Abstract

Skills wastage among contract court clerks in China is becoming a concern for the court system, as it raises the turnover of essential personnel. This article explores how and why highly educated recruits (‘talents’) are attracted to, and often leave, this job through interviews with 79 newly recruited clerks of two courts of a provincial capital. The interviews reveal that underemployment—a common cause of dissatisfaction—reflects rigid recruitment policies, an inefficient talent allocation mechanism, and fundamental institutional changes to career progression in this specific occupation. To alleviate the problem, the data collected suggest encouraging employers to adjust their recruitment policies and provide more employment and career guidance. As many of the new recruits leave provincial towns to seek fortune in the capital, and this raises the incidence of under-employment among newly appointed court clerks through fiercer job competition, skills wastage among court clerks could also be reduced by narrowing the gap among cities to make talents evenly distributed across space.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

According to the theory of human capital, human resources are crucial to a country’s development and most countries pay much attention to talents’ cultivation (Schultz, 1971).Footnote 1 However, along with the rapid development of higher education and an increasing supply of graduates (‘talents’), as China has experienced over the past three decades, a new phenomenon has emerged: namely, that well-educated and highly-skilled talents are employed in jobs in which their skills and knowledge cannot be fully utilized. This is known as “skills wastage”, “underutilization of skills”, “talents waste” or “brain waste” (Krahn et al, 2000; Liversage, 2009; Yoshida & Smith, 2005).

Skills wastage has long been researched in high-income countries where it is now relatively well understood.Footnote 2 It is noteworthy that this phenomenon is especially important for those with above average qualifications and skills, who are the most productive part of the labour force. The objective of increasing the level of education and skills in the population in an equitable and cost-effective way as a major policy to facilitate economic growth appears now inadequate and may entail the acceptance of some waste in the form of education-occupation mismatches.Footnote 3 Thus, for policymakers, the emphasis now is not only promoting the popularization of higher education, but also paying more attention to the matching process in the labour market.

In the case of court clerks in China, skills wastage has occurred since the reform of their personnel management system. Court expanded its recruitment of court clerks and open the job to non-local graduates, hence the proportion of migrants in court clerks largely increased. Court clerk is an attractive job and the competition for it is fierce, partly fuelled by internal migration. For instance, in Jiangsu Province, the statistics released by an exam training institution show that out of 5,400 people applying for a court clerk job only 795 could be recruited, a 1:7 ratio.Footnote 4 Along with being a highly desirable job, court clerks experience a high turnover rate and clerks with bachelor or postgraduate degrees have a higher probability to resign from the job (Luo, 2017). Some of the hypotheses advanced to explain the observed turnover include a relatively low income, and poor prospect for career advancement (Luo, 2017; Pan, 2018). Clerks are an indispensible part in people’s courts, as they account for nearly 1/4 of court staff. More importantly, the work of clerks is the premise and basis for trial work. The high turnover rate of clerks has therefore a negative effect on the stability of court system and the efficiency of trial work (Marc, 1977). However, existing studies on court clerks tend to emphasise the deficiencies of the management system but do not apply a holistic approach, where the issue of skills wastage has more prominence. This paper aims at contributing to such analysis and discussion. In particular, we explore the skills wastage in China’s court system from both micro and macro viewpoints using interviews collected from a group of contract court clerks in two courts of a Chinese provincial capital. The interviews were conducted with newly recruited and former court clerks who resigned, as well as with other staffs of the two courts. The article presents the findings and its broader implications before concluding with a set of recommendations.

2 Background

2.1 China’s Push for Skills Creation

The Chinese government realized the importance of talents for economic development and increased the education devotion after the reform and opening-up since the early 1980s, but especially in the 1990s. In 2002, the strategy of ‘Strengthening China through Human Resource Development’ had been established as one of the basic state policies. After its implementation, the higher education system took off. The number of colleges and universities and students enrolled by colleges and universities increased greatly, with the total number of students reaching 443 million—the largest in the world. The enrollment rate of higher education increased from 30% in 2012 to 57.8% in 2021, an increase of 27.8 percentage points.Footnote 5 Compared with 2010, the number of universities educated people per 100,000 increased from 8930 to 15,467.Footnote 6 The population with a bachelor’s degree is nowadays 218.36 million. However, even though the growth rate of highly-educated talents has been high relative to the grow rate of China’s GDP, there is still a shortage of talents in many regions and industries. Highly-educated talents are unevenly distributed in China. The proportion of people with college degree or above in the total population in Beijing, Nanjing and Shanghai are 41.98%, 35.23% and 33.87%, respectively. This is far above the national average (15.47%). The corresponding proportions in Guizhou, Guangxi and Qinghai are 10.95%, 10.81% and 1.49%. As a result, the employment competition in developed cities has prograssibely become fiercer, while employers in smaller centres cannot recruit graduates—widening the gap between large and small cities.

The uneven distribution of talents also appears in different industries. Nearly half of the top 30 occupations in the ranking list of 100 occupations most short of talents published by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security are related to manufacturing, information transmission, software and information technology services and other industries, requiring a higher degree of specialization. However, talents majoring in Law, Accounting and Journalism and Communication are oversupplied.

