Abstract

As conceived by Kim, the causal exclusion argument targets all forms of nonreductive physicalism equally, but by restricting its focus to functionalist varieties of nonreductivism, I am able to develop a version of the argument that has a number of virtues lacking in the original. First, the revised argument has no need for Kim’s causal exclusion principle, which many find dubious if not simply false. Second, the revised argument can be adapted to either a production-based conception of causation, as Kim himself favors, or to any of a number of dependence-based conceptions, like the ones favored by many of Kim’s critics. And, finally, the revised argument does not have the objectionable consequence that all so-called higher-level properties are epiphenomenal, for it does not generalize in the way that Kim’s original version of the argument arguably does. Nor does it concede much to narrow the scope of the argument in the way proposed. Those who adopt nonreductive theories of mind do so, by and large, on the strength of functionalist arguments for the multiple realizability of mental states. If functionalism entails that mental properties are epiphenomenal, this thus deals a critical, if not quite fatal, blow to nonreductivism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I will understand nonreductive physicalism to be the view that mental properties are irreducible. The arguments of this paper have application to other sorts of properties, but I will not pursue those applications here.

Árnadóttir and Crane, for example, argue persuasively that “the exclusion principle is contrary to our ordinary judgements about causation, has no strong independent defense, and ought to be rejected” (2013, p. 253).

As Baker (2009) observes, arguments for NRP derive either from Davidson’s (1980) case for anomalous monism or Putnam’s (1975) and Fodor’s (1974) functionalist arguments for the multiple realizability of mental states. Kim (1989b, p. 33) himself identifies Davidson and Fodor as his principal foils. But I think it’s fair to say that most contemporary defenders of NRP are motivated by functionalist considerations rather than the ones Davidson adduces. Kim, for example, argues that it was ‘chiefly’ Putnam’s multiple realizability argument that “helped to defeat reductive physicalism and install nonreductivism in its current influential position” (1993a, p. 341). And, as Kim often says, functionalism is more-or-less “the received position on the mind–body problem today” (1993b, p. 164). (See also Kim (2009, p. 46)). Many of the most recent discussions of NRP focus exclusively on the functionalist versions of the position and neglect even to mention Davidson’s—as in, for example, Shoemaker’s (2007, 2013).

Other examples of Kim giving the first version of the argument: (1993a, pp. 353–355), (1993b, pp. 168–170), (1997, pp. 285–287), (1998, pp. 37–47), (2003, pp. 157–158), (2005, pp. 41–45). Other examples of Kim giving the second: (1989a, p. 101), (2003, pp. 158–159), (2009, p. 39), (2011, pp. 214–217).

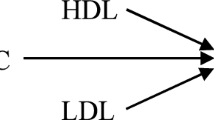

Kim’s full remarks suggest that he believes one of the problems is a special case of the other and that his ubiquitous exclusion diagram applies only to this special case. I agree and will argue for this below. Nevertheless, Kim does not seem to believe that this fact is significant.

Supervenience may be too weak a grounding relation for physicalism, but any adequate grounding relation will entail supervenience, and nothing stronger is required for the exclusion argument to proceed.

Some version of the first thesis appears in nearly all of Kim’s work on the exclusion argument. The second three theses are taken directly from Kim (2009, p. 38–39). The sixth is a slight variation. The fifth is the conclusion of what Kim sometimes calls ‘the supervenience argument’—as, for example, in Kim (2011, p. 219). I’ve made it more precise than Kim sometimes does. The formulation that comes closest to the one I give is found in Kim (1998, p. 42).

Kim’s argument for Supervenience appeals to the supervenience of nonphysical properties on physical properties and what he sometimes refers to as ‘Edward’s dictum’: “vertical [or supervenient] determination excludes horizontal [or causal] determination (Kim 2005, p 36). It’s also worth noting that an apparent absurdity can be derived even in the absence of Supervenience. If Kim’s arguments succeed in showing that the first five theses are inconsistent with Efficacy, they also show that the first four are inconsistent with Efficacy*, the thesis that some mental properties are causally efficacious with respect to physical properties. This too is an unwelcome consequence. Few defenders of NRP are willing to deny that some mental events cause physical events. (I grateful to a reviewer for suggesting that I make the assumption of Supervenience explicit here and elsewhere and contrast Efficacy with Efficacy*).

