Abstract

It is usually agreed that reality is temporal in the sense of containing entities that exist in time, but some philosophers, roughly those who have been traditionally called A-theorists, hold that reality is temporal in a far more profound sense than what is implied by the mere existence of such entities. This hypothesis of deep temporality typically involves two ideas: that reality is temporally compartmentalised into distinct present, past, and future ‘realms’, and that this compartmentalisation is temporally dynamic in the sense that the boundaries of those temporal realms change from one moment to the next. The truth of something like this hypothesis is commonly thought to require that at least some of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality be tensed. While this seems plausible, realism about fundamental tensed facts does not seem to entail deep temporality. Nor is it clear exactly what realism about tense amounts to, given that no informative answer has been given to the question of what it is for a fact to be tensed. In this paper, I introduce a novel approach, perspectivalism about temporal reality, that seeks to vindicate the hypothesis of deep temporality by ascribing to reality a certain kind of temporally perspectival structure, which also provides a straightforward answer to the question of what the tensedness of facts consists in as well as to the question of what it is for reality to be constituted by such facts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Prologue

Temporal reality is the portion of reality that involves temporal entities—entities that, in some general sense, exist in time, have some temporal location. That reality, at least in part, is temporal in this particular sense is uncontroversial, given that it is perfectly compatible with the idea that reality has a thoroughly atemporal character. When describing reality in fundamental terms, philosophers committed to this latter claim naturally adopt a tenseless mode of predication that is free from any temporal qualification; they contend that all of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality are ones that make up the way things simply are, Footnote 1 without any temporal qualification whatsoever. In other words, these philosophers endorse the following thesis:

atemporalism

All of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality are ‘visible’ from the atemporal perspective; they all constitute the way reality atemporally is.

Proponents of atemporalism think that, at best, reality is temporal merely in virtue of containing time and entities that are located at certain regions of time. But all the facts involving these temporal entities and times themselves, including facts about the location relations holding between them, are ‘visible’ from the atemporal perspective. Although times and temporal entities may figure as the components of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality, there is nothing temporal about the manner in which those facts obtain.

This atemporalist attitude is traditionally associated with the B-theory of time; the opposing A-theory of time is supposed to reject, in one way or another, atemporalism, along with the rather ‘thin’ notion of temporality that emerges from it. For, according to that notion, reality is temporal in roughly the same sense in which it is spatial: while certain entities exist in space and have spatial locations, there is nothing spatial about the manner in which the facts involving these spatial entities obtain and constitute reality. But most, if not all, A-theorists think that the temporality of reality runs deeper. This A-theoretic attitude typically involves the following two theses:

temporal compartmentalisation (tc)

Reality is, in some metaphysically non-trivial sense, temporally compartmentalised; it genuinely divides into distinct past, present, and future ‘zones’.

temporal dynamicity (td)

The boundaries of reality’s temporal ‘zones’ are not fixed, but rather subject to constant change.

The picture that results from the combination of tc and td is clearly one where reality is temporal in a far deeper sense than the sense in which it is spatial: unlike space, time is not just a platform where entities are located at, not just an arena where they show up and instantiate certain properties. Rather, reality itself exhibits an essentially temporal structure that also undergoes change from this moment to the next. Hence, a world that is both temporally compartmentalised and temporally dynamic would be a world that is, as one may put it, deeply temporal. Call the thesis that reality is indeed deeply temporal d-temporalism.

Fine (2005b, 2006) has recently proposed to construe the A/B-debate in terms of the question of whether at least some of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality are tensed or not—accordingly, A-theorists are supposed to be realists and B-theorists anti-realists about tensed facts. But even if we suppose that anti-realism entails, and is entailed by, atemporalism, it is highly doubtful that d-temporalism simply falls out from realism. Indeed, as Fine (2005b, §7) himself has famously argued, some (in fact, the most widespread) versions of realism seem to have serious difficulties with accommodating td.Footnote 2 Given this, the two dialectical axes, realism vs. anti-realism about tense and d-temporalism vs. atemporalism, do not seem to even be extensionally equivalent.

My central aim in this paper is to describe, in some detail, a novel anti-atemporalist approach: perspectivalism.Footnote 3 Perspectivalism is primarily motivated by the task of upholding d-temporalism, and while the perspectivalist does profess to be a realist about tense, she does not simply help herself to realism, as it were. Rather, she first proceeds to spell out an anti-atemporalist view of reality’s constitution by facts, and then seeks to understand reality’s fundamental tensedness in terms of that view. The result is, as I argue below, a version of realism about tense that both does proper justice to d-temporalism and has something informative to say about what it is for a fact to be tensed and what it is for reality to be fundamentally constituted by such facts.

I should stress that the paper is largely exploratory in spirit; by itself, it does not quite amount to a proper defence of perspectivalism. I have argued elsewhere that standard, non-perspectivalist conceptions of realism about tense face severe difficulties, and it is a clear advantage of the perspectivalist approach that it is unaffected by those problems.Footnote 4 But here I make no serious attempt to compare perspectivalism with its various rivals; nor do I discuss any possible objections to the foundations of the view. My goal is rather the more modest one of getting clear about what those foundations are and what sort of metaphysical edifice they support.

2 Perspectivalism introduced

The guiding idea of perspectivalism, formulated most broadly, is that making sense of temporal reality requires the notion of temporal perspective besides the notion of temporal location—when we describe how temporal reality fundamentally is, we need to qualify (at least some of) what we say by appealing not only to temporal locations but also to temporal perspectives. Thus, any version of perspectivalism will subscribe to the following thesis:

proto-perspectivalism (pp)

Temporal reality is fundamentally temporally perspectival—the way temporal reality fundamentally is involves not only temporal locations but also temporal perspectives.

What is of primary interest in what follows is an anti-atemporalist approach that utilises the notion of temporal perspective to illuminate d-temporalism and the tensedness of some of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality. But it is important to recognise that pp itself is independent of this kind of project—in fact, pp is entirely compatible with atemporalism.

Different theories that endorse pp or something similar will understand the notion of a temporal perspective in different ways. Let us first distinguish between two ways in which temporal perspectivality may be associated with facts: the irreducible perspectival element may either be a matter of what is the case or rather how whatever is the case is the case—it can either belong to the content of the relevant facts or be a characteristic of their form. In the former case, the perspectivality involved is componential—the perspectival element is a component of the relevant facts. In the latter case, the perspectivality is constitutional—it has to do with the manner in which the relevant facts obtain and constitute reality.Footnote 5 Call facts with perspectival content, independently of the manner in which they obtain, perspectival facts (or p-facts, for short), and facts featuring a perspectival form, independently of their content, perspectivally obtaining facts (or po-facts, for short). While a fact may be both a p-fact and a po-fact, there may also be p-facts that are not po-facts as well as po-facts that are not p-facts.

We can make the above distinction more perspicuous in how we refer to facts by keeping the mode of obtaining of a fact separate from its content—we can, for instance, signal the atemporal mode of obtaining in terms of a subscripted “a”, as in ⌈[φ]a⌉. Next, let us introduce a perspective operator, designated by ⌈Πt⌉ and read as ⌈From the perspective of t⌉. Now, an atemporalist may very well claim that all the facts that fundamentally constitute reality are p-facts, which, however, are not po-facts—that is, facts denotable by an expression of the following type: ⌈[Πt(φ)]a⌉. This atemporal perspectivalist (a-perspectivalist, for short) agrees with the standard B-theorist that there is nothing temporal about the way in which reality is constituted by facts, that there is an atemporal perspective from which all the facts that fundamentally constitute reality are ‘visible’. But while on the standard B-theory, once one occupies the atemporal perspective, one is supposed to be able to ‘see’ all the various different ways the things located in time are at their respective locations, the a-perspectivalist thinks that what is seen from the atemporal perspective is not how temporal things simply are, but rather how, from some particular temporal perspective, they are. Although all of the temporal perspectives are accessible from the atemporal standpoint, none of them is transparent: from the atemporal perspective, one cannot simply ‘look’ through a temporal perspective and ‘see’ how things are. On a-perspectivalism, therefore, there is no saying how temporal reality is without first specifying a temporal perspective from which it is supposed to be that way.Footnote 6

Whatever merits a-perspectivalism may have, vindicating d-temporalism is not one of them. It is part and parcel of the hypothesis of deep temporality that the dynamic compartmental structure it ascribes to reality belongs to its fundamental nature. More precisely, the hypothesis will not be vindicated if what it is for reality to be temporally compartmentalised and temporally dynamic turns out to be an atemporal matter of certain things’ being a certain way:

the fundamentality constraint (fc)

If reality genuinely is deeply temporal, then its being deeply temporal cannot be grounded in atemporally obtaining facts.

