Abstract

This paper explores the dynamics of social exclusion as measured by material and social deprivation in the particularly exposed category of single-parent households. We aim to assess whether there is true state dependence in deprivation and the role of other household factors, as well as that of the macro-economic and social welfare scenario. We use 2015–2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions longitudinal data to explore a large set of European countries. We estimate three-level dynamic probit models that enable us to account for micro- and country-level unobserved heterogeneity. Our results suggest that material and social deprivation is likely to be a trap for single-parent households and that this effect is stronger for these households than for those composed of two adults and children. Among single-parent households, those headed by a female are worse off than those headed by a male. The policy implications of these findings are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the micro-econometric analysis of poverty and social exclusion persistence has received considerable attention. Persistence is of particular concern as it represents a more serious threat to full participation in society with respect to occasional poverty/social exclusion spells (Biewen, 2014). Persistent poverty can reflect individual heterogeneity associated with some observed or unobserved characteristics or can become a trap: once poor, the probability of being poor in the future increases, all other things being equal (Copeland & Daly, 2012). Discriminating between heterogeneity and true state dependence (the trap) has relevant policy implications (Poggi, 2007).

The poverty burden is distributed unevenly across society. There are geographical divides, and specific social groups may suffer from it more than others. The same can be said of poverty persistence. Fabrizi and Mussida (2020), for instance, study poverty and social exclusion persistence in households with children, analyzing data from Italy. In this work, we restrict our focus to single-parent households and we analyze data from a large set of European countries.

We are interested in single-parent households as they are particularly exposed to poverty across the whole of Europe (Chzhen & Bradshaw, 2012; Eurostat, 2018). These households, which are growing in number in many countries, are fragile in many respects (Treanor, 2018), and analyzing the dynamics of poverty in this group is useful to help devise new policies aimed at their full social integration (Israel & Spannagel, 2019). Single-parent households are characterized by the gender of the only adult, and previous literature has provided evidence that those headed by females are disadvantaged with respect to those headed by a male in terms of both the prevalence of poverty and its severity (Maldonado & Nieuwenhuis, 2015; Taylor & Conger, 2017; Wimer et al., 2021).

As a measure of poverty (and more broadly, of social exclusion) we consider the material and social deprivation rate recently introduced into Eurostat’s official set of indicators of social exclusion (Guio et al., 2016). This measure includes both individual-level and social interaction deprivation dimensions, which can be particularly relevant for lone-parent households. In our data, we do not have the information to calculate the indicator of material and social deprivation for children introduced by Guio et al. (2018). Thereby, our analysis is not specifically about children’s deprivation. However, children are included in our sample as members of single parent households we target in our research.Footnote 1

We put forward three main research questions: first, we want to assess whether there is true state dependence with respect to material and social deprivation for single-parent households; second, we would like to know whether this state dependence effect is weaker or stronger compared to other households with children. To this aim, we conduct our analyses both on single-parent households and on households with two adults (both under 65 years of age) and children. The third research question is whether state dependence is stronger for single-parent households headed by females once the role of observable heterogeneity sources are accounted for.

Our novelties should be summarized as follows: (i) we analyze the material and social deprivation indicator recently adopted by the European Union and (ii) we do so for a specific household type, i.e. single-parent households in Europe, (iii) with a particular emphasis on female-headed single-parent households. At least to our knowledge, no studies explored the issue of material and social deprivation state dependence for this type of household. We aim to fill this gap in the literature.

Our analysis encompasses all countries for which European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) longitudinal data from the 2015–2018 panel are available. A longer panel would be more informative for the study of state dependence, but working on EU-SILC allows a broader geographical scope and the focus on a widely accepted and popular indicator. For a detailed discussion of EU-SILC panel data limitations, see Bossert and D’Ambrosio (2019).

From an econometric point of view, we apply a three-level correlated random effects dynamic probit model with endogenous initial conditions, following Wooldridge (2005), as extended to multi-level analysis by Bosco and Poggi (2020) (see Sect. 4 for details).

Single-parent households are heterogeneous (Gornick et al., 2022) in many respects. We aim to separate genuine state dependence from the impact of micro-level characteristics such as composition of the household, gender, education level, work intensity, income and other variables. We also consider some macro-level variables that could influence the individual deprivation status. In particular, we include two national-level variables characterizing different welfare regimes in terms of cash and in-kind transfers (Bosco & Poggi, 2020).

Our main finding is that there is genuine state dependence for single-parent households and that this effect is significantly stronger for these households than for those composed of two adults with children. Among single-parent households, those headed by a female suffer for a stronger trap effect when compared to those headed by males.

In terms of policies, our results suggest that interventions and measures targeted at single-parent households are needed. Specifically, defamilization measures such as work and family duty reconciliation policies, as suggested by Israel and Spannagel (2019) and Zagel and Van Lancker (2022), might play a role in helping single-parent households escape material and social deprivation.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the relevant literature is reviewed; in Sect. 3, we introduce the data we analyze and present some relevant stylized facts about material and social deprivation in Europe. The econometric model is described in detail in Sect. 4, while Sect. 5 offers stylized facts and a description of the results with some interpretative clues. Section 6 concludes the paper with a discussion of the policy implications of the main findings.