More precisely, B is a minimal supervenience base for some property F just in case B is a supervenience base for F and no proper part of B is.

I’m thankful to reviewer for insisting on these clarifications.

I’m following the presentation of the argument in Kim (2005). Other presentations of this version of the argument are not importantly different.

I am going to assume, with Kim, that events are the relata of the causal relation—more precisely, that events in the sense of Kim (1976) are the relata of the relation. Nothing important depends on this assumption. It is generally assumed that the causal exclusion argument can be run in terms of alternative relata.

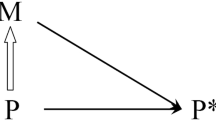

Kim takes causation to be “grounded in nomological sufficiency” (1998, p. 43). It’s sometimes unclear just what he means by this. For reasons I give below, nomological sufficiency can only be a necessary but not a sufficient condition for causal sufficiency. Thus when Kim says that M causes P* (or, equivalently, that M is causally sufficient for P*), we ought to interpret him as saying more than that M is nomologically sufficient for P*. I’ll have much more to say about this in Sect. 4.

Kim holds that ‘genuine overdetermination’ occurs only when “two or more separate or independent causal chains [intersect] at a common effect”—as when two bullets fell the same man—and that the supervenience of M on P rules this out (2005, p. 48). The two bullets are independent of one another because either could occur in the absence of the other, but M and P are not because P could not occur in the absence of M. Much more can (and has) been said about overdetermination and Kim’s understanding of it, but I won’t contest his definition, as it is irrelevant to the functional exclusion argument I offer below.

Kim (1998, pp. 44–45) cites two further reasons for rejecting the suggestion that M and P′ could be independent causes. First, this entails that every mental cause of an event is, in principle at least, dispensable, which is rather implausible. Second, if M and P′ are independent, M could occur in the absence of P′. But M is, by assumption, a sufficient cause of P*. It would thus appear that there is a nearby world in which P* has no physical cause, in violation of Closure.

Kim elsewhere suggests a more robust argument for (2.5), one that appeals to his causal inheritance principle: “If mental property M is realized in a system at t in virtue of physical realization base P, the causal powers of this instance of M are identical with the causal powers of P” (Kim 1993c, p. 326; italics omitted). With causal inheritance being assumed, an argument for (2.5) can be run as follows. Suppose that M causes P*. It follows from the causal inheritance principle that the causal powers of M are identical with those of its physical realization base PM. Thus M causes P* only if PM causes P*, from which it follows that PM = PC. Here we have a compelling argument for (2.5)—but one that, once again, presupposes mental causation and thus the truth of Efficacy. (I am grateful to a reviewer for encouraging me to make explicit the role that the causal inheritance principle plays in Kim’s argument.)

A reviewer asks how there can be two versions of the exclusion argument when the assumption that PM = PC is needed to ensure consistency with Efficacy, which is among the assumptions of the exclusion argument. But, as I argue below, the assumption that PM ≠ PC is needed to ensure consistency with role functionalism. So while it’s correct to say that there can only be one version of the exclusion argument because (2.5) is required for consistency with Efficacy, it’s also correct to say that there must be another version of the exclusion argument because the negation of (2.5) is required for consistency with role functionalism. Another contradiction! The point is that there is no way to maintain the global consistency of role functionalist versions of NRP—not, anyway, if NRP is committed to each of the five theses introduced above. The local consistency of (2.5) with Efficacy leads to a contradiction with functionalism; rejecting (2.5) ensures consistency with functionalism but contradicts Efficacy. I’ve chosen to derive the second contradiction because it allows me to make use of much of the framework of the original exclusion argument and because it highlights the fact that many of the responses to Kim make an assumption that is inconsistent with role functionalism.

List and Menzies, however, suggest that he does: “[Kim’s] argument invokes what he calls the exclusion principle: if a property F is causally sufficient for some effect G, then no distinct property F* that supervenes on F can be a cause of the effect G” (2009, p. 475).

