Abstract

We attempt to quantitatively study the uncertainties of the polarized brightness and for the polarization angle which are to be expected for measurements from noisy image detectors in classical coronagraphs. We derive the probability density functions (PDF) which apply to polarization observations with polarization filters at 0∘, 60∘ and 120∘. The noise in the directly observed image intensities is assumed to be normally distributed. We find that for low and medium signal-to-noise ratios the polarized brightness obeys a distribution with a strongly biased mean which, if not taken account of, leads to an overestimation of the polarized brightness and degree of polarization. The PDFs are compared with data from the SECCHI-COR1 coronagraph onboard STEREO-A in order to detect systematic or random perturbations of the polarized brightness and the polarization angle beyond the unavoidable photon and detector hardware noise. This noise is estimated from two successive filter sequences taken in-flight during calm coronal conditions on 18 May 2008 and is expressed in the form of an intensity–variance relation. Two small deviations between the measured distributions and the predicted PDF for the polarization angle were found. The standard deviation of the polarization angle error decreases with increasing signal-to-noise ratio of the polarized brightness. For ratios larger than about 8 this decrease was found not as steep anymore as predicted which could hint to a small additional noise source. Next, we found a systematic constant deviation of the polarization angle by \(-1^{\circ }\) for all signal-to-noise ratios of the polarized brightness. Besides these small discrepancies, our theoretically derived PDFs agree quite well with the distributions of measured brightnesses in test regions of the images. The PDFs we present here can equally be applied to similarly measured data from other coronagraphs and may help to quantify uncertainty limits of the derived polarization. They can be used for in-flight health checks of an instrument, are useful when separating unpolarized stray light from the polarized K-corona and when comparing the observed polarization data with results from model simulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The white light observed by coronagraphs is composed of solar light scattered at coronal electrons (K-corona), interplanetary dust (F-corona) and emissions from coronal ions like H\(\upalpha \), He D3, Fe x, Fe xiv, Ca xv, etc., in optical wavelengths (E-corona). These different light sources are difficult to separate unless the spectrum variation of the light is measured in parallel. Instead, many coronagraphs measure the linear polarization of the incoming signal. The polarized component should come only from the K- and E-corona, while the F-corona inside a field of view of about 5 solar radii can be assumed unpolarized (e.g., Koutchmy and Lamy, 1985; Levasseur-Regourd et al., 2001; Morgan and Habbal, 2007). Since the E-corona is restricted to few emission lines, the major part of the polarized broad-band white-light coronal emission is K-corona for most coronagraphs.

The polarization of the K-corona is caused by the directional anisotropy of the sunlight incident on coronal electrons (e.g., Minnaert, 1930; van de Hulst, 1950; Billings, 1966; Inhester, 2015). The degree of polarization depends on the distance from the solar surface and on the scattering angle to the observer. The resulting orientation of the observed polarization is parallel to the closest solar limb. Deviations from this orientation are expected only in rare cases, e.g., in the presence of relativistic electron beams in the corona which may occur in the vicinity of strong flares (Molodensky, 1973; Inhester, 2015) or if the Thomson-scattered light is contaminated by some E-coronal lines scattered by magnetically sensitive ions (e.g., House, Querfeld, and Rees, 1982; Heinzel et al., 2020).

Because the observed polarized brightness is much less sensitive to stray light, it has widely been used to estimate the electron density of the average corona and of the total mass of transient coronal mass ejections (CME) (e.g., Quémerais and Lamy, 2002; Feng et al., 2015). The degree of polarization observed from CMEs allows one to estimate their propagation angle off the plane-of-the-sky (e.g., Moran and Davila, 2004; Dere, Wang, and Howard, 2005; Vourlidas and Howard, 2006; Moran, Davila, and Thompson, 2010; DeForest, de Koning, and Elliot, 2017). It may also give bounds to the azimuthal widths of CMEs along the line-of-sight if observations from two vantage points are available (Bemporad and Pagano, 2015). The estimations of the CME mass, size and propagation direction have important implications for space weather forecasts. Another field where precise polarization data is required is to detect and interpret E-coronal line contributions in the white-light signal. Examples are the suppression of the polarization by resonant scattering of the H\(\alpha \) line (Mierla et al., 2011), or, as recently suggested by Heinzel et al. (2020), modifications of the degree of polarization and the polarization angle by a contamination from the helium D3-line at 587.7 nm. Both lines may be emitted from prominences and patches of cool plasma in the core of CMEs and allow inferences about the temperature and possibly of the magnetic field at the scattering site. Moreover, the decomposition into polarized and unpolarized contributions in the observed white light helps to estimate the internal, presumably unpolarized, stray light of the instrument. This stray light is an unwanted but unavoidable constituent of raw coronagraph images due the huge contrast between the coronal signal and direct sunlight of about 9 orders of magnitude.

In spite of this wide-spread use of the polarization data from coronagraphs, there are only relatively few investigations which attempt to quantify the error bounds of their results. One exception is Moran et al. (2006), who employ the observed deviation of the orientation of the polarization from the closest limb direction to test the performance of the instrument’s polarization capability and derive corrections to compensate instrumental effects. In this paper, we attempt to investigate these bounds more closely. Besides possible systematic instrumental effects, the major source of the uncertainty is the image noise due to the quantization of the detected photons (shot noise) and from the detector hardware. We intend to quantitatively determine the influence of this noise on the uncertainty of the polarized brightness and the polarization angle from observations of coronagraphs such as SECCHI-COR1 onboard STEREO-A spacecraft.

The results we obtain can be useful in several ways. For one, they may help to detect temporal variations of the instrument performance during the mission, anomalies or systematic errors which are not caused by the expected image noise. The better we can quantitatively characterize the latter, the better are the chances to discover the former. In fact, this study was motivated by exploring ways to check in-flight the quality of the polarization data from the new coronagraph PROBA3/ASPIICS to be launched in 2023 (Lamy et al., 2010; Renotte et al., 2015; Galano et al., 2018). Another application of our results we see in the determination of error bounds in the various types of model calculations which use the observed degree of polarization or polarization angle which were mentioned above. E.g., before one of these quantities is interpreted in terms of a physical model parameter, e.g., CME propagation distance from the plane-of-the-sky and its line-of-sight extent from the measured degree of polarization, or the D3 line contribution from the polarization angle, a reliable estimate of the uncertainties of the observed polarization data is highly desirable. Since Thompson scattering scales linearly with the coronal electron density, coronagraph observations are well suited for applying tomography to a series of coronagraph images from one or better more vantage points. An essential precondition for tomography is a good brightness scaling of the images (Frazin et al., 2012). Again, a quantitative error estimate is a prerequisite. If the observed polarization data and model simulations are compared by means of an inverse problem, the noise estimates could be decisive for the amount of regularization to be applied.

The estimation of measurement errors and the uncertainties of derived data products is a fundamental issue and has in a much wider context been discussed in Thomas et al. (2015). The attempt to integrate data and data errors in a common FITS-concept (Flexible Image Transport System) reveals how closely they are connected and how much a quantitative assessment of data errors is needed. This paper was inspired by this discussion and hopefully contributes to it within the realm of coronagraphy.

The plan of the paper is as follows. In Section 2, we derive the probability density functions (PDF) for the polarized brightness and the polarization angle as derived from typical coronagraph measurements such as the COR1 instruments of STEREO/SECCHI. We assume that the noise of the directly observed images is normally distributed and that this noise is the only source for the uncertainties. We here define this noise as the photon shot noise plus the hardware noise produced by the image sensor which includes dark current and read noise. It does not include non-random perturbations like stray light, ghosts or internal instrumental reflections. However, these enhance the image mean signal and thereby also add to its noise variance. While at least in principle we have a chance to subtract the mean of these artifacts, provided we can measure or model them perfectly, their contribution to the noise variance cannot be eliminated. The PDFs depend strongly on the level of this noise and they only approach the often invoked normal distribution when the signal-to-noise ratio is sufficiently small. In Section 3, the PDFs are compared to the noise distribution found in SECCHI-COR1 data observed on 18 May 2008. We first empirically estimate the noise variance for every pixel and express its dependence on the observed pixel intensity by an analytic fit which is used as a basis for the analysis that follows. In the remaining part of Section 3, we compare the statistical behavior of the observed polarized brightness and the polarization angle with the PDFs derived in Section 2. A major emphasis here is to find how well the observed mean values and standard deviations agree with the predictions from the PDFs. In a final section we discuss the results and limitations of our study.

