Abstract

Current research has shown that entrepreneurial exit is driven by individual- and firm-level antecedents. We draw from neoinstitutional theory and propose that contextual factors affect family succession intentions as opposed to family-external exit intentions and theorize how regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive institutional pillars affect exit intentions in the context of transition economies—a special case of emerging economies with no path dependence related to an entrepreneurial exit—characterized by institutional voids, which are filled in by the national culture. We argue and find—analyzing a sample of 222 Polish SME founders’ survey responses—that labor market development decreases, normative pressure of reference groups increases, and paternalistic leadership style decreases family succession intentions. This study contributes to the literature about entrepreneurial exit, family firm succession, and neoinstitutional theory.

Plain English Summary

Many firm founders intend to hand over their firms to their children in emerging economies. Why? National culture matters in young economies. At some time, all firm founders must plan to hand over their firm to a younger successor, who can be a family member or someone who is not from the family. We study how national culture makes founders prefer either family members or others as successors when they exit their firm. We suggest that institutions are particularly important drivers of exit choices in emerging economies and that national culture becomes a primary reference point for founders in those countries. To test our hypotheses, we collected survey responses from 222 Polish firm founders. We show that inefficient labor markets and a specific, paternalistic, leadership style increase preference for family-external exit. Peer pressure, however, increases the preference for family succession. This study’s findings show that, in contrast to developed economies, family succession is still preferred in emerging economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

All founders of firms will eventually have to make a decision concerning their own entrepreneurial exit (DeTienne, 2010), which completes the full cycle of the entrepreneurial process (Aldrich, 2015). Entrepreneurial exit is a “process by which the founders of privately held firms leave the firm they helped to create; thereby removing themselves, in some degree, from the primary ownership and decision-making structure of the firm” (DeTienne, 2010, p. 204). In addition to liquidation, firm founders face options such as initial public offerings (IPOs), sales (independent sales or acquisitions), and buy-outs (management buy-outs or buy-ins) (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; DeTienne & Wennberg, 2015). In addition to family-external exits, founders can also opt for a family-internal exit, which marks the first family succession (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012) and is a synchronized exit and entry process of incumbent and successor (Nordqvist et al., 2013). Exit affects the individual founder, the firm, the industry, and even the economy in which the firms operate (DeTienne, 2010) and has been studied in the entrepreneurial-exit and family-business-succession literature, which highlight the influence of various individual- and firm-level factors affecting exit intentions (e.g.Balcaen et al., 2012; Chrisman et al., 2015; De Massis et al., 2016; Wennberg et al., 2010).

However, the extant literature remains heavily decontextualized (Jennings et al., 2013; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004; Nordqvist et al., 2013; Sharma, 2004), even though the influence of institutional factors, which are theorized as social constructs (Heugens & Lander, 2009) and exerting pressures that must be complied with, might be particularly important in emerging economies (Iwasaki et al., 2021). These economies are characterized by institutional voids (Mair & Marti, 2009), which likely affect the cognition and behaviors of firm founders. Thus, we ask the following research question: How do institutions in emerging economies influence founders’ entrepreneurial exit intentions towards family succession?

To answer this research question, we combine the entrepreneurial exit and family business literature, as well as neoinstitutional theory, to hypothesize how regulative institutions (labor market development), normative institutions (normative pressure), and cultural-cognitive institutions (benevolent paternalistic leadership style) influence the exit intentions of firm founders. We set the this study in the context of a transition economy—a special case of an emerging economy that transitions from “a centrally planned economy toward freer markets and increased entrepreneurship” (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2010, p. 531), in which there are no routines or path dependence (Sydow, et al., 2009) related to an entrepreneurial exit—and test the proposed hypotheses based on a sample of 222 Polish founders of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), applying multiple logistic regression analyses.

We contribute to the current research in multiple ways. First, with the analysis of institutional antecedents to entrepreneurial exit, this study investigates the behavior patterns “exhibited by entrepreneurs […] in a variety of […] regional, national and cultural settings” (Ucbasaran et al., 2001, p. 16) and provides a contextual, socially constructed analysis of the exit and family succession intentions and their specific drivers. Second, this study supports the notion that the application of institutional theory in the context of emerging economies is preeminent (Hoskisson et al., 2000) by empirically showing that exit intentions are also influenced by noneconomic factors such as culture (DeTienne, 2010). Third, by focusing on firm founders and applying the notion of an entrepreneurial exit to the first family succession (i.e., from founder to next generation), this study integrates the entrepreneurship and family business literature streams.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Entrepreneurial exit and family succession intentions

Entrepreneurial exit—the intentionally planned exit (Wennberg et al., 2010) by firm founders—may lead to various outcomes. Exit affects the individual firm, the industry, and even the economy in which the firms operate (DeTienne, 2010). For firm founders, the particular choice of family-external exit or family succession may lead to various outcomes. Specifically, financial reward-based exit strategies, such as sale to an individual or another firm, offer potentially higher financial returns (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; DeTienne & Chirico, 2013), while family successions—a stewardship-based exit strategy—provide “continuity and care of the firm, the family, and the employees” (DeTienne & Chirico, 2013, p. 1300). Indeed, firms that went through family-external exit showed higher short-term performance; however, firms that stayed in the hands of the family had higher survival rates (Wennberg et al., 2011).

However, knowledge about when firm founders develop family-external exit intentions versus family succession intentions is limited. Previous entrepreneurship research has shown that some founders develop family-external exit intentions because they “favor personal financial returns over other goals” (DeTienne & Chirico, 2013, p. 1300) and could be motivated by a wish to “free up resources to serve another purpose” (DeTienne & Chirico, 2013, p. 1300), thus managing their businesses with the intention to cash in on their hard work and let go of their ownership (Wennberg et al., 2011). The family business literature shows that founders develop family succession intentions as they wish to pursue noneconomic goals, which are cumulatively called nonfinancial utilities, affective endowments, or socioemotional wealth, in addition to financial goals (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2001, 2011). For these founders, a firm “constitutes a source of family income, security and pride, present and future career opportunities for family members, and a bastion for family reputation in the community” (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2008, pp. 43–44). Studying family succession intentions is important because they are a primary driver of the socioemotional wealth perceptions of family firm owners (Zellweger et al., 2012), a building block of family essence (Chrisman et al., 2012), and hence of the self-concept of family firm (Chua et al., 1999).

While the family-firm literature argues that most family businesses are founded with intentions to be family firms (Chua et al., 2004), the entrepreneurship literature treats exit intent as a temporal issue: Founders start to think about their exit once it becomes an imminent decision that is driven, for example, by retirement (Soleimanof et al., 2015). These founders also tend to adapt their preferred exit based on situational characteristics (Wennberg et al., 2010). Even though entrepreneurial exit incorporates the dual nature of exit, including ownership and management transfer,Footnote 1 the entrepreneurial literature has traditionally focused on ownership exit only (Nordqvist et al., 2013). In contrast, the family-business-succession literature tends to focus on management exit (Stamm et al., 2011).

