Abstract

We map the topic structure of psychology utilizing a sample of over 500,000 abstracts of research articles and conference proceedings spanning two decades (1995–2015). To do so, we apply structural topic models to examine three research questions: (i) What are the discipline’s most prevalent research topics? (ii) How did the scientific discourse in psychology change over the last decades, especially since the advent of neurosciences? (iii) And was this change carried by high impact (HI) or less prestigious journals? Our results reveal that topics related to natural sciences are trending, while their ’counterparts’ leaning to humanities are declining in popularity. Those trends are even more pronounced in the leading outlets of the field. Furthermore, our findings indicate a continued interest in methodological topics accompanied by the ascent of neurosciences and related methods and technologies (e.g. fMRI’s). At the same time, other established approaches (e.g. psychoanalysis) become less popular and indicate a relative decline of topics related to the social sciences and the humanities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Historically, psychology has been a discipline characterized by a high degree of internal differentiation between basic, applied, and clinical branches (Brennan and Houde 2017) which still exists today (Gaj 2016). This internal differentiation is driven by exchanges between the different branches of psychology with the natural sciences (e.g. evolutionary biology), or social sciences such as economics, political science, and sociology (Marshall 2009; Morf 2018; Schwartz et al. 2016). More recently, psychology witnessed the advent of neurosciences and the advance of technological devices such as the fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) (Marshall 2009; Yeung et al. 2017b). Consequently, the fMRI has led to new ways how to study the linkage between the mind and the brain, and is now widely applied in clinical branches of psychology (Berman et al. 2006; Fairburn and Patel 2017; Schwartz et al. 2016; Brennan and Houde 2017; Toomela 2019).

Despite the well-documented changes, it is not well understood how topics become established in the psychological discourse and whether this change is carried by high impact journals or less prestigious journals. While some studies with a focus on different disciplines stress the importance of the former (Kwiek 2020; Yeung et al. 2017a), others emphasize the role of mainstream and low-impact journals (Münch 2014; Yeung 2018), and interdisciplinarity for changes in the scientific discourse (Leahey and Moody 2014). Our goal is to contribute to the literature by providing an overview of the diverse landscape of psychology and mapping changes in its discourse. In order to do so, we ask:

-

1.

What are the discipline’s most prevalent research topics?

-

2.

How did the scientific discourse in psychology change over the last decades, especially since the advent of neurosciences?

-

3.

And was this change carried by high impact (HI) or less prestigious journals?

These questions cannot be answered by individual accounts, since scientists’ views tend to be shaped by their own disciplinary experience and academic environment. The psychological discourse is simply too broad to comprehend for individual scholars, “that an entire team of researchers working for several years could only map a fraction of all the texts, transcripts, or archives that define them” (Bail 2014, 469). Fortunately, computational linguistics provides the means to reconstruct the history of a field (Anderson et al. 2012; Munoz-Najar Galvez et al. 2020), explain scientists’ choice of research strategy (Foster et al. 2015), and model scientific discovery (Shi et al. 2015). A central feature of computational linguistics is the development of impersonal and automatic procedures that offer a more objective and top-down view compared with earlier attempts to map academic fields by insiders (Buurma 2015, 3).

We apply structural topic models (STMs) (Roberts et al. 2014) to a dataset consisting of 528, 488 abstracts of published journal articles and conference proceedings to provide answers for the three questions raised and to approximate psychology as a field. STMs allow us to reduce the high-dimensional space of research themes in a reproducible way and, hence, to extract the meaning inherent in a large corpus of psychological research.

In order to map the topic structure of psychology and its flux over time, our paper is structured as follows: We discuss the rich literature on how psychology is organized as a scientific discipline in sect. 2. We proceed with the introduction of our dataset, cleaning procedures of the textual data, and our methodological approach in sect. 3. The results on the changing landscape of research topics are presented in sect. 4. We close with discussing the limitations and future direction of research in sect. 5.

Literature review

Current debates regarding the state of psychology revolve mostly around questions of its multidisciplinarity and potential common ground in psychology and its subfields (Brennan and Houde 2017; Gentner 2010; Henriques 2017; Jackson 2017; Joseph 2017; Kaplan 2015; Marshall 2009; Melchert 2016; Miller 2010; Tryon 2017; Toomela 2019; Zagaria et al. 2020). Specifically, Melchert (2016) criticizes that the internal differentiation of psychology hinders the accumulation of reliable knowledge on the human psyche. Instead, he envisions psychology as a “unified clinical science” under the lead of cognitive sciences, neurosciences, and evolutionary biology. At the same time, other psychologists emphasize that it is precisely this diversity that contributes to advances in knowledge about the many facets of the human psyche (Jackson 2017; Joseph 2017; Miller 2010).

Despite this debate, few studies so far attempted to map the scientific discourse of psychology comprehensively. For example, Krampen et al. (2011) tried to forecast research trends in psychology using data provided by PsycINFO and PSYNDEX from 1977 to 2008. They assigned journal abstract data to the APA subject classification scheme and forecasted a relative decline in developmental psychology, methodology and statistics, organizational psychology with a focus on management, clinical psychology with a focus on psychotherapy, family psychology, and environmental psychology. Using the same data source, Krampen (2016) reports a decline of publications dealing with the history of psychology and thus self-reflexive studies on the discipline of psychology, whereas Krampen and Trierweiler (2016) uncovered increasing epistemic ties between psychology and the natural sciences that evolved from the 1920s onward. Flis and van Eck (2018) conducted an analysis of term co-occurence in titles and abstracts of 673,393 psychology articles published between 1950 and 1999 listed in PsycINFO. Their findings show a schism between experimental and physical psychology on the one hand, and applied psychology consisting of educational psychology, social psychology, as well as research on personality and clinical psychology on the other hand. Psychologists in the former domain apply experiments to investigate a limited number of treatment effects. In contrast, psychologists conducting research in the ‘applied’ branches ideal-typically rely on methods like correlation analysis or structural equation modeling. In this sense, the findings of Flis and van Eck (2018) empirically validate the observation of Cronbach (1957), who described an entrenchment between “experimentalists” and psychologists aligned to “correlational methods”.

Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation, Bittermann and Fischer (2018) studied the emergence of “hot topics” in psychology in German-speaking countries from 1980 to 2016. Based on 314, 573 English and German article abstracts listed in PSYNDEX and relying on the APA Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms, they investigated associations between topics uncovered and the terms provided by the thesaurus. Their findings indicate a redefinition of theoretical concepts over time in addition to a different application of these concepts across domains of psychology.

Benjafield (2019) investigated the most salient keywords in anglophone psychology from 1887 to 2014. His findings suggest that keywords associated with the emergence of psychological paradigms are widely used over extended periods of time. These keywords include “learning”, “perception”, “memory”, “motor”, “personality”, “performance”, “program” and “schizophrenia” among others. Based on the analysis of shared scientific vocabulary between different disciplines, the findings of Benjafield (2020) provide empirical evidence for a shift in psychology towards the natural sciences, concluding that:

[...] much of what we now call psychology may end up being part of biology [...]. The remainder may coalesce around the study of aspects of the person that are not easily reducible to biology and consequently may develop stronger affiliations with the humanities. (Benjafield 2020, 15)

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated increasing alignments with the natural sciences for various subfields of psychology. For example, an examination of topics in sport and exercise psychology journals between 2008 and 2011 suggests a relative dominance of research on motivation with links to cognitive science and intersections between sport and health psychology (Lindahl et al. 2015). Furthermore, they identified isolated research areas such as “behavioral change, physical activity, and health”, “performance, anxiety, and chocking”, and “talent development and expertise”. Preckel and Krampen (2016) analyzed PSYNDEX data of research on highly gifted and mentally impaired persons issued between 1980 and 2014. They note a dramatic increase in research on gifted students since the 2000s and a growing number of empirically oriented papers. Kaplan (2015) identifies two distinct research cultures in educational psychology: Post-positivists who apply quantitative methods, and interpretative researchers using mainly qualitative methodology. In his view, the former is aligned to the natural sciences and increasingly endorsed as the sole legitimate paradigm in educational psychology due to the possibility to replicate experimental findings. At the same time, interpretative research is increasingly marginalized because its findings are harder to reproduce and do not presuppose universal laws of the psyche.

Moreover, studies show an increasing influence of neurosciences on the psychological discourse. Yeung et al. (2017b) reveal neuroscience research to be increasingly important in the domains of behavioral sciences, geriatrics and gerontology and – especially – psychology. Methodologically, Yeung et al. (2017a) note that statistical, computational, and technical approaches aligned with neurosciences are increasingly common in HI-journals. These methods are related to topics such as physiology, motor function, anatomy, aging, social neuroscience, and language and learning. Interestingly, a significant share of highly influential neurosciences papers (measured in citation rates) were not published in high impact journals and indicate the importance of other journals for the dissemination of novel insights (Yeung and Ho 2018).

Taken together, the findings provided by previous research indicate firstly an occurring shift towards the natural sciences primarily driven by neurosciences and cognitive sciences. Second, experimental methods and the use of fMRIs and other advanced imaging devices increasingly exert influence on the psychological discourse. Finally, it remains unclear whether the changes in the psychological discourse towards the natural sciences are driven by publications in HI or mainstream journals.

Data and methods

We utilize the Web of Science database to describe the research discourses in psychology, to map the landscape of psychological topics discussed in HI journals and mainstream journals as well as conference proceedings, and the changes over time. We queried the Web of Science database in September 2018 and downloaded all abstracts associated with at least one of the following Web of Science categories: “Psychology”, “Psychology, Psychoanalysis”, “Psychology, Multidisciplinary”, “Psychology, Experimental”, “Psychology, Clinical”, “Psychology, Educational”, “Psychology, Mathematical”, “Psychology, Social”, “Psychology, Developmental”, “Psychology, Biological”, “Psychology, Applied”. We then excluded all non-English abstracts. In total, our corpus included 528, 488 abstracts, stemming from articles published in 642 psychology outlets and 709 conference proceedings (1, 351 items in total).

As is common in quantitative text analysis, the acquired data needed to be prepared and cleaned. In a first step, we removed all stopwords like “in”, “and”, “or”, “the”. Following this, we tokenized and lemmatized the wordsFootnote 1. Lemmatization is a common step in NLP to reduce different forms of a word (e.g., singular and plural) to a common base form. As a last preprocessing step, we concatenated bigrams appearing more than 50 times to detect phrases like “factor_analysis” or “statistical_significant” in our abstract data (Blaheta and Johnson 2001).

Working with large amounts of texts is a long-standing issue in the field of information retrieval (e.g. Billhardt et al. 2002). The main idea is to summarize a corpus of documents by reducing their dimensions, but to keep, at the same time, most of its relevant information. One popular branch of information retrieval is topic modeling (Jordan and Mitchell 2015), where a set of documents is assigned to meaningful themes (i.e. “topics”). Topics are directly derived from the documents by probabilistic algorithms and consist of words that co-occur across documents.

In so-called generative models, each topic is seen as a probability distribution across all words of a given language, describing the likelihood for a word to be chosen to be part of a certain topic (Blei et al. 2003; Griffiths and Steyvers 2004). Since this likelihood is independent of the position of the word in a text it is sometimes referred to as a “bag-of-words” representation of documents. Although this assumption is clearly not realistic (e.g. grammar is ignored), it has been proven to be very reliable in practical applications (DiMaggio et al. 2013; McFarland et al. 2013).

