Abstract

It seems to be a platitude that there must be a close connection between causality and the laws of nature: the laws somehow cover in general what happens in each specific case of causation. But so-called singularists disagree, and it is often thought that the locus classicus for that kind of dissent is Anscombe's famous Causality & Determination. Moreover, it is often thought that Anscombe's rejection of determinism is premised on singularism. In this paper, I show that this is a mistake: Anscombe is not a singularist, but in fact only objects to a very specific, Humean understanding of the generality of laws of nature and their importance to causality. I argue that Anscombe provides us with the contours of a radically different understanding of the generality of the laws, which I suggest can be fruitfully developed in terms of recently popular dispositional accounts. And as I will show, it is this account of laws of nature (and not singularism) that allows for the possibility of indeterminism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It seems to be a platitude that there must be a close connection between causality and the laws of nature: the laws somehow cover in general what happens in each specific case of causation. But not everyone agrees, and it is often thought that the locus classicus for that kind of dissent is Anscombe’s famous Causality & Determination (C&D). Here is Anscombe’s formulation of the array of conceptions of causality that she rejects:

It is often declared or evidently assumed that causality is some kind of necessary connection, or alternatively, that being caused is—non-trivially—instancing some exceptionless generalization saying that such an event always follows such antecedents. Or the two conceptions are combined. (Anscombe, 1971, p. 133)

Her ‘radically different account of causation,’ then, rejects the following thesis:

(Necessitation) “If an effect occurs in one case and a similar effect does not occur in an apparently similar case, there must be a relevant further difference.” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 133)

This thesis asserts the impossibility of non-necessitating, i.e. indeterministic causation.Footnote 1 Now Anscombe is often understood to reject Necessitation because she rejects the idea that there is any link at all between causality and laws of nature. This latter position is known as singularism. The intuition underlying singularism is that “[w]hether or not two entities are causally related looks as if it should depend solely on what happens between those two things” (Whittle, 2003, pp. 371–72). Or again: “causal connections between two relata [don’t] depend upon anything extraneous to that relation. Rather, the truthmakers of singular causal statements are entities which are local and intrinsic to those relations” (Whittle, 2003, p. 372). Abstracting from the details of Whittle’s specific account, singularism thus denies that e’s happening because of c has anything to do with rules or principles connecting C- and E-type events in general, i.e. with laws.Footnote 2 We may put this as follows:

(Singularism) In giving a particular causal explanation of why e happens in circumstances c, we do not involve anything other than purely local characteristics of these events and their relation.

Singularists thus reject the following principle:

(Generality) In giving a particular causal explanation of why e happens in circumstances c, we bring e under a general rule (a law) connecting C-type circumstances with the occurrence of E-type events.

Whittle explicitly includes Anscombe under the defenders of singularism. And Davidson (1995), in a less sympathetic vein, does the sameFootnote 3 by listing her among those who reject what he calls the “cause-law thesis.”Footnote 4 The argument that is ascribed to Anscombe by the singularist reading is the followingFootnote 5:

-

1.

If Singularism is true, then the fact that a particular event c causes a particular event e carries no implication for what will happen when other events of type C take place.

-

2.

Therefore, it is possible for a C-event to take place without an E-event following.

-

3.

Therefore, Necessitation is false.

I do not mean to deny the validity of this argument. However, I want to argue that it is completely at odds with the view developed in C&D. In fact, I suggest, Anscombe is not a singularist, and is squarely committed to Generality. Moreover, I claim, she sees no tension between that commitment and the rejection of Necessitation. This fact has been obscured because there is, in addition to the metaphysical variety with which I am concerned, also an epistemological sense of singularism—concerned with the question whether causality can be observed in single cases—which Anscombe does espouse.Footnote 6

Now, my interest here should not be taken to be exegetical. Rather, I believe that the failure to correctly understand Anscombe’s argument is significant because it is symptomatic of a blind spot shared by both singularists and anti-singularists: an unquestioned common assumption about the kind of generality exhibited by laws of nature. On a different understanding of that generality, I will argue, it is not just compatible with, but positively implies the rejection of Necessitation. Since I take this to be the true core of Anscombe’s argument, my aim will be to develop this systematic point through a partial reconstruction of C&D—although, as we will see, her account must be supplemented at crucial points.

I will begin (§2) by clarifying the point of Anscombe’s negative remarks about neo-Humean accounts. It may be thought that she targets only very specific accounts according to which causation is the instantiation of “universal propositions.” And although it is such accounts that constitute the paradigm on which Anscombe focuses, I will argue that the core of her critique applies to any account according to which the generality of laws of nature is what I will call quantificational generality—no matter what, exactly, we take the precise form of the laws, and their precise relation to singular causal relations to be. We may call accounts that conceive of the generality of the laws in quantificational terms broadly Humean, and on such accounts, I argue, the laws of nature indeed have nothing to do with causality.

However, the conclusion to be drawn (and that is drawn by Anscombe) is not that singularism is true—for singularism is in fact compatible with the quantificational view of generality. Instead, I argue, there is another option: we should espouse a dispositional view of the generality of laws of nature (§3). Although I believe Anscombe’s slogan that “the laws of nature are like the laws of chess” strongly points towards that idea, she does not develop it in detail. I therefore draw on certain strands in recent work on dispositions and powers in order to sketch an Anscombean account of causation and laws of nature.

On the resulting picture, the question whether Necessitation is true is not yet settled, although it is fundamentally transformed (§4). As an example of a view that rejects Humean generality but still accepts Necessitation, I consider the Kantian view (at least as it is often received), and argue that it is unfounded.Footnote 7 I conclude that, having liberated ourselves from the Humean conception of generality, there is simply no reason to insist that causation must be deterministic.

2 Against humeanism

Anscombe’s initial range of targets is broad, and includes anyone who subscribes to Necessitation, including Aristotle, Spinoza, Kant, and Hume (Anscombe, 1971, pp. 134–35). However, it would be wrong to conclude that her subsequent arguments are intended as a blanket criticism of all of those views, and their contemporary variants. In particular, it is not that all of the aforementioned philosophies go wrong in accepting Generality, so that the only remedy is to accept Singularism. For the nature of Anscombe’s disagreement with, say, Kant and Aristotle, I will argue (§4), is different from that of her disagreement with the Humean. And it is only when we fail to see the alternative to a Humean account of laws of nature that it can seem as if rejecting Necessity is tantamount to rejecting Generality. In this section, I will therefore consider in detail Anscombe’s argument against the family of broadly Humean views. Although Anscombe focuses on only a particular kind of Humean theory, according to which causation is the instantiation of a “universal proposition,” I will argue that the center of her critique is the Humean’s understanding of the kind of generality that is exhibited by a law of nature—what I will explain below is a quantificational conception of that generality. By “broadly Humean” I mean any view that adopts such a quantificational conception of generality, even if it has a substantially different conception of the precise form of a law of nature,Footnote 8 or of the way in which singular causal relations depend on them,Footnote 9 than the classical neo-Humean account. Even if Anscombe does not address such views directly, I believe they fall within the scope of her argument. However, my argument will follow Anscombe in bringing into view the underlying conception of generality through considering problems with the classical neo-Humean account.

