Abstract

Several important philosophical problems (including the problems of perception, free will, and scepticism) arise from antinomies that are developed through philosophical paradoxes. The critical strand of ordinary language philosophy (OLP), as practiced by J.L. Austin, provides an approach to such ‘antinomic problems’ that proceeds from an examination of ‘ordinary language’ (how people ordinarily talk about the phenomenon of interest) and ‘common sense’ (what they commonly think about it), and deploys findings to show that the problems at issue are artefacts of fallacious reasoning. The approach is capable, and in need of, empirical development. Proceeding from a case-study on Austin’s paradigmatic treatment of the problem of perception, this paper identifies the key empirical assumptions informing the approach, assesses them in the light of empirical findings about default inferences, contextualisation failures, and belief fragmentation, and explores how these findings can be deployed to address the problem of perception. This facilitates a novel resolution of the problem of perception. Proceeding from this paradigm, the paper proposes ‘experimental critical OLP’ as a new research program in experimental philosophy that avoids apparent non-sequiturs of OLP, extends and transforms experimental philosophy’s ‘sources program’, and provides a promising new strategy for deploying empirical findings about how people ordinarily talk and think about phenomena, to address longstanding philosophical problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper will develop productive connections between two largely disparate traditions. Ordinary language philosophy (OLP) addresses philosophical questions and problems by examining ordinary language and common sense, i.e., how people ordinarily talk, and what they ordinarily think, about the topic of interest (knowledge, perception, responsibility, etc.). So does much experimental philosophy. Experimental philosophy can provide OLP with empirical methods and foundations. Conversely, OLP can provide experimental philosophy with new research agendas that engage more closely with the philosophical tradition.

Both as practiced in its mid-20th century heyday, e.g., by J.L. Austin (1946; 1957/1979; 1962) and Gilbert Ryle (1949; 1954), and as revived over the last decade (starting with Baz, 2012; Fischer, 2011; Garvey, 2014; Gustafsson & Sørli, 2011; Laugier, 2013), OLP comes in two main strands (Hansen, 2014, 2020). Constructive OLP employs ordinary language use as a tool of discovery: It moves from observations about how certain words are used to facts about the meaning of those words and then draws conclusions about the world those words are used to talk about (paradigm: Austin, 1957). Critical OLP employs ordinary language use as a tool of criticism: It seeks to ‘dissolve’ some longstanding philosophical problems by, among other things, identifying departures from established linguistic usage and common sense (paradigm: Austin, 1962). Despite sophisticated implementations, both constructive and critical OLP were often perceived as subjecting philosophical theses to a kind of opinion polling and involving related non-sequiturs, which prevented long-term take-up.

This programmatic paper will argue that experimental pursuit can provide critical OLP with much-needed empirical foundations that allow the approach to clearly avoid the apparent non-sequiturs; it will develop the approach in a new direction, and will provide experimental philosophers – who have to contend with similar ‘opinion polling objections’ (cf. Balaguer, 2016, p.2368) – with a fresh avenue for deploying empirical findings about how laypeople think and talk. Experimental implementation of critical OLP permits deploying such signature experimental philosophy findings to directly address longstanding philosophical problems – rather than contributing to philosophical debates more indirectly, by ‘merely’ assessing the evidence base of philosophical theories or adjudicating on burdens of proof (Stich & Tobia, 2016), or apparently not contributing to traditional philosophical debates at all, as when practicing experimental philosophy as cognitive science (Knobe, 2016). By engaging with critical OLP, this paper will build up to a new route from signature experimental philosophy findings to philosophically relevant consequences.Footnote 1

Critical OLP’s overarching aim of ‘dissolving’ – some – philosophical problems has been pursued in different ways, namely, by showing that the questions articulating the problems are meaningless (‘semantic dissolution’) or ill-motivated (‘epistemic dissolution’) (Fischer, 2011, pp.68–72). Accordingly, the approach is capable of various different empirical implementations. E.g., Austin (1962, pp.14–19) considers philosophers’ use of the phrase ‘directly perceive’ which is central to setting up the ‘problem of perception’ (Crane & French, 2021; Smith, 2002). He observes this use deviates from ordinary use, therefore requires proper explanation, but never receives any. He suggests philosophers are unable to give the phrase sufficiently determinate meaning when stretching its use in philosophical discourse. Such claims of ‘meaninglessness’ can be empirically assessed, as illustrated by a recent study that probed researchers’ (philosophers’, psychologists’, and neuroscientists’) understanding of ‘representation’, as used (stretched) in cognitive science. Favela and Machery (2022) employed elicitation methods to show the technical concept is unclear and confused: Users know neither what follows from applying it nor what should be the case for it to apply, and subsume distinct phenomena under it.Footnote 2 Such findings about terms central to setting up a targeted problem can be deployed for semantic problem dissolution.Footnote 3

The largest extant body of experimental-philosophical work directly inspired by critical OLP seeks to empirically support epistemic problem dissolution by exposing fallacious inferences in philosophical arguments that motivate targeted problems: Under the heading ‘diagnostic experimental philosophy’ (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2017a) or ‘experimental ordinary language philosophy’ (Fischer et al., 2021; Fischer, Engelhardt & Sytsma 2021), about ten studies (also including Fischer & Engelhardt, 2016; 2017b; 2019; 2020; Fischer, Engelhardt, & Herbelot, 2015; 2022) sought to empirically document and explain contextually inappropriate default inferences in the influential ‘arguments from illusion’ and ‘arguments from hallucination’ that jointly set up the ‘problem of perception’ that is the target of Austin’s Sense and Sensibilia (1962), the most pertinent extant paradigm of critical OLP.Footnote 4

The present paper will draw together the findings from this body of work and embed its specific approach in a more comprehensive research agenda that will lead to the proposal of a new research program: ‘experimental critical OLP’. The more comprehensive agenda is to provide critical OLP with empirical foundations by identifying, developing, and assessing the empirical assumptions that inform the Austinian approach and the problems it addresses. The agenda then has us explore how the relevant empirical findings – which will concern not only verbal reasoning but also folk beliefs – can be deployed to show that the targeted philosophical problems are ill-motivated. We will thus build up to a new paradigm of critical OLP, namely, an empirically supported epistemic dissolution of the problem of perception that is inspired by Austin’s treatment of the problem but opens up a new, broader perspective and might guide further contributions from experimental philosophy to critical ordinary language philosophy, that address other problems with a similar structure.

Section 2 will now identify key empirical assumptions informing, respectively, the Austinian paradigm of critical OLP and its target problem, the problem of perception. Sections 3–4 will then review empirical studies that have examined these assumptions. Section 5 will explore how the empirical findings can be deployed to ‘dissolve’ the target problem, in a way that avoids the apparent non-sequiturs of traditional critical OLP and develops this approach into a new direction. The resulting worked example will motivate the proposal of a new research program for experimental philosophy that examines the cognitive sources of a distinctive class of philosophical problems, with a view to undercutting philosophers’ warrant for addressing these problems.

2 Critical OLP and its target problems: Key empirical assumptions

Plato regarded a sense of wonder in the face of the familiar as starting point of philosophical reflection (n.d./2004, 155b–d). He had in mind puzzlement about the very possibility of familiar facts, rather than curiosity about their causes. This sort of puzzlement is the hallmark of one kind of characteristically philosophical problems, exemplified by sceptical problems and the problems of mental causation, free will, induction, and perception.Footnote 5 These problems are raised by intuitive lines of thought that rule out what common sense recognises as a familiar fact (e.g., that we acquire knowledge about our surroundings through our senses). Gradually developed into concise deductive arguments and conceptualised as paradoxes, these lines of thought appear to develop antinomies and motivate philosophical questions about the very possibility of the facts recognised by common sense but apparently ruled out by philosophical argument (e.g.: How is perceptual knowledge even possible?).

Critical OLP primarily addresses problems of this kind (e.g., Austin, 1946; 1962; Ryle, 1949; 1954), which I will call ‘antinomic puzzles’. Standard conceptions of these problems as well as the critical OLP approach to them rely on empirical assumptions that have been largely neglected, or simply taken for granted, in the relevant debates. We now consider the assumptions underlying the main Austinian paradigm of critical OLP and its target problem.

