highly challenging (Turrini et al. 2016). However, a few trends have begun to appear. Urban areas are often characterized by reduced numbers of native vertebrate predators (McKinney 2002; Shochat 2004), an increased abundance of some urban-adapted species, which can potentially lead to increased competition and displacement (Hostetler and McIntyre 2001), altered behavior and phenology (Connor et al. 2002; Neil and Wu 2006), high densities of herbivorous arthropods (Dreistadt et al. 1990; Hanks and Denno 1993; Tooker and Hanks 2000), lower numbers of arthropod predators (Turrini et al. 2016) and lower numbers of parasitoids (Denys and Schmidt 1998; Bennett and Gratton 2012; Burks and Philpott 2017). All these changes can potentially lead to altered trophic structure, and we must recognize that trophic dynamics cannot be understood based only on our knowledge of species composition (Shochat et al. 2006). This way, evaluating empirically how trophic dynamics behave in urban environments may help us to make some broad and useful predictions regarding the effects that urbanization could have on multi-trophic interactions.

With direct trophic interactions such as predation, one species has a negative effect on the other species, but in indirect interactions one species can also positively affect another species through intermediate levels in a trophic cascade (Halaj and Wise 2001; Müller et al. 2005; Turrini et al. 2016). For example, the presence of some species of honeydew-collecting ants results in increased aphid numbers and also increased numbers of aphid parasitoids when protecting aphids from predators and incidentally also protecting parasitized aphids against predators and hyperparasitoids (Völkl 1992; Kaneko 2002). Nevertheless, the most recognized indirect trophic interactions are top-down trophic cascades in which predators influence plants by feeding on herbivores, thus reducing the consequences of herbivory (Schmitz et al. 2000; Shurin et al. 2002; Turrini et al. 2016).

Traditionally, research on trophic interactions and food webs mainly focus on direct interactions such as predation or parasitism, therefore the importance of non-trophic, indirect, and facilitative interactions has been rarely taken into consideration (Ohgushi 2008). Facilitative or positive interactions, like mutualisms, are rarely considered as potential factors affecting urban populations and communities (but see e.g. Thompson and McLachlan 2007; Gibb and Johansson 2010; Toby Kiers et al. 2010), and it is claimed that this type of positive interaction plays an important part in the structuring of some biological communities by providing refuge from predation or competition (Stachowicz 2001). Conversely, it is important to consider that mutualisms have formed over evolutionary time scales, and we do not know if mutualisms have evolved to be resilient enough to endure anthropogenic disturbances (Sachs and Simms 2006; Toby Kiers et al. 2010).

Host-parasitoid interactions are also likely to be considerably altered in urban ecosystems. Here, plant resources for herbivorous insects and their parasitoids are spatially subdivided and embedded in a matrix of built environment (Bennett and Gratton 2012; Fenoglio et al. 2013). These conditions are particularly prone to altering insect colonization and persistence, which may lead to altered trophic interactions (Fenoglio et al. 2013). Parasitoid insects are important biological control agents of herbivorous insect populations and have been found to be negatively affected by urbanization at both local and landscape spatial scales (Bennett and Gratton 2012; Fenoglio et al. 2013). Parasitoids are specialist organisms closely associated with their hosts (Kruess and Tscharntke 1994). Consequently, they might present higher sensitivity to environmental fluctuation and anthropogenic disturbance in comparison to less specialized species (Gibb and Hochuli 2002). Since some herbivore pest populations are limited by top-down control by parasitoids (Hawkins and Gross 1992), a decrease in parasitism or predation can favour pest outbreaks in these areas (Schmitz et al. 2000; Roslin et al. 2014).

Even less frequently considered is how these different ecological interactions (host-parasitoid, predator-prey, mutualisms) act together to affect the insect assemblages found in urban environments. Systems including different types of interactions and trophic groups have only recently started to be empirically examined (Halaj and Wise 2001; Lurgi et al. 2016). In this work we explore these interconnected biological interactions in an urban environment. We used a study system which consisted of experimental colonies of the herbivorous aphid Aphis fabae Scopoli reared on an herbaceous plant species (the dwarf broad bean Vicia faba L.) and their naturally occurring predators, parasitoid wasps and mutualistic ants along an urbanization gradient in a large town in southern England.

Study sites varied in the amount of impervious surfaces, green areas, plant species richness and position on the urban gradient. Distance from the town center is a variable frequently used as a proxy for urban gradients, as cities and towns frequently show gradients of urbanization from their centers to their edges, and that the biotic and abiotic factors that can potentially affect biological systems tend to follow and change as function of this gradient, resulting from variation in human population density and intensity of activity (Deichsel 2006; Clark et al. 2007; Bang and Faeth 2011). The extent of impervious cover (paved surfaces, structures such as buildings and roads) causes a variety of detrimental effects on arthropods (Morse et al. 2003; Sadler et al. 2006; Magura et al. 2008; Bennett and Gratton 2014), and it is a stronger predictor of urbanization gradients than broad classifications such as urban, suburban and rural areas (Ellis and Ramankutty 2008; Ramalho and Hobbs 2012; Savage et al. 2015). Variation in structure of green spaces within cities represents the availability of habitats for arthopods in gradients of urbanization, however, green spaces within cities that present complex structures and higher plant richness are thought to be of high quality as habitats for insects (Pauleit and Duhme 2000; Whitford et al. 2001; Turner et al. 2005).

Here, we report the results of a study asking a) if the relative performance of aphid colonies (i.e. aphid population numbers) was associated with urbanization; b) if the presence of natural enemies (insect predators, parasitoids) and mutualists (ants) found on colonies was determined by urbanization or aphid numbers; c) how biotic factors (the assemblage of natural enemies and mutualists, green areas, plant species diversity and aphid numbers) and abiotic factors (impervious surfaces, distance from urban centre) act in concert to determine herbivore population sizes and the occurrence of their mutualists and natural enemies.

Methods

Study sites and habitat variables

Study sites were located in Greater Reading, Berkshire (51°27’N, 0°58’W), a large town in southern England with a population of 290,000, which covers an area of ca. 72 km2. Twenty-eight experimental sites were selected, and sites were selected in order to capture an approximate gradient from very urbanized environments in the town center to suburban areas located on the south, covering areas of carparks, churchyards, parks, private and community gardens and woodlands. Each study site was at least 110 m apart (Fig. 1).