Anscombe begins by reminding us of the way in which Hume himself sought to cast doubt on the concept of causation, or its status as an objective feature of the world. He did so by first insisting that causation involves a necessary connection, and then arguing that such necessary connections are not to be found “in the situations, objects or events called ‘causes’ and ‘effects’” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 134)—but rather only in the subjective expectation of E-like events after C-like events, grounded in the experience of “constant conjunction.” And as Anscombe sees it, opponents of Hume’s subjectivism have since then “tried to establish the necessitation that they saw in causality […] either a priori [i.e., like Kant, D.O.], or somehow out of experience” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 135).

Neo-Humean accounts attempt to do the latter: they attempt to account for causality (as an objective feature of the world) in terms of the instantiation of certain observed regularities—the laws of nature. On such views, a particular event c will be the cause of a particular event e if and only if there is a law of nature that states (for instance) that E-like events always follow upon C-like events. The laws of nature, understood as exceptionless generalizations, are thus appealed to in order to account for the necessary connection which Hume himself thought we could not find in the world, but only in the subject. And at first sight, such neo-Humean accounts may seem convincing. For they not only promise to vindicate the idea of causation as an objective feature of the world, but also seem to account well for the fact that particular causal statements are explanatory. In showing that a particular c and e instantiate a law, the idea is, we explain the occurrence of e by showing it to be an instance of a rule. It is a fact about the world, say, that colliding objects always transfer momentum—and so it is no mystery that this billiard ball just now started to move. A basic commitment of various species of the neo-Humean family of accounts of causation is thusFootnote 10:

(Humean Generality) In giving a particular causal explanation of why e happens in circumstances c, we bring c and e under an exceptionless generalization (a Humean law) connecting Cs and Es.

Although it may appear that Humean Generality is just equivalent to the Generality principle defined in the introduction, I will argue that it is in fact only one specific way of articulating the latter abstract principle. To see this, we should inquire more closely into the form of Humean laws. That Humean laws of nature are exceptionless generalizations means nothing else than that they are universally quantified propositions. It is this aspect of Humean laws that is shared by all views in the broadly Humean family, even those that do not analyse singular causation simply in terms of subsumption. The most obvious form of such a law is something like:

(Deterministic Humean Law) For all events of type C, whenever such an event occurs, an event of type E occurs thereafter.

Anscombe calls such laws “universal propositions,” and it is easy to see that their universality consists precisely in their exceptionlessness, i.e., their claim to say what happens for all Cs, and all the time. But now is perhaps the right time to consider that Humean laws may arguably also take a slightly different shape, namely:

(Statistical Humean Law) For all events of type C, whenever such an event takes occurs, then there is an n% probability of an event of type E occurring thereafter.

Statistical laws are still universal in the sense that they say what happens with respect to all Cs, even though they no longer claim that E’s follow all the time. As Davidson (1995, p. 266) puts it, “[s]uch laws are universal and are exceptionless,” for “the probabilities they predict have no exceptions.” If a particular c and e instance a statistical Humean law, then we can say that c causes e probabilistically. Anscombe does not consider the possibility of such non-deterministic Humean laws, and so she does not see that a Humean may, in fact, reject Necessitation. Interestingly, Davidson (1995, p. 266) even suggests that statistical laws might just be what Anscombe is insisting on, and that thus, “it is possible […] that Anscombe is not questioning the cause-law thesis.”Footnote 11 However, I will argue that the question whether or not there can be less than deterministic Humean laws does not affect the core of Anscombe’s discontent with the Humean picture. For, as we will see, Anscombe’s discontent with Humean laws ultimately lies with the form of generality they involve, and on this point there is no difference between deterministic and statistical Humean laws.

Now that we have a clearer grasp of the shapes Humean laws can take, it is time to consider in what sense they are specifically Humean—and thus, why Humean Generality is but a particular way of interpreting the more abstract principle of Generality. We can get this into view by focusing on Anscombe’s two main complaints against neo-HumeanismFootnote 12: a problem about the exceptionlessness of Humean laws, and a problem about their explanatory impotence. Although I find Anscombe’s arguments convincing, the purpose of the following discussion will not be to settle any of the issues raised, but rather to show how an alternative anti-Humean picture can emerge from taking those arguments seriously.

Let us first consider this complaint:

…if you take a case of cause and effect, and relevantly describe the cause A and the effect B, and then construct a universal proposition, “Always, given an A, a B follows” you usually won’t get anything true. You have got to describe the absence of circumstances in which an A would not cause a B. But the task of excluding such circumstances can’t be carried out. (Anscombe, 1971, p. 138)

To take Anscombe’s example: supposing it is a law of nature that matches ignite when struck, still any attempt to construct a true universal proposition along the lines of “Always, when a match is struck, it will ignite” seems doomed to fail, because there will always be circumstances which prevent the result from obtaining (say, the match’s being wet). It will thus always be necessary for the generalizations to be…

…hedged about with clauses referring to normal conditions; and we may not know in advance whether conditions are normal or not, or what to count as an abnormal condition. (Anscombe, 1971, p. 138)

For example, normal conditions presumably include the match not being covered in liquid (except, perhaps, certain liquids that can make the match more flammable). And this threatens to undermine the supposed explanatory force of a law of nature. For now the laws may seem to become just a trivial list of specific circumstances in which, e.g., match-strikings in fact are followed by ignitions.

This problem of hedging the laws of nature with references to “normal conditions” has, of course, become widely discussed, especially since Nancy Cartwright’s (1983). However, from the Anscombean perspective I am developing here, contemporary attempts to specify the normal conditions are misguided from the start.Footnote 13 If we are allowed to add exceptions to the laws, it is no surprise that we can come up with some true statements of the form: “matches light in cases X, Y, Z.” Even if we grant that it is possible to find some such statements that are not completely trivial—i.e., that do not boil down to a specific list of each and every match-striking that is followed by an ignition event—the question should be: in what sense does a statement summarizing in which kinds of cases match-strikings are followed by ignitions still explain why, in a particular case, the match started burning when it was struck?

At first it might seem as if the Humean has an easy answer: it would be no worse an explanation than the kind of explanation provided by an unhedged, exceptionless regularity! After all, “matches light when struck [in all cases]” and “matches light when they are struck [in cases X, Y, Z]” provide for exactly the same form of explanation. When a particular match does light when struck, this is simply one of the events that we quantify over in the Humean law. Both laws therefore can be used to show that what happens in this particular case is an instance of what happens at different times and places where […] is the case. The generality of the Humean law is quantificational: the sense in which it shows that the occurrence of a particular e is, as it were, no mystery, is just that the particular case is shown to belong to a set of cases in which Cs are followed by Es. Hedged laws would thus do as good a job of providing for particular causal relations and explanations as ‘strict’ laws—much in the same way that, as we have seen, probabilistic and deterministic laws are equally suitable for this purpose.

