Abstract

This paper concerns the semantics of coordinated if-clauses, as in (1)-(2).

It is argued that the meanings of such sentences are explained straightforwardly on theories of conditionals that tie their non- monotonic behaviour to the if-clause itself (e.g. Schlenker 2004, but not theories that tie it to a (covert) modal operator (e.g. Kratzer 1981; 1991). Coordinated if-clauses are revealing of the fine-grained compositional semantics of conditionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper concerns the semantics of coordinated if-clauses, as in (1)-(2).

It is argued that the meanings of such sentences are explained straightforwardly on theories of conditionals that tie their non-monotonic behaviour to the if-clause itself (e.g. Schlenker 2004, but not theories that tie it to a (covert) modal operator (e.g. Kratzer 1981; 1991). Coordinated if-clauses are revealing of the fine-grained compositional semantics of conditionals.

2 Data

As a first pass the conditionals in (1) and (2) appear to be equivalent to their counterparts in (3) and (4).

That is, coordinated if-clauses seem to collapse to a single if-clause containing the coordination of the two antecedent clauses: :

A few further examples:

Given these apparent equivalences the lesson from coordinated if-clauses could be a simple syntactic one. The following hypothesis for example could suffice: a covert expression (L) marks the left edge of a conditional antecedent and plays the semantic role we thought if did. The complementizer itself is semantically vacuous.Footnote 1

However, Khoo (2021) observes that the equivalence fails for or. Conditionals with disjoined if-clauses and their collapsed counterparts with disjunctive antecedents both lead to simplification inferences. (a) and (b) seem to follow from both of the conditionals in (7):

The same holds for the counterfactual pair in (8).

But Khoo argues that simplification inferences are only obligatory for disjoined antecedent conditionals. This is shown by the fact that (9-b) is a contradiction while (9-a) is not. The latter says something true if it’s below freezing.

One simplification, If it is raining, it is snowing is a contradiction, and thus (9-a) should be too if simplification inferences were entailments. (Khoo calls conditionals as in (9) specificational: the consequent specifies which antecedent proposition is true given the antecedent(s).) A parallel contrast and argument obtain for the counterfactual variant, (10):

To Khoo’s observation we add that if -collapse also fails for conjunction. The failure concerns a property of (non-coordinated) if-clauses that has played a central role in theorising, non-monotonicity. An example is the failure of the inference pattern Strengthening of the Antecedent (SA): (11-b) and (12-b) do not follow from (11-a) and (12-a) respectively. Correspondingly, (11-a) and (12-a) are consistent with (11-c) and (12-c).

We will call the variety of antecedent strengthening that fails in the preceding, SAC (“Strengthening of the Antecedent, Conjunctive”):

The invalidity SAC would entail the invalidity of the following principle given if -collapse, their right hand sides being equivalent:

Thus if if -collapse were valid a pattern of judgments parallel to (11) and (12) would be expected for variants with the if-clause “uncollapsed” into a coordination of if-clauses. But his prediction appears to be incorrect. For example, it does not seem possible to follow up (13-a) with (13-c), in the way one can (12-a) with (12-c).

In addition to showing that if -collapse is invalid for and as well as or, these observations might be taken to show that SCA is valid. For, (13-a) and (13-c) are contradictory given SCA. And yet, the direct SCA inference from (13-a) to (13-b) does not seem to go through, as indicated. We argue in the following section that this (paradoxical) pattern, as well as Khoo’s observation about disjunction, is explained by one class of approaches to the compositional semantics of conditionals. But not another.Footnote 2

3 Two loci for non-monotonicity

A prominent approach to explaining the non-monotonic behaviour of conditionals is the appeal to comparative similarity, due to Stalnaker and Lewis. The following is a generalised/compromise version of their proposed truth-conditions, which collapses two much discussed differences, the validity of Conditional Excluded Middle and the Limit Assumption (see e.g. Lewis, 1981):

More formally in (15-a), where the worlds “most like” w are those selected by the function f\(_w\) applied to the antecedent proposition, meeting the conditions in (15-b):

Note: we write [[\(\phi \)]] for \(\lambda w. [\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}]^w\).

In this section we consider monotonicity and coordinated if-clauses, and two implementations of the comparative similarity approach, reflecting the relevant central assumptions of two theories—Schlenker 2004, and Kratzer 1979, 1981 (a.o.). These implementations are shown make different predictions for the data in §2. This will bring out a general point from coordinated if-clauses regarding the compositional semantics of conditionals.

