Abstract

Financial development may affect poverty directly and indirectly through its impact on income inequality, economic growth, and financial instability. Previous studies do not consider all these channels simultaneously. To proxy financial development, we use the ratio of private credit to GDP or an IMF composite measure. Our preferred measure for poverty is the poverty gap, i.e. the shortfall from the poverty line. Our fixed effects estimation results for an unbalanced panel of 84 countries over the 1975–2014 period suggest that financial development does not have a direct effect on the poverty gap. However, as financial development leads to greater inequality, which, in turn, results in more poverty, financial development has an indirect effect on poverty through this transmission channel. Only if we use poverty lines of $3.20 or $5.50 (instead of $1.90 a day as in our baseline model) to define the poverty gap, we find that economic growth reduces poverty. This implies that in those cases the overall effect of financial development on poverty may be positive or negative, depending on which indirect effect, i.e. that of income inequality or growth, is stronger. Financial instability does not seem to affect the poverty gap. These results are consistent across various robustness checks.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

While the relationship between financial development and income inequality has received a lot of attention (see de Haan & Sturm, 2017 for a survey), there is a much smaller but rapidly growing literature on the relationship between financial development and poverty. Fighting poverty is the first of the United Nations’ (UN) sustainable development goals. According to the UN, more than 700 million people, or 10 per cent of the world population, still live in extreme poverty today, struggling to fulfil the most basic needs, such as health, education, and access to water and sanitation.Footnote 1

Figure 1 summarizes how, according to previous studies, financial development may affect poverty. Financial development may affect poverty via four channels. First, financial development may have a direct impact on poverty. Theory provides conflicting predictions about the impact of financial development on the incomes of the poor. On the one hand, financial development may reduce poverty as several financial imperfections, such as information and transactions costs, may be especially binding on the poor who lack collateral and credit histories. Relaxation of these constraints will benefit the poor (Beck et al., 2007). However, according to other theories, financial development primarily helps the rich. As the poor mainly rely on informal family connections for capital, improvements in the services of the formal financial sector inordinately benefit those already purchasing financial services (Greenwood & Jovanovic, 1990). Rajan and Zingales (2003) and Claessens and Perotti (2007) argue that the financial system mainly benefits the rich and elites with strong political connections, leaving out the poorer fractions of the population. However, as shown in more detail in Sect. 2, most previous empirical studies suggest that financial development reduces poverty.

Financial development may also indirectly affect poverty. Here it is important to distinguish between an indirect, a mediating and a conditioning effect. In case of an indirect effect, financial development is not related to poverty but is related to another variable that, in turn, is related to poverty. In case of a (full) mediating effect, financial development, if considered in isolation, has an effect on poverty but this runs via its impact on another variable (in our case: economic growth, income inequality or financial instability) which is related to poverty. Including these other variables makes financial development become less significant (insignificant). In case of a conditioning effect, the effect of one of these variables on poverty depends on the level of financial development.

Financial development may enhance economic growth, which, in turn, may reduce poverty.Footnote 2 There is a large literature showing that financial development promotes economic development (at least up to a point). A well-developed financial system channels savings into value-creating investments, monitors borrowers to increase efficiency, facilitates to pool, share and diversify risk, and enables trade. King and Levine (1993) were among the first to argue that financial development is related to economic development. Most studies in this line of research report evidence that financial development stimulates economic growth (Levine, 2005). However, some recent studies suggest that the relationship between financial and economic development may be non-linear.Footnote 3

Another indirect channel is that financial development may affect the poor through its effect on the distribution of income.Footnote 4 A more equal income distribution is generally associated with less poverty. So, depending on whether financial development increases or decreases income inequality, this income distribution effect will mitigate or enhance the potential beneficial direct effects of financial development on the poor (Beck et al., 2007). There is an extensive literature on the impact of financial development on income inequality. As shown in the survey of de Haan and Sturm (2017), the results in this line of literature are very mixed. Most studies conclude that countries with higher levels of financial development have less income inequality but several more recent studies report that financial development increases income equality (e.g. de Haan & Sturm, 2017; Jaumotte et al., 2013).

Finally, financial development is often associated with more financial instability which, in turn, may affect poverty. Some recent studies report that financial crises lead to more income inequality (cf. de Haan & Sturm, 2017). Furthermore, financial instability generally leads to macroeconomic instability that, in turn, may hurt the poor (Guillaumont Jeanneney & Kpodar, 2011).