Higher educated talents have higher productivity, but the premise is that they are allocated to matching jobs (Shengde Lai, 1998). So the efficient functioning of the allocation mechanism is critical. In the planned economy era, the government exercised overall control over the use of labour resources. In particular, in the state-owned sector, the employment arrangement of employees is completely dependent on the administrative allocation mechanism. The number and scale of employment of enterprises were determined by the relevant government department. Labour could not freely flow among regions and employers. In nowadays’ market economy, the allocation mechanism maching labour demand and supply responds to the relative underlying forces. Labour can freely flow across regions and enterprises, but this has brought with it the uneven distribution of jobs and a labour market segmentation. While the vast majority of people with lower education or primary education are basically trapped in the secondary labor market, unable to transfer to the primary market, college graduates have more choices. However they tend to prefer staying in central or large cities even if this means having occupations that require less education than what they acquired. This in turn means that graduates compete in the labor market of people with lower education level, contributing to hidden unemployment.

2.2 Skills Wastage in China

China’s recent experience of educational mismatches in the labour market following the expansion of its higher education system has not been unnoticed (Wu and Li, 2021a, 2021b). Skills wastage has negative influences to both individuals and the country, as it leads to lower income and poor returns on education investments (Dollard & Winefield, 2002), as well as wastage of education resources and a loss of potential economic benefits that talents should have created (Wagner & Childs, 2006). Notwithstanding these premises, skills wastage in China differs in some aspects with that experienced in high-income countries. In more developed economies, overeducation often affects skilled immigrants, while in the case of China’s labour market overeducation is a domestic problem.

Although China has high levels of internal migration, there is no evidence that non-locals are discriminated against in the process of employment, unlike immigrants in high income countries (Benjamin, 1994). However, it is undeniable that highly-educated people in China are more likely to migrate to larger cities to find high paying or more suitable jobsFootnote 7 (Sunita, 2005) and their high proportion in larger cities makes them appear as if they are more likely to end up wasting their skills.Footnote 8 It has been observed that there is a large number of talents migrating to developed cities for better job opportunities, salaries, welfare, and living conditions to name a few. The aggregation of talents in larger cities generates fiercer competition in the local job market and many talents are then unable to find jobs matching their skills and education. For example, according to the Advanced Research Institute of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, the matching rate between the education level of employees and their jobs is 39.70%, and the incidence rate of overeducation is 24.40%.Footnote 9 Under such circumstances, the inevitable conclusion is that some of them have to accept jobs with lower requirements and income, and lower rates of return on their education (He, 2009).

The literature has not been silent on these outcomes. The first Chinese study on skills wastage dates back to 2006, when scholars studied the phenomenon from different perspectives. Yingming An (2006) holds that such wastage is the result of a poor allocation mechanisms that leads to talent waste. Massive numbers of newly formed graduates migrating to wealthier “upper tier”cities have become a salient feature of China’s recent rapid economic development. This movement is prominent among highly educated talents, and generates their uneven distribution among geographic areas. This in turn results in the paradox that the supply of talents in the most developed areas is excessive while in lesser urban centres is still insufficient. The resulting “overeducation” in the most populous urban centres is therefore viewed as a consequence of China’s higher education growing faster than the rest of the economy. However, despite its rise, many authors believe that overeducation is only a temporary phenomenon, because the proportion of college graduates in the total labor force is still low, and the expansion of higher education remains beneficial to China's economic development in the long run (Lu & Li, 2005; Zhou, 2008).

In contrast, some authors view skills wastage as a kind of “recessive unemployment” caused by the labour market segmentation (Gong, 2010; Lai, 2001; Ma & Yue, 2011). This view holds that China's labor market is divided into primary and secondary labor markets across regions, sectors and occupations. Due to the high rigidity of wages and benefits of the primary labor market, college students compete and wait for suitable jobs in these industries, causing their temporary skills underuse. According to Yu and Chen (2006) this occurs as education fails to provide the signal function that enables employers to distinguish different levels of college quality and hence graduates’ potential productivity. This view is shared by other researchers who point out that China’s higher education system does not sufficiently take into account the needs of current professional employers, resulting in large numbers of graduates being unable to find jobs matching their majors and education degrees because of their inadequate training.

2.3 The Labour Market of Contract Court Clerks

Clerks are recuited through an open call since 2003. Before that, there was no public recruitment for clerks, as they were law graduates and assigned by their colleges. With China’s eocnomic growth, the increase of cases also expanded, and with it the demand for clerks. This pushed courts to reform the method of recruitment applied. Under the new recruitment policy, courts could set different recruitment requirements according to their actual and expected needs. At the beginning of the reform, many courts failed to recruit enough clerks due to setting requirements that were only met by law graduates. The courts relaxed this policy, resulting in higher numbers of applicants. However, significant differences in recruitment policies across cities have emerged. Recruitment requirements in large urban centres are more strongent than those of relatively smaller cities. For instance, recruitment announcements issued by the people’s courts in Shanxi, Gansu and Heilongjiang Provinces, require a college degree or above but no limits to the major in which the BA was acquired. In large urban areas, such as Shanghai, Shenzhen and Beijing, clerks are generally required to have a bachelor degree or above and are required to be law graduates, even though the work of clerks across the country bears little differences. Another significant change is that the restriction on applicant’s residence has been cancled, meaning that non-local graduates can apply for the job. Consequently, migrants have been a large part of court clerks in developed cities and cause some problems, such as higher turnover.