2 PDF of the Polarized Brightness and the Polarization Angle

In the COR1 coronagraph, like in many other conventional coronagraphs, the primary observation consists of three successive intensity measurements through polarization filters with maximum transmission at \(0^{\circ }\), \(60^{\circ }\) and \(120^{\circ }\). The primary measurement is therefore a vector \({\boldsymbol{I}}=(I_{0}, I_{60},I_{120})\) for each image pixel. The orientation of a linear polarization angle is unique only modulo \(180^{\circ }\), so that the \(60^{\circ }\) polarization angle is also referred to by \(240^{\circ }\). For what follows it is, however, convenient to restrict the polarization angles to a range on which they are uniquely defined. We also omit the pixel indices here because they do not matter for our study except that we concentrate sometimes on limited image regions. A basic assumption is that each pixel is considered statistically independent.

To derive the polarization properties, the measurement vector is converted into a vector of Stokes’ components \({\boldsymbol{S}}=(S_{I},S_{Q},S_{U})\) by the demodulation matrix \({\boldsymbol{D}}\),

The first component of the Stokes vector is the total brightness \(S_{I}\). From the other two components, the polarized brightness \(S_{P}\) and the polarization angle \(\alpha \) are obtained by

respectively. For consistency of our notation, we do not use the conventional nomenclature \(B\) and \(pB\) for the total and polarized brightness here.

We do not expect any circular polarization in the light scattered from the coronal electrons. Circular polarization may, however, also be produced inside the optical path of a telescope (Sánchez Almeida and Martinez Pillet, 1992). These authors showed that an axisymmetric instrument design and small view angles off the optical axis prevent a noticeable cross-talk between polarizations. Most coronagraphs satisfy these conditions and we therefore omit the circular Stokes component here. Also, the above expression for the demodulation matrix \({\boldsymbol{D}}\) only holds in the ideal case that the three linear polarizers have unit maximum transmission and contrast and that their relative orientations are perfectly separated by 60∘. Deviations from this ideal can be fully compensated by adapting the elements of \({\boldsymbol{D}}\). However, not knowing any better we assume that Equation 1 holds for COR1.

Due to the linearity of the relation between \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\), the properties of the noise in \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) are straightforwardly inherited by the noise in \({\boldsymbol{S}}\). Especially, if the measurements in \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) are normally distributed random variables, the elements of the Stokes vector are normally distributed random variables, too. For a given pixel, we call \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}=( \overline{I}_{0}, \overline{I}_{60}, \overline{I}_{120})\) the true values we would have measured without noise. In this sense, we denote by the overbar the deterministic noiseless value also for other variables below. Since we assume that the intensities are normally distributed, \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) also represents the mean values of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) but this may not necessarily hold for other variables. The respective variances of the measured \((I_{0},I_{60},I_{120})\) are \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}=( \sigma ^{2}_{0},\sigma ^{2}_{60},\sigma ^{2}_{120})\).

The noiseless components \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}\) are then related to \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) by the same relation as Equation 1 and they are again identical to the respective means of \({\boldsymbol{S}}\). The variances of \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) are given by the sum of the variances of the terms which contribute to the respective Stokes component. Hence the normal distribution of \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) is characterized by a mean

and a covariance of

The superscript ⊤ denotes transposition and the \(\langle \rangle \) brackets statistical averaging. We made use of the obvious fact that the noise of different components in \({\boldsymbol{I}}- \overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) are independent. The elements of the covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{W}\) are explicitly

The covariance matrix is symmetric and becomes diagonal only if the variances \(\sigma _{i}^{2}\) of \(I_{i}\) are equal. If photon noise dominates, however, the respective \(\sigma ^{2}_{i}\) tend to increase with signal intensity which yields different \(\sigma ^{2}_{i}\) for different \(I_{i}\). As a consequence, we will in general also have different noise levels for \(S_{I}\), \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\).

The probability distribution for the three-dimensional Stokes vector \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) given the mean \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) and its variances \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) then is the trivariate Gaussian

However, the quantities of Equation 2 we are interested in only depend on the two components \({\boldsymbol{S}}_{P}=(S_{Q}, S_{U})\) of \({\boldsymbol{S}}\). The probability density for these two components alone is obtained straightforwardly by marginalization, i.e., integration of Equation 6 over \(S_{I}\). For multivariate normal distributions the result is obtained systematically

where \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }={\boldsymbol{V}}^{-1}\) and \({\boldsymbol{V}}\) is the two-dimensional covariance given by the \(Q\), \(U\)-submatrix of \(\boldsymbol{W}\),

The normalization in Equation 7 is

To be consistent with Equation 2, we define a random state vector in 2D Stokes space and similarly, the deterministic noiseless Stokes vector, by

so that \((S_{P},2\alpha )\) and \((\overline{S}_{P},2\overline{\alpha })\) represent the conventional cylindrical coordinates of their respective Stokes vector. The cylindrical azimuth angle \(\phi =\mathrm{atan}(S_{U}/S_{Q})\) of \({\boldsymbol{S}}_{P}\) with the Q-axis is therefore just half the polarization angle, analogously for \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\). Note that \(\alpha \) describes a unique polarization state only for values in \([0,\pi ]\). Therefore every angle \(\phi =2\alpha \), as usual in \([0,2\pi ]\), can be attributed to an independent polarization state.

From Equations 7, 8 and 9 we can obtain the desired PDFs for \(S_{P}\) and \(\alpha \) by suitable integration in Stokes space as illustrated in Figure 1. We will see below that this integration is easily performed by making use of the cylindrical coordinates introduced in Equation 10. An example for a \(P_{2D}\) of Equation 7 is sketched in Figure 1 by means of contour lines.

Contour lines of the bivariate PDF of Equation 7 in Stokes space (light blue). This distribution needs to be integrated along the dashed red circle to obtain the PDF \(P(S_{P})\) of the polarized brightness \(S_{P}\) or along the dashed dark blue radial line to obtain the PDF \(P(\alpha )\) of the polarization angle \(\alpha \). We denote by \(\overline{\alpha }\) the true polarization angle of \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) and \({\boldsymbol{u}}_{\pm }\) are the eigenvectors of \(\boldsymbol{V}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\).

Obviously, the results of the integrations for the desired PDFs depend strongly on the contours induced by \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\). In order to scale the results in a meaningful way, we introduce a representative scalar variance parameter \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) such that \(\sigma _{P}^{-2}\) is the average of \({\boldsymbol{e}}^{\top }\! \boldsymbol{\Lambda }{\boldsymbol{e}}\) for unit vectors \({\boldsymbol{e}}\) of all directions in Stokes space. By this choice, the isotropic approximation \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\rightarrow \boldsymbol{1} \sigma _{P}^{-2}\) leaves the area inside a contour of a given contour level invariant. Then \(\sigma _{P}^{-2}\) is also the mean of the eigenvalues \(\lambda _{\pm }\) of \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\), i.e.,

where \(v_{\pm }=\lambda ^{-1}_{\pm }\) are the respective eigenvalues of \({\boldsymbol{V}}\). Equivalently, \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) is the harmonic mean of \(v_{\pm }\). Due to the symmetry of \({\boldsymbol{V}}\),

so that we can express our noise measure in terms of the covariance of \({\boldsymbol{S}}_{P}- \overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) as

Most often, the true intensity \(I\) and the variance \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) of the noise added to it in a measurement are not independent. From our understanding of CCD and CMOS detectors, the detector output signal with an exposure time \(\tau \) after subtraction of the detector bias and dark current is related to the incident irradiance \(E\) by \(I= gq\;E\tau + \mathrm{noise}\). Here, \(g\) is the electron conversion gain (units: DN/e−, note in the astronomical literature often the inverse is considered as “gain”, see e.g., Astier et al., 2019) and \(q\) the quantum efficiency of the detector. The noise ideally has zero mean and a variance \(\sigma ^{2} = g^{2}q\;E\tau + c=g \overline{I}+c\). We may apply this relation to the intensity of each polarization filter to

Assuming that this relation holds, \(P_{2D}\) Equation 7 depends only on the true intensity vector \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) we would measure if its detection was noiseless. Applying this PTC relation systematically in Equations 3 and 4, the inverse two-dimensional covariance becomes

Inserting \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}=( \overline{S}_{Q},\overline{S}_{U})= \overline{S}_{P}(\cos 2 \overline{\alpha },\sin 2 \overline{\alpha })\) with polarization angle \(\overline{\alpha }\) we easily see that the eigenvectors of \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\) become

In other words, as the center \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) of the contour ellipses in Figure 1 rotates with \(2\overline{\alpha }\), the ellipse orientation rotates oppositely with \(-\overline{\alpha }\) and the angle between \({\boldsymbol{u}}_{+}\) and \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) is \(\beta =3\overline{\alpha }\) (see Figure 1). However, this behavior strictly holds only if Equation 12 is valid.