Although the two research fields of entrepreneurship and family business have developed independently (Nordqvist & Melin, 2010), they are not contradictory (Kraus et al., 2012). In particular, the role of the founder is one of the “common denominators,” bringing those two fields together (Nordqvist & Melin, 2010). To date, the extant literature from both streams predominantly analyzed the individual- and firm-level drivers of exit (Nordqvist et al., 2013; Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014) and family succession (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004) intentions. The entrepreneurship literature looked at individual characteristics of the owner, such as age, education, industry experience (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Wennberg et al., 2010), intrinsic motivation (DeTienne & Chandler, 2010), information asymmetry (Dehlen et al., 2014; Scholes et al., 2008), and the financial situation of the firm (Balcaen et al., 2012). The family-business literature has studied successor characteristics, such as motivation and abilities (Chrisman et al., 2015); incumbent characteristics, such as emotional attachment to the firm (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008); preparation of the successor and the succession process (Dyer, 1988; Ward, 2016); attitudes towards intrafamily succession (De Massis et al., 2016); and family relations (Lansberg & Astrachan, 1994).

However, to date, the extant literature has remained heavily decontextualized and silent about the institutional embeddedness of founders. As noted by Wennberg and DeTienne (2014), “while the relationship between intentions and actual exits may be highly correlated, it may not be a strict linear relationship; rather, one in which many contextual factors shape the final outcome” (p. 7). Given the repetitive calls for research on broader contextual factors of entrepreneurial exit (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Nordqvist et al., 2013) and on the social context of succession (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004; Sharma, 2004), we address that research gap by viewing exit intentions via the lens of neoinstitutional theory.

2.2 Entrepreneurial exit and family succession in light of neoinstitutional theory

Viewing entrepreneurial exit—a set of “proactive, intentional strategies of entrepreneurs” (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012, p. 354), which is neither an indicator of success nor a failure (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016; Fang He et al., 2018; Jenkins & McKelvie, 2016) of the founder and the firm—via the lens of neoinstitutional theory embeds firm founders as the key decision-makers into a specific context, which dictates their prescribed behaviors. “Founders of organizations, while usually unique individuals, are also children of national culture,” according to Hofstede (1985, p. 349). Their cultural embeddedness is an important source of accessibility to institutional logics (Ganter et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2011)—fundamental key institutions of society such as family, community, religion, state, market, profession, and corporation (Thornton et al., 2012)—which constitute frameworks for reasoning and decision-making (Lounsbury, 2007). For example, family logic determines strategic decisions, such as downsizing in smaller organizations (Greenwood et al., 2010) or specific exit types (Ganter et al., 2014). Similarly, the succession literature argues that the succession process is “heavily influenced by cultural norms such as primogeniture, patriarchy, estate division conventions, and so on” (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004, p. 317); that family firms enact institutional pressures (Berrone et al., 2010); and that “family involvement is […] related to greater, not lesser, conformity in strategy” (Miller et al., 2013, p. 206). The literature thus concludes that family businesses “provide an excellent basis for studying how a common organizational form adapts and evolves in different institutional contexts” (Gedajlovic et al., 2012, p. 1024).

Considering the potential effect of institutions, we now briefly turn to the institutional literature. “[N]eo-institutions are seen as a socially constructed context” (Heugens & Lander, 2009, p. 61) with a high degree of resilience (Scott, 2001, p. 48) as the societal rules of the game, which guide individual behavior (North, 1990) and thus reduce uncertainty, risk, and transaction costs connected with each individual action (North, 1990). Actors must conform to institutions (Scott, 2001), and in return, they enjoy legitimacy, which secures access to valuable resources and thus yields a chance of higher financial performance, success, and survival (Leaptrott, 2005; Miller et al., 2013). In a quest for legitimacy, organizations adopt certain practices unquestionably by doing what the majority is doing (Deephouse, 1999) and inevitably resemble other organizations in their structures and strategies (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Heugens & Lander, 2009; Scott, 2013).

Neoinstitutional theory is particularly important in emerging economies that experience insufficiencies in regulative (Scott, 2001) and formal (North, 1990) institutions, such as underdeveloped capital (North, 1990) and labor markets (Mair et al., 2012), deficient legal infrastructure (Smallbone & Welter, 2006) and law enforcement (Ahlstrom et al., 2000), and the absence of physical infrastructure (Fisman & Khanna, 2004). “Situations where institutional arrangements that support markets are absent, weak, or fail to accomplish (their) role” (Mair & Marti, p. 419)—so called institutional voids—are not, however, “institutional vacuums” or “institutional tabula rasa” (Mair & Marti, 2009) but are filled in by some other institutions (Thornton et al., 2012), such as national culture, which has “a strong influence (also on family ownership) when a country has institutional voids” (Chakrabarty, 2009, p. 42). In the following section, we study three institution-related constructs that have a direct impact on the founder’s decision on the exit type (see Fig. 1 and Table 1): labor-market development, normative pressure of reference groups, and benevolent paternalistic leadership style.

3 Hypothesis development

3.1 Effect of labor market development on exit intentions

Regulative institutions, i.e., “those written or formally accepted rules and regulations, which have been implemented to make up the economic and legal set-up of a given country” (Tonoyan et al., 2010, p. 805), play an important role in emerging economies and particularly in transition economies. Together with the abandonment of centrally planned economies, national governments introduced regulative institutions, such as property rights (Woodruff, 2000) or access to finance (Block et al., 2013), which allowed for private ownership and thus entrepreneurship (Smallbone & Welter, 2006) and the initial functioning of the product, capital, and labor markets. However, entrepreneurship in such economies may still be limited by institutional constraints such as market imperfections (Hoskisson et al., 2000).

We chose labor market development as a representation of the regulative institution for two reasons. First, labor market imperfections such as the exclusion of ultrapoor individuals from participating in formal labor markets (Mair & Marti, 2009) or high dispersion in income per capita across regions (OECD, 2019a), for example, between rural and urban areas (Hoskisson et al., 2000), reflect the overall inefficiency of the state in the allocation of resources and the efforts of securing the social order; hence, they are a sign of an institutional void (Puffer et al., 2010). Second, the extant literature shows that regional income levels reflect the economic development of different geographic areas (Bird & Wennberg, 2014; Chang et al., 2008) and impact various entrepreneurial processes (Backman & Palmberg, 2015), such as the foundation of start-ups (Bird & Wennberg, 2014), the family business prevalence rate in less developed regions (Chang et al., 2008), and entrepreneurial exit (Fuentelsaz et al., 2020).

We suggest that regions with lower average salaries are characterized by a scarcity of human capital and skilled labor; thus, sourcing reliable and appropriate employees, including potential nonfamily CEOs, may be difficult. Because firms rely on human capital to achieve competitive advantages (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003), founders in underdeveloped labor markets may rely more on family capital, due to filling in the labor market institutional voids with “familiness”—“the unique bundle of resources a particular firm has because of the system’s interaction between the family, its individual members, and the business” (Habbershon & Williams, 1999, p. 11)—and thus develop family succession intentions. Also, we suggest that in regions with lower average salaries, there is a lack of financially attractive external career options for the next generation. Due to family altruism (Schulze et al., 2003a, 2003b), founders may wish to provide their offspring a stable income, or, more generally, an attractive economic situation (Wiklund et al., 2013), and thus develop family succession exit intentions. Thus, we propose the following:

-

Hypothesis 1: In emerging economies, underdevelopment of the labor market increases the founder’s family succession exit intentions.