Besides opening up admissions to a wider number of potential applicants, the management system of clerks was also reformed. From 1979 to 2003, court clerks were employed as "internal employees" and enjoyed the remuneration and promotion stipulated by the state.Footnote 10 They followed the career path of court clerk acting judge judge. After 2003, a contract-based system for court clerks was introduced, and as a result court clerks were no longer internal employees of the court. The Measures for the Administration of the Clerks of the People's Court (for Trial Implementation) (hereinafter referred to as "Measures") formulated by the Organization Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (Organization Department, CCCPC), Ministry of Personnel and Supreme People's Court established contractual management for clerks and divided court clerks into ‘internal’ and ‘contract’ ones. According to the Measures, ‘contract’ court clerks belong to ancillary personnel who need to work under the guidance of judges. The newly reformed management system blocked their possibility to be promoted to assistance judge, curbing their promotion opportunities. Additionally, contract court clerks do not enjoy civil servant benefits, unlile internal employees, and so their income is barely higher than the local minimum wage.

These reforms aimed to improve the utilization rate of human capital and the management level, but their result has been a higher turnover rate of contract court clerks. For instance in a certain Province, which we will not name, in the past three years, each court lost an average of 11 contract court clerks each year (Qi, et al., 2022). Most leaving clerks were previously recruited as contract court clerks (Luo, 2017).

3 Method and Data

3.1 Qualitative Method

A qualitative approach is used as it suits investigating the experiences, feelings, opinions and social worlds of research objects (Fossey et al., 2002) and it provide a “deeper” understanding of social phenomena (Silverman, 2020). Court clerks with different educational backgrounds were motivated by various reasons to apply for the job. Hence, we decided to apply semi-structured interviews to analyse their experiences. This method is portrayed as an indispensable tool to uncover knowledge through interaction, conversations, and subjects from different life experiences. Moreover, the shared stories and life experience about other matters are interpreted to expand the knowledge into multiple platforms which could broaden our knowledge of the job (Chen, 2000).

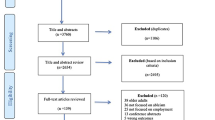

In order to have a comprehensive understanding of the relevant information about skills wastage, we recruited 87 participants who they were divided into four groups: specifically, 79 newly recruited clerks, 4 former clerks, 2 personnel department staffs and 2 judges. Different interview outlines have been prepared for different groups and adjustments to the interview protocols were made according to early experience and information provided by participants. We spent 20 to 40 mins on each interview over the course of two months. All interviews were conducted via videoconferencing. They were audio-recorded and transcribed, and only the primary researchers had access to the raw data.

The research process was engaged to protect participants’ anonymity and to avoid any impression of coercion, as per the ethics’ approval. Participants were informed about the focus of the study and how we planned to use the data. Informed consent was obtained for all interviews discussed in this paper.

3.2 Participants’ Characteristics

All participants were from two courts in a provincial capital. Namely, the Provincial Higher People’s Court (PHPC) and the Municipal Intermediate People's Court (MIPC). Due to skills wastage generally occurring in the largest cities, we purposely selected the courts in this new first-tier city, located in Yangtze River Delta and attractive to university graduates. Additionally, there is a large number of migrant talents come to City A in recent years. The two courts have implemented the personnel management system reform of court clerks and established new recruitment policies based on a contractual management system. The two courts deal with issues at different types of issue, hence revealing the extent of skills wastage.

Of the 79 newly recruited contract clerks participating in this study, 26 were recruited by the PHPC and the other 53 were recruited by the MIPC, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. They all have no prior experience in being a court clerk.

Among the 79 clerks, 44 (19 junior college graduates and 25 undergraduates) studied law-related majors including law, judicial management-related majors, and security administration-related majors. The other 35 (1 junior college graduate and 34 undergraduates) studied non-law majors including art, economics and management, and even nursing, civil engineering. The proportion of new clerks with a bachelor degree or above is 74%. There are 2 postgraduates majoring in sociology and economics, respectively. As the PHPC only recruited clerks with bachelor degree or above, the 20 non-locals are all university graduates. There are 29 clerks with bachelor degree or above among the 44 non-locals in the MIPC. Among the 26 newly recruited clerks of the PHPC, 20 were non-locals, accounting for 77.9%. At the same time, 44 of the 53 clerks hired by the MIPC were from other cities, accounting for 83%. Interviews with the clerks focused on three topics: (1) the reasons why they choose that occupation; (2) how their major and education degree affected their work as clerks; and (3) whether they felt that their education was a suitable match for the requirements of the job and if not, why.

We also recruited former clerks to gain a better understanding of their experience and feelings in the job and the exact reasons for resigning. Four former court clerks were interviewed. These were selected according to their education (must have a bachelor’s degree or above) and major (whether or not they majored in law).

Many former clerks have changed their contact information and were not easy to find. We were fortunate that the four recruited ones not only could be contacted, but were also willing to share their experiences. Those former clerks include a balanced mix of undergraduates and postgraduate degree holders (2 each, respectively). Among these four clerks, only one person’s major is not law but a postgraduate major in finance.

We also contacted personnel department staffs, who are familiar with information about court clerks and recruitment policies, to get their views on skills wastage. Two department staffs were interviewed. They are mainly responsible for recruiting and managing clerks. We also reached out to judges, as they work with court clerks and can assess clerks’ performance at work. We were particularly interested in understanding whether clerks’ education degrees and majors influence their work. We also sought judges’ views about whether they felt that clerks’ skills were wasted. We approached experienced judges who entered into the courts before 2003 as they have a deeper understanding of the changes brought about by the clerk management reform. Table 3 summarises some key detail about all the interviewees.