2.1 Polarized Brightness

As described above, the probability density for \(S_{P}\) for a given polarized brightness \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}=( \overline{S}_{Q},\overline{S}_{U})\) and covariance \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\) is obtained by the integration of the bivariate PDF of Equation 7 along a circle in Stokes space with radius \(S_{P}\). In the cylindrical coordinates Equation 10, the probability of the infinitesimal Stokes space element with \(2\alpha \) replaced by \(\phi \) is \(P_{\mathrm{2D}}(S_{Q},S_{U})\,dS_{Q}dS_{U} = P_{\mathrm{2D}}(S_{P}( \cos \phi ,\sin \phi ))\,S_{P}dS_{P}d\phi \). Integration over \(\phi \) and omitting the integration measure \(dS_{P}\) for \(P(S_{P})\) yield

where the integration is over the full circle \(\phi =0\) to \(2\pi \). This way we maintain the normalization of the probability, i.e., \(\int P(S_{P})\,dS_{P}=1\). Unfortunately, this integration in its general form has to be evaluated numerically. We choose a Gauss-Legendre integration rule which gives an error better than \(10^{-6}\) for 12 integration points if the integration range is restricted to the range of \(\phi \) where the integrand is significant.

A simple analytic form can be obtained when we approximate the covariance \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\) by the isotropic matrix \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\boldsymbol{1}\). This simplification holds if in the PCT relation Equation 12, either the non-photonic noise in parameter \(c\) dominates or if the polarization is low and all \(I_{i}\) are about equal. In Appendix A we derive for this case

Here, \(\mathrm{I}_{0}\) is the modified Bessel function of first kind (Abramowitz and Stegun, 1964). The ratios \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) and \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) can be considered as a signal-to-noise ratio of the respective polarized brightness.

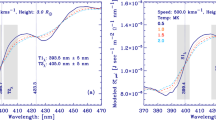

In Figure 2, we show examples of the PDF Equation 13 and its approximation Equation 14. For the calculation of the former we assumed Equation 12 to hold with \(c=0\) and \(g\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) tuned so that the desired ratio \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) and degree of polarization \(p\) were obtained. The colored ranges in Figure 2 cover the values of the PDF for a degree of polarization \(p=0\) to 0.4 and all polarization angles \({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\) so that the angle \(\beta \) of the contour ellipse axis in Figure 1 rotates by \(2\pi \). The boundaries of the colored ranges are reached for angles \(\beta =0\), \(\pi /2\) and \(\pi \). The solid curves show a specific example with orientation angle \(\beta =\pi /4\) for which the PDF is very close to the isotropic approximation Equation 14, represented by the respective dashed curves inside the colored ranges.

The PDF of Equation 13 of the normalized polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) for some values of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) as given in the legend according to color. The colored ranges represent the numerically derived PDF values for all polarization angles \(\overline{\alpha }\) and degrees of polarization between \(p=0\) and 0.4. The solid curves give a specific example for \(p=0.4\) and a polarization angle so that the angle between the \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\)-eigenvector \({\boldsymbol{u}}_{+}\) and \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) is \(\beta =\pi /4\) (see Figure 1). The dashed curves represent the respective isotropic approximation Equation 14 which is independent of \(\overline{\alpha }\). For the PDF with the largest \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}=6\), we have also indicated as green dashed curve the asymptotic normal Equation 16. For this value of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\), it is hardly distinguishable from Equation 14.

Since the PDF of Equation 14 with isotropic covariance is a decent approximation, we can use it to discuss the two limiting cases \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P} \rightarrow 0\) and \(\rightarrow \infty \). In the limit of vanishing polarized brightness, the PDF becomes

which complies with the \(\chi ^{2}_{2}\)-distribution for two degrees of freedom for the two random variables \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\) if each has zero mean.

For large values of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\), we find a normal distribution

For details of the derivation, see again Appendix A.

The PDFs of Equations 13 and 14 have a heavily biased mean value and also the argument of the PDF maximum differs considerably from the true polarized brightness. This has consequences for possible observations. For a single measurement, e.g., from a single image pixel, the most probable value of \(S_{P}\) we will measure is the value \({S_{P}}_{\mathrm{max}}= \mathrm{argmax}\,P(S_{P})\) where the PDF has its maximum. Even if the true \(\overline{S}_{P}\) is zero, we most probably will measure a finite value for \(S_{P}\) around \(\sigma _{P}\). If we have many independent, statistically equivalent measurements of \(S_{P}\), we may use them to reconstruct the PDF itself or average them to obtain approximately the expectation mean value \(\langle S_{P}\rangle = \int _{0}^{\infty }S_{P}\,P(S_{P})d\, S_{P}\). If, e.g., again \(\overline{S}_{P}=0\), a mean of even \(\langle S_{P}\rangle = \sqrt{\pi /2}\,\sigma _{P}\) will result.

For large \(\overline{S}_{P}/ \sigma _{P}\), the bias of the PDF maximum argument and of the PDF mean value shrink less rapidly than one might expect from the relatively fast evolution of the PDF shape towards a normal distribution. In Figure 3, we show in the left diagram the most probably measured polarized brightness \({S_{P}}_{\mathrm{max}}\) (black and gray) and expection mean value \(\langle S_{P}\rangle \) (red and rose) from Equation 13 (colored ranges) and the isotropic approximation Equation 14 (dashed curve). Both values approach the true \(\overline{S}_{P}\) (represented by the exact diagonal) only very slowly. Even for medium signal-to-noise ratios of the polarized brightness, we tend to overestimate the true polarized brightness unless we correct for the bias.

Left: The polarized brightness argument \({S_{P}}_{\mathrm{max}}/\sigma _{P}\) of the PDF maximum (black and gray) and mean value \(\langle S_{P}\rangle / \sigma _{P}\) of the PDF of Equation 13 (red and rose), both as function of true polarized brightness \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). The colored ranges were obtained from Equation 13 with the same parameter ranges for \(p\) and \(\beta \) as in Figure 2. The black and red dashed curves again represent the respective quantities for the isotropic approximation Equation 14. The green dashed curve gives the maximum likelihood polarized brightness \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) on the abcissa for a measured value \({S_{P}}_{\mathrm{max}}/\sigma _{P}\) on the ordinate. The solid diagonal is drawn to show the small but finite offset of the above curves for larger arguments. Right: Standard deviation (black and gray) and rms distance to the true \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) (red and rose) for the PDF of Equation 13 as function of the true polarized brightness \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). The colored ranges were obtained again from Equation 13 with the same parameter ranges for \(p\) and \(\beta \) as in Figure 2 and in the left panel. The dashed curves again represent the respective quantities for the isotropic approximation Equation 14.

We propose a correction of the bias for the above two estimators of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\):

-

i)

We have a single measurement of the polarized brightness, \(S_{P1}/\sigma _{P}\) and we assume that this measurement is the most likely one we could have made, i.e., it maximizes the PDF. This implies that \(S_{P1}/\sigma _{P}>1\).

-

ii)

We have a number of equivalent measurements and determined their mean to \(S_{P\infty }\). Here we assume that this sample mean estimate agrees with the exact mean \(\int S_{P} \,P(S_{P},/\sigma _{P})dS_{P}\). This implies that \(S_{P\infty }/\sigma _{P}>\sqrt{\pi /2}\).

