Abstract

Distributional justice—measured by the proportionality between effort exerted and rewards obtained—and guilt aversion—triggered by not fulfilling others’ expectations—are widely acknowledged fundamental sources of pro-social behavior. We design three experiments to study the relevance of these sources of behavior when considered in interaction. In particular, we investigate whether subjects fulfill others’ expectations also when this could produce inequitable allocations that conflict with distributional justice considerations. Our results confirm that both justice considerations and guilt aversion are important drivers of pro-social behavior, with the former having an overall stronger impact than the latter. Expectations of others are less relevant in environments more likely to nurture equitable outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A large body of literature has demonstrated that individuals are not only motivated by self-interest but also care about the consequences of their actions for others (e.g. Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Charness and Rabin 2002). More recently, experiments have highlighted that also what others expect from us can influence the choices we make. Individuals tend to adjust their behavior not to let down others and avoid feeling guilty (see, among others, Baumeister et al. 1995; Charness and Dufwenberg 2006). However, according to social psychology literature, the emotion of guilt has a context-specific component, with some contexts being more conducive to guilt than others (Tangney 1992). Understanding under which circumstances the emotion of guilt plays an economically relevant role is an under-investigated issue.

Here, we conjecture that others’ expectations can be perceived as more or less legitimate, depending on the context faced by the decision-maker, and test whether decision-makers fulfill others’ expectations even when they clash with justice principles (see Bicchieri 2006, for a similar conjecture). We focus on a fundamental justice principle that motivates individuals to seek an equitable (proportional) allocation in terms of effort exerted to create an output and reward obtained for this effort (Konow 2000). This general distributional principle captures the essence of Locke’s law of nature, i.e. that property rights on goods originate in the effort exerted to generate them (Hoffman and Spitzer 1985). Our study investigates whether others’ expectations are more likely to be fulfilled when they are not in conflict with this acknowledged justice principle.

The interaction between guilt feelings and justice considerations might shape behavior in relevant economic interactions. Think, for example, of an employer who must choose between promoting an overconfident employee or an underconfident one. If the employees have similar performances, a guilt averse employer should give the promotion to the overconfident employee to minimize guilt for letting down one of the two employees. Similarly, if the best performing employee has (correctly) higher expectations of getting the promotion, this can further motivate a guilt averse employer to give the promotion to her. However, if the underconfident employee is the best performing one, the employer could give her the promotion, neglecting the employees’ expectations. Another example may come from charity giving. Think of donations to individuals who are facing the consequences of a natural disaster. Likely, a guilt averse individual will donate to meet the expectations of those in need. Yet, the emotional rush to give may be held back by considerations about potential corruption in the allocation process: if donations are likely to end in the wrong hands, even a guilt averse individual may refrain from giving.

We investigate the interplay between guilt and justice considerations in two distinct laboratory experiments. Study 1 builds on a modified dictator game where there is a probability with which a “lost wallet” is restored in the hands of the entitled owner, conditional upon the dictator choosing to return it. A returned wallet can also be misplaced by Nature to an unentitled recipient—who did not exert any effort to earn it—leading to an inequitable allocation. Only the dictator knows this specific, exogenous, restoring probability. Therefore, the entitled recipient cannot condition her expectation (and hence her disappointment for a missed return) upon the restoring probability. We communicate the entitled recipient’s expectation to the dictator to causally identify the effect of expectations. Moreover, we control for potential confounds linked to dictators’ self-serving biases by running a robustness check experiment that replicates the essential features of Study 1 but replaces the dictator with an external spectator with no material stake in the game (e.g., Almås et al. 2020). In Study 2, an external spectator must allocate a reward to one of two individuals that may differ in their expectations of being rewarded and in their desert, as captured by their relative productivity. Study 2 allows for a cleaner empirical identification than Study 1 and allows us to check the robustness of our conjecture across different setups.

In all our studies, simple guilt aversion predicts that decision-makers should try to fulfill expectations regardless of justice considerations (Battigalli and Dufwenberg 2007). According to our hypothesis, instead, they should be more likely to fulfill expectations when doing so also ensures a proportionality between effort exerted and rewards obtained. When fulfilling others’ expectations leads to a violation of justice principles, we expect optimistic expectations to become less relevant. In Study 1, returning the wallet to meet the optimistic expectations of the recipient may entail the risk of violating entitled ownership. In Study 2, meeting optimistic expectations may penalize the best performing worker. Thus, in both studies, expectations seem legitimate when they do not conflict with justice considerations based on effort-related entitlement.

While the literature on guilt aversion is rapidly growing, we are aware of only a few recent experiments that touch upon the issue of expectations’ legitimacy (Balafoutas and Fornwagner 2017; Pelligra et al. 2020). These studies focus on the nature of the requests made by recipients/trustees to dictators/trustors. When requests are too ambitious, they may not trigger guilt feelings because they are perceived as not legitimate. Another related study is the experiment by Danilov et al. (2018), who study the impact of descriptive norms and guilt feelings on giving in the dictator game. We share with these studies the attempt to refine the definition of guilt. However, our work differs from previous studies in the approach to expectations’ legitimacy. We adopt a widely acknowledged justice principle according to which outputs of the production should be allocated in proportion to individual inputs (Konow 2000), and define beliefs’ legitimacy in terms of accordance with this principle.

Our data show that both guilt aversion and justice considerations are key in driving allocation choices. Study 2 provides us with a direct assessment of the importance of the two sources and clearly shows that guilt is of secondary importance relative to justice. Furthermore, in contrast to our initial hypothesis, we do not identify any positive interaction between the two motivational sources. In fact, our studies show the opposite. Dictators in Study 1 and external spectators in Study 2 tend to neglect counterparts’ expectations when the distributional norm is clear, namely when the restoring probability is high in Study 1 and when a worker is better than the other. However, guilt aversion is still relevant in cases in which the distributional norm is less clear. These results are overall confirmed also by the robustness check of Study 1. In the concluding section, we discuss these findings and call for further research on the interaction between distributional norms and expectations.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we position our contribution in both the literature on guilt aversion and on distributional justice. Sections 3 and 4 report design, hypotheses, and results for Study 1 and Study 2, respectively. General conclusions are discussed in Sect. 5.

2 Literature review

Our paper contributes to the literature on the emotion of guilt in strategic interactions. Long-standing literature in social psychology has highlighted the role of guilt in shaping decision-making. Baumeister et al. (1994) stress how guilt can originate from actions causing harm to someone else. Individuals feeling guilty are more likely to engage in forms of pro-social behavior to compensate for the harmed party (Ketelaar et al. 2003; Nelissen et al. 2007). This literature has also documented that guilt can be experienced more in some contexts than in others (e.g. Tangney 1992). More recently, Charness and Dufwenberg (2006) and Battigalli and Dufwenberg (2007) developed a theory of guilt aversion—on which the present paper is focused—that models the decision-maker as averse to let down her counterpart. Specifically, a guilt averse decision-maker forms second-order beliefs on the first-order beliefs that the counterpart holds about the decision-maker’s behavior. Guilt is triggered by the counterpart′s disappointment, which is equal to the difference between the outcome she expected and the realized one. Several laboratory and field experiments provide support for this theory (e.g. Charness and Dufwenberg 2006; Bacharach et al. 2007; Dufwenberg et al. 2011; Bellemare et al. 2011; Babcock et al. 2015).

Some experiments cast doubts on the relevance of guilt aversion. Ellingsen et al. (2010) and Vanberg (2008) note that the positive correlation between the decision-maker’s choice and her second-order beliefs could be the result of a false consensus effect (Engelmann and Strobel 2000). To test for this hypothesis, Ellingsen et al. (2010) elicit the first-order beliefs of some subjects before the play and communicate them to the decision-makers. The authors do not detect any significant effect of more optimistic expectations on decision-makers’ choices in trust and dictator games. In a similar design, however, Reuben et al. (2009) find evidence of guilt aversion.