Land-use data for urbanization metrics were derived from the Ordnance Survey MasterMap® Topography layer, which represents topography at a scale of 1:1250. This is subdivided into a number of themes: administrative boundaries, buildings, heritage and antiquities, land, rail, roads, tracks and paths, structures, terrain and height and water. Using GIS techniques, 30-m-radius buffers were delimited from the sites where the experimental plants were located. This buffer size was chosen due to restrictions in access, and also due to limitations in sampling effort for the estimation of plant diversity.

Reclassification of urbanization metrics was performed to give the proportions of area represented by the following habitat types within those buffers: green areas, which was composed of gardens and lawns with ornamental plants, bushes, trees and shrubs; impervious surfaces, which comprised of buildings (any building or artificial structure made of concrete, brick or stone) and byways (roads, roadsides, tracks or paths made of impervious surfaces such as asphalt). This procedure was carried using QGIS 2.8.1 (QGIS Development Team 2015). In addition to these habitat variables, plant species richness within a 30-m radius of the study sites was estimated during the experimental period by visually counting all plant morphospecies within the area surrounding each experimental colony. This method is strongly correlated with species richness and it effectively captures variance between study areas, with the advantage of reduced sampling effort and increased effectiveness to achieve statistical power (Abadie et al. 2008; Schmiedel et al. 2016). Distance to the urban center (m) was calculated from each study site to a point at the central area of the town (Fig. 1).

Study system and summer recording

Black bean aphids Aphis fabae Scopoli were maintained in a monoclonal culture in the laboratory using plastic and mesh cages. Cultures were kept at a constant temperature of 20 ± 1 °C and 16:8 h L:D light regime at ambient humidity on broad bean, Vicia faba L. (var. the Sutton dwarf). Three days before being allocated to the study sites, three adults were transferred from the culture and reared on 14–16 day old dwarf broad bean plants (18–22 cm in height) to allow new colonies to become established. These plants were sown in pots with traditional potting compost (Vitax Grower, Leicester, England), and watered as required. After three days, the established aphid colonies on broad bean plants were transferred to the 28 study sites.

Two days after experimental colonies were placed in the field, species and numbers of aphids, predators, ants and parasitized aphids (mummies) were recorded, and then subsequently every three days for five recording days providing a total of 17 days of sampling in the field. At the end of this sampling period the plant/aphid-colonies were removed and replaced by new ones in the field. Sampling was repeated four times in 2015 (sampling period one: May 16, 20, 24, 28 and June 1; period two: June 15, 19, 23, 27 and July 1; period 3: July 16, 20, 24, 28 and August 1; period four: August 14, 18, 22, 26 and 30).

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using R 3.1.2 (R Development Core Team 2014).

The dataset consisted of the cumulative numbers of predators, ants, aphids and aphid mummies of the five counting events on each of the four sampling periods. Some colonies were lost during the four sampling periods (three colonies on the first sampling period, eight colonies on the second sampling period, three colonies on the third sampling period and four colonies on the fourth sampling period), caused by poor plant health, herbivory of plants by snails and slugs, and also from damage or theft by the public. This resulted in 94 observations for analysis.

All counts of aphids, predators, ants, mummies and plant richness were either log-transformed or square root-transformed to deal with extreme values and to standardize and homogenize residuals (Crawley 2007; Zuur et al. 2009). To analyze aphid colony numbers we used a linear mixed model fitted by reduced maximum likelihood using package nlme (Pinheiro et al. 2016), and as fixed factors (explanatory variables) we used proportion of impervious surfaces, plant richness, distance to the town center, predator abundance, number of ants farming the colony, parasitized mummies and an interaction factor between ants and predator numbers. We accounted for repeated sampling of colonies in sites through time by adding period as a random effect. We removed the variable proportion of green areas from the set of explanatory variables since it was highly correlated to the proportion of impervious surfaces (r = −0.92).

To deal with the excess of zeros when modelling ants, predators and parasitized mummies as response variables, we transformed these variables as factors (presence or absence) and ran logistic regressions models with a binomial error distribution family (with canonical link logit) using the function ‘glmer’ of package lme4 (Bates et al. 2015), with period as a random effect and fitted by maximum likelihood (Crawley 2007). When modelling predators we used the proportion of impervious surfaces, plant richness, distance to the town center, aphid abundance, number of ants farming the colony, and number of parasitized mummies as explanatory factors. When modelling ants as response variable, we used the proportion of impervious surfaces, plant richness, distance to the town center, predator abundance, aphid numbers, and numbers of parasitized mummies. When analyzing parasitized mummies as the response variable, we removed the first sampling period from the dataset since no mummies were found on this period (leaving 69 observations in total), then we modelled this as a function of the proportion of impervious surfaces, plant richness, distance to the town center, predator abundance, aphid numbers, and number of ants.

Model selection was made by comparing all candidate models using Akaike’s Information Criteria (Burnham and Anderson 2003) by developing a series of alternative mixed effect models that include different combinations of the explanatory variables (Zuur et al. 2009, Table 1), by fitting the full model with the set of all possible explanatory variables and taking out the least significant term on each step (Crawley 2007). We then ranked the models according to AIC differences (Δi = AICi – AICmin, where AICi is the model i value and AICmin is the best model value). Models with Δi < 2 provide substantial support for a candidate model, whereas values of Δi between 4 and 7 provide less support and Δi > 10 indicates that the model is unlikely. We also calculated Akaike weights for all models, where these model weights are used to indicate the importance of a model, with increasing weights indicating the likelihood of a particular model as the overall best model (Burnham and Anderson 2003). Aikaike weights can also be used to calculate the relative importance of a variable by summing the Akaike weights of all models that include that variable (Burnham and Anderson 2003).

