Abstract

I extend theories of nonmonotonic reasoning to account for reasons allowing free choice. My approach works with a wide variety of approaches to nonmonotonic reasoning and explains the connection between reasons for kinds of action and reasons for actions or subkinds falling under them. I use an Anderson–Kanger reduction of reason statements, identifying key principles in the logic of reasons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This problem appears originally in Aristotle, who speaks “of the man who, though exceedingly hungry and thirsty, and both equally, yet being equidistant from food and drink, is therefore bound to stay where he is” (De Caelo II 13 295b32–35; Buridan comments on this passage in his unpublished Expositio Textus De Caelo, where his example concerns a dog (Rescher 1959, p. 154)). A version of the puzzle reappears in al-Ghazali, who summarizes the position of “the philosophers” (primarily Avicenna): “Indeed, if in front of a thirsty person there are two glasses of water that are similar in every respect in relation to his purpose [of wanting to drink], it would be impossible for him to take either\(\ldots \)” (Al-Ghazali 2000, I, 41, pp. 32–39). It appears most poetically in Dante: “Between two foods alike in appetite, and like afar, a free man, I suppose, would starve before either of them he would bite” (Paradiso III, Canto IV, quoted in Rescher 1959, p. 152). The fabled donkey first appears in the writings of Buridan’s critics.

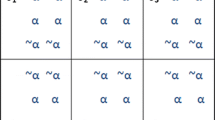

Mill’s formulation suggests another way to understand the distinction between perfect and imperfect obligations, as narrow-scope and wide-scope obligations, respectively. Where x is some person or action, perfect obligations have the form \(\exists x OA(x)\), and imperfect obligations have the form \(O \exists x A(x)\) (with no commitment to \( \exists x OA(x)\)). Assuming constant domains, \(\exists x OA(x)\) implies \(O \exists x A(x)\). But the reverse does not hold. So, the situation described can recur for any de dicto obligation, whether or not it would traditionally be considered imperfect.

Jonathan Dancy suggested the idea of applying Prichard’s question to reasons. The example is Buridan’s: “Debeo tibi denarium” (1977, p. 83).

In speech, we would normally express the thoughts leading to the puzzle by using emphasis: I have no reason to give you Blackie. This is not equivalent to the sentence without emphasis, for it sets up a contrast class (Rooth 1992).

Where the disjunction represents different epistemic possibilities rather than freedom to choose, in contrast, the disjunction or existential quantifier has wide scope. We can read I have reason to give you Blackie or Tawny—I’m not sure which as (I have reason to give you Blackie) or (I have reason to give you Tawny). Fox (2012, 2015) makes an analogous point with respect to imperatives; compare the two readings of Buy some teak or mahogany—whichever you prefer as opposed to whichever is in stock. See also Kaufmann (2012).

This framing ignores a limitation of Horty’s system, which relies on the default logic of Reiter (1980); a default such as \(A \rightarrow B\) never appears as the conclusion of an argument. Gelfond et al. (1991) and Brewka (1992) have investigated expanding default logic to allow defaults to be derived from other defaults. As Horty’s system stands, the equivalent point would be that, in a default theory with the single default \(A \rightarrow (B \vee C)\), the defaults \(A \rightarrow B\) and \(A \rightarrow C\) would be inadmissible; they could enlarge the set of consequences.

Assume for the sake of simplicity that each object in the domain has a constant in the language designating it.

Note that material implication and counterfactual conditionals violate (38)a, b, and c and so are not suitable candidates for this connective.

The most attractive accounts of nonmonotonic reasoning for my purpose are therefore based on pivotal valuation accounts (e.g., circumscription (McCarthy 1980; Lifschitz 1994), KLM (Kraus et al. 1990), or commonsense entailment (Asher 1995; Morreau 1997a)), since they automatically satisfy (40)b (Makinson 2005). Disjunctive Antecedents can however be added to theories based on pivotal rule accounts such as default logic (Reiter 1980; Horty 2012) or theories using maxfamily operations (Makinson and Torre 2000).

I am again abstracting away from a limitation of Horty’s system, since default logic, as Reiter and Horty develop it, is purely sentential. A natural quantificational extension, however, would make \(\forall x (A \leadsto B)\) and \(A \leadsto \forall x B\) equivalent, where x is not free in A.

It might seem more faithful to Cicero’s words to interpret him as saying something higher-order, familiar from Chisholm (1964), and interestingly elaborated in Rett (2016): If OA, then, for some B, B and B is a reason for A. On (41d), this becomes, if OA, then there is some B such that B and \(B | \!\!\!\approx A \leadsto \alpha \). But then, provided that \(OA, B | \!\!\!\approx A \leadsto \alpha \), OA defeasibly implies \(A \leadsto \alpha \). Presumably, if B is a reason for A, it doesn’t undermine A’s being a duty. Cutting out the intermediate step thus allows us to avoid higher-order quantification without any cost. I set aside here, incidentally, issues concerning the connection between reasons and motivational states. (See, e.g., Manne 2014).