This response on behalf of the Humean gives us everything we need to understand Anscombe’s second, most fundamental complaint against the idea of Humean laws. Let us assume for a moment that we can find some true exceptionless generalizations suitable to be laws of nature. Even then, Anscombe argues, the quantificational generality of these laws means that they could still not provide us with the kind of explanation for which we are looking in an account of causation:

There is something to observe here, that lies under our noses. It is little attended to, and yet still so obvious as to seem trite. It is this: causality consists in the derivativeness of an effect from its causes. This is the core, the common feature, of causality in its various kinds. Effects derive from, arise out of, come of, their causes. […] Now analysis in terms of necessity or universality does not tell us of this derivedness of the effect; rather it forgets about that (Anscombe, 1971, p. 136)

In a slogan: causation is production. Quantificational generality is incompatible with this insight because it requires that the particular events are, in a sense, already there to be quantified over: the reality of these events must be prior to any law that “explains” them, and in virtue of which causal relations obtain between them. This becomes especially clear when we consider a feature of David Lewis’s influential neo-Humean account. The idea that the laws of nature describe regularities presupposes, in Lewis’s words, that:

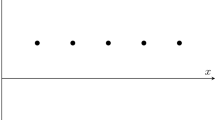

…all there is to the world is a vast mosaic of local matters of particular fact, just one little thing and then another. […] For short: we have an arrangement of qualities. […] All else supervenes on that. (Lewis, 1986, pp. ix–x)

The idea of this so-called “Humean mosaic” is that what happens at every time and place is a brute fact: there is thus no reason (in any interesting sense) why, e.g., match-striking events are often or always followed by ignition-events.Footnote 14 We just observe that this is often the case: the laws of nature describe mere regularities in what is fundamentally a static world. Commitment to the mosaic is just the Lewisian inheritance of Hume’s insistence that causality is not an objective feature of the world: instead of declaring causality to be merely subjective, it is declares to be merely supervenient on the basic facts. Now even if not everyone who defends a broadly Humean view agrees with the finer details of Lewis’s metaphysics, it still nicely illustrates a feature of the quantificational conception of the laws: the existence of the events mentioned in a law is logically prior to the law that explains them.Footnote 15 Thus, there is a very real sense according to which, on a broadly Humean account, effects do not “derive” from their causes, and there is simply no such thing as one thing, event, or state of affairs producing another. The “local matters of particular fact” are prior, and the general propositions about them only describe, and do not explain, their arrangement. For to say that the generality of the laws of nature is quantificational is to say that the particulars themselves do not contain any generality capable of explaining their relation to other particulars—neither the particulars nor the laws produce their effects.Footnote 16 Instead, quantification requires that the singular cases that it concerns are simply there to be counted over. On this Human picture, it is thus more accurate to say that the particular facts explain the general truths than the other way around. As Anscombe puts it: “through [the universality of a Humean law] we shall be able to derive knowledge of the effect from knowledge of the cause, or vice versa, but that does not show us the cause as the source of the effect” Anscombe (1971, p. 136).Footnote 17

From an Anscombean point of view, the Humean is thus right to say that hedged and statistical laws provide the same kind of explanation as strict and deterministic laws. But far from implying that the former are equally fine, the suggestion in C&D is, we should conclude that the latter are equally bad. Even a strict and deterministic law amounts to nothing other than a summary of what happens anyway, in some proportion of cases.

3 The laws of nature are like the laws of chess

Given the results of the previous section, a commonly heard anti-singularist complaint—that by rejecting Generality, one gives up on the very idea that causation is linked to explanation (Davidson, 1995)—seems to be ill directed at Anscombe. For her dissatisfaction with saying that c and e are causally related when they instantiate a Humean law is precisely that this does not explain them at all—it does not “show us the cause as the source of the effect.” This is a hint that something goes wrong in the characterisation of Anscombe as a singularist. As I will argue in this section, it is not that Anscombe is uninterested in the business of explanation through general laws. Rather, her disagreement is in the first place with the Humean metaphysical outlook, on which particular matters of fact are simply given, and precisely not explained. And singularism does not question that outlook per se. Take Whittle’s own proposal of what singularism involves, which she puts by saying that “the truthmakers of singular causal statements are entities which are local and intrinsic to those relations” (Whittle, 2003, p. 372). This amounts to the following: instead of being something that supervenes on the mosaic, causality is itself an “entity” to be found within it—a “causal glue” lying in between cause and effect. Causality would then itself be (in Lewis’s words) a “purely local matter of fact.”Footnote 18

The debate between singularism and anti-singularism is thus typically conducted without questioning the quantificational conception of the generality of laws. And in so far as singularism is compatible with the latter, the two positions merely differ on the question regarding the truthmakers of causal claims.Footnote 19 By contrast, Anscombe would insist that, as long as the quantificational conception—on which it is ultimately the particular events or states of affairs that ground the laws, rather than vice versa—is in place, it does not matter whether we think of Humean laws or local entities as “truthmakers” of causal claims. In neither case can we see effects as “deriving from” causes. That is why, as I will now show, Anscombe suggests that in order to understand how causes could be the “source” of their effects, we must rethink the form of generality exhibited by laws of nature.

On my understanding of Anscombe, she insists that we must reject Humean Generality, and the idea that the laws of nature describe what happens “in every case.” But, I submit, we can reject that principle while still holding on to the more abstract thesis Generality —the idea that causal explanation involves reference to a general rule. The following remark of Anscombe’s suggests how this might be possible:

Suppose we were to call propositions giving the properties of substances “laws of nature.” Then there will be a law of nature running “The flashpoint of such a substance is…,” and this will be important in explaining why striking matches usually causes them to light. This law of nature has not the form of a generalization running “Always, if a sample of such a substance is raised to such a temperature, it ignites.” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 138)

Examples of laws of nature, as Anscombe conceives of them, are, e.g., “sulfur ignites at 480 K,” or “iron melts at 1811 K.” Such statements describe “the properties of substances.” What Anscombe is suggesting is therefore that the laws do not say what happens always and everywhere in nature, but instead describe particular natures—the nature of iron, sulfur, wood, and, perhaps, also of such substances as plants and animals, too. Her picture, as I understand it, is thus broadly neo-Aristotelean, in that the world is conceived to consist of individuals falling under natural kinds. So in what follows, I will speak of laws of nature as pertaining to natural kinds (or substance-forms, as I will also call them), and of causal relations as pertaining to particulars that fall under them. I do not wish to deny that we can, of course, meaningfully talk about things that are seemingly not substances (e.g., artifacts, fields, or stuffs) as causing things. As will become clear, what is important to the Anscombean understanding of Generality is that we can understand causation as the manifestation of potentialities, dispositions or powers that belong to objects, in some sense, in virtue of what they are, or their form—whether the relevant form be a substance-kind or not.Footnote 20 And a paradigmatic way of ascribing a power to something is by bringing it under a natural kind: in identifying something as a bit of iron, say, we understand it to, e.g., conduct electricity.Footnote 21

Now, unlike Humean laws, a statement describing the nature of sulfur is not threatened by finding a particular bit of sulfur that doesn’t ignite when brought to its flashpoint (because, say, it’s wet). Rather, what the laws governing sulfur tell us is that:

If a sample of such a substance is raised to such a temperature and it doesn’t ignite, there must be a cause of its not doing so (Anscombe, 1971, p. 138)

But isn’t this just as empty as the formula that threatened to make the Humean account vacuous—namely, “Always, when a match is struck, it ignites—except when it doesn’t?” The answer is: no. For that statement was a universally quantified proposition, and the problem with the hedging clause is precisely that it is part of the content of the proposition. The statement gives a list of precisely those situations in which match-strikings are followed by ignitions, and it threatens to become vacuous precisely because in order to generate the list, we must already know what happens in each individual case. By contrast, note that an Anscombean law such as “iron melts at 1811 K” is not, on the face of it, a quantified statement at all. That is: it doesn’t say anything of any particular bit of iron. Rather, it describes the kind iron: it says what iron does in general.

