Abstract

Entrepreneurs can exhibit the entrepreneurial burnout syndrome, which retards entrepreneur and firm performance. Building upon insights from the conservation of resources theory of stress response and psychology theory, this study examined the role of entrepreneur emotional demands as well as job autonomy and satisfaction resources with regard to entrepreneurial burnout. Multivariate regression analysis relating to 273 entrepreneurs in France revealed that emotional demands were positively associated with entrepreneurial burnout, while job autonomy and satisfaction were negatively associated with entrepreneurial burnout. Job autonomy buffered the negative effect of emotional demands on entrepreneurial burnout. However, job satisfaction did not buffer the negative effect of emotional demands on entrepreneurial burnout. Implications are discussed.

Plain English Summary

Leveraging Autonomy as a Stress-Coping Resource for Entrepreneurial Well-Being.

External environmental disruptive events have promoted an urgent need for a better understanding of the factors associated with entrepreneurial burnout. We explored whether entrepreneur autonomy is a liability or a coping strategy. Insights from the conservation of resources and psychology theories were used to explore burnout reported by entrepreneurs in France. Entrepreneur emotional demands (i.e., strains) increased the risk of burnout. This risk was reduced when entrepreneurs had autonomy and job satisfaction resources. While the autonomy resource enabled the buffering of emotional strains that increase burnout, this was not the case with regard to the job satisfaction resource. Entrepreneurs need to obtain and maintain autonomy over time, which enables them to recuperate from emotional strains. Practitioners can play a role in encouraging entrepreneurs to be aware of the need to accumulate autonomy and job satisfaction resources, and the need to invest in coping strategies to reduce the risk of burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurs create, discover,and exploit business opportunities, and this can be emotionally and resource demanding, particularly in highly uncertain contexts (Torrès et al., 2022; Williamson, Gish & Stephan, 2021; Slavec Gomeze & Stritar, 2021).Further, entrepreneurs seeking to address internal and external resource barriers to firm survival and development may perceive the fortunes of their businesses rest upon their shoulders. Over time, entrepreneurs may view these responsibilities as a personal burden (Bencsik & Chuluun, 2021; Cubbon et al., 2020). Entrepreneurs can report high emotional demands (i.e., entrepreneurial burnout) because of one or more of the following issues: stress and frustration (Boyd & Gumpert, 1983; Shepherd et al., 2010; Lechat & Torrès, 2017; Wach et al., 2020); uncertainty and risk relating to business survival and development (Jamal, 2007; Lee et al., 2020; Rauch et al., 2018; Torrès et al., 2021); fear and anxiety (Boyd & Gumpert, 1983; Jamal, 2007; Lee et al., 2020); high workload (Lechat & Torrès, 2016); limited leisure time (van der Zwan & Hessels, 2019); and/or loneliness (Morris et al., 2012; Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011). Inevitably, entrepreneurs with negative emotions report the entrepreneurial burnout syndrome (Lechat & Torrès, 2016; Palmer et al., 2021; Torrès & Thurik, 2019; Wach et al., 2020). Supporting this view, evidence suggests that entrepreneurs reporting lower levels of negative emotions are less likely to experience entrepreneurial burnout (Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011).

While there has been growing research into emotional demands as important job stressors in the entrepreneurial context, debate surrounds the factors associated with entrepreneurial burnout (Lee et al., 2020; Gonçalves & Martins, 2021; Stephan, Rauch & Hatak, 2022). For example, Jamal (1997, 2007) detected that the self-employed reported higher levels of emotional strain and poorer mental health compared to salaried employees. This is because the self-employed face unconventional working hours and higher uncertainty. Conversely, Patzelt and Shepherd (2011) noted that entrepreneurs reported lower levels of negative emotional strain because of their willingness and ability to regulate their emotions. Baron et al. (2013) detected that entrepreneurs citing higher levels of psychological capital (i.e., self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience) reported low levels of stress. Further, Tetrick et al. (2000) found that entrepreneurs reported higher levels of job satisfaction compared with employees.

Diversity in prior study findings makes it hard to decide whether entrepreneurs are at higher or lower risk of burnout (Palmer et al., 2021). The mixed results from prior studies, in part, may be due to unobserved factors relating to work-stress relationships (Lee et al., 2020). Indeed, while it is recognized that self-employment can generate significant negative emotions (Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Williamson et al., 2022), not all negative emotions translate into burnout. The inability to understand the relationship between self-employment and stress outcomes compromises effective actions to enhance the resilience of the self-employed (Audretsch & Belitski, 2017, 2021) that face emotional strains. Theory is required to provide insights surrounding the link between entrepreneur emotional demands and entrepreneurial burnout.

To reconcile the opposing views highlighted above, there is the need to consider the boundary conditions of entrepreneurial burnout (i.e., the contingencies explaining the extent to which entrepreneur emotional demands translate into entrepreneurial burnout). This study builds upon insights relating to the conservation of resources theory of stress response (Hobfoll, 1989). The assumption is that individuals with limited resource pools face difficulties dealing with events, and this can lead to stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Entrepreneur autonomy and job satisfaction are entrepreneurial resources (Hundley, 2001; Williamson et al., 2021), and the accumulation of these resources enables entrepreneurs to engage in coping strategies that reduce the risk of entrepreneurial burnout.

We make a theoretical contribution to the entrepreneurial burnout literature by integrating insights from the conservation of resources theory of stress response and entrepreneurship psychology perspectives. Notably, we appreciate the links between entrepreneurs’ emotional demands, job autonomy, and satisfaction resources with regard to the risk of entrepreneurial burnout.

Multivariate regression analysis was conducted with reference to 273 entrepreneurs in France. Results support the direct positive effect of emotional demands, and the negative effects of job autonomy and job satisfaction in relation to entrepreneurial burnout. In addition, results support the negative moderator effect of job autonomy (i.e., function of the balance between entrepreneurs’ power and dependencies) with regard to burnout. Contrary to expectation, results do not support the moderator effect of job satisfaction in relation to burnout. We conclude that maintaining a high level of autonomy is a coping strategy that enables entrepreneurs to overcome emotional strains in the workplace, and this reduces the risk of burnout.

