Abstract

This paper discusses the creation and use of the new Macquarie Laws of War Corpus (MQLWC). The corpus consists of the 110 documents of international war law stored in the International Committee of the Red Cross treaties database, starting with the 1856 Declaration Respecting Maritime Law (Paris Declaration) and ending with the most recent amendment to the Rome Statute (2019). The new MQLWC is hosted at the Sydney Corpus Lab (sydneycorpuslab.com), via its CQWeb interface, which allows for searching of frequencies, concordance lines, and collocations. The corpus can also be downloaded for offline processing in other popular concordance programs, such as #Lancsbox and AntConc. This paper introduces the corpus, describes the process of assembling the data, and explains its limitations. The paper then demonstrates some of the ways the data can be explored using the concept of 'military necessity'. The MQLWC contributes to the growing use of corpus linguistics in legal studies, and will be of particular relevance to scholars in the field of international war law.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper introduces the new Macquarie Laws of War Corpus, or MQLWC. The term 'Laws of War', also known as the 'Law of Armed Conflict' (LOAC) and 'International Humanitarian Law' (IHL) [8], refers to a body of international treaties and documents written in principle to regulate the use of force in international and non-international armed conflicts, although, as discussed below, the history and function of this body of law is very much contested. The MQLWC encompasses the documents held in a treaties database by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The ICRC maintains its IHL Treaties database as one of two sources of international war law: the second is a database of customary international law. The provision of information about legal frameworks for the regulation of international conflict is central to the ICRC's commitment to "prevent suffering by promoting and strengthening humanitarian law and universal humanitarian principles",Footnote 1 which includes a role in "reminding authorities of their legal obligations under international humanitarian law and international human rights law".Footnote 2 The ICRC maintains this IHL Treaties databaseFootnote 3 as part of its mission, and this corpus consists of all text documents hosted in this database (except for one text—see below).

The Macquarie Laws of War Corpus provides new potential for conducting research into this extremely significant body of international law. While previously an "esoteric area of international law"—the preserve of the ICRC, military lawyers and a small number of academics—the field of international war law is now mainstream [22]. The factors for this transformation are argued to include changes in media reporting of war, the pervasiveness of smartphones, and the proliferation of international tribunals and courts which have "raised global expectations that those responsible for atrocities should be held accountable" [22]. Currently the texts constituting this body of law are available at the ICRC website only as a set of separate documents. They can be opened as pdf documents, or accessed on the website, where often their content is distributed across a number of links, based on text segments such as Articles of the text. This display prevents even searching for a single term across one text. These modes of access allow only for the most minimal of engagement with these significant documents. The recent addition of an 'advanced search' function to the database enables users to locate words and phrases in texts, but does not offer the advanced functionality of standard corpus linguistic tools.

With the growing interest in international war law have come debates about the history and function of the laws of war, with some scholars rejecting “the standard Western-European-centric view” characterized by the “grand narrative of international law as the purveyor of peace and civilization to the whole world” [21]. Critical accounts of international war law argue that this body of law in its various forms does not constrain the use of violence, but rather is a crucial source of its legitimation [20, 24, 26, 28]. Mégret for instance argues that treaties, statutes and customary war law sources "enable, constitute and perpetuate" war and have produced “the basic building blocks of the international grammar of violence” [26]. Jochnick and Normand [20] argue that the laws of war have in fact “facilitated rather than restrained wartime violence”. At the very least, the development of this body of legal text has produced many "unintended consequences" [11], suggesting the need to study these texts as a form of public discourse beyond whatever claims might be made for their legal potential to constrain the use of geopolitical violence.

