Abstract

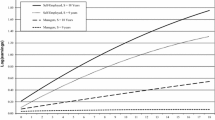

Formal education is correlated with entrepreneurial activity and success, but correlation does not indicate causation. Education and entrepreneurship are both influenced by other related factors. The current study estimates the causal effects of formal education on entrepreneurship outcomes by instrumenting for an individual’s years of schooling using cohort mean years of maternal schooling observed decades prior. We differentiate self-employment by industry employment growth and firm incorporation status. Policymakers are especially interested in entrepreneurship with the potential to create substantial employment growth. We find that an additional year of schooling increases self-employment in high-growth industries by 1.12 percentage points for women and by 0.88 percentage points for men. Education reduces the probability of male self-employment in shrinking industries. Education also increases incorporated self-employment for women and men and reduces unincorporated self-employment among men but not women. The overall probability of self-employment increases with education for women but is unaffected by education for men. The results suggest that formal education enhances entrepreneurship.

Plain English Summary

Education has long been correlated with entrepreneurial success; we provide the first evidence for a causal effect of education on high-growth industry entrepreneurship in the USA. Education also reduces self-employment in shrinking industries. Our analysis leverages differing education trends across states and ancestry groups to predict education levels for recent workers and provide causal estimates of the effect of education on entrepreneurship. We account for numerous other factors and conduct several tests to confirm that our results are stable across alternatives. Our study has important implications for researchers, policymakers, and broader society. The benefits of education are widely debated, and some worry that education is mostly about signaling and not skill development. Policymakers are also interested in how to facilitate innovative entrepreneurship that creates new products, new jobs, and economic prosperity. Our analysis indicates that education confers valuable knowledge and skills that enhance entrepreneurship and fuel societal well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On the importance of human capital, see also Glaeser et al. (1995), Simon (1998), Simon and Nardinelli (2002), Moretti (2004, 2013), Shapiro (2006), Hanushek (2013), Winters (2013, 2014, 2018), Hanushek and Woessmann (2015), Hanushek et al. (2017), and Ehrlich et al. (2018). Additional studies on the importance of entrepreneurship include Acs and Storey (2004), Wennekers et al. (2005), Acs (2006), Baumol and Strom (2007), Van Praag and Versloot (2007), Stephens and Partridge (2011), Stephens et al. (2013), and Glaeser et al. (2015).

Our framework is intentionally simplified and is not the only possible model that could be presented. For example, our model has partial conceptual overlap with some others including the Roy (1951) selection model that focuses on how differential skills affects observed earnings in different occupations via occupational self-selection. Our model is chosen to focus on the effect of education on an individual’s decision to enter entrepreneurship rather than the effect of education on entrepreneurial earnings. Our empirical analysis uses instrumental variables to estimate causal effects of education on the decision to enter entrepreneurship.

Our model assumes that there is no differential schooling requirement for paid-employment vs. entrepreneurship. This assumption is generally true in the USA during our time period, but there are some modest exceptions such as real estate agents/brokers. Other countries can have especially higher educational requirements for entry into entrepreneurship (Rostam-Afschar, 2014) that raise the cost of entering entrepreneurship and discourage some potential entrepreneurs. Rostam-Afschar (2014) finds that lowering education requirements for entrepreneurship among craftsmen in Germany increased self-employment.

The idiosyncratic cost of venturing depends on a number of factors including personality, risk aversion, impulsivity, access to capital, exposure to other entrepreneurs, developed skills, and innate ability (Blanchflower & Oswald, 1998; Lazear, 2005; Åstebro & Thompson, 2011; Guiso & Schivardi, 2011; Wang, 2012; Lindquist et al., 2015; Orazem et al., 2015; Wiklund et al., 2017; Levine & Rubinstein, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2019; Hvide & Oyer, 2019; Guiso et al., 2021). A notable literature has also documented non-monetary benefits as important factors influencing decisions to enter and persist in self-employment (Hamilton, 2000; Hurst & Pugsley, 2011; Acs et al., 2016). In particular, entrepreneurs have greater ability to control their own work conditions and schedule and many people value the freedom and control of being their own boss. Our intentionally simplified model does not explicitly incorporate non-monetary benefits, but one could think of them as reducing the idiosyncratic cost of venturing.