We checked if collinearity could be a potential issue in our models through variance inflation factors (VIF) which is used as an indicator of multicollinearity in multiple regression, with VIF values higher than 3 indicating that covariation between predictors may be a problem (Zuur et al. 2007). All our VIF values were in the range of 1.34–2.94. All response variables were checked for spatial autocorrelation through spline correlograms on package ncf (Bjornstad 2015), and we did not find any significant spatial structure in the response variables. We assessed the validity of all models by checking normality, independence and homogeneity of model residuals.

Results

Study sites

Our study sites captured an urban gradient. The proportion of impervious surfaces was negatively correlated (r = −0.46), and plant diversity positively correlated (r = 0.61), with distance from town center. Plant richness varied from 14 to 100 species (mean ± SE: 35.86 ± 3.42), proportion of impervious surfaces varied from 0 to 0.862 (mean ± SE: 0.425 ± 0.051) and proportion of green areas around study sites varied from 0.138 to 1 (mean ± SE: 0.526 ± 0.050) (Fig. 1).

Taxa recorded

In total we observed 30,557 aphids, 146 predators, 660 ants and 448 mummies on our experimental plants. The ants attending the aphid colonies were Myrmica rubra (L.) and Lasius niger (L.). The predator guild comprised mainly of spiders (Arachnida; 59%) and hoverfly larvae (Diptera: Syrphidae; 21%), aphid midges (Cecidomyiiidae; 7%), flower bugs (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae; 6%), ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae; 3%) and smaller numbers (4%) of earwigs (Dermaptera), harvestmen (Opiliones) and lacewings (Neuroptera).

Aphid abundance

Model selection based on AIC differences revealed three model candidates (Δi < 2) for explaining variance on aphid numbers, the first with predators, ants and parasitoids; the second with predators and ants and the third only with numbers of ants farming aphid colonies (Table 1, models 1, 2, 3). However, Akaike weights indicated that the first and third models are more likely to be the best models for explaining aphid numbers (Table 2), with ants farming the aphid colony the variable of the highest importance, being positively correlated with aphid increase (0.885 based on the sum of Akaike weights within models with Δi < 2) (Fig. 2).

Relationship between abundance of aphids and numbers of ants farming the aphid colonies throughout the four sampling periods. Although linear mixed-effects models were performed (see Methods), the linear model trend line is shown to illustrate the direction of the significant relationship between variables. Note log scale used on y and x axes

Aphid predators

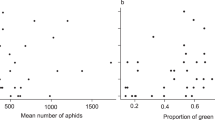

Based on AIC differences two models were selected as candidates for explaining the presence of predators on aphid colonies (Table 1, models 4 and 5); however since model 5 is 1.76 times more likely to be the best model (evidence ratio = 0.467/0.265) we chose this model as the overall best model. As explanatory factors, this model included proportion of impervious surfaces, which negatively determined predator presence; number of aphids, positively determining predator presence; and number of ants farming the colony, which negatively influenced the presence of aphid predators (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Representation of logistic regression model of (a) proportion of impervious surfaces, (b) number of aphids and (c) number of ants farming aphid colonies in predicting the presence (1) or absence (0) of predators in the colonies. Note that a multivariate logistic mixed effects model was used (see Methods), but the trend line for a logistic regression model for just one explanatory variable on each panel was used to illustrate the direction of relationship between variables. Log scale used on x axis of panels (b) and (c)

Ants farming aphid colonies

Three candidate models were selected based on AIC differences for explaining the presence of ants farming aphid colonies (Table 1, models 6, 7, 8). Model 7 (Table 2), with number of aphids, predators and parasitized mummies as explanatory factors, seemingly to be the best model due to its higher Akaike weight (0.434). However, Fig. 3 only shows the logistic regression curves for number of aphids (positive; Fig. 4a) and number of predators (negative; Fig. 4b) as explanatory factors as the number of parasitized mummies was not significant at α = 0.05 (Table 2, model 7).

Panel (a) shows the logistic regression curve for number of aphids as an explanatory variable for the presence (1) or absence (0) of ants farming aphids on the experimental plants. Panel (b) shows the logistic regression curve for number of predators predicting number of ants farming aphid colonies. Note that a multivariate logistic mixed effects model was performed (see Methods); however, the trend line for a logistic regression model for just one explanatory variable on each panel was used to illustrate the direction of relationship between variables. Log scale was used on x axis on panel (a) and square-root scale on panel (b)

Parasitoid attack

Two candidate models were selected for explaining the presence of parasitized aphids on the colonies: first with the numbers of aphids, colony-farming ants and distance to the town center, and second with the first two variables but without distance to the town center (Table 1, models 9 and 10). Since distance to the town centre was not significant in model 9 (Table 2) we considered the model with only the numbers of aphids and colony-farming ants as the best overall model (model 10 in Table 2, Fig. 5). Both variables were positively correlated with the presence of parasitized aphids on the experimental colonies.

Panel (a) shows the logistic regression curve for number of aphids as explanatory variable for presence (1) or absence (0) of mummies on the experimental plants. Panel (b) shows the logistic regression curve for number of ants farming the colonies predicting number of parasitized aphids. Note that a multivariate logistic mixed effects model was used (see Methods); however, the trend line for a logistic regression model for just one explanatory variable on each panel was used to illustrate the direction of relationship between variables. Log scale used on x axis of both panels

Discussion

Our aim was to investigate how urbanization may affect the intensity and outcome of interactions between species at various trophic levels, using the black bean aphid, its natural enemies and ant mutualists as a model system. Overall, we found that the presence of mutualistic ants, predators and parasitoids varied as a function of aphid numbers on the plants. Predators were the only group affected by abiotic factors, with fewer predators found in areas with increased proportions of impervious surfaces. The presence of mutualistic ants was associated with an increase in both aphid and parasitoid numbers, and a decrease in numbers of aphid predators. In no case did local plant diversity or distance to the urban center affect the abundance of any of the interacting species.