How do one and the same texts afford such profoundly distinct interpretations? While legal analysis and debate offer one means to consider this paradox, the gaze from linguistics is indispensable for a question of this kind. As Goodrich notes, "legal discourse, like any other of the traditional rhetorical genres or language varieties, is an historically and rhetorically organised product"; as such, it can be subjected to a "critical linguistic methodology" which allows scholars to "read within the structure of legal discourse the socio-historical and political affinities and conflicts that led to the emergence of the myth of law as a unitary language and as a discrete scientific discipline" [12]. While legal texts operate in highly specialized contexts of interaction, in which those with the authority to invoke the meanings of these texts require specialized training, the texts themselves are products of the same linguistic systems on which all other interactions by speakers of the same language depend. Legal texts, as such, are subject to the same semiotic principles as any ordinary use of language. These principles include “the arbitrariness of the sign” [10], that is, the principle that linguistic signs are the unity of a concept and an acoustic image. Any potential sound can be recruited to be the expression of any meaning that humans can dream up. In addition, legal texts like any other linguistic text are the product of lexicogrammatical choices. Any word or phrase within such texts operates within multifunctional paradigms of structures which are essential to the ways these texts make meanings [18]. Finally, these texts, like all acts of meaning, have their own institutional and social–historical contexts [15]. All these features of language give it its enormous plasticity, and therefore, its ideological potential [23]. The theories and methods in linguistics which enable the study of texts of all kinds have much to offer the study of legal discourse.

The focus of this paper is to introduce the MQLWC and to demonstrate the value of corpus linguistic techniques for the study of the laws of war. Corpus linguistic methods have already begun to have a role in the study of legal discourse (see e.g. [13, 29, 30, 32]). Given the significance and indeed the growing interest in this field of international war law, the texts which are its foundation are overdue for the kind of textual study that is made possible when converted into a searchable linguistic corpus. By turning these discrete documents into a fully searchable corpus, the contest of interpretation over the efficacy of these texts will have access to new forms of evidence and argumentation made available by the standard techniques of corpus linguistics, including word frequencies, concordance patterns, and collocations. Not only does the transformation of the documents into a corpus open them up to the methods of inquiry made available by corpus linguistics, they become more readily subject to study through a variety of linguistic methods.

Corpus linguistic techniques enable researchers to efficiently search a large volume of data for a variety of linguistic patterns. With this research infrastructure, it becomes possible to determine the presence, frequency and distribution of words and phrases, as well as the typical collocation patterns of some key lexical node, within a given body of texts. In the case of the MQLWC, the corpus is not simply a representative sample of this domain: it consists of all possible texts in this field. When available in this form, reseachers can approach this corpus from both so-called corpus-driven and corpus-based or corpus-assisted methods [25]. From the perspective of corpus-driven approachesFootnote 4—where researchers use standard techniques to search a body of texts and allow the findings to drive analysis and interpretation—it is now possible to describe a range of features of this body of law text, such as it size, and its dominant as well as its less frequent lexical patterns. From a corpus-assisted perspective, corpus methods allow a researcher to search for predefined lexicogrammatical patterns of interest to determine their frequency and distribution within international war law, with a view to testing claims about the meaningful patterns in the laws of war. Naturally, corpus-assisted methods combine well with other forms of manual text or discourse analysis which enable a deeper inquiry into linguistic patterns, though always at the cost of the scale of analysis which can be conducted. Lukin (2019) exemplifies how small scale detailed text analysis can combine with standard corpus techniques in the study of ideology, in this case ideologies around war and violence.

2 Creating the Macquarie Laws of War Corpus (MQLWC)

To construct this corpus, we first downloaded all documents archived by the ICRC from the IHL Treaties database, with the exception of a small set of texts which were directly available in plain text format via Wikisource (see “Appendix” for a full list of the documents in the corpus). All documents downloaded from the ICRC site were in pdf format, and they varied in type and in formatting. Some were not searchable. A shell script was used for converting the documents into a searchable txt format, and metadata from within the documents was removed using regular expressions in the text editor Notepad++. The files were edited where necessary to include only the text of the treaty or document: headings, tables of contents, and page numbers were removed.

The documents are organised by the ICRC by the following categories: date, topic, and by state (listing which conventions have been signed/ratified by each state). We retained the categories of date and topic. While the details of which states are parties to which convention is important, we decided that it was too difficult to implement this category. In addition, these documents are tagged by the ICRC with the following themes, which we also retained in the development of this corpus: 'victims of armed conflict', 'methods and means of warfare', 'naval and airwarfare', 'cultural property', 'criminal repression', and 'other treaties relating to IHL'. The database also includes a set of texts labelled 'historical treaties and documents': these are documents that are either no longer in force or are historically significant but which have never functioned as an international agreement, for example, the Leiber Code, described as the "earliest official government codification of the laws of war" [7]. In putting this corpus together, we decided that all these documents should be included for the role they have played in the development of accepted norms and principles of the laws of war. The Leiber Code, for instance, creates the concept of 'military necessity' [7] which remains a current principle in international war law (see below).