The generality of the laws of nature thus conceived comes out in the peculiar use of the present tense: “iron melts,” we say—in contrast to “this bit of iron is melting (here and now).” Indeed, statements about the kind iron could conceivably be true without any piece of iron ever having molten, or ever going to melt, in actuality. To better understand this conception of the generality of laws of nature—of which Anscombe offers us only a sketch—it will prove fruitful to note that Anscombe’s examples of laws of nature constitute what Rödl (2012, ch. 6) calls “time-general” statements. Rödl offers a critique of the Humean idea of laws of nature similar to the one I attributed to Anscombe in §2, and in its place offers an account of laws that he attributes equally to Aristotle and Kant—and that I believe can be fruitfully viewed as an extension of Anscombe’s suggestion. As he explains, the possibility of an exception is part of the form (as opposed to the content) of a time-general statement: in describing the general kind sulfur as “igniting at 480 K,” we are precisely allowing that in particular cases, something may interfere with, or prevent the result from happening.Footnote 22 Compare the time-general statement “John runs on Sunday morning,” which ascribes a particular habit to John. This statement is not falsified when he, overcome by the common cold, skips a run on a particular Sunday.

Time-general statements are thus not descriptions of what happens at certain specified moments: the particular cases are not logically prior to the general statement. And that is just to say that their generality is not that of quantified proposition. What, then, is the relation between general law and particular happening? In brief, that relation is explanatory precisely in the sense that Anscombe wants: the nature described in a sentence expressing such a law is the source of the effect. But how is this possible? If the laws of nature allow for particular occasions in which the result does not occur, how can they still be explanatory of the cases in which the result does occur? Well, the law that “sulfur ignites at 480 K” tells us, for example, that it is no accident when a piece of sulfur, raised to that temperature, ignites. It is no accident in the following sense: we do not need to look beyond the laws describing what sulfur is to understand why this thing here and now is igniting. If, on the other hand, the match doesn’t ignite, a special explanation is required, since we cannot understand this merely by reference to the nature of sulfur: “there must be some cause of its not igniting” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 138) means “there must be some other substance involved that’s stopping it”—in our example case, the water, which is preventing the match from burning..

Another way to understand how the laws of nature are explanatory, on this picture, is to notice that the contrast between “iron melts at 1811 K” and “this bit of iron (here and now) is melting” is precisely the contrast between potentiality and actuality.Footnote 23 For in giving a causal explanation, we indeed refer a particular occurrence (this iron melting here and now) to something more general—namely, iron’s power to melt, which can be manifested in an indefinite amount of cases. Thus the laws of nature ascribe potentialities, powers, or dispositions to certain substances. This seems to be what Anscombe (1971, p. 141) is suggesting when she claims that “the laws are like the laws of chess”: like the latter, the laws of nature describe the “powers of the pieces,” rather than describing regularities in the actual moves that are made in the course of a game of chess.

Anscombe’s suggestion that laws of nature must be understood to exhibit their own sui generis form of generality can therefore fruitfully be connected to recently popular so-called dispositional theories of causality.Footnote 24 On an Anscombean/dispositionalist picture, causal explanation of a particular happening—which is described in a time-specific statement, e.g., A has done/is doing X—will consist of the following three elements:

-

1.

this particular substance A is of kind N (form ascription)

-

2.

kind N has the power to X in circumstances C (law of nature)

-

3.

A found itself in circumstances C (stimulus condition)

The first of these elements—and indeed, the whole form of the explanation—is anti-Humean, because it rejects the idea that the world consists, at bottom, of merely local qualities. Rather, since particulars are substances that fall under kinds or forms, they already contain something general within them (they are “this-suches,” as Aristotle says). That is what allows us to see them as the source of the changes that they bring about (more on this in §4). Importantly, therefore, the suggestion is not that we have a grasp of powers or dispositions independently of laws of nature. That is: it is not that the laws of nature summarize the fact that (for some reason) bits of iron have the power to melt. In that case, we would be confronted with two seemingly unrelated kinds of generality: the general fact that a particular bit of iron can melt (absent interference or prevention), and the general law of nature that iron things melt. This would raise the question whether it is just an accident that iron things melt, thus providing the Humean with a place to insert her skeptical knife: what is the mysterious connection between iron and having the power to melt?Footnote 25 Anscombe’s suggestion, as I understand it, is that we do not have to conceive of the laws in this way. Instead, the time-generality of a law of nature is the generality of a power: that iron melts at 1811 K manifests itself in the actual melting of a particular bit of iron here and now. Thus, when we ascribe certain powers (to melt at 1811 K, to conduct electricity with such-and-such a resistance, etc.) to some solid particular, we are thereby describing its nature.Footnote 26

Notice that this anti-Humean picture also involves a different paradigm of a causal explanandum. For if the laws of nature describe particular natures, the concept of causation will not be the concept of a uniform relation obtaining between every pair of cause and effect events (as it is for the Humean), but rather the abstract concept of the manifestation of a power or potentiality, i.e., of production.Footnote 27 Thus, statements such as the following will count as paradigm descriptions of causation: “the contraption shut the window,” “the sun is heating the stone,” and perhaps “I am slicing the bread”—and not sentences of the form “event c causes event e.”Footnote 28 Of course, that is not to say that we cannot meaningfully utter sentences of the latter form.Footnote 29 However, as we will presently see (§4), it does mean that the question whether causes necessitate their effects (i.e., are deterministic) is fundamentally transformed.

Clearly, much more needs to be said to develop this sketch into a full account of powers and causation. Nevertheless, the above shows that the time-generality of power-ascriptions makes it possible to reject Humean Generality without thereby espousing Singularism. Rather than rejecting Generality, an Anscombean/dispositionalist account is firmly committed to it. For it is precisely through general statements (anti-Humeanism and law of nature above) that we can understand why, e.g., this bit of iron is now molten. In a causal explanation, we show how a general law connecting circumstances (stimulus conditions) with a certain type of effect (a power-manifestation) is being realised in what happens here and now. On this account, one clearly cannot argue that Necessitation is false because Generality is false. The argument that, as we saw in the introduction, is often ascribed to Anscombe thus cannot possibly be hers. It is therefore time to revisit the question of Necessitation. What is it about the idea that “the laws of nature are like the laws of chess” that allows for indeterminism?

4 Dispositional generality & necessitation

I have argued that on the Anscombean view there is an intimate connection between the laws of nature and powers or dispositions, and that she thus subscribes to Generality. So the argument in the introduction, from Singularism to the rejection of Necessitation, cannot in fact be Anscombe’s. But on what grounds, then, does Anscombe reject Necessitation? In this section, I will give an alternative argument for the rejection of Necessitation—i.e., for the conceptual possibility of indeterminism—that is in line with the Anscombean understanding of Generality. In the first part of this section, I will first clarify what it would mean for the world to be indeterministic, on the Anscombean account. As I will explain, it would mean that the world contains indeterministic powers. However, one might suspect that indeterministic powers are actually impossible. That would mean that an Anscombean understanding of the laws is still compatible with Necessitation. In the final part of this section, I will consider such a view—namely, the Kantian oneFootnote 30—which shares the Anscombean conception of the laws, but nevertheless insists on the truth of Necessitation. I will argue that the Kantian view is unfounded. We will then be able to understand Anscombe’s argument: once we adopt a dispositional view of the generality of the laws, there is simply nothing to rule out the possibility of indeterministic powers. That means Necessitation is false, even if the question whether the world in fact contains indeterministic powers remains an open one.

