Abstract

Published accounts of action research studies in healthcare frequently underreport the quality of the action research. These studies often lack the specificity and details needed to demonstrate the rationale for the selection of an action research approach and how the authors perceive the respective study to have met action research quality criteria. This lack contributes to a perception among academics, research funding agencies, clinicians and policy makers, that action research is ‘second class’ research. This article addresses the challenge of this perception by offering a bespoke checklist called a Quality Action Research Checklist (QuARC) for reporting action research studies and is based on a quality framework first published in this journal. This checklist, comprising four factors - context, quality of relationships, quality of the action research process itself and the dual outcomes, aims to encourage researchers to provide complete and transparent reporting and indirectly improve the rigor and quality of action research. In addition, the benefit of using a checklist and the challenges inherent in such application are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

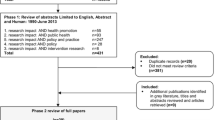

As action research grows in popularity, it becomes increasingly important to demonstrate how successful the process and the outcome of the research has been in publications. In a scoping review on the application of action research in the field of healthcare, we sought to assess the specific use of quality criteria as agreed in a scoping protocol (Casey et al. 2021). In accordance with our protocol, and our professional backgrounds we searched only for studies that used the action research methodology in the healthcare context. This included any professional healthcare provider, patient or recipient of healthcare products or services involved in action research. We noted that quality of the action research was underreported, and we surmise that this may also be the case in other contexts.

We found that many studies often lacked the specificity and details needed to communicate the context, quality of relationships, quality of the action research process itself or the dual outcomes, with enough precision, accuracy and thoroughness to allow readers to assess the design, execution of the work and the contribution to actionable knowledge. In our view, this leads to a perception among academics, research funding agencies, clinicians and policy makers, that action research is ‘second class’ research and that ‘anyone with common sense’ can do it. Action research has been viewed with scepticism and criticised on the basis of being subjective, anecdotal, unscientific, and not reproducible or generalisable. Indeed, Levin (2003:280) suggests “there are many powerful players in the scientific world who find action research offensive and illegitimate” and this directly relates to the lack of overt demonstration of scientific rigor or quality. This has culminated in lower priority for publication, a lack of appreciation and a dearth of action research particularly within the medical literature, in view of a perception of its limited applicability to clinical practice and limited citation counts.

In our experience, there is no doubt that a lack of adherence to reporting guidelines contributes to research waste, possibly limiting the applicability and transferability of research findings to other settings. Hence a bespoke checklist such as a Quality Action Research Checklist (QuARC) provides a framework for reporting action research studies. Developing a checklist such as QuARC is intended to promote the quality of reporting of action research studies. While we are not suggesting this checklist be mandatory, we believe that its application will lead to improved conduct, and greater recognition of action research as an acceptable scientific endeavour. As action research in healthcare becomes more established (Casey et al. 2021), adherence to the QuARC should be encouraged to ensure transparent reporting, in order to influence and create theory as well as delivery of care, policy and clinical practice. While there are a number of quality criteria for action research available, and this article builds on a framework first published in this journal (Coghlan & Shani 2014) and draws on these criteria and on the analysis of a scoping review protocol (Casey et al. 2021) to create a Quality Action Research Checklist (QuARC). We propose that this checklist might actually improve action research and the quality of outcomes if reported. By providing this information on action research studies, QuARC might facilitate the ongoing discussions by providing factual data on both the use of checklists, and the completeness of reporting. We encourage readers to comment on QuARC so that a more responsive and acceptable checklist may be provided.

Background

Action research is distinguished from other forms of research by its dynamic process of changing and producing knowledge that takes place in the present tense and where the data emerges through intervention and reflection-in-action and it aims at contributing to both practice and theory. Action research may be defined as.

… an emergent inquiry process in which applied behavioural science knowledge is integrated with existing organizational knowledge and applied to address real organizational issues. It is simultaneously concerned with bringing about change in organizations, in developing self-help competencies in organizational members and in adding to scientific knowledge. Finally, it is an evolving process that is undertaken in a spirit of collaboration and co-inquiry (Coghlan & Shani 2018: 4).

