Abstract

Most studies show that parents have a lower level of wellbeing than non-parents. An interesting question is if this is true in different contexts, such for instance different family policy contexts. Although there are common family policy goals for all member states of the European Union there are still major differences between states regarding the implementation and contents of various family policy measures. The aim of the article is to study the importance of family policy context and gender for the negative influence of having children on mental wellbeing. Data is derived from an extensive cross-country data set named European Social Survey Program (ESS). Family policy context is measured through the different family policies contexts that each state represents, resulting in a Nordic cluster (representing an extensive family policy context) and two clusters, the conservative and liberal, representing less extensive family policy contexts. Results in general show that the level of mental wellbeing is lower among people with children living at home than among people with no children at home. However, separate analyses of the family policy contexts indicate that this difference between those with and without children only exists in the conservative and liberal family policy contexts. Further, separate analyses of women and men in different family policy contexts show that the negative association between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing exist only among women in conservative and liberal contexts. This indicates that the family policy context is of importance for mother’s mental wellbeing but not for father’s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Most studies show that parents have a lower level of wellbeing than non-parents (Glass et al., 2016; Hansen, 2012; Mikucka & Rizzi, 2020; Stanca, 2012, Umberson et al., 2010). Since structural circumstances such as family policies can shape the experience of getting children, this study deals with the wellbeing of parents vs. non-parents in different family policy contexts. Although there are common family policy goals for all member states of the European Union there are still major differences between states regarding the implementation and contents of various family policy measures. In research related to organisation and characteristics of different types of social policy contexts and welfare states the Nordic states are normally classified as representing an extensive and a comprehensive family policy context (Backhans et al., 2011; Ellingsæter & Leira, 2006; Esping-Andersen, 2009; Eydal & Rostgaard, 2011; Korpi et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2008). Countries in continental Europe (often classified as conservative countries) and Anglo-Saxon countries (often classified as liberal countries) are categorised by a relatively passive family policy, which has resulted in a lower female employment rates and the preservation of traditional gender roles (Esping-Andersen, 2009; Korpi et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2008). This article will study if one can find support for that an extensive family policy context (represented by the Nordic regime) has a positive influence on parent’s mental wellbeing and if this is most prominent among women. Analyses are based on an extensive cross-country data set collected within the framework of European Social Survey (ESS).

2 Background

Having children is in general assumed to be a positive life event (Hansen, 2012). Most adults also become parents although there has been a general decline in birth rates during last few decades and the birth rates vary across European nations (OECD, 2020). Studies of attitudes to parenthood among young adults across the world show that almost everyone (90–95%) plan to have children when becoming adults. Further, a large majority of adult people believe that becoming a parent is central for experiencing a meaningful and fulfilling life and that childless people’s lives are emptier and lonelier than the lives of parents (Hansen, 2012).

However, most cross sectional and longitudinal studies of relationships between parenthood and happiness, life satisfaction and wellbeing indicate that parents in general have lower levels of happiness, life satisfaction and wellbeing than non-parents. Cross sectional results from various national contexts show some negative effects, indicating that parents are unhappier and less satisfied than people without children living at home (Glass et al., 2016; Hansen, 2012; Stanca, 2012; Umberson et al., 2010). Longitudinal results indicate that the level of life satisfaction drops quite dramatic after the birth of a child (Hansen, 2012; Mikucka & Rizzi, 2020; Umberson et al., 2010). There are some research studies questioning the picture that the occurrence of children in general is something negative for individual wellbeing. Some results indicate that parents are more satisfied than non-parents (Baetschmann et al., 2016; Pollmann-Schult, 2014).

Studies also indicate that it is not only a questions of if children are good or bad for wellbeing, some categories of parents can be more satisfied than other parents depending on the social context. Some results show that fathers are more satisfied than mothers, cohabitants/married parents are more satisfied than single parents, high educated parents are more satisfied than low educated parents and that the ages of the children also matters (Hansen, 2012; Nomaguchi, 2011; Umberson et al., 2010). Other factors that have shown to influence the level of wellbeing among parents are the level of experienced work-family conflict, (Liu et al., 2011) and access to childcare provision (Schmitz, 2019); the lower the work family conflict and the greater access to childcare provision, the higher parental wellbeing. However, few studies have analysed the importance of family policy context for parental wellbeing. Next section will discuss family policies in the European Union and the possible influence on parental wellbeing.