The rationale for fc is that, if one attempts to explain temporal compartmentalisation and temporal dynamicity in terms of how certain things atemporally are, one would in effect be postulating an atemporal layer of reality that is more fundamental, and therefore ‘deeper’, than what one seeks to explain.Footnote 7

Given fc, accepting atemporalism precludes one from taking deep temporality seriously: for, at the fundamental level, the only facts that are available to the atemporalist are facts that obtain and constitute reality in an atemporal, tenseless manner. And since pp is compatible with atemporalism, one needs to go beyond pp and componential perspectivalism in order to vindicate the hypothesis of deep temporality. Thus, if a perspectivalist approach is to uphold d-temporalism, it will need to take perspectivality as a constitutional matter, by endorsing something along the following lines:

constitutional perspectivalism (cp)

Some of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality do so in a temporally perspectival manner; they obtain and constitute reality as of, or from the perspective of, some time.

In constitutional perspectivalism (c-perspectivalism, for short), times lead somewhat of a double life: there are two fundamentally distinct roles associated with them. The first is the familiar locational role that consists in temporal regions’ being occupied by certain entities. Perspectivalists hold that times also serve a further, distinctively perspectival function: they act as unique ‘gateways’ into some of the fundamental ways things are, in the sense that the very obtaining of the facts constituting those ways occurs only relative to them, without this being explainable in terms of some other facts’ atemporal obtaining. We can signal the temporal mode of obtaining of these facts by subscripting the name of the time as of which the relevant fact is supposed to obtain—that is, by means of ⌈[φ]tn⌉.

Given this symbolism, the disagreement between the a-perspectivalist and the c-perspectivalist can be put as follows. Imagine a very simple universe in which the entire temporal reality consists of one persisting temporal entity, Fido, and his three colour-states—a universe that the B-theorist would take to be exhaustively constituted by these three facts: that Fido is yellow at t1, that he is brown at t2, and that he is blue at t3.Footnote 8 Now, while both the a-perspectivalist and the c-perspectivalist, unlike the B-theorist, conceive of Fido’s yellowness, say, as a temporally perspectival matter, the former takes it to reside in the p-fact [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]a and the latter in the po-fact [Yellow(Fido)]t1. While c-perspectivalism is certainly compatible with p-facts, it denies that it is the existence of such facts that makes reality fundamentally temporally perspectival. Rather, what is required to be perspectival is the form, the mode of obtaining, of the facts, in order for reality to be genuinely, irreducibly perspectival. According to the c-perspectivalist, p-facts are not necessary for reality’s temporal perspectivality, given that some po-facts are not p-facts, as illustrated by [Yellow(Fido)]t1. Nor are p-facts sufficient for genuine perspectivality, given that a p-fact may fail to be a po-fact, as [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]a demonstrates.

In what follows, we will explore some of the central aspects of perspectivalism and address various ‘choice points’ that perspectivalists face when developing cp into a metaphysics of temporal reality. As cp can be approached from various different angles and elaborated in different ways, the discussion below will inevitably involve commitments that a perspectivalist, qua perspectivalist, need not agree with. One has to take a stance on such issues in order to make the view more tangible, but it is worth keeping in mind that the core of the theory is at least partly independent of this particular presentation of it.

3 The composition of reality

The atemporal and the perspectival modes of obtaining are primitives of perspectivalism—they are the unexplained elements of the theory in terms of which some other notions are explained. Nevertheless, given how central they are to the perspectivalist project, it seems a good idea to try to elucidate them to some extent.

We might attain a better grasp of these notions by putting them into the context of some very general questions concerning the compositional nature of reality. On a somewhat vague, yet fairly widespread conception, reality is the totality of facts, the totality of what is the case.Footnote 9 To be sure, even among those who are in general sympathetic to this idea, there will be considerable disagreement as to how exactly it is to be understood, how seriously it is to be taken. Let us take it quite seriously and interpret “totality” mereologically—that is, let us conceive of reality as the ultimate, maximal whole that has all the facts there are as part. Let us also suppose, as is plausible, that facts themselves are mereologically complex as well: they are composed of individual objects and predicables, that is, properties and/or relations. On this picture, then, objects and predicables are the basic building blocks of the world: they compose the wholes that are the facts, which, in turn, compose the whole that is reality.

Another well-known general thought about the nature of reality is worth a mention here: that reality is not, as Sider (2009, p. 398) puts it, “just a structureless blob”, but rather has a certain objective form. Combine this with the above picture of reality as a whole composed by facts and what you seem to get is the idea that reality is a structured whole rather than a mere sum or aggregate of facts. For if the idea of reality’s having an objective structure or form is to be taken seriously, then the natural environment for the inquiry into the composition of reality by facts will be provided by a broadly hylomorphic approach to composition.Footnote 10 Let us therefore suppose, following Johnston (2006, p. 653), that any item that is a structural composite involves a principle of unity, “a relation holding of some other items, such that […] what it is for the given item to be is for the relation to hold among those items.”Footnote 11 In the case of facts, the principle of unity will be instantiation: what it is for any given fact [F(a)] to exist is for a to instantiate F. Reality, then, is the composite thing that comprises all of the facts that exist, unified by some relation of whatever complexity.

Given this sort of picture, atemporalists will say that any given instance of the question of whether some object and some property compose a fact or not can be answered once and for all, without any temporal qualification whatsoever—any such question has a definitive, atemporal answer. To be sure, times may well be, in one way or another, constituents of such facts, along with temporal objects and predicables. But there is nothing temporal going on in the way these constituents come together to form a fact and hence in the obtaining of the fact that they form. Consequently, for the atemporalist, reality is the maximal, atemporally existing whole composed by these atemporally available facts, which atemporally hang together by means of some relation between them. The atemporalist can, of course, construe that relation as complex as she likes in various respects. But however rich reality’s form or structure may turn out to be, the atemporalist will insist that it is not temporal in any sense at all. For the atemporalist, time and temporality belong only to the content of reality, not to its form or structure.

Perspectivalists, by contrast, believe that, at least in some cases, the question of whether or not a given object and a given property compose a fact does not have a temporally unqualified answer: it is only from within the perspective of some time that the object and the property either succeed in or fail at forming the complex item that would be the relevant fact. The answer to the question of whether, for instance, Fido and the property of being yellow are tied together by means of instantiation is not available from the atemporal perspective; the answer becomes ‘visible’ once a temporal perspective is adopted: as of t1, those two items do compose a fact, while as of t2, they do not. Note that, on this picture, both the atemporalist’s putative fact that Fido is yellow at t1 and the perspectivalist’s putative fact that, from the perspective of t1, Fido is yellow, if obtained, would share some ‘material’ constituents: they would each have Fido and yellowness as parts.Footnote 12 But the manner in which these items compose a fact is different in each case: composition occurs atemporally in one case and from within a temporal perspective in the other.