The article is structured as follows. In the next section, we discuss the conservation of resources theory of stress response and entrepreneurial burnout. Hypotheses are then derived. This is followed by a discussion of the methodology. Results from the multivariate regression analyses are then reported. This is followed by a discussion. Implications are then highlighted. Finally, conclusions are presented.

2 Conservation of resources theory of stress response and entrepreneurial burnout

2.1 Conservation of resources theory

Conservation of resources theory of stress response is a motivational theory relating the evolutionary need of people to acquire and utilize resources for survival. Resources are “defined as those objects, personal characteristics, conditions or energies that are valued by the individual or that serve as a means for attainment of these objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies” (Hobfoll, 1989; 516). The dynamic conservation of resources theory focuses on the importance of resource investment. Hobfoll (2001; 349) asserted that “[p]eople must invest resources in order to protect against resource loss, and gain resources” (Hobfoll, 2001; 349). Accordingly, individuals need to strive to obtain and maintain resources they require. The primacy of conservation of resources can be viewed as being crucial to understand the burnout process (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Halbesleben et al., 2014) with reference to the entrepreneurial context (Gorgievski et al., 2010).

Conservation of resources theorists conceptualize burnout in relation to the process of resource erosion, whereby individuals cannot compensate for resource losses (Hobfoll & Shirom, 2001). The demanding aspects of work can create a constant overtaxing, which leads to exhaustion (Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Burnout is most likely to occur in situations where there has been an actual resource loss, a perceived threat of resource loss, a situation in which resources were inadequate to meet work demands, and/or when the anticipated returns relating to resource investment were not obtained (Hobfoll, 1989). The strength of this theory in the context of entrepreneurial burnout is that it considers coping mechanisms to address the negative effects of strain (Hobfoll, 1989). Lazarus and Folkman (1991; 112) suggest that coping captures the “cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of a person.” Consequently, if entrepreneurs accumulate resources, this can have a direct impact reducing entrepreneurial burnout, and an indirect impact with a moderation relationship between job demands and entrepreneurial burnout.

We focus on the entrepreneur autonomy and job satisfaction resources (Dormann & Zapf, 2001; Hundley, 2001; Lange, 2012; Schjoedt, 2009; van Gelderen, 2016; van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006). These resources relate to two different coping strategies. Indeed, Patzelt and Shepherd (2011) argue that the self-employed balance the negative emotions associated with self-employment with regard to problem-focused coping or emotions-focused coping. Problem-focused coping refers to dealing with sources of negative emotions (e.g., making a plan of action). Achieving and maintaining autonomy is part of this coping strategy. Entrepreneurs dealing with negative emotions can balance their autonomy with the demands imposed on them by internal and external stakeholders. However, emotions-focused coping involves regulating the experience of negative emotions by, for example, engaging in distractive activities. Job satisfaction (i.e., positive emotional state) (Locke, 1976) is an emotions-coping strategy where entrepreneurs derive job satisfaction from their core job characteristics (Alstete, 2008; Schjoedt, 2009).

2.2 Entrepreneurial burnout

Burnout is experienced as physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by long-term emotional demands (Palmer et al., 2021), and is a syndrome that occurs when an individual is overcome with stress (Shepherd et al., 2010). It has been conceptualized with regard to emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of self-accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Emotional exhaustion occurs when an individual feels emotionally drained, and is associated with physical and/or psychological fatigue (Wright & Cropanzano, 1998). Depersonalization refers to a defensive mechanism whereby individuals distance themselves from situations when their emotional exhaustion is too high (Maslach et al., 2001). Reduced self-accomplishment refers to an individual’s perception of reduced competency to undertake an activity. For example, an activity previously easily performed is now perceived to be insurmountable.

Several conceptual and empirical studies have highlighted that emotional exhaustion dimension is central to the experience of burnout. Consequently, it is a primary dimension of the burnout process (Cropanzano et al., 2003; Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007; Seidler et al., 2014; Tuithof et al., 2017; Wright & Bonett, 1997). Studies suggest that compared to the other burnout dimensions, emotional exhaustion exhibits the most consistency in its relationships with other outcomes (Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007; Lechat & Torrès, 2016; Wright & Bonett, 1997).

As a professional activity, entrepreneurial behavior is defined by unique job characteristics, and entrepreneurial activity can be emotionally draining (Stephan et al., 2022; Williamson et al., 2021). Entrepreneur activities relate to creating and discovering business opportunities, acquiring and managing resources, and making quick decisions in highly uncertain situations (Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011). These activities can lead to entrepreneurs reporting negative emotions. For example, entrepreneurs can perceive being responsible for the business and its employees as a burden, and this can generate high levels of stress and frustration (Boyd & Gumpert, 1983). Risks and uncertainty about the future of the business can generate fear and anxiety related to the entrepreneur’s own personal future (Boyd & Gumpert, 1983; Jamal, 2007; Lee et al., 2020). Long working hours can lead to entrepreneurs reporting sleep issues (Guiliani & Torrès, 2018; Wolfe & Patel, 2020), and less time to pursue leisure activities (van der Zwan & Hessels, 2019). This can lead to entrepreneurs reporting loneliness and social isolation (Morris et al., 2012). If entrepreneurs perceive their working conditions to be overwhelming and threatening, this can lead to them reporting negative emotions.

Theoretical assumptions from the conservation of resources theory of stress response highlight the need to consider the balance between resources and demands (Bakker et al., 2005; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Job demands and resources are flexible pools of variables relating to the occupational context. Specifically, job demands are “those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort” (Demerouti et al., 2001; 501). People reporting high job demands can cite exhaustion, depression, and/or poor physical health (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

3 Hypotheses

3.1 Emotional demands

The highest risk of burnout occurs when individuals face high levels of emotional demands and/or when they have insufficient resources (Bakker et al., 2005). Emotional demands are qualitative aspects of occupational demands (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), and burnout being an outcome (Bakker et al., 2005; Lechat & Torrès, 2016; van de Ven, van den Tooren & Vlerick, 2013). Each work context is rich with emotions that are social experiences that influence worker behavior (Baron, 2008), such as complaints, impoliteness, and intimidation (Bakker et al., 2005). In some occupations, especially those involving significant interpersonal contact, emotional demands are extremely important (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Contact with customers (i.e., dealing with disproportionate customer expectations, customer verbal aggression, and disliked customers) can generate stress. High levels of stress are reported by professionals who are accountable to the demands of both clients and organizations (Lewin & Sager, 2007;van Gelderen, 2016). Entrepreneurs are members of this professional category. Entrepreneurship studies have emphasized that affective factors in the form of negative emotions are an important aspect of entrepreneurial burnout (Cardon et al., 2012; Doern & Goss 2013; Goss, 2008).