Austin’s Sense and Sensibilia (1962) addresses what is now called ‘the problem of perception’, namely, ‘the question of whether we can ever directly perceive the physical world’ (Smith, 2002, p.1). As standardly conceived today (review: Crane & French, 2021), this question is motivated by two parallel arguments: The ‘argument from illusion’ proceeds from the assumption that ‘illusions’ (non-veridical perceptions) are possible: objects may, e.g., look a different size, shape, or colour than they are. (In fact, this happens often.) The ‘argument from hallucination’ proceeds from the equally uncontroversial assumptions that ‘perfect hallucinations’ are possible: people may have hallucinations that are subjectively indistinguishable from ordinary visual experiences. Both arguments lead to the conclusion that, in sense-perception, we are directly aware of subjective sense-data rather than any physical objects they may be caused by or represent (Indirect Realism). These arguments threaten the ordinary or common-sense conception of our senses as providing direct access to physical objects (Direct Realism) and thus lead to the problem of interest: ‘The problem of perception is that if illusions and hallucinations are possible, then perception, as we ordinarily understand it, is impossible’ (Crane & French, 2021, § 2, emphasis added).

Philosophers of perception (often implicitly) equate common-sense beliefs about perception with the stable beliefs of scientifically untrained adults (e.g., Snowdon, 1990, p.176), and take them to be widely, or even universally, shared (e.g., 1777/1975, p.151; Lewis, 1997, p.325; Strawson 1959, p.10). The standard conception of the problem of perception thus relies on two philosophically popular empirical assumptions:

-

(P1)

There is such a thing as ‘the’ ordinary conception of sense-perception: All or most laypeople (scientifically untrained adults) have one single, coherent conception of sense-perception or, at any rate, one such conception or folk theory of each individual sense: vision, hearing, etc.

-

(P2)

This conception or folk theory is consistent with Direct Realism and inconsistent with Indirect Realism.

The problem thus presents itself as an apparent conflict within our common-sense beliefs, namely, between our common-sense conception of vision, etc., and common-sense acceptance of the possibility of illusions and hallucinations. Such a ‘puzzle’ admits of three kinds of responses: reconciliatory explanation (showing that, and explaining why, the conflict is merely apparent), belief revision (modifying some of the conflicting common-sense beliefs), and diagnostic analysis (exposing mistakes in the arguments that appear to bring out the conflict). These responses are sometimes combined: common-sense beliefs are slightly modified, some steps in the underlying arguments are criticized, and a philosophical theory is constructed to reconcile the (modified, or remaining) common-sense beliefs with as much of the underlying arguments as stood up to criticism. Such reconciliation is the typical brief of philosophical theories of the ‘nature of perception’ or, more specifically, of the ‘nature of perceptual experience’ (see Crane & French, 2021, for a review).

Austin does not construct or endorse any philosophical theory, but contents himself with exposing fallacies in the arguments that develop the problem:

‘What we have above all to do is, negatively, to rid ourselves of such illusions as ‘the argument from illusion’… It is a matter of unpicking, one by one, a mass of seductive (mainly verbal) fallacies, of exposing a wide variety of concealed motives – an operation which leaves us, in a sense, just where we began. In a sense – but actually we may hope to learn something positive in the way of a technique for dissolving philosophical worries (some kinds of philosophical worry, not the whole of philosophy)’ (Austin, 1962, pp.4–5).

On a charitable and productive interpretation, this purely diagnostic approach seeks to expose ‘motives’ that are ‘concealed’ not (dishonestly) by the proponents of the relevant arguments, but from them (Fischer, 2014). In more recent terms, the fallacious (mainly verbal) inferences targeted are automatic, i.e., they operate with low demands on attention and working memory, largely beyond conscious awareness (Bargh et al., 2012; Diksterhuis, 2010). Thinkers have no privileged first-person access to such inferences. They can be documented only experimentally. Thus interpreted, the Austinian approach relies on an empirical assumption. In first approximation:

-

(A1)

Philosophers make fallacious automatic inferences in verbal reasoning, including philosophical argument.

Diagnostic findings can be used to address the relevant ‘philosophical worries’: They can potentially show that the philosophical question of ‘whether we can ever directly perceive the physical world’ is ill-motivated to the extent that it was motivated by the arguments that are now shown to be unsound. This would imply that, at any rate for extant proponents of the question, the question that articulates the problem of perception is a bad question to ask. Similarly, diagnostic findings can potentially show simultaneously that the apparent conflict between common-sense acceptance of the possibility of illusions and hallucinations and any common-sense conception of vision consistent with Direct Realism is an artefact of fallacious reasoning and merely apparent: the impression of a conflict is as unwarranted as the question it motivates. This would imply that the problem of perception, as standardly conceived, is an artefact of fallacious reasoning. In this sense, diagnostic findings can potentially ‘dissolve’ the problem and expose it as a ‘pseudo-problem’.

Austin aims for such purely diagnostic dissolution of the problem and is not interested in philosophical theorising that would try to understand how sense-perception works, what perceptual experience is like, and why it is that way – the usual aims of philosophical theorising about perceptual experience (Logue & Richardson, 2021). This ‘quietism’ is motivated by the background assumption that we can remain content with common sense, unless it is successfully challenged:

(A2) The folk conception of sense perception (or vision, etc.) enjoys epistemic default status.

Once diagnostic analysis of such arguments has rebutted such challenges, traditional conceptions of critical OLP suggest, no further philosophical response is required (Fischer, 2014). As invoked in this dialectic, A2 is a normative principle, rather than an empirical claim about the epistemic status a certain community – rightly or wrongly – accords to a certain conception. However, the acceptance of this principle is clearly predicated on the empirical assumption that there is such a thing as a dominant, coherent folk conception of vision that could be given such a status – i.e., P1 above.

In contrast with the quietism it may motivate, A2 has been endorsed not only by Austin (1957/1979, p.185) but is widely accepted in debates about the nature of perceptual experience, along with P1 and P2: Direct Realists have regarded, e.g., common-sense beliefs about vision as part of the ‘massive central core of human thinking which has no history’ (Strawson, 1959, p.10), and therefore as practically impossible to relinquish (e.g., Allen, 2020; Strawson, 1979). These common-sense beliefs are also taken to reflect the phenomenology of visual experience, conceptualised as a readily available form of observational evidence (e.g., Genone, 2016; Martin, 2002; Nudds, 2009; Tye, 2000). Even Indirect Realists who take themselves to oppose common sense often accord it epistemic default status: They accept the need for an error theory that explains why common sense goes wrong (e.g., Russell, 1912; Boghossian & Velleman, 1989), or defend their theories through reference to supposedly key insights of common sense to which they hold on (e.g., Moore, 1957, p.134; Price, 1932, p.63; Robinson, 1994, pp.31–58).

Austin disagrees with these philosophers in believing that the common-sense conception of, say, vision, is not captured by Direct Realism, but is far more ‘diverse and complicated’ than acknowledged by this philosophical doctrine which is ‘no less scholastic and erroneous than its antithesis’ (Austin, 1962, pp.3–4). He is thus critical of P2, while relying on P1.

In a nutshell: Debates about the nature of perception typically rely on P1, P2, and A2. By contrast, Austin’s purely diagnostic approach relies on P1, A1, and A2. According to the Austinian model of critical OLP,Footnote 6 common sense provides a diverse and complicated but coherent conception of the phenomenon of interest (say, vision) (cf. P1). We should accept this conception in the absence of successful challenges (cf. A2). Antinomic puzzles (like the problem of perception) arise from philosophical arguments that appear to refute key aspects of this common-sense conception, and appear to bring out conflicts within this conception. Where the relevant arguments are defective, the puzzles can be dissolved by exposing (mainly verbal) fallacies in them, in particular at the level of automatic inferences (cf. A1).