3.3 Data Collection and Analysis

Interviews were anonymized and each participant was given a code number. We collected data through audio-recording and chart extraction. After transcribing the interviews, we closely examined the data collected and summarised participants’ views, knowledge and experiences. We also extracted insightful sentences and opinions from the data.

The coding work started with existing research findings and was organized around two main topics: (1) situations in which clerks’ skills are wasted; (2) causes of such wastage. Then responses were coded under different themes. The themes emerged with respect to (2), which is the focus of the paper, can be categorized into 4 key areas:

-

1.

labour market: whether the labour market effectively matches supply and demand for talents;

-

2.

higher education: whether highly-educated graduates meet the quality and quantity requirements set by the labour market;

-

3.

recruitment policies: how do recruitment policies for clerks affect the quality of the recruited clerks;

-

4.

personal factors: how clerks’ personal initiative underpins their future career trajectories.

4 Results

4.1 Skills Wastage

The collected data show that migrants constitute a high proportion of court clerks and they generally have higher education degrees in the 2 courts. As we have learned from the personnel department staffs, there are about 7–8 non-locals resigning the job every year since 2018, accounting for almost 72% of the total resignations. Among the reasons why they leave the job, the most significant ones are as follows: limited promotion channel, low salaries, instability and so on. Clerks who are not satisfied with the position look for other jobs or prepare for National Judicial Examination to change the current situation. Some return to less developed cities because of the high expenditure and the pressure of life in developed cities. The rising turnover of clerks reflects that there is a skills wastage among them. Due to migrants take a large part of court clerks, skill wastage is especially obvious among migrants.

The information collected from the clerks indicates that most of the newly recruited clerks have a bachelor degree or above, and/or many of their majors are irrelevant to their duties. 37 newly recruited clerks believed that they could have been employed in jobs with higher education degree requirements and all of the 37 clerks are with bachelor’s degree or above. The 4 former clerks found better jobs after resigning: two became lawyers and the two others became civil servants. One of the former clerks said “I left the job largely for the reasons of low income and limited career development. It is proved that I can find a better job with higher income. The most important thing is that I can fully utilize my professional knowledge.” (fc1) This conclusion is shared by many current clerks who feel underemployed and therefore are not satisfied with their job. The lack of statisfaction is a major influence in seeking an alternative occupation.

According to the Measures, the duties of clerk include: (1) handling routine work in the process of pre-trial preparation; (2) inspect the appearance of litigation participants at the court and announce court discipline; (3) take charge of the record work; (4) sorting, binding and filing material; (5) complete other routine work assigned by judges. Based on the above, the work of the clerk is complex, but not particularly needy of higher education workers. According to the Migration Policy Institute, the occupation ‘court clerk’ should be classified as a middle-skilled job that does not require a bachelor's degree.Footnote 11 This requirement is at odds with the learning outcomes of law undergraduates, who are expected to be legal professionals with the ability to independently acquire and update knowledge related to laws; have basic skills to integrate professional theories and knowledge learned and apply them flexibly and comprehensively in their professional practice; employ creative thinking methods to perform scientific research and innovative and entrepreneurial practices; possess excellent skills in computer operation and foreign language.

Following the requirements of China's unified qualification exam for legal professionals, only law graduates (but not junior college graduates) can participate in the selection process. Once they have obtained the legal professional qualification certificate, they can become lawyers or sit for the recruitment exam for internal assistant judges. However, these higher-educated talents are often competing for lower requirement jobs that traditionally target vocational college graduates. Jobs with tasks that are ancillary to those of judges.

As one of the current clerks said “What I learned in college is useless in this job.” (c1) A comment shared by most of the interviewed clerks (including law and non-law graduates): “Even though my major is not law, I can get the skills that the job needs after the induction training.” (c16) Non-law clerks account for 44.3% of the two courts and none was fired at the end of the probation period, meaning that the job has little relationship with one’s major.Footnote 12

Both of the interviewed judges held the view that what really matters is not legal professional knowledge, but work experience. It is as Dewey said that we should use our past experience to develop new and better experience for the future, and rationality should be prompted and tested in experience, and applied in every way possible to expand and enrich it through invention (Dewey, 2006). The more opportunities and time the court provides for skills training, the more quickly the "labour skills" of clerks get improved. Since 2016, the "Provincial Plan" of the location of the two courts has required that all court clerks must participate in an induction training and only those who pass an assessment can formally start their work. Moreover, before being promoted to higher posts, clerks must now undergo formal promotion training. Generally, after one-month training, the new recruits can deal with all the five types of "routine work" required by the Provincial Plan and they can even assist judges or judge assistants to proofread the judgment documents.

Based on the interviews, clerks’ skills wastage mainly occurs in two situations: one is the clerk’s overeducation; the other one is that the clerk’s major being mismatched for the job. The two cases are acknowledged as common causes of skills wastage (McGuinness, 2006). Compared to the major mismatch (about 44.3% of clerks), the case of overeducation (about 74.68%) is more serious. The overeducated clerks devote more time and money on education, while the payback is the same as the one received by those with lower education. The result reflects evidence discussed in a report released by Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, whereby in for the same education level, the wages of overeducated employees are lower than those of correctly matched ones. In other words, the labour market discounts overeducation.

