Abstract

The success and expansion of the International Comparison Program (ICP) has led to an increase in interest and effort on the estimation of sub-national price levels and purchasing power parities (PPPs). The ICP highlighted a difficulty that large countries such as Brazil, Russia, India and China face during the price-collection phase, namely how to obtain average prices when there are large disparities in many types of expenditure categories, such as housing prices between rural and urban settings. The fact that such disparities were in evidence led to more research on within-country PPPs, or regional price parities (RPPs). The difference between a RPP and the PPPs is simply that the former are in the same currency, while PPPs are usually converted to a reference country or currency by the exchange rate, such as the United States Dollar or the Euro. This paper describes the methodology used to estimate the RPPs within the United States, and shows their effect on measures of income adjusted to constant dollars, termed real regional incomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The CPI microdata are available to us through an interagency agreement, between the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and BEA, while the rent data are also microdata but closely match those from the PUMS (Public Use Microdata Sample) of the Census Bureau.

Publications describing these results may be found at www.bea.gov/research/topics/regional.htm.

The 38 CPI index areas are designed to represent the U.S. urban and metropolitan population. Of the 38 areas, 31 represent large metropolitan areas, 4 represent small metropolitan regions, and 3 represent urban nonmetropolitan regions. For more information on these BLS-defined areas, see www.bls.gov/cpi. A list of the counties sampled in each area can be found in Aten (2005).

Expenditure weights used in the CPI are known as cost weights, and are derived from BLS Consumer Expenditure (CE) survey data. See the “Consumer Price Index” in the BLS Handbook of Methods, Chapter 17 at www.bls.gov.

For a description of input data and methods used to estimate RPP expenditure weights, see Figueroa, Aten and Martin (2014).

See the “Consumer Price Index,” in the BLS Handbook of Methods, chapter 17 at www.bls.gov.

The Geary formula is solved simultaneously for the area RPPs and the expenditure class price levels (notation and formulas follow Deaton and Heston 2010).

We can also estimate an overall PGeary for each of the 38 areas, but only the more disaggregate indexes are used in the second stage.

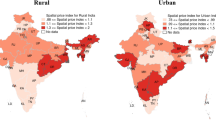

Price levels in rural counties in the South, Midwest and West regions are assumed to be the same as those in the BLS urban, nonmetropolitan area for the region. BLS has no urban, nonmetropolitan area for the Northeast so rural counties are assumed to have the same price levels as those in the BLS-defined small, metropolitan area for the Northeast.

They are derived from the bi-annual Consumer Expenditure survey (CE) but are modified to be consistent with the CPI, and are called Cost Weights.

The allocation uses county-level ACS Money Income. Money income is defined as income received on a regular basis (exclusive of certain money receipts such as capital gains) before payments for personal income taxes, social security, union dues, Medicare deductions, etc. Therefore, money income does not reflect the fact that some families receive part of their income in the form of noncash benefits. For more information, see www.census.bov. In past papers, population was used to distribute the weights; for a comparison, see Figueroa et al. (2014).

Unit rents are the sum of rent expenditures divided by the number of units of each housing type for each area.

For more information on how the RPP program estimates expenditures on owner-occupied rents, see Figueroa et al. (2014).

The adjustment is based on BLS research providing PCE-valued weights for CPI item strata (Blair 2012).

The weighted geometric means are the least squares marginal means across the 5 years, obtained using a weighted CPD with a dummy variable for the year.

Beginning in November 2015, the three-year MSA files will no longer be available from the Census.

In Aten and D’Souza (2008), the imputation for county-level owner-occupied rent levels used owner’s monthly housing cost data from the 5-year ACS housing file, together with the annual CPI Housing Survey from BLS. In more current work (Aten et al. 2011, 2012), only observed price levels from the ACS were used, making no imputations for the owner-occupied rent levels. The monthly housing costs in the ACS include mortgage payments, but do not specify the term or interest rate of the loan. The coverage and distribution of the reported payments was highly variable, and using that information has been postponed until more data or further research is completed.

ACS data for 2012 did not incorporate a revision made by BEA to its MSA definitions (see Survey of Current Business, “Comprehensive Revision of Local Area Personal Income”, December 2013, page 17.) Among other changes, the revision designated 23 new MSAs. ACS rents for these MSAs were estimated from ACS data for state metropolitan and nonmetropolitan portions. These revisions have now been included in all the estimates going back to 2008.

The rent observations are the “Contract Rents” in the ACS.