The crucial point here is that the sensitivity to temporal perspectives featured by the perspectivalist’s po-facts is not of a kind that can ultimately be reconciled with atemporalism. More precisely, the temporal perspectivality involved in whether or not Fido and the property of being yellow compose a fact is not to be explained, for example, in terms of a temporally qualified relation, instantiation-as-of rather than instantiation, which one might suppose to atemporally serve as the principle of unity. It is still true that different principles of unity must be associated with atemporal facts on the one hand and perspectivally obtaining ones on the other, given that they are supposed to differ in form. But the perspectivalist will insist that that difference does not reduce to one of the relevant relations having an extra slot for times and the other lacking it.

4 Pluralism about constitution

One previously unmentioned feature of atemporalism is that it entails what we can call monism about constitution: the idea that, at the fundamental level, there is only one single manner in which facts constitute reality, one single mode of obtaining for facts that constitute reality. Perspectivalists may very well agree that, fundamentally speaking, there is indeed a single notion of constitution, while disagreeing with atemporalists about what that notion is—they may insist that the single fundamental notion of constitution is a temporally perspectival or relative one. Thus, they may maintain that there is no such thing as atemporal constitution or obtaining, that no fact whatsoever is ‘visible’ from the atemporal perspective. But rejecting the atemporal perspective upon reality across the board is not the only option available to perspectivalists: they can instead reject monism itself in favour of pluralism about constitution. These pluralist perspectivalists may hold that there are two basic notions of constitution: an atemporal one and a perspectival, temporally relative one. On this view, different facts will obtain in different modes and constitute reality in different fashions. While there really is an atemporal perspective upon reality, it is not ultimate and omniferous: not all, but only some of the facts that fundamentally constitute reality are ‘visible’ from it.Footnote 13

Pluralist perspectivalism is certainly more conciliatory than its monist version; however, it also seems more chaotic. For on such an account, the way things fundamentally are incorporates facts of radically different kinds with distinct modes of obtaining. Some of these facts obtain atemporally, while others are ‘visible’ only from a certain temporal perspective. But which ones are which? And why do some facts belong to the atemporal realm while others have a perspectival nature? The more ecumenical pluralist construal of perspectivalism that seeks to accommodate the atemporal perspective as well as temporal perspectives would appear somewhat of a non-starter, if it cannot provide principled answers to these questions.

In response to this challenge, I will sketch out here what I take to be a prima facie plausible and relatively straightforward elaboration of pluralism about constitution, component-driven pluralism (cd-pluralism, for short). The core idea behind cd-pluralism is that the mode of obtaining of a fact depends on the nature of its components. The following rough outline falls well short of a complete or particularly robust defence of the view, but it will hopefully clarify its main tenets.

Let us start with a fairly intuitive distinction among different kinds of objects on the basis of how they relate to temporal locations. As mentioned above, it is not particularly controversial that some objects are temporal in the sense that they exist in time: their existence is (partly) a matter of there being some temporal region that they occupy. But abstract objects, for instance, are not supposed to be temporal in this sense—rather, they are atemporal objects whose existence is completely independent of time and temporal locations.Footnote 14 Further, there is a third, intermediary category of non-temporal objects. Unlike temporal objects, the existence of these objects does not depend on their having a temporal location. But unlike atemporal objects, nor is their existence completely divorced from the locational paradigm either. The non-temporal objects in question are instants of time, which do not have, but rather simply are the temporal locations that temporal things occupy.Footnote 15

This tripartite distinction between temporal, atemporal and non-temporal objects is also available to the atemporalist; but for her, the distinction is of no further metaphysical import: fundamentally speaking, any object belonging to any of these categories simply exists and is a certain way. Given a constitutionally pluralist version of perspectivalism, however, it seems natural that the mode of obtaining of a given fact should partly be informed by what temporal-locational kinds of objects it comprises. This will constitute one way in which the two distinct roles that times play in such a metaphysics are linked.

Indeed, the cd-pluralist will argue, for instance, that the atemporal mode of obtaining perfectly fits the portion of reality made up by atemporal objects. The existence of an atemporal object such as number 2, say, is not tied to anything temporal; the fact that the number 2 exists is an atemporally obtaining fact. And given the number 2’s atemporal existence, it seems that the facts comprising this atemporal object and its fundamental properties must have the atemporal mode as well: for how could the way this object fundamentally is be “subject to the vicissitudes of time”, as Fine (2005a, p. 341) puts it, given that it does not even exist in time? Any temporal qualification, any temporal dependency in such facts would seem out of place, as the object enjoys a type of existence that transcends all temporality. Thus, the number 2’s primality, for instance, is not a temporal matter in any sense whatsoever—the number 2 simply is a prime.

As far as atemporal objects are concerned, then, reality could have well been completely timeless—facts involving such objects would not be affected by the non-existence of time, since neither that they are nor the way they fundamentally are in any way depends on time. But given that time does exist and its instants do serve as perspectives, the question arises as to whether these atemporally obtaining facts also obtain perspectivally—whether, that is, what is ‘visible’ from the atemporal perspective can also be ‘seen’ from temporal perspectives. cd-pluralism is perfectly consistent with allowing facts of the atemporal realm not to be quarantined from temporal perspectives, with the atemporality of facts entailing their sempiternity. Thus, given that the number 2 exists and is a prime, it exists and is a prime from all temporal perspectives. But this does not change the fact that the number 2’s existence and being a prime is a fundamentally atemporal matter: the sempiternity of atemporally obtaining facts is a derivative one. Therefore, the po-facts involving an atemporal object will all be grounded in their atemporal counterparts sharing the same components:

derivative sempiternity of atemporals (dsa)

For any atemporal object o and property F, if o is F, then, for any time t, as of t, o is F, because o is F.

Turn now to temporal objects. cd-pluralists will naturally be attracted by the idea that, in reality, what happens in time stays in time—that all facts involving temporal things and whatever properties they have at the temporal locations they occupy obtain in a temporally perspectival way, rather than atemporally. Since occupying a time, having a temporal location, is something that ‘takes place’ in time, the atemporal notion of existence will not apply to temporal objects—the question of whether or not Fido exists, for instance, constitutes a category mistake. Fido just is not the sort of thing to which this atemporal notion applies, or the sort of thing that can simply be some way: all of the facts that comprise him are perspectivally obtaining ones like [Yellow(Fido)]t1. Whether or not a temporal object and some property compose a fact is always a perspectival matter; any way that a temporal object is is a temporally perspectival way it is.

It might seem that, in the face of the diversity of objects, the cd-pluralist’s distinction between temporal, atemporal, and non-temporal objects is just too neat to be true. Indeed, what Fine (2005a, p. 352) calls “hybrids” and characterises as “objects that have constituents that exist in time even though they themselves do not” might be thought to spell trouble for the cd-pluralist, as they do not seem to clearly fit any of her categories. Given that singleton Socrates, for instance, is an abstract object, it seems natural to say that it atemporally exists. However, it is also exceedingly plausible that its existence is grounded in that of Socrates. But then how could it be that singleton Socrates exists, while Socrates does not?cd-pluralists need not be troubled by this particular issue. It seems plausible in general that a set such as singleton Socrates ‘inherits’ the location of its sole member.Footnote 16 Call an object strongly temporal if it is located at a temporal region in virtue of occupying it, and weakly temporal if it is located at a temporal region in virtue of standing in some ‘intimate’ relation to a strongly temporal object that occupies that region. Now, even if singleton Socrates, unlike Socrates, is not strongly temporal, it can still be plausibly understood as weakly temporal: it is located at all and only the times occupied by Socrates, not because it too occupies them, but rather merely on account of having Socrates as member. Thus, the cd-pluralist can consistently deny that objects like singleton Socrates pose a problem for her view: neither Socrates nor, therefore, singleton Socrates exists; they both exist as of certain times, but not others.Footnote 17

But even if her tripartite distinction itself is granted to the cd-pluralist, it might still be worried that her view posits too tight a connection between the temporal-locational kinds of objects and the modes of obtaining of the facts involving them. Indeed, Fine (2005a) argues that some facts concerning straightforwardly temporal objects must be understood as obtaining atemporally. The primary examples Fine mentions are facts about certain ‘formal’ properties of temporal objects as well as their essential features that constitute what he (2005a, p. 348) calls their “skeletal ‘core’”. Fido’s self-identity, for instance, does not seem to be a properly temporal matter. It is not just that Fido is self-identical as of any time as of which he exists; rather, his being self-identical seems to be thoroughly insensitive to time, just as atemporally obtaining facts are. Similarly, what sort of substance Fido is, his being a dog, does not seem to be something that is properly perspectival. It thus appears that, contrary to what the cd-pluralist claims, some of the facts that involve Fido are in fact atemporally obtaining ones, even though he certainly is a temporal object: fundamentally speaking, Fido is self-identical and is a dog. Or so Fine argues.