Specifically, the owner’s personal assets are not generally recoverable for debts of the corporation, except in cases of fraud or when the owner has explicitly assumed personal responsibility or used personal assets as collateral.

The Current Population Survey (CPS) has largely similar information except it does not include birth state, which prevents one from using the CPS to conduct a similar analysis. As discussed below, our identification strategy relies on linking cohort level maternal education via birth state, birth year, and ancestry group from the 1980 and 1990 decennial censuses to the 2006–2019 ACS.

We have no information on biological parents living outside the child’s household.

The decennial censuses and ACS are independent random samples, so we are generally not observing the same individuals over time. A small percentage of individuals are included multiple times, but we have no way to identify or link them over time. With 50 states, 28 birth-years, and 12 ancestry groups, there are 16,800 potential unique combinations of birth state, birth year, and ancestry group, but 20 cells are empty in either the census or ACS data and we actually observe 16,780 unique cohort combinations in the merged data. While a few cells are relatively small, most are large. In the 1980 and 1990 Census data, the median cohort size is 1260 child observations, and more than 90 percent of cohorts have at least 100 child observations. Large cohorts allow us to compute reasonably precise averages for cohort parental characteristics.

Survey age and survey year effects are included based on expectation that they explain some portion of the variation in self-employment and improve efficiency. However, survey age and survey year effects are minimally important for our 2SLS identification strategy discussed below because they do not significantly and systematically vary across ancestry groups within birth-state × birth-year or across birth-states within ancestry × birth-year. We present robustness checks in the appendix showing that our main results are robust to excluding survey age and survey year effects.

We link industries over time using the IND1990 variable in IPUMS. See Table 6 of the Appendix for more details.

We also report 2019 employment levels and 2006–2019 percentage growth for these. We also computed the correlation between initial employment levels and employment growth by industry; the correlation is 0.19, which weakly suggests that larger industries grow moderately faster than initially smaller ones during this period.

Table 7 of the Appendix reports mean years of individual schooling (from the ACS) and mean cohort maternal schooling (from the 1980 and 1990 censuses) by ancestry group along with means for self-employment (in any industry), any employment, and annual earnings. The table shows that there are differences in mean schooling and other outcomes across ancestry groups.

We use the terms shrinking and negative growth interchangeably.

Results for the parental characteristic control variables in the 2SLS specification are reported in Table 8 of the Appendix. These are not our focus. Most of these coefficients are not significant. The main results are qualitatively robust to excluding the parental characteristic control variables.

For all 2SLS models in Table 2, less than one percent of predicted values are below zero and none exceeded one.

Some of the coefficient estimates are very close to zero (and not statistically significant), especially OLS results in column (6) and 2SLS results in column (8) of Table 2. These very small coefficients reflect a combination of factors including that the dependent variable means are relatively small (see Table 1) and that the true effects are likely zero for these particular relationships. The OLS results also include some very small standard errors, which also reflect the large sample sizes.

The ivreghdfe program uses an endogeneity test from ivreg2 (Baum et al., 2002), which is defined as the difference of two Sargan-Hansen statistics: one that treats individual schooling as exogenous and one that does not.

Individuals with very low reported schooling levels may be influenced by mental or physical impairments or other unique circumstances that we cannot observe or account for. Individuals with very high levels of schooling may also be outliers in many respects, including a willingness to incur high opportunity costs via foregone earnings while pursuing education. Ideally, our results should not be driven by individuals in the tails of the education distribution.

A few previous studies have used instrumental variables to examine effects of education on measures of entrepreneurial success including entrepreneurial income and typically find positive coefficients, but these also do not fully account for selection into self-employment (Parker & Van Praag, 2006; Iversen et al., 2011; Block et al., 2012; Fossen & Büttner, 2013; Van Praag et al., 2013; Kolstad & Wiig, 2015).

