Abstract

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT) is the first primary solution to improve urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms, but many challenges stems from certain PFMT-related practices. Exploring PFMT experience will help to increase treatment satisfaction, enjoyment, and empowerment. Hence, the aim of this study was to investigate the experience of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) in Italian people with UI. A qualitative semi-structured interview study was conducted. The interviews’ transcriptions were analysed using a constructionist epistemology lens and adopting the “Reflexive Thematic Analysis”. Sixteen Italian participants (Women N = 10, Men = 6) with UI who experienced PFMT were interviewed. Four themes were generated: (1) ‘Learn to Control the Unconscious Consciously’ as participants learned to control continence through active exercises; (2) ‘Starting PFMT, Changing Mind’ as they realised they can have an active role in managing their condition; (3) ‘Into the unknown intimacy’, as they bridged the gap in their (mis)understanding of the pelvic floor area, overcoming the discomfort linked to intimacy; (4) The Importance of Not Being Alone in this Process’, as the participants emphasised the paramount role of the physiotherapists in the healing process. To conclude, in people with UI, PFMT enhanced pelvic floor knowledge and understanding, fostering awareness, positive mindset, and symptom relief. The physiotherapist's pivotal role as an educator and empathetic guide in exercise programs, along with a preference for active exercises. Overall, our results proved that PFMT has positive consequences in people’s beliefs and mindset about and in the management of UI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common and burdensome issue [1]. Worldwide, 25–45% of women and approximately half of men report some degree of UI [1]. UI can stem from various causes, such as pregnancy, obesity, neurological disorders, and surgical procedures (e.g., prostatectomy) [2, 3]. Symptoms vary considerably depending on the UI type experienced (e.g., stress UI, urgency UI, or mixed UI), including leaks during physical activities like coughing or sneezing, frequent urination, urgent need to urinate, nocturia and feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder [2, 3]. Beyond the anatomical and hygienic implications of UI, it poses psychosocial challenges that affects various aspects of life, including family, work, and recreation [4, 5]. Pizzol et al. [6], in their systematic review with meta-analysis, have affirmed with a strong level of certainty that UI is associated with poor levels of quality of life. Moreover, UI might hinder sexual quality of life because of concerns about potential urine loss during intercourse [7].

The first recommended treatment to improve UI symptoms is pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), usually yielded by a physiotherapist [8, 9] t. PFMT involves progressive exercises targeting muscles crucial for pelvic functions (i.e., continency and sexuality) to improve muscle tone, coordination, and tissue metabolic exchange and vascularisation, thereby maximising individuals’ functional capabilities [10, 11]. Despite PFMT’s proven effectiveness, during this training people may experience challenges stemming from invasiveness of certain PFMT-related practices (i.e., nudity and internal probes) [12], limited ‘bodily’ knowledge of pelvic floor muscles and emotional response like embarrassment [13, 14]. Understanding PFMT experience of people with UI may help to understand their beliefs, preferences, and challenges, ultimately helping identify strategies to increase treatment satisfaction, enjoyment, and empowerment.

Nevertheless, only two studies in Taiwan and New Zealand explored PFMT experiences only in women. These studies underscored PFMT’s value in regaining continence control but also the difficulty in developing awareness of pelvic floor muscles, overcoming initial embarrassment, and adhering to PFMT programme [15, 16]. Therefore, more studies are needed to deepen our understanding of PFMT experience [17, 18]. Notably, no study explored PFMT experience of Italian people with UI. Italy, characterised by a strong pelvic area taboo [19], represents a unique cultural context, potentially yielding insights readily transferable to people with similar cultural backgrounds, particularly in Mediterranean area. Hence, this qualitative study aimed to explore PFMT’s experience in a sample of Italian people with UI.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted an interview qualitative study to understand PFMT’s experience in a sample of Italian people with UI. We adopted semi-structured interviews due to the topic’s sensitivity (i.e., pelvic floor area and related problems in UI), which could have been harder to deal with in focus groups. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for University Research (CERA), University of XX (approval date: XX; XX). The study adhered to ‘Declaration of Helsinki’ and followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) [20].