This would again require extending H to include embedded defaults, as in Brewka (1992).

I am grateful to Jonathan Drake, Daniel Muñoz, and two anonymous referees for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. I have learned much from Jonathan Dancy; his reading of Prichard in a seminar on practical space inspired the paper’s central idea. I am also grateful to conference participants at Washington University, especially, Jonathan Kvanvig, whose comments on my talk helped to shape the paper. Finally, I owe thanks to the Classical Theism Project for supporting this work.

References

Abusch, D. (2004). On the temporal composition of infinitives. In J. Guéron & J. Lecarme (Eds.), The syntax of time (pp. 27–53). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Aczel, P., Israel, D., Katagiri, Y., & Peters, S. (Eds.). (1993). Situation theory and its applications (Vol. 3). Stanford: CSLI.

Al-Ghazali, I. (2000). The incoherence of the philosophers. (M. E. Marmura, Trans.). Provo: Brigham Young University Press.

Aloni, M. (2007). Free choice, modals and imperatives. Natural Language Semantics, 15, 65–94.

Alonso-Ovalle, L. (2006). Disjunction in alternative semantics. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Alvarez, M. (2010). Kinds of reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alvarez, M. (2016). Reasons for action, acting for reasons, and rationality. Synthese. doi:10.1007/s11229-015-1005-9, (pp. 1-18).

Anderson, A. R. (1956). The formal analysis of normative systems. In N. Rescher (Ed.), The logic of decision and action (pp. 147–213). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Anderson, A. R. (1958). A reduction of deontic logic to alethic modal logic. Mind, 67, 100–103.

Anderson, A. R. (1967). Some nasty problems in the formal logic of ethics. Noûs, 1, 345–360.

Anderson, A. R., & Belnap, N. D. (1975). Entailment: The logic of relevance and necessity (Vol. I). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Anglberger, A. J. J., Dong, H., & Roy, O. (2014). Open Reading without Free Choice. In F. Cariani, D. Grossi, J. Meheus, & X. Parent (Eds.), Deontic Logic and Normative Systems: 12th International Conference, DEON 2014, Ghent, Belgium, July 12–15, 2014: Proceedings (pp. 19–32). Heidelberg: Springer.

Anglberger, A. J. J., Gratzl, N., & Roy, Olivier. (2015). Obligation, free choice and the logic of weakest permission. Review of Symbolic Logic, 8(4), 807–827.

Antonelli, G. A. (2005). Grounded consequence for defeasible logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Åqvist, L. (1994). Deontic logic. In D. Gabbay & F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handbook of philosophical logic (Vol. II, pp. 605–714)., Extensions of classical logic Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Arieli, O., & Avron, A. (1998). The value of the four values. Artificial Intelligence, 102(1), 97–141.

Asher, N. (1995). Commonsense entailment: A logic for some conditionals. In G. Crocco, L. Farinas del Cerro, & A. Hertzig (Eds.), Conditionals in artificial intelligence (pp. 103–145). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Asher, N., & Bonevac, D. (1996). Prima facie obligation. Studia Logica, 57, 19–45.

Asher, N., & Bonevac, D. (1997). Common sense obligation. In D. Nute (Ed.), Defeasible deontic logic (pp. 159–203). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Asher, N., & Morreau, M. (1991). Commonsense entailment: A modal, nonmonotonic theory of reasoning. In J. Mylopoulos and R. Reiter (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twelfth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. San Mateo, Calif.: Morgan Kaufmann.

Asher, N., & Morreau, M. (1995). What some generic sentences mean. In J. Pelletier (Ed.), The generic book. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Asher, N. M., & Bonevac, D. (2005). Free choice permission is strong permission. Synthese, 145, 303–323.

Barker, C. (2010). Free choice permission as resource-sensitive reasoning. Semantics and Pragmatics, 3, 1–38.

Barwise, J., & Perry, J. (1983). Situations and attitudes. Cambridge: Bradford Books, MIT Press.

Belnap, N. D. (1977). A useful four-valued logic. In M. Dunn & G. Epstein (Eds.), Modern uses of multiple-valued logic (pp. 5–37). Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Bonevac, D. (1998). Against conditional obligation. Noûs, 32, 37–53.

Bonevac, D. (2016). Defaulting on reasons. Noûs, 50, 3. doi:10.1111/nous.12165.

Bresnan, J. (1972). Theory of complementation in english syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Brewka, G. (1992). A framework for cumulative default logics, Technical Report 92-042.