The corpus was then tagged to be suitable for the CQPweb interface, a software interface that underpins a number of widely used corpora, such as the British National Corpus (BNC). CQPweb (where CQP stands for Corpus Query Processor) is a 'fourth generation' corpus linguistics software system, providing usability (including for researchers with minimal or no programming skills), power and flexibility to maximise the potential of corpus data to be studied through corpus methods [19, 25]. For example, word frequencies within the corpus can be measured, both as a raw number and as a normalised frequency to enable comparison with other data sets (by default set at words per million or wpm). Concordance lines i.e. a line of text in which a keyword appears, can be retrieved, allowing for a researcher to examine words or phrases in their immediate context. In addition, the system can generate the collocates of a key word or phrase, that is, the typical words that co-occur with the word or phrase under study, with a variety of statistical measures of collocation available to the user.

To prepare the documents for upload to CQPweb, the data was lemmatized (i.e. lexical items from the same word stem were grouped together regardless of their inflectional forms) and tagged with part of speech and semantic categories using the following tagsets: CLAWS 6 part-of-speech tagger, Simple POS (using Oxford Simplified Tagset), USAS (UCREL Semantic Analysis System),Footnote 5 and Simplified USAS. It was then uploaded into the CQPweb interface. The corpus is also available from this same location to be downloaded for offline processing by selecting "export corpus" from the sidebar menu. This allows the data to be analysed with widely used desktop programs such as #Lancsbox [5] or AntConc [2].

3 Overview of the Corpus

At the time of publication, the ICRC treaties database contained 111 documents. As one of these documents consists only of an image of an identity card to be carried by journalists (Annex II to Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions), it was excluded, leaving a total of 110 documents in the corpus. The size of a corpus is typically measured through a count of tokens, although there is no standardized definition for the category of token. The variation in the protocols for counting tokens in a corpus includes decisions relating to punctuation, clitics (e.g. contractions such as "can't", or "she'll"), and multi-word expressions [6]. The token count of the MQLWC in CQPweb is nearly 392 K, as punctuation items are included as tokens. The number of types—unique words or character clusters—is 8557 (giving a type/token ratio of 0.022). When tokens are counted in a tool that ignores punctuation, such as #Lancsbox [5], the corpus is roughly 10% smaller, with a token count of around 355 K, and a slightly reduced type count of 8513 (producing a type to token ratio of 0.024). The variation in tokenization principles across these widely used systems is a reminder that all units in linguistics are derivative.

Despite the variation in these counts, it is now possible to estimate the size of the body of documents constituting this field of law. Taking for example the #Lancsbox calculation, we can now determine that over a period of 165 years of recognised treaty-making processes, states have produced around 355,000 words purportedly with the purpose of attempting to limit the use of violence in international and non-international armed conflict.

The CQPweb user interface provides various options for searching the data: word frequencies, collocations, standard whole-of-corpus and restricted queries based on internal parameters of the corpus. In the case of MQLWC, these include the ICRC categories, and the distinction between treaties still currently in force, versus those which have lapsed or which have no legal hold. This means words or phrases can be searched across the whole data set, or in a subset of the data based on identified sub-categories such as 'victims of armed conflict', or 'criminal repression'.

As mentioned, the corpus includes all texts identified by the ICRC as falling within the scope of International Humanitarian Law. Each of these texts has played its unique role in the development of this field of law. Hence, it was decided that text IDs needed to readily identify each document, including its place in the timeframe from the first treaty document in 1856 to the most recent text at the time of writing (the 2019 amendment to the Rome Statute). Therefore, text IDs begin with the year of adoption (or where the text was never formally adopted, its year of publication), combined with the document's official name, abbreviated in some cases to give only the information necessary to identify the document. For example, the 2006 Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance has the text ID "2006_ConventionProtectionEnforcedDisappearance".