Replacing either \(S_{P1}/\sigma _{P}\) or \(S_{P\infty }/\sigma _{P}\) by \(x\), an improved value for \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) can be found from

Another way to deal with the bias is the maximum likelihood estimate of \(\overline{S}_{P}\). This estimate seeks the most likely value of \(\overline{S}_{P}\) for a given measurement \(S_{P}\), i.e., \(\text{argmax}_{\overline{S}_{P}( \overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}})} P(S_{P}\,|\, \overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}, \boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}})\). Applied to the PDF of Equation 14 with isotropic covariance, this estimate is shown by the green dashed curve in Figure 3. For consistency of the plot axes, the measured \(S_{P}\) is taken from the ordinate, the resulting maximum likelihood \(\overline{S}_{P}\) is assigned to the abcissa.

The left diagram of Figure 3 shows some second moments of Equations 13 and 14. The standard deviation, \(\langle (S_{P}-\langle S_{P}\rangle )^{2}\rangle ^{1/2}/ \sigma _{P}\) is drawn in black and gray, the rms distance \(\langle (S_{P}-\overline{S}_{P})^{2}\rangle ^{1/2}/ \sigma _{P}\) from the true \(\overline{S}_{P}\) in red and rose. For large \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\), the standard deviation is about \(\sigma _{P}\) which proves that Equation 11 is a useful measure of the variance. For \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) less than about 2, The standard deviation shrinks because \(S_{P}\) is restricted to positive values. This is also the reason why the measured polarized brightnesses deviates from the true value by a considerable fraction of the measurement standard deviation.

2.2 Polarization Angle

To obtain the probability density for the polarization angle \(\alpha \) for given polarized brightness \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}=( \overline{S}_{Q},\overline{S}_{U})\) and covariance \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\) we need to integrate the bivariate PDF of Equation 7 along a radial line from the origin of Stokes space in direction \({\boldsymbol{e}}=(\cos 2\alpha , \sin 2\alpha )\). We again use the cylindrical coordinates Equation 10 to transform the infinitesimal Stokes space element \(P_{\mathrm{2D}}(S_{Q},S_{U})\,dS_{Q}dS_{U} = P_{\mathrm{2D}}(S_{P}( \cos 2\alpha ,\sin 2\alpha ))\,S_{P}dS_{P}\,2d\alpha \). Integration over \(S_{P}\) and omitting the integration measure \(d\alpha \) for \(P(\alpha )\) yields

Again, the normalization \(\int P(\alpha )\,d\alpha =1\) is maintained for the nominal range \([0,\pi ]\) of the polarization angle \(\alpha \).

The integral can be evaluated by elementary means. To shorten the notation, we abbreviate the direction of integration in Equation 18 by \((\cos 2\alpha , \sin 2\alpha )={\boldsymbol{e}}(\alpha )\) and similarly \((\cos 2\overline{\alpha }, \sin 2 \overline{\alpha })= \overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}}\) for the direction of the true Stokes vector so that \({\boldsymbol{S}}_{P}=S_{P}{\boldsymbol{e}}\) and \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}= \overline{S}_{P} \overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}}\). With these definitions, the result can be written as (see Appendix B)

We note that by construction, Equation 19 is periodic on \([\overline{\alpha }-\pi /2, \overline{\alpha }+\pi /2]\). If we extend the range of \(\alpha \) to \(2\pi \), Equation 19 for \(\overline{S}_{P}=0\) becomes the Bingham distribution on a circle (Bingham, 1974).

Examples of Equation 19 are shown in Figure 4 in the same manner as for Figure 2. Note that the PDF is not necessarily symmetric as the special case demonstrates (see solid curves in Figure 4) where the parameters are such that the angle between the \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\)-eigenvector \({\boldsymbol{u}}_{+}\) and \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) is \(\beta =\pi /4\). The PDF is symmetric to \(\overline{\alpha }\) only for orientation angles \(\beta =0\), \(\pi /2\) and \(\pi \). The PDF then coincides with one of the boundaries of the colored ranges in Figure 4.

The PDF of Equation 19 for the deviation of the polarization angle \(\alpha \) from its true value \(\overline{\alpha }\) for five values of the parameter \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) as given in the legend according to color. The parameters for the colored ranges are the same as in Figure 2. The solid curves show a specific example for \(p=0.4\) and a polarization angle so that the angle between the \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\)-eigenvector \({\boldsymbol{u}}_{+}\) and \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}\) is \(\beta =\pi /4\) (see Figure 1). The dashed curves again represent the isotropic approximation Equation 14.

Again, the PDF considerably simplifies for some limiting cases. From Figure 4 clearly Equation 19 approaches a normal distribution when \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) is large. In this case erf\(\rightarrow \mathrm{sign}( \overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}} ^{\top }\!\boldsymbol{\Lambda } {\boldsymbol{e}})\) and we can set \(K=\sqrt{2\pi /{\boldsymbol{e}}^{\top }\! \boldsymbol{\Lambda }{\boldsymbol{e}}}\;S_{0}\) where \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}} ^{\top }\!\boldsymbol{\Lambda } {\boldsymbol{e}}>0\). So for large \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) and \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}} ^{\top }\!\boldsymbol{\Lambda } {\boldsymbol{e}}>0\),

For negative \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}} ^{\top }\!\boldsymbol{\Lambda } {\boldsymbol{e}}\), we can in this limit safely set \(P(\alpha \;|\; {\boldsymbol{I}}, \boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}) \rightarrow 0\). It can be shown that the exponent in Equation 20 minimizes at \({\boldsymbol{e}}= \overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}}\), i.e. at \(\alpha =\overline{\alpha }\), but depending on the orientation of \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }\), also Equation 20 may not be completely symmetric about \(\overline{\alpha }\).

Perfect symmetry is obtained only when we approximate the covariance \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\) by the isotropic matrix \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\boldsymbol{1}\). In this case, \({\boldsymbol{e}}^{\top }\! \boldsymbol{\Lambda }{\boldsymbol{e}} \rightarrow \sigma ^{-2}_{P}\), \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{e}}} ^{\top }\!\boldsymbol{\Lambda } {\boldsymbol{e}}\rightarrow \sigma ^{-2}_{P}\cos 2(\alpha - \overline{\alpha })\) and the PDF of Equation 19 becomes

which for large \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) and \(|\alpha -\overline{\alpha }|<\pi /4\) further simplifies to

The isotropic approximation Equation 21 is again shown as dashed curves inside the colored ranges in Figure 4.

Of particular interest here is the variance of the PDF of Equation 19 because it gives us the statistical error we have to expect for the determination of the polarization angle. From the large \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\)-limit in Equation 20 and its isotropic approximation, the variance approaches

The variance has units of rad2 and the factor \(1/4\) reflects the ratio \(1/2\) between the azimuth angle in Stokes space and the polarization angle.

For small and medium values of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\), the expectation values of mean and variance have to be calculated from suitable moment integrals over the PDF of Equation 19 which take account of the periodicity of the random variable (e.g. Mardia and Jupp, 2000). We here adopt the concept of the circular variance for the first and second moment. These moments are replaced the variance function

The expectation mean value \(\langle \alpha \rangle \) for the polarization angle then minimizes \(V(\psi )\) and the corresponding minimum value \(V(\langle \alpha \rangle )\) is the circular variance of the PDF, i.e.,

In Appendix C, we propose a simple procedure by which Equation 25 can be solved.

In Figure 5 we show these moments in black for the same range of parameters used before. We compare \(\langle \alpha \rangle \) with the most probably measured polarization angle \({\alpha }_{\mathrm{max}}=\mathrm{argmax} \,P(\alpha )\) in the left diagram and in the right diagram the standard deviation \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) with the upper and lower quartile distances from \(\alpha =\overline{\alpha }\) drawn in red. The deviation of \(\langle \alpha \rangle \) and in particular of \({\alpha }_{\mathrm{max}}\) from \(\overline{\alpha }\) is a result of the fact that the PDF for most angles \(\beta \) is not symmetric (see specific example in Figure 4). It is largest for angles \(\beta \) near \(\pi /4\) and \(3\pi /4\) (see Figure 1). However, both are much smaller than the standard deviation and are probably only relevant for high precision determinations of the polarization angle. From the right diagram we see that \(\sigma ^{2}_{\alpha ,\infty }\) in Equation 23 approximates the variance quite well for values of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) as low as \(\approx 1\).