2.1 Family Policy and Parental Wellbeing

Even though the European Union has no common family policy the importance of this is highlighted in a number of legislative areas and documents, such us equal opportunities, labour law and working conditions, and social protection. A main political goal is to create gender equality and one central aspect of gender equality is to stimulate women and men to share work and family responsibilities (Borrell et al., 2014). The Council Directive, 2003/578/EC states that member states should translate their desire to promote equality of opportunity into increased employment rates for women. It is emphasised that particular attention should be given to reconciling work and family life. This should be brought about to a large extent by providing good quality care services for children, encouraging the sharing of family and professional responsibilities and facilitating return to work after a period of leave. It is particularly important that member states, through an adequate provision of care for children, remove disincentives to female labour force participation in order to support women’s entry, career and continued participation on the labour market. On a more concrete level the Barcelona European Council agreed that by 2010 member states should provide childcare for at least 90 percent of children between the age of three and school age and for at least 33 percent of children under the age of three years (Council Directive, 2003/578/EC).

A main question is to what extent these ambiguous family policy goals have been realised and implemented. A first modest achievement was the approval of the Council Directive on parental leave on 3 June 1996 (Council Directive 1996/34/EC). The agreement stipulates that workers shall have the right to at least three months unpaid parental leave for both natural and adopted children up to the age of 8 years. Both women and men should be granted an individual right to parental leave. In order to promote equal opportunities and equal treatment between men and women, and to encourage fathers to assume an equal share of family responsibilities, the right to parental leave should be granted on a non-transferable basis. There are, however, crucial differences in how far various states have come in the process of creating social and family policy measures with an aim to facilitate the combination of working and family obligations. Some countries have developed and implemented policies that encourage men and women to have double responsibilities, both as providers and carers, while other countries actively encourage more differentiated roles for women and men (Daly, 2005; Lewis, 2009).

In research related to organisation and characteristics of different types of social policy contexts and welfare states (Duncan, 1996; Esping-Andersen, 1999; Korpi & Palme, 1998; Lewis, 1992; Walby, 1994) the Nordic states are normally classified as representing an extensive and a comprehensive family policy context. Characteristics are encouragement for individual independence, mainly through paid labour in combination with universal schemes. The ideal is to maximize individual independence and to minimize family dependence. Family policy encourages female labour market participation, emphasises gender equality and women’s independence from men and aims at enable the combination of paid work and parenthood. As a result the female employment rate is almost as high among women as among men (Backhans et al., 2011; Ellingsæter & Leira, 2006; Esping-Andersen, 2009; Eydal & Rostgaard, 2011; Korpi et al., 2013; Lewis et al. 2008).

Conservative welfare states located in Central Europe are characterised by a relatively passive social policy and the preservation of traditional family ties and norms. Family policy consists mainly of support from the state for the male breadwinner family—meaning families consisting of a full time employed man and a woman who has the main responsibility for housework and childcare. There are few policy measures that aim at the breaking up the traditional division of labour and the strengthening of women’s independence from men. As a result the rate of female labour market participation rate is relatively low. Therefore, the Continental European states can be classified as representing a more traditional or conservative welfare state type characterised by a relatively traditional division of labour between women and men (Esping-Andersen, 2009; Korpi et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2008; Thévenon, 2011).

The United Kingdom and Ireland are examples of a liberal type of welfare regime where market-led solutions are preferred to state intervention. Although there is a political goal to create gender equality in a liberal welfare state, the state does little to facilitate this, and the result could be labelled a male breadwinner model where women’s incomes are secondary to men’s. Social policy measures are limited to means-tested benefits and modest social insurance plans, while private welfare schemes are stimulated. Both parental leave and the public provision of day-care centres are limited, which means that the government, to a relatively small extent, facilitates the combination of work and family obligations. This makes it difficult to raise children and at the same time go out to work (Esping-Andersen, 2009; Korpi et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2008; Strandh & Nordenmark, 2006).