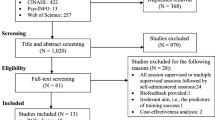

Participants

We recruited participants diagnosed with UI who did PFMT with a physiotherapist for at least one month, through purposive sampling [21]. To reach participants, we contacted Italian physiotherapists working in pelvic floor health to inform their patients about the possibility of participating in our study. Physiotherapists were asked to identify patients who would most likely feel free to talk about their condition and partake in the study. Interested patients were invited to contact BG. We shared the informed consent and the informative note with all physiotherapists and participants to clearly explain the aim of the study. All participants were free to join the research and withdraw from it at any time. No restrictions were applied for gender or primary cause of UI.

Data Collection Method

A group of physiotherapists (BG, OB, MT, and SB) and a psychologist (IC) developed a semi-structured interview guide structured with open questions exploring different topics related to UI and PFMT (Table 1). Participants compiled informed consent forms before interviews, providing demographic data (i.e., age, gender, education, job, marital status, and clinical conditions). These data were registered on an electronic sheet. One-to-one interviews were conducted online by BG through Microsoft Teams from March to December 2022 and lasted approximately 45 min. Videoconferences were recorded and auto-transcribed verbatim. Participants could disable their webcam for comfort. Afterwards, auto-transcription files were corrected (if necessary) and made anonymous, deleting every personal name or detail. After this step, video recordings were eliminated. Participants were assigned codes based on their interview order, age, and gender (e.g., P4, 56y, Man). None of the participants had met the interviewer before. No repeat interviews were conducted.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used for demographic data. Transcriptions were analysed using a constructionist epistemology lens and adopting the “Thematic Analysis” (TA), specifically following Braun’s and Clarke’s ‘Reflexive Thematic Analysis’ (RTA) to identify meaningful patterns in our data [22]. RTA belongs to the ‘Big Q’ qualitative paradigm not adhering to the (post)positivist paradigm characterised by minimising bias, coding accuracy and the use of different strategies (e.g., data saturation and member checking) to increase data trustworthiness [23, 24]. Our approach was predominantly inductive, as we did not impose any predetermined framework. Using an experiential qualitative framework allowed us to look for a reflexed shared meaning among the datasets. We stayed on the explicit or surface meaning of data, so coding was semantic and, when possible, we went beyond the descriptive levels, adopting latent coding [24]. Data analysis followed the six steps of RTA (Supplementary File 1) [23].

Results

Sixteen Italian participants with UI who experienced PFMT agreed to partake in the study (Age (Mean and deviation standard): 57 ± 16, 62.5% Women, N = 10; 37.5% Men N = 6). Among the participants, ten had only UI (62.5%), while remaining six had other comorbidities (37.5%) (See Table 2 for detailed characteristics).

From the analysis of the interviews, four themes were generated: (1) ‘Learn to Control the Unconscious Consciously’, (2) ‘Starting PFMT, Changing Mind’, (3) ‘Into the unknown intimacy’, (4) ‘The Importance of Not Being Alone in this Process’. Quotations and codes that led us generating the themes are reported in Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Theme 1: ‘Learn to Control the Unconscious Consciously’

By exploring participants’ PFMT experience, we noticed the paramount importance of continence control for those with UI, both before and during treatment. Before UI, continence control was an automatic and unconscious function, but when UI occurred, this automatic control was lost. Therefore, PFMT became a tool to learn how to regain continence control through conscious and targeted pelvic floor muscle exercises. Hence, we generated the first theme (Table 3).

Before reacquiring continence control through PFMT, interviewees experienced many negative feelings, such as anxiety, discomfort, fear, embarrassment, rage, and shame. These feelings profoundly impacted their quality of life, restricting their engagement in social and daily activities (e.g., laughing, work, sexual intercourse). Unable to control the losses and negative emotions by themselves from the inside, participants coped with UI, besides medical treatments, by trying to control external factors and modify their life habits. Notably, some reduced their fluid intake when away from home or carried aids or spare clothing.

Upon starting PFMT, participants began to regain control of their loss of urinary function, which was surprising for them. Participants quickly realised how PFMT was effective and essential to reach their expected goals and take control of their daily lives. While exercising, their movement perception, awareness and control of their pelvic floor muscles significantly improved, enhancing physical and psychological well-being and sexual serenity. Ultimately, interviewees mastered urinary control.

