Abstract

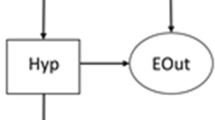

This paper seeks to carve out a distinctive category of conspiracy theorist, and to explore the process of becoming a conspiracy theorist of this sort. Those on whom I focus claim their beliefs trace back to simply trusting their senses and experiences in a commonsensical way, citing what they take to be authoritative firsthand evidence or observations. Certain flat Earthers, anti-vaxxers, and UFO conspiracy theorists, for example, describe their beliefs and evidence this way. I first distinguish these conspiracy theorists by contrasting them with another group that has recently received a lot of attention from the media, philosophers, and academics more broadly. I then dig more deeply into the nature of these conspiracy theorists’ epistemic self-understanding, in order to give an account of the process by which one becomes such a conspiracy theorist. I conclude with some takeaways and implications: first, I explore the implications of my account for whether these conspiracy theorists’ beliefs are rational; then, I argue that my account has practical takeaways about counteracting beliefs in misinformation, since strategies appropriate to this kind of conspiracy theorist may not be the same ones that are appropriate for other kinds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On the minimal definition of “conspiracy theory” I’m adopting, belief in conspiracy theories is distinct from conspiracy theories themselves: the conspiracy theory is the explanation of a phenomenon, and to believe a conspiracy theory is to believe that explanation. While some accounts conflate these two (e.g., Napolitano, 2021), I’ll follow Duetz (2022) in keeping them distinct. Furthermore, while I’ll frame my arguments simply in terms of Rowbothian “belief” in conspiracy theories, the reader is free to understand “belief” in a fairly broad sense. This could be a matter of what epistemologists call “full” or “outright” belief, and/or a matter of having credence 1 in a conspiracy theory. It could also mean merely taking a conspiracy theory to be likely true, or to be more plausible than not. Actual Rowbothians likely fall along the spectrum between mere high likelihood and outright belief, but I’ll gloss over this nuance in what follows.

I’m not assuming that being “anti-establishment” is necessarily an epistemic problem. Specifically, I’m not assuming that merely failing to fully trust mainstream sources of information makes one irrational or vicious (for discussion on both sides of this issue, see Harris, 2018; Hagen, 2022). I’m merely gesturing towards the kind of conspiracy theorist on whom I’m primarily focused: Rowbothians who claim the establishment is tricking the masses by covering up some observable fact.

For popular discussions, see Graziosi (2021), Siddharth and Murphy (2021), and Smith (2021); for discussion amongst philosophers, see Ichino (2022), Smith (2022), Buzzell and Rini (2023), Clarke (2023), Munro (2023), Levy (2022a), and Ganapini (2022); for a small sampling of academic discussion in areas outside philosophy, see Rosenblum and Muirhead (2019), Packer and Stoneman (2021), McIntosh (2022), and Beyer and Herrberg (2023). One issue I’ll set aside concerns whether Esotericists genuinely believe their conspiracy theories. Some philosophers have recently argued that many instead merely imagine or pretend (Ichino, 2022; Munro, 2023; Levy, 2022a; Ganapini, 2022). This issue is somewhat orthogonal to my purposes, given that I’m mainly focused on differences in the kind of evidence to which each sort of conspiracy theorist appeals. It’s a further, interesting question exactly what cognitive attitude each forms on the basis of this evidence, whether belief, imagination, or something else (cf. Ichino and Räikkä 2021). I’ll follow the majority of philosophers of conspiracy theory in assuming the relevant attitude is belief.

However, I don’t claim that these two categories exhaust all possible kinds of conspiracy theorists (see fn. 6). I’m also not the first to argue that one can be a conspiracy theorist without subscribing to highly complex, far-fetched narratives—as per fn. 1, the minimal definition of “conspiracy theory” I adopted in this paper all but guarantees that some well-evidenced “official” narratives count as conspiracy theories.

This distinction between types of flat Earthers demonstrates that the class of non-Rowbothian conspiracy theorists is heterogeneous: it includes those who subscribe to specialized methods as in QAnon or Pizzagate, but it also includes those who simply defer to authorities like the Bible.