In conclusion, states and different areas in Europe represent different family policy contexts. Some states, like the Nordic, have invested in an extensive and ambitious family policy with an aim to facilitate the combination of work and family responsibilities as well as gender equality. On the other side one can find conservative and liberal welfare regime types that have a relatively passive family policy, which has resulted in a lower female employment rate and the preservation of traditional gender roles. In the liberal type of welfare regime there is a political goal to create gender equality, but relatively little is done by the government to realise this goal.

Few studies have analysed how different social and family policy contexts influence parental wellbeing. However, there are studies that have looked at the relationship between types of welfare state and to what degree working obligations conflict with family obligations. Research on the experience of, so-called, work-family conflicts in different social policy contexts has shown varying results. Some have pointed out that people who live in national states with extensive social and family policy measures aimed at facilitating the reconciliation of work and family life experience more work-family conflicts than people living in states with a less extensive social and family policy (Cousins & Tang, 2004; Strandh & Nordenmark, 2006). However, some studies have argued for a reversed pattern (Crompton & Lyonette, 2006; Edlund, 2007). All together, the results have indicated that it may be hard to find systematic differences between types of social and family policy contexts and that the differences within clusters of contexts can be as prominent as the systematic differences between different social and family policy contexts.

A main question in this article is if it is possible to find systematic differences between extensive and more passive family policy contexts regarding parental wellbeing. A study of Glass et al. (2016) found that work-family reconciliation policies mediated the relationship between parenthood and happiness, which makes it likely that also mental wellbeing among parents is mediated by policy context. The most likely and logical relationship between family policy context and parental mental wellbeing is, perhaps, that parents who live in a policy context which strongly support mothers and fathers combination of work and family obligations should be more satisfied than parents living in a context where this is not as prominent. If this is the case, the difference in mental wellbeing between parents and non-parents should be smaller in a Nordic context. In the light of the fact that women have the main responsibility for household work and childcare in all types of contexts (Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010; Nordenmark, 2004) it is also more likely that mothers have lower levels of mental wellbeing than fathers, and that mothers in and extensive family policy context would benefit more from the policy than mothers living in a less extensive family policy context. In that case, the differences in mental wellbeing between mothers and non-mothers should be smaller in a Nordic context than in a conservative or a liberal context.

The aim of the article is to study the importance of family policy context and gender for the negative influence of having children on mental wellbeing. The following hypotheses will be tested:

-

1.

Parents living in an extensive (generous) family policy context (represented by the Nordic regime) will have a relatively higher level of mental wellbeing than parents in a less extensive family policy context (represented by the liberal and conservative regimes).

-

2.

Especially mothers in an extensive (generous) family policy context (represented by the Nordic regime) will have a relatively higher level of mental wellbeing than mothers living in a less extensive family policy context (represented by the liberal and conservative regimes).

3 Methods

Data is derived from European Social Survey Program (ESS), 2004. The ESS is a comparative study that includes more than 30 European countries. It includes thematic sections that appear cyclically across the investigation occasions. The survey is in all countries based on nationally representative random samples and conducted using face to face interviews. The 2004 investigation contains the in-depth theme ‘Family, work and well-being’ in 25 countries. The average response rate was 61.5 percent with no country having a lower response rate than 43.6 percent (France). Since people of older ages are usually not directly affected by the family policy this study will only include individuals under 66 years of age.

Family policy context is measured through the different family policies contexts that each state represents and on the basis on the discussion in the introduction there is a distinction between a Nordic cluster representing an extensive or generous family policy context and two clusters, the conservative and liberal, representing less extensive family policy contexts. The ESS includes the Nordic countries Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, which together form a typical extensive family policy context. Countries in continental Europe, Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, France, Luxemburg and Netherlands, are together with the liberal countries United Kingdom and Ireland, categorised as two groups representing relatively passive family policy contexts, at least in relation to the Nordic cluster.