2 Literature

In this work, we aim to assess whether there is true state dependence in material and social deprivation. The concept of state dependence in a status of material and social deprivation refers to the persistence of material and social deprivation over time, meaning that an individual’s current deprivation status is influenced by past experiences of deprivation. In other words, a person’s likelihood of being deprived today is influenced by their deprivation status in the past. State dependence can occur for a variety of reasons, including limited access to resources and opportunities, either due to individual characteristics such as a lack of skills and education or to those of the place where he/she lives (remoteness, poor infrastructures, economical disadvantage; see for instance Kraay & McKenzie, 2014) or to social and cultural norms that perpetuate deprivation. It can create a vicious cycle of deprivation that is difficult to break, as individuals who are currently deprived are more likely to remain in this condition in the future. More specifically, we have true state dependence in deprivation when the past experience of deprivation has a structural effect on the probability of experiencing that event in the future, regardless of other individual characteristics (Heckman, 1981). Understanding state dependence is therefore important for designing effective deprivation reduction policies and programs.

In 2018, the material and social deprivation rate computed for the European Union (28 countries) was 12.8%. For people living in single-parent households the situation was much worse, with the rate reaching 26.9%, while on average, households that include two adults and at least one dependent child were in line with the overall population (11.57%).Footnote 2 The situation in 2018 represents an improvement with respect to previous years. At the beginning of the period we consider, in 2015, the rate for single parent households was 34.7%, more than double that of couples with children (on average, 16.53%), as the former were hit harder by the Great Recession than the latter.

While there is a strand of literature analyzing longitudinal poverty (for a review, see Fusco & Van Kerm, 2022), with some studies focused on specific countries (such as Ayllón (2013) on Spain, Biewen (2009) on Germany, Devicienti et al. (2014) on Italy, Giarda and Moroni (2018) on Italy, France, Spain, and the UK), and others looking at larger regions such as the whole European Union (e.g., Bárcena-Martın et al. (2017); Bosco and Poggi (2020)), there are few studies investigating material deprivation using a dynamic approach (Poggi, 2007; Fabrizi & Mussida, 2020; Bossert & D’Ambrosio, 2019). In recent years, awareness of the limitations of the conventional income-poverty approach has increased and more attention has been placed on the role non-monetary measures of material deprivation can play in improving our understanding of poverty and social exclusion, with the aim of designing more effective anti-poverty policies (Whelan & Maître, 2012). Moreover, material deprivation indicators are useful for country comparisons because, contrary to relative monetary poverty indicators, they reflect absolute aspects of poverty (Dudek, 2019).

The literature on material deprivation primarily elaborates on its determinants (e.g., Bárcena-Martín et al. (2014)), sometimes by offering a comparison with those of income poverty (Verbunt & Guio, 2019). Bárcena-Martín et al. (2014) investigate the extent to which differences in the characteristics of individuals (micro-level perspective) and country-specific factors (macro-level perspective) can explain country differences with respect to material deprivation levels. They use EU-SILC data from 2007 for 28 European countries. Their results suggest that country-specific factors seem to be much more relevant than individual effects in explaining country differences in material deprivation. Verbunt and Guio (2019) use 2012 cross-sectional EU-SILC data for 31 countries to estimate single-level and multi-level multinomial logistic regression models and adopt the Shapley decomposition method to compare the relative contribution of independent variables at the household and country level to within- and between-country explained variance measures. Their findings suggest that household work intensity and educational attainments are important determinants of severe material deprivation.

Few works try to disentangle the contribution of genuine state dependence and (observed and unobserved) heterogeneity with reference to social exclusion or material deprivation (Poggi, 2007; Fabrizi & Mussida, 2020). Poggi (2007), for instance, investigates the dynamics of state dependence, i.e., whether being in a state of social exclusion (or, more generally, at high risk of multi-dimensional deprivation) at any given time depends on the experience of social exclusion. The author estimates a dynamic logit model on European community household panel (ECHP) data (1994–2001) for Spain. The results suggest that state dependence in social exclusion holds to a significant extent in Spain.

Fabrizi and Mussida (2020) offer a comparative longitudinal analysis of at-risk-of-poverty, severe material deprivation, and subjective poverty in Italy using the 2013–2016 longitudinal sample of the EU-SILC survey. They apply correlated random effects probit models with endogenous initial conditions to assess genuine state dependence after controlling for structural household characteristics and variables related to participation in the labor market. They investigate state dependence in the poverty measures as well as possible differences in their determinants, finding evidence of genuine state dependence for all measures considered.

Given the increasing and renewed importance of material deprivation, we are interested in studying it from a longitudinal perspective, since its dynamics might involve genuine state dependence as well (Verbunt & Guio, 2019). Further, here we analyze the more recent material and social deprivation indicator (for details, see Sect. 3) for a specific household type, namely single-parent households in Europe, with a particular emphasis on female-headed single-parent households.

Indeed, the majority of single-parent households are headed by women, and they are more likely to face lower wages (they are more likely to be employed in precarious low-paid jobs), less work experience, and fewer career opportunities (see, for instance, Bertrand et al 2010, Mussida and Patimo, 2021) . Related to their often limited financial means, single parents—and especially females—are more likely than coupled parents to experience material deprivation (Chzhen & Bradshaw, 2012; Treanor, 2018).

3 Data and Definitions

We analyze data from the balanced 2015–2018 EU-SILC panel for twenty-three European countries for which the material and social deprivation indicator can be computed.Footnote 3 The EU-SILC survey is conducted in most European countries using harmonized questionnaires and survey methodologies. Rotating panel survey designs are used, with an overlap between the samples of two successive waves of 75%; the panel duration is four years. The fresh portion of the sample (25%) is drawn according to designs that vary from country to country, with stratified multi-stage sample designs being the most common choice (Verma & Betti, 2006).