Therefore, action research has a dual intention. The action intention aims to address a practical concern of individuals, groups, organisation or communities. The research intention aims to generate practical or actionable knowledge for use beyond the immediacy of the specific situation. This combination of action and research in a single paradigm distinguishes action research philosophically from those forms of research that focus on generating knowledge only. Action research studies that are not adequately reported on all aspects such as both the action and research intentions can lead subsequent researchers to inappropriately apply the research in a different context giving rise to doubts about the scientific value of the approach.

Guidelines and checklists are an important connection between the completion of a study and the sharing of the outcomes, recommendations and conclusions with the others. As one approach, a checklist can provide a structure for the reporting and it should be brief. Formal reporting guidelines have been developed for a whole range of different study types. Some examples are the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT), or guidelines for systematic reviews Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), observational studies (STROBE) and check lists for study protocols (SPIRIT), a checklist for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) and SQUIRE is a checklist for quality improvement studies to name but a few. Such checklists help to improve the reporting these types of study and allow a better knowledge and understanding of the design, conduct, analysis and findings of published works. Moreover, using these checklists in practice enables those who use published research to have more insight into the approach itself and therefore better able to critique published work and to decide its applicability to their local contexts. Checklists may also provide a guide for researchers during a study to enable them to keep focus and to attend to how quality dimensions are present in the design and implementation of the study.

Arising out of a recommendation from our scoping review protocol (Casey et al. 2021) the need for a checklist to address the quality issues of action research was apparent. In many instances the qualitative checklists such as the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ), had been used and suggested for use in some instances by editorial criteria. Understandably this is in the absence of any specific action research checklist. A recent replication of the development of the COREQ (Buus and Perron 2020) found that it was not itself trustworthy or credible and not based on a systematic, credible and rigorous synthesis of previous checklists. The lack of formally agreed guidelines for action research is surely a contributing factor to the underreporting of the quality or the rigor in action research. An over emphasis on the part of the researchers and funders on finding a practical solution and forgetting considerations of future learning may also be an issue and finally, there is some responsibility resting with word count limits imposed by different peer-reviewed journals which might explain the suboptimal reporting in action research studies. This can be particularly problematic especially if lengthy quotations typical contribute to word count and if the detailed consideration of quality issues is parked in favour of emphasis on results, while acknowledging that some journals do create the opportunity to provide additional supplementary material. With the increasing use of open access and electronic-only publications these constraints might well reduce with time. However, regardless of the publication format used, something, such as checklist or guideline is needed to encourage researchers to address the quality of their action research studies.

The Rationale for Developing a Checklist for Action Research

As academics, researchers, editors, reviewers attempt to strengthen the knowledge base and demonstrate scientific research principles they increasingly rely on the use of well-established reporting guidelines. That said, we acknowledge there is no empirical basis that shows that the introduction of a checklist for action research studies will improve the quality of reporting of action research. However this also holds true in relation to introducing and indeed using other reporting checklists. However, research has shown that these checklists have improved the quality of reporting of some study types (Moher et al. 2001; Delaney et al. 2005). In a recent meta review study de Jong et al. (2021), found that reporting quality improved following the COREQ publication with 13 of the 32 questions showing improvement. We believe that the effect of QuARC is likely to be similar. Realising that, in contrast to most other research fields, no widely used comprehensive checklist, nor uniform and accepted requirements for publication of action research exist, we aim to design a checklist for quality in action research. QuARC is not intended to be regarded as a mandatory set of requirements. Rather, we emphasise its utility as a guide to draw the attention of the authors of action research papers about some important choices to be considered. This applies both to how research is designed and implemented, and how it is reported. This will encourage more detailed and transparent reporting and therefore help to improve the rigor and quality of action research. Moreover, we believe that the contribution of QuARC will be greatest for an author when it is consulted throughout a study, and then again when checking that the final publication sufficiently addresses research quality.