3.2 Effect of normative pressure on exit intentions

Institutional theory’s normative institutional pillar explains how actors are guided by social obligation and logic of appropriateness (Scott, 2013), stemming from the process of social, professional, and organizational interactions (Bruton et al., 2010) with influential groups (Suchman, 1995) of stakeholders such as professional and industry organizations (Scott, 2001) but also key stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, employees, and, in the case of family businesses, the founder’s family (Leaptrott, 2005). Exogenous normative influences constitute strong social pressures that steer individual behavior (Krueger et al., 2000). Normative beliefs, which are “beliefs about the normative expectations of other people” (Ajzen, 2002, p. 665), result in perceived social pressure and are a strong predictor of behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Armitage & Conner, 2001).

For exit, normative pressure refers to the perception of founders that their reference groups would approve (or disapprove) their specific exit intention. We chose the normative pressure of reference groups as a representation of the normative institution for the following reasons. First, the family business literature has long recognized that the stakeholder context and family members’ interdependence (Arregle et al., 2007) play a critical role and that “firm survival and success often depend on an entrepreneur’s ability to establish a network of supportive relationships” (Steier, 2001, p. 262). Additionally, the entrepreneurship literature has examined social pressure, yet particularly in earlier phases of the entrepreneurial process (DeTienne, 2010; Linan & Chen, 2009). Second, the inclusion of family as a reference group reflects the calls for further investigation of entrepreneurial exit from the family embeddedness perspective (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003), business-family interface (Hsu et al., 2016), and is based on the rationale that family is a group of stakeholders who exert exceptionally strong normative pressure due to the “family codes of conduct” (Leaptrott, 2005) and family norms (such as parental altruism, parents’ desire for legacy creation, filial reciprocity and filial duty), which are elicited within the family logic (Zellweger et al., 2016).

The context of emerging economies constitutes an ideal setup because in varieties of capitalism, family matters but in a different way, depending on the institutional context. In emerging economies, “family plays an important role for all businesses, whether they are big or small and formal or informal” (Steier, 2009, p. 521). The legal or regulatory vacuum of emerging economies drives the governance focus towards families and owners (Steier, 2009). Because family in emerging economies is the source of legitimacy, firm founders face a normative social obligation stemming from interactions with reference groups, such as family, friends, customers, suppliers, and employees, to develop family succession intentions. Therefore, we propose the following:

-

Hypothesis 2: In emerging economies, normative pressure of reference groups towards family succession increases founders’ family succession intentions.

3.3 Effect of benevolent paternalistic leadership styles on exit intentions

The cultural-cognitive institutional pillar of neoinstitutional theory describes individual actors’ internal cognitive interpretative processes, shaped by the external cultural framework (Scott, 2013), which is an important source of role models for entrepreneurial identity (Gupta et al., 2008; Wyllie et al., 1956) and accessibility to institutional logics (Thornton et al., 2012). We chose the benevolent paternalistic leadership style as a representation of the cultural-cognitive institution for the following reasons. First, entrepreneurial processes (Autio et al., 2013), exit types (Ganter et al., 2014), family succession (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004), strategic divestments in family firms (Sharma & Manikutty, 2005), and intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions (Laspita et al., 2012) are impacted by cultural norms, and incumbents’ leadership styles are related to family succession (Fries et al., 2020; Marshall et al., 2006; Stavrou et al., 2005). Second, unlike in Western or more developed contexts, in which paternalism is often perceived negatively (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006), a paternalistic leadership style may be effective in emerging economies (Aycan, et al., 2000; Pellegrini et al., 2010) because it is congruent with often observed cultural elements of high-power distance, collectivism, and family as value (Aycan, et al., 2000; Hofstede & Minkov, 2010; House et al., 2004; Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006). Benevolent paternalism denotes an “individualized, holistic concern for subordinates’ personal and family wellbeing” (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2008, p. 573) and “indicates that a leader cares for subordinates” (Calabro & Mussolino, 2012, p. 13), as if they were family members (Cheng et al., 2000; Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006, 2008). Conversely, subordinates reciprocate parental authority by voluntarily showing loyalty, deference, and compliance (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2006), which may, however, be lost in case the “leaders ignored their paternalistic duties” (Pellegrini et al., 2010, p. 395).

However, some forms of family-external exits (e.g., employee buyouts) typically guarantee the founder long-term post-exit involvement in the management (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012) and the ownership (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2015) of the company and thus the continuation of their leadership style. Moreover, based on the principle of homophily (Ruef et al., 2003) and similarities in leadership styles (Westphal & Zajac, 1995), founders may choose successors who closely resemble themselves. Ironically, these may often not be children, who typically have a different set of genes and therefore also personalities and leadership styles due to a natural mixture of genes and the wildcard effect explained by social biologists (Nixon & Wheeler, 1992), which may lead to relational conflicts, rebellious successions (Miller et al., 2003), and suppression of family succession intentions (De Massis et al., 2008). This phenomenon is due to a lack of sound understanding between an incumbent and a successor (Venter et al., 2005) based on “willingness of each party to acknowledge the other’s achievements” (Lansberg & Astrachan, 1994, p. 43), which may be difficult to achieve in patriarchic cultures, where “ultimate authority resides with the senior generation” (Sharma & Manikutty, 2005, p. 299) and where the outcomes of paternalism—job satisfaction and organizational commitment of the followers (Pellegrini & Scandura, 2008)—are consistent with the outcomes of homophily, “greater level of interpersonal attraction, trust, and understanding, and, consequently, greater levels of social affiliation” (Ruef et al., 2003, p. 198). Thus, we propose the following:

-

Hypothesis 3: In emerging economies, a benevolent paternalistic leadership style decreases founders’ family succession intentions.

4 Methods

4.1 Context of Poland as a transition economy

To test the proposed hypotheses, a survey was conducted among the Polish founders of SMEs, which are defined as firms with fewer than 500 employees.Footnote 2 The context of Poland as an emerging economy is an appropriate setting to study entrepreneurial exit for the following reasons. First, Poland transitioned from a planned economy to a market economy, a process that started rapidly in the late 1980s as a result of a political change, the collapse of communism, and the unification of Europe after the fall of Berlin Wall. Transition economies (International Monetary Fund, 2000, 2021) such as European Union Eastern European countries constitute a group of middle-level income emerging economies with relative “ease of doing business” (The World Bank Group, 2019), indicating that the results of this study may be generalizable to other middle-level income emerging economies, such as BRIC, ASEAN-5, or South Africa.

Second, transition economies provide an interesting context to study entrepreneurship because economic freedom is positively associated with entrepreneurial activity (Bennett, 2020). In Poland, after 50 years of state-controlled ownership with only fragmented private ownership, new regulative institutions were implemented overnight to foster entrepreneurship. One of them was the Economic Freedom Act of 1988, which encouraged the establishment of private businesses with simplified procedures and initially completed corporate tax releases (Kowalewski et al., 2010). According to Smallbone and Welter (2006), the “number of private firms increased sharply,” facilitated by the removal of legal barriers to market entry, combined with the low intensity of competition and the existence of opportunities to earn monopoly profits (p. 200). More than half a million new enterprises were registered in 1988–1989. Nearly 2.1 million privately owned firms registered in Poland, out of which 98.8 percent fall into the SME category (Central Statistical Office of Poland, 2019). A few decades after the economic and political transformation, when there is still a lack of “best practices,” routines and organizational path dependence (Sydow, et al., 2009), entrepreneurial exit and first family succession become increasingly important phenomena, as many founders intentionally plan to exit the business (Wennberg et al., 2010).