What these apparent counterexamples to cd-pluralism suggest is that the instantiation of certain kinds of properties, such as self-identity or substance sortal properties, is an essentially atemporal matter, regardless of the temporal-locational kind of the object that instantiates them. Accepting this would result in a fairly ‘watered down’ version of perspectivalism: before, we were supposing that the entire realm of temporal objects is unreachable from the atemporal perspective, but given the proposed amendment, a number of facts involving temporal objects will become ‘visible’ from that perspective. Further, this modification will have rather drastic ontological consequences as well. If any object whatsoever is self-identical, then one is thereby led to say that any object whatsoever exists—for how could something have the property of being self-identical without existing?Footnote 18 And given dsa above, it follows that any object whatsoever exists from every temporal perspective. This, by itself, constitutes a huge concession to the atemporalist; but beyond that, it appears to simply dismiss the whole debate over temporal ontology out of hand.Footnote 19 If, as is plausible, perspectivalism about temporal reality is to serve as what is common to the different ontological versions of the A-theory, it had better distance itself from the idea that any object whatsoever exists.

The key intuition behind Fine’s argument is the thought that facts like Fido’s self-identity or his being a dog are not sensitive to time in the way that ordinary po-facts are. But this intuition can in fact be accommodated without endorsing Fine’s own conclusion that the relevant facts must be atemporally obtaining ones. This will require us to take a closer look at the components of facts that we have ignored so far, namely properties (or predicables, more generally).

On the picture presented above, the temporal-locational kind to which an object belongs dictates what kind of fact it can compose. Atemporal objects fundamentally participate in atemporal composition of facts, and also, derivatively, in temporally perspectival composition. Temporal objects, by contrast, exclusively participate in the composition of a fact that occurs from within a temporal perspective. A similar distinction can be drawn in the case of properties. Call a property temporally neutral (neutral, for short) if it can participate in both kinds of composition, and essentially perspectivally instantiable (epi-property, for short) if it lies in the very nature of the relevant property that it can only be instantiated in a perspectival manner. If o is an atemporal object, then it can only compose a fact together with a neutral property. If o is a temporal object, it can only participate in perspectival composition, but can be coupled with either a neutral property or an epi-property. In the former case, the perspectivality of the fact is grounded solely in the temporal nature of the object—the neutral property itself makes no contribution to it. Fido’s self-identity is an example for such a case: even though self-identity itself is a neutral property, Fido’s self-identity is a perspectival matter because it is Fido’s self-identity. In the latter case, by contrast, both the object and the property require that the composition be perspectival—Fido’s being a dog, for instance, constitutes such a case, since being a dog is an epi-property.

Given the perspectival notion of fact composition, there is a question about the frequency of the composition of a fact by any given object-property pair, a question about as of how many times some object o and some property F compose a perspectivally obtaining fact. Call a property of an object o that o instantiates as of every time as of which o exists a constant property of o. In some cases, a property is a constant property of a temporal object because, as a matter of fact, from each of the relevant perspectives, the object happens to instantiate the property. Fine correctly points out that the constancy of self-identity of a temporal object or its being the kind of thing it is cannot be like that: the constancy of Fido’s being self-identical or his being a dog seems to rest on something more solid and less haphazard. But it does not follow that Fido’s having these properties are atemporal matters. The manner in which an object and a property compose a fact when they do is one issue, how often they in fact do compose a fact in that manner is quite another—and the former can be time-sensitive, while the latter is not, in a certain sense.

Let me illustrate this last point. Call a constant property of a temporal object essentially perspective invariant (invariant, for short) if its very nature is such that, given some object o, it is instantiated by o either as of all times as of which o exists or as of none of them. Both a neutral property, such as self-identity, and an epi-property, such as being a dog, can be invariant. Now, the sense in which o’s F-ness, where o is a temporal object and F an invariant property, may be said not to be ‘properly’ perspectival is that it is in virtue of F’s being invariant that o and F’s compositional behaviour with respect to each other does not vary from one perspective to the next—the transperspectival constancy of instantiation is guaranteed by F’s nature alone. Non-invariant properties like yellowness are not like that: they may very well be a constant property of some object, but there is nothing in their nature that requires this. Thus, the intuition that Fido’s self-identity or his being a dog are not sensitive to time in the way that ordinary po-facts are is true; but the insensitivity in question is associated with the constancy of composition rather than the mode. Ordinary po-facts comprise non-invariant properties, while po-facts like Fido’s self-identity or his being a dog involve invariant ones—this is the relevant contrast between them.

Consider, finally, non-temporal objects, instants of time. Since their existence is not a matter of their being temporally located, times do enjoy atemporal existence. Every time also exists from every temporal perspective, yet this sempiternity is not derivative, as opposed to that of atemporal objects, but rather fundamental. Thus, the whole of time is visible from both the atemporal standpoint and any one of the temporal perspectives—fundamentally speaking, all times both exist and exist from each temporal perspective.Footnote 20 This does not mean, however, that all features of time are equally visible from the atemporal perspective as well as from any given temporal perspective. In keeping with their intermediary character as non-temporal objects having one foot in the atemporal realm and one in the realm of temporal perspectives, times can participate in both atemporal and temporally perspectival composition of facts, depending on the nature of the predicable involved. Facts about which time precedes which, for instance, are atemporally obtaining ones, since temporal precedence is a neutral (and invariant) relation. On the other hand, some of the facts comprising times concern their epi-properties and are therefore po-facts—indeed, as will be discussed shortly, some of these take centre stage in a perspectivalist metaphysics.

The overall picture that emerges from cd-pluralist perspectivalism looks like this. While there indeed is an atemporal perspective upon reality, the atemporalist goes astray in thinking that all of reality would fully reveal itself to one who adopts this perspective. Quite the contrary, what is ‘visible’ from that perspective is merely the atemporal realm, while the entire temporal reality remains completely hidden from sight. Imagine that you are standing in front of the windowed façade of a large building. The windows are fully blacked-out and each belongs to a separate room. Now, while the windows themselves, their order, and the distance between any two of them, are clearly visible from your perspective, you cannot at all see from where you stand the insides of those windowed rooms. Staring at the façade of the building will not get you any closer to finding out what is going on within any of those rooms—in order to see that, you need to open one of the windows up and take a look.Footnote 21

5 On the plurality of realities

Unlike atemporalist views, most versions of perspectivalism will not accommodate a single unified notion of reality at the fundamental level. Thus, in a typical perspectivalist metaphysics, there will be multiple complex entities that can go by the name of “reality”. This results from two commitments which most perspectivalists will incur. First, pluralism about constitution will naturally lead to pluralism about what gets constituted. For the perspectivalist who endorses cd-pluralism, for instance, there is, on the one hand, the atemporally existing whole composed by all of the atemporally obtaining facts, which we may call atemporeality. On the other hand, po-facts also compose, as of whatever time as of which they obtain, a perspectival reality, which is, from within the relevant temporal perspective, the whole that comprises all the facts.