Our empirical approach is as follows. We first examine the direct effect of financial development, controlling for the other factors shown in Fig. 1 as well as some other controls suggested in the literature. If financial development is significant in case it is the only explanatory variable and becomes less significant (or insignificant) once controls are included, that would provide support for a (full) mediating relationship. Next, we examine whether there is evidence in support of an indirect effect of financial development via economic growth, income inequality and financial instability (i.e., we examine whether financial development is related to any of these variables). Finally, we check for conditional effects by including interaction effects, i.e. we examine whether the effect of economic growth, income inequality and financial instability on poverty depends on the level of financial development.

This paper provides new evidence on the relationship between financial development, measured as the ratio of private credit to GDP, and poverty. We improve upon previous studies by: (1) Using the poverty gap instead of headcount poverty (i.e. the share of the population living below a certain daily income level) as the poverty gap takes the depth of poverty into account. The poverty gap is the mean shortfall in income or consumption from the poverty line, expressed as a percentage of the poverty line and taking into account the share of the population considered poor. (2) Considering the (direct and indirect) effects of financial development on the poverty gap as shown in Fig. 1. (3) Employing a panel of 84 countries over the period 1975 to 2014 that is determined by data availability using 5-year averages (instead of annual observations or cross-section data).Footnote 5 One reason for employing 5-year averages is that poverty is a slow-moving variable and using annual data may capture variability due to business cycle fluctuations rather than structural developments. Furthermore, annual macroeconomic data, notably on inequality, are noisy.Footnote 6 (4) Checking whether our results are robust if we use a composite index of financial development, as developed by the IMF, instead of the usually employed private-credit-to-GDP ratio.

Our main findings suggest that financial development is not directly related to the poverty gap. This outcome is in contrast to the result of most previous studies, which report that financial development reduces poverty.Footnote 7 Our results also indicate that less income inequality is related to a lower poverty gap. Indirectly, financial development therefore increases poverty as our results suggest that financial development leads to more income inequality. Only if we use poverty lines above $1.90 to define the poverty gap, we find that economic growth is associated with lower poverty, allowing financial development to reduce the poverty gap through economic growth. Financial instability does not seem to affect the poverty gap. Our results for conditional effects suggest that the effect of income inequality on the poverty gap is increasing with the level of financial development. In contrast, the marginal effect of economic growth is decreasing with financial development, while there is no conditional effect of systemic banking crises.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses how previous studies have estimated the relationships shown in Fig. 1, thereby explaining in more detail how our study contributes to the literature. Section 3 outlines our methodology and data, while Sect. 4 presents our main findings. Section 5 offers a robustness analysis and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Previous Studies

Analyzing the relationship between financial development and poverty implies dealing with several issues. First, one needs a proxy for poverty. Table 1 provides a detailed survey of multi-country studies examining the relationship between financial development and poverty.Footnote 8 It shows that most previous studies employ the share of the population living beyond a certain level of real income, say 1 dollar per day (headcount poverty). In our view, the poverty gap is a better indicator than headcount poverty, because the latter simply counts the people below the poverty line and considers all the people below the line as equally poor while the poverty gap also takes the depth of poverty into account (Ravallion & Bidani, 1994).Footnote 9 The definition of the poverty gap according to the World Bank (2018) is the mean shortfall in income or consumption from the poverty line while counting the non-poor as having zero shortfall, expressed as a percentage of the poverty line. Therefore, the poverty gap is comparable across countries. The World Bank provides data using three different poverty lines: $1.90, $3.20 and, $5.50 a day. People who live below the $1.90 line live in extreme poverty. Therefore, we will use the poverty gap definition based on the poverty line at the $1.90 level in our main analysis. As part of our robustness analysis, we consider other values of the poverty line.

Second, a measure for financial development is needed. As Table 1 shows, most studies use private credit divided by GDP to proxy financial development. In fact, this holds for most studies on the causes and consequences of financial development (cf. Doucouliagos et al., 2020). This measure excludes credit to the central bank, development banks, the public sector, credit to state-owned enterprises, and cross claims of one group of intermediaries to another. Thus, it captures the amount of credit channeled from savers, through financial intermediaries, to private firms. It has advantages over alternative measures of financial development, such as M3 over GDP, which does not measure a key function of financial intermediaries, namely channeling society’s savings to private sector projects (Beck et al., 2007). In addition, the evidence of Gimet and Lagoarde-Segot (2011) and Naceur and Zhang (2016) suggests that the impact of financial development on income inequality runs via the banking sector rather than via capital markets. As banks are the main providers of credit, we use the private credit-to-GDP ratio as an indicator of financial development in our main analysis. We do not consider indicators of capital market development as many countries in our sample have underdeveloped capital markets.