4 Limitations

The main limitation of the MQLWC corpus is that it consists only of English documents. With a few exceptions, all documents from the 1856 Paris Declaration until the 1935 Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments (Roerich Pact) were in French only, which means the documents in this corpus from this period are translations of original legal texts. Apart from the 1863 Leiber Code, English was first added as a second language in a 1922 treaty (the Washington Treaty relating to the Use of Submarines and Noxious Gases). From 1935 onwards, with occasional exceptions, English has been a recognised language for treaty documents, with Spanish (from 1935), Russian (from 1945), Chinese (from 1946) and Arabic (from 1978) gradually added as official languages.Footnote 6 The monolingual nature of this corpus is a clear limitation. In addition, the corpus confines itself to one source of the laws of war. There are other sources of international war law, such as army manuals and case law. Such texts are not included in the corpus, but they should be considered for a future, larger corpus of documents in the field of international war law.

5 Using the Corpus for Research

Hosted at the Sydney Corpus Lab (sydneycorpuslab.com), this dataset is now available to any researcher interested in patterns of meaning in the international laws of war and it is our hope that the corpus will enable collaborations between linguists and scholars of international war law. We offer a brief example here of how the corpus and some corpus techniques might be used to consider the argument that these laws create an entitlement to the use of violence by the states who are party to them. This has been argued for instance in Jochnick and Normand [20] who "challenge[] the notion that the laws of war serve to restrain or 'humanize' war" arguing they have instead been "formulated deliberately to privilege military necessity at the cost of humanitarian values" [20]. As a consequence, they argue, these laws facilitate rather than restrain violence, and provide it with the very valuable semiotic commodity of legitimacy [20].

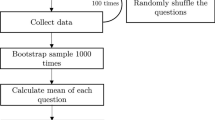

Given this claim, what can this corpus reveal on the question of whether the laws of war privilege military necessity at the cost of humanitarian values? A full response to this question is beyond the scope of this paper, and requires analysis over and beyond that offered by corpus linguistics—see for instance Lukin [24] for an analysis of the lexicogrammatical structures in the definition of “war crimes” in the Rome Statute,Footnote 7 including a discussion of the grammar that enables an unequivocal rejection of belligerent technology (the use of chemical weapons) compared with the grammar which defends the use of other lethal technologies. But here we set out some examples of how the corpus could be used to provide empirical evidence pertaining to a question of this kind. We briefly explore the presence of the concept ‘military necessity’ in the corpus, and begin to describe the semantic landscape in which this very powerful concept comes into being and through which it is sustained. A first simple step in this process is to calibrate the frequency of the term 'military necessity' in international war law via the MQLWC. With the new corpus available through this interface, we queried the corpus and retrieved a total of 43 instances of the term 'military necessity', in 20 of the 110 texts in the corpus, beginning with the 1863 Leiber Code and ending with the 2010 amendment to Article 8 of the Rome Statute.

At first glance the instances of this term do not seem particularly numerous: a frequency of 43 would give this term a rank in the late 900 s in this corpus. But a raw frequency of 43 instances in this corpus translates into a relative frequency of 109 words per million (wpm). By comparison, the frequency of 'military necessity' in the BNC is 0.07 wpm (and the concordance lines show fewer than half of the usages in the BNC refer to 'military necessity' as a principle). Google's Ngram Viewer [27] shows the peaks of the use of this concept in its books corpus as 1864, 1917, and 1944 (see Fig. 1)—the American Civil War and the First and Second World Wars. The highest peak is 1944, where the figure is 0.0007165 per hundred (the standard reporting metric of the Google Books Ngram Viewer), or 7 wpm. The News of the Web corpus [9], a corpus of English news text collected from 1/1/2010 until the present from 20 countries, contains 451 instances across its 13.8 billion words, which translates into a normalised frequency of around 0.0033 words per million (search conducted on 23/11/21). In the context of international war law, the mere 43 instances constitute a very high frequency for this concept.

It perhaps seems an obvious finding that the concept of 'military necessity' would be more frequent in this corpus than in other comparison corpora. But what this finding confirms is that the term is register-specific [3, 17]. It was born out of, and resides within, highly specialized and highly abstract discourse. That 'military necessity' lives in this register confirms its character as an abstract legal principle, one that requires the highly elaborated semiotic edifice of legal discourse to survive. When its legal role is to defend actions that, without the cover of this principle could be classified as 'war crimes', it is almost breathtaking to understand the fundamentally derivative character on this concept. It is, as Halliday describes, a “construct of virtual reality”, that is, of “a semiotic alternative universe” [16] being crucially at a distance from the material events to which it can become attached. An observer ‘on the ground’ cannot, with the naked eye, determine whether acts of violence are ‘war crimes’ or are permissible under ‘military necessity’—only legal argumentation can make such determinations.