Left: Range of the circular expectation mean \(\langle \alpha -\overline{\alpha }\rangle \) (gray, see Equation 25) and of the most probably measured polarization angle \({\alpha }_{\mathrm{max}}- \overline{\alpha }\) (rose) for the PDF of Equation 19 as function of \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). The colored ranges represent values obtained for polarization angles \(\overline{\alpha }\) and degrees of polarization \(p=0\) to 0.4 as for Figure 2. The mean and argmax polarization angles for the isotropic distribution 14 exactly agree with \(\overline{\alpha }\) (black dashed line). Right: Circular standard deviation \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) (black and gray, see Equation 25)) and quartile distance from \(\overline{\alpha }\) (red and rose) for the PDF of Equation 13 as function \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). For the colored ranges, the parameters in Equation 13 were varied as in the left diagram and as in Figure 2. The dashed black and red curves represent the respective quantities for the isotropic approximation 14. The small dashed black curve is the approximation \(\sigma _{\alpha ,\infty }\) for large \(\overline{S}_{P}\) from Equation 23.

3 Observations

The data we use to test the PDFs derived above were obtained from the COR1 instrument on board STEREO-A, one of the two Solar TErrestial RElations Observatory spacecraft (STEREO, see Kaiser et al., 2008). COR1 is the innermost coronagraph of the Sun Earth Connection Coronal and Heliospheric Investigation (SECCHI) instrument suite (Howard et al., 2008). It observes the corona through three linear polarizers at 0∘, 60∘, and 120∘ in a 22.5 nm wide white-light waveband centered at the H\(\upalpha \) line at 656 nm (Thompson and Reginald, 2008). The telescope has a field of view from 1.4 to 4 \(R_{\odot }\) but here, we will use the data only between 1.5 to 3 \(R_{\odot }\). The image data was reduced onboard the spacecraft to 1024×1024 pixels resulting in a pixel resolution equivalent to \(7.5"\).

The exposure time was 1.7 s for each polarized image, one full polarization sequence was taken within 18 s. The polarized image sequences were repeated after 10 min. In this work we investigate data from a polarization scan taken at 18 May 2008 at \(t_{1}=\) 1405 UT and \(t_{2}=\) 1415 UT. Within these 10 minutes, the Sun did not show any activity so that the measured intensities in equally polarized images varied very little.

For each individual image, the raw data was first cleaned using the SolarSoft secchi_prep routine. By default, secchi_prep applies the following steps: subtraction of the CCD bias, applying flat-field, vignetting and exposure time correction and an adjustment of the image orientation so that the y-axis points to solar north. Here, a roll angle of 7.5∘ had to be applied. The standard processing steps comprise two more actions we did not readily apply. We did not multiply the image intensities with the calibration factor which converts the digital image values to fractions of mean solar brightness (MSB) but we rather prefer to continue in units DN s−1 for the components of the measured and preprocessed intensity vector. Another processing step is the subtraction of a monthly minimum background to clean the images from stray light, some internal reflections and other instrument artifacts (Thompson et al., 2010). Here, we keep both, the image before background subtraction with intensities \({\boldsymbol{J}}=(J_{0},J_{60},J_{120})\) and after subtraction with intensities \({\boldsymbol{I}}=(I_{0},I_{60},I_{120})\). The background \({\boldsymbol{J}}-{\boldsymbol{I}}\) is the same for the images at 1405 and 1415 UT but it differs for different polarizations.

In our subsequent analysis we only consider the restricted field of view from 1.50 to 2.94 R⊙ around the occulter center because for the quiescent time of the observations, the intensities at larger distances were very low. As a result, we have four polarization image sets \({\boldsymbol{J}}(t)\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}(t)\) with and without background, respectively, at two observation times \(t_{1}=\) 1405 UT and \(t_{2}=\) 1415 UT. In Figure 6, we show for the limited field-of-view considered here all three components of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) and, as an example, one polarization of \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) for one observation time. Note the strongly enhanced intensity level in \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) as compared to \({\boldsymbol{I}}\).

Images of the intensities \(I_{0}\), \(I_{60}\) and \(I_{120}\) without background (top row and bottom left) and one of the measured intensities \(J_{120}\) which still includes the background (bottom right). All images were observed at 1415 UT. Note the different color code for the intensities \(I\) and \(J\). The inner ring represents the position of the solar disk, the regions 1 to 5 in image \(I_{120}\) are marked here for later reference.

3.1 Intensity-Variance Relation

So far we have treated the parameters of the PDFs, \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\), as if they were independent. For most detectors, they are related, e.g., by the ideal relation Equation 12 with constants \(g\) and \(c\) from a pre-flight calibration.

Here we chose another approach. We have to keep in mind that the available COR1 data \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) have already been processed to some extent. For this reason we will work with an empirical intensity-noise relation between \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and its variance. Since the detector cannot distinguish between light from the corona or from stray light, a unique relation between intensity and noise can only be expected to exist for the intensity \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) which still includes the background made up of stray light, internal instrument reflections and ghosts. The background correction between \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) is determined from data of a whole month around the observation and can be assumed to contain much less statistical noise than the individual image. So \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) can well be assumed to have the same variance. Moreover, since the CCD detector should not be sensitive to different polarizations, we expect that the noise variance does not depend on the polarization of incident intensity.

To find the intensity–variance relation for \({\boldsymbol{J}}\), we make use of the fact that the coronal conditions changed very little during the 10 min between the two polarization sequence observed so that the difference images are dominated by the same level of image noise. With this prerequisite in mind, we then use for each pixel the difference between images at \(t_{1}\) and \(t_{2}\) of equal polarizer orientation as a noise sample and the respective average as the corresponding intensity estimate. For each pixel and each polarization \(i=0\), 60, 120 we form

The factor \(1/\sqrt{2}\) in \(\Delta J_{i}\) accounts for the fact that the intensity difference has twice the noise variance of a single image. An example for one such difference image is shown in Figure 7.

For each pixel, the pair of numbers in Equation 26 only represents a random sample of the desired intensity–variance relation. The relation can be estimated by suitable averaging where a trade-off has to be sought between a sufficiently large number of pixels and statistical homogeneity for each average. The compromise between these two requirements was found experimentally. We segment the images in small tiles with a size of 3 pixels in radial direction and \(2.5^{\circ }\) in azimuth. These 9600 tiles have between 25 and 50 pixels each. Within each tile, we form tile-averages

In Figure 8, we plot in color-code the relative number of occurrence of pairs \((\overline{J}_{i}, \overline{\Delta J^{2}_{i}})\) summed over all polarizations \(i=0,60\) and 120 in discretized 2D classes of \(\overline{J}\) and \(\overline{\Delta J^{2}}\). The size of each color tile in Figure 8 represents the respective class range.

Color-coded distribution of the relative occurrence of the variance estimate \(\overline{\Delta J^{2}_{i}}\) (ordinate) in a tile with mean intensity \(\overline{J_{i}}\) for all polarizations \(p\) superposed. The black step-like curve indicates mean variances for pixels in the respective equidistant subranges of log \(\overline{J}\). The standard deviations of the mean estimates are indicated by the vertical bars. The continuous black curve represents the polynomial fit Equation 27 to the maximum of the distribution.

A polynomial fit to this distribution yields the desired approximation of the intensity–variance relation over all polarizations \(p\)

This fit is overplotted as smooth curve on top of the distribution in Figure 8.

Equation 27 does not have the expected PTC-like form Equation 12. Instead, we had to add a term proportional to \(\overline{J}{\,}^{3}\) in order to account for the steep increase of the observed variance in Figure 8 for log\(\overline{J}>\) about 3.5. A quadratic term would not have been sufficient here.

Higher order terms in a PTC-relation are known and some are well understood (see, e.g., Astier et al., 2019). The most common reason is fixed-pattern-noise which introduces an additional \(\overline{J}{\,}^{2}\)-dependence when the PTC curve is determined from the variance with respect to an intensity average over the entire field-of-view (fixed-pattern-noise, see, e.g., Janesick, 2007). In Equation 27, only intensity differences from the same pixel enter the variance and in addition, the image was flat-fielded before which should have drastically reduced the effect of the fixed-pattern-noise in Equation 27. Some of the tiles we average over, especially in the bright areas near the occulter edge, may be intersected by the bright internal reflections visible in \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) (see lower right of Figure 6). This may cause some enhancement of the variance, but we checked that this effect is small by reproducing Equation 27 with different tile-sizes. We rather assume that the steep increase in Equation 27 is due to the vignetting component in the flat-field correction (Thompson et al., 2011) which causes an enhancement of the detector counts proportional to the vignetting correction factor \(\ge 1\). The local variance is consequently enhanced by this factor squared. This correction especially affects the region near the occulter edge where intensities and vignetting corrections are large. A solid explanation of Equation 27 is beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, we just use it as an empirically-determined, effective PTC-like relation.

