Abstract

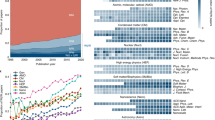

Many studies in political science and other disciplines show that published research by women is cited less often than research by male peers in the same discipline. While previous studies have suggested that self-citation practices may explain the gender citation gap in political science, few studies have evaluated whether men and women self-cite at different rates. Our article examines the relationship between author gender, author experience and seniority, and authors’ decisions to include self-citations using a new dataset that includes all articles published in 22 political science journals between 2007 and 2016. Contrary to our expectations, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that men are more likely cite their previous work than women, whether writing alone or co-authoring with others of the same sex. Mixed gender author teams are significantly less likely to self-cite. We also observe lower rates of self-citation in general field journals and Comparative/International Relations subfield journals. The results imply that the relationship between gender and self-citation depends on several factors such as collaboration and the typical seniority and experience of authors on the team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In political science, see Maliniak et al (2013), Mitchell et al (2013), Roberts et al (2018), Dion et al (2018); in other disciplines, see Ferber (1988). Håkanson (2005), Leahey et al (2008), Aksnes et al (2011), Ferber and Brun (2011), Cameron et al (2016), and Beaudry and Lariviere (Beaudry and Larivière 2016).

Interestingly, King et al’s (2017: 15) network analysis of 1.5 million JSTOR articles finds no significant correlation between the average number of self-citations and the percentage of male authors in a field.

This fits with a broader pattern of women being “punished” for self-promoting their citations (King et al 2018).

Women also tend to work more in interdisciplinary areas which can increase citations but depress the total number of publications, reducing the long run ability to accrue citations (Leahey et al 2017).

However, self-citations as a percentage of total citations are declining in many disciplines (Hyland and Jiang 2018). Given that our sample focuses on articles published in more recent years than King et al (2017), it is not surprising that the rate of self-citation in political science is lower in our study.

Teele and Thelen (2017) do not exclude ambiguous probabilities. Also, genderize.io fails to generate a prediction for some names for which it lacks sufficient information to make a reliable prediction, including many East and Southeast Asian given names. Yet handing coding of missing values does not alter results for gender citation gaps in political science (Dion et al 2018).

Only 68 (0.78%) articles have more than five authors, and the results do not change if we use the total number of authors.

While narrower subfields or topics exist, these are the largest fields within political science around which teaching and research activities are often organized. See Table 1 for a list of which journals are coded into which categories.

37.5% of the members of the American Political Science Association are women, although women’s representation in political science journals is much lower than expected (compared with female membership in sections who sponsor journals) for most journals affiliated with the organization (Dion and Mitchell2020).

Predicted probabilities with larger confidence intervals (e.g., solo female authors or non-alphabetical order all female teams) reflect smaller numbers of authors with these characteristics in the dataset.

Self-citation rates are generally lower in humanities fields compared with science fields. This is because these fields often have expectations for scholars to publish as “lone wolves” much like junior faculty in political science (Snyder and Bonzi 1998).

Using the testparm command (null hypothesis is base and interaction terms all simultaneously = 0) in STATA, we find that the variables are jointly significant for each model that includes interaction terms (Model 2: 2 = 471.12 with 9 degrees of freedom and p < 0.0001; Model 3: 2 = 312.85 with 9 degrees of freedom and p <0.0001).

We thank a reviewer for this suggestion. These alternate models are presented in the online appendix. For bootstrapped standard errors in the logit and event count models, we use the vce (bootstrap) option clustered by journal in STATA with 300 replications. For jackknife standard errors, we use the vce (jackknife) option clustered by journal.

Sometimes, when teams have a series of papers, they alternate alphabetical and reverse alphabetical or some other rotation of names, even when authorship is equal. While sometimes such decisions are noted in the paper, they are often left unstated.

This helps us understand why Maliniak et al (2013) found different results from ours, namely that women self-cite less often. Their sample contains a larger number of IR journals relative to the total sample than ours.

References

Aksnes, D. W. (2003). A macro study of self-citation. Scientometrics, 56(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021919228368.

Aksnes, D. W., Rorstad, K., Piro, F., & Sivertsen, G. (2011). Are female researchers less cited? A large-scale study of Norwegian scientists. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(4), 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21486.

Beaudry, C., & Larivière, V. (2016). Which gender gap? Factors affecting researchers’ scientific impact in science and medicine. Research Policy, 45(9), 1790–1817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.05.009.

Cameron, E. Z., White, A. M., & Gray, M. E. (2016). Solving the Productivity and Impact Puzzle: Do Men Outperform Women, or are Metrics Biased? BioScience, 66(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biv173.

Chamberlain, S., Boettiger, C., Hart, T., & Ram, K. (2017). rcrossref: Client for Various “CrossRef” “APIs”. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rcrossref/index.html. Accessed 4 December 2017

Crossref. 2018. Crossref REST API. https://api.crossref.org/

Deschacht, N., & Maes, B. (2017). Cross-cultural differences in self-promotion: A study of self-citations in management journals. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12162.