In line with EU-SILC methodological guidelines, we define as single-parent households those composed of one adult (an individual older than 24 years or aged between 18 and 24 years but economically active) and at least one dependent child (an individual younger than 18 or between 18 and 24 years old but economically inactive).

As anticipated in the Introduction, we compare the findings for single-parent households to those pertaining to households including two adults aged up to 65 years of age (in most cases, a couple) with children. We focus on these households and not on all households with children not classified as single-parent because of the demographic heterogeneity of this complementary category would hinder interpretable comparisons. The units of analysis for the present study are the members of households classified as single-parentFootnote 4 and/or two adults with children households.

Our variable of interest is the material and social deprivation indicator. The European Commission (Europe 2020 strategy) and the United Nations (2030 Agenda) indeed recommend the monitoring of a number of indicators of social exclusion (Guio et al., 2012; Commission, 2014). The material and social deprivation indicator is among the most important ones. It is based on 13 selected deprivations (items) defined either at the individual or the household level. Individual items come from an individual questionnaire (one for each adult in the household), household items form household questionnaire (one for each household). Each item is based on the idea of an enforced lack, so an individual/household is deprived with respect to an item if he/she cannot afford the specific good or is not capable of the specific social activity/interaction (Guio et al., 2017). The full list of items included in the indicator is provided in Table A1 in the supplementary material (for details, see Sect. 5.1).Footnote 5

According to Eurostat guidelines, an individual is defined as materially and socially deprived if he/she suffers from a lack of at least 5 out of 13 items. Since in the EU-SILC survey information on the personal deprivation items is collected for individuals aged 16 or over, a child in a two-parent household is considered deprived if one of the parents lacks at least 5 out of 13 items (independent of the second parent) (European Commission, 2017). In single-parent households, a child is attributed the deprivation level of the caring adult.

3.1 Variables Used to Model Heterogeneity

Table A2 in the supplementary material reports the full list of variables used to model observed heterogeneity, whereas Table A3 shows the (weighted) descriptive statistics for these variables for the analysed samples of two adults with children and single-parent households, which comprise 16,182 and 9397 observations, respectively. In what follows, we comment on the statistics for single-parent households, as these are the main focus of our work.

The dependent variable is the dichotomous material and social deprivation status defined at the individual level following Eurostat guidelines, as described in Sect. 3. From Table A3, we see that 26.9% of our sample of single-parent household members is deprived.

The variables used to model observed heterogeneity that could have an effect on an individuals’ deprivation status cover different levels of aggregation. In the model, we include characteristics of the head of the household as well as household characteristics. Moreover, to account for the influence of the socio-economic context on individual deprivation, we also include macro-economic variables measured at the national level

According to the model strategy explained in Sect. 4, we include the lagged deprivation status and the related initial condition. Moreover, since our research question concerns the extra risk of single-parent households in terms of deprivation level and persistence, we include a dummy identifying if the household is a single-parent household at time t and its lag. This choice also allows us to capture household’s composition dynamics typical of single-parent households. Further, we consider some characteristics of the head of the household, i.e. the adult with the highest wage in the household. These include gender, educational attainment level, health condition, and home ownership (Whelan et al., 2003; Verbunt & Guio, 2019; Fabrizi & Mussida, 2020). Interestingly, and in line with expectations (Liu & Esteve, 2021), most single-parent households are headed by females (77.8%).

Among the household-level characteristics, we consider household income as a measure of the level of household’s resources. In detail, we include the ratio between the equivalised household income and the poverty line for each country explored. Our choice is motivated by at least two reasons. First, the equivalised household income accounts for all the household members, i.e. children as well as single or two-adults. Second, accounting for each country poverty line makes the equivalised household income comparable across the set of countries investigated.

We also include household’s work intensity, which allows us to control for labor market attainment (Verbunt & Guio, 2019; Fabrizi & Mussida, 2020). More specifically, work intensity is calculated as the ratio between the number of months that all household members of working age worked during the income reference year and the total number of months that could theoretically have been worked by the same household members. The adopted measurement of work intensity accounts for part-time employment, down-weighting by 0.5 the total worked months for individuals working part-time. It is worth noting that, according to Eurostat guidelines, work intensity is only calculated for individuals of working age, defined as persons aged between 18 and 64 years who are not classified as dependent children. Thus, work intensity is not calculable for children aged less than 18 years of age, adults aged 65 or over, and dependent children, defined as individuals aged 18–24 years who are economically inactive and living with at least one parent. The work intensity should take values between 0 and 1, and we group them into three classes, defined as [0, 0.2], (0.2, 1), and 1. The first class enables us to identify the very low work intensity indicator, defined by Eurostat as the individual working less than 20% of the total working time potential during the previous year. This is one of the three indicators, together with at-risk-of poverty or social exclusion and severe material deprivation, used by the European Commission to monitor social exclusion (Atkinson et al., 2017). Work intensity, therefore, is computed at the household level and distributed afterwards at the individual level, including to children and youth which are not taken into account in the numerator and denominator of the computation. So only in the case of households composed only by youth, children or old-age people work intensity is not calculable. Young, i.e. children aged [0–18), represents a substantial part of our sample (i.e., 54.7% of the sample of single parents; see Table A3). Despite our analysis is not specifically on children’s deprivation, as explained in the Introduction, we decided to keep children in our sample. Another set of household-level characteristics pertains dummy variables accounting for the presence of children in different age ranges (\(0-5\), \(6-14\), and \(\ge 15\)), as well as for the presence of three or more dependent children (larger households).

