Abstract

This article aspires to foster the debate around the methods for measuring time and income poverty. In the last fifteen years a few studies (Dorn et al. in RIW, 2023; Harvey and Mukhopadhyay in SIR 82, 57–77, 2007; Bardasi and Wodon in FE 16, 45–78, 2010; Zacharias in LEIBCWP. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383, 2011; Merz and Rathjen in RIW 60, 450–479, 2014) attempted to measure multidimensional deprivation including time poverty in the definition. Some of them (Bardasi & Wodon in FE 16, 45–78, 2010; Harvey & Mukhopadhyay in SIR 82, 57–77, 2007; Zacharias in LEIBCWP. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383, 2011) put unpaid work–and, therefore, gender inequalities in the division of work–at the center. Despite the fact that the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty (LIMTIP) was first presented more than a decade ago (Zacharias in LEIBCWP. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383, 2011), the measure was always employed in reports and never empirically discussed in an academic article. Here I want to fill this gap in the debate by comparing the LIMTIP to the other measures and by applying it to a new case–Italy–furthering the exploration around the linkages between gendered time allocation, employment patterns and household wellbeing in a country characterized by an extraordinary low women’s participation in the labor market and an equally extraordinary wide gender gap in unpaid care and domestic work.

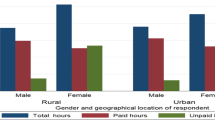

Source: author’s calculations based on matched data set

Source: author’s calculations based on matched data sets

Similar content being viewed by others

Date Availability

Time and income poverty measurement. An ongoing debate on the inclusion of time in poverty assessment.

Notes

See, for example, the theory on the investment in human capital developed by Mincer (1958).

Free time has been defined also as ‘discretionary time’ (Goodin et al., 2008), and it can become the measure for the temporal autonomy that one can enjoy.

For example, in the EU (Addati et al., 2018) on average women spend almost double the amount of time in unpaid work than men. In fact, women spend on average 4 h and 26 min per day in unpaid work, while men spend only 2 h and 23 min, representing an average gender gap in unpaid work of more than 2 h. Italy presents one of the most unequal divisions of unpaid work between women and men. In Italy women spend on average 5 h and 5 min per day in unpaid work, while men spend only 1 h and 48 min, representing—after Portugal – the highest gender gap in the share of total unpaid work (23.8%) among the EU countries.

Feminist scholars challenged the mainstream economics paradigm that paid employment is the exclusive mode of securing a living for oneself and one’s family. Feminist theory considers the importance of non-market activities —from care work to subsistence production— that form the prerequisites for labor market activities, putting the emphasis on reproduction. In particular, they highlighted the role of unpaid work in the extension of monetary income in the form of expanded living standards (i.e. cooked food, washed clothes), and in the expansion of extended living standards in the form of an effective welfare conditions (i.e. ensuring that children go to school, assuring well-being to specific people) (Picchio, 2003). In other words, you cannot feed banknotes to babies, but through unpaid work you need to transform income into goods and services for family members.

Non-substitutable household production does not refer to any activity in particular, but more generally to that minimum share of household activities that, in any case, will not be externalized. Vickery (1977) assumes that even where the maximum substitution of money for nonmarket time has been made, there is a minimum amount of time necessary for the overall management of the household and the supervision of those hired to perform the necessary tasks.

The process through which the thresholds for this study have been built will be explained in Sect. 4.

In the empirical application of the LIMTIP it is impossible to apply the individual share of non-substitutable household production (α), because it is not possible to distinguish in the data the part of household production that is substitutable from the part that is not. Therefore, a minimum threshold of non-substitutable household production that is the same for every adult person in the household is defined.

How the minimum necessary time is calculated is presented in Sect. 4.

For a description of the specific activities that are included for making the estimates see the case study in Sect. 4.

The household time deficit equation in the LIMTIP sets the value of time deficit equal to zero for time non-poor households, thereby ignoring the disparities that would exist among such households in the free time available to them. However, Zacharias (2011) highlights that such disparities do not play any role in the definition of the threshold for income poverty, and they also do not matter in drawing the line between time-poor and time-non-poor households.

Employment rates by sex, age and citizenship, Eurostat [lfsa_ergan].