In this paper, we use a recently developed variety of probabilistic topic models called Structural Topic Models (STMs) by Roberts et al. (2014). Its key feature is to enable researchers to utilize document metadata (e.g. year) to improve the estimation of topics. Including the publication date has proven to be especially useful for longer time periods and changing discourses (Farrell 2016). It has been shown that the incorporation of additional covariates as “a way of ‘structuring’ the prior distributions in the topic model” improves the topic quality substantially (Roberts et al. 2016, 1067). We follow this example and use the year of each document as a covariate in our models.

These improvements notwithstanding, the STM requires a researcher to make a decision on the number of topics (k) although the number of relevant themes is not known a priori. Insufficient numbers render models coarse, an excessive number could result in a model that is too complex. This is a widely recognized issue in topic modeling (e.g. Chang et al. 2009). To validate the number of topics, we first utilize two commonly used metrics, semantic coherence and exclusivity (Mimno et al. 2011; Roberts et al. 2014). Semantic coherence addresses whether a topic is internally consistent by calculating the frequency with which high probability topic words tend to co-occur in documents. However, semantic coherence alone can be misleading since high values can simply be obtained by very common words of a topic that occur together in most documents. To account for the desired statistical discrimination between topics we consider exclusivity. It provides us with the extent to which the words of a topic are distinct to it. Considering the optimum trade-off between exclusivity and coherence, we seek for a ‘plateau’, i.e., steps where coherence is not decreasing and, at the same time, exclusivity is not improving. We find such a range for \(k=(90,100)\) (cf. Fig. 5 in Appendix 1)Footnote 2.

To further analyze and label each topic, we applied a three-step qualitative interpretative design. In a first step, three scholars labeled each topic based on the ten most frequent and most specific tokens as well as the most typical abstracts. The list of these tokens was established using the FREX measure, which combines the weighted frequency with which a word occurs in the documents associated with a topic with the exclusivity of it occurring only in these documents (Bischof and Airoldi 2012). In a second step, two other researchers reviewed the labels given in the first step and calculated the agreement of the topic labels. The values of this agreement-measure are 0 if all topics are labeled differently, and 2 or 3 respectively if two or three labels were sufficiently similar. We did so to penalize completely different interpretations of the respective topics.

The topics were labeled sufficiently similar by 2.25 scholars on average. In sum, eleven of our 100 topics were inconsistently labeled and two were consistently identified as junk topics. The first junk topic includes notes on publishing procedures, psychological awards and information on professional associations (T30). The second consists of non-English tokens present in multilingual abstracts (T100). In the third step, the latter two researchers either assigned the topic labels according to the most agreed label or suggested a new label if all of the first three scholars disagreed on the label in the first step.

Findings

The following section addresses the three initially raised research questions. To do so, we first present the characteristics of the most prevalent, rising, and declining topics and group them thematically by clustering our findings into distinct topic groups. In sum, nine topic groups emerged from our data (see Table 1). We further provide the prevalence for each topic and all nine clusters. In total, we analyze 21 topics which comprise \(32.3\%\) of all tokens according to their theta values. We then proceed with analyzing differences in publication patterns in HI journals on the one hand, and mainstream journals and proceedings on the other hand.Footnote 3

Characteristics of the most prevalent topics

Beginning with the analysis of the ten most prevalent topics over the whole period between 1995 and 2015, we see that the most prevalent topic (psychoanalysis, topic 8) shows an average document-topic probability of \(3.38\%\) (see Fig. 1 for a depiction of the expected proportions of the ten most prevalent topics)Footnote 4. The expected document-topic probability refers to “the mean proportion of words across the documents that are assigned to this topic” (Roberts et al. 2014, online appendix 31).

Additionally, Table 2 provides an overview on the prevalence and FREX words of the ten most prevalent topics. This percentage seems small at first, but considering the number of 100 topics chosen for our STM, the value is considerably higher than the expected value of \(1\%\) per topicFootnote 5.

Three areas of research stand out within the ten most prevalent topics: methodology, cognition and perception, and studies on therapy and clinical intervention.

Topics focusing on methodology included research on quantitative methods with emphasis on item response theory (T38) and psychometrics (T47). These were the two most prevalent topics, revealing an ongoing debate on the adequacy of methods used in psychology. Against this backdrop, a variety of different research designs are addressed by psychology scholars, representing the field’s methodological diversity: Regression models, e.g. multilevel-, fixed-, random- and mixed effects models, monte-carlo simulations, and model misspecifications as sources of errors (T38), as well as reliability and validity of psychometric scales (T47). Both indicate a prevalence of quantitative methods in the psychological discourse.

Studies focusing on cognition and perception are associated with cognitive theories (T29), visual perception (T1), and spatial recognition (T73). Cognitive theories focus mainly on the development of mental models, reasoning, and the theory of mind. They aim to explain cognitive misconceptions of visual stimuli and for understanding visual information processing (T1). Similar patterns emerge for research on spatial recognition (T73). Again, the tokens loading high on the topic point to experimental designs to study the ability to process information or focus on two (or more) stimuli simultaneously.

Therapy and clinical trials include two topics and highlight a drive towards applications in psychology. Topics associated with this line of research include addiction interventions (T63), and psychoanalysis (T8). Whereas the former is aligned with clinical trials and experiments as methodological underpinnings, the latter is characterized by the relation between clients and psychotherapists in addition to the application of qualitative research methods. This methodological divide shows an alignment with the natural sciences for topics 63 and 88 (clinical trials of anti depressants), and alignment with social scientific approaches for therapeutic consultation for topic 8.