As a check of Equation 27, we have binned the \(\langle J_{i}\rangle \) values from Equation 26 of all polarizations into logarithmically equidistant classes and determined the mean values of \((\Delta J_{i})^{2}\) and their standard deviations for each class. These tile-independent variance estimates are overplotted in Figure 8 as a step-wise curve with vertical bars indicating the uncertainty of the respective class mean estimate. The horizontal width of the steps indicate the class width of log \(\langle J_{i}\rangle \). The mean variances obtained follow Equation 27 quite well. A small but significant deviation occurs between log \(\langle J_{i}\rangle =\) 3.6 to 3.9 where the distribution of \((\Delta J_{i})^{2}\) within a class is skewed so that mean and maximum deviate by up to a factor 1.4. This makes at most a factor 1.2 in the standard deviation estimate of the image noise.

In the following we will use the background subtracted pixel intensities \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) to calculate samples of the polarized brightness and the polarization angle using Equations 1 and 2 as in the conventional polarization analysis. The expected variance of the pixel intensities in Equation 4 is approximated by Equation 27 substituting for each pixel and polarization the intensity \(\langle J_{i}\rangle \) for the argument \(\overline{J}\). Since the background correction between \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) is determined from data of a whole month, it can be assumed to contain much less statistical noise than the individual image. For this reason, it is safe to use \(\sigma _{J}^{2}(\langle J_{i}\rangle )\) also as noise variance for \(I_{i}\) for the same pixel and the same polarization \(i\). The variance vector in Equation 4 for a given pixel is accordingly given by

where \(\langle J_{i} \rangle , \; i=0, 60, 120\) are the three components of Equation 26 at the respective pixel.

3.2 Polarized Brightness

We test the polarized brightness PDF in Equations 13 and 14 with the above observations in three small regions 1 to 3 which we select so that they represent different levels of the normalized polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). In region 1, the observed signal is almost pure noise, with region 2 we have tried to cover a faint plume, better visible in the image of the polarization angle in the next chapter. Region 3 is representative of a large signal strength and is located near the axis of a streamer. The regions are displayed in the upper right panel of Figure 6 and also in Figure 9 which gives an overview of the observed normalized polarized brightness for the entire field-of-view.

The values of \(S_{P}\) were obtained for every pixel individually from Equations 1 and 2. Similarly, the variance parameter \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) was calculated for every pixel from Equation 11 where \(\sigma ^{2}_{\mathit{QQ}}\), \(\sigma ^{2}_{\mathit{UU}}\) and \(\sigma ^{2}_{\mathit{QU}}\) were derived from Equations 28 and 5. The fringe-like structures in Figure 6 near the occulter edge are due to the instrumental reflections and stray light patterns in the observed images \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and hence in \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\).

The requirement for a statistically homogeneous sample from the regions had to be compromised with the size of the regions and a sufficient number \(N\) of pixels to reduce the statistical uncertainty. The pixel numbers are \(N=\) 1909 (region 1), 589 (region 2) and 445 (region 3). We reduce the small inhomogeneity of the data in each region by fitting a 2nd-degree 2D polynomial to each component of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) and subtracting the variable part of the respective fit relative to the region center. This has practically no effect except for region 3 which sits on the axis of a streamer. It includes a non-negligible radial intensity gradient which is compensated by this detrending procedure.

To compare the observed distribution of the normalized polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) with the polarized brightness PDF from Equation 13, we use as PDF parameters \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) its regional mean and for \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) the variances from Equation 28 with the regional means of \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) as argument. Since \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) are normally distributed, their mean values are unbiased and their variances are only \(1/N\) times the variance of a single pixel intensity as in Equation 27.

Figure 10 for region 1 represents the case where the K-corona is negligible and the observed intensity is unpolarized. \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\) have practically zero mean while the total brightness \(S_{I}\) has a finite mean which is probably the result of residual stray light. The fact that the mean values of \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\) almost vanish gives us some confidence that the different backgrounds subtracted to obtain \(I_{0}\), \(I_{60}\), \(I_{120}\) is consistent at least in region 1. The distributions for \(S_{Q}\), \(S_{U}\) and \(S_{I}\) comply almost perfectly with normal distributions with the parameters derived form the regional means of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) as explained above. These parameters are always given in the legend of the respective figure.

Left: Distribution of the Stokes components \(S_{I}\) (black), \(S_{Q}\) (green) and \(S_{U}\) (red) measured in region 1. Right: Distribution of the normalized polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) in region 1. The dashed curves are the theoretically expected distributions with the parameters as given in the respective legend. These were determined from the regional averages of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) inserted in Equation 3 for \(\overline{S}_{P}\) and the respective averages of \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) using Equations 27, 4 and 11 for \(\sigma _{P}\). The PDFs were calculated both from Equation 13 and Equation 14, but the difference is not visible here.

The same holds for the observed distribution of \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) in the right diagram which obeys closely the almost identical PDFs in Equations 13 and 14. Note that the best estimate of \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) in region 1 is 0.02. However, the most probably observed pixel value is near \(\approx 1\). This explains the dominant blue to light blue color in the polar sectors in Figure 9. It corresponds to a value of \(\log _{10} S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) near 0 even though the probably true polarized brightness there is much smaller and practically below detectability.

With region 2 we have tried to cover a faint plume above the southern polar region. Therefore the region was placed close to the occulter edge, it is only 5∘ or 20 pixels wide and has 30 pixels in radial direction. Since the region 2 is almost exactly south of the Sun center, we expect for the polarized components in \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\) a polarization angle close to \(90^{\circ }\) with respect to the vertical. A signal polarized at this angle has a 3D Stokes vector along \((1,-1,0)\). The negative shift of \(S_{Q}\) relative to \(S_{U}\) is a clear indication of a finite polarized brightness. The relatively larger observed \(S_{I}\) accounts for a low degree of polarization. The best estimate of the polarized brightness is \(\overline{S}_{P}= 0.82\,\sigma _{P}= 10.3\) DN/s even though the most probably observed pixel value is about twice as much (right diagram of Figure 11). The observed distribution has much more scatter than region 1 which we attribute to the reduced number of pixels to about one third and also to the influence of the stray light and reflection features in \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) so close to the occulter edge.

Region 3 is an example for a strong K-corona signal. The observed and expected distributions are shown in Figure 12. Since the region has an azimuth from \(111^{\circ }\) to \(116^{\circ }\), the polarization angle should be centered at \(23.5^{\circ }\) and the polarized component of the signal should have a 3D Stokes vector in direction \((1,0.68,0.73)\). The light observed from this region also has a decent unpolarized component so that \(S_{I}\) is larger than \((S_{Q}^{2}+S_{U}^{2})^{1/2}=\) 153 DN/s. Remarkable is the fact that different from this expected Stokes vector direction we observe \(S_{Q}>S_{U}\) which causes a deviation of the observed polarization angle from \(23.5^{\circ }\) by about \(-1^{\circ }\) (this issue is discussed further in the next section). The distribution of the observed polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) again agrees with the theoretical expectation, except that our variance parameter \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) slightly overestimates the uncertainty here. This leads to a little wider theoretical distribution than observed. The best estimate of the polarized brightness in this region is \(\overline{S}_{P}=11.2\,\sigma _{P}=\) 153 DN/s. For this large value, the PDF in Equation 13 comes close to a normal distribution and averaging \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) over all pixels reproduces in this case the best estimate \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) for this region quite well.

For all three comparisons of the measured \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) distributions with the PDF we have performed \(\chi ^{2}\) goodness-of-fit tests (e.g., Fisher, 1934; Barlow, 1989). We used the isotropic approximation Equation 14 of the PDF here (short dashed curves in Figure 12) because it has only a single free parameter, \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) and the differences to Equation 13 are only small. The \(\chi ^{2}\) test is widely applied in different science fields but the procedures and definition of indices slightly differ. In appendix D we therefore have briefly summarized how we performed the test and define the comparison indices, effect size and p-value, we use here. These indices are easily calculated but are much less easily interpreted (see e.g., Halsey et al., 2015). A common rule is that effect sizes above about 0.1 are a hint that the measured distribution has been “affected” so that it differs sufficiently from the theoretical PDF. Larger effect sizes corresponds to larger discrepancies. The p-value is a measure for the probability that the observed sample was drawn from numbers distributed like the comparison PDF. This hypothesis is usually considered acceptable if the p-value is above about 0.05 to 0.1.