We found that Aphis fabae colony size was not affected by abiotic variables, something expected as each colony remained on their study site for a limited amount of time (~20 days for each sampling period), feeding on plants previously sown under identical conditions. This allows us to consider interactions at higher trophic levels without the confounding effects of plant and prey quality. The abundance of predators was significantly affected by aphid colony size, the number of ants farming aphid colonies and the proportion of impervious surfaces in the habitat. Density dependence in predation is a widely recognized factor (Sinclair and Pech 1996; Hixon and Carr 1997; Anderson 2001; Arditi et al. 2001; Holbrook and Schmitt 2002; Hixon and Jones 2005). In our experiment, ants attending aphid colonies greatly reduced predator numbers. Previous studies have reported that honeydew-collecting ants can alter predator abundance (James et al. 1999; Wimp and Whitham 2001; Kaplan and Eubanks 2002). Neither of the above factors was unexpected. However, we also show that increased urbanization, measured as the proportion of impervious surfaces surrounding the field sites, was associated with a reduction in the numbers of predators recorded.

Insect predators are relatively generalist, and their abundance will be associated with the local population size of a range of prey species. Given the reduction in native plant diversity and abundance in urbanized areas (Dreistadt et al. 1990; Burton et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2008; Isaacs et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2009), it would be surprising if predators were not sensitive to urbanization (McKinney 2006; Jones and Leather 2012; Otoshi et al. 2015). Urban management techniques such as treading, bird feeding, mowing and pesticide application negatively impact predacious beetles and hemipterans (Morris and Rispin 1987; Helden and Leather 2004; Orros and Fellowes 2012; Jones and Leather 2012; Orros et al. 2015; Bennett and Lovell 2014; Smith et al. 2015). Human-induced extinctions and local extirpations are often biased towards higher trophic levels (Pauly et al. 1998; Jackson et al. 2001; Duffy 2002; Byrnes et al. 2005), and that losses of even one or two species that belong to higher trophic levels can cause cascading effects on species present on basal trophic levels (Paine 2002; Schmitz 2003) and critically affect ecosystem processes (Tilman et al. 1997; Byrnes et al. 2005; Hooper et al. 2005).

Urbanized environments might affect organisms at higher trophic levels more than their hosts or prey, particularly when they exhibit higher levels of resource specialization (Tscharntke et al. 1998; Bailey et al. 2005; Pereira-Peixoto et al. 2016). In our study system, this may apply to insect predators but does not appear to affect the likelihood of colonies suffering parasitoid attack. However, there was an indication that parasitized mummies were less frequently found on more urbanized sites of the gradient (closer to the town center, Table 2, model 9), but this factor was not statistically significant. There have been studies which found negative correlations between parasitism and urbanization in a landscape context (Gibb and Hochuli 2002; Bennett and Gratton 2012; Calegaro-Marques and Amato 2014), which was not our objective in this work. The presence of physical barriers and structures like buildings and roads in cities may make insect dispersal problematic, and present an obstacle for breeding and foraging (Wratten et al. 2003; Raupp et al. 2010; Peralta et al. 2011). On the other hand, vegetated areas bordering roads, pavements and streets may serve as biological corridors, particularly those that maintain higher plant diversity and density (Haddad et al. 2003; Peralta et al. 2011).

Although we did not directly measure the functional traits of each trophic guild and how this relates to variance in habitat, our results may suggest a certain degree of sensitivity to urbanization possibly associated with differential dispersal abilities and habitat requirements of predators and parasitoids. Predators were composed of several taxa (spiders, hoverfly larvae, aphid midges, flower bugs and ladybirds), presenting a range of dispersal abilities and with a variety of dietary breadths (Rotheray 1989). Aphid parasitoids are known to use a range of visual, acoustic or olfactory cues to locate potential host patches, including long-range olfactory cues originating from the host plant (Fellowes et al. 2005; Vandermoten et al. 2012). This suggests that the differences in dispersal ability and habitat requirements may be responsible for the differences in vulnerability to urbanization between the two groups (predators and parasitoids) presented by our data. This possibility needs to be further tested.

We found that the mutualistic relationship between aphids and ants was responsible for a significant increase in aphid numbers. In our study, ant attendance at aphid colonies was not affected by habitat variables, and ant-attended colonies were present even on the most urbanized sites of the gradient. Mutualistic ants of aphids are known to protect aphid colonies from predator attack, to prevent mold growth when honeydew accumulates and to avoid aphid competition with other herbivores on the same resource (Stadler and Dixon 1998; Kaneko 2003; Yao 2014). The relationship between aphids and tending ants can then confer direct benefits to aphid survival, allowing highest feeding rates and nutrient uptake. At the same time, aphid-derived honeydew constitutes a nutrient-rich food that may be essential for the survival and growth of ant colonies (Kaplan and Eubanks 2002; Tegelaar et al. 2013). Aphid parasitoids are less likely to be affected by the presence of ants on aphid colonies than predators. Although parasitoid wasps can sometimes be repelled by ants, once wasps successfully oviposit in aphids, these parasitized aphids also receive ant protection, which may in turn result in higher parasitoid emergence rates (Völkl 1992, 1997; Kaneko 2002; Yao 2014). Such patterns (a negative effect of ant presence on generalist predators, a positive effect on specialist enemies) was found by Wimp and Whitham (2001), who examined the mechanisms that determined arthropod community structure in a riparian zone dominated by cottonwood. Our urban ecosystem seemed to show similar trends.

Overall, only predators were affected by the features of urbanization measured on our study. This influence of environmental disturbance on multi-trophic interactions in urban habitats could result in important consequences for the assembly of local ecological communities, and also direct and practical implications for biocontrol services that natural enemies could provide in these habitats (Gibb and Hochuli 2002; Eubanks and Finke 2014; Calabuig et al. 2015; Philpott and Bichier 2017). For example, Turrini et al. (2016) investigated the effects of urbanization on trophic interactions and found that predators reduced aphid abundance less in urban than in agricultural ecosystems. This reduction in top-down regulation in urban areas resulted in urban plants having reduced biomass than plants in adjacent agricultural areas. Findings such as these emphasize that urbanization can influence not only interactions at higher trophic levels, but that these changes also affect plant communities through trophic cascades (Schemske et al. 1994; Brudvig et al. 2015). Our results highlight the negative effect of the main characteristic of cities, the increase amount of impervious surfaces, on an important trophic guild. Given that the amount of impervious surfaces is highly negatively correlated with proportion of green areas, our results reinforce the importance of maintaining and increasing the quality of urban green spaces as habitats for the conservation of biological diversity (Botkin and Beveridge 1997; Peralta et al. 2011), and consequently also on trophic dynamics.

