Abstract

If a speaker selflessly asserts that p, the speaker (1) has good evidence that p is true, (2) asserts that p on the basis of that evidence, but (3) does not believe that p. Selfless assertions are widely thought to be acceptable, and therefore to pose a threat to the Knowledge Norm of Assertion. Advocates for the Knowledge Norm tend to respond to this threat by arguing that there are no such things as selfless assertions. They argue that those who appear to be selfless asserters either: believe what they assert, perform a speech act other than assertion, or assert a proposition other than the one that they seem to. I argue that such counterarguments are unsuccessful. There really are selfless assertions. But I also argue that they are no threat to the Knowledge Norm. There is a good case to be made that knowledge does not require belief. And if it does not, then the fact that some selfless assertions are appropriate does not tell against the Knowledge Norm. Indeed, I argue that selfless asserters know the propositions that they assert to be true.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lackey does not say that p must be true, but in all of the thought experiments that she uses to illustrate selfless assertions, it either obviously is true, or else it is natural for readers to take it to be so. As my interest here is in the selflessness of selfless assertions, I will follow her lead. The Knowledge Norm must also, of course, be defended against arguments that purport to show that there are acceptable false assertions, but that is a project for another day.

The Knowledge Norm has many defenders, but Timothy Williamson is something of a standard bearer for the cause. See Williamson (2000, Chapter 11).

Cohen takes inferential knowledge to require acceptance, but holds that other kinds of knowledge do not. Lehrer argues that it is a condition on knowledge of every kind.

See Lackey (2007: pp. 598–600).

To be clear: I am not attributing this view to Turri. I am only speculating about ways in which his experiments might be relevant to the dispute about selfless assertions.

Some of Davidson’s work seems to suggest a principle of this sort. But the ‘interpretation’ that Turri’s subjects were engaged in is not similar to the attribution of a comprehensive set of interconnected beliefs and desires that Davidson has in mind.

On this point see Lackey (2017: p. 38).

It is true that this line of argument, like that in Sect. 2.2, involves denying one of Lackey’s stipulations. But it is plausible that the nature of the speech act performed can be read off of the vignette that Lackey provides, in a way that it is not plausible in the case of the mental state of the speaker. Hence it is plausible that Lackey’s stipulation that Stella asserts a proposition in her own voice is incompatible with Stella’s story, even though it is not plausible that her stipulation that Stella does not believe what she asserts is incompatible with it.

Engel suggests that those who suffer from self-deception can also be profitably seen in this way. See Engel (1998: p. 149).

To note their similarity is not to deny their differences. Engel does a good job summarizing the ways in which Lehrer and Cohen differ in their accounts of acceptance. (See Engel 2012: p. 19.) But the differences between their views will not be relevant to my argument and will be ignored below.

He does, however, have a complicated story to tell about the role of experience in shaping a system of justified acceptances. For the most recent formulation of this story, see Lehrer (2019).

Turri does not talk about acceptance, but he does suggest that a belief-like state, rather than belief itself, may be necessary for knowledge. (See Turri 2014: p. 194.)

It does not, as Lehrer would have it, ‘depend on any false statement’.

The following discussion about the nature of commitments, and the relationship between commitment and knowledge, draws heavily from Tebben (2019).

Beliefs, of course, play a role in folk psychology just as they do in psychology proper. But in each case, beliefs are adverted to as a means of explaining observable phenomena (behavior) in terms of unobservable phenomena (mental events).

Turri (2011) argues that one ought to assert a proposition only if, in so doing, one would express one’s knowledge of the proposition that one asserts. His arguments suggest that the Knowledge Norm, whichever reading it is given, is unsatisfactory. But notice that his view can also be given both a regulative and a truth-conditional reading, and that the same considerations surveyed here support giving it a truth conditional reading. If I assert the sentence ‘I am now asserting this sentence’, I express my knowledge that that is what I am doing, but I do not express any knowledge that I had prior to making that assertion.

Of course, General Brown engages in more than one speech act when promoting Smith. One of those speech acts effects the promotion. But he is surely also asserting that Smith is a Lieutenant. Consider that if Brown does not have the authority to promote Smith, he can be accused not just of issuing a misfiring performative speech act, but also of having said something that is false.

Drawing a distinction between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ propriety will not help support the Regulative Reading. (On this distinction see Williamson 1996: p. 493.) An assertion is proper in the secondary sense if the speaker has evidence that it is proper in the primary sense. But prior to asserting the sentence ‘I am now asserting this sentence’ the speaker does not have evidence that they know that it is true. Indeed, prior to asserting it, they know that it is false.

Brandom argues that to assert a proposition simply is to take up a commitment to it. (See his 1983 for an early statement of this view.) If, as Williamson holds, the Knowledge Norm is constitutive of the speech act of assertion (see his 2000), then Brandom’s view is in tension with the Knowledge Norm. (On this point see Shapiro 2018.) I would like to offer two responses to this observation. First, one need not, and probably ought not, take it that the Knowledge Norm is the constitutive norm of assertion. (See Kelp and Simion 2020.) Second, and more importantly, one can take it that when one asserts that p one thereby takes up a cognitive commitment to the proposition that p without agreeing with Brandom about the nature of assertions.