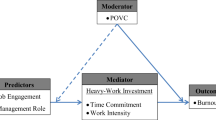

Entrepreneurial activity relates to affective events that are rich in terms of emotions (Lerman, Munyon & Carr, 2020). Lechat and Torrès (2016) explored 30 emotionally draining negative events (i.e., bankruptcy, workload and competitive pressure, resignation of an employee, etc.). Negative events can have a detrimental impact on entrepreneur well-being (Baumeister et al., 2001). Emotional demands typically arise from entrepreneurs’ interactions with the actors that are important to achieving business goals (i.e., financiers). Disagreements with external resource providers can generate stress for entrepreneurs (Lechat & Torrès, 2017; Wach et al., 2020). Consequently, some entrepreneur interpersonal interactions can be emotionally draining (Uy et al., 2010). Emotional demands vary between entrepreneurs, and from one day to the next (van Gelderen, 2016). These emotional demands can generate stress (Dijkhuizen et al., 2016). Excessive emotional demands diminish entrepreneurs’ energy, and take away the attention and effort required to ensure firm development. This discussion suggests the following hypothesis (see Fig. 1):

-

H1: Emotional demands are positively associated with entrepreneurial burnout.

3.2 Job resources

3.2.1 Autonomy

Viewed as both a source of motivation and an aspect of well-being (Ryff, 2019), autonomy can differentiate entrepreneurs from employees (Benz & Frey, 2008; Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006). Autonomy is a primary need for a large majority of entrepreneurs, and is instrumental for their accomplishment (Alstete, 2008; van Gelderen, 2016). It relates to “the extent to which a job allows freedom, independence, and discretion to schedule work, make decisions, and choose the methods used to perform tasks” (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; 1323). Autonomy is widely viewed as fixed trait (Benz & Frey, 2004; Hundley, 2001; Lange, 2012; Millán et al., 2020; Schjoedt, 2009). However, van Gelderen (2016) has asserted that autonomy is not guaranteed, and entrepreneurs need to address the challenge of attaining and maintaining a high level of autonomy. Indeed, while entrepreneurs can control their autonomy within the organization compared to employees, their autonomy can be challenged. Many autonomy-related tensions involve stakeholders outside the organization, such as financiers, suppliers, customers, and competitors. Entrepreneurs may have to choose between autonomy and stakeholder demands.

van Gelderen (2016) asserted that the amount of autonomy reported by entrepreneurs tends to be a function of the balance between power (i.e., capacity to do something), which enhances autonomy, and dependencies (i.e., state of relying on someone else), which is likely to reduce autonomy. When interests are competing, the “other” is seen as autonomy reducing. When interests are aligned, the “other” can be seen as autonomy enhancing. In the latter case, autonomy helps entrepreneurs to cope with the demands imposed on them by the external environment (Millán et al., 2020). Autonomy has also been shown to reduce burnout through the promotion of opportunities for personal growth and development, especially workplace learning (Ruysseveldt et al., 2011). With reference to the corporate entrepreneurship context (Shimizu, 2012), encouraging autonomous behavior enables managers to overcome risk-averseness, and unleash entrepreneurial ideas. Notably, autonomy is generally recognized for the positive influence it has on well-being (Shir et al., 2019; Williamson et al., 2021). Consequently, autonomy is a critical resource that entrepreneurs are likely to use to reduce the effect of emotional demands, and protect themselves from entrepreneurial burnout. This discussion suggests the following hypotheses (see Fig. 1):

-

H2a: Autonomy is negatively associated with entrepreneurial burnout.

-

H2b: Autonomy buffers the negative effect of emotional demands on entrepreneurial burnout.

3.2.2 Job satisfaction

Job characteristics influence an individual’s job satisfaction, with entrepreneurs reporting higher job satisfaction than employees (Alstete, 2008; Bradley & Roberts, 2004; Hundley, 2001; Schjoedt, 2009; Tetrick et al., 2000). Job satisfaction has been defined as “a person’s overall evaluation of his/her job as favorable or unfavorable. It reflects an attitude toward one’s job and hence includes affect, cognitions, and behavioral tendencies” (Meier & Spector, 2015; 1). Further, job satisfaction relates to a combination of feelings and beliefs in relation to one’s work (Akehurst et al., 2009). Job satisfaction has been found to be associated with diverse behaviors and attitudes, with implications for personal well-being and job performance (Ben Tahar, 2018; Millán et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2007).

Ben Tahar (2018) has asserted that job satisfaction can act at two different levels: by directly affecting the well-being of entrepreneurs, but also indirectly by inhibiting the effect of other negative personal and organizational factors. Indeed, psychology theorists argue that, as a “pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke, 1976; 1300), job satisfaction serves to buffer the harmful effects of stress (Fredrickson, 2001). This job resource function acts as an efficient antidote for the enduring effects of negative emotions created by stress. The moderator effect of job satisfaction is supported by the “undoing hypothesis” (Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998) developed by positive psychology scholars assuming that positive emotions might correct (or undo) the effect of negative emotions. The “undoing hypothesis” asserts that people might be able to improve their psychological well-being by cultivating experiences of positive emotions at opportune moments to cope with negative emotions (Fredrickson, 2001). In the same line of thought, Aspinwall et al. (2001) highlighted how positive affect serves as a resource for individuals coping with adversity. This discussion suggests the following hypotheses (see Fig. 1):

-

H3a: Job satisfaction is negatively associated with entrepreneurial burnout.

-

H3b: Job satisfaction buffers the negative effect of emotional demands on entrepreneurial burnout.