The last set of variables included in the model specification are defined at the macro level. They aim to capture the strong heterogeneity that characterizes European countries in terms of national welfare regimes, which could affect an individual’s deprivation status. More specifically, the model includes two variables that account for the per capita public expenditure in terms of in-kind and in-cash social transfers.

4 Model

To study the persistence of deprivation in our balanced panel, we adopt a dynamic panel model in line with Wooldridge (2005). Dynamic panels can be read as two-level models with individual-specific effects accounting for correlation between successive observations pertaining to the same individual. Moreover, following (Bosco & Poggi, 2020) we introduce a further hierarchical level to model the correlation induced between observations from the same country by the unobserved heterogeneity not accounted for by the household-level and macro-economic variables. As a result, our model can be read as a multi(three)-level dynamic panel model.

Our target variable y is dichotomous: For individual i in country k at time t, we have that \(y_{ikt}=1\) if he or she is materially and socially deprived and \(y_{ikt}=0\) otherwise. A probit link is used to relate the observed dichotomous variable to regressors. A first specification proposal can be expressed as

where \(i=1,\dots ,N\); \(k=1,\dots , C\); \(t=1,\dots ,T\) (here \(T=3\)); \(\Phi\) is the cumulative distribution function of an N(0, 1) random variable, while \(z_{ikt}\) are time-varying explanatory variables and \(\gamma\) and \(\rho\) are parameters to be estimated. Note that \(\rho\) is our main parameter of interest since it can be interpreted as the magnitude of true state dependence in terms of individual material and social deprivation. The term \(a_{ik}\) is the individual-specific effect modelled as a random intercept; similarly, \(v_k\) is a country-specific intercept. Note that there is no time-specific error term included in the model. The assumptions of first-order dynamics conditional on \(z_{ikt}, y_{ik},a_{ik}, v_{k}\) and linearity are in line with most of the literature.

Notoriously, the estimation of parameters in (1) can suffer from bias due to initial condition problems as the process generating deprivation statuses does not start with our first observation period. In line with Wooldridge (2005), we propose to solve this problem by conditioning on the deprivation status at \(t=0\); this solution also allows for correlation between observed and unobserved individual characteristics provided that the unobserved characteristic influences both the observed characteristic at time \(t>0\) and at the initial time \(t=0\). Specifically, for the individual-specific effect we assume

where \(z_{ik}\) are time-invariant individual characteristics. A similar assumption is made for the country-specific effect, but in this case we do not include time-invariant country-level variables. Our final specification can be expressed as follows:

An important tool for investigating the opportunity of multi-level modelling is the intra-class correlation coefficient (Rodriguez & Elo, 2003). In the case of our probit model, we are interested in

where \(\sigma ^2_k\) is the variance component associated with \(v_k\), the country-specific intercept.

It is worth noting that the model is estimated without considering the sampling weights, for two main reasons. The first is that we do not have access to all the relevant sampling design information (i.e., the stratum and cluster identifiers) that would be needed to obtain consistent estimates of standard errors associated with weighted estimators of model parameters.

The second reason is that, following the procedure proposed by Pfeffermann and Sverchkov (1999), we tested the assumption that the sampling design is non-informative given the covariates, with the result that we cannot reject that hypothesis. A more detailed discussion can be found in Fabrizi and Mussida (2020).

It is worth noting that, to ease the interpretation of the results, we calculated the average marginal effects (AMEs). They allows us to interpret the estimates as the average change in the probability of being deprived at a change in the explanatory variable, thus being interpretable in terms of percentage points (pp.).

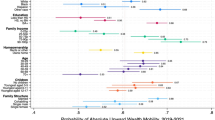

In the Appendix, we offer some robustness checks. We conduct the analysis on the sample of single-parent households separately by gender of the head of household to pinpoint the disadvantage of females (Table A4). Then, we explore the conditions of female heads of household by household type, i.e., single-parent households and those with two adults, to see whether female-headed single-parent households suffer more (Table A5). Moreover, we explore both regional and country heterogeneity in single-parent household deprivation. By making reference to two large regions obtained by partitioning the countries of our sample into two groups, i.e., North-West and South-East, we explore across-country heterogeneity (Table A6). Finally, we estimate the model by including interactions between lagged deprivation and country dummies to further explore the phenomenon under investigation across countries (for the interactions, see Figure 1, for the other covariates, see Table A7).

5 Results

5.1 Material and Social Deprivation in Europe: Stylized Facts

Table A1 in the supplementary material shows the share of deprived individuals according to each item for two adults with children and single-parent households, and within the single-parent household type for male-headed and female-headed households. In general, we note that the prevalence of deprivation for individuals in single-parent households is higher for all items compared to those with two adults and children.

From Table A1, we note that the item “face unexpected expenses” is the one with the highest share of deprived individuals for all household types. The percentage ranges from 27.53% for two adults with children to 59.24% for female-headed single-parent households.

Specifically, among items defined at the household level, we note that the disadvantage for (female-headed) single-parent households is especially important for “have access to a car”: the share for (female-headed) single-parent households is almost (five) four times higher with respect to that of other households with children (17.54% and 3.62%, respectively). From Table A1, we note that among individual-level deprivation items, the relative disadvantage of single-parent households is particularly pronounced for one item related to a strictly personal dimension (“replace worn-out clothes with some new ones”), but also for three out of four items related to the social interaction dimension of deprivation. These figures show that to explore deprivation in single-parent households—and more generally their risk of social exclusion—considering the new indicator for material and social deprivation can be very relevant as the roles of the personal and social interaction dimensions of deprivation are not negligible for this type of household.