Personal income is defined as the income received by all persons from all sources. It is the sum of net earnings by place of residence, property income, and personal current transfer receipts. This article uses personal income estimates released by BEA’s Regional Income Division on September 30, 2014. For more information, see www.bea.gov/regional.

50 states and the District of Columbia (hereafter referred to as “states”).

www.bea.gov/regional under Data: Real Personal Income and RPPs.

The main reason for using five-year averages of CPI price levels is for consistency and robustness of the estimates. In some cases, the number of observations for which we can obtain overlap across characteristics and item definition is small. Pooling the data was found to be an effective way to control for sparseness in the geographic coverage for the purposes of the RPPs (see Aten and Marshall 2010).

See FAQs, in the Handbook of Methods, http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpifaq.htm#Question_6.

The full tables are available on the web at www.bea.gov. See box titled “Data Availability” on how to access the data.

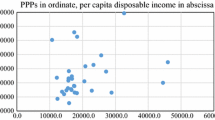

The leftward shift along the horizontal axis is equal to the difference between U.S. nominal ($44,765) and real (2009 dollars, $41,706) per capita totals for 2013, and reflects the 7.3 % increase in the U.S. PCE price index between 2013 and 2009.

References

Arndt, H. W., & Sundrum, R. M. (1975). Regional price disparities. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 11(2), 30–68.

Aten, B. H., (1999). Cities in Brazil: An interarea price comparison. In A. Heston & R. Lipsey ()Eds. International and interarea comparisons of income, output, and prices. National Bureau of Economic Research, studies in income and wealth volume 61. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Aten, B. (2005), Report on interarea price levels, 2003, working paper 2005–11, Bureau of Economic Analysis, May. http://bea.gov/papers/working_papers.htm.

Aten, B. (2006). Interarea price levels: an experimental methodology. Monthly Labor Review, 129, 47. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington, DC.

Aten, B. (2008). Estimates of state and metropolitan price parities for consumption goods and services in the United States, 2005. Bureau of Economic Analysis, April. http://bea.gov/papers.

Aten, B. H., & D’Souza, R. J. (2008). Regional price parities: Comparing price level differences across geographic areas. Survey of current business, 88(11), 64–74.

Aten, B. H., & Figueroa, E. B. (2014). Real personal income and regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2008–2012. Survey of Current Business, 94(6), 1–8.

Aten, B. H., & Figueroa, E. B., (2015). Real personal income and regional price parities for state and metropolitan areas, 2009–2013. Survey of Current Business, 95(7), 1–4.

Aten, B., Figueroa, E., Martin, T. (2011). Notes on estimating the multi-year regional price parities by 16 expenditure categories: 2005–2009. Bureau of Economic Analysis, April. http://bea.gov/papers.

Aten, B. H., Figueroa, E. B., & Martin, T. M. (2012). Regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2006–2010. Survey of Current Business, 92(8), 229–242.

Aten, B. H., Figueroa, E. B., & Martin, T. M. (2013). Real personal income and regional price parities for states and metropolitan areas, 2007–2011. Survey of Current Business, 93, 89–103.

Aten, B., & Reinsdorf, M. (2010). Comparing the consistency of price parities for regions of the U.S. in an economic approach framework. In 31st general conference of the international association for research in income and wealth, August. http://www.bea.gov/papers.

Balk, B. (2009). Aggregation methods in international comparisons: An evaluation. In D. S. Prasada Rao (Ed.), Purchasing power parities of currencies, recent advances in methods and applications. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Biggeri, L., & Laureti, T. (2009). Are integration and compariosn between CPIs and PPPs feasible? In L. Biggeri & G. Ferrari (Eds.), Price indices in time and space. New York: Springer.

Biggeri, L., & Laureti, T. (2015). Sub-national PPPs: Methodology and application by using CPI data. Paper presented at the workshop on inter-country and intra-country comparisons of prices & standards of living, Arezzo, Italy, September 2014. www.polo-uniar.it.

Blair, C. (2012). Constructing a PCE-weighted consumer price index. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper (March). www.nber.org.

BLS Handbook of Methods. (2011). Bureau of labor statistics. http://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/homtoc.htm.

Citro, C. F., & Kalton, G. (Eds.). (2000). Small-area income and poverty estimates: Priorities for 2000 and beyond. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Deaton, A. (2003). Prices and poverty in India, 1987–2000. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(4), 362–368.