Nevertheless it can be a matter of personal proclivity as to the value of checklist and whether or not articles should be scored instead of being appraised in a descriptive way. In some instances, a checklist for action research may be seen as being reductionist and an antithesis to the whole philosophical underpinning of action research as an approach. Checklists can also be seen as an attempt to legitimize action research through the development and dissemination of a bespoke checklists mimicking influential quantitative health research, which is oriented to measurement and objectivity. According to Buus and Perron (2020) checklists can de-politicise research and create an illusion of rationality and objectivity. However, the use of a checklists might be beneficial for new or inexperienced researchers designing an action study. Checklists may guide those unfamiliar with action research with hints and directions to avoid commonly made mistakes. The same holds true for reviewers assessing an action research study for publication, particularly if the reviewer has content expertise but not methodological expertise in this area. In the context of practitioners, where action research has a growing audience, the potential impact on patient care and clinical practice demands that the strongest possible evidence is provided on whether the particular change or improvement intervention works. Hence, the dual focus of action research on action and theory generation makes the study and reporting of work in action research extremely challenging, particularly for the many “frontline” healthcare professionals who are implementing improvement programmes.

The COREQ was first published in 2007 and consists of 32 items that are mostly used for interviews and focus groups. The checklist is grouped into three domains (research team and reflexivity, study design and data analysis, and reporting), thus creating a comprehensive checklist covering the main aspects of a qualitative study design which should be reported. The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) was first published in 2008. The current reporting quality guideline for Quality Improvement (QI) studies is SQUIRE 2.0, published in 2015, SQUIRE 2.0 is intended for any study that reports on systematic, data-driven efforts to improve the quality, safety and value of healthcare. The SQUIRE checklist consists of a checklist of 19 items that need to be considered when undertaking and writing studies of quality improvement initiatives. Most of the items in the checklist are common to all scientific reporting. As QI studies may use a variety of intervention steps, such as iterative Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles, Lean six sigma and Total Quality management, and action research steps, the SQUIRE guidelines may have been deemed appropriate. However, the applicability of SQUIRE 2.0 depends on a study’s objectives, rather than its design; namely, that the study sought to report on a systematic effort to improve the quality, safety and value of healthcare at a systems-level. Both the COREQ and SQUIRE are now included in the EQUATOR network and are required by many clinical journals for submission. Table 1 provides an outline of the main content of these two checklists.

Uses of Checklists for Designing and Evaluating Research

The purpose of a checklist for action research is to (a) help researchers to design rigorous action research studies (b) assist researchers in reporting their studies in sufficient detail, (c) assist academic and future users in evaluating the methodological rigor of a published study, and (d) assist readers in evaluating the comprehensiveness of a report of a study. From our experience and having completed a preliminary review of the literature there is a paucity of studies examining the credibility and outcomes of using checklists for planning, reporting or evaluating action research studies. Sandelowski and Barroso (2002), examined the role that checklists play, and asked a panel of very experienced qualitative researchers to review the same papers using a qualitative guide. They concluded that there was no consensus between experienced reviewers. More recently, Sandelowski (2015) suggested that reviewers do not simply apply a set of criteria, but also select and use knowledge and prior experiences when they engage with a research report. Sandelowski (2015) suggested that reviewers of quality develop a kind of intangible aesthetic appreciation of what constitutes ‘good’ or ‘bad’ research practice for different kinds of approaches. They argue that because of a reviewer’s particular knowledge and embodied perspective on research practices, knowledge from an evaluation is negotiated and situated, and procedural transparency impossible. In this context, the use of a checklist could enhance the reviewer’s attempts to provide transparency and quality. Like Sandelowski (2015) who cautioned against the idea that a checklist can be comprehensively developed to cover all aspects of quality and is more likely to result in emphasising the technical and procedural aspects of the research, it may be argued that judging rigor and quality of action research studies is essentially a subjective exercise which may only be potentially enhanced by the use of a checklist. Indeed, the use of a checklist can lead reviewers to claim levels of credibility without considering the limitations of the particular tool in use. In some ways a checklist can position scholars as more legitimate than others whilst its non-use may inhibit access to publication and prevent access to the findings being used by other researchers or policy makers while also affecting the authors research careers. In this way checklists can be a social technology where the use or non-use of the checklist helps legitimise the project and the academic work. It is important therefore to consider that checklists are not politically neutral therefore it is incumbent upon developers to bring such reflections into a more open and transparent dialogue about generation of knowledge underpinning the checklist and to invite critique and comment. This article proposes to make the development process of the QuARC checklist transparent and replicable.

Data Sources

The strategies discussed are based on our own experiences and the supporting literature on quality and rigor in action research. There are many ways to develop a checklist such as based on consensus statements from expert groups. Another way is to use Delphi techniques or systematic literature reviews and another way is to identify and amalgamate items from previous checklists into more comprehensive, consolidated ones (Buus and Perron 2020). This latter approach is used in this paper combined with expertise of the authors.