To learn how to gain control over unconscious functions, participants preferred active exercises like PFMT over passive treatments. Although adhering to PFMT home schedule posed challenges and occasional guilt, they acknowledged its efficacy in raising a deeper connection with their bodies. Conversely, manual manoeuvres and internal devices were found to be embarrassing, unpleasant, and invasive due to the physical contact with internal and intimate body parts.

Notably, not only did PFMT help interviewees reach their goals, but it also impacted their beliefs and self-management skills, ultimately influencing their mindset, bringing us to generate the second theme, ‘Starting PFMT, Changing Mind’.

Theme 2: ‘Starting PFMT, Changing Mind’

As participants engaged in PFMT, they transformed their perspectives and mindset on their UI condition, developing self-management skills. This transformative process inspired our second theme (Table 4).

Before PFMT, cultural factors heavily influenced participants, making them believe that UI was uncontrollable. Many attributed UI to natural ageing, childbirth, and menopause, considering it a normal life stage. In other cases, some believed surgery-induced UI would improve over time or through general leaflet-recommended pelvic exercises. Eventually, seeking help only commenced when UI impacted relevant aspects of their lives, such as work, sexual activities, or hobbies, when symptoms became unmanageable, or when they realised pelvic exercises were too hard to perform independently.

Once PFMT started, participants felt more engaged in their body and care, understanding their active role in managing their condition. This awareness equipped them with self-management skills, integrating exercises into daily routines and needs. PFMT also empowered them, positively influencing their behaviour and mindset. Some participants reported reduced embarrassment and increased comfort discussing their condition openly. However, starting PFMT occasionally triggered guilt for not initiating treatment sooner or neglecting self-care. Overall, PFMT prompted a positive shift in how participants approached and managed their condition.

Besides positive effects, PFMT brought participants to confront issues related to their pelvic intimacy and the lack of knowledge about pelvic floor anatomy and physiology. This consideration brought us to generate the third theme, ‘Into the unknown intimacy’.

Theme 3: ‘Into the Unknown Intimacy’

Experiencing UI prompted participants to embark on a journey to understand pelvic floor and PFMT while overcoming challenges associated with a condition culturally linked to intimate areas and personal aspects of their lives. This journey is represented by our third theme (Table 5).

Participants’ journey started before PFMT, when they neither had knowledge of pelvic floor anatomy and physiology nor had an expectation about PFMT since they did not properly know what it was. Yet, they were interested in understanding PFMT and its connections with UI. To get this information, participants turned to Internet or sought advice from people who had experienced similar conditions. Engaging with social media platforms helped interviewees connect with health professionals and others with shared experiences, reducing embarrassment linked to intimate areas, empowering, and getting valuable insights into PFMT’s efficacy.

Once they developed a general idea about PFMT, participants sought physiotherapists to start their rehabilitative training. This decision bridged participants' knowledge gap about pelvic floor anatomy and physiology, resulting in surprise, as they realised the potential of pelvic floor muscles in effectively managing UI symptoms. Some participants expressed unawareness of PFMT as a treatment option, underscoring the importance of raising communication about pelvic floor and facilitating direct referrals to PFMT and education through public access channels.

As participants gained a more comprehensive understanding of PFMT’s purpose and mechanisms, their journey presented challenges related to engaging in exercises involving intimate body parts. Throughout their training, participants experienced discomfort, likely influenced by social and cultural factors. They reported difficulty finding private moments for exercises at home and unease about addressing these intimate areas, impacting adherence to PFMT. Furthermore, this discomfort extended to their interactions with family members, leading to avoidance of discussing incontinence and a lack of understanding from others. However, implementing PFMT played a crucial role in overcoming these difficulties. By breaking the silence and fostering open communication, participants addressed their incontinence concerns and discomfort—ultimately enhancing their understanding of their condition and fostering positive confidence in their intimate body parts.

Given the abovementioned challenges in performing PFMT, for participants, it was essential to have a reference figure. This figure, more helpful than internet sources and peers’ insights, provided physical and psychological guidance and support throughout this process. Hence, we generated the fourth and last theme by focusing on this need.