Theoretical models of guilt aversion à la Battigalli and Dufwenberg (2007) do not explicitly address the issue of beliefs’ legitimacy. One could conjecture that decision-makers only consider others’ expectations that they perceive as legitimate. Indirect support for this conjecture is given by Andreoni and Rao (2011). In their Ask treatment, a recipient can formulate a monetary request to the matched dictator. The authors report an interesting finding, labeled as “the paradox of obviousness”: when individuals ask for what is obvious, they obtain what they ask; when they ask for more than a fair share, they obtain nothing. More broadly, Bicchieri (2006) argues that individuals are more likely to follow a norm when others expect them to follow it, conditional upon others’ expectations being legitimate.

Our study also contributes to the literature on justice principles. In his extensive literature review, Konow (2003) highlights the importance of justice theories that relate fair allocations to individual actions. Equity theory (e.g., Adams 1963) provides clear guidance to assess the fairness of allocations in which a production stage is involved: an equitable allocation should preserve the proportionality of resources invested and rewards obtained across individuals. Thus, those investing more resources in the production of the output should obtain a larger share of it. Experiments in both social psychology and economics report empirical support for this justice principle (e.g., Leventhal and Michaels 1969; Mikula 1974; Konow 2000).

More recently, Cappelen et al. (2007) have identified three fairness ideals that dominate the debate about distributive justice: strict egalitarianism, libertarianism, and liberal egalitarianism. Strict egalitarianism defines justice in terms of equality of allocations, irrespective of the process leading to the production of wealth. Libertarianism and liberal egalitarianism define justice in terms of proportionality between inputs and outputs. The main difference is that libertarianism considers all inputs of the production process, while liberal egalitarianism only considers inputs that are under one’s own control (see also the accountability principle by Konow 1996). In our experiments, the libertarian and liberal egalitarian ideals overlap, as all production factors are controlled by the individual. Cappelen et al. (2007) classify most participants as either libertarian or liberal egalitarian, showing that the production phase has important implications for the allocation decision. The recent work by Almås et al. (2020) indicates that the large majority of participants in an allocation experiment take into account merit when choosing allocations and do not follow a pure egalitarian ideal.

3 Study 1

3.1 Experimental design

The modified dictator game: In a pre-stage game, two players work on a real-effort task to earn an endowment (wallet, henceforth). One of the two players is then selected at random to lose her wallet. The lost wallet is found by the other player. We refer to the player who lost her wallet as Entitled Recipient (ER) and to the one who found it as Dictator (D). The game also includes Nature and a third passive player who did not exert any effort and so has no initial endowment. We call the passive player Unentitled Recipient (UR).

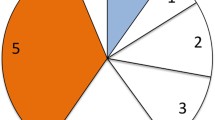

In our game (Fig. 1), D must choose between keeping ER’s wallet or returning it.Footnote 1 If D keeps the wallet, the game ends with D owning her and ER’s wallets, while ER and UR get nothing. If D returns the wallet, the final outcome depends on Nature’s move: with probability \(\lambda\), ER restores her wallet, and with probability \(1-\lambda\), the wallet is misplaced to UR. More precisely, if D chooses Keep, she gets 12, and both ER and UR get 0. If D chooses Return, she gets 9, and either ER or UR gets 7, while the other gets 0, depending on Nature’s move. We sacrificed some realism in the payoff structure for two reasons.Footnote 2 First, payoffs ensure a sizable disappointment for ER if she does not restore her wallet and had optimistic expectations about it. This way, the possible psychological cost of guilt for D is also sizable (see Sect. A in Appendix for details). Second, payoffs ensure that if D opts for Return, the level of restoring probability \(\lambda\) neither affects the final efficiency nor inequality. Thus, if D is motivated by outcome-based social preferences, such as fairness (Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000) or efficiency concerns (Charness and Rabin 2002), she should choose Return irrespective of the value of \(\lambda\). The value of \(\lambda\) is private information of D; ER and UR only know that \(\lambda\) can take values 4/6, 5/6, or 6/6, with equal likelihood.Footnote 3 As in Charness and Dufwenberg (2006), ER and UR do not observe D’s action. Thus, ER cannot infer whether D kept the wallet or Nature misplaced it.

The experimental session: Two groups of subjects participated in each session, group A and group B. Group A members actively participated in all stages of the experiment and played either in the role of dictators or entitled recipients (Fig. 2). Group B members, who acted as unentitled recipients, actively participated only in the beliefs’ elicitation stage and were free to surf the Internet during other stages.Footnote 4

At the beginning of a session, group A members performed a real-effort task to earn their wallet. They had to count the number of zeros in seven \(15\times 8\) tables containing 0 and 1 digits in random proportions, which sequentially appeared on their computer screens. For each table solved, they earned 1 token (1 token = €1). Subjects were not time-constrained and could make mistakes. At the end of the task, each group A member virtually owned a wallet of 7 tokens.Footnote 5

After the task, group B also joined the session, and we read the instructions for the remaining stages of the experiment, i.e., the elicitation of expectations and the dictator game. To ensure a good understanding of the instructions (Bigoni and Dragone 2012), we complemented our instructions and software with illustrations, slides summarizing instructions, and control questions (see Sect. D in Appendix). The dictator game was repeated for three rounds, each time with a different \(\lambda\) value (4/6, 5/6, or 6/6) in random order (randomized across sessions), unknown to ER and UR. Roles were fixed, and subjects were rematched after every round with a perfect strangers protocol. Only one of the three rounds was randomly drawn for the payment.

To rule out false consensus effects, we induced guilt feelings by providing D with ER’s first-order expectation (see Ellingsen et al. 2010, for a discussion). Before the game, we asked all members of groups A and B to state how many times out of the three rounds of the game they expected a generic D to return the wallet (Table 1). We rewarded subjects for the accuracy of their expectation through an incentive-compatible mechanism. At the end of the session, one choice of a dictator—different from the one used to pay the game—was randomly selected. If the selected choice was Return, the more optimistic, the stated expectation the higher the reward (computed via a quadratic scoring rule). Instead, if the choice was Keep, the less optimistic the expectation, the higher the reward. To avoid the omission of relevant information, before the elicitation, we informed group A members that their expectations could be disclosed to dictators during the game.Footnote 6

Procedures: The experiment was programmed and conducted with z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007) at the Cognitive and Experimental Economics Laboratory (CEEL) of the University of Trento between April and September 2013. A total of 180 students took part in 12 sessions of 15 participants each (10 in group A and 5 in group B). Subjects were recruited via email using a dedicated software developed at CEEL.Footnote 7 All subjects received a show-up fee of €3.

3.2 Predictions and hypotheses

Standard theory predicts D to always choose Keep because \(\pi _D(Keep) > \pi _D(Return)\). Outcome-based social preferences, like altruism (e.g. Cox et al. 2008), inequity aversion (e.g., Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Fehr and Schmidt 1999), or efficiency concerns (e.g., Charness and Rabin 2002), can predict D to choose Return, but not to condition her choice upon the value of \(\lambda\) or ER’s expectations.Footnote 8 In contrast, the theories of equitable allocations (Konow 2000) and guilt aversion (Charness and Dufwenberg 2006) predict Return choices to depend upon the level of \(\lambda\) and ER’s expectation, respectively.