Like Stalnaker and Lewis’s own proposals, (15-a) is stated syncategorematically: the truth-conditions for if p, q are given only/directly in terms p and q. A further question arises within type-driven, compositional approaches to semantics, of how the total truth-condition is divided among (the meanings of) the other syntactic constituents of a conditional. This is a question about syntactic Logical Form and semantic composition. In addition to the antecedent clause and consequent clauses, the syntactic constituents of a conditional include (at least) the if-clause in which the antecedent is embedded, and of course if itself. Semantically, there are two key components of (15-a): quantification and selection (of maximally similar worlds).

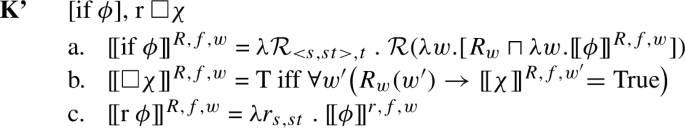

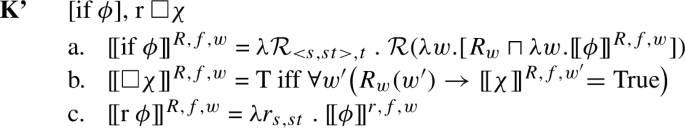

With this in mind consider the following LFs for a conditional \(\textit{if } \phi , \chi \), and corresponding semantic (de)compositions of (15-a), which we will call S and K for reasons discussed below:Footnote 3

(For readability in we suppress relativization of [[\(\cdot \)]] to R and f and talk of sets in lieu of characteristic functions thereof, e.g. referring to [[\(\phi \)]] as the set of \(\phi \)-worlds.)

On S, selection is tied to if, with an if-clause denoting the closest antecedent worlds. In this respect S reflects most directly the theory of Schlenker (2004), who treats if-clauses as referential devices picking out the closest antecedent worlds. Tying selection to if may be implicit already in Stalnaker-Lewis’s way of stating truth-conditions, in spite of being syncategorematic, in which case read ‘S’ as invoking Stalnaker-Lewis instead of/in addition to Schlenker. Quantification comes from a modal operator (\(\Box \)) in the consequent clause, ranging over the (accessible) worlds denoted by the if-clause. (In this second respect it departs from its namesakes, a point we return to in §4.)

On K, both selection and quantification are tied to a modal operator (\(\Box \)) in the consequent clause. The if-clause simply denotes the antecedent worlds and the modal both selects and then quantifies over the most similar (accessible) ones. In this respect K reflects the proposal of Kratzer (1979), Kratzer (1981). We elaborate on K and Kratzer’s theory in §4, but a few notes are in order: (i) the accessibility relation R here plays the role of Kratzerian modal base, f that of ordering source. (ii) similarity is based on an ordering on worlds, as in Lewis/Stalknaker rather than premise sets of propositions, as in Kratzer’s formulation. This accords with the general equivalence proven by Lewis (1981) between ordering and premise semantics (Chemla, 2011, see also).

Though S and K differ regarding the locus of selection in Logical Form and semantic composition they are equivalent, modulo accessibility, for conditionals without coordinated antecedents. More precisely, for a conditional if \(\phi \), \(\chi \) and \(R_w\) such that [[\(\phi \)]] \(\subseteq \) \(R_w\) (e.g. \(R_w\) = the set of worlds W, all worlds accessible), S and K both yield the truth-condition (15-a). While (further) assumptions about accessibility can make the bare formal frameworks S and K diverge, this is immaterial to the main point of this section, which follows.Footnote 4

For conditionals with coordinated if-clauses, the predictions of S and K come apart. On both approaches, it is expected that if-clauses can be combined by and and or, qua generalized Boolean connectives \(\sqcap \) and \(\sqcup \):Footnote 5 However, on K we have selection first then coordination, and on S coordination then selection.