The second commitment that is relevant in this context concerns how many temporal perspectives there are. The idea that only a single privileged time serves as a perspective is in principle compatible with perspectivalism. However, there is good reason to think that a mono-perspectival account of this sort cannot do justice to d-temporalism (or td, more precisely).Footnote 22 Endorsing multi-perspectivalism with a maximally egalitarian perspectival policy, holding that any time whatsoever serves as a perspective, is therefore certainly the way to go for a perspectivalist who is concerned with accommodating d-temporalism. Given multi-perspectivality, however, there will be many distinct perspectival realities. In Fido’s world, for instance, one such perspectival reality is realityt1—the complex entity that is, as of t1, the whole composed by all the facts that obtain and thus has the fact that Fido is yellow as part. But, as of t2, no such fact obtains, and hence no such fact is part of the distinct perspectival reality realityt2, which instead comprises the fact that Fido is brown.

It thus appears to follow from multi-perspectivalism that there is no single complex entity that would correspond to what one might intuitively think of as all of temporal reality. Rather, there fundamentally is a plurality of distinct, non-integrable perspectival realities. Temporal reality is fundamentally multi-perspectival; it fundamentally comes in separate perspectival pieces, without there being any more basic level of reality at which those pieces come together in some form.Footnote 23

However, there is in fact a way in which the perspectivalist can understand temporal reality as a single composite entity distinct from any of her particular perspectival realities. Note that the notion of composition that we have considered above is an intraperspectival one: realityt1, for instance, is a composite that exist only from within the perspective of t1, made up by facts that obtain as of t1. But the perspectival framework does actually allow for a different, transperspectival notion of composition as well. This can plausibly be modelled after what Fine (1999) calls variable embodiment. Fine (1999, p. 68) introduces the concept by means of the following example:

We may talk of “the water in a river.” But this phrase may be understood in two rather different ways. On the one hand, it may be taken to signify that given quantity of water that is, at a given time, the water in the river. In this sense of the phrase, the water in the river at one time is rarely, if ever, the same as the water at another time. On the other hand, the phrase may signify a variable quantity of water—that water, whatever it is, that is in the river. It is in this sense of the phrase that we may say that the water in the river is rising, since it is the very same thing that was once relatively low and now is relatively high.

I take it that the water in the river in the second sense—what we may call the variable water—is now constituted by one quantity of water and now by another. But what is the variable water? Clearly, it is not any one of the quantities of water that is in the river at any one time. Nor is it the aggregate of all such quantities … What then can we take the variable water to be?

Fine (1999, pp. 68–69) argues that the variable water is the kind of whole whose principle of unity is a function from times to some particular quantity of water: the variable water exists whenever there is some quantity of water in the river, and at any given time at which the river exists, the variable water is constituted by the quantity of water that is in the river at that time. Thus, the identity of the whole that is the variable water does not depend on any one of the particular ‘material’ parts of it, but rather only on its form that is given by its functional principle of unity. The particular quantities of water that exist at a given time are the “manifestations” of the variable water; the latter composite entity manifests itself through particular quantities of water by being constituted by them at a given time.

I wish to suggest that, given perspectivalism, talk of temporal reality is analogous to talk of the water in the river. In one sense, “temporal reality” designates some particular perspectival reality that is an intraperspectival composite, such as realityt1. However, the expression can also be used to refer to a transperspectival composite: temporeality. Just as Fine’s variable water is not any one of the particular quantities of water that is in the river at a given time, nor simply the aggregate of them, temporeality is identical neither to any one of the particular perspectival realities nor to the aggregate of them. Rather, the identity of this whole is given by the principle that may be spelled out by the description “the maximal structural whole of all facts”, which takes perspectives as input and returns a particular perspectival reality as output. temporeality exists as of any time as of which some particular perspectival reality exists; any such particular reality is a manifestation of temporeality. Thus, the individual perspectival realities do, after all, compose something, but what they compose is neither of an atemporal nor of an intraperspectival sort. Rather, it is a sui generis, transperspectival type of composite.Footnote 24

Fine (2005b, p. 282) recognises that a view like perspectivalism will involve “a distinction between a single comprehensive über-reality and a plurality of more particular realities.” He (2005b, p. 283) then goes on to suggest that one can think of this “über-reality” in following terms:

One might say that über-reality ‘manifests itself’ in the form of the particular realities, that it becomes ‘alive’ or ‘vivid’ through the particular realities obtaining. Each particular reality presents itself as the whole of reality. It creates the illusion, if you like, that there are no further facts, even though there are many such realities and each is equally real.

The picture of temporeality as a transperspectival composite presented above comes quite close to Finean “über-reality” as characterised in this passage. From within the perspective of any t, realityt is the full extent of reality; but any such particular perspectival reality is also only one of the infinitely many manifestations of temporeality. As Fine (2006, p. 403) cautions, however, “in saying this we must recognize that there is no underlying reality, of the usual sort, of which these different realities are a manifestation. The differential manifestation of how things are is itself integral to the very character of reality.” temporeality seems tailor-made for the part Fine is describing here: it is certainly not “of the usual sort” and is not something that “underlies” the particular perspectival realities that compose it. Moreover, given that it is a variable embodiment, a transperspectival composite, “the differential manifestation” that Fine speaks of is part of its very nature, its very essence: that temporeality manifests itself in this differential manner is part of what makes it the sui generis kind of whole that it is.

6 Accessibility and transparency

Since the atemporal realm is inhospitable to temporal objects and epi-properties, neither aspect of the dual nature of times reveals itself from the atemporal perspective: from that perspective, times figure neither as locations nor as perspectives. But from any given temporal perspective, every temporal location is visible: from every temporal perspective, there obtain facts about whether or not a time is occupied by a temporal object and what properties some such object has at the relevant location. And from every temporal perspective, every temporal vantage pointFootnote 25 is visible and accessible: from every temporal perspective, there obtain facts about what is visible from any given vantage point.Footnote 26

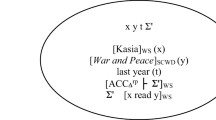

The accessibility of the vantage point of t from the perspective of t* is a matter of there being facts of the form ⌈[Πt(φ)]t*⌉.Footnote 27 Such facts are both po-facts and p-facts at the same time—facts with a perspectival content that also have the perspectival mode of obtaining. More concretely, in Fido’s world, for instance, from the perspective of t2, the vantage point of t1 is accessible, which means that, from the perspective of t2, it is visible that, from the vantage point of t1, such and such is visible. Hence, [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2, the fact that, from the vantage point of t1, Fido is yellow, is a fact that obtains as of t2 and is among the components of realityt2; and mutatis mutandis for [Πt3(Blue(Fido))]t2. Such facts can be understood as constituting the way t1 and t3 are, as of t2, in their capacity as vantage points. More precisely, what it is for [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))] to obtain, as of t2, is for t1 to instantiate, as of t2, the perspectival property (p-property, for short) denoted by λx[Πx(Yellow(Fido))]. Given that times do not at all figure as perspectives from the atemporal perspective, all such p-properties of times are epi-properties.

Note that it does not follow from the obtaining of such facts as [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2 and [Πt3(Blue(Fido))]t2 that what would be denotable by “[Yellow(Fido)]t2” and “[Blue(Fido)]t2” are also parts of realityt2. In other words, the t-perspectival accessibility of the vantage point of t* does not in general entail the t-perspectival visibility tout court of whatever is t-perspectivally visible from the vantage point of t*. But there is one special case in which the relevant entailment does indeed hold. For, from the perspective of any time t, the vantage point of t itself is privileged in being transparently accessible (or simply, transparent): from the perspective of any given time t, whatever is visible from the vantage point of t itself is visible tout court. After all, for any time t, the perspective of t precisely is the perspective that ‘centres on’ the vantage point of t—that vantage point is the vantage point of the perspective in question. Thus, t2 has, from its own perspective, the property of being such that whatever is the case from its own vantage point is the case tout court and vice versa—the property denoted by λx[∀φ(Πx(φ) ↔ φ)]. realityt2 comprises, alongside p-facts concerning the vantage points of times other than t2, such as [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2 and [Πt3(Blue(Fido))]t2, also p-facts concerning the vantage point of t2 itself, such as [Πt2(Brown (Fido))]t2. But this latter fact simply reduces to the fact [Brown (Fido)]t2—from the perspective of t2, t2’s having the property of being such an x that, from the vantage point of x, Fido is brown just is Fido’s being brown.