One of the major challenges of ecology is to understand and predict the consequences of environmental changes for biodiversity and ecosystem functioning (van der Putten et al. 2004; Hooper et al. 2005). Variation in responses within and between trophic groups may cause restructuring of communities through changes in competitive, bottom-up and top-down control effects (Van der Putten et al. 2004). Any given species is affected by interactions with other species, therefore understanding how changes in species interactions potentially affect food web structure and function in urban habitats may help us to succeed when planning conservation strategies (Faeth et al. 2005; Faeth et al. 2011). To our knowledge, our work presents the first effort to address how interrelated multi-trophic interactions composed by herbivory, predation, parasitism and mutualism behave in urban habitats, with predation the most affected by the increase of urban features in the habitat. Our findings emphasize the need for careful consideration of how patterns of species interactions may be modified in urban settings, which is essential for conservation efforts that will promote ecosystem services and functioning in cities.

References

Abadie JC, Andrade C, Machon N, Porcher E (2008) On the use of parataxonomy in biodiversity monitoring: a case study on wild flora. Biodivers Conserv 17:3485–3500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9354-z

Anderson TW (2001) Predator responses, prey refuges, and density-dependent mortality of a marine fish. Ecology 82:245–257. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0245:PRPRAD]2.0.CO;2

Arditi R, Tyutyunov Y, Morgulis A, Govorukhin V, Senina I (2001) Directed movement of predators and the emergence of density-dependence in predator–prey models. Theor Popul Biol 59:207–221. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.2001.1513

Bailey JK, Wooley SC, Lindroth RL, Whitham TG (2005) Importance of species interactions to community heritability: A genetic basis to trophic-level interactions. Ecol Lett 9:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00844.x

Bang C, Faeth SH (2011) Variation in arthropod communities in response to urbanization: Seven years of arthropod monitoring in a desert city. Landscape Urban Plann 103:383–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.08.013

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singmann H, Dai B G. G (2015) Package lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using 'eigen' and s4. Version 1.1–10, URL https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html

Benitez-Malvido J (1998) Impact of forest fragmentation on seedling abundance in a tropical rain forest. Conserv Biol 12:380–389

Bennett AB, Gratton C (2012) Local and landscape scale variables impact parasitoid assemblages across an urbanization gradient. Landscape Urban Plann 104:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.09.007

Bennett AB, Gratton C (2014) Measuring natural pest suppression at different spatial scales affects the importance of local variables. Environ Entomol 41:1077–1085. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN11328

Bennett AB, Lovell ST (2014) A comparison of arthropod abundance and arthropod mediated predation services in urban green spaces. Insect Conserv Diver 7:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12062

Bjornstad ON (2015) Package 'ncf': Spatial nonparametric covariance functions. Version 1.1–6, URL https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ncf/index.html

Botkin DB, Beveridge CE (1997) Cities as environments. Urban Ecosyst 1:3–19

Bradley CA, Altizer S (2007) Urbanization and the ecology of wildlife diseases. Trends Ecol Evol 22:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.001

Brudvig LA, Damschen EI, Haddad NM, Levey DJ, Tewksbury JJ (2015) The influence of habitat fragmentation on multiple plant–animal interactions and plant reproduction. Ecology 96:2669–2678. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-2275.1

Burks JM, Philpott SM (2017) Local and landscape drivers of parasitoid abundance, richness, and composition in urban gardens. Environ Entomol 46:201–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvw175

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2003) Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach, 2nd edn. Springer Science & Business Media, Fort Collins

Burton ML, Samuelson LJ, Pan S (2005) Riparian woody plant diversity and forest structure along an urban-rural gradient. Urban Ecosyst 8:93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-005-1421-6

Byrnes J, Stachowicz JJ, Hultgren KM, Hughes AR, Olyarnik SV, Thornber CS (2005) Predator diversity strengthens trophic cascades in kelp forests by modifying herbivore behaviour. Ecol Lett 9:61–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00842.x

Calabuig A, Tena A, Wackers FL, Fernández-Arrojo L, Plou FJ, Garcia-Marí F, Pekas A (2015) Ants impact the energy reserves of natural enemies through the shared honeydew exploitation. Ecol Entomol 40:687–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12237

Calegaro-Marques C, Amato SB (2014) Urbanization breaks up host-parasite interactions: A case study on parasite community ecology of rufous-bellied thrushes (Turdus rufiventris) along a rural-urban gradient. PLoS One 9:e103144. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103144

Clark PJ, Reed JM, Chew FS (2007) Effects of urbanization on butterfly species richness, guild structure, and rarity. Urban Ecosyst 10:321–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-007-0029-4

Connor EF, Hafernik J, Levy J, Moore VL, Rickman JK (2002) Insect conservation in an urban biodiversity hotspot: The San Francisco bay area. J Insect Conserv 6:247–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024426727504

Crawley MJ (2007) The R book, 1st edn. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester

Deichsel R (2006) Species change in an urban setting—ground and rove beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae and Staphylinidae) in Berlin. Urban Ecosyst 9:161–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-006-8588-3

Denys C, Schmidt H (1998) Insect communities on experimental mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris L.) plots along an urban gradient. Oecologia 113:269–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050378

Dreistadt SH, Dahlsten DL, Frankie GW (1990) Urban forests and insect ecology. Bioscience 40:192–198. https://doi.org/10.2307/1311364

Duffy JE (2002) Biodiversity and ecosystem function: The consumer connection. Oikos 99:201–219. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2002.990201.x

Egerer MH, Bichier P, Philpott SM (2017) Landscape and local habitat correlates of lady beetle abundance and species richness in urban agriculture. Ann Entomol Soc Am 110:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/saw063

Ellis EC, Ramankutty N (2008) Putting people in the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world. Front Ecol Environ 6:439–447. https://doi.org/10.1890/070062

Eubanks MD, Finke DL (2014) Interaction webs in agroecosystems: Beyond who eats whom. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2014.06.005