4 Method

4.1 Data collection

The Observatoire Amarok conference (http://www.observatoire-amarok.net/sites/wordpress) in France discusses entrepreneur physical and mental health, and seeks to reduce entrepreneurial burnout. A representative from three business clubs who attended the conference administered the questionnaire to their entrepreneur members. This approach to collect data via the Observatoire Amarok has been widely used (Bernoster et al., 2020; Lechat & Torrès, 2017; Leung et al., 2020; Torrès & Thurik, 2019). Purposive rather than stratified random sampling was conducted. An online structured survey was conducted with Entreprise Union 66 (l'Union Pour l'Entreprise 66) entrepreneurs, and CCREM (Club pour la Croissance et la Réussite des Enterprises de Méditérranée) entrepreneurs. All surveyed entrepreneurs were located on the Occitanie region. In addition, the survey was sent to the APM (Association Progrès du Management) that represents entrepreneurs throughout France. Forty percent of entrepreneurs drawn from the three lists answered all the questions on the questionnaire. A consistent key informant approach was used. Respondents to the survey were owners and key decision-makers in their small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with regard to the European definition of an SME (i.e., less than 250 employees, less than or equal to €50 million turnover, and less than or equal to €43 million balance sheet). Information was obtained from 273 entrepreneurs, of which 55 were females (20%) and 218 were males (80%).

4.2 Variables

4.2.1 Dependent variable

Entrepreneurial burnout is proxied by its core dimension relating to emotional exhaustion (Cropanzano et al., 2003; Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007; Seidler et al., 2014; Tuithof et al., 2017; Wright & Bonett, 1997). We used the items suggested in the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti et al., 2010) measured with reference to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (scored “1”) to “strongly agree” (scored “5”). The entrepreneurial burnout construct relates to seven items (Table 3 in the Appendix): “There are days when I feel tired before I arrive at work,” “After work, I tend to need more time to relax and feel better,” “After my work, I usually feel worn out and weary,” and “During my work, I often feel emotionally drained.” Responses to the following three items were reversed scored: “I can tolerate the pressure of my work very well,” “After working, I have enough energy for my leisure activities,” and “I am usually able to manage my workload well.” An exploratory factor analysis was conducted. Responses to the question “After my work, I usually feel worn out and weary” was associated with a weak factor loading. Answers to this question were not used to compute the emotional exhaustion construct. A high score indicates a high level of entrepreneurial burnout.

4.2.2 Independent variables

The independent variables relate to psychometric scales utilized in previous studies. We used the available French version scales relating to the emotional demands and autonomy-independent variables. With regard to the job satisfaction independent variable, the scale was translated into French by professional translators using the forward–backward translation process.

Emotional demands

We used Dupret et al.’s (2012) French version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (Kristensen et al., 2005). Emotional demands relate to the following three items: “Does your work put you in emotionally-disturbing situations?,” “Do you have to relate to other people’s personal problems as part of your work?,” and “Is your work emotionally demanding?” (Table 3 in the Appendix). Each item was measured on a scale “strongly disagree” (scored 1) to “strongly agree” (scored 5). A high score indicates a high level of emotional demands.

Autonomy

Autonomy relates to subscale of the Job Content Questionnaire comprising three items. We used the French version provided by Niedhammer et al. (2006). Respondents were presented with the following three items: “My work often allows me to make decisions on my own,” “In my job, I have very little freedom to decide how I do my work,” and “I have the opportunity to influence the course of my work” (Table 3 in the Appendix). The items relate to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (scored 1) to “strongly agree” (scored 5). The “My work often allows me to make decisions on my own” item was associated with a weak factor loading, and this item was excluded from the analysis. A high score indicates a high level of autonomy.

Job satisfaction

We used the subscale of job satisfaction from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Cammann et al., 1979). Job satisfaction relates to the following three items: “Overall, I am satisfied with my work,” “In general, I don’t like my work” (reversed scored), and “In general, I like to work at my company” (Table 3 in the Appendix). The items relate to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (scored 1) to “strongly agree” (scored 5). A high score indicates a high level of job satisfaction.

4.2.3 Control variables

Studies suggest that men are more prone to risk of burnout than women (Audretsch et al., 2020; Belitski & Desai, 2021), and seniority increases the risk of resource loss (Chayu & Kreitler, 2011). Two entrepreneur profile variables were operationalized as control variables. Entrepreneur gender (male = 1; female = 0) (male) (Kibler et al., 2019; Pugliesi, 1995), and number of years running a start-up (less than 1 year = 1; 1 to 5 years = 2; 6 to 10 years = 3, 11 to 15 years = 4; and more than 15 years = 5) (seniority) (Uy et al., 2013).

Studies suggest that smaller firms report higher closure rates (Stinchcombe, 1965), and less profitable firms face pressures that can generate entrepreneurial stress (Lechat & Torrès, 2017). Two firm profiles’ variables were operationalized as control variables. Firm size (0 employees = 1; 1 to 9 employees = 2; 10 to 49 employees = 3; and 50 to 249 employees = 4) (firm size), and profitability (scored from 1 = “strongly in deficit” to 5 = “highly profitable”) (profits).

4.2.4 Validity and common method

Content validity was considered. The structured questionnaire focused on questions found to be valid in previous studies relating to emotional exhaustion (i.e., entrepreneurial burnout), emotional demands, job autonomy, and job satisfaction. Common method bias was minimized through protection of respondent anonymity; reducing statement ambiguity by pre-testing in previous studies; a short, structured questionnaire that would encourage accurate responses; and statements relating to the dependent variable were not located close to the independent variables. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted relating to all the collected data (Table 3 in the Appendix). All loadings (less than 0.60) were eliminated. The constructs displayed acceptable reliability (Cronbach α > 0.7) and composite validity (CR > 0.7). During the second step, we calculated the convergent validity (i.e., average variance extracted (AVE)) and discriminant validity (i.e., maximum share variance (MSV)). All constructs reported AVE > 0.5. Further, all the constructs had MSV < AVE and ASV < AVE, which confirmed the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. The analysis, therefore, does not suffer from validity concerns. Descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix are reported in Table 1.

5 Results

Entrepreneurial burnout was estimated using a multivariate regression model (Wooldridge, 2009). The model allows for jointly estimating the role of various factors of entrepreneurial burnout. The following econometric model was estimated to test the hypotheses:

where \({\mathrm{y}}_{\mathrm{i}}\) is the entrepreneurial burnout of individual i at time t. Further, \({x}_{i}\) is a vector of explanatory variables (i.e., emotional demands, autonomy, and job satisfaction) of an individual i. All entrepreneur-level variables are for 1 year, as we observed them for the previous year lagged; \({m}_{it-1}\) is a vector of other control variables at the individual level, such as firm size. All coefficients of the regression estimation are reported in Table 2.