When conducting comparative studies, it is always a question of which and how many countries and regions that should be included. On the one hand, it is a strength to cover many countries, but on the other hand, this increases the risk of including countries representing very different contexts. In general, countries located in southern and Eastern Europe are characterized by lower living standards (Eurostat, 2014), and the meaning and role of religion is different (Pew Research Center, 2018), in relation to countries in northern, western and central Europe. Although there are also some political, culture, economic, and organizational differences between the included countries, the reason for including the countries from northern, western and central Europe in the study is that they have more in common with each other than they have with the countries in southern Europe and countries located in the former Eastern Europe. This means that other country differences than family policy differences is somewhat more under control.

The dependent variable “Mental wellbeing” is measured by the WHO-Five Wellbeing Index (Löwe et al. 2004). Main reasons for the choice of this measure are that this index is widely used as a measure of mental wellbeing. Another strength with this measure is that it consists of five questions, which makes the measure more stable and broader than if one uses a single question as a measure. The index includes questions about whether during the last two weeks, the respondent has felt cheerful and in good spirits, has felt calm and relaxed, has felt active and vigorous, has woken up feeling fresh and rested and whether their daily life has been filled with things that interest them. The response alternatives vary in six steps from “at no time” to “all of the time”, and have been summed to form an additive index ranging from 0 to 25; a higher score indicates a higher level of mental wellbeing. Respondents with missing values are excluded (N = 98). As illustrated in Table 1 all questions are strongly correlated to one another (Pearson’s between 0.336 and 0.568). Only one correlation has a Pearson’s value under 0.4; the correlation between “has been calm and relaxed” and “daily life has been filled with things that interest me”. A factor analysis (principal component analysis, Varimax with Kaiser normalisation) showed a one-factor structure and Cronbach’s alpha of the five-item scale was 0.81.

The main independent variable “Children” is measured by the question; are there any children living at home or not? (1 = yes, 0 = no). The last analysis also includes a variable that combine the variables “Children” and “Family policy context”—“Children/Family policy”. Background variables included have been chosen because they are usually controlled for and because they, on the basis of the research presented in the background, can be assumed to influence the relationship between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing (e.g. Nomaguchi, 2011). Background characteristics included as independent variables are “Cohabiting/married” (1 = yes, 0 = no), “Age” (16–65 years), “Born in country” (1 = yes, 0 = no), “Years in education” (0–25 years) and “Employment status” (1 = employed, 0 = not employed).

One should bear in mind that there are some general problems to be aware of when analysing statistics generated from comparative surveys. First, the framing of questions and attitudes are context dependent, which means that certain questions may be understood and interpreted differently in different national contexts. Therefore, the results must be interpreted with caution. Second, there are some differences between the studied countries regarding sampling, representativeness and response rates (Svallfors, 1997). However, the respondents are weighted to assure that the samples correspond to comparable sources of statistics in each country. Weighs correct for different probabilities of selection, thereby making the sample more representative of a ‘true’ sample of individuals in each country (DWEIGHT), and ensure that each country is represented in proportion to its population size (PWEIGHT). This means that the samples should be close to nationally representative.

4 Results

The aim and the hypotheses are analysed as follows. The first table will show the distribution of background characteristics among women and men living in the different family policy contexts. Next, the mean values on the wellbeing index for women and men, with and without children, living in different family policy contexts will be presented. Finally, the relationship between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing, when controlling for background characteristics, will be analysed by performing separate OLS-regressions for the different family policy contexts. This final table also includes an analysis of how a variable that combine the variables ”Children” and “Family policy context” (Children/family policy) is related to mental wellbeing. This gives an indication of whether there are significant differences between family policy contexts/occurrence of children.

Table 2 shows how the background characteristics are distributed among women and men living in the different family policy contexts. It is more common that women are living together with children in all contexts but it is less common in the Nordic context (42.6%) in relation to the conservative (50.0%) and liberal (50.9%) contexts. It is less common that women and men are cohabitants/married in the liberal context in relation to the Nordic and conservative contexts. People are somewhat younger in the liberal context and it is most common that people are born in the country in the Nordic context. The employment rate is higher among men in all contexts but it is more common that both men and women are employed in the Nordic context in relation to the conservative and liberal contexts.