Given the large sample sizes, we tested the equality of proportions using a standard asymptotic z-test comparing both two-adult vs. single-parent households and male- vs. female-headed single-parent households. All pairs of proportions differ significantly in all cases (p values always below 0.01). These results imply that single-parent households are more disadvantaged in terms of deprivation compared to the category of two adults with children and that within single-parent households, those with a female head of household are the most fragile. These findings stimulated our econometric investigation, which explores the categories of two adults with children and single-parent households (base model), as well as, within the single-parent category, male- and female-headed households. As mentioned in the Introduction, the period of observation of the EU-SILC panel is relatively limited, only 4 years. For an appropriate study, it should be longer than 4 years. Unfortunately, a similar statistical source, harmonized for all the EU countries is not available for a longer time period. Our results should be interpreted by keeping in mind this limitation.

5.2 Model Estimation Results

Table 1 shows the average marginal effects (AMEs) for the three-level dynamic probit model with correlated random effects estimated on households with children, i.e., two adults with children and single- parent households. In Table 2, we focus on single-parent households only, to assess the effect of the gender of the head of household on our variable of interest, i.e. material and social deprivation.

As shown in the top panel of Table 1, we find evidence of genuine state dependence (+7 pp.). Notably, we see that for single-parent households, both currently as well as in the previous time period, is positively associated with the probability of being materially and socially deprived (+3.4 pp. and +1.4 pp.) for being single-parent in the current and previous time period, respectively). The fact that lagged deprivation has a significant effect on current deprivation suggest the presence of state dependence in material and social deprivation. The concept of state dependence in a status of material and social deprivation, as explained above, refers to the persistence of material and social deprivation over time, meaning that an individual’s likelihood of being deprived today is influenced by their deprivation status in the past. This should create a vicious cycle of deprivation that is difficult to break, as individuals who are currently deprived are more likely to remain in this condition in the future. The mechanisms behind this trap are associated with the limited access to resources and opportunities. This should be either due to individual characteristics, i.e. lack of skills and education, or to those of the place where he/she lives, i.e. remoteness, poor infrastructures, economical disadvantage, or to social and cultural norms that perpetuate deprivation.

State dependence in material deprivation was also found, for instance, by Poggi (2007) for individuals in Spain and by Fabrizi and Mussida (2020) for households with dependent children in Italy.

As for the effect of the gender of the head of household on genuine state dependence, from Table 2 it is clear that genuine state dependence is confirmed when focusing on the sub-sample of single-parent households (+12.2 pp.) and that this effect is stronger for households headed by females (+4.8 pp.).

With respect to the three main research questions outlined in the Introduction, we can state that i) we have clear evidence of state dependence when studying the dynamics of material and social deprivation; ii) this evidence is stronger for single-parent households than for households where children live with two adults; and iii) single mothers experience stronger genuine state dependence with respect to single fathers.

Going back to the analysis in Table 1, we now briefly discuss results related to initial conditions and household heterogeneity. Initial conditions play a statistically significant role (+12.5 pp.). This entails endogeneity of initial conditions for material and social deprivation, meaning that the observed initial deprivation status is associated with unobservable factors and must be controlled for, as in our model specification.

Table 1 suggests that the risk of being materially and socially deprived also depends in part on observed household heterogeneity. We consider characteristics of the head of household, household characteristics, and macro indicators.

As for the former, we note that being a female head of household is positively associated with material and social deprivation (+1.7 pp.). This might be particularly relevant for single-parent households (Bradshaw & Nieuwenhuis, 2021) as female-headed single-parent households represent an important percentage of total single-parent households in our sample (77.9% of single-parent households are headed by a female, see Table A3). Nonetheless, the existing literature suggests that single-parent households, and especially those headed by a female, are more likely than two-parent households to experience material deprivation (see, for instance, Chzhen and Bradshaw (2012); Treanor (2018)).

Higher education reduces the risk of material and social deprivation. From Table 1, we note that being a tertiary-educated head of household is negatively associated with the risk of material and social deprivation (\(-\)3.5 pp.). This is consistent with previous findings in the literature (Verbunt & Guio, 2019; Fabrizi & Mussida, 2020). We also note that the head of household experiencing poor health is positively associated with the risk of being materially and socially deprived (Bosco & Poggi, 2020; Fabrizi & Mussida, 2020), while home ownership reduces the probability (Fabrizi et al., 2023).

Moving to household characteristics, our measure for household income (see Sect. 3.1 for details), that is a proxy for the level of household’s resources, is negatively associated with the risk of deprivation (\(-\)6.6 pp.).

Specifically, work intensity plays a role in line with expectations (Bárcena-Martın et al., 2017). Living in a (quasi-)jobless/very low work intensity household, i.e. household where on average working-age adults work 20% or less of their total work potential during the past year, increases the risk of being deprived (+3.5 pp.). As mentioned in Sect. 3.1, the quasi-joblessness is one of the three indicators used by the European Commission to monitor social exclusion. Full employment (\(WI=1\)), instead, reduces the probability of being materially and socially deprived by \(-\)2.7 pp.