Brewka, G., Dix, J., & Konolige, K. (1997). Nonmonotonic reasoning. Stanford: CSLI.

Buridanus, J. (1977). Sophismata. Critical edition with an introduction by T. K. Scott. Stuttgart: Friedrich Frommann Verlag.

Buridan, J. (2001). Summulae de Dialectica. (G. Klima, Trans.). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cariani, F. (2017). Choice points for a modal theory of disjunction. Topoi, 36(1), 171–181.

Chellas, B. (1980). Modal logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, R. (1964). The ethics of requirement. American Philosophical Quarterly, 1(2), 147–153.

Chislenko, E. (2016). A solution for Buridan’s ass. Ethics, 126(2), 283–310.

Dancy, J. (2004). Ethics without principles. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Devlin, K. (2006). Situation theory and situation semantics. In D. M. Gabbay & J. Woods (Eds.), Handbook of the history of logic, 7 (pp. 601–664). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Dignum, F., Meyer, J.-J. C., & Wieringa, R. J. (1996). Free choice and contextually permitted actions. Studia Logica, 57(1), 193–220.

Duží, M., Jespersen, B., & Materna, P. (2010). Procedural semantics for hyperintensional logic: Foundations and applications for transparent intensional logic. Dordrecht: Springer.

Fine, K. (1994). Essence and modality. Philosophical Perspectives, 8, 1–16.

Fine, K. (2012). Guide to Ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), 2012, Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (pp. 37–80). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fine, K. (2014). Truth-maker semantics for intuitionistic logic. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 43(2), 549–577.

Fine, K. (forthcoming). Truthmaker semantics. In The Blackwell philosophy of language handbook.

Fitting, M. (1992). Many-valued non-monotonic modal logics. In A. Nerode & M. Taitslin (Eds.), Logical foundations of computer science-Tver ’92 (pp. 139–150). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Foot, P. (1978). Virtues and vices. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fox, C. (2012). Imperatives: A judgmental analysis. Handbook of Studia Logica, 100(4), 879–905.

Fox, C. (2015). The semantics of imperatives. In S. Lappin & C. Fox (Eds.), Handbook of contemporary semantic theory (pp. 314–342). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Fusco, M. (2014). Free choice permission and the counterfactuals of pragmatics. Linguistics and Philosophy, 37(4), 275–290.

Fusco, M. (2014). Factoring disjunction out of deontic modal puzzles. In F. Cariani, D. Grossi, J. Meheus, & X. Parent (Eds.), Deontic Logic and Normative Systems: 12th International Conference, DEON 2014, Ghent, Belgium, July 12–15, 2014: Proceedings (pp. 95–107). Heidelberg: Springer.

Gabbay, D. M. (1985). Theoretical foundations for non-monotonic reasoning in expert systems. In Logics and Models of Concurrent Systems, Volume 13 of the NATO ASI Series, (pp. 439–457).

Gelfond, M., Lifschitz, V., Przymusinska, H., & Truszczynski, M. (1991). Disjunctive defaults. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning: (pp. 230–237).

Geurts, B. (2005). Entertaining alternatives: Disjunctions as modals. Natural Language Semantics, 13, 383–410.

Ginsberg, M. L. (1987). Multi-valued logics. In M. L. Ginsberg (Ed.), Readings in nonmonotonic reasoning (pp. 251–258). Los Altos, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Ginsberg, M. L. (1988). Multivalued logics: A uniform approach to reasoning in AI. Computer Intelligence, 4, 256–316.

Ginzburg, J. (2012). The interactive stance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Givón, T. (1994). Irrealis and the subjunctive. Studies in Language, 18(2), 265–337.

Hawthorne, J. (1998). On the logic of nonmonotonic conditionals and conditional probabilities: Predicate logic. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 27(1), 1–34.

Horty, J. (1997). Nonmonotonic foundations for deontic logic. Nute, 1997, 17–44.

Horty, J. (2012). Reasons as defaults. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyman, J. (2015). Action, knowledge, and will. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kamp, J. A. W. (1973). Free choice permission. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 74, 57–74.

Kanger, S. (1971). 1957, 1971, New foundations for ethical theory. In R. Hilpinen (Ed.), Deontic logic: Introductory and systematic readings (pp. 36–58). Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Kaufmann, M. (2012). Interpreting imperatives. Berlin: Springer.

Kearns, S., & Star, D. (2008). Reasons: Explanations or evidence? Ethics, 118, 31–56.

Kearns, S., & Star, D. (2009). Reasons as evidence. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics 4 (pp. 215–42). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kleene, S. C. (1951). Introduction to metamathematics. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Koons, R. C. (2000). Realism regained. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koons, R. C. (2014). Defeasible reasoning. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/reasoning-defeasible/.