In describing three examples of Rowbothians, I’ve said that they claim to base their beliefs on firsthand experiences of phenomena like the harmfulness of vaccines. In some cases, these self-descriptions may be a bit misleading—for example, it may not be that one literally has an experience as of a vaccine causing injury, but instead that one sees one’s child get vaccinated, sees one’s child get sick, and then infers from these experiences that the vaccine caused the illness. However, as will become even clearer in later sections, my focus is primarily on Rowbothians’ own self-understanding of their evidence and beliefs. What matters for my purposes is that they conceptualize themselves as trusting firsthand experience, even if the psychological reality is more complex.

This brings out one respect in which Rowbothians depart from Basham’s (2001, p. 277) characterization of conspiracy theorists as questioning how things appear on the surface rather than simply trusting appearances (in a way akin to questioning the nature of the external world rather than accepting what our senses tell us). Instead, Rowbothians claim their starting point is relying on naïve appearances.

This isn’t to say they necessarily draw an inference to a detailed, full story about exactly what the conspiracy and coverup look like. It could be that they’re already aware of such a story from other conspiracy theorists, and that they infer the story must be true. It could be that they infer some kind of coverup must be taking place, after which they engage with other conspiracy theorists to fill out the details of what it looks like.

An archived version of the Gromowski’s website is retrievable from https://web.archive.org/web/20190408134955/http://www.iansvoice.org:80/. Its “Resources” bar includes links to various conspiratorial anti-vax organizations, such as the National Vaccine Information Center and the ThinkTwice Global Vaccine Institute.

A Rowbothian’s belief in a conspiracy thus sounds more like an auxiliary hypothesis to a core hypothesis about a phenomenon like the flat Earth, harmfulness of vaccines, or UFOs (cf. Lakatos 1970). In other words, the belief in such a phenomenon is more central and secure, while the belief in a conspiracy is more likely to be revised in the face of new evidence (e.g., when faced with proof that the establishment hasn’t conspired to cover up the flat Earth, they’ll be more likely to shift to believing the establishment is stupid or deluded than to believing the Earth is round). Following Clarke (2002), it’s at first natural to analyze conspiracy theorizing in terms of conspiratorial core hypotheses rather than auxiliary ones, which would make Rowbothians unlike other conspiracy theorists. However, Poth and Dolega (2023) discuss various examples which suggest beliefs easily recognized as beliefs in conspiracy theories occur as auxiliary hypotheses, too. Paraphrasing, their examples include: core hypothesis “Princess Diana is alive” with auxiliary “the government covered up her death”; and core hypothesis “5G is damaging our health” with auxiliary “the government installed 5G networks with nefarious aims.” Such examples suggest conspiracy theories often come as auxiliary hypotheses even for non-Rowbothians. I take it that what makes someone a conspiracy theorist isn’t believing in a conspiratorial core hypothesis but in a conspiracy theory in general.

At first glance, it’s natural to construe epistemic self-identities in terms of the way one actually forms beliefs, i.e., whether one actually forms beliefs based on scientific evidence, independent thinking, etc. However, this isn’t strictly correct. Although it may be true of many people that they form beliefs via the kinds of methods with which they self-identify, the actual belief forming methods one follows can come apart from how one perceives oneself as forming beliefs (the examples given in the next paragraph make this clear). As per fn. 7, my focus in this paper is primarily on how conspiracy theorists perceive themselves and their own epistemic positions, rather than on how they in fact form their beliefs.

Other philosophers have recently discussed notions that are related to, though slightly distinct from, that which I’m calling epistemic self-identity. For example, Callahan (2021) argues that our values can drive which “epistemic frameworks” we commit to, which then dictates how we form beliefs in response to evidence. Her proposal could be used to complement and flesh out my own in this subsection, as a way of more concretely understanding how our epistemic self-identities translate into particular belief forming practices. Another related notion is what Byrd (2022) calls “epistemic identity.” Byrd’s notion refers to “the phenomenon of treating certain beliefs as part of one’s identity” (57), such as one’s religious or political beliefs. In other words, while my notion of epistemic self-identity is defined in terms of belief forming processes one values, Byrd’s notion of epistemic identity is defined in terms of certain beliefs. Still, the two notions are related: we take certain individual beliefs to result from processes with which we self-identify. Plausibly, such beliefs are among those that constitute what Byrd calls one’s epistemic identity.