Three further topics are among the ten most prevalent which are representatives of distinct groups of topics discussed in more detail in the following sections. These are response reinforcement (T49), group theory (T80), and working memory (T85). The first topic focuses on animal experimentation, reinforced learning and conditioning and belongs to a topic cluster identified as behaviorism and animal experiments. The topic group theory covers concepts related to status formation, stereotypes, discrimination, and social identity. Hereby, a topic cluster is established that revolves around group dynamics. The last topic, working memory, belongs to a topic cluster centered on learning and memorization. Research belonging to this topic relies on experiments to measure performance on memorization tasks and information processing while being distracted or confronted with two or more types of information simultaneously. These topics specifically focus more strongly on experiments and a have a strong connection towards natural sciences.

Overall, applied, theoretical, and methodological topics are represented in similar proportions in the ten most prevalent topics during the study period.

Changes in psychological discourse

In order to analyze the changes in psychological discourse, we apply linear regression to illustrate the general (linear) trend of a subject over time and define the rise and decline of topics by the slope of their prevalence across timeFootnote 6. It is important to mention that this neither accounts for short-term changes at the beginning or end of the time frames, nor does it consider non-linear trends in the topics prevalence. While this is a clear limitation of our research design, it is also necessary to highlight the general trends in topic prevalence. Using a non-linear trend would be preferable, yet it would require a formal theory of semantic drifting in order to predict the amount of uptake or downturn one could expect on average. At the point of writing it is not clear if something like this would even be possible.

In order to make the changes in the psychological discourse more comparable, only the ten most declining as well as the ten topics with the steepest rise are considered to illustrate the changes in the discourse of psychology. The restriction to only focus on the Top 10 only is somewhat arbitrary, since we could just as well selected only nine or even eleven. However, since any other choice on the matter would be just as arbitrary and because we want to depict the overall changes, we chose a subset which we find to be illustrative.

Trending topics

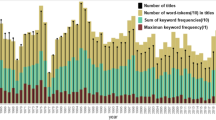

There are topics discussed in psychology outlets that are gaining ground over time or witness relative decline in prominence (see Fig. 2). In this regard, Table 3 provides information on topic prevalence, FREX words and slopes of the ten trending topics.

Turning to trending topics, we see a mixture of topics associated with cognitive science, addictive and mental disorders, life satisfaction and motivation on the rise. Furthermore, there is some overlap between the highest trending and the most prevalent topics, namely addiction interventions (T63) and spatial recognition (T73). We also witness the ascent of brain imaging techniques (T54) within psychology outlets from 1995 (\(\sim 0.5\%\)) to 2015 (\(\sim 1.6\%\) share on all publications). In fact, T54 shows the steepest slope of all trending topics and signals the rise of neuroscience topics in psychology. The topic brain imaging techniques is characterized by biological terms related to different areas of the brain, and by tokens related to brain imaging techniques such as the fMRI. As it does not fit into the previously introduced and discussed topic clusters, neurosciences emerge as a separate topic cluster from our data.

Looking on the other trending topics, we see a debate on regression models (T21), life satisfaction (T69) in general, the impact of chronic illnesses and quality of life (T76), research on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism (T51), smoking behavior (T52), motivation (T67) and facial recognition (T3) gaining momentum. With this in mind, we are able to expand our topic clusters by either adding topics to already established clusters or by introducing new groups of topics.

Beginning with the former, we are able to add regression models (T21) to the methodology topic cluster. The tokens associated with this topic suggest that associated studies deal with predictive power of regression models, regression techniques in general, mediator effects and structural equation modeling. Albeit not as prevalent as our more general topics on quantitative methods and psychometrics, the topic of regression models indicate an ongoing interest in the refinement of classical statistical methods.

Facial recognition (T3) belongs to the cognition and perception topic cluster. It is associated with studies using experimental designs, and focus on ethnic discrimination based on skin color and facial expression of minorities. In contrast to the other, more prevalent topics belonging to the same topic cluster, facial recognition is more applied and aligned to social issues.

Turning to the clinical studies and clinical interventions topic cluster, we are able to append topic 51 dealing with OCD and autism. Topic 51 deals with conditions correlating to OCD and related disorders such as learning disabilities and accompanying character traits (e.g. hyperactivity or repetitive behavior patterns). It addresses a specialized and thematically limited subfield of psychology and by doing so distinguishes itself from the more prevalent and more general topics in the clinical studies and clinical interventions-cluster.

Moreover, we are able to add two additional topic clusters based on the remaining four topics. The first is labeled quality of life and includes life satisfaction (T69) and chronic illness and quality of life (T76). The former topic (T69) deals with the impact of positive thinking and positive events on short-term and long-term life satisfaction. Additionally, it covers subjective definitions of a “good life” and explores the relationship between character traits and life satisfaction. The latter topic (T76) sheds light on the relation between physical and mental health with a particular focus on chronic diseases. In contrast to the former, more biological terms are related to chronic illnesses and quality of life compared to life satisfaction, unveiling the mind-body dualism still present in psychology (Brennan and Houde 2017).

The second new topic cluster was labeled as addiction and self-regulative behavior and includes motivation (T67) and smoking (T52). Motivation deals with issues of procrastination, time usage and leisure time, and the investigation of different types of motivation (e.g. intrinsic or extrinsic motivation). Beyond that, it is discussed what types of self-regulative behaviors are negatively associated with procrastination. Smoking focuses on the reasons for adolescents to start and ways to quit smoking. This topic also deals with self-regulative behavior and its association with smoking patterns, relapse, and mental health problems associated with smoking patterns.

Overall, we see specialized, applied and thematically driven topics gaining ground in psychology. Methodologically, these topics are aligned with experimental designs and classical statistical methods such as regression techniques.

Declining topics

Now that we witnessed neurosciences, applied as well as rather specialized topics gaining prevalence as against other topics in psychology, which topics are in decline and what are their characteristics compared to trending topics?