4.2 Underuse of Court Clerks

The interviews revealed that the four factors that affect the utilization of clerks’ skills are interrelated. From a macro-viewpoint, talents’ supply and demand and talents’ allocation mechanism are the three fundamental elements that influence the s employment outcome. Higher education policies determine the quality and quantity of talents provided by colleges and universities and thus affect talent supply. The efficiency of labour allocation mechanism determines whether these talents can be effectively allocated to matching vacancies. From a micro-viewpoint, employers as job providers have more power over employees: they can raise hiring requirements as a consequence of degree inflation, even though it may not lead to higher productive efficiency. Career choices also reflect an individual’s preferences and as such it is influenced by personal circumstances, including family obligations. These factors jointly condition if the job filled matches one’s education degree and skills.

-

• Influencing factors of skills wastage: the higher education system

For Chinese people, improving the level of education is a necessary way to increase incomes (Lai, 1998), and as to Chinese government, improving the level of national education is the key to economic development. However, with the popularization of higher education, employment difficulties of college students emerged, especially in large cities. Undergraduates are no longer a scarce resource in developed cities, let alone college students.

“It seems that having a bachelor's degree is universal throughout China and it has been a necessity for job searching. When looking for a job, my degree has no advantage.” (coded under “overeducation”, c10) 58 (including both junior college graduate and university graduates) among the 79 newly recruited clerks mentioned this problem. This could be viewed as too many university graduates crowding out the local labour market and making competition for highly desirable jobs even fiercer. Under this circumstance, many people with ordinary educational background prefer to apply for jobs with lower competitive pressure (Li, 2017).

Many interviewees also shared that “It is difficult for me to find a job matching my major.” (coded under “gap between education and the job market”, c28) The interviewees whose majors are art, education and civil engineering found that the job markets for their majors are limited, and can hardly find major-matching jobs. Nowadays, majors in philosophy, literature, history, science, agriculture, management and military science are basically in a state of “oversupply” in China’s labour market.

Another theme that emerged is the quality of graduates. A staff member of personnel department said “Junior colleges set the major of legal affairs to cultivate professional clerks for courts, but the graduates lack practical experience and need to accept vocational training as others.” (p2) Junior colleges set the law major as a requirement to specifically cultivate professional clerks for courts, but the graduates show no special predispositions in the job. The two judges mentioned it in their interviews as “Compared to higher educated talents, the working ability of junior college graduates (with vocational education) is lower” (j1,2). Mo Rong (2022) believes that this contradiction is the main problem about the recent employment conditions of university students: the higher education sector in China expanded rapidly in a short period time but the quality (viewed as the set of notions acquired by students) of education has not kept pace with it, resulting in “high education degree, low working capability” (Wu, 2016).

-

• Influencing factors of skills wastage: the labour market

Like any commodity market, the labour market is subject to hysteresis and blindness that cannot efficiently adjust the relationship between supply and demand of new graduates. As a result, talents graduating from colleges and universities do not perfectly match employers’ demand. The interviews revealed a number of underlying factors at work.

First, the degree of informatization is not sufficiently high as so economic transformation and industrial upgrading are hardly reflected in the labour market in a timely manner. This delayed signal may mislead investments in education especially for university students. “I didn’t know the employment situation before I applied for the major and it last until I began to look for a job.” (c34) Higher education lasts 3 to 4 years but demand for talents may change in the period of study, while colleges and universities programs cannot adapt for sudden changes.

Secondly, China’s proportion of the third industry kept rising and this offered opportunities for new graduates. But in recent years, this growth has slowed, while talents with tertiary-relevant majors still kept increasing following major reforms in the higher education sector. Parts of the current mismatch reflects the adjusting industrial structure.

Thirdly, the Chinese labour market’s segmentation by different occupations and regions contributes to an uneven spatial distribution of talents. A migrant said that“Most of my university classmates moved to Beijing and Shanghai which pushes me to find jobs in big cities.” (c20) Numerous talents congregate in several cities looking for jobs, but vacancies are limited and this raises job competition and the likelihood of mismatch when landing a job. Despite this, college graduates still chase jobs in China’s largest cities (Wang, 2010).

-

• Influencing factors of skills wastage: recruitment policies

According to the public recruitment information of the PHPC and the MIPC, the two courts do not impose restrictions based on graduates’ majors. Among the 63 courts in the Province under study, only 3 impose specific requirements. The absence of a restriction on majors gives graduates across different fields of study the possibility to apply for court clerk jobs, resulting in heightened competition. In 2021, the application-to-admission ratio of the PHPC and MIPC was 14:1 and 12:1, respectively. Therefore, employers can be picky, especially in the largest urban centres. “Although there is no clear requirement for academic qualifications, it actually has been taken into consideration.” (coded under “improved recruitment requirements”, p2) The Personnel department staff interviewed pointed out that the job competition has become fiercer and many talents with bachelor’s degree or even above apply for clerks’ jobs. Given the information asymmetry between employers and job seekers about the quality of candidates, it is difficult for employers to judge the productivity of job seekers in advance. For this reason, job applicants try to enhance and signal their work ability through their educational background, for instance by undertaking studies in prestigious universities.