3 Fallacious automatic inferences in philosophical argument

Critical OLP in the wake of Austin (1962) assumes that (A1) philosophers make fallacious automatic inferences in verbal reasoning, including philosophical argument. To develop this assumption, we draw on psycholinguistics. We now consider inferences of interest (Sect. 3.1) and philosophical arguments of interest (Sect. 3.2), and bring out the need of A1, and the critical OLP approach relying on this assumption, for empirical support (ibid.). In search of such support, we then consider empirical work examining the hypothesis that the – fallacious – inferences discussed drive the arguments considered (Sect. 3.3–3.5). Section 4 will turn to the remaining three assumptions (A2, P1, P2).

3.1 Inferences of interest

When we read, hear, or utter words, they trigger automatic inferences. Some of these inferences are triggered regardless of context or outside all context. These ‘default inferences’ are supported by concepts, in cognitive science’s sense of the term (review: Machery, 2009): bodies of information stored in long-term memory, which are deployed in the exercise of higher cognitive competencies including language comprehension, perceptual categorization, and inductive learning, and are retrieved by default. That is, they are rapidly retrieved (e.g., in response to a verbal stimulus), in every context (e.g., any sentence containing the word) or outside all context (as in single word priming experiments), by an automatic process (Bargh et al., 2012).

Concepts include ‘stereotypes’, namely, prototypes associated with nouns (Rosch, 1975; Hampton, 2006) and schemas associated with verbs (Rumelhart, 1978; McRae et al., 1997). Unlike definable concepts associated with necessary and sufficient conditions, these implicit knowledge structures encode statistical information about regularities that are observed in the physical or discourse environment (McRae & Jones, 2013). They represent bodies of empirical ‘world knowledge’ that get rapidly deployed in language processing (Elman, 2009): As traditionally conceived, prototypes represent clusters of weighted features that immediately come to mind when we encounter those words and are typical for, or diagnostic of the relevant categories (e.g., tomatoes typically are red, and if an animal carries malaria it is more likely a mosquito than anything else) (Hampton, 2006). Similarly, schemas encode information about typical features of events or actions, agents, ‘patients’ acted on, and typical relations between them (Ferretti et al., 2001; Hare et al., 2009; McRae et al., 1997). Dependency networks in complex schemas encode causal, functional, and nomological information (Sloman et al., 1998). As shown by priming experiments (review: Lucas 2000), single words (like ‘tomato’) activate the associated stereotype with its several component features (like red), and do so rapidly (within 250ms) (review: Engelhardt & Ferreira, 2016). In other words, the verbal stimulus rapidly makes the stereotypical information more accessible and likely to be used by cognitive processes. In reading comprehension, for example, these processes range from word recognition to the construction of the situation model, i.e., the mental representation of the situation described by the text, which provides the basis for further judgements and reasoning about that situation (Kintsch, 1988; Zwaan, 2016).

In addition to stereotypes associated with individual words, we have schemas which encode more specific knowledge about recurrent situations (car inspections, restaurant visits, etc.). These are rapidly activated by combinations of nouns and verbs (‘The mechanic checked…’) even when activated by neither word on its own (Bicknell et al., 2010; Matsuki et al., 2011); they influence sentence processing from the earliest possible moment (e.g., at the verb, readers come to expect that the object checked will be a part of a car, rather than, say, the spelling of a report).

These stereotypes are the prefab building blocks of information from which we construct our interpretations of texts and utterances. Activated stereotypes support defeasible automatic inferences about what (else) is (also) true of the situation talked about (e.g., unless indicated otherwise, the ‘tomato’ will be red, the ‘mosquito’ will carry malaria, and the ‘mechanic will check’ a car). These stereotypical inferences are instrumental in facilitating effective communication in the face of the ‘articulation bottleneck’ (Levinson, 2000, p.28) that arises as normal speech conveys information at a rate that is 3–4 times slower than pre-articulation processes in speech production (Wheeldon & Levelt, 1995) and parsing processes and comprehension inferences (Mehler et al., 1993). Default inferences that deploy our statistical knowledge about the world allow hearers to rapidly fill in detail. Anticipating such inferences allows speakers to skip mention of typical features and use fewer words.

In a neo-Gricean framework (Horn, 2004, 2012; Levinson, 2000; Recanati, 2004), these stereotypical inferences have been conceptualised as pragmatic inferences with the I-heuristic (‘What is expressed simply is stereotypically exemplified’, Levinson 2000, p.37). The heuristic tells hearers to deploy stereotypes and tells speakers to anticipate their use, in order to devise or facilitate interpretations that are positive, stereotypical, and highly specific (pp.114–115):

I-speakerSkip mention of stereotypical features but make deviations from stereotypes explicit.

I-hearerAbsent such explicit indications to the contrary, assume that the situation talked about conforms to the relevant stereotypes and deploy the most specific stereotypes relevant, to fill in detail in line with this knowledge about situations of the kind at issue.

Pragmatic inferences with the I-heuristic are the ubiquitous humble servants of communication: They are made continuously in language comprehension and provide the raw informational materials for utterance interpretation. At the same time, these defeasible inferences are at the bottom of the pragmatic pecking order and can be defeated by conflicting inferences with other heuristics (Levinson, 2000, pp.157–158) and by contextual information. Successful utterance interpretation requires combining and cutting down to size the automatically activated blocks of stereotypical information, in constructing the situation model (Kintsch, 1988; Zwaan, 2016): It requires integrating default information activated by individual words with further world knowledge activated only by combinations of words (Bicknell et al., 2010; Matsuki et al., 2011), in the sentence or wider discourse context (Metusalem et al., 2012), and suppressing from the situation model the conclusions of stereotypical inferences that are contextually irrelevant (e.g., in talk about unripe tomatoes) (Faust & Gernsbacher, 1996).

Much of Austin’s Sense and Sensibilia discusses stereotypical inferences from words which have subtle contextual defeaters. Without the benefit of the conceptual apparatus available today, Austin sought to clarify ‘the root ideas behind the uses of’, e.g., appearance verbs ‘look’, ‘appear’, and ‘seem’ employed in the initial premises of the argument from illusion (Austin, 1962, pp.36–37). He goes on to stress the radical context-sensitivity of inferences made or anticipated in language-comprehension and -production:

‘If I say that petrol looks like water, I am simply commenting on the way petrol looks; I am under no temptation to think, nor do I imply, that perhaps petrol is water. […] But ‘This looks like water’ … may be a different matter; if I don’t already know what ‘this’ is, I may be taking the fact that it looks like water as a ground for thinking it is water’ (Austin, 1962, pp.40–41).

Therefore, ‘just what is meant and what can be inferred (if anything) can be decided only by examining the full circumstances in which the words are used’ (p.41): Under some circumstances, ‘X looks F (to S)’ may prompt and warrant an inference to a belief attribution (a doxastic inference) like S thinks that X is F. Other circumstances may defeat doxastic inferences from any of those verbs.

Austin’s crucial implicit suggestion is that philosophers often fail to pay due attention to the full circumstances in which words are used and make defeasible inferences supported by the root idea associated with them, also in contexts that defeat those inferences. What Austin called the ‘root idea’ is best regarded as the stereotype associated with the word. He is best understood as concerned with default inferences supported by such stereotypes. More fully developed, his assumption is that

(A1) Philosophers make contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences from words and presuppose their conclusions in philosophical arguments, despite contextual defeat.

We now identify words and arguments of interest.

3.2 Arguments of interest

Building on Austin’s (1962) discussion of the problem of perception, Eugen Fischer and colleagues have developed reconstructions of the underlying arguments that identify contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences from phenomenal uses of appearance- and perception-verbs, respectively, in the opening moves of the arguments from illusion (Fischer, 2014; Fischer et al., 2021) and from hallucination (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2020; Fischer & Herbelot, in press). We focus on the latter, which requires less stage setting (and was not discussed in any detail by Austin).