References

Acs, Z. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations: Technology. Governance, Globalization, 1(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1162/ITGG.2006.1.1.97

Acs, Z., & Storey, D. (2004). Introduction: Entrepreneurship and economic development. Regional Studies, 38, 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000280901

Acs, Z., Åstebro, T., Audretsch, D., & Robinson, D. T. (2016). Public policy to promote entrepreneurship: A call to arms. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-016-9712-2

Altonji, J. G., Arcidiacono, P., & Maurel, A. (2016). The analysis of field choice in college and graduate school: Determinants and wage effects. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 5, 305–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63459-7.00007-5

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton Univ Pr. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400829828

Åstebro, T., & Bernhardt, I. (2005). The winner’s curse of human capital. Small Business Economics, 24(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-005-3097-Y

Åstebro, T., & Thompson, P. (2011). Entrepreneurs, jacks of all trades or hobos?. Research Policy, 40(5), 637–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESPOL.2011.01.010

Åstebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and misfits: Self-employment and labor market frictions. Management Science, 57(11), 1999–2017. https://doi.org/10.1287/MNSC.1110.1400

Baum, C.F., Schaffer, M.E., & Stillman, S. (2002). IVREG2: Stata module for extended instrumental variables/2SLS and GMM estimation. Statistical Software Components S425401, Boston College Department of Economics, revised 26 Jun 2020. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s425401.html

Baumol, W. J., & Strom, R. J. (2007). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(3–4), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/SEJ.26

Becker, G. S., Hubbard, W. H. J., & Murphy, K. M. (2010). Explaining the worldwide boom in higher education of women. Journal of Human Capital, 4(3), 203–241. https://doi.org/10.1086/657914

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/209881

Block, J. H., Hoogerheide, L., & Thurik, R. (2012). Are education and entrepreneurial income endogenous? A Bayesian analysis. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/2157-5665.1051

Block, J. H., Hoogerheide, L., & Thurik, R. (2013). Education and entrepreneurial choice: An instrumental variables analysis. International Small Business Journal, 31(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242611400470

Buenstorf, G., Nielsen, K., & Timmermans, B. (2017). Steve Jobs or no jobs? Entrepreneurial activity and performance among Danish college dropouts and graduates. Small Business Economics, 48(1), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-016-9774-1

Cai, Z., Stephens, H. M., & Winters, J. V. (2019). Motherhood, migration, and self-employment of college graduates. Small Business Economics, 53(3), 611–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-019-00177-2

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F. M., Kritikos, A., & Wetter, M. (2015). The gender gap in entrepreneurship: Not just a matter of personality. Cesifo Economic Studies, 61(1), 202–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/CESIFO/IFU023

Chierchia, G., Piera Pi-Sunyer, B., & Blakemore, S. J. (2020). Prosocial influence and opportunistic conformity in adolescents and young adults. Psychological Science, 31(12), 1585–1601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620957625

Correia, S. (2017). reghdfe: Stata module for linear and instrumental-variable/gmm regression absorbing multiple levels of fixed effects. Statistical Software Components s457874, Boston College Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457874.html

Correia, S. (2018). ivreghdfe: Stata module for extended instrumental variable regressions with multiple levels of fixed effects. Statistical Software Components S458530, Boston College Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s458530.html

Dunn, T., & Holtz-Eakin, D. (2000). Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: Evidence from intergenerational links. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2), 282–305. https://doi.org/10.1086/209959

Ehrlich, I., Li, D., & Liu, Z. (2017). The role of entrepreneurial human capital as a driver of endogenous economic growth. Journal of Human Capital, 11(3), 310–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/693718

Ehrlich, I., Cook, A., & Yin, Y. (2018). What accounts for the US ascendancy to economic superpower by the early twentieth century? The Morrill Act–human capital hypothesis. Journal of Human Capital, 12(2), 233–281. https://doi.org/10.1086/697512

Fossen, F. M. (2012). Gender differences in entrepreneurial choice and risk aversion – A decomposition based on a microeconometric model. Applied Economics, 44(14), 1795–1812. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.554377

Fossen, F. M., & Büttner, T. J. M. (2013). The returns to education for opportunity entrepreneurs, necessity entrepreneurs, and paid employees. Economics of Education Review, 37, 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONEDUREV.2013.08.005

Gennaioli, N., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2013). Human capital and regional development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), 105–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/QJE/QJS050

Glaeser, E. L., Scheinkman, J. A., & Shleifer, A. (1995). Economic growth in a cross-section of cities. Journal of Monetary Economics, 36(1), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(95)01206-2

Glaeser, E. L., Kerr, S. P., & Kerr, W. R. (2015). Entrepreneurship and urban growth: An empirical assessment with historical mines. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(2), 498–520. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_A_00456

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2008). The Race between Education and Technology. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9x5x

Goldin, C., Katz, L. F., & Kuziemko, I. (2006). The homecoming of American college women: The reversal of the college gender gap. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(4), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1257/JEP.20.4.133