We note that while the presence of children of all the age groups decreases the risk of material and social deprivation but with a relatively low magnitude, the presence of three or more dependent children is positively associated with the risk (+2.5 pp.). This result was found in the literature for other indicators of social exclusion (see, for instance, Fusco and Islam (2020) for poverty, and Ferrão et al. (2021) for material deprivation). This pattern can be at least partially interpreted as an effect of the limited effectiveness of transfer programs targeting households with young children in alleviating material and social deprivation (see, for instance, Cancian and Meyer, 2018,Schechtl 2023).

As for macro indicators, we see a negative association between the absolute level per capita of transfers in-kind (in thousands, in pps) and the risk of material and social deprivation (\(-\)3.1 pp.). The negative association between in-kind expenditure (for children) and poverty is well established in the literature (see, for instance, Nygård et al. (2019)). Here, we complement previous analyses by focusing on their role in alleviating material and social deprivation.

It is worth stressing that the estimated variance components associated with both the random intercepts for countries and individuals are statistically significant (bottom of Table 1). In particular, according to the intra-class correlation coefficients defined in Eq. 3 (Sect. 4), we find that the individual and the country levels (significantly) explain about 43 percent and 13 percent of the total variability on the probit scale, respectively. This implies that the proportion of total variability explained by the country level is relatively low but is still relevant. To further assess evidence in favor a multi-level model, we compute a likelihood ratio test comparing the log likelihoods of the two- and three-level models. Results reported in the bottom line of Table 1 show that the difference is statistically significant (Prob Chi\(^2=.000\) ), thereby providing clear support for the adoption of the three-level model, which seems to fit the data significantly better than the two-level one.

From the analysis of Table 2, we note that being in poor health, in a (quasi-)joblessness condition, and the presence of children (of any ages) are positively associated with the risk of material and social deprivation (differently from what we found in Table 1 with the overall sample), while high education, house ownership, and intensive labor market attainment (full employment, \(WI=1\)) are protective factors against the risk of material and social deprivation. Finally, we find a role for the absolute level per capita in pps of transfers in-kind in alleviating the probability.

As a robustness check, we estimate the model separately by gender of the head of household (Table A4 in the supplementary material). We clearly note that female-headed single-parent households suffer a greater risk of state dependence in material and social deprivation compared to male-headed ones (12.2 pp. and 6.2 pp., respectively). Other gender differences refer to labor market attainment, as full employment (\(WI=1\)) is negatively associated with the risk of material and social deprivation for female-headed single-parent households (\(-\)3.5 pp.) while it does not exert a role for male-headed single-parent households. Again, for female-headed households we see a positive and significant association between the presence of three or more dependent children and the risk of material and social deprivation. These effects suggest that policy interventions aimed at easing the labor market participation of females by enhancing the reconciliation of family duties-especially childcare-related ones-and labor, would be successful in reducing the risk of material and social deprivation and, more generally, the social exclusion of the particularly disadvantaged category of female-headed single-parent households. Single-parent households and working mothers, indeed, are more likely to use non-parental care (Coneus et al., 2009). In Table A5, we further explore the conditions of female heads of household by household type, i.e., single-parent and two adults, to see whether female-headed single-parent households suffer more. We note that female heads of a single-parent household exhibit a higher level of state dependence in deprivation compared to female heads of two-adult households (lagged deprivation of +12.2 pp. compared to +6.9 pp.).

To better characterize across-country heterogeneity in terms of institutions, policies, and social welfare, the ideal would be to interact the lagged deprivation variable with country-specific dummies. Most of the results are in line with those of Table 1. Nonetheless, many lagged deprivation—country interaction parameters are non significant because of small country-specific sample sizes. A graphical representation of these estimates, from which no clearly interpretable pattern emerges, is presented Figure 1 (supplementary material).Footnote 6 In order to have broader samples, as robustness check, we conduct our analysis by dividing the countries in two large regions, with the nine most affluent in terms of per-capita GDP and median disposable income, poverty, and deprivation rates on the one side and the remaining fourteen on the other. As these two groups are geographically compact, we label them as North-West and South-East.Footnote 7 We note that the border between the two regions is approximately that of the so-called Hajnal line (Hajnal, 1982). According to the family history literature, in the North-West region young people tend to leave their parents’ homes at an earlier age (Lesnard et al., 2016), divorce/separation rates are high although the difference with respect to the rest of Europe is decreasing (see, for instance, Steinbach et al. (2016)), and working-age people are more likely to live without a partner, both with or without children (Liu & Esteve, 2021). In contrast, the South-East has traditionally been characterized by the presence of multigenerational households, early and almost universal marriage, and therefore, only a small proportion of individuals who never get married (Steinbach et al., 2016). In recent decades, this has been evolving towards later marriages and very low fertility rates (Billari, 2008), but ties between different generations remain strong (Albertini et al., 2007; Albertini & Kohli, 2013).

Table A6 (supplementary material) reports the results for this robustness check in which we estimate our model on the sample of single-parent households including the interaction between lag deprivation and a dummy variable for the South-East group of countries. We note that single-parent households in the South-East suffer relatively lower state dependence in material and social deprivation (\(-\)18.9 pp.) compared to those in the North-East. Nonetheless, the AME is slightly significant also for reasons related to sample size, and therefore, we do not compute estimates separately by gender of the head of single-parent households.