In a classic statement of the argument from hallucination, A.J. Ayer – whose earlier work was the chief target of Austin’s criticism – carefully distinguishes between two senses of the verb ‘to see’: In its perceptual sense, the verb is factive and has spatial implications (When S ‘sees’ X, X is around to be seen by X, typically in front of X); in its phenomenal sense, the verb serves purely to describe the viewer’s subjective experience and lacks all factive (epistemic, spatial, etc.) implications. Ayer then states the argument’ first half as follows:

‘Let us take as an example Macbeth’s visionary dagger […] There is an obvious [perceptual] sense in which Macbeth did not see the dagger; he did not see the dagger for the sufficient reason that there was no dagger there for him to see. There is another [viz., phenomenal] sense, however, in which it may quite properly be said that he did see a dagger; to say that he saw a dagger is quite a natural way of describing his experience. But still not a real dagger; not a physical object… If we are to say that he saw anything, it must have been something that was accessible to him alone… a sense-datum.’ (Ayer, 1956, p.90, highlighting added).

The argument’s second half then generalises from this special case to all cases of visual perception. Different versions do so in different ways which need not concern us here.

The argument is commonly intended as a deductive argument. The following reconstruction (which expands on that offered by Fischer & Engelhardt, 2020, pp.432–433) remains as close to the text as possible and builds a deductive argument from the bits in bold above:

-

(1)

‘There was no [real] dagger there.’

-

(2)

‘Macbeth did see a dagger.’

To deductively infer that Macbeth did not see a real dagger (‘But still not a real dagger’), we need an implicit assumption:

-

(3)

If Macbeth saw a real dagger, there was a real dagger there. By (1) & [3] with modus tollens:

-

(4)

‘Macbeth did not see a real dagger.’

-

(5)

Macbeth did not see any other physical object. By (4) & [5]:

-

(6)

‘Macbeth did not see a physical object.’ Hence:

-

(7)

‘If Macbeth saw any object, he saw a non-physical object (“sense-datum”).’ By (7) & (2):

-

(8)

‘Macbeth saw a sense-datum.’

This reconstruction posits a fallacy of equivocation: The implicit assumption [3] uses ‘see’ in the perceptual sense that has spatial implications – if S sees an F (say, a dagger), then an F (a dagger) is there. Hence the conclusions derived from it, directly or indirectly, need to use the verb in the same perceptual sense (underlined above). This includes (7). But Ayer then derives the crucial conclusion from (7) and (2) – even though (2) explicitly uses the verb in the phenomenal sense (highlighted in bold) that lacks spatial implications. Pace (3), that Macbeth ‘saw’ a real dagger in this sense does not imply there was a real dagger. To clarify: In the phenomenal sense, ‘S sees an F’ means ‘S has an experience like that of seeing an F’. Macbeth is meant to have an experience just like that of seeing a physical dagger. In the phenomenal sense, he can therefore be said to ‘see a physical dagger’, because that is exactly what his experience is like. In this phenomenal sense, he cannot be said, e.g., to see a translucent non-physical dagger (his experience is not like that). In Ayer’s text, the move from ‘Macbeth saw a dagger’ (in the phenomenal sense) to ‘but still not a real dagger’ is hence fallacious.

The posited inference from the phenomenal use of ‘S sees X’ to the conclusion that there was an X there (around S) to be seen is a contextually inappropriate stereotypical inference of the kind the Austinian assumption A1 adverts to: ‘See’ is associated with a situation schema that includes the typical agent features S looks at X, S knows X is there, and S knows what X is, and the typical agent-patient relations X is in front of S and X is near S that support the automatic inference of interest. The inference is contextually inappropriate in the light of the previous explanation of the relevant phenomenal sense of the verb, and is explicitly cancelled by the prior contextual information that ‘there was no dagger there for him to see’.

This example forcefully illustrates A1’s need for empirical support: The interpretation of philosophical texts is governed by widely accepted principles of charity. These principles tell us to credit authors with linguistic competence and rationality. This requirement creates a tension with the attribution of fallacies (Adler, 1994; Lewinski, 1997). This tension is glaring, in the present case: Ayer explains the two relevant senses of perception verbs, before setting out the argument, and explicitly flags their uses, in the argument. The present reconstruction suggests he made an inference from the phenomenal use that is licensed only by the perceptual sense, and thus violated his own explanation of the phenomenal sense within a few lines of providing it. Why should a competent thinker do that? Does the attribution of such an egregious fallacy to a competent philosopher not simply show that the interpretation of their text is wrong (e.g., that the gaps in the stated argument need to be filled in differently)? Medium-strength principles of charity resolve the tension by allowing interpreters to attribute fallacies to authors, but only if the attribution is backed up by an empirically supported answer to the first question, i.e., by an empirically supported account of when and why even competent thinkers commit fallacies of the relevant kind (Thagard & Nisbett, 1983). While fitting the text, the present reconstruction is in need of such empirical support.

In line with the focus of critical OLP, Fischer and Engelhardt (2020) suggested that the present fallacy of equivocation is the manifestation of a contextually inappropriate stereotypical inference (namely, a spatial inference from the phenomenal use of ‘see’). Such inferences are automatic, and hence can only be documented experimentally. Moreover, we still need an explanation of when and why competent thinkers make the inferences at issue (e.g., spatial inferences from phenomenal uses of ‘see’). Competent language users are generally swift and effective at contextualising such default inferences (Bicknell et al., 2010; Kim, Oines, and Sikos, 2016; Matsuki et al., 2011). So why should they make the inappropriate inferences that amount to the fallacy of equivocation? The example from Ayer thus forcefully illustrates how the kind of diagnostic analyses that are at the heart of the critical OLP approach need support from successful empirical explanations of the specific fallacies of interest.

3.3 Empirical foundations: Linguistic salience bias

The most extensive experimental implementation of critical OLP to date seeks to explain contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences by reference to comprehension biases that affect automatic language processing. To assess explanations, it has adapted eye-tracking methods from psycholinguistics. These efforts have so far led to the discovery of the linguistic salience bias that may account for the bad inferences from appearance- and perception-verbs posited in arguments from illusion and from hallucination. These efforts have also demonstrated how prevalent the specific fallacies of interest are, among philosophers and laypeople alike, despite people’s ability to contextualise default inferences in general. We now explain the bias that might account for these specific fallacies (Sect. 3.3), present relevant psycholinguistic methods (Sect. 3.4), and review the studies that have employed these methods to provide evidence of the bias and the inferences of interest (Sect. 3.5).

The linguistic salience bias affects the processing of words with several distinct but related senses (polysemes). These words account for at least 40% of words in English (Byrd et al., 1987) and include the verbs of interest. The bias leads people to go along with stereotypical inferences from subordinate uses of polysemous words, which are supported only by the words’ dominant sense (Fischer & Sytsma, 2021). The bias arises as follows.

In general, polysemes activate a unitary representation of semantic information that is then deployed to interpret utterances which use the word in different senses (Macgregor, Bouwsema, & Klepousniotou, 2015; Pylkkänen, Llinás, & Murphy, 2006). So there are not independent representations for each sense, but one representation from which different information is extracted and deployed for interpretation, when the word is used in different senses. This unitary representation consists in overlapping clusters of semantic features (Brocher et al., 2016; Klepousniotou et al., 2012). Different components of these unitary representations get activated in different strength by the verbal stimulus (Brocher et al., 2018): The more often the language user encounters the word in one sense, rather than another, the more strongly the features associated with that sense are activated, upon the next encounter. Another factor influencing strength of activation is prototypicality: Features deemed to make for particularly good examples of the relevant category (say, ‘seeing’) are activated more rapidly and strongly (Hampton, 2006). Strength of activation thus depends on the ‘linguistic salience’ of the sense at issue: Unlike the contextual salience involved in familiar salience biases (see Taylor & Fiske, 1978, for a classical review), this is not a contextual magnitude, but a function of relative exposure frequency over time (how often the word is encountered in this sense, rather than another), modulated by prototypicality (i.e., how good examples of the relevant category the word is deemed to stand for in that sense) (cf. Giora, 2003).