Kraus, S., Lehmann, D., & Magidor, M. (1990). Nonmonotonic reasoning, preferential models, and cumulative logics. Artificial Intelligence, 44, 167–207.

Krifka, M. (2012). Notes on Daakie (Port Vato): Sounds and modality. In Proceedings of AFLA 18 (2011). Cambridge: Harvard University. (pp. 46–65).

Krifka, M. (2016). Realis and Non-Realis Modalities in Daakie (Ambrym, Vanuatu). In Proceedings of SALT 26.

Kvanvig, J. (2005). Reasons and contrastive reasons. Certain Doubts, November 21, 2005, http://certaindoubts.com/reasons-and-contrastive-reasons/.

Kvanvig, J. (2006). Arbitrary actions and arbitrary beliefs. In Certain doubts, March 8, 2006, http://certaindoubts.com/arbitrary-actions-and-arbitrary-beliefs/.

Lifschitz, V. (1989). Benchmark problems for formal nonmonotonic reasoning. In M. Reinfrank, J. de Kleer, M. L. Ginsberg, & E. Sandewall (Eds.), Non-monotonic reasoning (pp. 202–219). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Lifschitz, V. (1994). Circumscription. In D. Gabbay, C. Hogger, and J. Robinson (Eds.) Handbook of logic in artificial intelligence and logic programming. Volume 3: Nonmonotonic reasoning and uncertain reasoning. Oxford: Clarendon.

Lord, E., & Maguire, B. (Eds.). (2016). Weighing reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Makinson, D. (2005). Bridges from classical to nonmonotonic logic. London: King’s College Publications.

Makinson, D., & van der Torre, L. (2000). Input/output logics. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 29, 383–408.

Manne, K. (2014). Internalism about reasons: Sad but true? Philosophical Studies, 167(1), 89–117.

Markovits, J. (2014). Moral reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCarthy, J. (1980). Circumscription–A form of non-monotonic reasoning. Artificial Intelligence, 13, 27–39.

Mill, J. S. (1861). Utilitarianism. London: Parker, Son and Bourn.

Morreau, M. (1997a). Fainthearted conditionals. The Journal of Philosophy, 94(4), 187–211.

Morreau, M. (1997b). Reasons to think and act. Nute, 1997, 139–158.

O’Neill, O. (1996). Towards justice and virtue: A constructive account of practical reasoning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Portner, P. (1992). Situation Theory and the semantics of propositional expressions. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Portner, P. (1997). The semantics of mood, complementation, and conversational force. Natural Language Semantics, 5, 167–212.

Prichard, H. A. (1932). Duty and Ignorance of Fact. Proceedings of the British Academy, reprinted in J. MacAdam (Ed.), H. A. Prichard: Moral Writings. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2002, (pp. 84–101).

Priest, G. (2008). An introduction to non-classical logic: From if to is. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1956). Quantifiers and propositional attitudes. The Journal of Philosophy, 53(5), 177–187.

Rainbolt, G. (2000). Perfect and imperfect obligations. Philosophical Studies, 98, 233–256.

Reiter, R. (1980). A logic for default reasoning. Artificial Intelligence, 13, 81–137.

Rescher, N. (1959). Choice without preference: A study of the history and of the logic of the problem of ‘Buridan’s ass. Kant-Studien, 51, 142–175.

Rescher, N. (1968). Many-valued logic. D. Reidel: D. Reidel.

Rett, J. (2016). On a shared property of deontic and epistemic modals. In N. Charlow & M. Chrisman (Eds.), Deontic modality (pp. 200–229). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rooth, M. (1992). A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics, 1(1), 75–116.

Santorio, P. (forthcoming). Alternatives and truthmakers in conditional semantics.

Seligman, J., & Moss, L. S. (2011). Situation theory. In J. F. A. K. van Benthem & A. ter Meulen (Eds.), Handbook of logic and language (pp. 253–328). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Setiya, K. (2014). What is a reason to act? Philosophical studies, 167, 221–235.

Snedegar, J. (2013). Contrastive reasons. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California.

Snedegar, J. (2014). Contrastive reasons and promotion. Ethics, 125(1), 39–63.

Snedegar, J. (2017). Contrastive reasons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

von Wright, G. H. (1951). Deontic logic. Mind, 60, 1–15.

Toulmin, S. (1950). Reason in ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wurmbrand, S. (2014). Tense and aspect in english infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry, 45(3), 403–447.

Zimmermann, T. E. (2000). Free choice disjunction and epistemic possibility. Natural Language Semantics, 8, 255–290.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonevac, D. Free choice reasons. Synthese 196, 735–760 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1540-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1540-7