Here the data of the last available wave Italian Time-use Survey (IT-TUS 2013–2014) are analyzed. The IT-TUS is described in Appendix 2.

Unpaid work does not include voluntary work, which is out of the scope of this study.

Excluding voluntary work.

EU-SILC is described in Appendix 2.

For IT-SILC years 2009 and 2015 were selected, because the survey uses the previous calendar year as the income reference period.

The three categories are: (1) care, that relates to all caring activities for other members of the household, such as eldercare and childcare, but also, for example, the time spent taking children to school; (2) procurement, which represents all those activities that involve buying or obtaining all necessary goods and services, like food shopping or going to the post office to pay the bills; (3) core, which includes domestic work such as cleaning, laundering, cooking, etc. All these three categories are grouped under the set of household production.

The hours of required personal maintenance were estimated as the sum of minimum necessary leisure time (assumed to be equal to 14 h per week) and the weekly average of the time spent on essential activities of personal care. It should be noted that 14 h per week was approximately 20 h less than the mean value of the time spent on leisure (sum of time spent on social, cultural activities, entertainment, sports, hobbies, games and mass media). LIMTIP methodology sets the threshold at a substantially lower level than the observed value for the average person in order to ensure that it does not end up “overestimating” time deficits due to “high” thresholds for minimum leisure.

The method assumes that the hours of non-substitutable household activities are equal to 7 h per week. It is not possible to determine from the data how much of the household production is non-substitutable (see footnote 5). For this reason, and in order to be able to compare the results from this study with the results obtained in previous studies, the study adopts the 7 h threshold used in previous LIMTIP analyses, which means one hour per day for each adult person in the household.

After the threshold hours of household production were estimated, the study determined the share of hours of household production of each individual in the household. This was done using the matched data. The method assumes that the share of an individual in the threshold hours would be equal to the share of that individual in the observed total hours of household production in their household. Consider the hypothetical example of a household with only two adult persons, a woman and a man. If the synthetic data show that the two persons spent an equal amount of time in household production, the threshold value of 50 h of household production recorded for households with two adults and no children, was equally divided between them.

The required time for commuting to work has been derived from the time-use survey. The exploratory analysis showed that the hours of employment have an important impact on the hours of commuting – individuals with a higher weekly number of employment hours have on average a higher number of hours of commute. Therefore, it did not seem appropriate to use the average time for employees without taking into account the hours of employment. After analyzing how commuting time varies in relation to the hours of work, an average commuting time (equal to 3 h) for persons working less than 30 h per week and an average commuting time (equal to 4 h) for persons working 30 or more hours has been determined.

For Italy, the study uses as a reference point the “at risk of poverty” measure as defined by Eurostat. Eurostat considers at risk of poverty everyone living in a household that stands below the 60 percent of the median equivalized disposable income. In the EU case, household equivalised disposable income is calculated as follow:

Equivalised household size = 1 + (0.5* number of persons 14 years old and over) + (0.3*number of persons below 14 years old).

Equivalised disposable income = total household disposable income / equivalised household size.

The minimum wage for domestic workers is established by the “Contratto Collettivo Nazionale di Lavoro sulla Disciplina del Rapporto di Lavoro Domestico” (available at the following link: https://www.assindatcolf.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CCNL-15X21-Assindatcolf-2018.pdf). In this estimation the minimum hourly wage for non-cohabiting domestic workers at A level (the lowest), that is equal to 4.57 euros, is used. With contribution and taxation, the total cost of one hour of domestic work is approximately 6 euros. The study uses the minimum wage for an unqualified domestic worker and not specialized wages, as for example in Suh and Folbre (2016), in order to avoid overestimation of poverty.

The increase in time poverty among men could be due to different elements (an increase in the amount of hours of paid work, an increase in men’s share of household production, that could be due to a change in households composition, for example). To disentangle the causes that are at the origin of this phenomenon a specific analysis is needed, but, at this stage, it goes beyond the scope of this work.

For Korea, the study focused exclusively on employed persons.

It is important to notice that in Italy the percentage of men employed part-time is particularly low compared to women (in 2014 the percentage of men employed part-time on total employed men was equal to 7.8, while for women it was 32.8). Part-time employment, annual data, Eurostat [lfsi_pt_a].

The reason of behind this result requires further investigation.