Thus, despite the resemblance to Fodor’s (1974) famous ‘Special Sciences’ diagram, Fig. 2 represents a very different state of affairs. The various Ps in Fig. 2 represent parts of an event token; their analogues in Fodor’s diagram represent the different (complete) physical realizers of a multiply realizable event type.

This formulation is rough for a number of reasons, one of which is that if M causes things only in virtue of a proper part of its supervenience base, then, strictly speaking, M doesn’t cause things at all. More on this below. Note that the premise I refer to here is entailed by the conjunction of the principles I’m calling Parthood and Nonredundancy.

I’ll often drop the qualification from here on out and simply speak of ‘functionalism’ when I mean ‘role functionalism’. I will use the full title only when there is the possibility of confusion.

This is the standard definition of a functional state. See, e.g., Block (1978) and Shoemaker (1981). It is also Kim’s definition, found in his textbook introduction to functionalism (2011, p. 183) and his encyclopedia entry on the topic (2009, p. 46). Note that I will sometimes speak of ‘events’ and sometimes of ‘states’ in what follows. I do not believe that there are important philosophical differences between these notions, so I will choose one or the other based on stylistic considerations. It will be obvious when I mean to refer to a state or event token and when I mean to refer to a state or event type.

There are also various causal relations that must not obtain if C-fiber firing is to realize pain. If such a state were to be caused by innocuous as well as noxious stimuli, if it were as likely to attract a person to a stimulus as to repel her from it, it would surely be disqualified as a realizer of pain.

It would perhaps be more accurate to define M not in virtue of its ability to cause P* but to cause the more abstract state which is physically realized by P*—functional roles are rarely defined in terms of relations to physically individuated states. But recall that we are assuming the soundness of Kim’s supervenience argument, which purports to show that mental states can cause other mental states only by causing their physical supervenience bases.

Bartlett’s revision nicely illustrates the difficulties functionalism has with mental causation. He shows that if the functional role of, e.g., C-fibers can change in ways that do not affect their connection to various types of avoidance behavior, the cessation of pain might not be accompanied by a cessation of the behavior. One might, e.g., continue to howl in pain despite no longer being in pain. Bartlett, like Antony, takes this to be a reductio of functionalist theories of consciousness. In the course of making this argument, Bartlett defends a highly qualified form of the Parthood principle I introduce below.

This is so on the assumption that functional properties are at least partly constituted by causal roles. If R is empty, then there is no distinction between M’s core and its total realizer. But then M would occur whenever its core realizer occurred and no matter what causal role this core realizer happened to have, thus collapsing the distinction between properties that are and properties that are not constituted by their causal roles.

Note that the excitatory connection between P and P* is a nonredundant part of a nomologically sufficient condition for P*. It is also obvious that the occurrence of P* depends on the presence of the connection: if the connection weren’t present, P* wouldn’t occur.

In the course of defending a compatibilist solution to the exclusion problem, Bennett (2003) argues, using our terminology, that it is generally the case that M’s core realizer and the background conditions necessary for this core realizer to cause P* are identical to M’s total realizer. (Bennett (2008) appeals to the same argument). Keaton and Polger (2014) construct a counterexample showing that this will not always be the case. The claim I’m making is much stronger—namely, that it will almost never be the case. Interestingly, neither Bennet nor Keaton and Polger seem to realize just what’s at stake here. Keaton and Polger, for example, end their paper with the following, rather tepid conclusion: “If there is a compatibilist solution to the exclusion problem, we have not yet seen it” (p. 147). But it’s not simply Bennett’s version of a compatibilist solution that is threatened or even compatibilist solutions more generally. If the functional exclusion argument I present below is sound, there cannot be a functionalist solution—compatibilist or otherwise—to the exclusion argument. Note as well that Bennett defends a compatibilist approach to mental causation primarily in order to defang Exclusion, which is not a premise in the functional exclusion argument I offer below. Thus even if her defense of compatibilism were successful, it’s not clear that it would actually help to maintain the consistency of functionalist versions of NRP.