-

• Influencing factors of skills wastage: personal factors

Personal preferences play an important role in career and locational preferences. According to “The 11th survey report on the best employers of Chinese College Students”, more than half of the college students expect to find jobs in government institutions (government, public institutions, state-owned enterprises).Footnote 13 In the ranking of college students' pursuit of different career development goals, first is a job that is respected and recognized by society, followed by pay and stability and security. “In fact, there are some other jobs that are more compatible with my major, but working in a court is more decent and stable.” (coded under “preference for stable and decent work”, c35) 59 of the interviewed clerks mentioned this aspect (74.68%). Clerks with a university degree knew that their skills would be wasted in applying for a clerk position. Yet, they still chose to work in this job implicitly accepting what could be viewed as “voluntary skills wastage”. In Chinese tradition, working in government, public institutions and state-owned enterprises is desirable as it is stable and employees do not worry about losing their job or face pay cuts. This is valuable, especially in the period of economic downturn.

“I just want to live in the city.” (coded under “motivation of living in big cities”, c15) Even though many highly-educated graduates migrate to large cities to find a better job or earn more, there are some migrants just motivated by enjoying a more varied life. Many belong to upper-middle class families. “My parents said that they hope me to find a stable job and they will give me financial support.” (c48) Living in the city is the prime consideration to these people and they do not need to worry about income. Under such circumstances, becoming a court clerk is attractive.

The uneven flow of talents into larger regions and industries and the appeal exerted by government jobs, despite its limited recognition of individual productivity, contributes to raise overeducation but also reduce the amount of human capital flowing to productive sectors, hence hindering innovation.

5 Discussion

There is a skills wastage among court clerks, but according to the interviews, the most obvious characteristic of clerks is that it is a job related to the courts, a government position, and as such it attracts many graduate applicants. “My parents want me to work in government organs, but it is too difficult to pass the civil service exam. Most of my classmates also choose to prepare for the exam in the last year in university.” (c76) Influenced by parents, a large number of graduates take government jobs as “iron bowls”, with no possibility to be fired. Although some jobs require low skills or education, as long as they are provided by government, they will be especially popular. “Even though being court clerk is no more a pathway to become a civil servant, it is a relatively stable job compared to those in private enterprises. Under such a challenging employment situation, becoming court clerk is not a bad choice.” (c61) Faced with the increasingly stern situation of employment, contract posts in government organs are popular among university graduates.

This does not mean that all jobs sought by talents will necessarily lead to skills wastage. As highlighted previously, a clerk is a middle-skilled job that most people can do properly through an induction training.

Additionally, as the probability of skills wastage in large cities is higher than that in small cities, the recruitment policies of clerks vary a lot geographically. As the work content of court clerks is essentially the same, the education degrees of clerks varies greatly between large and small centres.

Furthermore, “in recent years, the number of university graduates has increased sharply, but their personal qualities are uneven. Even though there are lots of law graduates applying for the job every year, many of them, especially junior college graduates, show no particular advantages relative others.” (p1). As a follow up, one of the judges told us “Universities and colleges pay too much attention to theories and ignore the importance of practice which leads to graduates being unadaptable to work. What is even worse is that many graduates haven’t participated in internships due to the coronavirus pandemic.” This comment highlights a disjunction between the education system and labour market demand, which an ensuing the waste of educational investments (Ma, 1995; An, 2007). The labour markets of some majors have become saturated or have no need, but colleges and universities still enroll a lot of students every year with no concern for the fact that these students will likely encounter skills wastage once they graduate.

“I find that more and more graduates of non-law majors, such as art, economy and management, apply for the job. Of course, their universities are usually not good.” (p2) Another problem is that the curriculum design of junior colleges is unsuited for today’s employers’ needs, as the interviewed judges pointed out that college graduates are often incompetent for the job they carry out.

As for the demand side, different industries have different absorptive abilities for college graduates, and this makes many college graduates of certain majors unable to find jobs that match their field of study. An under-researched but relevant aspect is that the first job after graduation generates an important signal that eases or prevents career development.“Seniors remind us that if our first job is in economically backward areas, it will be difficult to find jobs in big cities in the future. Therefore, most of us decide to move to big cities, even though the employment competition is fiercer.” (c33).

Finally, notwithstanding the various reasons underpinning skills wastage presented so far, it should be noted that faced with an increasing supply of highly-educated people in some occupations, employers find it even more difficult and costly to screen and select suitable employees. Holding a degree appears to be no longer sufficient to carry out an effective screening. As stated by an interviewee, “we clearly know that the job doesn’t need talents with high education degrees, but if the requirement set is low, there will be even more graduates applying for the job and this increases our recruiting burden. The highest efficient way to recruit clerks is through education background.” (p2) but reliance on education enhances credentialism and the acquisition of degrees and qualifications without a real need for them.Footnote 14 In other words, it incentivises further skills wastage. This is cogend for the court system, where some of the investments on recruitment and induction training is unnecessary. “The previous recruiting policy of court clerks seems to be more suitable when that courts could establish a long-term cooperation relationship with colleges and students could be cultivated with clear purpose according to the court’s needs.” (p1).