When D finds ER’s lost wallet, an unfair and inequitable allocation is induced because D and ER have exerted the same effort, but D obtains (almost) all the surplus and ER obtains nothing. D can restore justice by returning the wallet to ER. Even though the final allocation in the case of a successful return does not equalize the D and ER payoffs, it reduces the striking disparity between inputs and outputs resulting from D keeping the wallet. Instead, if Nature misplaces the wallet to UR, an even less equitable allocation is in place: the wallet is given to someone who did not exert any effort to generate it. If the probability of misplacing the wallet is zero, a justice concerned D should return the wallet to prevent ER from ending up with no reward for her work. Instead, if the likelihood of misplacement is high, D will likely prefer to keep the wallet. This choice provides D with an extra reward relative to the return choice and avoids the double injustice of a misplacement: on the one hand, ER does not receive what deserved and, on the other hand, UR receives what is not deserved.Footnote 9 So, for higher values of \(\lambda\), D should be more likely to return the wallet, irrespective of ER’s expectation. This leads to our first testable hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

(Distributional justice). For dictators aiming to preserve distributional justice, the likelihood of returning is increasing in the restoring probability (\(\lambda\)).

A guilt averse D experiences a psychological cost when letting ER down. The disappointment of ER is equal to the difference between what ER expected to obtain and her final payoff, i.e., zero in the case in which D keeps the wallet. D returns the wallet when the cost of guilt is large enough to overrule the material benefit of keeping it. In this respect, our belief elicitation presents a unique feature (see Table 1): ER cannot specify an expectation about D’s return decision for each value of \(\lambda\). ER can only report the number of Return choices she expects from D over the three rounds of the game (\(\beta \in \{0/3,1/3,2/3,3/3\}\)). Hence, a higher \(\beta\) should trigger the same degree of guilt in D irrespective of \(\lambda\) (see Sect. A of the Appendix for a formal derivation). This leads to the following testable hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

(Guilt aversion). For a guilt averse dictator, the likelihood of returning is increasing in the entitled recipient’s expectations of a return (\(\beta\)).

Our last hypothesis refers to the issue of beliefs’ legitimacy. Previous studies suggest that others’ expectations are effective in influencing behavior only when they are perceived as legitimate in the context faced by the decision-maker (Andreoni and Rao 2011; Bicchieri 2006; Balafoutas and Fornwagner 2017). We conjecture that a guilt averse decision-maker will perceive as illegitimate those expectations that would lead to taking an action that conflicts with justice considerations. More precisely, we test whether decision-makers are more likely to fulfill others’ expectations when doing so leads to an equitable distribution of the surplus. We expect a positive interaction between the restoring probability \(\lambda\) and ER’s expectation \(\beta\) on D’s decision to return the wallet: the positive impact of more optimistic expectations is strengthened by an institutional environment promoting equitable allocations; in contrast, when the institutional environment is weak, optimistic expectations are likely to be neglected. By the same token, if ER holds pessimistic expectations, D might not return even under a high \(\lambda\) level because the cost of guilt is trivial. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

(Guilt aversion with legitimate expectations). For guilt averse dictators aiming to preserve distributional justice, the positive impact of an optimistic expectation (\(\beta\)) on the likelihood of returning is stronger when the restoring probability is higher (\(\lambda\)).

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Expectations about dictator’s behavior

Group A members knew that their expectations could be disclosed to dictators. Group B members, instead, knew that their expectations were not going to be disclosed to dictators. By comparing expectations of groups A and B, we can test for strategic manipulation of expectations by group A members. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the expectation about D return decisions for groups A and B. We adopt the labels “Never”, “Seldom”, “Often”, and “Always” to identify expectations that range from 0 returns out of 3 rounds to 3 returns out of 3 rounds.

First-order expectations about dictator’s Return. The barplot shows the distribution of expectations over distinct return frequencies, from Never (0 returns in 3 rounds) to Always (3 returns in 3 rounds). As an example, the height of the bar in correspondence to Never captures the relative share of individuals believing that a generic dictator will never return the wallet. Different shades of gray identify the two groups in the experiment

Both in group A and group B, about 80% of the subjects expect D to choose to return in less than 2 out of 3 rounds, with the modal expectation corresponding to “Seldom” (1 out of 3). Although group A members are slightly more pessimistic than group B members, the two distributions are not statistically significantly different (Fisher’s exact test, \(p=0.117\)). We conclude that there is little evidence of expectations’ manipulation by group A members. Finally, we use earnings in the beliefs’ elicitation to measure beliefs’ accuracy (see Table 1). The median earnings in this task are equal to €4.40 for both A and B groups, just one step away from the maximum earnings of €5. Thus, beliefs are overall accurate in both groups.

3.3.2 Dictator’s decisions

Out of the 60 dictators, 28 (46.7%) never returned the wallet across all three rounds, and only 2 (3.3%) always returned it. Half of the subjects choose differently across rounds. This suggests that outcome-based social preferences are not a good fit to describe dictators’ behavior in our experiment. For a large share of dictators, both recipients’ expectations and restoring probabilities seem to affect return choices. When collapsing all levels of \(\lambda\), the lowest percentage of returns (17.5%) is observed in correspondence of the most pessimistic expectation “Never”, in line with the guilt aversion prediction of Hypothesis 2. However, in contrast to Hypothesis 2, the highest percentage of returns is observed in correspondence to the intermediate expectation “Seldom” (29.6%), rather than to the more optimistic expectation “Often” (25.6%).Footnote 10 When collapsing all expectations’ levels, consistent with Hypothesis 1 on justice considerations, the percentage of return choices is significantly higher for \(\lambda =6/6\) (30.0%) than for lower levels of \(\lambda\). Still, the percentage of returns for \(\lambda =4/6\) and \(\lambda =5/6\) is the same (21.7%).

Figure 4 shows the joint effect of expectations and restoring probabilities, reporting the percentage of returns for alternative levels of \(\lambda\) (rows) and ER’s expectation (columns). The percentage of returns monotonically increases in ER’s expectation only for \(\lambda =4/6\) (upper panel), with a statistically significant increase in return choices between the expectation levels “Never” and “Often” (Fisher’s exact test, \(p=0.029\)). In contrast, for \(\lambda =5/6\) and \(\lambda =6/6\) the impact of expectations is non-monotonic, with no significant differences in return choices in correspondence to the expectation levels “Never” and “Often” (\(p\ge 0.420\)).Footnote 11

Return choices by recipient’s expectations and restoring probabilities. Each barplot provides a representation of the frequency of dictator’s return choices, in percentage terms, for different categories of recipient’s expectations (\(\beta \)), from Never to Often (Always is omitted because only one observation is available). As an example, the height of the bar in correspondence to Never captures the relative share of dictators returning the wallet when the recipient believes that a dictator will never return the wallet. Different panels capture different restoring probabilities (\(\lambda \))

3.4 Regression analysis

The analysis reported above suggests that both restoring probabilities and entitled recipients’ expectations have a positive impact on return decisions, even though the effects are not fully in line with Hypotheses 1 and 2. Expectations and restoring probabilities seem to interact in shaping dictator choices. Here we present a regression analysis that casts light on the interaction between these behavioral drivers.

Table 2 reports the outcomes of Probit regressions on the decision to return, controlling for repeated choices via clustered robust standard errors at the individual level.Footnote 12 To test Hypothesis 3 of guilt aversion with legitimate expectations, we include as main covariates the restoring probability \(\lambda\), the expectation of the entitled recipient \(\beta\), and their interaction. In Model 2, we add a control for the subject’s characteristics collected at the end of the experiment. In Model 3, we investigate the impact of the dictator’s expectation and the relative standing of this expectation relative to that of the matched entitled recipient.Footnote 13

All regressions show that higher restoring probabilities increase the likelihood of return, providing support to the relevance of justice considerations. At the same time, the positive and statistically significant coefficient of “Recipient’s expectation (\(\beta\))” suggests that dictators facing more optimistic recipients are, on average, more likely to return. This provides support to guilt aversion.Footnote 14 The coefficient of the interaction term is significant and negative. This runs against our Hypothesis 3, stating that the positive effect of the recipient’s expectation would be strengthened by a choice environment favoring an equitable outcome. The effect of optimistic expectations versus pessimistic expectations is thus weaker under higher restoring probabilities.