Parthood is inconsistent with (2.5) even though it does not rule out M or PM as causes. This is because the assumption of (2.5) is clearly meant to entail not only that M’s supervenience base is causally sufficient for P* but also that no proper part of it is. This is evidenced by, among other things, the use of Fig. 1 rather than Fig. 2 to represent the problem of mental causation. I’m grateful to a reviewer for requesting these clarifications to Parthood.

Such accounts appear far more defensible when one realizes that they are distinct from the regularity accounts with which they are so often associated. See, e.g., the discussion in Paul and Hall (2013, pp. 14–16).

This example is originally due to Salmon (1984) and is marshalled against the deductive-nomological model of explanation. Woodward (2008, pp. 229–230) repurposes it as an objection to Kim’s nomologically-based conception of causation. But this is unfair. As I explain in the text, causal sufficiency is not simply nomological sufficiency.

The problems I mention here are discussed in Paul and Hall (2013). A further problem concerns causation by omission, but I leave that aside as it doesn’t appear to favor Nonredundancy over minimal sufficiency accounts (or minimal sufficiency over Nonredundancy, for that matter).

Preemption: Two children throw rocks at a window, but the first one breaks it, allowing the second rock to sail right through. A set of events including the first throw but excluding the second is minimally sufficient for the effect, but so too is a set of events including the second and excluding the first. The second set is thus minimally sufficient for the effect but is not its cause. This is not a problem for Nonredundancy, however, for this principle has nothing to say about cases in which neither of two minimally sufficient sets is wholly contained within the other. Joint causation: Two children throw their rocks at time t, and each rock is thrown with sufficient force to shatter the window on its own. But the rocks collide at t + n, leaving them with just enough momentum to jointly cause the shattering of the window. There are now two minimally sufficient conditions for the effect—one for each unaccompanied throw at t—but neither is a cause of the shattering. This is no counterexample to Nonredundancy, though, for there is no time at which both an event and one of its proper parts is sufficient for the shattering. At t, each rock is part of a distinct set of sufficient conditions, but neither set is contained within the other. At t + n and times thereafter, there is a single set of sufficient conditions that includes both rocks as parts, but neither of these parts is sufficient for the effect.

Two careless smokers drop their cigarettes in a dry field. Either cigarette by itself would have been sufficient to start the blaze, and, let us pretend, the blaze would have been no different if either one of the cigarettes had been its sole cause. Intuition suggests that this is not a case of joint causation, for compare it to the case in which neither cigarette is sufficient to start the fire but the two together are. As such, it would be incorrect to say that the two events together cause the fire. And if the two events together do not cause the fire, Nonredundancy does not forbid us from saying that each does individually. This has some intuitive appeal, but, more importantly, it is what minimal sufficiency accounts say about such cases.

I am grateful to a reviewer for encouraging me to make these points more explicit.

Note that it’s nomologically and not just metaphysically possible for a proper part of PM to occur (and cause P*) in the absence of M. This is illustrated by our previous examples. It’s nomologically possible for pain’s core realizer (and the requisite background conditions) to occur and cause avoidance behavior in the absence of its total realizer, for example. More generally, it’s hard to make sense of the claim that a proper part of C is causally sufficient for E without thereby concluding that it’s nomologically possible for this proper part to exist and cause E in the absence of C—particularly so if one assumes that all causal relations are covered by laws.

A reviewer asks whether the revised exclusion argument is also required to assume something like Kim’s causal inheritance principle. The worry is that by ruling out PM as a cause of P* we have not yet ruled out M as a cause unless we also assume that M’s causal powers are identical to those of its physical supervenience base. I think, however, that Nonredundancy principle renders inheritance redundant. This is because Nonredundancy tells us that M cannot be causally sufficient for P* if either a proper part of M or a proper part of M’s supervenience base is causally sufficient for P*. I argued above for the inclusion of the italicized clause. If a proper part of M’s supervenience base were causally sufficient for P*, M itself would be redundant. P* would occur even in the absence of PM, which means it would occur even in the absence of M. M is thus not needed; it is not a minimally sufficient condition; it is not nonredundant. But then M cannot be the cause of P*. It is thus unnecessary to invoke the causal inheritance principle. Note as well that Kim does not need the causal inheritance principle in the context of his exclusion argument, for Exclusion rules out M as a possible cause of P* whenever P causes P*. Nonredundancy takes the place of Exclusion in the revised argument, so it is not surprising that it too makes appeal to causal inheritance unnecessary.