The cost of children increases when we consider the value of time. In their study on equivalence scale estimation adding the time value of different domestic activities to the monetary expenditures, Gardes and Starzec (2018) highlighted that expenditures for children decrease more the level of well-being in full prices terms than in monetary terms, because they cannot be substituted for cheaper expenditures.

The net income corresponds to the gross income component but the tax at source, the social insurance contributions, or both, are deducted, as found in EU-SILC. Here net wages are employed because the represent the part of the salary that the worker can use for covering the cost relative to time deficits.

I refer to head of the household as to the person who responded to the survey, and to the spouse as her/his partner.

References

Addati, L., et al. (2018). Work. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(2), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-011-9181-4

Antonopoulos, R., et al. (2017). Time and income poverty in the city of buenos aires. In R. Connelly & E. Kongar (Eds.), Gender and time use in a global context the economics of employment and unpaid labor (pp. 161–192). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Atkinson, A. B. (2003). Multidimensional deprivation: contrasting social welfare and counting approaches. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 51–65.

Bardasi, E., & Wodon, Q. (2010). Working long hours and having no choice: time poverty in guinea. Feminist Economics, 16(3), 45–78.

Beneria, L. (1999). The enduring debate over unpaid labour. International Labour Review, 138(3), 287–309.

Beneria, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. S. (2016). Gender, development, and globalization. Economics as if all people mattered (2nd ed.). Rouledge.

Boserup, E. (1970). Women’s role in economic development. St. Martin’s Press.

Dorn, F., et al. (2023). ‘A bivariate relative poverty line for leisure time and income poverty: Detecting intersectional differences using distributional copulas. Review of Income and Wealth [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12635

Eurostat (2016). Methodological Guidelines and Description of Eu-Silc Target Variables.

Gardes, F., & Starzec, C. (2018). A restatement of equivalence scales using time and monetary expenditures combined with individual prices. Review of Income and Wealth, 64(4), 961–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12302

Goodin, R. E., J., et al. (2008). Discretionary Time: A New Measure of Freedom. Cambridge University Press.

Harvey, A. S., & Mukhopadhyay, A. K. (2007). When twenty-four hours is not enough: Time poverty of working parents. Social Indicators Research, 82(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9002-5

ISTAT (2017). Uso del tempo. Periodo di riferimento: anno 2013–2014. Aspetti metodologici dell’indagine.

Kum, H., & Masterson, T. (2010). Statistical matching using propensity scores : Theory and application to the analysis of the distribution of income and wealth. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 35, 177–196. https://doi.org/10.3233/JEM-2010-0332

Masterson, T. (2014). Quality of statistical match and employment simulations used in the estimation of the levy institute measure of time and income poverty (LIMTIP) for South Korea, 2009. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2416850

Merz, J., & Rathjen, T. (2014). Time and income poverty: An interdependent multidimensional poverty approach with German time use diary data. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(3), 450–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12117

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. Journal of Political Economy, 66(4), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/521238

Picchio A (2003) Unpaid Work and the Economy. In: A Picchio (Eds.) New York: Routledge. pp 10–24

Razavi, S. (2007) The Political and Social Economy of Care in a Development Context, Gender and Development Programme.

Rubin, D. B., & Thomas, N. (1996). Matching using estimated propensity scores: relating theory to practice. Biometrics, 52, 249–264.

Suh, J., & Folbre, N. (2016). Valuing unpaid child care in the U.S.: A prototype satellite account using the american time use survey. Review of Income and Wealth, 62(4), 668–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12193

Vickery, C. (1977) ‘The Time-Poor: A New Look at Poverty’, The Journal of Human Resources, 12(1), pp. 27–48. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/145597.

Williams, J. R., Masuda, Y. J., & Tallis, H. (2016). A Measure Whose Time has Come: Formalizing Time Poverty. Social Indicators Research, 128, 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1029-z

Zacharias, A. (2011). The measurement of time and income poverty. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1939383

Zacharias, A., Antonopoulos, R. and Masterson, T. (2012) Why Time Deficits Matter: Implications for the Measurement of Poverty. Levy Economics Institute.

Zacharias, A., Masterson, T. and Kim, K. (2014) The Measurement of Time and Income Poverty in Korea. Levy Economics Institute.