Finally, in Model 3, we find that the dictator’s expectation about the behavior of others in the same role is positively correlated to her decision to return (“Dictator expectation”). This pattern is compatible with false-consensus bias. Moreover, when the expectation of the entitled recipient is more optimistic than that of the dictator (“Recipient’s expectation > dictator’s expectation”), returns are less likely. A possible interpretation is that the counterpart’s expectations that are perceived as exorbitant relative to own expectations can discourage returns.

3.5 Robustness check

When interpreting results from Study 1, we ascribe the drop in return rates for lower values of \(\lambda\) to different justice assessments of final allocations by D. An alternative explanation could be the presence of a self-serving bias resulting from D’s exploitation of a “moral wiggle room” (e.g., Dana et al. 2007). This explanation might also rationalize the non-linear effect of \(\lambda\), whereby the return rate drops substantially once uncertainty is introduced (\(\lambda <1\)), but not so when uncertainty increases further. We designed an additional experiment differing from Study 1 in a key aspect: return decisions are taken by an external spectator instead of D.Footnote 15 Since the external spectator is paid a flat fee and has no monetary stake in the interaction, there is no scope for a self-serving bias to influence return decisions.

We recruited six participants to play in the roles of D, ER, and UR and 180 participants to play in the role of external spectators from the online platform Prolific.Footnote 16 At the beginning of the experiment, we described to external spectators the setup of Study 1 up to the point where ER lost her wallet and told them that they were asked to take return decisions. We stressed that their decisions could be selected to actually pay participants playing the roles of D, ER, and UR. Each external spectator was randomly assigned to one of the three values of \(\lambda\), leaving us with 53 spectators facing \(\lambda =4/6\), 62 facing \(\lambda =5/6\), and 65 facing \(\lambda =6/6\). Thus, \(\lambda\) was experimentally manipulated in a between-subject fashion, differently than in Study 1. Moreover, external spectators were asked to take four return decisions, one for each possible first-order belief level of ER about the decision of a generic external spectator to choose to return (strategy method; see Bellemare et al. 2018, for a discussion in the context of guilt aversion).Footnote 17 This element of the design differs from Study 1, where D participants experienced different combinations of \(\lambda\) and expectations at random, but allowed us to collect a more balanced number of return choices for each combination of ER’s expectation and \(\lambda\) values. Once the data collection was complete, we randomly selected two external spectators and matched each of them with a triplet, including D, ER, and UR participants. We paid these participants according to the spectator’s return decision, corresponding to the actual expectation level stated by ER. More details on this experiment are in Sect. B of the Appendix.

Figure 5 shows the joint effect of ER’s expectations and restoring probabilities on return choices. The percentage of returns is plotted by expectation categories. Each panel refers to a different restoring probability. The percentages of returns are generally higher than those observed in Study 1 (see Fig. 4). However, the overall impact of \(\beta\) and \(\lambda\) are comparable across the two studies. Expectations have a positive impact on return choices, but their effect is not strictly monotone. As in Study 1, expectations appear to play a more important role under \(\lambda =4/6\). Restoring probabilities also affect return choices positively, especially under more pessimistic expectations. Regression results are in line with those of Study 1 (see Table 2), confirming the positive and statistically significant effects of \(\beta\) and \(\lambda\) (\(p<0.05\), see Table 4 in Appendix), as well as the negative interaction between the two dimensions (\(p<0.05\)).

Return choices by recipients’ expectations and restoring probabilities—Robustness check. Each barplot provides a representation of the frequency of return choices, in percentage terms, for different categories of first-order expectations of recipients (\(\beta \)), from 0–25% to 76–100%. As an example, the height of the bar in correspondence to 0–25% captures the relative share of external spectators returning the wallet when the recipient believes that a generic eternal spectator is very unlikely to return the wallet. Different panels capture different restoring probabilities (\(\lambda \))

To improve our understanding of the determinants of return choices, we also asked external spectators about the social appropriateness of choosing to return on a four-point Likert scale, given each ER expectation level and the specific restoring probability they had faced. For each spectator, we then selected at random one of the four submitted evaluations. Participants knew that if the selected evaluation corresponded to the modal evaluation in the experiment (given the same \(\lambda\) level), they would earn an additional bonus of 0.50 GBP. This incentive scheme, based on a coordination game, has been introduced by Krupka and Weber (2013) to identify social norms in experimental games. We find that both expectations and restoring probabilities affect the perceived social norm in the same direction of choice data: lower levels of the two factors are associated with lower levels of perceived social appropriateness (a detailed analysis is available in Sect. B.2 of the Appendix). This suggests that the two justice factors not only impact on allocation choices but also on the perception of social norms.

4 Study 2

The robustness check experiment mitigates the concern of a self-serving bias driving the results of Study 1. Yet, Study 1 and its robustness check are not immune to some other caveats that could hamper a clean identification of justice concerns. The payoffs’ structure could be somewhat confusing to participants (see footnote 2 for a discussion). Moreover, it remains questionable that the least preferred outcome for a D motivated by restoring justice is truly the one where the UR gets the wallet. We hence implemented a second experiment where these caveats are absent. Furthermore, Study 2 helps to corroborate the evidence from Study 1 by testing Hypotheses 1–3 in a different setup.

4.1 Experimental design

The experiment inspired by Almås et al. (2020) includes two types of sessions: the Worker sessions and the Spectator sessions. Below, we describe them in detail.

Worker session: Participants in the Worker session had 5 min to work on a task, which consisted of solving as many sums as they could. They had to add up five numbers of two digits each; all digits were randomly generated at the individual level. A worker only moved to the next problem once she entered the correct solution to the current problem. Following Almås et al. (2020), participants were not informed before the task of the precise payment scheme. They only knew that they would receive €3 and that they could earn additional money through their actions and the actions of other participants. Moreover, we made clear that we would record their effort and that they received one point for every correct answer.

After the task, we informed participants that we would form pairs of workers and that an external third party (i.e., the spectator) would have to assign additional €6 to one of the two workers. They were also informed that the spectator would know who in the pair was the most productive worker and that their identity would remain anonymous. Finally, we asked workers to state their expectations. We asked first with which probability they expected to be the worker in the pair with the highest number of correctly solved problems. We then asked them to state their expectation of being selected by the spectator to receive the additional €6. This latter expectation is our proxy of the worker’s first-order beliefs about the spectator’s behavior.

Since first-order beliefs are key for the identification of guilt aversion, we gave workers an incentive to truthfully report them via a quadratic scoring rule.Footnote 18 Workers were informed that their expectations could be disclosed to the spectator. We did so to avoid the omission of relevant information.

Spectator session: Spectators were paid a flat fee of €7 and were provided with a brief description of the Worker session. Next, they were individually presented with 20 pairs of workers. For each pair, every spectator had to choose to which of the two workers to assign €6.Footnote 19 Alternatively, spectators could choose to assign the money to one of the two workers selected at random via a virtual coin flip.Footnote 20 When making her decision, the spectator only knew who was the most productive worker in the pair and who between the two workers had the highest expectation of obtaining the reward. We opted for this binary information to simplify our analysis, as it is robust to outliers and does not require to control for the distance between workers’ productivity and expectations. Given this choice constraint, spectators could not reward workers in exact proportion to their input, but could still decide to minimize the distance between inputs and outputs by rewarding the most productive worker. Taking into account that two workers may have the same expectation and the same productivity, we face nine possible combinations of relative performance and relative expectation.Footnote 21

At the end of the session, we randomly selected one spectator, and all 20 pairs of workers were paid according to the allocation decisions of the selected spectator. Before the payment, we asked all spectators to fill the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (henceforth TOSCA-3, Tangney et al. 2000) to gather a more direct measure of their guilt sensitivity (Bellemare et al. 2019).Footnote 22

Procedures: We first conducted two Worker sessions of 20 subjects each, and then three Spectator sessions of 20 subjects each. Participants were ex-ante unaware of whether they signed up for workers’ or spectators’ sessions. All sessions were conducted at CEEL using z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007). Instructions are in Sect. C.1 of the Appendix.