The assumption is that if P hadn’t occurred, M wouldn’t have occurred by means of some other realizer—that, in other words, the closest –P-worlds are also –M-worlds. This is counterintuitive. Indeed, it’s missed by Crane (2001, p. 61), from whom the argument originally derives. But the assumption is needed because without it the argument is fallacious. In fact, it’s an instance of a fallacy specifically discussed by Lewis (1973b, p. 32): −P>−P*/□(−M⊃−P)// −M>−P*. If the closest –P-worlds are closer than the closest –M-worlds, the premises can be true and the conclusion false. (Countermodel: @ > w1 > w2. At @: P = 1, P* = 1, M = 1. At w1: P = 0, P* = 0, M = 1. At w2: P = 0, P* = 1, M = 0. We’re assuming that P, P*, and M all occur in the actual world and wondering what would happen if M hadn’t occurred. We’re thus required to consult w2, which tells us that P* occurs in the closest –M-world(s). P* thus does not depend on M.) Adding the assumption that the closest –P-worlds are –M-worlds yields an instance of the following valid argument form: −P >−P*/□(−M⊃−P)/−P > −M// −M >−P*.

Note as well that according to the standard Lewisian semantics for counterfactuals, –M > –P* is true only if all of the closest –M-worlds are –P*-worlds. Thus, to show that P* depends upon M, the objector would have to show that all of the worlds in which M is eliminated by eliminating P are closer to actuality than any of the worlds in which M is eliminated by eliminating the causally superfluous bits of PM. This is a dubious proposition, but the objector might reasonably suggest that the burden is on me to prove it false. I’d prefer not to get bogged down in the quagmire of comparative similarity, so I offer a different and more principled response in the text.

It’s worth noting that M fails to meet other proposed necessary conditions for causal relevance. There is no chain of dependencies stretching from P* to M, as Lewis (1973a) requires; nor does M influence P*, as Lewis (2004) requires. List and Menzies (2009, p. 483) elevate counterfactual dependence to the status of a sufficient and necessary condition. As such, they must either invoke something like Loewer’s preemption principle, which rules out M as a cause of P*, or count obvious noncauses as causes. Crane’s (2001, p. 61) test of causal relevance faces the same difficulties.

Loewer is responding specifically to Kim (1998, pp. 67-72): “Kim’s main objection is that the counterfactual account doesn’t distinguish epiphenomenal relations from genuine causation. Let S1 be the location of the car’s shadow at t1 and S2 at t2 and C1 and C2 the corresponding locations of the car. The counterfactuals -S1 > -S2 and -S1 > -C2 may strike us as true though there is no causal relation between S1 and either S2 or C2” (2002, p. 659).

Though he doesn’t explicitly commit himself to a counterfactual theory of causation, Yablo defends a similar constraint, requiring that causes not be ‘screened off’ from their effects, where “C1 screens C2 off from E iff, had C1 occurred without C2, E would still have occurred” (1997, p. 266).

Woodward (2003, pp. 83–86) offers a modification of this definition, but this will be irrelevant for the argument that follows. Woodward’s amendment concerns the redundancy range of certain variables, and there are no redundancy ranges for the variables we will consider.

It’s important to acknowledge that these issues are the subject of much recent debate. Baumgartner (2009, 2010) argues that Woodward’s interventionism actually reinforces the conclusion of Kim’s exclusion argument. Woodward (2015, 2017) argues that Baumgartner’s argument rests on a flawed application of the interventionist test of causal relevance. And so on. It’s also a matter of debate whether there is a possible intervention on M that holds P fixed. (See Polger et al. (2018) for a dissenting opinion). I don’t mean to take a stand on this issue or on whether interventionism solves the exclusion problem for cases in which PM = PC. My contention is only that interventionism cannot solve the exclusion problem for cases in which PC is a proper part of PM. In such cases, neither PM nor M can be said to cause P*, as I argue below. (I’m grateful to a reviewer for requesting this clarification).