Discussion

Developing a Quality Action Research Checklist (QuARC)

According to Hammersley (2007) items on a checklist may be operationalised as criteria or guidelines. “Criteria are standardised and observable indicators that are explained so that reviewers can use them with little error and with high inter-reviewer reliability. Using a valid list of criteria should comprehensively inform reviewers whether something is present, valid or of value” (Buus and Perron 2020:6). This suggests that guidelines could be more loosely interpreted depending on the reviewer’s or author’s skills rather than on the application of a standardised item. There are several action research quality frameworks published in the form of discussions and suggested questions such as Eden and Huxham (1996) and Bradbury-Huang, (2010) or core factors Coghlan and Shani (2014, 2018). We employed the latter in our scoping review protocol (Casey et al. 2021) as, in our view, it provides a comprehensive framework that expresses the relationships between context, quality of relationships, quality of the action process as well as concern for outcomes such as the actionability and contribution to knowledge creation. We used it again here as the basis of the QuARC.

Coghlan and Shani (2014, 2018) present an action research framework, based on a comprehensive review, analysis and synthesis of published literature and a set of empirical field studies in a variety of organizations. It has four factors; context, quality of relationships, quality of the action research process itself and outcomes.

-

Context: As action research generates localised theory through localised action knowledge of context is critical. The context of the action refers to the external business, social and academic environment and to the internal local organizational/discipline environment of a given organization. Knowledge of the scholarly context of prior research in the field of the particular action proposed and to which a contribution is intended is also a prerequisite.

-

Quality of relationships: The quality of relationship between members and between members and researchers are paramount. Hence the relationships need to be managed through building trust, concern for the other, facilitating honest conversations, equality of influence in designing, implementing, evaluating the action and cogenerating the emergent practical knowledge.

-

Quality of the action research process itself: The quality of the action research process is grounded in the intertwining dual focus on both the action and the inquiry processes as they are enacted in the present tense. The inquiry process is systematic, rigorous and reflective such that it enables members of the organization to develop a deeper level understanding and meaning of a critical issue or phenomenon.

-

Outcomes: The dual outcomes of action research are some level of sustainability (human, social, economic, ecological) and the development of self-help and competencies out of the action. Support for social change may also generate outcomes that “foster practice and political transformation at the micro or macro levels” (Cordeiro and Soares 2018:1016) and the creation of new knowledge from the inquiry.

These four factors comprise a comprehensive framework as they capture the core of action research and the complex cause-and-effect dynamics within each factor and between factors. They provide a unifying lens into wide variety of the reported studies in the literature, whether or not the factors are discussed explicitly and a high-level guide for the action researcher. The framework allows the distinct nature of each action research effort to emerge and it consolidates the added value of each study. It stands up to the challenges of action research values, design, implementation and evaluation, teaching and doctoral examination (Coghlan et al. 2019).

The Four Factors as Quality Criteria

Coghlan and Shani (2014) propose that good action research may be judged in terms of the four factors introduced above: how the context is assessed, the quality of collaborative relationships between researchers and members of the system, the quality of the action research process itself as cycles of action and reflection are enacted and how the dual outcomes reflect some level of sustainability (human, social, economic and ecological), and the creation of new knowledge from the inquiry. This article draws on these four factors to create a checklist to assist action researchers, editors and examiners to judge the quality of an action piece of work. Table 2 provides a sample of questions which may be posed to an action research account. It is intended that the questions focus attention on both action and research.

Context

Context sets the stage for action research. By context is meant that the setting that precedes and follows an action research initiative is influencing it. It is within a context that issues/challenges/problems that action research seeks to address arise. It is said that action research is conducted on issues people care about. What people care about lies within an external and internal context. Externally, there is a global context of socio-economic inequality, poverty, famine, the displacement of peoples from their homeland, the destruction of the environment. That list is extensive. These may occur and have an effect in a local context where there are challenges for social services, education, housing, community and so on. Internally, within an organizational setting - service delivery, organising, resourcing, staffing, climate, skill development may be drivers of organizational change and of inquiry. For researchers there is an academic context to each of these in how previous researchers, particularly action researchers, have investigated the issue. Accordingly, a quality requirement of an action research initiative is how well it demonstrates its foundation in both the practical and academic contexts.