At first glance, we observe a more or less continuous decline of six prevalent topics, namely visual perception (T1), quantitative methods with focus on item response theory (T38), psychometrics (T47), and response reinforcement / behavioral experiments (T49), psychoanalysis (T8), and cognition theory (T29). Of these topics, psychoanalysis witnessed the steepest decline. This however does not imply a fall from grace as seen in the still sizable prevalence of the psychoanalysis topic (T8). Besides the topics mentioned above, we witness a relative decline of memory loss disorders (T7), quantitative methods (validity) (T75), animal experiments (diet) (T41) and animal testing (T41). Table 4 gives an overview on the ten declining topics, their prevalence, FREX terms, and slopes.

Similar to the trending topics, we are able to assign additional topics to the thematic clusters. First of all, we can assign memory loss disorders (T7) to the topic cluster learning and memorization. In contrast to topic working memory (T85), it deals with cognitive impairment following Alzheimer’s disease, different forms of dementia and Parkinson’s disease. It further links memory loss disorders with clinical studies or biological descriptions of their effects on the brain, memorization and motor abilities.

Secondly, quantitative methods (validity) (T75) seems to fall straight into the already established methodology cluster. This topic deals with psychometric issues related to experiments and questionnaires, e.g. recall or information retrieval in item scales. It complements psychometrics insofar, as it focuses on the participants’ abilities to answer items correctly and to recall information. Furthermore, the topic quantitative methods (validity) is characterized by the absence of tokens related to prediction and model specifications. Therefore, the topic cluster reveals that the methodological discourse in psychology seems to focus increasingly on objective measurements and model specifications.

At last, we can assign animal experiment (diet) (T41) and animal testing (T96) to the behaviorism and animal experimentation topic cluster. Animal experiments on diet are characterized by tokens stemming from biology. The experiments described focus on the effects of diets and nutrition intake (or lack thereof) on the animals’ bodies. Furthermore, behavioral changes related to modifications of food intake are discussed. At last, animal testing involves the study on the effects of drugs and medication on the subjects’ bodies. Beside the physical effects, the impact of drugs and medication on task performance, regular behavior, and memorization were tested.

Insofar, both topics differ substantially from response reinforcement. They focus on physical reactions and the impact of administered substances instead of programming and learning of behavior. Also, both topics are more concerned with the description of the effects administered drugs and medication or forced dietary changes have on the animals’ bodies. This clearly sets them apart from response reinforcement with their focus on the explanation of learning behavior. We therefore see a divide among topics concerned with description and explanation with the former in decline.

The division of topics in high impact journals and mainstream journals

Not all contributions to the knowledge base in psychology are published in equally visible journals. Prior studies in the field of higher education research suggest differences in the spread of disciplinary knowledge depending on journal prestige (Kwiek 2020; Yeung et al. 2017a). It is therefore reasonable to assume that topics with the ability to shape an entire academic discipline are mainly discussed in HI journals. However, as Münch (2014) and Yeung (2018) suggest, new and innovative topics may be discussed in rather marginalized outlets and have the ability to subvert the disciplinary discourse.

With this in mind, we take a closer look at trending and declining topics and their representation in HI and mainstream journals. We define the ten journals with the highest journal impact factor related to psychology according to the Web of Science database as HI journals. In this regard, Fig. 3 decomposes the changes in prevalence over time for the ten trending topics and their appearance in high impact journals (orange line) versus mainstream journals (blue line). The same is shown in Fig. 4 for declining topics.

Regarding trending and declining topics, we see two patterns emerge. Firstly, there are topics, whose growth is primarily driven by growing shares in publications in HI journals. The same applies for declining topics. Secondly, we find topics, where the gain or loss in prevalence is driven in equal parts by HI and mainstream journals. Beginning with trending topics, we see brain imaging (T54) and addiction interventions (T63) to belong to the first category. These findings signal not only growing prevalence, but also importance and ascribed quality within the psychological discourse.

On the other hand, psychoanalysis (T8) witnesses a decline in prevalence, mainly driven by a loss in prevalence in HI journals at the end of our observation period. This finding indicates that psychoanalysis with its focus on the interaction between therapist and client does not match the current trend in psychological research with its growing emphasis on objectivity and approaches aligned to the natural sciences.

Discussion and conclusion

Our paper explores the scholarly discourse held in psychology outlets and provides a descriptive overview of the topics that inform psychological research and its changing discourse over the last two decades. The most remarkable result is that psychology appears to head towards an application oriented, clinical discipline with a growing focus on brain imaging techniques (e.g., fMRI) and approaches closely aligned to neurosciences and cognitive sciences. This development is reflected in the rising prevalence of clinical trials, cognitive sciences, neurosciences, cognitive psychology and studies addressing quality of life issues. On the one hand, this concurs with Melchert’s (2016) vision of psychology as a unified clinical science under the lead of neurosciences, cognitive sciences, and evolutionary biology. On the other hand, our analysis also shows that the multiparadigmatic roots of psychology described by Brennan and Houde (2017) and criticized by Gentner (2010) or Melchert (2016) are still present today. This resonates with Jackson (2017), Henriques (2017), and Tryon (2017), who advocate for diversity in psychology in order to study phenomena as comprehensively as possible.

Our findings reveal an internal hierarchy of different domains which align with natural sciences as more popular and social sciences / humanities as less popular factions. This becomes particularly visible in the growth of neurosciences in the psychological discourse, which was published above average in HI journals. As indicated by Yeung et al. (2017a), neuroscience research fell on fertile ground in psychology and was able to connect to already existing research in the domain of cognition sciences and cognitive psychology. This corroborates the findings of Gentner (2010) and Schwartz et al. (2016) that the neurosciences substantially contribute to the mind-body duality debate in psychology.

Furthermore, our paper provides evidence for the decreasing alignment between psychology and the humanities on the one hand, and an increase in relevance of the natural sciences (Krampen 2016; Krampen and Trierweiler 2016). This is especially true for the neurosciences and cognitive sciences as examined by Yeung (2018) and Yeung and Ho (2018). This substantiates previous findings of Benjafield (2020), who noted that psychology might end up either as part of biology or a divided discipline, whereby this division occurs in both basic research and clinical applications.