Third, contemporary Poland is still characterized by institutional voids, as in other emerging markets, which can impact the efficient functioning of the product, capital, and labor markets and simultaneously strengthen the importance of culture as a reference point. In Poland, the inefficiency of the courts in the settlement of legal case, where judges handle up to 1150 cases per year, leading to the long time required to dispute settling (Bełdowski et al., 2010) and the inefficiency of governments in the management of public funds or bureaucratic corruption (Jain, 2001) are just a few examples. According to Transparency International in the Corruption Perception Index, in which scores can range from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean), Poland scored 61 points in 2014, which positions it above the ex-Soviet bloc countries that are not part of the European Union, and on a high end of other Eastern European countries from within the European Union (Transparency International, 2014). In the “ease of doing business” ranking of the World Bank Group, Poland is ranked 33 (ranking ranges from 1 to 190), primarily due to relative burdens related to starting a business (rank 121), paying taxes (rank 69), getting electricity (rank 58), protecting minority investors (rank 57), enforcing contracts (rank 53), dealing with construction permits (rank 40), and registering property (rank 41) (The World Bank Group, 2019). The World Economic Forum in Global Competitiveness rankings reports that in Poland, “the business sector remains very concerned about some aspects of the institutional framework, including the government inefficiencies […] in particular a high burden of government regulation” (World Economic Forum, 2013–2014) as well as “rather inefficient legal framework for settling business disputes […], and difficulties in obtaining information on government decisions for business” (World Economic Forum, 2014–2015).

Fourth, in the context of emerging economies, including Poland’s, national culture carries a strong notion of family as a social value (Hofstede Insights; n.d.) and makes it an ideal setup to test the effect of institutional voids filled in by normative and cultural-cognitive institutions. The role of national culture is additionally strengthened by the fact that it may be the only reference point for firm founders in transition economies, with no routines or path dependence (Sydow et al., 2009) regarding entrepreneurial exit. This result is in line with previous research, which shows that a legal or regulatory vacuum in emerging economies drives the governance focus towards family (Steier, 2009). In particular, Poland was positioned among the family-in category in an international study, which investigated owner-managers’ attitudes towards family and business (Birley, 2001) and classified 16 countries into family-out, family-in, and family-business juggler clusters. Also, Poland is a society in which family firms enjoy high legitimacy in the eyes of a country’s general population; on a scale from 0 to 1, which measures the degree of family-legitimizing environment, Poland reaches 0.71 (Berrone et al., 2020; Duran, 2015).

4.2 Research procedure and sample

To create the sample, we used a snowballing technique based on the rationale that firm founders are a hidden population (Bonaccorsi et al., 2006; Faugier & Sargeant, 1997; McGee et al., 2009) and are difficult to identify a priori (Schulze et al., 2003a, 2003b; Vandekerkhof et al., 2018) because a registry of Polish firm founders does not exist. First, key informants were identified at conferences within various family business and entrepreneurs’ networks, associations, and circles, and a project partnership was established with the leading Polish Institute for Family Business (IBR). Second, more firm founders were identified either by referral (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981; Gentile-Lüdecke et al., 2020; Saunders et al., 2008) or in various databases. An invitation to take part in the research project was sent to them, and it included a link to the electronic survey. The survey was initially developed in English and then translated into Polish. After implementing minor comments regarding the order and the wording of questions, as suggested by three firm founders who reviewed the survey, back translation was performed and showed no major differences between the Polish and English versions.

The average response time was approximately 25 min, and the total number of responses amounted to 788: Early drop-outs were excluded (remaining sample size: 696 respondents), and non-founders of SMEs were removed (remaining sample size: 551). After the listwise deletion of responses with missing data on one of the variables used in the regression, the remaining sample size was 222. Because the number of excluded founders was high (329 records), we also assessed the risk of nonresponse bias. Respondents who answered the questionnaire fully and were included in the analysis were coded 1, as opposed to respondents who had a missing value on any variable (coded 0). Comparing the means and standard deviations of selected statistics, namely, firm age and size, revealed some minor differences. Those who completed the survey fully were founders of marginally older (founding year: 1994) and larger firms (size: 25 employees) compared to those who did not complete the survey (founding year, 1997; size, 24).

4.3 Data and models

The representativeness of the sample compared to the total population of Polish SME founders was assessed by comparing selected descriptive characteristics of the founder and the firm. Year of founder’s birth (mean 1958, SD 8.2), the year the firm was founded (mean 1994, SD 6.3), and the number of employees (mean 25.2, SD 50.5) were compared with the corresponding characteristics of samples used in comparable studies. The average age of the founders in that sample amounted to 56 years and was marginally higher than the average age of the founders in a sample of Polish family firms (mean: 51 years) studied by Safin and Pluta (2014) and comparable to the average age of the founders in a sample of Polish family firms examined by Lewandowska et al. (2013), in which 70 percent of incumbents were between 50 and 60 years old. The average age of the firm in that sample amounted to 20 years and was comparable to the average age of the firms reported in previously published work of Polish family firms (Lewandowska et al., 2013: 20.5 years; Safin et al., 2014: 24 years). The size of the firm (i.e., the number of employees) in this sample amounted to 25 people and was higher compared to samples from other studies that investigated microenterprises (Lewandowska et al. (2013), 11 employees; Safin et al. (2014), 10 employees; Surdej and Wach (2010), 17 employees).

Common method bias is often considered to be the primary source of measurement errors (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, we undertook several steps to mitigate the common method bias following the suggestions of Podsakoff et al. (2003). We ensured complete confidentiality to the respondents, which enhances the probability of honest answers. We also ensured that different variables were spread over the survey. Finally, questions were designed to be simple, specific, and concise. Additionally, we ran Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Out of 11 variables (1 DV, 3 IV, 7 CV), five variables had an eigenvalue greater than 1.0, with the first factor accounting for 16.48 percent, indicating that no single factor accounts for the majority of the variance and providing initial evidence that common method bias is not a major concern. Additionally, we conducted a marker variable test (Lindell & Whitney, 2001) investigating the correlation between a dependent variable and a variable uncorrelated to the dependent variable, the so-called marker variable (Homburg et al., 2010). This variable was then used to correct the correlation matrix for common method bias. We assessed the correlation between the influence of the superiority of self-employment over being an employeeFootnote 3 (marker variable) and the proposed dependent variable, exit intentions. The marker variable shows a very weak correlation with the dependent variable (r = 0.001), which underscores the validity of the marker variable (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). The significance of correlations between dependent and independent variables does not change, which provides further evidence that common method bias is not present (Van Doorn & Verhoef, 2008).

We also examined the variance inflation factors (VIFs) (Hair et al., 2006). We conclude that multicollinearity is not a major concern because the maximum variance inflation factor (VIF) for the unstandardized variables in this study is 1.25.

4.4 Measures

4.4.1 Dependent variable

The dual character of entrepreneurial exit—management and ownership (DeTienne, 2010)—was embraced by simultaneous analysis of both dimensions for two reasons. First, in small privately held companies, ownership and management are typically united, and transfers typically go hand in hand (Carney, 2005). Second, mixed exit routes—those involving either management or ownership exit—are not common among SME founders due to economic reasons (employment of a nonfamily CEO requires financial resources) or are merely a temporary solution (family CEO in case of a firm’s sale).