What, then, is Anscombe’s argument for the rejection of Necessitation? As we have seen above, it is part of the form of laws of nature that there can be interference and prevention: a power may in principle be prevented from manifesting normally. It can therefore be tempting to think that Anscombe’s argument against Necessitation (given that it is not based on Singularism) must instead be based on this observation. The idea would be that indeterminism must be true because, given the Anscombean/dispositionalist account, there is no logical necessity between the occurrence of the cause and of the effect. And interestingly, some contemporary defenders of dispositionalist accounts argue precisely along these lines (e.g. Mumford & Anjum, 2014): they believe that, since power-manifestations can in principle be interfered with, a deterministic world could not contain powers at all. According to this view, indeterminism would not just be a conceptual possibility—it would be a conceptual necessity.

Tempting as that argument can seem, however, I think it is a mistake. To reject a Humean view of the generality of laws of nature in favour of the Anscombean is indeed to insist that there is no logical necessity that, whenever a c is present, e must also occur—for there may always in principle be an interfering factor. But that is not yet enough to reject Necessitation. For recall that that principle says the following: “If an effect occurs in one case and a similar effect does not occur in an apparently similar case, there must be a relevant further difference.” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 133) And the presence of an interfering factor that prevents the manifestation of a power (for instance, the water on the match in our example) is surely “a relevant further difference.”

That the possibility of prevention is part of the form of generality of Anscombean laws of nature, then, does not mean that determinism must be false. For that a power-manifestation is the kind of thing that can in principle be interfered with does not mean that, on a particular occasion, interference or prevention may not be ruled out. Given the actual arrangement of substances at a particular time and place, interference may be impossible there and then.Footnote 31 Picture two asteroids on collision course in deep space, far away from other largish rocks. There may simply be nothing around that can reach the asteroids in time to prevent collision, which is therefore unavoidable. Upon impact, the one asteroid will exercise its power to transfer momentum to the other, becoming a deterministic or necessitating cause of change in the other.

We must therefore clearly separate the question of determinism (i.e., whether something is a necessitating cause) from the question of interference and prevention. Anscombe explains the difference as follows:

…a necessitating cause C of a given kind of effect E is such that it is not possible (on the occasion) that C should occur and should not cause an E, given that there is nothing that prevents an E from occurring. A non-necessitating cause is then one that can fail of its effect without the intervention of anything to frustrate it. (Anscombe, 1971, p. 144)

On Anscombe’s account, deterministic (“necessitating”) causes are therefore clearly not impossible.Footnote 32 But they are not necessary, either. Anscombe’s thought seems to be that we may distinguish between indeterministic and deterministic powers—powers that are such as to manifest whenever their manifestation conditions obtain, and those that are not. Sulfur’s power to burn, for instance, is in the first category, while radium’s power to decay belongs in the second. For although a radium atom in normal conditions can decay at any time, it does not have to do so at any specific time. While when a piece of sulfur is brought to its flashpoint and it doesn’t ignite, there must be some cause that explains this, the radium atom can fail to decay without there being some special explanation. Notice that this is to say that radium’s power to decay does not have any specific stimulus conditions: the power can manifest whenever there is a bit of radium present (and nothing prevents it). So the sense in which, in giving an explanation of a particular manifestation of this power, we “connect C-type circumstances to E-type events”—as Generality states—is admittedly thin in these cases: it is just that in general, the presence of a bit of radium (C) is connected to events of the type “decaying” (E).Footnote 33

If nature indeed contains substances with indeterministic powers, then there will thus be another sense in which the laws of nature are like the laws of chess: the powers of the pieces in a game of chess do not, generally, leave open just one move in the game. Rather, given the configuration of pieces on the board and their various powers, multiple moves (but not just any move!) will be possible: “the play is seldom determined, though nobody breaks the rules” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 143).

This further clarifies how the Anscombean account of laws can capture the insight that causality is production. The sense in which “[e]ffects derive from, arise out of, come of, their causes” is this: the laws of nature constrain the range of future possibilities, and causation is simply the actualization of one of these possibilities through the manifestation of a power.Footnote 34 Contrast the Humean account, on which the laws merely describe patterns in the mosaic of local, particular matters of fact. For the Humean, there is, fundamentally, no reason why a match starts burning rather than, say, just evaporating into thin air when it is brought to 480 K degrees. On the Anscombe-inspired picture I have described here, by contrast, the powers of a substance rule out all but certain future developments—that is the sense in which, in the manifestation of a power, the effect “derives from” its cause. But as we can now see, that does not have to mean that all but one possibility is always ruled out (although that may occur on occasion, as in our asteroid case). Just like in a game of chess, the pieces on the board will mutually constrain each other’s abilities to move, but will generally leave open a number of legal moves.

If there are indeterministic powers, the configuration of substances in nature, like that of pieces on a board, would thus contains the seeds for a number of different future developments. But might the world indeed contain indeterministic powers? This questions affords us the opportunity to briefly reflect on the relation between Anscombe’s conception of causality and that of someone who, as we saw earlier (§2), she lists as one of her opponents: Kant. Interestingly for our purposes, Kantian accounts of causality (at least on certain influential readings) precisely agree with Anscombe in rejecting Humean Generality—while, however, hanging on to Necessitation. According to the Kantian, that is, the concept of a power involves the concept of necessitation. Reflecting on the contrast between the Kantian and Anscombean accounts may thus help us to answer the question why one should believe that there might be indeterministic powers.

Let us begin by considering another apparent point of agreement between Kant and Anscombe. Both argue against Hume that it must be possible to observe causality in the singular case.Footnote 35 Here is Anscombe’s response to Hume’s insistence that this is impossible:

Someone who says this is just not going to count anything as “observation of causality.” This often happens in philosophy; it is argued that “all we find” is such-and-such, and it turns out that the arguer has excluded from his idea of “finding” the sort thing he says we don’t “find.” And when we consider what we are allowed to say we do “find,” we have the right to turn the tables on Hume, and say that neither do we perceive bodies, such as billiard balls, approaching one another. When we “consider the matter with the utmost attention,” we find only an impression of travel made by the successive positions a round white patch in our visual fields. (Anscombe, 1971, p. 137)

Although admittedly less systematically developed than Kant’s Analogies of Experience, I think we can recognise a typically Kantian thought here: if we couldn’t observe causation in the individual case, there would be no such thing as objective perceptual experience.Footnote 36 However, for Anscombe, these remarks are part of her critique of Necessitation. Her thought seems to be that widespread belief in Necessitation is a consequence of the mistaken assumption that laws of nature must be strict universal regularities. But, she argues, absent acceptance of Hume’s argument that causality cannot be experienced in the single case, there is no reason at all to think that universal regularities (let alone deterministic ones) have anything to do with causation. For Kant, by contrast, a commitment to Necessitation seems to be part of his argument that objective experience of an event must somehow involve causality. In the Second Analogy, he writes:

[The objective time order consists] in the order of the manifold of appearance in accordance with which the apprehension of one thing (that which happens) follows that of the other (that which precedes) in accordance with a rule […] a rule, in accordance with which this occurrence always and necessarily follows.Footnote 37