However, our findings do not support the forecast of Krampen et al. (2011). Albeit we found a decrease in the coverage of psychoanalysis and some areas of quantitative methods, we found growing prevalence of organizational psychology and coverage of regression techniques and methodology aligned to the neurosciences. Changes in the foundations of psychology seem to be carried by HI- and mainstream journals, albeit the topic proportions indicate no dominance of one particular branch of psychology.

Our study is, of course, prone to a number of limitations. Firstly, we rely on the Web of Science database and the pre-defined category of psychology. This is mostly due to the wider accessibility of the data. An alternative approach would have been to rely on the PsycINFO database. PsycINFO covers 2, 307 journals with a total of 2, 434, 849 publications issued between 1995 and 2015 in contrast to our 528, 488 abstracts, of which 487.816 are available in both databasesFootnote 7. Our sample therefore covered \(20.03\%\) of the abstracts available on PsycINFO between 1995 and 2015. Secondly, these numbers indicate that systematic errors may occur due to our use of the Web of Science database. For example, the inclusion of abstracts issued in journal articles and conference proceedings could lead to over- or underestimation of topics as well as their actual change over time. Thirdly, given the interdisciplinary nature of neuroscience and its strong connection to biology and life sciences, a significant amount of the associated research would not be included in our dataset. Future studies could address these three problems by using the PsycINFO database. Since it is curated by the APA, it is the most comprehensive and accurate database that may be used to conduct scientometric studies on psychology.

Despite these limitations, our study provides insights into how topics change over time depending on their coverage in HI and mainstream journals. In this vein, future studies could investigate how neurosciences and applied clinical branches of psychology spread into other branches of psychology. Taking a closer look at interdisciplinary areas between psychology and other disciplines could therefore shed light on the question whether dominated or marginalized methods and paradigms are transferred to other disciplines, such as the social sciences. Finally, we encourage scholars to investigate the overlap between PsycINFO, Web of Science and other databases as an avenue for future research. A replication study could thus, for example, map nuances in topic development not captured in the dataset obtained in Web of Science. Such a comparison can contribute insights into how individual subject areas (such as psychology) are delimited in the respective databases and what impact the respective definition has on the topics discussed in the discipline according to topic modeling approaches.

Notes

To remove stopwords we used the snowball stopword list from the stopwords package in R (Benoit et al. 2020), and custom wordlists containing (1) time related words (“year”, “january”, etc.), (2) numeral related words (“one”, “tenth”, etc.), and (3) miscellaneous subject related words (“examine”, “study”, etc.). The lemmatization was achieved through the ‘lemmatize_words’ function of the R package ‘textstem’ (Rinker 2018). The abstracts were tokenized into words through the ‘tokenize_words’ function of the R package ‘tokenizers’ (Mullen et al. 2018).

Please note that across all evaluated numbers of topics we find a high consistency of topic-document assignments (further details are discussed in "Appendix 1").

We denoted the ten journals with the highest impact factor in 2018 as HI journals. These include Annual Review of Psychology, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Psychological Bulletin, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Psychological Inquiry, Clinical Psychology Review, and Personality and Social Psychology Review.

Note that junk topic 30 dealing with APA and publication issues is even more prevalent, but without meaning for our analysis. Because of this we decided to exclude it from our analysis.

The expected average document-topic probability is calculated by 1/k.

The changes over time were significant for each topic except topics 6 (teamwork), 13 (memory), 23 (animal communication), and 58 (neurotransmitters). A full account of the significance of change in topic proportion, intercept and slope is given in "Appendix 2".

A comparison between our sample and PsycINFO is provided in "Appendix 3".

References

Anderson, A., McFarland, D., & Jurafsky, D. (2012). Towards a computational history of the ACL: 1980-2008. In Proceedings of the ACL-2012 special workshop on rediscovering 50 years of discoveries, association for computational linguistics (pp. 13–21).

Arora, S., Ge, R., Halpern, Y., Mimno, D., Moitra, A., Sontag, D., et al. (2013). A practical algorithm for topic modeling with provable guarantees. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 280–288).

Bail, C. A. (2014). The cultural environment: Measuring culture with big data. Theory and Society, 43(3–4), 465–482.

Benjafield, J. G. (2019). Keyword frequencies in anglophone psychology. Scientometrics, 118(3), 1051–1064.

Benjafield, J. G. (2020). Vocabulary sharing among subjects belonging to the hierarchy of sciences. Scientometrics, 125, 1965–1982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03671-7.

Benoit, K., Muhr, D., & Watanabe, K. (2020). stopwords: Multilingual Stopword Lists. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stopwords, r package version 2.0.

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Nee, D. E. (2006). Studying mind and brain with fMRI. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1(2), 158–161.

Billhardt, H., Borrajo, D., & Maojo, V. (2002). A context vector model for information retrieval. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(3), 236–249.

Bischof, J. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2012). Summarizing topical content with word frequency and exclusivity. In Proceedings of the 29th International ConferEnce on Machine Learning (pp. 8–16). https://icml.cc/Conferences/2012/papers/113.pdf.

Bittermann, A., & Fischer, A. (2018). How to identify hot topics in psychology using topic modeling. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 226, 3–13.

Blaheta, D., & Johnson, M. (2001). Unsupervised learning of multi-word verbs. In Proceedings of the 39th annual meeting of the ACL, association for computer linguistics (pp. 54–60).

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022.

Brennan, J. F., & Houde, K. A. (2017). History and systems of psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buurma, R. S. (2015). The fictionality of topic modeling: Machine reading Anthony Trollope’s Barsetshire series. Big Data & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715610591.

Chang, J., Gerrish, S., Wang, C., Boyd-Graber, J. L., & Blei, D. M. (2009). Reading tea leaves: How humans interpret topic models. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 288–296).