Exit intentions were conceptualized as family succession intentions when there was an intention to exit from both management and ownership within the family and as a family-external intention otherwise. Therefore, for every respondent, we analyzed the intention on the management exit (family succession vs. family-external exit) and ownership exit (family succession vs. family-external exit) and compounded a new binary variable coded 1 (when both management and ownership exit intentions were family succession intentions) and family-external exit coded 0 (otherwise). Management exit was measured by asking “Who will take over the management in the company?” and was coded 1 for family succession intentions (i.e., family member(s), including direct descendants (i.e., daughters and sons) as well as other relatives by blood or law (i.e., spouse, other family relatives such as niece or nephew)) and 0 for family-external exit (i.e., transfer of leadership to other individuals to whom the founder does not have familial ties: these could be employees, friends, business partners, or external managers). Such conceptualization is in line with other studies devoted to entrepreneurial exit types (Dehlen et al., 2014; Wennberg et al., 2011). As opposed to unintentional exits (Wennberg et al., 2010), resulting from unforeseen factors (Chirico et al., 2020), such as bankruptcy (Balcaen et al., 2012), this study analyzes deliberate entrepreneurial exits (Wennberg et al., 2010), for which founders plan intentionally. Therefore, respondents who indicated that their firm was going to be closed and those who were undecided, as well as all ambiguous cases (16 cases in total), were excluded. Similarly, ownership exit was measured by asking the question “What will occur to the ownership of the company?” and was coded 1 for family succession (same definitions as above) and 0 for family-external exit (MBO, MBI, IPO, sales to private equity or any other company or investor), following the extant literature (Wiklund et al., 2013). Respondents who indicated that their firm was going to be closed, and those who were undecided (5 cases in total) were excluded.

4.4.2 Independent variables

The model used in this study included three independent variables: labor market development, normative pressure of reference groups, and benevolent paternalistic leadership style. Labor market development was measured by average annual salaries and wages, a statistic commonly used in the assessment of the labor market (OECD, 2019b). For each of the 16 administrative districts of Poland, the regional average salary level was divided by the national average, both sourced from the official database of the governmental agency for statistics (Central Statistical Office of Poland, 2014). Regional salary levels as a percentage of the national average were then assigned to every respondent based on their answer about the region in which the firm was registered.

Following previous research on subjective norms (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Sieger & Monsen, 2015), the normative pressure of reference groups was measured on a multi-item scale, where respondents were asked “How would different persons/groups react to management/ownership succession to a person from the family?”, and was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very negatively; 5 = very positively). The five reference groups were family members; employees; important customers and suppliers; owners of family firms in the network; and the circle of friends. The normative pressure of reference groups was calculated as an average with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93, showing a very good level of scale reliability.

Benevolent paternalistic leadership style was measured by asking the question “How would you describe your managerial style?” and calculated as an average of three items: “I am interested in different aspect of my employees’ lives,” “I give advice to my employees as if I were an elder family member,” and “I try my best to help my employees whenever they need help on issues outside work.” All items had a 5-point response format (1 = definitely no; 5 = definitely yes) and were based on Cheng et al. (2000) and Pellegrini and Scandura’s (2006) studies on paternalistic leadership style. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) was 0.81.

4.4.3 Control variables

We included seven control variables in the proposed models. Inadequate financial resources to perform family succession have been noted as factors that may prevent family succession (De Massis et al., 2008). To mitigate the phenomenon that the results of this study were driven by a lack of appropriate financing for potential family succession, we included the variable feasibility of succession (“At least one of my children can sustain the burden of financing the succession,” measured on a 5-point Likert scale). Firm age is an important driver of the emotional attachment of the founder leading to development of various psychological barriers to exit (Weesie & van Teeffelen, 2015) and problems with “letting go” (Sharma et al., 2001) which enhances the probability of developing family succession intentions (Dehlen et al., 2014) and is considered to be a traditional control variable in the exit literature (Wiklund et al., 2013). We included firm age rather than founder age because (1) we conceptualized exit, the proposed dependent variable, at the firm level (Cefis, et al., 2021) and (2) firm age and founder age showed a high correlation. Financial performance (“How would you rate your company’s performance compared with your competitors over the last three years in (i) sales growth and (ii) profitability growth?”, measured on a 5-point Likert scale with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75) was included as a control because firm performance is related to the entrepreneurial exit type (Wennberg et al., 2010, 2011); thus, distressed firms go through distinct exit routes (Balcaen et al., 2012). We built on previous arguments on the influence of the perception of the firm’s performance on willingness to sell the company (Kammerlander, 2016). The industry in which the firm is active is a proxy for risk and economic outlook that may, as a consequence, make the firm very attractive for both family successors and potential external investors. Similar to previous studies of family succession (e.g., Zellweger et al., 2012) and exit types (Chirico et al., 2020; Wennberg et al., 2010; Wiklund et al., 2013) and exit rates (Stam et al., 2010), we, hence, also included industry as a control variable (coded 0 for the secondary sector and 1 for the tertiary sector). Firm size, a variable frequently used in studies on exit and succession (e.g., Chirico et al., 2020; Richards et al., 2019; Wennberg et al., 2011; Wiklund et al., 2013; Zellweger et al., 2012), was captured as the number of full-time employees. The number of family employees in the firm was also controlled for, as involvement of family members in the firm might shape family succession intentions (Chrisman, et al., 2012; De Massis et al., 2016; Hoy & Verser, 1994), exit type (Chirico et al., 2020), and the choice of the successor (Richards et al., 2019). The education level of firm founders reflects cognitive skills (Westphal & Zajac, 1995) and has been shown to be an important driver of entrepreneurial exit (Amaral et al., 2007) and the incumbent’s choice of the successor (Richards et al., 2019), particularly in the context of emerging economies with an institutional void of inadequate education and training (Khanna & Palepu, 1997).

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive data

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix of the variables included in the proposed model. Only low and moderate correlations are observed.

Firm founders, 79% men and 21% women, were on average 57 years old, and most (72%) had a master’s degree. Their firms were distributed among all regions of Poland, were on average 21 years old (founders were on average 36 years old at the time of firm founding), and employed on average 25 employees. Most firms were active in the tertiary sector (54%) in industries such as retail and sale (22%). In line with prior studies (Surdej & Wach, 2010), most founders indicated family-succession-exit intentions (86.6%), which differentiates emerging markets from developed markets (for example, in Western European countries), in which family succession accounts for only approximately 40 percent (Bennedsen et al., 2007; Bluhm & Martens, 2011; Halter & Schroeder, 2011).

5.2 Results of binary logistic regression

Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to predict founders’ intention towards family succession compared to a family-external exit. The results of the binary logistic regression are shown in Table 3.

Model 1 includes only the control variables and was significant (X2 = 30.92, df = 7, p < 0.000). The feasibility of succession shows, as expected, a positive and significant effect on the logarithmic odds of family succession intentions (β = 0.627; p = 0.001). The number of family employees had a marginally positive effect (β = 0.362; p = 0.066), and the founder’s education level had a marginally negative effect (β = − 1.053; p = 0.048) on the logarithmic odds of family succession intentions. Firm age, financial performance, industry, and firm size were insignificant, which might also be caused by their mutual correlations (Table 2).