Of course, as Mahr and Csibra (2021) note, there are exceptions. Sometimes, one person’s expertise can outweigh another person’s firsthand evidence—you might say you saw a robin in your backyard, but, once you’ve described it to me, my ornithological expertise might result in more authoritative testimony that it was a thrush. Still, it seems like we typically default to treating firsthand testimony as authoritative.

Of course, there are disrespectful ways to correct people about domains on which they aren’t experts—it would be disrespectful for a philosophy professor to correct a student in a condescending way or in a public context where the correction leads to embarrassment. My point is just that, bracketing such considerations about tone and context, the mere act of correcting someone about things that fall well within their territory seems disrespectful, while the same isn’t true of domains about which one isn’t an expert.

In §3.1, I claimed it wouldn’t make much sense to base an epistemic self-identity around being the kind of person who forms beliefs based on perceptual experience, because everyone forms beliefs this way. Note that I’m not contradicting this claim when I describe how Rowbothians form new self-identities. They’re not merely coming to value being the kind of person who forms beliefs on the basis of firsthand experience. Instead, they’re coming to value being the kind of person who forms and remains tenacious in such beliefs despite attempts form the establishment to try to undermine them.

At least, those of us living in open, democratic societies do—his account is meant to apply to such societies.

On the question of Rowbothian rationality, it’s also worth further investigating the details of how different Rowbothian conspiracy theories get fully fleshed out—for example, when it comes to how they describe the exact nature of the conspiracy and coverup. It could turn out that Rowbothian theories are epistemically deficient qua theories—for example, perhaps they resemble “degenerating research programs” (Clarke 2002; Lakatos 1970).

Of course, most people don’t explicitly have the concept “epistemic self-identity,” so these conversations wouldn’t necessarily invoke that label. Still, they could involve discussion of one’s values, the kind of person one sees oneself as being, and the like.

References

Abramson, K. (2014). Turning up the lights on gaslighting. Philosophical Perspectives, 28, 1–30.

Ballantyne, N. (2019). Epistemic trespassing. Mind, 128(510), 367–395.

Barbarossa, C., De Pelsmacker, P., & Moons, I. (2017). Personal values, green self-identity and electric car adoption. Ecological Economics, 140, 190–200.

Barkun, M. (2015). Conspiracy theories as stigmatized knowledge. Diogenes, 62(3–4), 114–120.

Basham, L. (2001). Living with the conspiracy. The Philosophical Forum, 32(3), 266–280.

Beyer, H., & Herrberg, N. (2023). The revelations of Q: Dissemination and resonance of the QAnon conspiracy theory among US Evangelical Christians and the role of the Covid-19 crisis. Zeitschrift für Religion, Gesellschaft und Politik, 7(2), 669–689.

Bristol, R., & Rossano, F. (2020). Epistemic trespassing and disagreement. Journal of Memory and Language, 110, 104067.

Brooks, P. (2023). On the origin of conspiracy theories. Philosophical Studies, 180, 3279–3299.

Buzzell, A., & Rini, R. (2023). Doing your own research and other impossible acts of epistemic superheroism. Philosophical Psychology, 36(5), 906–930.

Byrd, N. (2022). Bounded reflectivism and epistemic identity. Metaphilosophy, 53(1), 53–69.

Callahan, L. F. (2021). Epistemic existentialism. Episteme, 18(4), 539–554.

Cassam, Q. (2016). Vice epistemology. The Monist, 99(2), 159–180.

Cassam, Q. (2019). Conspiracy theories. Polity Press.

Clarke, S. (2002). Conspiracy theories and conspiracy theorizing. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 32(2), 131–150.

Clarke, S. (2023). Is there a new conspiracism? Social Epistemology, 37(1), 127–140.

Davies, H. (2022). The gamification of conspiracy: QAnon as alternate reality game. Acta Ludologica, 5(1), 60–79.

Dentith, M. R. X. (2018). The problem of conspiracism. Argumenta, 3(2), 327–343.