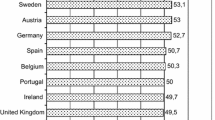

Table 3 shows mean values on the wellbeing index for women and men with and without children living in different family contexts. The second column in Table 3 illustrates mean values for all persons, both women and men. The mean values in italics indicate that the level of mental wellbeing in general is highest in the Nordic context (16.10) followed by the conservative context (15.67) and finally the liberal context (14.33). Further, the results show that there are significant differences between people with and without children in the conservative and liberal contexts, indicating a higher mental wellbeing among persons with no children living at home. The difference is non-significant in the Nordic context.

The results in italics for women and men separately indicate that the level of mental wellbeing in general is higher among men than among women in all contexts. Further, the results show that there are no significant differences between men with and without children living at home in all family policy contexts. However, among women there are significant differences between women with and without children in the conservative and liberal contexts, and the difference is most prominent in the liberal context. There is no significant difference between women with and without children in the Nordic context. This means that there are lower levels of mental wellbeing among women with children living at home in the conservative and liberal contexts but not among men. This also means that the significant differences in column two is explained by the fact that women with children have a lower mental wellbeing than women without children in the conservative and liberal contexts.

In the light of the results in Table 3, showing no significant differences among men, the OLS-regressions of the relationships between independent variables and the dependent variable mental wellbeing will be done only for women. In the first step a bivariate regression is performed of the relationship between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing in the different family policy contexts. In the next step of the regression there is an analysis of the relationship between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing when controlling for the background characteristics. The results from the regressions are presented in Table 4.

The results from the OLS-regressions in general confirm the results from Table 3. Results from the bivariate regressions in each context show that women with children have a significant lower mental wellbeing than women without children in the conservative and liberal contexts, but not in the Nordic context. This pattern is even more obvious in the multivariate analyses where the negative coefficients become higher; a change from -0.332 to -0.777 in the conservative context and -1.402 to -1.573 in the liberal context. The relationship between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing in the Nordic context is still not significant in the multivariate analysis.

The background characteristics are related to mental wellbeing as follow. Cohabitant/married women have a significant higher level of mental wellbeing in the conservative and liberal contexts, but not in the Nordic context. Age is significantly positively correlated to mental wellbeing in the Nordic context but significantly negatively correlated in the conservative context. Country of birth has no significant relationship with mental wellbeing but years of education is significantly positively related to mental wellbeing in the liberal context; the more years of education the higher the level of wellbeing. Employed women have a significant higher level of mental wellbeing than non-employed women in the Nordic and conservative contexts but there is no significant relationship between employment status and mental wellbeing in the liberal context.

The final column in Table 4 shows that the combination variable Children/Family policy is related to mental wellbeing as follows. There is no significant difference between women without and with children in the Nordic family policy context. However, mothers in the liberal and conservative contexts have a significant lower mental wellbeing than women without children in the Nordic context. Results also show that mothers in the liberal family policy context report a significant lower level of mental wellbeing than the reference category.

5 Discussion

The aim of the article was to study the importance of family policy context and gender for the negative influence of having children on mental wellbeing. The following hypotheses were tested: 1. Parents living in an extensive (generous) family policy context (represented by the Nordic regime) will have a relatively higher level of mental wellbeing than parents in a less extensive family policy context (represented by the liberal and conservative regimes). 2. Especially mothers in an extensive (generous) family policy context (represented by the Nordic regime) will have a relatively higher level of mental wellbeing than mothers living in a less extensive family policy context (represented by the liberal and conservative regimes).

Results show that the level of mental wellbeing is lower among people with children living at home than among people with no children at home. However, separate analyses of the family policy contexts indicate that this difference between those with and without children only exists in the conservative and liberal family policy contexts. Further, separate analyses of women and men in different family policy contexts show that the negative association between the occurrence of children and mental wellbeing exist only among women in conservative and liberal contexts. There is no difference in mental wellbeing between women with children and women without children in an extensive policy context (represented by the Nordic cluster) but the level of mental wellbeing is significant lower among women with children than among women without children in a more limited context (represented by the conservative and liberal clusters). This indicates that the study supports hypothesis 2, but not hypothesis 1, and that the family policy context is of importance for mother’s mental wellbeing but not for father’s.