To treat the texts on international war law as a linguistic corpus arguably enables researchers and practitioners to 'deautomatize' [31] these weighty legal principles. For example, 'military necessity' is a simple collocation of two terms. 'Necessity' is a noun, and 'military' functions as classifying adjective premodifying 'necessity' [14]. Thus, the conjunction of these lexical items creates a subtype of 'necessity', that of the 'military' kind. By such a simple grammatical act, a powerful binding legal concept was manufactured, but only through the force of the kind of texts in which it has been created and reiterated.

Given the importance of the semantic environment of this concept, other insistent features of this data are likely to assist in understanding the power and plausibility of this principle. Table 1 sets out the top 20 most frequent lexical items in the corpus (with closed system grammatical items filtered out). Many of the higher-ranked items in this list are references to key participants in the treaties (Parties, Party, state/s), or to the documents or aspects of the document (Convention, article, and 'present', which almost entirely appears for deictic purposes, e.g. "the present convention/article/statute/protocol"). If we set aside references to the key participants and documents, the word 'military' now sits in the top five lexical items of the corpus. Its normalised frequency is 2111 wpm. For the sake of comparison, in the BNC 'military' has a frequency of 114 wpm: the term 'military' is 18 times more frequent in the MQLWC. This corpus is, therefore, a key semiotic environment for creating or reinforcing the meanings of 'military', including its collocation with 'necessity', providing further evidence for the register-specific nature of this concept.

Table 2 shows the top 20 collocates of 'military'. Following Brezina et al. [4], the collocation parameter notation for this set of collocates is: MI3(9), R5-L5, C5-NC5, closed system items removed (where 'closed system' means those belonging to grammatical paradigms, see Halliday and Matthiessen [14]. In other words, the collocates are based on a window of five words to the left and right of ‘military’, with a minimum requirement of five instances of each collocate and of their collocation with ‘military’, adopting the collocation measure Mutual Information 3, which combines both mutuality and frequency [4]. Following these parameters, 'necessity' ranks as the third highest collocate of 'military'. Of the 88 instances of ‘necessity’, very nearly 50% combine with 'military'. From the perspective of 'necessity', 'military' is the number 1 collocate. Thus it is not simply that 'military' attracts 'necessity', but that in this context, 'necessity' attracts the word 'military'. Other collocates of 'military' reveal close synonyms of 'military necessity', such as 'advantage', 'considerations' and 'imperative'. In addition, the collocates show a deep legitimating semantics around the concept of 'military', including with lexical items like 'objectives', 'operations', 'objective', 'authorities', 'authority', 'permit', and 'purposes'. The environment for the most powerful conjunction of 'military' and 'necessity' is also one in which the military is constructed as organised, authoritative, and purposeful.

Finally, we comment on the potential of concordance lines as a means to more deeply explore the use and dispersion of this term across the corpus. Concordance lines can show us which of the 110 documents use this term (see example concordance lines in Fig. 2; and see Table 3 for a summary of the dispersion of the term across 20 texts in the corpus). This dispersion reveals the longevity of the concept, beginning in 1863 and still present in a 2010 amendment to the Rome Statute: it has lasted nearly 150 years in the laws of war. The 1863 Leiber Code officially launches the concept and so perhaps unsurprisingly has the most number of instances, seven in total (or 16% of the total instances). By reviewing all instances of the term in the corpus, and in particular by reviewing the window to the right of the term, we see that only in the Leiber Code is the term subject to some kind of definition or explanation, including that it "consists in the necessity of …etc. " (3rd line), "admits of all direct destruction of life" (4th line), "does not admit of cruelty" (5th line), "does not include any act of hostility" (6th line). (Fig. 3) No other instance of the term in this corpus includes any further attempt at definition or explanation. It is remarkable that in over 110 documents of international war law, and across some 150 years, this body of texts displays so little interest in the meaning or limits of this profoundly powerful concept.