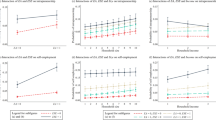

In model 2, the three independent variables were simultaneously entered into the analysis. The model was significant (X2 = 59.43, df = 10, p < 0.000), Nagelkerke’s R2 reached 44 percent, and the likelihood statistics improved from 86.8 percent to 89.6 percent (AIC improved from 162.36 to 130.82). Labor market development affected the logarithmic odds of family succession intentions in a significant (p = 0.040) and negative way (β = − 3.559); thus, H1 was confirmed. The normative pressure of reference groups affected the logarithmic odds of family succession intentions in a significant and positive way (β = 1.746; p = 0.000), confirming H2. Benevolent paternalistic leadership style affected the logarithmic odds of family succession in a marginally negative way (β = − 0.572; p = 0.054); thus, H3 is only marginally confirmed (Table 3).

5.3 Robustness tests

We ran several robustness tests to ensure the reliability of the results. First, we decomposed the reference groups of normative pressure (i.e., family members, employees, important customers and suppliers, owners of family firms in the network, circle of friends) and considered every group separately. Results are shown to be robust and indicate that Hypothesis 2 remains stable in terms of size, direction, and significance for each single reference group.

Second, we decomposed the proposed dependent variable, exit intentions, into management exit intentions and ownership exit intentions (Table 4), acknowledging the dual character of and the specific nature of these two exits (DeTienne, 2010). Hypothesis 2 regarding normative pressure remains stable in terms of direction and significance in both the management exit and the ownership exit model (management exit model, β = 1.735; p = 0.001; ownership exit model, β = 1.590; p = 0.000). Labor market development (H1) affects the logarithmic odds of family succession intentions in a negative and significant way only in ownership exit (ownership, β = − 3.596; p = 0.046; management, p = 0.119), indicating that founders in underdeveloped labor markets would intentionally plan to hand over their ownership to their children, securing their stream of income from the firm’s revenues and dividends paid. The benevolent paternalistic leadership style (H3) was insignificant regarding ownership exit intentions (β = 0.419; p = 0.148) and a marginally significant predictor of management exit intentions (β = − 0.937; p = 0.051). While benevolent paternalism discourages founders from handing over the management of the firm to their offspring, it does not have any influence on ownership transfer, indicating that future family ownership is not perceived as a threat to the continuation of paternalistic leadership.

6 Discussion

The results of this study show that in emerging economies, institutions matter for the development of specific exit intentions. We demonstrate that the underdeveloped labor market decreases and the normative pressure of reference groups increases family succession intentions, while a benevolent paternalistic leadership style somewhat decreases family succession intentions. Also, the analysis shows that the feasibility of succession increases family succession intentions, confirming that financial reasons may permit (or prevent) family succession (De Massis et al., 2008). The marginal, positive effect of the number of family employees supported that involvement of a family member in the firm may lead to family succession intentions (Chua et al., 2004; Hoy & Verser, 1994). Finally, education level somewhat decreased family succession intentions, agreeing with the extant family firm literature (Richards et al., 2019).

6.1 Contributions to entrepreneurship, family business, and neoinstitutional theory literature

Addressing the gap in knowledge about the contextual factors that affect entrepreneurial exit (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Nordqvist et al., 2013) and the social context of a succession (Dehlen et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2003), this study shows that while exit is an intentional and deliberate process (Wennberg et al., 2010), institutional embeddedness affects whether firm founders develop family-external exit intentions or family succession intentions. This phenomenon is important because exit intentions turn into exit events, which impact individual founders (Wennberg et al., 2011), their financial returns (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; DeTienne & Chirico, 2013), the survivability of the firm (Wennberg et al., 2011), the industry, and even the region in which the firm operates (DeTienne, 2010). This study extends the extant literature, which focuses predominantly on individual- and firm-level antecedents of entrepreneurial exit (e.g.Dehlen, et al., 2014; DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; Dyer, 1988; Scholes, et al., 2008; Ward, 2016; Wennberg et al., 2010), and goes beyond the few articles that set their analysis in a particular macroeconomic period (Cefis, et al., 2021), such as during a severe recession (Carreira & Teixeira, 2016) or economic distress (Balcaen et al., 2012), and macrofactors, such as socioeconomic jolts or environmental regulations (Cefis, et al., 2021). Setting the analysis in the frame of neoinstitutional theory allowed us to holistically analyze entrepreneurial exit at the macro- (underdeveloped labor market), meso- (normative pressure), and microlevels (benevolent paternalistic leadership style) and therefore address the often observed lack of multilevel design in studies of entrepreneurial processes (Nordqvist et al., 2013).

This study extends the limited understanding of entrepreneurship in emerging economies (Bruton et al., 2008), which has thus far touched only upon the impact of formal institutions (Hoskisson et al., 2000; Mair & Marti, 2009; Puffer et al., 2010; Smallbone & Welter, 2006; Tonoyan et al., 2010) and their quality (Iwasaki et al., 2021), and often reported conflicting results (Gedajlovic et al., 2012). We position this study in the context of a special case of emerging economies—transition economies, i.e., ex centrally planned, “tabula rasa” economies—in which there were no routines or path dependence (Sydow, et al., 2009) related to an entrepreneurial exit and in which the economy saw an “explosion of entrepreneurship” (Smallbone & Welter, 2006, p. 200) within a short period in time. Thus, we intended to highlight the particular role of national culture (Chakrabarty, 2009) in entrepreneurial processes, which fills in institutional voids (Bruton et al., 2010; Mair & Marti, 2009; Thornton et al., 2012), such as an underdeveloped labor market. We specifically looked at the notion of family as a value in the national culture and studied the effect of benevolent paternalistic leadership, which is congruent with family values, high-power distance, and collectivism, as well as the normative pressure of reference groups towards family business succession on founders’ cognition. Robustness tests showed that the normative pressures of all reference groups—family, friends, employees, customers, and other family firms in the network—are drivers of family succession intentions, extending the current literature, which merely proposes that the loss of key customers or suppliers (DeMassis et al., 2008), and the satisfaction of different family stakeholders (Sharma, et al., 2001) may impact succession process outcomes (Sharma, et al., 2003).

Applying the notion of an entrepreneurial exit to the first family business succession, this study integrates two distinctive but overlapping literature streams: entrepreneurial exit—specifically exit strategies (DeTienne et al., 2015; Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014)—and family business succession (De Massis et al., 2016; Dyer, 1988; Lansberg & Astrachan, 1994; Sharma et al., 2001; Ward, 2016). We put firm founders’ intentions at the center of the analysis and conceptualize family succession as a synchronized exit and entry process (Nordqvist et al., 2013). In our analysis of the exit, we reach out to the understanding of succession as a long-term, dynamic (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004), multistaged process (Daspit et al., 2016; Handler, 1994; Michel, & Kammerlander, 2015), which contradicts the current notion of exit intent development as a temporary issue related to upcoming events such as retirement (Soleimanof et al., 2015). We also show that family as a reference group (Leaptrott, 2005) exerts normative pressure on the formation of family succession intentions. We thus extend the family business literature, which has rarely investigated the institution of the family to date (Amore et al., 2017; Bertrand & Schoar, 2006; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2017), and the entrepreneurial exit literature, which lacks the family embeddedness perspective (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003) and omits the impact of business-family interface on exit intentions (Hsu et al., 2016).