Facts about the p-properties of times, such as [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2, are doubly perspectival: they feature both componential and constitutional perspectivality, or have both a perspectival content and a perspectival form. But their perspectival content can itself be explained in terms of constitutional perspectivality. For what intuitively ‘fixes’ what p-properties a time has, from its own perspective, are simply the po-facts that obtain from that very perspective. Suppose now that there is a metaphysical law requiring that a time retains the p-properties it has from its own perspective across all perspectives whatsoever:

stability of p-properties (spp)

For any time t, if, from the perspective of t, t has some p-property F that can be designated by ⌈λx[(Πx(φ)]⌉, then, for any time t*, from the perspective of t*, t has F.

Given spp, what explains [Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2 is not some other fact obtaining from the perspective of t2, but rather the fact [Yellow(Fido)]t1, which is what ‘imparts’ the p-property denoted by λx[Πx(Yellow(Fido))] onto t1 in the first place.Footnote 28 In this way, some parts of a given perspectival reality, those that concern the p-properties of times other than the time the relevant perspective ‘centres on’, are explained by parts of other perspectival realities.Footnote 29

7 Compartmental properties

Apart from the p-properties discussed above, the epi-properties of times also include their compartmental properties, the properties of being present, being past, and being future, which underlie the compartmentalisation of time into distinct temporal zones.Footnote 30 Since these are epi-properties, no time has them: from the atemporal perspective, time is not compartmentalised in any sense. But from the perspective of any time whatsoever, each time has exactly one of the three compartmental properties.

What sort of properties are these compartmental properties? Well, pastness and futurity can be straightforwardly analysed in terms of presentness and temporal precedence: what it is for a time to be past (future) is for it to be earlier (later) than the time that is present. Thus, from the perspective of any time t, any time t* that is earlier (later) than t is past (future). What about presentness? It is in principle consistent with perspectivalism to take presentness as a primitive epi-property of times. However, within the perspectivalist framework, it is possible to give a more informative account of presentness, one that construes this property as something inherently connected with the fundamentally perspectival structure of temporal reality. On perspectivalism, no time is present. Nor is there a unique, privileged temporal perspective from which a single time is present. Rather, presentness is something that each time has from within its own perspective, in its own temporal way, and lacks from within the perspective of any other time. While there is a sense in which it is something that all times ‘have’ in common, it is not something that they have in common; nor is there a temporal perspective from which they have it in common. But notice now that we have already encountered a property that exactly fits this profile: the property of being a time whose vantage point is transparent. From the perspective of any given time t, t itself is uniquely privileged as the time whose vantage point is the one that the relevant temporal perspective centres on and the relevant perspectival reality originates from. Each and every time enjoys this privilege from its own perspective, but neither from the atemporal perspective nor from the perspective of some distinct time. Given this, the perspectivalist can plausibly identify presentness with the property of being a transparent vantage point.Footnote 31

In the literature on the A/B-debate, it is frequently asserted that an A-theoretic conception of temporal reality requires there to be an ‘objective’ and ‘absolute’ present time.Footnote 32 Exactly what is meant by this is not always clear, but as far as ‘objectivity’ is concerned, it is important to emphasise that there is nothing ‘subjective’ about the perspectivalist conception of presentness. That, as of t1, t1 is present (that is, is the time whose vantage point is transparent) is as objective a fact as it gets—it is not a matter of opinion or up to any sort of ‘subject’ whether a time is, as of some time, present or not. To be sure, facts about the presentness of a time are po-facts and have the perspectival mode of obtaining—the privilege a time enjoys, in its capacity as the present time, is an intraperspectival matter, and since there are multiple temporal perspectives, more than a single unique time can in fact enjoy that privilege, each from its own perspective. But it is worth noting that facts about the presentness of a time, or facts about the compartmentalisation of time more generally, do not feature any componential perspectivality. This is in contrast to a-perspectivalism. The a-perspectivalist will similarly claim that, from the perspective of each time t, t is present. But on that account, t1’s presentness from its own perspective, for instance, will amount to the fact [Πt1(N(t1))]a (where “N” means “is present”)—a fact with a perspectival content that nevertheless obtains atemporally. The c-perspectivalist, on the other hand, conceives of t1’s presentness from its own perspective in terms of [N(t1)]t1. Thus, while it is true that t1 and the property of being present compose a fact only from within the perspective of t1, there is nothing perspectival about the components of what gets composed in this way. In this sense, from within the perspective of t1, t1 is present ‘absolutely’, in an unqualified manner—or in a manner that is “relatively absolute”, as we may put it following Fine (2005b, p. 280).

8 Tensed vs. tenseless facts

Appealing to tensed or tenseless facts is quite commonplace in the metaphysics of time, yet one seldom finds any clear and metaphysically substantial answer to the question of what it is for a fact to be tensed or tenseless. This is all the more worrying, given that the presence or absence of tense is primarily a morphological feature of verbs, and derivatively of sentences containing them, which is why the question has no obvious answer. One could, of course, say that a tensed (tenseless) fact is one that can only be correctly designated by a tensed (tenseless) sentence. But, presumably, this truth must depend on some feature of the relevant facts themselves, and we are still in the dark as to what that feature might be. The perspectivalist framework promises significant progress in this regard: just as the notion of temporal compartmentalisation, the notion of a tensed fact can be understood in terms of a fundamental perspectival structure.

Consider first the following basic observation about the contrast between tensed and tenseless representation. It is uncontroversial that a tensed sentence ⌈a was F⌉ encodes temporal information—but so does a tenseless sentence ⌈a is F at t⌉. One clear difference between the two is that the tensed sentence encodes pastness, while the tenseless one does not. But beyond that, there is a difference in the manner in which these two sentences are directed at a time. Although the tenseless sentence is directed at a time, its ‘gaze’, as it were, is not itself a temporally embedded one. The tensed sentence, by contrast, says something about the world by pointing, from within the standpoint of a certain time, into another, earlier time—it ‘looks’ at a’s past F-ness from within the perspective of the present. What is distinctive about tensed representation is, in short, that it is temporally perspectival representation.

Something perfectly analogous seems to be going on with tensed facts, however exactly they are to be understood. If the fact [a was F] obtains and constitutes reality, then it is directed at a past time in the sense that what is supposed to be the case in virtue of the obtaining of this fact concerns the past; yet the fact is anchored at the present time in the sense that its obtaining and constitution of reality is a present matter. Tensed facts do not merely concern times and what is going on at them—rather, their very obtaining is a temporal affair.

In a perspectivalist metaphysics, the inherent temporal anchoredness of tensed facts, which distinguishes them from temporally unanchored tenseless facts, can be understood as directly corresponding to something in the fundamental structure of reality. For, given perspectivalism, temporal anchoredness will plausibly be analysed in terms of the perspectival mode of obtaining: what it is for a fact to be anchored at a time is for it to obtain from the perspective of that time. And given that temporal anchoredness is the trademark of tensed facts, the perspectivalist will take the tensedness of a fact to consist precisely in its constitutional perspectivality:

perspectivality of tensedness (pot)

What it is for a fact to be tensed just is for it to obtain in a temporally perspectival manner.

Similarly, the perspectivalist will associate the temporal unanchoredness of tenseless facts with their atemporal mode of obtaining, which leads to the following account of the tenselessness of facts:

atemporality of tenselessness (aot)

What it is for a fact to be tenseless just is for it to obtain atemporally.