Which is not to say that the revised exclusion argument applies only to functionalist theories of the mind. Other higher-level properties seem to be analyzable into a core element and a surrounding element. A greenback isn’t legal tender outside of the appropriate institutional setting, but none of this seems causally relevant at the point of purchase. The United States may have ceased to exist, but the shopkeeper will still take your dollar if he doesn’t know. On the other hand, we’re not as deeply committed to the causal powers of currency as we are to those of the mind.

I’m assuming here that dispositional properties are intrinsic. It might be possible to conceive of functional properties as extrinsic dispositions. C-fiber firing realizes the same dispositional properties whether it is playing the role of pain in us or the role of mad pain in Lewis’s Martians, but it’s these relational properties that determine which mental state it realizes. If this interpretation can be maintained, then the important distinction is between intrinsic and extrinsic dispositional properties. I argue elsewhere (Rellihan, forthcoming) for the epiphenomenality of functional properties on the basis of their extrinsicness.

References

Antony, M. V. (1994). Against functionalist theories of consciousness. Mind and Language, 9(2), 105–123.

Árnadóttir, S., & Crane, T. (2013). There is no exclusion problem. In S. C. Gibb, E. J. Lowe, & R. D. Ingthorsson (Eds.), Mental causation and ontology (pp. 248–266). New York: Oxford.

Baker, L. R. (2009). Non-reductive materialism. In B. McLaughlin, A. Beckermann, & S. Walter (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of mind (pp. 109–127). New York: Oxford.

Bartlett, G. (2014). Against the necessity of functional roles for conscious experience: Reviving and revising a neglected argument. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 21, 33–53.

Baumgartner, M. (2009). Interventionist causal exclusion and non-reductive physicalism. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 23(2), 161–178.

Baumgartner, M. (2010). Interventionism and epiphenomenalism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 40, 359–383.

Bennett, K. (2003). Why the exclusion problem seems intractable and how, just maybe, to tract it. Nous, 37(3), 471–497.

Bennett, K. (2008). Exclusion again. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced (pp. 280–307). New York: Oxford.

Block, N. (1978). Troubles with functionalism. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 9, 261–325.

Clapp, L. (2001). Disjunctive properties: Multiple realizations. Journal of Philosophy, 98(3), 111–136.

Crane, T. (2001). The elements of mind. New York: Oxford.

Davidson, D. (1980). Mental events. In Essays on actions and events (pp. 207–224). New York: Oxford.

Fodor, J. (1974). Special sciences, or the disunity of science as a working hypothesis. Synthese, 28, 97–115.

Heil, J. (2013). Mental causation. In S. C. Gibb, E. J. Lowe, & R. D. Ingthorsson (Eds.), Mental causation and ontology (pp. 18–34). New York: Oxford.

Hume, D. (1777). Enquiries concerning human understanding and concerning the principles of morals. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Keaton, D., & Polger, T. (2014). Exclusion, still not tracted. Philosophical Studies, 171(1), 135–148.

Kim, J. (1976). Events as property exemplifications. In M. Brand & D. N. Walton (Eds.), Action theory (pp. 310–326). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Kim, J. (1989a). Mechanism, purpose, and explanatory exclusion. Philosophical Perspectives, 3, 77–108.

Kim, J. (1989b). The myth of nonreductive materialism. Proceedings and addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 63(3), 31–47.

Kim, J. (1993a). The nonreductivist’s troubles with mental causation. In Supervenience and mind (pp. 336–357). New York: Cambridge.

Kim, J. (1993b). Mental causation in a physical world. Philosophical Issues, 3, 157–176.

Kim, J. (1993c). Multiple realization and the metaphysics of reduction. In Supervenience and mind (pp. 309–335). New York: Cambridge.

Kim, J. (1997). Does the problem of mental causation generalize? Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 97(3), 281–297.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Kim, J. (2003). Blocking causal drainage and other maintenance chores with mental causation. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 67(1), 151–176.