In general, the results from this study support the studies that have indicated that the meaning of the occurrence of children for happiness, life satisfaction and wellbeing to some extent is context dependent (e.g. Hansen, 2012; Nomaguchi, 2011). More precise the results support studies that have shown that different welfare state types and social policies may have an impact on people’s life circumstances and perceptions (e.g. Cousins & Tang, 2004; Crompton & Lyonette, 2006; Edlund, 2007; Strandh & Nordenmark, 2006). In line with the study by Glass et al. (2016), which found that work-family reconciliation policies mediated the relationship between parenthood and happiness, this study support that family policies mediate the relationship between parenthood and mental wellbeing. A new insight from this study is that family policies may be of more importance for mother’s mental wellbeing than for father’s wellbeing. A possible explanation to this result is that mothers still have the main responsibility for the children and that policies aiming at enabling the combination of parenthood and employment is of greatest value for mothers.

On a more theoretical level this study support theories that try to explain some of the variation in the relationship between social roles and wellbeing by considering the policy context (e.g. Duncan, 1996; Esping-Andersen, 1999; Korpi & Palme, 1998; Lewis, 1992; Walby, 1994). The results from this study imply that policies can be an important tool in the struggle to reduce the stressors associated with parenthood. This is in turn of importance for the possibility to increase fertility rates. Results from this study support the notion that an expansion of family policies in parts of Europe that have relatively low fertility rates could stimulate especially women to become parents.

Some shortcomings of the study have to be mentioned. First, the aim of this article was to study the importance of family policy context by categorising countries depending on characteristics of the family policies within each country. One problem is that there is a heterogeneity within the different categories of countries that is not considered in this study. Another problem is that it is not certain that it is mainly the family policy context that is the explaining factor of the differences in parental wellbeing between categories of countries, it could also be other factors that differ between the countries. By conducting multilevel analyses, including macro indicators of family policies, this can be analysed more in depths in future studies. This study includes too few countries for multilevel analyses to work. Second, this study is based on cross-sectional data, which makes it hard to make causal interferences about the relationship between parenthood and mental wellbeing. Despite these shortcomings, the study provides interesting insights into cross-national variation in the relationship between parenthood and mental wellbeing among women and men.

The results from this study indicate that family policy matters for mother’s mental wellbeing. This implies that if one on a societal level wants to improve mother’s mental wellbeing one should expand public childcare provision and create a generous paid parental leave, aiming at enhancing the combination of employment and childcare. Also policy measures aiming at breaking up the traditional division of unpaid labour and increasing fathers involvement in childcare responsibilities should be introduced. These policy measures will probably increase the chances of healthy parenting, especially among mothers.

Availability of data and materials

ESS is available on internet (https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/).

References

Backhans, M. C., Burström, B., & Marklund, S. (2011). Gender policy developments and policy regimes in 22 OECD countries, 1979–2008. Gender Policy and Politics, 41(4), 595–623

Baetschmann, G., Staub, K. E., & Studer, R. (2016). Does the stork deliver happiness? Parenthood and life satisfaction. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 130, 242–260

Borrell, C., Palencia, L., Muntaner, C., Urquia, M., Malmusi, D., & O’Campo, P. (2014). Influence of macrosocial policies on women’s health and gender inequalities in health. Epidemiological Review, 36(1), 31–48

Cousins, C. R., & Tang, N. (2004). Working time and work and family conflict in the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK. Work. Employment and Society, 18(3), 531–549

Crompton, R., & Lyonette, C. (2006). Work-Life ‘Balance’ in Europe. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 379–393

Daly, M. (2005). Changing family life in Europe: Significance for state and society. European Societies, 7(3), 379–398

Council Directive (2003). 578 EC 22/07/2003.

