Abstract

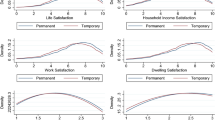

Migrants are believed to have higher aspirations than non-migrants. Furthermore, studies find that migration itself leads to even higher aspirations. One conventional explanation found in the literature is that migrants adapt their aspirations to their income relative to that of a new reference group. As this process continues migrants are miserably trapped on a hedonic treadmill. Alternatively, migration can be viewed as an investment in capabilities that can expand the aspirational window through the awareness of even better opportunities that lead to higher aspirations. If cities are viewed as places where migrants can accumulate human capital, the increase in aspirations after migration may be explained from an angle of expected returns to the human capital investment. Using two waves of Indonesian Family Life Survey (2000, 2007), this study presents tests of these two possible explanations about the change in aspirations after migration. To this end, this study uses a variable constructed by a difference between a migrant’s current level of subjective well-being and her future aspired level of well-being. The results cast doubt on the view that post-migration aspirations make migrants miserable in their migration destinations. Instead, this study finds ample evidence to support the view that migrants move to urban areas in order to accumulate human capital, looking forward to returns to their investment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The United Nations estimates that at least 860 million people live in slums across the developing world, with the number of slum dwellers growing by six million each year from 2000 to 2010 (UN Habitat 2013).

For instance, Czaika and Vothknecht (2014), using the same data, find evidence for a hedonic treadmill, but they do not examine the urban-based human capital investment theory.

As suggested by Kahneman and Deaton (2010), this study distinguishes between emotional well-being and life evaluation, two aspects of subjective well-being. The former refers to the emotional quality of an individual's everyday experience or affection that make one’s life pleasant or unpleasant. In contrast, the latter refers to the opinion on the quality of their life.

The relationship between the migration time and the accumulation of human capital, of course, may not be linear, but this is unlikely to be an issue in this study, which confines the migration time to be within the past 5 years.

Respondents were asked on which step on the ladder they were expected to be one year later in the 2000 survey.

This is equivalent to a subdivision of a city.

The happiness questions are available only in the survey of 2007, while the subjective evaluations of respondents’ living standards are available in both years.

The mean of the current level is 2.97 for migrants and 2.84 for non-migrants.

The results are not reported in the Table.

References

Amit, K. (2010). Determinants of life satisfaction among immigrants from Western countries and from the FSU in Israel. Social Indicators Research, 96(3), 515–534.

Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. In V. Rao & M. Walton (Eds.), Cultue and public action: A cross-disciplinary dialogue on development policy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Banerjee, B., & Kanbur, S. (1981). On the specification and estimation of macro rural–urban migration functions: With an application to Indian data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 43(1), 7–29.

Bartram, D. (2011). Economic migration and happiness: Comparing immigrants’ and natives’ happiness gains from income. Social Indicators Research, 103(1), 57–76.

Czaika, M., & Vothknecht, M. (2014). Migration and aspirations—are migrants trapped on a hedonic treadmill? IZA Journal of Migration, 3(1), 1–21.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111(473), 465–484.

Garrison, H. (1982). Internal migration in Mexico: A test of the Todaro model. Food Research Institute Studies, 18(2), 197–214.

Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., & Stillman, S. (2013). Accounting for selectivity and duration-dependent heterogeneity when estimating the impact of emigration on incomes and poverty in sending areas. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61(2), 247–280.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Kennan, J., & Walker, J. R. (2011). The effect of expected income on individual migration decisions. Econometrica, 79(1), 211–251.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010a). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010b). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2012). Aspirations, adaptation and subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. In Adaptation, poverty and development (pp. 91–110). London: Springer.

Lucas, R. E., Jr. (2004). Life earnings and rural-urban migration. Journal of Political Economy, 112(S1), S29–S59.

Nikolova, M., & Graham, C. (2015). In transit: The well-being of migrants from transition and post-transition countries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 112, 164–186.

Nowok, B., Van Ham, M., Findlay, A. M., & Gayle, V. (2013). Does migration make you happy? A longitudinal study of internal migration and subjective well-being. Environment and Planning A, 45(4), 986–1002.

Olgiati, A., Calvo, R., & Berkman, L. (2013). Are migrants going up a blind alley? Economic migration and life satisfaction around the world: Cross-national evidence from Europe, North America and Australia. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 383–404.

Ray, D. (2006). Aspirations, poverty, and economic change. Understanding Poverty, pp. 409–421.

Safi, M. (2010). Immigrants’ life satisfaction in Europe: Between assimilation and discrimination. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 159–176.

Salvatore, D. (1981). A theoretical and empirical evaluation and extension of the Todaro migration model. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 11(4), 499–508.

Schultz, T. P. (1982). Notes on the estimation of migration decision functions Migration and the Labor Market in Developing Countries. Sabot, Boulder: Westview Press.

Stillman, S., Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., & Rohorua, H. (2015). Miserable migrants? Natural experiment evidence on international migration and objective and subjective well-being. World Development, 65, 79–93.

Stillman, S., McKenzie, D., & Gibson, J. (2009). Migration and mental health: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of health economics, 28(3), 677–687.

Tunali, I. (2000). Rationality of migration. International Economic Review, 41(4), 893–920.

UN Habitat. (2013). State of the world’s cities 2012/2013: Prosperity of cities. Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, S.S. Aspirations of Migrants and Returns to Human Capital Investment. Soc Indic Res 138, 317–334 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1649-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1649-6