Even though it is widely used, the private-credit-to-GDP ratio does not capture several dimensions of financial development, like access to credit and efficiency of the financial system. The IMF provides data on these and other dimensions of financial development. As a robustness test, we have therefore estimated our models using the IMF financial development index. This index is based on nine indices that summarize how developed financial institutions and financial markets are in terms of their depth, access, and efficiency.Footnote 10 These indices are then aggregated into an overall index of financial development (see Svirydzenka, 2016, for further details).

Third, the research methodology has to consider the complicated relationships between the key variables as shown in Fig. 1: poverty, income inequality, economic growth and financial instability (see Sect. 3). As outlined previously, we not only estimate the direct impact of financial development on poverty, but also examine the mediating and conditioning effects of income inequality, economic growth and financial instability on the poverty gap.

Table 1 summarizes how previous multi-country studies have dealt with these issues. Honohan (2004) is one of the first studies showing on the basis of a cross-country analysis that financial depth is negatively related to headcount poverty. Jalilian and Kirkpatrick (2005) cover several of the relationships shown in Fig. 1 by running separate regressions for the relationships between financial development (proxied by private credit to GDP), inequality and growth,Footnote 11 and poverty and GDP per capita. These estimates are used to distill the effect of growth and inequality on poverty, although the authors do not estimate the direct effect of financial development on poverty. They conclude that there “is no indication in our analysis that the growth effect of financial development is unequally shared; more specifically, as a result of financial development the income of the poor changes as much as average income.” (p. 653).

Beck et al. (2007) employ cross-country regressions in which the period considered differs per country, depending on the availability of headcount poverty. These authors also consider the effects of economic growth and inequality. They do so by including mean income growth and its interaction with initial Gini coefficients in the regression for poverty, claiming that this controls “for the impact of financial development on changes in headcount [poverty] through aggregate growth and therefore isolate the impact of financial development on changes in headcount [poverty] through changes in the distribution of income. The findings suggest that private credit is associated with poverty alleviation not just by fostering economic growth, but also by lowering income inequality.” (p. 43). Unfortunately, this conclusion is unjustified as the authors do not include the initial Gini coefficient as a separate term in the model. Furthermore, including an interaction term between income inequality and growth does not isolate the effects of growth on poverty.

Based on panel estimates for a large set of developing countries, Guillaumont Jeanneney and Kpodar (2011) conclude that financial development is on average good for the poor, with the direct effect being stronger than the effect through economic growth. However, this result is more robust when financial development is measured by the M3-to-GDP ratio than by the credit-to-GDP ratio. These authors also conclude that financial instability (constructed as the residual of financial development on its own lags and a linear time trendFootnote 12) hurts the poor and partially offsets the benefits of financial development.

Using a method inspired by traditional time-series Granger-causality tests, Perez-Moreno (2011) finds that if financial development is measured by the private credit-to-GDP ratio, it has no causal relationship with headcount poverty. However, when measuring financial deepening by the ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP, the results are more supportive for the view that finance reduces poverty.

Donou-Adonsou and Sylwester (2016) provide evidence that financial sector development (proxied by private credit to GDP) reduces poverty using both headcount poverty and the poverty gap using a panel of LDCs. They include GDP per capita (but not economic growth) and the Gini coefficient as explanatory variables, which have a significantly negative and positive coefficient, respectively. To deal with the potential endogeneity of financial development, they use rule of law and ethnic tensions as instruments. A similar approach has been used by Naceur and Zhang (2016) who also find that financial development reduces poverty (but these authors do not take the effects of income inequality and economic growth on poverty into account).

The paper that comes closest to ours is Seven and Coskun (2016). These authors estimate the relationship between financial development, income inequality and poverty for a sample of 45 emerging economies over the period 1987–2011 using four-year averages. They conclude that “while financial sector development contributes to long-run economic growth, it may not be beneficial for those on low-incomes” (p. 36). The main differences between this and the present study are that we use the poverty gap as the dependent variable (instead of income growth of the poorest quintile and headcount poverty) and consider the indirect impact that financial development may have on the poverty gap via financial instability, economic growth and income inequality. Furthermore, our sample is considerably larger and includes all countries for which data is available, while we also check whether our results are robust for using a proxy for financial development as constructed by the IMF, which captures several dimensions of financial development, instead of the private-credit-to-GDP ratio.

Rewilak (2017) uses four measures of financial development: financial depth, the accessibility of the financial system, the efficiency of the financial system and financial stability. Drawing on a cross-section of developing countries over the period 2004–15, he finds that (instrumented) financial depth reduces poverty, defined as headcount poverty at $1.90 ($3.10) a day. In contrast to Guillaumont Jeanneney and Kpodar (2011), Rewilak (2017) finds that financial instability (proxied by impaired loans) is not related to poverty reduction. However, Kiendrebeogo and Minea (2016) report that financial instability increases poverty in their panel estimates for CFA Franc Zone countries, thereby counteracting the direct poverty reducing effect of financial development.