Dentith, M. R. X. (2023). Some conspiracy theories. Social Epistemology, 37(4), 522–534.

Duetz, J. C. M. (2022). Conspiracy theories are not beliefs. Erkenntnis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-022-00620-z

Eccles, J. (2009). Who am i and what am i going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 78–89.

Ganapini, M. B. (2022). Absurd stories, ideologies, and motivated cognition. Philosophical Topics, 50(2), 21–40.

Graziosi, G. (2021). Cult deprogrammers inundated with requests to help people lost in Trump Election, QAnon Conspiracy Theories. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/cult-trump-election-qanon-conspiracy-theories-b1812078.html.

Hagen, K. (2022). Is conspiracy theorizing really epistemically problematic? Episteme, 19(2), 197–219.

Harris, K. (2018). What’s epistemically wrong with conspiracy theorising? Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, 84, 235–257.

Hayes, M. (2022). Search for the unknown: Canada’s UFOs and the rise of conspiracy theory. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Heritage, J. (2012). Epistemics in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 45(1), 1–29.

Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 15–38.

Hoffman, B. L., Felter, E. M., Chu, K.-H., Shensa, A., Hermann, C., Wolynn, T., Williams, D., & Primack, B. A. (2019). It’s not all about autism: The emerging landscape of anti-vaccination sentiment on Facebook. Vaccine, 37(16), 2216–2223.

Ichino, A. (2022). Conspiracy theories as walt-fiction. In P. Engisch & J. Langkau (Eds.), The philosophy of fiction (pp. 240–261). Routledge.

Ichino, A., & Räikkä, J. (2021). Non-doxastic conspiracy theories. Argumenta, 7(1), 247–263.

Ingold, J. (2018). We went to a flat-earth convention and found a lesson about the future of post-truth life. The Colorado Sun. https://coloradosun.com/2018/11/20/flat-earth-convention-denver-post-truth/.

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Dawson, E. C., & Slovic, P. (2017). Motivated numeracy and enlightened self-government. Behavioural Public Policy, 1(1), 54–86.

Kata, A. (2012). Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm—An overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine, 30(25), 3778–3789.

Keeley, B. L. (1999). Of conspiracy theories. The Journal of Philosophy, 96(3), 109–126.

Kelly, D. (2018). The earth is round, and other myths, debunked by the flat eart movement (You Read that Right). Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-colorado-flat-earth-20180115-story.html.

Lakatos, I. (1970). Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes. In I. Lakatos & A. Musgrave (Eds.), Criticism and the growth of knowledge (pp. 91–195). Cambridge University Press.

Lander, D., & Ragusa, A. T. (2020). ‘A rational solution to a different problem’; understanding the verisimilitude of anti-vaccination communication. Communication Research and Practice, 7(1), 89–105.

Landrum, A. R., & Olshansky, A. (2019). 2017 Flat Earth Conference Interviews. OSF.

Levy, N. (2007). Radically socialized knowledge and conspiracy theories. Episteme, 4(2), 181–192.

Levy, N. (2022b). Do your own research! Synthese, 200(365), 1–19.

Levy, N. (2022a). Conspiracy theories as serious play. Philosophical Topics, 50(2), 1–20.

Lewandowsky, S., Lloyd, E. A., & Brophy, S. (2018). When THUNCing Trumps thinking: What distant alternative worlds can tell us about the real world. Argumenta, 3(2), 217–231.

Lorch, M. (2017). Why people believe in conspiracy theories—And how to change their minds. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-people-believe-in-conspiracy-theories-and-how-to-change-their-minds-82514.

Mahr, J., & Csibra, G. (2018). Why do we remember? The communicative function of episodic memory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 19, 1–93.

Mahr, J., & Csibra, G. (2021). The effect of source claims on statement believability and speaker accountability. Memory & Cognition, 49(8), 1505–1525.

McIntosh, J. (2022). The sinister signs of QAnon: Interpretive agency and paranoid truths in alt-right oracles. Anthropology Today, 38(1), 8–12.

Mohammed, S. N. (2019). Conspiracy theories and flat-earth videos on YouTube. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 8(2), 84–102.

Munro, D. (2023). Cults, conspiracies, and fantasies of knowledge. Episteme.