Gould, E. D., Simhon, A., & Weinberg, B. A. (2020). Does parental quality matter? Evidence on the transmission of human capital using variation in parental influence from death, divorce, and family size. Journal of Labor Economics, 38(2), 569–610. https://doi.org/10.1086/705904

Guiso, L., & Schivardi, F. (2011). What determines entrepreneurial clusters? Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(1), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1542-4774.2010.01006.X

Guiso, L., Pistaferri, L., & Schivardi, F. (2021). Learning entrepreneurship from other entrepreneurs? Journal of Labor Economics, 39(1), 135–191. https://doi.org/10.1086/708445

Habibov, N., Afandi, E., & Cheung, A. (2017). What is the effect of university education on chances to be self-employed in transitional countries? Instrumental variable analysis of cross-sectional sample of 29 nations. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(2), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11365-016-0409-4

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/262131

Hamilton, B. H., Papageorge, N. W., & Pande, N. (2019). The right stuff? Personality and Entrepreneurship. Quantitative Economics, 10(2), 643–691. https://doi.org/10.3982/QE748

Hanushek, E. A. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of Education Review, 37, 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONEDUREV.2013.04.005

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2015). The Knowledge Capital of Nations: Education and the Economics of Growth. MIT Press.

Hanushek, E. A., Ruhose, J., & Woessmann, L. (2017). Economic gains from educational reform by US states. Journal of Human Capital, 11(4), 447–486. https://doi.org/10.1086/694454

Hogendoorn, B., Rud, I., Groot, W., & Maassen van den Brink, H. (2019). The effects of human capital interventions on entrepreneurial performance in industrialized countries. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(3), 798–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOES.12308

Hurst, E., & Pugsley, B. W. (2011). What do small businesses do? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 43(2), 73–142.

Hvide, H. K., & Oyer, P. (2019). Dinner table human capital and entrepreneurship (No. w24198). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/W24198

Iversen, J., Malchow-Møller, N., & Sørensen, A. (2011). The returns to education in entrepreneurship: Heterogeneity and non-linearities. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 1(3), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.2202/2157-5665.1001

Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2015). Education and entrepreneurial success. Small Business Economics, 44(4), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-014-9621-1

Koumenta, M., Pagliero, M., & Rostam‐Afschar, D. (2020). Occupational licensing and the gender wage gap. CEPR Discussion Papers 15338, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers. https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=15338

Lazear, E. P. (2005). Entrepreneurship. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 649–680. https://doi.org/10.1086/491605

Le, A. T. (1999). Empirical studies of self-employment. Journal of Economic Surveys, 13(4), 381–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00088

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 963–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/QJE/QJW044

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2018). Selection into entrepreneurship and self-employment (No. w25350). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/W25350

Lindquist, M. J., Sol, J., & Van Praag, M. (2015). Why do entrepreneurial parents have entrepreneurial children? Journal of Labor Economics, 33(2), 269–296. https://doi.org/10.1086/678493

Lofstrom, M., Bates, T., & Parker, S. C. (2014). Why are some people more likely to become small-businesses owners than others: Entrepreneurship entry and industry-specific barriers. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 232–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2013.01.004

Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

Marvel, M. R., Davis, J. L., & Sproul, C. R. (2016). Human Capital and Entrepreneurship Research: A Critical Review and Future Directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(3), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/ETAP.12136

Masakure, O. (2015). Education and entrepreneurship in Canada: Evidence from (repeated) cross-sectional data. Education Economics, 23(6), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2014.891003

Moretti, E. (2004). Estimating the social return to higher education: Evidence from longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional data. Journal of Econometrics, 121(1–2), 175–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JECONOM.2003.10.015

Moretti, E. (2013). The New Geography of Jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Murphy, K. M., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1991). The allocation of talent: Implications for growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 503–530. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937945

Noseleit, F. (2014). Female self-employment and children. Small Business Economics, 43(3), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-014-9570-8

Orazem, P. F., Jolly, R., & Yu, L. (2015). Once an entrepreneur, always an entrepreneur? The impacts of skills developed before, during and after college on firm start-ups. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 4(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40172-015-0023-7

Parker, S. C. (2004). The Economics of Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. C. (2018). The Economics of Entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. C., & Van Praag, C. M. (2006). Schooling, Capital Constraints, and Entrepreneurial Performance. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 24(4), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1198/073500106000000215

Patrick, C., Stephens, H., & Weinstein, A. (2016). Where are all the self-employed women? Push and pull factors influencing female labor market decisions. Small Business Economics, 46(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-015-9697-2

Riphahn, R. T., & Schwientek, C. (2015). What drives the reversal of the gender education gap? Evidence from Germany. Applied Economics, 47(53), 5748–5775. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2015.1058906

Robinson, P. B., & Sexton, E. A. (1994). The effect of education and experience on self-employment success. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90006-X

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5 Part 2), S71–S102.