Dion, M., & Mitchell, S. M. (2020). How many citations to women in “Enough”? Estimates of gender representation in political science. PS: Political Science & Politics, 53(1), 107–113. doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519001173.

Dion, M. L., Sumner, J. L., & Mitchell, S. M. (2018). Gendered Citation Patterns across Political Science and Social Science Methodology Fields. Political Analysis, 26(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.12.

Ferber, M. A. (1988). Citations and Networking. Gender & Society, 2(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002001006.

Ferber, M. A., & Brün, M. (2011). The Gender Gap in Citations: Does It Persist? Feminist Economics, 17(1), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2010.541857.

Fowler, J. H., & Aksnes, D. W. (2007). Does self-citation pay? Scientometrics, 72(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1777-2.

genderize. (2018). genderize. https://genderize.io/.

Ghiasi, G., Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2016). Gender differences in synchronous and diachronous self-citations. In STI conference, 8. Valencia.

Glänzel, W., Debackere, K., Thijs, B., Schubert, A. (2006). A concise review on the role of author self-citations in information science, bibliometrics and science policy Scientometrics, 67(2), 263-–77.

Google Books. (2018). Google Books API. https://developers.google.com/books/

Håkanson, M. (2005). The Impact of Gender on Citations: An Analysis of College & Research Libraries, Journal of Academic Librarianship, and Library Quarterly | Håkanson | College & Research Libraries. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.66.4.312

Hesli, V. L., & Lee, J. M. (2011). Faculty Research Productivity: Why Do Some of Our Colleagues Publish More than Others? PS: Political Science & Politics, 44(2), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096511000242

Hutson, S. R. (2006). Self-Citation in Archaeology: Age, Gender, Prestige, and the Self. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-006-9001-5.

Hyland, K. (2003a). Self-citation and self-reference: Credibility and promotion in academic publication. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(3), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10204.

Hyland, K. (2003b). Self-citation and self-reference: Credibility and promotion in academic publication. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(3), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10204.

Hyland, K., & Jiang, F. (2018). Changing patterns of self-citation: cumulative inquiry or self-promotion? Text & Talk, 38(3), 365–387. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2018-0004.

Key, E.M., & Jane Lawrence Sumner. 2019. “You Research Like a Girl: Gendered Research Agendas and Their Implications.” PS: Political Science & Politics 52 (4): 663–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000945.

King, M. M., Bergstrom, C. T., Correll, S. J., Jacquet, J., & West, J. D. (2017). Men Set Their Own Cites High: Gender and Self-citation across Fields and over Time. Socius, 3, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023117738903.

Larivière, V., & Costas, R. (2016). How Many Is Too Many? On the Relationship between Research Productivity and Impact. PLOS ONE, 11(9), e0162709. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162709.

Leahey, E. (2008). Methodological Memes and Mores: Toward a Sociology of Social Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134731.

Leahey, E., Beckman, C. M., & Stanko, T. L. (2017). Prominent but Less Productive: The Impact of Interdisciplinarity on Scientists’ Research*. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(1), 105–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216665364.

Maliniak, D., Powers, R., & Walter, B. F. (2013). The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations. International Organization, 67(04), 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000209.

Mishra, S., Fegley, B. D., Diesner, J., & Torvik, V. I. (2018). Self-citation is the hallmark of productive authors, of any gender. PLoS ONE, 13(9), e0195773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195773.

Mitchell, S. M., Lange, S., & Brus, H. (2013). Gendered Citation Patterns in International Relations Journals. International Studies Perspectives, 14(4), 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12026.

Nielsen, M. W. (2016). Gender inequality and research performance: Moving beyond individual-meritocratic explanations of academic advancement. Studies in Higher Education, 41(11), 2044–2060. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007945.

Ooms, J., Lang, D. T., & Hilaiel, L. (2017). jsonlite: A Robust, High Performance JSON Parser and Generator for R. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/jsonlite/index.html. Accessed 4 December 2017

Snyder, H., & Bonzi, S. (1998). Patterns of self-citation across disciplines (1980–1989). Journal of Information Science, 24(6), 431–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/016555159802400606.

Teele, D. L., & Thelen, K. (2017). Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science. PS: Political Science & Politics, 50(2), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049096516002985

Wais, K., VanHoudnos, N., & Ramey, J. (2016). genderizeR: Gender Prediction Based on First Names. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/genderizeR/index.html. Accessed 4 December 2017.

Williams, H., Bates, S., Jenkins, L., Luke, D., & Rogers, K. (2015). Gender and Journal Authorship: An Assessment of Articles Published by Women in Three Top British Political Science and International Relations Journals. European Political Science, 14(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dion, M.L., Mitchell, S.M. & Sumner, J.L. Gender, seniority, and self-citation practices in political science. Scientometrics 125, 1–28 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03615-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03615-1