Last but not least, from an individual perspective, when highly educated talents take stability as their primary consideration in seeking employment, the vitality and innovation of the whole society may be lost. Legal study is quite popular in China and the number of law graduates is increasing in recent years. Although the underutilized clerks are not satisfied with the job, the experience of being a court clerk still means a lot to career development. Some law graduates take it as a way to occupy legal resources, accumulate working experience and a transition to other better jobs. That explains despite of the rapid flow of court clerks, there are adequate supply of talents for it. Many graduates think that it is not necessary to choose a job matching their majors (Liu & Li, 2007), and universities seem unable to guide them. “I had no idea how to find jobs after the failure of civil service exam. I even didn’t know what court clerks are before I decided to apply for it. What I learned in university is only knowledge in books.” (c45) Universities hence share some responsibilities for the status quo.

6 Conclusions

Skills wastage has been more common than thought in China. This study focuses on a group of contract court clerks to explore how and why their skills are wasted. Clerk is a middle-skilled job that does not need high skills or knowledge but even though many junior college students are specifically trained for this job, more highly-educated graduates are recruited in the job every year. The reform of court clerks management system is aimed to establish a professional and stable team, but the result is opposite to it. Under the reformed policies, courts have recruited more migrant talents which accelerates the flow of court clerks. The high turnover supports that there is a skills wastage among clerks.

Based on the information collected, the causes of such job mismatch reflect an imperfect signal between employers and universities about what needs are required to be suitably employed. Lags and lack of information result in the rise of credentialism, whereby employers in large cities raise the formal requirements for hiring while talents migrate there regardless of whether they will find a suitable job. Such blindness hinders the talents to find matching jobs. Personal preference plays a vital role in the skills wastage. Highly educated talents show a bias to developed cities and affected by traditional views, they prefer a job with high prestige and security. It is partly blamed to universities for that they do not take their due responsibilities to guide students in searching for jobs. The large scale of migration of graduates from small to larger city centres increases the employment pressure. It's hard to find satisfied work and they have to lower their job criteria which may results to the phenomenon of skills wastage. Therefore, the migration to developed cities is not a promise of a better future.

Because skills wastage is harmful both to individual and society, it deserves more attention and understanding to be addressed through policy tools. For courts, it is suggested as following: (1) Widen the promotion channel for contract court clerks and allow those who have accumulated trial experience to be directly promoted to assistant judge through internal assessment; (2) Improve the salary and welfare of contract court clerks; (3) Establish cooperation between courts and junior colleges and only graduates specifically cultivated by the colleges are qualified to work as court clerks. To be more wildly applied to, suggested approaches include (1) reforming the education system to strangthen the link between universities and professional circles; (2) promoting economic and industrial structure upgrading to create more jobs for people with higher education; (3) encouraging employers to move away from the employment orientation of hiring graduated from "only famous schools", and establish a talent utilization mechanism targeted by actual job demand; (4) providing graduates with more employment guidance to help students make a more systematic and scientific plan for their career. With the help of professional ability tests, comprehensive evaluation should be carried out in combination with students' personality, ability and academic achievements, students can better know themselves and clarify their goals, career interests and potential.

Notes

The definition of talent in The National Medium- and Long-term Talent Development Plan (2010–2020) is as follows: "talent refers to people who have certain professional knowledge or skills, perform creative work and make contributions to society, and are workers with high ability and quality in human resources. In this paper, people with bachelor’s degree and above are referred to talents.

Freeman (1976) firstly argued that too many graduates relative to the number of jobs available would lead to several underutilized graduate workers. McGuinness’ (2006) literature survey found that the proportion of mismatched employees is quite common, affecting between 11 and 50 per cent of the employed labour force.

As the Australian National Engineering Taskforce (ANET) concluded, “The causes of the acute skills shortage and the impediments to resolving the capacity crisis are largely structural, and beyond the control of individual organisations: they are rooted in the nature and patterns of demand set by governments, the complex market structure…” (Wise et al., 2011).

2021 Statistics and analysis of the number of applicants for Jiangsu Court's recruitment of clerks, the competition ratio reaches 27:1 at the most, https://js.offcn.com/html/2021/04/255132.htm

See 240 million people received higher education in China, The People’s Daily, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-05/21/content_5691565.htm, last visited on September 25th, 2022.

National Bureau of Statistics, Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census, http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817176.html, visited on September 20th, 2020.

For instance, according to the figures released by Mycos (2021), the proportion of non-local university graduates in China’s largest (‘first-tier’) cities has been about 68% for during 2016–2020, and in newly-ranked first-tier cities it has risen from 32% in 2016 to 38% in 2020 (Mycos, 2021).

According to the Ranking talent attraction in Chinese cities: 2021 released by Zhopin Ltd., 56% of floating talents have bachelor's degree or above, higher than 47% of the total job seekers, so highly educated talents are more likely to seek jobs across cities. In 2021, the proportion of fresh graduates, masters and above who put their resumes in first tier cities respectively reaches to 20.7% and 30.0%, both higher than the proportion of floating talents flowing to first tier cities. Recent graduates, masters and above will prefer to gather in first tier and second tier cities, especially those with masters and above who prefer to gather in first tier cities.

See Annual Report on China's Macroeconomic Situation Analysis and Forecast (2020–2021), Advanced Research Institute of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.

Internal employees refer to the employees subject to the staffing of public institutions "enjoy the salaries and benefits as prescribed by the state.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) assigns jobs to three skill levels: a. High-skilled jobs require at least a bachelor’s degree; b. Middle-skilled jobs require some postsecondary education or training (i.e., an associate’s degree or long-term on-the-job training or vocational training); and c. Low-skilled jobs require a high school degree or less, and little to moderate on-the-job training (Lofters, 2019).