Cepparulo et al. (2017) use both cross-section and panel estimates for up to 58 countries over the period 1984–2012. They show that financial development (proxied by the ratios of private credit, M3 and bank assets to GDP) reduces headcount poverty but less so if institutional quality is high. When these authors include economic growth, the financial development variables remain significant. In contrast to Kiendrebeogo and Minea (2016), these authors also find that institutional quality and financial development are substitutes in reducing poverty. The same result is found by Rashid and Intartaglia (2017) who report that financial development (proxied by M3 and private credit) reduces poverty (proxied by both headcount poverty and the poverty gap) using an unbalanced sample of developing countries covering the period 1985–2008. Their results suggest that financial development has larger effects on poverty reduction when institutional arrangements are sound.

Recently, Kaidi et al. (2019) have examined the relationship between financial development and poverty using panel data for a large set of countries over the 1980–2014 period. However, these authors employ a rather unusual indicator of poverty in their main analysis, namely household final consumption expenditure. In our view, this variable does not capture poverty but rather economic development. In their robustness analysis, Kaidi et al. (2019) use the poverty gap for a smaller set of countries. In most of their regressions, financial development increases poverty.

This review of the literature shows that research to date suffers from some shortcomings. First, most previous studies do not use the poverty gap even though this takes the depth of poverty into account in contrast to headcount poverty.

Second, most previous research is either based on cross-section data or annual panel data. We prefer using a large panel of countries with 5-year averages. Except for Seven and Coskun (2016), Cepparulo et al. (2017), and Rashid and Intartaglia (2017), previous panel studies employ annual data. We use five-year non-overlapping averages for three reasons (see also Dabla-Norris et al., 2015; de Haan & Sturm, 2017). For one thing, annual macroeconomic data are noisy, and this applies especially for data on income inequality (Delis et al., 2014). Furthermore, annual income inequality data are generally imputed for years for which no information was available in the underlying databases (there are only infrequent measures of inequality for much of Africa, Latin America, and Asia). Finally, we are not interested in short-term, i.e. business cycle, driven effects.

Third, none of the studies discussed considers all the indirect effects of financial development on the poverty gap as shown in Fig. 1. Some include the indirect channels via growth, inequality and financial instability, but not simultaneously. Furthermore, the proxies used in previous studies for financial instability may be criticized.Footnote 13 In our empirical analysis, we will use the occurrence of banking crises as a proxy for financial instability following de Haan and Sturm (2017).

3 Empirical Model and Data

We use a panel model instead of OLS cross-section regressions in our main analysis. As pointed out by Beck et al. (2007), a panel model has several advantages compared to cross-country regressions as the latter do not fully control for unobserved country-specific effects and do not exploit the time-series dimension of the data. The baseline fixed effects model estimated is:

where Poverty is the poverty gap, FD is financial development, Growth is average GDP growth, Inequality is the Gini coefficient, Crisis denotes the occurrence of a banking crisis and X is a vector of control variables, while u denotes the error term. The first terms in the equation denote country and time fixed effects. The country fixed effects control for country-specific factors that may impact poverty. Using these fixed effects removes the effect of time-invariant characteristics so we can assess the net effect of the variables of interest on poverty. We include time fixed effects to control for factors affecting all countries that might affect the results and, hence, have to be accounted for. Time lags are used to avoid endogeneity issues (but this may not be sufficient and therefore we consider alternative approaches below).

Data on the poverty gap, financial development and GDP growth are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). People who live below the $1.90 line live in extreme poverty. Therefore, our poverty gap definition in the main analysis is based on the poverty line at the $1.90 level. We follow most of the literature and measure financial development by private credit divided by GDP in our main analysis. For FD we take values at the end of the five-year period preceding the period covered by the poverty gap (which is a five-year average). We proxy income inequality by the Gini coefficient from Solt’s (2009) Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID). We use the index that represents household income before taxes, as this is in our view the best proxy for income inequality before redistribution via the tax system.Footnote 14 As pointed out by Delis et al. (2014) and Solt (2015), the SWIID database is the most comprehensive database and allows comparison across countries, because it standardizes income. The Gini coefficient is derived from the Lorenz curve and ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (perfect inequality). We construct averages of the Gini coefficients across five years where the Gini coefficients are centered at the middle of the five-year period. Our banking crisis data come from Laeven and Valencia (2013) who provide information on the timing of systemic banking crises. Our crisis variable is equal to one when a banking crisis started in the five-year period and zero otherwise.