Acknowledgements

In this study the matching algorithm developed at the Levy Economics Institute has been applied.

Funding

This work was funded by the European PhD in Socio-Economic and Statistical Studies (Sapienza University of Rome).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author does not have any conflicts of interests and or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The stages of the construction of the synthetic datasets Created for estimating the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty (LIMTIP) for Italy in 2008 and 2014 are presented. I use the Italian Indagine Multiscopo sull’Uso del Tempo of 2008–2009 and 2013–2014 (IT-TUS) for time use data and the Italian data of the European Survey of Income and Living Conditions of 2009 and 2015 (IT-SILC) for the information on demographics and income.

1.1 Data and Alignment

Both IT-TUS and IT-SILC are representative at the national level and contain information for individuals for all age classes. IT-TUS 2008–09 has 44,605 observations, representing 59,426,798 individuals when weighted, while IT-SILC 2009 has 51,196 observations, representing 60,108,862 individuals when weighted. IT-TUS 2013–14 has 44,866 observations, representing 60,410,793 individuals when weighted, while IT-SILC 2015 has 42,987 observations, representing 60,843,061 individuals when weighted.

In order to match the most similar observations, I had to select several variables. Following the example of Masterson (2014), I identified a number of strata variables that are relevant for determining the average amount of household production that is required to subsist at the poverty level of income. For this reason, the reference group for household production threshold estimation consists of households with at least one non-employed adult to avoid underestimation of the necessary amount of household production. Strata variables include, at household level, the number of children and of adults, the presence of a non-employed adult, the income category and, at individual level, the sex, and the employment status. Additionally, other variables might be relevant, as, for example, age, citizenship, region of residence, level of education, etc. These additional variables are selected on the basis of their comparability in the two data files.

Therefore, first of all, I extensively worked on the two separate files in order to align the common variables in terms of definition and measurement. For example, in IT-TUS the only income information present is the main source of income at individual level. Therefore, based on the categories provided by the variable in the IT-TUS, I constructed a corresponding variable in the IT-SILC where, instead, I found detailed information about different sources of income, both at household and individual level. I proceeded according to this principle until I harmonized all the definitions of strata and relevant variables.

Then, to maximize the matching quality, I checked that the distributions of the common variables were comparable. I expected comparable distributions because both data sets have a large number of observations and they are both nationally representative. When common variables did not align, then I doublechecked the definitions and harmonized them, where possible. I found an excellent comparability for all the selected variables (see Tables 8 and 9 below). After the harmonization, I adjusted the sum of the attached weights for records, in order to make them comparable.

1.2 Matching

At this point I need to transfer the variables related to time use from the IT-TUS to the IT-SILC. Considering which are the factors that mostly affect the variation of the amount of unpaid care and domestic work, I divided the reference group into 12 subgroups based on the number of children (0, 1, 2 and 3 or more) and the number of adults (1, 2 and 3 or more).

According to the selected strata variables (the number of children in the household, the number of adults in the household, the presence of a non-employed adult in the household, the marital status, the presence of children under 3 years of age in the household, the sex, the main source of income, the activity status and the number of earners in the household), I separated the data within each file in 38,400 discrete cells.

Then I carefully selected the common variables in the logistic regression model for propensity scores in order to maximize the explanatory power. In the end, my selection of relevant variables included, besides the strata variables: age, level of education, being in education, having a second job, citizenship, region, household tenure, head of the household, spouse.Footnote 30

After running the model, all records for each file were sorted by estimated propensity score and attached weight. For every recipient in the recipient file (IT-SILC), an observation in the donor file (IT-TUS) was matched with the same or nearest neighbour, based on the rank of their propensity scores. In this match, a penalty weight is assigned to the propensity score according to the size and ranking of the coefficients of strata variables not used in a particular matching round (see Tables 10 and 11 below). Under this sorting scheme, I assigned records with larger weights in the donor file to multiple records in the recipient file until all of their weight has been used up.

1.3 Test of Quality of Matching

In order to check the quality of the matching I compared the marginal and the joint distributions in the matched file and in the donor file (see Tables from 12, 13, 14, 15 below). The constraints of the matching scheme should lead to identical marginal distributions, and the joint distribution of variables not jointly observed should be nearly the same.