4.2 Predictions and hypotheses

The third party is an external spectator who has no material stake in the reward assignment but can still suffer psychological costs when disappointing the workers’ expectations and/or violating distributional justice principles. Therefore, while the experimental setup is different form Study 1, Hypotheses 1–3 can be reiterated in Study 2 as well. An important difference between the two studies lies in the definition of the entitlement rights to the reward. In Study 1, all participants knew who the entitled recipient was, while in Study 2, workers could only conjecture about their merit to be rewarded when stating their expectations.

Since spectators in Study 2 know the relative performance of the two workers, we can reformulate Hypothesis 1 of Study 1: spectators aiming at preserving distributional justice should assign the reward to the worker who showed to be more productive. Higher productivity is taken here as a proxy of higher investment (input) in the production phase that, according to our general justice principle, calls for higher rewards (output). Support to this conjecture also comes from Almås et al. (2020), who show that the majority of participants in their experiment rewarded the more productive workers.

Differently than in Almås et al. (2020), spectators were also informed about the workers’ relative expectations of receiving the reward from the spectator. These expectations are our proxy for the worker’s first-order beliefs about the behavior of the spectator. As in Study 1, we assume that by communicating the workers’ relative first-order beliefs to the spectator we can exogenously manipulate the spectator’s second-order beliefs, which represent the source of guilt feelings. Hence, we can test the relevance of expectations in the same vein of Hypothesis 2 in Study 1: if the spectator is guilt averse, the worker with higher expectations to obtain the reward should be the one to obtain it.

We are particularly interested in conditions that create tension between productivity and expectations. Situations in which a worker in the pair has higher (lower) expectations and the other worker performed worse (better) are key to test our hypotheses on beliefs’ legitimacy. Following the line of reasoning of Hypothesis 3 in Study 1, we should observe a positive interaction effect on the probability of receiving the reward when a worker has both the higher productivity and the higher expectation. Indeed, optimistic expectations of obtaining the reward are legitimate in this setting only when they are matched by higher productivity, given that beliefs originate in the subjective expectation of being the most productive worker in the pair.

4.3 Results

4.3.1 Workers’ expectations

Our data reveal that workers are generally well-calibrated in their expectations, with a median reported expectation of 50% for both the probability of being the most productive in the pair and for the probability of being rewarded by the spectator. The overall soundness of expectations is also confirmed by the strong correlation between the beliefs about one’s own relative productivity and actual productivity (Spearman’s rank correlation \(\rho = 0.764\), \(p<0.001\)).

The comparison of beliefs about being rewarded and being the most productive in the pair allows us to gain an insight into workers’ perception of the criterion adopted by the spectator to assign the reward. In line with our design assumptions, the two sets of beliefs are positively correlated (Spearman’s rank correlation \(\rho = 0.670\), \(p<0.001\)). Thus, the expectation of being rewarded seems mainly driven by the belief about the relative productivity in the pair, with those who believe to be more productive entertaining higher expectations of being rewarded.

4.3.2 Spectators’ choices

Out of the 1200 spectators’ choices we collected, only 9.8% are associated with the use of the random device to allocate the reward. The use of the random device is mainly associated with choices in which the two workers are not distinguishable in terms of relative performance and/or expectations (80.2%). The following analysis focuses only on actively expressed choices, for random choices carry no informative content.

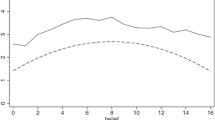

Figure 6 shows the frequency of reward allocation for different combinations of relative performance and relative expectation. When a worker solved fewer (more) problems than the matched subject, her relative performance is equal to Worse (Better). When the two workers solved the same number of problems, the relative performance is equal to Same. Similarly, when a worker has higher expectations about receiving the reward, her relative expectation is equal to Higher (Lower). When the two workers have the same expectation, the relative expectation is equal to Same.

Reward choices by relative efforts and expectations. Each barplot provides a representation of the relative frequency, in percentage terms, of reward choices for different relative expectations of recipients, from lower to higher. As an example, the height of the bar in correspondence to lower captures the share of workers being rewarded when they have lower expectations than those of the other worker they are matched with. Different panels capture different levels of relative performances

The overall probability that a worker with a better relative performance obtains the reward is equal to 97.2%, while the overall probability for a worker with higher relative beliefs is equal to 72.5%. Figure 6 shows that, when combining the two dimensions, the highest likelihood of obtaining the reward is observed when a worker has both higher expectations and better performance (98.1%). A better relative performance strongly increases the likelihood of receiving the reward relative to both the same and worse levels for all relative expectation levels. This finding provides support to the distributional justice hypothesis (Hypothesis 1). A similar pattern is qualitatively observed also for higher expectations, though the effect is much more moderate than for relative performance. The marginal impact of different relative expectation levels is very small with reference to workers who display better performance.Footnote 23 Thus, the guilt aversion hypothesis (Hypothesis 2) is only moderately supported by our data.

Non-parametric tests show that there is little difference in the likelihood of being rewarded for different levels of relative expectations, given the level of relative performance (Wilcoxon signed rank test, \(p \ge 0.083\)).Footnote 24 In contrast, when keeping fixed the level of relative expectations, higher levels of relative performance significantly increase the likelihood of being rewarded (Wilcoxon signed rank test, \(p \le 0.005\)). A full assessment of the main effects of our treatment variables and thier interaction is provided in the regression analysis below.

4.3.3 Regression analysis

Table 3 reports the outcome of Probit regressions, controlling for repeated choices via individual-level clustered robust standard error. The dependent variable Rewarded is equal to 1 for the worker rewarded by the spectator and equal to 0 for the unrewarded worker. As explanatory variables, we consider the relative performance and the relative expectation of the worker to whom the choice of the spectator refers. Specifically, PerfBetter is equal to 1 when the worker performed better than the matched worker, and equal to 0 otherwise. ExpHigher is equal to 1 when the worker has a higher expectation of receiving the reward than the matched worker, and equal to 0 otherwise.Footnote 25 Finally, GuiltAverse is a measure of guilt aversion obtained from the TOSCA-3 questionnaire. Specifically, if a subject obtains a score in the questionnaire equal or greater than the median score, the variable has value 1, otherwise it is equal to 0.Footnote 26 In Model 1, we consider only the main effects of the performance and expectation variables. In Model 2, the interaction between the two variables is also considered. Finally, in Model 3, we control for guilt sensitivity and for its interaction with the beliefs of the counterpart.

The regression outcomes of Table 3 confirm the strong impact of a better performance in increasing the likelihood of receiving the reward. A positive and significant impact is also observed for higher expectations, even though the effect is only marginally significant and much smaller than that estimated for the measure of relative performance.Footnote 27 Model 2 shows that the two measures taken into account register a significant negative interaction: the effect of optimistic expectations is weaker when merit is salient.Footnote 28 Thus, the evidence runs against our Hypothesis 3, similar to Study 1. The effect is also observed when controlling for guilt aversion of the decision-maker, but the impact of expectations becomes statistically not significant (Model 3).

5 Conclusions

Several experiments have shown that decision-makers tend to be averse to let others down to avoid guilt (Charness and Dufwenberg 2006). We contribute to the literature by studying how decision-makers react to expectations that they may or may not perceive as legitimate, given the choice environment they face. Relying on previous evidence in the literature, we conjecture that decision-makers are more likely to fulfill their counterpart’s expectation when this is perceived as legitimate, i.e. when it is in line with the decision-maker’s justice considerations (Konow 2000).