The additional control variables are standard in the literature and include: the inflation rate that proxies macroeconomic stability, education, (the log of) the ratio of government consumption spending to GDP and the KOF globalization index. Data are from the WDI database, except for the KOF trade globalization index. The KOF globalization index measures the economic, social and political dimensions of globalization (see Gygli et al., 2019 for further details). It is based on de facto and de jure measures and ranges from 0 to 100. We use the de facto trade globalization index, which is largely based on trade in goods and services.

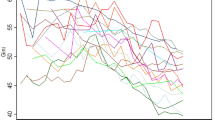

Table 2 shows summary statistics and Table 3 presents the correlations between the four main variables of interest. Table 2 suggests that the countries in our sample have very diverse levels of financial development; likewise, the poverty gap differs substantially across the countries in our sample, see also Fig. 2. The correlations of the explanatory variables are generally low; the highest correlation is found between the poverty gap and the Gini coefficient. However, it is not so high that it indicates serious multicollinearity issues. Finally, the high correlation between the two proxies for financial development is remarkable as the IMF financial development measures takes several dimensions of financial development into account and not only financial depth.

In addition, Fig. 3 shows scatter plots of poverty with: financial development (Fig. 3a); economic growth (Fig. 3b); and income inequality (Fig. 3c). The graphs suggest a (weak) positive relationship between financial development and the poverty gap and also between the Gini coefficient and the poverty gap, while there seems to be no relationship between growth and the poverty gap (Fig. 3b).

4 The Effect of Financial Development on the Poverty Gap

Table 4 shows our first estimation results. We start by estimating the relationship between financial development and the poverty gap (column 1). In subsequent columns we add economic growth, income inequality, banking crises, and the control variables. The results in Table 4 suggest that financial development is not related to poverty. The only variable with a coefficient that turns out to be robustly and significantly different from zero at the 5 percent level is the Gini coefficient.Footnote 15 Its positive coefficient shows that higher income equality is related to less poverty. The coefficient on economic growth is consistently negative, but never turns significant at conventional levels. The coefficient on the banking crisis dummy is not significant.

Of the controls, only the coefficient on education is significantly different from zero, suggesting that more education implies less poverty. Our results do not suggest that globalization has had an effect on poverty.

The evidence in Table 4 shows that financial development is not directly related to the poverty gap.Footnote 16 However, financial development may have an indirect effect via its impact on income inequality, which we find to be a significant driver of the poverty gap. The results in Table 4 suggest that the other indirect channels (growth and financial instability) are not significant. We therefore zoom in on the relationship between financial development and income inequality to examine whether financial development has an indirect effect on poverty via income inequality. (Tables A3 and A4 in the Appendix show the results for the relationship between financial development and economic growth and between financial development and financial instability).

Table 5 shows the estimates of a model similar to that used by de Haan and Sturm (2017). The left-hand side variable is income inequality as proxied by the gross Gini coefficient. The right-hand side variables are the lag of financial development, the lag of financial crisis, and globalization (the only control variable these authors found to be significant). In line with the results of de Haan and Sturm (2017), our findings suggest that financial development is increasing market-based income inequality.

Finally, we have examined whether financial development has a conditioning effect, i.e. that the impact of income inequality, economic growth and financial instability on the poverty gap depends on the level of financial development. For that purpose, the model in Eq. (1) is extended by including the interaction of financial development and one of these three variables. Table 6 shows the estimation results and Figure A1 in the Appendix shows the corresponding marginal effect plots. Our findings indicate that the effect of income inequality on the poverty gap is increasing with the level of financial development. In contrast, the marginal effect of economic growth is decreasing with financial development, while there is no conditional effect of systemic banking crises.

5 Robustness Analysis

5.1 Alternative Measure for Financial Development

In this section, we perform five sets of robustness tests. First, we estimate the models shown in Tables 4 and 5 using the IMF composite index for financial development instead of the private-credit-to-GDP ratio to proxy financial development. Tables 7 and 8 show that our main results are robust for using this alternative measure. The results reported in Table 7 do not suggest that financial development has a direct effect on the poverty gap, while the results shown in Table 8 confirm that financial development has an indirect effect on poverty via its effect on income inequality.