Therefore, I checked that the mean and the median values for the transferred variables by each strata variable were similar in the matched and the donor files. Specifically, I checked if there were discrepancies in time devoted to unpaid care and domestic work by type of household and sex of the individual. The ratio of the average time spent by women and men for different household activities in the matched file, to the average value in the donor file and the distribution of weekly hours of unpaid care and domestic work for each of the 12 cells, differentiated by number of adults in the household and number of children in the household (see figures from 3, 4, 5, 6 below), give confidence that the marginal distributions have been well preserved in the statistical matching process. Divergences are related in particular to the limited number of observations with three or more children.

Appendix 2

2.1 IT-TUS

The Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) regularly collects data on time use from 2002. The IT-TUS (ISTAT, 2017) is carried out every five years and it is composed of three questionnaires: the individual questionnaire contains general information on family members and their household, the daily diary records the daily use of time of all members aged three years or more, and the weekly diary records, and the hours of paid work for all members that hold a job. Individuals are required to fill in the daily diary for week-days, Saturdays, and Sundays randomly. Sample weights are used to obtain statistics representative of the whole Italian population. Activities are classified in 10 groups: physiological needs, professional work, education activity, household activities, voluntary work in organizations and beyond, social life and entertainment, sport and recreation activities, personal hobbies, using mass-media, time spent on moving and transportation. This classification enables a detailed analysis of the time each household member spends on each activity. The Italian time use survey does not include information on income and earnings.

The population of interest in the Italian Time Use survey is composed of households residing in Italy and the individuals who make them up; people residing in cohabitation institutions are excluded. The family is understood as a de facto family, i.e. a set of cohabiting people linked by marriage, kinship, affinity, adoption, guardianship or emotional ties.

The study domains, i.e. the areas with respect to which the population parameters being estimated are referred, are of two different types: territorial-type domains and temporal-type domains.

The territorial domains are as follows:

-

the entire national territory;

-

the five geographical divisions (North-Western Italy, North-Eastern Italy, Central Italy, Southern Italy, Insular Italy);

-

the geographical regions (with the exception of Trentino Alto Adige whose estimates are produced separately for the provinces of Bolzano and Trento);

-

the municipal typology obtained by dividing Italian municipalities into six classes based on socio-economic and demographic characteristics:

-

A)

municipalities belonging to the metropolitan area divided into:

-

A1 central municipalities of the metropolitan area: Turin, Milan, Venice, Genoa, Bologna, Florence, Rome, Naples, Bari, Palermo, Catania, Cagliari;

-

A2 municipalities that gravitate around the central municipalities of the metropolitan are

-

-

B)

Municipalities not belonging to the metropolitan area divided into:

-

B1 Municipalities with up to 2,000 inhabitants.

-

B2 Municipalities with 2,001–10,000 inhabitants.

-

B3 Municipalities with 10,001–50,000 inhabitants.

-

B4 Municipalities with over 50,000 inhabitants.

-

As far as temporal domains are concerned, the estimates produced by the survey are published with reference to four types of day: weekday, day before a holiday (Saturday), public holiday (Sunday) and average weekly day.

The sampling design is complex and makes use of two different sampling schemes, both based on a cluster structure of the population in municipalities and families. Within each of the domains defined by the intersection of the geographical region with the six areas A1, A2, B1, B2, B3 and B4, the Italian municipalities are divided into two subsets on the basis of the resident population:

-

1-

the set of self-representative municipalities (which we will indicate from now on as AR municipalities) made up of the municipalities with the largest demographic size;

-

2-

the set of non-self-representative municipalities (or NAR) made up of the remaining municipalities.

Within the set of AR municipalities, each municipality is considered as a separate stratum and a design known as cluster sampling is adopted. The primary sampling units are represented by registry families, systematically extracted from the registry office of the municipality itself; for each family included in the sample, the characteristics under investigation of all the de facto members belonging to the same family are recorded.

Within the NAR municipalities, a two-stage design is adopted with stratification of the first-stage units. The first stage units (UPS) are the municipalities, the second stage units are the households (USS); for each family included in the sample, the characteristics under investigation of all the de facto members belonging to the same family are recorded.

Municipalities are selected with probabilities proportional to their demographic size and without repetition, while households are extracted with equal probabilities and without repetition.