On S, the consequent of a coordinated if-clause conditional must be true in all the worlds in the right column (the intersection/union of the closest \(\phi \)-worlds with the closest \(\psi \)-worlds). On K, the consequent must be true in all worlds in: \(f_w\) applied to the right column (the intersection/union of the proposition \(\phi \) with \(\psi \)). This difference results in the following pattern of (in)validities:

Comparing the theories for disjunction, it is immediate that S but not K captures Khoo’s observation that simplification is obligatory for disjunctions of if-clauses, but not disjunctive ones (§2). Only the former validates the principle SAD, though both invalidate simplification for disjunctive antecedents,

SDA is valid on neither since for simplex antecedent conditionals we have equivalence to Lewis/Stalnaker, on which the principle fails for well-known reasons (Nute, 1975). (That simplification inferences are nonetheless robust/default for disjunctive antecedents, has been argued to have a pragmatic explanation; e.g. Bar-Lev & Fox 2020).

For conjunction, the situation is more subtle. On the one hand K (but not S) validates and-collapse, and thus captures the apparent equivalence between conjoined and conjunctive if-clauses noted at the outset of §2. On the other hand, because of this K fails to fully explain their contrasting antecedent(s) strengthening behaviour noted in §2. K (like S) invalidates strengthening of the antecedent, and the specific case of SAC, by design: (11-b) does not follow from (11-a), and correspondingly, (11-c) is consistent with (11-a), since the closest worlds where the US doesn’t have nukes may be ones where Russia doesn’t. Because it validates and-collapse K does correctly predict that (13-b) does not necessarily follow from (13-a). But for the same reason it incorrectly predicts that (13-c) should be consistent with (13-a), just as (11-c) is with (11-a).

S, we will argue, can make sense of this pattern, with the help of a further observation and assumption. With these in place it can also explain the perceived equivalence between conjoined and conjunctive if-clauses in spite of not validating and-collapse.

First we note that, given the truth of (13-a), (13-c) can only be true vacuously on S – in contrast to its conjunctive antecedent counterpart (12-c). For it follows from (13-a) that if there are any worlds in [[if the US didn’t have nukes and if Russia didn’t have nukes]]\(^w\) they are worlds in which Russia does invade. It seems plausible to assume a pragmatic constraint against asserting a sentence that could only be vacuously true. It would then follow that (13-c) can never be truly asserted along with (13-a). Such a constraint could for example be realised by a presupposition on \(\Box \) that its domain of quantification be non-empty:

This presupposition makes (13-c) undefined whenever (13-a) is true.Footnote 6 In turn, the strengthening (SCA) inference from (13-a) to (13-b) can fail on pragmatic grounds. While the truth of (13-a) guarantees that any worlds in [[if the US didn’t have nukes and if Russia didn’t have nukes]]\(^w\) are Russia-invades-worlds, it does not guarantee that there are any such worlds. Thus, it does doesn’t guarantee that (13-b) is non-vacuously true and therefore assertible. Given (16), SCA becomes (merely) Strawson valid; the premise (merely) Strawson entails the conclusion (cf. (17) below). We now have an explanation for the puzzle from the end of §2: while SCA is not (fully) valid, still (13-c) can never be asserted along with (13-a). (We return below to when SCA inferences are predicted to go through.)

With this in hand we return to and-collapse. With the pragmatic assumption encoded

In (16), and-collapse fails in case [[if \(\phi \) and if \(\psi \)]]\(^w\) is empty. In that case \(\Box \) has an empty domain and [[[if \(\phi \) and if \(\psi \)], \(\Box \chi \)]] is the tautology, while [[[if \(\phi \) and \(\psi \)], \(\Box \chi \)]] may be false. On the other hand, where [[if \(\phi \) and if \(\psi \)]]\(^w = f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) \cap f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}])\) is not empty, and-collapse does go through. For then,

-

1.

there is a \((\phi \text { and }\psi )\)-world, u in \(f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}])\) and in \(f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}])\)

-

2.

by 1, \(u \le _w v\) for every \(\phi \)-world, and thus every \((\phi \text { and }\psi )\)-world, v.

-

3.

by 2 \(f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi \text { and }\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) \subseteq f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}])\) and \(f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi \text { and }\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) \subseteq f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}])\)

and so \(f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) \cap f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) = f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi \text { and }\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}])\).Footnote 7

It should be apparent that with our non-vacuity assumption (16) in place, and-collapse like SCA is (merely) Strawson valid. The left to right direction is valid, but the right to left is (merely) Strawson valid: whenever If p and if q, r is true, If p and q, r is true and whenever the latter is true and the former defined, the former is true. Thus whenever an utterance of one is felicitously asserted/accepted, the other must be, accounting for the intuition of equivalence noted in §1. Perceived equivalence is predicted to break only in case [[if p and if q]]\(^w\) is empty, a presupposition failure. For example, a contrast is expected between (a) and (b) as continuations of (18):

for (a) will be undefined and therefore not assertible given the truth of (18).