The outcomes of our tests are listed in Table 1. Except for region 1, the PDFs do not appear to comply with the observed distributions according to the common interpretation of the test. A difference between our test to their common use is that we did not fit the PDF parameter \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) but, as explained above, \(\overline{S}_{P}\) and \(\sigma _{P}\) were determined form the regional means of \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{I}}\). In addition, the inhomogeneities in \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) especially in region 2 probably devalidate the homoscedasticity requirement (equal variance of measured data) for the \(\chi ^{2}\) test. Given these problems with the measured data, we still consider the observed distribution in acceptable agreement with the theoretical PDFs, except that its variance parameter \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) seems to be somewhat underestimated in region 2 and overestimated in region 3.

3.3 Polarization Angle

To compare the PDF in Equation 19 of the polarization angle with the observed data, we use regions 4 and 5 (see Figure 6), which more or less cover the two streamer regions above the east and west limb. For every pixel in these regions we calculate the discrepancy \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) from Equations 1 and 2 and also the pixel value of normalized polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). We then bin the angle errors in classes of different polarized brightness levels and determine their distribution inside each class. The choice of the regions 4 and 5 insures that we have a wide range of polarized brightness levels.

Since the regions cover a considerable azimuthal range, we use the closest local limb orientation as estimate of \(\overline{\alpha }\) for each pixel,

Here, \(\phi _{\odot }\) is the pixel’s azimuth angle with respect to the Sun center which is displaced from the occulter center. The azimuth is defined clockwise with \(\phi _{\odot }=0\) towards north and a branch cut in the south. With this definition, \(\phi _{\odot }\) here varies in the range \([-\pi ,\pi ]\) and the polarization angle here is confined to the range \([-\pi /2,\pi /2]\).

The polarization angles \(\alpha \) and \(\overline{\alpha }\) are shown in the left panel of Figure 13, the theoretically expected standard deviation \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) for \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) calculated for each pixel using Equation 25 in the right panel. The smallest standard deviation \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) of \(\approx 1.3^{\circ }\) is predicted just above the occulter in the bright streamer regions where \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) rises up to 22. Since the artificial reflections in the background part of \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) enter into \(\sigma _{\mathit{QQ}}^{2}\), \(\sigma _{\mathit{UU}}^{2}\) and \(\sigma _{\mathit{QU}}^{2}\) their imprint can also be found in \(\sigma _{P}\) in Equation 11 and therefore also in the standard deviation \(\sigma _{\alpha }\). They are particularly visible near the occulter edge.

Left: Polarization angle \(\alpha \) for each pixel. The angles for pixels with \(S_{P}<0.71\sigma _{P}\) were omitted. The color code inside the occulter indicates the angle \(\overline{\alpha }\) of the closest limb orientation for reference. Right: Standard deviation \(\sigma _{P}\) derived from Equation 25 and the measured intensity \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) for each pixel.

To estimate the empirical distribution of the error in the polarization angle, we can compare \(\alpha \) pixel-by-pixel with its theoretical value \(\overline{\alpha }\) of Equation 29. This method has successfully been applied by Moran et al. (2006) to data from the SOHO/LASCO-C2 coronagraph to correct systematic errors of the coronagraph polarization data. In the upper panel of Figure 14 we plot the polarization angle for every pixel with \(S_{P}<0.71\,\sigma _{P}\) versus the azimuth angle \(\phi _{\odot }\) of the pixel position relative to the Sun center. The ideal result should be a two-teeth sawtooth curve represented by the two oblique solid lines. It is obvious from the color code, that pixels with large values of \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) (red dots) come closer to their nominal values than the pixels with low \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) values (blue). In the panel below, we show the same data with the same color code but with the polarization angle replaced by the distance from the Sun center to help identify from which image location the polarization angles were obtained.

Top: Scatterplot of the pixel-wise polarization angle vs pixel azimuth with respect to the Sun center. The color code represents the magnitude of parameter \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). Pixels with \(S_{P}<0.71\sigma _{P}\) were omitted. The solid vertical lines separate the four azimuth quadrants, the oblique lines indicate the theoretically expected \(\overline{\alpha }\). The dashed vertical lines represent the azimuths of the region boundaries 4 and 5 at 1.5 \(R_{\odot }\). Bottom: The above data with the same color code in spatial cylindrical coordinates centered at the sun center. Due to the transformation from Cartesian image to cylindrical coordinates, most of the spatially isolated pixels with \(S_{P}<0.71\,\sigma _{P}\) were lost due to interpolation. The transformed region boundaries defined with respect to the occulter center are drawn as dashed curves.

In the streamer regions, even the low \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) pixels near the outer edge see some polarized light so that the relation \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\) is not entirely random. In Figure 13 we can therefore determine meaningful polarization angles almost to the outer edges of these regions. In Figure 14, the low \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\)-valued pixels (blue) in these regions remain still somewhat concentrated near their nominal positions.

In the polar azimuth sections, on the other hand, \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) is practically unpolarized. Yet there are some few pixels with \(S_{P}\) just above the \(0.71\,\sigma _{P}\) threshold, but they are mostly scattered over all polarization angles. We assume that these pixels arise from statistics because for a given pixel the value of \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) has a considerable uncertainty and there is a finite probability that some pixels with \(S_{P}\) exceeding \(0.71\sigma _{P}\) may occasionally be observed even in the polar regions with very little K-corona and practically unpolarized light. In these polar sections, the relation between \(S_{Q}\) and \(S_{U}\) should be completely random. However, the polarization angle distribution shows an enhancement roughly by a factor 2 near \(\alpha =0^{\circ }\) and \(\pm 60^{\circ }\). These pixels can be traced back to intensity vectors \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) for which one element happens to be much larger than the other two. The enhanced probability of these pixels is again a statistical artifact and we could qualitatively reproduce for unpolarized \({\boldsymbol{I}}\), discarding \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\)-values below a fixed threshold and \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) rising with \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) as for photon noise.

We have classified the data from every pixel in regions 4 and 5 according to their value \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) and constructed for each class the distribution of the error \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) of the polarization angle. The result is displayed in Figure 15. We also compare the measured distributions with the theoretical PDF in Equation 21 indicated by the dashed curves in Figure 15. The important polarization brightness parameter \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) in Equation 19 was in each class set to \(s=2/3\,s_{\mathrm{low}}+1/3\,s_{\mathrm{up}}\) where \(s_{\mathrm{low}}\) and \(s_{\mathrm{up}}\) are the lower and upper bounds, respectively, because the number of pixels decreases with \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). This weighting roughly represents the gradient of the \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) occurrence distribution at medium values \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\approx 3\). The \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\)-range of the respective classes is given in the legend of Figure 15.

Logarithm of the distribution of the angular deviation \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) of observed polarization angles in Figure 13 in regions 4 and 5 for different classes of the normalized polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). The color refers to the respective brightness class as given in the legend. The dashed lines are the respective theoretical PDFs from Equation 21 with parameter values \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) one third from the bottom and two thirds from the top boundary of the respective brightness interval. For \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}>12\), we used \(\overline{S_{P}}/ \sigma _{P}=15\) as parameter in Equation 21.

We used the PDF with isotropic covariance here, because the pixels in regions 4 and 5 span a wide range of polarization angles. So some of the discrepancy between observed and predicted polarization angle errors might be due to the fact that the polarization angles are not equally averaged over in regions 4 and 5. The predictions match again well except that the observed distributions are slightly shifted in \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) and their widths appear slightly wider than observed. We again applied \(\chi ^{2}\) goodness-of-fit tests to compare the observed and predicted distributions. The results are listed in Table 2. All p-values are way below 0.01, but the effect sizes at least for lower \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\)-values promise a closer agreement between the observed distribution and the theoretical PDF. Again, the major reason for the discrepancy is apparent from Figure 15: the variance parameter \(\sigma _{P}\) derived from \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) slightly underestimates the width and the observed distributions are slightly shifted from the center \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }=0\). In view of the uncertainty of the intensity–variance relation in Equation 27 which directly affects the normalization of the observed polarized brightness \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\), we still find that the agreement between the observed angular distributions and the predicted PDF in Equation 19 is acceptable.