Given pot and aot, the difference between tensed and tenseless facts is a matter of the difference between their respective forms rather than any difference concerning their contents—the status of a fact with respect to tense is a fundamentally constitutional, rather than componential, matter. Note further that, given pot, c-perspectivalism entails, and is entailed by, realism about tense; similarly, given aot, atemporalism entails, and is entailed by, anti-realism about tense. Perspectivalists, then, are realists about tense, after all, but ones who have a clearer picture of what they are realists about.

9 The varieties of tensed facts

A tensed fact is never just plain tensed; it is either present-, past-, or future-tensed. The perspectivalist’s story so far tells us what it is about a fact that makes it at all tensed as opposed to tenseless; it does not tell us what it is about a tensed fact that makes it, say, past- rather than future-tensed. While being temporally anchored, having the perspectival mode of obtaining, distinguishes a tensed fact from a tenseless one, the particular ‘compartmental flavour’ in which a tensed fact comes is a matter of the compartmental property of the time at which it is directed: a present-tensed fact is directed at a time that is present, a past-tensed fact at a time that is past, and a future-tensed fact at a time that is future.

We should keep in mind, however, that, in a perspectival metaphysics, times lead a double life, serving both as temporal locations and as temporal vantage points; and this key feature of times results in a ‘tense structure’ that is more complex than is typically recognised.Footnote 33 For when a tensed fact is directed at a time with some compartmental property, that time can thereby be ‘treated’ either as a location or as a vantage point—a time can be the ‘target’ of a tensed fact either in its capacity as a location or in its capacity as a vantage point. In other words, a tensed fact can either be directed at a present, past or future location and hence concern what is going on in the present, past, or future, or it can be directed at a present, past or future vantage point and concern what is going on accord-ing to the present, past, or future.Footnote 34

The standard way of understanding tensed facts construes them as facts to which one can refer by expressions ⌈[pres(φ)]⌉, ⌈[past(φ)]⌉, and ⌈[fut(φ)]⌉, where “pres” stands for the present-tense, “past” for the past-tense, and “fut” for the future-tense operator (read as “It (is presently/was/will be) the case that”, respectively). On perspectivalism, such expressions will not do, as they lack the subscription of the time at which they are supposed to be anchored, signalling their perspectival mode of obtaining. But even the modified expressions ⌈[pres(φ)]t⌉, ⌈[past(φ)]t⌉, and ⌈[fut(φ)]t⌉ fail to refer to a single sort of tensed fact and are ambiguous between two different readings. Think of the standard tense operators as encoding the compartmental property of the time at which the fact is supposed to be directed, specifying whether it is present, past, or future. This leaves it unclear whether the fact is supposed to concern a temporal location or a vantage point. To disambiguate, we can distinguish between two types of tense operators that not only encode a compartmental property, but also whether the ‘target’ time is to be ‘treated’ as a location or vantage point. Thus, we will have, on the one hand, expressions containing tenseloc operators: ⌈presloc(φ)⌉, ⌈pastloc(φ)⌉, and ⌈futloc(φ)⌉ (read as ⌈In the (present/past/future), φ⌉, respectively). On the other hand, there are also expressions containing tensevp operators: ⌈presvp(φ)⌉, ⌈pastvp(φ)⌉, and ⌈futvp(φ)⌉ (read as ⌈According to the (present/past/future), φ⌉, respectively).

Let us elaborate on the distinction between tenseloc and tensevp operators by looking at some examples. In Fido’s world, for instance, we have the fact,

-

(α)

[presvp(Brown(Fido))]t2.

which is a component of realityt2. As already mentioned, tensevp operators encode both the compartmental property of the ‘target’ time and that it is ‘treated’ as a vantage point. In view of this, we can analyse the operator presvp in terms of presentness and the vantage-point operator Πt. Think of presvp as a special, present-vantage-point operator, Πpres (read as “from the vantage point of the present time”), which is, from within the perspective of any given time t, equivalent to Πt, given that, from the perspective of any t, t itself is uniquely present. Thus, α can be construed as

-

(β)

[Πpres(Brown(Fido))]t2.

which is identical to the fact,

-

(γ)

[Πt2(Brown(Fido))]t2.

And since, from the perspective of t2, the vantage point of t2 is transparent, we can get rid of the perspective operator altogether:

-

(δ)

[Brown(Fido)]t2.

The transition from α to δ attests a general feature of the perspectivalist account of tensed facts, one that is rooted in its conception of tensedness as anchoredness. For notice that, any time at which some fact is anchored, any time from whose perspective some fact obtains, is, from that very perspective, uniquely present—any particular perspectival reality is composed by facts that are anchored at a time that is, as far as that perspectival reality is concerned, the one and only present time. Hence, being anchored at a time is always, inevitably, being anchored at a present time. But given that, from within any temporal perspective, the vantage point of the present time is transparent, a tensed fact cannot but be directed at the vantage point of the present time: whatever things and their properties a temporally anchored fact ‘concerns’, it will automatically end up ‘concerning’ how those things and properties appear from the transparent vantage point of the time at which it is anchored. And conversely, the only possible way for a tensed fact to be, from within the perspective of some time, directed at the vantage point of a time that is present is by being anchored at, or obtaining as of, that very time. Temporal anchoredness is therefore the unique and universal source of present-tensednessvp: any given tensed fact whatsoever constitutes the way things presentlyvp are, given that it constitutes a way things are from the perspective of a time, which is, from that very perspective, present. Any particular perspectival reality is exclusively constituted by present-tensedvp, facts that constitute what is presentlyvp the case, even if some of them also concern, from within the perspective of the time at which they are anchored, non-present vantage points and/or locations.Footnote 35 Hence, any tensed fact that is denotable by ⌈[φ]t⌉ is also denotable by ⌈[presvp(φ)]t⌉, or, equivalently, by expressions like ⌈[Πpres(φ)]t⌉ and ⌈[Πt(φ)]t⌉, and vice versa, however complex “φ” may be.

Let us continue with past- and future-tensedvp facts. realityt2 also comprises the following two facts:

-

(ε)

[pastvp(Yellow(Fido))]t2.

-

(ζ)

[futvp(Blue(Fido))]t2.

In analogy with the way we have construed presvp, we can analyse pastvp and futvp in terms of Πt and pastness or futurity, respectively (where “P” means “is past” and “F” means “is future”):

-

(η)

[∃t(P(t) & Πt(Yellow(Fido)))]t2.

-

(θ)

[∃t(F(t) & Πt(Blue(Fido)))]t2.

Assuming that existential facts, in general, are grounded in their instances, what grounds η is the fact.

-

(ι)

[Πt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2.

while θ is grounded in the fact

-

(κ)

[Πt3(Blue(Fido))]t2.

And given spp above, ι and κ themselves are further explained in terms of [Yellow(Fido)]t1 and [Blue(Fido)]t3, respectively.Footnote 36

Turn now to tensedloc facts, and consider the following example:

-

(λ)

[presloc(Brown(Fido))]t2.

Let us introduce a temporal-location operator, designated by ⌈Λt⌉ and read as ⌈At the location of t⌉ or more simply as ⌈At t⌉. In exact analogy with the case of presvp, we can construe presloc as a special present-location operator, Λpres (read as “at the present location” or simply as “at present”), which will be, from within the perspective of any given time t, equivalent to Λt. Thus, λ will be understood in terms of.

-

(μ)

[Λpres(Brown(Fido))]t2

which further reduces to

-

(ν)

[Λt2(Brown(Fido))]t2.

Now, just like any other tensed fact, ν is present-tensedvp as well, and is therefore identical to the fact.

-

(ξ)

[Πt2(Λt2(Brown(Fido)))]t2.

But contrast now ξ with δ (or γ) above. ξ constitutes a more ‘specific’ way things are from the perspective of t2: given δ, we know that Fido’s brownness is part of realityt2, but given ξ, we also know where in time Fido’s brownness, as part of realityt2, is located at. Thus, assuming that, from the perspective of any given time t, temporal objects can be located at times distinct from t and instantiate properties at those locations, ξ’s obtaining entails δ’s obtaining, but not vice versa.Footnote 37

Suppose now that, from the perspective of t2, Fido is located at t1 and t3 as well, and has at those non-present locations exactly the same properties he has at them from the perspectives of t1 and t3, respectively. If this is true, then realityt2 also comprises the following two facts:

-

(ο)

[Λt1(Yellow(Fido))]t2.