6 Conclusions

In this work, we estimate a three-level dynamic probit model for the probability of being deprived according to the indicator for material and social deprivation. The aim of such a framework is to disentangle the role of genuine state dependence and heterogeneity in explaining social exclusion. We consider samples of single-parent households in European countries, with a focus on those headed by females, and households composed of two adults with children. The motivation for such a choice is that single-parent households exhibit important material and social deprivation rates, so they appear fragile with respect to the other household types, and thus should capture the attention of policy makers. Since women tend to have lower earnings and are more prone to career interruptions, on average (Bertrand et al., 2010), it is not surprising that single-parent households headed by women are more likely to be deprived than single-parent households headed by men or households with two parents. Related to their often limited financial means, single parents—and especially female single parents—are indeed more likely than coupled parents to experience material and social deprivation.

All in all, our results suggest that genuine state dependence in material and social deprivation significantly affects all household types, but especially female-headed single-parent ones. The relatively high state dependence in deprivation of single-parent households, and especially those headed by females, compared to households with two adults and children suggests a need for policy interventions targeted at single-parent households to reduce the incidence of material and social deprivation.

As also suggested by Israel and Spannagel (2019), measures such as family benefits might help reduce the extent of deprivation of single-parent households by socializing the costs of family and care obligations. Overall, there is a need for more effective policies to support lone-parents, such as support to reconcile family and work, extra income from extra child allowances, and tax credits.

Notes

All prevalence indicators published by European Union are headcount ratios with children being considered in the computation.

Figures available from the Eurostat website at https://ec.europa.eu/urostat/databrowser/view/ilc_mdsd02/default/table?lang=en.

The countries explored are Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

We classify as single-parent households those households that are composed of one adult and at least one dependent child for at least one year of the panel.

The material and social deprivation indicator replaced the original material deprivation indicator. This latter was based on a set of nine items referring to the household. The weak reliability of some of these items led to a new set of thirteen items being devised, including new items defined at the individual level. Hence, it broadened the scope of the aspects of living conditions and societal needs considered (Guio et al., 2016). For further details on the official measurement of material deprivation, see Notten and Guio (2023).

The AMEs for the other covariates are reported in Table A7 (supplementary material).

North-West: Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden; South-East: Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland.

References

Albertini, M., & Kohli, M. (2013). The generational contract in the family: An analysis of transfer regimes in Europe. European Sociological Review, 29(4), 828–840.

Albertini, M., Kohli, M., & Vogel, C. (2007). Intergenerational transfers of time and money in European families: Common patterns-different regimes? Journal of European Social Policy, 17(4), 319–334.

Atkinson, A. B., Guio, A. C., & Marlier, E. (2017). Monitoring social inclusion in Europe. European Union: Statistical books.

Ayllón, S. (2013). Understanding poverty persistence in Spain. SERIEs, 4(2), 201–233.

Bárcena-Martın, E., Blanco-Arana, M. C. and Pérez-Moreno, S. (2017) , Dynamics of child poverty in the European countries. In Working paper 437, ECINEQ, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality.

Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2010). Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(3), 228–255.

Biewen, M. (2009). Measuring state dependence in individual poverty histories when there is feedback to employment status and household composition. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 24(7), 1095–1116.

Biewen, M. (2014). Poverty persistence and poverty dynamics. IZA World of Labor (103).

Billari, F. C. (2008). Lowest-low fertility in Europe: Exploring the causes and finding some surprises. The Japanese Journal of Population, 6(1), 2–18.

Bosco, B., & Poggi, A. (2020). Middle class, government effectiveness and poverty in the EU: A dynamic multilevel analysis. Review of Income and Wealth, 66(1), 94–125.

Bossert, W., & D’Ambrosio, C. (2019). Intertemporal material deprivation: A proposal and an application to EU countries. In ‘Deprivation, inequality and polarization (pp. 15–35). Springer.

Bradshaw, J., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2021). Poverty and the family in Europe. In Research Handbook on the sociology of the family, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bárcena-Martín, E., Lacomba, B., Moro-Egido, A. I., & Pérez-Moreno, S. (2014). Country differences in material deprivation in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(4), 802–820.

Cancian, M., & Meyer, D. R. (2018). Reforming policy for single-parent families to reduce child poverty. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 4(2), 91–112.

Chzhen, Y., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). Lone parents, poverty and policy in the European Union. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(5), 487–506.

Coneus, K., Goeggel, K., & Muehler, G. (2009). Maternal employment and child care decision. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(1), 172–188.

Copeland, P., & Daly, M. (2012). Varieties of poverty reduction: Inserting the poverty and social exclusion target into Europe 2020. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 273–287.

Devicienti, F., Gualtieri, V., & Rossi, M. (2014). The persistence of income poverty and lifestyle deprivation: Evidence from Italy. Bulletin of Economic Research, 66(3), 246–278.

Dudek, H. (2019). Country-level drivers of severe material deprivation rates in the EU. Ekonomický časopis (Journal of Economics), 67(1), 33–51.

European Commission. (2014). An indicator for measuring regional progress towards the Europe 2020 targets. Brussels: EC, Committee of the Regions.

European Commission. (2017). The new EU indicator of material and social deprivation, Technical note annex 1 spc/isg/2017/5/4, European Commission.

Eurostat. (2018). Living conditions in Europe, Statistical books, European Union.

Fabrizi, E., & Mussida, C. (2020). Assessing poverty persistence in households with children. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 18(4), 551–569.

Fabrizi, E., Mussida, C., & Parisi, M. L. (2023). Comparing material and social deprivation indicators: Identification of deprived populations. Social Indicators Research, 165(1), 999–1020.

Ferrão, M. E., Bastos, A., & Alves, M. T. G. (2021). A measure of child exposure to household material deprivation: Empirical evidence from the Portuguese eu-silc. Child Indicators Research, 14(1), 217–237.