I think Anscombe would agree that in order to be able to observe one billiard ball causing another to move—and not just observe “an impression of travel made by the successive positions a round white patch in our visual fields”—there must be a “rule” that connects the movement of the first ball with the subsequent movement of the second. For the idea of such a rule is just the idea of a law of nature: something general that explains the effect as “arising out of, coming from” the cause. However, as I’ll explain below, Anscombe would deny that the Kantian argument contains anything that sanctions the conclusion that such a rule would have to be deterministic. In doing so, I will rely on Rödl’s (2012) account of the Second Analogy.Footnote 38

Rödl argues that in order to have objective experience of a change, we must be able to see what is happening here and now as progressing towards a state that is precisely not yet achieved. Applied to Kant’s own example, the idea is that in order to be able to see a ship as currently moving from A to B, we must be able to understand that change as part of a larger movement of the ship’s—its drifting downstream, say.Footnote 39 But how is that possible, given that the ship is precisely not downstream yet? Here is Rödl’s eventual answer to that question:

What we perceive contains a state toward which the movement is progressing: the ship lower down the stream. This state is present in what we perceive, but not in such a way that the ship’s drifting down the stream entails that it will be lower down the stream. It may run into a sandbank. The state that is yet to come is present as the state that the ship will reach if what is happening here and now conforms to what happens in general. If S is doing A, then S is not only first F and then G; rather, a rule connects F and G. (Rödl, 2012, pp. 184–185)

The rule connecting two states of the ship (its first being here, then there) is one that states “what happens in general”: it has the generality of a law of nature, as explained in §3. We can see the ship drifting down the stream—even though it has not reached downstream yet—because we can frame a time-general thought, say, floating objects drift downstream: that is a power they have, unlike “drifting” upstream. According to this reading of the Second Analogy, the Kantian point is thus that experience of change is experience that something general is manifesting itself in a particular situation.Footnote 40 Kant and Rödl call this a law or rule, but as the kind of generality in question is the one we discussed in §3, we might with equal right call it a power.Footnote 41

Now if this is indeed the right way to read the Analogy, Anscombe’s challenge to the Kantian would be the following: what in the above account of the possibility of perceptual experience of change implies that the rule which connects two states of the ship must be one “in accordance with which [the effect] always and necessarily follows?”Footnote 42 Note that the challenge is not why, if we see the ship drifting downstream, it should necessarily follow that it will reach downstream: it need not, for as Rödl says, “it may run into a sandbank”—interference and prevention are in principle possible. The rule is simply that objects drift downstream (when placed in a river). Now that is doubtlessly a rule that describes a deterministic power. The challenge is why that would always have to be so. That is, why must the rule be of the variety of, e.g., “sulfur ignites (when brought to 480 K)?” For, if what we have in front of us is, say, a bit of radium, it seems like we could be aware of a general rule that connects one state (no reading on the Geiger counter) with a later one (the device starts to beep)—the general rule that radium atoms decay (but not at any specific time).

The Kantian argument (or at least, Rödl’s reconstruction of it) seems to require only that when a change is actually occurring, we must be able to bring it under a general rule that shows it to be no accident.Footnote 43 That is, given that a change is or was going on, we must be able to understand the new state as “deriving from, arising out of, coming of” the old one. But why should the rule state that the change is inevitable whenever a substance is in the manifestation conditions? From the Anscombean perspective, that demand can seem to make sense only if we have insufficiently rid ourselves of Humean inclinations: that is, if we think that what it is for a happening to be no accident is for it to always happen in certain circumstances.Footnote 44 But why should anyone who has already rejected Humean Generality think that?Footnote 45

5 Conclusion

I have argued that, rather than being a simple-minded rejection of the importance of general laws, Anscombe’s C&D in fact provides the contours of an account of the proper kind of generality that characterizes the laws of nature: the time-generality of powers-ascriptions. Moreover, I have shown how adopting such an Anscombean view allows us to understand the possibility of indeterminism in a distinctly non-Humean way. If we think of the laws of nature as constraining the range of antecedent possibilities, there is no reason to insist that they must always leave open merely one possibility. For while Anscombe’s insistence that we can observe causality in the single case indeed requires that we be able to see the general at work in the particular (as the Kantian agrees), all this need come down to is this: that we can see in the previous state of affairs the seeds of the later. That is, for any change, there must be an answer to the question: what power gave rise to this?Footnote 46 It seems we simply go wrong when we confuse this for the stronger, Kantian requirement that the earlier state not also contain the seeds of a different possible development. The Anscombean argument against Necessitation, then, is simply this. If the laws of nature are like the laws of chess in that they describe the powers of substances, and causality is just the manifestation of one such a power, then there is simply nothing in the concept of a law or a cause that rules out indeterminism. It thus relies not on a wholesale rejection of Generality, but on a specific non-Humean interpretation of it.

Notes

Note that rejecting the principle thus does not imply the truth of indeterminism, but merely leaves conceptual room for it: it is a further question whether our world actually contains non-necessitating causes (see §4). As Anscombe indicates, Necessitation is often combined with the view that laws of nature are “exceptionless generalizations,” and many have thought the two ideas are mutually reinforcing. However, as we will see in §2, one can also combine that view of laws of nature with the rejection of Necessitation (given the possibility of statistical laws).

Note that this does not mean that all singularists need to deny that “causal relations are part of more general patterns” (Whittle, 2003, p. 371). That is, it may be that singular causal relations imply certain general patterns (cf. fn. 18). But the obtaining of these general patterns is not part of what makes c the cause of b (at best, it is an accidental consequence of the latter). Interestingly, Whittle reads Anscombe as denying even the weak thesis that singular causal statements imply general patterns—while as I will argue, Anscombe is in fact committed not just to Whittle’s weaker thesis, but to full-fledged Generality.

Whittle and Davidson are certainly not alone in this. See, e.g., (Armstrong, 1997, p. 202). An insightful exception to this consensus is (Makin, 2000), who acknowledges the important connection between laws of nature and causation for Anscombe. I believe the Anscombean account of laws of nature that I will develop and Makin’s account of the causal relation are compatible, and mutually reinforcing.

Davidson thus takes Anscombe to agree with expressions of skepticism about Generality such as the following: “Why must there always be a law to cover any causal relation linking events x and y?” (Sosa, 1984, p. 278), and “I do not think it a priori true, or even clearly a heuristic principle of science or reason, that causal relations must be backed by any particular kind of law.” (Burge, 1992, p. 35) Positions such as these are, I think, accurately described as singularist. Note that Generality is formulated more abstractly than the “cause-law thesis,” because I will soon argue that not every rejection of Singularism needs to follow the broadly Humean model that Davidson subscribes to.

Whittle (2003, pp. 373), for example, explicitly ascribes this argument to her when she portrays Anscombe’s reasoning like this: “Why should C causing E imply anything about other C-types causing E-types if, as [singularism] claims, C is the cause of E simply in virtue of local, intrinsic facts of the relation between C and E?” Davidson (1995, p. 265) also takes it that Anscombe’s rejection of Necessitation is grounded in her apparent rejection of Generality.

As Davidson (1995, p. 270) points out, epistemological singularism is compatible with the denial of singularism as defined above. I will briefly return to the question whether causality can be observed in single cases in §4.

Additionally, I argue against defenders of dispositionalism who believe that deterministic causation is impossible (Mumford & Anjum, 2014). On the Anscombean account I develop, it is false that all causation must be deterministic, but equally false that all causation must be indeterministic.