Interpreting any particular use of a polysemous word then requires activating all contextually relevant features, and suppressing all contextually irrelevant, but activated features. Consider a simple case where the features relevant for interpreting a subordinate use are a subset of the features that make up the stereotype associated with the dominant sense: As noted above, the verb “to see” is associated with a situation schema that includes the typical agent features S looks at X, S knows X is there, S knows what X is and the typical agent-patient relations X is in front of S and X is near S. All these features get activated by the verbal stimulus. To interpret the purely epistemic use illustrated by “Jack saw Jane’s point”, precisely the last two agent features are relevant: Jack knows there is a point of Jane’s and he knows what it is. These features need to be retained, while the other initially activated features need to be suppressed. This is known as the Retention/Suppression strategy (Giora, 2003), which is often used in processing irregular polysemes (i.e., metaphorical uses, as opposed to regular polysemes whose uses can be interpreted by drawing on rules, e.g., of metonymy).

This strategy runs into difficulties in the face of marked imbalances in linguistic salience: Suppose features irrelevant for the subordinate sense are associated with the clearly dominant sense. Then these irrelevant features will receive strong initial activation due to salience (Brocher et al., 2018). Second, frequently co-instantiated features exchange lateral co-activation (Dresang et al., 2021; Hare et al., 2009; McRae et al., 2005). This of course also applies to features associated with the dominant sense. Where only some, but not all of them are relevant for a subordinate use (as is the case where the Retention/Suppression strategy is used), the contextually relevant features will continue to pass on activation to the contextually irrelevant features. Therefore strong initial activation of contextually irrelevant features is followed by their continued cross-activation. This prevents their selective suppression. Merely partially suppressed features continue to support stereotypical inferences.

This difficulty about selective suppression creates a linguistic salience bias (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2020; Fischer & Sytsma, 2021): When

-

i.

one sense of a polysemous word is much more salient than all others, and

-

ii.

the Retention/Suppression strategy is used to interpret utterances with a subordinate use,

then

-

1.

contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences supported by the dominant sense will be triggered by the subordinate use as well, and

-

2.

these automatic inferences will influence further judgment and reasoning.

In a nutshell: Thinkers are then swept along by defeasible inferences, even when these are defeated by the context.

This bias predicts, e.g., that, while competent speakers readily recognise and employ phenomenal uses of perception verbs which lack all epistemic and spatial implications (Sant’Anna & Dranseika, 2022), such rarefied uses will trigger persistent epistemic and spatial inferences that are supported only by the verbs’ dominant senses. The bias could thus explain, e.g., the bad inferences diagnostic reconstructions have posited in the argument from hallucination (Sect. 3.2).

3.4 Eye tracking methods

To study automatic comprehension inferences, psycholinguists have developed the cancellation paradigm. In this paradigm, participants read or hear sentences where the expression of interest is followed by text that ‘cancels’ or defeats the inference that is hypothesised to be triggered by that expression. To examine, e.g., whether ‘S sees X’ triggers automatic inferences to X is in front of S, we can ask participants to read or listen to sentences like:

-

(1)

‘Sheryl sees the pictures on the wall behind her.’ (s-inconsistent).

-

(2)

‘Carol sees the pictures on the wall facing her.’ (s-consistent).

If the stereotypical inference is triggered, its conclusion will clash with the sequel, in stereotype-inconsistent (‘s-inconsistent’) items like (1) but not in stereotype-consistent items like (2). Such clashes cause comprehension difficulties which lead participants to expend cognitive effort. When this happens, people’s pupils dilate (Kahneman, 1973; Laeng et al., 2012), they need longer to read the cancellation phrase (e.g., ‘behind her’) (Harmon-Vukic et al., 2009), and make more backwards eye movements from that phrase (Patson & Warren, 2010).

The most fine-grained measures are provided by reading times. In reading, our eyes move in stops and starts: they skip the contextually most predictable words and move backwards at points of difficulty, so that many words get fixated repeatedly. Difficulties at different stages of text comprehension then manifest themselves in different eye-tracking measures (Clifton et al., 2016; Rayner et al., 2004). Difficulties in word recognition depend on the word’s frequency, length, and predictability in local context. These jointly determine the first-pass fixation time for the word. By contrast, difficulties in integrating local interpretations of a few adjacent words into comprehensive interpretations of an entire sentence show in late measures: They lead to more backwards eye movements to earlier text and to longer re-reading and total reading times. In the cancellation paradigm, inferences from the verb phrase lead to integration difficulties in stereotype-inconsistent items (like 1). These will show up through longer re-reading times for conflict regions (‘behind her’) or for the source regions from which problematic inferences originate (e.g., the verb phrase).

The linguistic salience bias hypothesis predicts contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences from subordinate uses of polysemous words – e.g., from subordinate uses of the verb ‘to see’. To test this hypothesis, experimental materials need to render a subordinate interpretation contextually relevant. In the present example, an abstract noun can be used to invite a purely epistemic reading of the verb:

-

(3)

Jack sees the problems that lie behind him.

-

(4)

Joe sees the problems that lie ahead of him.

For such items, the dictionary-attested purely epistemic sense of ‘see’ (‘know/understand something’) and familiar spatial time metaphors (whereby ahead = in the future; behind = in the past) facilitate purely metaphorical interpretations tantamount to, respectively:

-

(3’)

Jack knows what problems he had in the past.

-

(4’)

Joe knows what problems he will have in the future.

The space–time metaphors employed here give rise to embodied cognition effects (Boroditsky & Ramscar, 2002; Bottini et al., 2015) and support spatial reasoning about temporal relations (Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008; Gentner et al., 2002). If spatial inferences from ‘S sees X’ to X is in front of S persist (i.e., are not suppressed at the disambiguating object ‘problem’), they will prevent purely metaphorical interpretation also of the space-time metaphors, engage spatial reasoning, and create the impression of a conflict in s-inconsistent ‘see’-items that place problems etc. metaphorically ‘behind’ agents. The resulting integration difficulties predict longer re-reading times for conflict regions (‘behind him’) in s-inconsistent items (like 3) than for the corresponding region (‘ahead of him’) in s-consistent items (like 4), controlled for length and word frequency.

Stereotypical inferences that clash with background beliefs or contextual information can be suppressed within one second (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2017b) – and then fail to affect further cognition. To measure inferences’ influence on further cognition, one can combine eye-tracking measures with subsequent plausibility ratings. To stick to our example: In studying inferences from purely epistemic uses of ‘see’, Fischer and Engelhardt (2020) conducted a norming study where participants rated the plausibility of explicit knowledge claims that ‘cash out’ the purely metaphorical interpretation of epistemic items. Unsurprisingly, participants found past-directed sentences (like 3’) more plausible than future-directed sentences (like 4’). Persistent spatial inferences from ‘see’ that place the object before the viewer predict the opposite pattern as in the norming study: Even though they mean the same as the past-directed items in the norming study, s-inconsistent epistemic ‘see’-sentences (like 3) will be deemed less (rather than more) plausible than s-consistent ‘see’-sentences (like 4) that mean the same as the future-directed items.

To establish that processing and plausibility differences arise from inferences from the verb, we can finally manipulate the verb, and exchange the verb of interest for a contrast verb that does not give rise to the conflict-generating inferences, or does not do so as persistently (e.g., ‘see’ vs. ‘be aware of’). This manipulation complements, e.g., items like (1)-(4) with items including:

-

(3*)

Jack is aware of the problems that lie behind him.

-

(4*)

Joe is aware of the problems that lie ahead of him.

On the intended purely metaphorical interpretation (made explicit by 3’ and 4’), (3*) and (4*) mean the same as the ‘see’-items (3) and (4), respectively. To the extent to which contextually inappropriate but persistent spatial inferences are made from ‘see’, but not ‘aware’, and influence further judgment, s-inconsistent ‘see’-items (like 3) will, all the same, be deemed less plausible than ‘aware’-counterparts (like 3*). This makes this ‘see’-‘aware’ comparison a good measure of linguistic salience bias (Fischer et al., 2022).

3.5 Extant studies

About ten studies to date have used the cancellation paradigm to (1) investigate the linguistic salience bias hypothesis and (2) provide direct and indirect evidence of contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences that result from this bias and have been suggested to drive the arguments from illusion and hallucination (see Sect. 3.2).