For a more quantitative comparison of the mean polarization angle error and its standard deviation, we have binned the brightness in regions 4 and 5 more closely in classes from \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}=0.71\) to 15.21 in steps of 0.5. We determined the empirical distribution of the polarization angle for each class and calculated its circular mean and standard deviation as defined in Equation 25. The result is presented in Figure 16 by the step-like curves. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation of the respective measured estimate assuming that the polarization angle errors are normally distributed.

Top: Logarithm of the measured standard deviation \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) of the polarization angle error versus the mean \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) of the brightness interval for which \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) was averaged. Again data from regions 4 and 5 was used. For comparison, the theoretical standard deviation from PDF in Equation 21 (black dashed) and \(\sigma _{\alpha \infty }\) from Equation 23 (red short dashed) are plotted. Bottom: The measured mean polarization angle error for the same \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) intervals as above. The width of the normalized brightness intervals on the abscissa is 0.5. The error bars represent the standard deviation uncertainty of the respective estimate in each interval.

In the upper diagram we show the measured circular standard deviation of the polarization angle error derived according to Equation 25. It is slightly larger than the theoretical values derived from Equation 21 or from its asymptotic approximation Equation 23 (overplotted as black and red dashed curves, respectively). As to be expected, they all decline with the mean of \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) for the respective class. For \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}>\) about 8, however, the decrease of the measured \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) does not continue quite as steep as expected which leads to an enhanced separation between measured and expected standard deviation.

In the lower diagram of Figure 16, we present the deviation of the mean polarization angle for each class from the local true angle \(\overline{\alpha }\). We find a systematic angle error of about \(-1^{\circ }\) at all levels of the polarized brightness. The error bars here represent the standard deviation of the measured mean angle error and is about \(1/\sqrt{n}\) times the standard deviation from the diagram above with \(n\) the number of pixels contributing to the mean. The small error bars and the fact that the mean angle error persists over the whole range of polarized brightnesses indicate that the \(-1^{\circ }\) deviation is clearly significant. Note that the measured standard deviation in the top diagram is the deviation from the measured mean shown in the bottom diagram. It therefore does not include the \(-1^{\circ }\) shift from \(\overline{\alpha }\) and the increased distance between measured and theoretical \(\sigma _{\alpha }\) cannot be explained by this shift.

4 Summary and Discussion

We have derived PDFs of the polarized brightness \(S_{P}\) and of the deviation of the polarization angle \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) from the expected orientation parallel to the closest limb. The PDFs are applicable to data from a coronagraph which measures the polarization state by three successive intensity measurements \({\boldsymbol{I}}=(I_{0}, I_{60},I_{120})\) through linear polarization filters mutually rotated by 60∘. The basic assumption is that the uncertainty of the polarized brightness and polarization angle is due to the noise of the directly observed image intensities alone. In general, the PDFs depend on the vector of the true polarized intensities \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) and their variances \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\). Since only the polarized brightness matters here, an equivalent set of parameters are the true Stokes components \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{P}=( \overline{S}_{Q},\overline{S}_{U})\) and their covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\). If high precision is not required or the polarization is low, an isotropic approximation \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\rightarrow \sigma _{P}^{2}\boldsymbol{1}\) still leads to useful representations of the PDFs. For the random variables \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}\) or \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) they depend only on the signal-to-noise parameter \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). The variance parameter \(\sigma _{P}^{2}\) is defined in Equation 11 and approaches the true variance of \(S_{P}\) for large \(\overline{S}_{P}/\sigma _{P}\). The asymptotic variance of \(\alpha -\overline{\alpha }\) is \(\sigma ^{2}_{\alpha ,\infty }= \sigma _{P}^{2}/4 \overline{S}^{\raisebox{-0.4ex}{$2$}}_{P}\) (in rad2).

The PDFs allow one to estimate the statistical uncertainty of polarization data products from coronagraphs and, by comparison with the observed variance of the polarization data, can also help to detect error sources of the instrument which do not originate in the presumed noise from the image detection.

A basic result which is obvious but often yet unnoticed is that the polarized brightness estimate from the data of a single pixel or from an average over a small pixel area can be heavily biased towards larger values. With the PDF in Equation 13, this effect can be quantified and we derived corrections Equation 17 which reduce the bias of the PDF mean and the argmax PDF values to a large extent, although not the uncertainty of \(S_{P}\). The bias affects most strongly the polarized brightness when \(S_{P}<2\sigma _{P}\). Here we recommend to improve the signal-to-noise ratio by a local or temporal averaging of the primary measurement vector \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) rather than averaging the \(S_{P}\) values, because \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) are normally distributed and their mean values are unbiased. The averaging should include so many pixels that the effective parameter \(\sigma _{P}\) shrinks below about \(S_{P}/2\).

The problem is even worse for the degree of polarization \(p=S_{P}/S_{I}\) which depends on a further random variable, the total brightness \(S_{I}\). Since \(p\) is often used to estimate the distance of the coronal scattering site off the plane-of-the-sky, it is a key parameter in 3D coronal density reconstructions. To illustrate the problem, we show in Figure 17 the distributions of pixel values of \(p\) in regions 1 to 3 and compare it with the much more reliable value obtained by calculating the degree of polarization from the regional averages of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\). For noise-free measurements there is the obvious constraint \(S_{P}^{2}=S_{Q}^{2}+S_{U}^{2} \le S_{I}^{2}\) and an analog constraint for the elements of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) since it is connected to \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) by Equation 1. If noise is added, the elements of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) and similarly of \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) become statistically independent and the above constraint cannot be guaranteed any more. As a consequence, the measured degree of polarization may exceed unity.

In this paper, we have compared the PDFs with distributions of the polarized brightness and the polarization angle determined from data of the STEREO-A/ SECCHI-COR1 instrument. The observations were made during 18 May 2008 when the corona showed quiescent streamers above the eastern and western equator.

For many detectors, the \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) depend on the measured intensities \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) by an intensity–variance relation characteristic for the detector, often represented by the photon transfer curve (PTC). For the observations used here, this relationship is complicated by the fact that a relatively large background component has to be subtracted from the detected images to obtain the science data \({\boldsymbol{I}}\). The intensity \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) including the more or less unpolarized background had to be used to establish the intensity–variance relation. Since \({\boldsymbol{J}}\) is only little polarized, the resulting variance vectors \(\boldsymbol{\sigma }^{2}_{{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) are well balanced and yield almost isotropic covariance matrices \(\boldsymbol{\Lambda }^{-1}\) with the off-diagonal element well below 10% of the smallest diagonal element even where the polarization of \({\boldsymbol{I}}\) is large.

We find not unexpectedly that the image noise estimated from the intensity-noise relation dominates the uncertainty of the polarization data for STEREO-A/SECCHI-COR1. The observed distributions of the polarized brightness and the polarization angle agree in general with the expected PDFs besides a slight underestimate of the predicted uncertainty in most cases. We consider the agreement as adequate even though the \(\chi ^{2}\) goodness-of-fit test failed in all but one comparison. We assume that the data is too inhomogeneous to meet the restrictive requirements of the test and moreover, the PDF parameters were not optimized for the comparison.

We have found two noticeable discrepancies of the polarization angle error from the theoretical PDF. The expected decrease of the polarization angle error with normalized polarized brightness agrees with our calculation up to about \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}=10\). Beyond this value the standard deviation still continues to decrease but less rapidly than expected. At \(S_{P}/\sigma _{P}=15\), the measured standard deviation goes down to about \(\pm 2.5^{\circ }\), the value which should be reached in accordance with our noise estimate is \(\pm 1.8^{\circ }\). This small discrepancy could be caused by an additional noise source not included in the intensity–variance relation Equation 27 and becomes only visible where the influence of our noise estimate becomes sufficiently small. Alternatively, this effect may in principal also have been caused by underestimating the noise in the intensity–variance relation Equation 27 for the higher pixel intensities. We do not see evidence for this in the fit curve of Equation 27 in Figure 8.