Including, e.g., proposals for hedged or ceteris paribus laws (discussed below), and views that differ from classical neo-Humean accounts with regard to the kinds of entities that are quantified over, such as (Armstrong, 1997). Even if these views attempt to resist certain aspects of traditional Humean accounts, from the Anscombean perspective these fail to distance themselves from the central feature of the latter (viz., the quantificational view of the generality of laws).

For instance, Lewis’s (1973)) counterfactual account, according to which causality requires the truth of the counterfactual that (roughly) e would not have occurred, had c not occurred. Even though this does not analyse causation as the instantiation of a law, it still makes the existence of causal relations dependent on laws of nature of the kind that I explain below: such laws are needed to define the set of possible worlds against which we evaluate the counterfactual.

Note that in this section, I am interested only in clarifying and criticising the logical form of Humean laws, and not in the question which true sentences of that form (i.e., which exceptionless generalizations) are, in fact, laws of nature. The question is a pressing one for the Humean, because there seems to be a difference between “accidental” universal regularities (e.g., there being no gold discs larger than a mile in diameter) and true laws of nature (see Van Fraassen, 1987, p. 27).

Davidson thus assumes that Anscombe must either accept his “cause-law thesis” (which he understands along the lines of Humean Generality) or accept Singularism. This is again symptomatic of a failure to see that one might provide a different, non-Humean articulation of the generality of laws of nature, while rejecting Singularism.

I disregard here two other arguments that Anscombe puts forward, at the beginning of her text. These relate to the epistemology of causation. First, there is the observation that “we often know a cause without knowing whether there is an exceptionless generalization of the kind envisaged” (Anscombe, 1971, p. 136), which is only offered as a prima facie consideration. Second, there is the related argument, against Hume, that we can in fact observe causation in the singular case. I disregard these because, as explained in fn. 6, neo-Humeans might accept such epistemological singularism. The latter argument, however, contains points that will become important in §4.

The most popular way of avoiding the problem of giving such a list is the idea to include ceteris paribus clauses in the laws. As is often pointed out, it is difficult to see how that does not boil down to saying that, e.g., “always, when a match is struck, it ignites, except when it doesn’t”—and thus collapse into vacuity. We will return to this point in §3. I cannot address the large literature on the problem of vacuity here.

Of course, I am not claiming that all Humean accounts must share Lewis’s exact metaphysics—only that a Humean account of causation must involve something that plays the functional role of Lewis’s mosaic. In Davidson’s ontology, for example, this role is played by the fundamentality of events, which are there to be quantified over.

See (Mulder, 2018) for an insightful statement of the argument that all broadly Humean accounts of laws require a commitment to something like Lewis’s mosaic.

What could it mean to say that a particular contains the generality of a law of nature, allowing it to be the source of its effects? As will become clear in the next section, I believe it is the concept of a power that fits this abstract description.

It might be thought that unlike a regularity account, a counterfactual account of causation (see fn. 9) avoids Anscombe’s complaints. A counterfactual analysis, after all, does not claim that the laws explain individual instances of causation. However, it is important to see that, given its reliance on the Humean mosaic, the counterfactual analysis still forgets about the derivativeness of the effect from the cause.

And that is indeed what, e.g., Whittle (2003, p. 372) seems to suggest when she puts forward that there might be “an irreducible causal necessitation trope.” The advantage of this proposal, according to Whittle, is that it might render true the idea that particular causal relations form part of larger regularities (laws of nature)—without the causal relationships obtaining in virtue of the regularities (see fn. 2). She believes tropes can achieve this because, although “tropes are spatiotemporal particulars” (and thus respectable from the point of view of broadly neo-Humean metaphysics) “sets of tropes form natural or genuine universals” (Whittle, 2003, p. 376). The details of Whittle’s account do not concern us here, but it nicely illustrates that the debate between singularists and anti-singularists is conducted on premises that Anscombe rejects.

As an anonymous referee points out, it is perhaps possible to imagine a form of singularism that rejects the Humean view of the generality of the laws of nature. Although I do not want to rule this out, it does seem to me that accepting an Anscombean account of that generality (which I develop below) would undermine a significant motivation for accepting singularism: the idea that the laws have no metaphysical bearing on what happens locally.

As opposed to, for example, artifact-kinds, or even agentive kinds (e.g., being a runner, as in the example below). Although these arguably do not constitute laws of nature, they still involve a non-quantificational form of generality similar to the one I will explain with regard to natural kinds below. I think it is plausible that laws of nature provide a paradigm for understanding such generality in the cases mentioned here, without taking a stand on the question whether, e.g., laws governing artifacts are reducible to laws of nature. It is an interesting question how, on this Anscombean picture, to understand merely physical powers such as inertia—which seems to belongs to objects precisely independently from belonging to a specific type of substance. I think there are broadly two approaches open to the Anscombean here: either we think of objects as bearers of a minimal or abstract kind such as mass-bearer, or we view mass as a power had by objects of (almost) all kinds—similar to the way in which, say, “walking” is a power had by animals of many different kinds. Clearly, much more needs to be said about in virtue of what objects possess such merely physical powers. But as Anscombe points out (Anscombe, 1971, p. 139), it will in any case not do to understand, e.g., the law of inertia in term of merely quantificational generality.

In fn. 39, I indicate in more detail an argument for the thesis that natural kinds or substance-forms are indispensable for ascribing powers to objects in nature, although the same caveats about powers such as inertia apply.

Hence Anscombe’s closing message: “The most neglected of the key topics in this subject are: interference and prevention.” As we will see in §4, this does not mean she equates the possibility of interference and the rejection of Necessitation.

I am suggesting that time-general statements relate to statements describing actual occurrences in the way in which statements ascribing dispositions relate to statements about manifestations. I thus do not think there is a fundamental difference between “iron melts at 1811 K” and “iron can melt at 1811 K”—as long as we are clear that the sense of the “can” is that of potentiality, which is to be distinguished from what I call possibility “on a particular occasion” below (§4). In this regard, statements ascribing indeterministic dispositions (for which again see §4) are not different from statements describing ordinary dispositions: as I see it, “radium can decay (spontaneously)” is equivalent to the time-general “radium decays (spontaneously).”.

Some examples of dispositional accounts include (Cartwright & Pemberton, 2013; Fischer, 2018; Mulder, 2021). Such dispositional accounts also have much to learn from Anscombe. We will see one example of this in the next section, concerning the relation between interference, prevention, and indeterminism. More importantly, however, Anscombe’s conception of laws provides dispositionalists with the ability to give more substance to the idea that “the dispositional modality” is sui generis, and not to be conceived of in terms of necessity or possibility, as some have already claimed (Mumford & Anjum, 2011).

Denying that there is room for this question is not to deny that we can inquire meaningfully into what explains the fact that the melting point of iron is 1811 K. The point is that for the Humean, there is a sense in which no explanation could make it anything but accidental. See §4.

This is complicated by the fact that some powers may be had not in virtue of their bearer’s nature: e.g., the human ability to speak a language. Here the generality of the time-general statement that humans speak languages seems distinct from the generality involved in a particular human’s ability to, say, speak English. The distinction reflects the fact that human abilities are acquired. This raises interesting questions about how to understand such abilities as a member of the genus “power,” of which natural powers are another species, which I cannot address here (but cf. (Mulder, 2021)). I thank an anonymous referee for bringing up this issue.

This is how I understand Anscombe’s (1971, p. 137) claim that “the word ‘cause’ can be added to a language in which are already represented many causal concepts.”.