Five studies have used the cancellation paradigm to investigate the linguistic salience bias hypothesis by examining spatial inferences from purely epistemic uses of ‘see’. These studies used plausibility rankings and ratings (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2017a; Fischer, Engelhardt, & Herbelot, 2022) and combined plausibility ratings with pupillometry (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2017b, 2020) or fixation time measurements (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2019). Four studies have provided evidence of the bias by examining doxastic inferences from purely phenomenal uses of appearance verbs (cf. Brogaard, 2013, 2014); they used plausibility rankings (Fischer & Engelhardt, 2016; Fischer et al. 2021), or combined plausibility ratings with fixation time measurements (Fischer, Engelhardt, & Sytsma, 2021; Fischer & Engelhardt, in press). Another study provided evidence of linguistic salience bias by documenting framing effects in judgments about philosophical ‘zombies’ (vs. ‘duplicates’) (Fischer & Sytsma, 2021). All studies were preceded by corpus analyses, including distributional semantic analyses, to assess the occurrence frequencies of different senses of the words of interest. Together with production experiments that assessed the senses’ prototypicality, i.e., the other determinant of linguistic salience, these analyses provided evidence of pronounced differences in linguistic salience between dominant and subordinate senses of the words of interest. Eye tracking studies examined inferences in both listening and reading comprehension: In the pupillometry studies, participants heard the items. In the fixation time studies, participants read items on a screen. In all studies, participants rated the plausibility of items right after encountering them.

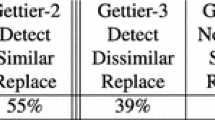

All studies confirmed the predictions from the linguistic salience bias hypothesis. For instance, in the studies on spatial inferences from purely epistemic uses of perception verbs, the effect of the verb manipulation (‘see’ vs. ‘aware of’) on plausibility ratings is a good measure of the bias (see above). The four studies that elicited plausibility ratings observed medium-to-large effects for this key comparison (see Table 1).

The studies reviewed invoke linguistic salience bias to expose and explain contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences in philosophical arguments. To justify this approach, further findings are required: First, since professional analytic philosophers can plausibly be expected to be more careful and proficient than laypeople in distinguishing between different senses and reasoning with polysemous word, it has to be shown that such philosophers are no less susceptible to the linguistic salience bias than the convenience samples (psychology undergraduates) used in previous eye tracking studies. Initial evidence to this effect has been provided by a plausibility rating study examining spatial inferences from purely epistemic uses of perception-verbs (Fischer et al., 2022, see Table 1).

Second, it has to be shown that inappropriate inferences persist also when they are rendered inappropriate (‘cancelled’) already by pre-verbal context (as happens in the arguments of interest), rather than only by post-verbal context (as in all the studies reviewed). Initial evidence is provided by a study that combined plausibility ratings with fixation time measurements to examine inferences from phenomenal uses of appearance verbs to attributions of beliefs to viewers (which Fischer et al., 2021, posited to be at the root of arguments from illusion). Fischer and Engelhardt (in press) found evidence such inferences are triggered and persist also where pre-verbal contexts specify situations that norming study participants regarded as familiar situations of non-veridical perception (in which the viewer will be unlikely to believe that things are as they appear). This suggests linguistic salience bias is powerful: In its grip, thinkers are swept along by defeasible inferences, even when these are defeated by the context that immediately precedes the ‘trigger words’.

3.6 Summary

The Austinian model of critical OLP relies on two key assumptions: A1 and A2. To repeat for convenience, Austin assumes that philosophical arguments rely on fallacious automatic inferences and moots, more specifically, the idea that:

-

(A1)

Philosophers make contextually inappropriate stereotypical inferences from words and presuppose their conclusions in philosophical arguments, despite contextual defeat.

This assumption needs empirical support: It calls for an empirical account that explains when and why even competent thinkers commit the fallacies in question. Extant experimental implementations of critical OLP have drawn on methods and findings from psycholinguistics to examine A1. They explain relevant inferences by reference to biases that affect automatic language comprehension and production processes. They provide evidence of a pertinent bias, the linguistic salience bias, and of contextually defeated but persistent stereotypical inferences from appearance- and perception-verbs that are explained by the bias and may drive arguments from illusion and from hallucination. In brief, findings to date support A1. We now turn to A2.

4 Assessing further empirical assumptions

4.1 Common sense as epistemic default?

Antinomic puzzles are developed by arguments that challenge common sense. The arguments from illusion and from hallucination motivate the problem of perception by appearing to challenge the common-sense conception of vision. Austin’s purely diagnostic approach addresses the problem by exposing fallacies in the underlying arguments. Austin suggests that nothing more than this defence of common sense is required to address the philosophical problem. This idiosyncratic quietism relies on the assumption:

-

(A2)

The folk conception of vision enjoys epistemic default status. (We should accept common sense about perception unless it is successfully challenged.)

While general ‘default-and-challenge’ models of justification that build on Austinian ideas (e.g., Brandom, 1994; Williams, 2001) have been deeply unpopular in epistemology, the more specific assumption A2 is common in debates about the nature of perception (see Sect. 2) – as are analogous assumptions in debates revolving around structurally similar antinomic puzzles (review: Fischer, 2011). As commonly interpreted, A2 relies on an empirical assumption:

-

(P1)

All, or most, scientifically uninstructed adults share a single, coherent conception of vision.

Recent psychological and philosophical work on belief (review: Porot & Mandelbaum, 2021) suggests we cannot simply take for granted the existence of unified and coherent common-sense conceptions of familiar phenomena like vision: Folk beliefs are often ‘fragmented’ and conflicted. Different cognitive processes, operating under different conditions, generate conflicting beliefs, which are stored at different locations in long-term memory, in different ‘belief fragments’. Due to limitations of working memory (review: Oberauer et al., 2016), these fragments are never systematically screened for coherence and may conflict with one another (Bendaña & Mandelbaum, 2021; Leiser, 2001). As a result, different conceptions of the same phenomenon may be harboured not only by different members of the same community but even by one and the same individual.

Research on naïve theories (review: Shtulman, 2017) provides evidence of such fragmentation and suggests that conflicting beliefs are integrated into durable distinct belief fragments that are updated independently: This research documented persistent conflicts between naïve theories (e.g., impetus theories of motion) and scientific theories (Masson et al., 2014; Shtulman & Valcarcel, 2012) as well as conflicts between naïve theories of death, disease, and God (e.g., conceptualising God as a person), and socially learned conceptions (e.g. theologically sanctioned transpersonal conceptions of God) (Barlev et al., 2017; Legare et al., 2012; Watson-Jones et al., 2017). In some cases, most scientifically instructed adults explicitly reject the naïve theory, but need to effortfully suppress it to prevent it from influencing their responses (Shtulman & Valcarcel, 2012), suggesting conflicts between explicit and implicit beliefs. Other findings suggest conflicts between explicit beliefs, as when people explicitly invoke different beliefs (e.g., about death) in different contexts (e.g., Church vs. hospital) (Astuti & Harris, 2008), and contextual cues influence to what extent their explanations of phenomena are coherent (Watson-Jones et al., 2017).

Laypeople’s beliefs about vision are fragmented in ways that result in clashes among explicit beliefs or between explicit and implicit beliefs. First evidence has been provided by inter- and intrapersonal conflicts between extramissionist beliefs (according to which visual perception involves force rays leaving our eyes) and intromissionist beliefs (according to which vision involves light rays coming into our eyes) (review: Winer et al., 2002). Many children and adults who explicitly endorse extramissionist beliefs simultaneously agree with intromissionist beliefs (Cottrell & Winer, 1994), and many adults combine explicit belief in intromissionism with implicit belief in extramissionism (Guterstam et al., 2019). These naïve beliefs are neither transient nor idle: Once acquired, extramissionist beliefs are resistant to counter-instruction (Gregg et al., 2001) and are recruited to explain vision – when asked, most participants endorsing them take extramission to be functional for vision (Winer et al., 1996; cf. Guterstam et al. 2019, p.330).