Finally, let us reconsider SCA in light of the Strawson validity of and-collapse. A final prediction is that an instance of SCA should go through—the conclusion should be assertible and true in light of the premise, only if the corresponding instance of SAC goes through. This seems correct. For example, in a situation in which someone does conclude (13-b) from (13-a), it seems clear they must accept (12-b).

4 Discussion

In the above we argued that the behaviour of coordinated if-clauses favours S over K. The crucial difference between the two frameworks which lead to differing predictions is the scope of selection vs. coordination. The takeway, which extends beyond these specific implementations of the comparative similarity approach, is that selection in conditionals should scope below or “precede” coordination in coordinated if-clauses (which in turn scopes below quantification).Footnote 8 While S and K depart in some ways from the proposals of Schlenker (2004) and Kratzer (1981), respectively, they are true to them with respect to the the locus for selection. For both Kratzer and Schlenker the locus of selection is a design feature that ties into further features and explanatory aims of their analyses. We conclude by discussing the implications of this squib in light of their specific proposals.

For Kratzer, the non-monotonic behavior of conditionals is the realisation of a more general semantic feature of modals. Modals as a class do not simply quantify over accessible worlds, but have an additional parameter that selects a “best” subset of these worlds. In terms of our rendering K, all modals come with a (context dependent) R and f, varying by type of modality. In conditionals, quantification comes from a modal in the consequent. This may be an overtly expressed one where present, or a covert one. For example, modal quantification in a would-counterfactual comes from would directly, which would correspond to \(\Box \) in our rendering K. Thus conditionals are normal, albeit doubly relative, modal statements. They also come with a modifier: the if-clause, which functions to restrict the accessible worlds from which the modal selects its domain of quantification.

On K the modal in consequent takes the if-clause as argument, restricting the modal base/accessible worlds, R. (In the spirit of Kratzer one could assume that a modal takes an implicit argument, in non-conditional modal statements). This is commensurate with how Kratzer’s theory is sometimes presented/implemented in the literature. In Kratzer’s original formulation, however, the if-clause is treated as the higher type expression, an operator that shifts the modal base (accessible worlds), restricting it to antecedent worlds. While there are likely other reasons to prefer this implementation, it does not yield the desired results for coordinated if-clauses, since coordination scopes over quantification (the result is a wide scope coordination of conditionals).Footnote 9

Kratzer motivated her theory from puzzles about deontic modals, graded uses of (nominalised) modals, and—most directly—the fact that if-clauses do appear to restrict overt modals in some cases. To put the latter more neutrally, Kratzer noted that extant theories of conditionals could not capture the meaning of certain conditionals with overt modals in their consequents. Recent work has questioned some of these motivations—e.g. Lassiter (2011) on graded uses, Mandelkern (2023) on if-clauses as restrictors, pointing to different explanations. Since the conclusions of this squib are at odds with the core assumptions of Kratzer’s view they can be taken to support alternative perspectives on her motivating data.

Schlenker’s theory, by contrast, localises selection to if-clauses, in aiming to capture observed parallels between if-clauses and definite descriptions. For example, following Lewis, Schlenker observes that definite descriptions exhibit similar failures of monotonicity (e.g. The dog(s) is (are) barking does not entail The neighbors dog(s) is (are) barking). if-clauses are assimilated to definite descriptions of worlds, and selection in a generalised sense (‘most accessible’) is taken to apply to the restrictor of definites. Thus in a conditional if p, q, if p denotes the most accessible p-world(s), analogously to ‘the dog(s)’, which denotes the most accessible dog(s).

In Schlenker’s official formal system, unlike our S, there is not a separate device (\(\Box \)) for quantification in conditionals. This is because if-clauses are formalised as singular definites: a là Stalnaker, selection gives a unique closest antecedent world. Compositionally the if-clause is in effect a direct argument of the proposition expressed by the consequent: if p, q is true at w iff [[q]]\((F_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\text {p}}]\hspace{-.02in}]))=1\), \(F_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\text {p}}]\hspace{-.02in}])\) being the p-world most like w (\(F_w\) a Stalnakerian selection function). However, in Schlenker’s informal discussion systems with plural reference to worlds are also discussed.