Nagel, J. (2019). Epistemic territory. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 93, 67–86.

Napolitano, M. G. (2021). Conspiracy theories and evidential self-insulation. In S. Bernecker, A. K. Flowerree, & T. Grundmann (Eds.), The epistemology of fake news (pp. 82–106). Oxford University Press.

Nguyen, C. T. (2020). Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Episteme, 17(2), 141–161.

Olshansky, A., Peaslee, R. M., & Landrum, A. R. (2020). Flat-smacked! converting to flat eartherism. Journal of Media and Religion, 19(2), 46–59.

Packer, J., & Stoneman, E. (2021). Where we produce one, we produce all: The platform conspiracism of QAnon. Cultural Politics, 17(3), 255–278.

Pigden, C. (1995). Popper revisited, or what is wrong with conspiracy theories? Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 25(1), 3–34.

Pomerantz, A. (1980). Telling my side: “Limited Access” as a “fishing” device. Sociological Inquiry, 50(3–4), 186–198.

Poth, N., & Dolega, K. (2023). Bayesian belief protection: A study of belief in conspiracy theories. Philosophical Psychology, 36(6), 1182–1207.

Reich, J. A. (2020). Vaccine refusal and pharmaceutical acquiescence: Parental control and ambivalence in managing children’s health. American Sociological Review, 85(1), 106–127.

Rosenblum, N. L., & Muirhead, R. (2019). A lot of people are saying: The new conspiracism and the assault on democracy. Princeton University Press.

Rowbotham, S. (1865). Zetetic astronomy: Earth is not a globe! Simpkin, Marshall, and Co.

Shelby, A., & Ernst, K. (2013). Story and science: How providers and parents can utilize storytelling to combat anti-vaccine misinformation. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1795–1801.

Siddharth, V., & Murphy, H. (2021). Quitting QAnon: Why it is so difficult to abandon a conspiracy theory. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/5715176a-03b3-4ee9-a857-c50298ffe9da.

Silverman, C. (2016). How the bizarre conspiracy theory behind 'Pizzagate' was spread." Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/fever-swamp-election.

Smith, M. S. (2013). “I Thought” initiated turns: Addressing discrepancies in first-hand and second-hand knowledge. Journal of Pragmatics, 57, 318–330.

Smith, N. (2022). A quasi-fideist approach to QAnon. Social Epistemology, 36(3), 360–377.

Smith, S. E., Sivertsen, N., Lines, L., & De Bellis, A. (2022). Decision making in vaccine hesitant parents and pregnant women—An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 4, 100062.

Smith, T. (2021). "Experts in cult deprogramming step in to help believers in conspiracy theories. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/02/972970805/experts-in-cult-deprogramming-step-in-to-help-believers-in-conspiracy-theories.

Spring, M. (2020). How should You Talk to Friends and Relatives Who Believe Conspiracy Theories? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-55350794.

Suinn, R. M., Khoo, G., & Ahuna, C. (1995). The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale: Cross-cultural information. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 23(3), 139–148.

Ten Kate, J., de Koster, W., & van der Waal, J. (2022). Becoming Skeptical Towards Vaccines: How Health Views Shape the Trajectories Following Health-Related Events. Social Science & Medicine, 293, 114668.

Trevors, G. J., Muis, K. R., Pekrun, R., Sinatra, G. M., & Winne, P. H. (2016). Identity and epistemic emotions during knowledge revision: A potential account for the backfire effect. Discourse Processes, 53(5–6), 339–370.

Warzel, C. (2020). How to Talk to Friends and Family Who Share Conspiracy Theories. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/25/opinion/qanon-conspiracy-theories-family.html.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments and discussion, thank you to Leena Abdelrahim, Brian Huss, Reiss Kruger, Jennifer Nagel, Regina Rini, Julia Jael Smith, Seyed Yarandi, audiences at York University and the Canadian Philosophical Association, and two anonymous reviewers for Synthese.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, York University’s Vision: Science to Applications project, and the Canada First Research Excellence Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Munro, D. Conspiracy theories, epistemic self-identity, and epistemic territory. Synthese 203, 113 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04541-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04541-y