Extending this research, a recent study examined Indirect Realist beliefs about vision (when viewing [e.g.] an apple, we see a mental image of the apple, caused by that apple) and Direct Realist beliefs that reject them (when looking at an apple, we see only the apple and no mental or other image of it) (Fischer, Allen, & Engelhardt, 2023). Agreement ratings and open-text questions elicited inter- and intrapersonal conflicts at the level of explicit beliefs: While over half of lay participants endorsed verbal statements of folk Direct Realism, over 40% endorsed folk Indirect Realism, and about 70% endorsed pictorial illustrations of it. About half of participants explicitly endorsed both positions when these were presented in different stimulus formats, namely, by verbal statements vs. pictures. Depending upon the classification criteria used, between a fifth and a third of participants endorsed both positions even when these were presented in the same stimulus format, namely, verbally. While some participants rejected both positions, only a minority of participants adhered consistently to only one of the two conflicting conceptions. Neither conception was clearly dominant, i.e., maintained much more widely or strongly than the other.

Philosophers of perception often regard Direct Realism as capturing untutored common sense, think Indirect Realism is acquired through philosophical reflection or exposure to science, and accordingly assimilate the conflict between Direct Realism and Indirect Realism to conflicts between naïve and scientific theories (Brewer, 2011; Chalmers, 2006; Crane & French, 2021; Smith, 2002). Against this, Fischer, Allen, and Engelhardt (2003) suggest that folk Indirect Realism articulates a pre-scientific theory of sense-perception embedded in the Cartesian Theatre conception of the mind that is widely shared by laypeople (Forstmann & Burgmer, 2022; cf. Bertossa et al., 2008): Input from the sense-organs is processed in the brain, where it results in a conscious experience that prototypically involves seeing a mental image (in an inner ‘theatre’). This act of inner perception – and only this act – requires input from the sense-organs to come together in a single location, behind the eyes, and requires the conscious experience to be the effect of earlier neural processing (Dennett, 1991). Folk Indirect Realism elaborates this pre-scientific theory without recourse to new, scientific concepts – it rather assimilates the relationship between the subject and the output of cerebral processing to the familiar relationship between a viewer and an object of sight. Folk Indirect Realism is no more scientifically informed than the Cartesian Theatre conception. The conflict between folk Direct Realism and folk Indirect Realism seems to be a conflict between different fragments of pre-scientific beliefs, i.e., within untutored common sense. If so, the findings reviewed speak against P1 and the related assumption P2 that the common-sense conception of vision is consistent with Direct Realism and inconsistent with Indirect Realism.

To sum up, the assumption A2 that the common-sense conception of vision enjoys default epistemic status is predicated on (P1) the existence of a set of folk beliefs about vision that is coherent and (almost) universally accepted or at least clearly dominant. The findings reviewed in this section speak against P1 and suggest that A2 is wrong for the fundamental reason that there is no such thing as ‘the’ common-sense conception of vision. Against another philosophically popular assumption, P2, laypeople appear to be torn between Direct Realist and Indirect Realist beliefs.

4.2 Philosophical consequences

To assess the consequences for critical OLP, we first need to note the consequences for how we should conceive of the problem of perception addressed by Austin’s paradigmatic treatment – and of antinomic puzzles, more generally. On what I will call the reasoning conception of such problems, they are developed by philosophical arguments that suggest the common-sense conception of a phenomenon cannot be true. These arguments draw on uncontroversial folk beliefs that are commonly thought to be consistent with that conception. The arguments then derive a conclusion inconsistent with the common-sense conception. They thus appear to bring out a hidden clash or antinomy in folk belief and motivate the question: ‘How is phenomenon X, as we ordinarily understand it, even possible?’

This conception informs the critical OLP approach that seeks to ‘dissolve’ such problems by showing the underlying arguments are unsound (Sect. 2). It is also the standard conception of the problem of perception: Arguments from illusion and hallucination that infer Indirect Realist conclusions from the possibility of illusions and hallucinations appear to bring out a hidden clash between this uncontroversial possibility and the supposedly Direct Realist folk conception of vision, etc. They thus motivate the problem of how sense-perception, as we ordinarily understand it, is as much as possible, if illusions and hallucinations are possible (Crane & French, 2021, § 2).

On an alternative permanent belief conception of antinomic puzzles, such problems arise prior to reasoning captured by philosophical arguments, namely, from conflicts between comparatively stable pre-reflective folk beliefs about the same phenomenon: e.g., across cultures, laypeople seem to be roughly evenly split between compatibilist and incompatibilist conceptions of free will (Hannikainen et al., 2019; cf. further analysis by Knobe, 2021), and this conflict may be one source of the problem of free will. Similarly, the findings reviewed above suggest that laypeople hold all along two inconsistent conceptions of vision: ‘folk Indirect Realism’ and ‘folk Direct Realism’. If this is correct, the arguments from illusion and hallucination are best seen as ex-post rationalisations of Indirect Realist beliefs which many laypeople hold already prior to all argument. On this view, the conflict between folk Direct Realism and folk Indirect Realism prompts philosophical efforts to justify one over the other by developing arguments that derive conclusions consistent with one conception (Indirect Realism), but not the other (Direct Realism), from further antecedently held folk beliefs that can serve as common ground (e.g., from the beliefs that illusions occur and hallucinations are possible). If sound, these arguments bring out further conflicts, between folk beliefs that were previously regarded as compatible: e.g., between folk Direct Realism and the beliefs that illusions occur and hallucinations are possible.

Which of these two conceptions applies to which antinomic puzzle is an empirical question, to be answered by, among other things, studying folk beliefs about the phenomenon of interest. Crucially, the permanent belief conception implies that the puzzle at issue really involves a series of related belief conflicts: an initial conflict that motivates the construction of arguments that purport to bring out further, previously hidden conflicts. Where this conception applies, a reconceptualization of the problem is required. For instance, if there is no one dominant and coherent folk conception of vision, as laypeople understand vision in terms of both Direct Realism and Indirect Realism, we cannot ask simply how vision, as ordinarily understood, is possible. Rather, we need to ask:

[True problem of perception] How can one of two conflicting folk conceptions of vision be correct or warranted in the light of conflicts with each other and with other folk beliefs about vision (e.g., that illusions occur and hallucinations are possible)?

The reconceptualization of the problem mandated by empirical findings about folk beliefs would seem to seriously limit the relevance of critical OLP’s traditional Austinian approach: Diagnostic analyses that expose fallacies in the arguments from illusion and hallucination could show that the conflicts between folk Direct Realism and folk beliefs about illusions and hallucinations, respectively, are merely apparent. But such diagnostic analyses could not resolve the underlying conflict between folk Direct Realism and folk Indirect Realism, neither of which would enjoy epistemic default status and deserve to be held in the mere absence of successful argumentative challenge. In brief, if the problem is due to belief fragmentation and only exacerbated by fallacious philosophical reasoning, purely diagnostic approaches can address only the exacerbating complications but not the core problem.

5 Experimental critical OLP

The examination of the empirical assumptions underlying the paradigm of critical OLP and its target problem was motivated by the hope that empirical findings could be used to support a ‘dissolution’ of the longstanding philosophical problem of perception. We now consider how the fragmentation findings that limit the usefulness of the traditional Austinian approach facilitate a new kind of problem ‘dissolution’ and can be deployed to ‘dissolve’ the problem of perception, including the core problem that resists the traditional approach (Sect. 5.1). We then sum up the research program of experimental critical OLP to which we have thus won through (Sect. 5.2) and discuss how this new project in experimental philosophy avoids the apparent non-sequiturs of traditional critical OLP (Sect. 5.3).