Theme 4: ‘The Importance of Not Being Alone in this Process’

From interviewees’ perspective, the physiotherapist embodied the role of a guide, providing essential PFMT support and ultimately empowering participants’ care. This perception led to the generation of our final theme (Table 6).

Participants frequently encountered challenges in effectively recruiting pelvic floor muscles both before and at the beginning of PFMT. Here, the physiotherapist's role was essential in guiding them on proper pelvic floor contractions. The physiotherapist provided verbal feedback, tailored exercises, and educated participants about continence anatomy and physiology. This educative role was highly valued, fostering greater engagement and comprehension among interviewees, who felt truly actively involved in their healing process, guided by someone capable of helping them reach their goals.

In addition to physiotherapists’ educative and supportive role, interviewees emphasised the importance of having an empathetic figure alongside them, capable of transmitting calm and serenity. Effective verbal and nonverbal communication skills were crucial factors in this aspect. Notably, participants mentioned the importance of proxemics, where physiotherapist’s delicate touch and composed voice reassured them. Asking for permission before approaching intimate areas further eased participants’ discomfort. This thoughtful approach fostered comfort and trust, ultimately enhancing the overall PFMT experience.

Ultimately, the physiotherapist played a crucial role in helping participants restore their body confidence and overall well-being. Physically, participants regained control over leakage, restoring lost function. Moreover, they felt more capable of managing their condition without experiencing negative feelings such as fear or insecurities regarding leakages, enabling them to return to everyday life. Supportive guidance and effective PFMT provided by the physiotherapist empowered participants to regain control over their lives, fostering renewed confidence and well-being.

Discussion

This study investigated PFMT’s experience in an Italian sample of people with UI. PFMT experience brought participants to learn to regain control of continence (‘Learn to Control the Unconscious Consciously’), to change their beliefs, self-management skills and mindset on the condition (‘Starting PFMT, Changing Mind’), to confront challenges related to their pelvic intimacy and the lack of knowledge about pelvic floor gradually (‘Into the unknown intimacy’), and finally, to learn the importance to be guided by a physiotherapist throughout their PFMT journey (‘The Importance of Not Being Alone in this Process’).

Before starting PFMT, UI profoundly affected participants’ lives by eliciting negative emotions. Participants coped by trying to control external factors, modifying daily habits, and behaving passively, seeing UI as a natural consequence of a previous event or life stage, consistent with previous evidence [15, 25, 26]. Cultural factors, embarrassment, and a lack of understanding about pelvic floor health and PFMT influenced the inclination to seek help [18, 27]. Seeking assistance occurred when symptoms worsened or significantly impacted their lives. To get guidance and understanding of PFMT, participants often relied on word-of-mouth recommendations from people who shared similar experiences, social media websites or leaflets provided by healthcare professionals. This behaviour generated a virtuous circle of mutual feedback that helped people to engage in PFMT, as observed in other populations [28, 29]. However, participants acknowledged the challenge of independently performing exercises described in informational materials, as reported elsewhere [28, 30].

Starting PFMT enhanced participants’ understanding of pelvic floor muscles anatomy, physiology, and its role in maintaining continence. Consequentially, participants developed positive treatment expectations and reshaped their beliefs and mindset about their condition. Positive treatment expectations are a known and relevant factor for therapy success [14, 31]. This transformation involved awareness of their capacity to control and influence their well-being, in contrast to their previous perception of powerlessness. PFMT empowerment aligns with findings from Jahromi M.K. et al., demonstrating how PFMT improved incontinent women's quality of life and self-esteem [32]. Considering these transformative effects, participants emphasised the importance of health education through educative campaigns and ensuring fast, direct access through the national healthcare system. The participants highlighted the direct access as a facilitator to start PFMT, as reported elsewhere [33, 34].

While undergoing PFMT, participants were surprised to witness its positive impact on their condition, increasing their sexual serenity and self-confidence, while extinguishing negative feelings. Active exercises were preferred over passive treatments or instrumental therapies, consistent with evidence in other conditions where active exercises seemed more effective than passive treatments in improving their symptoms [35, 36]. However, participants found pelvic exercises demanding as they had little awareness of their pelvic floor muscles. Even with written information, many struggled to achieve pelvic floor contraction, making passive treatments appear more feasible, even if less helpful [37]. Additionally, discomfort with intimate areas compounded these challenges, resulting in low adherence to home exercises. This aligns with a Cochrane Review's conclusion that regular and consistent ‘interaction’ with a professional supports PFMT adherence [38]. In support of this thesis, in their quasi-experimental study, Cross et al. highlighted the pivotal role of supervision in PFMT, demonstrating that supervised sessions notably enhance UI symptoms compared to individuals performing Kegel exercises independently [39]. These findings furtherly support the role of the physiotherapist in preventing the execution of incorrectly exercises when unsupervised [39].