The model estimation is presented in Table 2. It consists of six specifications, and uses sensitivity analysis by adding additional control variables (specifications 2 to 4 in Table 2) and interaction analysis (specifications 5 to 6).

An increase in emotional demands by one standard deviation increased the burnout of entrepreneurs (\(\beta\) = 0.455; p ≤ 0.001) (specification 4). H1 was supported.

Job autonomy was negatively associated with burnout (\(\beta\) = − 0.122; p ≤ 0.01) (specification 4). Higher job autonomy enabled entrepreneurs to reduce burnout. Hypothesis H2a was supported. With reference to the interaction analysis, job autonomy buffered the negative effects of emotional demands relating to burnout (\(\beta\) = − 0.125; p ≤ 0.05) (specification 6). Hypothesis H2b was supported.

Job satisfaction was negatively associated with burnout (\(\beta\) = − 0.317; p ≤ 0.001). Entrepreneurs who were satisfied with their jobs reported lower levels of burnout. Hypothesis H3a was supported. With reference to the interaction analysis, job satisfaction did not buffer the negative effects of emotional demands on burnout (specification 5). Hypothesis H3b was not supported.

Other effects related to the control variables. Male entrepreneurs reported higher levels of burnout (Audretsch et al., 2020; Belitski & Desai, 2021). The seniority, firm size, and profits control variables were not significantly associated with burnout.

6 Discussion

6.1 Key findings

The COVID-19 pandemic and potential for further external environmental disruptive events have promoted an urgent need for a better understanding of the factors associated with entrepreneurial burnout (Torrès et al., 2022), and the coping strategies employed by entrepreneurs. Entrepreneur well-being is of critical relevance at the individual as well as the regional and national levels. Consequently, entrepreneur well-being is now attracting growing attention, which will ensure a more informed understanding of the entrepreneurial context (Stephan, 2018; Torrès & Thurik, 2019). However, knowledge relating to entrepreneurial burnout is underdeveloped. Prior studies have not detected clear or consistent links between entrepreneur profiles and well-being. Several entrepreneurial burnout studies have drawn upon insights from employee well-being studies. The latter insights may not be appropriate to the entrepreneur well-being context (de Mol et al., 2018). Currently, there is scant empirical evidence relating to how entrepreneurs cope with negative emotions relating to their entrepreneurial context, and what resources they can acquire to reduce the risk of entrepreneurial burnout. We sought to explore this gap in the knowledge base. Scholars have called for studies guided by theory (de Mol et al., 2018; Lechat & Torrès, 2016; Torrès & Thurik, 2019). We responded to this call by building upon insights from the conservation of resources theory of stress response and psychology theory. The role of entrepreneurs’ emotional demands, as well as job autonomy and satisfaction resources, was theorized with regard to the risk of entrepreneurial burnout. Further, the long-term effects of emotional demands on burnout were considered. We set boundary conditions relating to the assumed implicit direct impact of emotional demands relating to the entrepreneurial context. Setting boundary conditions through moderator effects is required to clarify the mixed results in previous studies (Baron et al., 2013; Jamal, 1997, 2007; Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Tetrick et al., 2000; Williamson et al., 2022). In doing so, our study considered emotional demands outcomes into the perspective by shedding light on the coping resources that are available to entrepreneurs.

Our findings align with some of those highlighted in previous studies that have focused on the determinants of negative emotions relating to the entrepreneurial context (Lechat & Torrès, 2017; Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Williamson et al., 2022). We took a step further and shifted our attention from antecedents to outcomes, hence emphasizing the long-term effects of entrepreneurial emotions on mental health. The multivariate regression analysis detected that emotional demands was positively associated with entrepreneurial burnout. As expected, job autonomy buffered the negative effect of emotional demands on burnout. The job satisfaction was also negatively associated with burnout. Despite the potential of the job satisfaction resource to reduce the level of burnout, the job satisfaction resource did not buffer the negative effect of emotional demands on burnout.

The buffering effect of autonomy, in this research, questions recent studies emphasizing the downside of entrepreneurial autonomy (e.g., Williamson et al., 2021). Authors argue that autonomy (an engaging aspect of entrepreneurship) makes entrepreneurs potentially more prone to burnout by preventing them from distancing themselves from work. We argue that autonomy should be investigated at different levels for a more accurate understanding of its effects on entrepreneurial burnout. For instance, autonomy vis-à-vis customers and other business stakeholders should be considered further in future research. At this level, autonomy refers to a reduced dependence vis-à-vis external partners due to aligned interests (van Gelderen, 2012), which is likely to help entrepreneurs to cope with the demands imposed by their engaging work.

6.2 Implications for theory

We contribute to theoretical discussion by highlighting the importance of entrepreneur resources in relation to entrepreneurial burnout. This study builds upon insights from the conservation of resources theory of stress response, which places the notion of resource accumulation and “resource loss” at the heart of understanding individual behavior (Hobfoll, 2011). We contribute to moving forward the conversation relating to relevance of specific entrepreneur resources (Cardon et al., 2012; Doern & Goss 2013, van Gelderen, 2016; Goss, 2008). Our discussion highlighted that entrepreneur emotional demands as well as job autonomy and satisfaction resources need to be theoretically considered. Presented results suggest that entrepreneur empowerment via autonomy was the most influential resource for protecting entrepreneurs from the detrimental effects of excessive emotional job demands, thus, creating a balance between job resources and job demands, a key assumption of the conservation of resources theory. Consequently, future theoretical discussion needs to appreciate that autonomy is a salutogenic rather than a pathogenic factor of business ownership (Torrès & Thurik, 2019). Salutogenic factors are stimuli from the external environment that entrepreneurs perceive in a positive and constructive manner, which, in turn, enhance entrepreneur physical and mental well-being.

Psychology of entrepreneurship scholars explore the new firm creation process, and the well-being of entrepreneurs (Gorgievski & Stephan, 2016). We contribute to this perspective by highlighting the need for the latter scholars to appreciate insights from the conservation of resources theory of stress response, to ensure a more informed appreciation of entrepreneur well-being. Further, we contribute by suggesting new directions in eudaimonic well-being research (Ryff, 2019) with regard to the entrepreneurial context.