5.2 Alternative Measure for the Poverty Gap

Next, we employ different income levels to define the poverty gap. In our main analysis, the poverty gap was defined based on the poverty line at the $1.90 level. In Table 9, we employ poverty gaps based on higher levels of the poverty line. Here we only include education as a control variable in view of the results of Table 4. The estimates suggest that our main results hold, except for economic growth. There is no evidence of a direct effect of financial development on the poverty gap, except for the small negative effect on the $5.50 poverty gap in column (10). But, in line with our previous findings, there is an indirect negative effect of financial development as financial development leads to more income inequality, which, in turn, is associated with a higher poverty gap. The main difference with our previous finding is that we now find support for a poverty-reducing effect of economic growth. This result is in line with the outcomes of some previous studies. Overall, our results thus suggest that economic growth is not benefitting the poorest segments of society, but improves the position of the poor which are doing slightly better. As there is ample evidence that financial development has a positive (but probably non-linear) relationship with economic growth, this leads to the conclusion that the overall effect of financial development on the poverty gap may be positive or negative, depending on which indirect effect, i.e. that of income inequality or growth, is stronger.

5.3 Results for Headcount Poverty

In the third robustness check, we replace the poverty gap by headcount poverty as the dependent variable. Again, we only include education as a control. Table A5 in the Appendix shows the results, following the same set-up as in Table 4. The results are very much in line with our previous findings. We do not find evidence for a direct effect of financial development on poverty, while there is a very strong indirect effect via income inequality. In line with the results reported in Table 9, we find some (weak) evidence in support of an indirect channel via economic growth.

5.4 Advanced Versus Developing Countries

As the impact of financial development on the poverty gap may differ across developing and advanced economies, we have redone the regressions shown in Table 4 for these different subsamples. The advanced economies include countries from the high and upper middle income group, as defined by the World Bank, while we included low and lower middle income countries in the developing sample. The results suggest that the effect of financial development on the poverty gap is robust across different samples. In particular, there is no statistically significant effect of financial development on the poverty gap in advanced and developing countries (Table 10).

5.5 Instrumental Variables

Finally, Table 11 shows the results of instrumental variables (IV) estimations. We use IV in order to address potential endogeneity concerns using two external instruments for financial development. Both instruments are based on the assumption that geographically close countries have similar levels of financial development.Footnote 17 The first instrument considers the level of financial development of the closest country, measured by its geographical distance, following a method similar to that of Stanga et al. (2020). As many island states in our dataset do not have direct neighbours, we apply a distance-based approach. In particular, we instrument the level of financial development in a country by the level of its closest country, which is measured by the distance of the two largest cities. The second instrument is based on the approach used in Pleninger and Sturm (2020), where the level of financial development is instrumented by an average of all other countries’ financial development level, weighted by their distance to the respective country. The following equation denotes the mathematical representation of the second instrument:

where \(DomCred_{{j,t - 5{ }}}\) is the lagged percentage of domestic credit to private sector to GDP of country j in year t.

In Table 11, the statistic on the joint relevance of instruments tests the joint effect of the two instruments on financial development in the first stage. The low p-values indicate that our instruments are relevant. The Hansen J statistic tests the overidentifying restrictions. For all estimations, the values of the test statistics show that the null of instrument validity cannot be rejected.

In general, the results presented in Table 11 show a close resemblance to the fixed-effects regression results reported in Table 4. The results suggest that there is no direct relationship between financial development, proxied by domestic credit to the private sector, and the poverty gap.

6 Conclusion

This paper contributes to the small but rapidly growing literature on the relationship between financial development and poverty. Financial development may affect poverty directly and indirectly through its effects on economic growth, income inequality and financial instability. Our discussion of previous studies shows that none of these studies considers all these channels simultaneously. Furthermore, most previous studies do not use the poverty gap even though this takes the depth of poverty into account in contrast to headcount poverty. Finally, previous research is either based on cross-section data or annual panel data. We prefer using a large panel of countries with 5-year averages.

Our results for an unbalanced panel of 84 countries over the period 1975 to 2014 suggest that financial development does not directly reduce the poverty gap (or headcount poverty). As to the indirect effects, our results suggest that lower income inequality reduces poverty, but there is no effect of economic growth and financial instability. Indirectly, financial development increases poverty as it leads to more income inequality. These two main conclusions are robust for using the IMF composite index of financial development as proxy for financial development instead of the private-credit-to-GDP ratio. As to conditional effects, we find that the effect of income inequality on the poverty gap is increasing with the level of financial development. In contrast, the marginal effect of economic growth is decreasing with financial development, while there is no conditional effect of systemic banking crises.

Only if we use poverty lines of $3.20 or $5.50 (instead of $1.90) to define the poverty gap, we find that economic growth reduces poverty. This implies that in those cases the overall effect of financial development on poverty may be positive or negative, depending on which indirect effect, i.e. that of income inequality or growth, is stronger.