She may, of course, have been committed to it prior to asserting it. Perhaps willingness to assert a proposition commits one to it. But it suffices for this argument that asserting a proposition commits one to it, and so I will not discuss other means of commitment.

Notice, moreover, that nothing analogous to the problem of selfless asserters can arise if knowledge requires commitment rather than belief or acceptance. Since asserting a proposition is the paradigmatic way to take up a cognitive commitment, if p is true, one asserts that p, and one has good evidence for p (that is not connected to the fact of the matter in a deviant way), then one knows that p.

Notice that the argument that knowledge does not require belief is independent of any considerations concerning the norm of assertion, and so it is not question begging to assume that knowledge does not require belief as a part of an argument to the effect that one need not believe a proposition in order to properly assert it.

Consider Hawthorne and Stanley’s arguments in their 2008.

The Knowledge Norm specifies a necessary condition on proper assertion, but some (see Simion 2016, for example) suggest that knowing that a proposition is true is also sufficient for one’s assertion of that proposition to be permissible. Notice that if S knows that p does not entail that S believes that p, then an argument to the effect that properly asserting a proposition requires that one believe it also amounts to an argument against this stronger version of the Knowledge Norm.

Indeed, it is a distinction that is rarely drawn even by philosophers. Tebben (2018) explains why philosophers have largely failed to recognize the distinction between beliefs and commitments.

In connection with this point, see Baldwin’s work on Moore’s Paradox (Baldwin 2007).

Even if the proposition that they assert happens, by chance, to be true, they are still subject to criticism, if for no other reason than that they are attempting to violate the Knowledge Norm. (They are almost certainly also actually violating it, but that does not need to be shown in order to show that they are subject to criticism.).

References

Baldwin, T. (2007). The normative character of belief. In M. Green & N. Williams (Eds.), Moore’s paradox (pp. 90–116). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brandom, R. (1983). Asserting. Noûs, 17, 637–650.

Brandom, R. (2000). Articulating reasons: An introduction to inferentialism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cohen, L. J. (1989). Belief and acceptance. Mind, New Series, 98, 367–389.

DeRose, K. (2002). Assertion, knowledge, and context. The Philosophical Review, 111, 167–204.

Engel, P. (1998). Believing, holding true, and accepting. Philosophical Explorations: An International Journal for the Philosophy of Mind and Action, 1, 140–151.

Engel, P. (2008). In what sense is knowledge the norm of assertion? Grazier Philosophische Studien, 77, 99–113.

Engel, P. (2012). Trust and the doxastic family. Philosophical Studies, 161, 17–26.

Hawthorne, J., & Stanley, J. (2008). Knowledge and action. The Journal of Philosophy, 110, 571–590.

Kelp, C. (2018). Assertion: A function first account. Noûs, 52, 411–442.

Kelp, C., & Simion, M. (2017). Criticism and blame in action and assertion. Journal of Philosophy, 114, 76–93.

Kelp, C., & Simion, M. (2020). The C account of assertion: A negative result. Synthese, 197, 125–137.

Lackey, J. (2007). Norms of assertion. Noûs, 41, 594–626.

Lackey, J. (2017). Group assertion. Erkenntnis, 83, 21–42.

Lackey, J. (2019). Selfless assertions. In J. Meibauer (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of lying (pp. 244–251). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lehrer, K. (1990). Theory of knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge.

Lehrer, K. (2000). Belief and acceptance revisited. In P. Engel (Ed.), Believing and accepting (pp. 209–220). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Lehrer, K. (2019). Exemplars of truth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Milić, I. (2017). Against selfless assertions. Philosophical Studies, 174, 2277–2295.

Reynolds, S. L. (2013). Justification as the appearance of knowledge. Philosophical Studies, 163, 367–383.

Shah, N., & Velleman, D. (2005). Doxastic deliberation. The Philosophical Review, 114, 497–534.

Shapiro, L. (2018). Commitment accounts of assertion. In S. Goldberg (Ed.), Oxford handbook of assertion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simion, M. (2016). Assertion: Knowledge is enough. Synthese, 193, 3041–3056.

Tebben, N. (2018). Belief isn’t voluntary, but commitment is. Synthese, 195, 1163–1179.

Tebben, N. (2019). Knowledge requires commitment (instead of belief). Philosophical Studies, 176, 321–338.

Turri, J. (2011). The express knowledge account of assertion. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 89, 37–45.

Turri, J. (2014). You gotta believe. In C. Littlejohn & J. Turri (Eds.), Epistemic norms: New essays on action, belief, and assertion (pp. 193–200). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

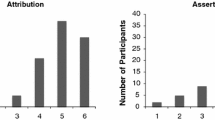

Turri, J. (2015). Selfless assertions: Some empirical evidence. Synthese, 192, 1221–1233.

Williamson, T. (1996). Knowing and asserting. The Philosophical Review, 105, 489–523.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tebben, N. Selfless assertions and the Knowledge Norm. Synthese 198, 11755–11774 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02827-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02827-5