To further stress this finding, participants perceived the physiotherapist's role to be fundamental to overcoming different UI-related challenges. Seen as a knowledgeable and supportive guide, the physiotherapist played a multifaceted role, shaping individuals’ understanding of the pelvic floor, optimising their physical skills, and generating positive feelings and expectations towards PFMT. Participants appreciated the practical tips and reminders for integrating PFMT into daily life and the use of aids like drawings, anatomical models, or pictures to aid comprehension. Equally significant was the empathetic communication style of the physiotherapist, facilitating open discussions, including intimate concerns, breaking the silence on UI, and overcoming their discomfort. These strategies contributed to developing an empowering relationship, enhancing treatment satisfaction [13, 30]. These physiotherapist’s attributes align with roles described by Hay-Smith et al., including educator, trainer, persuader, and enabler [13], and correspond to exercise adherence facilitators reported in other studies, encompassing knowledge, physical skill, feelings about PFMT, cognitive analysis, planning and attention, prioritisation, and service provision [13, 14, 40]. Finally, post-PFMT, participants reported higher body awareness and improved body perception, enhancing their quality of life and self-efficacy. Gaining physical control and self-efficacy are crucial for UI management, motivating continued PFMT and participants’ confidence [13, 30].

This study has limitations. Focusing on a specific Italian sample with UI who performed PFMT, makes this study non-representative of broader populations. Future research could expand on these findings in diverse contexts. Additionally, participants voluntarily joined the study, possibly feeling comfortable discussing their experiences and less affected by cultural taboos. Thus, they may represent only a subset of people with UI, particularly those more proactive in seeking PFMT care. The participants and the researchers were all white limiting the richness of our results. Thus, future studies might try to include the perspectives of other ethnicities. Conversely, the study’s strength lies in its pioneering exploration of PFMT’s transformative experience in a Mediterranean country, namely Italy.

Conclusion

Participants in this study with UI found PFMT valuable for their condition. Initially, PFMT enhanced knowledge and understanding about pelvic floor health and continence functioning, fostering body awareness, a positive and comfortable mindset, and proactive management of their condition. Active were preferred over passive therapies due to their effectiveness in regaining control over continence. In this process, the physiotherapist played a crucial role as an educator, planner, and empathetic communicator. Considering these results, PFMT proved to be a valuable resource for UI, even from individuals’ perspective.

References

Buckley, B.S., Lapitan, M.C.M.: Prevalence of urinary incontinence in men, women, and children—current evidence: findings of the fourth international consultation on incontinence. Urology 76, 265–270 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.UROLOGY.2009.11.078

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management Clinical guideline (2010)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management NICE guideline (2019)

Corrado, B., Giardulli, B., Polito, F., Aprea, S., Lanzano, M., Dodaro, C.: The impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life: a cross-sectional study in the metropolitan city of Naples. Geriatrics 5, 1–14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/GERIATRICS5040096

Tang, D.H., Colayco, D., Piercy, J., Patel, V., Globe, D., Chancellor, M.B.: Impact of urinary incontinence on health-related quality of life, daily activities, and healthcare resource utilization in patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. BMC Neurol. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-14-74

Pizzol, D., Demurtas, J., Celotto, S., Maggi, S., Smith, L., Angiolelli, G., et al.: Urinary incontinence and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 33, 25–35 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/S40520-020-01712-Y

Lim, R., Liong, M.L., Leong, W.S., Khan, N.A.K., Yuen, K.H.: Effect of stress urinary incontinence on the sexual function of couples and the quality of life of patients. J. Urol. 196, 153–158 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JURO.2016.01.090