Collins pointed out pointedly: “For most jobs, most skills, including the most advanced skills, are learned at work or through informal networks, and the education system is only trying to standardize the skills learned elsewhere.” The skills needed by clerks especially prove it. After China set up the post of assistant judge, court clerks have been mainly engaged in stylized and routine work. Due to the high reproducibility of the work, even non-law majors can perform well as a court clerk within half a year. With the exception of court transcription, which has high requirements for stenographic skills and the comprehension of legal language, the non-law majors are able to do a good job (Mo & Wang, 2018).

The 11th survey report on the best employers of Chinese College Students, http://www.docin.com/p-689668294.html

It has also been defined as "excessive reliance on credentials, especially academic degrees, in determining hiring or promotion policies." Credentialism occurs where the credentials for a job or a position are upgraded, even though there is no skill change that makes this increase necessary (Buton, 2019).

References

An Y. M. (2007). Analysis on the phenomenon of talent waste in China, People’s Forum, Z1.

Baker, B. (1994). The Performance of Immigrants in the Canadian Labour Market. Journal of Labour Economics, 12, 369–405.

Chen X.M. (2000). Qualitative Research in Social Sciences. Educational Science Press,.182–193.

Dewey. (2006). The Transformation of Philosophy, in The Collected Works of Dewey, China Social Sciences Press, Beijing, 86, 114-115.

Dollard, M. F., & Winefield, A. H. (2002). Mental health: Overemployment, underemployment, unemployment and healthy jobs. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 1(3), 1–26.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 717–732.

Gong, X. Y. (2010). College Students’ Difficulty in Employment: From the Perspective of Wage and Welfare Rigidity. Chinese Talents, 22, 169–170.

He, Y. H. (2009). The Changes of the Rate of Return to Education: An Empirical Study Based on the Data of CHNS. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2, 44–54.

Krahn, H., Derwing, T., Mulder, M., & Wilkinson, L. (2000). Educated and underemployed: Refugee integration into the Canadian labour market. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 1(1), 59–84.

Lai, D. S. (2001). Segmentation of Labor Market and Graduate Unemployment. Journal of Beijing Normal University (humanities and Social Sciences Edition), 4, 69–77.

Lai, S., & Education. (1998). Labour Market and Income allocation. Economic Research, 5, 42–49.

Li C. A. (2017). Degree Inflation Is Waste of Knowledge, Global Times, https://opinion.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnK5YRV, last visited on 17th Sptember, 2022.

Li X. G. (2021a). High Academic Qualification but Low Requirements of Jobs: Did Our Education Mismatch the Job Requirements? GuangMing Daily, 25th March, 2021a, https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2021a-03/25/nw.D110000gmrb_20210325_5-02.htm, last visited on April 6, 2022.

Li, W. F. (2021b). Research on Dynamic Management Mechanism of Organization Establishment. Research of Administrative Science, 8(12), 4.

Liversage, A. (2009). Vital conjectures, shifting horizons: High skilled female immigrants looking for work. Work, Employment and Society, 23(1), 120–141.

Lu, H. M., & Li, C. G. (2005). Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities: Humanities and Social. Science, S1, 68–69.

Luo H. Q. (2017). The Study of Midland Court Clerks Turnover Influencing Factors on the Court of J city in J province, Master’s thesis of East China University of Politial Science and Law.

Ma, L. P., & Yue, C. J. (2011). Research on the segment of labor market and the employment flow of college graduates. Research in Educational Development, 3, 1–7.

McGuinness, S. (2006). Overeducation in the labour market. Journal of Economic Surveys, 20(3), 387–418.

Pan L. (2018). Investigation and research on the professional status of court clerks in Guiyang, Master’s dissertation.

Qi, H. G., Zhao, M. F., Liu, S. H., Gao, P., & Liu, Z. (2022). Evolution pattern and its driving forces of China’s interprovincial migration of highly-educated talents from 2000 to 2015. Geographical Research, 41(2), 456–479.

Sunita, D., & Ronald, E. L. (2005). Brain drain from developing countries: how can brain drain be converted into wisdom gain? Journal of the Royal Society Medicine, 98(11), 487–491.

Wagner, R., & Childs, M. (2006). Exclusionary narratives as barriers to the recognition of qualifications, skills and experience—A case of skilled migrants in Australia. Studies in Continuing Education, 28(1), 49–62.

Wang, B. Y. (2010). Research on the employment difficulty of college students from the perspective of macroeconomic policy. Education Exploration, 10, 131–134.

Wise, S., Schutz, H., Healy, J. and Fitzpatrick, D. (2011). Engineering Skills Capacity in the Road and Rail Industries, Workplace Research Centre, University of Sydney and the National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University, ANET Sydney, 102.

Wu, X. G. (2016). Higher education, elite formation and social stratification in contemporary China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 36(3), 1–31.

Yoshida, Y., & Smith, M. R. (2005). Training and the earning of immigrant males: Evidence from the Canadian workplace and employee survey. Social Science Quarterly, 86, 1218–1241.

Zhou, J. G. (2008). Social Transformation and Social Problems (pp. 194–200). China, Gansu People Publishing Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, W., Bai, M. & Gu, R. The Skills Wastage of Contract Court Clerks in China: Assessment and Countermeasures. Soc Indic Res 170, 99–116 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03049-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03049-7