Considerations from coordinated if-clauses favor a system (like S) with “plural reference”, i.e. not imposing uniqueness on f. With uniqueness, if p and if q, r would entail that if p, r which is clearly incorrect empirically. S can be brought closer to Schlenker, as follows

In S’, if-clauses denote sets (pluralities) of worlds and consequents denote distributive properties of such pluralities, analogous to (inherently distributive) predicates of individuals. The latter is implemented via a syntactic operator dist but there are other options that go beyond the scope of this squib. Conditional Excluded Middle, which is validated by uniqueness in Schlenker’s system, can be retained via a homogeneity presupposition on dist (von Fintel, 1997),(Kriz̆ 2015; 2019). Similarly CEM can be added to S itself via a homogeneity presupposition on \(\Box \).Footnote 10

In conclusion, while many issues remain open, we hope that this short paper has contributed data and considerations that bear on the fine-grained compositional semantics of conditionals. Such details may be significant not only for understanding the linguistic system but for broader debates in logical and philosophy.

Notes

Given the LF [L [if p and/or if q]], and that [[if p]]=[[p]], it would follow that [[L [if p and/or if q]]] = [[L [if p and/or q]]].

Khoo (2021) proposes there are “secondary”, or less accessible, readings of (ostensibly) coordinated if-clause conditionals, on which they are equivalent to coordinations of conditionals.

-

(i)

If it was snowing or if it was raining, John would stay in (I don’t remember which).= If it was snowing, John would stay in or if it was raining, John would stay in.

-

(ii)

If it is snowing and if it is not snowing, John stays in.= If it is snowing John stays in and if it is not snowing John stays in.(obv. \(\ne \) If it is snowing and not snowing, John stays)

These readings could be explained in various possible ways—e.g. ellipsis, type shifting, ATB movement, under either approach to the semantics of conditionals considered in the following section. We therefore do not discuss them further.

-

(i)

We leave to the reader to generalise from [[if \(\phi \)]]\(^w\) as defined to [[if]]\(^w\).

For example, On Kratzer’s theory, counterfactual conditionals are distinguished from indicatives in terms of accessibility—total for the former (\(R_w = W\)) not not the latter.

-

(i)

$$\begin{aligned}{} & {} [\hspace{-.02in}[{A \,\,\textrm{and}\,\, B}]\hspace{-.02in}]^w = [\hspace{-.02in}[{A}]\hspace{-.02in}]^w \sqcap [\hspace{-.02in}[{B}]\hspace{-.02in}]^w, \textrm{where} \alpha \sqcap \beta =\\{} & {} \qquad \alpha \wedge \beta \ \ \ \textrm{if}\,\, \alpha , \beta \,\, \textrm{of}\,\, \textrm{type}\,\, \textrm{t},\\{} & {} \qquad \lambda x .[ \alpha (x) \sqcap \beta (x)] \ \ \ \textrm{if} \alpha , \beta \textrm{are}\,\, \textrm{of} \,\, \textrm{type} \langle a,b \rangle , \,\,\textrm{and}\,\, \textrm{b} \,\, \textrm{ends} \,\, \textrm{in} \,\, \textrm{t} \end{aligned}$$

-

(ii)

$$\begin{aligned}{} & {} [\hspace{-.02in}[{A\,\, or \,\, B}]\hspace{-.02in}]^w = [\hspace{-.02in}[{A}]\hspace{-.02in}]^w \sqcup [\hspace{-.02in}[{B}]\hspace{-.02in}]^w,\,\, \textrm{where}\,\, \alpha \sqcup \beta =\\{} & {} \qquad \alpha \vee \beta \ \ \ \textrm{if}\,\, \alpha , \beta \textrm{of}\,\, \textrm{type}\,\, t,\\{} & {} \qquad \lambda x .[ \alpha (x) \sqcup \beta (x)] \ \ \ \textrm{if}\,\, \alpha , \beta \,\, \textrm{are}\,\, \textrm{of}\,\, \textrm{type}\,\, \langle a,b \rangle , \textrm{and}\,\, b \textrm{ends}\,\, \textrm{in}\,\, t \end{aligned}$$

-

(i)

\(\lambda \alpha _{a} : P\ . \ \beta _{b} \) is a partial function defined only for \(\alpha \) of type a such that P.