Fusco, A., & Islam, N. (2020) , Household size and poverty. In Inequality, redistribution and mobility, vol. 28, Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 151–177.

Fusco, A., & Van Kerm, P. (2022). Measuring poverty persistence. Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER) (2022-02).

Giarda, E., & Moroni, G. (2018). The degree of poverty persistence and the role of regional disparities in Italy in comparison with France, Spain and the UK. Social Indicators Research, 136(1), 163–202.

Gornick, J. C., Maldonado, L. C., & Sheely, A. (2022). Single-parent families and public policy in high-income countries: Introduction to the volume. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 702(1), 8–18.

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Marlier, E. (2012). Measuring material deprivation in the EU: Indicators for the whole population and child-specific indicators. In Eurostat methodologies and working papers.

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Marlier, E., Najera, H., & Pomati, M. (2018). Towards an EU measure of child deprivation. Child Indicators Research, 11(3), 835–860.

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Najera, H., Pomati, M. ( 2017). Revising the EU material deprivation variables (analysis of the final 2014 EU-SILC data). Final report of the Eurostat Grant ’Action Plan for EU-SILC improvements’.

Guio, A. C., Marlier, E., Gordon, D., Fahmy, E., Nandy, S., & Pomati, M. (2016). Improving the measurement of material deprivation at the European Union level. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(3), 219–333.

Hajnal, J. (1982). Two kinds of preindustrial household formation system. Population and Development Review, pp. 449–494.

Heckman, J. J. (1981) , Statistical models for discrete panel data. Structural analysis of discrete data with econometric applications pp. 114–178.

Israel, S., & Spannagel, D. (2019). Material deprivation in the EU: A multi-level analysis on the influence of decommodification and defamilisation policies. Acta Sociologica, 62(2), 152–173.

Kraay, A., & McKenzie, D. (2014). Do poverty traps exist? Assessing the evidence. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 127–148.

Lesnard, L., Cousteaux, A.-S., Chanvril, F., & Le Hay, V. (2016). Do transitions to adulthood converge in Europe? An optimal matching analysis of work-family trajectories of men and women from 20 European countries. European Sociological Review, 32(3), 355–369.

Liu, C. Esteve, A. (2021). Living arrangements across households in Europe. In Research Handbook on the sociology of the family, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Maldonado, L. C., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2015). Family policies and single parent poverty in 18 oecd countries, 1978–2008. Community, Work & Family, 18(4), 395–415.

Mussida, C., & Patimo, R. (2021). Women’s family care responsibilities, employment and health: A tale of two countries. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(3), 489–507.

Notten, G., & Guio, A.-C. (2023). Reducing poverty and social exclusion in Europe: Estimating the marginal effect of income on material deprivation. Socio-Economic Review (forthcoming).

Nygård, M., Lindberg, M., Nyqvist, F., & Härtull, C. (2019). The role of cash benefit and in-kind benefit spending for child poverty in times of austerity: An analysis of 22 European countries 2006–2015. Social Indicators Research, 146, 533–552.

Pfeffermann, D., & Sverchkov, M. (1999). Parametric and semi-parametric estimation of regression models fitted to survey data. Sankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics, Series B, 61, 166–186.

Poggi, A. (2007). Does persistence of social exclusion exist in Spain? The Journal of Economic Inequality, 5(1), 53–72.

Rodriguez, G., & Elo, I. (2003). Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. The Stata Journal, 3(1), 32–46.

Schechtl, M. (2023). The taxation of families: How gendered (de) familialization tax policies modify horizontal income inequality. Journal of Social Policy, 52(1), 63–84.

Steinbach, A., Kuhnt, A.-K., & Knüll, M. (2016). The prevalence of single-parent families and stepfamilies in Europe: Can the Hajnal line help us to describe regional patterns? The History of the Family, 21(4), 578–595.

Taylor, Z. E., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Promoting strengths and resilience in single-mother families. Child Development, 88(2), 350–358.

Treanor, M. C. (2018). Income poverty, material deprivation and lone parenthood. The triple bind of single-parent families, pp. 81–100.

Verbunt, P., & Guio, A. C. (2019). Explaining differences within and between countries in the risk of income poverty and severe material deprivation: Comparing single and multilevel analyses. Social Indicators Research, 144(2), 827–868.

Verma, V., & Betti, G. (2006). EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC): Choosing the survey structure and sample design. Statistics in Transition, 7(5), 935–970.

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2003). Persistent income poverty and deprivation in the European Union: An analysis of the first three waves of the European Community Household Panel. Journal of Social Policy, 32, 1.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2012). Understanding material deprivation: A comparative European analysis. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(4), 489–503. SI: Consequences of Economic Inequality.

Wimer, C., Fox, L., Garfinkel, I., Kaushal, N., Nam, J., & Waldfogel, J. (2021). Trends in the economic wellbeing of unmarried-parent families with children: New estimates using an improved measure of poverty. Population Research and Policy Review, 40, 1253–1276.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2005). Simple solutions to the initial conditions problem in dynamic, nonlinear panel data models with unobserved heterogeneity. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20(1), 39–54.

Zagel, H., & Van Lancker, W. (2022). Family policies’ long-term effects on poverty: A comparative analysis of single and partnered mothers. Journal of European Social Policy, 32(2), 166–181.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Calegari, E., Fabrizi, E. & Mussida, C. State Dependence in Material and Social Deprivation in European Single-Parent Households. Soc Indic Res 172, 481–498 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03317-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03317-8