Quality of Relationships

A common action research caption/slogan is that action research is research with people, rather than on or for them. Research with is probably the most significant characteristic of action research and is created by the context. According to Cordiero and Soares (2018: 1016) “democratic processes that engage participants from the beginning tend to result in more substantial changes and may improve the quality of the action research”. Therefore, within this participatory paradigm there are fundamental questions to be asked about the quality of relationship and between members and researchers. Accordingly, a quality requirement of an action research initiative is how well it demonstrates the quality of collaboration in how the project was codesigned, jointly implemented and evaluated and how the emergent practical knowledge was cogenerated.

Quality of the Action Research Process

The quality of the action research process is grounded in the intertwining dual focus on both the action and the inquiry processes and is influenced by the quality of relationships. The commonly expressed action research cycles express how the process is iterative and learning and knowledge production is emergent, that is, they emerge through the iterations of the collaborative engagement in constructing the issue, in planning, in implementing, in evaluating, in framing the learning and articulating the knowledge generated. Accordingly, reasoning is abductive as puzzles and anomalies are caught and questioned. These processes take place in the present tense, and it is through being attentive and questioning as the process unfolds that learning and knowledge emerges. The action process focuses on addressing the practical issue and may benefit from project management or change processes methods. The inquiry process is systematic, rigorous, reflective and resilient such that it enables members of the organization to develop a deeper level understanding and meaning of a critical issue or phenomenon. In this process tools of rigorous analysis from qualitative methods may be useful. Accordingly, a quality requirement of an action research initiative is how well it engages in the cycles of action and reflection as they unfolded and how the outcomes are transparent from these processes.

Outcomes

The dual outcomes of action research are some level of sustainability (human, social, economic, ecological) and the creation of new knowledge from the action and inquiry. What is often problematic about accounts of action research is that the action outcomes are described with the benefits to the system articulated but the contribution to knowledge for those who were not directly involved is minimised or even omitted. This is the loop back to the context. The action research initiative is a response to issues in the context – both the practical context of needed action and the academic context of practical knowledge. The dual outcomes then become part of the context for future action and research.

Implications for Research in Healthcare

As the scoping review focused on the application of action research in the field of healthcare, we reflect on the implications of QuARC for the field of healthcare, not denying its applicability to other fields. Healthcare scholars engaging in action research projects can use this checklist regularly to evaluate the quality of their research thereby assisting organisational managers in proposing workable solutions. Furthermore, these strategies allow healthcare scholars to conduct rigorous, in-depth action research without geographic limitations, providing greater possibilities for international collaborations and cross-institution research well beyond the current context.

What then might be the implications for action researchers, research supervisors and journal editors and reviewers? As a concrete way of enacting QuARC, Shani and Coghlan (2021) in a reflective review of action research in the field of business and management invited readers to engage in their own reflection on their judgements in reading accounts of action research in terms of the four factors. They posed the following questions.

-

1.

With regard to the presentation of context, how might you judge that contextual data are captured in a rigorous, systematic manner so that the rationale for the action and the research is solidly grounded? How might you be satisfied that the action research builds on both the organisation’s experience and on previous research? Related to this is what we consider to be best research practice to provide a rationale or justification for the selection of the particular research approach, in this case that of action research.

-

2.

Is there an explicit discussion of how the action research relationships were formed, built and sustained, with an account of enablers, obstacles and difficulties that may have arisen? Is the work evaluated in terms of the quality of the relationships? How might you judge that the quality of relationships meet a standard of collaborative endeavour that action research espouses?

-

3.

Does the account demonstrate a rigorous and collaborative engagement in the action research project’s design, and subsequent enactment of cycles of planning, taking action and reflection so that the path to the organizational and theoretical outcomes are transparent? How might you weigh the action research account to your satisfaction?

-

4.

Are both forms of outcomes presented? To what extent are they humanly, socially, economically and ecologically sustainable? How is organizational learning demonstrated? What actionable knowledge has been cogenerated? What are your criteria for actionable knowledge?