Availability of data and material

Data can be made available.

Code availability

Code can be made available.

Notes

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/ (last time accessed: 8 December, 2020).

For instance, Arcand et al. (2015) report that at intermediate levels of financial depth, there is a positive relationship between the size of the financial system and economic growth, but at high levels of financial depth, more financial development is associated with less growth. Likewise, Cecchetti and Kharroubi (2012) report that financial development has a non-linear impact on aggregate productivity growth. Based on a sample of developed and emerging economies, they show that the level of financial development is beneficial for growth only up to a point, after which it becomes a drag on growth.

As will be explained in more detail in Sect. 2, poverty is generally measured as the share of the population living below a certain level of income per day, while income inequality is generally proxied by the Gini coefficient. It is possible that an increase in income inequality is accompanied by a decrease in poverty, for instance, if the incomes of the rich increase more than the incomes of the poor. Although it is often thought that extreme poverty is confined to the poorest countries, most of the extreme poor no longer live in low-income countries but rather in middle-income countries (World Bank, 2018).

Our sample includes low- and high-income countries. The poverty gap is higher in low-income countries than in high-income countries. Still, in many high-income economies, the poverty gap is not zero (World Bank, 2020). We check whether the relationship between financial development and poverty differs across high- and low-income countries.

An exception is the recent study by Kaidi et al. (2019), who report that financial development increases poverty.

The table does not report single-country studies, such as Abosedra et al. (2016).

In the robustness section, we provide estimates using headcount poverty to check whether this affects our conclusions.

See: https://data.imf.org/?sk=f8032e80-b36c-43b1-ac26-493c5b1cd33b (last time accessed: 8 December, 2020).

The authors first regress GDP per capita on financial development and use the residuals as a proxy for all factors that affect GDP per capita growth, except financial development.

We have serious doubts that this measure actually captures financial instability. In our estimates, we use the occurrence of banking crises as a proxy for financial instability.

For instance, Naceur and Zhang (2016) measure stability of the financial system by the ratio of regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets and the volatility of the stock price index. Only Kiendrebeogo and Minea (2016) use the occurrence of financial crises to measure financial instability, which, in our view is the best proxy for financial instability.

Following, de Haan and Sturm (2017), we use the index that represents household income before taxes, as this in our view is the best proxy for income inequality before redistribution via the tax system. Although we acknowledge that government spending and taxes also affect income distribution measured by the gross Gini coefficient as argued by Bergh (2005), it is still a much better proxy than the net Gini coefficient as that for sure is heavily influenced by redistribution via taxes and transfers.

We also tested the results using net intead of the market-based Gini coefficient. The results do not differ qualitatively; they are available upon request.

We checked whether financial development has a non-linear relationship with the poverty gap by including the private-credit-to-GDP ratio squared. The results (available on request) do not provide evidence for this. The coefficient on private credit squared is not significantly different from zero.

References

Abosedra, S., Shahbaz, M., & Nawaz, K. (2016). Modeling causality between financial deepening and poverty reduction in Egypt. Social Indicators Research, 126, 955–969

Adams, R. H. (2004). Economic growth, inequality and poverty: Estimating the growth elasticity of poverty. World Development, 32(12), 1989–2014

Arcand, J., Berkes, E., & Panizza, U. (2015). Too much finance? Journal of Economic Growth, 20, 105–148

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality and the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 27–49

Bergh, A. (2005). On the counterfactual problem of welfare state research: How can we measure redistribution? European Sociological Review, 21(4), 345–357

Bergh, A., & Nilsson, T. (2014). Is globalisation reducing absolute poverty? World Development, 62, 42–61

Cecchetti, S., Kharroubi, E. (2012). Reassessing the impact of finance on growth. BIS Working Paper 381.

Cepparulo, A., Cuestas, J. C., & Intartaglia, M. (2017). Financial development, institutions, and poverty alleviation: An empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 49(36), 3611–3622

Claessens, S., & Perotti, E. (2007). Finance and inequality: Channels and evidence. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35, 748–773

Dabla-Norris, E., Kochhar, K., Ricka, F., Suphaphiphat, N., Tsounta, E. (2015). Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective. IMF Staff Discussion Note 15/13, IMF, Washington DC.

de Haan, J., & Sturm, J.-E. (2017). Finance and income inequality: A review and new evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 50(1), 171–195

Delis, M. D., Hasan, I., & Kazakis, P. (2014). Bank regulations and income inequality: Empirical evidence. Review of Finance, 18, 1811–1846

Dollar, D., Kleineberg, T., & Kraay, A. (2016). Growth still is good for the poor. European Economic Review, 81(C), 68–85

Dollar, D., & Kraay, A. (2002). Growth is good for the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 7(3), 195–225

Donou-Adonsou, F., & Sylwester, K. (2016). Financial development and poverty reduction in developing countries: New evidence from banks and microfinance institutions. Review of Development Finance, 6, 82–90

Doucouliagos, C., de Haan, J., Sturm, J-E. (2020). What drives financial development? A meta-regression analysis. CESifo Working Paper 8356, CESifo. Munich, Germany.