(UK) NGA: Pelvic floor muscle training for the prevention of pelvic floor dysfunction. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training for the Prevention of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Prevention and Non-Surgical Management: Evidence Review F (2021)

Alouini, S., Memic, S., Couillandre, A.: Pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence with or without biofeedback or electrostimulation in women: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 2789 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19052789

Cacciari, L.P., Morin, M., Mayrand, M.H., Tousignant, M., Abrahamowicz, M., Dumoulin, C.: Pelvic floor morphometrical and functional changes immediately after pelvic floor muscle training and at 1-year follow-up, in older incontinent women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 40, 245–255 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/NAU.24542

Hodges, P.W., Stafford, R.E., Hall, L., Neumann, P., Morrison, S., Frawley, H., et al.: Reconsideration of pelvic floor muscle training to prevent and treat incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Urol. Oncol. 38, 354–371 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.UROLONC.2019.12.007

Lee, H.N., Lee, S.Y., Lee, Y.S., Han, J.Y., Choo, M.S., Lee, K.S.: Pelvic floor muscle training using an extracorporeal biofeedback device for female stress urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 24, 831–838 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-012-1943-4

Hay-Smith, J., Dean, S., Burgio, K., McClurg, D., Frawley, H., Dumoulin, C.: Pelvic-floor-muscle-training adherence “modifiers”: a review of primary qualitative studies-2011 ICS State-of-the-Science Seminar research paper III of IV. Neurourol. Urodyn. 34, 622–631 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/NAU.22771

Dumoulin, C., Alewijnse, D., Bo, K., Hagen, S., Stark, D., Van Kampen, M., et al.: Pelvic-floor-muscle training adherence: tools, measurements and strategies-2011 ICS state-of-the-science seminar research paper II of IV. Neurourol. Urodyn. 34, 615–621 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/NAU.22794

Kao, H.T., Hayter, M., Hinchliff, S., Tsai, C.H., Hsu, M.T.: Experience of pelvic floor muscle exercises among women in Taiwan: a qualitative study of improvement in urinary incontinence and sexuality. J. Clin. Nurs. 24, 1985–1994 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1111/JOCN.12783

Hay-Smith, E.J.C., Ryan, K., Dean, S.: The silent, private exercise: experiences of pelvic floor muscle training in a sample of women with stress urinary incontinence. Physiotherapy 93, 53–61 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSIO.2006.10.005

Yoshikawa, K., Brady, B., Perry, M.A., Devan, H.: Sociocultural factors influencing physiotherapy management in culturally and linguistically diverse people with persistent pain: a scoping review. Physiotherapy 107, 292–305 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSIO.2019.08.002

Elenskaia, K., Haidvogel, K., Heidinger, C., Doerfler, D., Umek, W., Hanzal, E.: The greatest taboo: urinary incontinence as a source of shame and embarrassment. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 123, 607–610 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00508-011-0013-0

Lutz, S., Davidson, R.: Carnal Knowledge: The Social Politics and Experience of Sex Education in Italy, 1940–80 2009, pp. 120–38. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203891407-14

Booth, A., Hannes, K., Harden, A., Noyes, J., Harris, J., Tong, A.: COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies). Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: A User’s Manual 2014, pp. 214–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118715598.CH21

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., et al.: Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 25, 652–661 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide (2021)

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/CAPR.12360

Byrne, D.: A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/S11135-021-01182-Y/FIGURES/D

Mishra, G.D., Kumar, D., Pathak, G.A., Vaishnav, B.S.: Challenges encountered in community-based physiotherapy interventions for urinary incontinence among women in rural areas of Anand District of Gujarat, India. Indian J. Public Health 64, 17–21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPH.IJPH_436_18

Bayat, M., Eshraghi, N., Naeiji, Z., Fathi, M.: Evaluation of awareness, adherence, and barriers of pelvic floor muscle training in pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 27, e122–e126 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000852

Schreiber Pedersen, L., Lose, G., Høybye, M.T., Jürgensen, M., Waldmann, A., Rudnicki, M.: Predictors and reasons for help-seeking behavior among women with urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 29, 521–530 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-017-3434-0