6.3 Implications for practice

This research has several implications for practice. The findings suggest that emotionally drained entrepreneurs must make an effort to attain and maintain autonomy over time, which enables them to recuperate from stress. The main challenge for entrepreneurs is negotiating autonomy vis-à-vis their business environment. Autonomy can be threatened when stakeholders have demands that conflict with the entrepreneur’s beliefs and norms, or when they renegotiate terms and conditions. Developing emotional intelligence could potentially influence how successful entrepreneurs are in obtaining resources, or coping without them. This is because emotional intelligence enables them to understand their own and other individual’s emotions. Previous studies demonstrate that emotional intelligence allows individuals to have a more positive negotiating experience, and makes them more likely to be leaders (Wolff et al., 2002). Successful negotiations can increase an entrepreneur’s autonomy vis-à-vis their stakeholders, and reduce the burden of emotional strains they experience.

In addition, entrepreneur social competences (i.e., ability to use social skills to facilitate better interaction with actors) could play a critical role in increasing entrepreneur autonomy vis-à-vis external partners. For example, investments in networking to maintain existing ties, and identify new ties, lead to the accumulation of new information and knowledge, which is required to reduce the risk of entrepreneurial burnout, and address resource barriers to firm development (Stam et al., 2014). Investment in networking has the potential to increase an entrepreneur’s perceived autonomy and decrease dependence on existing stakeholders.

There is a case for policy-makers to directly (and indirectly) support enterprise development, training, and networking initiatives that encourage entrepreneurs to be aware of the need to accumulate new resources, and the array of coping and negotiation strategies that could be employed to reduce the risk of entrepreneurial burnout. Initiatives need to be contextualized to entrepreneur, industrial, and locational contexts. Investment in these initiatives could ensure firm development that stimulates wealth creation and job generation as well as societal benefits (Belitski et al., 2021; Khlystova et al., 2022; Westhead et al., 2005).

6.4 Limitations and directions for future research

In line with other studies, this study is associated with limitations that open opportunities for further research that replicate and/or extend the analysis we conducted. Our study gathered information provided by representatives from three business clubs attending AMAROK conference focusing upon entrepreneurial burnout. Future studies need to gather information from large representative samples of entrepreneurs. While this study focused upon valid and reliable constructs, there is the need to consider the external validity of presented findings in other locational contexts. Case studies with entrepreneurs reporting entrepreneurial burnout may provide fresh insights relating to the resources and coping strategies used. Information from other stakeholders seeking to reduce the problem of entrepreneurial burnout would provide additional insights. Overall, the results and shortcomings of this study call for more in-depth exploration of entrepreneurs’ autonomy perceptions, and different levels of autonomy. Studies could explore how entrepreneurs can realize and actively create their autonomy vis-à-vis the outside world, and through self-regulation. In addition, studies could explore the links between different levels of autonomy and their impacts on entrepreneurial burnout. We recognize that the dark side of autonomy (i.e., over-commitment to work and breaking down work-life boundaries) might be apparent in the absence of emotionally demanding work situations, while the positive side could be apparent in highly stressful contexts. Accordingly, the degree of autonomy could be leveraged with reference to an entrepreneur’s emotional state. Future studies need to consider entrepreneur emotions and autonomy simultaneously to ensure a more in-depth understanding of the role of the autonomy resource. This knowledge will draw attention to the actions that entrepreneurs can undertake to overcome the liability of the high latitude of control over their firms. Longitudinal studies will generate understanding surrounding the role of entrepreneur autonomy and job satisfaction resources over time with reference to reducing the risk of entrepreneurial burnout. Studies need to consider locational and industrial contexts as determinants of entrepreneurial burnout risk. Multidisciplinary approaches are warranted to provide more fine-grained understanding of entrepreneurial burnout. We encourage scholars to consider and explore the coping strategies that entrepreneurs can employ relating to their context.

6.5 Conclusion

Presented evidence contributes to the emerging entrepreneurial burnout debate, and highlights the need to consider entrepreneur resources and coping strategies appropriate for current and future disruptive external environmental conditions. This study has highlighted the need for scholars to consider the resources entrepreneurs require to reduce the risk of entrepreneurial burnout, which can retard firm survival and development. In addition, it has highlighted the need to appreciate that the insights from employee studies cannot be unequivocally transferred to the entrepreneur context. Notably, this study has revealed that the accumulation of specific entrepreneur resources reduced the risk of burnout. On the downside, the emotional demands resource was positively associated with burnout, while on the upside, the job autonomy and job satisfaction resources were negatively associated with burnout. Job autonomy buffered the negative effect of emotional demands on burnout. However, job satisfaction did not buffer the negative effect of emotional demands on burnout. The coping strategies highlighted are appropriate with regard to the COVID-19 crisis, and future disruptive external environmental events, which require entrepreneurs to pursue reliance behavior. Assuming an interventionist stance, to ensure entrepreneur well-being and the contributions of firms to job generation and wealth creation, there is a potential case for policy-makers and practitioners to draw attention to entrepreneurs that they need to accumulate the resources and the coping strategies discussed above, which are appropriate with reference to disruptive and non-disruptive external environmental contexts.