Cronbach, L. J. (1957). The two disciplines of scientific psychology. American Psychologist, 12(11), 671–684.

DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of US government arts funding. Poetics, 41(6), 570–606.

Fairburn, C. G., & Patel, V. (2017). The impact of digital technology on psychological treatments and their dissemination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 88, 19–25.

Farrell, J. (2016). Corporate funding and ideological polarization about climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(1), 92–97.

Flis, I., & van Eck, N. J. (2018). Framing psychology as a discipline (1950–1999): A large-scale term co-occurrence analysis of scientific literature in psychology. History of Psychology, 21(4), 334–362.

Foster, J. G., Rzhetsky, A., & Evans, J. A. (2015). Tradition and innovation in scientists’ research strategies. American Sociological Review, 80(5), 875–908.

Gaj, N. (2016). Unity and fragmentation in psychology: The philosophical and methodological roots of the Discipline. Milton Park: Routledge.

Gentner, D. (2010). Psychology in cognitive science: 1978–2038. Topics in Cognitive Science, 2(3), 328–344.

Griffiths, T. L., & Steyvers, M. (2004). Finding scientific topics. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences, 101(suppl 1), 5228–5235.

Grimmer, J., & Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis, 21(3), 267–297.

Henriques, G. (2017). Achieving a unified clinical science requires a meta-theoretical solution: Comment on Melchert (2016). American Psychologist, 72(4), 393–394.

Jackson, M. R. (2017). Unified clinical science, or paradigm diversity? Comment on Melchert (2016). American Psychologist, 72(4), 395–396.

Jordan, M. I., & Mitchell, T. M. (2015). Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science, 349(6245), 255–260.

Joseph, S. (2017). The problem of choosing between irreconcilable theoretical orientations: Comment on Melchert (2016). American Psychologist, 72(4), 397–398.

Kaplan, A. (2015). Opinion: Paradigms, methods, and the (as yet) failed striving for methodological diversity in educational psychology publifshed research. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01370.

Krampen, G. (2016). Scientometric trend analyses of publications on the history of psychology: Is psychology becoming an unhistorical science? Scientometrics, 106(3), 1217–1238.

Krampen, G., & Trierweiler, L. I. (2016). Some unobtrusive indicators of psychology’s shift from the humanities and social sciences to the natural sciences. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 8(3), 44–66.

Krampen, G., Von Eye, A., & Schui, G. (2011). Forecasting trends of development of psychology from a bibliometric perspective. Scientometrics, 87(3), 687–694.

Kwiek, M. (2020). The prestige economy of higher education journals: a quantitative approach. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00553-y.

Leahey, E., & Moody, J. (2014). Sociological innovation through subfield integration. Social Currents, 1(3), 228–256.

Lindahl, J., Stenling, A., Lindwall, M., & Colliander, C. (2015). Trends and knowledge base in sport and exercise psychology research: a bibliometric review study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 8(1), 71–94.

Marshall, P. J. (2009). Relating psychology and neuroscience: Taking up the challenges. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 113–125.

McFarland, D. A., Ramage, D., Chuang, J., Heer, J., Manning, C. D., & Jurafsky, D. (2013). Differentiating language usage through topic models. Poetics, 41(6), 607–625.

McFarland, D. A., Lewis, K., & Goldberg, A. (2016). Sociology in the era of big data: The ascent of forensic social science. The American Sociologist, 47(1), 12–35.

Melchert, T. P. (2016). Leaving behind our preparadigmatic past: Professional psychology as a unified clinical science. American Psychologist, 71(6), 486–496.

Miller, G. A. (2010). Mistreating psychology in the decades of the brain. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(6), 716–743.

Mimno, D., Wallach, H. M., Talley, E., Leenders, M., & McCallum, A. (2011). Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. In Proceedings of the conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 262–272).

Morf, M. E. (2018). Agencyc Chance, and the scientific status of psychology. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 52(4), 491–507.

Mullen, L. A., Benoit, K., Keyes, O., Selivanov, D., & Arnold, J. (2018). Fast, consistent tokenization of natural language text. Journal of Open Source Software, 3, 655. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00655.

Münch, R. (2014). Academic capitalism: Universities in the global struggle for excellence. Milton Park: Routledge.

Munoz-Najar Galvez, S., Heiberger, R., & McFarland, D. (2020). Paradigm wars revisited: A cartography of graduate research in the field of education (1980–2010). American Educational Research Journal, 57(2), 612–652.

Preckel, F., & Krampen, G. (2016). Entwicklung und Schwerpunkte in der psychologischen Hochbegabungsforschung. Psychologische Rundschau, 67, 1–14.

Rinker, T. W. (2018). Textstem: Tools for stemming and lemmatizing text. http://github.com/trinker/textstem, version 0.1.4.

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., Tingley, D., Lucas, C., Leder-Luis, J., Gadarian, S. K., et al. (2014). Structural topic models for open-ended survey responses. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 1064–1082.

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2016). A model of text for experimentation in the social sciences. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111(515), 988–1003.

Rule, A., Cointet, J.-P., & Bearman, P. S. (2015). Lexical shifts, substantive changes, and continuity in State of the Union discourse, 1790–2014. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(35), 10837–10844.

Schwartz, S. J., Lilienfeld, S. O., Meca, A., & Sauvigné, K. C. (2016). The role of neuroscience within psychology: A call for inclusiveness over exclusiveness. American Psychologist, 71(1), 52–70.

Shi, F., Foster, J. G., & Evans, J. A. (2015). Weaving the fabric of science: Dynamic network models of science’s unfolding structure. Social Networks, 43, 73–85.

Toomela, A. (2019). The Problem Psychology: A Science Yet to Become a Science. In A. Toomela (Ed.), The Psychology of Scientific Inquiry (pp. 1–11). Cham: Springer.