5.1 Naturalistic problem dissolution

As standardly conceived, the problem of perception is central to philosophical debates about the nature of perceptual experience. In these debates, resolving the problem is a key aim, but not an end in itself. Rather, philosophical theorising about perceptual experience typically seeks to understand how sense-perception works, what perceptual experience is like, and why it is that way (Logue & Richardson, 2021). Due to the philosophically popular assumption A2 that the common-sense conception of vision enjoys epistemic default status, philosophical theorists then treat this conception as part of their initial evidence base, accept consistency with this conception as a desideratum (e.g., Allen, 2020; Martin, 2002; Nudds, 2009; Strawson, 1979), and address the standard problem of perception as part of an effort to meet it, namely, in order to show their theory is consistent with the different common-sense beliefs that appear to be in conflict (whose conflict the theory shows to be merely apparent) or to determine which of these beliefs should be ‘honoured’ or accommodated by the theory (Crane & French, 2021).

Once a conflict between competing common-sense conceptions has been revealed, assumption A2 motivates efforts to determine which of the competing conceptions of vision is right, or more nearly right, and should be accommodated by philosophical theories of perception. At first blush, this suggests we address the ‘true problem of perception’ (as I called it above) with a natural extension of a familiar approach to the standard problem of perception: Theorists who endorse Indirect Realism but accept that Direct Realism captures the common-sense conception of vision typically complement arguments for Indirect Realism (including arguments from illusion and hallucination) with an error theory that seeks to explain how common sense could – wrongly – endorse Direct Realism (e.g., Russell, 1912; Boghossian & Velleman, 1989). Similarly, a natural approach to the true problem of perception would seek a debunking explanation of either folk theory. Such an explanation of, say, folk Indirect Realism would provide rebutting or undermining defeaters (Pollock, 1986) for this folk theory and thereby explain how the opposing conception of folk Direct Realism can be true or warranted, respectively, despite the conflict within untutored common sense. This approach would solve the true problem of perception, answering the question that articulates the problem.

The moment we take a step back to reflect on philosophers’ typical motivation for addressing the problem, however, we may argue for a more radical response. As we just noted, philosophical theorising about perceptual experience typically seeks to understand how sense-perception works, what perceptual experience is like, and why it is that way. The popular assumption A2 that the common-sense conception of vision enjoys epistemic default status then has theorists regard consistency with folk beliefs as a desideratum, and respond to the appearance of conflicts within common sense with attempts to determine which folk beliefs need to be honoured, and which not. The finding that (pace P1) there is no such thing as ‘the’ unified and coherent common-sense conception of vision, as (pace P2) laypeople are, collectively and frequently individually, torn between folk Direct Realism and folk Indirect Realism, then does not merely expose a conflict within common sense. It also refutes the assumption A2 that there is such a thing as ‘the’ common-sense conception of vision to enjoy epistemic default status. The epistemic rationale for addressing the problem of perception, standard and ‘true’, relies on this assumption. That rationale now seems unsound.

Methodological naturalists have long advocated that philosophical theories of natural phenomena like vision should build on the best available scientific theories of these phenomena, rather than on common sense (or armchair intuitions, etc.) (review: Kornblith, 2016). Findings of fragmentation in folk belief provide a new and principled reason for naturalistic approaches: When there is no such thing as ‘the’ common-sense conception of the phenomenon of interest, and directly conflicting beliefs about it are in poor epistemic standing due to the conflict, then topical common-sense beliefs cannot provide even the initial common ground for debates that seek to understand how the phenomenon works. Fragmentation findings thus support a naturalist perspective: Theorists who seek to understand how vision works, what it is, and why visual experience is the way it is, should from the start build on, and synthesise, the best available theories from psychology and neuroscience (cf. Burge, 2010; Drayson, 2021) and pay no more heed to folk beliefs than psychological and neuroscientific research does.

Folk beliefs can of course be relevant to such research. For example, Michael Graziano’s attention schema theory (Graziano, 2022; Webb & Graziano, 2015) has been invoked to explain extramissionist beliefs about vision (Guterstam et al., 2019) and the ability to explain folk beliefs about the phenomenon can be relevant to the assessment of competing psychological or neuroscientific theories. For these purposes, however, it is irrelevant which (if any) of conflicting folk beliefs is true or to what extent laypeople have warrant for holding them. In brief, findings of conflict in folk belief motivate the adoption of a naturalistic methodological stance in philosophical theorising geared towards the common aims of debates about perceptual experience, and once this stance is adopted, no sound epistemic motivation remains for addressing the problem of perception – standard or true – in such theorising.Footnote 7

Some philosophers associated with the critical ordinary language tradition have espoused non-epistemic motivations, either for addressing philosophical problems more generally (e.g., Wittgenstein, 1933/2005, p.409) or specifically with respect to the problem of perception (e.g., Austin, 1962, p.5): These philosophers seek to overcome the ‘disquiet’ or ‘worry’ engendered by antinomic puzzles (Fischer, 2011). This ‘disquiet’ can be conceptualised as a form of cognitive dissonance, engendered when philosophical arguments apparently reveal conflicts between folk beliefs or when different belief fragments, containing conflicting beliefs, get activated in the same contexts and are difficult to suppress. The influential cognitive consistency paradigm (cf. Gawronski & Strack, 2012) suggests that perceived conflicts between different propositional attitudes regularly engender enough dissonance to prompt remedial action. The desire to overcome such dissonance could provide a non-epistemic motivation for engaging in remedial action in the shape of philosophical efforts to resolve the antinomic puzzle at issue.

However (pace the cognitive consistency paradigm), humans do not have a general need for cognitive consistency, and surprisingly few people have a pronounced preference for consistent propositional attitudes (Cialdini et al., 1995), in particular where they have little personal investment in the content of the beliefs at issue (Kruglanski et al., 2018) – as is arguably the case for Direct Realist and Indirect Realist beliefs about vision, or beliefs about illusions and hallucinations. Once the resolution of real and apparent conflicts between folk beliefs is seen to be surplus to the requirements of their theoretical projects, even philosophers of perception are unlikely to feel the pertinent conflicts keenly enough to adopt this non-epistemic motivation. Moreover, persistent and incorrigible conflicts between belief fragments, including, e.g., naïve vs. scientific theories (Shtulman, 2017) and natural vs. supernatural explanations (Legare et al., 2012) seem to be part of the human condition. Efforts to overcome what dissonance they engender therefore seem futile. We might as well learn to live with the belief conflicts at the root of the problem of perception – and set aside the problem.

To sum up, neither the common epistemic motivation for addressing the problem of perception nor the most relevant non-epistemic motivation are sound. Epistemic problem dissolution seeks to show a problem ill-motivated (Fischer, 2011, pp.68–69). In conjunction with meta-philosophical reflection on the aims and objectives of specific philosophical debates, findings of belief fragmentation can support such dissolution. This novel strategy seeks to ‘dissolve’ an antinomic puzzle by arguing that the truth or epistemic standing of the folk beliefs involved are irrelevant to the philosophical task at hand and that the conflicts between these beliefs are something we can, and should, learn to live with. This affords a novel ‘naturalistic dissolution’ of antinomic puzzles, a genuinely new kind of epistemic problem dissolution.

5.2 The new program

We have thus won through to a new research program for experimental philosophy that examines potential cognitive sources of antinomic puzzles – verbal fallacies and conflicts between folk conceptions – with a view to ‘dissolving’ such puzzles. This program, experimental critical OLP, is inspired by critical OLP, but develops it in a new direction.

In its Austinian form, critical OLP sought to ‘dissolve’ antinomic puzzles by exposing mainly verbal fallacies in the arguments that develop the puzzles (e.g., in the arguments from illusion and from hallucination that develop the problem of perception). Austin’s approach was to show that the arguments are marred by fallacies and fail to mount a sound challenge to common sense (e.g., to the folk understanding of vision) and that the conflicts they appear to bring out within common sense (e.g. between the folk understanding of vision and acceptance of the possibility of illusions and hallucinations) are merely apparent. This approach relies on the empirical assumptions (A1) that philosophers make fallacious automatic inferences in the arguments of interest and (P1) that laypeople share a unified, coherent conception of the phenomenon of interest that can lay claim to being ‘the’ common-sense understanding of the phenomenon (which, as per the further, non-empirical, assumption (A2), it is reasonable to accept in the absence of challenge).