In Study 1, we argue that a dictator could perceive as legitimate an optimistic expectation when such expectation is not at odds with justice principles based on the proportionality between effort exerted and rewards obtained. Similarly, in Study 2, the legitimacy of expectations is assessed against the relative performance of two workers in a simple task. An external spectator could perceive as legitimate a worker’s expectation to be rewarded only when such a worker performed better than a competing worker.

Results from our studies generally support the hypotheses that others’ expectations and justice considerations are important drivers of decision-making. However, in Study 2, the impact of expectations seems weaker than in Study 1. This may be explained by the different institutional settings that nurture the beliefs of the interacting parties. In Study 2, they are merely based on the subjective expectation of being the most productive worker in the pair. Thus, the external spectator may have primarily focused on the objective measure of productivity and only secondarily on others’ expectations. Differently, in Study 1, the expectations of an individual who lost her wallet are grounded in an objective measure of entitlement (having worked to earn the wallet). Thus, they may be more relevant for decision-makers, especially when justice consequences are more ambiguous.

Our results unanimously suggest that others’ expectations are more salient in some contexts than others (Tangney 1992). However, contrary to our initial conjecture, guilt aversion and justice considerations do not reinforce each other. Decision-makers tend to give less weight to their counterparts’ expectations when it is clear how to enforce distributional justice. In Study 1, when the restoring probability is high, dictators return the wallet to the entitled owner even if she holds pessimistic expectations. A similar result is obtained in a robustness check where the decision-maker had no stake in the interaction, thus ruling out the confound of a self-serving bias triggered by the exploitation of moral wiggle rooms (Dana et al. 2007). In Study 2, external spectators tend to reward the best worker even if she is relatively more pessimistic than the other one. Decision-makers rely more on others’ expectations when the risk that distributional justice will be (exogenously) violated is high or when merit is unclear.

We believe that this result may deserve further attention by future research as it provides stimulating insights into the working of distributional norms. Data collected suggest that when the distributional norm is clear, descriptive expectations of others become almost irrelevant for the decision-maker, which will likely follow the norm in any case. Instead, when the distributional norm is less clear, individuals may rely more on a subjective measure of justice, as captured by the counterpart’s expectation, which triggers a sense of guilt when disappointed.

Notes

As in other experiments testing guilt aversion, we focus on a binary decision rather than allowing D to choose an amount to return. This feature restricts the decision-makers’ action space relative to a continuous specification. However, a decision-maker can still choose the action that better meets her motivations.

The higher valuation of ER for her wallet could be interpreted as some intrinsic value she attaches to it. This interpretation, however, is less suitable to justify payoffs when the wallet is misplaced: realism would require UR and D to give the same value to ER’s wallet.

Different \(\lambda\) values capture different degrees of protection to the entitlement right of ER due to exogenous institutional aspects.

Interactions between groups A and B were avoided. Group B joined the session 10 min later and left earlier than group A. We let group B members surf the Internet to highlight their lack of effort and entitlement on the lost wallet.

We adopted this real-effort task by Abeler et al. (2011) because it is arguably more related to effort provision than knowledge tests (used, for instance, by Cherry et al. 2002) in which human capital and luck are key. Different from Abeler et al. (2011), all group A members ended up with the same endowment. We did this to ease the empirical analysis. We believe that the task successfully conveyed a sense of entitlement to group A for three reasons. First, in the instructions (see Sect. C.1 of the Appendix), group A members were clearly told that their earnings were a piece-rate reward for each table they had to solve (we did not use the word wallet). Second, the task lasted, on average, 10 min, a non-trivial fraction of the duration of a session (roughly 1 h). Third, during the real-effort task, group B members were not yet in the lab.

This design choice might raise the concern that group A members could strategically manipulate their expectations. However, we carefully designed the belief elicitation to discourage such behavior. First, subjects had a monetary incentive to reveal their true expectations. Second, expectations were elicited before roles were assigned to subjects. Finally, we can control for this issue ex-post, by comparing the expectations’ distributions of groups A and B; group B members knew their expectations were not going to be disclosed to dictators.

The average age of participants is 23 years, females are 49.4% of the sample, and 90% of participants have Italian citizenship. About half of the sample (56.1%) is made of students of Economics, and most of the participants do not actively work (68.3%).

If D is efficiency concerned, she chooses Return because this maximizes total earnings regardless of \(\lambda\). Under the assumption of inequity aversion, D also opts for Return regardless of \(\lambda\) because this minimizes the inequality. The same prediction holds under a procedural version of the model (Trautmann 2009). Taking the expected value of the Return lottery generates an even fairer allocation than in the standard consequentialist framework. Thus, unlike in other settings (e.g., Krawczyk and Le Lec 2010), uncertainty does not affect inequality predictions. Finally, pure altruism also leads D to always choose Return.

Gill and Stone (2010) argue that when one gets more than what is deserved, she can either experience a welfare gain (desert elation) or a welfare loss (desert guilt). However, when the other gets less than what is deserved, a loss of welfare is unambiguously experienced (desert loss). Moreover, they assume that welfare changes when receiving less than what deserved are larger than changes in welfare when receiving more as a result of loss aversion.

We neglect the expectation level “Always” because only one observation is available. The number of independent observations for the other expectation levels are as follows: 19 (31.7%) for “Never”, 27 (45.0%) for “Seldom”, and 13 (21.7%) for “Often”.

For any \(\lambda\), the comparisons of “Never” and “Seldom”, and of “Seldom” and “Often” do not reveal any significant difference (\(p\ge 0.115\)).

In an exploratory step, we also estimated a linear model. Results are consistent with those from the generalized linear model reported here and are available upon request.

Variables relating to the dictator’s own expectation may suffer from endogeneity, which makes it hard to give a causal interpretation of the results.

We cannot fully rule out that dictators suspected that entitled recipients manipulated their expectations (see footnote 6). If this were the case, they would be arguably less likely to fulfill them. Thus, we take this effect as a lower bound.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this additional study.

We implemented the experiment online because the CEEL laboratory at the University of Trento was temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We minimized differences between the online sample and Study 1 sample by restricting participation only to students between 18 and 30 years old. Females were 42.7% of the sample, and the average age was 27. Subjects were only allowed to take part in the experiment using a computer or a tablet and not a smartphone. We could not restrict participation to Italians only because this additional requirement was too restrictive.

Note that ER’s expectations in Study 1 referred to the number of return decisions of D, knowing that D was facing three levels of \(\lambda\). Given that in the robustness check each external spectator faced only one \(\lambda\) level, we could not elicit the same type of expectation. Thus, we elicited expectations over four non-overlapping equally-spaced intervals that referred to the frequency of returns for the entire population of external spectators.

The payoff, in Euro, for the belief task is given by \(S_i(p)=2-\frac{1}{10,000}\sum _{k=1}^2 (I_k-p_k)^2\), where I is equal to 1 when the event i is realized and equal to zero otherwise. As an example, when a worker reported a 70% probability of being rewarded, he/she would earn €1.82 when actually rewarded and €1.02 when not rewarded. The earnings for all combinations of probabilities and outcomes were reported on the computer screen, but the underlying function was not to avoid potential confusion. All workers had to come back to the lab two days after the session to collect their payment for the accuracy of their first-order beliefs, and, possibly, the reward of €6.

Pairs of workers were randomly formed at the spectator-level. We did not disclose the type of task that the workers performed.

Workers knew about this possibility, and spectators, in turn, knew that the worker who obtained the €6 would learn whether this was the outcome of a deliberate decision or of the coin flip.

The following frequencies of alternative combinations are empirically observed: better performance/higher expectation (52.8%), better performance/lower expectation (20.0%), better performance/same expectation (16.3%), same performance/higher expectation (6.8%), same performance/same expectation (4.2%).

We adopted the Italian translation of TOSCA-3 by Anolli (2010).

Choices of spectators are very consistent at the individual level, with only 16.7% choosing differently across repetitions for conditions not involving the same level of expectation and performance.