Tryon, W. W. (2017). Basing clinical practice on unified psychological science: Comment on Melchert (2016). The American Psychologist, 72, 399–400.

Yeung, A. W. K. (2018). Bibliometric study on functional magnetic resonance imaging literature (1995–2017) concerning chemosensory perception. Chemosensory Perception, 11(1), 42–50.

Yeung, A. W. K., & Ho, Y.-S. (2018). Identification and analysis of classic articles and sleeping beauties in neurosciences. Current Science, 114(10), 2039–2044.

Yeung, A. W. K., Goto, T. K., & Leung, W. K. (2017a). At the Leading Front of Neuroscience: A Bibliometric Study of the 100 Most-Cited Articles. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00363.

Yeung, A. W. K., Goto, T. K., & Leung, W. K. (2017b). The Changing Landscape of Neuroscience Research, 2006–2015: A Bibliometric Study. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 11, 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00120.

Zagaria, A., Ando’, A., & Zennaro, A. (2020). Psychology: A giant with feet of clay. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 54(3), 1–42.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers for important critiques and suggestions that significantly improved our article, as well as Brigitte Münzel and Isabella Czedik-Eysenberg for additional proofreading.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Science (grant numbers: 01PU17021A, 01PU17021B, 01PU17021C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Details on Structural Topic Models

Although STMs solve other technical issues like finding the optimal starting parameters and providing consistent results by a “spectral initialization” (Arora et al. 2013), selecting an appropriate number of topics is crucial for any further analysis. It remains a central task for researchers to interpret the latent semantic space qualitatively and decide whether the presented topics are meaningful or one is only “reading tea leaves” (Chang et al. 2009). Besides the problem of “garbage in, garbage out” ousting for all models (McFarland et al. 2016), determining the number of topics (k) is a wide-ranging decision made by the researcher. Insufficient numbers render models coarse, an excessive number could result in a model too complex for further investigation.

Comparable to efforts in cluster analysis to determine the optimal number of clusters, there is no “right” answer to the question on how many topics are appropriate for a given corpus (Grimmer and Stewart 2013; Munoz-Najar Galvez et al. 2020). Due to the fact that there is not a single, correct number of topics found in a corpus, careful examination and pondering of different topic solutions is key to choose a topic model that allows for qualitative judgment of the researchers (Rule et al. 2015). Fortunately, the qualitative consideration can be complemented and assisted by statistical measures.

Following this line of reasoning, we propose a twofold approach to choose the optimal number k of topics before we interpret the results of our STM qualitatively. First, we check internal validity of different choices of k by statistical measures. Second, we check consistency across k-models. Especially the last aspect demonstrates that almost all topics found by STMs are “nested”, and that k does not alter the semantic space substantially. Therefore our main unit of investigation is rather stable regardless of k being X or Y.

To investigate the internal validity of our models, we apply measures of semantic coherence and exclusivity. Both are widely used measures to approximate the number of k in topic models (Mimno et al. 2011; Roberts et al. 2014). The coherence of a semantic space addresses whether a topic is internally consistent by calculating the frequency with which words being highly associated with a topic (given by \(\theta\)) tend to co-occur in documents. However, semantic coherence alone can be misleading since high values can simply be obtained by very common words that occur together systematically in most documents and are associated with the same topic. We therefore consider the exclusivity of topics in order to select a model with optimal number of distinct topics (Roberts et al. 2014). This measure provides us with the extent to which the tokens of a topic are distinct to it, i.e. words that have only high loadings in one topic. Both exclusivity and coherence complement each other and, hence, are examined in concert to give us a comprehensive, quantitative impression on the choice of k.

Thus, we are looking for a “plateau” of both indicators. This gives us an upper limit for reasonable k-number of topics. Figure 5 shows that this limit may well be between 80 and 100. After that plateau, coherence falls rather rapidly and exclusivity increases only slightly. This holds when we depict the distribution of the metrics by topic using violin plots Fig. 6. 80 and 100 have the least outliers. To maximize resolution, we choose 100 as the best solution. As presented in Fig. 8 and Tables 5, 6, and 7 the hundred topics in our selected solution show very reasonable coherence and exclusivity values.

In addition, we check the consistency of our topic models across a range of k. For that purpose, we use the “Fowlkes-Mallows index” (FM). It provides a straight-forward way to measure consistency by investigating the rate of change with regard to topic-document assignments across different values of k. To assign topics to documents we used the max-approach so that each document is assigned to its maximum topic, i.e., the max-theta of a document defines its topic. Figure 7 shows that k on the x-axis represents similarity of topic-assignments for all docs between two consecutive k’s, i.e. a STM with k-topics is compared to the next smaller STM with \(k-50\). We see relatively high and growing values of consistency from 50 to 100 topics. The FM index at \(k=100\) marks the peak, i.e., the STM with 100 topics is largely consistent with lower ranges of k. After 100 topics, consistency declines before ascending again after 150 topics. The value at \(k=100\) suggests that almost two thirds of topic assignments are stable. Hence, the choice of k suggested by FM is in line with the values provided by the coherence and exclusivity measures.

Appendix 2: Significance levels of the slopes of the topic change over time

Tables

8,

9,

10,

11, and

Appendix 3: Additional Sample information

The PsycINFO database covers 2, 307 journals. In comparison, our sample comprises 642 journals of which 639 outlets are also contained in PsycINFO. Furthermore, we included 709 conference proceedings in our data. Insofar, we cover \(27.70\%\) of the journals included in PsycINFO. In total, the Web of Science sample used in this article includes 487, 816 of the 2, 434, 849 (\(20.03\%\)) abstracts of articles available in PsycINFO.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wieczorek, O., Unger, S., Riebling, J. et al. Mapping the field of psychology: Trends in research topics 1995–2015. Scientometrics 126, 9699–9731 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04069-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04069-9