Rostam-Afschar, D. (2014). Entry regulation and entrepreneurship: A natural experiment in German craftsmanship. Empirical Economics, 47(3), 1067–1101. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00181-013-0773-7

Roy, A. D. (1951). Some thoughts on the distribution of earnings. Oxford Economic Papers, 3(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/OXFORDJOURNALS.OEP.A041827

Ruggles, S., Flood, S., Goeken, R., Grover, J., Meyer, E., Pacas, J., and Sobek, M., (2019). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series USA: Version 9.0 . Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V9.0.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Transaction Publishers.

Shapiro, J. M. (2006). Smart cities: Quality of life, productivity, and the growth effects of human capital. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(2), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST.88.2.324

Shinnar, R. S., Giacomin, O., & Janssen, F. (2012). Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions: The role of gender and culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 465–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6520.2012.00509.X

Simoes, N., Crespo, N., & Moreira, S. B. (2016). Individual determinants of self-employment entry: What do we really know? Journal of Economic Surveys, 30(4), 783–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOES.12111

Simon, C. J. (1998). Human capital and metropolitan employment growth. Journal of Urban Economics, 43(2), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1006/JUEC.1997.2048

Simon, C. J., & Nardinelli, C. (2002). Human capital and the rise of American cities, 1900–1990. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 32(1), 59–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-0462(00)00069-7

Stephens, H. M., & Partridge, M. D. (2011). Do entrepreneurs enhance economic growth in lagging regions? Growth and Change, 42(4), 431–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-2257.2011.00563.X

Stephens, H. M., Partridge, M. D., & Faggian, A. (2013). Innovation, entrepreneurship and economic growth in lagging regions. Journal of Regional Science, 53(5), 778–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/JORS.12019

Unger, J. M., Rauch, A., Frese, M., & Rosenbusch, N. (2011). Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2009.09.004

Van der Sluis, J., Van Praag, M., & Vijverberg, W. (2008). Education and entrepreneurship selection and performance: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22(5), 795–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-6419.2008.00550.X

Van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 351–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-007-9074-X

Van Praag, M., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Van der Sluis, J. (2013). The higher returns to formal education for entrepreneurs versus employees. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-012-9443-Y

Wang, S. Y. (2012). Credit constraints, job mobility, and entrepreneurship: Evidence from a property reform in China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(2), 532–551. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_A_00160

Wellington, A. J. (2006). Self-employment: The new solution for balancing family and career? Labour Economics, 13(3), 357–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LABECO.2004.10.005

Wennekers, S., Van Wennekers, A., Thurik, R., & Reynolds, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-005-1994-8

Wiklund, J., Yu, W., Tucker, R., & Marino, L. D. (2017). ADHD, impulsivity and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(6), 627–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2017.07.002

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self–efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6520.2007.00179.X

Winters, J. V. (2013). Human capital externalities and employment differences across metropolitan areas of the USA. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(5), 799–822. https://doi.org/10.1093/JEG/LBS046

Winters, J. V. (2014). STEM graduates, human capital externalities, and wages in the U.S. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 48, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.REGSCIURBECO.2014.07.003

Winters, J. V. (2015). Estimating the returns to schooling using cohort-level maternal education as an instrument. Economics Letters, 126, 25–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONLET.2014.11.001

Winters, J. V. (2018). Do higher levels of education and skills in an area benefit wider society? IZA World of Labor. https://doi.org/10.15185/IZAWOL.130

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 6.

Table 7.

Table 8.

Table 9.

Table 10.

Table 11.

Table 12.

Table 13.

Table 14.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, K., Winters, J.V. Does education enhance entrepreneurship?. Small Bus Econ 61, 717–743 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00701-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00701-x