References

Akehurst, G., Comeche, J. M., & Galindo, M. A. (2009). Job satisfaction and commitment in the entrepreneurial SME. Small Business Economics, 32(3), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9116-z

Slavec Gomezel A, Stritar R (2021) Does it pay to be an ethical leader in entrepreneurship? An investigation of the relationships between entrepreneurs’ regulatory focus ethical leadership and small firm growth. Review of Managerial Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00512-6

Alstete, J. W. (2008). Aspects of entrepreneurial success. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(3), 584–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000810892364

Aspinwall, L. G., Richter, L., & Hoffman III, R. R. (2001). Understanding how optimism works: An examination of optimists’ adaptive moderation of belief and behavior. In Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 217–238). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10385-010

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(5), 1030–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9473-8

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2021). Towards an entrepreneurial ecosystem typology for regional economic development: The role of creative class and entrepreneurship. Regional Studies, 55(4), 735–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1854711

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., & Brush, C. (2020). Innovation in women-led firms: an empirical analysis. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2020.1843992

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In C.L. Cooper (Ed.), Wellbeing (pp. 1–28). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell019

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170

Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.31193166

Baron, R. A., Franklin, R. J., & Hmieleski, K. M. (2013). Why entrepreneurs often experience low, not high, levels of stress: The joint effects of selection and psychological capital. Journal of Management, 42, 742–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313495411

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Belitski, M., & Desai, S. (2021). Female ownership, firm age and firm growth: A study of South Asian firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(3), 825–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09689-7

Belitski, M., Guenther, C., Kritikos, A. S., & Thurik, R. (2021). Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Business Economics, 1-17.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00544-y

Ben Tahar, Y. (2018). La satisfaction professionnelle, une ressource pour les propriétaires-dirigeants de PME ? Revue De L’entrepreneuriat, 17(3), 15–40. https://doi.org/10.3917/entre.173.0015

Bencsik, P., & Chuluun, T. (2021). Comparative well-being of the self-employed and paid employees in the USA. Small Business Economics, 56(1), 355–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00221-1

Benz, M., & Frey, B. S. (2004). Being independent raises happiness at work. Swedish Economic Policy Review, 95–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00594.x>

Benz, M., & Frey, B. S. (2008). Being independent is a great thing: Subjective evaluations of self-employment and hierarchy. Economica, 75(298), 362–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00594.x

Bernoster, I., Mukerjee, J., & Thurik, R. (2020). The role of affect in entrepreneurial orientation. Small Business Economics, 54(1), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0116-3

Bradley, D. E., & Roberts, J. A. (2004). Self-Employment and job satisfaction: Investigating the role of self-efficacy, depression, and seniority. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2004.00096.x

Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Michigan, Michigan.

Carolin, Palmer Sascha, Kraus Norbert, Kailer Linda, Huber Zeynep Hale, Öner (2021) Entrepreneurial burnout: a systematic review and research map. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 43(3) 438–115883. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2021.115883

Chayu, T., & Kreitler, S. (2011). Burnout in nephrology nurses in Israel. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 38(1), 65–77.

Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160

Cubbon, L., Darga, K., Wisnesky, U. D., Dennett, L., & Guptill, C. (2020). Depression among entrepreneurs: A scoping review. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00382-4

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019408

de Mol, E., Ho, V. T., & Pollack, J. M. (2018). Predicting entrepreneurial burnout in a moderated mediated model of job fit: Predicting entrepreneurial burnout. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(3), 392–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12275

Dijkhuizen, J., Gorgievski, M., Veldhoven, M. van, & Schalk, R. (2016). Feeling successful as an entrepreneur: A job demands — Resources approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0354-z

Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2001). Job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of stabilities. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.98

Dupret, E., Bocéréan, C., Teherani, M., Feltrin, M., & Pejtersen, J. H. (2012). Psychosocial risk assessment: French validation of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire (COPSOQ). Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(5), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812453888

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L., & Levenson, R. W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 12(2), 191–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379718

Gonçalves, J., & Martins, P. S. (2021). Effects of self-employment on hospitalizations: Instrumental variables analysis of social security data. Small Business Economics., 57(3), 1527–1543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00360-w

Gorgievski, M. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Work engagement and workaholism: Comparing the self-employed and salaried employees. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903509606

Gorgievski, M. J., & Stephan, U. (2016). Advancing the psychology of entrepreneurship: A review of the psychological literature and an introduction. Applied Psychology, 65(3), 437–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12073

Guiliani, F., & Torrès, O. (2018). Entrepreneurship: An insomniac discipline? An empirical study on SME owners/directors. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 35(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2018.094273

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.93

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In Handbook of Organizational Behavior (2nd. Ed, rev. Ed and, exp.ed.) (57–80). Marcel Dekker.

Hundley, G. (2001). Why and when are the self-employed more satisfied with their work? Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 40(2), 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/0019-8676.00209

Jamal, M. (1997). Job stress, satisfaction, and mental health: An empirical examination of self-employed and non-self-employed Canadians. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(4), 18–57.

Jamal, M. (2007). Burnout and self-employment: A cross-cultural empirical study. Stress and Health, 23(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1144

Kibler, E., Wincent, J., Kautonen, T., Cacciotti, G., & Obschonka, M. (2019). Can prosocial motivation harm entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being? Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 608–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.10.003

Khlystova, O., Kalyuzhnova, Y., & Belitski, M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: A literature review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1192–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.062

Kristensen, T. S., Hannerz, H., Hogh, A., & Borg, V. (2005). The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 31(6), 438–449. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.948

Lange, T. (2012). Job satisfaction and self-employment: Autonomy or personality? Small Business Economics, 38(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9249-8

Lechat, T., & Torrès, O. (2016). Les risques psychosociaux du dirigeant de PME: Typologie et échelle de mesure des stresseurs professionnels. Revue Internationale P.M.E., 29(3–4), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038335ar

Lechat, T., & Torrès, O. (2017). Stressors and satisfactors in entrepreneurial activity: An event-based, mixed methods study predicting small business owners’ health. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 32(4), 537–569. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2017.10007974

Lee, S. H., Patel, P. C., & Phan, P. H. (2020). Are the self-employed more stressed? New evidence on an old question. Journal of Small Business Management, 27(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1796467

Lerman, M. P., Munyon, T. P., & Carr, J. C. (2020). Stress events theory: A theoretical framework for understanding entrepreneurial behavior. In Entrepreneurial and Small Business Stressors, Experienced Stress, and Well-Being. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1479-355520200000018003

Leung, Y. K., Mukerjee, J., & Thurik, R. (2020). The role of family support in work-family balance and subjective well-being of SME owners. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(1), 130–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1659675

Lewin, J. E., & Sager, J. K. (2007). A process model of burnout among salespeople: Some new thoughts. Journal of Business Research, 60(12), 1216–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.04.009

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Rand McNally.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.10.2307/2137048

Meier, L. L., & Spector, P. E. (2015). Job satisfaction. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management (pp.1–3). American Cancer Society. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118785317.weom050093

Millán, J. M., Hessels, J., Thurik, R., & Aguado, R. (2013). Determinants of job satisfaction: A European comparison of self-employed and paid employees. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 651–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9380-1