To perform the tests, we compare the average choice of a spectator in a given condition with the average choice of the same spectator in a different condition. This way, we circumvent dependency issues in the data due to repeated choices. We omit from the analysis the conditions involving the same relative performance and the same relative expectations, as the number of observations available is too low.

In a series of exploratory regressions, we distinguished between better, equal, and worse performance and between higher, equal, and lower beliefs. We decided to choose the specification reported here, which pools together equal and lower expectation and equal and worse performance, because of the few observations available for equal levels of the two variables in our couples. The main results do not change across specifications.

The TOSCA-3 questionnaire we administered delivered information also about shame, pride, externalization, and unconcern. We focus here only on the variable of our interest, i.e., guilt.

A series of linear hypothesis tests show that the estimated coefficients of PerfBetter and of ExpHigher are significantly different across all specifications (\(\chi ^2\) test, \(p<0.001\)).

In an exploratory step, we also estimated a linear model. Results are overall consistent with those obtained from the generalized linear model reported here and are available upon request.

References

Abeler, J., Falk, A., Goette, L., & Huffman, D. (2011). Reference points and effort provision. American Economic Review,101(2), 470–492.

Adams, S. J. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,67(5), 422–436.

Almås, I., Cappelen, A., & Tungodden, B. (2020). Cutthroat capitalism versus cuddly socialism: Are Americans more meritocratic and efficiency-seeking than Scandinavians? Journal of Political Economy,128(5), 1753–1788.

Andreoni, J., & Rao, J. M. (2011). The power of asking: How communication affects selfishness, empathy, and altruism. Journal of Public Economics,95(7–8), 513–520.

Anolli, L. (2010). La vergogna. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Babcock, P., Bedard, K., Charness, G., Hartman, J., & Royer, H. (2015). Letting down the team? Social effects of team incentives. Journal of the European Economic Association,13(5), 841–870.

Bacharach, M., Guerra, G., & Zizzo, D. (2007). The self-fulfilling property of trust: An experimental study. Theory and Decision,63(4), 349–388.

Balafoutas, L., & Fornwagner, H. (2017). The limits of guilt. Journal of the Economic Science Association,3(2), 137–148.

Battigalli, P., & Dufwenberg, M. (2007). Guilt in games. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings,97(2), 170–176.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin,115(2), 243–267.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1995). Personal narratives about guilt: Role in action control and interpersonal relationships. Basic and Applied Social Psychology,17(1–2), 173–198.

Bellemare, C., Sebald, A., & Strobel, M. (2011). Measuring the willingness to pay to avoid guilt: Estimation using equilibrium and stated belief models. Journal of Applied Econometrics,26(3), 437–453.

Bellemare, C., Sebald, A., & Suetens, S. (2018). Heterogeneous guilt sensitivities and incentive effects. Experimental Economics,21, 316–336.

Bellemare, C., Sebald, A., & Suetens, S. (2019). Guilt aversion in economics and psychology. Journal of Economic Psychology,73, 52–59.

Bicchieri, C. (2006). The grammar of society: The nature and dynamics of social norms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bigoni, M., & Dragone, D. (2012). Effective and efficient experimental instructions. Economics Letters,117(2), 460–463.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193.

Cappelen, A. W., Hole, A. D., Sorensen, E. O., & Tungoddedn, B. (2007). The pluralism of fairness ideals: An experimental approach. American Economic Review,97(3), 818–827.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnership. Econometrica,74(6), 1579–1601.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quarterly Journal of Economics,117(3), 817–869.

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, c., (2016). oTree-An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance,9, 88–97.

Cherry, T. L., Frykblom, P., & Shogren, J. F. (2002). Hardnose the dictator. American Economic Review,92(4), 1218–1221.

Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Sadiraj, V. (2008). Revealed altruism. Econometrica,76(1), 31–69.

Dana, J., Weber, R. A., & Kuang, J. X. (2007). Exploiting moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Economic Theory,33(1), 67–80.

Danilov, A., Khalmetski, K. & Sliwka, D. (2018). Norms and guilt. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 6999.

Dufwenberg, M., Gächter, S., & Hennig-Schmidt, H. (2011). The framing of games and the psychology of play. Games and Economic Behavior,73(2), 459–478.

Ellingsen, T., Johannesson, M., Tjøtta, S., & Torsvik, G. (2010). Testing guilt aversion. Games and Economic Behavior,68(1), 95–107.

Engelmann, D., & Strobel, M. (2000). The false consensus effect disappears if representative information and monetary incentives are given. Experimental Economics,3(3), 241–260.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics,114(3), 817–868.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics,10(2), 171–178.

Gill, D., & Stone, R. (2010). Fairness and desert in tournaments. Games and Economic Behavior,69(2), 346–364.

Hoffman, E., & Spitzer, M. L. (1985). Entitlements, rights, and fairness: An experimental examination of subjects’ concepts of distributive justice. Journal of Legal Studies,14(2), 259–297.

Ketelaar, T., Au, T.W., (2003). The effects of feelings of guilt on the behaviour of uncooperative individuals in repeated social bargaining games: An affect-as-information interpretation of the role of emotion in social interaction. Cognition and Emotion,17(3), 429–453.

Konow, J. (1996). A positive theory of economic fairness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization,31(1), 13–35.

Konow, J. (2000). Fair shares: Accountability and cognitive dissonance in allocation decisions. American Economic Review,90(4), 1072–1091.

Konow, J. (2003). Which is the fairest one of all? A positive analysis of justice theories. Journal of Economic Literature,XLI, 1188–1239.

Krawczyk, M., & Le Lec, F. (2010). ‘Give me a chance!’ An experiment in social decision under risk. Experimental Economics,13(4), 500–511.

Krupka, E. L., & Weber, R. A. (2013). Identifying social norms using coordination games: Why does dictator game sharing vary? Journal of the European Economic Association,11(3), 495–524.

Leventhal, G. S., & Michaels, J. W. (1969). Extending the equity model: Perceptions of inputs and allocation of reward as a function of duration and quantity of performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,12(4), 303–309.

Mikula, G. (1974). Nationality, performance, and sex as determinants of reward allocation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,4, 425–440.

Nelissen, R. M. A., Dijker, A. J. M., & de Vries, N. K. (2007). Emotions and goals: Assessing relations between values and emotions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology,21(4), 902–911.

Pelligra, V., Reggiani, T., & Zizzo, D. J. (2020). Responding to (un)reasonable requests by an authority. Theory and Decision, 1–25.

Reuben, E., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2009). Is mistrust self-fulfilling? Economics Letters,104(2), 89–91.

Tangney, J. (1992). Situational determinants of shame and guilt in young adulthood. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,18(2), 199–206.

Tangney, J., Dearing, R., Wagner, P., & Gramzow, R. (2000). The test of self-conscious affect-3 (TOSCA-3). Fairfax: George Mason University.

Trautmann, S. T. (2009). A tractable model of process fairness under risk. Journal of Economic Psychology,30(5), 803–813.