Of course, if we focus on the exercise of a passive power—“the stone is being heated by the sun”—the stone precisely does not produce the effect. Rather, the stone is the site of the production which I take to be paradigmatic of causation. An account of the distinction between active and passive powers, and the way they jointly give rise to an effect, is beyond the scope of this paper.

See (Lowe 2008, chap. 6) for an argument that sentences about “substance causation” can always be translated into sentences about “event causation,” and vice-versa.

Recall that we already briefly encountered Kant as one of Anscombe’s targets in §2.

I am here thus distinguishing the logical possibility of interference or prevention from what has been called its real possibility at a certain place and time (Rumberg, 2020). The Anscombean understanding of indeterministic laws that I develop below is, I believe, especially suited as a metaphysical explanation of the formal notion of real possibility.

Teichmann (2008, p. 183) is right to emphasize this. But given my account in §3, it seems to me that he goes wrong when he suggests that (at least for Anscombe), a necessitating cause is “one mentioned in a ‘law of nature’” (Teichmann 2008, p. 183), while a non-necessitating cause is not. It is worth noting that the failure to appreciate the possibility of a dispositional account of the generality of laws—that the laws of nature might be like the laws of chess—leaves Teichmann without an understanding of what grounds “the range of antecedent possibilities” (Anscombe 1971, p. 141), more on which below.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pointing out the need to clarify the sense in which Generality applies to cases of indeterministic powers.

Although Makin (2000, p. 61) does not explicitly think of laws of nature as power-ascriptions, he similarly thinks of the laws as providing possible “routes” from one situation to another, and of causation as consisting in the actualization of one of these routes.

This is the epistemological sense of singularism mentioned in fn. 6.

I do not take a stand on the vexed question whether Kant’s transcendental argument actually establishes that we perceive causality, as opposed to merely revealing what would be true if we do.

Critique of Pure Reason B238-239, in the edition of Guyer & Wood (1999).

I already drew on Rödl’s account in explaining the non-Humean generality of laws of nature §(3), which he develop through the reading of Kant I explain here.

Roughly, the reason for this is that for there to be an objective fact concerning what a substance is doing, there must be something that determines what would count as prevention of the completion of the change: the change must have an “end” towards which it is underway, such that, e.g., the ship’s running into a sandbank counts as the prevention of what it was doing (floating downstream). Compare (Röd,l 2012, pp. 180–181).

It is of course difficult to explain what this experience of the general in the particular comes to: it cannot be that in order to see change, we must be aware of exactly which law of nature, or which power, is responsible for it. As my present topic is not the epistemology of causal powers, I will ignore these matters in what follows.

Also see (Watkins, 2004) for an influential argument that Kant’s conception of causality involves causal powers. It is interesting for our purposes that Watkins does not thematize the question why, if that is true, Kant assumes that Necessitation must be true. As I explain below, from the point of view of the Anscombean, that assumption looks like a confused remnant of Humeanism.

Note that the translation Anscombe (1971, p. 135) is using has “invariably” instead of “always.” Interestingly, there is a sense in which the Anscombean can of course agree that the laws of nature must be “invariable” (but not necessitating): the powers of a substance do not simply change from one moment to another. That the laws of nature are not themselves changeable is arguably a consequence of their generality. Compare (Watkins, 2004, p. 483), who suggests that Kant has similar reasons to believe the powers of substances cannot simply change at random.

I should clarify that Rödl himself does not thematize the topic of determinism or Necessitation. I am merely inquiring whether, if his reconstruction of Kant’s argument is correct, Kant’s seeming adherence to Necessitation is justified.

Anscombe (1971, p. 135) suggests that the reason why Kant is committed to Necessitation is that he tried to give back to that principle the objective (and a priori) justification that Hume had put into question, thereby in effect still importing a Humean dogma.

Does this mean commitment to Necessitation implies commitment to the broadly Humean conception of the generality of the laws of nature? I believe my argument shows that, first, commitment to the Anscombean conception of generality is incompatible with Necessitation, and second, that Necessitation and Humean Generality can form a consistent pair (but only provided that statistical laws are somehow ruled out). I do not wish take a stand on the question whether or not another conception of generality that would be compatible with Necessitation is possible. I thank an anonymous referee for raising this issue.

Anscombe herself argues for this claim in (Anscombe, 1974).

References

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1971). Causality and determination. In The collected philosophical papers of G.E.M. Anscombe, Vol. 2. Oxford University Press.

Anscombe, G. E. M. (1974). ’Whatever has a beginning of existence must have a cause: Hume’s argument exposed. Analysis, 34(5), 145–151.

Armstrong, D. M. (1997). A world of states of affairs. Cambridge University Press.

Burge, T. (1992). Philosophy of language and mind: 1950–1990. Philosophical Review, 101(1), 3.

Cartwright, N. and Pemberton, J. (2013). Aristotelian powers. In Powers and capacities in philosophy: The new aristotelianism, edited by J. Greco R. Groff, (pp 93–112). Routledge

Cartwright, N. (1983). How the laws of physics lie. Oxford University Press.

Davidson, D. (1995). Laws and cause. Dialectica, 49(2–4), 263–280.

Fischer, F. (2018). Natural laws as dispositions. De Gruyter.

Kant, I. (1999). Critique of pure reason. Edited by P. Guyer and A. W. Wood. Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. K. (1973). Counterfactuals. Springer.

Lewis, D. K. (1986). Philosophical papers II. Oxford University Press.

Lowe, E. J. (2008). Personal agency: The metaphysics of Mind and action. Oxford University Press.

Makin, S. (2000). Causality and derivativeness. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, 46, 59–71.

Mulder, J. M. (2018). The limits of humeanism. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 8(3), 671–687.

Mulder, J. M. (2021). Varieties of power. Axiomathes, 31(1), 35–61.

Mumford, S., & Anjum, R. L. (2011). Getting causes from powers. Oxford University Press.

Mumford, S., & Anjum, R. L. (2014). A new argument against compatibilism. Analysis, 1, 20–25.

Rödl, S. (2012). Categories of the temporal: An inquiry into the forms of the finite intellect. Harvard University Press.

Rumberg, A. (2020). Living in a world of possibilities: Real possibility, possible worlds, and branching time. In The metaphysics of time. Themes from prior., edited by P. Øhrstrøm, P. Hasle, D. Jakobsen. Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

Sosa, E. (1984). Mind-body interaction and supervenient causation. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 9(1), 271–281.

Teichmann, R. (2008). The philosophy of Elizabeth Anscombe. Oxford University Press.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1987). Armstrong on laws and probabilities. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 65(3), 243–260.

Watkins, E. (2004). Kant’s model of causality: Causal powers, laws, and Kant’s reply to hume. Journal of the History of Philosophy, 42(4), 449–488.

Whittle, A. (2003). Singularism. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 103, 371–380.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Vanessa Carr, James Conant, Rose Ryan Flinn, Alec Hinshelwood, Steven Methven, Niels van Miltenburg, Jesse Mulder, and Thomas Müller, as well as audiences at the universities of Konstanz and Leipzig, for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this paper. In addition, I would like to thank two anonymous referees for this journal for their generous comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article belongs to the topical collection “Causality and Determination, Powers and Agency: Anscombean Perspectives”, edited by Jesse M. Mulder, Dawa Ometto, Niels van Miltenburg, and Thomas Müller.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ometto, D. Causality and determination revisited. Synthese 199, 14993–15013 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03452-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03452-6