1. follows from the def. of \(f_w\) (Centering), 2. from 1. and the def. of \(\le _w\) ((15-b)), and 3. from 2. and the def. of \(f_w\). While 2. makes use of \(\le _w\) being total, this is not essential. The same result could be obtained with a selection function based on ordering that is not total, as long as the selection function is “downward persistent”: where \(\phi \) entails \(\psi \), the most similar \(\phi \)-worlds are just those \(\phi \)-worlds, if there are any, that are among the most similar \(\psi \)-worlds:

-

(i)

\([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}] \subseteq [\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}] \Rightarrow f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) = [\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}] \cap f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) \qquad \) if \(f_w([\hspace{-.02in}[{\psi }]\hspace{-.02in}]) \cap [\hspace{-.02in}[{\phi }]\hspace{-.02in}] \ne \emptyset \)

-

(i)

The first proposal to discuss and treat coordinated if-clauses specifically is Khoo (2021). It is is implemented with a strict semantics which validates and-collapse, and SAD, by way of several innovations. Khoo uses a covert modal that is strict but proposes (fn.13) that a Kratzerian one (cf. K) could be adopted instead to handle non-monotonicity in general. As far as we can tell, with this move and-collapse would still be valid. We do not discuss his proposal in detail for reasons of space, and since our aim is to make a broad point about comparative similarity approaches.

Here is an implementation, by modification of K. Abstraction is needed over the R parameter (now explicit), which we introduce in the syntax with an abstractor r.

If p and if q, r for example will be equivalent to if p, r and if q, r, given type flexible and. This is not the reading we need to derive (see fns. 2 and 5).

Without a homogeneity presupposition added to \(\Box \)/dist the following two sentences are predicted to be consistent:

-

(i)

-

a.

If the US has nukes and if Russia has nukes, there will be war.

-

b.

It’s not the case that if the US has nukes, there will be war.

-

a.

This may seem incorrect and thus a reason to adopt homogeneity since it ensures that the conditional negated in the second sentence cannot be defined when the first is true. Thus it seems S/S’ may need homogeneity, independently of more general considerations for CEM. On the other hand, as a reviewer points out, homogeneity may not be an adequate solution in general for considerations about CEM. Homogeneity would seem to fail for cases such as ‘If I flip this coin it will land heads’, making them undefined. The latter result may be counterintuitive and also leave us without an account of the truth of beliefs about the probabilities of such statements (50%). I leave such issues for future research.

-

(i)

References

Bar-Lev, M., & Fox, D. (2020). Free choice, simplification, and innocent exclusion. Natural Language Semantics, 28(3), 175–223.

Chemla, E. (2011). Expressible semantics for expressible counterfactuals. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 4(1), 63–80.

Khoo, J. (2021). Coordinating Ifs. Journal of Semantics, 38(2), 341–361.

Kratzer, A. (1979). Conditional necessity and possibility. In R. Bäuerle, U. Egli, & A. von Stechow (Eds.), Semantics from different points of view (pp. 117–147). Springer.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H. J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts (pp. 38–74). de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality/conditionals. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantik: Ein Internationales Handbuch der Zeitgenösischen Forschung (pp. 639–650). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Kriz̆, M. (2015). Asepcts of homogeneity in the semantics of natural language. Ph.D. thesis, University of Vienna.

Kriz̆, M. (2019). Homogeneity effects in natural language semantics homogeneity effects in natural language semantics homegeneity effects in natural language semantics. Language and Linguistics Compass, 13(11), e12350.

Lassiter, D. (2011). Measurement and Modality: The Scalar Basis of Modal Semantics. Ph.D. thesis, NYU.

Lewis, D. (1981). Ordering semantics and premise semantics for counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 10(2), 217–234.

Mandelkern, M. (2023). Bounds: Meaning and the limits of interpretation. OUP.

Nute, D. (1975). Counterfactuals and the similarity of worlds. Journal of Philosophy, 72, 773–778.

Schlenker, P. (2004). Conditionals as definite descriptions (a referential analysis). Research on Language and Computation, 2(3), 417–462.

von Fintel, K. (1997). Bare plurals, bare conditionals and ‘only’. Journal of Semantics, 14(1), 1–56.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Matt Mandelkern, Justin Khoo and Cian Dorr, as well two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with ethical standards

The research reported in this paper did not involve animal or human subjects. There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics Compliance

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klinedinst, N. Coordinated ifs and theories of conditionals. Synthese 203, 70 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04458-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04458-y