Duncan, D., & Sabirianova Peter, K. (2016). Unequal inequalities: Do progressive taxes reduce income inequality? International Tax and Public Finance, 23(4), 762–783

Gimet, C., & Lagoarde-Segot, T. (2011). A closer look at financial development and income distribution. Journal of Banking and Finance, 35, 1698–1713

Greenwood, J., & Jovanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 1076–1107

Guillaumont Jeanneney, S., & Kpodar, K. (2011). Financial development and poverty reduction: Can there be a benefit without a cost? The Journal of Development Studies, 47(1), 143–163

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Potrafke, N., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). The KOF globalisation index—Revisited. Review of International Organizations, 14, 543–574

Honohan, P. (2004). Financial development, growth and poverty: How close are the links. In C. Goodhart (ed.), Financial development and economic growth: Explaining the links. Palgrave.

Jalilian, H., & Kirkpatrick, C. (2005). Does financial development contribute to poverty reduction? Journal of Development Studies, 41(4), 636–656

Jaumotte, F., Lall, S., & Papageorgiou, C. (2013). Rising income inequality: Technology, or trade and financial globalization? IMF Economic Review, 61, 271–309

Kaidi, N., Mensi, S., & Ben Amor, M. (2019). Financial development, institutional quality and poverty reduction: Worldwide evidence. Social Indicators Research, 141(1), 131–156

Kappel, V. (2010). The effects of financial development on income inequality and poverty. CER-ETH Working Paper 10/127. ETH, Zürich.

Kiendrebeogo, Y., & Minea, A. (2016). Financial development and poverty: Evidence from the CFA Franc Zone. Applied Economics, 48(56), 5421–5436

King, R. G., & Levine, R. (1993). Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 717–737

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2013). Systemic banking crises database. IMF Economic Review, 61, 225–270

Levine, R. (2005). Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. In: Aghion, P., Durlauf, S. (eds.), Handbook of economic growth. North-Holland Elsevier Publishers.

Naceur, S.B., Zhang, R. (2016). Financial development, inequality and poverty: some international evidence. IMF Working Paper 16/32.

Perez-Moreno, S. (2011). Financial development and poverty in developing countries: A causal analysis. Empirical Economics, 41, 57–80

Pleninger, R., & Sturm, J. E. (2020). The effects of economic globalisation and ethnic fractionalisation on redistribution. World Development, 130, 104945

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (2003). The great reversals: the politics of financial development in the twentieth century. Journal of Financial Economics, 69, 5–50

Rashid, A., & Intartaglia, M. (2017). Financial development—Does it lessen poverty? Journal of Economic Studies, 44(1), 69–86

Ravallion, M., & Bidani, B. (1994). How robust is a poverty profile? The World Bank Economic Review, 8(1), 75–102

Rewilak, J. (2017). The role of financial development in poverty reduction. Review of Development Finance, 7(2), 169–176.

Sherawat, M., & Giri, A. K. (2016). Financial development, poverty and rural-urban income inequality: Evidence from South Asian countries. Quality and Quantity, 50, 1–14

Seven, U., & Coskun, Y. (2016). Does financial development reduce income inequality and poverty? Evidence from emerging countries. Emerging Markets Review, 26, 34–63

Solt, F. (2009). Standardizing the world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 231–242

Solt, F. (2015). On the assessment and use of cross-national income inequality datasets. Journal of Economic Inequality, 13, 683–691

Stanga, I., Vlahu, R., & de Haan, J. (2020). Mortgage arrears, regulation and institutions: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Banking and Finance, 118, 105889

Svirydzenka, K. (2016). Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. IMF Working Paper 16/5.

World Bank. (2018). Poverty and shared prosperity 2018: Piecing together the poverty puzzle. World Bank.

World Bank. (2020). Poverty and shared prosperity 2020: Reversals of fortune. World Bank.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fabian Weber for his research assistance and three referees for their very helpful comments on a previous version of the paper. All remaining errors are ours.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Haan, J., Pleninger, R. & Sturm, JE. Does Financial Development Reduce the Poverty Gap?. Soc Indic Res 161, 1–27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02705-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02705-8