6.2 Practical implications

This research brings interesting practical implications. In the first place, our study may be an “eye opener” the firm founders—who, as in our sample, often develop family succession intentions—to understand that their cognition and their exit preferences are shaped by neoinstitutions. This may widen their perspective so that in the future they may consider a broader scope of possible paths for entrepreneurial exits and include options other than the classic “father-to-son succession,” for example, management buy-in. Second, our study provides evidence that the policy-makers shall take the cultural aspects into account when designing their countries’ entrepreneurial and family business ecosystems. For example, they may promote various types of succession and exit to alleviate the culturally prescribed exit route. Additionally, policy-makers may influence the exit paths with an improved access to and development of additional financial instruments to overcome the burden of financing the succession, as well as improved access to higher education (education level of firm founders exerts the counteracting effect on the culturally prescribed exit route).

6.3 Limitations

Despite several contributions, this study is subject to some limitations, which represent interesting avenues for future research. First, we measure intentions, which may not always result in real behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2001). Despite the fact that prior studies showed that 70 percent of exit intentions resulted in real exit behaviors (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012), we recommend future research to employ longitudinal studies. Second, even though the proposed cross-sectional study design allowed us to estimate the odds ratios to study the relationship between institutions and exit intentions, this method also limits the ability to derive causal relationships from the cross-sectional analysis. Third, we encourage scholars to perform cross-country comparisons as generalizations of the results of this study due to a single-country and single-institutional setup focus. We expect, however, similar effects in other transition economies with traditional family values and deference to authority, including Ukraine, Russia, Armenia, Croatia, or Hungary (World Values Survey 7, 2020).

Notes

In this study, we theorize about exit generally but empirically we also account for ownership exit and management exit separately.

While the European Union defines SMEs as firms with less than 250 employees, we followed the definition of IfM Bonn, which includes firms up to 500 employees in their SME definition (Welter et al., 2016). In our sample 140 firms (63.1%) are micro-enterprises, with up to 10 employees; 54 firms (24.3%) are small enterprises, with 11 to 50 employees; and 28 firms (12.6%) are medium-enterprises, with 51 to 370 employees.

Respondents were asked to indicate if being self-employed compared to an employee gives them more advantages or more disadvantages.

References

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. B. (2010). Rapid institutional shifts and the co–evolution of entrepreneurial firms in transition economies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00373.x

Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G., & Lui, S. Y. (2000). Navigating China’s changing economy: Strategies for private firms. Business Horizons, 43, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-6813(00)87382-6

Aldrich, H. E. (2015). Perpetually on the eve of destruction? Understanding exits in capitalist societies at multiple levels of analysis. In D. R. DeTienne, & K. Wennberg (Eds.), Research Handbook of Entrepreneurial Exit. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioural control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

Amaral, A. M., Baptista, R., & Lima, F. (2007). Entrepreneurial exit and firm performance. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 27(5), 1. Retrieved from: http://digitalknowledge.babson.edu/fer/vol27/iss5/1

Amore, M. D., Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Corbetta, G. (2017). For love and money: Marital leadership in family firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 46, 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.09.004

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

Arregle, J. L., Hitt, M. A., Sirmon, D. G., & Very, P. (2007). The development of organizational social capital: Attributes of family firms. Journal of Management Studies, 44(1), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00665.x

Autio, E., Pathak, S., & Wennberg, K. (2013). Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviors. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 334–362. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.15

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., Stahl, G., & Kurshid, A. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology, 49(1), 192–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00010

Backman, M., & Palmberg, J. (2015). Contextualizing small family firms: How does the urban–rural context affect firm employment growth? Journal of Family Business Strategy, 6(4), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2015.10.003

Balcaen, S., Manigart, S., Buyze, J., & Ooghe, H. (2012). Firm exit after distress: Differentiating between bankruptcy, voluntary liquidation and M&A. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 949–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9342-7

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1986.4306261

Bełdowski, J., Ciżkowicz, M., & Sześciło, D. (2010). Efektywność polskiego sądownictwa w świetle badań międzynarodowych i krajowach [The effectiveness of Polish judiciary in the light of international and domestic studies]. Retrieved from Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju [Civic Development Forum]: https://www.for.org.pl/pl/a/1131

Bennedsen, M., Nielsen, K. M., Perez-Gonzalez, F., & Wolfenzon, D. (2007). Inside the family firm: The role of families in succession decisions and performance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 647–691. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.2.647

Bennett, D. L. (2020). Local institutional heterogeneity & firm dynamism: Decomposing the metropolitan economic freedom index. Small Business Economics, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00322-2

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511435355

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82–113. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82

Berrone, P., Duran, P., Gómez-Mejía, L., Heugens, P. P., Kostova, T., & van Essen, M. (2020). Impact of informal institutions on the prevalence, strategy, and performance of family firms: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00362-6

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2006). The role of family in family firms. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.20.2.73

Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205

Bird, M., & Wennberg, K. (2014). Regional influences on the prevalence of family versus non-family start-ups. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(3), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.06.004

Birley, S. (2001). Owner-manager attitudes to family and business issues: A 16 country study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(2), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870102600204

Block, J., Thurik, R., van der Zwan, P., & Walter, S. (2013). Business takeover or new venture? Individual and environmental determinants from a cross-country study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(5), 1099–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00521.x

Bluhm, K., & Martens, B. (2011). The restoration of a family capitalism in East Germany and some possible consequences. In I. Stamm, P. Breitschmid, & M. Kohli (Eds.), Doing succession in Europe. Generational transfers in family businesses in comparative perspective (pp. 129–152). Zurich, Berlin, Geneva: Schulthess Juristische Medien.

Bonaccorsi, A., Giannangeli, S., & Rossi, C. (2006). Entry strategies under competing standards: Hybrid business models in the open source software industry. Management Science, 52(7), 1085–1098. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0547

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H.-L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

Bruton, G., Ahlstrom, D., & Obłój, K. (2008). Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00213.x

Calabro, A., & Mussolino, D. (2012). Paternalistic relationships between senior and junior generation: Effect on family firms’ entrepreneurial activities. In G. Dossena, & C. Bettinelli (Eds.), Entrepreneurship Issues: An International Perspective. Bergamo: Bergamo University Press.

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00081.x

Carreira, C., Teixeira, P. (2016). Entry and exit in severe recessions: Lessons from the 2008–2013 Portuguese economic crisis. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 591–617: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9703-3

Cefis, E., Bettinelli, C., Coad, A., & Marsili, O. (2021). Understanding firm exit: A systematic literature review. Small Business Economics, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00480-x

Central Statistical Office of Poland. (2014,). Employment, wages and salaries in national economy in 2014. Retrieved 01 30, 2016, from http://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/labour-salaries/working-employed-wages-and-salaries-cost-of-labour/employment-wages-and-salaries-in-national-economy-in-2014,1,24.html

Central Statistical Office of Poland (2019). Atlas of enterprises. Retrieved 08 29, 2019, from Central Statistical Office of Poland: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/podmioty-gospodarcze-wyniki-finansowe/przedsiebiorstwa-niefinansowe/atlas-przedsiebiorstw,30,1.html

Chakrabarty, S. (2009). The influence of national culture and institutional voids on family ownership of large firms: A country level empirical study. Journal of International Management, 15(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2008.06.002

Chang, E. P., Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Kellermanns, F. (2008). Regional economy as a determinant of the prevalence of family firms in the United States: A preliminary report. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00241.x

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., & Farh, J. L. (2000). A triad model of paternalistic leadership: The constructs and measurement. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 14(1), 3–64.