Deaton, A. (2006). Purchasing power parity exchange rates for the poor: Using household surveys to construct Ppps, research program in development studies. Princeton: Princeton University.

Deaton, A., & Heston, A. (2010). Understanding PPPs and PPP-based national accounts. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(4), 1–35.

Deaton, A., & Oupriez, O. (2011). Spatial price differences within large countries. Research program in development studies, Princeton University and World Bank working paper.

Deaton, A, & Tarozzi, A. (2005), Prices and poverty in India. In A. Deaton & V. Kozel (Eds.), The great Indian poverty debate. New Delhi: MacMillan.

Diewert, W. E. (1999). Axiomatic and economic approaches to international comparisons. In A. Heston & R. Lipsey (Eds.), International and interarea comparisons of income, output, and prices, National Bureau of Economic Research, studies in income and wealth (Vol. 61). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Diewert, W. E. (2005). Weighted country product dummy variable regressions and index number formulae. Review of Income and Wealth, Series, 51–4, 561–569.

Fenwick, D., & O’Donoghue, J. (2003). Developing estimates of relative regional consumer price levels. Economic Trends, 599, 72–83.

Figueroa, E., Aten, B., & Martin, T. (2014). Expenditure weights in the regional price parities. Bureau of Economic Analysis, May. http://bea.gov/papers.

Garner, T., & Short, K. (2009). Accounting for owner-occupied dwelling services: Aggregates and distributions. Journal of Housing Economics, 18, 233–248.

Koo, J., Phillips, K. R., & Sigalla, F. D. (2000). Measuring regional cost of living. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 18(1), 127–136.

Kravis, I. B., Heston, A., & Summers, R. (1982). World Product and Income, International comparisons of real gross product. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Martin, T., Aten, B., & Figueroa, E. (2011). Estimating the price of rents in regional price parities. Bureau of Economic Analysis, October. http://bea.gov/papers.

McCarthy, P. (2010). Asia and pacific region, sub-national purchasing power parities—Case study for the Philippines. Paper presented at the 2nd ICP technical advisory group meeting, Washington DC, February 17–19.

OECD/Eurostat. (2012). Eurostat-OECD methodological manual on purchasing power parities. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Orshansky, M. (1969). How poverty is measured. Monthly Labor Review, 92, 37.

Poole, R., Ptacek, F. & Verbrugge, R. (2005). Treatment of owner-occupied housing in the CPI. Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/bls/fesacp1120905.pdf.

Rao, D. S. (2005). On the equivalence of weighted country-product-dummy (CPD) method and the Rao-system for multilateral price comparisons. Review of Income and Wealth, 51(4), 571–580.

Renwick, T. (2011). Geographic adjustments of supplemental poverty measure thresholds: using the American community survey five-year data on housing costs, working paper U.S. Census Bureau, January.

Roos, Michael. (2006). Regional price levels in Germany. Applied Economics, 38(13), 1553–1566.

Sergeev, S. (2004). The use of weights within the CPD and EKS methods at the basic heading level. Working paper, Statistics Austria.

Short, K. (2015). The supplemental poverty measure: 2014”, report number P60-254, Census Bureau, September.

Short, K., & O’Hara, A. (2008). Valuing housing in measures of household and family economic well-being, Annual meeting of the allied social sciences associations, society of government economists, New Orleans, January.

Summers, R. (1973). International price comparisons based upon incomplete data. The Review of Income and Wealth, 19(1), 1–16.

Waschka, A., Milne, W., Khoo, J., Quirey, T., & Zhao, S. (2003). Comparing living costs in australian capital cities. A progress report on developing experimental spatial price indexes for Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Wingfield, D., Fenwick, D., & Smith, K. (2005). Relative regional consumer price levels in 2004. Economic Trends, 615, 36–46.

World Bank. (2015). Purchasing power parities and the real size of world economies. A comprehensive report of the 2011 international comparison program (ICP). The International Bank for reconstruction and development/The World Bank.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Eric Figueroa to the development and preparation of the RPPs. This work would not be possible without the collaboration of the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau. In particular, we thank the staff of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) program in the Office of Prices and Living Conditions at BLS and the staff of the Social, Economic and Housing Statistics Division of the Census Bureau for their technical and programmatic assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimer:The BEA Regional Price Parity statistics are based in part on restricted access Consumer Price Index data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The BEA statistics expressed herein are products of BEA and not BLS.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aten, B.H. Regional Price Parities and Real Regional Income for the United States. Soc Indic Res 131, 123–143 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1216-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1216-y