Duncan, S. (1996). The Diverse worlds of European patriarch. In M. D. Garcia-Ramon & J. Monks (Eds.), Women of the European Union: The politics of work and daily life. Routledge.

Edlund, J. (2007). The work family time squeeze: conflicting demands of paid and unpaid work among working couples in 29 countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 48(6), 451–480

Ellingsæter, A. L., & Leira, A. (Eds.). (2006). Politicising parenthood in Scandinavia: Gender relations in welfare states. The Policy Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). The Incomplete Revolution. Polity Press.

Eurostat. (2014). Living conditions in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union.

Eydal, G. B., & Rostgaard, T. (2011). Gender equality revised – Changes in Nordic childcare policies in the 2000s. Social Policy & Administration, 45(2), 161–179

Glass, J., Simon, R. W., & Andersson, M. A. (2016). Parenthood and happiness, effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD Countries. American Journal of Sociology, 122(3), 886–929

Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and happiness, a review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108, 29–64

Korpi, W., Ferrarrini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in western countries re-examined. Social Politics, 20(1), 1–40

Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality and poverty in the Western countries’. American Sociological Review, 63, 661–687

Lachance-Grzela, M., & Bouchard, G. (2010). Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles, 63, 767–780

Lewis, J. (1992). Gender and the development of welfare regimes. Journal of European Social Policy, 2, 159–173

Lewis, J. (2009). Work-family balance, gender and policy. Edward Elgar.

Lewis, J., Campbell, M., & Huerta, C. (2008). Patterns of paid and unpaid work in Western Europe: Gender, commodification, preferences and the implications for policy. Journal of European Social Policy, 18(1), 21–37

Liu, H., Wang, Q., Keesler, V., & Schneider, B. (2011). Non-standard work schedules, work–family conflict and parental well-being: A comparison of married and cohabiting unions. Social Science Research, 40(2), 473–484

Löwe, B., Spitzer, R. L., Gräfe, K., Kroenke, K., Quenter, A., Zipfel, S., Buchholz, C., Witte, S., & Herzog, W. (2004). Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 78(2), 131–140

Mikucka, M., & Rizzi, E. (2020). The parenthood and happiness link: Testing predictions from five theories. European Journal of Population, 36(2), 337–361

Nomaguchi, K. M. (2011). Parenthood and psychological well-being clarifying the role of child age and parent-child relationship quality. Social Science Research, 41(2), 489–498

Nordenmark, M. (2004). Does gender ideology explains differences between countries regarding the involvement of women and men in paid and unpaid work? International Journal of Social Welfare, 13, 233–243

OECD (2020). Fertility rates (indicator). Retrieved 24 Sept 2020 from https://doi.org/10.1787/8272fb01-en.

Pew Research Center (2018). Eastern and Western Europeans differ on the importance of religion, views on minorities, and key social issues. Washington, D.C.

Pollman-Schult, M. (2014). Parenthood and life satisfaction, why don’t children make people happy? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76, 319–336

Schmitz, S. (2019). The impact of publicly funded childcare on parental well-being: Evidence from cut-of rules. European Journal of Population, 36, 171–196

Stanca, L. (2012). Suffer the little children, measuring the effects of parenthood on well-being worldwide. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 81, 742–750

Strandh, M., & Nordenmark, M. (2006). The interference of paid work with household demands in different social policy contexts: Perceived work–household conflict in Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands, Hungary and the Czech Republic. British Journal of Sociology, 57(4), 597–617

Svallfors, S. (1997). Worlds of Welfare and Attitudes to Redistribution: A Comparison of Eight Western Nations. European Sociological Review, 13(3), 283–304

Thévenon, O. (2011). Family policies in the OECD countries: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 57–87

Umberson, D., Pudrovska, T., & Reczek, C. (2010). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: A life course perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 612–629

Walby, S. (1994). Methodological and theoretical issues in the comparative analysis of gender relations in Western Europe. Environment and Planning, 26, 1339–1354

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nordenmark, M. How Family Policy Context Shapes Mental Wellbeing of Mothers and Fathers. Soc Indic Res 158, 45–57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02701-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02701-y