-

(π)

[Λt3(Blue(Fido))]t2.

But given that, from the perspective of t2, t1 is a past and t3 a future location, ο and π ground, respectively, the facts.

-

(ρ)

[∃t(P(t) & Λt(Yellow(Fido)))]t2.

-

(σ)

[∃t(F(t) & Λt(Blue(Fido)))]t2.

which we can identify, respectively, with the facts.

-

(τ)

[pastloc(Yellow(Fido))]t2.

-

(υ)

[futloc(Blue(Fido))]t2.

Before moving on, let me briefly address a general issue about the ‘status’ of the perspectivalist account of tense. Within the traditional A/B-debate, the question of whether a theory of time offers a ‘reductive’ account of tense or not is commonly regarded as quite significant: while B-theorists are supposed to be reductionists who take tensed sentences to have tenseless truth-conditions, A-theorists are supposed to reject reductionism and view tense as fundamental. What about the account of tensed facts presented above? Well, for the perspectivalist, both tensed facts and compartmental properties of times can be explained in terms of the perspectival form of temporal reality—in this particular sense, neither tense nor compartmental properties are fundamental or primitive. On the other hand, the perspectivalist does not seek to account for these ‘A-theoretic’ phenomena in tenseless terms, by appealing to atemporal facts. Quite the contrary, on perspectivalism, tense can be regarded as part of the fundamental structure of reality, given that the tensedness of facts just is their perspectivality. The perspectivalist, as we may put it, does take tense very seriously, though unlike the traditional A-theorist, just not too literally.

10 ‘Exporting’ the perspectivalist account of tense

The rather high level of sophistication that the perspectivalist account of tense involves makes it particularly important to demonstrate what concrete philosophical work this account can be put to. But trying to accomplish this within the framework of perspectivalist metaphysics would require going into certain intricacies concerning temporal ontology, which goes well beyond the scope of this paper. The cases we will address here will therefore be ones that pertain to the B-theory rather than any version of perspectivalism. This might come as a surprise but the perspectivalist account of tensed facts is in fact available to B-theorists, or more generally, atemporalists as well. These philosophers will certainly reject cp above, but they can very well accept pot and the perspectivalist construal of temporal anchoring and temporal directedness, as these are in fact independent of cp. In general, atemporalists of any stripe can allow reality to be genuinely constituted by tensed, perspectivally obtaining facts, while insisting at the same time that such facts are all ultimately grounded in atemporally obtaining facts.

In fact, it is not just that B-theorists can accept the perspectivalist approach to tense; in view of some issues “concerning the ‘tense-related’ implications of their view”, as Deasy (2020, p. 309) puts it, they would actually be well-advised to do so. Consider, for instance, the following puzzle. The standard B-theorist is supposed to be committed to eternalism, the view that all past, present, and future objects are on an ontological par, that any such object simply exists. Suppose, however, that we ask the B-theorist whether dinosaurs exist now—granted, there are dinosaurs, but is the sentence “Presently, dinosaurs exist”, understood as saying that pres(∃x(D(x)) (where “D” means “being a dinosaur”), true right now? Faced with this question, the B-theorist faces a dilemma. On the one hand, there seems to be a sense in which the B-theorist, qua eternalist, would want to affirm the question—affirming this is supposed to be one of the things that distinguishes her view from that of a presentist, for instance.Footnote 38 Indeed, how could the existence of dinosaurs fail to result in their sempiternal, and hence present, existence? On the other hand, as Deasy (2020, p. 271) points out, most, if not all, B-theorists appear to hold that tense operators are “implicit quantifiers over times which restrict the explicit individual quantifiers […] in their scope to things located at the relevant time(s)”. But given this, assenting now to “Presently, dinosaurs exist” amounts to thinking that at least one thing located at the time that is present now is a dinosaur, which any B-theorist would certainly want to reject.

A B-theorist who adopts the perspectivalist approach to tensed facts has an elegant way of resolving this puzzle. For on that approach, “pres(∃x(D(x))” is ambiguous between “presvp(∃x(D(x))” and “presloc(∃x(D(x))”, and these two readings correspond precisely to the two horns of the above dilemma. The sense in which the B-theorist would now want to say that, presently, dinosaurs exist is that, from the perspective of the time that is present now, dinosaurs exist; in fact, from dsa above and the fact that dinosaurs exist, it follows that, from the perspective of any time whatsoever, dinosaurs exist. Assuming that t1 is the time that is present now, what makes “Presently, dinosaurs exist” true now is the present-tensedvp fact [∃x(Dx)]t1, and this fact, just as the atemporal fact [∃x(Dx)]a, is silent on where in time dinosaurs are. However, the B-theorist can still insist, just like anybody else, that it is false that, presentlyloc, dinosaurs exist, that there is no such fact as what would have been denoted by “[Λt1(∃x(Dx))]t1”.

Deasy (2017, pp. 386–388, 2020) has recently raised a similar issue, which focuses on the tense operator some, read as “Sometimes”, typically understood by a B-theorist along the following lines: ⌈some(φ)⌉ is true at t if, and only if, at some time t*, φ. Now, Deasy argues that it seems plausible that this operator is governed by the principle that, for any φ, if φ, then some(φ)—for, as Deasy (2017, p. 387) puts it, “how could something be the case but never be the case?” But this principle, together with the above analysis of some, spells trouble for the B-theorist. Call any two things that share no temporal location temporally disjoint and consider the following sentence (where “TD” means “is temporally disjoint”):

-

(1)

∃x∃y(TD(xy)).

Clearly, (1) is true, as there are numerous instances of temporally disjoint objects. Given the aforementioned principle governing some, it follows from (1):

-

(2)

some(∃x∃y(TD(xy))).

But the B-theorist’s semantics for some seems to turn (2) into the contradictory claim that there is a time t such that some x and y that are located at t are temporally disjoint.

Once again, a B-theorist armed with the perspectivalist account of tense has a perfectly straightforward response to this argument. Given that account, just like any other tense operator, some actually comes in two varieties: somevp and someloc. (2) may well be understood as a tensedvp claim, made true now (assuming now is the time t1) by the fact [somevp(∃x∃y(TD(xy)))]t1, which reduces to [∃t(Πt(∃x∃y(TD(xy))))]t1. But none of this commits one to affirming the contradictory tensedloc reading of (2), which would require for its truth what would have been denoted by “[someloc(∃x∃y(TD(xy)))]t1”, or by “[∃t(Λt(∃x∃y(TD(xy))))]t1”, more precisely. Moreover, once the distinction between somevp and someloc is in place, the B-theorist can offer the following diagnosis for what is wrong with Deasy’s argument. The principle that Deasy believes to govern some is plausible only in the case of somevp—in fact, its truth can be understood to be grounded in dsa. But the semantics Deasy mentions is intended for someloc. The argument, therefore, equivocates.

11 Epilogue: accommodating deep temporality

Let us finally address, by way of conclusion, the question of how well the perspectivalist metaphysics outlined so far can accommodate d-temporalism. According to the perspectivalist, the key to vindicating deep temporality is ‘doubling down’ on the inherent perspectivality of tensed facts stemming from their temporal anchoredness by making it part of reality’s fundamental structure. Deep temporality, on this approach, is not a feature of the reality that is ‘visible’ from the atemporal perspective—time, as it appears from that perspective, is neither compartmentalised nor dynamic. This, however, does not mean that deep temporality is not fundamental, as the perspectivalist rejects the idea that the atemporal perspective upon reality is the ultimate perspective. Rather, some of the fundamental facts constituting reality are ones that obtain only from some temporal perspective, and the facts which ground reality’s deep temporality are among them.