In addition to the Leiber Code, the term turns up in all four of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, as well as the 1977 Additional Protocol I, the two documents pertaining to the Nuremberg trials, and the statute establishing the tribunal to try war crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia. In addition, one instance is found in a 2010 amendment to the Rome Statute. It also appears in documents such as the 1880 Oxford Laws of War on Language and the 1909 London Declaration on the Laws of Naval War. In terms of the distinction between so-called "Hague law" (law regulating how war/violence is used by states) and "Geneva law" (law regulating the treatment of victims of war) (see e.g. [8]), the concept moves easily between both fields of war law. Perhaps also noteworthy is that another significant document for this concept is the 1977 Additional Protocol 1, with its focus on "provisions protecting the victims of armed conflicts". In a paper arguing against US ratification of this protocol, Major Guy Roberts claims the 1977 Additional Protocol 1 was "an attempt to shift the balance established between military necessity and humanitarian principles in such a way as to hamper the ability of states to use military force to attain political objectives" (cited in [1])—yet nearly 10% of all references to this concept across 150 years of international war law documents turn up in Additional Protocol I.

Above we have presented a few simple analyses that are easily generated once the relevant texts have been formed into a corpus, and some software system is available for their processing. These analyses show the strong presence of 'military' in this corpus, and the mutual attraction between 'military' and 'necessity' here. By comparing the frequency of ‘military necessity’ in this specialized corpus with a variety of other corpora (the BNC, the Google Books Corpus, and the News on the Web corpus), we have shown the register-dependent nature of this concept—it was created and has been perpetuated largely through this body of international law, suggesting that international war law plays a fundamental role in legalizing geopolitical violence. In addition, we have reported the longevity of the concept across nearly 150 years of international law and shown the various related collocations that all work to legitimize the place of the military in this discourse, as well as to reiterate the principle of 'military necessity' through other wording. We anticipate the corpus will be a basis for deeper linguistic work on this field of law and will create improved opportunities for interdisciplinary work on the role of legal discourse in relation to war and violence.

6 Conclusion

This paper has introduced the MQLWC and explored how simple corpus linguistic methods can reveal important dimensions of meaning in this data. These methods have been used within a corpus-assisted approach—that is, they have to used to explore the data with a question already in mind, namely, the place of ‘military necessity’ in this body of law. The question was derived from critical analyses of standard claims about the rise and function of international war law [20, 24, 26, 28]. This is one of many questions which could be brought to this data, including, for instance, how the texts of international war law construct the category ‘civilian’, how gender operates within international war law, or how some kinds of belligerent technologies are proscribed, while others are allowed explicitly or implicitly to become a naturalized part of geopolitical violence. Even with these simple techniques, important semiotic patterns in this data can be elucidated. Corpus methods alone have their limitations—word frequencies and collocations can appear unmotivated or disconnected from the institutional work that texts of this kind perform. But when combined with an understanding of the political and historical context of these texts, and with a linguistic account of the role of language in legal contexts, corpus tools and methods are invaluable. The potential to study these significant legal documents with the power of linguistics, including corpus linguistics, is well overdue.

Notes

Like McEnery and Hardie (McEnery and Hardie, 2012) we reject the assumptions of corpus-driven approaches, namely that the corpus itself can set the terms of the inquiry.

Full list of categories can be found here: http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/usas/semtags_subcategories.txt.

Portuguese was an official language of a single document, the 1935 Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments (Roerich Pact).

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, done at Rome 17 July 1998; in force 1 July 2002; 2187 UN Treaty Series 90.

References

Alexander, A. 2015. A short history of international humanitarian law. European Journal of International Law 26 (1): 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chv002.

Anthony, L. 2020. AntConc (Version 3.5.9) [Computer Software]. Retrieved 9 Nov 2021. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software.

Biber, D., and S. Conrad. 2009. Register, genre and style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brezina, V., T. McEnery, and S. Wattam. 2015. Collocations in context: A new perspective on collocation networks. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 20 (2): 139–173. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.20.2.01bre.

Brezina, V., P. Weill-Tessier, and A. McEnery. 2020. #LancsBox v. 5.x. [software]. Retrieved 9 Nov 2021. http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/lancsbox.