For the definition of the overall sample size and its allocation among the different territorial domains, it was decided to adopt a mixed perspective based both on cost and organizational criteria, and on an assessment of the expected sampling errors of the main estimates with reference to each of the territorial domains of interest.

The theoretical sample size at the national level was essentially set at based on cost and operating criteria and is equal to approximately 21,000 families and 500 municipalities. The allocation of the sample of families and municipalities among the various regions was then defined adopting a compromise criterion such as to guarantee the reliability of the estimates both at the national level and at the level of each of the territorial domains.

EU-SILC

EU-SILC (Eurostat, 2016) is a multi-dimensional dataset focused on income but at the same time covering housing, labour, health, demography, education and deprivation, to enable the multidimensional approach of social exclusion to be studied. It consists of primary (annual) and secondary (ad hoc modules) target variables, all of which are forwarded to Eurostat. The primary target variables relate to either household or individual (for persons aged 16 and more) information is grouped into areas: at the household level basic/core data, income, housing, social exclusion and labour information; at the personal level basic/demographic data, income, education, labour information and health. The secondary target variables are introduced every four years or less frequently only in the cross-sectional component. Data are based on a nationally representative probability sample of the population residing in private households within the country, irrespective of language, nationality or legal residence status. All private households and all persons aged 16 and over within the household are eligible for the operation. According to the Commission Regulation on sampling and tracing rules, the selection of the sample is drawn according to the following requirements:

For all components of EU-SILC (whether survey or register based), the cross-sectional and longitudinal (initial sample) data shall be based on a nationally representative probability sample of the population residing in private households within the country, irrespective of language, nationality or legal residence status. All private households and all persons aged 16 and over within the household are eligible for the operation.

Representative probability samples shall be achieved both for households, which form the basic units of sampling, data collection and data analysis, and for individual persons in the target population.

The sampling frame and methods of sample selection shall ensure that every individual and household in the target population is assigned a known and non-zero probability of selection.

Depending on the country, micro-data could come from:

One or more existing national sources whether combined or not with a new survey;

A new harmonized survey to meet all EU-SILC requirements.

The only constraint is that for both the cross-sectional and longitudinal components, all household and personal data will be linkable.

In terms of the units involved, four types of data are involved in EU-SILC:

-

(i)

Variables measured at the household level;

-

(ii)

Information on household size and composition and basic characteristics of household members;

-

(iii)

Income and other more complex variables termed ‘basic variables’ (education, basic labour information and second job) measured at the personal level, but normally aggregated to construct household-level variables; and

-

(iv)

Variables collected and analysed at the person-level ‘the detailed variables’(health, access to health care, detailed labour information, activity history and calendar of activities’).

For set (i)-(ii) variables, a sample of households including all household members is required. Among these, sets (i) and (ii) will normally be collected from a single, appropriately designated respondent in each sample household–using a household questionnaire for set (i) and a household member roster for set (ii). Alternatively, some or all of these may be compiled from registers or other administrative sources.

Set (iii) concerns mainly, but not exclusively, the detailed collection of household and personal income–this must be collected directly at the person level, covering all persons in each sample household. In most countries, i.e. in the so-called ‘survey countries’, these income variables will be collected through personal interviews with all adults aged 16 + in each sample household. This collection will be normally combined with that for set (iv) detailed variables, since the latter also must also be collected directly at the person level. By contrast, in ‘register countries’, set (iii) variables will be compiled from registers and other administrative sources, thus avoiding the need to interview all members (adults aged 16 +) in each sample household.

Set (iv) variables will normally be collected through direct personal interview in all countries. These are too complex or personal in nature to be collected by proxy; nor are they available from registers or other administrative sources. For the ‘survey countries’, this collection will normally be combined with that for set (iii) variables as noted above–consequently both normally based on a sample of complete households, i.e. covering all persons aged 16 + in each sample household.

However, from the substantive requirements of EU-SILC, it is not essential that–in contrast to set (iii) variables–set (iv) variables be collected for all persons in each sample household. It is possible to do this collection on a representative sample of persons (adult members aged 16 +), such as by selecting one such person per sample household.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Aloè, E. Time and Income Poverty Measurement. An Ongoing Debate on the Inclusion of Time in Poverty Assessment. Soc Indic Res 169, 283–322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03144-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03144-3