Araya-Castro, P., Roa-Alcaino, S., Celedón, C., Cuevas-Said, M., de Sousa, D.D., Sacomori, C.: Barriers to and facilitators of adherence to pelvic floor muscle exercises and vaginal dilator use among gynecologic cancer patients: a qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 30, 9289–9298 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-022-07344-4

Hirschhorn, A.D., Kolt, G.S., Brooks, A.J.: Barriers and enablers to the provision and receipt of preoperative pelvic floor muscle training for men having radical prostatectomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13, 305 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-305

Torres-Lacomba, M., Navarro-Brazález, B., Yuste-Sánchez, M.J., Sánchez-Sánchez, B., Prieto-Gómez, V., Vergara-Pérez, F.: Women’s experiences with compliance with pelvic floor home exercise therapy and lifestyle changes for pelvic organ prolapse symptoms: a qualitative study. J. Pers. Med. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/JPM12030498

Rossettini, G., Carlino, E., Testa, M.: Clinical relevance of contextual factors as triggers of placebo and nocebo effects in musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12891-018-1943-8

Kargar Jahromi, M., Talebizadeh, M., Mirzaei, M.: The effect of pelvic muscle exercises on urinary incontinency and self-esteem of elderly females with stress urinary incontinency, 2013. Glob. J. Health Sci. 7, 71–79 (2014). https://doi.org/10.5539/GJHS.V7N2P71

Washington, B.B., Raker, C.A., Sung, V.W.: Barriers to pelvic floor physical therapy utilization for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 205, 152.e1-152.e9 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2011.03.029

Frawley, H.C., McClurg, D., Mahfooza, A., Hay-Smith, J., Dumoulin, C.: Health professionals’ and patients’ perspectives on pelvic floor muscle training adherence-2011 ICS State-of-the-Science Seminar research paper IV of IV. Neurourol. Urodyn. 34, 632–639 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/NAU.22774

Lluch, E., Arguisuelas, M.D., Quesada, O.C., Noguera, E.M., Puchades, M.P., Pérez Rodríguez, J.A., et al.: Immediate effects of active versus passive scapular correction on pain and pressure pain threshold in patients with chronic neck pain. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 37, 660–666 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMPT.2014.08.007

Owen, P.J., Miller, C.T., Mundell, N.L., Verswijveren, S.J.J.M., Tagliaferri, S.D., Brisby, H., et al.: Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1279–1287 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2019-100886

Cosio, D., Lin, E.: Role of active versus passive complementary and integrative health approaches in pain management. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956118768492

Hay-Smith, E.J.C., Herderschee, R., Dumoulin, C., Herbison, G.P.: Comparisons of approaches to pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochr. Database Syst. Rev. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009508

Cross, D., Waheed, N., Krake, M., Gahreman, D.: Effectiveness of supervised Kegel exercises using bio-feedback versus unsupervised Kegel exercises on stress urinary incontinence: a quasi-experimental study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 34, 913–920 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00192-022-05281-8

Jaffar, A., Mohd-Sidik, S., Foo, C.N., Admodisastro, N., Salam, S.N.A., Ismail, N.D.: Improving pelvic floor muscle training adherence among pregnant women: validation study. JMIR Hum. Factors (2022). https://doi.org/10.2196/30989

Acknowledgements

This work was developed within the DINOGMI Department of Excellence framework of MIUR 2018-2022 (Legge 232 del 2016). We would like to thank all the physiotherapists who actively worked for the recruitment of participants: Paola Di Biase, Annabella Borrelli, Samanta Foi, Antonella Toriello, Arianna Bortolami, Chiara Fabbri, Elia Bassini and Angela Cimarelli.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Genova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was carried out within the framework of the project "RAISE—Robotics and AI for Socio-economic Empowerment” and has been supported by European Union—NextGenerationEU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. All authors drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Ethics Approval

It was conducted in respect of the Declaration of Helsinki and reported following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research for reporting qualitative studies. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for University Research (CERA), University of Genova (approval date: 17/02/2022; CERA2022.14). The participants signed informed consent to participate before participation.

Consent to Participate

The participants signed informed consent for publication before participation.

Consent to Publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication, but we have no pictures or videos to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giardulli, B., Coppola, I., Testa, M. et al. The Experience of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in People with Urinary Incontinence: A Qualitative Study. Sex Disabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-024-09863-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-024-09863-w