Brezina, V., and M. Timperley. 2017. How large is the BNC? A proposal for standarised tokenisation and word counting. Paper presented at International Corpus Linguistics Conference. University of Birmingham.

Carnahan, B.M. 1998. Lincoln, Lieber and the laws of war: The origins and limits of the principle of military necessity. The American Journal of International Law 92 (2): 213–231. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998030.

Crawford, E., and A. Pert. 2015. International humanitarian law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, M. 2016. Corpus of News on the Web (NOW). https://www.english-corpora.org/now/. Retrieved 22 Nov 2021.

de Saussure, F. 1974. Course in general linguistics (trans: Baskin, W.). London: Fontana/Collins.

Fazal, T.M. 2018. Wars of law: Unintended consequences in the regulation of armed conflict. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Goodrich, P. 1990. Legal discourse: Studies in linguistics, rhetoric and legal analysis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goźdź-Roszkowski, S. 2021. Corpus linguistics in legal discourse. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 34: 1515–1540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-021-09860-8.

Halliday, M.A.K., and C.M.I.M. Matthiessen. 2014. An introduction to Halliday’s functional grammar: fourth edition, 3rd ed. London: Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K. 1975. Language as social semiotic: Towards a general sociolinguistic theory. Paper presented at International Corpus Linguistics Conference. A. Makkai & V. Becker Makkai. Columbia, SC: Hornbeam Press.

Halliday, M.A.K. 2013. Why do we need to understand about language? In Halliday in the 21st century, ed. J.J. Webster, 71–81. London: Bloomsbury.

Halliday, M.A.K., and R. Hasan. 1985. Language, context and text: Aspects of language in a social semiotic perspective. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Halliday, M.A.K., and C.M.I.M. Matthiessen. 2014. An introduction to functional grammar: Fourth edition, 3rd ed. London: Arnold.

Hardie, A. 2012. CQPweb—combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17 (3): 380–409. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.17.3.04har.

Jochnick, C.A., and R. Normand. 1994. The legitimation of violence: A critical history of the laws of war. Harvard International Law Journal 35 (1): 49–95.

Jouannet, E.T., and A. Peters. 2014. The journal of the history of international law: A forum for new research. Journal of the History of International Law 16: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718050-12340017.

Liivoja, R., and T. McCormack, eds. 2016. Routledge handbook of law of armed conflict. London: Routledge.

Lukin, A. 2019. War and its ideologies: A social-semiotic theory and description. Singapore: Springer.

Lukin, A. 2020. How international law makes violence legal: A case study of the Rome Statute. Language, Context and Text: The Social Semiotics Forum 2 (1): 91–120. https://doi.org/10.1075/langct.00022.luk.

McEnery, A., and A. Hardie. 2012. Corpus linguistics: Method, theory, practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mégret, F. 2016. Theorizing the laws of war. In Oxford handbook on the theory of international law, ed. A. Orford and F. Hoffman. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780198701958.003.0038.

Michel, J.-B., Y.K. Shen, A.P. Aiden, A. Veres, M.K. Gray, The Google Books Team, J.P. Pickett, D. Hoiberg, D. Clancy, P. Norvig, J. Orwant, S. Pinker, M.A. Nowak, and E.L. Aiden. 2011. Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. Science 331: 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199644.

Normand, R., and C.A. Jochnick. 1994. The legitimation of violence: A critical history of the laws of war. Harvard International Law Journal 35 (2): 387–416.

Phillips, J.C., and J. Egbert. 2017. Advancing law and corpus linguistics: Importing principles and practices from survey and context analysis methodologies to improve corpus design and analysis. BYU Law Review 6: 1589–1620.

Potts, A., and A.L. Kjær. 2016. Constructing achievement in the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY): A corpus-based critical discourse analysis. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 29: 525–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-015-9440-y.

Shklovsky, V. 1965. Art as technique. In Russian formalist criticism: Four essays, ed. L.T. Lemon and M.J. Reis, 3–24. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Solan, L.M. 2020. Corpus linguistics as method of legal interpretation. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique 33: 283–298.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no interests financial or otherwise in regards to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lukin, A., Araujo e Castro, R. The Macquarie Laws of War Corpus (MQLWC): Design, Construction and Use. Int J Semiot Law 35, 2167–2186 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-022-09889-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-022-09889-3