Faeth SH, Bang C, Saari S (2011) Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05925.x

Faeth SH, Warren PS, Shochat E, Marussich WA (2005) Trophic dynamics in urban communities. Bioscience 55:399–407. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0399:TDIUC]2.0.CO;2

Fellowes MDE, van Alphen JJ, Jervis MA (2005) Foraging behaviour. In: Jervis MA (ed) Insects as natural enemies: a practical perspective. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 1–71

Fenoglio MS, Videla M, Salvo A, Valladares G (2013) Beneficial insects in urban environments: Parasitism rates increase in large and less isolated plant patches via enhanced parasitoid species richness. Biol Conserv 164:82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.05.002

Gardiner MM, Prajzner SP, Burkman CE, Albro S, Grewal PS (2014) Vacant land conversion to community gardens: influences on generalist arthropod predators and biocontrol services in urban greenspaces. Urban Ecosyst 17:101–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-013-0303-6

Gibb H, Hochuli DF (2002) Habitat fragmentation in an urban environment: Large and small fragments support different arthropod assemblages. Biol Conserv 106:91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00232-4

Gibb H, Johansson T (2010) Forest succession and harvesting of hemipteran honeydew by boreal ants. Ann Zool Fenn 47:99–110. https://doi.org/10.5735/086.047.0203

Grimm NB, Faeth SH, Golubiewski NE, Redman CL, Wu J, Bai X, Briggs JM (2008) Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 319:756–760. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150195

Haddad NM, Bowne DR, Cunningham A, Danielson BJ, Levey DJ, Sargent S, Spira T (2003) Corridor use by diverse taxa. Ecology 84:609–615. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0609:CUBDT]2.0.CO;2

Halaj J, Wise DH (2001) Terrestrial trophic cascades: How much do they trickle? Am Nat 157:262–281. https://doi.org/10.1086/319190

Hanks LM, Denno RF (1993) Natural enemies and plant water relations influence the distribution of an armored scale insect. Ecology 74:1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.2307/1940478

Hawkins BA, Gross P (1992) Species richness and population limitation in insect parasitoid-host systems. Am Nat 139:417–423

Helden AJ, Leather SR (2004) Biodiversity on urban roundabouts—hemiptera, management and the species–area relationship. Basic Appl Ecol 5:367–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2004.06.004

Hixon MA, Carr MH (1997) Synergistic predation, density dependence, and population regulation in marine fish. Science 277:946–949

Hixon MA, Jones GP (2005) Competition, predation, and density-dependent mortality in demersal marine fishes. Ecology 86:2847–2859. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1455

Holbrook SJ, Schmitt RJ (2002) Competition for shelter space causes density-dependent predation mortality in damselfishes. Ecology 83:2855–2868. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[2855:CFSSCD]2.0.CO;2

Hooper DU, Chapin FS, Ewel JJ, Hector A, Inchausti P, Lavorel S, Lawton JH, Lodge DM, Loreau M, Naeem S, Schmid B, Setälä H, Symstad AJ, Vandermeer J, Wardle DA (2005) Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: A consensus of current knowledge. Ecol Monogr 75:3–35. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-0922

Hostetler NE, McIntyre ME (2001) Effects of urban land use on pollinator (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) communities in a desert metropolis. Basic Appl Ecol 2:209–218. https://doi.org/10.1078/1439-1791-00051

Isaacs R, Tuell J, Fiedler A, Gardiner M, Landis D (2009) Maximizing arthropod-mediated ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes: The role of native plants. Front Ecol Environ 7:196–203. https://doi.org/10.1890/080035

Jackson JB, Kirby MX, Berger WH, Bjorndal KA, Botsford LW, Bourque BJ, Bradbury RH, Cooke R, Erlandson J, Estes JA (2001) Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 293:629–637. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059199

James DG, Stevens MM, O'Malley KJ, Faulder RJ (1999) Ant foraging reduces the abundance of beneficial and incidental arthropods in citrus canopies. Biol Control 14:121–126

Jones EL, Leather SR (2012) Invertebrates in urban areas: A review. Eur J Entomol 109:463–478

Jules ES (1998) Habitat fragmentation and demographic change for a common plant: Trillium in old-growth forest. Ecology 79:1645–1656. https://doi.org/10.2307/176784

Kahn DM, Cornell HV (1989) Leafminers, early leaf abscission, and parasitoids: A tritrophic interaction. Ecology 70:1219–1226. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938179

Kaneko S (2002) Aphid-attending ants increase the number of emerging adults of the aphid's primary parasitoid and hyperparasitoids by repelling intraguild predators. Entomol Sci 5:131–146

Kaneko S (2003) Different impacts of two species of aphid-attending ants with different aggressiveness on the number of emerging adults of the aphid's primary parasitoid and hyperparasitoids. Ecol Res 18:199–212. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1703.2003.00547.x

Kaplan I, Eubanks MD (2002) Disruption of cotton aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) — Natural enemy dynamics by red imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Environ Entomol 31:1175–1183. https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-31.6.1175

Kruess A, Tscharntke T (1994) Habitat fragmentation, species loss, and biological control. Science 264:1581–1584

Lurgi M, Montoya D, Montoya JM (2016) The effects of space and diversity of interaction types on the stability of complex ecological networks. Theor Ecol 9:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-015-0264-x

Magura T, Lövei GL, Tóthmérész B (2010) Does urbanization decrease diversity in ground beetle (Carabidae) assemblages? Glob Ecol Biogeogr 19:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00499.x

Magura T, Tóthmérész B, Molnár T (2008) A species-level comparison of occurrence patterns in carabids along an urbanisation gradient. Landscape Urban Plann 86:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.01.005

McIntyre NE (2000) Ecology of urban arthropods: A review and a call to action. Ann Entomol Soc Am 93:825–835. https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2000)093[0825:EOUAAR]2.0.CO;2

McKinney ML (2002) Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation: The impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. Bioscience 52:883–890. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0883:ubac]2.0.co;2

McKinney ML (2006) Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol Conserv 127:247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.005

Medley KE, McDonnell MJ, Pickett ST (1995) Forest-landscape structure along an urban-to-rural gradient. Prof Geogr 47:159–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1995.00159.x