Millán, A., Millán, J. M., & Caçador-Rodrigues, L. (2020). Disclosing ‘masked employees’ in Europe: Job control, job demands and job outcomes of ‘dependent self-employed workers.’ Small Business Economics, 55(2), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00245-7

Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321

Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., Schindehutte, M., & Spivack, A. J. (2012). Framing the entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00471.x

Niedhammer, I., Chastang, J.-F., Gendrey, L., David, S., & Degioanni, S. (2006). Propriétés psychométriques de la version française des échelles de la demande psychologique, de la latitude décisionnelle et du soutien social du « Job Content Questionnaire » de Karasek: Résultats de l’enquête nationale SUMER. Santé Publique, 18(3), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.3917/spub.063.0413

Palmer, C., Kraus, S., Oner, H., Kailer, N., & Huber, L. (2021). Entrepreneurial burnout: A systematic review and research map. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 43(3), 438–461. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2021.115883

Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Negative emotions of an entrepreneurial career: Self-employment and regulatory coping behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.08.002

Pugliesi, K. (1995). Work and well-being: Gender differences in the psychological consequences of employment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 57–71.https://doi.org/10.2307/2137287

Rauch, A., Fink, M., & Hatak, I. (2018). Stress processes: An essential ingredient in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(3), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0184

Ryff, C. D. (2019). Entrepreneurship and eudaimonic well-being: Five venues for new science. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 646–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.09.003

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

Schjoedt, L. (2009). Entrepreneurial job characteristics: An examination of their effect on entrepreneurial satisfaction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00319.x

Seidler, A., Thinschmidt, M., Deckert, S., Then, F., Hegewald, J., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2014). The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion–A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-9-10

Shepherd, C. D., Marchisio, G., Morrish, S. C., Deacon, J. H., & Miles, M. P. (2010). Entrepreneurial burnout: Exploring antecedents, dimensions and outcomes. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/14715201011060894

Shimizu, K. (2012). Risks of corporate entrepreneurship: Autonomy and agency issues. Organization Science, 23(1), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0645

Shir, N., Nikolaev, B. N., & Wincent, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.05.002

Stam, W., Arzlanian, S., & Elfring, T. (2014). Social capital of entrepreneurs and small firm performance: A meta-analysis of contextual and methodological moderators. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 152–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.01.002

Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(3), 290–322. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0001

Stephan, U., Rauch, A., & Hatak, I. (2022). Happy entrepreneurs? Everywhere? (p. 10422587211072800). Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship and wellbeing.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In: J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 142–193.

Tetrick, L. E., Slack, K. J., Da Silva, N., & Sinclair, R. R. (2000). A comparison of the stress–strain process for business owners and nonowners: Differences in job demands, emotional exhaustion, satisfaction, and social support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(4), 464–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.4.464

Torrès, O., Benzari, A., Fisch, C., Mukerjee, J., Swalhi, A., & Thurik, R. (2022). Risk of burnout in French entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis. Small Business Economics, 1-23.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00516-2

Torrès, O., & Thurik, R. (2019). Small business owners and health. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0064-y

Tuithof, M., Ten Have, M., Beekman, A., van Dorsselaer, S., Kleinjan, M., Schaufeli, W., & de Graaf, R. (2017). The interplay between emotional exhaustion, common mental disorders, functioning and health care use in the working population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 100, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.018

Uy, M. A., Foo, M.-D., & Aguinis, H. (2010). Using experience sampling methodology to advance entrepreneurship theory and research. Organizational Research Methods, 13(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109334977

Uy, M. A., Foo, M. D., & Song, Z. (2013). Joint effects of prior start-up experience and coping strategies on entrepreneurs’ psychological well-being. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.04.003

van de Ven, B., van den Tooren, M., & Vlerick, P. (2013). Emotional job resources and emotional support seeking as moderators of the relation between emotional job demands and emotional exhaustion: A two-wave panel study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030656

van der Zwan, P., & Hessels, J. (2019). Solo self-employment and wellbeing: An overview of the literature and an empirical illustration. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 17(2), 169–188. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/121654

van Gelderen, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial autonomy and its dynamics. Applied Psychology, 65(3), 541–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12066

van Gelderen, M., & Jansen, P. (2006). Autonomy as a start-up motive. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000610645289

Van Ruysseveldt, J., Verboon, P., & Smulders, P. (2011). Job resources and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of learning opportunities. Work & Stress, 25(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.613223

Wach, D., Stephan, U., Weinberger, E., & Wegge, J. (2020). Entrepreneurs’ stressors and well-being: A recovery perspective and diary study. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(5), 106016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106016

Westhead, P., Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Binks, M. (2005). Novice, serial and portfolio entrepreneur behaviour and contributions. Small Business Economics, 25(2), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-003-6461-9

Williamson, A. J., Drencheva, A., & Wolfe, M. T. (2022). When do negative emotions arise in entrepreneurship? A contextualized review of negative affective antecedents. Journal of Small Business Management, 1-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2026952

Williamson, A. J., Gish, J. J., & Stephan, U. (2021). Let’s focus on solutions to entrepreneurial ill-being! Recovery interventions to enhance entrepreneurial well-being. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(6), 1307–1338. 10.1177.

Wolfe, M. T., & Patel, P. C. (2020). I will sleep when I am dead? Sleep and Self-Employment. Small Business Economics, 55(4), 901–917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00166-5

Wolff, S. B., Pescosolido, A. T., & Druskat, V. U. (2002). Emotional intelligence as the basis of leadership emergence in self-managing teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(5), 505–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-03-2012-0568

Wright, T. A., & Bonett, D. G. (1997). The contribution of burnout to work performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(5), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199709)18:5%3c491::AID-JOB804%3e3.0.CO;2-I

Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), 486–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486

Wright, T. A., Cropanzano, R., & Bonett, D. G. (2007). The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.93

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tahar, Y.B., Rejeb, N., Maalaoui, A. et al. Emotional demands and entrepreneurial burnout: the role of autonomy and job satisfaction. Small Bus Econ 61, 701–716 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00702-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00702-w

Keywords

- Entrepreneurial burnout

- Conservation of resources theory of stress response

- Emotional demands

- Job resources