Vanberg, C. (2008). Why do people keep their promises? An experimental test of two explanations. Econometrica, 76(6), 1467–1480.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maria Bigoni, Stefania Bortolotti, Marco Casari, Jan Potters, Sigrid Sueterns, two anonymous reviewers, and the associate editor for their helpful comments and support. We are indebted to audiences of seminars at the universities of Innsbruck and Bologna, as well as attendees of the VII GRASS Workshop in Pisa, the International Workshop on Social Norms and Social Preferences in Trento, and the 11th Workshop on Social Economy for Young Economists in Forlì for insightful comments. We acknowledge financial support from a grant by the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Trento within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A Derivation of Hypothesis 2 for Study 1

A guilt averse D who chooses to keep the wallet obtains a material payoff of 12 but suffers a cost of guilt increasing in ER’s disappointment. The disappointment of ER is measured by the difference between what ER expected to obtain and her final payoff, which is 0 in the case in which D keeps the wallet. Instead, a guilt averse D who returns the wallet will obtain a lower material payoff of 9, but his sense of guilt will be null because he did his best to fulfill ER’s expectation. So, D returns the wallet only if the cost of guilt is large enough to overrule the material benefit of keeping ER’s wallet, i.e. when \(12-\theta \bigl (E_{ER}(\pi _{ER})-0\bigr ) > 9\), where \(\theta >0\) is d’s guilt sensitivity and \(E_{ER}[\pi _{ER}]\) is the payoff er expected, which is equal to

where \(\beta _{\lambda }\in \{0,1\}\) is the probability with which ER expects D to return given a certain value of \(\lambda\). Two important features of the belief elicitation must be taken into account. First, we restrict the belief space: subjects can only state how many times out of three interactions they expect a generic D to return the wallet (Table 1). So, \(\beta _{\lambda }\) can only take value 0 (when D is expected to keep) or 1 (when D is expected to return). Second, subjects cannot specify an expectation \(\beta _\lambda\) for each value of \(\lambda\). Instead, they can only indicate the generic number of returns they expect from d over the three rounds, i.e. \(\beta =\beta _{\lambda =4/6}+\beta _{\lambda =5/6}+\beta _{\lambda =6/6}\) (with a slight abuse of notation). These two features of the belief elicitation are key to keep distinct guilt aversion and justice considerations. In particular, for higher \(\beta\), a guilt averse D is always more likely to choose to return irrespective of the faced \(\lambda\).

To derive the minimum guilt sensitivity threshold (\(\theta ^*\)) necessary to induce D to return the wallet, we would need to assume that ER deems more likely that D returns the wallet when \(\lambda\) is higher. As an example, when \(\beta =1/3\) ER expects D to return only when \(\lambda =6/6\), when \(\beta =2/3\) ER expects a return for \(\lambda =5/6\) and 6/6, and so on. However, it is important to remark that Hypothesis 2 still holds also under the more general assumption that \(dU(Keep)/d\beta <0\).

1.2 B Additional details on the robustness check of Study 1

1.2.1 B.1 Experimental design and procedures

The experiment consisted of two separate sessions: the worker session and the external spectator session. The worker session closely followed the procedures of Study 1, with only a couple of noteworthy differences. First, D was no longer asked to take the return decisions; this task was instead assigned to external spectators. Second, ER was no longer asked to estimate the number of return decisions by D, but the likelihood with which a generic external spectator would choose to return. We incentivized the elicitation of ER beliefs with a quadratic scoring rule very similar to the one used in Study 1. ER could choose among four probability intervals: 0–25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, or 76–100%. We constrained beliefs into four categories for comparability reasons with Study 1. Also, for comparability reasons, we chose to keep the same payoff structure of Study 1.

The spectator session was divided into two separate parts. Participants did not know the content of each part in advance. In part 1, we briefly described the worker session to external spectators and told them that they had to choose whether or not to return the lost reward to ER. For this task, they received a flat fee of 1.06 GBP. External spectators were randomly assigned to one value of the restoring probability \(\lambda\) equal to 4/6, 5/6, or 6/6. To avoid creating multiple sessions for the same experiment on Prolific, which could lead to the risk of sorting, the software implemented a true randomization of \(\lambda\) at the individual level. As a consequence, we collected slightly fewer observations for \(\lambda =4/6\) (N = 53) than for \(\lambda =5/6\) (N = 62) and \(\lambda =6/6\) (N = 65). We asked the external spectators to make four return choices, one for each level of the first-order beliefs of ER (strategy method).

In part 2, participants were asked to evaluate the social appropriateness of choosing to return, given each level of ER belief and the value of \(\lambda\) faced in part 1. Participants could obtain a bonus payment of 0.50 GBP for part 2 if one of their four evaluations selected at random matched the modal evaluation across all participants facing the same \(\lambda\) and belief level. This incentive scheme generates a coordination game, and it has been proposed by Krupka and Weber (2013) to identify social norms in experimental games.

Worker and external spectator sessions took place between June 12 and 13, 2020, on the online platform Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/). We restricted participation to students between 18 and 30 years old and who accessed the experiment using either a laptop or a computer (smartphones were not allowed). Each subject could only participate once in the experiment, either in the worker session or in the external spectator session. The experiment was programmed using oTree (Chen et al. 2016). To adapt the experiment to an online setup, we streamlined instructions compared to Study 1, and we omitted the quiz on instructions. Furthermore, thanks to the strategy method used for beliefs in the external spectator session, we were able to circumvent a real interaction between workers and external spectators. For simplicity, we first implement the worker session and then the worker session. Six subjects were recruited for the worker session, and 180 subjects were recruited for the spectator session. Both sessions lasted roughly 10 min on average. Each token earned in the worker session was converted to 1 GBP (the currency used on Prolific).

1.3 B.2 Empirical analysis

Table 4 reports the results of a regression analysis about the decision to return, controlling for repeated choices via clustered robust standard errors at the individual level. The dependent variable is the decision of an external spectator to return the wallet (\(1=\) Return, \(0=\) No return). The main explanatory variables are the restoring probability (\(\lambda\)), ER’s expectation (\(\beta\)), and their interaction. Furthermore, we control for gender and age of the external spectator. Both restoring probability and beliefs have a statistically significant, positive impact on the decision to return. Instead, the interaction term has a negative and significant sign. These regression outcomes corroborate the results reported above for Study 1 (see Table 2, model 2).

Table 5 summarizes the outcomes of the social norms elicitation à la Krupka and Weber. For each restoring probability and ER’s expectation, we report the frequency of external spectators who deemed the decision to return in that condition “Very inappropriate” (– –), “Somewhat inappropriate” (−), “Somewhat appropriate” (\(+\)), and “Very appropriate” (\(++\)). The modal value is identified in italics. Following Krupka and Weber (2013), we also report a score of social appropriateness computed by assigning value − 1 to – –, − 1/3 to −, 1/3 to \(+\), and 1 to \(++\) and computing the average. The lowest score of social appropriateness is detected for the lowest restoring probability level (\(\lambda =4\)) and the lowest expectation level (\(\beta\) = 0–25%), with 38% of the participants deeming return as “Very inappropriate”. At the other end of the spectrum, we find the score of social appropriateness in correspondence to the highest restoring probability (\(\lambda =6\)) and the highest expectation level (\(\beta\)= 76–100%), with 72% of the participants deeming return as “Very appropriate”. Thus, both beliefs and restoring probabilities seem to affect the perceived social norm, in the same direction identified by choice data. At a more detailed level, social appropriateness scores increase in expectation levels, but for 76–100% for \(\lambda =4/6\). Social appropriateness also generally increases in the restoring probability but for the intermediate expectation level 51–75%.

To test for differences in social appropriateness across alternative restoring probabilities, we compute the average score of appropriateness at the individual level for different expectation levels and a given \(\lambda\). A series of Wilcoxon rank-sum tests comparing averages across \(\lambda\) levels shows that there are no significant differences in scores (\(p>0.27\)). To test the impact of expectations, we pairwise compare scores for different belief levels across different \(\lambda\) levels. A series of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests shows that all differences between belief levels are statistically significant (\(p<0.044\)). These results are also confirmed by an ordinal logistic regression with random effects at the individual level (available upon request), showing that the explanatory variable capturing belief levels significantly and positively affects social appropriateness assessment while restoring probability has no statistically significant impact. However, when assessing these results, it must be taken into account the different nature of the elicitation of \(\lambda\) and \(\beta\). The latter is obtained in a within-subject setting that might have prompted an “ordering” of evaluations by the same individual, while the former is obtained from distinct individuals.

1.4 C Instructions

1.4.1 C.1 Study 1

The first 10 participants enter the lab.

Welcome!