Mooney EH, Phillips JS, Tillberg CV, Sandrow S, Nelson AS, Mooney KA (2016) Abiotic mediation of a mutualism drives herbivore abundance. Ecol Lett 19:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12540

Morris M, Rispin W (1987) Abundance and diversity of the Coleopterous fauna of a calcareous grassland under different cutting regimes. J Appl Ecol:451–465. https://doi.org/10.2307/2403886

Morse CC, Huryn AD, Cronan C (2003) Impervious surface area as a predictor of the effects of urbanization on stream insect communities in Maine, USA. Environ Monit Assess 89:95–127

Müller CB, Fellowes MDE, Godfray HCJ (2005) Relative importance of fertilizer addition and exclusion of predators for aphid growth in the field. Oecologia 139:419–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1795-9

Neil K, Wu J (2006) Effects of urbanization on plant flowering phenology: A review. Urban Ecosyst 9:243–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-006-9354-2

Ohgushi T (2008) Herbivore-induced indirect interaction webs on terrestrial plants: The importance of non-trophic, indirect, and facilitative interactions. Entomol Exp Appl 128:217–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00705.x

Orros ME, Fellowes MDE (2012) Supplementary feeding of wild birds indirectly affects the local abundance of arthropod prey. Basic Appl Ecol 13:286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2012.03.001

Orros ME, Thomas RL, Holloway GJ, Fellowes MDE (2015) Supplementary feeding of wild birds indirectly affects ground beetle populations in suburban gardens. Urban Ecosyst 18:465–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-014-0404-x

Otoshi MD, Bichier P, Philpott SM (2015) Local and landscape correlates of spider activity density and species richness in urban gardens. Environ Entomol 44:1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv098

Paine RT (2002) Trophic control of production in a rocky intertidal community. Science 296:736–739. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1069811

Pauleit S, Duhme F (2000) Assessing the environmental performance of land cover types for urban planning. Landscape Urban Plann 52:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00109-2

Pauly D, Christensen V, Dalsgaard J, Froese R, Torres F (1998) Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279:860–863. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5352.860

Peralta G, Fenoglio MS, Salvo A (2011) Physical barriers and corridors in urban habitats affect colonisation and parasitism rates of a specialist leaf miner. Ecol Entomol 36:673–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2011.01316.x

Pereira-Peixoto MH, Pufal G, Staab M, Feitosa Martins C, Klein A (2016) Diversity and specificity of host-natural enemy interactions in an urban-rural interface. Ecol Entomol 41:241–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12291

Philpott SM, Bichier P (2017) Local and landscape drivers of predation services in urban gardens. Ecol Appl 27:966–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1500

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D (2016) Package nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. Version 3.1–127, URL https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/index.html

Preisser EL, Strong DR (2004) Climate affects predator control of an herbivore outbreak. Am Nat 163:754–762. https://doi.org/10.1086/383620

QGIS Development Team (2015) QGIS geographic information system. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project, URL http://qgis.osgeo.org

Quispe I, Fenoglio MS (2015) Host–parasitoid interactions on urban roofs: An experimental evaluation to determine plant patch colonisation and resource exploitation. Insect Conserv Diver 8:474–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12127

R Development Core Team (2014) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3–900051–07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org

Ramalho CE, Hobbs RJ (2012) Time for a change: dynamic urban ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 27:179–188

Ramírez Restrepo L, Halffter G (2013) Butterfly diversity in a regional urbanization mosaic in two mexican cities. Landscape Urban Plann 115:39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.03.005

Raupp MJ, Shrewsbury PM, Herms DA (2010) Ecology of herbivorous arthropods in urban landscapes. Annu Rev Entomol 55:19–38. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085351

Ritchie ME (2000) Nitrogen limitation and trophic vs abiotic influences on insect herbivores in a temperate grassland. Ecology 81:1601–1612. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[1601:NLATVA]2.0.CO;2

Roslin T, Várkonyi G, Koponen M, Vikberg V, Nieminen M (2014) Species–area relationships across four trophic levels – decreasing island size truncates food chains. Ecography 37:443–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00218.x

Rotheray GE (1989) Aphid predators. Richmond Publishing Co. Ltd., Kingston upon Thames

Sachs JL, Simms EL (2006) Pathways to mutualism breakdown. Trends Ecol Evol 21:585–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.06.018

Sadler J, Small E, Fiszpan H, Telfer M, Niemelä J (2006) Investigating environmental variation and landscape characteristics of an urban–rural gradient using woodland carabid assemblages. J Biogeogr 33:1126–1138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01476.x

Savage AM, Hackett B, Guénard B, Youngsteadt EK, Dunn RR (2015) Fine-scale heterogeneity across manhattan's urban habitat mosaic is associated with variation in ant composition and richness. Insect Conserv Diver 8:216–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12098

Schemske DW, Husband BC, Ruckelshaus MH, Goodwillie C, Parker IM, Bishop JG (1994) Evaluating approaches to the conservation of rare and endangered plants. Ecology 75:585–606. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941718

Schmiedel U, Araya Y, Bortolotto MI, Boeckenhoff L, Hallwachs W, Janzen D, Kolipaka SS, Novotny V, Palm M, Parfondry M, Smanis A, Toko P (2016) Contributions of paraecologists and parataxonomists to research, conservation, and social development. Conserv Biol 30:506–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12661

Schmitz OJ (2003) Top predator control of plant biodiversity and productivity in an old-field ecosystem. Ecol Lett 6:156–163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00412.x

Schmitz OJ, Hambäck PA, Beckerman AP (2000) Trophic cascades in terrestrial systems: A review of the effects of carnivore removals on plants. Am Nat 155:141–153. https://doi.org/10.1086/303311

Shochat E (2004) Credit or debit? Resource input changes population dynamics of city-slicker birds. Oikos 106:622–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13159.x

Shochat E, Stefanov WL, Whitehouse MEA, Faeth SH (2004) Urbanization and spider diversity: Influences of human modification of habitat structure and productivity. Ecol Appl 14:268–280. https://doi.org/10.1890/02-5341