Kim, J. (2005). Physicalism, or something near enough. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kim, J. (2009). Mental causation. In B. In McLaughlin, A. Beckermann, & S. Walter (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of mind (pp. 29–52). New York: Oxford.

Kim, J. (2011). Philosophy of mind. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Lewis, D. (1973a). Causation. Journal of Philosophy, 70(17), 556–567.

Lewis, D. (1973b). Counterfactuals. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1983). Mad pain and Martian pain. In Philosophical papers (Vol I, pp. 122–130). New York: Oxford.

Lewis, D. (1986). Postscript to ‘Causation’. In Philosophical papers (Vol. II, pp. 172–213). New York: Oxford.

Lewis, D. (2004). Causation as influence. In J. D. Collins, E. J. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 75–106). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

List, C., & Menzies, P. (2009). Nonreductive physicalism and the limits of the exclusion principle. Journal of Philosophy, 1006, 475–502.

Loewer, B. (2002). Review of mind in a physical world. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 65(3), 655–662.

Loewer, B. (2007). Mental causation or something near enough. In B. P. McLaughlin & J. Cohen (Eds.), Contemporary debates in philosophy of mind (pp. 243–264). Oxford: Blackwell.

Mackie, J. L. (1973). The cement of the universe. New York: Oxford.

Menzies, P. (2013). Mental causation in the physical world. In S. C. Gibb, E. J. Lowe, & R. D. Ingthorsson (Eds.), Mental causation and ontology (pp. 58–87). New York: Oxford.

Mill, J. S. (1843). A system of logic, ratiocinative and inductive. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Paul, L. A., & Hall, N. (2013). Causation: A user’s guide. New York: Oxford.

Polger, T. W., Shapiro, L. A., & Stern, R. (2018). In defense of interventionist solutions to exclusion. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 68, 51–57.

Putnam, H. (1975). The nature of mental states. In Mind, language, and reality (pp. 429–440). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rellihan, M. (forthcoming). Functional properties are epiphenomenal. Philosophia.

Salmon, W. (1984). Scientific explanation and the causal structure of the world. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shoemaker, S. (1981). Some varieties of functionalism. Philosophical Topics, 12(1), 93–119.

Shoemaker, S. (2001). Realization and mental causation. In C. Gillet & B. Lower (Eds.), The proceedings of the twentieth world congress of philosophy (pp. 23–33). New York: Cambridge.

Shoemaker, S. (2007). Physical realization. New York: Oxford.

Shoemaker, S. (2013). Physical realization without preemption. In S. C. Gibb, E. J. Lowe, & R. D. Ingthorsson (Eds.), Mental causation and ontology (pp. 35–57). New York: Oxford.

Strevens, M. (2007). Mackie remixed. In J. K. Campbell, M. O’Rourke, & H. Silverstein (Eds.), Causation and explanation (pp. 93–118). Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Wilson, J. (1999). How superduper does a physicalist supervenience need to be? Philosophical Quarterly, 49(194), 33–52.

Wilson, J. (2011). Non-reductive physicalism and the powers-based subset strategy. The Monist, 94(1), 121–154.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen. New York: Oxford.

Woodward, J. (2008). Mental causation and neural mechanisms. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced: New essays on reduction, explanation, and causation (pp. 218–262). New York: Oxford.

Woodward, J. (2015). Interventionism and causal exclusion. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 91(2), 303–347.

Woodward, J. (2017). Intervening in the exclusion argument. In H. Beebee, C. Hitchcock, & H. Price (Eds.), Making a difference (pp. 251–268). New York: Oxford.

Wright, R. (2013). The NESS account of natural causation: A response to criticisms. In M. Stephanians & B. Kahmen (Eds.), Critical essays on “causation and responsibility” (pp. 13–66). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Yablo, S. (1992). Mental causation. Philosophical Review, 101(2), 245–280.

Yablo, S. (1997). Wide causation. Philosophical Perspectives, 11, 251–281.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the audience of the 2018 Joint Session of the Aristotelian Society and Mind Association at the University of Oxford, and thanks again for the many helpful comments provided by the reviewers for this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rellihan, M. Strengthening the exclusion argument. Synthese 198, 6631–6659 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02481-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02481-6