Chirico, F., Gómez-Mejia, L. R., Hellerstedt, K., Withers, M., & Nordqvist, M. (2020). To merge, sell, or liquidate? Socioemotional wealth, family control, and the choice of business exit. Journal of Management, 46(8), 1342–1379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318818723

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., De Massis, A., Frattini, F., & Wright, M. (2015). The ability and willingness paradox in family firm innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12207

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family–centered non–economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.x

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Chang, E. P. (2004). Are family firms born or made? An Exploratory Investigation. Family Business Review, 17(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00002.x

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402

Daspit, J. J., Holt, D. T., Chrisman, J. J., & Long, R. G. (2016). Examining family firm succession from a social exchange perspective: A multiphase, multistakeholder review. Family Business Review, 29(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515599688

De Massis, A., Chua, J. H., & Chrisman, J. J. (2008). Factors preventing intra-family succession. Family Business Review, 21(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00118.x

De Massis, A., Sieger, P., Chua, J. H., & Vismara, S. (2016). Incumbents’ attitude toward intrafamily succession: An investigation of its antecedents. Family Business Review, 29(3), 278–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486516656276

Deephouse, D. L. (1999). To be different, or to be the same? It’s a question (and theory) of strategic balance. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2%3c147::AID-SMJ11%3e3.0.CO;2-Q

Dehlen, T., Zellweger, T., Kammerlander, N., & Halter, F. (2014). The role of information asymmetry for the choice of entrepreneurial exit routes. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.001

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004

DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9284-5

DeTienne, D. R., & Chandler, G. N. (2010). The impact of motivation and causation and effectuation approaches on exit strategies. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 30(1), 1–13. Retrieved from: http://digitalknowledge.babson.edu/fer/vol30/iss1/1.

DeTienne, D. R., & Chirico, F. (2013). Exit strategies in family firms: How socioemotional wealth drives the threshold of performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1297–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12067

DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Chandler, G. N. (2015). Making sense of entrepreneurial exit strategies: A typology and test. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.007

DeTienne, D. R., & Wennberg, K. (2015). Research Handbook of Entrepreneurial Exit. Edward Elgar Publishing.

DeTienne, D. R., & Wennberg, K. (2016). Studying exit from entrepreneurship: New directions and insights. International Small Business Journal, 34(2), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615601202

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Duran, P. (2015). Strategy and performance of family firms: An institutional embeddedness perspective [Doctoral dissertation]. University of South Carolina. (UMI No. 3704317)

Dyer, G. W. (1988). Culture and continuity in family firms. Family Business Review, 1(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1988.00037.x

Fang He, V., Sirén, C., Singh, S., Solomon, G., & von Krogh, G. (2018). Keep calm and carry on: Emotion regulation in entrepreneurs’ learning from failure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(4), 605–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718783428

Faugier, J., & Sargeant, M. (1997). Sampling hard to reach populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(4), 790–797. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00371.x

Fisman, R., & Khanna, T. (2004). Facilitating development: The role of business groups. World Development, 32(4), 609–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.08.012

Fries, A., Kammerlander, N., & Leitterstorf, M. (2020). Leadership styles and leadership behaviors in family firms: A systematic literature review. Journal of Family Business Strategy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2020.100374

Fuentelsaz, L., González, C., & Maícas, J. P. (2020). High-growth aspiration entrepreneurship and exit: The contingent role of market-supporting institutions. Small Business Economics, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00320-4

Ganter, M. M., Kammerlander, N., & Zellweger, T. M. (2014). The incumbent’s dilemma when exiting the firm: Torn between the family and the corporate logic. Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2014, No. 1, p. 13896). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of management. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2014.227

Gedajlovic, E., Carney, M., Chrisman, J. J., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2012). The adolescence of family firm research: Taking stock and planning for the future. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1010–1037. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311429990

Gentile-Lüdecke, S., de Oliveira, R. T., & Paul, J. (2020). Does organizational structure facilitate inbound and outbound open innovation in SMEs? Small Business Economics, 55(4), 1091–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00175-4

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653–707. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.593320

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Nunez-Nickel, M., & Gutierrez, I. (2001). The role of family ties in agency contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069338

Greenwood, R., Díaz, A. M., Li, S. X., & Lorente, J. C. (2010). The multiplicity of institutional logics and the heterogeneity of organizational responses. Organization Science, 21(2), 521–539. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0453

Gupta, V., Levenburg, N., Moore, L. L., Motwani, J., & Schwarz, T. V. (2008). Exploring the construct of family business in the emerging markets. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 1(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEM.2008.020869

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Halter, F., & Schroeder, R. (2011). Unternehmensnachfolge in der Theorie und Praxis: das St.Galler Nachfolge Modell [Business succession in the theory and practice: The St.Gallen succession model]. Bern: Haupt.

Handler, W. C. (1994). Succession in family business: A review of the research. Family Business Review, 7(2), 133–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1994.00133.x

Heugens, P. P., & Lander, M. W. (2009). Structure! Agency! (and other quarrels): A meta-analysis of institutional theories of organization. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 61–85. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.36461835

Hofstede Insights. (n.d.). Country comparison: Poland. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/poland/

Hofstede, G. (1985). The interaction between national and organizational value systems [1]. Journal of Management Studies, 22(4), 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1985.tb00001.x

Hofstede, G., & Minkov, M. (2010). Long-versus short-term orientation: New perspectives. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16(4), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381003637609

Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., & Schmitt, J. (2010). Brand awareness in business markets: When is it related to firm performance? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27(3), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.03.004

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556394

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications.

Hoy, F., & Verser, T. G. (1994). Emerging business, emerging field: Entrepreneurship and the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879401900101

Hsu, D. K., Wiklund, J., Anderson, S. E., & Coffey, B. S. (2016). Entrepreneurial exit intentions and the business-family interface. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.08.001

International Monetary Fund. (2000). World economic outlook: Focus on transition economies. Washington, DC. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2016/12/31/Focus-on-Transition-Economies

International Monetary Fund. (2021). World economic outlook: Managing divergent recoveries. Washington, DC. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/03/23/world-economic-outlook-april-2021

Iwasaki, I., Kočenda, E., & Shida, Y. (2021). Institutions, financial development, and small business survival: Evidence from European emerging markets. Small Business Economics, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00470-z

Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(1), 71–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00133

Jenkins, A., & McKelvie, A. (2016). What is entrepreneurial failure? Implications for future research. International Small Business Journal, 34(2), 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615574011

Jennings, D. P., Greenwood, R., Lounsbury, M. D., & Suddaby, R. (2013). Institutions, entrepreneurs, and communities: A special issue on entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.07.001

Kammerlander, N. (2016). “I want this firm to be in good hands”: Emotional pricing of resigning entrepreneurs. International Small Business Journal, 34(2), 189–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614541287