Shochat E, Warren PS, Faeth SH, McIntyre NE, Hope D (2006) From patterns to emerging processes in mechanistic urban ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 21:186–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.11.019

Shrewsbury PM, Raupp MJ (2006) Do top-down or bottom-up forces determine stephanitis pyrioides abundance in urban landscapes? Ecol Appl 16:262–272. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1347

Shurin JB, Borer ET, Seabloom EW, Anderson K, Blanchette CA, Broitman B, Cooper SD, Halpern BS (2002) A cross-ecosystem comparison of the strength of trophic cascades. Ecol Lett 5:785–791. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00381.x

Smith LS, Broyles MEJ, Larzleer HK, Fellowes MDE (2015) Adding ecological value to the urban lawnscape: insect abundance and diversity in grass-free lawns. Biodivers Conserv 24:47–62 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-014-0788-1

Sinclair ARE, Pech RP (1996) Density dependence, stochasticity, compensation and predator regulation. Oikos:164–173. https://doi.org/10.2307/3546240

Stachowicz JJ (2001) Mutualism, facilitation, and the structure of ecological communities. Bioscience 51:235–246. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568

Stadler B, Dixon A (1998) Costs of ant attendance for aphids. J Anim Ecol:454–459

Suarez AV, Bolger DT, Case TJ (1998) Effects of fragmentation and invasion on native ant communities in coastal southern california. Ecology 79:2041–2056. https://doi.org/10.2307/176708

Tegelaar K, Glinwood R, Pettersson J, Leimar O (2013) Transgenerational effects and the cost of ant tending in aphids. Oecologia 173:779–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-013-2659-y

Thompson B, McLachlan S (2007) The effects of urbanization on ant communities and myrmecochory in Manitoba, Canada. Urban Ecosyst 10:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-006-0013-4

Tilman D, Knops J, Wedin D, Reich P, Ritchie M, Siemann E (1997) The influence of functional diversity and composition on ecosystem processes. Science 277:1300–1302. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5330.1300

Toby Kiers E, Palmer TM, Ives AR, Bruno JF, Bronstein JL (2010) Mutualisms in a changing world: An evolutionary perspective. Ecol Lett 13:1459–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01538.x

Tooker JF, Hanks LM (2000) Influence of plant community structure on natural enemies of pine needle scale (Homoptera: Diaspididae) in urban landscapes. Environ Entomol 29:1305–1311. https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-29.6.1305

Tscharntke T, Gathmann A, Steffan-Dewenter I (1998) Bioindication using trap-nesting bees and wasps and their natural enemies: Community structure and interactions. J Appl Ecol 35:708–719. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.1998.355343.x

Turner K, Lefler L, Freedman B (2005) Plant communities of selected urbanized areas of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Landscape Urban Plann 71:191–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2004.03.003

Turrini T, Sanders D, Knop E (2016) Effects of urbanization on direct and indirect interactions in a tri-trophic system. Ecol Appl 26:664–675. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-1787

United Nations (2014) World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision, highlights. United Nations. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-highlights.pdf. Acessed 11 Nov 2015

Uno S, Cotton J, Philpott SM (2010) Diversity, abundance, and species composition of ants in urban green spaces. Urban Ecosyst 13:425–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-010-0136-5

Van der Putten WH, de Ruiter PC, Martijn Bezemer T, Harvey JA, Wassen M, Wolters V (2004) Trophic interactions in a changing world. Basic Appl Ecol 5:487–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2004.09.003

Vandermoten S, Mescher MC, Francis F, Haubruge E, Verheggen FJ (2012) Aphid alarm pheromone: an overview of current knowledge on biosynthesis and functions. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 42:155–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.11.008

Völkl W (1992) Aphids or their parasitoids: who actually benefits from ant-attendance? J Anim Ecol 61:273–281. https://doi.org/10.2307/5320

Völkl W (1997) Interactions between ants and aphid parasitoids: patterns and consequences for resource utilization. In: Dettner K, Bauer G, Völkl W (eds) Vertical food web interactions: Evolutionary patterns and driving forces. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, pp 225–240

Walker JS, Grimm NB, Briggs JM, Gries C, Dugan L (2009) Effects of urbanization on plant species diversity in central Arizona. Front Ecol Environ 7:465–4e70. https://doi.org/10.1890/080084

Whitford V, Ennos AR, Handley JF (2001) “City form and natural process”—indicators for the ecological performance of urban areas and their application to Merseyside, UK. Landscape Urban Plann 57:91–103

Williams NS, Morgan JW, Mcdonnell MJ, Mccarthy MA (2005) Plant traits and local extinctions in natural grasslands along an urban–rural gradient. J Ecol 93:1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01039.x

Williams NS, Schwartz MW, Vesk PA, McCarthy MA, Hahs AK, Clemants SE, Corlett RT, Duncan RP, Norton BA, Thompson K, McDonnell MJ (2008) A conceptual framework for predicting the effects of urban environments on floras. J Ecol 97:4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01460.x

Wimp GM, Whitham TG (2001) Biodiversity consequences of predation and host plant hybridization on an aphid-ant mutualism. Ecology 82:440–452. https://doi.org/10.2307/2679871

Wratten SD, Bowie MH, Hickman JM, Evans AM, Sedcole JR, Tylianakis JM (2003) Field boundaries as barriers to movement of hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) in cultivated land. Oecologia 134:605–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-002-1128-9

Yao I (2014) Costs and constraints in aphid-ant mutualism. Ecol Res 29:383–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-014-1151-4

Zuur A, Ieno EN, Smith GM (2007) Analysing ecological data. Springer, USA

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM (2009) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer, Netherlands

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Science without Borders and the Coordenaçāo de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES-Brazil) who provided funding for this work and a scholarship for the first author, BEX: 13531-13-1.We also would like to thank garden owners and Reading Borough Council for allowing us to use their properties for our research, and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments. Data are available on request from EAA (eliserocha1@gmail.com).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rocha, E.A., Fellowes, M.D.E. Does urbanization explain differences in interactions between an insect herbivore and its natural enemies and mutualists?. Urban Ecosyst 21, 405–417 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-017-0727-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-017-0727-5