We invite readers of this article to pose similar questions. The strategies we are presenting are drawn from our singular experience, although they are supported by other scholars’ past efforts to conduct rigorous action research (Eden and Huxham 1996; Morrison and Lifford 2001; Bradbury-Huang 2010, 2020; Casey and Coghlan 2021). In the future, systematic exploration of the impact of using QuARC checklist on the quality of action research inquiry would add to the growing body of literature on the quality of action research which is currently almost solely based on case exemplars. Scholars motivated to explore this topic should consider using the QuARC tool to explore their research aims and questions; this approach would allow the scholar to more clearly demonstrate the quality of their action research project work. The researcher would need to carefully document their processes and procedures, perhaps through the use of detailed methodological memos.

Conclusion

In this article we have made the case that in the context of a general underreporting of quality criteria in action research accounts, the provision of a checklist is of practical value. QuARC provides action researchers in nursing, midwifery and healthcare as well as research supervisors, reviewers and journal editors with a framework for assessing both the quality of a particular action research initiative and of its presented account for publication. QuARC is designed to enhance the quality of how action research initiatives are reported, which will indirectly lead to improved conduct, and greater recognition of action research as a justifiable scientific endeavour.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bradbury-Huang H (2010) What is good action research: why the resurgent interest? Action Res 8(11):93–109

Bradbury-Huang H (2020) Action methods for faster transformation; relationality in action. Action Res 18(3):273–281

Buus N, Perron A (2020) The quality of quality criteria: replication of the development of the Consolidated Criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ). Int J Nurs Stud 102:1–7

Casey M, Coghlan D (2021) Action research - for practitioners and researchers. In: Crossman J, Bordia S (eds) Handbook of qualitative research methodologies in workplace contexts. Edward Elgar, pp 67–81

Casey M, Coghlan D, Carroll A, Stokes D, Roberts K, Hynes G (2021) Application of action research in the field of healthcare. A scoping review protocol. HRB Open Research 4:46. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13276.2

Coghlan D, Coughlan P, Shani AB, Rami (2019) Exploring doctorateness in insider action research. Int J Action Res 15(1):47–61

Coghlan D, Shani, AB (Rami) (2014) Creating action research quality in organization development: Rigorous, reflective and relevant. Systemic Pract Action Res 27:523–536

Coghlan D, Shani AB (Rami) (2018) Conducting action research for business and management students, London: Sage.

Cordeiro L, Soares CB (2018) Action research in the healthcare field: a scoping review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 16(4):1003–1047. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003200

de Jong Y, van der Willik EM, Milders J, Voorend CG, Rachael L, Morton FW, Dekker Y, Meuleman Y, van Diepen M (2021. A meta-review demonstrates improved reporting quality of qualitative reviews following the publication of COREQ- and ENTREQ-checklists, regardless of modest uptake. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 21(1): 184

Delaney A, Bagshaw SM, Ferland A, Manns B, Laupland KB, Doig CJ (2005) A systematic evaluation of the quality of meta-analyses in the critical care literature. Crit Care 9(5):75–82

Eden C, Huxham C (1996) Action research for management research. Br J Manag 7:75–86

Hammersley M (2007) The issue of quality in qualitative research. Int J Res Method Educ 30(3):287–305

Levin M (2003) Action research and the research community. Concepts and Transformation 8(3):275–280

Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L (2001) Use of the CONSORT Statement and quality of reports of randomized trials. A comparative before-and-after evaluation. J Am Med Association (JAMA) 285:1992–1995

Morrison B, Lifford R (2001) How can action research apply to health services? Qual Health Res 11(4):436–449

Sandelowski M, Barroso J (2002) Reading qualitative studies. Int J Qualitative Methods 1(1):74–108

Sandelowski M (2015) A matter of taste: evaluating the quality of qualitative research. Nurs Inq 22(2):86–94

Shani AB, (Rami), Coghlan D (eds) (2021) Action research in business and management: A reflective review. Action Research, 19(3): 518–541

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC and DC wrote the main manuscript text and AC and DS prepared the Tables 1 and 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This declaration is not applicable.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests associated with this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casey, M., Coghlan, D., Carroll, Á. et al. Towards a Checklist for Improving Action Research Quality in Healthcare Contexts. Syst Pract Action Res 36, 923–934 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-023-09635-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-023-09635-1